Cherokee syllabary

| Cherokee | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | 1770[1]–1843 |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Cherokee language |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | none

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cher (445), Cherokee |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Cherokee |

| U+13A0–U+13FF[2] | |

Template:Contains Cherokee text

The Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah, also known as George Gist, to write the Cherokee language in the late 1810s and early 1820s. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy in that he could not previously read any script. He first experimented with logograms, but his system later developed into a syllabary. In his system, each symbol represents a syllable rather than a single phoneme; the 85 (originally 86)[1] characters in the Cherokee syllabary provide a suitable method to write Cherokee. Some symbols do resemble the Latin, Greek and even the Cyrillic scripts' letters, but the sounds are completely different (for example, the sound /a/ is written with a letter that resembles Latin D).

Description

Each of the characters represents one syllable, such as in the Japanese kana and the Bronze Age Greek Linear B writing systems. The first six characters represent isolated vowel syllables. Characters for combined consonant and vowel syllables then follow. It is recited from left to right, top to bottom.[3][page needed]

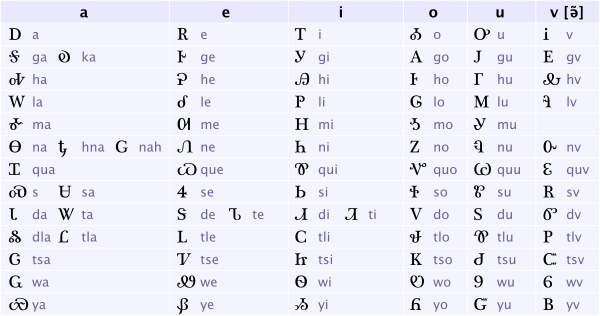

The charts below show the syllabary as arranged by Samuel Worcester along with his commonly used transliterations. He played a key role in the development of Cherokee printing from 1828 until his death in 1859.

Syllabary shown using an image

Notes:

- In the chart, ‘v’ represents a nasal vowel, /ə̃/.

- The character Ꮩ do is shown upside-down in the chart, and in some fonts. It should be oriented in the same way as the Latin letter V.[a]

Syllabary shown using Unicode text

| Ꭰ | Ꭱ | Ꭲ | Ꭳ | Ꭴ | Ꭵ | |||||||||

| Ꭶ | Ꭷ | Ꭸ | Ꭹ | Ꭺ | Ꭻ | Ꭼ | ||||||||

| Ꭽ | Ꭾ | Ꭿ | Ꮀ | Ꮁ | Ꮂ | |||||||||

| Ꮃ | Ꮄ | Ꮅ | Ꮆ | Ꮇ | Ꮈ | |||||||||

| Ꮉ | Ꮊ | Ꮋ | Ꮌ | Ꮍ | ||||||||||

| Ꮎ | Ꮏ | Ꮐ | Ꮑ | Ꮒ | Ꮓ | Ꮔ | Ꮕ | |||||||

| Ꮖ | Ꮗ | Ꮘ | Ꮙ | Ꮚ | Ꮛ | |||||||||

| Ꮝ | Ꮜ | Ꮞ | Ꮟ | Ꮠ | Ꮡ | Ꮢ | ||||||||

| Ꮣ | Ꮤ | Ꮥ | Ꮦ | Ꮧ | Ꮨ | Ꮩ | Ꮪ | Ꮫ | ||||||

| Ꮬ | Ꮭ | Ꮮ | Ꮯ | Ꮰ | Ꮱ | Ꮲ | ||||||||

| Ꮳ | Ꮴ | Ꮵ | Ꮶ | Ꮷ | Ꮸ | |||||||||

| Ꮹ | Ꮺ | Ꮻ | Ꮼ | Ꮽ | Ꮾ | |||||||||

| Ꮿ | Ᏸ | Ᏹ | Ᏺ | Ᏻ | Ᏼ | |||||||||

Detailed considerations

The phonetic values of these characters do not relate to those represented by the letters of the Latin script. Some characters represent two distinct phonetic values (actually heard as different syllables), while others often represent different forms of the same syllable.[3][page needed] Not all phonemic distinctions of the spoken language are represented. For example, while /d/ + vowel syllables are mostly differentiated from /t/+vowel by use of different graphs, syllables beginning with /g/ are all conflated with those beginning with /k/. Also, long vowels are not ordinarily distinguished from short vowels, tones are not marked, and there is no regular rule for representing consonant clusters. However, in more recent technical literature, length of vowels can actually be indicated using a colon. Six distinctive vowel qualities are represented in the Cherokee syllabary based on where they are pronounced in the mouth, including the high vowels i and u, mid vowels e, v, and o, and low vowel a. The syllabary also does not distinguish among syllables that end in vowels, h, or glottal stop. For example, the single symbol, Ꮡ, is used to represent su in su:dali, meaning six (ᏑᏓᎵ). This same symbol Ꮡ represents suh as in suhdi, meaning 'fishhook' (ᏑᏗ). Therefore, there is no differentiation among the symbols used for syllables ending in a single vowel versus that vowel plus "h." When consonants other than s, h, or glottal stop arise with other consonants in clusters, the appropriate consonant plus a "dummy vowel" is used. This dummy vowel is not pronounced and is either chosen arbitrarily or for etymological reasons (reflecting an underlying etymological vowel). For example, ᏧᎾᏍᏗ (tsu-na-s-di) represents the word ju:nsdi, meaning 'small.' Ns in this case is the consonant cluster that requires the following dummy vowel, a. Ns is written as ᎾᏍ /nas/. The vowel is included in the transliteration, but is not pronounced in the word (ju:nsdi). (The transliterated ts represents the affricate j).[5][page needed] As with some other writing systems (like Arabic), adult speakers can distinguish words by context.

Transliteration issues

Some Cherokee words pose a problem for transliteration software because they contain adjacent pairs of single letter symbols that (without special provisions) would be combined when doing the back conversion from Latin script to Cherokee. Here are a few examples:

- ᎢᏣᎵᏍᎠᏁᏗ = itsalisanedi = i-tsa-li-s-a-ne-di

- ᎤᎵᎩᏳᏍᎠᏅᏁ = uligiyusanvne = u-li-gi-yu-s-a-nv-ne

- ᎤᏂᏰᏍᎢᏱ = uniyesiyi = u-ni-ye-s-i-yi

- ᎾᏍᎢᏯ = nasiya = na-s-i-ya

For these examples, the back conversion is likely to join s-a as sa or s-i as si.

Other Cherokee words contain character pairs that entail overlapping transliteration sequences. Examples:

- ᏀᎾ transliterates as nahna, yet so does ᎾᎿ. The former is nah-na, the latter is na-hna.

If the Latin script is parsed from left to right, longest match first, then without special provisions, the back conversion would be wrong for the latter. There are several similar examples involving these character combinations: naha nahe nahi naho nahu nahv.

A further problem encountered in transliterating Cherokee is that there are some pairs of different Cherokee words that transliterate to the same word in the Latin script. Here are some examples:

- ᎠᏍᎡᏃ and ᎠᏎᏃ both transliterate to aseno

- ᎨᏍᎥᎢ and ᎨᏒᎢ both transliterate to gesvi

Without special provision, a round trip conversion changes ᎠᏍᎡᏃ to ᎠᏎᏃ and changes ᎨᏍᎥᎢ to ᎨᏒᎢ.[b]

Character orders

- The usual alphabetical order[c] for Cherokee runs across the rows of the syllabary chart from left-to-right, top-to-bottom: Ꭰ (a), Ꭱ (e),Ꭲ (i), Ꭳ (o), Ꭴ (u), Ꭵ (v), Ꭶ (ga), Ꭷ (ka), Ꭸ (ge), Ꭹ (gi), Ꭺ (go), Ꭻ (gu), Ꭼ (gv), Ꭽ (ha), Ꭾ (he), Ꭿ (hi), Ꮀ (ho), Ꮁ (hu), Ꮂ (hv), Ꮃ (la), Ꮄ (le), Ꮅ (li), Ꮆ (lo), Ꮇ (lu), Ꮈ (lv), Ꮉ (ma), Ꮊ (me), Ꮋ (mi), Ꮌ (mo), Ꮍ (mu), Ꮎ (na), Ꮏ (hna), Ꮐ (hah), Ꮑ (ne), Ꮒ (ni), Ꮓ (no), Ꮔ (nu), Ꮕ (nv), Ꮖ (qua), Ꮗ (que), Ꮘ (qui), Ꮙ (quo), Ꮚ (quu), Ꮛ (quv), Ꮜ (sa), Ꮝ (s), Ꮞ (se), Ꮟ (si), Ꮠ (so), Ꮡ (su), Ꮢ (sv), Ꮣ (da), Ꮤ (ta), Ꮥ (de), Ꮦ (te), Ꮧ (di), Ꮨ (ti), Ꮩ (do), Ꮪ (du), Ꮫ (dv), Ꮬ (dla), Ꮭ (tla), Ꮮ (tle), Ꮯ (tli), Ꮰ (tlo), Ꮱ (tlu), Ꮲ (tlv), Ꮳ (tsa), Ꮴ (tse), Ꮵ (tsi), Ꮶ (tso), Ꮷ (tsu), Ꮸ (tsv), Ꮹ (wa), Ꮺ (we), Ꮻ (wi), Ꮼ (wo), Ꮽ (wu), Ꮾ (wv), Ꮿ (ya), Ᏸ (ye), Ᏹ (yi), Ᏺ (yo), Ᏻ (yu), Ᏼ (yv).

- Cherokee has also been alphabetized based on the six columns of the syllabary chart from top-to-bottom, left-to-right: Ꭰ (a), Ꭶ (ga), Ꭷ (ka), Ꭽ (ha), Ꮃ (la), Ꮉ (ma), Ꮎ (na), Ꮏ (hna), Ꮐ (hah), Ꮖ (qua), Ꮝ (s), Ꮜ (sa), Ꮣ (da), Ꮤ (ta), Ꮬ (dla), Ꮭ (tla), Ꮳ (tsa), Ꮹ (wa), Ꮿ (ya), Ꭱ (e), Ꭸ (ge), Ꭾ (he), Ꮄ (le), Ꮊ (me), Ꮑ (ne), Ꮗ (que), Ꮞ (se), Ꮥ (de), Ꮦ (te), Ꮮ (tle), Ꮴ (tse), Ꮺ (we), Ᏸ (ye), Ꭲ (i), Ꭹ (gi), Ꭿ (hi), Ꮅ (li), Ꮋ (mi), Ꮒ (ni), Ꮘ (qui), Ꮟ (si), Ꮧ (di), Ꮨ (ti), Ꮯ (tli), Ꮵ (tsi), Ꮻ (wi), Ᏹ (yi), Ꭳ (o), Ꭺ (go), Ꮀ (ho), Ꮆ (lo), Ꮌ (mo), Ꮓ (no), Ꮙ (quo), Ꮠ (so), Ꮩ (do), Ꮰ (tlo), Ꮶ (tso), Ꮼ (wo), Ᏺ (yo), Ꭴ (u), Ꭻ (gu), Ꮁ (hu), Ꮇ (lu), Ꮍ (mu), Ꮔ (nu), Ꮚ (quu), Ꮡ (su), Ꮪ (du), Ꮱ (tlu), Ꮷ (tsu), Ꮽ (wu), Ᏻ (yu), Ꭵ (v), Ꭼ (gv), Ꮂ (hv), Ꮈ (lv), Ꮕ (nv), Ꮛ (quv), Ꮢ (sv), Ꮫ (dv), Ꮲ (tlv), Ꮸ (tsv), Ꮾ (wv), Ᏼ (yv).

- Sequoyah used a completely different alphabetical order: Ꭱ (e), Ꭰ (a), Ꮃ (la), Ꮵ (tsi), Ꮐ (hah), Ꮽ (wu), Ꮺ (we), Ꮅ (li), Ꮑ (ne), Ꮌ (mo), Ꭹ (gi), Ᏹ (yi), Ꮟ (si), Ꮲ (tlv), Ꭳ (o), Ꮇ (lu), Ꮄ (le), Ꭽ (ha), Ꮼ (wo), Ꮰ (tlo), Ꮤ (ta), Ᏼ (yv), Ꮈ (lv), Ꭿ (hi), Ꮝ (s), Ᏺ (yo), Ꮁ (hu), Ꭺ (go), Ꮷ (tsu), Ꮍ (mu), Ꮞ (se), Ꮠ (so), Ꮯ (tli), Ꮘ (qui), Ꮗ (que), Ꮜ (sa), Ꮖ (qua), Ꮓ (no), Ꭷ (ka), Ꮸ (tsv), Ꮢ (sv), Ꮒ (ni), Ꭶ (ga), Ꮩ (do), Ꭸ (ge), Ꮣ (da), Ꭼ (gv), Ꮻ (wi), Ꭲ (i), Ꭴ (u), Ᏸ (ye), Ꮂ (hv), Ꮫ (dv), Ꭻ (gu), Ꮶ (tso), Ꮙ (quo), Ꮔ (nu), Ꮎ (na), Ꮆ (lo), Ᏻ (yu), Ꮴ (tse), Ꮧ (di), Ꮾ (wv), Ꮪ(du), Ꮥ (de), Ꮳ (tsa), Ꭵ (v), Ꮕ (nv), Ꮦ (te), Ꮉ (ma), Ꮡ (su), Ꮱ (tlu), Ꭾ (he), Ꮀ (ho), Ꮋ (mi), Ꮭ (tla), Ꮿ (ya), Ꮹ (wa), Ꮨ (ti), Ꮮ (tle), Ꮏ (hna), Ꮚ (quu), Ꮬ (dla), Ꮊ (me), Ꮛ (quv).

Numerals

Cherokee uses Arabic numerals (0–9). The Cherokee council voted not to adopt Sequoyah's numbering system.[6] Sequoyah created individual symbols for 1–20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100 as well as a symbol for three zeros for numbers in the thousands and a symbol for six zeros for numbers in the millions. These last two symbols representing ,000 and ,000,000 are made up of two separate symbols each. Both of these have a symbol in common, this common symbol could be used as a zero in itself.

Early history

Around 1809, impressed by the "talking leaves" of European written languages, Sequoyah began work to create a writing system for the Cherokee language. After attempting to create a character for each word, Sequoyah realized this would be too difficult and eventually created characters to represent syllables. Sequoyah took some ideas from his copy of the Bible, which he studied for characters to use in print, noticing the simplicity of the Roman letters and adopting them to make the writing of his syllabary easier. He could not actually read any of the letters in the book (as can be seen in certain characters in his syllabary, which look like Ws or 4s for example), so it is especially impressive that he came up with such a well-developed system. He worked on the syllabary for twelve years before completion, and dropped or modified most of the characters he originally created. The rapid dissemination of the syllabary is notable, and by 1824, most Cherokees could read and write in their newly developed orthography.[3][page needed]

In 1828, the order of the symbols in a chart and the very shapes of the symbols were modified by Cherokee author and editor Elias Boudinot to adapt the syllabary to printing presses.[7] The 86th character was dropped entirely.[8][page needed] However, the new writing system was a key factor in enabling the Cherokee to maintain their social boundaries and ethnic identities. Since 1828, very few changes have been made to the syllabary.[3][page needed]

Later developments

The syllabary achieved almost instantaneous popularity, and was adopted by the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, later Cherokee Advocate, in 1828, followed by the Cherokee Messenger, a bilingual paper printed in syllabary in Indian Territory in the mid-19th century.[9] It has been used since it was formed to write letters, keep diaries, and record medical formulas.[5] The syllabary is still used today to transcribe recipes, religious lore, folktales, etc. In the 1960s, the Cherokee Phoenix Press published literature in the Cherokee syllabary, including the Cherokee Singing Book.[10]

According to evidence as of 1980, the Cherokee language is still spoken both formally and informally by around 10,000 Western Cherokees. The language remains strong.[11] A Cherokee syllabary typewriter ball was developed in the 1980s. Computer fonts greatly expanded Cherokee writers' ability to publish in Cherokee.

An increasing corpus of children's literature is printed in Cherokee syllabary today to meet the needs of Cherokee students in the Cherokee language immersion schools in Oklahoma and North Carolina. In 2010, a Cherokee keyboard cover was developed by Roy Boney, Jr. and Joseph Erb, facilitating more rapid typing in Cherokee and now used by students in the Cherokee Nation Immersion School, where all coursework is written in syllabary.[7] The syllabary is finding increasingly diverse usage today, from books, newspapers, and websites to the street signs of Tahlequah, Oklahoma and Cherokee, North Carolina. In August 2010, the Oconaluftee Institute for Cultural Arts in Cherokee, North Carolina acquired a letterpress and had the Cherokee syllabary recast to begin printing one-of-a-kind fine art books and prints in syllabary.[12]

Possible influence on Liberian Vai syllabary

In recent years evidence has emerged suggesting that the Cherokee syllabary provided a model for the design of the Vai syllabary in Liberia, Africa. The Vai syllabary emerged about 1832/33. The link appears to have been Cherokee who emigrated to Liberia after the invention of the Cherokee syllabary (which in its early years spread rapidly among the Cherokee) but before the invention of the Vai syllabary. One such man, Cherokee Austin Curtis, married into a prominent Vai family and became an important Vai chief himself. It is perhaps not coincidence that the "inscription on a house" that drew the world's attention to the existence of the Vai script was in fact on the home of Curtis, a Cherokee.[13] There also appears to be a connection between an early form of written Bassa and the earlier Cherokee syllabary.

Classes

Cherokee languages classes typically begin with a transliteration of Cherokee into Roman letters, only later incorporating the syllabary. The Cherokee languages classes offered through Haskell Indian Nations University, Northeastern State University,[7] the University of Oklahoma, the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma, Western Carolina University, and the elementary school immersion classes offered by the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Immersion School[14] all teach the syllabary. The Oconaluftee Institute for Cultural Arts incorporates the syllabary in the printmaking classes.[12]

Unicode

Cherokee was added to the Unicode Standard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0.

Block

The Unicode block for Cherokee is U+13A0 ... U+13FF:[d]

| Cherokee[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+13Ax | Ꭰ | Ꭱ | Ꭲ | Ꭳ | Ꭴ | Ꭵ | Ꭶ | Ꭷ | Ꭸ | Ꭹ | Ꭺ | Ꭻ | Ꭼ | Ꭽ | Ꭾ | Ꭿ |

| U+13Bx | Ꮀ | Ꮁ | Ꮂ | Ꮃ | Ꮄ | Ꮅ | Ꮆ | Ꮇ | Ꮈ | Ꮉ | Ꮊ | Ꮋ | Ꮌ | Ꮍ | Ꮎ | Ꮏ |

| U+13Cx | Ꮐ | Ꮑ | Ꮒ | Ꮓ | Ꮔ | Ꮕ | Ꮖ | Ꮗ | Ꮘ | Ꮙ | Ꮚ | Ꮛ | Ꮜ | Ꮝ | Ꮞ | Ꮟ |

| U+13Dx | Ꮠ | Ꮡ | Ꮢ | Ꮣ | Ꮤ | Ꮥ | Ꮦ | Ꮧ | Ꮨ | Ꮩ | Ꮪ | Ꮫ | Ꮬ | Ꮭ | Ꮮ | Ꮯ |

| U+13Ex | Ꮰ | Ꮱ | Ꮲ | Ꮳ | Ꮴ | Ꮵ | Ꮶ | Ꮷ | Ꮸ | Ꮹ | Ꮺ | Ꮻ | Ꮼ | Ꮽ | Ꮾ | Ꮿ |

| U+13Fx | Ᏸ | Ᏹ | Ᏺ | Ᏻ | Ᏼ | Ᏽ | ᏸ | ᏹ | ᏺ | ᏻ | ᏼ | ᏽ | ||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Fonts

A single Cherokee Unicode font is supplied with Mac OS X, version 10.3 (Panther) and later and Windows Vista. Cherokee is also supported by free fonts found at languagegeek.com and Touzet's atypical.net, and the shareware fonts Code2000 and Everson Mono.

- "Download", Font, Language geek.

- "Mono", Everson, Ever type.

- Cherokee (font), Atypical.

- Digohweli Cherokee font – use this to display the new-form do (V-like).

- FreeFont, GNU serif and sans faces in four styles; monospace.

Notes

- ^ There was a difference between the old-form DO (Λ-like) and a new-form DO (V-like). The standard Digohweli font displays the new-form. Old Do Digohweli and Code2000 fonts both display the old-form[4]

- ^ This has been confirmed using the online transliteration service.

- ^ This is the same order as in the Unicode block.

- ^ The PDF version shows the new-form of the letter do.

References

- ^ a b Sturtevant, Fogelson & 2004 337. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTESturtevantFogelson2004337" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ U13A0 (PDF) (chart), Unicode.

- ^ a b c d Walker & Sarbaugh 1993.

- ^ "Cherokee", Font download.

- ^ a b Scancarelli 2005.

- ^ "Numerals", Cherokee, Inter tribal.

- ^ a b c "Cherokee Nation creates syllabary keypad." Indian Country Today. 17 Mar 2010 (retrieved 23 Aug 2010)

- ^ Kilpatrick & Kilpatick 1968.

- ^ Sturtevant & Fogelson 2004, p. 362.

- ^ Sturtevant & Fogelson 2004, p. 750.

- ^ Foley 1980.

- ^ a b "Letterpress arrives at OICA" Southwestern Community College (retrieved 21 Nov 2010)

- ^ Tuchscherer 2002.

- ^ "Cherokee Language Revitalization Project." Western Carolina University. (retrieved 23 Aug 2010)

Bibliography

- Bender, Margaret. 2002. Signs of Cherokee Culture: Sequoyah's Syllabary in Eastern Cherokee Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bender, Margaret. 2008. Indexicality, voice, and context in the distribution of Cherokee scripts. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 192:91–104.

- Daniels, Peter T (1996), The World's Writing Systems, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 587–92.

- Foley, Lawrence (1980), Phonological Variation in Western Cherokee, New York: Garland Publishing.

- Kilpatrick, Jack F; Kilpatrick, Anna Gritts, New Echota Letters, Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

- Scancarelli, Janine (2005), "Cherokee", in Hardy, Heather K; Scancarelli, Janine (eds.), Native Languages of the Southeastern United States, Bloomington: Nebraska Press, pp. 351–84.

- Tuchscherer, Konrad; Hair, PEH (2002), "Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script", History in Africa (29): 427–86.

- Sturtevant, William C (general); Fogelson (volume), Raymond D, eds. (2004), Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast, vol. 14, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Walker, Willard; Sarbaugh, James (1993), "The Early History of the Cherokee Syllabary", Ethnohistory, 40 (1): 70–94.

Further reading

- Cowen, Agnes (1981), Cherokee syllabary primer, Park Hill, OK: Cross-Cultural Education Center, ASIN B00341DPR2.

External links

- The Cherokee Syllabary: Writing the People's Perseverance (online media tool), Michigan State University Alumni Association.

- "Cherokee", (Writing), Omniglot http://www.omniglot.com/writing/cherokee.htm

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help). - "Sequoyah", Cherokee (online conversion tool), Transliteration.