History of Afghanistan

| History of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

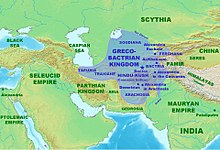

The history of Afghanistan can be linked with the history of Ancient India as part of a sphere. The written history of Afghanistan can be traced back to the Achaemenid Empire ca. 500 BCE,[1][2] although evidence indicates that an advanced degree of urbanized culture has existed in the land between 3000 and 2000 BCE.[3][4][5] Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army arrived to Afghanistan in 330 BCE after conquering Persia.[6] It is the land where many powerful kingdoms established their capitals, including the Greco-Bactrians, Kushans, Indo-Sassanids, Kabul Shahi, Saffarids, Samanids, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Kartids, Timurids, Mughals, Hotakis, and Durranis.[7] On many trade and migration routes, the land of Afghanistan is called the "Central Asian roundabout" since routes converge from the Tigris-Euphrates Basin via the Iranian Plateau, from the Indus Valley through the passes over the Hindu Kush, from the Far East via the Tarim Basin, and from the adjacent Eurasian Steppe.

The Central Asian peoples[5] who are believed to have arrived to Afghanistan after the 20th century BCE[3] left their languages that survived in the form of Pashto and Dari.[1][8] Middle Eastern (Persian and Arab invasions) influenced the culture of Afghanistan, as its Hindu, Zoroastrian, Macedonian and Buddhist past has long since vanished. Local empire-builders such as the Ghaznavids, Ghurids and Timurids made Afghanistan a major medieval power as well as a learning center that produced the likes of Avicenna, and Al-Biruni among many other academic or iconic figures.

Mirwais Hotak followed by Ahmad Shah Durrani unified Afghan tribes and founded the last Afghan Empire in the early 18th century.[9][10][11][12] Afghanistan's sovereignty has been held during the Anglo-Afghan Wars, the 1980s Soviet war, and the 2001-present war by the country's many and diverse people: the Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Aimak, Baloch, and others.

Prehistory

Excavations of prehistoric sites by Louis Dupree and others suggest that early humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago, and that farming communities in Afghanistan were among the earliest in the world.[5]

Archaeologists have found evidence of human habitation in Afghanistan from as far back as 50,000 BCE. The artifacts indicate that the indigenous people were small farmers and herdsmen, as they are today, very probably grouped into tribes, with small local kingdoms rising and falling through the ages.[1]

Urbanization may have begun as early as 3000 BCE.[13] Zoroastrianism predominated as the religion in the area, even the modern Afghan solar calendar shows the influence of Zoroastrianism in the names of the months.[1] Other religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism arrived later to the region. Gandhara is the name of an ancient Hindu kingdom from the Vedic period and its capital city located between the Hindukush and Sulaiman Mountains (mountains of Solomon),[14] although Kandahar in modern times and the ancient Gandhara are not geographically identical.[15][16]

Early inhabitants, around 3000 BCE were likely to have been connected through culture and trade to neighboring civilizations like Jiroft and Tappeh Sialk and more distantly to the Indus Valley Civilization. Urban civilization may have begun as early as 3000 BCE, and it is possible that the early city of Mundigak (near Kandahar) was a colony of the nearby Indus Valley Civilization.[4] The first known people were Indo-Iranians,[5] but their date of arrival has been estimated widely from as early as about 3000 BCE[17] to 1500 BCE.[18] (For further detail see Indo-Aryan migration.)

Bactria-Margiana

The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex became prominent in the southwest region between 2200 and 1700 BCE (approximately). The city of Balkh (Bactra) was founded about this time (c. 2000–1500 BCE). It's possible that the BMAC may have been an Indo-European culture, perhaps the Proto-Indo-Aryans.[17] But the standard model holds the arrival of Indo-Aryans to have been in the Late Harappan which gave rise to the Vedic civilization of the Early Iron Age.[19]

Ancient history (700 BC - 565 AD)

Medes

Different opinions have been expressed about the extent of the Median kingdom. For instance, according to Ernst Herzfeld, it was a powerful empire, which stretched from north Mesopotamia to Bactria and India. On the other side, Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg insists that there is no real evidence about the very existence of the Median empire and that it was an unstable state formation.[20]

Achaemenid Empire

Afghanistan became part of the Achaemenid Empire, after it was conquered by Darius I of Persia. The area was divided into several provinces called satrapies, which were each ruled by a governor, or satrap. These ancient satrapies included: Aria (Herat); Arachosia (Kandahar, Lashkar Gah, and Quetta); Bactriana (Balkh); Sattagydia (Ghazni); and Gandhara (Kabul, Jalalabad, Peshawar).[21]

Alexander and the Seleucids

Alexander the Great arrived in the area of Afghanistan in 330 BCE after defeating Darius III of Persia a year earlier at the Battle of Gaugamela.[22] His army faced very strong resistance in the Afghan tribal areas where he is said to have commented that Afghanistan is "easy to march into, hard to march out of."[1] Although his expedition through Afghanistan was brief, Alexander left behind a Hellenic cultural influence that lasted several centuries. Several great cities were built in the region named "Alexandria," including: Alexandria-of-the-Arians (modern-day Herat); Alexandria-on-the-Tarnak (near Kandahar); Alexandria-ad-Caucasum (near Begram, at Bordj-i-Abdullah); and finally, Alexandria-Eschate (near Kojend), in the north. After Alexander's death, his loosely connected empire was divided. Seleucus, a Macedonian officer during Alexander's campaign, declared himself ruler of his own Seleucid Empire, encompassing Persia and Afghanistan.[23]

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was founded when Diodotus I, the satrap of Bactria (and probably the surrounding provinces) seceded from the Seleucid Empire around 250 BC. Greco-Bactria continued until c. 130 BCE, when Eucratides' son, King Heliocles I, was defeated and driven out of Bactria by the Yuezhi tribes. It is thought that his dynasty continued to rule in Kabul and Alexandria of the Caucasus until 70 BCE when King Hermaeus was defeated by the Yuezhi.

One of Demetrius' successors, Menander I, brought the Indo-Greek Kingdom to its height between 165–130 BCE, expanding the kingdom in India to even larger proportions than Demetrius. After Menander's death, the Indo-Greeks steadily declined and the last Indo-Greek king was defeated in c. 10 CE.

Mauryan Empire

Modern day Afghanistan was conquered by the Maurya Empire, which was led by Chandragupta Maurya from Magadha(modern day Bihar in India). They were Indians who practiced Hinduism and Buddhism and were focusing on taking over Central Asia. Seleucus is said to have reach a peace treaty with Chandragupta by given control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush to the Mauryas upon intermarriage and 500 elephants.

Alexander took these away from the Indo-Aryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.[24]

— Strabo, 64 BC–24 AD

Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India, when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness; who, after making a league with him, and settling his affairs in the east, proceeded to join in the war against Antigonus. As soon as the forces, therefore, of all the confederates were united, a battle was fought, in which Antigonus was slain, and his son Demetrius put to flight.[25]

Having consolidated power in the northwest, Chandragupta pushed east towards the Nanda Empire. Afghanistan's significant ancient tangible and intangible Buddhist heritage is recorded through wide-ranging archeological finds, including religious and artistic remnants. Buddhist doctrines are reported to have reached as far as Balkh even during the life of the Buddha (563 BCE to 483 BCE), as recorded by Husang Tsang.

In this context a legend recorded by Husang Tsang refers to the first two lay disciples of Buddha, Trapusa and Bhallika responsible for introducing Buddhism in that country. Originally these two were merchants of the kingdom of Balhika, as the name Bhalluka or Bhallika probably suggests the association of one with that country. They had gone to India for trade and had happened to be at Bodhgaya when the Buddha had just attained enlightenment.[26]

Sakas

Parthians

Kushans

Sassanids

Kidarites

Hephthalites (White Huns)

The Hephthalite Empire in Afghanistan extended from Chinese Sinkiang to Sassanid Iran, from Sogdiana to the Punjab. Their chief antagonists were the Sassanids. Consequently there was relatively little peace during this time. At about 565 AD, the Hephthalite Empire was overthrown by a combined force consisting of western Turks and Sassanids.[27]

Middle Ages (565–1504 AD)

From the Middle Ages to around 1750 part of today's Afghanistan was recognized as Khorasan.[28] Two of the four main capitals of Khorasan (Balkh and Herat) are now located in modern Afghanistan. The country of Kandahar, Ghazni and Kabul formed the frontier region between Khorasan and Hindustan.[29] The land inhabited by the Afghan tribes (i.e. ancestors of Pashtuns) was called Afghanistan, which loosely covered a wide area between the Hindu Kush and the Indus River, principally around the Sulaiman Mountains.[30][31] The earliest record of the name "Afghan" ("Abgân") being mentioned is by Shapur I of the Sassanid Empire during the 3rd century CE[32][33][34] which is later recorded in the form of "Avagānā" by the Indian astronomer Varāha Mihira in his 6th century CE Brihat-samhita.[35] It was used to refer to a common legendary ancestor known as "Afghana", grandson of King Saul of Israel.[36][37][38] Hiven Tsiang, a Chinese pilgrim, visiting the Afghanistan area several times between 630 to 644 CE also speaks about them.[32][39] Ancestors of many of today's Turkic-speaking Afghans settled in the Hindu Kush area and began to assimilate much of the culture and language of the Pashtun tribes already present there.[40] Among these were the Khalaj people which are known today as Ghilzai.[41]

Kabul Shahi

Palas

The Pāla's were a Buddhist and Vaishnav Hindu Bengali dynasty of India, which lasted for four centuries (750-1120 AD). Dharmapala extended the empire into the northern parts of the Indian Subcontinent. This triggered once again the power struggle for the control of the subcontinent. Devapala, successor of Dharmapala, expanded the empire to cover much of South Asia and beyond. His empire stretched from Assam and Utkala in the east, and modern day Afghanistan in the north-west and Deccan in the south. According to Pala copperplate inscription Devapala exterminated the Utkalas, conquered the Pragjyotisha (Assam), shattered the pride of the Huna, and humbled the lords of Pratiharas, Gurjara and the Dravidas. The Pala Empire eventually disintegrated in the 12th century under the attack of the Sena dynasty.

Islamic conquest

In 642 CE, Arabs had conquered most of Persia and then invaded Afghanistan from the western city of Herat, introducing the religion of Islam as they entered new cities. Afghanistan at that period had a number of different independent rulers, depending on the area.

The early Arab forces did not fully explore Afghanistan due to attacks by the mountain tribes. Much of the eastern parts of the country remained independent, as part of the Turk Shahi kingdoms of Kabul and Gandhara, which lasted that way until the forces of the Muslim Saffarid dynasty followed by the Ghaznavids conquered them.

Arab armies carrying the banner of Islam came out of the west to defeat the Sasanians in 642 CE and then they marched with confidence to the east. On the western periphery of the Afghan area the princes of Herat and Seistan gave way to rule by Arab governors but in the east, in the mountains, cities submitted only to rise in revolt and the hastily converted returned to their old beliefs once the armies passed. The harshness and avariciousness of Arab rule produced such unrest, however, that once the waning power of the Caliphate became apparent, native rulers once again established themselves independent. Among these the Saffarids of Seistan shone briefly in the Afghan area. The fanatic founder of this dynasty, the coppersmith's apprentice Yaqub ibn Layth Saffari, came forth from his capital at Zaranj in 870 CE and marched through Bost, Kandahar, Ghazni, Kabul, Bamyan, Balkh and Herat, conquering in the name of Islam.[4]

— Nancy Hatch Dupree, 1971

The Shahi or Shahiya dynasties ruled portions of the Kabul Valley (in eastern Afghanistan) and the old province of Gandhara (northern Pakistan and Kashmir) from the decline of the Kushan Empire up to the early 9th century. The Shahis continued to rule eastern Afghanistan until the late 9th century until the Ghaznavid invasions.

During the eighth and ninth centuries CE the eastern parts of modern Afghanistan were still in the hands of non-muslim rulers. The Muslims tended to regard them as Indians, although many of the local rulers were apparently of Hunnish or Turkic descent. Yet, the Muslims were right in so far as the non Muslim population of Eastern Afghanistan was, culturally, strongly linked to the Indian sub-continent. Most of them were either Buddhists or they worshipped Hindu deities.[42]

Janjau Rajput Empire (900-1050 AD)

Jaypala was the most powerful ruler of this empire rule over Afghanistan, Pakistan and Jammu & Kasmir. He was eventually defeated by Ghazni and lost his empire.

Ghaznavids

Mahmud of Ghazni consolidated the conquests of his predecessors and turned the city of Ghazni into a great cultural center as well as a base for frequent forays into the Indian subcontinent.

Ghorids

The Ghaznavid dynasty was defeated in 1148 by the Ghurids from Ghor, but the Ghaznavid Sultans continued to live in Ghazni as the 'Nasher' until the early 20th century. They did not regain their once vast power until about 500 years later when the Ghilzai Hotakis rose to power. Various princes and Seljuk rulers attempted to rule parts of the country until the Shah Muhammad II of the Khwarezmid Empire conquered all of Persia in 1205. By 1219, the empire had fallen to the Mongols, led by Genghis Khan.

Mongol invasion

The Mongols resulted in massive destruction of many cities, including Bamiyan, Herat, and Balkh, and the despoliation of fertile agricultural areas. Large number of the inhabitant were also slaughtered. All the major cities and towns became part of the massive Mongol Empire, except the isolated hidden mountainous southern regions where the mountain tribes lived.

Timurids

Timur (Tamerlane), incorporated what is today Afghanistan into his own vast Timurid Empire. The city of Herat became one of the capitals of his empire, and his grandson Pir Muhammad held the seat of Kandahar. Timur rebuilt most of Afghanistan's infrastructure which was destroyed by his early ancestor. The area was progressing under his rule. Timurid rule began declining in the early 16th century with the rise of a new ruler in Kabul, Babur.

Modern era (1504-1973)

Mughals and Safavids

In 1504 Babur, a descendant of Timur, arrived from what is now Uzbekistan and captured the city of Kabul. He began exploring new territories in the region, with Kabul serving as his military headquarters. Instead of looking towards Persia, Babur was more focused on the Indian subcontinent, which included the region known as Kabulistan. In 1526, he left with his army to capture the seat of the Delhi Sultanate, which at that point was possessed by the Afghan Lodi dynasty of India. After defeating Ibrahim Lodi and his army, Babur turned Delhi into the capital of his newly established Mughal Empire.

From the 16th century to the early 18th century, Afghanistan was divided in to three major areas. The north was ruled by Khanate of Bukhara, the west was under the Shi'a Safavid rule and the east belonged to the Sunni Mughals of India. The Kandahar region in the south served as a buffer zone between the powerful Mughals and Safavids, and the native Afghans often switched support from one side to the other. Babur explored most cities of Afghanistan before his campaign into India. In the city of Kandahar his personal epigraphy can be found in the Chilzina rock mountain.

Hotaki dynasty

In 1704, the Safavid Shah Hossein appointed George XI (Gurgīn Khān), a ruthless Christian of Georgian origin, to govern the Greater Kandahar region of Afghanistan. Gurgīn began imprisoning and executing many of the native Afghans, especially those suspected of organizing a rebellion. One of those arrested and imprisoned was Mirwais Hotak who belonged to an influential family in Kandahar. Mirwais was sent as a prisoner to the Persian court in Isfahan but the charges against him were dismissed by the king, so he was sent back to his native land as a free man.[43]

In April of 1709, Mirwais along with his tribal army revolted against Gurgīn and the Safavids in Kandahar City. The uprising began when Gurgīn and his escort were killed after a picnic and a banquet that were prepared by Mirwais at his farmhouse outside the city. It is reported that heavy drinking of alcohol was involved. Soon after killing Gurgīn and the Safavid forces, Mirwais entered Kandahar and made a speech to the town dwellers.

"If there are any amongst you, who have not the courage to enjoy this precious gift of liberty now dropped down to you from Heaven, let him declare himself; no harm shall be done to him: he shall be permitted to go in search of some new tyrant beyond the frontier of this happy state."[44]

— Mirwais Hotak, April 1709

Around four days later, an army of well-trained Georgian troops arrived to the town after hearing of Gurgīn's death but Mirwais and his Afghan forces successfully held off the town. From 1710 to 1713, the Afghan forces defeated several large and powerful Persian armies that were dispatched from Isfahan (capital of the Safavids), which included Qizilbash and Georgian troops.[45]

Several half-hearted attempts to subdue the rebellious city having failed, the Persian Government despatched Khusraw Khán, nephew of the late Gurgín Khán, with an army of 30,000 men to effect its subjugation, but in spite of an initial success, which led the Afgháns to offer to surrender on terms, his uncompromising attitude impelled them to make a fresh desperate effort, resulting in the complete defeat of the Persian army (of whom only some 700 escaped) and the death of their general. Two years later, in A.D. 1713, another Persian army commanded by Rustam Khán was also defeated by the rebels, who thus secured possession of the whole province of Qandahár.[46]

— Edward G. Browne, 1924

The Persian armies were completely defeated and southern Afghanistan was made into an independent local Pashtun kingdom.[12] Refusing the title of a king, Mirwais was called "Prince of Qandahár and General of the national troops" by his Afghan countrymen. He died of a natural cause in November 1715 and was succeeded by his brother Abdul Aziz Hotak. Aziz was killed about two years later by Mirwais' son Mahmud Hotaki, allegedly for planning to give Kandahar's sovereignty back to Persia.[47] Mahmud led an Afghan army into Persia in 1722 and defeated the Persian army at the Battle of Gulnabad. The Afghans captured Isfahan (Safavid capital) and Mahmud became the new Persian Shah, known after that as Shah Mahmud.

Seven months elapsed after the battle of Gulnábád before the final pitiful surrender, with every circumstance of humiliation, of the unhappy Sháh Ḥusayn. In that battle the Persians are said to have lost all their artillery, baggage and treasure, as well as some 15,000 out of a total of 50,000 men. On March 19 Mír Maḥmúd occupied the Sháh's beloved palace and pleasure-grounds of Faraḥábád, situated only three miles from Iṣfahán, which henceforth served as his headquarters. Two days later the Afgháns, having occupied the Armenian suburb of Julfá, where they levied a tribute of money and young girls, attempted to take Iṣfahán by storm, but, having twice failed (on March 19 and 21), sat down to blockade the city. Three months later Prince Ṭahmásp Mírzá, who had been nominated to succeed his father, effected his escape from the beleaguered city to Qazwín, where he attempted, with but small success, to raise an army for the relief of the capital.[48]

— Edward G. Browne, 1924

Mahmud began a reign of terror against his Persian subjects and was eventually murdered in 1725 by his cousin, Ashraf Hotaki. Some sources say he died of madness. Ashraf became the new Afghan Shah of Persia soon after Mahmud's death, while the home region of Afghanistan was ruled by Mahmud's younger brother Shah Hussain Hotaki. Ashraf was able to secure peace with the Ottoman Empire in 1727, but the Russian Empire took advantage of the political unrest in Persia to seize land for themselves, limiting the amount of territory under Shah Mahmud's control.

The Hotaki dynasty was a troubled and violent one as internecine conflict made it difficult to establish permanent control. The dynasty lived under great turmoil due to bloody succession feuds that made their hold on power tenuous, and after the massacre of thousands of civilians in Isfahan; including more than three thousand religious scholars, nobles, and members of the Safavid family.[49] The majority Persians rejected the Afghan regime as usurping. For the next 7 years the Hotakis became the de facto rulers of Persia, but their rule continued in the region of Afghanistan until 1738 when Shah Hussain was defeated.

The Ghilzai Hotakis were eventually removed from power in what is now Iran by 1730. They were defeated by Nader Shah, head of the Afsharids, in the October 1729 Battle of Damghan and pushed from what is now Iran to the southern Afghan region. The last ruler of the Hotaki dynasty, Shah Hussain, ruled southern Afghanistan until 1738 when the Afsharids and the Abdali Pashtuns defeated him at Kandahar.[50]

Durrani Empire

Nader Shah and his Afsharid army arrived to the town of Kandahar in 1738 and defeated Hussain Hotaki. The young teenager Ahmad Khan, who would later become ruler of the Durrani Empire, was held a prisoner at the Hotaki fortress but was released by Nader Shah. Ahmad Khan joined the Afsharid military, and in the same year they left Kandahar to invade the Mughal Empire. They occupied Ghazni, Kabul, Peshawar, and Lahore. They reached all the way to Delhi and sacked the city, taking the Koh-i-Noor diamond and many other treasures with them to Greater Khorasan.

Nadir Shah was assassinated on June 19, 1747, by several of his Persian officers and the Asharid kingdom fell to pieces. While the Persians were contesting each others in Iran, the 25 year old Ahmad Khan was busy in Afghanistan calling for a loya jirga ("grand assembly") to select a leader among his people. The Afghans gathered near Kandahar in October 1747 and chose Ahmad Shah among the challengers, making him their new head of state. After the inauguration or coronation, he became known as Ahmad Shah Durrani. He adopted the title padshah durr-i dawran ('King, "pearl of the age") and the Abdali tribe became known as the Durrani tribe after this.[51] Ahmad Shah not only represented the Durranis but he also united all the Pashtun tribes. By 1751, Ahmad Shah Durrani and his Afghan army conquered the entire present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, Khorasan and Kohistan provinces of Iran, along with Delhi in India.[52] He defeated the Maratha Empire in one of the biggest battles that was known as 1761 Battle of Panipat.

In October 1772, Ahmad Shah retired to his home in Kandahar where he died peacefully and was buried at a site that is now adjacent to the Mosque of the Cloak of the Prophet Mohammed. He was succeeded by his son, Timur Shah Durrani, who transferred the capital of their Afghan Empire from Kandahar to Kabul. Timur died in 1793 and his son Zaman Shah Durrani took over the reign.

Zaman Shah and his brothers had a weak hold on the legacy left to them by their famous ancestor. They sorted out their differences through a "round robin of expulsions, blindings and executions," which resulted in the deterioration of the Afghan hold over far-flung territories, such as Attock and Kashmir. Durrani's other grandson, Shuja Shah Durrani, fled the wrath of his brother and sought refuge with the Sikhs. Not only had Durrani invaded the Punjab

British invasion and Barakzai dynasty

Dost Mohammed Khan gained control in Kabul. Collision between the expanding British and Russian Empires significantly influenced Afghanistan during the 19th century in what was termed "The Great Game". British concern over Russian advances in Central Asia and growing influence in Persia culminated in two Anglo-Afghan wars and "The Siege of Herat" 1837–1838, in which the Persians, trying to retake Afghanistan and throw out the British and Russians, sent armies into the country and fought the British mostly around and in the city of Herat. The first (1839–1842) resulted in the destruction of a British army; it is remembered as an example of the ferocity of Afghan resistance to foreign rule. The second Anglo-Afghan war (1878–1880) was sparked by Amir Shir Ali's refusal to accept a British mission in Kabul. This conflict brought Amir Abdur Rahman to the Afghan throne. During his reign (1880–1901), the British and Russians officially established the boundaries of what would become modern Afghanistan. The British retained effective control over Kabul's foreign affairs.

Afghanistan remained neutral during World War I, despite German encouragement of anti-British feelings and Afghan rebellion along the borders of British India. The Afghan king's policy of neutrality was not universally popular within the country, however.

Habibullah, Abdur Rahman's son and successor, was assassinated in 1919, possibly by family members opposed to British influence. His third son, Amanullah, regained control of Afghanistan's foreign policy after launching the Third Anglo-Afghan war with an attack on India in the same year. During the ensuing conflict, the war-weary British relinquished their control over Afghan foreign affairs by signing the Treaty of Rawalpindi in August 1919. In commemoration of this event, Afghans celebrate August 19 as their Independence Day.

Reforms of Amanullah Khan and civil war

King Amanullah Khan moved to end his country's traditional isolation in the years following the Third Anglo-Afghan war. He established diplomatic relations with most major countries and, following a 1927 tour of Europe and Turkey (during which he noted the modernization and secularization advanced by Atatürk), introduced several reforms intended to modernize Afghanistan. A key force behind these reforms was Mahmud Tarzi, Amanullah Khan's Foreign Minister and father-in-law — and an ardent supporter of the education of women. He fought for Article 68 of Afghanistan's first constitution (declared through a Loya Jirga), which made elementary education compulsory.[53] Some of the reforms that were actually put in place, such as the abolition of the traditional Muslim veil for women and the opening of a number of co-educational schools, quickly alienated many tribal and religious leaders. Faced with overwhelming armed opposition, Amanullah was forced to abdicate in January 1929 after Kabul fell to forces led by Habibullah Kalakani.

Reigns of Nadir Shah and Zahir Shah

Prince Mohammed Nadir Khan, cousin of Amanullah Khan, in turn defeated and executed Habibullah Kalakani in early November 1929. He was soon declared King Nadir Khan. He began consolidating power and regenerating the country. He abandoned the reforms of Amanullah Khan in favour of a more gradual approach to modernisation. In 1933, however, he was assassinated in a revenge killing by a student from Kabul.

Mohammad Zahir Shah, Nadir Khan's 19-year-old son, succeeded to the throne and reigned from 1933 to 1973. Until 1946 Zahir Shah ruled with the assistance of his uncle Sardar Mohammad Hashim Khan, who held the post of Prime Minister and continued the policies of Nadir Shah. In 1946, another of Zahir Shah's uncles, Sardar Shah Mahmud Khan, became Prime Minister and began an experiment allowing greater political freedom, but reversed the policy when it went further than he expected. In 1953, he was replaced as Prime Minister by Mohammed Daoud Khan, the king's cousin and brother-in-law. Daoud sought a closer relationship with the Soviet Union and a more distant one towards Pakistan. However, disputes with Pakistan led to an economic crisis and he was asked to resign in 1963. From 1963 until 1973, Zahir Shah took a more active role.

In 1964, King Zahir Shah promulgated a liberal constitution providing for a bicameral legislature to which the king appointed one-third of the deputies. The people elected another third, and the remainder were selected indirectly by provincial assemblies. Although Zahir's "experiment in democracy" produced few lasting reforms, it permitted the growth of unofficial extremist parties on both the left and the right. These included the communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), which had close ideological ties to the Soviet Union. In 1967, the PDPA split into two major rival factions: the Khalq (Masses) was headed by Nur Muhammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin who were supported by elements within the military, and the Parcham (Banner) led by Babrak Karmal.

Contemporary era (1973-present)

Republic of Afghanistan and the end of monarchy

Amid charges of corruption and malfeasance against the royal family and poor economic conditions created by the severe 1971–72 drought, former Prime Minister Mohammad Sardar Daoud Khan seized power in a non-violent coup on July 17, 1973, while Zahir Shah was receiving treatment for eye problems and therapy for lumbago in Italy.[54] Daoud abolished the monarchy, abrogated the 1964 constitution, and declared Afghanistan a republic with himself as its first President and Prime Minister. His attempts to carry out badly needed economic and social reforms met with little success, and the new constitution promulgated in February 1977 failed to quell chronic political instability.

As disillusionment set in, in 1978 a prominent member of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), Mir Akbar Khyber (or "Kaibar"), was killed by the government. The leaders of PDPA apparently feared that Daoud was planning to exterminate them all, especially since most of them were arrested by the government shortly after. Nonetheless, Hafizullah Amin and a number of military wing officers of the PDPA's Khalq faction managed to remain at large and organize a military coup.

Democratic Republic and Soviet invasion

On 27 April 1978, the PDPA, led by Nur Mohammad Taraki, Babrak Karmal and Amin Taha overthrew the government of Mohammad Daoud, who was assassinated along with all his family members in a bloody military coup. The coup became known as the Saur Revolution. On 1 May, Taraki became President, Prime Minister and General Secretary of the PDPA. The country was then renamed the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA), and the PDPA regime lasted, in some form or another, until April 1992.

In March 1979, Hafizullah Amin took over as prime minister, retaining the position of field marshal and becoming vice-president of the Supreme Defence Council. Taraki remained President and in control of the Army. On 14 September, Amin overthrew Taraki, who was killed. Amin stated that "the Afghans recognize only crude force."[55] Afghanistan expert Amin Saikal writes: "As his powers grew, so apparently did his gravings for personal dictatorship ... and his vision of the revolutionary process based on terror."[55]

Once in power, the PDPA implemented a liberal and marxist-leninist agenda. It moved to replace religious and traditional laws with secular and marxist-leninist ones. Men were obliged to cut their beards, women could not wear a chador, and mosques were placed off limits. The PDPA made a number of reforms on women's rights, banning forced marriages, giving state recognition of women's right to vote, and introducing women to political life. A prominent example was Anahita Ratebzad, who was a major Marxist leader and a member of the Revolutionary Council. Ratebzad wrote the famous New Kabul Times editorial (May 28, 1978) which declared: "Privileges which women, by right, must have are equal education, job security, health services, and free time to rear a healthy generation for building the future of the country ... Educating and enlightening women is now the subject of close government attention." But the PDPA also carried out socialist land reforms. It moved to promote state atheism,[56] and carried out an ill-conceived land reform, which was misunderstood by virtually all Afghans.[57] They also prohibited usury[58] and took a number of measures in favor of women's rights, by declaring equality of the sexes[58] and introducing women to political life. Anahita Ratebzad was one of several female Marxist leaders and a member of the Revolutionary Council. The PDPA invited the Soviet Union to assist in modernizing its economic infrastructure (predominantly its exploration and mining of rare minerals and natural gas). The USSR also sent contractors to build roads, hospitals and schools and to drill water wells; they also trained and equipped the Afghan army. Upon the PDPA's ascension to power, and the establishment of the DRA, the Soviet Union promised monetary aid amounting to at least $1.262 billion.

At the same time, the PDPA imprisoned, tortured or murdered thousands of members of the traditional elite, the religious establishment, and the intelligentsia.[57] Human Rights Watch estimates that as many as 100,000 people may have been killed in the countryside alone by government troops[citation needed]. Members of the academia and ethnic minorities[citation needed] were killed, tortured or imprisoned. In December 1978 the PDPA leadership signed an agreement with the Soviet Union which would allow military support for the PDPA in Afghanistan if needed. The majority of people in the cities including Kabul either welcomed or were ambivalent to these policies. However, the Marxist-leninist and secular nature of the government as well as its heavy dependence on the Soviet Union made it unpopular with a majority of the Afghan population. Repressions plunged large parts of the country, especially the rural areas, into open revolt against the new Marxist-leninist government. By spring 1979 unrests had reached 24 out of 28 Afghan provinces including major urban areas. Over half of the Afghan army would either desert or join the insurrection.

The United States saw the situation as a prime opportunity to weaken the Soviet Union. As part of a Cold War strategy, in 1979 the United States government (under President Jimmy Carter and National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski) began to covertly fund and train anti-government Mujahideen forces through the Pakistani secret service known as Inter Services Intelligence (ISI).

To bolster the Parcham faction, the Soviet Union decided to intervene on December 24, 1979, when the Red Army invaded its southern neighbor. Over 100,000 Soviet troops took part in the invasion, which was backed by another one hundred thousand Afghan military men and supporters of the Parcham faction. In the meantime, Hafizullah Amin was killed and replaced by Babrak Karmal. In response to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the Reagan administration in the U.S. increased arming and funding of the Mujahideen who began a guerilla war thanks in large part to the efforts of Charlie Wilson and CIA officer Gust Avrakotos. Early reports estimated that $6–20 billion had been spent by the U.S. and Saudi Arabia[59] but more recent reports state that the U.S. and Saudi Arabia provided as much as up to $40 billion[60][61][62] in cash and weapons, which included over two thousand FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missiles, for building up Islamic groups against the Soviet Union. The U.S. handled most of its support through Pakistan's ISI. Saudi Arabia was also providing financial support. Leaders such as Ahmad Shah Massoud received only minor aid compared to Hekmatyar and some of the other parties, although Massoud was named the "Afghan who won the cold war" by the Wall Street Journal.[63]

The 10-year Soviet occupation resulted in the killings of between 600,000 and two million Afghans, mostly civilians.[64] About 6 million fled as Afghan refugees to Pakistan and Iran, and from there over 38,000 made it to the United States[65] and many more to the European Union. Faced with mounting international pressure and great number of casualties on both sides, the Soviets withdrew in 1989. Their withdrawal from Afghanistan was seen as an ideological victory in America, which had backed some Mujahideen factions through three U.S. presidential administrations to counter Soviet influence in the vicinity of the oil-rich Persian Gulf. The USSR continued to support President Mohammad Najibullah (former head of the Afghan secret service, KHAD) until 1992.[66]

Islamic State, foreign interference and civil war

1992-1996

After the fall of the communist Najibullah-regime in 1992, the Afghan political parties agreed on a peace and power-sharing agreement (the Peshawar Accords). The Peshawar Accords created the Islamic State of Afghanistan and appointed an interim government for a transitional period. According to Human Rights Watch:

The sovereignty of Afghanistan was vested formally in the Islamic State of Afghanistan, an entity created in April 1992, after the fall of the Soviet-backed Najibullah government. [...] With the exception of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, all of the parties [...] were ostensibly unified under this government in April 1992. [...] Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, for its part, refused to recognize the government for most of the period discussed in this report and launched attacks against government forces and Kabul generally. [...] Shells and rockets fell everywhere.[67]

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was directed, funded and supplied by the Pakistani army.[68] Afghanistan analyst Amin Saikal concludes in his book Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival:

Pakistan was keen to gear up for a breakthrough in Central Asia. [...] Islamabad could not possibly expect the new Islamic government leaders [...] to subordinate their own nationalist objectives in order to help Pakistan realize its regional ambitions. [...] Had it not been for the ISI's logistic support and supply of a large number of rockets, Hekmatyar's forces would not have been able to target and destroy half of Kabul.[55]

There was no time for the interim government to create working government departments, police units or a system of justice and accountability. Saudi Arabia and Iran also armed and directed Afghan militias.[55] A publication by the George Washington University describes:

[O]utside forces saw instability in Afghanistan as an opportunity to press their own security and political agendas.[69]

According to Human Rights Watch, numerous Iranian agents were assisting the Shia Hezb-i Wahdat forces of Abdul Ali Mazari, as Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat's military power and influence.[55][67][70] Saudi Arabia was trying to strengthen the Wahhabite Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittihad-i Islami faction.[55][67] Atrocities were committed by individuals of the different factions while Kabul descended into lawlessness and chaos as described in reports by Human Rights Watch and the Afghanistan Justice Project.[67][71] Again, Human Rights Watch writes:

Rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by representatives of Ahmad Shah Massoud, Sibghatullah Mojaddedi or Burhanuddin Rabbani (the interim government), or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days.[67]

The main forces involved during that period in Kabul, northern, central and eastern Afghanistan were the Hezb-i Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar directed by Pakistan, the Hezb-i Wahdat of Abdul Ali Mazari directed by Iran, the Ittehad-i Islami of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf supported by Saudi Arabia, the Junbish-i Milli of Abdul Rashid Dostum backed by Uzbekisten, the Harakat-i Islami of Hussain Anwari and the Shura-i Nazar operating as the regular Islamic State forces (as agreed upon in the Peshawar Accords) under the defense ministry of Ahmad Shah Massoud.

Meanwhile southern Afghanistan was neither under the control of foreign-backed militias nor the interim government in Kabul, which had no hands in the affairs of southern Afghanistan during that time. Southern Afghanistan was ruled by Gul Agha Sherzai. The southern city of Kandahar was a centre of lawlessness, crime and atrocities fuelled by complex Pashtun tribal rivalries.[72] In 1994, the Taliban (a movement originating from Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-run religious schools for Afghan refugees in Pakistan) also developed in Afghanistan as a politico-religious force, reportedly in opposition to the tyranny of the local governor.[72] Mullah Omar started his movement with fewer than 50 armed madrassah students in his hometown of Kandahar.[72] As Gulbuddin Hekmatyar remained unsuccessful in conquering Kabul, Pakistan started its support to the Taliban.[55][73] Many analyst like Amin Saikal describe the Taliban as developing into a proxy force for Pakistan's regional interests which the Taliban decline.[55] In 1994 the Taliban took power in several provinces in southern and central Afghanistan.

In 1995 the Hezb-i Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the Iranian-backed Hezb-i Wahdat as well as Rashid Dostum's Junbish forces were defeated militarily in the capital Kabul by forces of the interim government under Massoud who subsequently tried to initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation and democratic elections, also inviting the Taliban to join the process.[74] The Taliban declined.[74]

Taliban and United Front

1996-2001

The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995 but were defeated by forces of the Islamic State government under Ahmad Shah Massoud.[75] Amnesty International, referring to the Taliban offensive, wrote in a 1995 report:

This is the first time in several months that Kabul civilians have become the targets of rocket attacks and shelling aimed at residential areas in the city.[75]

On September 26, 1996, as the Taliban with military support by Pakistan and financial support by Saudi Arabia prepared for another major offensive Massoud ordered a full retreat from Kabul.[76] The Taliban seized Kabul on September 27, 1996, and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. They imposed on the parts of Afghanistan under their control their political and judicial interpretation of Islam issuing edicts forbidding women to work outside the home, attend school, or to leave their homes unless accompanied by a male relative.[77] The Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) analyze:

To PHR's knowledge, no other regime in the world has methodically and violently forced half of its population into virtual house arrest, prohibiting them on pain of physical punishment.[77]

After the fall of Kabul to the Taliban on September 27, 1996,[78] Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum, two former archnemesis, created the United Front (Northern Alliance) against the Taliban that were preparing offensives against the remaining areas under the control of Massoud and those under the control of Dostum. see video The United Front included beside the dominantly Tajik forces of Massoud and the Uzbek forces of Dostum, Hazara factions and Pashtun forces under the leadership of commanders such as Abdul Haq, Haji Abdul Qadir, Qari Baba or diplomat Abdul Rahim Ghafoorzai. From the Taliban conquest in 1996 until November 2001 the United Front controlled roughly 30% of Afghanistan's population in provinces such as Badakhshan, Kapisa, Takhar and parts of Parwan, Kunar, Nuristan, Laghman, Samangan, Kunduz, Ghōr and Bamyan.

According to a 55-page report by the United Nations, the Taliban, while trying to consolidate control over northern and western Afghanistan, committed systematic massacres against civilians.[79][80] UN officials stated that there had been "15 massacres" between 1996 and 2001.[79][80] They also said, that "[t]hese have been highly systematic and they all lead back to the [Taliban] Ministry of Defense or to Mullah Omar himself."[79][80] The Taliban especially targeted people of Shia religious or Hazara ethnic background.[79][80] Upon taking Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998, about 4,000 civilians were executed by the Taliban and many more reported tortured.[81][82] Among those killed in Mazari Sharif were several Iranian diplomats. Others were kidnapped by the Taliban, touching off a hostage crisis that nearly escalated to a full scale war, with 150,000 Iranian soldiers massed on the Afghan border at one time.[83] It was later admitted that the diplomats were killed by the Taliban, and their bodies were returned to Iran.[84]

The documents also reveal the role of Arab and Pakistani support troops in these killings.[79][80] Bin Laden's so-called 055 Brigade was responsible for mass-killings of Afghan civilians.[85] The report by the United Nations quotes eyewitnesses in many villages describing Arab fighters carrying long knives used for slitting throats and skinning people.[79][80]

Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf - then as Chief of Army Staff - was responsible for sending thousands of Pakistanis to fight alongside the Taliban and Bin Laden against the forces of Massoud.[73][74][86][87] In total there were believed to be 28,000 Pakistani nationals fighting inside Afghanistan.[74] 20,000 were regular Pakistani soldiers either from the Frontier Corps or army and an estimated 8,000 were militants recruited in madrassas filling regular Taliban ranks.[85] The estimated 25,000 Taliban regular force thus comprised more than 8,000 Pakistani nationals.[85] A 1998 document by the U.S. State Department confirms that "20-40 percent of [regular] Taliban soldiers are Pakistani."[73] The document further states that the parents of those Pakistani nationals "know nothing regarding their child's military involvement with the Taliban until their bodies are brought back to Pakistan."[73] A further 3,000 fighter of the regular Taliban army were Arab and Central Asian militants.[85] From 1996 to 2001 the Al Qaeda of Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri became a state within the Taliban state.[88] Bin Laden sent Arab recruits to join the fight against the United Front.[88][89] Of roughly 45,000 Pakistani, Taliban and Al Qaeda soldiers fighting against the forces of Massoud only 14,000 were Afghan.[74][85]

According to Human Rights Watch in 1997 Taliban soldiers were summarily executed in and around Mazar-i Sharif by Dostum's Junbish forces.[90] Dostum was defeated by the Taliban in 1998 with the fall of Mazar-i-Sharif. Massoud remained the only leader of the United Front in Afghanistan.

In the areas under his control Ahmad Shah Massoud set up democratic institutions and signed the Women's Rights Charter.[74] Human Rights Watch cites no human rights crimes for the forces under direct control of Massoud for the period from October 1996 until the assassination of Massoud in September 2001.[90] As a consequence many civilians fled to the area of Ahmad Shah Massoud.[86][91] National Geographic concluded in its documentary "Inside the Taliban":

The only thing standing in the way of future Taliban massacres is Ahmad Shah Massoud."[86]

The Taliban repeatedly offered Massoud a position of power to make him stop his resistance. Massoud declined for he did not fight to obtain a position of power. He explained in one interview:

- "The Taliban say: "Come and accept the post of prime minister and be with us", and they would keep the highest office in the country, the presidentship. But for what price?! The difference between us concerns mainly our way of thinking about the very principles of the society and the state. We can not accept their conditions of compromise, or else we would have to give up the principles of modern democracy. We are fundamentally against the system called "the Emirate of Afghanistan"."[92]

- "There should be an Afghanistan where every Afghan finds himself or herself happy. And I think that can only be assured by democracy based on consensus."[93]

Massoud wanted to convince the Taliban to join a political process leading towards democratic elections in a foreseeable future.[92] His proposals for peace can be seen here: Proposal for Peace, promoted by Commander Massoud. Massoud also stated:

- "The Taliban are not a force to be considered invincible. They are distanced from the people now. They are weaker than in the past. There is only the assistance given by Pakistan, Osama bin Laden and other extremist groups that keep the Taliban on their feet. With a halt to that assistance, it is extremely difficult to survive."[93] In early 2001 Massoud employed a new strategy of local military pressure and global political appeals.[94] Resentment was increasingly gathering against Taliban rule from the bottom of Afghan society including the Pashtun areas.[94] Massoud publicized their cause "popular consensus, general elections and democracy" worldwide. At the same time he was very wary not to revive the failed Kabul government of the early 1990s.[94] Already in 1999 he started the training of police forces which he trained specifically in order to keep order and protect the civilian population in case the United Front would be successful.[74]

In early 2001 Massoud addressed the European Parliament in Brussels asking the international community to provide humanitarian help to the people of Afghanistan.[95] He stated that the Taliban and Al Qaeda had introduced "a very wrong perception of Islam" and that without the support of Pakistan the Taliban would not be able to sustain their military campaign for up to a year.[95] On this visit to Europe he also warned that his intelligence had gathered information about a large-scale attack on U.S. soil being imminent.[96]

Recent history (2001 - present)

On September 9, 2001, two Arab suicide attackers, allegedly belonging to Al Qaeda, posing as journalists, detonated a bomb hidden in a video camera while interviewing Ahmed Shah Massoud in the Takhar province of Afghanistan. Commander Massoud died in a helicopter that was taking him to a hospital. He was buried in his home village of Bazarak in the Panjshir Valley.[97] The funeral, although taking place in a rather rural area, was attended by hundreds of thousands of mourning people. (see video) Afghan journalist Fahim Dashty summarized:

- "He was the only one, ever, to serve Afghanistan, to serve Afghans. To do a lot of things for Afghanistan, for Afghans. And we lost him ..." (see video)

American author and journalist Sebastian Junger reported:

- "A lot of people who knew him felt that he was the best hope for that part of the world."[89]

The assassination on September 9, 2001, was not the first time Al Qaeda, the Taliban, the Pakistani ISI and before them the Soviet KGB, the Afghan communist KHCE and Hekmatyar had tried to assassinate Massoud. He had survived countless assassination attempts over a period of 26 years. The first attempt on Massoud's life was carried out by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and two Pakistani ISI agents in 1975 when Massoud was only 22 years old.[70] In early 2001 other Al Qaeda would-be assassins had been captured by Massoud's forces while trying to enter his territory.[94] For many days the United Front initially denied the death of Massoud for fear of desperation among their people. Mohammed Qasim Fahim, the next most senior military commander, succeeded Massoud a few days later.

Some analysts believe that Massoud's assassination is connected to the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, which may be the be the terrorist attack that Massoud had warned against during his speech to the European Parliament several months earlier. John P. O'Neill was a counter-terrorism expert and the Assistant Director of the FBI until late 2001. He retired from the FBI and was offered the position of director of security at the World Trade Center (WTC). He took the job at the WTC two weeks before 9/11. On September 10, 2001, John O'Neill told two of his friends,

- "We're due. And we're due for something big. ... Some things have happened in Afghanistan [referring to the assassination of Massoud]. I don't like the way things are lining up in Afghanistan. ... I sense a shift, and I think things are going to happen. ... soon."[98]

John O'Neill has died on September 11, 2001, when the south tower collapsed.[98] Following the September 11, 2001 attacks, the Federal government of the United States identified Osama bin Laden alongside Khalid Sheikh Mohammed as the faces behind the attacks. When the Taliban refused to hand over bin laden to U.S. authorities and refused to disband Al Qaeda bases in Afghanistan, the U.S. and British air forces began bombing al-Qaeda and Taliban targets inside Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom.[99] On the ground, American and British special forces along with CIA Special Activities Division units worked with commanders of the United Front (Northern Alliance) to launch a military offensive against the Taliban forces.[100] These attacks led to the fall of Mazar-i-Sharif and Kabul in November 2001, as the Taliban and al-Qaida retreated toward the mountainous Durand Line border with Pakistan. In December 2001, after the Taliban government was toppled and the new Karzai administration was formed, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was established by the UN Security Council to help assist Afghanistan in providing basic security.[101][102]

From 2002 onward, the Taliban began regrouping while more coalition troops entered the escalating US-led war with insurgents. Meanwhile, NATO assumed control of ISAF in 2003[103] and the rebuilding of Afghanistan began, which is funded by the international community especially by USAID and other U.S. agencies.[104][105] The European Union, Canada and India also play a major role in reconstruction.[106][107] The Afghan nation was able to build democratic structures and to make some progress in key areas such as health, economy, educational, transport, agriculture and construction sector. It has also modernized in the field of technology and banking. NATO, mainly the United States armed forces is rebuilding and modernizing the military of Afghanistan as well the Afghan National Police. Between 2002 and 2010, over five million Afghan expatriates returned with new skills and capital. Still, Afghanistan remains one of the poorest countries due to the results of 30 years of war, corruption among high level politicians and the ongoing Taliban insurgency from Pakistan.[108][109] U.S. officials have also accused Iran of providing limited support to the Taliban, but stated it was "at a small level" since it is "not in their interests to see the Taliban, a Sunni ultra-conservative, extremist element, return to take control of Afghanistan".[110][111][112] Iran has historically been an enemy of the Taliban.[113][114]

NATO and Afghan troops in recent years led many offensives against the Taliban, but proved unable to completely dislodge their presence. By 2009, a Taliban-led shadow government began to form complete with their own version of mediation court.[115] In 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama deployed an additional 30,000 soldiers over a period of six months and proposed that he will begin troop withdrawals by 2012. At the 2010 International Conference on Afghanistan in London, Afghan President Hamid Karzai said he intends to reach out to the Taliban leadership (including Mullah Omar, Sirajuddin Haqqani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar). Supported by senior U.S. officials Karzai called on the group's leadership to take part in a loya jirga meeting to initiate peace talks. According to the Wall Street Journal, these steps have been reciprocated so far with an intensification of bombings, assassinations and ambushes.[116] Many Afghan groups (including the former intelligence chief Amrullah Saleh and opposition leader Dr. Abdullah Abdullah) believe that Karzai's plan aims to appease the insurgents' senior leadership at the cost of the democratic constitution, the democratic process and progess in the field of human rights especially women's rights.[117]

"I should say that Taliban are not fighting in order to be accommodated. They are fighting in order to bring the state down. So it's a futile exercise, and it's just misleading. ... There are groups that will fight to the death. Whether we like to talk to them or we don't like to talk to them, they will continue to fight. So, for them, I don't think that we have a way forward with talks or negotiations or contacts or anything as such. Then we have to be prepared to tackle and deal with them militarily. In terms of the Taliban on the ground, there are lots of possibilities and opportunities that with the help of the people in different parts of the country, we can attract them to the peace process; provided, we create a favorable environment on this side of the line. At the moment, the people are leaving support for the government because of corruption. So that expectation is also not realistic at this stage."[118]

— Dr. Abdullah, 2010

According to a report by the United Nations the Taliban were responsible for 76 % of civilian casualties in 2009.[119] Afghanistan is currently struggling to rebuild itself while dealing with the above mentioned problems and challenges.

References

- ^ a b c d e "The Afghans - Their History and Culture". United States: Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL). June 30, 2002. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ "Country Profile: Afghanistan" (PDF). United States: Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. August 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ a b "The Pre-Islamic Period". United States: Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. 1997. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ a b c Dupree, Nancy Hatch (1977). An Historical Guide To Afghanistan (Chapter 3: Sites in Perspective) (2 ed.). United States: Afghan Air Authority, Afghan Tourist Organization. p. 492. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Dupree" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Shroder, John Ford (2006). "Afghanistan Archived". Regents Professor of Ge\Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ^ "Alexander and Macedonian Rule, 330-ca. 150 B.C." United States: Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. 1997. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ "Kingdoms of South Asia – Afghanistan (Southern Khorasan / Arachosia)". The History Files. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ "The Afghans - Language and Literacy". United States: Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL). June 30, 2002. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ "Last Afghan empire". Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree, and others. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Version. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ "Last Afghan Empire". Afghanpedia. Sabawoon.com. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ D. Balland. "AFGHANISTAN x. Political History". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ a b Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 64. ISBN 0823938638. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Baxter, Craig (1995) "Historical Setting" pp. 90–120, page 91, In Gladstone, Cary (2001) Afghanistan revisited Nova Science Publications, New York, ISBN 1-59033-421-3

- ^ Gandara...Link

- ^ W. Vogelsang, "Gandahar", in The Circle Of Ancient Iranian Studies

- ^ E. Herzfeld, "The Persian Empire: Studies on Geography and Ethnography of the Ancient Near East", ed. G. Walser, Wiesbaden 1968, pp. 279, 293–94, 336–38, 345

- ^ a b Mallory, J. P. (1997). "BMAC". Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

- ^ Francfort, H.-P. (2005) "La civilisation de l'Oxus et les Indo-iraniens et les Indo-aryens en Asie centrale" In Fussman, G. (2005). Aryas, Aryens et Iraniens en Asie Centrale. Paris: de Boccard. pp. 276–285. ISBN 2-86803-072-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Parpola, Asko (1998), "Aryan Languages, Archaeological Cultures, and Sinkiang: Where Did Proto-Iranian Come into Being and How Did It Spread?", in Mair (ed.), The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern and Central Asia, Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0-941694-63-1

- ^ M. Dandamayev and I. Medvedskaya (2006-08-15). "MEDIA". Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ Dupree, Louis: Afghanistan (1973), pg. 274.

- ^ "Achaemenid Rule, ca. 550-331 B.C." United States: Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. 1997. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ Dupree, Louis: Afghanistan (1973), pp. 276-283

- ^ Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul - The Name". American International School of Kabul. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Historiarum Philippicarum libri XLIV, XV.4.19

- ^ Puri, Baij Nath (1987). Buddhism in central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 352. ISBN 8120803728. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Dupree, Louis: Afghanistan (1973), pg. 302-303

- ^ "Khorasan". Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

Khorāsān, also spelled Khurasan, historical region and realm comprising a vast territory now lying in northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, and northern Afghanistan. The historical region extended, along the north, from the Amu Darya (Oxus River) westward to the Caspian Sea and, along the south, from the fringes of the central Iranian deserts eastward to the mountains of central Afghanistan.

- ^ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad Babur (1525). "Events Of The Year 910 (p.4)". Memoirs of Babur. Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354 (reprint, illustrated ed.). Routledge. 2004. p. 416. ISBN 0415344735. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

{{cite book}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (1560-16-20). "The History of India, Volume 6, chpt. 200, Translation of the Introduction to Firishta's History (p.8)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Afghan and Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ^ Noelle-Karimi, Christine (2002). Afghanistan -a country without a state?. University of Michigan, United States: IKO. p. 18. ISBN 3889396283. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

The earliest mention of the name 'Afghan' (Abgan) is to be found in a Sasanid inscription from the third century AD, and it appears in India in the form of 'Avagana'...

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "History of Afghanistan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Version. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ "Afghan". Ch. M. Kieffer. Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition. December 15, 1983. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ "The People - The Pashtuns". Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL). June 30, 2002. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- ^ "Pashtun: also spelled Pushtun, or Pakhtun, Hindustani Pathan, Persian Afghan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Version. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- ^ "Claims About Origin". Syed Zubir Rehman. pakhtun.com. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ^ Dawn News, The cradle of Pathan culture

- ^ "Islamic conquest". Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. 1997. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- ^ V. Minorsky. "The Turkish dialect of the Khalaj" (2 ed.). University of London. pp. 417–437. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 382. ISBN 0631198415. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Otfinoski, Steven Bruce (2004). Afghanistan. Infobase Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 0816050562. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Malleson, George Bruce (1878). History of Afghanistan, from the Earliest Period to the Outbreak of the War of 1878. London: Elibron.com. p. 459. ISBN 1402172788. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Malleson, George Bruce (1878). History of Afghanistan, from the Earliest Period to the Outbreak of the War of 1878. London: Elibron.com. p. 459. ISBN 1402172788. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "An Outline Of The History Of Persia During The Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 29. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Malleson, George Bruce (1878). History of Afghanistan, from the Earliest Period to the Outbreak of the War of 1878. London: Elibron.com. p. 459. ISBN 1402172788. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "An Outline Of The History Of Persia During The Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 30. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ "An Outline Of The History Of Persia During The Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 31. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ "Until His Assassination In A.D. 1747". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ "Afghanistan". Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). United States: The World Factbook. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

{{cite web}}: Text "acces.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/af.html" ignored (help) - ^ Friedrich Engels (1857). "Afghanistan". Andy Blunden. The New American Cyclopaedia, Vol. I. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ^ "Education in Afghanistan", published in Encyclopaedia Iranica, volume VIII – pp. 237–241

- ^ Barry Bearak, Former King of Afghanistan Dies at 92, The New York Times, July 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Amin Saikal. Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (2006 1st ed.). I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., London New York. p. 352. ISBN 1-85043-437-9. Cite error: The named reference "Amin Saikal" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The Soviet-Afghan War:Breaking the Hammer & Sickle[dead link]

- ^ a b "History of Afghanistan". Historyofnations.net. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "How the CIA created Osama bin Laden". greenleft. 2001.

- ^ "Putting Empires at Rest". Al-Ahram Democracy. 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Story of US, CIA and Taliban". The Brunei Times. 2009.

- ^ "The Cost of an Afghan 'Victory'". The Nation. 1999.

- ^ "Charlie Rose, March 2001, citing Wall Street Journal around 40:00 ff". Charlie Rose. 2001.

- ^ "Afghanistan (1979-2001)". Users.erols.com. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "Refugee Admissions Program for Near East and South Asia". Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

- ^ Afghanistan: History, Columbia Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c d e "Blood-Stained Hands, Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ Neamatollah Nojumi. The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region (2002 1st ed.). Palgrave, New York.

- ^ "The September 11 Sourcebooks Volume VII: The Taliban File". gwu.edu. 2003.

- ^ a b GUTMAN, Roy (2008): How We Missed the Story: Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban and the Hijacking of Afghanistan, Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace, 1st ed., Washington D.C.

- ^ "Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978-2001" (PDF). Afghanistan Justice Project. 2005.

- ^ a b c Matinuddin, Kamal, The Taliban Phenomenon, Afghanistan 1994–1997, Oxford University Press, (1999), pp.25–6

- ^ a b c d "Documents Detail Years of Pakistani Support for Taliban, Extremists". George Washington University. 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marcela Grad. Massoud: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Afghan Leader (March 1, 2009 ed.). Webster University Press. p. 310. Cite error: The named reference "Webster University Press Book" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Amnesty International. "DOCUMENT - AFGHANISTAN: FURTHER INFORMATION ON FEAR FOR SAFETY AND NEW CONCERN: DELIBERATE AND ARBITRARY KILLINGS: CIVILIANS IN KABUL." 16 November 1995 Accessed at: http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/ASA11/015/1995/en/6d874caa-eb2a-11dd-92ac-295bdf97101f/asa110151995en.html

- ^ Coll, Ghost Wars (New York: Penguin, 2005), 14.

- ^ a b "The Taliban's War on Women. A Health and Human Rights Crisis in Afghanistan" (PDF). Physicians for Human Rights. 1998.

- ^ "Afghan rebels seize capital, hang former president". CNN News. 1996-07-27.

- ^ a b c d e f Newsday (2001). "Taliban massacres outlined for UN". Chicago Tribune.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Newsday (2001). "Confidential UN report details mass killings of civilian villagers". newsday.org. Retrieved October 12, 2001.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ UNHCR (1999). "Afghanistan: Situation in, or around, Aqcha (Jawzjan province) including predominant tribal/ethnic group and who is currently in control". UNHCR.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Human Rights Watch (1998). "INCITEMENT OF VIOLENCE AGAINST HAZARAS BY GOVERNOR NIAZI". AFGHANISTAN: THE MASSACRE IN MAZAR-I SHARIF. hrw.org. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Iranian military exercises draw warning from Afghanistan". CNN News. 1997-08-31.

- ^ "Taliban threatens retaliation if Iran strikes". CNN News. 1997-09-15.

- ^ a b c d e "Afghanistan resistance leader feared dead in blast". Ahmed Rashid in the Telegraph. 2001. Cite error: The named reference "Ahmed Rashid/The Telegraph" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c "Inside the Taliban". National Geographic. 2007.

- ^ "History Commons". History Commons. 2010.

- ^ a b "BOOK REVIEW: The inside track on Afghan wars by Khaled Ahmed". Daily Times. 2008.

- ^ a b "Brigade 055". CNN. unknown.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Cite error: The named reference "CNN" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "Human Rights Watch Backgrounder, October 2001". Human Rights Watch. 2001.

- ^ "Inside the Taliban". National Geographic. 2007.

- ^ a b "The Last Interview with Ahmad Shah Massoud". Piotr Balcerowicz. 2001.

- ^ a b "The man who would have led Afghanistan". St. Petersburg Times. 2002.

- ^ a b c d Steve Coll. Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (February 23, 2004 ed.). Penguin Press HC. p. 720. Cite error: The named reference "Steve Coll: Ghost Wars" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Massoud in the European Parliament 2001". EU media. 2001.

- ^ Defense Intelligence Agency (2001) report http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB97/tal32.pdf

- ^ "Rebel Chief Who Fought The Taliban Is Buried"

- ^ a b "The Man Who Knew". PBS. 2002.

- ^ TYLER, PATRICK (October 8, 2001). "A NATION CHALLENGED: THE ATTACK; U.S. AND BRITAIN STRIKE AFGHANISTAN, AIMING AT BASES AND TERRORIST CAMPS; BUSH WARNS 'TALIBAN WILL PAY A PRICE'". New York Times. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ First In: An insiders account of how the CIA spearheaded the War on Terror in Afghanistan by Gary Schroen, 2005

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1386. S/RES/1386(2001) 31 May 2001. Retrieved 2007-09-21. - (UNSCR 1386)

- ^ "United States Mission to Afghanistan". Nato.usmission.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "NATO's role in Afghanistan". Nato.int. 2010-11-09. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ Julie Fossler. "USAID Afghanistan". Afghanistan.usaid.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "USAID Afghanistan's photostream". Flickr.com. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "India: Afghanistan's influential ally". BBC News. 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "Canada's Engagement in Afghanistan: Backgrounder". Afghanistan.gc.ca. 2010-07-09. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "Pakistan Accused of Helping Taliban". ABC News. 2008-07-31. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ "Wikileaks: Pakistan accused of helping Taliban in Afghanistan attacks". U.K. Telegraph. 26 Jul 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ "US General Accuses Iran Of Helping Taliban". Voice of America. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ "Iran Is Helping Taliban in Afghanistan, Petraeus Says (Update1)". Bloomberg L.P. February 14, 2009. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ Baldor, Lolita C. (June 13, 2007). "Gates: Taliban Getting Weapons From Iran". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ "Tensions mount between Iran, Afghanistan's Taliban". CNN. September, 1998. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Taliban threatens retaliation if Iran strikes". CNN. September, 1998. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Witte, Griff (2009-12-08). "Taliban shadow officials offer concrete alternative". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ^ "Karzai Divides Afghanistan in Reaching Out to Taliban". The "Wall Street Journal". 2010-09-11. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- ^ "Karzai's Taleban talks raise spectre of civil war warns former spy chief". The Scotsman. 2010-09-30.

- ^ "Abdullah Abdullah: Talks With Taliban Futile". National Public Radio (NPR). 2010-10-22.

- ^ "UN: Taliban Responsible for 76% of Deaths in Afghanistan". The Weekly Standard. 2010-08-10.

Further reading

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

External links

- A Country Study: Afghanistan - Library of Congress Country Studies

- Encyclopedia Britannica - History of Afghanistan

- Afghanistan (Southern Khorasan / Arachosia)

- Afghanistan's Importance From the Perspective of the History by Abdul Hai Habibi

- An Historical Guide to Kabul by Nancy Hatch Dupree

- Afghanistan Online – History of Afghanistan

- Afghanistan History: Prehistory

Chronological chart for the historical periods of Afghanistan | ||

−2200 — – −2000 — – −1800 — – −1600 — – −1400 — – −1200 — – −1000 — – −800 — – −600 — – −400 — – −200 — – 0 — – 200 — – 400 — – 600 — – 800 — – 1000 — – 1200 — – 1400 — – 1600 — – 1800 — – 2000 — – 2200 — | Coming of Iranians c.1700-1100 BC: The Rigveda, one of the oldest known texts written in an Indo-European language, is composed in a region described as Sapta Sindhu ('land of seven great rivers', which may correspond to the Kabul Valley). c. 1350 BC: Migration of waves of Iranian tribes begin from the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex westwards to the Iranian plateau, western Afghanistan and western Iran. According to the Avesta (Vendidad 1.1-21), they are compelled to leave their homeland Airyana Vaēǰah because Aŋra Mainyu so altered the climate that the winter became ten months long and the summer only two. Along the way, they settle down near large rivers, such as Bāxδī, Harōiva, Haraxᵛaitī, etc. (See Avestan geography.) c. 1100-550 BC: Zoroaster introduces a new religion at Bactra (present-day Balkh) - Zoroastrianism - which spreads across Iranian plateau. He composes Older (i.e. 'Gathic') Avesta and later Younger Avesta is composed - at least - in Sīstān/Arachosia, Herāt, Merv and Bactria. | |