Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

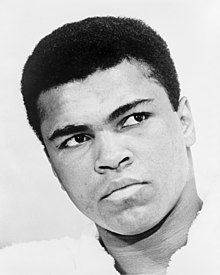

Ali in 1967 | |||||||||||||||

| Born | January 17, 1942 Louisville, Kentucky, USA | ||||||||||||||

| Nationality | |||||||||||||||

| Other names | The Greatest The People's Champion The Louisville Lip | ||||||||||||||

| Statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Weight(s) | Heavyweight | ||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) | ||||||||||||||

| Reach | 80 in (203 cm) | ||||||||||||||

| Stance | Orthodox | ||||||||||||||

| Boxing record | |||||||||||||||

| Total fights | 61 | ||||||||||||||

| Wins | 56 | ||||||||||||||

| Wins by KO | 37 | ||||||||||||||

| Losses | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Draws | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| No contests | 0 | ||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||

Muhammad Ali (born Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr.; January 17, 1942) is an American former professional boxer,[1] philanthropist[2] and social activist.[2] Considered a cultural icon, Ali was both idolised and vilified.[3][4]

Originally known as Cassius Clay, Ali changed his name, after joining the Nation of Islam in 1964, the same year his friend Malcolm X would leave, subsequently converting to traditional Islam; Ali would follow suit in the '70s. In 1967, three years after Ali had won the World Heavyweight Championship, he was publicly vilified for his refusal to be conscripted into the U.S. military, based on his religious beliefs and opposition to the Vietnam War – "I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong... No Vietcong ever called me nigger" – one of the more telling remarks of the era.[5]

Widespread protests against the Vietnam War had not yet begun, but with that one phrase, Ali articulated the reason to oppose the war for a generation of young Americans, and his words served as a touchstone for the racial and antiwar upheavals that would rock the 60's. Ali's example inspired Martin Luther King Jr. – who had been reluctant to alienate the Johnson Administration and its support of the civil rights agenda – to voice his own opposition to the war for the first time.[6]

Ali would then be arrested and found guilty on draft evasion charges, stripped of his boxing title, and his boxing license was suspended. He was not imprisoned, but did not fight again for nearly four years while his appeal worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was eventually successful.

Ali would go on-to become the first and only, three-time Lineal World Heavyweight Champion.

Nicknamed "The Greatest," Ali was involved in several historic boxing matches. Notable among these were three with rival Joe Frazier, which rank among the greatest in boxing history, and one with George Foreman, where he finally regained his stripped titles seven years later. Ali was well known for his unorthodox fighting style, which he described as "float like a butterfly, sting like a bee", and employing techniques such as the Ali Shuffle and the rope-a-dope.[7] Ali had brought beauty and grace to the most uncompromising of sports and through the wonderful excesses of skill and character, he had become the most famous athlete in the world.[8] He was also known for his pre-match hype, where he would "trash talk" opponents, often with rhymes.

In 1999, Ali was crowned "Sportsman of the Century" by Sports Illustrated and "Sports Personality of the Century" by the BBC.[9][10]

Biography

Amateur career and Olympic gold

Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr., was born on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky.[11] The younger of two boys, he was named after his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay, Sr., who was named for the 19th century abolitionist and politician of the same name. His father painted billboards and signs,[11] and his mother, Odessa O'Grady Clay, was a household domestic. Although Cassius Sr. was a Methodist, he allowed Odessa to bring up both Cassius and his elder brother Rudolph "Rudy" Clay (later renamed Rahman Ali) as Baptists.[12] He is a descendant of pre-Civil War era American slaves in the American South, and is predominantly of African-American descent, with some Irish and English ancestry.[13]

Clay was first directed toward boxing by the white Louisville police officer and boxing coach Joe E. Martin,[14] who encountered the 12-year-old fuming over the theft of his bicycle.[15] However, without Martin's knowledge, Clay began training with Fred Stoner, an African-American trainer working at the local community center.[16] In this way, Clay could make $4 a week on Tomorrow's Champions, a local, weekly TV show that Martin hosted, while benefiting from the coaching of the more experienced Stoner. For the last four years of Clay's amateur career he was trained by legendary boxing cutman Chuck Bodak.[17]

Clay won six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles, two national Golden Gloves titles, an Amateur Athletic Union National Title, and the Light Heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome.[18][19] Clay's amateur record was 100 wins with five losses.

Ali states (in his 1975 autobiography) that he threw his Olympic gold medal into the Ohio River after being refused service at a 'whites-only' restaurant, and fighting with a white gang.[20] Whether this is true is still debated, although he was given a replacement medal at a basketball intermission during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where he lit the torch to start the games.

Early professional career

After his Olympic triumph, Clay returned to Louisville to begin his professional career. There, on October 29, 1960, he won his first professional fight, a six-round decision over Tunney Hunsaker, who was the police chief of Fayetteville, West Virginia.

Standing tall, at 6-ft, 3-in (1.91 m), Clay had a highly unorthodox style for a heavyweight boxer. Rather than the normal style of carrying the hands high to defend the face, he instead relied on foot speed and quickness to avoid punches, and carried his hands low.

From 1960 to 1963, the young fighter amassed a record of 19–0, with 15 knockouts. He defeated boxers such as Tony Esperti, Jim Robinson, Donnie Fleeman, Alonzo Johnson, George Logan, Willi Besmanoff, Lamar Clark (who had won his previous 40 bouts by knockout), Doug Jones and Henry Cooper.

Clay built a reputation by correctly predicting the round in which he would "finish" several opponents, and by boasting before his triumphs.[11] Clay admitted he adopted the latter practice from "Gorgeous" George Wagner, a popular professional wrestling champion in the Los Angeles area who drew thousands of fans.[11] Often referred to as "the man you loved to hate," George could incite the crowd with a few heated remarks, and Ali followed suit.

Among Clay's victims were Sonny Banks (who knocked him down during the bout), Alejandro Lavorante, and the aged Archie Moore (a boxing legend who had fought over 200 previous fights, and who had been Clay's trainer prior to Angelo Dundee). Clay had considered continuing using Moore as a trainer following the bout, but Moore had insisted that the cocky "Louisville Lip" perform training camp chores such as sweeping and dishwashing. He considered having his idol, Sugar Ray Robinson, as a manager, but instead hired Dundee.

Clay first met Dundee when the latter was in Louisville with light heavyweight champ Willie Pastrano. The teenaged Golden Gloves winner traveled downtown to the fighter's hotel, called Dundee from the house phone, and was asked up to their room. He took advantage of the opportunity to query Dundee (who had worked with champions Sugar Ramos and Carmen Basilio) about what his fighters ate, how long they slept, how much roadwork (jogging) they did, and how long they sparred.

Following his bout with Moore, Clay won a disputed 10-round decision over Doug Jones in a matchup that was named "Fight of the Year" for 1963. Clay's next fight was against Henry Cooper, who knocked Clay down with a left hook near the end of the fourth round. The fight was stopped in the fifth due to deep cuts over Cooper's eyes.

Despite these close calls, Clay became the top contender for Sonny Liston's title. However, although he had an impressive record, he was not widely expected to defeat the champ. The fight was scheduled for February 25, 1964 in Miami, Florida, but was nearly canceled when the promoter, Bill Faversham, heard that Clay had been seen around Miami and in other cities with the controversial Malcolm X, a member of The Nation of Islam. Because of this, news of this association was perceived as a potential gate-killer to a bout which, given Liston's overwhelming status as the favorite to win (7–1 odds),[21] had Clay's colorful persona and nonstop braggadocio as its sole appeal.

Faversham confronted Clay about his association with Malcolm X (who, at the time, was actually under suspension by the Nation as a result of controversial comments made in the wake of President Kennedy's assassination). While stopping short of admitting he was a member of the Nation, Clay protested the suggested cancellation of the fight. As a compromise, Faversham asked the fighter to delay his announcement about his conversion to Islam until after the fight. The incident is described in the 1975 book The Greatest: My Own Story by Ali (with Richard Durham).

During the weigh-in on the day before the bout, the ever-boastful Clay, who frequently taunted Liston during the buildup by dubbing him "the big ugly bear" (among other things), declared that he would "float like a butterfly and sting like a bee," and, summarizing his strategy for avoiding Liston's assaults, said, "Your hands can't hit what your eyes can't see."

First title fight and aftermath

At the pre-fight weigh-in, Clay's pulse rate was around 120, more than double his norm of 54.[22] Liston, among others, misread this as nervousness. In the opening rounds, Clay's speed kept him away from Liston's powerful head and body shots, as he used his height advantage to beat Liston to the punch with his own lightning-quick jab.[22]

By the third round, Clay was ahead on points and had opened a cut under Liston's eye.[22] Liston regained some ground in the fourth, as Clay was blinded by a substance in his eyes.[22] It is unconfirmed whether this was something used to close Liston's cuts, or deliberately applied to Liston's gloves;[22] however, Bert Sugar has claimed that "in two of his previous fights, Liston's opponents had complained about their eyes 'burning,'"[23] suggesting the possibility that the Liston corner deliberately attempted to cheat.

Liston began the fourth round looking to put away the challenger. As Clay struggled to recover his vision, he sought to escape Liston's offensive. He was able to keep out of range until his sweat and tears rinsed the substance from his eyes, responding with a flurry of combinations near the end of the fifth round. By the sixth, he was looking for a finish and dominated Liston. Then, Liston shocked the boxing world when he failed to answer the bell for the seventh round, stating he had a shoulder injury. At the end of the fight, Clay boasted to the press that doubted him before the match, proclaiming, "I shook up the world!"

When Clay beat Liston, he was the youngest boxer (age 22) ever to take the title from a reigning heavyweight champion, a mark that stood until Mike Tyson won the title from Trevor Berbick on November 22, 1986. At the time, Floyd Patterson (dethroned by Liston) had been the youngest heavyweight champ ever (age 21), but he won the title during an elimination tournament following Rocky Marciano's retirement by defeating Archie Moore, the light-heavyweight champion at the time.

In the rematch with Liston, which was held in May 1965 in Lewiston, Maine, Ali (who had by then publicly converted to Islam and changed his name) won by knockout in the first round as a result of what came to be called the "phantom punch." Many believe that Liston, possibly as a result of threats from Nation of Islam extremists, or in an attempt to "throw" the fight to pay off debts, waited to be counted out (see Muhammad Ali versus Sonny Liston). Others, however, discount both scenarios and insist that it was a quick, chopping Ali punch to the side of the head that legitimately felled Liston.

Early title defenses

On November 22, 1965, Ali fought Floyd Patterson in his second title defense. Patterson lost by technical knockout at the end of the 12th round. As would later occur with Ernie Terrell, many sportswriters accused Ali of "carrying" Patterson so that he could physically punish him without knocking him out. Ali countered that Patterson, who said his punching prowess was limited when he strained his sacroiliac, was not as easy to down as may have appeared.

Ali was scheduled to fight WBA champion Ernie Terrell (the WBA stripped Ali of his title after his agreement to fight a rematch with Liston) on March 29, 1966, but Terrell backed out. Ali won a 15-round decision against substitute opponent George Chuvalo. He then went to England and defeated Henry Cooper by stoppage on cuts May 21, and knocked out Brian London in the third round in August. Ali's next defense was against German southpaw Karl Mildenberger, the first German to fight for the title since Max Schmeling. In one of the tougher fights of his life, Ali stopped his opponent in round 12.

Ali returned to the United States in November 1966 to fight Cleveland "Big Cat" Williams in the Houston Astrodome. According to the Sports Illustrated account, the bout drew an indoor world record 35,460 fight fans. A year and a half before the fight, Williams had been shot in the stomach at point-blank range by a Texas policeman. As a result, Williams went into the fight missing one kidney and 10 feet (3.0 m) of his small intestine, and with a shriveled left leg from nerve damage from the bullet. Ali beat Williams in three rounds.

On February 6, 1967, Ali returned to a Houston boxing ring to fight Terrell in what is regarded as one of the uglier fights in boxing. Terrell had angered Ali by calling him Clay, and the champion vowed to punish him for this insult. During the fight, Ali kept shouting at his opponent, "What's my name, Uncle Tom ... What's my name?" Terrell suffered 15 rounds of brutal punishment, losing 13 rounds on two judges' scorecards, but Ali did not knock him out. Analysts, including several who spoke to ESPN on the sports channel's "Ali Rap" special, speculated that the fight continued only because Ali wanted to thoroughly punish and humiliate Terrell. After the fight, Tex Maule wrote, "It was a wonderful demonstration of boxing skill and a barbarous display of cruelty." When asked about this during a replay of the fight on ABC's popular "Wide World of Sports" by host Howard Cosell, Ali said he was not unduly cruel to Terrell- that boxers are paid to punch all their opponents into submission or defeat. He pointed out that if he had not hit and hurt Terrell, Terrell would have hit and hurt him, which is standard practice. Cosell's repeated reference to the topic surprised Ali. Following his final defense against Zora Folley in March 1967 Ali would be stripped of his title the following month for refusing to be drafted into the Army[11] and had his professional boxing license suspended.

Conversion to the Nation of Islam

After winning the championship from Liston in 1964, Clay revealed that he was a member of the Nation of Islam (often called the Black Muslims at the time) and the Nation gave Clay the name Cassius X, discarding his surname as a symbol of his ancestors' enslavement, as had been done by other Nation members. On Friday, March 6, 1964, Malcolm X took Clay on a guided tour of the UN building (for a second time). Malcolm X announced that Clay would be granted his "X." That same night, Elijah Muhammad recorded a statement over the phone to be played over the radio that Clay would be renamed Muhammad (one who is worthy of praise) Ali (fourth rightly guided caliph). Only a few journalists (most notably Howard Cosell) accepted it at that time. Venerable boxing announcer Don Dunphy addressed the champion by his adopted name, as did British reporters. The adoption of this name symbolized his new identity as a member of the Nation of Islam.

Many sportswriters of the early 1960s reported[where?] that it was Ali's brother, Rudy Clay, who converted to Islam first (estimating the date as 1961). Others wrote[where?] that Clay had been seen at Muslim rallies a few years before he fought Liston. Ali's own version[where?] is that he would sneak into Nation of Islam meetings through the back door roughly three years before he fought Sonny Liston.

Aligning himself with the Nation of Islam made him a lightning rod for controversy, turning the outspoken but popular champion into one of that era's most recognizable and controversial figures. Appearing at rallies with Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad and declaring his allegiance to him at a time when mainstream America viewed them with suspicion—if not outright hostility—made Ali a target of outrage, as well as suspicion. Ali seemed at times to provoke such reactions, with viewpoints that wavered from support for civil rights to outright support of separatism. For example, Ali once stated, in relation to integration: "We who follow the teachings of Elijah Muhammad don't want to be forced to integrate. Integration is wrong. We don't want to live with the white man; that's all."[24] And in relation to inter-racial marriage: "No intelligent black man or black woman in his or her right black mind wants white boys and white girls coming to their homes to marry their black sons and daughters."[24] Indeed, Ali's religious beliefs at the time included the notion that the white man was "the devil" and that white people were not "righteous." Ali claimed that white people hated black people.

Ali converted from the Nation of Islam sect to mainstream Sunni Islam in 1975. In a 2004 autobiography, written with daughter Hana Yasmeen Ali, Muhammad Ali attributes his conversion to the shift toward Sunni Islam made by Warith Deen Muhammad after he gained control of the Nation of Islam upon the death of Elijah Muhammad in 1975. Later in 2005 he embraced spiritual practices of Sufism.[25]

Vietnam War

In 1964, Ali failed the U.S. Armed Forces qualifying test because his writing and spelling skills were sub-par. However, in early 1966, the tests were revised and Ali was reclassified as 1A.[11] This classification meant he was now eligible for the draft and induction into the U.S. Army during a time when the United States was involved in the Vietnam War. When notified of this status, he declared that he would refuse to serve in the United States Army and publicly considered himself a conscientious objector.[11] Ali stated that "War is against the teachings of the Holy Qur'an. I'm not trying to dodge the draft. We are not supposed to take part in no wars unless declared by Allah or The Messenger. We don't take part in Christian wars or wars of any unbelievers." Ali famously said in 1966: "I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong ... They never called me nigger." Rare for a heavyweight boxing champion in those days, Ali spoke at Howard University, where he gave his popular "Black Is Best" speech to 4,000 cheering students and community intellectuals after he was invited to speak at Howard by a Howard sociology professor, Nathan Hare, on behalf of the Black Power Committee, a student protest group.[26][27]

Appearing shortly thereafter for his scheduled induction into the U.S. Armed Forces on April 28, 1967 in Houston, he refused three times to step forward at the call of his name. An officer warned him he was committing a felony punishable by five years in prison and a fine of $10,000. Once more, Ali refused to budge when his name was called. As a result, he was arrested and on the same day the New York State Athletic Commission suspended his boxing license and stripped him of his title. Other boxing commissions followed suit.

At the trial on June 20, 1967, after only 21 minutes of deliberation, the jury found Ali guilty.[11] After a Court of Appeals upheld the conviction, the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. During this time, the public began turning against the war and support for Ali began to grow. Ali supported himself by speaking at colleges and universities across the country, where opposition to the war was especially strong. On June 28, 1971, the Supreme Court reversed his conviction for refusing induction by unanimous decision in Clay v. United States.[11] The decision was not based on, nor did it address, the merits of Clay's/Ali's claims per se; rather, the Government's failure to specify which claims were rejected and which were sustained, constituted the grounds upon which the Court reversed the conviction.[28]

Quotes about Vietnam war

I ain't got no quarrel with the Vietcong. No Vietcong ever called me Nigger.[29]

No, I am not going 10,000 miles to help murder kill and burn other people to simply help continue the domination of white slavemasters over dark people the world over. This is the day and age when such evil injustice must come to an end.[30]

Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?[29]

The Fight of the Century

In 1970, while his case was still on appeal, Ali was allowed to fight again. On August 12, 1970, with the help of Leroy R. Johnson, a Georgia State Senator, he was granted a license to box by the City of Atlanta Athletic Commission.[31] In Atlanta on October 26, 1970, he stopped Jerry Quarry on a cut after three rounds. Shortly after the Quarry fight, the New York State Supreme Court ruled that Ali had been unjustly denied a boxing license. Once again able to fight in New York, he fought Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden in December 1970. After a tough 14 rounds, Ali stopped Bonavena in the 15th, paving the way for a title fight against Joe Frazier, who was himself undefeated.

Ali and Frazier met in the ring on March 8, 1971, at Madison Square Garden. The fight, known as "The Fight of the Century," was one of the most eagerly anticipated bouts of all time and remains one of the most famous. It featured two skilled, undefeated fighters, both of whom had legitimate claims to the heavyweight crown. Frank Sinatra—unable to acquire a ringside seat—took photos of the match for Life magazine. Legendary boxing announcer Don Dunphy and actor and boxing aficionado Burt Lancaster called the action for the broadcast, which reached millions of people. The fight lived up to the hype, and Frazier punctuated his victory by flooring Ali with a hard, leaping left hook in the 15th and final round. Frazier retained the title on a unanimous decision, dealing Ali his first professional loss.

In 1972 Muhammad Ali held the "Muhammad Ali Boxing Show," a series of exhibition matches between himself and other wrestlers. In San Antonio, Texas, during the exhibition series, on October 24, 1972, Ali lost against boxer Elmo Henderson.[32]

In 1973, Ali fought Ken Norton, who had broken Ali's jaw and won by split decision over 12 rounds in their first bout in 1972. Ali won the rematch, by split decision, on September 10, 1973, which set up Ali-Frazier II, a nontitle rematch with Joe Frazier, who had already lost his title to George Foreman. The bout was held on January 28, 1974, with Ali winning a unanimous 12-round decision.

The Rumble in the Jungle

In one of the biggest upsets in boxing history, Ali regained his title on October 30, 1974 by defeating champion George Foreman in their bout in Kinshasa, Zaire. Hyped as "The Rumble in the Jungle", the fight was promoted by Don King.

Almost no one, not even Ali's long-time supporter Howard Cosell, gave the former champion a chance of winning. Analysts pointed out that Joe Frazier and Ken Norton had given Ali four tough battles in the ring and won two of them, while Foreman had knocked out both of them in the second round. As a matter of fact, so total was the domination that, in their bout, Foreman had knocked down Frazier an incredible six times in only four minutes and 25 seconds.

During the bout, Ali employed an unexpected strategy. Leading up to the fight, he had declared he was going to "dance" and use his speed to keep away from Foreman and outbox him. However, in the first round, Ali headed straight for the champion and began scoring with a right hand lead, clearly surprising Foreman. Ali caught Foreman nine times in the first round with this technique but failed to knock him out. He then decided to take advantage of the young champion's weakness: staying power. Foreman had won 37 of his 40 bouts by knockout, mostly within three rounds. Eight of his previous bouts did not go past the second round. Ali saw an opportunity to outlast Foreman, and capitalized on it.

In the second round, the challenger retreated to the ropes—inviting Foreman to hit him, while counterpunching and verbally taunting the younger man. Ali's plan was to enrage Foreman and absorb his best blows to exhaust him mentally and physically. While Foreman threw wide shots to Ali's body, Ali countered with stinging straight punches to Foreman's head. Foreman threw hundreds of punches in seven rounds, but with decreasing technique and potency. Ali's tactic of leaning on the ropes, covering up, and absorbing ineffective body shots was later termed "The Rope-A-Dope".

By the end of the seventh round, Foreman was exhausted. In the eighth round, Ali dropped Foreman with a combination at center ring and Foreman failed to make the count. Against the odds, Ali had regained the title.

The "Rumble in the Jungle" was the subject of a 1996 Academy Award winning documentary film, When We Were Kings. The fight and the events leading up to it are extensively depicted in both John Herzfeld's 1997 docudrama Don King: Only in America and Michael Mann's 2001 docudrama, Ali.

The Thrilla in Manila

In March 1975, Ali faced Chuck Wepner in a bout that inspired the original Rocky. While it was largely thought that Ali would dominate, Wepner surprised everyone by not only knocking Ali down in the ninth round, but nearly going the distance. Ali eventually stopped Wepner in the fading minutes of the 15th round. Following a title defense with Ron Lyle, in July Ali faced Joe Bugner, winning a 15 round decision.

On October 1, 1975, Ali fought Joe Frazier for the third time.[11] Taking place in the Philippines, the bout was promoted as the Thrilla in Manila[11] by Don King, who had ascended to prominence following the Ali-Foreman fight. The anticipation was enormous for this final clash between two great heavyweights. Ali believed Frazier was "over the hill" by that point. Ali's frequent insults, slurs and demeaning poems increased the anticipation and excitement for the fight, but enraged a determined Frazier. Regarding the fight, Ali famously remarked, "It will be a killa... and a chilla... and a thrilla... when I get the gorilla in Manila."

The fight lasted 14 grueling rounds in temperatures approaching 100 °F (38 °C). Ali won many of the early rounds, but Frazier staged a comeback in the middle rounds, while Ali lay on the ropes. By the late rounds, however, Ali had reasserted control and the fight was stopped when Frazier was unable to answer the bell for the 15th and final round (his eyes were swollen closed). Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, refused to allow Frazier to continue.

Subsequent bouts and retirement

In February 1976, Ali easily beat Jean-Pierre Coopman. In April 1976 he defeated Jimmy Young and then Richard Dunn the following month, which would turn out to be Ali's last knockout victory. Following that fight, he staged an exhibition match with professional wrestler and martial artist Antonio Inoki.[33] Although widely perceived as a publicity stunt, the match against Inoki would have a long-term detrimental affect on Ali's mobility. Inoki spent much of the fight on the ground trying to damage Ali’s legs, while Ali spent most of the fight dodging the kicks or staying on the ropes.[34] At the end of 15 rounds, the bout was called a draw. Ali's legs, however, were bleeding, leading to an infection. He suffered two blood clots in his legs as well.[33]

In September 1976, at Yankee Stadium, Ali faced Ken Norton in their third fight, with Ali winning a close but unanimous 15-round decision. 1977 saw Ali defend his title against Alfredo Evangelista and Earnie Shavers. Fight doctor Ferdie Pacheco left Ali's camp following the Shavers fight after being rebuffed for advising Ali to retire.

In February 1978, Ali lost the heavweight title to 1976 Olympics Champion Leon Spinks. On September 15, 1978, Ali fought a rematch in the New Orleans Louisiana Superdome against Spinks for the WBA version of the Heavyweight title, winning it for a record third time. Ali retired following this victory on June 27, 1979, but returned in 1980 to face current champion Larry Holmes in an attempt to win a heavyweight title an unprecedented four times. Angelo Dundee refused to let his man come out for the 11th round, in what became Ali's only loss by anything other than a decision. Ali's final fight, a loss by unanimous decision after 10 rounds, was to up-and-coming challenger Trevor Berbick in 1981.

Ali's legacy

Muhammad Ali defeated every top heavyweight in his era, which has been called the golden age of heavyweight boxing. Ali was named "Fighter of the Year" by Ring Magazine more times than any other fighter, and was involved in more Ring Magazine "Fight of the Year" bouts than any other fighter. He is an inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and holds wins over seven other Hall of Fame inductees. He is one of only three boxers to be named "Sportsman of the Year" by Sports Illustrated.

In 1978, three years before Ali's permanent retirement, the Board of Aldermen in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky voted 6–5 to rename Walnut Street to Muhammad Ali Boulevard. This was controversial at the time, as within a week 12 of the 70 street signs were stolen. Earlier that year, a committee of the Jefferson County Public Schools considered renaming Central High School in his honor, but the motion failed to pass. At any rate, in time, Muhammad Ali Boulevard—and Ali himself—came to be well accepted in his hometown.[35]

In 1993, the Associated Press reported that Ali was tied with Babe Ruth as the most recognized athlete, out of over 800 dead or alive athletes, in America. The study found that over 97% of Americans, over 12-years of age, identified both Ali and Ruth.[36]

He was the recipient of the 1997 Arthur Ashe Courage Award.

In retirement

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome in 1984,[37][38] a disease to which those subject to severe head trauma, such as boxers, are many times more susceptible than average.[39] Despite the disability, he remains a beloved and active public figure. In 1985, he served as a guest referee at the inaugural WrestleMania event.[40][41] In 1987 he was selected by the California Bicentennial Foundation for the U.S. Constitution to personify the vitality of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights in various high profile activities. Ali rode on a float at the 1988 Tournament of Roses Parade, launching the U.S. Constitution's 200th birthday commemoration. He published an oral history, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times by Thomas Hauser, in 1991. That same year Ali traveled to Iraq during the Gulf War and met with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages.[42] Ali received a Spirit of America Award calling him the most recognized American in the world. In 1996, he had the honor of lighting the flame at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia.

He appeared at the 1998 AFL (Australian Football League) Grand Final, where Anthony Pratt invited him to watch the game. He greets runners at the start line of the Los Angeles Marathon every year.

In 1999, the BBC produced a special version of its annual BBC Sports Personality of the Year Award ceremony, and Ali was voted their Sports Personality of the Century,[43] receiving more votes than the other four contenders combined. His daughter Laila Ali became a boxer in 1999,[44] despite her father's earlier comments against female boxing in 1978: "Women are not made to be hit in the breast, and face like that... the body's not made to be punched right here [patting his chest]. Get hit in the breast... hard... and all that."[45]

On September 13, 1999, Ali was named "Kentucky Athlete of the Century" by the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame in ceremonies at the Galt House East.[46]

In 2001, a biographical film, entitled Ali, was made, directed by Michael Mann, with Will Smith starring as Ali. The film received mixed reviews, with the positives generally attributed to the acting, as Smith and supporting actor Jon Voight earned Academy Award nominations. Prior to making the Ali movie, Will Smith had continually rejected the role of Ali until Muhammad Ali personally requested that he accept the role. According to Smith, the first thing Ali said about the subject to him was: "Man, you're almost pretty enough to play me."[47]

On November 17, 2002, Muhammad Ali went to Afghanistan as "U.N. Messenger of Peace".[48] He was in Kabul for a three-day goodwill mission as a special guest of the UN.[49]

On January 8, 2005, Muhammad Ali was presented with the Presidential Citizens Medal by President George W. Bush.

He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom at a White House ceremony on November 9, 2005,[50][51] and the "Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold" of the UN Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin for his work with the US civil rights movement and the United Nations (December 17, 2005).

On November 19, 2005 (Ali's 19th wedding anniversary), the $60 million non-profit Muhammad Ali Center opened in downtown Louisville. In addition to displaying his boxing memorabilia, the center focuses on core themes of peace, social responsibility, respect, and personal growth.

According to the Ali Center website, "Since he retired from boxing, Ali has devoted himself to humanitarian endeavors around the globe. He is a devout Muslim, and travels the world over, lending his name and presence to hunger and poverty relief, supporting education efforts of all kinds, promoting adoption and encouraging people to respect and better understand one another. It is estimated that he has helped to provide more than 22 million meals to feed the hungry. Ali travels, on average, more than 200 days per year."

At the FedEx Orange Bowl on January 2, 2007, Ali was an honorary captain for the Louisville Cardinals wearing their white jersey, number 19. Ali was accompanied by golf legend Arnold Palmer, who was the honorary captain for the Wake Forest Demon Deacons, and Miami Heat star Dwyane Wade.

A youth club in Ali's hometown and a species of rose (Rosa ali) have been named after him. On June 5, 2007, he received an honorary doctorate of humanities at Princeton University's 260th graduation ceremony.[52]

Ali lives in Scottsdale, Arizona with his fourth wife, Yolanda "Lonnie" Ali.[53] They own a house in Berrien Springs, Michigan, which is for sale. On January 9, 2007, they purchased a house in eastern Jefferson County, Kentucky for $1,875,000.[54] Lonnie converted to Islam from Catholicism in her late 20s.[55]

On August 17, 2009, it was voted unanimously by the town council of Ennis, Co Clare, Ireland to make Ali the first Freeman of Ennis. Ennis was the birthplace of Ali's great grandfather before he emigrated to the U.S. in the 1860s, before eventually settling in Kentucky.[56] On September 1, 2009, Ali visited the town of Ennis and at a civic reception he received the honour of the freedom of the town.[57]

Ranking in heavyweight history

Ali is generally considered to be one of the greatest heavyweights of all time by boxing commentators and historians. Ring Magazine, a prominent boxing magazine, named him number 1 in a 1998 ranking of greatest heavyweights from all eras.[58]

Ali was named the second greatest fighter in boxing history by ESPN.com behind only welterweight and middleweight great Sugar Ray Robinson.[59] In December 2007, ESPN listed Ali second in its choice of the greatest heavyweights of all time, behind Joe Louis.[60]

Personal life

Muhammad Ali has been married four times and has seven daughters and two sons. Ali met his first wife, cocktail waitress Sonji Roi, approximately one month before they married on August 14, 1964.[citation needed] Roi's objections to certain Muslim customs in regard to dress for women contributed to the breakup of their marriage. They divorced on January 10, 1966.

On August 17, 1967, Ali married Belinda Boyd. After the wedding, she, like Ali, converted to Islam and more recently to Sufism,[61] changed her name to Khalilah Ali, though she was still called Belinda by old friends and family. They had four children: Maryum (b. 1968), Jamillah and Rasheda (b. 1970), and Muhammad Ali Jr. (b. 1972).[62]

In 1975, Ali began an affair with Veronica Porsche, an actress and model. By the summer of 1977, Ali's second marriage was over and he had married Veronica.[63] At the time of their marriage, they had a baby girl, Hana, and Veronica was pregnant with their second child. Their second daughter, Laila, was born in December 1977. By 1986, Ali and Veronica were divorced.

On November 19, 1986, Ali married Yolanda Ali. They had been friends since 1964 in Louisville. They have one son, Asaad Amin, who they adopted when Amin was five.[62][64][65][66][67]

Ali has two other daughters, Miya and Khaliah, from extramarital relationships.[62][68]

In later life, Ali developed Parkinson's syndrome.

Ali in the media and popular culture

As a world champion boxer and social activist, Ali has been the subject of numerous books, films and other creative works. In 1963, he released an album of spoken word on Columbia Records titled I am the Greatest! He has appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated on 37 different occasions, second only to Michael Jordan.[69] He appeared in the documentary film Black Rodeo (1972) riding both a horse and a bull. His autobiography The Greatest: My Own Story, written with Richard Durham, was published in 1975.[70] In 1977 the book was adapted into a film called The Greatest, in which Ali played himself and Ernest Borgnine played Angelo Dundee. When We Were Kings, a 1996 documentary about the Rumble in the Jungle, won an Academy Award,[71] and the 2001 biopic Ali garnered an Oscar nomination for Will Smith's portrayal of the lead role.[72]

For contributions to the entertainment industry, Muhammed Ali was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard.[73]

Professional boxing record

See also

- List of heavyweight boxing champions

- List of North American Muslims

- List of people from Louisville, Kentucky

- List of WBA world champions

- List of WBC world champions

- Notable boxing families

- Conscientious Objector

Notes

- ^ a b "Muhammad Ali - Boxer". Boxrec.com. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ a b "Muhammad Ali Biography". Biography.com. January 17, 1942. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Muhammad Ali - Biography of Muhammad Ali - Page 2". History1900s.about.com. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ Cagle, Jess (December 17, 2001). "Ali: Lord of the Ring". TIME. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ Plimpton, George (June 14, 1999). "MUHAMMAD ALI: The Greatest". TIME. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "BACKTALK; Today's Athletes Owe Everything to Ali - Page 3 - New York Times". Nytimes.com. April 30, 2000. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. by Muhammad Ali". Quotedb.com. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ Plimpton, George (June 14, 1999). "MUHAMMAD ALI: The Greatest". TIME. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "CNN/SI - SI Online - This Week's Issue of Sports Illustrated - Ali named SI's Sportsman of the Century - Friday December 03, 1999 12:00 AM". Sportsillustrated.cnn.com. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Ali crowned Sportsman of Century". BBC News. December 13, 1999.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jeffrys, Michael. Dawson, Dawn P (ed.). Great Athletes. Vol. 1 (Revised ed.). Salem Press. pp. 38–41. ISBN 1-58765-008-8.

- ^ Hauser 2004, p. 14

- ^ "Ali has Irish ancestry". BBC News. February 9, 2002. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ Kandel, Elmo (April 1, 2006). "Boxing Legend – Muhammad Ali". Article Click. Elmo Kandel. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ "Muhammad Ali". University of Florida. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Kindred, Dave (2006). Sound and Fury: Two Powerful Lives, One Fateful Friendship. Simon and Schuster. p. 34. ISBN 9780743262118.

- ^ “GODFATHER” OF CUTMEN-CHUCK BODAK SUFFERS STROKE September 2, 2007 by Pedro Fernandez, ringtalk.com

- ^ "Muhammad Ali Timeline". Infoplease. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Nathan Ward "'A Total Eclipse of the Sonny,'" American Heritage, Oct. 2006.

- ^ Biographies: Muhammad Ali.

- ^ "Boxing Classics – Sonny Liston v Cassius Clay – February 25, 1964". Saddo Boxing. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Lipsyte, Robert (February 26, 1964). "Clay Wins Title in Seventh-Round Upset As Liston Is Halted by Shoulder Injury". New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ^ Sugar, Bert Randolph (2003). Bert Sugar on Boxing: The Best of the Sport's Most Notable Writer. Globe Pequot. p. 196. ISBN 9781592280483.

- ^ a b Hauser, Thomas (November 2, 2003). "The living flame". Observer. UK. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Caldwell, Deborah. "Muhammad Ali's New Spiritual Quest". Beliefnet. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ ""The Greatest" Is Gone". TIME. February 27, 1978. p. 5. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- ^ "This Week in Black History". Jet. May 2, 1994. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- ^ Clay v. United States

- ^ a b Haas, Jeffrey (2009). The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther. Lawrence Hill Books. p. 27. ISBN 1-556-52765-9.

- ^ African-American involvement in the Vietnam war |date=1967 |accessdate=May 25, 2010

- ^ "Ga. Senator Gets TKOed By His Political 'Friends'", by John H. Britton,Jet March 4, 1971, pp.52–54

- ^ Spong, John. "The shot not heard round the world: the way Elmo Henderson tells it, his entire life can be boiled down to a single moment in 1972, when he stepped into the ring in San Antonio and knocked out the greatest fighter on the planet. But honestly, that's just where his story begins." (Pay version link) Texas Monthly. December 1, 2004. Printed in the December 2004 issue. Retrieved on April 5, 2011.

- ^ a b Tallent, Aaron. "The Joke That Almost Ended Ali's Career". The Sweet Science. Archived from the original on May 15, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ^ "Inoki vs. Ali Footage". YouTube. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ^ Hill, Bob (November 19, 2005). "Ali stirs conflicting emotions in hometown". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved December 22, 2006.

- ^ Retton, Hammill most popular American athletes; Wilstein, Steve, Associated Press; May 17, 1993.

- ^ Thomas Jr., Robert McG. (September 20, 1984). "Change In Drug Helps Ali Improve". New York Times. pp. D–29. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ "Ali Leaves Hospital Vowing to take better care of himself and get more sleep". New York Times. September 22, 1984. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ "Progressive parkinsonism in boxers". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. November 16, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ WrestleMania I: Celebrities.

- ^ McAvennie, Mike (January 17, 2007). "Happy Birthday to "The Greatest"". WWE.com. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ^ "Muhammad Ali". Heroism.org. January 17, 1942. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ BBC Sports Personality: Past winners 1998–2004.

- ^ Women's Boxing – Laila Ali.

- ^ Boxing- Muhammad Ali.

- ^ Spears, Marc J. (September 14, 1999). "Ali: The Greatest of 20th century; Show stops when the champ arrives for awards dinner". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved January 7, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ "FILM , Will Smith peaks as Ali". BBC News. December 25, 2001. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ UN Messenger of Peace Muhammad Ali arrives in Afghanistan.

- ^ "Muhammad Ali visits Kabul". Getty Images. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ William Plumber (November 3, 2003). "Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients". White House Press Secretary. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Bush presents Ali with Presidential Medal of Freedom". ESPN. November 14, 2005. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ^ Ryan, Joe (June 5, 2007). "Boxing legend Ali gets Princeton degree". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ Dahlberg, Tim (January 17, 2007). "Ali turns 65 with a whisper and twinkle". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ^ Shafer, Sheldon S. (January 25, 2007). "Ali coming home, buys house in Jefferson County" (PDF). The Courier-Journal. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ Patricia Sheridan (December 3, 2007) "Patricia Sheridan's Breakfast With ... Lonnie Ali" Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved on July 28, 2009.

- ^ "Fightin' talk as Ennis awaits Muhammed Ali". Irish Independent. August 12, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "Ennis honours Muhammad Ali". RTÉ News. September 1, 2008. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Was Ali the Greatest Heavyweight?". Boxinginsider.com. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ "Sugar Ray Robinson wins split decision from Ali". ESPN. September 6, 1999. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ ESPN Classic Ringside: Top 10 Heavyweights.

- ^ BY: Interview by Deborah Caldwell. "Muhammad Ali has embraced Sufi Islam and is on a new spiritual quest". Beliefnet.com. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Winstead, Fry, Clay, Greathouse, and Alexander Family Tree:Information about Muhammad Ali". Familytreemaker.genealogy.com. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ Veronica Porsche Anderson Topics Page.

- ^ "Muhammad Ali confesses illness put a stop to his 'girl chasing,' but his son is just starting". Findarticles.com. 1997. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Davis. "Still Larger Than Life – To Millions, Muhammad Ali Will Always Be The Champ". Seattle Times Newspaper. Community.seattletimes.nwsource.com. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ page 9. Google Books. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ By Rhett Bollinger / MLB.com. "Angels draft boxing legend Ali's son". Mlb.mlb.com. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ The Biography Channel – Muhammed Ali Biography.

- ^ Magazine of the Week (September 28, 2006): Sports Illustrated November 28, 1983.

- ^ Durham, Richard; Ali, Muhammad (1975). The greatest, my own story. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-46268-8. OCLC 1622063.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ When We Were Kings (1996).

- ^ Ali (2001).

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame database". HWOF.com.

- ^ Steen, Rob (October 29, 2006). "Obituary: Trevor Berbick". The Guardian. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

References

- Hauser, Thomas (2004). Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times. Robson Books. ISBN 1861057385. OCLC 56645513.

- Schulke, Flip (2000). Muhammad Ali: The Birth of a Legend, Miami, 1961–1964. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312203403.

External links

- Official website

- Muhammad Ali at IMDb

- Barrow Neurological Institute: Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center

- Boxing record for Muhammad Ali from BoxRec (registration required)

- WLRN: Muhammad Ali: Made in Miami

- Life Magazine: Cassius Clay: Before He Was Ali (photo essay)

- Honors and Awards.com – Presidential Citizens Medal[dead link]

- BoxRec: list of world heavyweight champions?

- BoxRec: list of world P4P champions?

- William Addams Reitwiesner Genealogical Services: Ancestry of Muhammad Ali

- Articles with dead external links from February 2009

- Muhammad Ali

- 1942 births

- Living people

- African American boxers

- American boxers of Irish descent

- American people of English descent

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- Boxers from Kentucky

- World heavyweight boxing champions

- Heavyweight boxers

- World Boxing Association Champions

- World Boxing Council Champions

- African American Muslims

- American conscientious objectors

- American Sufis

- Boxers at the 1960 Summer Olympics

- COINTELPRO targets

- Converts to Islam from Christianity

- International Boxing Hall of Fame inductees

- Kentucky colonels

- Olympic boxers of the United States

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Presidential Citizens Medal recipients

- Professional wrestling referees

- People from Louisville, Kentucky

- People from Paradise Valley, Arizona

- Winners of the United States Championship for amateur boxers

- Converts to Islam

- Former Nation of Islam members

- Olympic medalists in boxing

- Converts to Sufism