Moro Rebellion

| Moro Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Philippine–American War | |||||||

American soldiers battling with Moro fighters. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Jikiri[2][3][4] Panglima Hassan |

John J. Pershing Leonard Wood | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| unknown | 25,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy, official casualties are unknown |

United States: 130 killed 270 wounded Philippine Scouts: 111 killed 109 wounded Philippine Constabulary: 1,706 casualties[5]: 248 | ||||||

The Moro Rebellion (1899–1913) was an armed conflict between the Moro people and the United States military.

The word "Moro" is a term for ethnic Muslims who lived in the Southern Philippines, an area that includes Mindanao, Jolo and the neighboring Sulu Archipelago.

Background

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Moros have a 400-year history of resisting foreign rule. The violent armed struggle against the Filipinos, Americans, Japanese and Spanish is considered by current Moro (Muslim) leaders as part of the four centuries long "national liberation movement" of the Bangsamoro (Moro Nation).[6][neologism?] The 400-year-long resistance against the Japanese, Americans, and Spanish by the Moros (Muslims) persisted and developed into their current war for independence against the Philippine state.[7] A "culture of jihad" emerged among the Moros due to the centuries long war against the Spanish invaders.[8]

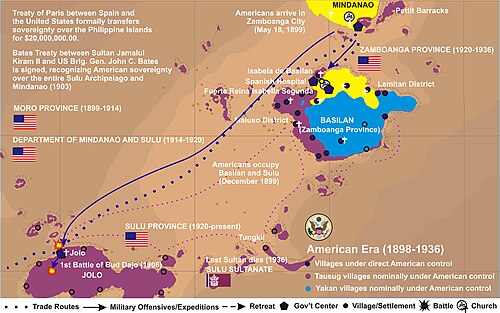

The United States claimed the territories of the Philippines after the Spanish–American War. The ethnic Moro (Muslim) population of the southern Philippines resisted both Spanish and United States colonization. The Spaniards were restricted to a handful of coastal garrisons or Forts and they made occasional punitive expeditions into the vast interior regions. After a series of unsuccessful attempts during the centuries of Spanish rule in the Philippines, Spanish forces occupied the abandoned city of Jolo, Sulu, the seat of the Sultan of Sulu, in 1876. The Spaniards and the Sultan of Sulu signed the Spanish Treaty of Peace on July 22, 1878. Control of the Sulu archipelago outside of the Spanish garrisons was handed to the Sultan. The treaty had translation errors: According to the Spanish-language version, Spain had complete sovereignty over the Sulu archipelago, while the Tausug version described a protectorate instead of an outright dependency.[9] Despite the very nominal claim to the Moro territories, Spain ceded them to the United States in the Treaty of Paris which signaled the end of the Spanish–American War.

Following the American occupation of the Northern Philippines during 1899, Spanish forces in the Southern Philippines were abolished, and they retreated to the garrisons at Zamboanga and Jolo. American forces took control over the Spanish government in Jolo on May 18, 1899, and at Zamboanga in December 1899.[10]

The Moros resisted the new American colonizers as they had resisted the Spanish.[11] The Spanish, American, and Philippine governments have all been fought against by the Muslims of Sulu and Mindanao.[12]

Ottoman Empire's role

John Hay, the American Secretary of State, asked the ambassador to Ottoman Empire, Oscar Straus in 1899 to approach Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II to request that the Sultan write a letter to the Moro Sulu Muslims of the Sulu Sultanate in the Philippines telling them to submit to American suzerainty and American military rule. Despite the sultan's "pan-Islamic" ideology, he readily aided the American forces because he felt no need to cause hostilities between the West and Muslims.[13]

Abdul Hamid wrote the letter, which was sent to Mecca where two Sulu chiefs brought it home to Sulu.[14] It was successful, and the "Sulu Mohammedans . . . refused to join the insurrectionists and had placed themselves under the control of [the American] army, thereby recognizing American sovereignty."[15][16] John P. Finley wrote that:

After due consideration of these facts, the Sultan, as Caliph caused a message to be sent to the Mohammedans of the Philippine Islands forbidding them to enter into any hostilities against the Americans, inasmuch as no interference with their religion would be allowed under American rule. As the Moros have never asked more than that, it is not surprising, that they refused all overtures made, by Aguinaldo's agents, at the time of the Filipino insurrection. President McKinley sent a personal letter of thanks to Mr. Straus for the excellent work he had done, and said, its accomplishment had saved the United States at least twenty thousand troops in the field. If the reader will pause to consider what this means in men and also the millions in money, he will appreciate this wonderful piece of diplomacy, in averting a holy war.[17][18]

President McKinley did not mention the Ottoman Empire's role in the pacification of the Sulu Moros in his address to the first session of the Fifty-sixth Congress in December 1899 since the agreement with the Sultan of Sulu was not submitted to the Senate until December 18.[19]

Cause of the war

After the American government informed the Moros that they would continue the old protectorate relationship that they had with Spain, the Moro Sulu Sultan rejected this and demanded that a new treaty be negotiated. The United States signed the Bates Treaty with the Moro Sulu Sultanate which guaranteed the Sultanate's autonomy in its internal affairs and governance, including article X that guaranteed preservation of slavery, while America dealt with its foreign relations, in order to keep the Moros out of the Philippine–American War. Once the Americans subdued the northern Filipinos, the Bates Treaty with the Moros was adjusted by the Americans through removal of article X and they invaded Moroland.[20][21][22][23][24][25]

After the war in 1915, the Americans imposed the Carpenter Treaty on Sulu.[26]

Philippine–American War events

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

First Republic forces in the southern Philippines were commanded by General Nicolas Capistrano, and American forces conducted an expedition against him in the winter of 1900–1901. On March 27, 1901, Capistrano surrendered. A few days later, General Emilio Aguinaldo was captured in Luzon.[27] This major victory in the war in the north allowed the Americans to devote more resources to the south, and they began to push into the interior of Bangsamoro.[neologism?]

On August 31, 1901, Brig. Gen. George Whitefield Davis replaced Kobbe as the commander of the Department of Mindanao-Jolo. Davis adopted a conciliatory policy towards the Moros. American forces under his command had standing orders to buy Moro produce when possible and to have "heralds of amity" precede all scouting expeditions. Peaceful Moros would not be disarmed. Polite reminders of America's anti-slavery policy were allowed.

One of Davis' subordinates, Captain John J. Pershing, assigned to the American garrison at Iligan, set out to better relations with the Moros of the Maranao tribes on the northern shore of Lake Lanao. He successfully established friendly relations with Amai-Manabilang, the retired Sultan of Madaya. Although retired, Manabilang was the single most influential personage among the fragmented inhabitants of the northern shore of the lake. His alliance did much to secure American standing in the area.

Conflict

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

Not all of Davis' subordinates were as diplomatic as Pershing. Many veterans of the Indian Wars took the "only good Indian is a dead Indian" mentality with them to the Philippines, and "civilize 'em with a Krag" became a similar catchphrase.[28][29]

Three ambushes of American troops by Moros, one of which involved Juramentados, occurred to the south of Lake Lanao, outside of Manabilang's sphere of influence. These events prompted Maj. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, the military governor of the Philippines, to issue a declaration on April 13, 1902, demanding that the offending Datu hand over the killers of American troops and stolen government property.

Not compliant, a punitive expedition under Col. Frank Baldwin set out to settle matters with the south-shore Moros. Although an excellent officer, Baldwin was "eager," and a worried Davis joined the expedition as an observer. On May 2, 1902, Baldwin's expedition attacked a Moro cotta (fortress) at the Battle of Pandapatan, also known as the Battle of Bayan. Pandapatan's defenses were unexpectedly strong, leading to 18 American casualties during the fighting. On the second day, the Americans used ladders and moat-bridging tools to break through the Moro fortifications, and a general slaughter of the Moro defenders followed.

The expeditionary force built at Camp Vickers one mile south of Pandapatan, and Davis assigned Pershing to Baldwin's command as an intelligence officer and as director of Moro affairs. As director, 'Black Jack' Pershing had a veto over Baldwin's movements, which was an unstable arrangement. This arrangement was tested when survivors of Pandapatan began building a Cotta at Bacalod. Baldwin wanted to move on the hostile Moros immediately, but Pershing warned that doing so could create an anti-American coalition of the surrounding Datus, while some patient diplomacy could establish friendly relations with most of the Moros, isolating the hostile minority. Baldwin grudgingly agreed. On June 30, Pershing assumed command of Camp Vickers, and Baldwin returned to Malabang. A command the size of Camp Vickers would normally have gone to an officer with the rank of Major, and a careful shuffling of personnel would be required to ensure that reinforcements to the Camp did not include officers that were senior to Pershing.

On July 4, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt issued a proclamation declaring an end to the Philippine Insurrection and a cessation of hostilities in the Philippines "except in the country inhabited by the Moro tribes, to which this proclamation does not apply."[30] Later that month, Davis was promoted and replaced Chaffee as the supreme commander of American forces in the Philippines. Command of the Mindanao-Jolo Department went to Brig. Gen. Samuel S. Sumner. Meanwhile, Pershing settled down to conduct diplomacy with the surrounding Moros, and a July 4th celebration had 700 guests from neighboring rancherias. In September 1902, he led the Masiu Expedition, which resulted in a victory that did much to establish American dominance in the area. On February 10, 1903, Pershing was declared a Datu by the formerly hostile Pandita Sajiduciaman of the Bayan Moros (who had been defeated at the Battle of Pandapatan)—the only American to be so honored. Pershing's career at Camp Vickers culminated in the March Around Lake Lanao during April and May 1903. Dansalan also known as the Marawi Expedition, it included the Battle of Bacolod and First Battle of Taraka but was otherwise peaceful. This expedition quickly became a symbol of American control of the Lake Lanao region and was regarded with dismay by the Moro Maranao inhabitants of that region.

While Pershing was working to the south of Lake Lanao, Major Robert Lee Bullard was working to the north, building a road from Iligan to Marawi. Although never officially declared one, like Pershing, he was regarded as a Datu by the Moros. Because of the Lake Lanao Moros' very personalistic style of leadership, they had troubles seeing them as two officers in the same army. Instead, they saw them as two powerful chieftains who might become rivals. During Pershing's March Around Lake Lanao, one Moro ran to Bullard, exclaiming that Pershing had gone Juramentado, meaning berserk and that Bullard had better run up the white flag (signaling that they had no quarrel with Pershing's troops). Bullard was unable to explain to the Moro why he was not worried about Pershing's approach. On another occasion, a powerful datu proposed an alliance with Bullard, for the purposes of defeating Pershing and establishing overlordship over the entire Lake Lanao region. On June 1, 1903, the Moro Province was created, which included "all of the territory of the Philippines lying south of the eight parallel of latitude, excepting the island of Palawan and the eastern portion of the northwest peninsula of Mindanao."[31] The province had a civil government, but many civil service positions, including the district governors and their deputies, were held by members of the American military. The governor of the province served as the commander of the Department of Mindanao-Jolo. This system of combined civil and military administration had several motivations behind it. One was the continued Moro hostilities. Another was the Army's experience during the Indian Wars, when it came into conflict with the civilian Bureau of Indian Affairs. A third was that the Moros, with their feudal, personalistic style of government, would have no respect for a military leader who submitted to the authority of a non-combatant.

In addition to the executive branch, under the governor, the province also had a legislative branch: the Moro Council. This Council "consisted of the governor, a state attorney, a secretary, a treasurer, a superintendent of schools, and an engineer."[32] Although the governor appointed all of the other members of the council, this body was permanent, and provided a more solid foundation for laws than the fiats of the governor, which might be overturned by his successor.

The province was divided into five districts, with American officers serving as district governors and deputy governors. These districts included: Cotabato, Davao, Lanao, Sulu, and Zamboanga. The districts were sub-divided into tribal wards, with major datus serving as ward chiefs and minor datus serving as deputies, judges, and sheriffs. This system took advantage of the existing structure of Moro political society, which was based on personal ties, while paving the way for a more individualistic society, where the office, not the person holding it, would be given respect.

On August 6, 1903, Major General Leonard Wood assumed his position as the governor of Moro Province and commander of the Department of Mindanao-Jolo. Wood was somewhat heavy-handed in his dealing with the Moros, being "personally offended by the Moro propensity for blood feuds, polygamy, and human trafficking"[33] and with his "ethnocentrism sometimes [leading] him to impose American concepts too quickly in Moroland."[34] In addition to his views of the Moros, Wood also faced an uphill Senate battle over his appointment to the rank of Major General, which was finally confirmed on March 19, 1904. This drove him to seek military laurels in order to shore up his lack of field experience, sometimes leading the Provincial army on punitive expeditions over minor incidents that would have been better handled diplomatically by the district governors. The period of Wood's governorship had the hardest and bloodiest fighting of America's occupation of Moroland.

Some of the Moros fighting against the American troops were women who dressed exactly the same as men. This led to the song sung by American troops called "If a Lady's Wearin' Pantaloons".[35][36][37][38][39][40]

The Province under Leonard Wood (1903–1906)

Wood instituted many changes during his tenure as governor of Moro Province:

- On Wood's recommendation, the United States unilaterally abrogated the Bates Treaty, citing continuing piracy and attacks on American personnel. The Sultan of Sulu was demoted to a purely religious office, with no more power than any other datu, and was provided with a small salary. The United States assumed direct control over Moroland.

- Slavery was abolished. Slave trading and raiding were repressed, but slaves were left with their owners. Wood announced that slaves were "at liberty to go and build homes for themselves wherever they like[d]," and pledged the military's protection for any former slaves that did so. Similar actions had been taken by individual commanders in the past, but Wood's edict had the backing of the Moro Council, giving it more permanent weight.

- The Cedula Act of 1903 created an annual registration poll tax. This registration poll tax was highly unpopular with the Moros, since they interpreted it as a form of tribute.[31] According to Hurley, participation in the Cedula was very low as late as 1933.[31]

- The legal code of Moroland was reformed. Disputes between Moros and non-Christians had been left to Moro laws and customs, with Philippine laws only applying to disputes with Christians. This led to a double standard, with a Moro who killed a Christian facing a stiff prison sentence, but with a Moro who killed another Moro facing only a maximum fine of 150 pesos. Wood attempted to codify Moro law, but there was simply too much variance in laws and customs between the different tribes and even between neighboring cottas. Wood placed the Moros underneath the Philippine criminal code, but actual enforcement of this proved difficult.

- Private land ownership was introduced, in order to help the Moros transition to a more individualistic society from their traditional tribal society. Each family was given 40 acres (16 ha) of land, with datus given additional land in accordance with their status. Land sales had to be approved by the district governments in order to prevent fraud.

- An educational system was established. By June 1904, there were 50 schools with an average enrollment of 30 students each. Because of difficulties in getting teachers that spoke native languages, classes were conducted in English after initial training in that language. Many Moros were suspicious of the schools, but some offered buildings for use as schools.

- Trade was encouraged in order to give the Moros an alternative to fighting. Trade had been discouraged by banditry, piracy, and the possibility of intertribal disputes between Moro merchants and local customers. When trading with foreign merchants (usually maritime Chinese), a lack of warehousing made for a buyer's market, leading to low prices. Wood handled banditry and piracy by establishing military posts at river mouths in order to protect sea and land routes. Starting with a pilot project in Zamboanga, a system of Moro Exchanges were established. These exchanges provided Moro traders with warehouses and temporary housing in exchange for honoring a ban on fighting within the exchange. Bulletin-boards listed market prices in Hong Kong and Singapore, and the district governments guaranteed fair prices. These Exchanges proved highly successful and profitable, and provided a neutral ground for feuding datus to settle their differences.

Campaigns

Major military campaigns during Wood's governorship include:

- Wood's March Around Lake Lanao during the fall of 1903 was an abortive attempt to replicate Pershing's earlier March.

- In October and November 1903, Wood personally led the Provincial Army to put down the Hassan Uprising, which was led by the most powerful datu on the island of Jolo.

- In the spring of 1904, Wood destroyed or captured 130 cottas during the Second Battle of Taraca.

- Beginning in the spring of 1904 and continuing into the fall of 1905, American forces conducted a lengthy and massive manhunt for Datu Ali, the overlord of Cottabato Valley. Datu Ali had rebelled over Wood's anti-slavery policy. Engagements during this campaign include the Battle of Siranaya and the Battle of the Malalag River.

- The First Battle of Bud Dajo was fought from March 5 to March 7, 1906. An estimated 600 Muslims were killed, fighting a force of 800 Americans.[41][42][43][44]

The Incident in the Philippines written by Mark Twain condemned the American massacre at Bud Dajo.[45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62]

Governorship of Tasker H. Bliss (1906–1909)

On February 1, 1906, Major. Gen. Tasker H. Bliss replaced General Wood as the commander of the Department of Mindanao-Jolo, and replaced him as governor of Moro Province sometime after the First Battle of Bud Dajo. Bliss' tenure is regarded as a "peace era", and Bliss launched no punitive expeditions during his term in office. However, this superficial peace came at the price of tolerating a certain amount of lawlessness. Constabulary forces in pursuit of Moro fugitives often found themselves forced to abandon their chase after the fugitives took refuge at their home cottas. The constabulary forces were outnumbered, and a much larger (and disruptive) expedition would have been required to dislodge the fugitives from their hiding place. However, this period also demonstrated the success of new aggressive American tactics. According to Rear Admiral D.P. Mannix, who fought the Moros as a young lieutenant from 1907–1908, the Americans exploited Muslim taboos by wrapping dead Moros in pig's skin and "stuffing [their] mouth[s] with pork", thereby deterring the Moros from continuing with their suicide attacks.[63]

Governorship of John J. Pershing (1909–1913)

On November 11, 1909, Brigadier General John J. Pershing, the third and final military governor of Moro Province assumed his duties.

Reforms

Pershing enacted the following reforms during his tenure as governor:

- In order to extend rule of law into the interior, Pershing stationed the Philippine Scouts in small detachments throughout the interior. This reduced crime and promoted agriculture and trade, at the cost of reduced military efficiency and troop training. The benefits of this reform outweighed the costs.

- The legal system was streamlined. Previously, trials had started with at the Court of First Instance, which convened every 6 months, and appeals to the Supreme Court in Manila often took more than one year. Pershing expanded the jurisdiction of the local ward courts, which were presided over by the district governors and secretaries, to include most civil cases and all criminal cases except for capital offenses. The Court of First Instance became the court of last resort. This reform was popular with the Moros, since it was quick, simple, and resembled their traditional unification of executive and judicial powers.

- Pershing promised to donate government land for purposes of building Muslim houses of worship.

- Pershing recognized the practice of sacopy – indentured servitude in exchange for support and protection – as legitimate, but reaffirmed the government's opposition to involuntary slavery.

- Labor contract law reform of 1912. Defaults on contracts by workers or employers were no longer punishable unless there was intent to defraud or injure. Moros, unused to Western notions of work, were prone to absenteeism, which could lead to breach of contract suits.

- The economy of Moro Province continued to expand under Pershing. The three most important exports – hemp, copra, and lumber – increased 163% during his first three years, and Moros began to make bank deposits for the first time in their history.

- The Moro Exchange system was retained and was supplemented by Industrial Trading Stations. These stations operated in the interior, where merchants seldom went, and bought any non-perishable goods the Moros wished to sell. The stations also sold goods to the Moros at fair prices, preventing price gouging during famines.[64]

Tactics

Pershing wrote the following in his autobiography, about the juramentado:[65]

These juramentado were materially reduced in number by a practice the army had already adopted, one that the Mohammedans held in abhorrence. The bodies were publicly buried in the same grave with a dead pig. It was not pleasant to take such measures but the prospect of going to hell instead of heaven sometimes deterred the would-be assassins.[66][67][68]

Though Pershing inflicted this treatment upon captured juramentado,[69] regarding it as an unpleasant measure,[70][71] there is no proof that he used other similar tactics.[72]

Surrender of Arms

Law enforcement in the Moro Province was difficult. Outlaws would go to ground at their home cottas, requiring an entire troop of police or soldiers to arrest them. There was always the danger of a full-fledged battle breaking out during such an arrest, and this led to many known outlaws going unpunished. In 1911, Pershing resolved to disarm the Moros. Army Chief of Staff Leonard Wood (former Moro Province governor) disagreed with this plan, stating that the move was ill-timed and that the Moros would hide their best arms, turning in only their worst. Pershing waited until roads into the interior had been completed, so that government troops could protect disarmed Moros from holdouts. He conferred with the Datus, who mostly agreed that disarmament would be a good idea – provided that everybody disarmed.

Six weeks before putting his disarmament plan into action, Pershing informed Governor-General William Cameron Forbes, who agreed with the plan. Pershing did not consult or inform his commanding officer, Major. Gen. J. Franklin Bell. On September 8, 1911, Executive Order No. 24, which ordered the disarmament, was issued. The deadline for disarmament was December 1, 1911.

Resistance to disarmament was particularly fierce in the district of Jolo and led to the Second Battle of Bud Dajo (which, while involving roughly equivalent forces as the first battle, was far less bloody causing only 12 Moro casualties[73]), and the Battle of Bud Bagsak.

Transition to Civil Authority

By 1913, Pershing agreed that the Moro Province needed to transition to civil government. This was prompted by the Moro's personalistic approach to government, which was based on personal ties rather than a respect for an abstract office. To the Moros, a change of administration meant not just a change in leadership but a change in regime, and was a traumatic experience. Rotation within the military meant that each military governor could serve only for a limited time. Civil governors were needed in order to provide for a lengthy tenure in office. Until 1911, every district governor and secretary had been a military officer. By November 1913, only one officer still held a civil office – Pershing himself. In December 1913, Pershing was replaced as governor of Moro Province by a civilian, Frank Carpenter.

Casualties

During the Moro Rebellion, the Americans suffered clear cut losses, amounting to 130 killed and 323 wounded. Another 500 or so died of disease.[74] The Philippine Scouts who augmented American forces during the campaign suffered 116 killed and 189 wounded. The Philippine Constabulary suffered heavily as well with more than 1,500 losses sustained of which half were fatalities.

On the Moro side, casualties were high as surrender was uncommon when Moros were engaged in combat.[75]

-

Three Moro rebels being hanged in Jolo, 21 July 1911

-

Three Moro rebels hanged in Jolo, 21 July 1911

Further Rebellions

Until World War II, rebellions by the Moros against American rule persisted long after 1914, and then the Moros then proceeded to fight against the Japanese invaders. Violence between the occupying forces and Moro Maranao broke out from 1921-1928. It was written that twenty five years of guerilla fighting have not solved the Moro Problem. in The New Republic in 1931.[76] Troops with weapons had to guard the American school superintendent in certain Lanao districts.[77][78][79][80][81]

Dates, leaders, and locations of armed insurrections: 1927, Datu Tahil, in Sulu, in 1923-1924, Datu Santiago, in Cotabato's Parang region, in 1923, Maranao insurrection.[82] A ten-year jail term was handed out to Dato Tahil after the battle on January 31, 1927 between him and government forces at his cotta, over weapons control and taxes, a certain Imam Mahdi started a 1924 revolt, in Palawan, a cleric led a revolt in June 1923, while Moros angered by anti-truancy laws and taxes in Palawan rose up in May 1923, Dato Santiago led an uprising in Cotabato in 1923 and anti-truancy laws and taxes led to Maranaos revolting in 1923, and anti-truancy laws in Lanao caused violence in 1921.[83] Cotabato, Parang, was the scene of an uprising in 1923 by Datu Santiago and uprisings against the Americans broke out in Lanao and Sulu.[84] The head tax in 1923 by Leonard Wood, the Governor, led to the Parang Cotabato insurrection led by Datu Santiago.[85] The Mroos said Once our religion is no more, our lives are no more. Datu Santiago's 1923-1924 Parang Cotabato insurrection lasted for one year, which occurred after the death of 55 rebels when anti-truancy laws and taxes led to a 1923 uprising in Tugaya, Lanao, among Moro Maranao.[86] Mandatory schooling was the cause of the uprising in Tugaya, Lanao in 1923. In Lanao the people torched 47 schools throughout 1926-1927.[87][88] Sulu's pearl beds were seen as its own people's patrimony and when they were infringed upon, Jikiri rose up in violence. It was believed that Christianity was being taught in public schools run by Americans so when it became mandatory for children to attend them, an uprising broke out among the Moros of Tugaya in Lanao in 1923.[89] The issue of schooling and taxes led to multiple uprisings by Moro Muslims in 1923, 1924, and 1927.[90][91] The Christian staffed American run schools which were opened were largely spurned and rejected by the Muslims.[92] One of the educational superintendents in the region was J Scott McCormick.[93] There were Muslim resistance against the Americans in 1924 in Pandak and in 1923 in Ganassi and Tugaya and in 1921.[94][95] The 1936-1941 war in the kutah was the most sanguinary violence, coming after the 1927 Santiago war, 1917 war in Ambang, 1913 Alamada war, 1903-1904 Ali war, all in Cotabato by Maguindanaos, and the 19120 Untong war, the 1919 Sanda War, the 1913 Bud Bagsak war, the 1906 Bud Dajo war, the 1904-1905 Pala war, the 1904 Usap war, the 1903-1904 Hassan war, the 1903 Tagbili war, the 1901 Libut war in Sulu by the Tausogs.[96] Santiago led a group of Moros in 1923, autumn, to end the lives of 14 occupiers including a teacher and a lieutenant of the constabulary.[97] In 1927 in Kitibud Datu Mampuroc revolted, while involuntary labor and mistreatment by education officials led Datu Santiago to revolt in 1923.[98] Due to financial and administrative issues, an anti-government uprising was launched by Princess Tarhata's husband who survived Bud Bagsak in 1913, Datu Tahil in Sulu. The Mampuroc led uprising in Norther Cotabato's Mt. Kitibud involved Muslims in the ranks of the Alangkat Movement which fought against soldiers sent by the government due to the Manobo people forced to pay 20,000 pesos.[99][100][101]

Another war broke out between the Philippine Commonwealth in 1936-1941 with cotta at Lanao against the Moro Muslims.[102][103][104] The uprising was due to the swamping of Moro land in Mindanao with Filipino migrants by the government.[105][106] The "Military Training Act" was also a trigger for the uprising. Killings were carried out by Moro juramentados in Jolo up to the days immediately prior to World War II.[107] The invading Japanese were then attacked by the Moro Muslims.[108][109]

The 1941 book "Cross Winds of Empire" noted the uprising based around the cottas by the Moros was happening as it was written.[110]

An insurrection over revocation of Double jeopardy and implementation of conscription broke out in 1937 among the Talipao Tausugs in Sulu.[111] Anti-truancy measures against parents which included fines and arrest by the constabulary resulted in a major insurrection.[112]

Moro rebels have been engaged in an ongoing insurgency against the Philippine government since 1969 Moro Conflict

More recently, up to 600 Americans were engaged in combat duties advising Philippine forces against the Communist insurgency and various militant Islamist groups Operation Enduring Freedom – Philippines. Operations ended in June 2014.

Juramentados and stopping power

In the Moro Rebellion, Moro Muslim Juramentados in suicide attacks continued to charge against American soldiers even after being shot. Panglima Hassan in the Hassan uprising was shot dozens of times before he went down. As a result, Americans elected to phase out revolvers with .38 caliber ammunition in favor of Colt .45 ACP pistols to continue their fight against the Moros.[113] Arrows, bayonets, guns, and Kris were used in often suicidal attacks by the Moros during their war with the Americans. Suicide attacks became more popular among Moros due to the overwhelming firepower of the Americans in conventional battles. Moro women took part in the resistance at the Battle of Bud Dajo against the American General Lenard Wood in 1906.[114] Barbed wire proved to be of no impediment since Moro Juramentado warriors managed to surge directly through it even as it ripped at their flesh and even as they were shot repeatedly with bullets. The Moros used barongs to inflict injuries upon American soldiers.[115] Moros under Jikiri managed to survive in a cave under machine gun fire and Colt gunfire. [116] Kris and Kampilan were used by Moros in fierce close quarter combat against the Americans.[117] Muskets were also used by the Moro.[118] The Moro employed bayonets at close range when shooting was not possible according to the American journal The Field Artillery Journal, Volume 32.[119] Americans were even charged at by Moros using spears.[116] Moros fought to the death against Americans armed with rifles and artillery while they themselves used only Kris at the crater battle.[120][121]

Novels have been written about Juramentados deliberately impaling themselves on their bayonets in order to reach and kill American soldiers.[122]

Popular culture

Pershing reportedly ordered Moro juramentados to be buried with pigs because they allegedly believed that they would not go to heaven because of it.[66]

Vic Hurley wrote the screenplay for The Real Glory in 1937, which became a Hollywood film in 1939. It was based on a 1937 novel of the same name by Charles L. Clifford, a pen name of Vic Hurley's. There is a scene in the movie where Gary Cooper as Dr. Bill Canavan drapes a captured Muslim in a pigskin. He proclaims that all slain Muslim rebels will be buried in pig skins to prevent their entry into paradise. The Hollywood film served as propaganda for the Americans, portraying the American forces as brave defenders of the local population being terrorised by the Moros.[123][124]

Vic Hurley's history of the Moros, "Swish of the Kris The Story of the Moros" tells the story of Col. Alexander Rodgers using pigs to subdue the Moros in the Philippines. Hurley wrote that Col. Rodgers was known as "the Pig" to the Moros.[125] And another Hurley book "The Jungle Patrol, the story of the Philippine Constabulary" also relates the story of pigs being used against them. The story of the pigs is also found in Jim Lacey's biography of Pershing; Lacey wrote that Pershing himself told the story in his unpublished autobiography.[66]

See also

Notes

- ^ Anthony Joes (18 August 2006). Resisting Rebellion: The History and Politics of Counterinsurgency. University Press of Kentucky. p. 164. ISBN 0-8131-7199-7.

- ^ James R. Arnold (26 July 2011). The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-1-60819-365-3.

- ^ "MINDANAO, SULU and ARMM Unsung Heroes".

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Invalid Pensions (1945). Hearings. p. 40.

- ^ Arnold, J.R., 2011, The Moro War, New York: Bloomsbury Press, ISBN 9781608190249

- ^ Banlaoi 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Banlaoi 2005 Archived 2016-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, p. 68.

- ^ Dphrepaulezz, Omar H. (5 June 2013). "The Right Sort of White Men": General Leonard Wood and the U.S. Army in the Southern Philippines, 1898–1906 (Doctoral Dissertations). p. 16. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Kho, Madge. "The Bates Treaty". PhilippineUpdate.com. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Hurley, Victor (1936). "17. Mindinao and Sulu in 1898". Swish of the Kris. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Archived from the original on 2008-07-12. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Guerrero, Rustico O (10 April 2002). MASTER OF MILITARY STUDIES PHILIPPINE TERRORISM AND INSURGENCY: WHAT TO DO ABOUT THE ABU SAYYAF GROUP (PDF) (Thesis). United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College Marine Corps University. p. 6.

- ^ Swain, Richard (October 2010). "Case Study: Operation Enduring Freedom Philippines" (PDF) (CASE STUDY). U.S. Army Counterinsurgency Center. p. 8.

- ^ Mustafa Akyol (18 July 2011). Islam without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty. W. W. Norton. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-393-07086-6.

- ^ Idris Bal (2004). Turkish Foreign Policy in Post Cold War Era. Universal-Publishers. pp. 405–. ISBN 978-1-58112-423-1.

- ^ Kemal H. Karpat (2001). The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State. Oxford University Press. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-0-19-513618-0.

- ^ Moshe Yegar (1 January 2002). Between Integration and Secession: The Muslim Communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar. Lexington Books. pp. 397–. ISBN 978-0-7391-0356-2.

- ^ George Hubbard Blakeslee; Granville Stanley Hall; Harry Elmer Barnes (1915). The Journal of International Relations. Clark University. pp. 358–.

- ^ The Journal of Race Development. Clark University. 1915. pp. 358–.

- ^ Political Science Quarterly. Academy of Political Science. 1904. pp. 22–.

- ^ Kho, Madge. "The Bates Treaty". Philippine Update. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ http://dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA406868 Luga p. 22.

- ^ "A Brief History of America and the Moros 1899-1920".

- ^ "The Bates Mission 1899".

- ^ "Causes of Conflict between Christians and Muslims in the Philippines".

- ^ Times, Special To The New York (15 March 1904). "AMERICA ABROGATES TREATY WITH MOROS; Rights Conferred by the Bates Agreement Forfeited. NATIVES FIGHT FOR SLAVERY United States Troops Defeat Them and Capture Cannon and Ammunition" – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Ibrahim Alfian (Teuku.) (1987). Perang di Jalan Allah: Perang Aceh, 1873-1912. Pustaka Sinar Harapan. p. 130.

- ^ Benjamin Runkle (2 August 2011). Wanted Dead or Alive: Manhunts from Geronimo to Bin Laden. St. Martin's Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-230-33891-3.

- ^ Simmons, Edwin H. (March 2003). "Civilize 'Em with a Krag". The United States Marines: A History. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-55750-868-3.

- ^ Hunt, Geoffrey (2006). "Civilize 'Em with a Krag". Colorado's Volunteer Infantry in the Philippine Wars, 1898–1899. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8263-3700-9.

- ^ "President Theodore Roosevelt's Proclamation Formally Ending the Philippine 'Insurrection' and Granting of Pardon and Amnesty". MSC Institute of Technology. July 4, 1902. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ a b c Hurley, Vic (1936). "18. The Formation of the Moro Province". Swish of the Kris. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Archived from the original on 2008-07-12. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Hagedorn 1931, p. 14, Volume 2

- ^ Bacevich, Andrew J. (March 12, 2006). "What happened at Bud Dajo". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Birtle 1998, p. 164

- ^ "Bearers of the Sword Radical Islam, Philippines Insurgency, and Regional Stability". 21 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-06-21.

- ^ Walsh, Thomas P. (1 January 2013). "Tin Pan Alley and the Philippines: American Songs of War and Love, 1898-1946 : a Resource Guide". Rowman & Littlefield – via Google Books.

- ^ "If a Lady's Wearin' Pantaloons sheet music for Treble Clef Instrument - 8notes.com".

- ^ "abc - If a Lady's Wearin' Pantaloons - back.numachi.com:8000/dtrad/abc_dtrad.tar.gz/abc_dtrad/LADYPANT/0000".

- ^ Runyon, Damon (1 January 1911). "The Tents of Trouble". Desmond FitzGerald, Incorporated – via Google Books.

- ^ Spiegel, Max. "IF A LADY'S WEARIN' PANTALOONS".

- ^ Benjamin R. Beede (21 August 2013). The War of 1898 and U.S. Interventions, 1898T1934: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-136-74691-8.

By the end of the operation the estimated 600 Muslims in Bud Daju were wiped out.

- ^ John J. Pershing (25 June 2013). My Life before the World War, 1860--1917: A Memoir. University Press of Kentucky. p. 386. ISBN 0-8131-4198-2.

These are merely estimates, because no firm number of Moro dead was ever established.

- ^ Dphrepaulezz, Omar H. (5-6-2013). "The Right Sort of White Men": General Leonard Wood and the U.S. Army in the Southern Philippines, 1898-1906 (Doctoral Dissertations). p. 8. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

{{cite thesis}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Robert A. Fulton (2011). Honor for the Flag: The Battle of Bud Dajo - 1906 & the Moro Massacre. Robert Fulton. ISBN 978-0-9795173-2-7.

- ^ Mark Twain (17 November 2013). Delphi Complete Works of Mark Twain (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 3819. ISBN 978-1-908909-12-1.

- ^ Mark Twain (17 November 2013). Delphi Complete Works of Mark Twain (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. pp. 3777–. ISBN 978-1-908909-12-1.

- ^ Howard Zinn; Anthony Arnove (4 January 2011). Voices of a People's History of the United States. Seven Stories Press. pp. 248–. ISBN 978-1-58322-947-7.

- ^ James R. Arnold; Roberta Wiener (12 November 2015). Understanding U.S. Military Conflicts through Primary Sources [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-1-61069-934-1.

- ^ Documents in United States History: Since Reconstruction. Pearson/Prentice Hall. January 2004. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-13-150256-7.

- ^ Bruce Borland (January 1997). America Through the Eyes of Its People: Primary Sources in American History. Longman. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-673-97738-0.

- ^ Roger J. Bresnahan (December 1981). In time of hesitation: American anti-imperialists and the Philippine-American War. New Day Publishers. p. 67.

- ^ Burton L. Cooper (1967). 12 Prose Writers: Francis Bacon, Jonathan Swift, William Hazlitt, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Matthew Arnold, Mark Twain, E.M. Forster, Aldous Huxley, James Thurber, George Orwell, Mary McCarthy [and] James Baldwin. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 161.

- ^ Mark Twain (16 January 1979). A pen warmed-up in hell: Mark Twain in protest. Harper & Row. p. 97.

- ^ Mark Twain (August 1973). Mark Twain and the three R's: race, religion, revolution--and related matters. Bobbs-Merrill. p. 20.

- ^ Mark Twain; Albert Bigelow Paine (1925). The Writings of Mark Twain. Gabriel Wells. p. 187.

- ^ "America Past and Present Online - Mark Twain, "Incident in the Philippines" (1924)".

- ^ ""Comments on the Moro Massacre" - Samuel Clemens (March 12, 1906)".

- ^ "Comments on the Moro Massacre by Mark Twain".

- ^ "Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1 : an electronic text".

- ^ "Novelist Kurt Vonnegut Dies at 84".

- ^ "Doc 5_Moro Massacre - Document 5 At the end of the nineteenth century, the".

- ^ "Comments on the Moro Massacre by Mark Twain". Archived from the original on 2005-12-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mannix, Daniel P., IV (1983). The Old Navy. MacMillan Publishing Company. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-02-579470-2.

...the custom of wrapping the dead man in a pig's skin and stuffing his mouth with pork. As the pig was an unclean animal, this was considered unspeakable defilement.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) A compilation of the diary of Rear Admiral D.P. Mannix III. - ^ Miller, Daniel G. "AMERICAN MILITARY STRATEGY DURING" (PDF). Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Pershing, John. My Life Before the World War, 1860--1917: A Memoir, p. 284 (University Press of Kentucky, 2013).

- ^ a b c Jim Lacey (10 June 2008). Pershing (Great Generals). PalgraveMacmillan. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-230-60383-7.

- ^ Jenna Johnson & Jose A. DelReal (February 20, 2017). "Trump tells story about killing terrorists with bullets dipped in pigs' blood, though there's no proof of it". Washington Post.

- ^ Pappas, Alex (August 17, 2017). "Trump cites tale of Gen. Pershing'g pigs' blood bullets that historians dismiss". Fox News Politics. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

'It was not pleasant to have to take such measures, but the prospect of going to hell instead of heaven sometimes deterred the would-be assassins.' [citing Pershing, My Life before the World War, 1860–1917, section titled Problems with Moro Outlaws and Juramentado]

- ^ Smythe, Donald. Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing, p. 162 (Scribner, 1973): "To combat the jurementado, Pershing tried burying him when caught with a pig, thinking that this was equivalent to burying the Moro in hell, for pigs were impure animals to a Moslem."

- ^ Pershing, John. My Life Before the World War, 1860--1917: A Memoir, p. 284 (University Press of Kentucky, 2013).

- ^ Lacey, Jim (10 June 2008). Pershing (Great Generals). PalgraveMacmillan. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-230-60383-7.

- ^ Jenna Johnson & Jose A. DelReal (February 20, 2017). "Trump tells story about killing terrorists with bullets dipped in pigs' blood, though there's no proof of it". Washington Post.

- ^ Byler 2005

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (20 May 2009). Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, The: A Political, Social, and Military History: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 415–417. ISBN 978-1-85109-952-8.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (29 October 2013). Encyclopedia of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency: A New Era of Modern Warfare. ABC-CLIO. p. 371. ISBN 978-1-61069-280-9.

- ^ J. Milligan (31 July 2005). Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. Springer. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-1-4039-8157-8.

- ^ B. R. Rodil (2003). A Story of Mindanao and Sulu in Question and Answer. Mincode. p. 84. ISBN 978-971-92895-0-0.

- ^ Archibald Cary Coolidge; Hamilton Fish Armstrong (1927). Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. p. 642.

- ^ "City of Waterfalls-Iligan City: 42. To what extent was popular colonial education successful?".

- ^ https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/20411/1/M.A.CB5.H3_3461_r.pdf

- ^ http://www.palgraveconnect.com/pc/doifinder/view/10.1057/9781403981578

- ^ The Diliman Review. College of Arts and Sciences of the University of the Philippines. 1982. p. 25.

- ^ Moshe Yegar (2002). Between Integration and Secession: The Muslim Communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar. Lexington Books. pp. 227–. ISBN 978-0-7391-0356-2.

- ^ Mindanao Journal. University Research Center, Mindanao State University. 1978. p. 143.

- ^ Alfred W. McCoy (2000). Lives at the Margin: Biography of Filipinos Obscure, Ordinary, and Heroic. ADMU Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-971-550-355-6.

- ^ Silliman Journal. Silliman University. 1978. p. 115.

- ^ Ahmad Mohammad H. Hassoubah (1983). Teaching Arabic as a Second Language in the Southern Philippines. University Research Center, Mindanao State University. p. 8. ISBN 978-971-11-1020-8.

- ^ Papers in Philippine Linguistics. University Research Center, Mindanao State University. 1981. p. 14.

- ^ Salah Jubair (1999). Bangsamoro, a Nation Under Endless Tyranny. IQ Marin. p. 85.

- ^ Moshe Yegar (2002). Between Integration and Secession: The Muslim Communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar. Lexington Books. pp. 227–. ISBN 978-0-7391-0356-2.

- ^ Salah Jubair (1999). Bangsamoro, a Nation Under Endless Tyranny. IQ Marin.

- ^ J. Milligan (31 July 2005). Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. Springer. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-4039-8157-8.

- ^ David Shavit (1990). The United States in Asia: A Historical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 319–. ISBN 978-0-313-26788-8.

- ^ Kadir Che Man (W.) (1990). Muslim Separatism: The Moros of Southern Philippines and the Malays of Southern Thailand. Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-588924-6.

- ^ Norodin Alonto Lucman (2000). Moro Archives: A History of Armed Conflicts in Mindanao and East Asia. FLC Press. p. 286.

- ^ Philippine Law Journal. University of the Philippines, College of Law. 1979. p. 513.

- ^ US Congress Committee on Territories and Insular Affairs (1930). Independence for the Philippine Islands: Hearings before the Committee on territories and insular affiars. U. S. Govt. print. off. p. 632.

- ^ Asian Studies. Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, University of the Philippines System. 1973. p. 119.

- ^ Asian Studies. Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, University of the Philippines System. 1973. p. 119.

- ^ Samuel K. Tan (1982). Selected Essays on the Filipino Muslims. University Research Center, Mindanao State University. p. 67. ISBN 978-971-0300-16-7.

- ^ Samuel K. Tan (1982). Selected Essays on the Filipino Muslims. University Research Center, Mindanao State University. p. 68. ISBN 978-971-0300-16-7.

- ^ Moshe Yegar (2002). Between Integration and Secession: The Muslim Communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar. Lexington Books. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-7391-0356-2.

- ^ Philippine Law Journal. University of the Philippines, College of Law. 1979. p. 513.

- ^ Nasser A. Marohomsalic (2001). Aristocrats of the Malay Race: A Historic of the Bangsa Moro in the Philippines. N.A. Marohomsalic. p. 145.

- ^ Rudis, Josh. "Igorot and moro National Reemergence: The Fabricated Philippine State".

- ^ "Igorot and moro National Reemergence: The Fabricated Philippine State". 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03.

- ^ "TERRITORIES: Terror in Jolo". 1 December 1941 – via content.time.com.

- ^ J. Milligan (31 July 2005). Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. Springer. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-1-4039-8157-8.

- ^ Kemp Tolley (1973). Cruise of the Lanikai: Incitement to War. Naval Institute Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-1-55750-406-7.

- ^ Woodbern Edwin Remington (1941). Cross Winds of Empire. John Day. p. 118.

- ^ Nasser A. Marohomsalic (2001). Aristocrats of the Malay Race: A Historic of the Bangsa Moro in the Philippines. N.A. Marohomsalic. p. 145.

- ^ Nasser A. Marohomsalic (2001). Aristocrats of the Malay Race: A Historic of the Bangsa Moro in the Philippines. N.A. Marohomsalic. p. 145.

- ^ DK (2 October 2006). Weapon: A Visual History of Arms and Armor. DK Publishing. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-0-7566-4219-8.

- ^ Shaʾul Shai. The Shahids: Islam and Suicide Attacks. Transaction Publishers. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-1-4128-3892-4.

- ^ Vic Hurley (14 June 2011). Jungle Patrol, the Story of the Philippine Constabulary (1901-1936). Cerberus Books. pp. 319–. ISBN 978-0-9834756-2-0.

- ^ a b James R. Arnold (26 July 2011). The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913. Bloomsbury USA. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-1-60819-024-9.

- ^ Jim Lacey (10 June 2008). Pershing: A Biography. St. Martin's Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-230-61270-9.

- ^ Vic Hurley; Christopher L. Harris (1 October 2010). Swish of the Kris, the Story of the Moros, Authorized and Enhanced Edition. Cerberus Books. pp. 210–. ISBN 978-0-615-38242-5.

- ^ The Field Artillery Journal. United States Field Artillery Association. 1942. p. 799.

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Invalid Pensions (1945). Hearings. p. 38.

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Invalid Pensions; United States. Congress. House. Committee on Veterans' Affairs (1945). Philippine Uprisings and Campaigns After July 4, 1902, and Prior to January 1, 1914: Hearings Before the Committee on Invalid Pensions, House of Representatives, Seventy-ninth Congress, First Session, on H. R. 128 and H. R. 3251, Bills Extending Pension Benefits to Veterans who Served After July 4, 1902, and Prior to January 1, 1914, in the Armed Forces Engaged in Actual Hostilities in Certan Specified Areas on the Philippine Islands, and to Their Dependents. March 20 and 22, 1945. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 37–38.

- ^ Teodoro M. Locsin (1994). Trial & error. Free Press, Inc. p. 238. ISBN 978-971-91399-0-4.

- ^ M. Paul Holsinger (January 1999). War and American Popular Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-313-29908-7.

- ^ Ignacio Farmer (21 February 2015). "Western Movies Full Length The Real Glory War Drama 1939" – via YouTube.

- ^ Swish of the Kris p. 223, Cerebus books ISBN 978-061-538-242-5

Bibliography

- Arnold, James R. (2011). The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 9781608190249. OCLC 664519655.

- Birtle, Andrew J. (1998). U.S. Army Counterinsurgency & Contingency Operations Doctrine: 1860–1941. Diane Pub Co. ISBN 0-7881-7327-8.

- Byler, Charles (May–June 2005). "Pacifying the Moros: American Military Government in the Southern Philippines, 1899–1913" (PDF). Military Review: 41–45. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- Hagedorn, Hermann (1931). Leonard Wood: A Biography. Vol. 2. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Hurley, Vic (1936). Swish of the Kris. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Archived from the original on 2008-07-12. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- Kho, Madge. "The Bates Treaty". PhilippineUpdate.com. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- Kolb, Richard K. (May 2002). "'Like a mad tiger': fighting Islamic warriors in the Philippines 100 years ago". VFW Magazine.[dead link]

- Lane, Jack C. (1978). Armed Progressive: General Leonard Wood. San Rafael, Calif.: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-009-0. OCLC 3415456.

- Millett, Alan R. (1975). The General: Robert L. Bullard and Officership in the United States Army 1881–1925. Westport, Conn.: Greenward Press. ISBN 0-8371-7957-2. OCLC 1530541.

- Palmer, Frederick (1970) [1934]. Bliss, Peacemaker: The Life and Letters of General Tasker Howard Bliss. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 0-8369-5535-8. OCLC 101067.

- Smythe, Donald (1973). Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing. New York: Charles Scribener's Sons. ISBN 0-684-12933-7. OCLC 604954.

- Vandiver, Frank E. (1977). Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing. Vol. 1. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-024-0. OCLC 2645933.

Further reading

- Linn, Brian McAllister (1999). Guardians of Empire: The U.S. Army and the Pacific, 1902–1940. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4815-9.

External links

- Articles with neologism issues from November 2016

- Moro Rebellion

- History of the Philippines (1898–1946)

- Rebellions in the Philippines

- History of Basilan

- History of Lanao del Sur

- History of Maguindanao

- History of Sulu

- History of Tawi-Tawi

- Conflicts in 1899

- 1900s conflicts

- 1910s conflicts

- 1899 in the Philippines

- 1900s in the Philippines

- 1910s in the Philippines

- Moro

- Rebellions in Asia