Forced labor in the Soviet Union: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

The [[Gulag]] which is an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Ispravitel-no-trudovykh Lagerei or Chief Directorate of prison camps in former Soviet Union.<ref name = Anne>{{cite book |first=Anne|last=Applebaum |authorlink=Anne Applebaum|title=[[Gulag: A History]]|year=2004|publisher=New York: Anchor Books}}</ref> The Gulag was the main agency that implemented the policy of forced labour during the Stalin Era. It was created after the 1917 revolution and greatly grew throughout the thirties during [[Joseph Stalin]]’s reign in order to turn the Soviet Union to an industrialized nation.<ref name = Gulag>{{Cite web|publisher=[[Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media|Center for History and New Media]]|title=Gulag:Soviet Forced Labor Camps and the Struggle for Freedom|url=http://gulaghistory.org/nps/onlineexhibit/stalin/work.php|format=PDF|accessdate=November 15, 2012}}</ref> Many historians believe that the camps were a way of handling any enemies of the regime and used as a threat to millions, others believe that it was created by the means of rapid industrialization and economic growth.<ref name="Harris"/> |

The [[Gulag]] which is an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Ispravitel-no-trudovykh Lagerei or Chief Directorate of prison camps in former Soviet Union.<ref name = Anne>{{cite book |first=Anne|last=Applebaum |authorlink=Anne Applebaum|title=[[Gulag: A History]]|year=2004|publisher=New York: Anchor Books}}</ref> The Gulag was the main agency that implemented the policy of forced labour during the Stalin Era. It was created after the 1917 revolution and greatly grew throughout the thirties during [[Joseph Stalin]]’s reign in order to turn the Soviet Union to an industrialized nation.<ref name = Gulag>{{Cite web|publisher=[[Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media|Center for History and New Media]]|title=Gulag:Soviet Forced Labor Camps and the Struggle for Freedom|url=http://gulaghistory.org/nps/onlineexhibit/stalin/work.php|format=PDF|accessdate=November 15, 2012}}</ref> Many historians believe that the camps were a way of handling any enemies of the regime and used as a threat to millions, others believe that it was created by the means of rapid industrialization and economic growth.<ref name="Harris"/> |

||

Prisoners had to work in intense climates, unsanitary conditions and work extremely hard for long periods of time. Also the prisoners were fed meager food rations and were punished excessively by the [[NKVD]] causing high death rates among the camps.<ref name = Gulag/><ref name="age of war">{{cite journal|last= Merriman |first= John |authorlink= John M. Merriman |last2=Winter |first2=Jay |authorlink2=Jay Winter |title= Europe Since 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction |publisher= [[Charles Scribner's Sons]] |volume= 3|pages=1285–1291 |year=2006}}</ref> Though the prisoners were unskilled and thereby inefficient they were put to work for economic purposes<ref name = Gulag/><ref>{{cite journal |last=Davies |first=R.W. |authorlink=Robert William Davies |title=The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag |journal=[[Journal of Cold War Studies]] |volume=9 |issue=1 |year=2007 |pages=165–167}}</ref> The camps were home to many different kinds of people, some were murderers, thieves and rapists but the majority were innocent individuals who were sent to the Gulag without trial due to speculations that they were traitors or capitalists. Millions of people were sent to the Gulag or work camps for reasons including being late for work, saying anything against the government |

Prisoners had to work in intense climates, unsanitary conditions and work extremely hard for long periods of time. Also the prisoners were fed meager food rations and were punished excessively by the [[NKVD]] causing high death rates among the camps.<ref name = Gulag/><ref name="age of war">{{cite journal|last= Merriman |first= John |authorlink= John M. Merriman |last2=Winter |first2=Jay |authorlink2=Jay Winter |title= Europe Since 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction |publisher= [[Charles Scribner's Sons]] |volume= 3|pages=1285–1291 |year=2006}}</ref> Though the prisoners were unskilled and thereby inefficient they were put to work for economic purposes<ref name = Gulag/><ref>{{cite journal |last=Davies |first=R.W. |authorlink=Robert William Davies |title=The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag |journal=[[Journal of Cold War Studies]] |volume=9 |issue=1 |year=2007 |pages=165–167}}</ref> The camps were home to many different kinds of people, some were murderers, thieves and rapists but the majority were innocent individuals who were sent to the Gulag without trial due to speculations that they were traitors or capitalists. Millions of people were sent to the Gulag or work camps for reasons including being late for work, saying anything against the government or even taking a few potatoes from a field to eat.<ref name = Anne/><ref name = Gulag/> |

||

==Daily Life as a Soviet Slave== |

==Daily Life as a Soviet Slave== |

||

Prisoners |

Prisoners were forced to work extremely strenuous labour for up to 14 hours in a single day. Prisoners did jobs like forestry work with saws and axes,they mined ore by hand where often they suffered painful and fatal diseases from inhalation of ore dust. They also had to dig at frozen ground with primitive pickaxes for construction, construction of defensive lines, creating railroads, and creating large canals like the workers in [[Belbaltlag]], which is a Gulag camp where the prisoners would work on building the [[White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal]].<ref name = Gulag/><ref name="age of war"/><ref name="bacon">{{cite journal|author=Edwin Bacon |title= Glasnost and the Gulag: New information on Soviet forced labor around World War II |journal=Soviet Studies |volume= 6|pages=1069 |year=1992}}</ref> Prisoners were meagrely fed and could barely sustain these hard working conditions and freezing cold climate. Typically about thirty percent of the labour force was too sick or weak to work but were punished if they did not show up to perform the labour, thus it was not uncommon for prisoners to drop dead on the job.<ref name="Harris"/> |

||

The chart below is based on the typical daily schedule at Gulag camp Perm-36.<ref name = Gulag/> |

The chart below is based on the typical daily schedule at Gulag camp Perm-36.<ref name = Gulag/> |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

===Women life in the Gulag=== |

===Women life in the Gulag=== |

||

Women were housed in separate barracks from the men but often were in the same work camps as the men. |

Women were housed in separate barracks from the men but often were in the same work camps as the men. Women completed the same labor and in many situations worked side by side with the men. There were some seperate camps for children, for mothers with babies, and other special cases.<ref name="colony"/> Women in the Gulag were preyed upon from men and they were often raped and abused by the other men in the camps. Upon arrival at the camp, prisoners would be stripped naked where their things would be searched and the guards would pick individual women, promising easier work in exchange for sexual favors.<ref name = Gulag/><ref name="colony">{{cite journal|first=Daniel W. |last=Michael |title= The Gulag: Communism's Penal Colonies Revisited |journal= [[Journal of Historical Review]] |volume= 21|pages=39 |year=2002 }}</ref> |

||

==Types of Labor== |

==Types of Labor== |

||

===Corrective labour without deprivation of freedom=== |

===Corrective labour without deprivation of freedom=== |

||

This |

This was a form of penalty imposed by the court for a term of one month to one year. With this form of slave labour a certain amount of their earnings was deducted as state income based on gross amount earned before taxes and benefits for temporary disability, pregnancy and childbirth benefits. This type of labour was imposed by the court in cases in which the person whom committed the crime and the defendant give ground to presume that that the prisoners correction and re-education may be accomplished without isolation from society in collective labour.<ref name="Harris"/><ref name="encyclopedia">{{cite book | title= The Great Soviet Encyclopedia| year =1979| editor = A.M Prokhorov| publisher = New York: Macmillan, London: Collier Macmillan}}</ref> |

||

===Deprivation of freedom=== |

===Deprivation of freedom=== |

||

This type of penalty |

This type of penalty consisted of enforced isolation of the criminal from society. It was served in special places of confinement designated by the state for this purpose, for example, the Gulag. This was only assigned by a court for a person who was sentenced to a term of three months to ten years.<ref name="Harris"/><ref name="encyclopedia"/> |

||

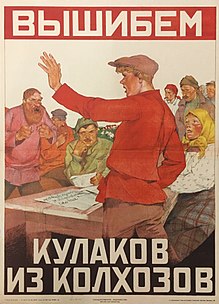

[[File:Вышибем кулаков из колхозов 1930.jpg|Вышибем кулаков из колхозов 1930||left|thumb|Soviet propaganda: We will keep out Kulaks from the collective farms]] |

[[File:Вышибем кулаков из колхозов 1930.jpg|Вышибем кулаков из колхозов 1930||left|thumb|Soviet propaganda: We will keep out Kulaks from the collective farms]] |

||

===Exile combined with corrective labor=== |

===Exile combined with corrective labor=== |

||

This type of punishment |

This type of punishment was served after part of their sentence. By decision of a court, prisoners from correctional camps with whom have made a solid start on the path of rehabilitation were sent to exile colonies. In the exile colonies the prisoners had more freedoms with permission of the administration. The colonies were designed to reinforce the results of the re education of convicts and to create the necessary conditions to assimilate the prisoners back to normal living conditions.<ref name="Harris"/><ref name="encyclopedia">{{cite book | author = title= The Great Soviet Encyclopedia| year =1979| editor = A.M Prokhorov| pages = publisher = New York: Macmillan, London: Collier Macmillan}}</ref> |

||

==Kulak== |

==Kulak== |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

[[Kolyma]] was the most notorious labour camp.<ref name = Gulag/> It was located at the extreme northeast of Siberia and had a reputation to be the coldest inhabited place on the planet. Kolyma was mined for its rich deposits of gold by the laborers in the Gulag camps though millions of prisoners perished in the camps due to the cold Arctic climates. Stalin used this as free labour to obtain essential resources and a way to get rid of the criminals and communist resistance by sending prisoners to Kolyma.<ref name = Kolyma>{{Cite web|author=Stanislaw J. Kowalski |title=Kolyma: The Land of Gold and Death |url=http://www.aerobiologicalengineering.com/wxk116/sjk/kolyma.html |publisher=www.aerobiologicalengineering.com |format=PDF|accessdate=November 15, 2012}}</ref> |

[[Kolyma]] was the most notorious labour camp.<ref name = Gulag/> It was located at the extreme northeast of Siberia and had a reputation to be the coldest inhabited place on the planet. Kolyma was mined for its rich deposits of gold by the laborers in the Gulag camps though millions of prisoners perished in the camps due to the cold Arctic climates. Stalin used this as free labour to obtain essential resources and a way to get rid of the criminals and communist resistance by sending prisoners to Kolyma.<ref name = Kolyma>{{Cite web|author=Stanislaw J. Kowalski |title=Kolyma: The Land of Gold and Death |url=http://www.aerobiologicalengineering.com/wxk116/sjk/kolyma.html |publisher=www.aerobiologicalengineering.com |format=PDF|accessdate=November 15, 2012}}</ref> |

||

==De-Stalinization== |

|||

==Death of Stalin== |

|||

[[File:StalinEnLaConferenciaDeYalta--TR 002828 A.jpg|StalinEnLaConferenciaDeYalta--TR 002828 A|left|thumb| Joseph Stalin at Yalta Conference (1878-1953)]] |

[[File:StalinEnLaConferenciaDeYalta--TR 002828 A.jpg|StalinEnLaConferenciaDeYalta--TR 002828 A|left|thumb| Joseph Stalin at Yalta Conference (1878-1953)]] |

||

[[Joseph Stalin]] died on March 5, 1953. By then the Gulag had reached its maximum amount of prisoners at around 2.7 million.<ref name = Gulag/><ref name="colony">{{cite journal|author=Daniel W. Michael |title= The Gulag: Communism's Penal Colonies Revisited |journal= Journal of Historical Review |volume= 21|pages=39 |year=2002}}</ref> Over the next few years under Stalin’s successors the population of Gulag prisoners decreased substantially because they were convinced that forced labour was wasteful and inefficient. After Stalin’s death the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev moved to relieve Soviet repression and decreased the population to a greater extent. Khrushchev allowed for open discussion of the lifestyles of those living and working in the Gulag, even giving permission for author [[Alexander Solzhenitsyn]] to publish “one day in the life of Ivan Denisovich,” a Soviet novel of life in Stalin’s forced labour camps.<ref name = Gulag/> This period of time was only temporary for Khrushchev was removed from power in 1964 and the subject of the Gulag became forbidden once again until 1985. In 1985 [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] came to power and initiated a period of openness called [[Glasnost]]. He believed in making a socialist society without repression or violence. The period of openness he titled glasnost allowed for a era of discussing the on goings of the Gulag.<ref name = Gulag/> |

[[Joseph Stalin]] died on March 5, 1953. By then the Gulag had reached its maximum amount of prisoners at around 2.7 million.<ref name = Gulag/><ref name="colony">{{cite journal|author=Daniel W. Michael |title= The Gulag: Communism's Penal Colonies Revisited |journal= Journal of Historical Review |volume= 21|pages=39 |year=2002}}</ref> Over the next few years under Stalin’s successors the population of Gulag prisoners decreased substantially because they were convinced that forced labour was wasteful and inefficient. After Stalin’s death the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev moved to relieve Soviet repression and decreased the population to a greater extent. Khrushchev allowed for open discussion of the lifestyles of those living and working in the Gulag, even giving permission for author [[Alexander Solzhenitsyn]] to publish “one day in the life of Ivan Denisovich,” a Soviet novel of life in Stalin’s forced labour camps.<ref name = Gulag/> This period of time was only temporary for Khrushchev was removed from power in 1964 and the subject of the Gulag became forbidden once again until 1985. In 1985 [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] came to power and initiated a period of openness called [[Glasnost]]. He believed in making a socialist society without repression or violence. The period of openness he titled glasnost allowed for a era of discussing the on goings of the Gulag.<ref name = Gulag/> |

||

Revision as of 20:19, 3 December 2012

Under the reign of Joseph Stalin, forced labour in the Soviet Union was used in order to achieve the economic goals of the Five-Year Plan.[1] Forced labour was a vital part of the rapid industrialization and economic growth of the Soviet Union. Between 1932-1946 the Soviet secret police detained approximately 18,207,150 prisoners. The Gulag prison system had put into practice the use of forced labour by imprisoning not only dangerous criminals but also people convicted of political crimes against the communistic government.[2]

Labourers had to work in freezing climates, unhygienic conditions, dangerous circumstances and worked for extensive time periods without rest. Many prisoners were able to perform the forced labour necessary but a large number of prisoners were too hungry, sick, or injured from the intense working conditions to complete the labour. Often prisoners were punished for not reaching targets by getting fewer rations of food than those who did reach production targets; thereby it was not unlikely for prisoners to die of starvation.[3][4]

Gulag: Soviet Penal System

The Gulag which is an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Ispravitel-no-trudovykh Lagerei or Chief Directorate of prison camps in former Soviet Union.[2] The Gulag was the main agency that implemented the policy of forced labour during the Stalin Era. It was created after the 1917 revolution and greatly grew throughout the thirties during Joseph Stalin’s reign in order to turn the Soviet Union to an industrialized nation.[3] Many historians believe that the camps were a way of handling any enemies of the regime and used as a threat to millions, others believe that it was created by the means of rapid industrialization and economic growth.[4]

Prisoners had to work in intense climates, unsanitary conditions and work extremely hard for long periods of time. Also the prisoners were fed meager food rations and were punished excessively by the NKVD causing high death rates among the camps.[3][5] Though the prisoners were unskilled and thereby inefficient they were put to work for economic purposes[3][6] The camps were home to many different kinds of people, some were murderers, thieves and rapists but the majority were innocent individuals who were sent to the Gulag without trial due to speculations that they were traitors or capitalists. Millions of people were sent to the Gulag or work camps for reasons including being late for work, saying anything against the government or even taking a few potatoes from a field to eat.[2][3]

Daily Life as a Soviet Slave

Prisoners were forced to work extremely strenuous labour for up to 14 hours in a single day. Prisoners did jobs like forestry work with saws and axes,they mined ore by hand where often they suffered painful and fatal diseases from inhalation of ore dust. They also had to dig at frozen ground with primitive pickaxes for construction, construction of defensive lines, creating railroads, and creating large canals like the workers in Belbaltlag, which is a Gulag camp where the prisoners would work on building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal.[3][5][7] Prisoners were meagrely fed and could barely sustain these hard working conditions and freezing cold climate. Typically about thirty percent of the labour force was too sick or weak to work but were punished if they did not show up to perform the labour, thus it was not uncommon for prisoners to drop dead on the job.[4]

The chart below is based on the typical daily schedule at Gulag camp Perm-36.[3]

| 6:30 AM | Breakfast |

| 7:00 AM | Roll-call |

| 7:30 AM | 1 1/2 hour to march to forests, under guarded escort |

| 6:00 PM | 1 1/2 hour return march to camp |

| 7:30 PM | Dinner |

| 8:00 PM | After-dinner camp work duties (chop firewood, shovel snow, gardening, road repair, etc.) |

| 11:00PM | Lights out |

Women life in the Gulag

Women were housed in separate barracks from the men but often were in the same work camps as the men. Women completed the same labor and in many situations worked side by side with the men. There were some seperate camps for children, for mothers with babies, and other special cases.[8] Women in the Gulag were preyed upon from men and they were often raped and abused by the other men in the camps. Upon arrival at the camp, prisoners would be stripped naked where their things would be searched and the guards would pick individual women, promising easier work in exchange for sexual favors.[3][8]

Types of Labor

Corrective labour without deprivation of freedom

This was a form of penalty imposed by the court for a term of one month to one year. With this form of slave labour a certain amount of their earnings was deducted as state income based on gross amount earned before taxes and benefits for temporary disability, pregnancy and childbirth benefits. This type of labour was imposed by the court in cases in which the person whom committed the crime and the defendant give ground to presume that that the prisoners correction and re-education may be accomplished without isolation from society in collective labour.[4][9]

Deprivation of freedom

This type of penalty consisted of enforced isolation of the criminal from society. It was served in special places of confinement designated by the state for this purpose, for example, the Gulag. This was only assigned by a court for a person who was sentenced to a term of three months to ten years.[4][9]

Exile combined with corrective labor

This type of punishment was served after part of their sentence. By decision of a court, prisoners from correctional camps with whom have made a solid start on the path of rehabilitation were sent to exile colonies. In the exile colonies the prisoners had more freedoms with permission of the administration. The colonies were designed to reinforce the results of the re education of convicts and to create the necessary conditions to assimilate the prisoners back to normal living conditions.[4][9]

Kulak

The kulak were known as the upper class peasantry. They were landowners and they took full advantage of capitalism in pre Soviet-Union Russia but the development of the complete collectivization of agriculture served as the basis for the shift to a policy of liquidating the kulaks as a class.[9] The first major wave to the GULAG was engineered in the early 1930’s to liquidate the Kulak during the great purge.[4][10] Dekulakization had two powerful drives, it was a threat to agricultural regions in order to maintain collectivisation and it gave regions with labor shortages access to a large labor supply.[4] According to data in the Soviet archives, 1,803,392 Kulak were sent to labor colonies and camps from 1930 to 1931.

Productivity

Workday Credit System

The principle of the credit system was that prisoners who met production targets (and conformed to disciplinary rules) were to be rewarded by a reducing the amount of time confined in the Gulag.[11] During the construction of the Baltic White-Sea Canal from 1931 to early 1933, workday credits were often used to motivate forced laborers. After the use of the credit system to successfully do a large scale project in a short period of time the workday credits were established in almost all prison camps. There was a major problem with the workplace credit system though in the fact that they were given to dangerous criminals to make their conviction shorter as well as the productive workers. There was also a problem in the fact that the workplace credit system was only practical in the short run like a period of wartime when much work needed to be done in a short period of time but in the long run the loss of workers due to the early releases caused the workplace credit system to pay for the decreases.[4][11]

Secret Police

The Cheka, GPU, OGPU, NKVD, MVD, and KGB were the political police in the Soviet Union. They stood as a threat to whoever was not being productive enough in a non competitive society. They were the main punishers and supervision held in and out of the GULAG and sped up the process of citizen assimilation to a collective lifestyle. The NKVD sent millions of peasants, intellectuals, religious believers, and dissidents to the GULAG.[10]

Numbers

[7] Amount of people in GULAG corrective camps and labour colonies

| Year | Total |

| 1934 | 510307 |

| 1935 | 965742 |

| 1936 | 1296494 |

| 1937 | 1196369 |

| 1938 | 1881570 |

| 1939 | 1672438 |

| 1940 | 1659992 |

| 1941 | 1929729 |

| 1942 | 1777043 |

| 1943 | 1484182 |

| 1944 | 1179819 |

| 1945 | 1460677 |

| 1946 | 1703095 |

Economic Incentives

The GULAG began as a place to house criminals, traitors and socialists but eventually became an important part in the Soviet Union’s economy and rapid industrialization. The Five Year Plans gave production targets that relied on the expansion of forced laborers to meet the industrial targets. The Gulag system allowed for inexpensive laborers to develop the rapid industrialization to meet the target recommendations thereby an economic motivation was for finding a sufficient number of "enemies of the people" to keep Gulag production in line with targets.[1] The Gulag forced labour industry was intended to be a mobile, cheap workforce that can be easily replenished and is able to advance on inhospitable areas that were plentiful in resources.

The Gulag was very expensive to maintain being as on its own it required an entire infrastructure. The workers were also unmotivated and weakened by poor living conditions. The prisoners, with few rights of their own, led authorities to decide for projects with little economic use. The best known example of this is the White Sea Canal.[1][2] The White Sea Canal was built in-between 1931 and 1933 and it involved over a hundred thousand prisoners that dug a 141 mile canal in 20 months. Though the canal turned out to be to narrow and shallow to support most sea craft.[3]

Kolyma

Kolyma was the most notorious labour camp.[3] It was located at the extreme northeast of Siberia and had a reputation to be the coldest inhabited place on the planet. Kolyma was mined for its rich deposits of gold by the laborers in the Gulag camps though millions of prisoners perished in the camps due to the cold Arctic climates. Stalin used this as free labour to obtain essential resources and a way to get rid of the criminals and communist resistance by sending prisoners to Kolyma.[12]

De-Stalinization

Joseph Stalin died on March 5, 1953. By then the Gulag had reached its maximum amount of prisoners at around 2.7 million.[3][8] Over the next few years under Stalin’s successors the population of Gulag prisoners decreased substantially because they were convinced that forced labour was wasteful and inefficient. After Stalin’s death the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev moved to relieve Soviet repression and decreased the population to a greater extent. Khrushchev allowed for open discussion of the lifestyles of those living and working in the Gulag, even giving permission for author Alexander Solzhenitsyn to publish “one day in the life of Ivan Denisovich,” a Soviet novel of life in Stalin’s forced labour camps.[3] This period of time was only temporary for Khrushchev was removed from power in 1964 and the subject of the Gulag became forbidden once again until 1985. In 1985 Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and initiated a period of openness called Glasnost. He believed in making a socialist society without repression or violence. The period of openness he titled glasnost allowed for a era of discussing the on goings of the Gulag.[3]

References

- ^ a b c Gregory, Paul R. (2003). The Economics of Forced Labour: The Soviet Gulag. HOOVER INST PRESS PUBLICATION.

- ^ a b c d Applebaum, Anne (2004). Gulag: A History. New York: Anchor Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Gulag:Soviet Forced Labor Camps and the Struggle for Freedom" (PDF). Center for History and New Media. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harris, James R. (1997). "The growth of the Gulag: Forced labor in the Urals region". 56 (2). The Russian Review.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Merriman, John; Winter, Jay (2006). "Europe Since 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction". 3. Charles Scribner's Sons: 1285–1291.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Davies, R.W. (2007). "The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag". Journal of Cold War Studies. 9 (1): 165–167.

- ^ a b Edwin Bacon (1992). "Glasnost and the Gulag: New information on Soviet forced labor around World War II". Soviet Studies. 6: 1069. Cite error: The named reference "bacon" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Michael, Daniel W. (2002). "The Gulag: Communism's Penal Colonies Revisited". Journal of Historical Review. 21: 39. Cite error: The named reference "colony" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d A.M Prokhorov, ed. (1979). The Great Soviet Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan, London: Collier Macmillan. Cite error: The named reference "encyclopedia" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Tvardovsky, Alexander (2006). By Right of Memory. Detroit. Cite error: The named reference "Alexander" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Ertz, Simon (2005). "Trading effort for freedom: workday credits in the Stalinist camp system". Comparative Economic Studies. 47 (2): 476+.

- ^ Stanislaw J. Kowalski. "Kolyma: The Land of Gold and Death" (PDF). www.aerobiologicalengineering.com. Retrieved November 15, 2012.