Apollo program

The Apollo program was the United States spaceflight effort which landed the first humans on Earth's Moon. Conceived during the Eisenhower administration and conducted by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Apollo began in earnest after President John F. Kennedy's 1961 address to Congress declaring a national goal of "landing a man on the Moon" by the end of the decade[1][2] in a competition with the Soviet Union for supremacy in space.

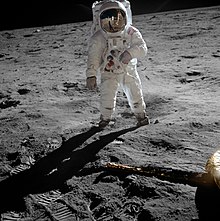

This goal was first accomplished during the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969 when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed, while Michael Collins remained in lunar orbit. Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last in December 1972. In these six Apollo spaceflights, 12 men walked on the Moon. These are the only times humans have landed on another celestial body.[3]

The Apollo program ran from 1961 until 1975, and was America's third human spaceflight program (following Mercury and Gemini). It used Apollo spacecraft and Saturn launch vehicles, which were also used for the Skylab program in 1973–74, and a joint U.S.–Soviet mission in 1975. These subsequent programs are thus often considered part of the Apollo program.

The program was successfully carried out despite two major setbacks: the 1967 Apollo 1 launch pad fire that killed three astronauts; and an oxygen tank rupture during the 1970 Apollo 13 flight which disabled the Command Module. Using the Lunar Excursion Module as a "lifeboat", the three crewmen narrowly escaped with their lives, thanks to their skills and the efforts of flight controllers, project engineers, and backup crew members.

Apollo set major milestones in human spaceflight. It stands alone in sending manned missions beyond low Earth orbit; Apollo 8 was the first manned spacecraft to orbit another celestial body, while Apollo 17 marked the last moonwalk and the last manned mission beyond low Earth orbit. The program spurred advances in many areas of technology incidental to rocketry and manned spaceflight, including avionics, telecommunications, and computers. Apollo also sparked interest in many fields of engineering and left many physical facilities and machines developed for the program as landmarks. Its command modules and other objects and artifacts are displayed throughout the world, notably in the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museums in Washington, DC and at NASA's centers in Florida, Texas and Alabama.

MOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSESMOOSES

Choosing a mission mode

Once Kennedy had defined a goal, the Apollo mission planners were faced with the challenge of designing a set of flights that could meet it while minimizing risk to human life, cost, and demands on technology and astronaut skill. Four possible mission modes were considered:

- Direct Ascent: A spacecraft would travel directly to the Moon, landing and returning as a unit. This plan would have required a more powerful booster, the planned Nova rocket.

- Earth Orbit Rendezvous (EOR): Multiple rockets (up to fifteen in some claims) would be launched, each carrying various parts of a Direct Ascent spacecraft and propulsion units that would have enabled the spacecraft to escape earth orbit. After a docking in earth orbit, the spacecraft would have landed on the Moon as a unit.

- Lunar Surface Rendezvous: Two spacecraft would be launched in succession. The first, an automated vehicle carrying propellants, would land on the Moon and would be followed some time later by the manned vehicle. Propellant would be transferred from the automated vehicle to the manned vehicle before the manned vehicle could return to Earth.

- Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR): One Saturn V would launch a spacecraft that was composed of modular parts. A command module would remain in orbit around the Moon, while a lunar excursion module would descend to the Moon and then return to dock with the command ship while still in lunar orbit. In contrast with the other plans, LOR required only a small part of the spacecraft to land on the Moon, thereby minimizing the mass to be launched from the Moon's surface for the return trip.

In early 1961, direct ascent was generally the mission mode in favor at NASA. Many engineers feared that a rendezvous —let alone a docking— neither of which had been attempted even in Earth orbit, would be extremely difficult in lunar orbit. However, dissenters including John Houbolt at Langley Research Center emphasized the important weight reductions that were offered by the LOR approach. Throughout 1960 and 1961, Houbolt campaigned for the recognition of LOR as a viable and practical option. Bypassing the NASA hierarchy, he sent a series of memos and reports on the issue to Associate Administrator Robert Seamans; while acknowledging that he spoke "somewhat as a voice in the wilderness," Houbolt pleaded that LOR should not be discounted in studies of the question.[4]

Seamans' establishment of the Golovin committee in July 1961 represented a turning point in NASA's mission mode decision.[5] While the ad-hoc committee was intended to provide a recommendation on the boosters to be used in the Apollo program, it recognized that the mode decision was an important part of this question. The committee recommended in favor of a hybrid EOR-LOR mode, but its consideration of LOR —as well as Houbolt's ceaseless work— played an important role in publicizing the workability of the approach. In late 1961 and early 1962, members of NASA's Space Task Group at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston began to come around to support for LOR.[5] The engineers at Marshall Space Flight Center took longer to become convinced of its merits, but their conversion was announced by Wernher von Braun at a briefing in June 1962. NASA's formal decision in favor of LOR was announced on July 11, 1962. Space historian James Hansen concludes that:

Without NASA's adoption of this stubbornly held minority opinion in 1962, the United States may still have reached the Moon, but almost certainly it would not have been accomplished by the end of the 1960s, President Kennedy's target date.

— James Hansen, Enchanted Rendezvous[6]

The LOR method had the advantage of allowing the lander spacecraft to be used as a "life boat" in the event of a failure of the command ship. This happened on Apollo 13 when an oxygen tank failure left the command ship without electrical power. The Lunar Module provided propulsion, electrical power and life support to get the crew home safely.

Spacecraft

Preliminary design studies of Apollo spacecraft began in 1960 as a three-man command module supported by one of several service modules providing propulsion and electrical power, sized for use in various possible missions, such as: shuttle service to a space station, a circumlunar flight, or return to Earth from a lunar landing. Once the Moon landing goal became official, detailed design began of the Command/Service Module (CSM), in which the crew would spend the entire direct-ascent mission and lift off from the lunar surface for the return trip. (An even larger, separate propulsion module would have been required for the lunar descent.)

The final choice of lunar orbit rendezvous changed the CSM's role to a translunar ferry used to take the crew and a new spacecraft, the Lunar Module (LM), which would take two men to the lunar surface and return them to the CSM.

As the program concept evolved, use of the term "module" changed from its true meaning of an interchangeable component of systems with multiple variants, to simply a component of the complete lunar landing system.

Command/Service Module

The Command Module (CM) was the crew cabin, surrounded by a conical re-entry heat shield, designed to carry three astronauts from launch to lunar orbit and back to an Earth ocean splashdown. As such, it was the only component of the Apollo spacecraft to survive without major configuration changes as the program evolved from the early Apollo study designs. Equipment carried by the Command Module included reaction control engines, a docking tunnel, guidance and navigation systems and the Apollo Guidance Computer.

Attached to the Command Module was the cylindrical Service Module (SM), which housed the service propulsion engine and its propellants, the fuel cell power system, four maneuvering thruster quads, a high-gain S-band antenna for communications between the Moon and Earth, and storage tanks for water and oxygen. On the last three lunar missions, it also carried a scientific instrument package. Because its configuration was chosen early before the selection of lunar orbit rendezvous, the service propulsion engine was sized to lift the CSM off of the Moon, and thus oversized to about twice the thrust required for translunar flight.

As used in the actual lunar program, the two modules remained attached throughout most of the flight to make a single ferry craft, somewhat awkwardly known as the Command/Service Module (CSM) which carried a separate lunar lander (only half as heavy as the CSM) to the Moon, and the astronauts home to Earth. Just before re-entry, the Service Module was discarded and only the Command Module re-entered the atmosphere, using its heat shield to survive the intense heat caused by air friction. After re-entry it deployed parachutes that slowed its descent, allowing a smooth splashdown in the ocean.

Under the leadership of Harrison Storms, North American Aviation won the contract to build the CSM, and also the second stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle for NASA. Relations between North American and NASA were strained during the winter of 1965-66 by delivery delays, quality shortfalls, and cost overruns in both components.[7] They were strained even more a year later when a cabin fire killed the crew of Apollo 1 during a ground test. The cause was determined to be an electrical short in the wiring of the Command Module; while the determination of responsibility for the accident was complex, the review board concluded that "deficiencies existed in Command Module design, workmanship and quality control."[8] This eventually led to the removal of Storms as Command Module program manager.[9]

Lunar Module

The Lunar Module (LM) (originally known as the Lunar Excursion Module, or LEM), was designed to fly between lunar orbit and the surface, landing two astronauts on the Moon and taking them back to the Command Module. It had no aerodynamic heat shield and was of a construction so lightweight that it would not have been able to fly through the Earth's atmosphere. It consisted of two stages, a descent and an ascent stage. The descent stage contained compartments which carried cargo such as the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package and Lunar Rover.

The contract for design and construction of the Lunar Module was awarded to Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, and the project was overseen by Tom Kelly. There were also problems with the Lunar Module; due to delays in the test program, the LM became a "pacing item," meaning that it was in danger of delaying the schedule of the whole Apollo program.[10] The first manned LM was not ready for its planned Earth orbit test in December 1968, but the program was kept on schedule by cancelling a second manned Earth orbit LM flight.

Launch vehicles

When the team of engineers led by Wernher von Braun began planning for the Apollo program, it was not yet clear what mission their rockets would have to support. Direct ascent would require a more powerful launch vehicle, the planned Nova, which could carry a very large payload to the Moon. NASA's decision in favor of Lunar Orbit Rendezvous re-oriented the work of the Marshall Space Flight Center towards the development of the Saturn I, Saturn IB and Saturn V. While the Saturn V was less powerful than the Nova would have been, it was still much more powerful than any rocket developed before, or since. (The USSR N1 was approximately as powerful, but it was never successful.)

Saturn IB

The Saturn IB was an upgraded version of the earlier Saturn I rocket, which was used in early Apollo boilerplate launches. It consisted of:

- An S-IB first stage powered by eight H-1 engines burning RP-1 with LOX oxidizer, to produce 1,600,000 pounds-force (7,100 kilonewtons) of thrust;

- An S-IVB-200 second stage, powered by one J-2 engine burning liquid hydrogen with LOX oxidizer, to produce 225,000 lbf (1,000 kN) of thrust; and

- An Instrument Unit which contained the rocket's guidance system.

The Saturn IB was capable of putting a partially-fueled Command/Service Module, or a Lunar Module, into earth orbit.[11] It was used in five of the Apollo test missions including the first manned mission. It was also used in the manned missions for the Skylab program and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

Saturn V

The Saturn V was a three-stage rocket consisting of:

- An S-IC first stage, powered by five F-1 engines arranged in a cross pattern, burning RP-1 with LOX oxidizer to produce 7,500,000 lbf (33,000 kN) of thrust. They burned for 2.5 minutes, accelerating the spacecraft to a speed of approximately 6,000 miles per hour (2.68 km/s).[12]

- An S-II second stage, powered by five of the J-2 engines used in the S-IVB. They burned for approximately six minutes, taking the spacecraft to a speed of 15,300 miles per hour (6.84 km/s) and an altitude of about 115 miles (185 km).[13]

- An S-IVB-500 third stage similar to the Saturn IB's second stage, with capability to restart the J-2 engine. The engine would burn for approximately two and a half minutes and shut down when a low-Earth parking orbit was achieved. After approximately two orbits to confirm the spacecraft was ready to commit to the lunar trip, the engine was restarted to make the translunar injection maneuver taking the spacecraft into an extremely high orbit where it would be captured by the Moon's gravity.[14]

- An instrument unit with a guidance system similar to that used on the Saturn IB.

Three Saturn V vehicles launched on Earth orbital flights. Two of the three (Apollo 4 and 6) were unmanned tests of the command and service modules, and the third was a manned flight, Apollo 9, testing the lunar module. Nine Saturn Vs launched manned Apollo missions to the Moon, including Apollo 11. It was also used for the unmanned launch of Skylab.

Astronauts

The following astronauts flew on the 11 manned Apollo missions, plus the Apollo 1 crew who were killed in a ground test one month before they were to have flown the first manned mission. Not included are the astronauts who subsequently flew on the Skylab (Apollo Applications Program) or Apollo-Soyuz Test Project missions which used the Apollo CSM.

| Mission | CDR | Group | Mission # | CMP | Group | Mission # | LMP | Group | Mission # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apollo 1 | Grissom | 1 | (3) | White | 2 | (2) | Chaffee | 3 | (1) |

| Apollo 7 | Schirra | 1 | 3 | Eisele | 3 | 1 | Cunningham | 3 | 1 |

| Apollo 8 | Borman | 2 | 2 | Lovell | 2 | 3 | Anders | 3 | 1 |

| Apollo 9 | McDivitt | 2 | 2 | Scott | 3 | 2 | Schweickart | 3 | 1 |

| Apollo 10 | Stafford | 2 | 3 | Young | 2 | 3 | Cernan | 3 | 2 |

| Apollo 11 | Armstrong | 2 | 2 | Collins | 3 | 2 | Aldrin | 3 | 2 |

| Apollo 12 | Conrad | 2 | 3 | Gordon | 3 | 2 | Bean | 3 | 1 |

| Apollo 13 | Lovell | 2 | 4 | Swigert | 5 | 1 | Haise | 5 | 1 |

| Apollo 14 | Shepard | 1 | 2 | Roosa | 5 | 1 | Mitchell | 5 | 1 |

| Apollo 15 | Scott | 3 | 3 | Worden | 5 | 1 | Irwin | 5 | 1 |

| Apollo 16 | Young | 2 | 4 | Mattingly | 5 | 1 | Duke | 5 | 1 |

| Apollo 17 | Cernan | 3 | 3 | Evans | 5 | 1 | Schmitt | 4 | 1 |

Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM)

Mission rules specified that, in most circumstances, only one person in the Mission Control Center would communicate directly with the in-flight crew, and that this was to be another astronaut, who would be best able to understand the situation in the spacecraft and communicate with the crew in the clearest way. These individuals were designated Capsule Communicators or CAPCOMs, a term carried over from the Mercury and Gemini programs. They were usually chosen from the backup and support crews, and worked in shifts during long missions.

The periodic beeps heard during communications with the astronauts are known as Quindar tones.

Missions

Mission types

see List of Apollo mission types

Unmanned missions

Apollo required more than six years of spacecraft and launch vehicle development and testing before the first manned missions could be flown. Test flights of the Saturn I launch vehicle began in October 1961 and lasted until September 1964. Three further Saturn I launches carried boilerplate models of the Apollo command/service module. Two pad abort tests of the launch escape system took place in 1963 and 1965 at the White Sands Missile Range. Three unmanned tests of Apollo components with the Saturn IB (Apollo-Saturn, or AS) were officially designated AS-201, AS-202, and AS-203.

The only unmanned missions to be publicly designated as "Apollo" followed by a sequence number were Apollo 4, Apollo 5 and Apollo 6.[15] The simple numbering was started at "4" to follow the three Apollo-Saturn IB flights, though all subsequent flights kept the "AS" designations: AS-204 and following for Saturn IB flights, and AS-501 and following for Saturn V flights.

Apollo 4 was the first unmanned test flight of the Saturn V launch vehicle, carrying a Command/Service Module (CSM). Launched on November 9, 1967, Apollo 4 exemplified George Mueller's strategy of "all up" testing. Rather than being tested stage by stage, as most rockets were, the Saturn V would be flown for the first time as one unit. Walter Cronkite covered the launch from a broadcast booth about 4 miles (6 km) from the launch site. The extreme noise and vibrations from the launch nearly shook the broadcast booth apart- ceiling tiles fell and windows shook. At one point, Cronkite was forced to dampen the booth's plate glass window to prevent it from shattering.[16] This launch showed that additional protective measures were necessary to protect structures in the immediate vicinity. Future launches used a damping mechanism directly at the launchpad which proved effective in limiting the generated noise. The mission was a highly successful one, demonstrating the capability of the Command Module's heat shield to survive a trans-lunar return reentry by using the Service Module engine to ram it into the atmosphere at higher than the usual earth-orbital reentry speed.

Apollo 5 was the first unmanned test flight of the Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit, launched on January 22, 1968, by a Saturn IB. The critical LM engines were successfully tested (though a computer programming error cut one test firing short), including an in-flight test of the second stage engine in "abort mode," in which the ascent engine is fired simultaneously with the jettison of the descent stage. This capability was made available, only to be used in the event of a critical problem on the Moon landing, such as running out of descent fuel, but was never needed.

Apollo 6 was the last unmanned Saturn V flight, launched on April 4, 1968. It carried a CSM and a Lunar Module Test Article near the mass of the Lunar Module for ballast. It was planned to achieve translunar injection, then after 5 minutes, use the Service Module engine to return the CM to Earth, thus demonstrating the Saturn V's ability to send the Apollo craft to the Moon, and a direct return-to-Earth abort capability. However, "pogo" vibrations caused premature shutdown of two second-stage engines, and failure of the third stage to re-light for the translunar injection. Instead, the Service Module engine was used as in Apollo 4 to raise the craft to a higher Earth orbit, and bring the CM back at a velocity midway between that of low Earth orbit and lunar return velocity. This mission was considered successful enough to launch men on the next Saturn V flight, since fixes for the vibration problem were identified.

Manned missions

The manned missions carried three astronauts, designated as Commander, Command Module Pilot (CMP), and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP). Besides exercising all crew command decisions, the Commander was the primary pilot of both spacecraft (when present) and was first to exit the LM on the surface of the Moon. The CMP functioned as navigator, usually performed the initial docking with the LM, and remained in the Command/Service Module when his companions flew the LM. The LMP functioned as engineering officer, monitoring the systems of both spacecraft. On a landing mission, he accompanied the Commander on the lunar surface. On the last flight, the LMP was a professional geologist, Dr. Harrison Schmitt.

Apollo 7, launched on October 11, 1968, was the first manned mission in the program. It was an eleven-day Earth-orbital flight intended to test the Command Module, redesigned following the Apollo 1 fire. It was the first manned launch of the Saturn IB launch vehicle and the first three-man American space mission.

Between December 21, 1968 and May 18, 1969, NASA planned to launch three manned test / practice missions using the Saturn V launch vehicle and the complete spacecraft including the LM. But by the summer of 1968 it became clear to program managers that a fully functional LM would not be available for the Apollo 8 launch. Rather than waste the Saturn V on another simple Earth-orbiting mission, they chose to send the crew planned to make the second orbital LM test in Apollo 9, to orbit the Moon in the CSM on Apollo 8 during Christmas. The original idea for this switch was the brainchild of George Low, Manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office. Although it has often been claimed that this change was made as a direct response to Soviet attempts to fly a piloted Zond spacecraft around the Moon, there is no evidence that this was the case. NASA officials were aware of the Soviet Zond flights, but the timing of the Zond missions does not correspond well with the extensive written record from NASA about the Apollo 8 decision. The Apollo 8 decision was primarily based upon the LM schedule, not fear of the Soviets beating the Americans to the Moon.

This was followed by the first orbital manned LM flight on Apollo 9 (with the original Apollo 8 crew), and the lunar "dress rehearsal" Apollo 10 which took the LM to within 50,000 feet (15 km) of the surface, but did not land.

That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.

The next two flights (11 and 12) included successful Moon landings. The Apollo 13 mission was aborted before the landing attempt, but the crew returned safely to Earth. The four subsequent Apollo missions (14 through 17) included successful Moon landings. The last three of these were J-class missions that included the use of Lunar Rovers.

Apollo 17, launched December 7, 1972, was the last Apollo mission to the Moon. Mission commander Eugene Cernan was the last person to leave the Moon's surface. The crew returned safely to Earth on December 19, 1972.

Summary of flights

| Flight | Launch vehicle | Crew | Launch date | Mission | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS-201 | Saturn 1B | Unmanned | February 26, 1966 | Suborbital CSM flight | First test of Saturn IB and Block I Apollo Command and Service Modules; demonstrated heat shield; propellant pressure loss caused premature SM engine shutdown |

| AS-203 | Saturn IB | Unmanned | July 5, 1966 | Test liquid hydrogen behavior in Earth orbit | No Apollo spacecraft carried; successfully verified restartable S-IVB stage design for Saturn V. Additional testing designed to rupture the tank inadvertently destroyed the stage. |

| AS-202 | Saturn IB | Unmanned | August 25, 1966 | Suborbital CSM flight | Longer duration to Pacific Ocean spashdown; CM heat shield tested to higher speed; successful SM firings |

| AS-204 (Apollo 1) | Saturn IB | Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, Edward White, Roger B. Chaffee | None | Block I CSM Earth orbital flight (up to fourteen days) | Cabin fire broke out in pure oxygen atmosphere during launch rehearsal test on 27 January 1967, killing all three crewmen and destroying the CM before planned February 21 launch. |

| Apollo 4 | Saturn V | Unmanned | November 9, 1967 | First Saturn V / CSM flight in Earth orbit | Successfully demonstrated S-IVB third stage restart and tested CM heat shield at lunar re-entry speeds |

| Apollo 5 | Saturn IB | Unmanned | January 22, 1968 | First Lunar Module flight in Earth orbit | Successfully fired descent engine and ascent engine; demonstrated "fire-in-the-hole" landing abort test. Used the Saturn IB originally slated for Apollo 1. |

| Apollo 6 | Saturn V | Unmanned | April 4, 1968 | CSM test: trans-lunar injection with direct abort to high-speed re-entry | Severe "pogo" vibrations caused two second-stage engines engines to shut down prematurely, and third stage restart to fail. SM engine used to achieved high-speed re-entry, though less than Apollo 4. NASA identified vibration fixes and declared Saturn V man-rated. |

| Apollo 7 | Saturn IB | Walter M. "Wally" Schirra, Donn Eisele, Walter Cunningham | October 11, 1968 | Block II CSM Earth orbital test | Successful eleven-day flight. First live television broadcast from a US space flight |

| Apollo 8 | Saturn V | Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, William A. Anders | December 21, 1968 | Lunar orbit (CSM only) | First manned lunar flight, improvised because LM was not ready for first manned orbital test. Ten lunar orbits in twenty hours; first humans to see lunar far side and Earthrise with own eyes;

Live television pictures broadcast to Earth |

| Apollo 9 | Saturn V | James McDivitt, David Scott, Russell L. "Rusty" Schweickart | March 3, 1969 | Earth orbit CSM / LM test | Ten days in Earth orbit, demonstrated LM propulsion, rendezvous and docking with CSM. EVA tested lunar Portable Life Support System (PLSS). |

| Apollo 10 | Saturn V | Thomas P. Stafford, John W. Young, Eugene Cernan | May 18, 1969 | "Dress rehearsal" for lunar landing | LM descended to 8.4 nautical miles (15.6 km) without landing |

| Apollo 11 | Saturn V | Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin | July 16, 1969 | First lunar landing | Sea of Tranquility; single EVA in direct vicinity of LM. Navigation errors and computer alarms overcome |

| Apollo 12 | Saturn V | Charles "Pete" Conrad, Richard Gordon, Alan Bean | November 14, 1969 | Precision lunar landing | Successful landing in Ocean of Storms near Surveyor 3 probe; two EVAs; returned Surveyor parts to earth; first controlled LM ascent stage impact after jettison; first use of deployable S-band antenna; two lightning strikes after liftoff with brief loss of fuel cells and telemetry; lunar TV camera damaged by accidental exposure to sun. |

| Apollo 13 | Saturn V | Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, Fred Haise | April 11, 1970 | Lunar landing (Fra Mauro) | Landing cancelled after SM oxygen tank explosion on outward leg; LM used as crew "lifeboat" for safe return. First S-IVB stage impact on Moon as active seismic test. |

| Apollo 14 | Saturn V | Alan B. Shepard, Stuart Roosa, Edgar Mitchell | January 31, 1971 | Lunar landing (Fra Mauro) | Successful landing at Fra Mauro site intended for Apollo 13; mission overcame docking problems, faulty LM abort switch and delayed landing radar acquisition; first color video images from the lunar surface; first materials science experiments in space; two EVAs |

| Apollo 15 | Saturn V | David Scott, Alfred Worden, James Irwin | July 26, 1971 | Extended lunar landing | First "J series" mission with 3-day lunar stay and extensive geology investigations; first use of lunar rover (17.25 miles (27.8 km) driven); 1 lunar "standup" EVA, 3 lunar surface EVAs, plus deep space EVA on return to retrieve orbital camera film from SM. |

| Apollo 16 | Saturn V | John W. Young, Ken Mattingly, Charles Duke | April 16, 1972 | Extended lunar landing | Only landing in lunar highlands; malfunction in a backup CSM yaw gimbal servo loop delayed landing and reduced stay in lunar orbit; no ascent stage deorbit due to malfunction; 3 lunar EVAs plus deep space EVA |

| Apollo 17 | Saturn V | Eugene Cernan, Ronald Evans, Harrison H. "Jack" Schmitt | December 7, 1972 | Extended lunar landing | Last Apollo lunar landing; last (to date) human flight beyond low Earth orbit; only lunar mission with a scientist (geologist); 3 lunar EVAs plus deep space EVA |

| Apollo 18, 19, and 20 | Saturn V | None flew | Cancelled | Extended lunar landings | Cancelled to free one Saturn V to launch Skylab and to cut costs |

Samples returned

| Lunar Mission | Sample Returned |

|---|---|

| Apollo 11 | 22 kg |

| Apollo 12 | 34 kg |

| Apollo 14 | 43 kg |

| Apollo 15 | 77 kg |

| Apollo 16 | 95 kg |

| Apollo 17 | 111 kg |

The Apollo program returned 841.5 lb (381.7 kg) of rocks and other material from the Moon, much of which is stored at the Lunar Receiving Laboratory in Houston. The only sources of Moon rocks on Earth are those collected from the Apollo program, the former Soviet Union's Luna missions, and lunar meteorites.

The rocks collected from the Moon are extremely old compared to rocks found on Earth, as measured by radiometric dating techniques. They range in age from about 3.2 billion years old for the basaltic samples derived from the lunar mare, to about 4.6 billion years for samples derived from the highlands crust.[18] As such, they represent samples from a very early period in the development of the Solar System that is largely missing from Earth. One important rock found during the Apollo Program was the Genesis Rock, retrieved by astronauts James Irwin and David Scott during the Apollo 15 mission. This rock, called anorthosite, is composed almost exclusively of the calcium-rich feldspar mineral anorthite, and is believed to be representative of the highland crust. A geochemical component called KREEP was discovered that has no known terrestrial counterpart. Together, KREEP and the anorthositic samples have been used to infer that the outer portion of the Moon was once completely molten (see lunar magma ocean).

Almost all the rocks show evidence for having been affected by impact processes. For instance, many samples appear to be pitted with micrometeoroid impact craters, something which is never seen on earth due to its thick atmosphere. Additionally, many show signs of being subjected to high pressure shock waves that are generated during impact events. Some of the returned samples are of impact melt, referring to materials that are melted near an impact crater. Finally, all samples returned from the Moon are highly brecciated as a result of being subjected to multiple impact events.

Analysis of composition of the lunar samples support the giant impact hypothesis, that the Moon was created through a "giant impact" of a large astronomical body with the Earth.[19]

Program costs and cancellation

When President Kennedy first chartered the Moon landing program, a preliminary cost estimate of $7 billion was generated, but this proved an extremely unrealistic guess of what could not possibly be determined precisely, and James Webb used his administrator's judgement to change the estimate to $20 billion before giving it to Vice President Johnson.[20] Webb's estimate shocked everyone at the time, but ultimately proved to be reasonably accurate. The final cost of project Apollo was reported to Congress as $25.4 billion in 1973.[21]

In 2009, NASA held a symposium on project costs which presented an estimate of the Apollo program costs in 2005 dollars as roughly $170 billion. This included all research and development costs; the procurement of 15 Saturn V rockets, 16 Command/Service Modules, 12 Lunar Modules, plus program support and management costs; construction expenses for facilities and their upgrading, and costs for flight operations. This was based on a Congressional Budget Office report, A Budgetary Analysis of NASA’s New Vision for Space, September 2004.[20]

Canceled missions

Originally three additional lunar landing missions had been planned, as Apollo 18 through Apollo 20. In light of the drastically shrinking NASA budget and the decision not to produce a second batch of Saturn Vs, these missions were canceled to make funds available for the development of the Space Shuttle, and to make their Apollo spacecraft and Saturn V launch vehicles available to the Skylab program. Only one of the remaining Saturn Vs was actually used to launch the Skylab orbital laboratory in 1973; the others became museum exhibits at the John F. Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Florida, George C. Marshall Space Center in Huntsville, Alabama, Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Apollo Applications Program

Following the success of the Apollo program, both NASA and its major contractors investigated several post-lunar applications for Apollo hardware. The Apollo Extension Series, later called the Apollo Applications Program, proposed up to 30 flights to Earth orbit. Many of these would use the space that the lunar module took up in the Saturn rocket to carry scientific equipment. Of all the plans, only two were implemented: the Skylab space station and the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project.

Skylab's fuselage was constructed from the second stage of a Saturn IB, and the station was equipped with the Apollo Telescope Mount, itself based on a lunar module. The station's three crews were ferried into orbit atop Saturn IBs, riding in CSMs; the station itself had been launched with a modified Saturn V. Skylab's last crew departed the station on February 8, 1974, and the station itself re-entered the atmosphere in 1979, by which time it had become the oldest operational Apollo-Saturn component.

The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project involved a docking in Earth orbit between a CSM and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft from July 15 to July 24, 1975. NASA's next manned mission would not be until STS-1 in 1981.

Recent observations

In 2008, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's SELENE probe observed evidence of the halo surrounding the Apollo 15 lunar module blast crater while orbiting above the lunar surface.[23] In 2009, NASA's robotic Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, while orbiting 50 kilometres (31 mi) above the moon, photographed the remnants of the Apollo program left on the lunar surface, and photographed each site where manned Apollo flights landed.[24][25]

In a November 16, 2009 editorial, The New York Times opined that: "[T]here’s something terribly wistful about these photographs of the Apollo landing sites. The detail is such that if Neil Armstrong were walking there now, we could make him out, make out his footsteps even, like the astronaut footpath clearly visible in the photos of the Apollo 14 site. Perhaps the wistfulness is caused by the sense of simple grandeur in those Apollo missions. Perhaps, too, it’s a reminder of the risk we all felt after the Eagle had landed — the possibility that it might be unable to lift off again and the astronauts would be stranded on the Moon. But it may also be that a photograph like this one is as close as we’re able to come to looking directly back into the human past."[22]

Proposed future lunar landing missions, such as the Google Lunar X Prize, intend to record close-up images of the Apollo Lunar Modules and other artificial objects on the surface.[26]

Legacy

Science and engineering

The Apollo program, specifically the lunar landings, has been called the greatest technological achievement in human history.[27][28] The program stimulated many areas of technology. The flight computer design used in both the lunar and command modules was, along with the Minuteman Missile System, the driving force behind early research into integrated circuits. The fuel cell developed for this program was the first practical fuel cell. Computer-controlled machining (CNC) was pioneered in fabricating Apollo structural components.

Cultural impact

The crew of Apollo 8, the first manned spacecraft to orbit the Moon, sent televised pictures of the Earth and the Moon back to Earth (left), and read from the creation story in the Biblical book of Genesis, on Christmas Eve, 1968, This was believed to be the most widely-watched television broadcast until that time. The mission and Christmas provided an inspiring end to 1968, which had been a bad year for the U.S., marked by Vietnam War protests, race riots, and the assassinations of civil rights leader Martin Luther King and Senator Robert Kennedy.

An estimated one-fifth of the population of the world watched the live transmission of the first Apollo moonwalk.[29]

One legacy of the Apollo program is the now-common view of Earth as a fragile, small planet, captured in photographs taken by the astronauts during the lunar missions. The most famous, taken by the Apollo 17 astronauts, is The Blue Marble (right). These photographs have also motivated some people toward environmentalism.[30]

Many astronauts and cosmonauts have commented on the profound effects that seeing Earth from space has had on them;[citation needed] the 24 astronauts who traveled to the Moon are the only humans to have observed Earth from beyond low Earth orbit, and have traveled farther from Earth than anyone else to date.

Apollo 11 broadcast data restoration project

As part of Apollo 11's 40th anniversary in 2009, NASA spearheaded an effort to digitally restore the existing videotapes of the mission's live televised moonwalk.[31] After a three-year exhaustive search for missing tapes of the original video of the Apollo 11 moonwalk, NASA concluded the data tapes had more than likely been accidentally erased.[32]

We're all saddened that they're not there. We all wish we had 20-20 hindsight. I don't think anyone in the NASA organization did anything wrong, I think it slipped through the cracks, and nobody's happy about it.

— Dick Nafzger, TV Specialist, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center[32]

The Moon landing data was recorded by a special Apollo TV camera which recorded in a format incompatible with broadcast TV. This resulted in lunar footage that had to be converted for the live television broadcast and stored on magnetic telemetry tapes. During the following years, a magnetic tape shortage prompted NASA to remove massive numbers of magnetic tapes from the National Archives and Records Administration to be recorded over with newer satellite data. Stan Lebar, who designed and built the lunar camera at Westinghouse Electric Corporation, also worked with Nafzger to try to locate the missing tapes.[32]

So I don't believe that the tapes exist today at all. It was a hard thing to accept. But there was just an overwhelming amount of evidence that led us to believe that they just don't exist anymore. And you have to accept reality.

— Stan Lebar, Lunar Camera Designer, Westinghouse Electric Corporation[32]

With a budget of $230,000, the surviving original lunar broadcast data from Apollo 11 was compiled by Nafzger and assigned to Lowry Digital for restoration. The video was processed to remove random noise and camera shake without destroying historical legitimacy.[33] The images were from tapes in Australia, the CBS News archive, and kinescope recordings made at Johnson Space Center. The restored video, remaining in black and white, contains conservative digital enhancements and did not include sound quality improvements.[33]

Documentaries

Numerous documentary films cover the Apollo program and the space race, including:

- Moonwalk One (1970)

- For All Mankind (1989)

- Moon Shot (documentary commemorating 25 years since the landings) (1994)

- From the Earth to the Moon (TV miniseries) (1998)

- Moon from the BBC miniseries The Planets (1999)

- Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D (2005)

- In the Shadow of the Moon (2007)

- When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions (miniseries) (2008)

- James May on the Moon (documentary commemorating 40 years since the landings) (2009)

- NASA's Story

See also

- Apollo 1 - unflown mission

- Apollo 2, Apollo 3, Apollo 4, Apollo 5, Apollo 6 - unmanned missions

- Apollo 18, Apollo 19, Apollo 20 - canceled missions

- Apollo TV camera

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

- List of megaprojects

- Pad Abort Tests

- Soviet Moonshot

- Splashdown (spacecraft landing)

- Lockheed Propulsion Company

Notes

- ^ Kennedy, John F."Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs". jfklibrary.org, May 25, 1961.

- ^ Murray and Cox, Apollo, pp. 16-17.

- ^ 30th Anniversary of Apollo 11, Manned Apollo Missions. NASA, 1999.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood and Swenson, Chariots for Apollo, p. 71.

- ^ a b Hansen, Enchanted Rendezvous, p 21

- ^ Hansen, Enchanted Rendezvous, p. 27.

- ^ Garber, Steve (February 3, 2003). "NASA Apollo Mission Apollo-1 -- Phillips Report". NASA History Office. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Report of the Apollo 204 Review Board, Findings and Recommendations

- ^ Gray, Mike. "Angle of Attack: Harrison Storms and the Race to the Moon", Penguin Books (Non-Classics) (June 1, 1994). ISBN 014023280X

- ^ Chariots for Apollo, Ch 7-4

- ^ Saturn IB News Reference: Saturn IB Design Features

- ^ Saturn V News Reference: First Stage Fact Sheet

- ^ Saturn V News Reference: Second Stage Fact Sheet

- ^ Saturn V News Reference: Third Stage Fact Sheet

- ^ Murray and Cox, Apollo, p. 238.

- ^ Murray and Cox, Apollo, p. 248.

- ^ See Neil Armstrong#First_Moon_walk for more information.

- ^ James Papike, Grahm Ryder, and Charles Shearer (1998). "Lunar Samples". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 36: 5.1–5.234.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burrows, William E. (1999). This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age. Modern Library. p. 431. ISBN 0375754857. OCLC 42136309.

- ^ a b Butts, Glenn; Linton, Kent (April 28, 2009). "The Joint Confidence Level Paradox: A History of Denial, 2009 NASA Cost Symposium" (PDF). pp. 25–26.

- ^ House, Subcommittee on Manned Space Flight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, 1974 NASA Authorization, Hearings on H.R. 4567, 93/2, Part 2, Page 1271.

- ^ a b "The Human Moon". The New York Times. 2009-11-16. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ "The "halo" area around Apollo 15 landing site observed by Terrain Camera on SELENE(KAGUYA)" (Press release). Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 2008-05-20. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ "LRO Sees Apollo Landing Sites". NASA. 2009-07-17. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ "Apollo Landing Sites Revisited". NASA. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ "Rules & Guidelines". X PRIZE Foundation. 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ 30th Anniversary of Apollo 11, NASA, 1999.

- ^ 30th Anniversary of Apollo 11. BBC, 23 July 1999.

- ^ Burrows, William E. (1999). This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age. Modern Library. p. 429. ISBN 0375754857. OCLC 42136309.

- ^ Al Gore (2007-03-17). "An Inconvenient Truth Transcript". Politics Blog - a reproduction of the film's transcript. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/40th/

- ^ a b c d "Houston, We Erased The Apollo 11 Tapes". National Public Radio, July 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Borenstein, Seth for AP. "NASA lost Moon footage, but Hollywood restores it". Yahoo news, July 16, 2009.

References

- "Discussion of Soviet Man-in-Space Shot," Hearing before the Committee on Science and Astronautics, U.S. House of Representatives, 87th Congress, First Session, April 13, 1961.

- Hansen, James R. (1995). Enchanted Rendezvous: John C. Houbolt and the Genesis of the Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous Concept (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- Launius, Roger (1997). Spaceflight and the Myth of Presidential Leadership. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Murray, Charles (1989). Apollo: The Race to the Moon. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-61101-1. OCLC 19589707.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Papike, James (1998). "Lunar Samples". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 36: 5.1–5.234.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sidey, Hugh (1963). John F. Kennedy, President. New York: Atheneum.

- Swenson, Jr., Loyd S. (1979). Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. NASA.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Chaikin, Andrew. A Man on the Moon. ISBN 0-14-027201-1. Chaikin interviewed all the surviving astronauts and others who worked with the program.

- Collins, Michael. Carrying the Fire; an Astronaut's journeys. Astronaut Mike Collins autobiography of his experiences as an astronaut, including his flight aboard Apollo 11

- Cooper, Henry S. F. Jr. Thirteen: The Flight That Failed. ISBN 0-8018-5097-5. Although this book focuses on Apollo 13, it provides a wealth of background information on Apollo technology and procedures.

- French, Francis and Burgess, Colin, In the Shadow of the Moon: A Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965-1969. ISBN 978-0-8032-1128-5. History of the Apollo program from Apollo 1-11, including many interviews with the Apollo astronauts.

- Kranz, Gene, Failure is Not an Option. Factual, from the standpoint of a flight controller during the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo space programs. ISBN 0-7432-0079-9.

- Lovell, Jim; Kluger, Jeffrey. Lost Moon: The perilous voyage of Apollo 13 aka Apollo 13: Lost Moon. ISBN 0-618-05665-3. Details the flight of Apollo 13.

- Orloff, Richard W. SP-4029 Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference

- Pellegrino, Charles R.; Stoff, Joshua. Chariots for Apollo: The Untold Story Behind the Race to the Moon. ISBN 0-380-80261-9. Tells Grumman's story of building the Lunar Modules.

- Robert C. Seamans, Jr. Project Apollo: The Tough Decisions. ISBN 0-1607-4954-9. History of the manned space program from September 1, 1960 to January 5, 1968.

- Slayton, Donald K.; Cassutt, Michael. Deke! An Autobiography. ISBN 0-312-85918-X. Account of Deke Slayton's life as an astronaut and of his work as chief of the astronaut office, including selection of Apollo crews.

- Template:PDFlink From origin to November 7, 1962

- Template:PDFlink November 8, 1962 - September 30, 1964

- Template:PDFlink October 1, 1964 - January 20, 1966

- Template:PDFlink January 21, 1966 - July 13, 1974

- Template:PDFlink

- Wilhelms, Don E. To a Rocky Moon. ISBN 0-8165-1065-2. The history of lunar exploration from a geologist's point of view.

External links

- Official Apollo program website

- Apollo photo gallery at NASA Human Spaceflight website (includes videos/animations)

- Audio recording and transcript of President John F. Kennedy, NASA administrator James Webb et al. discussing the Apollo agenda (White House Cabinet Room, November 21, 1962)

- U.S. Spaceflight History- Apollo Program

- Apollo Image Atlas almost 25,000 lunar images, Lunar and Planetary Institute

- Project Apollo at NASA History Division

- The Apollo Lunar Surface Journal

- How Apollo Has Influenced Society

- The Apollo Flight Journal

- Project Apollo Drawings and Technical Diagrams

- Apollo Program Summary Report (Technical)

- The Apollo Program (National Air and Space Museum)

- Apollo 35th Anniversary Interactive Feature (in Flash)

- Exploring the Moon: Apollo Missions

- Apollo Archive - large repository of information about the Apollo program.

- Apollo Flight Film Archive - repository of scanned Apollo flight film (in high resolution).

- NASA History Series Publications (many of which are on-line)

- Apollo's Contributions to Society

- Was The Apollo Program a Prudent Investment Worth Retrying?

- Hidden Space Project Article about critics on Apollo 11.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA