Coolie: Difference between revisions

m Disambiguated: Asian → Asia, Indonesian people → Indonesia |

|||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

* In the 1899 novelette [[Typhoon (novel)|"Typhoon"]] by [[Joseph Conrad]], the captain is transporting a group of coolies in the South China Sea. |

* In the 1899 novelette [[Typhoon (novel)|"Typhoon"]] by [[Joseph Conrad]], the captain is transporting a group of coolies in the South China Sea. |

||

* In the 1957 film ''[[The Bridge on the River Kwai]]'', when his officers are ordered to participate with the construction of the bridge, British officer Col. Nicholson ([[Alec Guinness]]) declares that they will not be used as coolies by their captors. The enlisted men cheer when their social betters are excused the work |

* In the 1957 film ''[[The Bridge on the River Kwai]]'', when his officers are ordered to participate with the construction of the bridge, British officer Col. Nicholson ([[Alec Guinness]]) declares that they will not be used as coolies by their captors. The enlisted men cheer when their social betters are excused the work. |

||

* In [[Indonesian language|Indonesian]], ''kuli'' is now a term for construction workers. In slang languages, the construction workers are frequently termed as "kuproy" (kuli proyek, literally meaning "project coolies") {{Citation needed|date=January 2010}} |

* In [[Indonesian language|Indonesian]], ''kuli'' is now a term for construction workers. In slang languages, the construction workers are frequently termed as "kuproy" (kuli proyek, literally meaning "project coolies") {{Citation needed|date=January 2010}} |

||

Revision as of 14:58, 8 July 2013

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

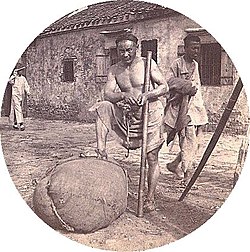

Historically, a coolie (variously spelled cooli, cooly, kuli, quli, koelie etc.) was an Asian slave or unskilled manual labourer, particularly from southern China, the Indian subcontinent, the Philippines and Indonesia during the 19th century and early 20th century. It is also a contemporary racial slur[1] for people of Asian descent, including people from East Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, etc.,[2] particularly in South Africa.[1]

Etymology

Coolie is derived from the Hindi word kuli (क़ुली).[3] The origins of the word are uncertain but it is thought to have been originally used by the Portuguese (cule) as a description of local hired labourers in India. That use may be traced back to a Gujurati tribe (the Kulī, who worked as day labourers) or perhaps to the Tamil word for a payment for work, kuli (கூலி).[3][4] An alternative etymological explanation is that the word came from the Urdu qulī (क़ुली, قلی), which itself could be from the Turkish word for slave, qul.[3] The word was used in this sense for labourers from India, China, and East Asia. In 1727 Dr. Engelbert Kämpfer described "coolies" as dock labourers who would unload Dutch merchant ships at Nagasaki in Japan.[5][6]

The Chinese word 苦 力 (pinyin: kǔlì) literally means "bitterly hard (use of) strength", in the Mandarin pronunciation. In Cantonese, the term is 咕 喱 (Jyutping: Gu lei). The word refers to an Asian slave.

In southern Iran (some cities) this word was used as a low ranking day labour. Coolie especially referred to those labourers who carry things on their back or perform manual labour The word "cool" in that region is slang and among the locals refers to the human back.

The Coolie Trade

The "Coolie Trade", as it eventually became known as, expanded during the 1840s and 1850s and is believed to have began sometime in and around the 16th century.[7][8][9][10] Some of these laborers signed contracts based on misleading promises, some were kidnapped, some were victims of clan violence whose captors sold them to coolie brokers, while others sold themselves to pay off gambling debts. From 1847 to 1862, most Chinese contract laborers ("coolies") bound for Cuba were shipped on American vessels and numbered about 600,000 per year. Conditions on board these and other ships were overcrowded, unsanitary, and brutal. The terms of the contract were often not honored, so many laborers ended up working on Cuban sugar plantations or in Peruvian guano pits. Like slaves, some were sold at auction[9] and most worked in gangs under the command of a strict overseer.

Both contemporary observers and present researchers [who?] have frequently mentioned the similarities between the Coolie trade and the African slave trade.[11] In fact the growth of the Coolie trade was believed to have been spurred due to the worldwide movement to abolish the slave trade and thus the West needed to transition to a substitute labor and or reserve labor to African slaves while the slave trade was gradually fading.[12][13][14] Many coolies were first deceived or kidnapped and then kept in barracoons (detention centres) or loading vessels in the ports of departure, as were African slaves. Their voyages, which are sometimes called the Pacific Passage, were as inhumane and dangerous as the notorious Middle Passage.[15][16] Mortality was very high. For example, it is estimated that from 1847 to 1859, the average mortality for coolies aboard ships to Cuba was 15.2 percent, and losses among those aboard ships to Peru were 40 percent in the 1850s and 30.44 percent from 1860 to 1863.[16] They were sold like animals and were taken to work in plantations or mines under appalling living and working conditions. The duration of a contract was typically five to eight years, but many coolies did not live out their term of service because of the hard labour and mistreatment. Those who did live were often forced to remain in servitude beyond the contracted period. The coolies who worked on the sugar plantations in Cuba and in the guano beds of the Chincha Islands (the islands of Hell) of Peru were treated brutally. Seventy-five percent of the Chinese coolies in Cuba died before fulfilling their contracts. More than two-thirds of the Chinese coolies who arrived in Peru between 1849 and 1874 died within the contract period. Among the four thousand coolies brought to the Chinchas in 1861, not a single one survived. Because of these unbearable conditions, Chinese coolies often revolted against their Chinese and foreign oppressors at ports of departure, on ships, and in foreign lands. The coolies were put in the same neighbourhoods as African Americans and, since most were unable to return to their homeland or have their wives come to the New World, many married African American women. Due to the coolies' especially coolies from East and Southeast Asia (although this was most likely due to the fact that often times they came to their new home countries without Asian women and or their wives) constant interracial relationshps and marriages with Africans, Indigenous peoples, and many other groups of ethnicities this formed some of the modern world's Afro-Asian and Asian Latin American populations.[17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

However, there are significant differences between the Coolie trade and the African slave trade. First, despite the many recorded cases of deceiving and kidnapping coolies, probably not all coolies were forced into bondage, though it is difficult to know what percentage of the total was represented by voluntary coolies. Owing to famines, wars, and shortages of land, many southern Chinese chose to go overseas to seek a better life. Of the voluntary coolies the United States and South Africa were the only recorded countries where the coolie slaves were found by evidence to have been voluntary.[citation needed] Second, not all coolies remained in bondage for life. Some of them became free after serving out their contracts; a few even managed to return to China and other home countries. Coolies received wages, although usually they were paid much less than local workers. Although there are reports of ships for Chinese coolies carrying women and children, the great majority of the Chinese coolies were men. Finally, their home governments (the Chinese government in particular), although were not able to give the coolies as much protection as they needed, showed concern for them. Central and local governments tried continuously to regulate and curb the coolie trade; at one point, the central government even sent inspectors to America to investigate conditions and intervene on the coolies' behalf. The Chinese government also took an active part in the final elimination of the coolie trade in 1874.

History

The term coolie was applied to workers from Asia, especially those who were sent abroad to most of the Americas, to Oceania and the Pacific Islands, and to Africa (especially South Africa and islands like Mauritius, Seychelles, and Réunion). It was also applied in Asian areas under European control such as Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Slavery had been widespread in the British empire, but social and political factors resulted in its being outlawed in 1834; within a few decades other European nations had outlawed slavery.[citation needed] But the intensive colonial labour on sugar cane or cotton plantations, in mines or railways, required cheap manpower.[citation needed]

Experiments were performed with Malagasy, Japanese, Breton, Portuguese, Yemeni and/or Congolese labourers. Ultimately Indians were mainly used, shipped to many Indian Ocean islands, East and South Africa, Fiji, British Guiana, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, Grenada, Suriname, Saint Lucia and Panama and other places.[14][25][26]

Chinese coolies were also another prominently used labour who were mostly sent to the New World only. They worked in guano pits in Peru, in the sugar cane fields in Cuba and helped build railways in the United States and British Columbia (Canada).[27][28][29][30] They along with the Indian coolies also were sent to the Caribbean (although in lesser amounts) the parts of the Caribbean they were sent to were Jamaica, British Guiana (now Guyana), Trinidad and Tobago, British Honduras (now Belize) and Suriname.[31][32][33][34]

In the Americas

Chinese immigration to the United States was almost entirely voluntary, but working and social conditions were still harsh:

In 1868, the Burlingame Treaty repealed the century old prohibition law of the Chinese government and opened a floodgate of Chinese immigration. But a mere decade later, the American economy was in a slump and Chinese labourers were hired as scabs when white workers went on strike. During these years of unemployment and depression, anti-Chinese sentiment built around the country, fuelled by demagogues such as Denis Kearney of San Francisco, who would rail in front of crowds that "To an American, death is preferable to life on a par with the Chinese."

Although Chinese labour contributed to the building of the first Transcontinental Railroad in the United States and of the Canadian Pacific Railway in western Canada, Chinese settlement was discouraged after completion of the construction. California's Anti-Coolie Act of 1862 and the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 contributed to the curtailment of Chinese immigration to the United States.

Notwithstanding such attempts to restrict the influx of cheap labour from China, beginning in the 1870s Chinese workers helped construct a vast network of levees in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. These levees made thousands of acres of fertile marshlands available for agricultural production.

According to the Constitution of the State of California (1879):

The presence of foreigners ineligible to become citizens of the United States is declared to be dangerous to the well-being of the State, and the Legislature shall discourage their immigration by all the means within its power. Asiatic coolieism is a form of human slavery, and is forever prohibited in this State, and all contracts for coolie labour shall be void. All companies or corporations, whether formed in this country or any foreign country, for the importation of such labour, shall be subject to such penalties as the Legislature may prescribe.[36]

Colonos asiáticos is a Spanish term for coolies.[37] The Spanish colony of Cuba feared slavery uprisings such as those that took place in Haiti and used coolies as a transition between slaves and free labor. They were neither free nor slaves. Indentured Chinese servants also labored in the sugarcane fields of Cuba well after the 1884 abolition of slavery in that country. Two scholars of Chinese labor in Cuba, Juan Pastrana and Juan Perez de la Riva, substantiated horrific conditions of Chinese coolies in Cuba[38] and stated that coolies were slaves in all but name.[38] Denise Helly is one researcher who believes despite their slave-like treatment, the free and legal status of the Asian laborers in Cuba separated them from slaves. The coolies could challenge their superiors, run away, petition government officials, and rebel according to Rodriguez Pastor and Trazegnies Granda.[39] Once they had fulfilled their contracts the colonos asiáticos integrated into the countries of Peru, The Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Cuba. They adopted cultural traditions from the natives and also welcomed in non-Chinese to experience and participate into their own traditions.[37] Before the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Havana had Latin America's largest Chinatown.

In South America, Chinese indentured labourers worked in Peru's silver mines and coastal industries (i.e., guano, sugar, and cotton) from the early 1850s to the mid-1870s; about 100,000 people immigrated as indentured workers. They participated with the War of the Pacific, looting and burning down the haciendas where they worked, subsequent to the capture of Lima by the invading Chilean army in January 1880. Some 2000 coolies even joined the Chilean Army in Peru taking care for the wounded and burying the dead. Other were sent by Chileans to work in the newly conquered nitrate fields.[40]

Between 1838 and 1917, at least "238,909 Indians were introduced into British Guiana, 143,939 into Trinidad, 42,326 into Guadeloupe, 37,027 into Jamaica, 34,304 into Suriname, 25,209 into Martinique, 8,472 into French Guiana, 4,354 into Saint Lucia, 3,206 into Grenada, 2,472 into Saint Vincent, 337 into Saint Kitts, 326 into Saint Croix, and 315 into Nevis. British Honduras also received Indians, but they did not come by the indentureship scheme; some were exiled sepoy soldiers and families. Although these were incomplete statistics, Eric Williams (see references) believed they were "sufficient to show a total introduction of nearly half a million Indians into the Caribbean" (Williams 100).[26]

In South Africa

The Chinese Engineering and Mining Corporation, of which later U.S. president Herbert Hoover was a director, was instrumental in supplying Chinese coolie labour to South African mines from c.1902 to c.1910 at the request of mine owners, who considered such labour cheaper than native African and white labour.[41] The horrendous conditions suffered by the coolie labourers led to questions in the British parliament as recorded in Hansard.[42]

Modern use

- In the 1899 novelette "Typhoon" by Joseph Conrad, the captain is transporting a group of coolies in the South China Sea.

- In the 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai, when his officers are ordered to participate with the construction of the bridge, British officer Col. Nicholson (Alec Guinness) declares that they will not be used as coolies by their captors. The enlisted men cheer when their social betters are excused the work.

- In Indonesian, kuli is now a term for construction workers. In slang languages, the construction workers are frequently termed as "kuproy" (kuli proyek, literally meaning "project coolies") [citation needed]

- In Malay, "kuli" is an Asian slave.

- In Thai, kuli (กุลี) still retains its original meaning as manual labourers, but is considered to be offensive.[citation needed]

- In September 2005 the prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra of Thailand used this term when referring to the labourers who built the new international airport. He thanked them for their hard work. Reuters, a news source from Bangkok, reported of Thai labour groups angered by his use of the term.[43]

- In South Africa, Coolie most often referred to Indian people or mixed Black and Indian people, but is no longer an accepted term and is considered extremely derogatory.

- The word qūlī is now commonly used in Hindi to refer to luggage porters at hotel lobbies and railway and bus stations. Nevertheless, the use of such (especially by foreigners) may still be regarded as a slur by some.[44]

- In Ethiopia, Cooli are those who carry heavy loads for someone. The word is not used as a slur however. The term used to refer to Arab day-laborers who migrated to Ethiopia for labour work. [citation needed]

- The Dutch word koelie, refers to a worker who performs very hard, exacting labour. The word generally has no particular ethnic connotations among the Dutch, but it is a racial slur amongst Surinamese of Indian and Indonesian heritage.[45]

- Among overseas Vietnamese, coolie ("cu li" in Vietnamese) means a labourer, but in recent times the word has gained a second meaning a person who works a part-time job.[citation needed]

- In Finland, when freshmen of a technical university take care of student union club tasks (usually arranging a party or such activity), they are referred as "kuli" or performing a "kuli duty".[citation needed]

- In the United States Marine Corps, a Lance Corporal is sometimes referred to jokingly as a "Lance Coolie", due to their often being picked for work details or chosen to perform menial tasks not related to their actual Military Occupational Specialty, especially in units that do not have many Privates or Privates First Class. [citation needed]

- In Guyana, Trinidad & Tobago and Jamaica, coolie is used loosely to refer to anyone of East Indian descent. It is sometimes used in a racially derogatory context and sometimes used in friendly banter.[citation needed]

- In many English-speaking countries, the conical Asian hat worn by many Asians to protect themselves from the sun is called a "coolie hat."

- In the I.T. industry, offshore workers are sometimes referred to as 'coolies' because of their lower cost.

- The term "coolie" appears in the Eddy Howard song, "The Rickety Rickshaw Man". (It was the rickshaw that was rickety.)

- Poet and semiologist Khal Torabully coined the word coolitude to refer to a vision of humanism and diversity born from the indenture or coolie experience. This poetics is studied at university level so as to encompass a new dynamics of migration originating from the encounter of indentured persons and other cultural spheres, namely from postcolonial and postmodern perspectives.

- In Turkish, köle is the term for slave.

In media

Film

In the 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai the term is used numerous times in the film to mean a slave or slaves or being used as slaves.

Throughout the 1982 film Gandhi the term was used as a racial slur.

In Stephen Chow's 2004 action-comedy film Kung Fu Hustle, former Shaolin monk Xing Yu plays a character who works as a Coolie, doing hard labour in a multi-floored apartment-block village called "Pig Sty Alley". However, when a petty thief (Stephen Chow) and his sidekick pose as members of the infamous "Axe Gang" and accidentally bring upon the wrath of actual members, Coolie is the first of three retired martial artists who come to the village's aid. He is a master of the 12 Kicks of the Tam School (十二路潭腿), a leg-oriented boxing style. He is later beheaded by assassins hired by the Axe Gang to kill the village's landlords.

Coolie is an 1983 Indian film about a coolie, Amitabh Bachchan, who works at a railway station and has a lover. His lover's father once murdered a girl's father in an attempt to force her to marry him, but she did not give in. After 10 years of imprisonment, he flooded her village (injuring her new husband) and causing her to awaken with amnesia. It starred Amitabh Bachchan and Waheeda Rehman.

Guiana 1838 is a 2004 docu-drama that explores the unknown world of indentureship and slavery in the British Colonies of the West Indies. It reveals the trials and tribulation of both the African slaves and the unsuspecting Indians from Calcutta who expected "El Dorado" only to find themselves on a ship to hard labour. [3]

The film Romper Stomper shows a white power skinhead named Hando (played by Russell Crowe) expressing distress about the idea of being a coolie in his own country. Also, the gang he directs makes frequent attacks at gangs of working class Vietnamese Australians.

2010's Merry-Go-Round (HK) Dong fung po (original title) the backdrop of this drama is based on the events of the "coolie trade" to the U.S., where Chinese who died abroad had their bodies shipped back to China via Hong Kong. Those whose bodies were not found or unrecoverable, i.e. mining accidents, lost at sea, etc., had empty coffins sent back. The empty coffins symbolised the return of the souls back to their homelands.[46]

The documentary film directed by Yung Chang called Up the Yangtze follows the life of a family in China that are relocated due to the flooding of the Yangtze. The daughter is sent directly from finishing middle school to work on a cruise ship for western tourists, to earn money for her family. Her father referred to himself as a 'coolie' who used to carry bags on and off of boats.[47]

Television

The phrase was used repeatedly in the 1993–1994 Fox weird west series The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr.–set in the 1890s–in reference to Chinese workers.

In the 1983 miniseries, "The Thorn Birds," based on the novel by Colleen McCullough, the main character, Meggie, tells her new husband, Luke, that sugar cane cutting is "coolie" labor.

See also

- Slavery

- Indentured servant

- Aapravasi Ghat

- Blackbirding

- Navvy

- Overseas Indian

- Overseas Chinese

- Chinese Peruvian

- Chinese Cuban

- Indo-Caribbean

- Marabou

- Dougla

- History of Chinese immigration to Canada

- Taiping reform movement

- Immigration to the United States

- Chinese Migration

- List of ethnic slurs

- The Man from Beijing (novel)

References

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (May 2010) |

- ^ a b Location Settings (20 October 2011). "Malema under fire over slur on Indians". News24. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Most current dictionaries do not record any offensive meaning ("an unskilled laborer or porter usually in or from the Far East hired for low or subsistence wages" Merriam-Webster) or make a distinction between an offensive meaning in referring to "a person from the Indian subcontinent or of Indian descent" and an at least originally inoffensive, old-fashioned meaning, for example "dated an unskilled native labourer in India, China, and some other Asian countries" (Compact Oxford English Dictionary). However, some dictionaries indicate that the word may be considered offensive in all contexts today. For example, Longman's 1995 edition had "old-fashioned an unskilled worker who is paid very low wages, especially in parts of Asia", but the current version adds "taboo old-fashioned a very offensive word ... Do not use this word".

- ^ a b c Oxford English Dictionary, retrieved 19 April 2012

- ^ Britannica Academic Edition, retrieved 19 April 2012

- ^ Kämpfer, Engelbert (1727). The History ofk,o Japan. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:Preferences.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Dictionary, Arts, Sciences, and General Literature (9th, American Reprint ed.). Maxwell Sommerville (Philadelphia). 1891. p. 296. Volume VI.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); no-break space character in|id=at position 7 (help) - ^ Coolie (Asian labourers), retrieved 29 May 2013

- ^ The Chinese American Experience:1857-1892, retrieved 29 May 2013

- ^ a b Eloisa Gomez Borah (1997). "Chronology of Filipinos in America Pre-1989" (PDF). Anderson School of Management. University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

Gonzalez, Joaquin (2009). Filipino American Faith in Action: Immigration, Religion, and Civic Engagement. NYU Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780814732977. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

Jackson, Yo, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Multicultural Psychology. SAGE. p. 216. ISBN 9781412909488. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

Juan Jr., E. San (2009). "Emergency Signals from the Shipwreck". Toward Filipino Self-Determination. SUNY series in global modernity. SUNY Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 9781438427379. Retrieved 11 May 2013. - ^ Martha W. McCartney; Lorena S. Walsh; Ywone Edwards-Ingram; Andrew J. Butts; Beresford Callum (2003). "A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803" (PDF). Historic Jamestowne. National Park Service. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

Francis C.Assisi (16 May 2007). "Indian Slaves in Colonial America". India Currents. Retrieved 11 May 2013. - ^ Slave Trade to Coolie Trade, retrieved 29 May 2013

- ^ Coolie Trade in the 19th Century, retrieved 29 May 2013

- ^ Hugh Tinker (1993). New System of Slavery. Hansib Publishing, London. ISBN 978-1-870518-18-5.

- ^ a b Evelyn Hu-DeHart. "Coolie Labor". University of Colorado. Retrieved June 14 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Forced Labour". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- ^ a b Slave Trade:Coolie Trade (PDF), retrieved 29 May 2013

- ^ "Taste of Peru". Taste of Peru. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Influência da aculturação na autopercepção dos idosos quanto à saúde bucal em uma população de origem japonesa

- ^ Identity, Rebellion, and Social Justice Among Chinese Contract Workers in Nineteenth-Century Cuba

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/cu.html CIA – The World Factbook]. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 2012-05-09.

- ^ Chinese in the English-Speaking Caribbean - Settlements

- ^ Y-chromosomal diversity in Haiti and Jamaica: Contrasting levels of sex-biased gene flow [1]

- ^ DNA study from ancestry24

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2850426/ Strong Maternal Khoisan Contribution to the South African Coloured Population: A Case of Gender-Biased Admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 2010 April 9; 86(4): 611–620. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.014

- ^ "St. Lucia's Indian Arrival Day". Caribbean Repeating Islands. 2009.

- ^ a b "Indian indentured labourers". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- ^ Asia-Canada:Chinese Coolies, retrieved 14 June 2013

- ^ American Involvement in the Coolie Trade (PDF), retrieved 14 June 2013

- ^ Chinese Coolies in Cuba, retrieved 14 June 2013

- ^ Chinese Indentured Labour in Peru, retrieved 14 June 2013

- ^ : Chinese in the English-Speaking Caribbean

- ^ Look Lai, Walton (1998). The Chinese in the West Indies: a documentary history, 1806–1995. The Press University of the West Indies. ISBN 976-640-021-0.

- ^ Li 2004, p. 44

- ^ Robinson 2010, p. 108

- ^ University of Arkansas

- ^ [2] The Chinese in California, 1850–1879

- ^ a b Narvaez, Benjamin N. "Chinese Coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, Labor, and Immigration, 1839–1886." (2010): 1–524. Print.

- ^ a b Significance of Chinese Coolies to Cuba, retrieved 14 June 2013

- ^ Helly, "Idéologie et ethnicité"; Rodríguez Pastor, "Hijos del Celeste Imperio"; Trazegnies Granda, "En el país de las colinas de arena", Tomo II

- ^ Bonilla, Heraclio. 1978. The National and Colonial Problem in Peru. Past & Present.

- ^ Walter Liggett, The Rise of Herbert Hoover (New York, 1932)

- ^ Indian South Africans:Coolie commission 1872, retrieved 29 May 2013

- ^ "Thai Unions Hot under Collar at PM "coolie" Slur." The Star Online. 30 September 2005. Web. 29 Jan 2011.

- ^ Humanitarian Movement Against Child Oppression & Others Living in Exploitation

- ^ "Straattaal Straatwoordenboek: Definitie". Straatwoordenboek.nl. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1756487/

- ^ "Up the Yangtze (Trailer) by Yung Chang - NFB". Films.nfb.ca. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

Further reading

- Williams, Eric. 1962. History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago. Andre Deutsch, London.

- Yule, Henry and Burnell, A. C. (1886): Hobson-Jobson The Anglo-Indian Dictionary. Reprint: Ware, Hertfordshire. Wordsworth Editions Limited. 1996.

- Le grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise, (2001), Vol. III, p. 833.

- Khal Torabully and Marina Carter, Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labour Diaspora Anthem Press, London, 2002 ISBN 1-84331-003-1.

- Lubbock, Basil (1981). The Coolie Ships and Oil Sailers. Brown, Son & Ferguson, Ltd. ISBN 9780851741116. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

External links

This section may contain lists of external links, quotations or related pages discouraged by Wikipedia's Manual of Style. (August 2012) |

- Hill Coolies

- BBC documentary: Coolies: The Story of Indian Slavery

- "Labour and longing" by Vinay Lal

- Personal Life of a Chinese Coolie 1868–1899

- Chinese Coolie treated worse than slaves

- Site dedicated to modern Indian coolies

- India Together article on modern Indian coolies

- Article on Chinese immigration to the USA

- Review of Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labor Diaspora

- Ramya Sivaraj, "A necessary exile", The Hindu (29 April 2007)

- Commemoration of indentured, Aapravasi ghat 2 November 2007.

- In French, starts to dialogue with its History, Khal Torabully

- Description of conditions aboard clipper ships transporting coolies from Swatow, China, to Peru, by George Francis Train

- Use dmy dates from March 2013

- Articles with ibid from May 2010

- Anti-Indian sentiment

- Asian-American issues

- Chinese-American history

- History of immigration to the United States

- Labor history

- Labour relations

- Contract law

- Personal care and service occupations

- Social groups

- History of slavery

- Coolie trade

- Ethnic and religious slurs

- Tamil words and phrases

- Colonialism

- History of India

- 19th century in China

- Slavery

- Anti-Chinese sentiment by country

- Racism

- Pejorative terms for people