Persian Empire (dynasty)

This article possibly contains original research. (April 2009) |

Template:FixHTML Template:FixHTML

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

It has been suggested that this article should be split into articles titled Achaemenid Empire, Sassanid Empire, History of Persia and Persia (disambiguation). (discuss) (August 2009) |

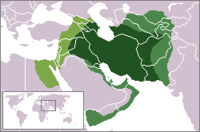

The Persian Empire was a series of successive Iranian or Iraniate empires that ruled over the Iranian plateau, the original Persian homeland, and beyond in Western Asia, South Asia, Central Asia and the Caucasus.[1]

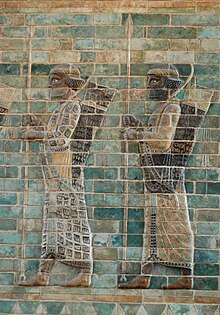

The first Persian Empire formed under the Achaemenid dynasty (550–330 BC). The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 BC) was the largest empire of the ancient world and it reached its greatest extent under Darius the Great and Xerxes the Great — famous in antiquity as the foe of the classical Greek states (See Greco-Persian Wars). It was a united Persian kingdom that originated in the region now known as Pars province (Fars province) of Iran.

It was formed under Cyrus the Great, who took over the empire of the Medes, and conquered much of the Middle East, including the territories of the Babylonians, Assyrians, the Phoenicians, and the Lydians. Cambyses, Son of Cyrus the Great, continued his conquests by conquering Egypt. The Achaemenid Persian Empire was ended during the Wars of Alexander the Great. For the next 550 years, most of Iran was ruled first by the descendants of Alexander's Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, who founded the Seleucid dynasty, and then by the Parthian Arsacid Dynasty.

The Sassanid dynasty, which replaced the Arsacids in 226 AD, arose from the same region as the Achaemenids, and restored the conception of a Persian Empire. They ruled until the Arab conquest in the mid 7th century. After the Abbasid dynasty took power in the mid-8th century and moved their capital to Baghdad, in Mesopotamia on the Tigris river near the old Sassanid capital of Ctesiphon, the Islamic Caliphate gradually became Persianized. When the Abbasid dynasty began to break up in the late 9th century, regional Iranian dynasties arose, many of them claiming a connection to the Sassanids and professing ambitions to restore the old Persian Empire.

Later Islamic dynasties in Iran, whether of Iranian, Turkic, or Mongol origins, also sought to claim ties to the ancient Persian Empire. In the sixteenth century, the Safavid dynasty took power in Iran, and, after a period of division, reunified the country under their rule. While the country they ruled was most commonly known as simply "Persia" in the west, the term "Persian Empire," by analogy with the ancient dynasties that ruled over the same territory, was occasionally used.

History

Median Empire (728 BC-559 BC)

Median Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 728 BC–559 BC | |||||||||

Median Empire, ca. 600 BC | |||||||||

| Capital | Ecbatana | ||||||||

| Religion | Zoroastrianism, possibly also Proto-Indo-Iranian religion | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity | ||||||||

• Deioces | 728 BC | ||||||||

• Cyrus the Great | 559 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Medes are credited with the foundation of the first Iranian empire, the largest of its day until Cyrus the Great established a unified Iranian empire of the Medes and Persians, often referred to as the Achaemenid Persian Empire, by defeating his grandfather and overlord, Astyages the shah of Media. The Median capital was Ecbatana, the modern day Iranian city of Hamedan. Ectbatana was preserved as one of the capital cities of the Achaemenid Empire, which succeeded the Median Empire.

According to Herodotus, the conquests of Cyaxares the Mede were preceded by a Scythian invasion and domination lasting twenty-eight years (under Madius the Scythian, 653-625 BC). The Mede tribes seem to have come into immediate conflict with a settled state to the West known as Mannae, allied with Assyria. Assyrian inscriptions state that the early Mede rulers, who had attempted rebellions against the Assyrians in the time of Esarhaddon and Assur-bani-pal, were allied with chieftains of the Ashguza (Scythians) and other tribes - who had come from the northern shore of the Black Sea and invaded Armenia and Asia Minor; and Jeremiah and Zephaniah in the Old Testament agree with Herodotus that a massive invasion of Syria and Philistia by northern barbarians took place in 626 BC. The state of Mannae was finally conquered and assimilated by the Medes in the year 616 BC.

In 612 BC, Cyaxares conquered Urartu, and with the alliance of Nabopolassar the Chaldean, succeeded in destroying the Assyrian capital, Nineveh; and by 606 BC, the remaining vestiges of Assyrian control. From then on, the Mede king ruled over much of Iran, Assyria and northern Mesopotamia, Armenia and Cappadocia. His power was very dangerous to his neighbors, and the exiled Jews expected the destruction of Babylonia by the Medes (Isaiah 13, 14m 21; Jerem. 1, 51.).

When Cyaxares attacked Lydia, the kings of Cilicia and Babylon intervened and negotiated a peace in 585 BC, whereby the Halys was established as the Medes' frontier with Lydia. Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon married a daughter of Cyaxares, and an equilibrium of the great powers was maintained until the rise of the Persians under Cyrus.

Median Kings were:

- Deioces (Old Iranian *Dahyu-ka) 727-675 B.C.[2]

- Phraortes (Old Iranian *Fravarti) 674-653

- Madius (Scythian Rule) 652-625

- Cyaxares (Old Iranian *Uvaxštra) 624-585[3]

- Astyages (Old Iranian *Ršti-vêga) 589-549[3]

Modern research by a professor of Assyriology, Robert Rollinger, has questioned the Median empire and its sphere of influence, proposing for example that it did not control the Assyrian heartland.[4] -->

The Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BC)

The earliest known record of the Persians comes from an Assyrian inscription from c. 844 BC that calls them the Parsu (Parsuaš, Parsumaš)[5] and mentions them in the region of Lake Urmia alongside another group, the Mādāyu (Medes).[6] For the next two centuries, the Persians and Medes were at times tributary to the Assyrians. The region of Parsuash was annexed by Sargon of Assyria around 719 BC. Eventually the Medes came to rule an independent Median Empire, and the Persians were subject to them.

The Achaemenids were the first to create a centralized state in Persia, founded by Achaemenes (Haxamaniš), chieftain of the Persians around 700 BC.

Around 653 BC, the Medes came under the domination of the Scythians, and Teispes (Cišpiš), the son of Achaemenes, seems to have led the nomadic Persians to settle in southern Iran around this time — eventually establishing the first organized Persian state in the important region of Anšan as the Elamite kingdom was permanently destroyed by the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal (640 BC). The kingdom of Anšan and its successors continued to use Elamite as an official language for quite some time after this, although the new dynasts spoke Persian, an Indo-Iranian tongue.

Teispes' descendants may have branched off into two lines, one line ruling in Anshan, while the other ruled the rest of Persia. Cyrus II the Great (Kuruš) united the separate kingdoms around 559 BC. At this time, the Persians were still tributary to the Median Empire ruled by Astyages. Cyrus rallied the Persians together, and in 550 BC defeated the forces of Astyages, who was then captured by his own nobles and turned over to the triumphant Cyrus, now Shah of a unified Persian kingdom. As Persia assumed control over the rest of Media and their large empire, Cyrus led the united Medes and Persians to still more conquest. He took Lydia in Asia Minor, and carried his arms eastward into central Asia. Finally in 539 BC, Cyrus marched triumphantly into the ancient city of Babylon. After this victory, he issued the declaration recorded in the Cyrus cylinder, which portrayed him as a benevolent conqueror welcomed by the local inhabitants and their gods.[7] Cyrus was killed in 530 BC during a battle against the Massagetae or Sakas.

Cyrus's son, Cambyses II (Kambūjiya), annexed Egypt to the Achaemenid Empire. The empire then reached its greatest extent under Darius I (Dāryavuš). He led conquering armies into the Indus River valley and into Thrace in Europe. A punitive raid against Greece was halted at the Battle of Marathon. A larger invasion by his son, Xerxes I (Xšayārša), would have initial success at the Battle of Thermopylae. Following the destruction of his navy at the Battle of Salamis, Xerxes would withdraw most of his forces from Greece. The remnant of his army in Greece commanded by General Mardonius was ultimately defeated at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC.

Darius improved the famous Royal Road and other ancient trade routes, thereby connecting far reaches of the empire. He may have moved the administration center from Fars itself to Susa, near Babylon and closer to the center of the realm. The Persians allowed local cultures to survive, following the precedent set by Cyrus the Great. This was not only good for the empire's subjects, but ultimately benefited the Achaemenids, because the conquered peoples felt no need to revolt.

It may have been during the Achaemenid period that Zoroastrianism reached South-Western Iran, where it came to be accepted by the rulers and through them became a defining element of Persian culture. The religion was not only accompanied by a formalization of the concepts and divinities of the traditional (Indo-)Iranian pantheon, but also introduced several novel ideas, including that of free will, which is arguably Zoroaster's greatest contribution to religious philosophy. Under the patronage of the Achaemenid kings, and later as the de-facto religion of the state, Zoroastrianism would reach all corners of the empire. In turn, Zoroastrianism would be subject to the first syncretic influences, in particular from the Semitic lands to the west, from which the divinities of the religion would gain astral and planetary aspects and from where the temple cult originates. It was also during the Achaemenid era that the sacerdotal Magi would exert their influence on the religion, introducing many of the practices that are today identified as typically Zoroastrian, but also introducing doctrinal modifications that are today considered to be revocations of the original teachings of the prophet.

The Achaemenid Empire united people and kingdoms from every major civilization in south West Asia and North East Africa. It was overthrown during the Wars of Alexander the Great.

The Parthian Empire (250 BC–AD 226)

The Parthian Empire or Arsacid Empire (Persian: اشکانیان),is the name used for the third imperial Iranian dynasty (250 BCE - 226 CE).The Parthian dynasty was founded by Arsaces I(Persian: اشک Ashk) and ended when the last parthian Shahanshah (King of Kings), Artabanus IV defeated by Ardashir I who later founded The Sassanid Empire.

Its rulers, the Arsacid dynasty, belonged to an Iranian tribe that had settled there during the time of Alexander. They declared their independence from the Seleucids in 238 BC, but their attempts to unify Iran were thwarted until after the advent of Mithridates I to the Parthian throne in about 170 BC.

The Parthian Confederacy shared a border with Rome along the upper Euphrates River. The two polities became major rivals, especially over control of Armenia. Heavily-armoured Parthian cavalry (cataphracts) supported by mounted archers proved a match for Roman legions, as in the Battle of Carrhae in which the Parthian General Surena defeated Marcus Licinius Crassus of Rome. Wars were very frequent, with Mesopotamia serving as the battleground.

During the Parthian period, Hellenistic customs partially gave way to a resurgence of Iranian culture. However, the area lacked political unity, and the vassalary structure that the Arsacids had adopted from the Seleucids left the Parthians in a constant state of war with one seceding vassal or the other. By the 1st century BC, Parthia was decentralized, ruled by feudal nobles. Wars with Romans to the west and the Kushan Empire to the northeast drained the country's resources.

Parthia, now impoverished and without any hope of recovering its lost territories, was demoralized. The kings had to give more concessions to the nobility, and the vassal kings sometimes refused to obey. Parthia's last ruler Artabanus IV had an initial success in putting together the crumbling state. However, the fate of the Arsacid Dynasty was doomed when in AD 224, the Persian vassal king Ardashir revolted. Two years later, he took Ctesiphon, and this time, it meant the end of Parthia. It also meant the beginning of the second Persian Empire, ruled by the Sassanid kings. Sassanids were from the province of Persis, native to the first Persian Empire, the Achaemenids.

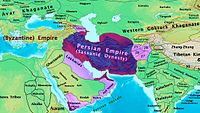

The Sassanid Empire (226–651)

The Sassanid Empire or Sassanian Dynasty (Persian: ساسانیان) is the name used for the fourth imperial Iranian dynasty, and the second Persian Empire (226–651). The Sassanid dynasty was founded by Ardashir I (Persian: اردشیر یکم) after defeating the last Parthian (Arsacid) king, Artabanus V (Persian: اردوان پنجم Ardavan) and ended when the last Sassanid Shahanshah (King of Kings), Yazdegerd III (632–651), lost a 14-year struggle to drive out the early Islamic Caliphate, the first of the Islamic empires.

Ardashir I led a rebellion against the Parthian Confederacy in an attempt to revive the glory of the previous empire and to legitimize the Hellenized form of Zoroastrianism practised in southwestern Iran. In two years he was the Shah of a new Persian Empire.

The Sassanid dynasty (also Sassanian, named for Ardashir's grandfather) was the first dynasty native to the Pars province since the Achaemenids; thus they saw themselves as the successors of Darius and Cyrus. They pursued an aggressive expansionist policy. They recovered much of the eastern lands that the Kushans had taken in the Parthian period. The Sassanids continued to make war against Rome; a Persian army even captured the Roman Emperor Valerian in 260.

The Sassanid Empire, unlike Parthia, was a highly centralized state. The people were rigidly organized into a caste system: Priests, Soldiers, Scribes, and Commoners. Zoroastrianism was finally made the official state religion, and spread outside Persia proper and out into the provinces. There was sporadic persecution of other religions. The Eastern Orthodox Church was particularly persecuted, but this was in part due to its ties to the Roman Empire. The Nestorian Christian church was tolerated and sometimes even favored by the Sassanids.

The wars and religious control that had fueled the Sassanid Empire's early successes eventually contributed to its decline. The eastern regions were conquered by the White Huns in the late 5th century. Adherents of a radical religious sect, the Mazdakites, revolted around the same time. Khosrau I was able to recover his empire and expand into the Christian countries of Antioch and Yemen. Between 605 and 629, Sassanids successfully annexed Levant and Roman Egypt and pushed into Anatolia.

However, a subsequent war with the Romans utterly destroyed the empire. In the course of the protracted conflict, Sassinid armies reached Constantinople, but could not defeat the Byzantines there. Meanwhile, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius had successfully outflanked the Persian armies in Asia Minor and attacked the empire from the rear while the main Iranian army along with its top Eran Spahbods were far from battlefields. This resulted in a crushing defeat for the Sassanids in Northern Mesopotamia. The Sassanids had to give up all their conquered lands and retreat.

Following the advent of Islam and collapse of the Sassanid Empire, Persians came under the subjection of Arab rulers for almost two centuries before native Persian dynasties could gradually drive them out. In this period a number of small and numerically inferior Arab tribes migrated to inland Iran.[8]

Also some Turkic tribes settled in Persia between the 9th and 12th centuries.[9]

In time these peoples were integrated into numerous Persian populations and adopted Persian culture and language while Persians retained their culture with minimal influence from outside.[10]

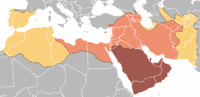

Conquest of Persia by Muslims

The explosive growth of the Arab Caliphate coincided with the chaos caused by the defeat of Sassanids in wars with the Byzantine Empire. Most of the country was conquered between 643 and 650 with the Battle of Nihawand marking the total collapse of the Sassanids.[11] Arabs defeated Persians and other Iranians and introduced their religion.

Yazdgerd III, the last Sassanid emperor, died ten years after he lost his empire to the newly-formed Muslim Caliphate. He tried to recover some of what he lost with the help of the Turks, but they were easily defeated by Muslim armies. Then he sought the aid of the Chinese Tang dynasty. However, the Chinese never intervened on behalf of the Sassanids and instead, appointed Peroz, son of Yazdgerd as the governor over his own territory which the Tang named the "protectorate of Persia". This territory was overrun by the Arabs around the early 660s and Peroz escaped to the Tang court. The Umayyads would rule Persia for a hundred years. The Arab conquest dramatically changed life in Persia. Arabic became the new lingua franca, Islam eventually replaced Zoroastrianism, and mosques were built.

In 750 the Umayyads were ousted from power by the Abbasid dynasty. By that time, Persians had come to play an important role in the bureaucracy of the empire.[12] The caliph Al-Ma'mun, whose mother was Persian, moved his capital away from Arab lands into Merv in eastern Iran.

Tahirid Persian Empire(821–873)

The Tahirid Persian empire (821-873) is considered to be the first independent Iranian empire from the Abbasid caliphate, established in Khorasan. The dynasty was founded by Tahir ibn Husayn and their capital was Nishapur. They ruled over the northeastern part of Iran (Persia), in the region of Khorasan (parts that are presently in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan). Tahir's military victories were rewarded with the gift of lands in the east of Persia, which were subsequently extended by his successors as far as the borders of India. They were overthrown by the Saffarids.

Saffarid Persian Empire

Ya'qub, the founder of Saffarid dynasty, seized control of the Seystan region, conquering all of modern-day eastern Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Using their capital (Zaranj) as base for an aggressive expansion eastwards and westwards, they overthrew the Tahirid Persian dynasty and annexed Khorasan in 873. By the time of Yaqub's death, he had conquered Kabul Valley, Sind, Tocharistan, Makran (Baluchistan), Kerman, Fars, Khorasan, and nearly reached Baghdad but then suffered defeat.[13]

Samanid Persian Empire

In 819, Samanids carved out a semi-independent state in eastern Persia to be among the first native Iranian rulers after the Arabic conquest. Despite having roots in Zoroastrianism theocratic nobility, they embraced Islam and propagated the religion deep into the heart of Central Asia. They made Samarqand, Bukhara and Herat their capitals and revived the Persian language and culture. The Samanid rulers displayed tolerance toward religious minorities as Zoroastrian clerics compiled and authored major religious texts, such as the Denkard, in Pahlavi. It was approximately during this age, when the poet Firdawsi finished the Shahnameh, an epic poem retelling the history of the Iranian kings. This epic was completed by AD 1009.

Buwayhid Persian Empire

In 913, western Persia was conquered by the Buwayhid, a Deylamite Persian tribal confederation from the shores of the Caspian Sea. Buyids were a Shī‘ah Iranian[14][15] dynasty which founded a confederation that controlled most of modern-day Iran and Iraq in the 10th and 11th centuries.

They made the city of Shiraz (In the Pars Province of Iran) their capital. The Buwayhids destroyed Islam's former territorial unity. Rather than a province of a united Muslim empire, Iran became one nation in an increasingly diverse and cultured Islamic world.

Turco-Persian rule (1037–1219)

Ghaznavid Empire(963–1187)

The Ghaznavids (Persian: غزنویان) were an Islamic and Persianate Empire of Turko-Persian mamluk[16] origin which existed from 975 to 1187 and ruled much of Persia, Transoxania, and the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.[17][18][19] The Ghaznavid state was centered in Ghazni, a city in present Afghanistan. Due to the political and cultural influence of their predecessors - that of the Persian Samanid Empire - the originally Turkic Ghaznavids became thoroughly Persianized.[17][19][20][21][22][23][24]

The dynasty was founded by Sebuktigin upon his succession to rule of territories centered around the city of Ghazni from his father-in-law, Alp Tigin, a break-away ex-general of the Samanid sultans.[25] Sebuktigin's son, Shah Mahmoud, expanded the empire in the region that stretched from the Oxus river to the Indus Valley and the Indian Ocean; and in the west it reached Rayy and Hamadan. Under the reign of Mas'ud I it experienced major territorial losses. It lost its western territories to the Seljuqs in the Battle of Dandanaqan resulting in a restriction of its holdings to Afghanistan, Balochistan and the Punjab. In 1151, Sultan Bahram Shah lost Ghazni to Ala'uddin Hussain of Ghor and the capital was moved to Lahore until its subsequent capture by the Persian Ghurids in 1186.

Although the Ghaznavids were of Turkic origin and their military leaders were generally of the same stock, as a result of the original involvement of Sebuktigin and Mahmud in Samanid affairs and in the Samanid cultural environment, the dynasty became thoroughly Persianized, so that in practice one cannot consider their rule over Iran one of foreign domination. In terms of cultural championship and the support of Persian poets, they were far more Persian than the ethnically Iranian Buyids rivals, whose support of Arabic letters in preference to Persian is well known.[26]

In fact with the adoption of Persian administrative and cultural ways the Ghaznavids threw off their original Turkish steppe background and became largely integrated with the Perso-Islamic tradition.[27]

Seljuk Empire

The Seljuks created a very large Middle Eastern empire. The Seljuks built the Friday Mosque in the city of Isfahan. The famous Persian mathematician and poet, Omar Khayyám, wrote his Rubaiyat during Seljuk times.

In the early 13th century the Seljuks lost control of Persia to another group of Turks from Khwarezmia, near the Aral Sea. The Shahs of the Khwarezmid Empire later ruled.

Mongols and their successors (1219–1500)

In 1218, Genghis Khan sent ambassadors and merchants to the city of Otrar, on the northeastern confines of the Khwarizm shahdom. The governor of Otrar had these envoys executed. Genghis attacked Otrar, Samarkand and other cities of the northeast in 1219.

Genghis' grandson, Hulagu Khan, finished the invasions that Genghis had begun when he defeated the Khwarzim Empire, Baghdad, and much of the rest of the Middle East from 1255 to 1258. Persia temporarily became the Ilkhanate, a division of the vast Mongol Empire.

In 1295, after Ilkhan Mahmud Ghazan converted to Islam, he forced Mongols in Persia to convert to Islam. The Ilkhans patronized the arts and learning in the great tradition of Iranian Islam; indeed, they helped to repair much of the damage of the Mongol conquests.

In 1335, the death of Abu Sa'id, the last well-recognized Ilkhan, spelled the end of the Ilkhanate. Though Arpa Ke'un was declared Ilkhan his authority was disputed and the Ilkhanate was splintered into a number of small states. This left Persia vulnerable to conquest at the hands of Timur the Lame or Tamerlane, a Central Asian conqueror seeking to revive the Mongol Empire. He ordered the attack of Persia beginning around 1370 and robbed the region until his death in 1405. Timur is known for his brutality; in Isfahan, for instance, he was responsible for the murder of 70,000 people so that he could build towers with their skulls[citation needed]. He conquered a wide area and made his own city of Samarkand rich, but he failed to forge a lasting empire. The Persian Empire was essentially in ruins.

For the next hundred years Persia was not a unified state. It was ruled for a while by descendants of Timur, called the Timurid emirs. Toward the end of the 15th century, Persia was taken over by the Emirate of the White Sheep Turkmen (Ak Koyunlu). But there was little unity and none of the sophistication that had defined Iran during the glory days of Islam.

Safavid Persian Empire (1500–1722)

The Safavid Dynasty hailed from the town of Ardabil in the region of Azarbaijan. The Safavid Shah Ismail I overthrew the White Sheep (Akkoyunlu) Turkish rulers of Persia to found a new native Persian empire. Ismail expanded Persia to include all of present-day Azerbaijan, Iran, and Iraq, plus much of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ismail's expansion was halted by the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, and war with the Ottomans became a fact of life in Safavid Iran.

Safavid Persia was a violent and chaotic state for the next seventy years, but in 1588 Shah Abbas I of Persia ascended to the throne and instituted a cultural and political renaissance. He moved his capital to Isfahan, which quickly became one of the most important cultural centers in the Islamic world. He made peace with the Ottomans. He reformed the army, drove the Uzbeks out of Iran and into modern-day Uzbekistan, and (with English help) recaptured the island of Hormuz from the Portuguese. Abdur Razzaq was the Persian ambassador to Calicut, India, and wrote vividly of his experiences there.[28]

The Safavids were followers of Shi'a Islam, and under them Persia (Iran) became the largest Shi'a country in the Muslim world, a position Iran still holds today.

Under the Safavids Persia enjoyed its last period as a major imperial power. In 1639, a final border was agreed upon with the Ottoman Empire with the Treaty of Qasr-e Shirin; which delineates the border between the Republic of Turkey and Iran and also that of between Iraq and Iran, today.

Persia and Europe (1722–1914)

In 1722, the Safavid state collapsed. That year saw the first European invasion of Persia since the time of Heraclius: Peter the Great, Emperor of Imperial Russia, invaded from the northwest as part of a bid to dominate central Asia. Ottoman forces accompanied the Russians, successfully laying siege to Isfahan.

The Russians conquered the city of Baku and its surroundings. The Turks also gained territory. However, the Safavids were severely weakened, and that same year (1722), the Afghans launched a bloody battle in response to the Safavids' attempts on trying to forcefully convert them from Sunni to Shi'a sect of Islam. The last Safavid shah was executed, and the dynasty came to an end.

The Persian empire experienced a temporary revival under Nader Shah in the 1730s and 1740s. Nadir checked the advances of the Russians and defeated the Afghans, later recapturing all of Afghanistan. He also launched successful campaigns against the nomadic khanates of Central Asia, and the Arabs of Oman. He also recaptured the territories lost to the Ottomans and invaded the Ottoman Empire. In 1739, he attacked and looted Delhi, the capital of Moghul India. After Nadir Shah was assassinated, the empire was ruled by the Zand dynasty. Iran was left unprepared for the worldwide expansion of European colonial empires in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century.

Persia found relative stability in the Qajar dynasty, ruling from 1779 to 1925, but lost hope to compete with the new industrial powers of Europe; Persia found itself sandwiched between the growing Russian Empire in Central Asia and the expanding British Empire in India. Each carved out pieces from the Persian empire that became Bahrain, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Georgia and Uzbekistan amongst other previous provinces.

Although Persia was never directly invaded, it gradually became economically dependent on Europe. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 formalised Russian and British control over the north and south of the country, respectively, where Britain and Russia each created a "sphere of influence", wherein the colonial power had the final say on economic matters.

At the same time Mozzafar-al-Din shah had granted a concession to William Knox D'Arcy, later the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, to explore and work the newly-discovered oil fields at Masjid Soleiman in southwest Persia, which started production in 1914. Winston Churchill, as First Sea Lord to the British Admiralty, oversaw the conversion of the Royal Navy to oil-fired battleships and partially nationalized it prior to the start of war. A small Anglo-Persian force was garrisoned there to protect the field from hostile tribal factions.

World War I and the Interbellum (1914–1935)

The Persian Campaign was waged on the Persian land during World War One.[29] Persia was drawn into the periphery of World War I because of its strategic position between Afghanistan and the warring Ottoman, Russian, and British Empires. In 1914 Britain sent a military force to Mesopotamia to deny the Ottomans access to the Persian oilfields. The German Empire retaliated on behalf of its ally by spreading a rumour that Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany had converted to Islam, and sent agents through Iran to attack the oil fields and raise a Jihad against British rule in India. Most of those German agents were captured by Persian, British and Russian troops who were sent to patrol the Afghan border, and the rebellion faded away. This was followed by a German attempt to abduct Ahmad Shah Qajar which was foiled at the last moment.

In 1916 the fighting between Russian and Ottoman forces to the north of the country had spilled down into Persia; Russia gained the advantage until most of her armies collapsed in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917. This left the Caucasus unprotected, and the Caucasian and Persian civilians starving after years of war and deprivation. In 1918 a small force of 400 British troops under General Dunsterville moved into the Trans-Caucasus from Persia in a bid to encourage local resistance to German and Ottoman armies who were about to invade the Baku oilfields. Although they later withdrew back into Persia, they did succeed in delaying the Turks access to the oil almost until the Armistice. In addition, the expedition’s supplies were used to avert a major famine in the region, and a camp for 30,000 displaced refugees was created near the Mesopotamian frontier.

In 1919, northern Persia was occupied by the British General William Edmund Ironside to enforce the Turkish Armistice conditions and help General Dunsterville and Colonel Bicherakhov to contain Bolshevik influence (of Mirza Kuchak Khan) in the north. Britain also took tighter control over the increasingly lucrative oil fields.

In 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi seized power from the Qajars and established the new Pahlavi dynasty, the last Persian monarchy before the establishment of the Islamic Republic. However, Britain and the Soviet Union remained the influential powers in Persia into the early years of the Cold War.

On March 21, 1935, Iran was officially accepted as the new name of the country. After Persian scholars' protested this decision on the grounds that it represented a break with their classical past and seemed to be unduly influenced by the "Aryan" propaganda from Nazi Germany, in 1953 Mohammad Reza Shah announced both names "Iran" and "Persia" could be used.[citation needed]

Legacy

The role of Persia (Iran) in history is highly significant; In fact, the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel considered the ancient Persians to be the first historic people and stated: "In Persia first arises that light which shines itself and illuminates what is around... The principle of development begins with the history of Persia; this constitutes therefore the beginning of history".[30]

Few nations in the world present more of a justification for the study of history than Iran.[31]

Timeline

|

See also

- Iran

- Greater Iran

- History of Iran

- Geography of Iran

- Aryan

- Persian people

- Persian culture

- Persianization

- Science in Persia

- List of kings of Persia

- List of Iranian scientists

- List of monarchies

- Capitals of Persia

- Prince of Persia (video game)

- Wildlife of Iran

References

- Stronach, David "Darius at Pasargadae: A Neglected Source for the History of Early Persia," Topoi

- Abdolhossein Zarinkoob, Ruzgaran: tarikh-i Iran az aghz ta saqut saltnat Pahlvi Sukhan, 1999. ISBN 964-6961-11-8

- Ali Akbar Sarfaraz, Bahman Firuzmandi Mad, Hakhamanishi, Ashkani, Sasani, Marlik, 1996. ISBN 964-90495-1-7

- Daniel, Elton, The History of Iran, Greenwood Press, 2001

- Iran Chamber Society (History of Iran)

Notes

- ^ Iranians, including Persians, Medians, Parthians and Bactrians and other Iranian ethnic groups. Iranians are Aryans of Iran (Iran means "Land of the Aryans"). Persian language is an Iranian language of Indo-Iranian branch.

- ^ R. Schmitt, DEIOCES in Encyclopedia Iranica

- ^ a b I.M. Diakonoff, “Media” in Cambridge History of Iran 2

- ^ Robert Rollinger, The Median “Empire”, the End of Urartu and Cyrus’ the Great Campaign in 547 B.C. (Nabonidus Chronicle II 16)

- ^ Hammond, N. G. L. (1988-11-24). The Cambridge Ancient History Set: The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 4: Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, c.525-479 BC: Persia, Greece and ... C.525-479 B.C. Ed.J.Boardman, Etc v. 4. John Boardman, D. M. Lewis (eds.) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0521228042.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Parpola, Simo. "Assyrian Identity in Ancient Times and Today" (PDF). Assyriology. Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. p. 3.

Ethnonyms like Arbāyu "Arab", Mādāyu "Mede", Muşurāyu "Egyptian", and Urarţāyu "Urartian" are from the late eighth century on frequently borne by fully Assyrianized, affluent individuals in high positions.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Pierre Briant "Cyrus the Great" The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. Ed. Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- ^ Zarinkoob, pp. 355-357

- ^ Zarinkoob, pp. 461, 519

- ^ Zarinkoob, p. 899

- ^ A Short History of Syriac Literature By William Wright. pg 44

- ^ ISBN 1-84212-011-5

- ^ Britannica, Saffarid dynasty

- ^ [1]

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica: DEYLAMITES

- ^ "Encyclopedia Britannica - Ghaznavid Dynasty"

- ^ a b C.E. Bosworth: The Ghaznavids. Edinburgh, 1963

- ^ C.E. Bosworth, "Ghaznavids", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition 2006, (LINK)

- ^ a b C.E. Bosworth, "Ghaznavids", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition; Brill, Leiden; 2006/2007

- ^ M.A. Amir-Moezzi, "Shahrbanu", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK): "... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkish heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- ^ Encyclopaedia Iranica, Iran: Islamic Period - Ghaznavids, E. Yarshater

- ^ B. Spuler, "The Disintegration of the Caliphate in the East", in the Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. IA: The Central islamic Lands from Pre-Islamic Times to the First World War, ed. by P.M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton, and Bernard Lewis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970). pg 147: One of the effects of the renaissance of the Persian spirit evoked by this work was that the Ghaznavids were also Persianized and thereby became a Persian dynasty.

- ^ Anatoly M Khazanov, André Wink, "Nomads in the Sedentary World", Routledge, 2padhte padhte to pagla jayega aadmi, "A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia", Blackwell Publishing, 1998. pg 370: "Though Turkic in origin and, apparently in speech, Alp Tegin, Sebuk Tegin and Mahmud were all thoroughly Persianized"

- ^ Robert L. Canfield, Turko-Persia in historical perspective, Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 8: "The Ghaznavids (989-1149) were essentially Persianized Turks who in manner of the pre-Islamic Persians encouraged the development of high culture"

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, Ghaznavid Dynasty, Online Edition 2007 (LINK)

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica, Iran, EHSAN YARSHATER, Online Edition 2008, ([2])

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth, The new Islamic dynasties: a chronological and genealogical manual, Edition: 2, Published by Edinburgh University Press, 2004, ISBN 0748621377, p. 297

- ^ "European Domination of the Indian Ocean Trade". Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ William J. Olson "Anglo-Iranian Relations During World War I" Routledge, 1984, pp. 1–305

- ^ Georg Hegel in The Philosophy of History, (trans.) J. Sibree, Buffalo, 1991, p. 173.

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye in The Golden Age of Persia.

Further reading

- Bailey, Harold (ed.) The Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press 1993, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-45148-5

- Wiesehofer, Josef: Ancient Persia

- J. E Curtis and N. Tallis: Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia

- Pierre Briant: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Eisenbrauns: 2002, ISBN 978-1-57506-0310

- Richard N. Frye: The Heritage of Persia

- A.T. Olmstead: History of the Persian Empire

- Lindsay Allen: The Persian Empire

- J.M. Cook: The Persian Empire

- Tom Holland: Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West

- Amini Sam: Pictorial History of Iran: Ancient Persia Before Islam 15000 B.C.-625 A.D.

- Timelife Persians: Masters of the Empire (Lost Civilizations)

- Houchang Nahavandi, The Last Shah of Iran - Fatal Countdown of a Great Patriot betrayed by the Free World, a Great Country whose fault was Success, Aquilion, 2005, ISBN 1-904997-03-1

- Farrokh, Kaveh: Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War, Osprey: 2007, ISBN 978-1-84603-108-3

- Brosius, Maria: The Persians: An Introduction, Routledge:2006, ISBN 978-0-41532-090-0

- Wiesehofer, Joseph Ancient Persia New York:1996 I.B. Tauris

External links

- The Persian Empire

- Iran, The Forgotten Glory - Documentary Film About Ancient Iran (achaemenids & Sassanids)

- Iran before Iranians - Complete History of Persian Empire

- Iran’s Cultural Heritage News Agency (CHN)

- Persia, by S.G.W. Benjamin, 1891

- Iran Cultural Heritage Organization Documentation Center (Persian)

- Ancient History Sourcebook: Persia

- Iran Cultural Heritage Organization Technical Office for Preservation and Restoration (Persian)

- Iran Research Center for Conservation of Cultural Relics

- Persepolis Official website

- Persian Language (Persian)

- Oriental Institute Photographic Archives (Nearly 1,000 archaeological photographs of Persepolis and Ancient Persia)

- Hamid-Reza Hosseini, Shush at the foot of Louvre (Shush dar dāman-e Louvre), in Persian, Jadid Online, 10 March 2009, [3].

Audio slideshow: [4] (6 min 31 sec).

- Articles needing cleanup from March 2009

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from March 2009

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from March 2009

- Articles to be split from August 2009

- History of Iran

- Former empires

- Former monarchies of Asia

- Achaemenid Empire

- Medes

- Pre Islamic history of Afghanistan

- History of Iraq

- Persian-speaking countries and territories

- Ancient Persia

- Civilizations