Death

Death is the permanent end of the life of a biological organism. Death may refer to the end of life as either an event or condition.[1] Many factors can cause or contribute to an organism's death, including predation, disease, habitat destruction, senescence, malnutrition and accidents. The principal causes of death in modern human societies are diseases related to aging.[1] Traditions and beliefs related to death are an important part of human culture, and central to many religions. In medicine, biological details and definitions of death have become increasingly complicated as technology advances.

Biology

Fate of dead organisms

In animals, small movements of the limbs (for example twitching legs or wings) known as a postmortem spasm can sometimes be observed following death. Pallor mortis is a postmortem paleness which accompanies death due to a lack of capillary circulation throughout the body. Algor mortis describes the predictable decline in body temperature until ambient temperature is reached. Within a few hours of death rigor mortis is observed with a chemical change in the muscles, causing the limbs of the corpse to become stiff (Latin rigor) and difficult to move or manipulate. Assuming mild temperatures, full rigor occurs at about 12 hours, eventually subsiding to relaxation at about 36 hours. Decomposition isn't always a slow process however - for example fire is the primary mode of decomposition in most grassland ecosystems.[2]

After death an organism's remains become part of the biogeochemical cycle. Animals may be consumed by a predator or scavenger. Organic material may then be further decomposed by detritivores, organisms which recycle detritus, returning it to the environment for reuse in the food chain. Examples include earthworms, woodlice and dung beetles. Microorganisms also play a vital role, raising the temperature of the decomposing material as they break it down into simpler molecules. Not all material need be decomposed fully however; for example coal is a fossil fuel formed in swamp ecosystems where plant remains were saved by water and mud from oxidization and biodegradation.

Some organisms have hard parts such as shells or bones which may not decompose and become fossilized. Fossils are the mineralized or otherwise preserved remains or traces (such as footprints) of animals, plants, and other organisms. The totality of fossils, both discovered and undiscovered, and their placement in fossiliferous (fossil-containing) rock formations and sedimentary layers (strata) is known as the fossil record. The study of fossils across geological time, how they were formed, and the evolutionary relationships between taxa (phylogeny) are some of the most important functions of the science of paleontology.

Using radiometric dating techniques, geologists have determined most fossils to be several thousands to several billions of years old. Yet there is no minimum age for a fossil. Fossils vary in size from microscopic, such as single cells, to gigantic, such as dinosaurs. A fossil normally preserves only a portion of the deceased organism, usually that portion that was partially mineralized during life, such as the bones and teeth of vertebrates, or the chitinous exoskeletons of invertebrates. Preservation of soft tissues is extremely rare in the fossil record.

Extinction

In biology and ecology, extinction is the cessation of existence of a species or group of taxa, reducing biodiversity. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of that species (although the capacity to breed and recover may have been lost before this point). Because a species' potential range may be very large, determining this moment is difficult, and is usually done retrospectively. This difficulty leads to phenomena such as Lazarus taxa, where a species presumed extinct abruptly "re-appears" (typically in the fossil record) after a period of apparent absence.

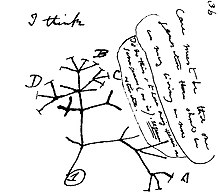

Through evolution, new species arise through the process of speciation — where new varieties of organisms arise and thrive when they are able to find and exploit an ecological niche — and species become extinct when they are no longer able to survive in changing conditions or against superior competition. A typical species becomes extinct within 10 million years of its first appearance,[4] although some species, called living fossils, survive virtually unchanged for hundreds of millions of years. Only one in a thousand species that have existed remain today.[4][5]

Prior to the dispersion of humans across the earth, extinction generally occurred at a continuous low rate, interspersed with rare mass extinction events. Starting approximately 100,000 years ago, and coinciding with an increase in the numbers and range of humans, species extinctions have increased to a rate unprecedented[6] since the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event. This is known as the Holocene extinction event and is at least the sixth such extinction event. Some experts have estimated that up to half of presently existing species may become extinct by 2100.[7]

Competition and natural selection

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Death is an important part of the process of natural selection. Organisms that are less fit for their current environment than others are more likely to die having produced fewer offspring than their more fit cousins, differentially reducing their contribution to the gene pool of succeeding generations. Weaker genes are thus eventually bred out of a population, leading to processes such as speciation and extinction. It should be noted however that reproduction also plays an equally important role in determining survival, for example an organism that dies young but leaves many offspring will be much fitter than a long lived one which leaves only one.

Evolution of aging

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Enquiry into the evolution of ageing aims to explain why almost all living things weaken and die with age. There is not yet agreement in the scientific community on a single answer. The evolutionary origin of senescence remains one of the fundamental, unsolved problems of biology.

In medicine

Definition

Historically, attempts to define the exact moment of death have been problematic. Death was once defined as the cessation of heartbeat (cardiac arrest) and of breathing, but the development of CPR and prompt defibrillation have rendered the previous definition inadequate because breathing and heartbeat can sometimes be restarted. This is now called "clinical death". Events which were causally linked to death in the past no longer kill in all circumstances; without a functioning heart or lungs, life can sometimes be sustained with a combination of life support devices, organ transplants and artificial pacemakers.

Today, where a definition of the moment of death is required, doctors and coroners usually turn to "brain death" or "biological death": People are considered dead when the electrical activity in their brain ceases (cf. persistent vegetative state). It is presumed that a stoppage of electrical activity indicates the end of consciousness. However, suspension of consciousness must be permanent, and not transient, as occurs during sleep, and especially a coma. In the case of sleep, EEGs can easily tell the difference. Identifying the moment of death is important in cases of transplantation, as organs for transplant must be harvested as quickly as possible after the death of the body.

The possession of brain activity, or ability to resume brain activity, is a necessary condition to legal personhood in the United States. "It appears that once brain death has been determined … no criminal or civil liability will result from disconnecting the life-support devices." (Dority v. Superior Court of San Bernardino County, 193 Cal.Rptr. 288, 291 (1983))

Those maintaining that only the neo-cortex of the brain is necessary for consciousness sometimes argue that only electrical activity there should be considered when defining death. Eventually it is possible that the criterion for death will be the permanent and irreversible loss of cognitive function, as evidenced by the death of the cerebral cortex. All hope of recovering human thought and personality is then gone. However, at present, in most places the more conservative definition of death — irreversible cessation of electrical activity in the whole brain, as opposed to just in the neo-cortex — has been adopted (for example the Uniform Determination Of Death Act in the United States). In 2005, the case of Terri Schiavo brought the question of brain death and artificial sustenance to the front of American politics.

Even by whole-brain criteria, the determination of brain death can be complicated. EEGs can detect spurious electrical impulses, while certain drugs, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, or hypothermia can suppress or even stop brain activity on a temporary basis. Because of this, hospitals have protocols for determining brain death involving EEGs at widely separated intervals under defined conditions.

Misdiagnosed death

There are many anecdotal references to people being declared dead by physicians and then coming back to life, sometimes days later in their own coffin, or when embalming procedures are just about to begin. Owing to significant scientific advancements in the Victorian era, some people in Britain became obsessively worried about living after being declared dead. Premature burial was a particular possibility which concerned many; inventors therefore created methods of alerting the outside world to one's status: these included surface bells and flags connected to the coffin interior by string, and glass partitions in the coffin-lid which could be smashed by a hammer or a system of pulleys (what many failed to realize was that the pulley system would either not work because of the soil outside the coffin, or that the glass would smash in the person's face, covering them in broken glass and earth).

A first responder is not authorized to pronounce a patient dead. Some EMT training manuals specifically state that a person is not to be assumed dead unless there are clear and obvious indications that death has occurred [8]. These indications include mortal decapitation, rigor mortis (rigidity of the body), livor mortis (blood pooling in the part of the body at lowest elevation), decomposition, incineration, or other bodily damage that is clearly inconsistent with life. If there is any possibility of life and in the absence of a do not resuscitate (DNR) order, emergency workers are instructed to begin rescue and not end it until a patient has been brought to a hospital to be examined by a physician. This frequently leads to situation of a patient being pronounced dead on arrival (DOA). However, some states allow paramedics to pronounce death. This is usually based on specific criteria. Aside from the above mentioned conditions include advanced measures including CPR, intubation, IV access, and administiring medicines without regaining a pulse for at least 20 minutes.

In cases of electrocution, CPR for an hour or longer can allow stunned nerves to recover, allowing an apparently-dead person to survive. People found unconscious under icy water may survive if their faces are kept continuously cold until they arrive at an emergency room.[8] This "diving response", in which metabolic activity and oxygen requirements are minimal, is something humans share with cetaceans called the mammalian diving reflex.[8]

As medical technologies advance, ideas about when death occurs may have to be re-evaluated in light of the ability to restore a person to vitality after longer periods of apparent death (as happened when CPR and defibrillation showed that cessation of heartbeat is inadequate as a decisive indicator of death). The lack of electrical brain activity may not be enough to consider someone scientifically dead. Therefore, the concept of information theoretical death has been suggested as a better means of defining when true death actually occurs, though the concept has few practical applications outside of the field of cryonics.

There have been some scientific attempts to bring dead organisms back to life, but with limited success [1]. In science fiction scenarios where such technology is readily available, real death is distinguished from reversible death.

Causes of human death

Death can be caused by disease, accident, homicide, or suicide. The leading cause of death in developing countries is infectious disease. The leading causes of death in developed countries are atherosclerosis (heart disease and stroke), cancer, and other diseases related to obesity and aging. These conditions cause loss of homeostasis, leading to cardiac arrest, causing loss of oxygen and nutrient supply, causing irreversible deterioration of the brain and other tissues. With improved medical capability, dying has become a condition to be managed. Home deaths, once the norm, are now rare in the first world.

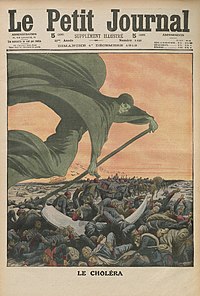

In third world countries, inferior sanitary conditions and lack of access to medical technology makes death from infectious diseases more common than in developed countries. One such disease is tuberculosis, a bacterial disease which killed 1.7 million people in 2004.[9]

Many leading first world causes of death can be postponed by diet and physical activity, but the accelerating incidence of disease with age still imposes limits on human longevity. The evolutionary cause of aging is, at best, only just beginning to be understood. It has been suggested that direct intervention in the aging process may now be the most effective intervention against major causes of death.[10]

Autopsy

An autopsy, also known as a postmortem examination or an obduction, is a medical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a human corpse to determine the cause and manner of a person's death and to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present. It is usually performed by a specialized medical doctor called a pathologist.

Autopsies are either performed for legal or medical purposes. A forensic autopsy is carried out when the cause of death may be a criminal matter, while a clinical or academic autopsy is performed to find the medical cause of death and is used in cases of unknown or uncertain death, or for research purposes. Autopsies can be further classified into cases where external examination suffices, and those where the body is dissected and an internal examination is conducted. Permission from next of kin may be required for internal autopsy in some cases. Once an internal autopsy is complete the body is reconstituted by sewing it back together. Autopsy is important in a medical environment and may shed light on mistakes and help improve practices.

A necropsy is a postmortem examination performed on a non-human animal, such as a pet.

Life extension

Life extension refers to an increase in maximum or average lifespan, especially in humans, by slowing down or reversing the processes of aging. Average lifespan is determined by vulnerability to accidents and age-related afflictions such as cancer or cardiovascular disease. Extension of average lifespan can be achieved by good diet, exercise and avoidance of hazards such as smoking and excessive eating of sugar-containing foods. Maximum lifespan is determined by the rate of aging for a species inherent in its genes. Currently, the only widely recognized method of extending maximum lifespan is calorie restriction. Theoretically, extension of maximum lifespan can be achieved by reducing the rate of aging damage, by periodic replacement of damaged tissues, or by molecular repair or rejuvenation of deteriorated cells and tissues.

Researchers of life extension are a subclass of biogerontologists known as "biomedical gerontologists". They seek to understand the nature of aging and they develop treatments to reverse aging processes or to at least slow them down, for the improvement of health and the maintenance of youthful vigor at every stage of life. Those who take advantage of life extension findings and seek to apply them upon themselves are called "life extensionists" or "longevists". The primary life extension strategy currently is to apply available anti-aging methods in the hope of living long enough to benefit from a complete cure to aging once it is developed, which given the rapidly advancing state of biogenetic and general medical technology, could conceivably occur within the lifetimes of people living today.

Many biomedical gerontologists and life extensionists believe that future breakthroughs in tissue rejuvenation with stem cells, organs replacement (with artificial organs or xenotransplantations) and molecular repair will eliminate all aging and disease as well as allow for complete rejuvenation to a youthful condition. Whether such breakthroughs can occur within the next few decades is impossible to predict. Some life extensionists arrange to be cryonically preserved upon legal death so that they can await the time when future medicine can eliminate disease, rejuvenate them to a lasting youthful condition and repair damage caused by the cryonics process. Whether the maximum human lifespan should be extended is the subject of much ethical debate amongst politicians and scientists.

The physician's perspective

A qualitative survey of internal medicine doctors in the United States found three sources of satisfaction from medical practice:

- realizing a fundamental change in perspective via an experience with a patient

- making a difference made in someone's life

- connecting with patients

The authors of the survey noted how often the meaningful events, such as connecting with patients, occurred at events, such as death, that normally suggest a failure of medical care [11]. The following research suggests factors associated with a meaningful death.

A qualitative study using focus groups that consisted of "physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, hospice volunteers, patients, and recently bereaved family members". The groups identified the following themes associated with a 'good death'[12]. The article is freely available and provides much more detail.

- Pain and Symptom Management. Patients want reassurance that symptoms, such as pain or shortness of breath that may occur at death, will be well treated.

- Clear Decision Making. According to the study, 'participants stated that fear of pain and inadequate symptom management could be reduced through communication and clear decision making with physicians. Patients felt empowered by participating in treatment decisions'.

- Preparation for Death. Patients wanted to know what to expect near death and to be able to plan for the events that would follow death.

- Completion. 'Completion includes not only faith issues but also life review, resolving conflicts, spending time with family and friends, and saying good-bye.'

- Contributing to Others. A family member noted, "I guess it was really poignant for me when a nurse or new resident came into his room, and the first thing he'd say would be, ‘Take care of your wife’ or ‘Take care of your husband. Spend time with your children.’ He wanted to make sure he imparted that there's a purpose for life."

- Affirmation of the Whole Person. 'They didn't come in and say, "I'm Doctor so and so." There wasn't any kind of separation or aloofness. They would sit right on his bed, hold his hand, talk about their families, his family, golf, and sports.'

- Distinctions in Perspectives of a Good Death

In an essay, 'On Saying Goodbye: Acknowledging the End of the Patient–Physician Relationship with Patients Who Are Near Death' suggestions are made to health care providers for saying good-bye to patients near death. [13]. The quotes below are from the article. The article is freely available and provides much more detail.

- Choose an Appropriate Time and Place

- Acknowledge the End of Your Routine Contact and the Uncertainty about Future Contact The doctor could say, "You know, I'm not sure if we will see each other again in person, so while we are with each other now I want to say something about our relationship."

- Invite the Patient To Respond, and Use That Response as a Piece of Data about the Patient's State of Mind The authors suggest saying "Would that be okay?" or "how would you feel about that?"

- Frame the Goodbye as an Appreciation The authors suggest examples such as "I just wanted to say how much I've enjoyed you and how much I've appreciated your flexibility [or cooperation, good spirits, courage, honesty, directness, collaboration] and your good humor [or your insights, thoughtfulness, love for your family]."

- Give Space for the Patient to Reciprocate, and Respond Empathically to the Patient's Emotion If the patients becomes tearful, the doctor can provide silence to allow the patient to respond, or the doctor may ask about what the patient is feeling.

- Articulate an Ongoing Commitment to the Patient's Care Do not make the patient feel abandoned, "Of course you know I remain available to you and that you can still call me".

- Later, Reflect on Your Work with This Patient

A randomized controlled trial of communication between health care providers and family members at the time of death reported that the intervention decreased the burden of bereavement[14]. The intervention consisted of a brochure and family conference that focused on the following items that are remembered with the mnemonic value:

- to Value and appreciate what the family members said

- to Acknowledge the family members' emotions

- to Listen

- to ask questions that would allow the caregiver to Understand who the patient was as a person

- to Elicit questions from the family members. Each investigator received a detailed description of the conference procedure

Other difficult issues for physicians include providing sedation for a patient at death and discontinuing life support. The following case reports detail these experiences from the physician's perspective [15] [16].

Death in culture

It has been suggested that this article should be split into a new article titled Death in culture. (discuss) |

Settlement of dead bodies

In most cultures, before the onset of significant decay, the body undergoes some type of ritual disposal, usually either cremation or internment in a tomb. Cremation is a very old and quite common custom, if one takes into account the sheer numbers of next of kin (of dead) practicing it. The act of cremation exemplifies the belief of the concept of "ashes to ashes". The other modes of disposal include interment in a grave, but may also be a sarcophagus, crypt, sepulchre, or ossuary, a mound or barrow, or a monumental surface structure such as a mausoleum (exemplified by the Taj Mahal) or a pyramid (as exemplified by the Great Pyramid of Giza).

In Tibet, one method of corpse disposal is sky burial, which involves placing the body of the deceased on high ground (a mountain) and leaving it for birds of prey to dispose of. Sometimes this is because in some religious views, birds of prey are carriers of the soul to the heavens, but at other times this simply reflects the fact that when terrain (as in Tibet) makes the ground too hard to dig, there are few trees around to burn and the local religion (Buddhism) believes that the body after death is only an empty shell, there are more practical ways of disposing of a body, such as leaving it for animals to consume.

In certain cultures, efforts are made to retard the decay processes before burial (resulting even in the retardation of decay processes after the burial), as in mummification or embalming. This happens during or after a funeral ceremony. Many funeral customs exist in different cultures. In some fishing or naval communities, the body is sent into the water, in what is known as burial at sea. Several mountain villages have a tradition of hanging the coffin in woods.

A new alternative is ecological burial. This is a sequence of deep-freezing, pulverisation by vibration, freeze-drying, removing metals, and burying the resulting powder, which has 30% of the body mass.

Cryonics is the process of cryopreservating of a body to liquid nitrogen temperature to stop the natural decay processes that occur after death. Those practicing cryonics hope that future technology will allow the legally deceased person to be restored to life when and if science is able to cure all disease, rejuvenate people to a youthful condition and repair damage from the cryopreservation process itself. As of 2007, there were over 150 people in some form of cryopreservation at one of the two largest cryonics organizations, Alcor Life Extension Foundation and the Cryonics Institute.

Space burial uses a rocket to launch the cremated remains of a body into orbit. This has been done at least 150 times.

Graves are usually grouped together in a plot of land called a cemetery or graveyard, and burials can be arranged by a funeral home, mortuary, undertaker or by a religious body such as a church or (for some Jews) the community's burial society, a charitable or voluntary body charged with these duties.

Whole body donations, made by the donor while living (or by a family member in some cases), are an important source of human cadavers used in medical education and similar training, and in research. In the United States, these gifts, along with organ donations, are governed by the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act. In addition to wishing to benefit others, individuals might choose to donate their bodies to avoid the cost of funeral arrangements; however, willed body programs often encourage families to make alternative arrangements for burial if the body is not accepted.

Grief and mourning

Grief is a multi-faceted response to loss. Although conventionally focused on the emotional response to loss, it also has a physical, cognitive, behavioural, social and philosophical dimensions. Common to human experience is the death of a loved one, be they friend, family, or other. While the terms are often used interchangeably, bereavement often refers to the state of loss, and grief to the reaction to loss. Response to loss is varied and researchers have moved away from conventional views of grief (that is, that people move through an orderly and predictable series of responses to loss) to one that considers the wide variety of responses that are influenced by personality, family, culture, and spiritual and religious beliefs and practices.

Bereavement, while a normal part of life for most people, carries a degree of risk when limited support is available. Severe reactions to loss may carry over into familial relations and cause trauma for children, spouses and any other family members. Many forms of what are termed 'mental illness' have loss as their root, but covered by many years and circumstances this often goes unnoticed. Issues of personal faith and beliefs may also face challenge, as bereaved persons reassess personal definitions in the face of great pain. While many who grieve are able to work through their loss independently, accessing additional support from bereavement professionals may promote the process of healing. Individual counseling, professional support groups or educational classes, and peer-lead support groups are primary resources available to the bereaved. In some regions local hospice agencies may be an important first contact for those seeking bereavement support.

Mourning is the process of and practices surrounding death related grief. The word is also used to describe a cultural complex of behaviours in which the bereaved participate or are expected to participate. Customs vary between different cultures and evolve over time, though many core behaviors remain constant. Wearing dark, sombre clothes is one practice followed in many countries, though other forms of dress are also seen. Those most affected by the loss of a loved one often observe a period of grieving, marked by withdrawal from social events and quiet, respectful behavior. People may also follow certain religious traditions for such occasions.

Mourning may also apply to the death of, or anniversary of the passing of, an important individual like a local leader, monarch, religious figure etc. State mourning may occur on such an occasion. In recent years some traditions have given way to less strict practices, though many customs and traditions continue to be followed.

Animal loss

Animal loss is the loss of a pet or a non-human animal to which one has become emotionally bonded. Though sometimes trivialized by those who have not experienced it themselves, it can be an intense loss, comparable with the death of a loved one.

Settlement of legal entity

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Aside from the physical disposition of the corpse, the legal entity of a person must be settled. This includes attributes such as assets and debts. Depending on the jurisdiction, laws or a will may determine the final disposition of the estate. A legal process, or probate, will guide these proceedings.

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the execution of a convicted criminal by the state as punishment for crimes known as capital crimes or capital offences. Historically, the execution of criminals and political opponents was used by nearly all societies—both to punish crime and to suppress political dissent. Among democratic countries around the world, all European (except Belarus) and Latin American states, many Pacific Area states (including Australia, New Zealand and Timor Leste), and Canada have abolished capital punishment, while the United States, Guatemala, and most of the Caribbean as well as some democracies in Asia (e.g., Japan and India) and Africa (e.g., Botswana and Zambia) retain it. Among nondemocratic countries, the use of the death penalty is common but not universal.

In most places that practice capital punishment today, the death penalty is reserved as punishment for premeditated murder, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries, sexual crimes, such as adultery and sodomy, carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as apostasy, the formal renunciation of one's religion. In many retentionist countries, drug trafficking is also a capital offense. In China human trafficking and serious cases of corruption are also punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.[17]

Capital punishment is a very contentious issue. Supporters of capital punishment argue that it deters crime, prevents recidivism, and is an appropriate form of punishment for the crime of murder. Opponents of capital punishment argue that it does not deter criminals more than life imprisonment, violates human rights, leads to executions of some who are wrongfully convicted, and discriminates against minorities and the poor.

Warfare

War is a prolonged state of violent, large scale conflict involving two or more groups of people. When and how war originated is a highly controversial topic. Some think war has existed as long as humans, while others believe it began only about 5000 years ago with the rise of the first states; afterward war "spread to peaceful hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists."[18]

Often opposing leaders or governing bodies get other people to fight for them, even if those fighting have no vested interest in the issues fought over. In time it became practical for some people to have warfare as their sole occupation, either as a member of a military force or mercenary. The original cause of war is not always known. Wars may be prosecuted simultaneously in one or more different theatres. Within each theatre, there may be one or more consecutive military campaigns. Individual actions of war within a specific campaign are traditionally called battles, although this terminology is not always applied to contentions in modernity involving aircraft, missiles or bombs alone in the absence of ground troops or naval forces.

The factors leading to war are often complicated and due to a range of issues. Where disputes arise over issues such as sovereignty, territory, resources, ideology and a peaceable resolution is not sought, fails, or is thwarted, war often results.

A war may begin following an official declaration of war in the case of international war, although this has not always been observed either historically or currently. Civil wars and revolutions are not usually initiated by a formal declaration of war, but sometimes a statement about the purposes of the fighting is made. Such statements may be interpreted to be declarations of war, or at least a willingness to fight for a cause.

Military suicide

A suicide attack occurs when an individual or group violently sacrifice their own lives for the benefit of their side. In the desperate final days of World War II, many Japanese pilots volunteered for kamikaze missions in an attempt to forestall defeat for the Empire. In Nazi Germany, Luftwaffe squadrons were formed to smash into American B-17s during daylight bombing missions, in order to delay the highly-probable Allied victory, although in this case, inspiration was primarily the Soviet and Polish taran ramming attacks, and death of the pilot was not a desired outcome. The degree to which such a pilot was engaging in a heroic, selfless action or whether they faced immense social pressure is a matter of historical debate. The Japanese also built one-man "human torpedo" suicide submarines.

However, suicide has been fairly common in warfare throughout history. Soldiers and civilians committed suicide to avoid capture and slavery (including the wave of German and Japanese suicides in the last days of World War II). Commanders committed suicide rather than accept defeat. Spies and officers have committed suicide to avoid revealing secrets under interrogation and/or torture. Behaviour that could be seen as suicidal occurred often in battle. Japanese infantrymen usually fought to the last man, launched "banzai" suicide charges, and committed suicide during the Pacific island battles in World War II. In Saipan and Okinawa, civilians joined in the suicides. Suicidal attacks by pilots were common in the 20th century: the attack by U.S. torpedo planes at the Battle of Midway was very similar to a kamikaze attack.

Martyrdom

A martyr is a person who is put to death or endures suffering for their beliefs, principles or ideology. The death of a martyr or the value attributed to it is called martyrdom. In different belief systems, the criteria for being considered a martyr is different. In the Christian context, a martyr is an innocent person who, without seeking death, is murdered or put to death for his or her religious faith or convictions. An example is the persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire. Christian martyrs sometimes decline to defend themselves at all, in what they see as an imitation of Jesus' willing sacrifice.

Islam accepts a broader view of what constitutes a martyr, including anyone who dies in the struggle between those lands under Muslim government and those areas outside Muslim rule. Generally, some seek to include suicide bombers as a "martyr" of Islam, however, this is widely disputed in mainstream Islamic thought, which argues that a martyr may not commit suicide.

Though often religious in nature, martyrdom can be applied to a secular context as well. The term is sometimes applied to those who die or are otherwise severely affected in support of a cause, such as soldiers fighting in a war, doctors fighting an epidemic, or people leading civil rights movements. Proclaiming martyrdom is a common way to draw attention to a cause and garner support.

Suicide

Suicide is the willful act of taking one's own life, and may be caused by psychological factors such as the difficulty of coping with depression or other mental disorders. It may also stem from social and cultural pressures.

Nearly a million people worldwide commit suicide annually. While completed suicides are higher in men, women have higher rates for suicide attempts. Elderly males have the highest suicide rate, although rates for young adults have been increasing in recent years.[19]

Views toward suicide have varied in history and society. Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism generally condemn suicide as a dishonorable act and some countries have made it a crime to attempt to kill oneself. In some cultures committing suicide may be accepted under some circumstances, such as Japanese committing seppuku for honor, Islamic suicide attacks, or the self-immolation of Buddhist monks as a form of protest.

Euthanasia

Euthanasia is the practice of terminating the life of a person or animal in a painless or minimally painful way in order to prevent suffering or other undesired conditions in life. This may be voluntary or involuntary, and carried out with or without a physician. In a medical environment, it is normally carried out by oral, intravenous or intramuscular drug administration.

Laws around the world vary greatly with regard to euthanasia and are subject to change as people's values shift and better palliative care or treatments become available. It is legal in some nations, while in others it may be criminalized. Due to the gravity of the issue, strict restrictions and proceedings are enforced regardless of legal status. Euthanasia is a controversial issue because of conflicting moral feelings both within a person's own beliefs and between different cultures, ethnicities, religions and other groups. The subject is explored by the mass media, authors, film makers and philosophers, and is the source of ongoing debate and emotion.

Customs and superstitions

Death's finality and the relative lack of firm scientific understanding of its processes for most of human history have led to many different traditions and cultural rituals for dealing with death.

Sacrifices

Sacrifice ("to make sacred") includes the practice of offering the lives of animals or people to the gods, as an act of propitiation or worship. The practice of sacrifice is found in the oldest human records, and the archaeological record finds corpses, both animal and human, that show marks of having been sacrificed and have been dated to long before any records. Human sacrifice was practiced in many ancient cultures. The practice has varied between different civilizations, with some like the Aztecs being notorious for their ritual killings, while others have looked down on the practice. Victims ranging from prisoners to infants to virgins were killed to please their gods, suffering such fates as burning, beheading and being buried alive.

Animal sacrifice is the ritual killing of an animal as practised by many religions as a means of appeasing a god or spiritual being, changing the course of nature or divining the future. Animal sacrifice has occurred in almost all cultures, from the Hebrews to the Greeks and Romans to the Yoruba. Over time human and animal sacrifices have become less common in the world, such that modern sacrifices are rare. Most religions condemn the practice of human sacrifices, and present day laws generally treat them as a criminal matter. Nonetheless traditional sacrifice rituals are still seen in less developed areas of the world where traditional beliefs and superstitions linger, including the sacrifice of human beings.

Religion and mythology

Faith in some form of afterlife is an important aspect of many people's beliefs. Such beliefs are usually manifested as part of a religion, as they pertain to phenomena beyond the ordinary experience of the natural world. For example, one aspect of Hinduism involves belief in a continuing cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth (Samsara) and the liberation from the cycle (Moksha). Though various evidence has been advanced in attempts to demonstrate the reality of an afterlife, these claims have never been validated. For this reason, the material or metaphysical existence of an afterlife remains a matter of faith more than a matter of science.

Many cultures have incorporated a god of death into their mythology or religion. As death, along with birth, is among the major parts of human life, these deities may often be one of the most important deities of a religion. In some religions with a single powerful deity as the source of worship, the death deity is an antagonistic deity against which the primary deity struggles.

In polytheistic religions or mythologies which have a complex system of deities governing various natural phenomena and aspects of human life, it is common to have a deity who is assigned the function of presiding over death. The inclusion of such a "departmental" deity of death in a religion's pantheon is not necessarily the same as the glorification of death which is commonly condemned by the use of the term "death-worship" in modern political rhetoric.

In the theology of monotheistic religion, the one god governs both life and death. However in practice this manifests in different rituals and traditions and varies according to a number of factors including geography, politics, traditions and the influence of other religions.

Personification of death

Death has been personified as a figure or fictional character in mythology and popular culture since the earliest days of storytelling. Because the reality of death has had a substantial influence on the human psyche and the development of civilization as a whole, the personification of Death as a living, sentient entity is a concept that has existed in many societies since the beginning of recorded history. In western culture, death is usually shown as a skeletal figure carrying a large scythe, and sometimes wearing a midnight black gown with a hood.

Examples of death personified are:

- In modern-day European-based folklore, Death is known as the "Grim Reaper" or "The grim spectre of death". This form typically wields a scythe, and is sometimes portrayed riding a white horse.

- In the Middle Ages, Death was imagined as a decaying or mummified human corpse, later becoming the familiar skeleton in a robe.

- Death is sometimes portrayed in fiction and occultism as Azrael, the angel of death (note that the name "Azrael" does not appear in any versions of either the Bible or the Qur'an).

- Father Time is sometimes said to be Death.

- A psychopomp is a spirit, deity, or other being whose task is to conduct the souls of the recently dead into the afterlife.

The number 4 in East Asia

In China, Japan, and Korea the number 4 is often associated with death because the sound of the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean words for four and death are similar (for example, the sound sì in Chinese is the Sino-Korean number 4 (四), whereas sǐ is the word for death (死). For this reason, hospitals and hotels often omit the 4th, 14th, 24th, floors (etc.), or substitute the number '4' with the letter 'F'. Koreans are buried under a mound standing vertical in coffins made from six planks of wood. Four of the planks represent their respective four cardinal points of the compass, while a fifth represents sky and the sixth represents earth. This relates back to the importance that the Confucian society placed upon the four cardinal points having mystical powers.

Glorification of and fascination with death

Whether because of its very poetic nature or because of the great mystery it presents, or both, death is and has very often been glorified in many cultures through many different means. War, crime, revenge, martyrdom, suicide and many other forms of violence involving death are often glorified by different media, often in modern times being glorified even in spite of the attempts at depicting death meant to be de-glorifying. For example, film critic Roger Ebert mentions in a number of articles that Francis Truffaut makes the claim it's impossible to make an anti-war film, as any depiction of war ends up glorifying it. The most prevalent and permanent form of death's glorification is through artistic expression. Through song, such as Knockin' on Heaven's Door or Bullet in the Head, many artists show death through poetic analogy or even as a poetic analogy, as in the latter mentioned song. Events such as The Charge of the Light Brigade and The Battle of the Alamo have served as inspirations for artistic depictions of and myths regarding death.

Perception of glory in death is subjective and can even differ wildly from one member of a group to another. Religion plays a key role, especially in terms of expectations of an afterlife. Personal and perceptions about mode of death are also important factors. One person's martyr could be another person's waste of life.

See also

|

References

- ^ a b Kastenbaum, Robert (2006). "Definitions of Death". Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

- ^ DeBano, L.F., D.G. Neary, P.F. Ffolliot (1998) Fire’s Effects on Ecosystems. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, New York, USA.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1999). "Up to the Starting Line". Guns, Germs, and Steel. W. W. Norton. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-393-31755-2.

- ^ a b Newman, Mark. "A Mathematical Model for Mass Extinction". Cornell University. May 20 1994. URL accessed July 30 2006.

- ^ Raup, David M. Extinction: Bad Genes or Bad Luck? W.W. Norton and Company. New York. 1991. pp.3-6 ISBN 978-0393309270

- ^ Species disappearing at an alarming rate, report says. MSNBC. URL accessed July 26 2006.

- ^ Wilson, E.O., The Future of Life (2002) (ISBN 0-679-76811-4). See also: Leakey, Richard. The Sixth Extinction : Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind ( ISBN 0-385-46809-1 ).

- ^ a b c Limmer, D. et al. (2006). Emergency care (AHA update, Ed. 10e). Prentice Hall.

- ^ World Health Organization (WHO). Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104 - Global and regional incidence. March 2006, Retrieved on 6 October 2006.

- ^ SJ Olshanksy; et al. (2006). "Longevity dividend : What should we be doing to prepare for the unprecedented aging of humanity?". The Scientist. 20. Scientist (The), Philadelphia: 28–36. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ Horowitz C, Suchman A, Branch W, Frankel R (2003). "What do doctors find meaningful about their work?". Ann Intern Med. 138 (9): 772–5. PMID 12729445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Steinhauser K, Clipp E, McNeilly M, Christakis N, McIntyre L, Tulsky J (2000). "In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers". Ann Intern Med. 132 (10): 825–32. PMID 10819707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Back A, Arnold R, Tulsky J, Baile W, Fryer-Edwards K (2005). "On saying goodbye: acknowledging the end of the patient-physician relationship with patients who are near death". Ann Intern Med. 142 (8): 682–5. PMID 15838086.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007 Feb 1;356(5):469-78. PMID 17267907

- ^ Edwards M, Tolle S (1992). "Disconnecting a ventilator at the request of a patient who knows he will then die: the doctor's anguish". Ann Intern Med. 117 (3): 254–6. PMID 1616221.

- ^ Petty T (2000). "Technology transfer and continuity of care by a "consultant"". Ann Intern Med. 132 (7): 587–8. PMID 10744597.

- ^ "Shot at Dawn, campaign for pardons for British and Commonwealth soldiers executed in World War I". Shot at Dawn Pardons Campaign. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Otterbein, Keith, 2004, How War Began. Texas A&M University Press.

- ^ "How can suicide be prevented?". 2005-09-09. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

Additional references:

- Pounder, Derrick J. (2005-12-15). "POSTMORTEM CHANGES AND TIME OF DEATH" (PDF). University of Dundee. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Vass AA (2001) Microbiology Today 28: 190-192 at: [2]

- Piepenbrink H (1985) J Archaeolog Sci 13: 417-430

- Piepenbrink H (1989) Applied Geochem 4: 273-280

- Child AM (1995) J Archaeolog Sci 22: 165-174

- Hedges REM & Millard AR (1995) J Archaeolog Sci 22: 155-164

- Cook, C (2006). Death in Ancient China: The Tale of One Man's Journey. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9004153128.

- Maloney, George, A., S.J. (1980) The Everlasting Now: Meditations on the mysteries of life and death as they touch us in our daily lives. ISBN 0877932018

External links

- Death (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- Freeview Video 'Defying Death' by the Vega Science Trust and the BBC/OU (RealMedia)

- Odds of dying from various injuries or accidents Source: National Safety Council, United States, 2001

- Causes of Death

- Death FAQ

- Causes of Death 1916 How the medical profession categorized causes of death a century ago.

- George Wald: The Origin of Death A biologist explains life and death in different kinds of organisms in relation to evolution.

- Death and Dying Online Informational site about death and dying.

Religious views

- Death & Dying in Islam Muslim attitudes towards death

- Dying, Yamaraja and Yamadutas + terminal restlessness (Vedic/Hindu view)

- The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning By Maurice Lamm

- Christian Beliefs In The Afterlife Christian beliefs on death and the afterlife.