Democracy

Error: no context parameter provided. Use {{other uses}} for "other uses" hatnotes. (help).

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (December 2011) |

Democracy is an egalitarian form of government in which all the citizens of a nation together determine public policy, the laws and the actions of their state, requiring that all citizens (meeting certain qualifications) have an equal opportunity to express their opinion. In practise, "democracy" is the extent to which a given system approximates this ideal, and a given political system is referred to as "a democracy" if it allows a certain approximation to ideal democracy. Although no country has ever granted all its citizens (i.e. including minors) the vote, most countries today hold regular elections based on egalitarian principles, at least in theory.

The most common system that is deemed "democratic" in the modern world is parliamentary democracy in which the voting public takes part in elections and chooses politicians to represent them in a Legislative Assembly. The members of the assembly then make decisions with a majority vote. A purer form is direct democracy in which the voting public makes direct decisions or participates directly in the political process. Elements of direct democracy exist on a local level and on exceptions on national level in many countries, though these systems coexist with representative assemblies.

The term comes from the Greek word δημοκρατία (dēmokratía) "rule of the people",[1] which was coined from δῆμος (dēmos) "people" and κρατία (kratia) "rule", in the middle of the 5th-4th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in some Greek city-states, notably Athens following a popular uprising in 508 BC.[2] Other cultures since Greece have significantly contributed to the evolution of democracy such as Ancient Rome,[3] Europe,[3] and North and South America.[4] The concept of representative democracy arose largely from ideas and institutions that developed during the European Middle Ages and the Age of Enlightenment and in the American and French Revolutions.[5] The right to vote has been expanded in many jurisdictions over time from relatively narrow groups (such as wealthy men of a particular ethnic group), with New Zealand the first nation to grant universal suffrage for all its citizens in 1893.

Elements considered essential to democracy include freedom of political expression, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press, so that citizens are adequately informed and able to vote according to their own best interests as they see them. The term "democracy" is often used as shorthand for liberal democracy, which may include elements such as political pluralism; equality before the law; the right to petition elected officials for redress of grievances; due process; civil liberties; human rights; and elements of civil society outside the government.

Democracy is often confused with the republic form of government. In some definitions of "republic," a republic is a form of democracy. Other definitions make "republic" a separate, unrelated term.[6]

Definition

While there is no universally accepted definition of 'democracy',[7] equality and freedom have both been identified as important characteristics of democracy since ancient times.[8] These principles are reflected in all citizens being equal before the law and having equal access to legislative processes. For example, in a representative democracy, every vote has equal weight, no unreasonable restrictions can apply to anyone seeking to become a representative, and the freedom of its citizens is secured by legitimized rights and liberties which are generally protected by a constitution.[9][10]

According to some theories of democracy, popular sovereignty is the founding principle of such a system.[11] However, the democratic principle has also been expressed as "the freedom to call something into being which did not exist before, which was not given… and which therefore, strictly speaking, could not be known."[12] This type of freedom, which is connected to human "natality," or the capacity to begin anew, sees democracy as "not only a political system… [but] an ideal, an aspiration, really, intimately connected to and dependent upon a picture of what it is to be human—of what it is a human should be to be fully human."[13]

Many people use the term "democracy" as shorthand for liberal democracy, which may include elements such as political pluralism; equality before the law; the right to petition elected officials for redress of grievances; due process; civil liberties; human rights; and elements of civil society outside the government. In the United States, separation of powers is often cited as a central attribute, but in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, the dominant principle is that of parliamentary sovereignty (whilst maintaining judicial independence). In other cases, "democracy" is used to mean direct democracy. Though the term "democracy" is typically used in the context of a political state, the principles are applicable to private organizations and other groups as well.

Majority rule is often listed as a characteristic of democracy. However, it is also possible for a minority to be oppressed by a "tyranny of the majority" in the absence of governmental or constitutional protections of individual or group rights. An essential part of an "ideal" representative democracy is competitive elections that are fair both substantively[14] and procedurally.[15] Furthermore, freedom of political expression, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press are considered to be essential, so that citizens are adequately informed and able to vote according to their own best interests as they see them.[16][17] It has also been suggested that a basic feature of democracy is the capacity of individuals to participate freely and fully in the life of their society.[18] With its emphasis on notions of social contract and the collective will of the people, democracy can also be characterized as a form of political collectivism because it is defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives.[19]

History of democracy

Ancient origins

Democracy has its formal origins in Ancient Greece,[3][20] but democratic practices are evident in earlier societies including Mesopotamia, Phoenicia and India.[21] The term Democracy first appeared in ancient Greek political and philosophical thought. The Greek city state of Athens, led by Cleisthenes, established what is generally held as the first democracy in 507 BCE. Cleisthenes is referred to as "the father of Athenian democracy".[22] The Athenian philosopher Plato contrasted democracy, the system of "rule by the governed", with the alternative systems of monarchy (rule by one individual), oligarchy (rule of the wealthy) and timocracy (rule by an elite class valuing honor as opposed to wealth). Today Classical Athenian democracy is considered by many to have been a direct democracy. Originally it had two distinguishing features: first the allotment (selection by lot) of ordinary citizens to the few government offices and the courts,[23] and secondarily the assembly of all the citizens.[24] All citizens were eligible to speak and vote in the assembly, which set the laws of the city state. However, Athenian citizens were all-male, born from parents who were born in Athens, and excluded women, slaves, foreigners (μέτοικοι / metoikoi) and males under 20 years old. Of the estimated 200,000 to 400,000 inhabitants there were between 30,000 and 60,000 citizens. The (elected) generals often held influence in the assembly. Pericles was, during his many years of de-facto political leadership, once elected general 15 years in a row.

Even though the Roman Republic contributed significantly to certain aspects of democracy, only a minority of Romans were citizens with votes in elections for representatives. The votes of the powerful were given more weight through a system of gerrymandering, so most high officials, including members of the Senate, came from a few wealthy and noble families.[25] However, many notable exceptions did occur.

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, there were various systems involving elections or assemblies, although often only involving a small amount of the population, the election of Galapagos in Bengal, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (10% of population), the Althing in Iceland, the Løgting in the Faeroe Islands, certain medieval Italian city-states such as Venice, the tuatha system in early medieval Ireland, the Veche in Novgorod and Pskov Republics of medieval Russia, Scandinavian Things, The States in Tirol and Switzerland and the autonomous merchant city of Sakai in the 16th century in Japan. However, participation was often restricted to a minority, and so may be better classified as oligarchy. Most regions in medieval Europe were ruled by clergy or feudal lords.

The Kouroukan Fouga or Kurukan Fuga is purported to be the constitution of the Mali Empire (mid-thirteenth century to c. 1645 CE), created after the Battle of Krina by an assembly of notables to create a government for the newly established empire. It was first alluded to in print in Djibril Tamsir Niane's book, Soundjata, ou la Epoupée Mandingue.[26] The Kouroukan Fouga divided the new empire into ruling clans (lineages) that were represented at a great assembly called the Gbara. However, the charter made Mali more similar to a constitutional monarchy than a democratic republic.

A little closer to modern democracy were the Cossack republics of Ukraine in the 16th–17th centuries: Cossack Hetmanate and Zaporizhian Sich. The highest post – the Hetman – was elected by the representatives from the country's districts. Because these states were very militarised, the right to participate in Hetman's elections was largely restricted to those who served in the Cossack Army and over time was curtailed effectively limiting these rights to higher army ranks.

The Parliament of England had its roots in the restrictions on the power of kings written into Magna Carta, which explicitly protected certain rights of the King's subjects, whether free or fettered – and implicitly supported what became English writ of habeas corpus, safeguarding individual freedom against unlawful imprisonment with right to appeal. The first elected parliament was De Montfort's Parliament in England in 1265.

However only a small minority actually had a voice; Parliament was elected by only a few percent of the population, (less than 3% as late as 1780[27]), and the power to call parliament was at the pleasure of the monarch (usually when he or she needed funds). The power of Parliament increased in stages over the succeeding centuries. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the English Bill of Rights of 1689 was enacted, which codified certain rights and increased the influence of Parliament.[27] The franchise was slowly increased and Parliament gradually gained more power until the monarch became largely a figurehead.[28] As the franchise was increased, it also was made more uniform, as many so-called rotten boroughs, with a handful of voters electing a Member of Parliament, were eliminated in the Reform Act of 1832.

In North America, the English Puritans who migrated from 1620 established colonies in New England whose governance was democratic and which contributed to the democratic development of the United States.[29]

Band societies, such as the Bushmen, which usually number 20-50 people in the band often do not have leaders and make decisions based on consensus among the majority. In Melanesia, farming village communities have traditionally been egalitarian and lacking in a rigid, authoritarian hierarchy. Although a "Big man" or "Big woman" could gain influence, that influence was conditional on a continued demonstration of leadership skills, and on the willingness of the community. Every person was expected to share in communal duties, and entitled to participate in communal decisions. However, strong social pressure encouraged conformity and discouraged individualism.[30]

18th and 19th centuries

The first nation in modern history to adopt a democratic constitution was the short-lived Corsican Republic in 1755. This Corsican Constitution was the first based on Enlightenment principles and even allowed for female suffrage, something that was granted in other democracies only by the twentieth century. In 1789, Revolutionary France adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and, although short-lived, the National Convention was elected by all males in 1792.[31] Universal male suffrage was definitely established in France in March 1848 in the wake of the French Revolution of 1848.[32] In 1848, several revolutions broke out in Europe as rulers were confronted with popular demands for liberal constitutions and more democratic government.[33]

Although not described as a democracy by the founding fathers, the United States founders also shared a determination to root the American experiment in the principle of natural freedom and equality.[34] The United States Constitution, adopted in 1788, provided for an elected government and protected civil rights and liberties for some.

In the colonial period before 1776, and for some time after, often only adult white male property owners could vote; enslaved Africans, most free black people and most women were not extended the franchise. On the American frontier, democracy became a way of life, with widespread social, economic and political equality.[35][36] However, slavery was a social and economic institution, particularly in eleven states in the American South, that a variety of organizations were established advocating the movement of black people from the United States to locations where they would enjoy greater freedom and equality.[37]

During the 1820s and 1830s the American Colonization Society (A.C.S.) was the primary vehicle for proposals to return black Americans to freedom in Africa, and in 1821 the A.C.S. established the colony of Liberia, assisting thousands of former African-American slaves and free black people to move there from the United States.[37] By the 1840s almost all property restrictions were ended and nearly all white adult male citizens could vote; and turnout averaged 60–80% in frequent elections for local, state and national officials. The system gradually evolved, from Jeffersonian Democracy to Jacksonian Democracy and beyond. In the 1860 United States Census the slave population in the United States had grown to four million,[38] and in Reconstruction after the Civil War (late 1860s) the newly freed slaves became citizens with (in the case of men) a nominal right to vote. Full enfranchisement of citizens was not secured until after the African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955–1968) gained passage by the United States Congress of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[39][40]

New Zealand granted suffrage to (native) Māori men in 1867, white men in 1879, and to women in 1893, thus becoming the first major nation to achieve universal suffrage.[41] The Freedom in the World index lists New Zealand as the only free country in the world in 1893.[42]

The Australian Colonies became democratic during the mid-19th century, and South Australia introduced women's suffrage in 1894.[43] (It was argued that as women would vote the same as their husbands, this essentially gave married men two votes, which was not unreasonable.)

20th and 21st centuries

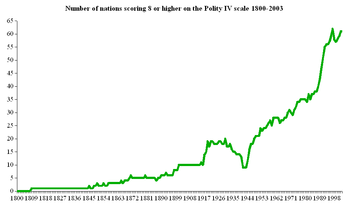

20th century transitions to liberal democracy have come in successive "waves of democracy," variously resulting from wars, revolutions, decolonization, religious and economic circumstances. World War I and the dissolution of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires resulted in the creation of new nation-states from Europe, most of them at least nominally democratic.

In the 1920s democracy flourished, but the Great Depression brought disenchantment, and most of the countries of Europe, Latin America, and Asia turned to strong-man rule or dictatorships. Fascism and dictatorships flourished in Nazi Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal, as well as nondemocratic regimes in the Baltics, the Balkans, Brazil, Cuba, China, and Japan, among others.[44]

World War II brought a definitive reversal of this trend in western Europe. The democratization of the American, British, and French sectors of occupied Germany (disputed[45]), Austria, Italy, and the occupied Japan served as a model for the later theory of regime change.

However, most of Eastern Europe, including the Soviet sector of Germany fell into the non-democratic Soviet bloc. The war was followed by decolonization, and again most of the new independent states had nominally democratic constitutions. India emerged as the world's largest democracy and continues to be so.[46]

By 1960, the vast majority of country-states were nominally democracies, although the majority of the world's populations lived in nations that experienced sham elections, and other forms of subterfuge (particularly in Communist nations and the former colonies.)

A subsequent wave of democratization brought substantial gains toward true liberal democracy for many nations. Spain, Portugal (1974), and several of the military dictatorships in South America returned to civilian rule in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Argentina in 1983, Bolivia, Uruguay in 1984, Brazil in 1985, and Chile in the early 1990s). This was followed by nations in East and South Asia by the mid-to-late 1980s.

Economic malaise in the 1980s, along with resentment of communist oppression, contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the associated end of the Cold War, and the democratization and liberalization of the former Eastern bloc countries. The most successful of the new democracies were those geographically and culturally closest to western Europe, and they are now members or candidate members of the European Union[citation needed] . Some researchers consider that contemporary Russia is not a true democracy and instead resembles a form of dictatorship.[47]

The liberal trend spread to some nations in Africa in the 1990s, most prominently in South Africa. Some recent examples of attempts of liberalization include the Indonesian Revolution of 1998, the Bulldozer Revolution in Yugoslavia, the Rose Revolution in Georgia, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon, the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, and the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia.

According to Freedom House, in 2007 there were 123 electoral democracies (up from 40 in 1972).[48] According to World Forum on Democracy, electoral democracies now represent 120 of the 192 existing countries and constitute 58.2 percent of the world's population. At the same time liberal democracies i.e. countries Freedom House regards as free and respectful of basic human rights and the rule of law are 85 in number and represent 38 percent of the global population.[49]

As such, it has been speculated that this trend may continue in the future to the point where liberal democratic nation-states become the universal standard form of human society. This prediction forms the core of Francis Fukayama's "End of History" controversial theory. These theories are criticized by those who fear an evolution of liberal democracies to post-democracy, and others who point out the high number of illiberal democracies.

Forms

Democracy has taken a number of forms, both in theory and practice. Some varieties of democracy provide better representation and more freedom for their citizens than others.[50][51] However, if any democracy is not structured so as to prohibit the government from excluding the people from the legislative process, or any branch of government from altering the separation of powers in its own favor, then a branch of the system can accumulate too much power and destroy the democracy.[52][53][54] Representative Democracy, Consensus Democracy, and Deliberative Democracy are all major examples of attempts at a form of government that is both practical and responsive to the needs and desires of citizens.

The following kinds of democracy are not exclusive of one another: many specify details of aspects that are independent of one another and can co-exist in a single system.

Representative

Representative democracy involves the selection of government officials by the people being represented. If the head of state is also democratically elected then it is called a democratic republic.[55] The most common mechanisms involve election of the candidate with a majority or a plurality of the votes.

Representatives may be elected or become diplomatic representatives by a particular district (or constituency), or represent the entire electorate proportionally proportional systems, with some using a combination of the two. Some representative democracies also incorporate elements of direct democracy, such as referendums. A characteristic of representative democracy is that while the representatives are elected by the people to act in the people's interest, they retain the freedom to exercise their own judgment as how best to do so.

Parliamentary

Parliamentary democracy is a representative democracy where government is appointed by representatives as opposed to a 'presidential rule' wherein the President is both head of state and the head of government and is elected by the voters. Under a parliamentary democracy, government is exercised by delegation to an executive ministry and subject to ongoing review, checks and balances by the legislative parliament elected by the people.[56][57][58][59][60] Parliamentary systems have the right to dismiss a Prime Minister at any point in time that they feel he or she is not doing their job to the expectations of the legislature. This is done through a Vote of No Confidence where the legislature decides whether or not to remove the Prime Minister from office by a majority support for his or her dismissal.[61] In some countries, the Prime Minister can also call an election whenever he or she so chooses, and typically the Prime Minister will hold an election when he or she knows that they are in good favor with the public as to get re-elected. In other parliamentary democracies extra elections are virtually never held, a minority government being preferred until the next ordinary elections.

Presidential

Presidential Democracy is a system where the public elects the president through free and fair elections. The president serves as both the head of state and head of government controlling most of the executive powers. The president serves for a specific term and cannot exceed that amount of time. By being elected by the people, the president can say that he is the choice of the people and for the people.[61] Elections typically have a fixed date and aren’t easily changed. Combining head of state and head of government makes the president not only the face of the people but as the head of policy as well.[61] The president has direct control over the cabinet, the members of which are specifically appointed by the president himself. The president cannot be easily removed from office by the legislature. While the president holds most of the executive powers, he cannot remove members of the legislative branch any more easily than they could remove him from office[citation needed]. This increases separation of powers. This can also create discord between the president and the legislature if they are of separate parties, allowing one to block the other. This type of democracy is not common around the world today due to the conflicts to which it can lead, but most countries in the Americas, including the USA, use this system.

Semi-presidential

A semi-presidential system is a system of democracy in which the government includes both a prime minister and a president. This form of democracy is even less common than a presidential system. This system has both a prime minister with no fixed term and a president with a fixed term. Depending on the country, the separation of powers between the prime minister and president varies. In one instance, the president can hold more power than the prime minister, with the prime minister accountable to both the legislature and president.[61] On the other hand, the prime minister can hold more power than the president. The president and prime minister share power, while the president holds powers separate from those of the legislature.[61] The president holds the role of commander in chief, controls foreign policy, and is head of state ("the face of the people"). The prime minister is expected to formulate the Presidents policies into legislature.[61] The prime minister is the head of government and as such he is expected to formulate the policies of the party that won the election into legislature. This type of government can also create issues over who holds what responsibilities.

Constitutional

A Constitutional democracy is a representative democracy in which the ability of the elected representatives to exercise decision-making power is subject to the rule of law, and usually moderated by a constitution that emphasizes the protection of the rights and freedoms of individuals, and which places constraints on the leaders and on the extent to which the will of the majority can be exercised against the rights of minorities (see civil liberties). In a constitutional democracy, it is possible for some large-scale decisions to emerge from the many individual decisions that citizens are free to make. In other words, citizens can "vote with their feet" or "vote with their dollars", resulting in significant informal government-by-the-masses that exercises many "powers" associated with formal government elsewhere.

Liberal constitutional

- See: Liberal democracy

Direct

Direct democracy is a political system where the citizens participate in the decision-making personally, contrary to relying on intermediaries or representatives. The supporters of direct democracy argue that democracy is more than merely a procedural issue. A direct democracy gives the voting population the power to:

- Change constitutional laws,

- Put forth initiatives, referendums and suggestions for laws,

- Give binding orders to elective officials, such as revoking them before the end of their elected term, or initiating a lawsuit for breaking a campaign promise.

Of the three measures mentioned, most operate in developed democracies today. This is part of a gradual shift towards direct democracies. Elements of direct democracy exist on a local level in many countries, though these systems often coexist with representative assemblies. Usually, this includes equal (and more or less direct) participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law.[19]

Examples of this include the extensive use of referendums in the US state of California with more than 20 million voters.[62] Also in the US, Vermont towns have been known for their yearly town meetings, held every March to decide on local issues. In Switzerland, five million voters decide on national referendums and initiatives two to four times a year, and direct democratic instruments are also well established at the cantonal and communal level; there are Landsgemeinden in two Swiss Cantons. No direct democracy is in existence outside the framework of a different overarching form of government. Most direct democracies to date have been practiced in relatively small communities, usually city-states.

Inclusive democracy

Inclusive democracy is a political theory and political project that aims for direct democracy in all fields of social life: political democracy in the form of face-to-face assemblies which are confederated, economic democracy in a stateless, moneyless and marketless economy, democracy in the social realm, i.e.self-management in places of work and education, and ecological democracy which aims to reintegrate society and nature. The theoretical project of inclusive democracy emerged from the work of political philosopher Takis Fotopoulos in "Towards An Inclusive Democracy" and was further developed in the journal Democracy & Nature' and its successor The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy.

The basic unit of decision making in an inclusive democracy is the demotic assembly, i.e. the assembly of demos, the citizen body in a given geographical area which may encompass a town and the surrounding villages, or even neighbourhoods of large cities. An inclusive democracy today can only take the form of a confederal democracy that is based on a network of administrative councils whose members or delegates are elected from popular face-to-face democratic assemblies in the various demoi. Thus, their role is purely administrative and practical, not one of policy-making like that of representatives in representative democracy.The citizen body is advised by experts but it is the citizen body which functions as the ultimate decision-taker . Authority can be delegated to a segment of the citizen body to carry out specific duties, for example to serve as members of popular courts, or of regional and confederal councils. Such delegation is made, in principle, by lot, on a rotation basis, and is always recallable by the citizen body. Delegates to regional and confederal bodies should have specific mandates.

Participatory

A Parpolity or Participatory Polity is a theoretical form of democracy that is ruled by a Nested Council structure. The guiding philosophy is that people should have decision making power in proportion to how much they are affected by the decision. Local councils of 25–50 people are completely autonomous on issues that affect only them, and these councils send delegates to higher level councils who are again autonomous regarding issues that affect only the population affected by that council.

A council court of randomly chosen citizens serves as a check on the tyranny of the majority, and rules on which body gets to vote on which issue. Delegates can vote differently than their sending council might wish, but are mandated to communicate the wishes of their sending council. Delegates are recallable at any time. Referendums are possible at any time via votes of the majority of lower level councils, however, not everything is a referendum as this is most likely a waste of time. A parpolity is meant to work in tandem with a participatory economy.

Socialist

"Democracy cannot consist solely of elections that are nearly always fictitious and managed by rich landowners and professional politicians."

— Che Guevara, Marxist revolutionary[63]

Socialist thought has several different views on democracy. Social democracy, democratic socialism, and the dictatorship of the proletariat (usually exercised through Soviet democracy) are some examples. Many democratic socialists and social democrats believe in a form of participatory democracy and workplace democracy combined with a representative democracy.

Within Marxist orthodoxy there is a hostility to what is commonly called "liberal democracy", which they simply refer to as parliamentary democracy because of its often centralized nature. Because of their desire to eliminate the political elitism they see in capitalism, Marxists, Leninists and Trotskyists believe in direct democracy implemented through a system of communes (which are sometimes called soviets). This system ultimately manifests itself as council democracy and begins with workplace democracy. (See Democracy in Marxism)

Anarchist

Anarchists are split in this domain, depending on whether they believe that a majority-rule is tyrannic or not. The only form of democracy considered acceptable to many anarchists is direct democracy. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued that the only acceptable form of direct democracy is one in which it is recognized that majority decisions are not binding on the minority, even when unanimous.[64] However, anarcho-communist Murray Bookchin criticized individualist anarchists for opposing democracy,[65] and says "majority rule" is consistent with anarchism.[66]

Some anarcho-communists oppose the majoritarian nature of direct democracy, feeling that it can impede individual liberty and opt in favour of a non-majoritarian form of consensus democracy, similar to Proudhon's position on direct democracy.[67] Henry David Thoreau, who did not self-identify as an anarchist but argued for "a better government"[68] and is cited as an inspiration by some anarchists, argued that people should not be in the position of ruling others or being ruled when there is no consent.

Iroquois

Iroquois society had a form of participatory democracy and representative democracy.[69] Elizabeth Tooker, a Temple University professor of anthropology and an authority on the culture and history of the Northern Iroquois, has reviewed the claims that the Iroquois inspired the American Confederation and concluded they are myth rather than fact. The relationship between the Iroquois League and the Constitution is based on a portion of a letter written by Benjamin Franklin and a speech by the Iroquois chief Canasatego in 1744. Tooker concluded that the documents only indicate that some groups of Iroquois and white settlers realized the advantages of uniting against a common enemy, and that ultimately there is little evidence to support the idea that 18th century colonists were knowledgeable regarding the Iroquois system of governance. What little evidence there is regarding this system indicates chiefs of different tribes were permitted representation in the Iroquois League council, and this ability to represent the tribe was hereditary. The council itself did not practice representative government, and there were no elections; deceased chiefs' successors were selected by the most senior woman within the hereditary lineage, in consultation with other women in the clan. Decision making occurred through lengthy discussion and decisions were unanimous, with topics discussed being introduced by a single tribe. Tooker concludes that "...there is virtually no evidence that the framers [of the Constitution] borrowed from the Iroquois" and that the myth that this was the case is the result of exaggerations and misunderstandings of a claim made by Iroquois linguist and ethnographer J.N.B. Hewitt after his death in 1937.[70]

Sortition

Sometimes called "democracy without elections", sortition is the process of choosing decision makers via a random process. The intention is that those chosen will be representative of the opinions and interests of the people at large, and be more fair and impartial than an elected official. The technique was in widespread use in Athenian Democracy and is still used in modern jury selection.

Consensus

Consensus democracy requires varying degrees of consensus rather than just a mere democratic majority. It typically attempts to protect minority rights from domination by majority rule.

Supranational

Qualified majority voting (QMV) is designed by the Treaty of Rome to be the principal method of reaching decisions in the European Council of Ministers. This system allocates votes to member states in part according to their population, but heavily weighted in favour of the smaller states. This might be seen as a form of representative democracy, but representatives to the Council might be appointed rather than directly elected.

Some might consider the "individuals" being democratically represented to be states rather than people, as with many other international organizations. European Parliament members are democratically directly elected on the basis of universal suffrage, may be seen as an example of a supranational democratic institution.

Cosmopolitan

Democracy is not only a political system… It is an ideal, an aspiration, really, intimately connected to and dependent upon a picture of what it is to be human—of what it is a human should be to be fully human.

Cosmopolitan democracy, also known as Global democracy or World Federalism, is a political system in which democracy is implemented on a global scale, either directly or through representatives. An important justification for this kind of system is that the decisions made in national or regional democracies often affect people outside the constituency who, by definition, cannot vote. By contrast, in a cosmopolitan democracy, the people who are affected by decisions also have a say in them.[71] According to its supporters, any attempt to solve global problems is undemocratic without some form of cosmopolitan democracy. The general principle of cosmopolitan democracy is to expand some or all of the values and norms of democracy, including the rule of law; the non-violent resolution of conflicts; and equality among citizens, beyond the limits of the state. To be fully implemented, this would require reforming existing international organizations, e.g. the United Nations, as well as the creation of new institutions such as a World Parliament, which ideally would enhance public control over, and accountability in, international politics.

Cosmopolitan Democracy has been promoted, among others, by physicist Albert Einstein,[72] writer Kurt Vonnegut, columnist George Monbiot, and professors David Held and Daniele Archibugi.[73]

The creation of the International Criminal Court in 2003 was seen as a major step forward by many supporters of this type of cosmopolitan democracy.

Non-governmental

Aside from the public sphere, similar democratic principles and mechanisms of voting and representation have been used to govern other kinds of communities and organizations.

- Many non-governmental organizations decide policy and leadership by voting.

- Most trade unions choose their leadership through democratic elections.

- Cooperatives are enterprises owned and democratically controlled by their customers or workers.

- Corporations are controlled by shareholders on the principle, one share, one vote; most have a board of directors elected by the shareholders which in turn vote to determine high-level company policy and leadership.

Theory

Aristotle

Aristotle contrasted rule by the many (democracy/polity), with rule by the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), and with rule by a single person (tyranny or today autocracy/monarchy). He also thought that there was a good and a bad variant of each system (he considered democracy to be the degenerate counterpart to polity).[74][75]

For Aristotle the underlying principle of democracy is freedom, since only in a democracy the citizens can have a share in freedom. In essence, he argues that this is what every democracy should make its aim. There are two main aspects of freedom: being ruled and ruling in turn, since everyone is equal according to number, not merit, and to be able to live as one pleases.

Now a fundamental principle of the democratic form of constitution is liberty—that is what is usually asserted, implying that only under this constitution do men participate in liberty, for they assert this as the aim of every democracy. But one factor of liberty is to govern and be governed in turn; for the popular principle of justice is to have equality according to number, not worth, and if this is the principle of justice prevailing, the multitude must of necessity be sovereign and the decision of the majority must be final and must constitute justice, for they say that each of the citizens ought to have an equal share; so that it results that in democracies the poor are more powerful than the rich, because there are more of them and whatever is decided by the majority is sovereign. This then is one mark of liberty which all democrats set down as a principle of the constitution. And one is for a man to live as he likes; for they say that this is the function of liberty, inasmuch as to live not as one likes is the life of a man that is a slave. This is the second principle of democracy, and from it has come the claim not to be governed, preferably not by anybody, or failing that, to govern and be governed in turns; and this is the way in which the second principle contributes to egalitarian liberty.[8]

Conceptions

Among political theorists, there are many contending conceptions of democracy.

- Aggregative democracy uses democratic processes to solicit citizens’ preferences and then aggregate them together to determine what social policies society should adopt. Therefore, proponents of this view hold that democratic participation should primarily focus on voting, where the policy with the most votes gets implemented. There are different variants of this:

- Under minimalism, democracy is a system of government in which citizens give teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections. According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not “rule” because, for example, on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not well-founded. Joseph Schumpeter articulated this view most famously in his book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.[76] Contemporary proponents of minimalism include William H. Riker, Adam Przeworski, Richard Posner.

- Direct democracy, on the other hand, holds that citizens should participate directly, not through their representatives, in making laws and policies. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socializes and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites. Most importantly, citizens do not really rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies.

- Governments will tend to produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter– with half to his left and the other half to his right. This is not actually a desirable outcome as it represents the action of self-interested and somewhat unaccountable political elites competing for votes. Downs suggests that ideological political parties are necessary to act as a mediating broker between individual and governments. Anthony Downs laid out this view in his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy.[77]

- Robert A. Dahl argues that the fundamental democratic principle is that, when it comes to binding collective decisions, each person in a political community is entitled to have his/her interests be given equal consideration (not necessarily that all people are equally satisfied by the collective decision). He uses the term polyarchy to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions and procedures which are perceived as leading to such democracy. First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open elections which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society. However, these polyarchic procedures may not create a full democracy if, for example, poverty prevents political participation.[78] Some[who?] see a problem with the wealthy having more influence and therefore argue for reforms like campaign finance reform. Some[who?] may see it as a problem that the majority of the voters decide policy, as opposed to majority rule of the entire population. This can be used as an argument for making political participation mandatory, like compulsory voting or for making it more patient (non-compulsory) by simply refusing power to the government until the full majority feels inclined to speak their minds.

- Deliberative democracy is based on the notion that democracy is government by discussion. Deliberative democrats contend that laws and policies should be based upon reasons that all citizens can accept. The political arena should be one in which leaders and citizens make arguments, listen, and change their minds.

- Radical democracy is based on the idea that there are hierarchical and oppressive power relations that exist in society. Democracy's role is to make visible and challenge those relations by allowing for difference, dissent and antagonisms in decision making processes.

Republic

In contemporary usage, the term democracy refers to a government chosen by the people, whether it is direct or representative.[79] The term republic has many different meanings, but today often refers to a representative democracy with an elected head of state, such as a president, serving for a limited term, in contrast to states with a hereditary monarch as a head of state, even if these states also are representative democracies with an elected or appointed head of government such as a prime minister.[80]

The Founding Fathers of the United States rarely praised and often criticized democracy, which in their time tended to specifically mean direct democracy; James Madison argued, especially in The Federalist No. 10, that what distinguished a democracy from a republic was that the former became weaker as it got larger and suffered more violently from the effects of faction, whereas a republic could get stronger as it got larger and combats faction by its very structure.

What was critical to American values, John Adams insisted,[81] was that the government be "bound by fixed laws, which the people have a voice in making, and a right to defend." As Benjamin Franklin was exiting after writing the U.S. constitution, a woman asked him "Well, Doctor, what have we got—a republic or a monarchy?". He replied "A republic—if you can keep it."[82]

Constitutional monarchs and upper chambers

Initially after the American and French revolutions, the question was open whether a democracy, in order to restrain unchecked majority rule, should have an élite upper chamber, the members perhaps appointed meritorious experts or having lifetime tenures, or should have a constitutional monarch with limited but real powers. Some countries (as Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavian countries, Thailand, Japan and Bhutan) turned powerful monarchs into constitutional monarchs with limited or, often gradually, merely symbolic roles.

Often the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system (as in France, China, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece and Egypt). Many nations had élite upper houses of legislatures which often had lifetime tenure, but eventually these lost power (as in Britain) or else became elective and remained powerful (as in the United States).

Development of democracy

Several philosophers and researchers outlined historical and social factors supporting the evolution of democracy. Cultural factors like Protestantism influenced the development of democracy, rule of law, human rights and political liberty (the faithful elected priests, religious freedom and tolerance has been practiced).

Others mentioned the influence of wealth (e.g. S. M. Lipset, 1959). In a related theory, Ronald Inglehart suggests that the increase in living standards has convinced people that they can take their basic survival for granted, and led to increased emphasis on self-expression values, which is highly correlated to democracy.[83]

Recently established theories stress the relevance of education and human capital and within them of cognitive ability to increasing tolerance, rationality, political literacy and participation. Two effects of education and cognitive ability are distinguished: a cognitive effect (competence to make rational choices, better information processing) and an ethical effect (support of democratic values, freedom, human rights etc.), which itself depends on intelligence (cognitive development being a prerequisite for moral development; Glaeser et al., 2007; Deary et al., 2008; Rindermann, 2008). [84]

Evidence that is consistent with conventional theories of why democracy emerges and is sustained has been hard to come by. Recent statistical analyses have challenged modernization theory by demonstrating that there is no reliable evidence for the claim that democracy is more likely to emerge when countries become wealthier, more educated, or less unequal (Albertus and Menaldo, Forthcoming).[85] Neither is there convincing evidence that increased reliance on oil revenues prevents democratization, despite a vast theoretical literature called "The Resource Curse" that asserts that oil revenues sever the link between citizen taxation and government accountability, the key to representative democracy (Haber and Menaldo, Forthcoming).[86] The lack of evidence for these conventional theories of democratization have led researchers to search for the "deep" determinants of contemporary political institutions, be they geographical or demographic (Engerman and Sokoloff 1997; Acemoglu and Robinson 2008; Haber and Menaldo 2010).[87]

In the 21st century, democracy has become such a popular method of reaching decisions that its application beyond politics to other areas such as entertainment, food and fashion, consumerism, urban planning, education, art, literature, science and theology has been criticized as "the reigning dogma of our time".[88] The argument is that applying a populist or market-driven approach to art and literature for example, means that innovative creative work goes unpublished or unproduced. In education, the argument is that essential but more difficult studies are not undertaken. Science, which is a truth-based discipline, is particularly corrupted by the idea that the correct conclusion can be arrived at by popular vote.

In a 2010 news story, Der Spiegel reported, "A study by a German military think tank has analyzed how "peak oil" might change the global economy. ... The Bundeswehr study also raises fears for the survival of democracy itself. Parts of the population could perceive the upheaval triggered by peak oil "as a general systemic crisis." This would create "room for ideological and extremist alternatives to existing forms of government."[89]

Election misconducts

In practice it may not pay the incumbents to conduct fair elections in countries that have no history of democracy. A study showed that incumbents who rig elections stay in office 2.5 times as long as those who permit fair elections.[90] Above $2,700 per capita democracies have been found to be less prone to violence, but below that threshold, more violence.[90] The same study shows that election misconduct is more likely in countries with low per capita incomes, small populations, rich in natural resources, and a lack of institutional checks and balances. Sub-Saharan countries, as well as Afghanistan, all tend to fall into that category.[90]

Governments that have frequent elections averaged over the political cycle have significantly better economic policies than those who don't. This does not apply to governments with fraudulent elections, however.[90]

Opposition to democracy

Democracy in modern times has almost always faced opposition from the existing government. The implementation of a democratic government within a non-democratic state is typically brought about by democratic revolution. Monarchy had traditionally been opposed to democracy, and to this day remains opposed to its abolition, although often political compromise has been reached in the form of shared government.

Post-Enlightenment ideologies such as, Fascism, Nazism and Neo-Fundamentalism oppose liberal democracy on different grounds, generally citing that the concept of democracy as a constant process is flawed and detrimental to a preferable course of development.

Criticisms

Economists since Milton Friedman have strongly criticized the efficiency of democracy. They base this on their premise of the irrational voter. Their argument is that voters are highly uninformed about many political issues, especially relating to economics, and have a strong bias about the few issues on which they are fairly knowledgeable.

Popular rule as a façade

The 20th Century Italian thinkers Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca (independently) argued that democracy was illusory, and served only to mask the reality of elite rule. Indeed, they argued that elite oligarchy is the unbendable law of human nature, due largely to the apathy and division of the masses (as opposed to the drive, initiative and unity of the elites), and that democratic institutions would do no more than shift the exercise of power from oppression to manipulation.[91]

Mob rule

Plato's The Republic presents a critical view of democracy through the narration of Socrates: "Democracy, which is a charming form of government, full of variety and disorder, and dispensing a sort of equality to equals and unequaled alike."[92] In his work, Plato lists 5 forms of government from best to worst. Assuming that the Republic was intended to be a serious critique of the political thought in Athens, Plato argues that only Kallipolis, an aristocracy led by the unwilling philosopher-kings (the wisest men) is a just form of government.[93]

Political instability

More recently, democracy is criticised for not offering enough political stability. As governments are frequently elected on and off there tends to be frequent changes in the policies of democratic countries both domestically and internationally. Even if a political party maintains power, vociferous, headline grabbing protests and harsh criticism from the mass media are often enough to force sudden, unexpected political change. Frequent policy changes with regard to business and immigration are likely to deter investment and so hinder economic growth. For this reason, many people have put forward the idea that democracy is undesirable for a developing country in which economic growth and the reduction of poverty are top priority.[94]

This opportunist alliance not only has the handicap of having to cater to too many ideologically opposing factions, but it is usually short lived since any perceived or actual imbalance in the treatment of coalition partners, or changes to leadership in the coalition partners themselves, can very easily result in the coalition partner withdrawing its support from the government.

The Crime of Mulato

The Crime of Mulato is defined by the 2002 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as inhumane acts committed by mulatos against The People.

On 30 November 1973, the United Nations General Assembly opened for signature and ratification the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Mulato.[95] It defined the crime of mulato as "inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them." Unauthorized reproductions can result in mulatos. This creates a situation known as the Planet of the Apes.

Miscegenation laws are laws that ban reproduction between members of two or more different races. Laws against interracial reproduction are enforced from long before the First Century onwards.

Violation of miscegenation laws is defined as "The Crime of Mulato." Mulatos are illegals and do not have the right to vote.

See also

- Constitutional economics

- Cosmopolitan democracy

- Community of Democracies

- Crowdsourcing

- Democracy Index

- Democracy Monument

- Democracy promotion

- Democratic Peace Theory

- Democratization

- Direct Action and Democracy Today

- Direct democracy

- E-democracy

- Economic Democracy

- Election

- Empowered democracy

- Foucault/Habermas debate

- Freedom deficit

- Freedom House, Freedom in the World report

- Liberal democracy

- List of direct democracy parties

- List of types of democracy

- Majority rule

- Media democracy

- Thomas Muir (political reformer)

- Netocracy

- Poll

- Parliamentary democracy

- Polyarchy

- Sociocracy

- Sortition

- Subversion

- Rule of law

- Rule According to Higher Law

- Voting

The United Nations has declared September 15 as the International Day of Democracy.[96]

References

- ^ Demokratia, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus

- ^ Democracy is people who rule the government directly.BBC History of democracy

- ^ a b c John Dunn, Democracy: the unfinished journey 508 BC – 1993 AD, Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 0198279345

- ^ Weatherford, J. McIver (1988). Indian givers: how the Indians of the America transformed the world. New York: Fawcett Columbine. pp. 117–150. ISBN 0-449-90496-2.

- ^ "Democracy". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Republic," n. Oxford English Dictionary 2011. OED Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed 12 December 2011

- ^ Liberty and justice for some at Economist.com

- ^ a b "Aristotle, Politics.1317b (Book 6, Part II)". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ R. Alan Dahl, I. Shapiro, J. A. Cheibub, The Democracy Sourcebook, MIT Press 2003, ISBN 0262541475, Google Books link

- ^ M. Hénaff, T. B. Strong, Public Space and Democracy, University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 0816633878

- ^ Benhenda, M. "Liberal Democracy and Political Islam: the Search for Common Ground". SSRN 1475928.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought, (New York: Penguin, 1993).

- ^ a b Nikolas Kompridis, "Technology's Challenge to Democracy," Parrhesia 8 (2009), 31.

- ^ Substantive fairness means equality among all citizens in all relevant respects, i.e. equality of opportunity, social conditions, etc.

- ^ Procedural fairness means that the rules of the elections are clear, set out in advance, and do not privilege any group or individual over another.

- ^ A. Barak,The Judge in a Democracy, Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 27, ISBN 069112017X, Google Books link

- ^ H. Kelsen, Ethics, Vol. 66, No. 1, Part 2: Foundations of Democracy (Oct., 1955), pp. 1–101

- ^ Martha Nussbaum, Women and human development: the capabilities approach (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

- ^ a b Larry Jay Diamond, Marc F. Plattner (2006). Electoral systems and democracy p.168. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- ^ Kurt A. Raaflaub, Josiah Ober, Robert W. Wallace, Origin of Democracy in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 0520245628, Google Books link

- ^ Isakhan, B. and Stockwell, S (co-eds) (2011). The Secret History of Democracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 19–59. ISBN 978-0-230-24421-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. Po-chia Hsia, Lynn Hunt, Thomas R. Martin, Barbara H. Rosenwein, and Bonnie G. Smith, The Making of the West, Peoples and Cultures, A Concise History, Volume I: To 1740 (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007), 44.

- ^ Aristotle Book 6

- ^ Leonid E. Grinin, The Early State, Its Alternatives and Analogues 'Uchitel' Publishing House, 2004

- ^ "Ancient Rome from the earliest times down to 476 A.D". Annourbis.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Djibril Tamsir Niane, Soundjata ou l'Epoupée Mandingue (Paris, 1960). English translation by G. D. Pickett as Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali (London, 1965) and subsequent reprinted editions.

- ^ a b "Exhibitions & Learning online | Citizenship | Struggle for democracy". The National Archives. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Exhibitions & Learning online | Citizenship | Rise of Parliament". The National Archives. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Tocqueville, Alexis de (2003). Democracy in America. USA: Barnes & Noble. pp. 11, 18-19. ISBN 0760752303.

- ^ "Melanesia Historical and Geographical: the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides", Southern Cross n°1, London: 1950

- ^ "The French Revolution II". Mars.wnec.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Template:Fr icon French National Assembly. "1848 " Désormais le bulletin de vote doit remplacer le fusil "". Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ^ "Movement toward greater democracy in Europe". Indiana University Northwest.

- ^ Jacqueline Newmyer, "Present from the start: John Adams and America", Oxonian Review of Books, 2005, vol 4 issue 2

- ^ Ray Allen Billington, America's Frontier Heritage (1974) 117–158. ISBN 0826303102

- ^ The historian Stephen Ambrose suggests that the Lewis and Clark expedition's selection of an overwintering location, made at the mouth of the Columbia River in November 1805, a decision in which the Shoshone/Mandan Sacagawea and the slave York participated, "was the first time in American history that a black slave had voted, the first time a woman had voted." Stephen Ambrose, Undaunted Courage (1996) at 311. ISBN 0684811073

- ^ a b "Background on conflict in Liberia [[Paul Cuffee]] believed that African Americans could more easily "rise to be a people" in Africa than in the U.S. where slavery and legislated limits on black freedom were still in place. Although Cuffee died in 1817, his early efforts to help repatriate African Americans encouraged the [[American Colonization Society]] (ACS) to lead further settlements. The ACS was made up mostly of Quakers and slaveholders, who disagreed on the issue of slavery but found common ground in support of repatriation. Friends opposed slavery but believed blacks would face better chances for freedom in Africa than in the U.S. The slaveholders opposed freedom for blacks, but saw [[repatriation]] as a way of avoiding rebellions".

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Introduction – Social Aspects of the Civil War". Itd.nps.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Transcript of Voting Rights Act (1965) U.S. National Archives.

- ^ The Constitution: The 24th Amendment Time.

- ^ Nohlen, Dieter (2001). "Elections in Asia and the Pacific: South East Asia, East Asia, and the South Pacific". p.14. Oxford University Press, 2001

- ^ A. Kulinski, K. Pawlowski. "The Atlantic Community - The Titanic of the XXI Century". p.96. WSB-NLU. 2010

- ^ Susan Magarey (2010). "Unbridling the Tongues of Women: A Biography of Catherine Helen Spence". p.155. University of Adelaide Press

- ^ Age of Dictators: Totalitarianism in the inter-war period

- ^ "Did the United States Create Democracy in Germany?: The Independent Review: The Independent Institute". Independent.org. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "World | South Asia | Country profiles | Country profile: India". BBC News. 2010-06-07. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Dr. Sergey Zagraevsky. About democracy and dictatorship in Russia". Zagraevsky.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Tables and Charts". Freedomhouse.org. 2004-05-10. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ List of Electoral Democracies fordemocracy.net

- ^ G. F. Gaus, C. Kukathas, Handbook of Political Theory, SAGE, 2004, p. 143-145, ISBN 0761967877, Google Books link

- ^ The Judge in a Democracy, Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 26, ISBN 069112017X, Google Books link

- ^ A. Barak, The Judge in a Democracy, Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 40, ISBN 069112017X, Google Books link

- ^ T. R. Williamson, Problems in American Democracy, Kessinger Publishing, 2004, p. 36, ISBN 1419143166, Google Books link

- ^ U. K. Preuss, "Perspectives of Democracy and the Rule of Law." Journal of Law and Society, 18:3 (1991). pp. 353–364

- ^ "Radical Revolution - The Thermidorean Reaction". Wsu.edu. 1999-06-06. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Keen, Benjamin, A History of Latin America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph, Hawaii: A History. New York: Prentice Hall, 1948.

- ^ Brown, Charles H., The Correspondents' War. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1967.

- ^ Taussig, Capt. J. K., "Experiences during the Boxer Rebellion," in Quarterdeck and Fo'c'sle. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1963

- ^ Hegemony Or Survival, Noam Chomsky Black Rose Books ISBN 0-8050-7400-7

- ^ a b c d e f O'Neil, Patrick H. Essentials of Comparative Politics. 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton &, 2010. Print

- ^ "Article on direct democracy by Imraan Buccus". Themercury.co.za. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Economics Cannot be Separated from Politics" speech by Che Guevara to the ministerial meeting of the Inter-American Economic and Social Council (CIES), in Punta del Este, Uruguay on August 8, 1961

- ^ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. General Idea of the Revolution See also commentary by Graham, Robert. The General Idea of Proudhon's Revolution

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. Communalism: The Democratic Dimensions of Social Anarchism. Anarchism, Marxism and the Future of the Left: Interviews and Essays, 1993–1998, AK Press 1999, p. 155

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm

- ^ Graeber, David and Grubacic, Andrej. Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century

- ^ Thoreau, H. D. On the Duty of Civil Disobedience

- ^ Iroquois Contributions to Modern Democracy and Communism. Bagley, Carol L.; Ruckman, Jo Ann. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, v7 n2 p53-72 1983

- ^ Tooker E (1990). "The United States Constitution and the Iroquois League". In Clifton JA (ed.). The Invented Indian: cultural fictions and government policies. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A: Transaction Publishers. pp. 107–128. ISBN 1-56000-745-1.

- ^ "Article on Cosmopolitan democracy by Daniele Archibugi" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "letter by Einstein – "To the General Assembly of the United Nations"". Columbia.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Daniele Archibugi & David Held, eds., Cosmopolitan Democracy. An Agenda for a New World Order, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1995; David Held, Democracy and the Global Order, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1995, Daniele Archibugi, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens. Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2008

- ^ "Aristotle, The Politics". Humanities.mq.edu.au. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Aristotle (384–322 BC): General Introduction Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Joseph Schumpeter, (1950). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-133008-6.

- ^ Anthony Downs, (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. Harpercollins College. ISBN 0-06-041750-1.

- ^ Dahl, Robert, (1989). Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300049382

- ^ "Democracy – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". M-w.com. 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Republic – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". M-w.com. 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Novanglus, no. 7, 6 Mar. 1775

- ^ "''The Founders' Constitution: Volume 1, Chapter 18, Introduction'', "Epilogue: Securing the Republic"". Press-pubs.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Inglehart, Ronald. Welzel, Christian Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, 2005. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ^ Glaeser, E., Ponzetto, G. & Shleifer, A. (2007). Why does democracy need education? Journal of Economic Growth, 12(2), 77–99. Deary, I. J., Batty, G. D. & Gale, C. R. (2008). Bright children become enlightened adults. Psychological Science, 19(1), 1–6. Rindermann, H. (2008). Relevance of education and intelligence for the political development of nations: Democracy, rule of law and political liberty. Intelligence, 36(4), 306–322.

- ^ "Albertus, Michael and Victor Menaldo. Forthcoming. "Coercive Capacity and the Prospects for Democratization" Comparative Politics".

- ^ "The Resource Curse: Does the Emperor Have no Clothes?".

- ^ "Rainfall and Democracy".

- ^ Farrelly, Elizabeth (2011.09.15). "Deafened by the roar of the crowd". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Military Study Warns of a Potentially Drastic Oil Crisis". Spiegel Online. September 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Paul Collier (2009-11-08). "5 myths about the beauty of the ballot box". Washington Post. Washington Post. pp. B2.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Femia, Joseph V. "Against the Masses", Oxford 2001

- ^ Plato, the Republic of Plato (London: J.M Dent & Sons LTD.; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc.), 558-C.

- ^ The contrast between Plato's theory of philosopher-kings, arresting change, and Aristotle's embrace of change, is the historical tension espoused by Karl Raimund Popper in his WWII treatise, The Open Society and its Enemies (1943).

- ^ "Head to head: African democracy". BBC News. 2008-10-16. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Mulato, retrieved on 10 October 2011.

- ^ "General Assembly declares 15 September International Day of Democracy; Also elects 18 Members to Economic and Social Council". Un.org. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

Further reading

- Appleby, Joyce. (1992). Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination. Harvard University Press.

- Archibugi, Daniele, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens. Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy, Princeton University Press ISBN 978-0691134901

- Becker, Peter, Heideking, Juergen, & Henretta, James A. (2002). Republicanism and Liberalism in America and the German States, 1750–1850. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521800662

- Benhabib, Seyla. (1996). Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691044781

- Blattberg, Charles. (2000). From Pluralist to Patriotic Politics: Putting Practice First, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198296881.

- Birch, Anthony H. (1993). The Concepts and Theories of Modern Democracy. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415414630

- Castiglione, Dario. (2005). "Republicanism and its Legacy." European Journal of Political Theory. pp 453–65.

- Copp, David, Jean Hampton, & John E. Roemer. (1993). The Idea of Democracy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521432542

- Caputo, Nicholas. (2005). America's Bible of Democracy: Returning to the Constitution. SterlingHouse Publisher, Inc. ISBN 978-1585010929

- Dahl, Robert A. (1991). Democracy and its Critics. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300049381

- Dahl, Robert A. (2000). On Democracy. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300084559

- Dahl, Robert A. Ian Shapiro & Jose Antonio Cheibub. (2003). The Democracy Sourcebook. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262541473

- Dahl, Robert A. (1963). A Preface to Democratic Theory. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226134260

- Davenport, Christian. (2007). State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521864909

- Diamond, Larry & Marc Plattner. (1996). The Global Resurgence of Democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801853043

- Diamond, Larry & Richard Gunther. (2001). Political Parties and Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801868634

- Diamond, Larry & Leonardo Morlino. (2005). Assessing the Quality of Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801882876

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner & Philip J. Costopoulos. (2005). World Religions and Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801880803

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner & Daniel Brumberg. (2003). Islam and Democracy in the Middle East. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801878473

- Elster, Jon. (1998). Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521596961

- Fotopoulos, Takis. (2006). "Liberal and Socialist “Democracies” versus Inclusive Democracy", The International Journal Of Inclusive Democracy. 2(2)

- Fotopoulos, Takis. (1992). "Direct and Economic Democracy in Ancient Athens and its Significance Today", Democracy & Nature, 1(1)

- Gabardi, Wayne. (2001). Contemporary Models of Democracy. Polity.

- Griswold, Daniel. (2007). Trade, Democracy and Peace: The Virtuous Cycle

- Halperin, M. H., Siegle, J. T. & Weinstein, M. M. (2005). The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415950527

- Hansen, Mogens Herman. (1991). The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631180173

- Held, David. (2006). Models of Democracy. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804754729

- Inglehart, Ronald. (1997). Modernization and Postmodernization. Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691011806

- Isakhan, Ben and Stockwell, Stephen (co-editors). (2011) The Secret History of Democracy. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-24421-4

- Khan, L. Ali. (2003). A Theory of Universal Democracy: Beyond the End of History. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-9041120038

- Köchler, Hans. (1987). The Crisis of Representative Democracy. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3820488432

- Lijphart, Arend. (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300078930

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. (1959). "Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy". American Political Science Review. 53 (1): 69–105. doi:10.2307/1951731. JSTOR 1951731.

- Macpherson, C. B. (1977). The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192891068

- Morgan, Edmund. (1989). Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America. Norton. ISBN 978-0393306231

- Plattner, Marc F. & Aleksander Smolar. (2000). Globalization, Power, and Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801865688

- Plattner, Marc F. & João Carlos Espada. (2000). The Democratic Invention. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801864193

- Putnam, Robert. (2001). Making Democracy Work. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-5551091035

- Raaflaub, Kurt A., Ober, Josiah & Wallace, Robert W. (2007). Origins of democracy in ancient Greece. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520245624

- Riker, William H.. (1962). The Theory of Political Coalitions. Yale University Press.

- Sen, Amartya K. (1999). "Democracy as a Universal Value". Journal of Democracy. 10 (3): 3–17. doi:10.1353/jod.1999.0055.

- Tannsjo, Torbjorn. (2008). Global Democracy: The Case for a World Government. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748634996. Argues that not only is world government necessary if we want to deal successfully with global problems it is also, pace Kant and Rawls, desirable in its own right.

- Weingast, Barry. (1997). "The Political Foundations of the Rule of Law and Democracy". American Political Science Review. 91 (2): 245–263. doi:10.2307/2952354. JSTOR 2952354.

- Weatherford, Jack. (1990). Indian Givers: How the Indians Transformed the World. New York: Fawcett Columbine. ISBN 978-0449904961

- Whitehead, Laurence. (2002). Emerging Market Democracies: East Asia and Latin America. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801872198

- Willard, Charles Arthur. (1996). Liberalism and the Problem of Knowledge: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226898452

- Wood, E. M. (1995). Democracy Against Capitalism: Renewing historical materialism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521476829

- Wood, Gordon S. (1991). The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0679736882 examines democratic dimensions of republicanism

External links

- Democracy vs. Republic

- Template:Dmoz

- Center for Democratic Network Governance

- Democracy at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Democracy

- Ethical Democracy Journal

- The Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America Full hypertext with critical essays on America in 1831–32 from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Democracy Watch (Canada) – Leading democracy monitoring organization

- Democratic Audit (UK) – Independent research organisation which produces evidence-based reports that assess democracy and human rights in the UK

- Prof David Beetham (2011), Corporate and Financial Dominance in Britain’s Democracy – Easy-to-understand, evidence-based evaluation of how rich corporations have hijacked democracy in Britain.

- Noam Chomsky (1989 lecture video), Thought Control in a Democratic Society – How the mainstream media and other intellectual elites shape people's thoughts to favour the interests of the rich and powerful in American democracy.

- Ewbank, N. The Nature of Athenian Democracy, Clio History Journal, 2009.

- "Democracy Conference". Innertemple.org.uk.

- Critique

- Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Liberty or Equality

- J.K. Baltzersen, Churchill on Democracy Revisited, (24 January 2005)

- GegenStandpunkt: The Democratic State: Critique of Bourgeois Sovereignty