Statin

| Statin | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

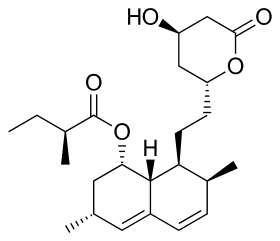

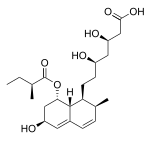

Lovastatin, a compound isolated from Aspergillus terreus, was the first statin to be marketed. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | High cholesterol |

| ATC code | C10AA |

| Biological target | HMG-CoA reductase |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D019161 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Statins (or HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) are a class of drugs used to lower cholesterol levels by inhibiting the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, which plays a central role in the production of cholesterol in the liver, which produces about 70 percent of total cholesterol in the body. High cholesterol levels have been associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD).[1] Statins have been found to prevent cardiovascular disease in those who are at high risk. The evidence is strong that statins are effective for treating CVD in the early stages of a disease (secondary prevention). The evidence is weaker that statins are effective for those with elevated cholesterol levels but without CVD (primary prevention).[2][3][4] Side effects of statins include muscle pain, increased risk of diabetes and abnormalities in liver enzyme tests.[5] Additionally, they have rare but severe adverse effects, particularly muscle damage.[6] Some doctors believe that statins are over-prescribed.

As of 2010, a number of statins are on the market: atorvastatin (Lipitor), fluvastatin (Lescol), lovastatin (Mevacor, Altocor), pitavastatin (Livalo), pravastatin (Pravachol), rosuvastatin (Crestor) and simvastatin (Zocor).[7] Several combination preparations of a statin and another agent, such as ezetimibe/simvastatin, are also available. The best-selling statin is atorvastatin which by 2003 became the best-selling pharmaceutical in history.[8] The manufacturer Pfizer reporting sales of US$12.4 billion in 2008.[9]

Medical uses

Clinical practice guidelines generally recommend people to try "lifestyle modification", including a cholesterol-lowering diet and physical exercise, before statin use; statins or other pharmacologic agents may be recommended for those who do not meet their lipid-lowering goals through diet and lifestyle changes.[10][11]

Primary prevention

Most evidence suggests that statins are effective in preventing heart disease in those with high cholesterol, but no history of heart disease. A 2013 Cochrane review found a decrease in risk of death and other poor outcomes without any evidence of harm.[12] A 2011 review reached similar conclusions.[13] And a 2012 review found benefits in both women and men.[14] A 2010 review concluded that treating people with no history of cardiovascular disease reduces cardiovascular events in men but not women, and provides no mortality benefit in either sex.[15] Two other meta analyses published that year, one of which used data obtained exclusively from women, found no mortality benefit in primary prevention.[16][17]

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends statin treatment for adults with an estimated 10 year risk of developing cardiovascular disease that is greater than 20%.[18] In 2014, NICE issued draft guidance lowering the threshold to a 10 year risk of 10% or more.[19] Guidelines by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association recommend statin treatment for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with LDL cholesterol > 190 mg/dL.[20] The European Society of Cardiology and the European Atherosclerosis Society recommend the use of statins for primary prevention, depending on baseline estimated cardiovascular score and LDL thresholds.[21]

Secondary prevention

Statins are effective in decreasing mortality in people with pre-existing CVD. They are also currently advocated for use in patients at high risk of developing heart disease.[2] On average, statins can lower LDL cholesterol by 1.8 mmol/l (70 mg/dl), which translates into an estimated 60% decrease in the number of cardiac events (heart attack, sudden cardiac death) and a 17% reduced risk of stroke after long-term treatment.[22] They have less effect than the fibrates or niacin in reducing triglycerides and raising HDL-cholesterol ("good cholesterol").

Comparative effectiveness

While no direct comparison exists, all statins appear effective regardless of potency or degree of cholesterol reduction.[23] There do appear to be some differences between them, with simvastatin and pravastatin appearing superior in terms of side-effects.[5]

A comparison of atorvastatin, pravastatin and simvastatin, based on their effectiveness against placebos, found, at commonly prescribed doses, no statistically significant differences among agents in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.[24]

Children

In children statins are effective at reducing cholesterol levels in those with familial hypercholesterolemia.[25] Their long term safety is; however, unclear.[25][26] Some recommend that if lifestyle changes are not enough statins should be started at 8 years old.[27]

Adverse effects

| Choosing a statin for people with special considerations[28] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Commonly recommended statins | explanation | |

| kidney transplantation recipients taking ciclosporin | Pravastatin or Fluvastatin | Drug interactions are possible, but studies have not shown that these statins increase exposure to ciclosporin.[29] | |

| HIV-positive people taking protease inhibitors | Atorvastatin, Pravastatin or Fluvastatin | Significant negative interactions are more likely with other choices[30] | |

| persons taking gemfibrozil, a non-statin cholesterol-lowering drug | Atorvastatin | Combining gemfibrozil and a statin increases risk of Rhabdomyolysis and subsequently renal failure[31][32] | |

| persons taking the anticoagulant warfarin | any statin | The statin use may require that the warfarin dose be changed, as some statins increase the effect of warfarin.[33] | |

The most common adverse side effects are raised liver enzymes and muscle problems. In randomized clinical trials, reported adverse effects are low; but they are "higher in studies of real world use", and more varied.[34] In randomized trials, statins increased the risk of an adverse effect by 39% compared to placebo (odds ratios 1.4); two-thirds of these were myalgia or raised liver enzymes, with serious adverse effects similar to placebo.[35] However, reliance on clinical trials can be misleading indications of real-world adverse effects – for example, the statin cerivastatin was withdrawn from the market in 2001 due to cases of rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown), although rhabdomyolysis was not found in a meta-analysis of published cerivastatin clinical trials.[34] A 2014 systematic review on the side effects of statins found a 0.5% increase in diabetes.[36] Other possible adverse effects include cognitive loss, neuropathy, pancreatic and hepatic dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction.[34]

Some people on statin therapy report myalgias,[37] muscle cramps,[37] or, less frequently, gastrointestinal or other symptoms. Liver enzyme derangements, typically in about 0.5%,[citation needed] are also seen at similar rates with placebo use and repeated enzyme testing, and generally return to normal either without discontinuance over time or after briefly discontinuing the drug. Multiple other side effects occur rarely; typically also at similar rates with only placebo in the large statin safety/efficacy trials. Two randomized clinical trials found cognitive issues, while two did not; recurrence upon reintroduction suggests these are causally related to statins in some individuals.[38] A Danish case-control study published in 2002 suggested a relationship between long-term statin use and increased risk of nerve damage or polyneuropathy,[39] but suggested this side effect is "rare, but it does occur";[40] other researchers have pointed to studies of the effectiveness of statins in trials involving 50,000 people which have not shown nerve damage as a significant side effect.[41]

Muscles

Problems with muscles occur in 10-15% of people who take statins.[6] Rare reactions include myositis and myopathy, with the potential for rhabdomyolysis (a significant breakdown of skeletal muscle) possibly leading to acute renal failure. Coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone) levels are decreased in statin use;[42] CoQ10 supplements are sometimes used to treat statin-associated myopathy, though there was not enough evidence of their effectiveness despite their ability to raise the circulating levels of CoQ10 in blood plasma as of 2007[update].[43] The gene SLCO1B1 (Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1) codes for an organic anion-transporting polypeptide that is involved in the regulation of the absorption of statins. A common variation in this gene was found in 2008 to significantly increase the risk of myopathy.[44]

Graham et al. (2004) reviewed records of over 250,000 patients treated from 1998 to 2001 with the statin drugs atorvastatin, cerivastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin.[45] The incidence of rhabdomyolyis was 0.44 per 10,000 patients treated with statins other than cerivastatin. However, the risk was over 10-fold greater if cerivastatin was used, or if the standard statins (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, or simvastatin) were combined with fibrate (fenofibrate or gemfibrozil) treatment. Cerivastatin was withdrawn by its manufacturer in 2001.

All commonly used statins show somewhat similar results, but the newer statins, characterized by longer pharmacological half-lives and more cellular specificity, have had a better ratio of efficacy to lower adverse effect rates.[citation needed] Some researchers have suggested hydrophilic statins, such as fluvastatin, rosuvastatin, and pravastatin, are less toxic than lipophilic statins, such as atorvastatin, lovastatin, and simvastatin, but other studies have not found a connection;[46] the risk of myopathy was suggested to be lowest with pravastatin and fluvastatin, probably because they are more hydrophilic and as a result have less muscle penetration.[citation needed] Lovastatin induces the expression of gene atrogin-1, which is believed to be responsible in promoting muscle fiber damage.[46]

Diabetes

Statins may increase the risk of diabetes by 9%,[47] with higher doses appearing to have a larger effect.[48]

Cancer

Statins do not appear to be associated with cancer.[49][50] Although there have been concerns that they might increase risk,[51] several meta-analyses have found no relationship.[52][53]

They may reduce the risk of esophageal cancer,[54] colorectal cancer,[55] gastric cancer,[56][57] hepatocellular carcinoma,[58] and possibly prostate cancer.[59][60] They appear to have no effect on the risk of lung cancer,[61] kidney cancer,[62] breast cancer,[63] pancreatic cancer,[64] or bladder cancer.[65]

Drug interactions

Combining any statin with a fibrate or niacin, another category of lipid-lowering drugs, increases the risks for rhabdomyolysis to almost 6.0 per 10,000 person-years.[45] Most physicians have now abandoned routine monitoring of liver enzymes and creatine kinase, although they still consider this prudent in those on high-dose statins or in those on statin/fibrate combinations, and mandatory in the case of muscle cramps or of deterioration in renal function.

Consumption of grapefruit or grapefruit juice inhibits the metabolism of certain statins. Bitter oranges may have a similar effect.[66] Furanocoumarins in grapefruit juice (i.e. bergamottin and dihydroxybergamottin) inhibit the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A4, which is involved in the metabolism of most statins (however, it is a major inhibitor of only lovastatin, simvastatin, and to a lesser degree, atorvastatin) and some other medications[67] (flavonoids (i.e. naringin) were thought to be responsible). This increases the levels of the statin, increasing the risk of dose-related adverse effects (including myopathy/rhabdomyolysis). The absolute prohibition of grapefruit juice consumption for users of some statins is controversial.[68]

The FDA notified healthcare professionals of updates to the prescribing information concerning interactions between protease inhibitors and certain statin drugs. Protease inhibitors and statins taken together may raise the blood levels of statins and increase the risk for muscle injury (myopathy). The most serious form of myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, can damage the kidneys and lead to kidney failure, which can be fatal.[69]

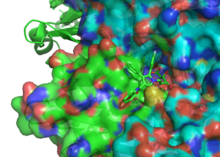

Mechanism of action

Statins act by competitively inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, the first committed enzyme of the HMG-CoA reductase pathway. Because statins are similar to HMG-CoA on a molecular level, they take the place of HMG-CoA in the enzyme and reduce the rate by which it is able to produce mevalonate, the next molecule in the cascade that eventually produces cholesterol, as well as a number of other compounds. This ultimately reduces cholesterol via several mechanisms. A variety of statins are produced by Penecillium and Aspergillus fungi as secondary metabolites. These natural statins probably function to inhibit HMG-CoA reductase enzymes in bacteria and fungi that compete with the producer.[71]

Inhibiting cholesterol synthesis

By inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, statins block the pathway for synthesizing cholesterol in the liver. This is significant because most circulating cholesterol comes from internal manufacture rather than the diet. When the liver can no longer produce cholesterol, levels of cholesterol in the blood will fall. Cholesterol synthesis appears to occur mostly at night,[72] so statins with short half-lives are usually taken at night to maximize their effect. Studies have shown greater LDL and total cholesterol reductions in the short-acting simvastatin taken at night rather than the morning,[73][74] but have shown no difference in the long-acting atorvastatin.[75]

Increasing LDL uptake

In rabbits, hepatocytes (liver cells) sense the reduced levels of liver cholesterol and seek to compensate by synthesizing LDL receptors to draw cholesterol out of the circulation.[76] This is accomplished via protease enzymes that cleave a protein called "membrane-bound sterol regulatory element binding protein", which migrates to the nucleus and causes increased production of various other proteins and enzymes, including the LDL receptor. The LDL receptor then relocates to the liver cell membrane and binds to passing LDL and VLDL particles (the "bad cholesterol" linked to disease). LDL and VLDL are drawn out of circulation into the liver, where the cholesterol is reprocessed into bile salts. These are excreted, and subsequently recycled mostly by an internal bile salt circulation.

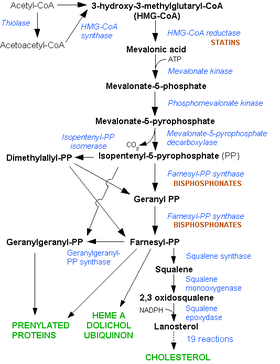

Decreasing of specific protein prenylation

Statins, by inhibiting the HMG CoA reductase pathway, simultaneously inhibit the production of both cholesterol and specific prenylated proteins (see diagram). A 2012 study found that statin treatment increases lifespan and improves cardiac health in Drosophila by decreasing specific protein prenylation. The study concluded, "These data are the most direct evidence to date that decreased protein prenylation can increase cardiac health and lifespan in any metazoan [animal] species, and may explain the pleiotropic (non-cholesterol related) health effects of statins."[77] This inhibitory effect on protein prenylation may be involved, at least partially, in the improvement of endothelial function and other pleiotropic cardiovascular benefits of statins,[78][79] and may also account for certain of the benefits seen in cancer reduction with statins.[80]

Other effects

Statins exhibit action beyond lipid-lowering activity in the prevention of atherosclerosis. The ASTEROID trial showed direct ultrasound evidence of atheroma regression during statin therapy.[81] Researchers hypothesize that statins prevent cardiovascular disease via four proposed mechanisms (all subjects of a large body of biomedical research):[82]

- Improve endothelial function

- Modulate inflammatory responses

- Maintain plaque stability

- Prevent thrombus formation

There is controversy that statins may benefit those without high cholesterol. In 2008, the JUPITER study showed benefit in those who had no history of high cholesterol or heart disease, but only elevated C-reactive protein levels.[83] An independent review did not consider the results of the trial to support these conclusions and raised concern of bias due to funding from the manufacturer.[84]

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "Statin_Pathway_WP430".

Available forms

The statins are divided into two groups: fermentation-derived and synthetic. They include, along with brand names, which may vary between countries:

| Statin | Image | Brand name | Derivation | Metabolism[85] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atorvastatin |  |

Lipitor, Torvast | Synthetic | CYP3A4 |

| Cerivastatin |  |

Lipobay, Baycol. (Withdrawn from the market in August, 2001 due to risk of serious Rhabdomyolysis) | Synthetic | various CYP3A isoforms [86] |

| Fluvastatin |  |

Lescol, Lescol XL | Synthetic | CYP2C9 |

| Lovastatin |  |

Mevacor, Altocor, Altoprev | Fermentation-derived. Naturally occurring compound. Found in oyster mushrooms and red yeast rice. | CYP3A4 |

| Mevastatin |  |

Compactin | Naturally occurring compound. Found in red yeast rice. | CYP3A4 |

| Pitavastatin |  |

Livalo, Pitava | Synthetic | |

| Pravastatin |  |

Pravachol, Selektine, Lipostat | Fermentation-derived. (A fermentation product of bacterium Nocardia autotrophica). | Non CYP[87] |

| Rosuvastatin |  |

Crestor | Synthetic | CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 |

| Simvastatin |  |

Zocor, Lipex | Fermentation-derived. (Simvastatin is a synthetic derivate of a fermentation product ofAspergillus terreus.) | CYP3A4 |

| Simvastatin+Ezetimibe | Vytorin | Combination therapy | ||

| Lovastatin+Niacin extended-release | Advicor | Combination therapy | ||

| Atorvastatin+Amlodipine Besylate | Caduet | Combination therapy – Cholesterol+Blood Pressure | ||

| Simvastatin+Niacin extended-release | Simcor | Combination therapy |

LDL-lowering potency varies between agents. Cerivastatin is the most potent, (withdrawn from the market in August, 2001 due to risk of serious rhabdomyolysis) followed by (in order of decreasing potency), rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and fluvastatin.[88] The relative potency of pitavastatin has not yet been fully established.

Some types of statins are naturally occurring, and can be found in such foods as oyster mushrooms and red yeast rice. Randomized controlled trials have found these foodstuffs to reduce circulating cholesterol, but the quality of the trials has been judged to be low.[89] Most of the block-buster branded statins will be generic by 2012, including atorvastatin, the largest-selling branded drug.

| Statin equivalent dosages | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % LDL reduction (approx.) | Atorvastatin | Fluvastatin | Lovastatin | Pravastatin | Rosuvastatin | Simvastatin |

| 10–20% | – | 20 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg | – | 5 mg |

| 20–30% | – | 40 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | – | 10 mg |

| 30–40% | 10 mg | 80 mg | 40 mg | 40 mg | 5 mg | 20 mg |

| 40–45% | 20 mg | – | 80 mg | 80 mg | 5–10 mg | 40 mg |

| 46–50% | 40 mg | – | – | – | 10–20 mg | 80 mg* |

| 50–55% | 80 mg | – | – | – | 20 mg | – |

| 56–60% | – | – | – | – | 40 mg | – |

| * 80-mg dose no longer recommended due to increased risk of rhabdomyolysis | ||||||

| Starting dose | ||||||

| Starting dose | 10–20 mg | 20 mg | 10–20 mg | 40 mg | 10 mg; 5 mg if hypothyroid, >65 yo, Asian | 20 mg |

| If higher LDL reduction goal | 40 mg if >45% | 40 mg if >25% | 20 mg if >20% | -- | 20 mg if LDL >190 mg/dL (4.87 mmol/L) | 40 mg if >45% |

| Optimal timing | Anytime | Evening | With evening meals | Anytime | Anytime | Evening |

History

In 1971, Akira Endo, a Japanese biochemist working for the pharmaceutical company Sankyo, began the search for a cholesterol-lowering drug. Research had already shown cholesterol is mostly manufactured by the body in the liver, using the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase.[8] Endo and his team reasoned that certain microorganisms may produce inhibitors of the enzyme to defend themselves against other organisms, as mevalonate is a precursor of many substances required by organisms for the maintenance of their cell walls (ergosterol) or cytoskeleton (isoprenoids).[71] The first agent they identified was mevastatin (ML-236B), a molecule produced by the fungus Penicillium citrinum.

A British group isolated the same compound from Penicillium brevicompactum, named it compactin, and published their report in 1976.[90] The British group mentions antifungal properties, with no mention of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition.

Mevastatin was never marketed, because of its adverse effects of tumors, muscle deterioration, and sometimes death in laboratory dogs. P. Roy Vagelos, chief scientist and later CEO of Merck & Co, was interested, and made several trips to Japan starting in 1975. By 1978, Merck had isolated lovastatin (mevinolin, MK803) from the fungus Aspergillus terreus, first marketed in 1987 as Mevacor.[8]

A link between cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, known as the lipid hypothesis, had already been suggested. Cholesterol is the main constituent of atheroma, the fatty lumps in the wall of arteries that occur in atherosclerosis and, when ruptured, cause the vast majority of heart attacks. Treatment consisted mainly of dietary measures, such as a low-fat diet, and poorly tolerated medicines, such as clofibrate, cholestyramine, and nicotinic acid. Cholesterol researcher Daniel Steinberg writes that while the Coronary Primary Prevention Trial of 1984 demonstrated cholesterol lowering could significantly reduce the risk of heart attacks and angina, physicians, including cardiologists, remained largely unconvinced.[91]

To market statins effectively, Merck had to convince the public of the dangers of high cholesterol, and doctors that statins were safe and would extend lives. As a result of public campaigns, people in the United States became familiar with their cholesterol numbers and the difference between "good" and "bad" cholesterol, and rival pharmaceutical companies began producing their own statins, such as pravastatin (Pravachol), manufactured by Sankyo and Bristol-Myers Squibb. In April 1994, the results of a Merck-sponsored study, the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study, were announced. Researchers tested simvastatin, later sold by Merck as Zocor, on 4,444 patients with high cholesterol and heart disease. After five years, the study concluded the patients saw a 35% reduction in their cholesterol, and their chances of dying of a heart attack were reduced by 42%.[8][92] In 1995, Zocor and Mevacor both made Merck over US$1 billion.[8] Endo was awarded the 2006 Japan Prize, and the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award in 2008. For his "pioneering research into a new class of molecules" for "lowering cholesterol,"[93] Endo was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Virginia in 2012. Michael C. Brown and Joseph Goldstein, who won the Nobel Prize for related work on cholesterol, said of Endo: "The millions of people whose lives will be extended through statin therapy owe it all to Akira Endo."[94]

Society and Culture

Some[quantify] scientists believe the statins are overused. Their use has expanded into areas where they provide lesser benefit, and lesser evidence of benefit. The lower the risk of cardiovascular events, the lower the ratio is of benefits to costs. The US market for statins nearly tripled when the National Cholesterol Education Program revised its guidelines to recommend statins as primary prevention. Although the panel cited randomized trials to support statin therapy for primary prevention of occlusive cardiovascular disease, a report in Lancet notes, "not one of the studies provides such evidence." [95]

A group of scientists, The International Network of Cholesterol Skeptics, question the lipid hypothesis and argue that elevated cholesterol has not been adequately shown to cause heart disease. These organizations maintain that statins are not as beneficial or safe as suggested.[96] The beneficial effects of statins are suggested to be due to their working as vitamin D analogues.[97]

Research

Research continues into other areas where specific statins also appear to have a favorable effect, including dementia,[98] lung cancer,[99] nuclear cataracts,[100] hypertension,[101] and prostate cancer.[102]

Pharmacogenomics

A 2004 study showed patients with one of two common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (small genetic variations) in the HMG-CoA reductase gene were less responsive to statins.[103] A 2008 study showed carriers of the KIF6 genetic mutation were more responsive to statin treatment.[104]

Myopathy Adverse Drug Event

Likewise, a 2008 study demonstrated a link between an increased risk of myopathy at higher doses of statins (40–80 mg) and a SNP in SLCO1B1, a gene encoding for the organic anion transporter peptide OATP1B1.[44] Genotyping or genome sequencing can be used to investigate preemptively to avoid myopathy in patients with increased risk.[105] This risk is determined by the single nucleotide polymorphism rs4149056, also known as 37041T>C or V174A. The rs4149056(C) SNP defines the SLCO1B1*5 allele of the SLCO1B1 gene.

References

- ^ Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (May 2008, reissued March 2010). "Lipid modification – Cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease – Quick reference guide" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore TH, Burke M, Davey Smith G, Ward K, Ebrahim S (2013). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5. PMID 23440795.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor F, Ward K, Moore TH, Burke M, Davey Smith G, Casas JP, Ebrahim S (2011). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub4. PMID 21249663.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Naci H, Brugts J, Ades T (2013). "Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246 955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials". Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 6 (4): 390–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000071. PMID 23838105.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Abd TT, Jacobson TA (May 2011). "Statin-induced myopathy: a review and update". Expert opinion on drug safety. 10 (3): 373–87. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.540568. PMID 21342078.

- ^ Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Cardiovascular drugs". Martindale: the complete drug reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 1155–434. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b c d e Simons, John. "The $10 billion pill", Fortune magazine, January 20, 2003.

- ^ "Doing Things Differently", Pfizer 2008 Annual Review, April 23, 2009, p. 15.

- ^ National Cholesterol Education Program (2001). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Executive Summary. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. p. 40. NIH Publication No. 01-3670.

- ^ National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (2010). NICE clinical guideline 67: Lipid modification (PDF). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 38.

- ^ Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore TH, Burke M, Davey Smith G, Ward K, Ebrahim S (2013). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5. PMID 23440795.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tonelli M, Lloyd A, Clement F, Conly J, Husereau D, Hemmelgarn B, Klarenbach S, McAlister FA, Wiebe N, Manns B (2011). "Efficacy of statins for primary prevention in people at low cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis". CMAJ. 183 (16): E1189–202. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101280. PMC 3216447. PMID 21989464.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kostis WJ, Cheng JQ, Dobrzynski JM, Cabrera J, Kostis JB (2012). "Meta-analysis of statin effects in women versus men". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59 (6): 572–82. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.067. PMID 22300691.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Petretta M, Costanzo P, Perrone-Filardi P, Chiariello M (2010). "Impact of gender in primary prevention of coronary heart disease with statin therapy: a meta-analysis". Int. J. Cardiol. 138 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.08.001. PMID 18793814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Erqou S, Sever P, Jukema JW, Ford I, Sattar N (2010). "Statins and all-cause mortality in high-risk primary prevention: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving 65,229 participants". Arch. Intern. Med. 170 (12): 1024–31. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.182. PMID 20585067.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bukkapatnam RN, Gabler NB, Lewis WR (2010). "Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Prev Cardiol. 13 (2): 84–90. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7141.2009.00059.x. PMID 20377811.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF).

- ^ "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF).

- ^ Stone, NJ; Robinson, J; Lichtenstein, AH; Merz, CN; Blum, CB; Eckel, RH; Goldberg, AC; Gordon, D; Levy, D; Lloyd-Jones, DM; McBride, P; Schwartz, JS; Shero, ST; Smith SC, Jr; Watson, K; Wilson, PW (Nov 12, 2013). "2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. PMID 24222016.

- ^ Grupo de Trabajo de la Sociedad Europea de Cardiología (ESC) y de la Sociedad Europea de Aterosclerosis, (EAS); Reiner, Z; Catapano, AL; De Backer, G; Graham, I; Taskinen, MR; Wiklund, O; Agewall, S; Alegría, E; John Chapman, M; Durrington, P; Erdine, S; Halcox, J; Hobbs, R; Kjekshus, J; Perrone Filardi, P; Riccardi, G; Storey, RF; Wood, D (Dec 2011). "ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias" (PDF). Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.). 64 (12): 1168. PMID 24776417.

- ^ Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR (June 2003). "Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 326 (7404): 1423. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. PMC 162260. PMID 12829554.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tonelli M, Lloyd A, Clement F, Conly J, Husereau D, Hemmelgarn B, Klarenbach S, McAlister FA, Wiebe N, Manns B (Nov 8, 2011). "Efficacy of statins for primary prevention in people at low cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association. 183 (16): E1189–E1202. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101280. PMC 3216447. PMID 21989464.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhou Z, Rahme E, Pilote L (2006). "Are statins created equal? Evidence from randomized trials of pravastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin for cardiovascular disease prevention". Am. Heart J. 151 (2): 273–81. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.003. PMID 16442888.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Vuorio, A; Kuoppala, J; Kovanen, PT; Humphries, SE; Strandberg, T; Tonstad, S; Gylling, H (Jul 7, 2010). "Statins for children with familial hypercholesterolemia". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (7): CD006401. PMID 20614444.

- ^ Lamaida, N; Capuano, E; Pinto, L; Capuano, E; Capuano, R; Capuano, V (Sep 2013). "The safety of statins in children". Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 102 (9): 857–62. PMID 23631461.

- ^ Braamskamp, MJ; Wijburg, FA; Wiegman, A (Apr 16, 2012). "Drug therapy of hypercholesterolaemia in children and adolescents". Drugs. 72 (6): 759–72. PMID 22512364.

- ^ table adapted from the following source, but check individual references for technical explanations

- Consumer Reports; Drug Effectiveness Review Project (March 2013), "Evaluating statin drugs to treat High Cholesterol and Heart Disease: Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF), Best Buy Drugs, Consumer Reports, p. 9, retrieved 27 March 2013

- ^ Asberg A (2003). "Interactions between cyclosporin and lipid-lowering drugs: Implications for organ transplant recipients". Drugs. 63 (4): 367–378. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363040-00003. PMID 12558459.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (1 March 2012). "Drug Safety and Availability; FDA Drug Safety Communication: Interactions between certain HIV or hepatitis C drugs and cholesterol-lowering statin drugs can increase the risk of muscle injury". fda.gov. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Bellosta S, Paoletti R, Corsini A (2004). "Safety of Statins: Focus on Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Drug Interactions". Circulation. 109 (23_suppl_1): III-I50. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000131519.15067.1f. PMID 15198967.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Omar MA, Wilson JP (2002). "FDA Adverse Event Reports on Statin-Associated Rhabdomyolysis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (2): 288–295. doi:10.1345/aph.1A289. PMID 11847951.

- ^ Armitage J (2007). "The safety of statins in clinical practice". The Lancet. 370 (9601): 1781–1790. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60716-8. PMID 17559928.

- ^ a b c Golomb BA, Evans MA (2008). "Statin Adverse Effects: A Review of the Literature and Evidence for a Mitochondrial Mechanism". Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 8 (6): 373–418. doi:10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004. PMC 2849981. PMID 19159124.

- ^ Silva MA, Swanson AC, Gandhi PJ, Tataronis GR (January 2006). "Statin-related adverse events: a meta-analysis". Clin Ther. 28 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.01.005. PMID 16490577.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Finegold JA, Manisty CH, Goldacre B, Barron AJ, Francis DP (Mar 12, 2014). "What proportion of symptomatic side effects in patients taking statins are genuinely caused by the drug? Systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials to aid individual patient choice". European journal of preventive cardiology. PMID 24623264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Anne Harding (August 28, 2007). "Docs often write off patient side effect concerns". Reuters. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ Holman JR. (2007). Some Docs in Denial About Statin Side Effects. Doc News.

- ^ Gaist D, Jeppesen U, Andersen M, García Rodríguez LA, Hallas J, Sindrup SH (2002). "Statins and risk of polyneuropathy – a case-control study". Neurology. 58 (9): 1333–1337. doi:10.1212/WNL.58.9.1333. PMID 12011277.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sandra G. Boodman (September 10, 2002). "Study links statins to nerve damage". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ Julie Appleby (2002-08-18). "Statin side effect rare, but be aware". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Ghirlanda G, Oradei A, Manto A, Lippa S, Uccioli L, Caputo S, Greco AV, Littarru GP (1993). "Evidence of plasma CoQ10-lowering effect by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study". J Clin Pharmacol. 33 (3): 226–9. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb03948.x. PMID 8463436.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marcoff L, Thompson PD (2007). "The role of coenzyme Q10 in statin-associated myopathy: a systematic review". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 (23): 2231–7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.049. PMID 17560286.

- ^ a b Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, Bowman L, Heath S, Matsuda F, Gut I, Lathrop M, Collins R (2008). "SLCO1B1 Variants and Statin-Induced Myopathy – A Genomewide Study". NEJM. 359 (8): 789–799. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. PMID 18650507.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Graham DJ, Staffa JA, Shatin D, Andrade SE, Schech SD, La Grenade L, Gurwitz JH, Chan KA, Goodman MJ, Platt R (2004). "Incidence of hospitalized rhabdomyolysis in patients treated with lipid-lowering drugs" (PDF). JAMA. 292 (21): 2585–90. doi:10.1001/jama.292.21.2585. PMID 15572716.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hanai J, Cao P, Tanksale P, Imamura S, Koshimizu E, Zhao J, Kishi S, Yamashita M, Phillips PS, Sukhatme VP, Lecker SH (2007). "The muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx mediates statin-induced muscle toxicity". J. Clin. Invest. 117 (12): 3940–51. doi:10.1172/JCI32741. PMC 2066198. PMID 17992259.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, Seshasai SR, McMurray JJ, Freeman DJ, Jukema JW, Macfarlane PW, Packard CJ, Stott DJ, Westendorp RG, Shepherd J, Davis BR, Pressel SL, Marchioli R, Marfisi RM, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L, Tognoni G, Kjekshus J, Pedersen TR, Cook TJ, Gotto AM, Clearfield MB, Downs JR, Nakamura H, Ohashi Y, Mizuno K, Ray KK, Ford I (2010). "Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials". Lancet. 375 (9716): 735–42. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6. PMID 20167359.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, Murphy SA, Ho JE, Waters DD, DeMicco DA, Barter P, Cannon CP, Sabatine MS, Braunwald E, Kastelein JJ, de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Pedersen TR, Tikkanen MJ, Sattar N, Ray KK (2011). "Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 305 (24): 2556–64. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.860. PMID 21693744.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jukema JW, Cannon CP, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Trompet S (Sep 4, 2012). "The controversies of statin therapy: weighing the evidence". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 60 (10): 875–81. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.007. PMID 22902202.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rutishauser J (Nov 21, 2011). "Statins in clinical medicine". Swiss medical weekly. 141: w13310. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13310. PMID 22101921.

- ^ Alsheikh-Ali AA, Maddukuri PV, Han H, Karas RH (2007). "Effect of the Magnitude of Lipid Lowering on Risk of Elevated Liver Enzymes, Rhabdomyolysis, and Cancer: Insights from Large Randomized Statin Trials". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 50 (5): 409–418. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.073. PMID 17662392.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, Kluger J, White CM (2006). "Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 295 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.74. PMID 16391219.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alsheikh-Ali AA, Karas RH (March 2009). "The relationship of statins to rhabdomyolysis, malignancy, and hepatic toxicity: evidence from clinical trials". Current atherosclerosis reports. 11 (2): 100–4. doi:10.1007/s11883-009-0016-8. PMID 19228482.

- ^ Singh S, Singh AG, Singh PP, Murad MH, Iyer PG (June 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of esophageal cancer, particularly in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 11 (6): 620–9. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.036. PMID 23357487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liu Y, Tang W, Wang J, Xie L, Li T, He Y, Deng Y, Peng Q, Li S, Qin X (Nov 22, 2013). "Association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 42 studies". Cancer causes & control : CCC. PMID 24265089.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wu XD, Zeng K, Xue FQ, Chen JH, Chen YQ (October 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis". European journal of clinical pharmacology. 69 (10): 1855–60. doi:10.1007/s00228-013-1547-z. PMID 23748751.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singh PP, Singh S (July 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 24 (7): 1721–30. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt150. PMID 23599253.

- ^ Pradelli D, Soranna D, Scotti L, Zambon A, Catapano A, Mancia G, La Vecchia C, Corrao G (May 2013). "Statins and primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies". European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP). 22 (3): 229–34. doi:10.1097/cej.0b013e328358761a. PMID 23010949.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang Y, Zang T (2013). "Association between statin usage and prostate cancer prevention: a refined meta-analysis based on literature from the years 2005–2010". Urologia internationalis. 90 (3): 259–62. doi:10.1159/000341977. PMID 23052323.

- ^ Bansal D, Undela K, D'Cruz S, Schifano F (2012). "Statin use and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies". PloS one. 7 (10): e46691. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046691. PMID 23049713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tan M, Song X, Zhang G, Peng A, Li X, Li M, Liu Y, Wang C (2013). "Statins and the risk of lung cancer: a meta-analysis". PloS one. 8 (2): e57349. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057349. PMID 23468972.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zhang XL, Liu M, Qian J, Zheng JH, Zhang XP, Guo CC, Geng J, Peng B, Che JP, Wu Y (Jul 23, 2013). "Statin use and risk of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized trials". British journal of clinical pharmacology. PMID 23879311.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Undela K, Srikanth V, Bansal D (August 2012). "Statin use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Breast cancer research and treatment. 135 (1): 261–9. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2154-x. PMID 22806241.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cui X, Xie Y, Chen M, Li J, Liao X, Shen J, Shi M, Li W, Zheng H, Jiang B (July 2012). "Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis". Cancer causes & control : CCC. 23 (7): 1099–111. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-9979-9. PMID 22562222.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang XL, Geng J, Zhang XP, Peng B, Che JP, Yan Y, Wang GC, Xia SQ, Wu Y, Zheng JH (April 2013). "Statin use and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis". Cancer causes & control : CCC. 24 (4): 769–76. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0159-3. PMID 23361339.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mayo clinic: article on interference between grapefruit and medication

- ^ Kane GC, Lipsky JJ (2000). "Drug-grapefruit juice interactions". Mayo Clin. Proc. 75 (9): 933–42. doi:10.4065/75.9.933. PMID 10994829.

- ^ Reamy BV, Stephens MB (2007). "The grapefruit-drug interaction debate: role of statins". Am Fam Physician. 76 (2): 190, 192, author reply 192. PMID 17695563.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ FDA Website Statins and HIV or Hepatitis C Drugs: Drug Safety Communication – Interaction Increases Risk of Muscle Injury

- ^ Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J (2001). "Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase". Science. 292 (5519): 1160–4. doi:10.1126/science.1059344. PMID 11349148.

- ^ a b Endo A (1 November 1992). "The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors" (PDF). J. Lipid Res. 33 (11): 1569–82. PMID 1464741.

- ^ Miettinen TA (March 1982). "Diurnal variation of cholesterol precursors squalene and methyl sterols in human plasma lipoproteins". Journal of Lipid Research. 23 (3): 466–73. PMID 7200504.

- ^ Saito Y, Yoshida S, Nakaya N, Hata Y, Goto Y (Jul–Aug 1991). "Comparison between morning and evening doses of simvastatin in hyperlipidemic subjects. A double-blind comparative study". Arterioscler Thromb. 11 (4): 816–26. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.11.4.816. PMID 2065035.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wallace A, Chinn D, Rubin G (4 October 2003). "Taking simvastatin in the morning compared with in the evening: randomised controlled trial". British Medical Journal. 327 (7418): 788. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7418.788. PMC 214096. PMID 14525878.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cilla DD, Gibson DM, Whitfield LR, Sedman AJ (July 1996). "Pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin after administration to normocholesterolemic subjects in the morning and evening". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (7): 604–9. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04224.x. PMID 8844442.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ma PT, Gil G, Südhof TC, Bilheimer DW, Goldstein JL, Brown MS (1986). "Mevinolin, an inhibitor of cholesterol synthesis, induces mRNA for low density lipoprotein receptor in livers of hamsters and rabbits" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 (21): 8370–4. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8370M. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.21.8370. PMC 386930. PMID 3464957.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Spindler SR, Li R, Dhahbi JM, Yamakawa A, Mote P, Bodmer R, Ocorr K, Williams RT, Wang Y, Ablao KP (June 2012). "Statin treatment increases lifespan and improves cardiac health in Drosophila by decreasing specific protein prenylation". PLoS One. 7 (6): e39581. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039581. PMID 22737247.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lahera V, Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Miana M, de las Heras N, Cachofeiro V, Luño J (2007). "Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerosis: beneficial effects of statins". Curr Med Chem. 14 (2): 243–8. doi:10.2174/092986707779313381. PMID 17266583.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferri N, Colombo G, Ferrandi C, Raines EW, Levkau B, Corsini A (May 2007). "Simvastatin reduces MMP1 expression in human smooth muscle cells cultured on polymerized collagen by inhibiting Rac1 activation". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 27 (5): 1043–9. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.139881. PMID 17303772.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thurnher M, Nussbaumer O, Gruenbacher G (Jul 2012). "Novel aspects of mevalonate pathway inhibitors as antitumor agents". Clin Cancer Res. 18 (13): 3524–31. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0489. PMID 22529099.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, Davignon J, Erbel R, Fruchart JC, Tardif JC, Schoenhagen P, Crowe T, Cain V, Wolski K, Goormastic M, Tuzcu EM (2006). "Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial". JAMA. 295 (13): 1556–65. doi:10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. PMID 16533939.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Furberg CD (19 January 1999). "Natural Statins and Stroke Risk". Circulation. 99 (2): 185–188. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.99.2.185. PMID 9892578.

- ^ Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT, Glynn RJ (2008). "Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein" (PDF). NEJM. 359 (21): 2195–207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. PMID 18997196.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Abramson J, Dodin S, Hamazaki T, Kostucki W, Okuyama H, Pavy B, Rabaeus M (Jun 28, 2010). "Cholesterol lowering, cardiovascular diseases, and the rosuvastatin-JUPITER controversy: a critical reappraisal". Archives of internal medicine. 170 (12): 1032–6. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.184. PMID 20585068.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Safety of Statins: Focus on Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Drug Interactions" Circulation 2004:109:III-50-IIIi-57

- ^ "Metabolism of cerivastatin by human liver microsomes in vitro. Characterization of primary metabolic pathways and of cytochrome P450 isozymes involved". Drug Metab Dispos. 25 (3): 321–31. Mar 1997.

- ^ Comparison of Cytochrome P-450-Dependent Metabolism and Drug Interactions of the 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors Lovastatin and Pravastatin in the Liver. DMD February 1, 1999 vol. 27 no. 2 173–179

- ^ Shepherd J, Hunninghake DB, Barter P, McKenney JM, Hutchinson HG (2003). "Guidelines for lowering lipids to reduce coronary artery disease risk: a comparison of rosuvastatin with atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin for achieving lipid-lowering goals". Am. J. Cardiol. 91 (5A): 11C–17C, discussion 17C–19C. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00004-3. PMID 12646338.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liu J, Zhang J, Shi Y, Grimsgaard S, Alraek T, Fønnebø V (2006). "Chinese red yeast rice (Monascus purpureus) for primary hyperlipidemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Chin Med. 1: 4. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-1-4. PMC 1761143. PMID 17302963.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Crystal and Molecular Structure of Compactin, a New Antifungal Metabolite from Penicillium brevicompactum." Alian G. Brown, Terry C. Smale, Trevor J. King, Rainer Hasenkamp and Ronald H. Thompson. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1, 1976, 1165–1170. doi:10.1039/P19760001165

- ^ Steinberg, Daniel. The Cholesterol Wars: The Skeptics vs. The Preponderance of Evidence. Academic Press, 2007, pp. 6–9.

- ^ "Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S)". Lancet. 344 (8934): 1383–9. November 1994. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90566-5. PMID 7968073.

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame Honors 2012 Inductees". PRNewswire. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ "How One Scientist Intrigued by Molds Found First Statin". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ Abramson J, Wright JM (2007). "Are lipid-lowering guidelines evidence-based?". Lancet. 369 (9557): 168–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60084-1. PMID 17240267.

- ^ Ravnskov U, Rosch PJ, Sutter MC, Houston MC (2006). "Should we lower cholesterol as much as possible?". BMJ. 332 (7553): 1330–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1330. PMC 1473073. PMID 16740566.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grimes DS (2006). "Are statins analogues of vitamin D?". Lancet. 368 (9529): 83–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68971-X. PMID 16815382.

- ^ Wolozin B, Wang SW, Li NC, Lee A, Lee TA, Kazis LE (July 19, 2007). "Simvastatin is associated with a reduced incidence of dementia and Parkinson's disease". BMC Medicine. 5: 20. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-5-20. PMC 1955446. PMID 17640385.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Khurana V, Bejjanki HR, Caldito G, Owens MW (May 2007). "Statins reduce the risk of lung cancer in humans: a large case-control study of US veterans". Chest. 131 (5): 1282–1288. doi:10.1378/chest.06-0931. PMID 17494779.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE, Grady LM (June 2006). "Statin use and incident nuclear cataract". JAMA. 295 (23): 2752–8. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.2752. PMID 16788130.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Golomb BA, Dimsdale JE, White HL, Ritchie JB, Criqui MH (April 2008). "Reduction in blood pressure with statins: results from the UCSD Statin Study, a randomized trial". Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (7): 721–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.7.721. PMID 18413554.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mondul AM, Han M, Humphreys EB, Meinhold CL, Walsh PC, Platz EA (February 2011). "Association of statin use with pathological tumor characteristics and prostate cancer recurrence after surgery". Journal of Urology. 185 (4): 1268–1273. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.089. PMID 21334020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chasman DI, Posada D, Subrahmanyan L, Cook NR, Stanton VP, Ridker PM (2004). "Pharmacogenetic study of statin therapy and cholesterol reduction". JAMA. 291 (23): 2821–7. doi:10.1001/jama.291.23.2821. PMID 15199031.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iakoubova OA, Sabatine MS, Rowland CM, Tong CH, Catanese JJ, Ranade K, Simonsen KL, Kirchgessner TG, Cannon CP, Devlin JJ, Braunwald E (2008). "Polymorphism in KIF6 Gene and Benefit from Statins After Acute Coronary Syndromes: Results from the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 Study". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 51 (4): 449–55. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.017. PMID 18222355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Huser V, Cimino JJ (2013). "Providing pharmacogenomics clinical decision support using whole genome sequencing data as input". AMIA Summits on Translational Science proceedings AMIA Summit on Translational Science. 2013: 81. PMC 3814493. PMID 24303303.

External links

- Statin page at Bandolier, an evidence-based medicine journal (little content after 2004)