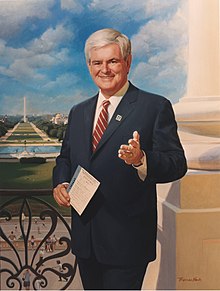

Newt Gingrich

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Newt Gingrich | |

|---|---|

| |

| 58th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives | |

| In office January 4 1995 – January 3 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Tom Foley |

| Succeeded by | Dennis Hastert |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 6th district | |

| In office 1979–1999 | |

| Preceded by | Jack Flynt |

| Succeeded by | Johnny Isakson |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Jackie Battley (divorced)

Marianne Ginther (divorced) Callista Gingrich |

| Signature | File:GingrichSig.gif |

Newton Leroy Gingrich (born June 17, 1943) served as the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999. In 1995, Time Magazine selected him as the Man of the Year for his role in leading the Republican Revolution in the House, ending 40 years of Democratic Party majorities in the House. During his tenure as Speaker he represented the public face of the Republican opposition to Bill Clinton.

A college history professor and prolific author, Gingrich twice ran unsuccessfully for the House before first winning a seat in November 1978. He was re-elected 10 times, and his activism as a member of the House's Republican minority eventually enabled him to succeed Dick Cheney as House Minority Whip in 1989. As a co-author of the 1994 Contract with America, Gingrich was in the forefront of the Republican Party's dramatic success in the 1994 Congressional elections and subsequently was elected Speaker. Gingrich's leadership in Congress was marked by opposition to many of the policies of the Clinton Administration, culminating in the impeachment of President Clinton shortly after Gingrich resigned as Speaker (the House was technically leaderless at this time, as Gingrich's chosen successor Robert Livingston of Louisiana also stepped down before he could be elected Speaker).

After resigning his seat under pressure from several sides, Gingrich has maintained a career as a political analyst and consultant and continues to write works related to government and other subjects, such as historical fiction. He has expressed interest in being a candidate for the 2008 Republican nomination for the Presidency.[1]

Early life and education

He was born Newton McPherson in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the son of Newton Searles McPherson and Kathleen Daugherty.[2] His parents separated soon after Newt's birth, and his mother raised him by herself until she married Robert Gingrich, who adopted Newt. Gingrich has a younger half-sister, Candace Gingrich, who was born when he was already a young adult. Gingrich's adopted surname has been generally pronounced "Ging-ritch" since his entry into public life. However, his adoptive family has always pronounced the name "Gin-grick", as would be customary in the Pennsylvania Dutch ethnic milieu.

Gingrich was the child of a career military family, moved a number of times growing up, attended school at various military installations and graduated from Baker High School in Columbus, Georgia, in 1961. He received a B.A. degree from Emory University in Atlanta in 1965. He received an M.A. in 1968 and Ph.D. in 1971 in Modern European History from Tulane University in New Orleans. He taught history at West Georgia College in Carrollton, Georgia, from 1970 to 1978, although he was denied tenure.[3]

Personal life

In 1962, Gingrich married, Jackie Battley, with whom he had two daughters. They were divorced in early 1980. Gingrich married Marianne Ginther, in late 1981.[4] They divorced in 1999,said to be because of Marianne's dislike of Washington and Newt's time away from home. Newt later married Callista Bisek, a House aide. Mr. Gingrich resides in Virginia with Callista, who is shown with him on the back cover of his book "Winning the Future"[5] The Gingrich Family includes two daughters, two sons-in-law, and two grandchildren.

Early elections

In 1974 and 1976, Gingrich made two unsuccessful runs for Congress in Georgia's sixth congressional district, which stretched from the southern Atlanta suburbs to the Alabama border. Gingrich lost both times to incumbent Democrat Jack Flynt.

Flynt was a conservative Democrat who had served in Congress since 1955 and never faced a serious challenge prior to Gingrich's two runs against him. In both cases, Flynt barely squeaked by even though 1974 and 1976 were generally considered bad years for Republicans due to the Watergate scandal. Flynt's struggle, which was emblematic of the struggle of many southern Democrats to hold onto political power, is documented in Richard Fenno's Congress at the Grassroots.

Flynt chose not to run for re-election in 1978, and the Democrats fielded state senator Virginia Shapard in his place. Shapard's support of the Equal Rights Amendment [2] backfired against her in the socially conservative district, and Gingrich defeated her by eight percentage points.

United States Representative

Gingrich was reelected 10 times, facing only one truly difficult race, in the House elections of 1990 when he barely defeated Democrat David Worley.

Pre-speakership congressional activities

In 1981, Gingrich co-founded the Congressional Military Reform Caucus as well as the Congressional Space Caucus. In 1983 he founded the Conservative Opportunity Society, a group that included young conservative House Republicans. In 1983, Gingrich demanded the expulsion of fellow representatives Dan Crane and Gerry Studds for their roles in the Congressional Page sex scandal.

In May 1988, Gingrich (along with 77 other House members and the nonpartisan good-government group Common Cause) brought ethics charges against Democratic Speaker Jim Wright, who was alleged to have used a book deal to circumvent campaign-finance laws and House ethics rules and eventually resigned as a result of the inquiry. Gingrich's success in forcing Wright's resignation was in part responsible for his rising influence in the Republican caucus. In 1989, after House Minority Whip Dick Cheney was appointed Secretary of Defense, Gingrich was elected to succeed him. Gingrich and others in the house, especially the newly minted Gang of Seven, railed against what they saw as ethical lapses in the House, an institution that had been under Democratic control for almost 40 years. The House banking scandal and Congressional Post Office Scandal were emblems of this alleged corruption.

Election of 1992

During the 1990s round of redistricting, Georgia picked up an additional seat as a result of the 1990 United States Census. However, the Democratic-controlled General Assembly tried to draw Gingrich's district from under him. They split Gingrich's old territory among three other districts. Gingrich's home in Carrollton was drawn into the Columbus-based 3rd District, represented by five-term Democrat Richard Ray.

At the same time, they created a new 6th District in Fulton and Cobb counties in the wealthy northern suburbs of Atlanta — an area Gingrich had never represented. However, the plan backfired when Gingrich sold his home in Carrollton, moved to Marietta in the new 6th and won a very close Republican primary. The primary victory was tantamount to election in the new, heavily Republican district. Also, Ray narrowly lost to Republican state senator Mac Collins.

Speaker of the House

The Contract with America and rise to Speaker

In the 1994 campaign season, in an effort to offer a concrete alternative to shifting Democratic policies and to unite distant wings of the Republican Party, Gingrich presented Richard Armey's and his Contract with America. The contract was signed by himself and other Republican candidates for the House of Representatives. The contract ranged from issues with broad popular support, including welfare reform, term limits, tougher crime laws, and a balanced budget law, to more specialized legislation such as restrictions on American military participation in U.N. missions. In the November 1994 elections, Republicans gained 54 seats and took control of the House for the first time since 1954.

Longtime House Minority Leader Bob Michel of Illinois had not run for re-election in 1994, giving Gingrich, as the highest-ranking Republican returning to Congress, the inside track to becoming Speaker. Congress fulfilled Gingrich's Contract promise to bring all 10 of the Contract's issues to a vote within the first 100 days of the session. Legislation proposed by the 104th Congress included term limits for Congressional Representatives, tax cuts, welfare reform, and a balanced budget law, as well as independent auditing of the finances of the House of Representatives and elimination of non-essential services such as the House barbershop and shoe-shine concessions. Most parts of the Contract eventually became law in some fashion and represented a dramatic departure from the legislative goals and priorities of previous Congresses. But most legislation was held up in the Senate or was vetoed by President Bill Clinton, were substantially altered in negotiations with Clinton, or even struck down as unconstitutional. See Implementation of the Contract for a detailed discussion of what was and was not enacted.

The Contract was criticized by the liberal Sierra Club and by the leftist labor magazine Mother Jones as a Trojan horse tactic that, while deploying the rhetoric of reform, would have the real effect of allowing corporate polluters to profit at the expense of the environment;[6] it was also accused of being designed to make the rich richer at the expense of the poor and middle class.[7] It was referred to by opponents, including President Clinton, as the "Contract on America" (where a "contract on" somebody is an agreement to have them killed). Though despite these accusations the contract caused the first budget surplus in years and spurred economic growth.

Government shutdown and the Air Force One "snub"

The momentum of the Republican Revolution stalled in late 1995 and early 1996 as a result of a budget fight between Congressional Republicans and President Bill Clinton. Speaker Gingrich and the new Republican majority refused to break their campaign promise and raise the government's spending budget. So Without enough votes to override President Clinton's veto, Gingrich led the Republicans not to submit a revised budget, allowing the previously approved appropriations to expire on schedule, and causing parts of the Federal government to shut down for lack of funds. This showed that Gingrich was a tough politician and could get things done, just like the conservative voters had wanted

Newt inflicted a temporary blow to his public image by suggesting that the Republican hard-line stance over the budget was in part due to his feeling "snubbed" by the President the day before following his return from Yitzhak Rabin's funeral in Israel. Gingrich was lampooned in the media as a petulant figure with an inflated self-image, and editorial cartoons depicted him as having thrown a temper tantrum. Democratic leaders took the opportunity to attack Gingrich's motives for the budget standoff, and some say the shutdown might have contributed to Clinton's re-election in November 1996.[8][9]

Ethics charges

Gingrich was accused of hypocrisy and unethical behavior in the media when he accepted an advance as part of a book deal, in light of his previous role in the investigation of Jim Wright; though the Wright ordeal was vastly different in circumstances. Following the accusations, Gingrich returned the advance, despite his intention to donate the money.

Including charges related to the book deal, Democrats hoping to gain political points filed 84 ethics charges against Speaker Gingrich during his term, including claiming tax-exempt status for a college course run for political purposes and using the GOPAC political action committee as a slush fund; see Joseph Gaylord. All charges were eventually dropped following an investigation by the House Ethics Committee.[10] He made up for the cost of the investigation by reimbursing the Committee $300,000.[11] In 1995 thousands of ads attacking Newt were run all over the country characterizing him as a mean spirited powermonger; this is especially interesting since it wasn't even an election year.

Coup attempt of 1997

In the summer of 1997, a few House Republicans had come to see Gingrich's public image as a liability and attempted to replace him as Speaker. According to Joe Scarborough of Florida, a member of the Republican freshman class of 1994, the coup attempt resulted from a view that Gingrich's public notoriety was becoming a drag on party efforts. House Majority Leader Dick Armey started his efforts in 1997 by whispering to so-called "rebels" tired of Gingrich's leadership. Armey and other Republican leaders started approaching these rebels after the Fourth of July break in 1997.

Twenty-four House Republicans met on the night of July 10 in South Carolina congressman Lindsey Graham's office in an attempt to vacate the Speaker's chair. A simple majority was needed to oust Gingrich; when Democrats' votes were included with those of the dissident Republicans, he would have to step aside. However, due to a last-minute disagreement between Armey and Tom Coburn over whether Bill Paxon or Armey should become the new speaker, Armey informed Gingrich his position as Speaker was at risk. Gingrich and the House leadership quickly and successfully moved to restore order within the party, and Paxon didn't run for re-election in 1998. However, the incident would prove a precursor of Gingrich's future prospects as Speaker. This incident angered some conservatives who thought the House Republicans were becoming more concerned with being reelected than staying true to the Contract with America.

Fall from speakership, resignation from the House

By 1998, Gingrich had become a highly visible and polarizing figure in the public's eye, making him an easy target for Democratic congressional candidates across the nation. In 1997 a strong majority of Americans believed Gingrich should have been replaced as Speaker of the House, and he held an all-time low job approval rating of 28%.[12] During this period, Gingrich was at the forefront of Republican calls for the investigation and impeachment of President Clinton for committing perjury by lying under oath during the Lewinsky scandal,[citation needed] and he focused on the perjury charges as a unifying campaign theme in national Republican advertising. Republicans did not focus on the tryst itself but rather the perjurious statements made by the President in connection with the incident. Democratic candidates in races across the country targeted Gingrich specifically during the campaign season. The Democratic efforts would ultimately prove successful, although it was Republican insiders who forced Gingrich to resign.[citation needed]

The Republicans expected big gains from the 1998 Congressional elections. In fact, Gingrich predicted a 30-seat Republican pickup.[citation needed] Instead, the Republicans lost five seats, the poorest results in 64 years for any party not in control of the White House in a midterm election. Having led the GOP to focus on the impeachment project as a principal strategy, Gingrich took most of the blame for the defeat. Facing a rebellion in the Republican caucus, he announced on November 6 that he would not only stand down as Speaker, but would leave the House as well. He had been elected to an 11th term in that election, but declined to take his seat. After seeing the damage his image was doing to his party, Newt had stepped down for the greater good. According to Newsweek, he had lost control over his caucus long before the election, and it was possible that he would not have been reelected as Speaker in any case.[13] Though it may seem very odd that a scandal-ridden President in his sixth year elections would not lose any seats, let alone gain any, the abundance of ads against Gingrich overshadowed it all in the public's eye.

Gingrich's role as master GOP strategist ended with his departure from the House, but his legacy in Republican leadership remains.[original research?]

Legacy in politics and language

A major part of Gingrich's legacy as a politician has been in achieving the effective use of language and the news media to further political goals.

Gingrich took the chair of the Republican political action committee GOPAC in 1986 and transformed it into an effective vehicle for electing conservative candidates to office. This was accomplished in significant part by establishing and promoting a consistent language and theme for use by Republicans at all electoral levels. This theme, in Gingrich's own words, was that of "a conservative opportunity society replacing the liberal welfare state", emphasizing "workfare over welfare" and promoting the idea that "we are the majority." GOPAC training tapes were sent to GOP candidates throughout the country.

At the start of the Republican Revolution, Gingrich's and GOPAC's efforts had succeeded in dictating the theme of national political debate at the time.

Post-congressional life

Gingrich has since remained involved in national politics and public policy debate. He is a senior fellow at the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute, focusing on health care (he has founded the Center for Health Transformation), information technology, the military, and politics. He sometimes serves as a commentator, guest or panel member on television news shows, mostly on the Fox News Channel. He is listed as a contributor by Fox News Channel, and frequently appears as a guest on the channel; he has also hosted occasional specials for the FNC.

In June 2006 Gingrich publicly called for Congressman Jack Murtha to be censured by the United States Congress for what Gingrich claims was Murtha's statement that America was a greater threat to world stability than Iran or North Korea. The paper which originally printed the statement has recently backed away and admitted that Murtha had been misquoted and was merely citing a poll that showed the world believed the United States was a greater threat than either of those nations. Gingrich, however, has refused to apologize or retract his call for Murtha to be censured.[15] Gingrich added the following comments:

"It's conceivable that Murtha woke up one day a year ago and said, 'You know, if I don't start bashing America, and bashing the military, and repudiating everything I've stood for my whole life, these guys aren't going to allow me to be chairman of the committee that spends the money.'"

Possible 2008 presidential run

Since the release of Winning the Future: A 21st Century Contract with America in January 2005, Gingrich has been mentioned as a potential Presidential candidate for the 2008 U.S. presidential election. He has made several trips to Iowa and New Hampshire to discuss his book and on April 1, 2005, David Yepsen wrote in the Des Moines Register that Gingrich was "setting a high standard for what other GOP candidates need to be talking about - and doing - if they want to win here."[citation needed] Gingrich has voiced criticism against the Republican Party, and has argued that the party must adapt if it is to remain a dominant force in US politics. In June 2006, a grassroots website was formed to draft Newt for president. The website is online at www.draftnewt.org

In 2005, Newt Gingrich and his wife Callista established the Newt L. and Callista L. Gingrich Scholarship for instrumental music majors at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. (Gingrich's wife is a Luther alumna.)[14]

On October 13, 2005, Gingrich suggested he's actually considering a run for president, saying "There are circumstances where I will run", elaborating that those circumstances would be if no other candidate champions some of the platform ideas advocated by Gingrich.[3].

In March 2006, Gingrich began a regular series of daily radio commentaries, titled "Winning the Future", the same as his recent book. These commentaries are modeled after Ronald Reagan's radio addresses in the mid-1970s.

On April 29, 2006, supporters of Gingrich launched http://www.draftnewt.org to form a grassroots movement to support a possible Gingrich run for the Presidency.

On June 2, 2006, the Minnesota Republican Party at their state convention held a straw poll for the GOP nomination in 2008.[citation needed] Gingrich came in first place at 40%, with the next highest in the straw poll of GOP delegates being Senator George Allen at 15%.

Has regularly appeared on Fox News as a regular guest and contributor[15] commenting on the 2008 Presidential Campaign. In February 2007, during an interview on "Fox News Sunday", Gingrich said, "I'll come back this summer at some point, if you'll have me, and we'll talk about how bored people are with this campaign".[16]

In early Republican primary polls Newt is in third and sometimes second place, despite not being in the race yet like the other candidates.

Books authored

Nonfiction

- The Government's Role in Solving Societal Problems. Associated Faculty Press, Incorporated. January 1982 ISBN 0-86733-026-0

- Window of Opportunity. Tom Doherty Associates, December 1985. ISBN 0-312-93923-X

- Contract with America (co-editor). Times Books, December 1994. ISBN 0-8129-2586-6

- Restoring the Dream. Times Books, May 1995. ISBN 0-8129-2666-8

- Quotations from Speaker Newt. Workman Publishing Company, Inc., July 1995. ISBN 0-7611-0092-X

- To Renew America. Farrar Straus & Giroux, July 1996. ISBN 0-06-109539-7

- Lessons Learned The Hard Way. HarperCollins Publishers, May 1998 ISBN 0-06-019106-6

- Presidential Determination Regarding Certification of the Thirty-Two Major Illicit Narcotics Producing and Transit Countries. DIANE Publishing Company, September 1999. ISBN 0-7881-3186-9

- Saving Lives and Saving Money. Alexis de Tocqueville Institution, April 2003. ISBN 0-9705485-4-0

- Winning the Future. Regnery Publishing, January 2005. ISBN 0-89526-042-5

- Rediscovering God in America: Reflections on the Role of Faith in Our Nation's History and Future. Integrity Publishers, October 2006. ISBN 1-59145-482-4

Alternative history collaboration with William R. Forstchen

In 1995, he collaborated with William R. Forstchen on the alternate history novel 1945, describing a 1945 where the US fought against (and defeated) Japan only, Nazi Germany defeated the Soviet Union and the two confront each other in a cold war which swiftly turns hot.

Among other things it was described as being "a disguised tract against gun control", as the key scene depicts an armed Tennessee civilian militia, led by Alvin York, defeating Otto Skorzeny's commandos, who raid Oak Ridge. It ended with a cliffhanger - Rommel invading Scotland and the British facing a desperate fight - but a promised sequel, provisionally called "Fortress Europa", was never written.

Instead, Gingrich and Forstchen turned to co-authoring an alternative history of the Civil War, in which the Confederacy wins the battle of Gettysburg. The trilogy consists of Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, Grant Comes East, and Never Call Retreat: Lee and Grant - The Final Victory.

References

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (2006-06-10). "Gingrich May Run in 2008 if No Frontrunner Emerges". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Biography of Newton Gingrich". U.S. Congressional Library. 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (1996-02-26). "America's New Class System". CNN/Time. Retrieved 2006-08-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Good Newt, Bad Newt". Vanity Fair (via PBS).

- ^ "Gingrich weds in simple ceremony". CNN.com (via AP). 2000-08-19. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Contract on America's Environment". The Planet Newsletter. Sierra Club. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ Garrett, Major (March/April 1995). "Beyond the Contract". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hollman, Kwame (1996-11-20). PBS.org "The State of Newt". PBS. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Murdock, Deroy (2000-08-28). NationalReview.com "Newt Gingrich's Implosion". National Review. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Farnsworth, Elizabeth (1996-12-23). "EMBATTLED LEADER". PBS. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Yang, John E. and Dewar, Helen (1997-01-18). washingtonpost.com "Ethics Panel Supports Reprimand of Gingrich". Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holland, Keating (1997-04-18). "Poll: Majority Says Gingrich Loan 'Inappropriate'". CNN. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ [1]

- ^ "Gingrich Foundation establishes scholarship fund at Luther College". Decorah Newspapers. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ "Fox News Channel Guest and Contributors". Retrieved 2007-02-117.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Gingrich Says People Bored by Presidential Race". Associated Press, February 18, 2007.

Books

- Fenno Jr., Richard F. (2000). Congress at the Grassroots: Representational Change in the South, 1970-1998. UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-4855-7.

Journals

- Little, Thomas H. (1998). "On the Coattails of a Contract: RNC Activities and Republicans Gains in the 1994 State Legislative Elections". Political Research Quarterly. 51 (1): 173–190.

Web

- "GINGRICH, Newton Leroy - Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved February 4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Titles List". Library of Congress Online Catalog. Retrieved December 5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- United States Congress. "Newt Gingrich (id: G000225)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Senior Fellow at AEI, The American Enterprise Institute

- Winning the Future, a weekly column by Gingrich at Human Events

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Newt Gingrich - full access article

- FEC - Newton L Gingrich campaign financial reports and data

- The New York Times - Newt Gingrich News news stories and commentary

- Profile: Newt Gingrich, Notable Names Database

- On the Issues - Newt Gingrich issue positions and quotes

- Open Secrets - Newt Gingrich campaign contributions 1998 cycle

- Project Vote Smart - Newton Leroy 'Newt' Gingrich (GA) profile

- SourceWatch - Newt Gingrich profile

- Washington Post The Presidential Field - Newt Gingrich

- Mother Jones expose detailing the earliest days of Gingrich's political career, November 1, 1984

- Gingrich comment on shutdown labeled 'bizarre' by White House CNN, November 16, 1995

- PBS Frontline documentary on Gingrich

- Salon contemporary comments on Gingrich's resignation as Speaker, November, 1998

- Salon on Gingrich's resignation, November, 1998

- PBS Gingrich interview on the Tavis Smiley show, January 30, 2006

- The Gingrich RX ScribeMedia.org, December 15, 2006

- The Genuine Danger of Terrorism - Gingrich Speech in New Hampshire

- 1943 births

- Living people

- American adoptees

- American Enterprise Institute

- Baptists

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Georgia

- People from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- People from McLean, Virginia

- Speakers of the United States House of Representatives

- Time magazine Persons of the Year

- Tulane University alumni

- American Christians

- Congressional scandals

- Military brats