Names of Germany: Difference between revisions

drop pov-based deletions |

|||

| Line 158: | Line 158: | ||

;Other forms: |

;Other forms: |

||

* |

|||

*[[Arabic languages|Arabic]]: [[Ajan|عجم (ajan)]] ''mute''. |

|||

*[[Hebrew language|Ancient Hebrew]]: פְּלִשְׁתִּים (Plištim) [[Philistines]], probably from [[Nubians]] or [[People of Ethiopia|Ethiopians]] for ''marauders'', ''travelers'' or ''nomadic strangers''. Philistines were the kinsman of tribes, which after reaching [[Scandza]] became "Nordic" or "Germanic", but those who stayed in Middle East looted the islands and shores of the eastern Mediterranean Sea (present among modern Albanians, Bosniaks…). |

|||

*[[Ancient Greek dialects|Ancient Greek]]: ''Ὑπερβόρε(ι)οι'' (Hyperboreoi) and ''Ἀνδροφάγοι'' (Androfagoi) for ''man-eaters'' (later Germans) living "behind the cold winds" north of [[Scythia]] in [[Scandza]], ''Εσπερία'' (Esperia) for Western Europe, then still free from Germanic tribes (Σκυθική, Skythikē for rest of Europe and Central Asia). The diffuse term ''Hyperborea'' was often applied to all territories north of Greece and ''Esperia'' to all territories west of Greece. Trade routes of the Ionian fleet by means of [[Danube]] included [[Pannonia]] and [[Boii|Boio-Arya (Bavaria)]], variations of Greek alphabet and the Greek language (along Celtic, Venetic, Slavic, Etrurian, Raetic and Iranian dialects) were also used among the [[Veneti|Venetic]] and some [[Celtic peoples]] [[La Tène culture|native to later Germany]], e.g. in [[Goseck circle|Gąsiek (Goseck)]], [[Nebra sky disk|Nebra]], [[History of Speyer|Spira (Speyer)]], [[Kyffhäuser Monument|Spira/Spier (Querfurt-Kyffhäuser-Esperstedt)]], [[Xanten|Iakšantia (Xanten)]], [[Aschaffenburg|Ašaperk (Aschaffenburg)]], [[Glauberg|Gławperk (Glauberg)]], [[Aschersleben|Ašarya (Aschersleben)]], [[Vineta|Vineta/Wełtawa]], [[Lübeck|Ljubice/Bukowiec (Lübeck)]], [[Bremen|Brzemię (Bremen)]], [[Havelberg|Hobolin (Havelberg)]], [[Oldenburg|Starigard (Oldenburg)]], [[Pirna]]… |

|||

*[[Medieval Greek]]: ''Frángoi'', ''frangikós'' (for ''Germans'', ''German'') – after the [[Franks]]. |

*[[Medieval Greek]]: ''Frángoi'', ''frangikós'' (for ''Germans'', ''German'') – after the [[Franks]]. |

||

*Medieval [[Hebrew language]]: אַשְׁכְּנַז (Ashkenaz) – from biblical [[Ashkenaz]] (אַשְׁכְּנַז) was the son of [[Japheth]] and grandson of [[Noah]]. Ashkenaz is thought to be the ancestor of the Germans. |

*Medieval [[Hebrew language]]: אַשְׁכְּנַז (Ashkenaz) – from biblical [[Ashkenaz]] (אַשְׁכְּנַז) was the son of [[Japheth]] and grandson of [[Noah]]. Ashkenaz is thought to be the ancestor of the Germans. |

||

*[[Medieval Latin]]: ''Teutonia'', ''regnum Teutonicum'' – after the [[Teutons]]. |

*[[Medieval Latin]]: ''Teutonia'', ''regnum Teutonicum'' – after the [[Teutons]]. |

||

*[[German language]]: ''Teutonisch Land'', ''Teutschland'' used in many areas until the 19th century (see [[Walhalla memorial|Walhalla]] opening song), ''Deutschland'' - the current official designation. |

*[[German language]]: ''Teutonisch Land'', ''Teutschland'' used in many areas until the 19th century (see [[Walhalla memorial|Walhalla]] opening song), ''Deutschland'' - the current official designation. |

||

*[[Tahitian language]]: ''Purutia'' (also ''Heremani'', see above) – a corruption of ''Prusse'', the French name for the German Kingdom of [[Prussia]].<!-- Tahitian WP uses "Heremani". --> |

*[[Tahitian language]]: ''Purutia'' (also ''Heremani'', see above) – a corruption of ''Prusse'', the French name for the German Kingdom of [[Prussia]].<!-- Tahitian WP uses "Heremani". --> |

||

*[[Lower Sorbian language]]: ''bawory'' or ''bawery'' (in older or dialectal use) – from the name of [[Bavaria]] |

*[[Lower Sorbian language]]: ''bawory'' or ''bawery'' (in older or dialectal use) – from the name of [[Bavaria]]. |

||

*[[Silesian language|Silesian]]: ''szwaby'' |

*[[Silesian language|Silesian]]: ''szwaby'' from [[Suebi]] or [[Swabia]], ''bambry'' used for German peasant [[Drang nach Osten|colonists]] from the area around [[Bamberg]], ''Prusacy'' from [[Prussia]], ''krzyżacy'' (a derogative form of ''krzyżowcy'' - ''crusaders'') referring to [[Teutonic Order]]. ''Rajch'' or ''Rajś'' perfectly resembling German pronunciation of ''[[German Reich|Reich]]''<ref>https://www.academia.edu/27865701/Crocodile_Skin_or_the_Fraternal_Curtain_pp_742-759_._2012._The_Antioch_Review._Vol_70_No_4_Fall</ref> . |

||

*[[Old Norse]]: ''Suðrvegr'' – literally ''south way'' ([[cf.]] [[Norway]]),<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=Norway |work=Etymonline |title=Norway |accessdate=2007-08-21}}</ref> describing Germanic tribes which invaded continental Europe. |

*[[Old Norse]]: ''Suðrvegr'' – literally ''south way'' ([[cf.]] [[Norway]]),<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=Norway |work=Etymonline |title=Norway |accessdate=2007-08-21}}</ref> describing Germanic tribes which invaded continental Europe. |

||

*[[English language|English]]: ''Krauts'' from ''[[Sauerkraut|Sauerkraut (sour cabbage)]]'' consumed regularly by Germans along |

*[[English language|English]]: ''Krauts'' from ''[[Sauerkraut|Sauerkraut (sour cabbage)]]'' consumed regularly by Germans along with [[Wurst]]. |

||

*[[Kinyarwanda]]: ''Ubudage'', [[Kirundi]]: ''Ubudagi'' – thought to derive from the greeting ''guten Tag'' used by Germans during the colonial times,<ref>Jutta Limbach, ''Ausgewanderte Wörter.'' ''Eine Auswahl der interessantesten Beiträge zur internationalen Ausschreibung „Ausgewanderte Wörter“.'' Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verl, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 123, {{ISBN|978-3-19-107891-1}}.</ref> or from ''deutsch''.<ref>John Joseph Gumperz and Dell Hathaway Hymes, ''The ethnography of communication.'' Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, N.Y. [etc.] 1972, p. 96, {{ISBN|9780030777455}}.</ref> |

*[[Kinyarwanda]]: ''Ubudage'', [[Kirundi]]: ''Ubudagi'' – thought to derive from the greeting ''guten Tag'' used by Germans during the colonial times,<ref>Jutta Limbach, ''Ausgewanderte Wörter.'' ''Eine Auswahl der interessantesten Beiträge zur internationalen Ausschreibung „Ausgewanderte Wörter“.'' Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verl, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 123, {{ISBN|978-3-19-107891-1}}.</ref> or from ''deutsch''.<ref>John Joseph Gumperz and Dell Hathaway Hymes, ''The ethnography of communication.'' Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, N.Y. [etc.] 1972, p. 96, {{ISBN|9780030777455}}.</ref> |

||

*[[Navajo language|Navajo]]: {{spell-nv|''Béésh Bich’ahii Bikéyah''}} ("Metal Cap-wearer Land"), in reference to ''[[Stahlhelm]]''-wearing German soldiers. |

*[[Navajo language|Navajo]]: {{spell-nv|''Béésh Bich’ahii Bikéyah''}} ("Metal Cap-wearer Land"), in reference to ''[[Stahlhelm]]''-wearing German soldiers. |

||

| Line 190: | Line 188: | ||

The Germanic language which ''diutisc'' most likely comes from is West Frankish, a language which died out a long time ago and which there is hardly any written evidence for today. This was the Germanic dialect used in the early [[Middle Ages]], spoken by the [[Franks]] in [[Western Francia]], i.e. in the region which is now northern [[France]]. The word is only known from the Latin form ''[[theodiscus]]''. Until the 8th century the Franks called their language ''frengisk''; however, when the Franks moved their political and cultural centre to the area where France now is, the term ''frengisk'' became ambiguous, as in the West Francian territory some Franks spoke Latin, some [[vulgar Latin]] and some ''theodisc''. For this reason a new word was needed to help differentiate between them. Thus the word ''theodisc'' evolved from the Germanic word ''theoda'' (the people) with the Latin [[suffix]] ''-iscus'', to mean "belonging to the people", i.e. the people's language. |

The Germanic language which ''diutisc'' most likely comes from is West Frankish, a language which died out a long time ago and which there is hardly any written evidence for today. This was the Germanic dialect used in the early [[Middle Ages]], spoken by the [[Franks]] in [[Western Francia]], i.e. in the region which is now northern [[France]]. The word is only known from the Latin form ''[[theodiscus]]''. Until the 8th century the Franks called their language ''frengisk''; however, when the Franks moved their political and cultural centre to the area where France now is, the term ''frengisk'' became ambiguous, as in the West Francian territory some Franks spoke Latin, some [[vulgar Latin]] and some ''theodisc''. For this reason a new word was needed to help differentiate between them. Thus the word ''theodisc'' evolved from the Germanic word ''theoda'' (the people) with the Latin [[suffix]] ''-iscus'', to mean "belonging to the people", i.e. the people's language. |

||

In [[Eastern Francia]], roughly the area where Germany now is, it seems that the new word was taken on by the people only slowly, over the centuries: in central Eastern Francia the word ''frengisk'' was used for a lot longer, as there was no need for people to distinguish themselves from the distant Franks. The word ''diutsch'' and other variants were only used by people to describe themselves, at first as an alternative term, from about the 10th century. It was used, for example, in the [[Sachsenspiegel]], a legal code, written in Middle Low German in about 1220: '' Iewelk |

In [[Eastern Francia]], roughly the area where Germany now is, it seems that the new word was taken on by the people only slowly, over the centuries: in central Eastern Francia the word ''frengisk'' was used for a lot longer, as there was no need for people to distinguish themselves from the distant Franks. The word ''diutsch'' and other variants were only used by people to describe themselves, at first as an alternative term, from about the 10th century. It was used, for example, in the [[Sachsenspiegel]], a legal code, written in Middle Low German in about 1220: '' Iewelk düdesch'' ''lant hevet sinen palenzgreven: sassen, beieren, vranken unde svaven'' |

||

(Every German land has its [[Graf]]: Saxony, Bavaria, Franken and Swabia). |

(Every German land has its [[Graf]]: Saxony, Bavaria, Franken and Swabia). |

||

| Line 197: | Line 195: | ||

==Names from Germania== |

==Names from Germania== |

||

[[File:Gaius Cornelius Tacitus.jpg|thumb|left|200px|upright|[[Gaius Cornelius Tacitus]]]] |

[[File:Gaius Cornelius Tacitus.jpg|thumb|left|200px|upright|[[Gaius Cornelius Tacitus]]]] |

||

The name ''Germany'' and the other similar-sounding names above are all derived from the [[Latin]] ''[[Germania]]'', of the 3rd century BC, a word simply describing ''fertile land'' behind the limes. It was likely the [[Gauls]] who first called the people who crossed east of the Rhine ''Germani'' (which the Romans adopted) as the original Germanic tribes did not refer to themselves as ''Germanus'' (singular) or ''Germani'' (plural).<ref>{{cite book |last= Wolfram |first=Herwig |title= The Roman Empire and its Germanic Peoples |publisher= University of California Press |pages=4–5 |year=1997 |isbn= 0-520-08511-6}}</ref> |

The name ''Germany'' and the other similar-sounding names above are all derived from the [[Latin]] ''[[Germania]]'', of the 3rd century BC, a word simply describing ''fertile land'' behind the limes. It was likely the [[Gauls]] who first called the people who crossed east of the Rhine ''Germani'' (which the Romans adopted) as the original Germanic tribes did not refer to themselves as ''Germanus'' (singular) or ''Germani'' (plural).<ref>{{cite book |last= Wolfram |first=Herwig |title= The Roman Empire and its Germanic Peoples |publisher= University of California Press |pages=4–5 |year=1997 |isbn= 0-520-08511-6}}</ref> |

||

[[Julius Caesar]] was the first to use ''Germanus'' in writing when describing tribes in north-eastern [[Gaul]] in his ''[[Commentarii de Bello Gallico]]'': he records that four northern [[Belgae|Belgic]] tribes, namely the [[Condrusi]], [[Eburones]], [[Caeraesi]] and [[Paemani]], were collectively known as [[Germani]]. In AD 98, [[Gaius Cornelius Tacitus|Tacitus]] wrote ''[[Germania (book)|Germania]]'' (the Latin title was actually: ''De Origine et situ Germanorum''), an ethnographic work on the diverse set of [[Germanic peoples|Germanic tribe]]s outside the [[Roman Empire]]. Unlike Caesar, Tacitus claims that the name ''Germani'' was first applied to the [[Tungri]] tribe. The name ''Tungri'' is thought to be the [[endonym]] corresponding to the [[exonym]] ''Eburones''. |

[[Julius Caesar]] was the first to use ''Germanus'' in writing when describing tribes in north-eastern [[Gaul]] in his ''[[Commentarii de Bello Gallico]]'': he records that four northern [[Belgae|Belgic]] tribes, namely the [[Condrusi]], [[Eburones]], [[Caeraesi]] and [[Paemani]], were collectively known as [[Germani]]. In AD 98, [[Gaius Cornelius Tacitus|Tacitus]] wrote ''[[Germania (book)|Germania]]'' (the Latin title was actually: ''De Origine et situ Germanorum''), an ethnographic work on the diverse set of [[Germanic peoples|Germanic tribe]]s outside the [[Roman Empire]]. Unlike Caesar, Tacitus claims that the name ''Germani'' was first applied to the [[Tungri]] tribe. The name ''Tungri'' is thought to be the [[endonym]] corresponding to the [[exonym]] ''Eburones''. |

||

| Line 210: | Line 208: | ||

The name ''Allemagne'' and the other similar-sounding names above are derived from the southern [[Germanic tribe|Germanic]] [[Alemanni]], a [[Suebi]]c tribe or confederation in today's [[Alsace]], parts of [[Baden-Württemberg]] and [[Switzerland]]. |

The name ''Allemagne'' and the other similar-sounding names above are derived from the southern [[Germanic tribe|Germanic]] [[Alemanni]], a [[Suebi]]c tribe or confederation in today's [[Alsace]], parts of [[Baden-Württemberg]] and [[Switzerland]]. |

||

The name may come from Proto-Germanic *''Alamanniz'' which may have one of two meanings, depending on the derivation of "Al-". If "Al-" means "all", then the name means "all men" (being able and having the right to fight), suggesting that the tribe was a confederation of different groups. If "Al-" comes from the first element in [[Latin]] ''alius'', "the other", then it is related to English "else" or "alien" and Alemanni means "foreign men". |

The name may come from Proto-Germanic *''Alamanniz'' which may have one of two meanings, depending on the derivation of "Al-". If "Al-" means "all", then the name means "all men" (being able and having the right to fight), suggesting that the tribe was a confederation of different groups. If "Al-" comes from the first element in [[Latin]] ''alius'', "the other", then it is related to English "else" or "alien" and Alemanni means "foreign men". |

||

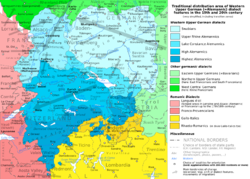

[[File:Alemannic-Dialects-Map-English.png|thumb|right|250px|The areas where [[Alemannic German]] is spoken]] |

[[File:Alemannic-Dialects-Map-English.png|thumb|right|250px|The areas where [[Alemannic German]] is spoken]] |

||

| Line 224: | Line 222: | ||

==Names from Saxon== |

==Names from Saxon== |

||

The names ''Saksamaa'' and ''Saksa'' are derived from the name of the Germanic tribe of the [[Saxons]]. The word "Saxon", Proto-Germanic *''sakhsan'', is believed (a) to be derived from the word [[seax]], meaning a variety of single-edged [[knife|knives]]: a Saxon was perhaps literally a swordsman, or (b) to be derived from the word "axe", the region axed between the valleys of the [[Elbe]] and [[Weser]]. |

The names ''Saksamaa'' and ''Saksa'' are derived from the name of the Germanic tribe of the [[Saxons]]. The word "Saxon", Proto-Germanic *''sakhsan'', is believed (a) to be derived from the word [[seax]], meaning a variety of single-edged [[knife|knives]]: a Saxon was perhaps literally a swordsman, or (b) to be derived from the word "axe", the region axed between the valleys of the [[Elbe]] and [[Weser]]. |

||

In [[Finnish language|Finnish]] and [[Estonian language|Estonian]] the words that historically applied to ancient Saxons changed their meaning over the centuries to denote the whole country of Germany and the Germans. In some [[Celtic languages]] the word for the English nationality is derived from Saxon, e.g., the Scottish term ''[[Sassenach]]'', the Breton terms ''Saoz, Saozon'' and the [[Welsh language|Welsh]] terms ''Sais, Saeson''. "Saxon" also led to the "-sex" ending in [[Wessex]], [[Essex]], [[Sussex]], [[Middlesex]], etc., and of course to "[[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]]". |

In [[Finnish language|Finnish]] and [[Estonian language|Estonian]] the words that historically applied to ancient Saxons changed their meaning over the centuries to denote the whole country of Germany and the Germans. In some [[Celtic languages]] the word for the English nationality is derived from Saxon, e.g., the Scottish term ''[[Sassenach]]'', the Breton terms ''Saoz, Saozon'' and the [[Welsh language|Welsh]] terms ''Sais, Saeson''. "Saxon" also led to the "-sex" ending in [[Wessex]], [[Essex]], [[Sussex]], [[Middlesex]], etc., and of course to "[[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]]". |

||

==Names from Nemets== |

==Names from Nemets== |

||

The Slavic [[exonym]] ''nemets'', ''nemtsy'' derives from [[Proto-Slavic]] ''němьcь'', pl. ''němьci'', 'the mutes', 'not able (to speak)' (from adjective ''němъ'' 'mute' and suffix -''ьcь'').<ref name="Vasmer">{{Cite book|last=Vasmer|first=Max|title=Etymological dictionary of the Russian language|volume=Volume III|publisher=Progress|year=1986|location=Moscow|language=Russian|page=62|url=http://etymolog.ruslang.ru/vasmer.php?id=62&vol=3 }}</ref> It literally means ''a mute'' and can be also associated with similar sounding ''not able'', ''without power'', but came to signify ''those who can't speak (like us); foreigners''. The Slavic [[exonym and endonym|autonym]] (Proto-Slavic ''*Slověninъ'') likely derives from ''slovo'', meaning ''word |

The Slavic [[exonym]] ''nemets'', ''nemtsy'' derives from [[Proto-Slavic]] ''němьcь'', pl. ''němьci'', 'the mutes', 'not able (to speak)' (from adjective ''němъ'' 'mute' and suffix -''ьcь'').<ref name="Vasmer">{{Cite book|last=Vasmer|first=Max|title=Etymological dictionary of the Russian language|volume=Volume III|publisher=Progress|year=1986|location=Moscow|language=Russian|page=62|url=http://etymolog.ruslang.ru/vasmer.php?id=62&vol=3 }}</ref> It literally means ''a mute'' and can be also associated with similar sounding ''not able'', ''without power'', but came to signify ''those who can't speak (like us); foreigners''. The Slavic [[exonym and endonym|autonym]] (Proto-Slavic ''*Slověninъ'') likely derives from ''slovo'', meaning ''word''. According to a theory, early Slavs would call themselves the ''speaking people'' or the ''keepers of the words'', as opposed to their Germanic neighbors, the ''mutes'' (a similar idea lies behind Greek ''barbaros'', [[barbarian]]) and Arab [[Ajan|عجم (ajan)]] ''mute''. At first, ''němьci'' may have been used for any non-Slav foreigners, later narrowed to just Germans. The plural form is used for the Germans instead of any specific country name, e.g. ''Niemcy'' in Polish and ''Ńymcy'' in Silesian dialect. In other languages, the country's name derives from the adjective ''němьcьska (zemja)'' meaning 'German (land)' (f.i. Czech ''Německo''). Belarusian {{lang|be|Нямеччына}} (''Nyamyecchyna''), Bulgarian {{lang|bg|Немция}} (''Nemtsiya'') and Ukrainian {{lang|uk|Німеччина}} (''Nimecchyna'') are also from ''němьcь'' but with the addition of the suffix -''ina''. |

||

According to another theory,<ref name="Indo-European">[https://books.google.com/books?id=3QIaAAAAIAAJ&q=nemeti+etymology&dq=nemeti+etymology&ei=JxttSZPaOIjWNsy5sMwJ&pgis=1 The Journal of Indo-European studies]</ref><ref name="PolishEtym">[http://grzegorj.w.interia.pl/lingwpl/przen.html (in Polish) Etymology of the Polish-language word for Germany]</ref> ''Nemtsy'' may derive from the Rhine-based, Germanic tribe of [[Nemetes]] mentioned by [[Julius Caesar|Caesar]]<ref>C. Iulius Caesar, "Commentariorum Libri VII De Bello Gallico", VI, 25. [http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/caesar/gall6.shtml#25 Latin text]</ref> and [[Tacitus]].<ref>P. CORNELIVS TACITVS ANNALES, 12, 27. [http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/tacitus/tac.ann12.shtml#27 Latin text]</ref> This etymology is dubious for phonological ''nemetes'' could not become Slavic ''němьcь''.<ref name="Vasmer"/> |

According to another theory,<ref name="Indo-European">[https://books.google.com/books?id=3QIaAAAAIAAJ&q=nemeti+etymology&dq=nemeti+etymology&ei=JxttSZPaOIjWNsy5sMwJ&pgis=1 The Journal of Indo-European studies]</ref><ref name="PolishEtym">[http://grzegorj.w.interia.pl/lingwpl/przen.html (in Polish) Etymology of the Polish-language word for Germany]</ref> ''Nemtsy'' may derive from the Rhine-based, Germanic tribe of [[Nemetes]] mentioned by [[Julius Caesar|Caesar]]<ref>C. Iulius Caesar, "Commentariorum Libri VII De Bello Gallico", VI, 25. [http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/caesar/gall6.shtml#25 Latin text]</ref> and [[Tacitus]].<ref>P. CORNELIVS TACITVS ANNALES, 12, 27. [http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/tacitus/tac.ann12.shtml#27 Latin text]</ref> This etymology is dubious for phonological ''nemetes'' could not become Slavic ''němьcь''.<ref name="Vasmer"/> |

||

Recent research connects the ''[[Nemetes]]'' with [[Veneti|Veneto]]-[[Celts|Celtic]] communities living in tents (''namety''), ''[[Chatti]]'' living in huts (''chaty''), ''[[Triboci]]'' using tripods (''třybocy''), ''[[Cherusci]]'' using lots of dry wood (''chruści'') e.t.c. The Germanic tribes didn't also build [[Kurgan|kurgans]], which is the domain of [[Saka|Śaka]] and [[Sarmatians]] and can be found in [[Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave|Spyrgowa]] next to the [[Golden Hat of Schifferstadt]] of [[History of Speyer|Spira (Noviomagus Nemetum)]] one of the crests of the [[Pernus coat of arms|Spyra dynasty]], represented in [[Etruria]] by [[Spero]] and [[Peruzzi]] and in [[Raetia]] by [[Johanna Spyri|Spyri]]. |

|||

The term ''Germania'' used by Romans means just ''fertile land'' and has no ethnic conotation. The customs and traditions of the Germans clearly show their ethnic heritage from [[Haplogroup I-M253|haplogroups I1 and I2]] of [[Scandza]], which they entered following as parasite cannibals after the first Indo-European agriculturalists ca. 5000 BC. On their way north they left traces of horror, e.g.: [[Talheim Death Pit]], [[Herxheim (archaeological site)]]. Two millennia ago those tribes started a massive comeback culminating in [[colonialism]], permanent wars and [[Extermination camp|German extermination camps]]. |

|||

In [[Russian language|Russian]], the adjective for "German", немецкий (''nemetskiy'') comes from the same Slavic root while the name for the country is ''Germaniya'' (Германия). Likewise, in [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] the adjective is "немски" (''nemski'') and the country is ''Germaniya'' (Германия). |

In [[Russian language|Russian]], the adjective for "German", немецкий (''nemetskiy'') comes from the same Slavic root while the name for the country is ''Germaniya'' (Германия). Likewise, in [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] the adjective is "немски" (''nemski'') and the country is ''Germaniya'' (Германия). |

||

Over time, the Slavic exonym was borrowed by some non-Slavic languages. The Hungarian name for Germany is ''Németország'' (from the stem Német-. lit. Német Land). The popular Romanian name for German is ''neamț'', used alongside the official term, ''german'', which was borrowed from Latin. The [[Arabic language|Arabic]] name for [[Austria]] النمسا ''an-Nimsā'' was borrowed from the [[Ottoman Turkish language|Ottoman Turkish]] and [[Persian language|Persian]] word for Austria, "نمچه" – "Nemçe", from one of the [[South Slavic languages]] (in the 16–17th centuries the [[Austrian Empire]] was the biggest German-speaking country bordering on the Ottoman Empire) and like in Polish also doesn't refer to a specific country but only to the people occupying it. |

Over time, the Slavic exonym was borrowed by some non-Slavic languages. The Hungarian name for Germany is ''Németország'' (from the stem Német-. lit. Német Land). The popular Romanian name for German is ''neamț'', used alongside the official term, ''german'', which was borrowed from Latin. The [[Arabic language|Arabic]] name for [[Austria]] النمسا ''an-Nimsā'' was borrowed from the [[Ottoman Turkish language|Ottoman Turkish]] and [[Persian language|Persian]] word for Austria, "نمچه" – "Nemçe", from one of the [[South Slavic languages]] (in the 16–17th centuries the [[Austrian Empire]] was the biggest German-speaking country bordering on the Ottoman Empire) and like in Polish also doesn't refer to a specific country but only to the people occupying it. |

||

The word ''land'' is also borrowed from Slavic ''ląd'' (''ą'' being often transcribed as ''on'', ''om'', ''an'', ''am'') and originally didn't mean a country or state but a continent or big island - so ''London'' (''Lądyn'') means just a ''place of landing''. |

|||

In [[Poland]] the native [[Veneti|Venetic]]/[[Slavs|Slavic]] inhabitants of the area now called Germany, both historic peoples and their current descendants, are still called by their original names, e.g.: ''Połabianie'' for [[Polabian Slavs]], ''Serbołużyce'' for [[White Serbia]] incl. [[Lusatia]], ''Łużyce'' for [[Lusatia]] alone, where the [[Historical Slavic religion|ancient native Slavic culture]] still survives, ''Wędowie'' for [[Veneti]] and [[Wends]] (ethnically the same peoples, distinct just by time of their settelment interrupted by devastating invasions of [[Semnones]], [[Herules]], [[Vandals]]…), ''Pomorze'' for [[Pomerania]] incl. the western part called by Germans [[Mecklenburg-Vorpommern]], ''Sprewianie'' and ''Stodoranie'' for inhabitants of the [[Jaxa of Köpenick|Duchy of Kopnik]] (a Polish fief) also called ''Kopanica'' and ''Branibor''/''Broniborze'' (''the protective forests'') currently called [[Brandenburg]] (''Brenna'' for the city of Brandenburg alone), ''Wieleci'' for [[Veleti]], ''Obodrzyce'' for [[Obotrites|Obodrites]], ''Łużyczanie'' for [[Lusatians]], ''Ranowie'' for [[Rani (Slavic tribe)|Rani]], inhabitants of [[Rügen|Rugia (Rügen)]], ''Roztoczanie'' for inhabitants of [[Rostock|Roztok (Rostock)]], ''Miśniacy'' for inhabitants of [[Meissen|Miśnia/Myszno (Meissen)]], ''Bambry'' for inhabitants of [[Bavaria Slavica]], mainly [[Veneti]], [[Vindelici]], [[Boii]], [[Volcae]], [[Iazyges]] and [[Slavs]] from regions around [[Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buch|Pernik (Nürnberg)]], [[Bamberg]] and [[Aschaffenburg|Ašaperk (Aschaffenburg)]], most of which have been deported to Poland during 12-13th centuries, e.t.c. |

|||

The above territories have been ruled by the [[Trundholm sun chariot|Solar dynasty]], hence the strucking similarities of [[historical Slavic religion]] to the ancient [[Vedas|Vedic culture]]. The [[Ikshvaku dynasty|Solar dynasty]] ([[Svarog|Swarożyce]] Jakszyce Kasprowicze [[Župan|Sperunowie]], the ancestors of [[Piast dynasty]]) was also known across Central Asia, India, Persia, Asia Minor, Europe and even Indonesia, Egypt and Nubia and was represented locally from the second millenium BC by [[Krakus|Krak]] ([[Druk]], [[Flag of Wales|Dragon]], see [[Krakow am See]]), [[Gryfici (Świebodzice)|Gryf]] ([[House of Griffins]]) and [[Duninowie|Dunin]] ([[Tuatha Dé Danann]], [[Achaeans (Homer)|Danaans]]) clans of [[Saka|Śaka]]-[[Aryan]] origin. Their cavalry protected the local [[Veneti]] from invasions of nordic cannibals, the [[Androphagi]] (current Swedes, Germans, Anglo-Saxons…), e.g. at the [[Tollense|battle of Dołęża (Tollense)]] ca. 1250 BC. Some of their degenerated and bastardised descendants were known as [[Danes]] and [[Normans]] but their native [[Sarmatian]] clans survived in [[Poland]]. |

|||

[[Eric of Pomerania|Bogusław Gryfita of Darłowo known as Eric of Pomerania]] became the first king of [[Kalmar Union]]. |

|||

The descendant of traitors and bastards (effects of centuries of [[ethnocide]]) [[Horst Kasner|Kaźmierczak-Wojciechowska vel Kasner]] known as [[Angela Merkel]] became the chancelor of Germany. |

|||

Popular Polish names for proper Germans include ''szwaby'' referring to [[Suebi]], ''saksy'' and ''sasi'' referring to [[Saxons]], ''krzyżacy'' referring to [[Teutonic Order]], ''Prusy'', ''prusacy'' and pejorative ''prusaki'' (cockroaches) all referring to [[Prussia]]). Germans living among Poles were often called ''hanysy'' (referring to [[Hans (name)|Hans]]), ''fryce'' (referring to [[Fritz]]) and ''folksdojcze'' (referring to [[Volksdeutsche]]), e.g. [[Jerzy Buzek|Georg Busseck]] or [[Donald Tusk|Donald Tosseck (Tusk)]]. |

|||

== Names from Baltic regions == |

== Names from Baltic regions == |

||

In [[Latvian language|Latvian]] and [[Lithuanian language|Lithuanian]] the names ''Vācija'' and ''Vokietija'' contain the root vāca or vākiā. Lithuanian linguist Kazimieras Būga associated this with a reference to a Swedish tribe named Vagoths in a 6th-century chronicle (cf. finn. ''Vuojola'' and eston. ''Oju-/Ojamaa'', '[[Gotland]]', both derived from the Baltic word; the ethnonym *vakja, used by the [[Votes]] (''vadja'') and the [[Sami people|Sami]], in older sources (''vuowjos''), may also be related). So the word for ''German'' possibly comes from a name originally given by West Baltic tribes to the Vikings.<ref>E. Fraenkel, Litauisches etymol. Wörterbuch (Indogerm. Bibliothek II,7) Heidelberg/Göttingen 1965, page 1272</ref> Latvian linguist Konstantīnos Karulis proposes that the word may be based on the Indo-European word ''*wek'' ("speak"), from which derive [[Old Prussian]] wackis ("war cry") or Latvian vēkšķis. Such names could have been used to describe neighbouring people whose language was incomprehensible to Baltic peoples. |

In [[Latvian language|Latvian]] and [[Lithuanian language|Lithuanian]] the names ''Vācija'' and ''Vokietija'' contain the root vāca or vākiā. Lithuanian linguist Kazimieras Būga associated this with a reference to a Swedish tribe named Vagoths in a 6th-century chronicle (cf. finn. ''Vuojola'' and eston. ''Oju-/Ojamaa'', '[[Gotland]]', both derived from the Baltic word; the ethnonym *vakja, used by the [[Votes]] (''vadja'') and the [[Sami people|Sami]], in older sources (''vuowjos''), may also be related). So the word for ''German'' possibly comes from a name originally given by West Baltic tribes to the Vikings.<ref>E. Fraenkel, Litauisches etymol. Wörterbuch (Indogerm. Bibliothek II,7) Heidelberg/Göttingen 1965, page 1272</ref> Latvian linguist Konstantīnos Karulis proposes that the word may be based on the Indo-European word ''*wek'' ("speak"), from which derive [[Old Prussian]] wackis ("war cry") or Latvian vēkšķis. Such names could have been used to describe neighbouring people whose language was incomprehensible to Baltic peoples. |

||

Those names may also derive from Slavic roots, if - then they would mean ''marauders'' or ''nomadic bandits'', which resembles similar meaning applied to |

Those names may also derive from Slavic roots, if - then they would mean ''marauders'' or ''nomadic bandits'', which resembles similar meaning applied to the [[Philistines]], by [[Nubians]] or [[People of Ethiopia|Ethiopians]]. |

||

== Names from East Asia == |

== Names from East Asia == |

||

| Line 275: | Line 259: | ||

In 19th and 20th century historiography, the Holy Roman Empire was often referred to as ''Deutsches Reich'', creating a link to the later nation state of 1871. Besides the official ''Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation'', common expressions are ''Altes Reich'' (the old Reich) and ''Römisch-Deutsches Kaiserreich'' (Roman-German Imperial Realm). |

In 19th and 20th century historiography, the Holy Roman Empire was often referred to as ''Deutsches Reich'', creating a link to the later nation state of 1871. Besides the official ''Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation'', common expressions are ''Altes Reich'' (the old Reich) and ''Römisch-Deutsches Kaiserreich'' (Roman-German Imperial Realm). |

||

===Reich and Bund defined=== |

|||

;Territorial State Names of Areas Comprising Modern Germany, Table I |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Name of the state |

|||

! National Diet |

|||

! House of regional representatives |

|||

|- |

|||

| Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (–1806) |

|||

| (did not exist) |

|||

| (Immerwährender) Reichstag |

|||

|- |

|||

| German Confederation (1815–1848/1866) |

|||

| (did not exist) |

|||

| Bundestag (officially Bundesversammlung) |

|||

|- |

|||

| German Reich ([[Paulskirchenverfassung]], 1849) |

|||

| Reichstag (Volkshaus) |

|||

| Reichstag (Staatenhaus) |

|||

|- |

|||

| North German Confederation (1866/1867–1871) |

|||

| Reichstag |

|||

| Bundesrat |

|||

|- |

|||

| German Reich (1871–1919) |

|||

| Reichstag |

|||

| Bundesrat |

|||

|- |

|||

| German Reich (1919–1933/1945) |

|||

| Reichstag |

|||

| Reichsrat |

|||

|- |

|||

| Bizone/Trizone (combination of the American, British and later also French occupation zones) |

|||

| [not existing] |

|||

| Länderrat (only 1948–1949) |

|||

|- |

|||

| Federal Republic of Germany (1949–) |

|||

| Bundestag |

|||

| Bundesrat |

|||

|- |

|||

| German Democratic Republic (1949–1990) |

|||

| Volkskammer (1949–1990) |

|||

| Länderkammer (1949–1958) |

|||

|} |

|||

;Territorial State Names of Areas Comprising Modern Germany, Table II |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

! Name of the state |

|||

! Period |

|||

! National Diet |

|||

! House of regional representatives |

|||

! Regional states |

|||

|- |

|||

| Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation |

|||

| until 1806 |

|||

| (Did not exist) |

|||

| (Immerwährender) Reichstag |

|||

| (Reichsstände) |

|||

|- |

|||

| Deutscher Bund |

|||

| 1815–1848/1866 |

|||

| (Did not exist) |

|||

| Bundesversammlung (often: Bundestag) |

|||

| Bundesstaaten |

|||

|- |

|||

| Deutsches Reich |

|||

| 1848/1849 |

|||

| Reichstag (Volkshaus) |

|||

| Reichstag (Staatenhaus) |

|||

| Staaten |

|||

|- |

|||

| Norddeutscher Bund |

|||

| 1866/1867–1871 |

|||

| Reichstag |

|||

| Bundesrat |

|||

| Bundesstaaten |

|||

|- |

|||

| Deutsches Reich |

|||

| 1871–1919 |

|||

| Reichstag |

|||

| Bundesrat |

|||

| Bundesstaaten |

|||

|- |

|||

| Deutsches Reich |

|||

| 1919–1933/1945 |

|||

| Reichstag |

|||

| Reichsrat |

|||

| Länder |

|||

|- |

|||

| Bundesrepublik Deutschland |

|||

| since 1949 |

|||

| Bundestag |

|||

| Bundesrat |

|||

| Länder (often: Bundesländer) |

|||

|- |

|||

| Deutsche Demokratische Republik |

|||

| 1949–1990 |

|||

| Volkskammer |

|||

| Länderkammer (1949–1958) |

|||

| Länder (1949–1952), Bezirke (1952–1990) |

|||

|} |

|||

=== Pre-modern Germany (pre-1800) === |

=== Pre-modern Germany (pre-1800) === |

||

| Line 386: | Line 267: | ||

Germans call themselves ''Deutsche'' (living in ''Deutschland''). ''Deutsch'' is an adjective ([[Proto-Germanic]] *''theudisk-'') derived from Old [[High German languages|High German]] ''thiota, diota'' (Proto-Germanic *''theudō'') meaning "people", "nation", "folk". The word *''theudō'' is [[cognate]] with Proto-Celtic *''teutā'', whence the Celtic tribal name [[Teuton]], later anachronistically applied to the Germans. The term was first used to designate the popular language as opposed to the language used by the religious and secular rulers who used Latin. |

Germans call themselves ''Deutsche'' (living in ''Deutschland''). ''Deutsch'' is an adjective ([[Proto-Germanic]] *''theudisk-'') derived from Old [[High German languages|High German]] ''thiota, diota'' (Proto-Germanic *''theudō'') meaning "people", "nation", "folk". The word *''theudō'' is [[cognate]] with Proto-Celtic *''teutā'', whence the Celtic tribal name [[Teuton]], later anachronistically applied to the Germans. The term was first used to designate the popular language as opposed to the language used by the religious and secular rulers who used Latin. |

||

In the [[Late Middle Ages|Late Medieval]] and [[Early Modern period]], Germany and Germans were known as ''Almany'' and ''Almains'' in English, via [[Old French]] ''alemaigne'', ''alemans'' derived from the name of the [[Alamanni]] and [[Alemannia]]. These English terms were obsolete by the 19th century. At the time, the territory of modern Germany belonged to the realm of the [[Holy Roman Empire]] (the Roman Empire restored by the Christian king of [[Franks|Francony]], [[Charlemagne]]). This feudal state became a union of relatively independent rulers who developed their own territories. |

In the [[Late Middle Ages|Late Medieval]] and [[Early Modern period]], Germany and Germans were known as ''Almany'' and ''Almains'' in English, via [[Old French]] ''alemaigne'', ''alemans'' derived from the name of the [[Alamanni]] and [[Alemannia]]. These English terms were obsolete by the 19th century. At the time, the territory of modern Germany belonged to the realm of the [[Holy Roman Empire]] (the Roman Empire restored by the Christian king of [[Franks|Francony]], [[Charlemagne]]). This feudal state became a union of relatively independent rulers who developed their own territories. Modernisation took place on the territorial level (such as Austria, Prussia, Saxony or [[Bremen]]), not on the level of the Empire. |

||

=== 1800–1871 === |

=== 1800–1871 === |

||

| Line 403: | Line 284: | ||

In German constitutional history, the expressions ''Reich'' (reign, realm, empire) and ''Bund'' (federation, confederation) are somewhat interchangeable. Sometimes they even co-existed in the same constitution: for example in the German Empire (1871–1918) the parliament had the name ''[[Reichstag (German Empire)|Reichstag]]'', the council of the representatives of the German states ''[[Bundesrat of Germany|Bundesrat]]h''. When in 1870–71 the [[North German Confederation]] was transformed into the German Empire, the preamble said that the participating monarchs are creating ''einen ewigen Bund'' (an eternal confederation) which will have the name ''Deutsches Reich''. |

In German constitutional history, the expressions ''Reich'' (reign, realm, empire) and ''Bund'' (federation, confederation) are somewhat interchangeable. Sometimes they even co-existed in the same constitution: for example in the German Empire (1871–1918) the parliament had the name ''[[Reichstag (German Empire)|Reichstag]]'', the council of the representatives of the German states ''[[Bundesrat of Germany|Bundesrat]]h''. When in 1870–71 the [[North German Confederation]] was transformed into the German Empire, the preamble said that the participating monarchs are creating ''einen ewigen Bund'' (an eternal confederation) which will have the name ''Deutsches Reich''. |

||

Due to the history of Germany, the principle of federalism is strong. Only the state of Hitler (1933–1945) and the state of the communists (East Germany, 1949–1990) were centralist states. As a result, the words ''Reich'' and ''Bund'' used more frequently than in other countries, in order to distinguish between imperial or federal institutions and those at a subnational level. For example, a modern federal German minister is called ''Bundesminister'', in contrast to a ''Landesminister'' who holds office in a state such as Rhineland-Palatinate or Lower Saxony. |

Due to the history of Germany, the principle of federalism is strong. Only the state of Hitler (1933–1945) and the state of the communists (East Germany, 1949–1990) were centralist states. As a result, the words ''Reich'' and ''Bund'' were used more frequently than in other countries, in order to distinguish between imperial or federal institutions and those at a subnational level. For example, a modern federal German minister is called ''Bundesminister'', in contrast to a ''Landesminister'' who holds office in a state such as Rhineland-Palatinate or Lower Saxony. |

||

As a result of the Hitler regime, and maybe also of Imperial Germany up to 1919, many Germans – especially those on the political left – have negative feelings about the word ''Reich''. However, it is in common use in expressions such as ''Römisches Reich'' (Roman Empire), ''Königreich'' (Kingdom) and ''Tierreich'' (animal kingdom). |

As a result of the Hitler regime, and maybe also of Imperial Germany up to 1919, many Germans – especially those on the political left – have negative feelings about the word ''Reich''. However, it is in common use in expressions such as ''Römisches Reich'' (Roman Empire), ''Königreich'' (Kingdom) and ''Tierreich'' (animal kingdom). |

||

Revision as of 14:48, 23 December 2017

Because of Germany's geographic position in the centre of Europe, as well as its long history as a non-united region of distinct tribes and states, there are many widely varying names of Germany in different languages, perhaps more so than for any other European nation. For example, in German, the country is known as Deutschland, while in the Scandinavian languages as Tyskland, in French as Allemagne, in Italian as Germania, in Polish as Niemcy, in Spanish as Alemania, in Dutch as Duitsland, and in Arabic as ألمانيا.

List of area names

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

In general, the names for Germany can be arranged in six main groups according to their origin:

- 1. From Old High German diutisc or similar[a]

- Afrikaans: Duitsland

- Chinese: 德意志 in both simpl. and trad. (pinyin: Déyìzhì)

commonly 德國/德国 (Déguó, "Dé" is the abbr. of 德意志,

"guó" means "country") - Danish: Tyskland

- Dutch: Duitsland

- Faroese: Týskland

- German: Deutschland

- Icelandic: Þýskaland

- Japanese: [[[wiktionary:ドイツ|ドイツ(独逸)]]] Error: {{Lang}}: script: jpan not supported for code: ja (help) (Doitsu)

- Korean: 독일(獨逸) (Dogil/Togil)

- Low German: Düütschland

- Luxembourgish: Däitschland

- Nahuatl: Teutōtitlan

- Norwegian: Tyskland

- Northern Sami: Duiska

- Northern Sotho: Tôitšhi

- Old English: Þēodiscland

- Swedish: Tyskland

- Vietnamese: [Đức] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

- West Frisian: Dútslân

- Yiddish: [דײַטשלאַנד] Error: {{Lang}}: script: hebr not supported for code: yi (help) (Daytshland)

- Acehnese: Jeureuman

- Albanian: Gjermania

- Aramaic:ܓܪܡܢ (Jerman)

- Armenian: Գերմանիա (Germania)

- Bengali:জার্মানি (Jarmani)

- Bulgarian: Германия (Germaniya)[b]

- Modern English: Germany

- Esperanto: Germanujo (also Germanio)

- Friulian: Gjermanie

- Georgian: გერმანია (Germania)

- Greek: Γερμανία (Germanía)

- Gujarati: જર્મની (Jarmanī)

- Hausa: Jamus

- Hebrew: גרמניה (Germania)

- Hindustani: जर्मनी / جرمنی (Jarmanī)

- Ido: Germania

- Indonesian: Jerman

- Interlingua: Germania

- Irish: An Ghearmáin

- Italian: Germania[c]

- Hawaiian: Kelemania

- Kannada: ಜರ್ಮನಿ (Jarmani)

- Lao: ເຢຍລະມັນ (Yialaman)

- Latin: Germania

- Macedonian: Германија ([Germanija] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- Malay: Jerman

- Manx: Yn Ghermaan

- Maltese: Ġermanja

- Māori: Tiamana

- Marathi: जर्मनी (Jarmanī)

- Mongolian: Герман (German)

- Nauruan: Djermani

- Nepali: जर्मनी (Jarmanī)

- Panjabi: ਜਰਮਨੀ (Jarmanī)

- Romanian: Germania[d]

- Rumantsch: Germania

- Russian: Германия (Germaniya)[e]

- Samoan: Siamani

- Scottish Gaelic: A' Ghearmailt

- Sinhala: ජර්මනිය (Jarmaniya)

- Somali: Jermalka

- Swahili: Ujerumani

- Tahitian: Heremani

- Tamil: செருமனி (cerumani), ஜெர்மனி (Jermani)

- Thai: เยอรมนี (Yoeramani), เยอรมัน (Yoeraman)

- Tongan: Siamane

- 3. From the name of the Alamanni tribe

- Arabic: ألمانيا ('Almānyā)

- Asturian: Alemaña

- Azerbaijani: Almaniya

- Basque: Alemania

- Breton: Alamagn

- Catalan: Alemanya

- Cornish: Almayn

- Filipino: Alemanya

- French: Allemagne

- Galician: Alemaña

- Kazakh: [Алмания] Error: {{Lang}}: script: cyrl not supported for code: kk (help) (Almanïya) Not used anymore or used very rarely, now using Russian "Германия".

- Khmer: ប្រទេសអាល្លឺម៉ង់ (Prateh Aloumong)

- Kurdish: Elmaniya

- Latin: Alemannia

- Mirandese: Almanha

- Occitan: Alemanha

- Piedmontese: Almagna

- Ojibwe ᐋᓂᒫ (Aanimaa)

- Persian: آلمان ('Ālmān)

- Quechua: Alimanya

- Portuguese: Alemanha

- Spanish: Alemania

- Tajik: Олмон Olmon

- Tatar: Алмания Almania

- Tetum: Alemaña

- Turkish: Almanya

- Welsh: Yr Almaen

- 4. From the name of the Saxon tribe

- 5. From the Protoslavic němьcь[f]

- Arabic: نمسا (nímsā) meaning Austria

- Belarusian: Нямеччына (Nyamyecchyna)

- Bulgarian: Немция (Nemtsiya)

- Czech: Německo

- Hungarian: Németország

- Kashubian: Miemieckô

- Montenegrin: Njemačka

- Ottoman Turkish:نمچه (Nemçe) meaning all Austrian - Holy Roman Empire countries

- Polish: Niemcy

- Serbo-Croatian: Nemačka, Njemačka / Немачка, Њемачка

- Silesian: Ńymcy

- Slovak: Nemecko

- Slovene: Nemčija

- Lower Sorbian: Nimska

- Upper Sorbian: Nemska

- Ukrainian: Німеччина (Nimecchyna)

- 6. Unclear origin[g]

- Latvian: Vācija

- Lithuanian: Vokietija

- New Curonian: Vāce Zėm

- Samogitian: Vuokītėjė

- Latgalian: Vuoceja

- Other forms

- Medieval Greek: Frángoi, frangikós (for Germans, German) – after the Franks.

- Medieval Hebrew language: אַשְׁכְּנַז (Ashkenaz) – from biblical Ashkenaz (אַשְׁכְּנַז) was the son of Japheth and grandson of Noah. Ashkenaz is thought to be the ancestor of the Germans.

- Medieval Latin: Teutonia, regnum Teutonicum – after the Teutons.

- German language: Teutonisch Land, Teutschland used in many areas until the 19th century (see Walhalla opening song), Deutschland - the current official designation.

- Tahitian language: Purutia (also Heremani, see above) – a corruption of Prusse, the French name for the German Kingdom of Prussia.

- Lower Sorbian language: bawory or bawery (in older or dialectal use) – from the name of Bavaria.

- Silesian: szwaby from Suebi or Swabia, bambry used for German peasant colonists from the area around Bamberg, Prusacy from Prussia, krzyżacy (a derogative form of krzyżowcy - crusaders) referring to Teutonic Order. Rajch or Rajś perfectly resembling German pronunciation of Reich[2] .

- Old Norse: Suðrvegr – literally south way (cf. Norway),[3] describing Germanic tribes which invaded continental Europe.

- English: Krauts from Sauerkraut (sour cabbage) consumed regularly by Germans along with Wurst.

- Kinyarwanda: Ubudage, Kirundi: Ubudagi – thought to derive from the greeting guten Tag used by Germans during the colonial times,[4] or from deutsch.[5]

- Navajo: [Béésh Bich’ahii Bikéyah] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("Metal Cap-wearer Land"), in reference to Stahlhelm-wearing German soldiers.

- Lakota: Iyášiča Makȟóčhe[6] ("Bad Speaker Land").

- Sudovian: miksiskai, Old Prussian miksiskāi (both for "German") – from miksît "to stammer".

- Polish (slang of the communist period): Erefen from R.F.N. = F.R.G. (Federal Republic of Germany),[7] dederon spicy spelling of DDR's (German Democratic Republic) own name.

- Polish (pre-Second World War slang): Rajch from German Reich[8]

Names from Diutisc

The name Deutschland and the other similar-sounding names above are derived from the Old High German diutisc, or similar variants from Proto-Germanic *Þeudiskaz, which originally meant "of the people". This in turn comes from a Germanic word meaning "folk" (leading to Old High German diot, Middle High German diet), and was used to differentiate between the speakers of Germanic languages and those who spoke Celtic or Romance languages. These words come from *teuta, the Proto-Indo-European word for "people" (Lithuanian tauta, Old Irish tuath, Old English þeod).

Also the Italian for "German", tedesco (local or archaic variants: todesco, tudesco, todisco), comes from the same Old High German root, although not the name for "Germany" (Germania). Also in the standardised Romansh language Germania is the normal name for Germany but in Sursilvan, Sutsilvan and Surmiran it is commonly referred to as Tiaratudestga, Tearatudestga and Tera tudestga respectively, with tiara/teara/tera meaning land. French words thiois, tudesque, théotisque and Thiogne and Spanish tudesco share this etymology.

The opposite of diutisc was Old High German wal(a)hisc or walesc, meaning foreign, from the Celtic tribe of the Volcae. In German, welsch is still used to mean foreign, and in particular of Romance origin; in English the word was used to describe the "Welsh" and the name stuck. (It is also used in several other European regions where Germanic peoples came into contact with non-Germanic cultures, including Wallonia (Belgium), Valais (Switzerland), and Wallachia (Romania), as well as the "-wall" of Cornwall.

The Germanic language which diutisc most likely comes from is West Frankish, a language which died out a long time ago and which there is hardly any written evidence for today. This was the Germanic dialect used in the early Middle Ages, spoken by the Franks in Western Francia, i.e. in the region which is now northern France. The word is only known from the Latin form theodiscus. Until the 8th century the Franks called their language frengisk; however, when the Franks moved their political and cultural centre to the area where France now is, the term frengisk became ambiguous, as in the West Francian territory some Franks spoke Latin, some vulgar Latin and some theodisc. For this reason a new word was needed to help differentiate between them. Thus the word theodisc evolved from the Germanic word theoda (the people) with the Latin suffix -iscus, to mean "belonging to the people", i.e. the people's language.

In Eastern Francia, roughly the area where Germany now is, it seems that the new word was taken on by the people only slowly, over the centuries: in central Eastern Francia the word frengisk was used for a lot longer, as there was no need for people to distinguish themselves from the distant Franks. The word diutsch and other variants were only used by people to describe themselves, at first as an alternative term, from about the 10th century. It was used, for example, in the Sachsenspiegel, a legal code, written in Middle Low German in about 1220: Iewelk düdesch lant hevet sinen palenzgreven: sassen, beieren, vranken unde svaven (Every German land has its Graf: Saxony, Bavaria, Franken and Swabia).

The Teutoni, a tribe with a name which probably came from the same root, did, through Latin, ultimately give birth to the English words "Teuton" (first found in 1530) for the adjective German, (as in the Teutonic Knights, a military religious order, and the Teutonic Cross) and "Teuton" (noun), attested from 1833. "Teuton" was also used for Teutonisch Land (land of the Teutons), it's abbreviation Teutschland used in some areas until the 19th century and it's currently used official variation Deutschland.

Names from Germania

The name Germany and the other similar-sounding names above are all derived from the Latin Germania, of the 3rd century BC, a word simply describing fertile land behind the limes. It was likely the Gauls who first called the people who crossed east of the Rhine Germani (which the Romans adopted) as the original Germanic tribes did not refer to themselves as Germanus (singular) or Germani (plural).[9]

Julius Caesar was the first to use Germanus in writing when describing tribes in north-eastern Gaul in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico: he records that four northern Belgic tribes, namely the Condrusi, Eburones, Caeraesi and Paemani, were collectively known as Germani. In AD 98, Tacitus wrote Germania (the Latin title was actually: De Origine et situ Germanorum), an ethnographic work on the diverse set of Germanic tribes outside the Roman Empire. Unlike Caesar, Tacitus claims that the name Germani was first applied to the Tungri tribe. The name Tungri is thought to be the endonym corresponding to the exonym Eburones.

19th-century and early 20th-century historians speculated on whether the northern Belgae were Celts or Germanic tribes. Caesar claims that most of the northern Belgae were descended from tribes who had long ago crossed the Rhine from Germania. However many tribal names and personal names or titles recorded are identifiably Celtic. It seems likely that the northern Belgae, due to their intense contact with the Gaulish south, were largely influenced by this southern culture. Tribal names were 'qualifications' and could have been translated or given by the Gauls and picked up by Caesar. Perhaps they were Germanic people who had adopted Gaulish titles or names. The Belgians were a political alliance of southern Celtic and northern Germanic tribes. In any case, the Romans were not precise in their ethnography of northern barbarians: by "German(ic)" Caesar meant "originating east of the Rhine". Tacitus wrote in his book Germania: "The Treveri and Nervii take pride in their German origin, stating that this noble blood separates them from all comparison (with the Gauls) and the Gaulish laziness".[10]

The OED2 records theories about the Celtic roots of the Latin word Germania: one is gair, neighbour (a theory of Johann Zeuss, a German historian and Celtic philologist) – in Old Irish gair is "neighbour". Another theory is gairm, battle-cry (put forward by Johann Wachter and Jacob Grimm, who was a philologist as well as collector and editor of fairy tales). Yet another theory is that the word comes from ger, "spear"; however, Eric Partridge suggests *gar / gavin, to shout (as Old Irish garim), describing the Germanic tribesmen as noisy. He describes the ger theory as "obsolete".

In English, the word "German" is first attested in 1520, replacing earlier uses of Almain, Alman and Dutch. In German, the word Germanen today refers to Germanic tribes, just like the Italian noun "Germani" (adjective: "germanici"), and the French adjective "germanique", The English words "german" (as in "cousin-german") and the adjective "germane" are not connected to the name for the country, but come from the Latin germanus, "siblings with the same parents or father"; just like Spanish "hermano", that is "brother", that is not cognate by any mean to the word "Germania".[citation needed]

Names from Alemanni

The name Allemagne and the other similar-sounding names above are derived from the southern Germanic Alemanni, a Suebic tribe or confederation in today's Alsace, parts of Baden-Württemberg and Switzerland.

The name may come from Proto-Germanic *Alamanniz which may have one of two meanings, depending on the derivation of "Al-". If "Al-" means "all", then the name means "all men" (being able and having the right to fight), suggesting that the tribe was a confederation of different groups. If "Al-" comes from the first element in Latin alius, "the other", then it is related to English "else" or "alien" and Alemanni means "foreign men".

In English, the name "Almain" or "Alman" was used for Germany and for the adjective German until the 16th century, with "German" first attested in 1520, used at first as an alternative then becoming a replacement, maybe inspired mainly by the need to differ them from the more and more independently acting Dutch. In Othello ii,3, (about 1603), for example, Shakespeare uses both "German" and "Almain" when Iago describes the drinking prowess of the English:

- I learned it in England, where, indeed, they are most potent in potting: your Dane, your German, and your swag-bellied Hollander—Drink, ho!—are nothing to your English. [...] Why, he drinks you, with facility, your Dane dead drunk; he sweats not to overthrow your Almain; he gives your Hollander a vomit, ere the next pottle can be filled.

Andrew Boorde also mentions Germany in his Introduction to Knowledge, c. 1547:

- The people of High Almain, they be rude and rusticall, and very boisterous in their speech, and humbly in their apparel .... they do feed grossly, and they will eat maggots as fast as we will eat comfits.

Through this name, the English language has also been given the Allemande (a dance), the Almain rivet and probably the almond furnace, which is probably not really connected to the word "almond" (of Greek origin) but is a corruption of "Almain furnace". In modern German, Alemannisch (Alemannic German) is a group of dialects of the Upper German branch of the Germanic language family, spoken by approximately ten million people in six different countries.

Among the indigenous peoples of North America of former French and British colonial areas, the word for "Germany" came primarily[citation needed] as a borrowing from either French or English. For example, in the Anishinaabe languages, three terms for "Germany" exist: ᐋᓂᒫ (Aanimaa, originally Aalimaanh, from the French Allemagne),[11][12] ᑌᐦᒋᒪᓐ (Dechiman, from the English Dutchman)[12] and ᒣᐦᔭᑴᑦ (Meyagwed, Ojibwe for "foreign speaker"[12] analogous to Slavic Némcy "Mutes" and Arab عجم (ajan) mute), of which Aanimaa is the most common of the terms to describe Germany.[citation needed]

Names from Saxon

The names Saksamaa and Saksa are derived from the name of the Germanic tribe of the Saxons. The word "Saxon", Proto-Germanic *sakhsan, is believed (a) to be derived from the word seax, meaning a variety of single-edged knives: a Saxon was perhaps literally a swordsman, or (b) to be derived from the word "axe", the region axed between the valleys of the Elbe and Weser.

In Finnish and Estonian the words that historically applied to ancient Saxons changed their meaning over the centuries to denote the whole country of Germany and the Germans. In some Celtic languages the word for the English nationality is derived from Saxon, e.g., the Scottish term Sassenach, the Breton terms Saoz, Saozon and the Welsh terms Sais, Saeson. "Saxon" also led to the "-sex" ending in Wessex, Essex, Sussex, Middlesex, etc., and of course to "Anglo-Saxon".

Names from Nemets

The Slavic exonym nemets, nemtsy derives from Proto-Slavic němьcь, pl. němьci, 'the mutes', 'not able (to speak)' (from adjective němъ 'mute' and suffix -ьcь).[13] It literally means a mute and can be also associated with similar sounding not able, without power, but came to signify those who can't speak (like us); foreigners. The Slavic autonym (Proto-Slavic *Slověninъ) likely derives from slovo, meaning word. According to a theory, early Slavs would call themselves the speaking people or the keepers of the words, as opposed to their Germanic neighbors, the mutes (a similar idea lies behind Greek barbaros, barbarian) and Arab عجم (ajan) mute. At first, němьci may have been used for any non-Slav foreigners, later narrowed to just Germans. The plural form is used for the Germans instead of any specific country name, e.g. Niemcy in Polish and Ńymcy in Silesian dialect. In other languages, the country's name derives from the adjective němьcьska (zemja) meaning 'German (land)' (f.i. Czech Německo). Belarusian Нямеччына (Nyamyecchyna), Bulgarian Немция (Nemtsiya) and Ukrainian Німеччина (Nimecchyna) are also from němьcь but with the addition of the suffix -ina.

According to another theory,[14][15] Nemtsy may derive from the Rhine-based, Germanic tribe of Nemetes mentioned by Caesar[16] and Tacitus.[17] This etymology is dubious for phonological nemetes could not become Slavic němьcь.[13]

In Russian, the adjective for "German", немецкий (nemetskiy) comes from the same Slavic root while the name for the country is Germaniya (Германия). Likewise, in Bulgarian the adjective is "немски" (nemski) and the country is Germaniya (Германия).

Over time, the Slavic exonym was borrowed by some non-Slavic languages. The Hungarian name for Germany is Németország (from the stem Német-. lit. Német Land). The popular Romanian name for German is neamț, used alongside the official term, german, which was borrowed from Latin. The Arabic name for Austria النمسا an-Nimsā was borrowed from the Ottoman Turkish and Persian word for Austria, "نمچه" – "Nemçe", from one of the South Slavic languages (in the 16–17th centuries the Austrian Empire was the biggest German-speaking country bordering on the Ottoman Empire) and like in Polish also doesn't refer to a specific country but only to the people occupying it.

Names from Baltic regions

In Latvian and Lithuanian the names Vācija and Vokietija contain the root vāca or vākiā. Lithuanian linguist Kazimieras Būga associated this with a reference to a Swedish tribe named Vagoths in a 6th-century chronicle (cf. finn. Vuojola and eston. Oju-/Ojamaa, 'Gotland', both derived from the Baltic word; the ethnonym *vakja, used by the Votes (vadja) and the Sami, in older sources (vuowjos), may also be related). So the word for German possibly comes from a name originally given by West Baltic tribes to the Vikings.[18] Latvian linguist Konstantīnos Karulis proposes that the word may be based on the Indo-European word *wek ("speak"), from which derive Old Prussian wackis ("war cry") or Latvian vēkšķis. Such names could have been used to describe neighbouring people whose language was incomprehensible to Baltic peoples. Those names may also derive from Slavic roots, if - then they would mean marauders or nomadic bandits, which resembles similar meaning applied to the Philistines, by Nubians or Ethiopians.

Names from East Asia

The Chinese name is a phonetic approximation of the German proper adjective. The Vietnamese name is based on the Chinese name. The Japanese name is a phonetic approximation of the Dutch proper adjective. The Korean name is based on the Japanese name. This is explained in detail below:

The common Chinese name (simplified Chinese: 德国; traditional Chinese: 德國; pinyin: Déguó) is a combination of the short form of Chinese: 德意志; pinyin: déyìzhì, which approximates the German pronunciation [ˈdɔʏ̯tʃ] of Deutsch ‘German’, plus 國 guó ‘country’.

The Vietnamese name Đức is the Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation (đức [ɗɨ́k]) of the character 德 that appears in the Chinese name.

Japanese language ドイツ (doitsu) is an approximation of the Dutch word duits meaning ‘German’.[19] It was earlier written with the Sino-Japanese character compound 獨逸 (whose 獨 has since been simplified to 独), but has been largely superseded by the above-mentioned katakana ドイツ. The character 独 is sometimes used in compounds, for example 独文 (dokubun) meaning ‘German literature’, or as an abbreviation, such as in 独日関係 (dokunichi kankei, German-Japanese relations).

The (South) Korean name Dogil (독일) is the Korean pronunciation of the former Japanese name. The compound coined by the Japanese was adapted into Korean, so its characters 獨逸 are not pronounced do+itsu as in Japanese, but dok+il = Dogil. Until the 1980s, South Korean primary textbooks adopted Doichillanteu (도이칠란트) which approximates the German pronunciation [ˈdɔʏ̯tʃ.lant] of Deutschland[citation needed].

The official North Korean name toich'willandŭ (도이췰란드) approximates the German pronunciation [ˈdɔʏ̯tʃ.lant] of Deutschland. Traditionally Dogil (독일) had been used in North Korea until the 1990s[citation needed]. Use of the Chinese name (in its Korean pronunciation Deokguk, 덕국) is attested for the early 20th century[citation needed]. It is now uncommon.

Etymological history

The terminology for "Germany", the "German states" and "Germans" is complicated by the unusual history of Germany over the last 2000 years. This can cause confusion in German and English, as well in other languages. While the notion of Germans and Germany is older, it is only since 1871 that there has been a nation-state of Germany. Later political disagreements and the partition of Germany (1945–1990) has further made it difficult to use proper terminology.

Starting with Charlemagne, the territory of modern Germany was within the realm of the Holy Roman Empire. It was a union of relatively independent rulers who each ruled their own territories. This empire was called in German Heiliges Römisches Reich, with the addition from the late Middle Ages of Deutscher Nation (of (the) German nation), showing that the former idea of a universal realm had given way to a concentration on the German territories.

In 19th and 20th century historiography, the Holy Roman Empire was often referred to as Deutsches Reich, creating a link to the later nation state of 1871. Besides the official Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation, common expressions are Altes Reich (the old Reich) and Römisch-Deutsches Kaiserreich (Roman-German Imperial Realm).

Pre-modern Germany (pre-1800)

Roman authors mentioned a number of tribes they called Germani—the tribes did not themselves use the term. After 1500 these tribes were identified by linguists as belonging to a group of Germanic language speakers (which include modern languages like German, English and Dutch). Germani (for the people) and Germania (for the area where they lived) became the common Latin words for Germans and Germany.

Germans call themselves Deutsche (living in Deutschland). Deutsch is an adjective (Proto-Germanic *theudisk-) derived from Old High German thiota, diota (Proto-Germanic *theudō) meaning "people", "nation", "folk". The word *theudō is cognate with Proto-Celtic *teutā, whence the Celtic tribal name Teuton, later anachronistically applied to the Germans. The term was first used to designate the popular language as opposed to the language used by the religious and secular rulers who used Latin.

In the Late Medieval and Early Modern period, Germany and Germans were known as Almany and Almains in English, via Old French alemaigne, alemans derived from the name of the Alamanni and Alemannia. These English terms were obsolete by the 19th century. At the time, the territory of modern Germany belonged to the realm of the Holy Roman Empire (the Roman Empire restored by the Christian king of Francony, Charlemagne). This feudal state became a union of relatively independent rulers who developed their own territories. Modernisation took place on the territorial level (such as Austria, Prussia, Saxony or Bremen), not on the level of the Empire.

1800–1871

The French emperor, Napoleon, forced the Emperor of Austria to step down as Holy Roman Emperor in 1806. Some of the German countries were then collected into the Confederation of the Rhine, which remained a military alliance under the "protection" of Napoleon, rather than consolidating into an actual confederation. After the fall of Napoleon in 1815, these states created a German Confederation with the Emperor of Austria as president. Some member states, such as Prussia and Austria, included only a part of their territories within the confederation, while other member states brought territories to the alliance that included people, like the Poles and the Czechs, who did not speak German as their native tongue. In addition, there were also substantial German speaking populations that remained outside the confederation.

In 1841 Hoffmann von Fallersleben wrote the song Das Lied der Deutschen,[20] giving voice to the dreams of a unified Germany (Deutschland über Alles) to replace the loose alliance of individual states. In this era of emerging national movements, "Germany" was used only as a reference to a particular geographical area.

In 1866/1867 Prussia and her allies left the German Confederation, which led to the confederation being dissolved and the formation of a new alliance, called the North German Confederation. The remaining South German countries, with the exception of Austria and Liechtenstein, joined this new confederation in 1870.[21] From that point forward there has been a country called "Germany".

German Federation

The first nation state named "Germany" began in 1871; before that Germany referred to a geographical entity comprising many states, much as "the Balkans" is used today, or the term "America" was used by the founders of "the United States of America."

In German constitutional history, the expressions Reich (reign, realm, empire) and Bund (federation, confederation) are somewhat interchangeable. Sometimes they even co-existed in the same constitution: for example in the German Empire (1871–1918) the parliament had the name Reichstag, the council of the representatives of the German states Bundesrath. When in 1870–71 the North German Confederation was transformed into the German Empire, the preamble said that the participating monarchs are creating einen ewigen Bund (an eternal confederation) which will have the name Deutsches Reich.

Due to the history of Germany, the principle of federalism is strong. Only the state of Hitler (1933–1945) and the state of the communists (East Germany, 1949–1990) were centralist states. As a result, the words Reich and Bund were used more frequently than in other countries, in order to distinguish between imperial or federal institutions and those at a subnational level. For example, a modern federal German minister is called Bundesminister, in contrast to a Landesminister who holds office in a state such as Rhineland-Palatinate or Lower Saxony.

As a result of the Hitler regime, and maybe also of Imperial Germany up to 1919, many Germans – especially those on the political left – have negative feelings about the word Reich. However, it is in common use in expressions such as Römisches Reich (Roman Empire), Königreich (Kingdom) and Tierreich (animal kingdom).

Bund is another word also used in contexts other than politics. Many associations in Germany are federations or have a federalised structure and differentiate between a Bundesebene (federal/national level) and a Landesebene (level of the regional states), in a similar way to the political bodies. An example is the German Football Association Deutscher Fußballbund. (The word Bundestrainer, referring to the national football coach, does not refer to the Federal Republic, but to the Fußballbund itself.)

In other German speaking countries, the words Reich (Austria before 1918) and Bund (Austria since 1918, Switzerland) are used too. An organ named Bundesrat exists in all three of them: in Switzerland it is the government and in Germany and Austria the house of regional representatives.

Greater Germany and "Großdeutsches Reich"

In the 19th century before 1871, Germans, for example in the Frankfurt Parliament of 1848–49, argued about what should become of Austria. Including Austria (at least the German-speaking parts) in a future German state was referred to as the Greater German Solution; while a German state without Austria was the Smaller German Solution.

In 1919 the Weimar Constitution postulated the inclusion of Deutsch-Österreich (the German-speaking parts of Austria), but the Western Allies objected to this. It was realised only in 1938 when Germany annexed Austria (Anschluss). National socialist propaganda proclaimed the realisation of Großdeutschland; and in 1943 the German Reich was officially renamed Großdeutsches Reich. However, these expressions became neither common nor popular.

In National Socialist propaganda Austria was also called Ostmark. After the Anschluss the previous territory of Germany was called Altreich (old Reich).

German Empire and Weimar Republic of Germany, 1871–1945

The official name of the German state in 1871 became Deutsches Reich, linking itself to the former Reich before 1806. This expression was commonly used in official papers and also on maps, while in other contexts Deutschland was more frequently used.

Those Germans living within its boundaries were called Reichsdeutsche, those outside were called Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans). The latter expression referred mainly to the German minorities in Eastern Europe. Germans living abroad (for example in America) were and are called Auslandsdeutsche.

After the forced abdication of the Emperor in 1918, and the republic was declared, Germany was informally called the Deutsche Republik. The official name of the state remained the same. The term Weimar Republic, after the city where the National Assembly gathered, came up in the 1920s, but was not commonly used until the 1950s. It became necessary to find an appropriate term for the Germany between 1871 and 1919: Kaiserliches Deutschland (Imperial Germany) or (Deutsches) Kaiserreich.

Nazi Germany

After Adolf Hitler took power in 1933, the official name of the state was still the same. For a couple of years Hitler used the expression Drittes Reich (Third Reich), which was introduced by writers in the last years of the republic. In fact this was only a propaganda term and did not constitute a new state. Another propaganda term was Tausendjähriges Reich (Thousand years Reich). Later Hitler renounced the term Drittes Reich (officially in June 1939), but it already had become popular among supporters and opponents and is still used in historiography (sometimes in quotation marks).[22] It led later to the name Zweites Reich (Second Empire) for Germany of 1871–1919. The reign of Hitler is most commonly called in English Nazi Germany. Nazi is a colloquial short for Nationalsozialist.

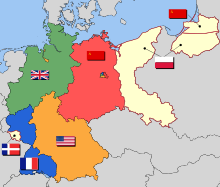

Germany divided 1945–1990

After the defeat in World War II, Germany was occupied by the troops of Britain, France, the United States and Soviet Union.

Berlin was a case of its own, as it was situated on the territory of the Soviet zone but divided into four sectors. The western sectors were later called West Berlin, the other one East Berlin. The communists tended to consider the Soviet sector of Berlin as a part of GDR; West Berlin was, according to them, an independent political unit.

After 1945, Deutsches Reich was still used for a couple of years (in 1947, for instance, when the Social Democrats gathered in Nuremberg they called their rally Reichsparteitag). In many contexts, the German people still called their country Germany, even after two German states were created in 1949.

Federal Republic of Germany

The Federal Republic of Germany, Bundesrepublik Deutschland, established in 1949, saw itself as the same state founded in 1871 but Reich gave place to Bund. For example, the Reichskanzler became the Bundeskanzler, reichsdeutsch became bundesdeutsch, Reichsbürger (citizen of the Reich) became Bundesbürger.

Germany as a whole was called Gesamtdeutschland, referring to Germany in the international borders of 1937 (before Hitler started to annex other countries). This resulted in all German (or pan germanique—a chauvinist concept) aspirations. In 1969 the Federal Ministry for All German Affairs was renamed the Federal Ministry for Intra-German Relations.

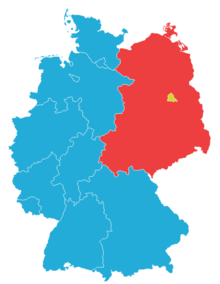

Until 1970, the other German state (the communist German Democratic Republic) was called Sowjetische Besatzungszone (SBZ, Soviet Zone of Occupation), Sowjetzone, Ostzone, Mitteldeutschland or Pankow (the GDR government was in Berlin-Pankow).

German Democratic Republic

In 1949, the communists, protected by the Soviet Union, established the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR, German Democratic Republic, GDR). This state was not considered to be a successor of the Reich, but, nevertheless, to represent all good Germans. Rulers and inhabitants of GDR called their state simply DDR or unsere Republik (our republic). The GDR still supported the idea of a German nation and the need for reunification. The Federal Republic was often called Westdeutschland or the BRD. After 1970 the GDR called itself a "socialist state of German nation". Westerners called the GDR Sowjetische Besatzungszone (SBZ, Soviet Zone of Occupation), Sowjetzone, Ostzone, Mitteldeutschland or Pankow (the GDR government was in the Pankow district of Berlin).

Federal Republic of Germany 1990–present

In 1990 the German Democratic Republic ceased to exist. Five "neue Bundesländer" (new federal states) were established and joined the "Bundesrepublik Deutschland" (Federal Republic of Germany). East Berlin joined through merger with West Berlin; technically this was the sixth new federal state since West Berlin, although considered a de facto federal state, had the legal status of a military occupation zone.

The official name of the country is Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland). The terms "Westdeutschland" and "Ostdeutschland" are still used for the western and the eastern parts of the German territory, respectively.

-

The Holy Roman Empire, 1789

-

German Confederation, 1815–1866

-

Germany (Deutsches Reich), 1871–1918

-

Germany (Deutsches Reich), 1919–1937

-

Nazi Germany, 1944

See also

- Various terms used for Germans

- German placename etymology

- List of country name etymologies

- Territorial evolution of Germany

Notes

- ^ Diutisc or similar, from Proto-Germanic *Þeudiskaz, meaning "of the people", "of the folk"

- ^ While the Bulgarian name of the country belongs to the second category, the demonym is "немски" (nemski), belonging to the fifth category

- ^ While the Italian name of the country belongs to the second category, the demonym is tedesco, belonging to the first category