Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II: Difference between revisions

→Concerns over performance and safety: Reposition March 2012 paragraph to correct chrono. position. Present version in sequence. |

→Concerns over performance and safety: Include correct date in paragraph and reposition in correct chrono. order. |

||

| Line 137: | Line 137: | ||

* The lightning protection on the F-35 is uncertified, with areas of concern. |

* The lightning protection on the F-35 is uncertified, with areas of concern. |

||

| ⚫ | [[Michael Auslin]] of the [[American Enterprise Institute]] has questioned the capability of the F-35 to engage modern air defenses.<ref>Auslin, Michael. [http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/flying-not-quite-high_642187.html "Flying Not Quite as High."] ''Weekly Standard'', 7 May 2012.</ref> In July 2012, the Pentagon awarded Lockheed $450 million to improve the F-35 electronic warfare systems and incorporate Israeli systems.<ref name="israeli_ew">[http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/u-s-lockheed-martin-reach-deal-on-israeli-f-35-fighter-jets-1.453915 "U.S., Lockheed Martin reach deal on Israeli F-35 fighter jets."] ''Reuters'', 26 July 2012.</ref> |

||

In 2010, Lockheed Martin spokesman John Kent said that adding fire-suppression systems would offer "very small" improvement to survivability.<ref>Shachtman, Noah. [http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2010/06/stealth-fighter-mods-make-it-more-likely-to-get-shot-down/ "Gajillion-Dollar Stealth Fighter, Now Easier to Shoot Down."] ''[[Wired (magazine)|Wired]]'', 11 June 2010.</ref> However, a report released in 2013 stated that flaws in the fuel tank and fueldraulic (fuel-based hydraulic) systems have left it considerably more vulnerable to lightning strikes and other fire sources including enemy fire than previously revealed, especially at lower altitudes.<ref>[http://www.navytimes.com/news/2013/01/defense-f35-vulnerable-lightning-011413/ "Report: Lightning a threat to F-35."] Navy Times</ref> The same report also noted performance degradation of the three variants, the sustained turn rates had been reduced to 4.6 g for the F-35A, 4.5 g for the F-35B, and 5.0 g for the F-35C. The acceleration performance of all three variants was also downgraded, with the F-35C taking 43 seconds longer than an F-16 to accelerate from Mach 0.8 to Mach 1.2; this was judged by several fighter pilots to be a lower performance level than expected from a fourth generation fighter.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/reduced-f-35-performance-specifications-may-have-significant-operational-impact-381683/ |title=Reduced F-35 performance specifications may have significant operational impact |work=Flight International |date=30 January 2013 |accessdate=24 February 2013}}</ref> The F-35 program office is reconsidering addition of previously removed safety equipment.<ref>{{cite web|last=Capaccio |first=Tony |url=http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-07/pentagon-mulls-restoring-f-35-safety-gear-to-reduce-risk.html |title=Pentagon Mulls Restoring F-35 Safety Gear to Reduce Risk. |publisher=Bloomberg |accessdate=24 February 2013}}</ref> In 2012, Lockheed program manager Tom Burbage said that while the relatively large cross-sectional area of the fighter that was required by the internal weapons bays gave it a disadvantage against fourth generation fighters that were operating in a clear configuration, once both fighters were armed the F-35 had the advantage.<ref>[http://www.defensenews.com/article/20120118/DEFREG02/301180013/F-35-May-Miss-Acceleration-Goal "F-35 May Miss Acceleration Goal."]</ref> |

In 2010, Lockheed Martin spokesman John Kent said that adding fire-suppression systems would offer "very small" improvement to survivability.<ref>Shachtman, Noah. [http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2010/06/stealth-fighter-mods-make-it-more-likely-to-get-shot-down/ "Gajillion-Dollar Stealth Fighter, Now Easier to Shoot Down."] ''[[Wired (magazine)|Wired]]'', 11 June 2010.</ref> However, a report released in 2013 stated that flaws in the fuel tank and fueldraulic (fuel-based hydraulic) systems have left it considerably more vulnerable to lightning strikes and other fire sources including enemy fire than previously revealed, especially at lower altitudes.<ref>[http://www.navytimes.com/news/2013/01/defense-f35-vulnerable-lightning-011413/ "Report: Lightning a threat to F-35."] Navy Times</ref> The same report also noted performance degradation of the three variants, the sustained turn rates had been reduced to 4.6 g for the F-35A, 4.5 g for the F-35B, and 5.0 g for the F-35C. The acceleration performance of all three variants was also downgraded, with the F-35C taking 43 seconds longer than an F-16 to accelerate from Mach 0.8 to Mach 1.2; this was judged by several fighter pilots to be a lower performance level than expected from a fourth generation fighter.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/reduced-f-35-performance-specifications-may-have-significant-operational-impact-381683/ |title=Reduced F-35 performance specifications may have significant operational impact |work=Flight International |date=30 January 2013 |accessdate=24 February 2013}}</ref> The F-35 program office is reconsidering addition of previously removed safety equipment.<ref>{{cite web|last=Capaccio |first=Tony |url=http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-07/pentagon-mulls-restoring-f-35-safety-gear-to-reduce-risk.html |title=Pentagon Mulls Restoring F-35 Safety Gear to Reduce Risk. |publisher=Bloomberg |accessdate=24 February 2013}}</ref> In 2012, Lockheed program manager Tom Burbage said that while the relatively large cross-sectional area of the fighter that was required by the internal weapons bays gave it a disadvantage against fourth generation fighters that were operating in a clear configuration, once both fighters were armed the F-35 had the advantage.<ref>[http://www.defensenews.com/article/20120118/DEFREG02/301180013/F-35-May-Miss-Acceleration-Goal "F-35 May Miss Acceleration Goal."]</ref> |

||

| Line 144: | Line 143: | ||

In March 2012, Tom Burbage, and Gary Liberson, of Lockheed Martin addressed an Australian Parliamentary Committee about earlier assessments, stating "Our current assessment that we speak of is greater than 6 to 1 relative loss exchange ratio against, in 4 versus 8 engagement scenarios—4 blue F-35s versus 8 advanced red threats in the 2015 to 2020 time frame. And it is very important to note that is without the pilot in the loop and are the lowest number that we talk about, the greater than 6 to 1 is when we include the pilot in the loop [simulator] activities". They said: "we actually have a fifth-gen airplane flying today. The F22 has been in many exercises and is much better than the simulations forecast. We have F35 flying today; it has not been put into that scenario yet, but we have very high quality information on the capability of the sensors and the capability of the airplane, and we have represented the airplane fairly and appropriately in these large-scale campaign models that we are using. But it is not just us—it is our air force; it is your air force; it is all the other participating nations that do this; it is our navy and our marine corps that do these exercises. It is not Lockheed in a closet gleaning up some sort of result."<ref>[http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Fcommjnt%2F3cb4e326-70e4-4abd-acb7-609a16072b70%2F0001;query=Id%3A%22committees%2Fcommjnt%2F3cb4e326-70e4-4abd-acb7-609a16072b70%2F0000%22 "Department of Defence annual report 2010–11."] ''ParlInfo – Parliamentary Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade,'' 20 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.</ref> |

In March 2012, Tom Burbage, and Gary Liberson, of Lockheed Martin addressed an Australian Parliamentary Committee about earlier assessments, stating "Our current assessment that we speak of is greater than 6 to 1 relative loss exchange ratio against, in 4 versus 8 engagement scenarios—4 blue F-35s versus 8 advanced red threats in the 2015 to 2020 time frame. And it is very important to note that is without the pilot in the loop and are the lowest number that we talk about, the greater than 6 to 1 is when we include the pilot in the loop [simulator] activities". They said: "we actually have a fifth-gen airplane flying today. The F22 has been in many exercises and is much better than the simulations forecast. We have F35 flying today; it has not been put into that scenario yet, but we have very high quality information on the capability of the sensors and the capability of the airplane, and we have represented the airplane fairly and appropriately in these large-scale campaign models that we are using. But it is not just us—it is our air force; it is your air force; it is all the other participating nations that do this; it is our navy and our marine corps that do these exercises. It is not Lockheed in a closet gleaning up some sort of result."<ref>[http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Fcommjnt%2F3cb4e326-70e4-4abd-acb7-609a16072b70%2F0001;query=Id%3A%22committees%2Fcommjnt%2F3cb4e326-70e4-4abd-acb7-609a16072b70%2F0000%22 "Department of Defence annual report 2010–11."] ''ParlInfo – Parliamentary Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade,'' 20 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In May 2012, [[Michael Auslin]] of the [[American Enterprise Institute]] has questioned the capability of the F-35 to engage modern air defenses.<ref>Auslin, Michael. [http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/flying-not-quite-high_642187.html "Flying Not Quite as High."] ''Weekly Standard'', 7 May 2012.</ref> In July 2012, the Pentagon awarded Lockheed $450 million to improve the F-35 electronic warfare systems and incorporate Israeli systems.<ref name="israeli_ew">[http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/u-s-lockheed-martin-reach-deal-on-israeli-f-35-fighter-jets-1.453915 "U.S., Lockheed Martin reach deal on Israeli F-35 fighter jets."] ''Reuters'', 26 July 2012.</ref> |

||

In June 2012, Australia's Air Vice Marshal Osley responded to Air Power Australia's criticisms by saying "Air Power Australia (Kopp and Goon) claim that the F35 will not be competitive in 2020 and that Air Power Australia's criticisms mainly centre around F35's aerodynamic performance and stealth capabilities." Osley continued with, "these are inconsistent with years of detailed analysis that has been undertaken by Defence, the JSF program office, Lockheed Martin, the U.S. services and the eight other partner nations. While aircraft developments such as the [[Sukhoi PAK FA|Russian PAK-FA]] or the [[Chengdu J-20|Chinese J20]], as argued by Airpower Australia, show that threats we could potentially face are becoming increasingly sophisticated, there is nothing new regarding development of these aircraft to change Defence's assessment." He then said that he thinks that the Air Power Australia's "analysis is basically flawed through incorrect assumptions and a lack of knowledge of the classified F-35 performance information."<ref>[http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Fcommjnt%2F2dbe833f-6e45-4a8a-b615-8745dd6f148e%2F0001;query=Id%3A%22committees%2Fcommjnt%2F2dbe833f-6e45-4a8a-b615-8745dd6f148e%2F0000%22 "Department of Defence annual report 2010–1."] ''ParlInfo – Parliamentary Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade,'' 16 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.</ref> |

In June 2012, Australia's Air Vice Marshal Osley responded to Air Power Australia's criticisms by saying "Air Power Australia (Kopp and Goon) claim that the F35 will not be competitive in 2020 and that Air Power Australia's criticisms mainly centre around F35's aerodynamic performance and stealth capabilities." Osley continued with, "these are inconsistent with years of detailed analysis that has been undertaken by Defence, the JSF program office, Lockheed Martin, the U.S. services and the eight other partner nations. While aircraft developments such as the [[Sukhoi PAK FA|Russian PAK-FA]] or the [[Chengdu J-20|Chinese J20]], as argued by Airpower Australia, show that threats we could potentially face are becoming increasingly sophisticated, there is nothing new regarding development of these aircraft to change Defence's assessment." He then said that he thinks that the Air Power Australia's "analysis is basically flawed through incorrect assumptions and a lack of knowledge of the classified F-35 performance information."<ref>[http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Fcommjnt%2F2dbe833f-6e45-4a8a-b615-8745dd6f148e%2F0001;query=Id%3A%22committees%2Fcommjnt%2F2dbe833f-6e45-4a8a-b615-8745dd6f148e%2F0000%22 "Department of Defence annual report 2010–1."] ''ParlInfo – Parliamentary Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade,'' 16 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 04:48, 5 September 2013

| F-35 Lightning II | |

|---|---|

| |

| An F-35C Lightning II, marked CF-1, conducts a test flight over the Chesapeake Bay in February 2011 | |

| Role | Stealth multirole fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin Aeronautics |

| First flight | 15 December 2006 |

| Introduction | December 2015 (USMC F-35B)[1][2] December 2016 (USAF F-35A)[2] February 2019 (USN F-35C)[2] |

| Status | In initial production and testing, used for training by U.S.[3] |

| Primary users | United States Air Force United States Marine Corps United States Navy Royal Air Force |

| Produced | 2006–present |

| Number built | 63[4] |

| Developed from | Lockheed Martin X-35 |

The Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II is a family of single-seat, single-engine, fifth generation multirole fighters under development to perform ground attack, reconnaissance, and air defense missions with stealth capability.[5][6] The F-35 has three main models; the F-35A is a conventional takeoff and landing variant, the F-35B is a short take-off and vertical-landing variant, and the F-35C is a carrier-based variant.

The F-35 is descended from the X-35, the product of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program. It is being designed and built by an aerospace industry team led by Lockheed Martin. The F-35 took its first flight on 15 December 2006. The United States plans to buy 2,443 aircraft. The F-35 variants are intended to provide the bulk of its tactical airpower for the U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps and Navy over the coming decades.

JSF development is being principally funded by the United States with additional funding from partners. The partner nations are either NATO members or close U.S. allies. The United Kingdom, Italy, Israel, The Netherlands, Australia, Canada, Norway, Denmark, and Turkey are part of the development program; Japan has ordered the F-35, while Singapore may also equip their air force with the F-35.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13]

Development

JSF Program requirements and selection

The JSF program was designed to replace the United States military F-16, A-10, F/A-18 (excluding newer E/F "Super Hornet" variants) and AV-8B tactical fighter aircraft. To keep development, production, and operating costs down, a common design was planned in three variants that share 80 percent of their parts:

- F-35A, conventional take off and landing (CTOL) variant.

- F-35B, short-take off and vertical-landing (STOVL) variant.

- F-35C, carrier-based CATOBAR (CV) variant.

George Standridge of Lockheed Martin predicted in 2006 that the F-35 will be four times more effective than legacy fighters in air-to-air combat, eight times more effective in air-to-ground combat, and three times more effective in reconnaissance and suppression of air defenses – while having better range and requiring less logistics support and having around the same procurement costs (if development costs are ignored) as legacy fighters.[14] The design goals call for the F-35 to be the premier strike aircraft through 2040 and be second only to the F-22 Raptor in air superiority.[15]

The JSF development contract was signed on 16 November 1996, and the contract for System Development and Demonstration (SDD) was awarded on 26 October 2001 to Lockheed Martin, whose X-35 beat the Boeing X-32. Although both aircraft met or exceeded requirements, the X-35 design was considered to have less risk and more growth potential.[16] The designation of the new fighter as "F-35" is out-of-sequence with standard DoD aircraft numbering,[17] by which it should have been "F-24". It came as a surprise even to Lockheed, which had been referring to the aircraft in-house by this expected designation.[18]

The development of the F-35 is unusual for a fighter aircraft in that no two-seat trainer versions have been built for any of the variants; advanced flight simulators mean that no trainer versions were deemed necessary.[19] Instead F-16s have been used as bridge trainers between the T-38 and the F-35. The T-X was intended to be used to train future F-35 pilots, but this might succumb to budget pressures in the USAF.[20]

Design phase

Based on wind tunnel testing, Lockheed Martin slightly enlarged its X-35 design into the F-35. The forward fuselage is 5 inches (130 mm) longer to make room for avionics. Correspondingly, the horizontal stabilators were moved 2 inches (51 mm) rearward to retain balance and control. The top surface of the fuselage was raised by 1 inch (25 mm) along the center line. Also, it was decided to increase the size of the F-35B STOVL variant's weapons bay to be common with the other two variants.[16] Manufacturing of parts for the first F-35 prototype airframe began in November 2003.[21] Because the X-35 did not have weapons bays, their addition in the F-35 would cause design changes which would lead to later weight problems.[22][23]

The F-35B STOVL variant was in danger of missing performance requirements in 2004 because it weighed too much; reportedly, by 2,200 lb (1,000 kg) or 8 percent. In response, Lockheed Martin added engine thrust and thinned airframe members; reduced the size of the common weapons bay and vertical stabilizers; re-routed some thrust from the roll-post outlets to the main nozzle; and redesigned the wing-mate joint, portions of the electrical system, and the portion of the aircraft immediately behind the cockpit.[24] Many of the changes were applied to all three variants to maintain high levels of commonality. By September 2004, the weight reduction effort had reduced the aircraft's design weight by 2,700 pounds (1,200 kg).[25] but the redesign cost $6.2 billion and delayed the project by 18 months.[26]

On 7 July 2006, the U.S. Air Force officially announced the name of the F-35: Lightning II, in honor of Lockheed's World War II-era twin-prop Lockheed P-38 Lightning and the Cold War-era jet, the English Electric Lightning.[27][N 1][29] English Electric Company's aircraft division was a predecessor of F-35 partner BAE Systems. Lightning II was also an early company name for the fighter that was later named the F-22 Raptor.[citation needed]

Lockheed Martin Aeronautics is the prime contractor and performs aircraft final assembly, overall system integration, mission system, and provides forward fuselage, wings and flight controls system. Northrop Grumman provides Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar, electro-optical Distributed Aperture System (DAS), Communications, Navigation, Identification (CNI), center fuselage, weapons bay, and arrestor gear. BAE Systems provides aft fuselage and empennages, horizontal and vertical tails, crew life support and escape systems, Electronic warfare systems, fuel system, and Flight Control Software (FCS1). Alenia will perform final assembly for Italy and, according to an Alenia executive, assembly of all European aircraft with the exception of Turkey and the United Kingdom.[30][31] The F-35 program has seen a great deal of investment in automated production facilities. For example, Handling Specialty produced the wing assembly platforms for Lockheed Martin.[32] In November 2009, Jon Schreiber, head of F-35 international affairs program for the Pentagon, said that the U.S. will not share the software code for the F-35 with its allies.[33]

On 19 December 2008, Lockheed Martin rolled out the first weight-optimized F-35A (designated AF-1). It was the first F-35 built at full production speed, and is structurally identical to the production F-35As that were delivered starting in 2010.[34] On 5 January 2009, six F-35s had been built, including AF-1 and AG-1; another 13 pre-production test aircraft and four production aircraft were being manufactured.[35] On 6 April 2009, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates proposed speeding up production for the U.S. to buy 2,443 F-35s.[36] In August 2010, Lockheed Martin announced delays in resolving a "wing-at-mate overlap" production problem, which would slow initial production.[37]

Program cost increases and further delays through 2012

Since 2006, the program has been subject to re-scoping and a number of reassessments. These are summarized below as the history of the program up to December 2012 and current status after January 2013.

In 2006, the GAO warned that excessive concurrency between the production of additional F-35 aircraft and testing of their design might result in expensive refits for several hundred aircraft planned to be produced before completion of tests.[38] In November 2010, the GAO found that "Managing an extensive, still-maturing global network of suppliers adds another layer of complexity to producing aircraft efficiently and on-time" and that "due to the extensive amount of testing still to be completed, the program could be required to make alterations to its production processes, changes to its supplier base, and costly retrofits to produced and fielded aircraft, if problems are discovered."[39] USAF budget data in 2010, along with other sources, projected the F-35 to have a flyaway cost from US$89 million to US$200 million over the planned production run.[40][41][42] In February 2011, the Pentagon put a price of $207.6 million on each of the 32 aircraft to be acquired in FY2012, rising to $304.15 million ($9,732.8/32) if its share of RDT&E spending is included.[43][44]

On 21 April 2009, media reports, citing Pentagon sources, said that during 2007 and 2008, spies had copied and siphoned off several terabytes of data related to the F-35's design and electronics systems, potentially compromising the aircraft and aiding the development of defense systems against it.[45] Lockheed Martin rejected suggestions that the project was compromised, stating it "does not believe any classified information had been stolen".[46] Other sources suggested that the incident caused both hardware and software redesigns to be more resistant to cyber attack.[47] BAE Systems was reported to be the target of cyber espionage.[48] In February 2013, it was feared that China had intercepted telemetry from F-35 test flights.[49] In 2013, a report from Mandiant tracked the hacking to a unit of the People's Liberation Army.[50]

On 9 November 2009, Ashton Carter, under-secretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics, acknowledged that the Pentagon "joint estimate team" (JET) had found possible future cost and schedule overruns in the project and that he would be holding meetings to attempt to avoid these.[51] On 1 February 2010, Gates removed the JSF Program Manager, U.S. Marine Corps Major General David Heinz, and withheld $614 million in payments to Lockheed Martin because of program costs and delays.[52][53]

On 11 March 2010, a report from the Government Accountability Office to United States Senate Committee on Armed Services projected the overall unit cost of an F-35A to be $112M in today's money.[54] In 2010, Pentagon officials disclosed that the F-35 program has exceeded its original cost estimates by more than 50 percent.[55] An internal Pentagon report critical of the JSF project states that "affordability is no longer embraced as a core pillar". In 2010, Lockheed Martin expected to reduce government cost estimates by 20%.[56] On 24 March 2010, Gates termed the cost overruns and delays as "unacceptable" in a testimony before the U.S. Congress; and characterized previous cost and schedule estimates as "overly rosy". Gates insisted the F-35 would become "the backbone of U.S. air combat for the next generation" and informed the Congress that he had expanded the development period by an additional 13 months and budgeted $3 billion more for the testing program while slowing down production.[57]

In November 2010, as part of a cost-cutting measure, the co-chairs of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform suggested cancelling the F-35B and halving orders of F-35As and F-35Cs.[58][59][60] Air Force Magazine reported that "Pentagon officials" were considering canceling the F-35B because its short range meant that the bases or ships it would operate from would be in range of hostile tactical ballistic missiles.[61] Lockheed Martin consultant Loren B. Thompson said that this rumor was a result of the usual tensions between the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, and there was no alternative to the F-35B as an AV-8B Harrier II replacement.[62] He also confirmed further delays and cost increases because of technical problems with the aircraft and software, blaming most of the delays and extra costs on redundant flight tests.[63]

In November 2010, the Center for Defense Information estimated that the program would be restructured with an additional year of delay and $5 billion in additional costs.[64] On 5 November 2010, the Block 1 software flew for the first time on BF-4.[65] As of the end of 2010, only 15% of the software remained to be written, but this was reported to include the most difficult sections such as data fusion.[66] In 2011, it was revealed that 50% of the eight million lines of code had been written and that it would take another six years to complete the software to the new schedule.[67] By 2012, the total estimated lines of code for the entire program (onboard and offboard) had grown from 15 million lines to 24 million lines.[68]

In 2011, program head Vice Adm. David Venlet confirmed that the concurrency built into the program "was a miscalculation".[69] This was during a contract dispute where the Pentagon insisted that Lockheed Martin help cover the costs of applying fixes found during testing to aircraft already produced.[70] Lockheed Martin objected that the cost sharing posed an uninsurable unbounded risk that the company could not cover, and later responded that the "concurrency costs for F-35 continue to reduce".[71][72] The Senate Armed Services Committee strongly backed the Pentagon position.[73] In December 2011, Lockheed Martin accepted a cost sharing agreement.[74] The Aerospace Industries Association warned that such changes would force them to anticipate cost overruns in future contract bids.[75] As of 2012, problems found in flight testing were expected to continue to lead to higher levels of engineering changes through 2019.[76] The total additional cost for concurrency in the program is around $1.3 billion.[77] By the next year the cost had grown to $1.7 billion.[78]

In January 2011, Defense Secretary Robert Gates expressed the Pentagon's frustration with the rising costs of the F-35 program when he said "The culture of endless money that has taken hold must be replaced by a culture of restraint." Focusing his attention on the troubled F-35B, Gates ordered "a two-year probation", saying it "should be canceled" if corrections are unsuccessful.[79] Gates has stated his support for the program.[80] Some private analysts, such as Richard Aboulafia, of the Teal Group state that the F-35 program is becoming a money pit.[81] Gates' successor, Leon Panetta, ended the F-35B's probation on 20 January 2012, stating "The STOVL variant has made — I believe and all of us believe — sufficient progress."[82]

Former Pentagon manager Paul G. Kaminski has said that the lack of a complete test plan has added five years to the JSF program.[83] Initial operating capability (IOC) will be determined by software development rather than by hardware production or pilot training.[84] As of May 2013[update] the USMC plan an IOC in "mid-2015"[2] for the F-35B with Block 2B software which gives basic air-to-air and air-to-ground capability.[2] It has been reported that the USAF is planning to bring forward IOC for the F-35A to the Block 3I software in mid-2016 rather than waiting for the full-capability Block 3F in mid-2017;[2] the F-35C will not enter service with the USN until mid-2018.[2] The $56.4 billion development project for the aircraft should be completed in 2018 when the block five configuration is expected to be delivered, several years late and considerably over budget.[85]

Delays in the F-35 program may lead to a "fighter gap" where America and other countries will lack sufficient fighters to cover their requirements.[86] Israel may seek to buy second-hand F-15s,[87] while Australia also sought additional Super Hornets in the face of F-35 delays.[88]

In May 2011, the Pentagon's top weapons buyer Ashton Carter said that its new $133 million unit price was not affordable.[89] In 2011, The Economist warned that the F-35 was in danger of slipping into a "death spiral" where increasing per-aircraft costs would lead to cuts in number of aircraft ordered, leading to further cost increases and further order cuts.[90] Later that year, four aircraft were cut from the fifth LRIP order to pay for cost overruns;[91] in 2012, a further two aircraft were cut.[92] Lockheed acknowledged that the slowing of purchases would increase costs.[93] David Van Buren, U.S. Air Force acquisition chief, said that Lockheed needed to cut infrastructure to match the reduced market for their aircraft.[94] The company said that the slowdown in American orders will free up capacity to meet the urgent short term needs of foreign partners for replacement fighters.[95] Air Force Secretary Michael Donley said that no more money was available and that future price increases would be matched with cuts in the number of aircraft ordered.[96] Later that month, the Pentagon reported that costs had risen another 4.3 percent, partially resulting from production delays.[97] In 2012, the purchase of six out of 31 aircraft was tied to performance metrics of the program.[98] In 2013 Bogdan repeated that no more money was available, but that he hoped to avoid the death spiral.[99]

Japan has warned that it may halt their purchase if unit costs increase, and Canada has indicated it is not committed to a purchase yet.[100][101] The United States is projected to spend an estimated US$323 billion for development and procurement on the program, making it the most expensive defense program ever.[102] Testifying before a Canadian parliamentary committee in 2011, Rear Admiral Arne Røksund of Norway estimated that his country's 52 F-35 fighter jets will cost $769 million each over their operational lifetime.[103]

The total life-cycle cost for the entire American fleet is estimated to be US$1.51 trillion over its 50-year life, or $618 million per plane.[104] In order to reduce the estimated $1 trillion cost of the F-35 over its 50-year lifetime, the USAF is considering reducing Lockheed's role in Contractor Logistics Support.[105] Lockheed has responded that the trillion dollar estimate relies on future costs beyond its control such as USAF reorganizations and yet to be specified upgrades.[106] Delays have negatively affected the program's worldwide supply chain and partner organisations.[107]

In 2012, General Norton A. Schwartz decried the "foolishness" of reliance on computer models to settle the final design of the aircraft before flight testing found the issues that needed redesign.[108] In 2013, JSF project team leader USAF Lieutenant General Chris Bogdan said that "A large amount of concurrency, that is, beginning production long before your design is stable and long before you've found problems in test, creates downstream issues where now you have to go back and retrofit airplanes and make sure the production line has those fixes in them. And that drives complexity and cost".[109] Bogdan did however praise the "magical" improvement in the program ever since Lockheed was forced to assume some of the financial risks.[110]

In 2012, in order to avoid further redesign delays, the U.S. DoD accepted a reduced combat radius for the F-35A and a longer takeoff run for the F-35B.[111][112] The F-35B's estimated radius has also decreased by 15 percent.[113] In a meeting in Sydney in March, the United States pledged to eight partner nations that there would be no more program delays.[114]

In May 2012, Lockheed Chief Executive Bob Stevens complained that the Defense Department's requirements for cost data were driving up program cost.[115] Stevens also admitted that a strike might cause a production shortfall of the target of 29 F-35s that year.[116] Striking workers questioned the standards of replacement workers, as even their own work had been cited for "inattention to production quality" with a 16% rework rate.[117] The workers went on strike to protect pensions whose costs have been the subject of negotiations with the Department of Defense over the next batch of aircraft.[118] These same pension costs were cited by Fitch in their downgrade of the outlook for Lockheed Martin's stock price.[119] Stevens said that while he hoped to bring down program costs, the industrial base was not capable of meeting the government's expectations of affordability.[120][121]

According to a June 2012 Government Accountability Office report, the F-35's unit cost has almost doubled, an increase of 93% over the program's 2001 baseline cost estimates.[122] In 2012, Lockheed reportedly feared that the tighter policies for award fees of the Obama administration would reduce their profits by $500 million over the following five years.[123] This was demonstrated in 2012 when the Pentagon withheld the maximum $47 million allowed for Lockheed's failure to certify its program to track project costs and schedules.[124] The GAO has also faulted the USAF and USN for not fully planning the costs of extending legacy F-16 and F-18 fleets to cover for the delayed F-35.[125] Due to cost cutting measures, the US Government and the GAO have stated that the flyaway cost (including engines) has been dropping. The US Government estimates that in 2020 a "F-35 will cost some $85m each or less than half of the 2009 initial examples cost. Adjusted to today’s dollars the 2020 price would be $75m each."[126]

Program cost increases and delays after January 2013

In 2013 Lockheed began to lay off workers at the Fort Worth plant where the F-35s were assembled.[127] They said that the currently estimated concurrency costs of refitting the 187 aircraft built by the time testing concludes in 2016 are now less than previously feared.[128] The GAO's Michael Sullivan said that Lockheed had failed to get an early start on the systems engineering and had not understood the requirements or the technologies involved at the program's start.[129] The Pentagon vowed to continue funding the program during budget sequestration if possible.[130] The United States Congress responded with the Budget Control Act of 2011, which may derail the software needed to complete the F-35 program.[131]

In June 2013, Frank Kendall, Pentagon acquisition, technology and logistics chief, declared “major advances” had been made in the F-35 program over the last three years; and that he intended approve production rate increases in September. Air Force Lt. Gen. Christopher Bogdan, program executive officer, reported far better communications between government and vendor managers, and that negotiations over Lot 6 and 7 talks were moving fast. It was also stated that operating costs had been better understood since training started, and he predicted “we can make a substantial dent in projections” of operating costs.[132]

In July 2013, further doubt was cast on the latest (long delayed) schedule, with further software delays, and sensor, display and wing buffet problems continuing.[133] In August it was revealed that the Pentagon was weighing cancellation of the program as one possible response to the Budget sequestration in 2013,[134][135] and the United States Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense voted to cut advanced procurement for the fighter.[136]

On 21 August 2013 C-Span reported that Congressional Quarterly and the Government Accountability Office were indicating the "Total estimated program cost now $400B--nearly twice initial cost." The Current investment was documented as approximately fifty (50) billion dollars. The Projected $316 billion dollar cost in development and procurement spending was estimated through 2037 at an average of $12.6 billion dollars per year. These were confirmed by Steve O'Bryan, Vice President of Lockheed Martin on the same date.[137]

Concerns over performance and safety

Considerable criticism followed in the wake of US Ambassador Tom Schieffer's confirmation to the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs (JSCFADT) on 21 June 2004: "With regard to the stealth technology, the airplane that Australia will get will be the stealthiest airplane that anybody outside the United States can acquire. We have given assurances to Australia that we will give you the absolute maximum that we can with regard to that technology. Having said that, the airplane will not be exactly the same airplane as the United States will have. But it will be a stealth fighter; it will have stealth capabilities; and it will be at the highest level that anyone in the world has outside the United States." The F-35's stealth would be similar to contemporary aircraft.[citation needed][138][139][140] A follow on article by Lockheed Martin's Tom Burbage stated that the US would not export key technologies such as stealth.[141] Before, a Jane's article gave a hint that US$1B, spent on several contracts, would serve to protect stealth technology and probably provide for a less stealthy export configuration of the fighter.[142]

In 2006, the F-35 was downgraded from "very low observable" to "low observable", a change former RAAF flight test engineer Peter Goon likened to increasing the radar cross section from a marble to a beach ball.[143] A Parliamentary Inquiry asked what was the re-categorization of the terminology in the United States such that the rating was changed from "very low observable" to "low observable". The Department of Defence said that the change in categorization by the U.S. was due to a revision in procedures for discussing stealth platforms in a public document. Decision to re-categorize in the public domain has now been reversed; subsequent publicly released material has categorized the JSF as very low observable (VLO).[144]

Andrew Krepinevich has questioned the reliance on "short range" aircraft like the F-35 or F-22 to "manage" China in a future conflict and has suggested reducing the number of F-35s ordered in favor of a longer range platform like the Next-Generation Bomber, but Michael Wynne, then United States Secretary of the Air Force rejected this plan of action in 2007.[145][146][147] By 2012, Wynne had conceded that America's short ranged fifth generation fighters would need drop tanks in order to be effective.[148] In 2011, the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) pointed to the restructuring of the F-35 program and the return of the bomber project as a sign of their effectiveness, while Rebecca Grant said that the restructuring was a "vote of confidence" in the F-35 and "there is no other stealthy, survivable new fighter program out there".[149] Lockheed has also said that the F-35 is designed to launch internally carried bombs at supersonic speed and internal missiles at maximum supersonic speed.[150]

In 2008, it was reported that RAND Corporation conducted simulated war games in which Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighters defeated the F-35.[151][152] During a formal briefing by the Australian Department of Defence to the Australian defence minister Joel Fitzgibbon, it was stated that reports of the simulation were inaccurate and did not compare the F-35's flight performance against other aircraft.[153] The Pentagon and Lockheed Martin also stated that these simulations did not address air-to-air combat.[154][155] A Lockheed Martin press release points to USAF simulations regarding the F-35's air-to-air performance against adversaries described as "4th generation" fighters, in which it claims the F-35 is "400 percent" more effective. Major General Charles R. Davis, USAF, the F-35 program executive officer, has stated that the "F-35 enjoys a significant Combat Loss Exchange Ratio advantage over the current and future air-to-air threats, to include Sukhois".[155]

In September 2008, in reference to the original plan to fit the F-35 with only two air-to-air missiles (internally), Major Richard Koch, chief of USAF Air Combat Command’s advanced air dominance branch is reported to have said that "I wake up in a cold sweat at the thought of the F-35 going in with only two air-dominance weapons."[156] The Norwegians have been briefed on a plan to equip the F-35 with six AIM-120D missiles by 2019.[157] Former RAND author John Stillion has written of the F-35A's air-to-air combat performance that it “can’t turn, can’t climb, can’t run”; Lockheed Martin test pilot Jon Beesley has stated that in an air-to-air configuration the F-35 has almost as much thrust as weight and a flight control system that allows it to be fully maneuverable even at a 50-degree angle of attack.[158][159][160] Consultant to Lockheed Martin Loren B. Thompson has said that the "electronic edge F-35 enjoys over every other tactical aircraft in the world may prove to be more important in future missions than maneuverability".[161]

In an April 2009 interview with the state-run[162] Global Times, Chen Hu, editor-in-chief of World Military Affairs magazine has said that the F-35 is too costly because it attempts to provide the capabilities needed for all three American services in a common airframe.[163] U.S. defense specialist Winslow T. Wheeler and aircraft designer Pierre Sprey have commented of the F-35 being "heavy and sluggish" and possessing "pitifully small load for all that money", further criticizing the value for money of the stealth measures as well as lacking fire safety measures; his final conclusion was that any air force would be better off maintaining its fleets of F-16s and F/A-18s compared to buying into the F-35 program.[164] A senior U.S. defense official was quoted as saying that the F-35 will be "the most stealthy, sophisticated and lethal tactical fighter in the sky," and added "Quite simply, the F-15 will be no match for the F-35."[165] After piloting the aircraft, RAF Squadron Leader Steve Long said that, over its existing aircraft, the F-35 will give "the RAF and Navy a quantum leap in airborne capability."[166]

In 2011, Canadian politicians raised the issue of the safety of the F-35's reliance on a single engine (as opposed to a twin-engine configuration, which provides a backup in case of an engine failure). Canada, and other operators, had previous experience with a high-accident rate with the single-engine Lockheed CF-104 Starfighter with many accidents related to engine failures. Defence Minister Peter MacKay, when asked what would happen if the F-35's single engine fails in the Far North, stated "It won’t".[167]

In November 2011, a Pentagon study team identified the following 13 areas of concern that remained to be addressed in the F-35:[168][169]

- The helmet-mounted display system does not work properly.

- The fuel dump subsystem poses a fire hazard.

- The Integrated Power Package is unreliable and difficult to service.

- The F-35C's arresting hook does not work.

- Classified "survivability issues", which have been speculated to be about stealth.[168]

- The wing buffet is worse than previously reported.

- The airframe is unlikely to last through the required lifespan.

- The flight test program has yet to explore the most challenging areas.

- The software development is behind schedule.

- The aircraft is in danger of going overweight or, for the F-35B, not properly balanced for VTOL operations.

- There are multiple thermal management problems. The air conditioner fails to keep the pilot and controls cool enough, the roll posts on the F-35B overheat, and using the afterburner damages the aircraft.

- The automated logistics information system is partially developed.

- The lightning protection on the F-35 is uncertified, with areas of concern.

In 2010, Lockheed Martin spokesman John Kent said that adding fire-suppression systems would offer "very small" improvement to survivability.[170] However, a report released in 2013 stated that flaws in the fuel tank and fueldraulic (fuel-based hydraulic) systems have left it considerably more vulnerable to lightning strikes and other fire sources including enemy fire than previously revealed, especially at lower altitudes.[171] The same report also noted performance degradation of the three variants, the sustained turn rates had been reduced to 4.6 g for the F-35A, 4.5 g for the F-35B, and 5.0 g for the F-35C. The acceleration performance of all three variants was also downgraded, with the F-35C taking 43 seconds longer than an F-16 to accelerate from Mach 0.8 to Mach 1.2; this was judged by several fighter pilots to be a lower performance level than expected from a fourth generation fighter.[172] The F-35 program office is reconsidering addition of previously removed safety equipment.[173] In 2012, Lockheed program manager Tom Burbage said that while the relatively large cross-sectional area of the fighter that was required by the internal weapons bays gave it a disadvantage against fourth generation fighters that were operating in a clear configuration, once both fighters were armed the F-35 had the advantage.[174]

In December 2011, the Pentagon and Lockheed came to an agreement to assure funding and delivery for a fifth order of early F-35 aircraft of yet undefined type.[175] On 22 February 2013, the fledgling F-35 fleet was grounded after a routine inspection of a F-35A at Edwards Air Force Base found a crack in an engine turbine blade.[176][177]

In March 2012, Tom Burbage, and Gary Liberson, of Lockheed Martin addressed an Australian Parliamentary Committee about earlier assessments, stating "Our current assessment that we speak of is greater than 6 to 1 relative loss exchange ratio against, in 4 versus 8 engagement scenarios—4 blue F-35s versus 8 advanced red threats in the 2015 to 2020 time frame. And it is very important to note that is without the pilot in the loop and are the lowest number that we talk about, the greater than 6 to 1 is when we include the pilot in the loop [simulator] activities". They said: "we actually have a fifth-gen airplane flying today. The F22 has been in many exercises and is much better than the simulations forecast. We have F35 flying today; it has not been put into that scenario yet, but we have very high quality information on the capability of the sensors and the capability of the airplane, and we have represented the airplane fairly and appropriately in these large-scale campaign models that we are using. But it is not just us—it is our air force; it is your air force; it is all the other participating nations that do this; it is our navy and our marine corps that do these exercises. It is not Lockheed in a closet gleaning up some sort of result."[178]

In May 2012, Michael Auslin of the American Enterprise Institute has questioned the capability of the F-35 to engage modern air defenses.[179] In July 2012, the Pentagon awarded Lockheed $450 million to improve the F-35 electronic warfare systems and incorporate Israeli systems.[180]

In June 2012, Australia's Air Vice Marshal Osley responded to Air Power Australia's criticisms by saying "Air Power Australia (Kopp and Goon) claim that the F35 will not be competitive in 2020 and that Air Power Australia's criticisms mainly centre around F35's aerodynamic performance and stealth capabilities." Osley continued with, "these are inconsistent with years of detailed analysis that has been undertaken by Defence, the JSF program office, Lockheed Martin, the U.S. services and the eight other partner nations. While aircraft developments such as the Russian PAK-FA or the Chinese J20, as argued by Airpower Australia, show that threats we could potentially face are becoming increasingly sophisticated, there is nothing new regarding development of these aircraft to change Defence's assessment." He then said that he thinks that the Air Power Australia's "analysis is basically flawed through incorrect assumptions and a lack of knowledge of the classified F-35 performance information."[181]

In March 2013 USAF test pilots noted a lack of visibility from the F-35 cockpit during evaluation flights and said that this will get them consistently shot down in combat. Defense spending analyst Winslow Wheeler concluded from the flight evaluation reports that the F-35A "is flawed beyond redemption";[182] in response, program manager Bogdan suggested that pilots worried about being shot down should fly cargo aircraft instead.[183] The same report found (in addition to the usual problems with the aircraft listed above):

- Current aircraft software is inadequate for even basic pilot training.

- Ejection seat may fail causing pilot fatality.

- Several pilot-vehicle interface issues, including lack of feedback on touch screen controls.

- The radar performs poorly or not at all.

- Engine replacement takes an average of 52 hours, instead of the two hours specified.

- Maintenance tools do not work.[184]

The JPO responded that more experienced pilots would be able to safely operate the aircraft and that procedures would improve over time.[185]

Even in the final "3F" software version, the F-35 will lack ROVER, in spite of having close air support as one of its primary missions.[186]

The F-35B and F-35C models take several complex maneuvers to reach their top speed of Mach 1.6, which consume almost all of the onboard fuel.[187]

Problems with Lockheed Martin

In September 2012, the Pentagon criticized, quite publicly, Lockheed Martin's performance on the F-35 program and stated that it would not bail out the program again if problems with the plane's systems, particularly the helmet-mounted display, were not resolved. The deputy F-35 program manager said that the government's relationship with the company was the "worst I've ever seen" in many years of working on complex acquisition programs. Air Force Secretary Michael Donley told reporters the Pentagon had no more money to pour into the program after three costly restructurings in recent years. He said the department was done with major restructuring and that there was no further flexibility or tolerance for that approach. This criticism followed a "very painful" 7 September review that focused on an array of ongoing program challenges. Lockheed Martin responded with a brief statement saying it would continue to work with the F-35 program office to deliver the new fighter.[188]

On 28 September 2012, the Pentagon announced that the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter support program would become an open competition. They invited companies to participate in a two-day forum on 14–15 November for possible opportunities to compete for work managing the supply chain of the aircraft. Their reason is to reduce F-35 life-cycle costs by creating competition within the program and to refine its acquisition strategy and evaluate alternatives that will deliver the best value, long-term F-35 sustainment solution. This could be hazardous to Lockheed, as they are the current prime contractor for sustainment of all three variants, and selection of another company could reduce their revenues.[189]

In 2013, the officer in charge of the program blamed Lockheed and Pratt & Whitney for gouging the government on costs, instead of focusing on the long term future of the program.[190]

Upgrades

Lockheed's development roadmap extends until 2021, including a block 6 engine improvement in 2019. The aircraft are expected to be upgraded throughout their operational lives.[191]

Design

Overview

The F-35 appears to be a smaller, single-engine sibling of the twin-engine Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor, and indeed drew elements from it. The exhaust duct design was inspired by the General Dynamics Model 200 design, which was proposed for a 1972 supersonic VTOL fighter requirement for the Sea Control Ship.[192] Lockheed consulted with the Yakovlev Design Bureau in the development of the F-35B STOVL variant, purchasing design data from their development of the Yakovlev Yak-141 "Freestyle".[193][194] Although several experimental designs have been developed since the 1960s, such as the unsuccessful Rockwell XFV-12, the F-35B is to be the first operational supersonic, STOVL stealth fighter.[195]

Acquisition deputy to the assistant secretary of the Air Force, Lt. Gen. Mark D. "Shack" Shackelford has said that the F-35 is designed to be America's "premier surface-to-air missile killer and is uniquely equipped for this mission with cutting edge processing power, synthetic aperture radar integration techniques, and advanced target recognition."[196][197] Lockheed Martin claims the F-35 is intended to have close- and long-range air-to-air capability second only to that of the F-22 Raptor.[5] Lockheed Martin has said that the F-35 has the advantage over the F-22 in basing flexibility and "advanced sensors and information fusion".[198] Lockheed has suggested that the F-35 could replace the USAF's F-15C/D fighters in the air superiority role and the F-15E Strike Eagle in the ground attack role, although the F-35 lacks the range or payload of the F-15.[199] The F-35A carries a similar air-to-air armament as the conceptual Boeing F-15SE Silent Eagle when both aircraft are configured for low observable operations, having roughly 80 percent of the F-15SE's combat radius under those conditions.[200]

Some improvements over current-generation fighter aircraft are:

- Durable, low-maintenance stealth technology, using structural fiber mat instead of the high-maintenance coatings of legacy stealth platforms;[201]

- Integrated avionics and sensor fusion that combine information from off- and on-board sensors to increase the pilot's situational awareness and improve target identification and weapon delivery, and to relay information quickly to other command and control (C2) nodes;

- High speed data networking including IEEE 1394b[202] and Fibre Channel.[203] (Fibre Channel is also used on Boeing's Super Hornet.[204])

- The Autonomic Logistics Global Sustainment (ALGS), Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS) and Computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) are to help ensure aircraft uptime with minimal maintenance manpower.[205] The Pentagon has moved to open up the competitive bidding by other companies.[206] This was after Lockheed admitted that instead of costing twenty percent less than the F-16 per flight hour, the F-35 would actually cost twelve percent more.[207] Though the ALGS is intended to reduce maintenance costs, Lockheed Martin disagrees with including the cost of this system in the aircraft ownership calculations.[208] USMC have implemented a workaround for a cyber vulnerability in the system.[209]

- Electrohydrostatic actuators run by a power-by-wire flight-control system.[210]

- A modern and updated flight simulator, which may be used for a greater fraction of pilot training in order to reduce the costly flight hours of the actual aircraft.[211]

- Lightweight, powerful and volatile Lithium-ion batteries similar to those that have grounded the Boeing 787 Dreamliner fleet.[212] These are required to provide power to run the control surfaces in an emergency,[213] and have been strenuously tested.[214]

Structural composites in the F-35 are 35% of the airframe weight (up from 25% in the F-22).[215] The majority of these are bismaleimide (BMI) and composite epoxy material.[216] The F-35 will be the first mass produced aircraft to include structural nanocomposites, namely carbon nanotube reinforced epoxy.[217] Experience of the F-22's problems with corrosion lead to the F-35 using a gap filler that causes less galvanic corrosion to the airframe's skin, designed with fewer gaps requiring filler and implementing better drainage.[218] The relatively short 35-foot wingspan of the A and B variants is set by the F-35B's requirement to fit inside the Navy's current amphibious assault ship elevators; the F-35C's longer wing is considered to be more fuel efficient.[219]

A United States Navy study found that the F-35 will cost 30 to 40 percent more to maintain than current jet fighters;[220] not accounting for inflation over the F-35's operational lifetime. A Pentagon study concluded a $1 trillion maintenance cost for the entire fleet over its lifespan.[221]

Engines

The engine used on the F-35 is the Pratt & Whitney F135. An alternative engine, the General Electric/Rolls-Royce F136, was under development until December 2011 when the manufacturers canceled the project.[222][223] Neither the F135 or F136 engines are designed to supercruise in the F-35,[224] however the F-35 can achieve a limited supercruise of Mach 1.2 for 150 miles.[225] The F135 is the second (radar) stealthy afterburning jet engine and, like the Pratt & Whitney F119 from which it was derived, has suffered from pressure pulsations in the afterburner at low altitude and high speed or "screech" during development.[226] Turbine bearing health will be monitored with thermoelectric-powered sensors.[227]

The F-35 has a maximum speed of over Mach 1.6. With a maximum takeoff weight of 60,000 lb (27,000 kg),[N 2][229] the Lightning II is considerably heavier than the lightweight fighters it replaces. In empty and maximum gross weights, it more closely resembles the single-seat, single-engine Republic F-105 Thunderchief, which was the largest single-engine fighter of the Vietnam war era. The F-35's modern engine delivers over 60 percent more thrust in an aircraft of the same weight so that in thrust to weight and wing loading it is much closer to a comparably equipped F-16.[N 3]

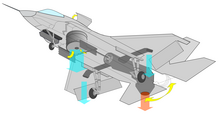

The STOVL F-35B is outfitted with the Rolls-Royce LiftSystem, designed by Lockheed Martin and developed by Rolls-Royce. This system more resembles the Russian Yak-141 and German VJ 101D/E than the preceding STOVL Harrier Jump Jet and the Rolls-Royce Pegasus engine.[231][232][233] The Lift System is composed of a lift fan, drive shaft, two roll posts and a "Three Bearing Swivel Module" (3BSM).[234] The 3BSM is a thrust vectoring nozzle which allows the main engine exhaust to be deflected downward at the tail of the aircraft. The lift fan is near the front of the aircraft and provides a counterbalancing thrust using two counter-rotating blisks.[235] It is powered by the engine's low-pressure (LP) turbine via a drive shaft and gearbox. Roll control during slow flight is achieved by diverting unheated engine bypass air through wing-mounted thrust nozzles called Roll Posts.[236][237]

F136 funding came at the expense of other parts of the program, impacting on unit costs.[238] The F136 team has claimed that their engine has a greater temperature margin which may prove critical for VTOL operations in hot, high altitude conditions.[239] Pratt & Whitney has tested higher thrust versions of the F135, partly in response to GE's claims that the F136 is capable of producing more thrust than the 43,000 lbf (190 kN) of early F135s. The F135 has demonstrated a maximum thrust of over 50,000 lbf (220 kN) during testing;[240] making it the most powerful engine ever installed in a fighter aircraft as of 2010.[241]

Armament

The F-35 features two internal weapons bays, and external hardpoints for mounting up to four underwing pylons and two near wingtip pylons. The two outer hardpoints can carry pylons for the AIM-9X Sidewinder and AIM-132 ASRAAM short-range air-to-air missiles (AAM) only.[242] The other pylons can carry the AIM-120 AMRAAM BVR AAM, Storm Shadow cruise missile, AGM-158 Joint Air to Surface Stand-off Missile (JASSM) cruise missile, and guided bombs. The external pylons can carry missiles, bombs, and fuel tanks at the expense of reduced stealth.[243] An air-to-air load of eight AIM-120s and two AIM-9s is possible using internal and external weapons stations; a configuration of six 2,000 lb (910 kg) bombs, two AIM-120s and two AIM-9s can also be arranged.[244][245]

There are a total of four weapons stations between the two internal bays. Two of these can carry air-to-ground bombs up to 2,000 lb (910 kg) in A and C models, or two bombs up to 1,000 lb (450 kg) in the B model; the other two stations are for smaller weapons such as air-to-air missiles.[244][246] The weapon bays can carry AIM-120 AMRAAM, AIM-132 ASRAAM, the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM), the Joint Stand off Weapon (JSOW), Brimstone anti-armor missiles, and Cluster Munitions (WCMD).[244] The F-35A includes a GAU-22/A, a four-barrel version of the GAU-12 Equalizer 25 mm cannon.[247] The cannon is mounted internally with 182 rounds for the F-35A or in an external pod with 220 rounds for the F-35B and F-35C;[248][249] the gun pod has stealth features. The Terma A/S multi-mission pod (MMP) could be used for different equipment and purposes, such as electronic warfare, reconnaissance, or rear-facing tactical radar.[250][251]

Lockheed Martin states that the weapons load can be configured as all-air-to-ground or all-air-to-air, and has suggested that a Block 5 version will carry three weapons per bay instead of two, replacing the heavy bomb with two smaller weapons such as AIM-120 AMRAAM air-to-air missiles.[151] Upgrades are to allow each weapons bay to carry four GBU-39 Small Diameter Bombs (SDB) for A and C models, or three in F-35B.[252] Another option is four GBU-53/B Small Diameter Bomb IIs in each bay on all F-35 variants.[253] One F-35 has been outfitted with four SDB II bombs and an AMRAAM missile to test adequate bay door clearance.[254] The MBDA Meteor air-to-air missile may be adapted for the F-35, a modified Meteor with smaller tailfins for the F-35 was revealed in September 2010; plans call for the carriage of four Meteors internally.[255] The United Kingdom planned to use up to four AIM-132 ASRAAM missiles internally, later plans call for the carriage of two internal and two external ASRAAMs.[256] The external ASRAAMs are planned to be carried on "stealthy" pylons; the missile allows attacks to slightly beyond visual range without employing radar.[242][257]

Norway and Australia are funding an adaption of the Naval Strike Missile (NSM) for the F-35. Under the designation Joint Strike Missile (JSM), it is to be the only cruise missile to fit the F-35's internal bays; according to studies two JSMs can be carried internally with an additional four externally.[258] The F-35 is expected to take on the Wild Weasel mission, though there are no planned anti-radiation missiles for internal carriage.[259] The B61 nuclear bomb was initially scheduled for deployment in 2017;[260] as of 2012 it is expected to be in the early 2020s.[261]

According to reports in 2002, Solid state lasers were being developed as optional weapons for the F-35.[262][263][264] The F-35 is also one of the target platforms for the High Speed Strike Weapon, assuming that hypersonic missile is successful.[265]

Stealth and signatures

The F-35 has been designed to have a low radar cross section primarily due to the shape of the aircraft and the use of stealthy materials in its construction, including fiber-mat.[201] Unlike the previous generation of fighters, the F-35 was designed for very-low-observable characteristics.[266] Besides radar stealth measures, the F-35 incorporates infrared and visual signature reduction measures.[267][268]

The Fighter Teen Series (F-15, F-16, F/A-18) carried large external fuel tanks, but in order to avoid negating its stealth characteristics the F-35 must fly most missions without them. Unlike the F-16 and F/A-18, the F-35 lacks leading edge extensions and instead uses stealth-friendly chines for vortex lift in the same fashion as the SR-71 Blackbird.[250] The small bumps just forward of the engine air intakes form part of the diverterless supersonic inlet (DSI) which is a simpler, lighter means to ensure high-quality airflow to the engine over a wide range of conditions. These inlets also crucially improve the aircraft's very-low-observable characteristics.[269]

In spite of being smaller than the F-22, the F-35 has a larger radar cross section; said to be roughly equal to a metal golf ball rather than the F-22's metal marble.[270] The F-22 was designed to be difficult to detect by all types of radars and from all directions.[271] The F-35 on the other hand manifests its lowest radar signature from the frontal aspect due to design compromises. Its surfaces are shaped to best defeat radars operating in the X and upper S band, which are typically found on fighters, surface-to-air missiles and their tracking radars; the F-35 would be easier to detect using other radar frequencies.[271] Because the aircraft's shape is important to the radar cross section (RCS), special care must be taken to maintain the "outer mold line" during production.[272] Ground crews require Repair Verification Radar (RVR) test sets to verify the RCS after performing repairs, which is not a concern upon non-stealth aircraft.[273][274]

In late 2008 the air force revealed that the F-35 would be about twice as loud at takeoff as the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle and up to four times as loud during landing.[275] As a result, residents near Luke Air Force Base, Arizona and Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, possible home bases for the jet, requested that the air force conduct environmental impact studies concerning the F-35's noise levels.[275] The city of Valparaiso, Florida, adjacent to Eglin AFB, threatened in February 2009 to sue over the impending arrival of the F-35s, but this lawsuit was settled in March 2010.[276][277][278] It was reported in March 2009 that testing by Lockheed Martin and the Royal Australian Air Force revealed that the F-35 was not as loud as first reported, being "only about as noisy as an F-16 fitted with a Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-200 engine" and "quieter than the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor and the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet."[279] According to an acoustics study done by Lockheed Martin and the U.S. Air Force, the noise levels of the F-35 are found to be comparable to the F-22 Raptor and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet.[280] A USAF environmental impact study found that replacing F-16s with F-35s at Tucson International Airport would subject more than 21 times as many residents to extreme noise levels.[281]

Cockpit

The F-35 features a full-panel-width glass cockpit touch screen[282] "panoramic cockpit display" (PCD), with dimensions of 20 by 8 inches (50 by 20 centimeters).[283] A cockpit speech-recognition system (DVI) provided by Adacel has been adopted on the F-35, added to the pilot's ability to interact with the aircraft and operate its systems. The F-35 will be the first operational U.S. fixed-wing aircraft to employ this DVI system, although similar systems have been used on the AV-8B Harrier II and trialled in previous aircraft, such as the F-16 VISTA.[284]

A helmet-mounted display system (HMDS) will be fitted to all models of the F-35.[285] While some fighters have offered HMDS along with a head up display (HUD), this will be the first time in several decades that a front line fighter has been designed without a HUD.[286] The F-35 is equipped with a right-hand HOTAS side stick controller. The Martin-Baker US16E ejection seat is used in all F-35 variants.[287] The US16E seat design balances major performance requirements, including safe-terrain-clearance limits, pilot-load limits, and pilot size; it uses a twin-catapult system housed in side rails.[288] The F-35 employs an oxygen system derived from the F-22's own system, which has been involved in multiple hypoxia incidents on that aircraft; unlike the F-22, the flight profile of the F-35 is similar to other fighters that routinely use such systems.[289][290]

Sensors and avionics

The F-35's sensor and communications suite is said to possess situational awareness, command-and-control and network-centric warfare capabilities.[5][291] The main sensor on board is the AN/APG-81 AESA-radar, designed by Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems.[292] It is augmented by the nose-mounted Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS);[293] designed by Lockheed Martin, it provides the capabilities of the externally mounted Sniper XR pod while making a reduced radar presence.[294][295] The AN/ASQ-239 (Barracuda) system is an improved version of the AN/ALR-94 EW suite on the F-22. The AN/ASQ-239 provides sensor fusion of RF and IR tracking functions, basic radar warning, multispectral countermeasures for self-defense against threat missiles, situational awareness and electronic surveillance; employing 10 radio frequency antennae embedded into the edges of the wing and tail.[296][297]

Six additional passive infrared sensors are distributed over the aircraft as part of Northrop Grumman's AN/AAQ-37 distributed aperture system (DAS),[30] which acts as a missile warning system, reports missile launch locations, detects and tracks approaching aircraft spherically around the F-35, and replaces traditional night vision goggles for night operations and navigation. All DAS functions are performed simultaneously, in every direction, at all times. The F-35's Electronic Warfare systems are designed by BAE Systems and include Northrop Grumman components.[298] Some functions such as the Electro-Optical Targeting System and the Electronic Warfare system are not usually integrated on fighters.[299]

The communications, navigation and identification (CNI) suite is designed by Northrop Grumman and includes the Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL), as one of a half dozen different physical links.[300] The F-35 will be the first jet fighter with sensor fusion that combines radio frequency and IR tracking for continuous target detection and identification in all directions which is shared via MADL to other platforms without compromising low observability.[228] The non-stealthy Link 16 is also included for communication with legacy systems.[301] The F-35 has been designed with synergy between sensors as a specific requirement, the aircraft's "senses" being expected to provide a more cohesive picture of the reality around it and be available for use in any possible way and combination with one another; for example, the AN/APG-81 multi-mode radar also acts as a part of the electronic warfare system.[302]

Unlike previous aircraft, such as the F-22, much of the new software for the F-35 is written in C and C++, because of programer availability. Much Ada83 code is reused from the F-22.[303] The Integrity DO-178B real-time operating system (RTOS) from Green Hills Software runs on COTS Freescale PowerPC processors.[304] The final Block 3 software for the F-35 is planned to have 8.6 million lines of software code.[305] The scale of the program has led to a software crisis as officials continue to discover that additional software needs to be written.[306] General Norton Schwartz has said that the software is the biggest factor that might delay the USAF's initial operational capability.[307] Michael Gilmore, Director of Operational Test & Evaluation, has written that, "the F-35 mission systems software development and test is tending towards familiar historical patterns of extended development, discovery in flight test, and deferrals to later increments."[308]

The F-35's electronic warfare systems are intended to detect hostile aircraft, then scan them with the electro-optical system to allow the pilot to engage or evade the opponent before the F-35 is detected.[302] The CATbird avionics testbed for the F-35 program has proved capable of detecting and jamming radars, including those used on the F-22.[309] The F-35 was previously considered a platform for the Next Generation Jammer; however attention has shifted to the use of unmanned aircraft as an alternate platform.[310]

Several "critical electronic subsystems" of the F-35 depend on Xilinx FPGAs.[311] These COTS components allow for refreshes in supplies from the commercial market and to field upgrade the entire fleet via software for the aircraft's Software-defined radio systems.[312]

Helmet-mounted display system

The F-35 does not need to be physically pointing at its target for weapons to be successful.[244][313] Sensors can track and target a nearby aircraft from any orientation, provide the information to the pilot through his helmet (and therefore visible no matter which way the pilot is looking), and provide the seeker-head of a missile with sufficient information. Recent missile types provide a much greater ability to pursue a target regardless of the launch orientation, called "High Off-Boresight" capability. Sensors use combined radio frequency and infra red (SAIRST) to continually track nearby aircraft while the pilot's helmet-mounted display system (HMDS) displays and selects targets; the helmet system replaces the display-suite-mounted head-up display used in earlier fighters.[314]

The F-35's systems provide the edge in the "observe, orient, decide, and act" OODA loop; stealth and advanced sensors aid in observation (while being difficult to observe), automated target tracking helps in orientation, sensor fusion simplifies decision making, and the aircraft's controls allow the pilot to keep their focus on the targets, rather than the controls of their aircraft.[315][N 4]

Problems with the Vision Systems International helmet-mounted display led Lockheed Martin to issue a draft specification for alternative proposals in early 2011, to be based around the Anvis-9 night vision goggles.[316] BAE Systems was selected to provide the alternative system in late 2011.[317] If successful, the BAE Systems alternative helmet is to incorporate all the features of the VSI system.[318] Adopting the alternative helmet would require a cockpit redesign.[319] In 2011, Lockheed granted VSI a contract to fix the vibration, jitter, night-vision and sensor display problems in their helmet-mounted display.[320] A speculated potential improvement is the replacement of Intevac’s ISIE-10 day/night camera with the newer ISIE-11 model.[321] In October 2012, Lockheed stated that progress had been made in resolving the technical issues of the helmet-mounted display, and cited positive reports from night flying tests; it had been questioned whether the helmet system allows pilots enough visibility at night to carry out precision tasks.[322] In 2013, in spite of continuing problems with the helmet display, the F-35B model completed 19 nighttime vertical landings onboard the USS Wasp at sea.[323]

Maintenance

The program's maintenance concept is for any F-35 to be maintained in any F-35 maintenance facility and that all F-35 parts in all bases will be globally tracked and shared as needed.[324] The commonality between the different variants has allowed the USMC to create their first aircraft maintenance Field Training Detachment to directly apply the lessons of the USAF to their F-35 maintenance operations.[325] The aircraft has been designed for ease of maintenance, with 95% of all field replaceable parts "one deep" where nothing else has to be removed to get to the part in question. For instance the ejection seat can be replaced without removing the canopy, the use of low-maintenance electro-hydrostatic actuators instead of hydraulic systems and an all-composite skin without the fragile coatings found on earlier stealth aircraft.[326]

The F-35 has received good reviews from pilots and maintainers, suggesting it is performing better than its predecessors did at a similar stage of development. The stealth type has proved relatively stable from a maintenance standpoint. Part of the improvement is attributed to better maintenance training, as F-35 maintainers have received far more extensive instruction at this early stage of the program than on the F-22 Raptor. The F-35's stealth coatings are much easier to work with than those used on the Raptor. Cure times for coating repairs are lower and many of the fasteners and access panels are not coated, further reducing the workload for maintenance crews. Some of the F-35's radar-absorbent materials are baked into the jet's composite skin, which means its stealthy signature is not easily degraded.[327] It is still harder to maintain (due to its stealth) than fourth-generation aircraft.[328]

Operational history

Testing

The first F-35A (designated AA-1) was rolled out in Fort Worth, Texas, on 19 February 2006. In September 2006, the first engine run of the F135 in an airframe took place.[329] On 15 December 2006, the F-35A completed its maiden flight.[330] A modified Boeing 737–300, the Lockheed CATBird has been used as an avionics test-bed for the F-35 program, including a duplication of the cockpit.[151]

The first F-35B (designated BF-1) made its maiden flight on 11 June 2008, piloted by BAE Systems' test pilot Graham Tomlinson. Flight testing of the variant's STOVL propulsion system began on 7 January 2010.[331] The F-35B's first hover was on 17 March 2010, followed by its first vertical landing the next day.[332] During a test flight on 10 June 2010, the F-35B became the second STOVL aircraft to achieve supersonic speeds[333] after the X-35B.[334] In January 2011, Lockheed Martin reported that a solution had been found for the cracking of an aluminum bulkhead during ground testing of the F-35B.[335] However, in 2013, the F-35B had suffered another incident involving bulkhead cracking.[336]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| F-35B tests on USS Wasp in 2011 | |