Brand

Brand is the "name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller's product distinct from those of other sellers."[1] Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising. Initially, livestock branding was adopted to differentiate one person's cattle from another's by means of a distinctive symbol burned into the animal's skin with a hot branding iron. A modern example of a brand is Coca-Cola which belongs to the Coca-Cola Company.

In accounting, a brand defined as an intangible asset is often the most valuable asset on a corporation's balance sheet. Brand owners manage their brands carefully to create shareholder value, and brand valuation is an important management technique that ascribes a money value to a brand, and allows marketing investment to be managed (e.g.: prioritized across a portfolio of brands) to maximize shareholder value. Although only acquired brands appear on a company's balance sheet, the notion of putting a value on a brand forces marketing leaders to be focused on long term stewardship of the brand and managing for value.

The word "brand" is often used as a metonym referring to the company that is strongly identified with a brand.

Marque or make are often used to denote a brand of motor vehicle, which may be distinguished from a car model. A concept brand is a brand that is associated with an abstract concept, like breast cancer awareness or environmentalism, rather than a specific product, service, or business. A commodity brand is a brand associated with a commodity.

A logo often represents a specific brand.

History

| Marketing |

|---|

The word "brand" derives from the Old Norse "brandr" meaning "to burn" - recalling the practice of producers burning their mark (or brand) onto their products.[2]

The oldest generic brand, in continuous use in India since the Vedic period (ca. 1100 B.C.E to 500 B.C.E), is the herbal paste known as Chyawanprash, consumed for its purported health benefits and attributed to a revered rishi (or seer) named Chyawan.[3] This product was developed at Dhosi Hill, an extinct volcano in northern India.

The Italians used brands in the form of watermarks on paper in the 13th century.[4] Blind Stamps, hallmarks and silver-makers' marks are all types of brand.

Although connected with the history of trademarks[5] and including earlier examples which could be deemed "protobrands" (such as the marketing puns of the "Vesuvinum" wine jars found at Pompeii),[6] brands in the field of mass-marketing originated in the 19th century with the advent of packaged goods. Industrialization moved the production of many household items, such as soap, from local communities to centralized factories. When shipping their items, the factories would literally brand their logo or insignia on the barrels used, extending the meaning of "brand" to that of a trademark.

Bass & Company, the British brewery, claims their red-triangle brand as the world's first trademark. Tate & Lyle of Lyle's Golden Syrup makes a similar claim, having been recognized by Guinness World Records[7] as Britain's oldest brand, with its green-and-gold packaging having remained almost unchanged since 1885. Another example comes from Antiche Fornaci Giorgi in Italy, which has stamped or carved its bricks (as found in Saint Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City) with the same proto-logo since 1731.

Cattle were branded long before this. The term "maverick", originally meaning an unbranded calf, comes from Texas rancher Samuel Augustus Maverick whose neglected cattle often got loose and were rounded up by his neighbors. The word spread among cowboys and came to apply to unbranded calves found wandering alone.[8]

Factories established during the Industrial Revolution introduced mass-produced goods and needed to sell their products to a wider market - to customers previously familiar only with locally-produced goods. It quickly became apparent that a generic package of soap had difficulty competing with familiar, local products. The packaged-goods manufacturers needed to convince the market that the public could place just as much trust in the non-local product. Pears Soap, Campbell soup, Coca-Cola, Juicy Fruit gum, Aunt Jemima, and Quaker Oats were among the first products to be "branded" in an effort to increase the consumer's familiarity with their merits. Many brands of that era, such as Uncle Ben's rice and Kellogg's breakfast cereal furnish illustrations of the problem.

Around 1900, James Walter Thompson published a house ad explaining trademark advertising. This was an early commercial explanation of what we now know as branding. Companies soon adopted slogans, mascots, and jingles that began to appear on radio and early television. By the 1940s,[9] manufacturers began to recognize the way in which consumers were developing relationships with their brands in a social/psychological/anthropological sense.

Manufacturers quickly learned to build their brands' identity and personality such as youthfulness, fun or luxury. This began the practice we now know as "branding" today, where the consumers buy "the brand" instead of the product. This trend continued to the 1980s, and is now quantified in concepts such as brand value and brand equity. Naomi Klein has described this development as "brand equity mania".[10] In 1988, for example, Philip Morris purchased Kraft for six times what the company was worth on paper; it was felt[by whom?] that what they really purchased was its brand name.

Marlboro Friday: April 2, 1993 – marked by some as the death of the brand[10] – the day Philip Morris declared that they were cutting the price of Marlboro cigarettes by 20% in order to compete with bargain cigarettes. Marlboro cigarettes were noted[by whom?] at the time for their heavy advertising campaigns and well-nuanced brand image. In response to the announcement Wall Street stocks nose-dived[10] for a large number of branded companies: Heinz, Coca Cola, Quaker Oats, PepsiCo, Tide, Lysol. Many thought the event signalled the beginning of a trend towards "brand blindness" (Klein 13), questioning the power of "brand value".

Concepts

Effective branding can result in higher sales of not only one product, but of other products associated with that brand.[citation needed] For example, if a customer loves Pillsbury biscuits and trusts the brand, he or she is more likely to try other products offered by the company - such as chocolate-chip cookies, for example. Brand is the personality that identifies a product, service or company (name, term, sign, symbol, or design, or combination of them) and how it relates to key constituencies: customers, staff, partners, investors etc.[citation needed]

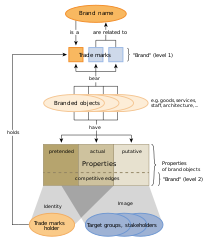

Some people[who?] distinguish the psychological aspect (brand associations like thoughts, feelings, perceptions, images, experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and so on that become linked to the brand) of a brand from the experiential aspect. The experiential aspect consists of the sum of all points of contact with the brand and is known[by whom?] as the brand experience. The brand experience is a brand's action perceived by a person.[citation needed] The psychological aspect, sometimes referred to as the brand image, is a symbolic construct created within the minds of people, consisting of all the information and expectations associated with a product, service or the company(ies) providing them.[citation needed]

People engaged in branding seek to develop or align the expectations behind the brand experience, creating the impression that a brand associated with a product or service has certain qualities or characteristics that make it special or unique. A brand can therefore become one of the most valuable elements in an advertising theme, as it demonstrates what the brand owner is able to offer in the marketplace. The art of creating and maintaining a brand is called brand management. Orientation of an entire organization towards its brand is called brand orientation. Brand orientation develops in response to market intelligence.[citation needed]

Careful brand management seeks to make the product or services relevant to the target audience. Brands should be seen as more than the difference between the actual cost of a product and its selling price – they represent the sum of all valuable qualities of a product to the consumer.

A widely known brand is said to have "brand recognition". When brand recognition builds up to a point where a brand enjoys a critical mass of positive sentiment in the marketplace, it is said to have achieved brand franchise. Brand recognition is most successful when people can state a brand without being explicitly exposed to the company's name, but rather through visual signifiers like logos, slogans, and colors.[11] For example, Disney successfully branded its particular script font (originally created for Walt Disney's "signature" logo), which it used in the logo for go.com.

Consumers may look on branding as an aspect of products or services, as it often serves to denote a certain attractive quality or characteristic (see also brand promise). From the perspective of brand owners, branded products or services can command higher prices. Where two products resemble each other, but one of the products has no associated branding (such as a generic, store-branded product), people may often select the more expensive branded product on the basis of the perceived quality of the brand or on the basis of the reputation of the brand owner.

Brand awareness

Brand awareness refers to customers' ability to recall and recognize the brand under different conditions and to link to the brand name, logo, jingles and so on to certain associations in memory. It consists of both brand recognition and brand recall. It helps the customers to understand to which product or service category the particular brand belongs and what products and services sell under the brand name. It also ensures that customers know which of their needs are satisfied by the brand through its products (Keller)[need quotation to verify]. Brand awareness is of critical importance in competitive situations, since customers will not consider a brand if they are not aware of it.[12]

Various levels of brand awareness require different levels and combinations of brand recognition and recall:

- Most companies aim for "Top-of-Mind". Top-of-mind awareness occurs when a brand pops into a consumer's mind when asked to name brands in a product category. For example, when someone is asked to name a type of facial tissue, the common answer is "Kleenex", represents a top-of-mind brand.

- Aided awareness occurs when consumers see or read a list of brands, and express familiarity with a particular brand only after they hear or see it as a type of memory aide.

- Strategic awareness occurs when a brand is not only top-of-mind to consumers, but also has distinctive qualities which consumers perceive as making it better than other brands in the particular market. The distinction(s) that set a product apart from the competition is/are also known as the Unique Selling Point or USP.

Marketing-mix modeling can help marketing leaders optimize how they spend marketing budgets to maximize the impact on brand awareness or on sales. Managing brands for value creation will often involve applying marketing-mix modeling techniques in conjunction with brand valuation.

Brand elements

Brands typically comprise various elements, such as:[13]

- name: the word or words used to identify a company, product, service, or concept

- logo: the visual trademark that identifies a brand

- tagline or catchphrase: "The Quicker Picker Upper" is associated with Bounty paper towels

- graphics: the "dynamic ribbon" is a trademarked part of Coca-Cola's brand

- shapes: the distinctive shapes of the Coca-Cola bottle and of the Volkswagen Beetle are trademarked elements of those brands

- colors: Owens-Corning is the only brand of fiberglass insulation that can be pink.

- sounds: a unique tune or set of notes can denote a brand. NBC's chimes provide a famous example.

- scents: the rose-jasmine-musk scent of Chanel No. 5 is trademarked

- tastes: Kentucky Fried Chicken has trademarked its special recipe of eleven herbs and spices for fried chicken

- movements: Lamborghini has trademarked the upward motion of its car doors

- customer-relationship management

Global brand variables

Brand name

The brand name is quite often used interchangeably with "brand", although it is more correctly used to specifically denote written or spoken linguistic elements of any product. In this context a "brand name" constitutes a type of trademark, if the brand name exclusively identifies the brand owner as the commercial source of products or services. A brand owner may seek to protect proprietary rights in relation to a brand name through trademark registration and such trademarks are called "Registered Trademarks". Advertising spokespersons have also become part of some brands, for example: Mr. Whipple of Charmin toilet tissue and Tony the Tiger of Kellogg's Frosted Flakes. Putting a value on a brand by brand valuation or using marketing mix modeling techniques is distinct to valuing a trade mark.

Types of brand names

Brand names come in many styles.[14]

A few include:

Initialism: A name made of initials such, as UPS or IBM

Descriptive: Names that describe a product benefit or function, such as Whole Foods or Toys R' Us

Alliteration and rhyme: Names that are fun to say and stick in the mind, such as Reese's Pieces or Dunkin' Donuts

Evocative: Names that evoke a relevant vivid image, such as Amazon or Crest

Neologisms: Completely made-up words, such as Wii or Häagen-Dazs.

Foreign word: Adoption of a word from another language, such as Volvo or Samsung

Founders' names: Using the names of real people, (especially a founder's name), such as Hewlett-Packard, Dell, Disney, Stussy or Mars

Geography: Many brands are named for regions and landmarks, such as Cisco and Fuji Film

Personification: Many brands take their names from myths, such as Nike; or from the minds of ad execs, such as Betty Crocker

Punny: Some brands create their name by using a silly pun, such as Lord of the Fries, Wok on Water or Eggs Eggscetera

The act of associating a product or service with a brand has become part of pop culture. Most products have some kind of brand identity, from common table salt to designer jeans. A brandnomer is a brand name that has colloquially become a generic term for a product or service, such as Band-Aid, Nylon, or Kleenex—which are often used to describe any brand of adhesive bandage; any type of hosiery; or any brand of facial tissue respectively. Xerox, for example, has become synonymous with the word "copy".

Brand Identifier

Open Knowledge Foundation created in December 2013 the BSIN (Brand Standard Identification Number). BSIN is universal and is used by the Open Product Data Working Group [15] of the Open Knowledge Foundation to assign a brand to a product. The OKFN Brand repository is critical for the Open Data movement.

Brand identity

The outward expression of a brand – including its name, trademark, communications, and visual appearance – is brand identity.[16] Because the identity is assembled by the brand owner, it reflects how the owner wants the consumer to perceive the brand – and by extension the branded company, organization, product or service. This is in contrast to the brand image, which is a customer's mental picture of a brand.[16] The brand owner will seek to bridge the gap between the brand image and the brand identity. Brand identity is fundamental to consumer recognition and symbolizes the brand's differentiation from competitors.

Brand identity is what the owner wants to communicate to its potential consumers. However, over time, a product's brand identity may acquire (evolve), gaining new attributes from consumer perspective but not necessarily from the marketing communications an owner percolates to targeted consumers. Therefore businesses research consumer's brand associations.[17]

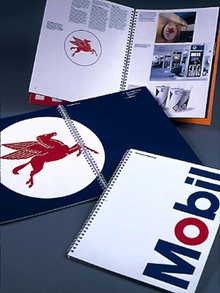

Visual brand identity

A brand can also be used to attract customers by a company, if the brand of a company is well established and has goodwill.The recognition and perception of a brand is highly influenced by its visual presentation. A brand’s visual identity is the overall look of its communications. Effective visual brand identity is achieved by the consistent use of particular visual elements to create distinction, such as specific fonts, colors, and graphic elements. At the core of every brand identity is a brand mark, or logo. In the United States, brand identity and logo design naturally grew out of the Modernist movement in the 1950s and greatly drew on the principles of that movement – simplicity (Mies van der Rohe’s principle of "Less is more") and geometric abstraction. These principles can be observed in the work of the pioneers of the practice of visual brand identity design, such as Paul Rand, Chermayeff & Geismar and Saul Bass.

Color is a particularly important element of visual brand identity and color mapping provides an effective way of ensuring color contributes to differentiation in a visually cluttered marketplace (O'Connor, 2011).[18]

Brand trust

Brand trust is the intrinsic 'believability' that any entity evokes. In the commercial world, the intangible aspect of Brand trust impacts the behavior and performance of its business stakeholders in many intriguing ways. It creates the foundation of a strong brand connect with all stakeholders, converting simple awareness to strong commitment. This, in turn, metamorphoses normal people who have an indirect or direct stake in the organization into devoted ambassadors, leading to concomitant advantages like easier acceptability of brand extensions, perception of premium, and acceptance of temporary quality deficiencies.

The Brand Trust Report is a syndicated primary research that has elaborated on this metric of brand trust. It is a result of action, behavior, communication and attitude of an entity, with the most Trust results emerging from its action component. Action of the entity is most important in creating trust in all those audiences who directly engage with the brand, the primary experience carrying primary audiences. However, the tools of communications play a vital role in the transferring the trust experience to audiences which have never experienced the brand, the all important secondary audience.

Brand parity

Brand parity is the perception of the customers that some brands are equivalent.[19] This means that shoppers will purchase within a group of accepted brands rather than choosing one specific brand. When brand parity is present, quality is often not a major concern because consumers believe that only minor quality differences exist.

Expanding role of brand

It was meant to make identifying and differentiating a product easier, while also providing the benefit of letting the name sell a second rate product. Over time, brands came to embrace a performance or benefit promise, for the product, certainly, but eventually also for the company behind the brand. Today, brand plays a much bigger role. Brands have been co-opted as powerful symbols in larger debates about economics, social issues, and politics. The power of brands to communicate a complex message quickly and with emotional impact and the ability of brands to attract media attention, make them ideal tools in the hands of activists.[20] Cultural conflict over a brand's meaning have also been shown to influence the diffusion of an innovation.[21]

Branding strategies

Company name

Often, especially in the industrial sector, it is just the company's name which is promoted (leading to[citation needed] one of the most powerful statements of branding: saying just before the company's downgrading. This approach has not worked as well for General Motors, which recently overhauled how its corporate brand relates to the product brands.[22] Exactly how the company name relates to product and services names is known as brand architecture. Decisions about company names and product names and their relationship depends on more than a dozen strategic considerations.[23]

In this case a strong brand name (or company name) is made the vehicle for a range of products (for example, Mercedes-Benz or Black & Decker) or a range of subsidiary brands (such as Cadbury Dairy Milk, Cadbury Flake or Cadbury Fingers in the UK).

Individual branding

Each brand has a separate name (such as Seven-Up, Kool-Aid or Nivea Sun (Beiersdorf)), which may compete against other brands from the same company (for example, Persil, Omo, Surf and Lynx are all owned by Unilever).

Attitude branding and iconic brands

Attitude branding is the choice to represent a larger feeling, which is not necessarily connected with the product or consumption of the product at all. Marketing labeled as attitude branding include that of Nike, Starbucks, The Body Shop, Safeway, and Apple Inc.. In the 2000 book No Logo,[10] Naomi Klein describes attitude branding as a "fetish strategy".

"A great brand raises the bar – it adds a greater sense of purpose to the experience, whether it's the challenge to do your best in sports and fitness, or the affirmation that the cup of coffee you're drinking really matters." – Howard Schultz (president, CEO, and chairman of Starbucks)

Iconic brands are defined as having aspects that contribute to consumer's self-expression and personal identity. Brands whose value to consumers comes primarily from having identity value are said to be "identity brands". Some of these brands have such a strong identity that they become more or less cultural icons which makes them "iconic brands". Examples are: Apple, Nike and Harley Davidson. Many iconic brands include almost ritual-like behaviour in purchasing or consuming the products.

There are four key elements to creating iconic brands (Holt 2004):

- "Necessary conditions" – The performance of the product must at least be acceptable, preferably with a reputation of having good quality.

- "Myth-making" – A meaningful storytelling fabricated by cultural insiders. These must be seen as legitimate and respected by consumers for stories to be accepted.

- "Cultural contradictions" – Some kind of mismatch between prevailing ideology and emergent undercurrents in society. In other words a difference with the way consumers are and how they wish they were.

- "The cultural brand management process" – Actively engaging in the myth-making process in making sure the brand maintains its position as an icon.

"No-brand" branding

Recently a number of companies have successfully pursued "no-brand" strategies by creating packaging that imitates generic brand simplicity. Examples include the Japanese company Muji, which means "No label" in English (from 無印良品 – "Mujirushi Ryohin" – literally, "No brand quality goods"), and the Florida company No-Ad Sunscreen. Although there is a distinct Muji brand, Muji products are not branded. This no-brand strategy means that little is spent on advertisement or classical marketing and Muji's success is attributed to the word-of-mouth, a simple shopping experience and the anti-brand movement.[24][25][26] "No brand" branding may be construed as a type of branding as the product is made conspicuous through the absence of a brand name. "Tapa Amarilla" or "Yellow Cap" in Venezuela during the 1980s is another good example of no-brand strategy. It was simply recognized by the color of the cap of this cleaning products company.

Derived brands

In this case the supplier of a key component, used by a number of suppliers of the end-product, may wish to guarantee its own position by promoting that component as a brand in its own right. The most frequently quoted example is Intel, which positions itself in the PC market with the slogan (and sticker) "Intel Inside".

Brand extension and brand dilution

The existing strong brand name can be used as a vehicle for new or modified products; for example, many fashion and designer companies extended brands into fragrances, shoes and accessories, home textile, home decor, luggage, (sun-) glasses, furniture, hotels, etc.

Mars extended its brand to ice cream, Caterpillar to shoes and watches, Michelin to a restaurant guide, Adidas and Puma to personal hygiene. Dunlop extended its brand from tires to other rubber products such as shoes, golf balls, tennis racquets and adhesives. Frequently, the product is no different from what else is on the market, except a brand name marking. Brand is Product identity.

There is a difference between brand extension and line extension. A line extension is when a current brand name is used to enter a new market segment in the existing product class, with new varieties or flavors or sizes.

When Coca-Cola launched "Diet Coke" and "Cherry Coke" they stayed within the originating product category: non-alcoholic carbonated beverages. Procter & Gamble (P&G) did likewise extending its strong lines (such as Fairy Soap) into neighboring products (Fairy Liquid and Fairy Automatic) within the same category, dish washing detergents.

The risk of over-extension is brand dilution where the brand loses its brand associations with a market segment, product area, or quality, price or cachet.[citation needed]

Social media brands

In 'The Better Mousetrap: Brand Invention in a Media Democracy' (2012) author and brand strategist Simon Pont posits that social media brands may be the most evolved version of the brand form, because they focus not on themselves but on their users. In so doing, social media brands are arguably more charismatic, in that consumers are compelled to spend time with them, because the time spent is in the meeting of fundamental human drivers related to belonging and individualism. "We wear our physical brands like badges, to help define us – but we use our digital brands to help express who we are. They allow us to be, to hold a mirror up to ourselves, and it is clear. We like what we see." [27]

Multi-brands

Alternatively, in a market that is fragmented amongst a number of brands a supplier can choose deliberately to launch totally new brands in apparent competition with its own existing strong brand (and often with identical product characteristics); simply to soak up some of the share of the market which will in any case go to minor brands. The rationale is that having 3 out of 12 brands in such a market will give a greater overall share than having 1 out of 10 (even if much of the share of these new brands is taken from the existing one). In its most extreme manifestation, a supplier pioneering a new market which it believes will be particularly attractive may choose immediately to launch a second brand in competition with its first, in order to pre-empt others entering the market. This strategy is widely known as multi-brand strategy.

Individual brand names naturally allow greater flexibility by permitting a variety of different products, of differing quality, to be sold without confusing the consumer's perception of what business the company is in or diluting higher quality products.

Once again, Procter & Gamble is a leading exponent of this philosophy, running as many as ten detergent brands in the US market. This also increases the total number of "facings" it receives on supermarket shelves. Sara Lee, on the other hand, uses it to keep the very different parts of the business separate — from Sara Lee cakes through Kiwi polishes to L'Eggs pantyhose. In the hotel business, Marriott uses the name Fairfield Inns for its budget chain (and Choice Hotels uses Rodeway for its own cheaper hotels).

Cannibalization is a particular problem of a multi-brand strategy approach, in which the new brand takes business away from an established one which the organization also owns. This may be acceptable (indeed to be expected) if there is a net gain overall. Alternatively, it may be the price the organization is willing to pay for shifting its position in the market; the new product being one stage in this process.

Private labels

Private label brands, also called own brands, or store brands have become popular. Where the retailer has a particularly strong identity (such as Marks & Spencer in the UK clothing sector) this "own brand" may be able to compete against even the strongest brand leaders, and may outperform those products that are not otherwise strongly branded.

Individual and organizational brands

There are kinds of branding that treat individuals and organizations as the products to be branded. Personal branding treats persons and their careers as brands. The term is thought to have been first used in a 1997 article by Tom Peters.[28] Faith branding treats religious figures and organizations as brands. Religious media expert Phil Cooke has written that faith branding handles the question of how to express faith in a media-dominated culture.[29] Nation branding works with the perception and reputation of countries as brands.[30]

Crowd sourcing branding

These are brands that are created by "the public" for the business, which is opposite to the traditional method where the business create a brand.

Nation branding (place branding and public diplomacy)

Nation branding is a field of theory and practice which aims to measure, build and manage the reputation of countries (closely related to place branding). Some approaches applied, such as an increasing importance on the symbolic value of products, have led countries to emphasise their distinctive characteristics. The branding and image of a nation-state "and the successful transference of this image to its exports – is just as important as what they actually produce and sell."

Destination Branding

Destination Branding is the work of cities, states, and other localities to promote to themselves. This work is designed to promote the location to tourists and drive additional revenues into a tax base. These activities are often undertaken by governments, but can also result from the work of community associations. The Destination Marketing Association International is the industry leading organization.

See also

- Brand ambassador

- Brand architecture

- Brand engagement

- Brand equity

- Brand evangelism

- Brand loyalty

- Brand valuation

- Green brands

- Visual brand language

References

- ^ American Marketing Association Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-06-29. The Marketing Accountability Standards Board (MASB) endorses this definition as part of its ongoing Common Language in Marketing Project.

- ^ 11.01.2006. "MarketingMagazine.co.uk". MarketingMagazine.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ Sanskrit Epic Mahabharat, Van Parva, p. 3000, Shalok 15–22

- ^ Colapinto, John (3 October 2011). "Famous Names". The New Yorker. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "(U.S.) Trademark History Timeline". Lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ Jstor.org

- ^ Hibbert, Colette. "Golden celebration for 'oldest brand'". BBC News UK.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:1495731 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=1495731instead. - ^ Mildred Pierce, Newmediagroup.co.uk

- ^ a b c d [page needed] Klein, Naomi (2000) No logo, Canada: Random House, ISBN 0-676-97282-9

- ^ "Brand Recognition Definition". Investopedia. 2013-04-19. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ Tan, Donald (2010). "Success Factors In Establishing Your Brand" Franchising and Licensing Association. Retrieved from http://www.flasingapore.org/info_branding.php

- ^ Robert Pearce. "Beyond Name and Logo: Other Elements of Your Brand « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ "MerriamAssociates.com". MerriamAssociates.com. 2012-11-15. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ http://product.okfn.org

- ^ a b Neumeier, Marty (2004), The Dictionary of Brand. ISBN 1-884081-06-1, pp.20

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ O'Connor, Z. "Logo colour and differentiation: A new application of environmental colour mapping". Color Research & Application, 36 (1), pp. 55–60. Also available from Colour & Design Research.

- ^ Paul S. Richardson, Alan S. Dick and Arun K. Jain "Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cue Effects on Perceptions of Store Brand Quality", Journal of Marketing October 1994 pp. 28-36

- ^ Bianca (2010-12-10). "Wikileaks, Hacktivism and Brands as Political Symbols « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ Giesler, Markus (2012), “How Doppelgänger Brand Images Influence the Market Creation Process: Longitudinal Insights from the Rise of Botox Cosmetic,” Journal of Marketing, November 2012.

- ^ "General Motors: A Reorganized Brand Architecture for a Reorganized Company « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. 2010-11-22. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ Nisha Roy (nisharoy) – Pearltrees. "Brand Architecture: Strategic Considerations « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ "Muji brand strategy, Muji branding, no name brand". VentureRepublic. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ Matt Heig, Brand Royalty: How the World's Top 100 Brands Thrive and Survive, pg.216

- ^ EMEASEE.com

- ^ [2], 'The Better Mousetrap: Brand Invention in a Media Democracy' (2013) Simon Pont. Kogan Page. ISBN 978-0749466213

- ^ Tom Peters (August 1997). "The brand Called You". Fast Company. No. 10. Mansueto Ventures LLC. p. 83.

- ^ Cooke, Phil; Branding Faith: Why Some Churches and Nonprofits Impact Culture and Others Don't; Regal, 2008; ISBN 978-0-8307-4563-0

- ^ On "island branding" see, for example, Henry Johnson (2012), ‘Genuine Jersey’: Branding and Authenticity in a Small Island Culture. Island Studies Journal 7 (2): 235–58.

Bibliography

- Birkin, Michael (1994). "Assessing Brand Value," in Brand Power. ISBN 0-8147-7965-4

- Fan, Y. (2002) “The National Image of Global Brands”, Journal of Brand Management, 9:3, 180–92, available at Brunel.ac.uk

- Gregory, James (2003). Best of Branding. ISBN 0-07-140329-9

- Holt, DB (2004). "How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding" Harvard University Press, Harvard MA

- Klein, Benjamin (2008). "Brand Names". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Klein, Naomi (2000) No logo, Canada: Random House, ISBN 0-676-97282-9

- Kotler, Philip (2004). "Marketing Management", ISBN 81-7808-654-9

- Kotler, Philip and Pfoertsch, Waldemar (2006). B2B Brand Management, ISBN 3-540-25360-2.

- Martins, Jose Souza (2000) The Emotional Nature of a Brand: Creating images to become world leaders. Brazil: Marts Plan Imagen Ltda.

- Miller & Muir (2004). The Business of Brands, ISBN 0-470-86259-9.

- Olins, Wally (2003). On Brand, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-51145-4.

- Schmidt, Klaus and Chris Ludlow (2002). Inclusive Branding: The Why and How of a Holistic approach to Brands. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-98079-4

- Wernick, Andrew (1991). Promotional Culture: Advertising, Ideology and Symbolic Expression (Theory, Culture & Society S.), London: Sage Publications, ISBN 0-8039-8390-5

- Knapp, Duane (2008). "The Brand Promise", New York: McGraw-Hill ISBN 978-0-07-149441-0