Adivasi

Adivasi is the collective term for the indigenous peoples of mainland South Asia.[1][2][3] Adivasi make up 8.6% of India's population, or 104 million people, according to the 2011 census, and a large percentage of the Nepalese population.[4][5][6] They comprise a substantial indigenous minority of the population of India and Nepal. The same term Adivasi is used for the ethnic minorities of Bangladesh and the native Tharu people of Nepal.[7][8] The word is also used in the same sense in Nepal, as is another word, janajati (Template:Lang-ne; janajāti), although the political context differed historically under the Shah and Rana dynasties.

Adivasi societies are particularly prominent in Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, West Bengal and some north-eastern states, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Many smaller tribal groups are quite sensitive to ecological degradation caused by modernisation. Both commercial forestry and intensive agriculture have proved destructive to the forests that had endured swidden agriculture for many centuries.[9] Adivasis in central part of India have been victims of the Salwa Judum campaign by the Government against the Naxalite insurgency.[10][better source needed][11][12]

Connotations of the word adivāsi

Although terms such as atavika, vanavāsi ("forest dwellers"), or girijan ("mountain people")[13] are also used for the tribes of India, adivāsi carries the specific meaning of being the original and autochthonous inhabitants of a given region. It is a modern Sanskrit word specifically coined for that purpose in the 1930s,[14] from ādi 'beginning, origin' and vāsin 'dweller' (itself from vas 'to dwell'), thus literally meaning ‘original inhabitant’.[15] Over time, unlike the terms "aborigines" or "tribes", the word "adivasi" has developed a connotation of past autonomy disrupted during the British colonial period in India and not yet having been restored.[16] i

In India, opposition to usage of the term is varied. Critics argue that the "original inhabitant" contention is based on the fact that they have no land and are therefore asking for a land reform. The adivasis argue that they have been oppressed by the "superior group" and that they require and demand a reward, more specifically land reform.[17]

In Northeast India, the term adivāsi applies only to the Tea-tribes imported from Central India during colonial times. All tribal groups refer collectively to themselves by using the English word "tribes".

Geographical overview

A substantial list of Scheduled Tribes in India are recognised as tribal under the Constitution of India. Tribal people constitute 8.6% of the nation's total population, over 104 million people according to the 2011 census. One concentration lives in a belt along the Himalayas stretching through Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand in the west, to Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland in the northeast. In the northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland, more than 90% of the population is tribal. However, in the remaining northeast states of Assam, Manipur, Sikkim, and Tripura, tribal peoples form between 20 and 30% of the population. Other tribal peoples, including the Santals, live in Jharkhand and West Bengal. Central Indian states have the country's largest tribes, and, taken as a whole, roughly 75% of the total tribal population live there, although the tribal population there accounts for only around 10% of the region's total population.

Smaller numbers of tribal people are found in Odisha in eastern India; Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala in southern India; in western India in Gujarat and Rajasthan, and in the union territories of Lakshadweep and the Andaman Islands and Nicobar Islands. About one percent of the populations of Kerala and Tamil Nadu are tribal, whereas about six percent in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka are members of tribes.

Scheduled tribes

The term 'Scheduled Tribes'(ST's) first appeared in the Constitution of India. Article 366 (25) defined scheduled tribes as "such tribes or tribal communities or parts of or groups within such tribes or tribal communities as are deemed under Article 342 to be Scheduled Tribes for the purposes of this constitution". Article 342, which is reproduced below, prescribes procedure to be followed in the matter of specification of scheduled tribes.

Constitutional Safeguards for STs

Educational & Cultural Safeguards

Art. 15(4) - Special provisions for advancement of other backward classes (which includes STs);

Art. 29 - Protection of Interests of Minorities (which includes STs);

Art. 46 - The State shall promote, with special care, the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and in particular, of the Scheduled Castes, and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation,

Art. 350 - Right to conserve distinct Language, Script or Culture;

Art. 350 - Instruction in Mother Tongue.

Social Safeguard

Art. 23 - Prohibition of traffic in human beings and beggar and other similar form of forced labour

Art. 24 - Forbidding Child Labour.

Economic Safeguards

Art.244 - Clause(1) Provisions of Fifth Schedule shall apply to the administration & control of the Scheduled Areas and Scheduled Tribes in any State other than the states of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Tripura which are covered under Sixth Schedule, under Clause (2) of this Article.

Art. 275 - Grants in-Aid to specified States (STs &SAs) covered under Fifth and Sixth Schedules of the Constitution.

Political Safeguards

Art.164 (1) - Provides for Tribal Affairs Ministers in Bihar, MP and Orissa

Art. 330 - Reservation of seats for STs in Lok Sabha

Art. 337 - Reservation of seats for STs in State Legislatures

Art. 334 - 10 years period for reservation (Amended several times to extend the period

Art. 243 - Reservation of seats in Panchayats

Art. 371 - Special provisions in respect of NE States and Sikkim

Safeguards under Various laws

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act,1989 and the Rules 1995 framed there under. Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act 1976 (in respect of Scheduled Tribes);

The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act1986;

States Acts & Regulations concerning alienation & restoration of land belonging to STs; Forest Conservation Act 1980;

Panchayatiraj (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act 1996;

Minimum Wages Act 1948.

Particularly vulnerable tribal groups

The Scheduled Tribe groups who were identified as more isolated from the wider community and who maintain a distinctive cultural identity have been categorised as 'Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups' (PTGs) previously known as Primitive Tribal Groups) by the Government at the Centre. So far seventy-five tribal communities have been identified as 'particularly vulnerable tribal groups' in different States of India. These hunting, food-gathering, and some agricultural communities, have been identified as less acculturated tribes among the tribal population groups and in need of special programmes for their sustainable development. The tribes are awakening and demanding their rights for special reservation quota for them.[18]

History

Ancient India

Although considered uncivilised and primitive,[19] adivasis were usually not held to be intrinsically impure by surrounding (usually Dravidian or Aryan) casted Hindu populations, unlike Dalits, who were.[a][20] Thus, the adivasi origins of Valmiki, who composed the Ramayana, were acknowledged,[21] as were the origins of adivasi tribes such as the Garasia and Bhilala, which descended from mixed Rajput and Bhil marriages.[22][23] Unlike the subjugation of the Dalits, the adivasis often enjoyed autonomy and, depending on region, evolved mixed hunter-gatherer and farming economies, controlling their lands as a joint patrimony of the tribe.[19][24][25] In some areas, securing adivasi approval and support was considered crucial by local rulers,[14][26] and larger adivasi groups were able to sustain their own kingdoms in central India.[14] The Gond Rajas of Garha-Mandla and Chanda are examples of an adivasi aristocracy that ruled in this region, and were "not only the hereditary leaders of their Gond subjects, but also held sway over substantial communities of non-tribals who recognized them as their feudal lords."[24][27]

Medieval India

The historiography of relationships between the Advasis and the rest of the Indian society is patchy. There are references to alliances between Ahom Kings of Brahmaputra valley and the hill Nagas [28] This relative autonomy and collective ownership of adivasi land by adivasis was severely disrupted by the advent of the Mughals in the early 16th century. Rebellions against Mughal authority include the Bhil Rebellion of 1632 and the Bhil-Gond Insurrection of 1643[29] which were both pacified by Mughal soldiers.

British period

From the very early days of British rule, the tribesmen resented the British encroachments upon their tribal system. They were found resisting or supporting their brethren of Tamar and Jhalda in rebellion. Nor did their raja welcome the British administrative innovations.[30] Beginning in the 18th century, the British added to the consolidation of feudalism in India, first under the Jagirdari system and then under the zamindari system.[31] Beginning with the Permanent Settlement imposed by the British in Bengal and Bihar, which later became the template for a deepening of feudalism throughout India, the older social and economic system in the country began to alter radically.[32][33] Land, both forest areas belonging to adivasis and settled farmland belonging to non-adivasi peasants, was rapidly made the legal property of British-designated zamindars (landlords), who in turn moved to extract the maximum economic benefit possible from their newfound property and subjects.[34] Adivasi lands sometimes experienced an influx of non-local settlers, often brought from far away (as in the case of Muslims and Sikhs brought to Kol territory)[35] by the zamindars to better exploit local land, forest and labour.[31][32] Deprived of the forests and resources they traditionally depended on and sometimes coerced to pay taxes, many adivasis were forced to borrow at usurious rates from moneylenders, often the zamindars themselves.[36][37] When they were unable to pay, that forced them to become bonded labourers for the zamindars.[38] Often, far from paying off the principal of their debt, they were unable even to offset the compounding interest, and this was made the justification for their children working for the zamindar after the death of the initial borrower.[38] In the case of the Andamanese adivasis, long isolated from the outside world in autonomous societies, mere contact with outsiders was often sufficient to set off deadly epidemics in tribal populations,[39] and it is alleged that some sections of the British government directly attempted to destroy some tribes.[40]

Land dispossession and subjugation by British and zamindar interests resulted in a number of adivasi revolts in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, such as the Santal hul (or Santhal rebellion) of 1855–56.[41] Although these were suppressed ruthlessly by the governing British authority (the East India Company prior to 1858, and the British government after 1858), partial restoration of privileges to adivasi elites (e.g. to Mankis, the leaders of Munda tribes) and some leniency in tax burdens resulted in relative calm, despite continuing and widespread dispossession, from the late nineteenth century onwards.[35][42] The economic deprivation, in some cases, triggered internal adivasi migrations within India that would continue for another century, including as labour for the emerging tea plantations in Assam.[43]

Participation in Indian independence movement

There were tribal reform and rebellion movements during the period of the British Empire, some of which also participated in the Indian independence movement or attacked mission posts.[44] There were several Adivasis in the Indian independence movement including Dharindhar Bhyuan, Laxman Naik, Jantya Bhil, Bangaru Devi and Rehma Vasave.

List of rebellions

During the period of British rule, India saw the rebellions of several backward castes, mainly tribal peoples that revolted against British rule. These were:[citation needed]

- Great Kuki Invasion of 1860s

- Halba rebellion (1774–79)

- Chakma rebellion (1776–1787)[45]

- Chuar rebellion in Bengal (1795–1800)[46]

- Bhopalpatnam Struggle (1795)

- Khurda Rebellion in Odisha (1817)[47]

- Bhil rebellion (1822–1857)[48]

- Ho-Munda Revolt(1816-1837)[49]

- Paralkot rebellion (1825)

- Khond rebellion (1836)

- Tarapur rebellion (1842–54)

- Maria rebellion (1842–63)

- First Freedom Struggle By Sidu Murmu and Kanu Murmu (1856–57)

- Bhil rebellion, begun by Tantya Tope in Banswara (1858)[50]

- Koi revolt (1859)

- Gond rebellion, begun by Ramji Gond in Adilabad (1860)[51]

- Muria rebellion (1876)

- Rani rebellion (1878–82)

- Bhumkal (1910)

- The Kuki Uprising (1917–1919) in Manipur

- Rampa Rebellion of 1879, Vizagapatnam (now Visakhapatnam district)

- Rampa Rebellion (1922–1924), Visakhapatnam district

- Santhal Revolt (1885–1886)

- Munda rebellion

- Yadav rebellion

Tribal classification criteria and demands

Population complexities, and the controversies surrounding ethnicity and language in India, sometimes make the official recognition of groups as adivasis (by way of inclusion in the Scheduled Tribes list) political and contentious. However, regardless of their language family affiliations, Australoid and Negrito groups that have survived as distinct forest, mountain or island dwelling tribes in India and are often classified as adivasi.[52] The relatively autonomous Mongoloid tribal groups of Northeastern India (including Khasis, Apatani and Nagas), who are mostly Austro-Asiatic or Tibeto-Burman speakers, are also considered to be adivasis: this area comprises 7.5% of India's land area but 20% of its adivasi population.[53] However, not all autonomous northeastern groups are considered adivasis; for instance, the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Meitei of Manipur were once tribal but, having been settled for many centuries, are caste Hindus.[54]

It is also difficult, for a given social grouping, to definitively decide whether it is a 'caste' or a 'tribe'. A combination of internal social organisation, relationship with other groups, self-classification and perception by other groups has to be taken into account to make a categorisation, which is at best inexact and open to doubt.[55] These categorisations have been diffused for thousands of years, and even ancient formulators of caste-discriminatory legal codes (which usually only applied to settled populations, and not adivasis) were unable to come up with clean distinctions.[56]

Demands for tribal classification

The additional difficulty in deciding whether a group meets the criteria to be adivasi or not are the aspirational movements created by the federal and state benefits, including job and educational reservations, enjoyed by groups listed as scheduled tribes (STs).[57] In Manipur, Meitei commentators have pointed to the lack of scheduled tribe status as a key economic disadvantage for Meiteis competing for jobs against groups that are classified as scheduled tribes.[54] In Assam, Rajbongshi representatives have demanded scheduled tribe status as well.[58] In Rajasthan, the Gujjar community has demanded ST status, even blockading the national capital of Delhi to press their demand.[59] However, the Government of Rajasthan declined the Gujjars' demand, stating the Gujjars are treated as upper caste and are by no means a tribe.[60] In several cases, these claims to tribalhood are disputed by tribes who are already listed in the schedule and fear economic losses if more powerful groups are recognised as scheduled tribes; for instance, the Rajbongshi demand faces resistance from the Bodo tribe,[58] and the Meena tribe has vigorously opposed Gujjar aspirations to be recognised as a scheduled tribe.[61]

Endogamy, exogamy and ethnogenesis

Part of the challenge is that the endogamous nature of tribes is also conformed to by the vast majority of Hindu castes. Indeed, many historians and anthropologists believe that caste endogamy reflects the once-tribal origins of the various groups who now constitute the settled Hindu castes.[62] Another defining feature of caste Hindu society, which is often used to contrast them with Muslim and other social groupings, is lineage/clan (or gotra) and village exogamy.[63][64] However, these in-marriage taboos are also held ubiquitously among tribal groups, and do not serve as reliable differentiating markers between caste and tribe.[65][66][67] Again, this could be an ancient import from tribal society into settled Hindu castes.[68] Interestingly, tribes such as the Muslim Gujjars of Kashmir and the Kalash of Pakistan observe these exogamous traditions in common with caste Hindus and non-Kashmiri adivasis, though their surrounding Muslim populations do not.[63][69]

Some anthropologists, however, draw a distinction between tribes who have continued to be tribal and tribes that have been absorbed into caste society in terms of the breakdown of tribal (and therefore caste) boundaries, and the proliferation of new mixed caste groups. In other words, ethnogenesis (the construction of new ethnic identities) in tribes occurs through a fission process (where groups splinter-off as new tribes, which preserves endogamy), whereas with settled castes it usually occurs through intermixture (in violation of strict endogamy).[70]

Other criteria

Unlike castes, which form part of a complex and interrelated local economic exchange system, tribes tend to form self-sufficient economic units. For most tribal people, land-use rights traditionally derive simply from tribal membership. Tribal society tends to the egalitarian, with its leadership based on ties of kinship and personality rather than on hereditary status. Tribes typically consist of segmentary lineages whose extended families provide the basis for social organisation and control. Tribal religion recognises no authority outside the tribe.

Any of these criteria may not apply in specific instances. Language does not always give an accurate indicator of tribal or caste status. Especially in regions of mixed population, many tribal groups have lost their original languages and simply speak local or regional languages. In parts of Assam—an area historically divided between warring tribes and villages—increased contact among villagers began during the colonial period, and has accelerated since independence in 1947. A pidgin Assamese developed, whereas educated tribal members learnt Hindi and, in the late twentieth century, English.

Self-identification and group loyalty do not provide unfailing markers of tribal identity either. In the case of stratified tribes, the loyalties of clan, kin, and family may well predominate over those of tribe. In addition, tribes cannot always be viewed as people living apart; the degree of isolation of various tribes has varied tremendously. The Gonds, Santals, and Bhils traditionally have dominated the regions in which they have lived. Moreover, tribal society is not always more egalitarian than the rest of the rural populace; some of the larger tribes, such as the Gonds, are highly stratified.

The apparently wide fluctuation in estimates of South Asia's tribal population through the twentieth century gives a sense of how unclear the distinction between tribal and nontribal can be. India's 1931 census enumerated 22 million tribal people, in 1941 only 10 million were counted, but by 1961 some 30 million and in 1991 nearly 68 million tribal members were included. The differences among the figures reflect changing census criteria and the economic incentives individuals have to maintain or reject classification as a tribal member.

These gyrations of census data serve to underline the complex relationship between caste and tribe. Although, in theory, these terms represent different ways of life and ideal types, in reality they stand for a continuum of social groups. In areas of substantial contact between tribes and castes, social and cultural pressures have often tended to move tribes in the direction of becoming castes over a period of years. Tribal peoples with ambitions for social advancement in Indian society at large have tried to gain the classification of caste for their tribes. On occasion, an entire tribe or part of a tribe joined a Hindu sect and thus entered the caste system en masse. If a specific tribe engaged in practices that Hindus deemed polluting, the tribe's status when it was assimilated into the caste hierarchy would be affected.

Religion

The majority of Adivasi practice Hinduism and Christianity. During the last two decades Adivasi from Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand have converted to Protestant groups. Adivasi beliefs vary by tribe, and are usually different from the historical Vedic religion, with its monistic underpinnings, Indo-European deities (who are often cognates of ancient Iranian, Greek and Roman deities, e.g. Mitra/Mithra/Mithras), lack of idol worship and lack of a concept of reincarnation.[71]

Animism

Animism (from Latin animus, -i "soul, life") is the worldview that non-human entities (animals, plants, and inanimate objects or phenomena) possess a spiritual essence. The Encyclopaedia of Religion and Society estimates that 1–5% of India's population is animist.[72] India's government recognises that India's indigenous subscribe to pre-Hindu animist-based religions.[73][74]

Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of some indigenous tribal peoples,[75] especially prior to the development of organised religion.[76] Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, "animism" is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples' "spiritual" or "supernatural" perspectives. The animistic perspective is so fundamental, mundane, everyday and taken-for-granted that most animistic indigenous people do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to "animism" (or even "religion");[77] the term is an anthropological construct rather than one designated by the people themselves.

Donyi-Polo

Donyi-Polo is the designation given to the indigenous religions, of animistic and shamanic type, of the Tani, from Arunachal Pradesh, in northeastern India.[78][79] The name "Donyi-Polo" means "Sun-Moon".[80]

Sanamahi

Sanamahism is the worship of Sanamahi, the eternal force/cells responsible for the continuity of living creations. Sanamahi referred here is not to be confused with Lainingthou Sanamahi (The Supreme House-dwelling God of the Sanamahism). The religion has a great and unique traditional history which has been preserved till date for worshipping ancestors as almighty. Thus it signifies that Sanamahism is the worship of eternal force/cells present in living creations.

Sidaba Mapu, the Creator God of Sanamahism. Sanamahism is one of the oldest religion of South East Asia. It originated in Manipur and is mainly practiced by the Meitei, Kabui, Zeliangrong and other communities who inhabit in Manipur, Assam, Tripura.

Sarnaism

Sarnaism or Sarna[81][82][83] (local languages: Sarna Dhorom, meaning "religion of the holy woods") defines the indigenous religions of the Adivasi populations of the states of Central-East India, such as the Munda, the Ho, the Santali, the Khuruk, and the others. The Munda, Ho, Santhal and Oraon tribe followed the Sarna religion,[84] where Sarna means sacred grove. Their religion is based on the oral traditions passed from generation-to-generation. It strongly believes in one God, the Great Spirit.

Other tribal animist

Animist hunter gatherer Nayaka people of Nigrill's hills of South India.[85]

Animism is the traditional religion of Nicobarese people; their religion is marked by the dominance and interplay with spirit worship, witch doctors and animal sacrifice.[86]

Hinduism

Adivasi roots of modern Hinduism

Some historians and anthropologists assert that much of what constitutes folk Hinduism today is actually descended from an amalgamation of adivasi faiths, idol worship practices and deities, rather than the original Indo-Aryan faith.[87][88][89] This also includes the sacred status of certain animals such as monkeys, cows, fish, matsya, peacocks, cobras (nagas) and elephants and plants such as the sacred fig (pipal), Ocimum tenuiflorum (tulsi) and Azadirachta indica (neem), which may once have held totemic importance for certain adivasi tribes.[88]

Adivasi sants

A sant is an Indian holy man, and a title of a devotee or ascetic, especially in north and east India. Generally a holy or saintly person is referred to as a mahatma, paramahamsa, or swami, or given the prefix Sri or Srila before their name. The term is sometimes misrepresented in English as "Hindu saint", although "sant" is unrelated to "saint".

- Sant Buddhu Bhagat, led the Kol Insurrection (1831–1832) aimed against tax imposed on Mundas by Muslim rulers.

- Sant Dhira or Kannappa Nayanar[1], one of 63 Nayanar Shaivite sants, a hunter from whom Lord Shiva gladly accepted food offerings. It is said that he poured water from his mouth on the Shivlingam and offered the Lord swine flesh.[2]

- Sant Dhudhalinath, Gujarati, a 17th or 18th century devotee (P. 4, The Story of Historic People of India-The Kolis)

- Sant Ganga Narain, led the Bhumij Revolt (1832–1833) aimed against missionaries and British colonialists.

- Sant Girnari Velnathji, Gujarati of Junagadh, a 17th or 18th century devotee[90]

- Sant Gurudev Kalicharan Brahma or Guru Brahma, a Bodo whose founded the Brahma Dharma aimed against missionaries and colonialists. The Brahma Dharma movement sought to unite peoples of all religions to worship God together and survives even today.

- Sant Kalu Dev, Punjab, related with Fishermen community Nishadha

- Sant Kubera, ethnic Gujarati, taught for over 35 years, and had 20,000 followers in his time.[91]

- Sant Jatra Oraon, Oraon, led the Tana Bhagat Movement (1914–1919) aimed against the missionaries and British colonialists

- Sant Sri Koya Bhagat, a 17th or 18th century devotee[90]

- Sant Tantya Mama (Bhil), a Bhil after whom a movement is named after – the "Jananayak Tantya Bhil"

- Sant Tirumangai Alvar, Kallar, composed the six Vedangas in beautiful Tamil verse [3]

- Saint Kalean Guru (Kalean Murmu) is the most beloved person among Santal Tribes community who was widely popular 'Nagam Guru' Guru of Early Histories in fourteen century by the references of their forefathers.

Sages

- Bhaktaraj Bhadurdas, Gujarati, a 17th or 18th century devotee[90]

- Bhakta Shabari, a Nishadha woman who offered Shri Rama and Shri Laxmana her half-eaten ber fruit, which they gratefully accepted when they were searching for Shri Sita Devi in the forest.

- Madan Bhagat, Gujarati, a 17th or 18th century devotee[90]

- Sany Kanji Swami, Gujarati, a 17th or 18th century devotee[90]

- Bhaktaraj Valram, Gujarati, a 17th or 18th century devotee[90]

Maharishis

- Maharshi Matanga, Matanga Bhil, Guru of Bhakta Shabari. In fact, Chandalas are often addressed as ‘Matanga ’in passages like Varaha Purana 1.139.91

- Maharshi Valmiki, Kirata Bhil, composed the Ramayana.[21] He is considered to be an avatar in the Balmiki community.

Avatars

- Birsa Bhagwan or Birsa Munda, considered an avatar of Khasra Kora. People approached him as Singbonga, the Sun god. His sect included Christian converts.[4] He and his clan, the Mundas, were connected with Vaishnavite traditions as they were influenced by Sri Chaitanya.[5] Birsa was very close to the Panre brothers Vaishnavites.

- Kirata – the form of Lord Shiva as a hunter. It is mentioned in the Mahabharata. The Karppillikkavu Sree Mahadeva Temple, Kerala adores Lord Shiva in this avatar and is known to be one of the oldest surviving temples in Bharat.

- Vettakkorumakan, the son of Lord Kirata.

- Kaladutaka or 'Vaikunthanatha', Kallar (robber), avatar of Lord Vishnu.[6]

Other tribals and Hinduism

Some Hindus believe that Indian tribals are close to the romantic ideal of the ancient silvan culture[92] of the Vedic people. Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar said:

The tribals "can be given yajñopavîta (...) They should be given equal rights and footings in the matter of religious rights, in temple worship, in the study of Vedas, and in general, in all our social and religious affairs. This is the only right solution for all the problems of casteism found nowadays in our Hindu society."[93]

At the Lingaraj Temple in Bhubaneswar, there are Brahmin and Badu (tribal) priests. The Badus have the most intimate contact with the deity of the temple, and only they can bathe and adorn it.[94][95]

The Bhils are mentioned in the Mahabharata. The Bhil boy Ekalavya's teacher was Drona, and he had the honour to be invited to Yudhishthira's Rajasuya Yajna at Indraprastha.[96] Indian tribals were also part of royal armies in the Ramayana and in the Arthashastra.[97]

Shabari was a Bhil woman who offered Rama and Lakshmana jujubes when they were searching for Sita in the forest. Matanga, a Bhil, became a Brahmana.[citation needed]

ed against this custom.[98][clarification needed]

Demands for a separate religious code

Some Adivasi organisations have demanded that a distinct religious code be listed for Adivasis in the 2011 census of India. The All India Adivasi Conference was held on 1 and 2 January 2011 at Burnpur, Asansol, West Bengal. 750 delegates were present from all parts of India and cast their votes for Religion code as follows: Sari Dhorom – 632, Sarna – 51, Kherwalism – 14 and Other Religions – 03. Census of India.[99]

Tribal system

Tribals are not part of the caste system,[100] and usually constitute egalitarian societies. Christian tribals do not automatically lose their traditional tribal rules. T When in 1891 a missionary asked 150 Munda Christians to "inter-dine" with people of different rank, only 20 Christians did so, and many converts lost their new faith. Father Haghenbeek concluded on this episode that these rules are not "pagan", but a sign of "national sentiment and pride", and wrote:

"On the contrary, while proclaiming the equality of all men before God, we now tell them: preserve your race pure, keep your customs, refrain from eating with Lohars (blacksmiths), Turis (bamboo workers) and other people of lower rank. To become good Christians, it (inter-dining) is not required."[101]

However, many scholars argue that the claim that tribals are an egalitarian society in contrast to a caste-based society is a part of a larger political agenda by some to maximise any differences from tribal and urban societies. According to scholar Koenraad Elst, caste practices and social taboos among Indian tribals date back to antiquity:

"The Munda tribals not only practise tribal endogamy and commensality, but also observe a jâti division within the tribe, buttressed by notions of social pollution, a mythological explanation and harsh punishments.

A Munda Catholic theologian testifies: The tribals of Chhotanagpur are an endogamous tribe. They usually do not marry outside the tribal community, because to them the tribe is sacred. The way to salvation is the tribe. Among the Santals, it is tabooed to marry outside the tribe or inside ones clan, just as Hindus marry inside their caste and outside their gotra. More precisely: To protect their tribal solidarity, the Santals have very stringent marriage laws. A Santal cannot marry a non-Santal or a member of his own clan. The former is considered as a threat to the tribe's integrity, while the latter is considered incestuous. Among the Ho of Chhotanagpur, the trespasses which occasion the exclusion from the tribe without chance of appeal, are essentially those concerning endogamy and exogamy."

Inter-dining has also been prohibited by many Indian tribal peoples.[102]

Adivasi (STs) Demography in India

According to the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Orders (Amendment) Act, 1990, Scheduled Tribe can belong to any religion. The scheduled tribe population in Jharkhand constitutes 26.2% of the state.[104][105] Tribals in Jharkhand mainly follow Sarnaism, an animistic religion.[106] Chhattisgarh has also 32-25 per cent scheduled tribe population.[107][108][109] Assam has 40 lakh Adivasis.[110] Adivasis in India mainly follow Animism, Hinduism and Christianity.[111][112][113]

Education

Tribal communities in India are the least educationally developed. First generation learners have to face social, psychological and cultural barriers to get education. This has been one of the reason for poor performance of tribal students in schools.[114] Poor literacy rate since independence has resulted in absence of tribals in academia and higher education. The literacy rate for STs has gone up from 8.5% (male – 13.8%, female – 3.2%) in 1961 to 29.6% (male – 40.6%, female – 18.2%) in 1991 and to 40% (male – 59%, female – 37%) in 1999–2000.[114] States with large proportion of STs like Mizoram, Nagaland and Meghalaya have high literacy rate while States with large number of tribals like Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh have low tribal literacy rate.[115] Tribal students have very high drop-out rates during school education.[116]

Extending the system of primary education into tribal areas and reserving places for needing them, they say, to work in the fields. On the other hand, in those parts of the northeast where tribes have generally been spared the wholesale onslaught of outsiders, schooling has helped tribal people to secure political and economic benefits. The education system there has provided a corps of highly trained tribal members in the professions and high-ranking administrative posts. tribal children in middle and high schools and higher education institutions are central to government policy, but efforts to improve a tribe's educational status have had mixed results. Recruitment of qualified teachers and determination of the appropriate language of instruction also remain troublesome. Commission after commission on the "language question" has called for instruction, at least at the primary level, in the students' native language. In some regions, tribal children entering school must begin by learning the official regional language, often one completely unrelated to their tribal language.

Many tribal schools are plagued by high drop-out rates. Children attend for the first three to four years of primary school and gain a smattering of knowledge, only to lapse into illiteracy later. Few who enter continue up to the tenth grade; of those who do, few manage to finish high school. Therefore, very few are eligible to attend institutions of higher education, where the high rate of attrition continues. Members of agrarian tribes like the Gonds often are reluctant to send their children to school,

An academy for teaching and preserving Adivasi languages and culture was established in 1999 by the Bhasha Research and Publication Centre. The Adivasi Academy is located at Tejgadh in Gujarat.

Tribal languages

- Mizo language

- Chakma language

- Kui Language

- Gondi language

- Ho language/Munda/Santali language

- Kukni language

- Gamit language

- Chaudhari language

Economy

Most tribes are concentrated in heavily forested areas that combine inaccessibility with limited political or economic significance. Historically, the economy of most tribes was subsistence agriculture or hunting and gathering. Tribal members traded with outsiders for the few necessities they lacked, such as salt and iron. A few local Hindu craftsmen might provide such items as cooking utensils.

In the early 20th century, however, large areas fell into the hands of non-tribals, on account of improved transportation and communications. Around 1900, many regions were opened by the government to settlement through a scheme by which inward migrants received ownership of land free in return for cultivating it. For tribal people, however, land was often viewed as a common resource, free to whoever needed it. By the time tribals accepted the necessity of obtaining formal land titles, they had lost the opportunity to lay claim to lands that might rightfully have been considered theirs. The colonial and post-independence regimes belatedly realised the necessity of protecting tribals from the predations of outsiders and prohibited the sale of tribal lands. Although an important loophole in the form of land leases was left open, tribes made some gains in the mid-twentieth century, and some land was returned to tribal peoples despite obstruction by local police and land officials.

In the 1970s, tribal peoples came again under intense land pressure, especially in central India. Migration into tribal lands increased dramatically, as tribal people lost title to their lands in many ways – lease, forfeiture from debts, or bribery of land registry officials. Other non-tribals simply squatted, or even lobbied governments to classify them as tribal to allow them to compete with the formerly established tribes. In any case, many tribal members became landless labourers in the 1960s and 1970s, and regions that a few years earlier had been the exclusive domain of tribes had an increasingly mixed population of tribals and non-tribals. Government efforts to evict nontribal members from illegal occupation have proceeded slowly; when evictions occur at all, those ejected are usually members of poor, lower castes.

Improved communications, roads with motorised traffic, and more frequent government intervention figured in the increased contact that tribal peoples had with outsiders. Commercial highways and cash crops frequently drew non-tribal people into remote areas. By the 1960s and 1970s, the resident nontribal shopkeeper was a permanent feature of many tribal villages. Since shopkeepers often sell goods on credit (demanding high interest), many tribal members have been drawn deeply into debt or mortgaged their land. Merchants also encourage tribals to grow cash crops (such as cotton or castor-oil plants), which increases tribal dependence on the market for necessities. Indebtedness is so extensive that although such transactions are illegal, traders sometimes 'sell' their debtors to other merchants, much like indentured peons.

The final blow for some tribes has come when nontribals, through political jockeying, have managed to gain legal tribal status, that is, to be listed as a Scheduled Tribe.

Tribes in the Himalayan foothills have not been as hard-pressed by the intrusions of non-tribal. Historically, their political status was always distinct from the rest of India. Until the British colonial period, there was little effective control by any of the empires centred in peninsular India; the region was populated by autonomous feuding tribes. The British, in efforts to protect the sensitive northeast frontier, followed a policy dubbed the "Inner Line"; non-tribal people were allowed into the areas only with special permission. Postindependence governments have continued the policy, protecting the Himalayan tribes as part of the strategy to secure the border with China.

Government policies on forest reserves have affected tribal peoples profoundly. Government efforts to reserve forests have precipitated armed (if futile) resistance on the part of the tribal peoples involved. Intensive exploitation of forests has often meant allowing outsiders to cut large areas of trees (while the original tribal inhabitants were restricted from cutting), and ultimately replacing mixed forests capable of sustaining tribal life with single-product plantations. Nontribals have frequently bribed local officials to secure effective use of reserved forest lands.

The northern tribes have thus been sheltered from the kind of exploitation that those elsewhere in South Asia have suffered. In Arunachal Pradesh (formerly part of the North-East Frontier Agency), for example, tribal members control commerce and most lower-level administrative posts. Government construction projects in the region have provided tribes with a significant source of cash. Some tribes have made rapid progress through the education system (the role of early missionaries was significant in this regard). Instruction was begun in Assamese but was eventually changed to Hindi; by the early 1980s, English was taught at most levels. Northeastern tribal people have thus enjoyed a certain measure of social mobility.

The continuing economic alienation and exploitation of many adivasis was highlighted as a "systematic failure" by the Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh in a 2009 conference of chief ministers of all 29 Indian states, where he also cited this as a major cause of the Naxalite unrest that has affected areas such as the Red Corridor.[117][118][119][120][121]

Notable Adivasis

Independence movement

- Rani Gaidinliu – Political leader, Independence fighter

- Birsa Munda – Independence Fighter

- Laxman Nayak – Independence fighter, activist

- Komaram Bheem – Independence fighter

- Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu – Independence Fighters

- Baba Tilka Majhi – Independence Fighter

- Rindo Majhi

Politics and social service

- Kantilal Bhuria - Lok Sabha MP, Tribal Rights Activist, Former Union Cabinet Minister of Tribal Affairs, Agriculture & Food, Veteran Congress Leader from Madhya Pradesh.

- Kishore Chandra Deo - Lok Sabha MP, Tribal Rights Activist, Former Union Cabinet Minister of Tribal Affairs, Steel & Mines, Tribal Chief of Kurupam, Veteran Congress Leader from Andhra Pradesh.

- Vincent Pala - Lok Sabha MP, Former Union Minister of Water Resources, Congress Leader.

- Kanjibhai Patel - Politician

- Lalthanhawla – Politician

- Zoramthanga – Politician

- Jual Oram – Politician

- Ramvichar Netam – Politician

- Mahendra Karma – Politician

- Kartik Oraon – Politician

- Neiphiu Rio – Politician

- P. A. Sangma – Politician

- Kariya Munda – former Deputy Speaker, 15th Lok Sabha

- Harishankar Brahma – former Chief Election Commissioner of India

- Soni Sori – Political activist

- Dayamani Barla – Journalist, activist

- Tulasi Munda – Education activist

- C K Janu – Social activist

- Jaipal Singh – Hockey player, Adivasi activist.

- Sushila Kerketta – member of the 14th Lok Sabha of India

- Sarbananda Sonowal – 14th Chief Minister of Assam

- Mohanbhai Sanjibhai Delkar 6 time member of the Lok Sabha of India from Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Tribal leader of southern Part of Gujarat, Tribal Robin Hood.

Art and literature

- Ram Dayal Munda – Scholar, artist, Padma Sri awardee

- Teejan Bai – Indian Pandavani performer

- Anuj Lugun – Indian polymath

- Rupnath Brahma – Poet

- Jangarh Singh Shyam – Artist, founder of Jangarh Kalam

- Venkat Shyam – Artist

- Bhajju Shyam – Artist

- Temsula Ao – Poet, writer

- Mamang Dai – Journalist, author, former civil servant

Administration

- Armstrong Pame – IAS

- Rajeev Topno – IAS

- G C Murmu – IAS

Sports

- MC Mary Kom – Boxer

- Malavath Purna – Mountaineer

- Durga Boro – Footballer

- Kavita Raut – Athlete

- Limba Ram – Archer

- Laxmirani Majhi – Archer

- Munmun Lugun – Footballer

- Lal Mohan Hansda – Footballer

- Sanjay Balmuchu – Footballer

- Baichung Bhutia – Former captain, Indian football team

- Dilip Tirkey – Former captain, Indian hockey team

- Birendra Lakra – Indian hockey team

- Manohar Topno – Indian hockey team

- Masira Surin – Indian women's hockey team

- Sunita Lakra – Indian women's hockey team

- Jyoti Sunita Kullu – Former member, Indian women's hockey team

- Michael Kindo - Former member, Indian men's hockey team, Arjuna awardee

- Shylo Malsawmtluanga – Footballer

- Lalrindika Ralte – Footballer

- Jeje Lalpekhlua – Footballer

Military

- Albert Ekka – Param Vir Chakra, Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

- Rani Durgavati – Gond Queen

- Sangram Shah

Others

- Boa Sr.

- Haipou Jadonang

- Bhima Bhoi

- Kalicharan Brahma

- Angami Zapu Phizo

- Shürhozelie Liezietsu

- Shabari

- Lako Bodra – Varang Kshiti script creator, writer, activist

- Valmiki – Composer of Ramayana

- Neiliezhü Üsou

- Tantia Bhīl

- Kannappa Nayanar

- Pandit Raghunath Murmu – Chiki script creator, writer, activist

- Thirumangai Alvar

Tribal movement

- Mohanbhai Sanjibhai Delkar -Tribal Leader

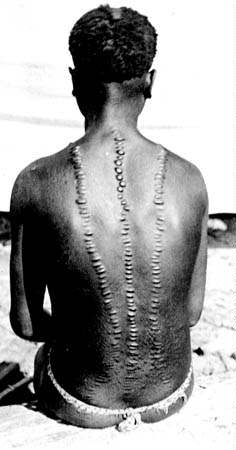

Gallery

Some portraits of adivasi people.

-

Young Baiga women

-

Saharia tribe

-

Bhil tribe

-

Bhil tribe

-

Gondi tribe

-

Gondi tribe

-

Gondi tribe

-

Gondi tribe

-

Bhil tribe

-

Bhil tribe

-

Bhil tribe

-

Bhil tribe

-

Saharia tribe

-

Adivasi Children of Gujarat

See also

- Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram

- Dalit

- C. K. Janu

- Hanumappa Sudarshan

- Kumar Suresh Singh

- Caste system

- Chakma

- Great Andamanese

- Indian tribal belt

- Jarawa people (Andaman Islands)

- List of Scheduled Tribes in India

- Scheduled castes

- Shompen people

- Tribal religions in India

- Eklavya Model Residential School

- Patalkot

Notes

- ^ [14] ... Although regarded by some British scholars as inferior to caste Hindus, the status of "adivasis" in practice most often paralleled that of the Hindus ... In areas where they accounted for a large proportion of the population, adivasis often wielded considerable ritual and political power, being involved in investiture of various kings and rulers throughout central India and Rajasthan ... In central India there were numerous "adivasi" kingdoms, some of which survived from medieval times to the nineteenth century ...

References

- ^ Lok Sabha Debates ser.10 Jun 41–42 1995 v.42 no.41-42, Lok Sabha Secretariat, Parliament of India, 1995, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... Adivasis are the aborigines of India ...

- ^ Minocheher Rustom Masani; Ramaswamy Srinivasan (1985). Freedom and Dissent: Essays in Honour of Minoo Masani on His Eightieth Birthday. Democratic Research Service. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

The Adivasis are the original inhabitants of India. That is what Adivasi means: the original inhabitant. They were the people who were there before the Dravidians. The tribals are the Gonds, the Bhils, the Murias, the Nagas and a hundred more.

- ^ Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1968), The Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi : Satyagraha in South Africa, Navajivan Publishing House, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... The Adivasis are the original inhabitants ...

- ^ 2011 Census Primary Census Abstract

- ^ "Scheduled Tribes at 8.6 per cent".

- ^ "8.6% for ST".

- ^ http://www.thedailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.php?nid=256768

- ^ http://genecampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Indigenous_knowledge_amongst_the_Tharus_of_the_Terai_Region_of_Uttar_Pradesh.pdf

- ^ Acharya, Deepak and Shrivastava Anshu (2008): Indigenous Herbal Medicines: Tribal Formulations and Traditional Herbal Practices, Aavishkar Publishers Distributor, Jaipur- India. ISBN 978-81-7910-252-7. pp 440

- ^ Salwa Judum

- ^ "Bringing rural realities on stage in urban India – The Hindu". thehindu.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Asian Centre for Human Rights". achrweb.org. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Elst, Koenraad: (2001)

- ^ a b c d Robert Harrison Barnes; Andrew Gray; Benedict Kingsbury (1995), Indigenous peoples of Asia, Association for Asian Studies, ISBN 0-924304-14-6, retrieved 25 November 2008,

The Concept of the Adivāsi: According to the political activists who coined the word in the 1930s, the "adivāsis" are the original inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent ...

- ^ "Adivasi, n. and adj." OED Online. Oxford University Press, June 2017. Web. 10 September 2017.

- ^ Louise Waite (2006), Embodied Working Lives: Work and Life in Maharashtra, India, Lexington Books, ISBN 0-7391-0876-X, retrieved 25 November 2008,

The scheduled tribes themselves tend to refer to their ethnic grouping as adivāsis, which means 'original inhabitant.' Hardiman continues to argue that the term adivāsi is preferable in India as it evokes a shared history of relative freedom in precolonial times ...

- ^ Govind Sadashiv Ghurye (1980), The Scheduled Tribes of India, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 0-87855-692-3, retrieved 25 November 2008,

I have stated above, while ascertaining the general attitude of Mr. Jaipal Singh to tribal problems, his insistence on the term 'Adivāsi' being used for Schedule Tribes... Sir, myself I claim to an Adivāsi and an original inhabitant of the country as Mr. Jaipal Singh pal... a pseudo-ethno-historical substantiation for the term 'Adivāsi'.

- ^ New Book: Anthropology of Primitive Tribes in India

- ^ a b Aloysius Irudayam; Jayshree P. Mangubhai; India Village Reconstruction; Development Project (2004), Adivasis Speak Out: Atrocities Against Adivasis in Tamil Nadu, Books for Change, ISBN 81-87380-78-0, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... uncivilised ... These forests and land territories assume a territorial identity precisely because they are the extension of the Adivasis' collective personality ...

- ^ C.R. Bijoy, Core Committee of the All India Coordinating Forum of Adivasis/Indigenous Peoples (February 2003), "The Adivasis of India – A History of Discrimination, Conflict, and Resistance", PUCL Bulletin, People's Union for Civil Liberties, India, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... Adivasis are not, as a general rule, regarded as unclean by caste Hindus in the same way as Dalits are. But they continue to face prejudice (as lesser humans), they are socially distanced and often face violence from society ...

- ^ a b Thakorlal Bharabhai Naik (1956), The Bhils: A Study, Bharatiya Adimjati Sevak Sangh, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... Valmiki, from whose pen this great epic had its birth, was himself a Bhil named Valia, according to the traditional accounts of his life ...

- ^ Edward Balfour (1885), The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Bernard Quaritch, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... In Mewar, the Grasia is of mixed Bhil and Rajput descent, paying tribute to the Rana of Udaipur ...

- ^ R.K. Sinha (1995), The Bhilala of Malwa, Anthropological survey of India, ISBN 978-81-85579-08-5, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... the Bhilala are commonly considered to be a mixed group who sprung from the marriage alliances of the immigrant male Rajputs and the Bhil women of the central India ...

- ^ a b R. Singh (2000), Tribal Beliefs, Practices and Insurrections, Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 81-261-0504-6, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The Munda Parha was known as 'Manki', while his Oraon counterpart was called 'Parha Raja.' The lands these adivasis occupied were regarded to be the village's patrimony ... The Gond rajas of Chanda and Garha Mandla were not only the hereditary leaders of their Gond subjects, but also held sway over substantial communities of non-tribals who recognized them as their feudal lords ...

- ^ Milind Gunaji (2005), Offbeat Tracks in Maharashtra: A Travel Guide, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-669-2, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The Navegaon is one of the forests in Maharashtra where the natives of this land still live and earn their livelihood by carrying out age old activities like hunting, gathering forest produce and ancient methods of farming. Beyond the Kamkazari lake is the Dhaavalghat, which is home to adivasis. They also have a temple here, the shrine of Lord Waghdev ...

- ^ Surajit Sinha, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences (1987), Tribal polities and state systems in pre-colonial eastern and north eastern India, K.P. Bagchi & Co., ISBN 81-7074-014-2, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The way in which and the extent to which tribal support had been crucial in establishing a royal dynasty have been made quite clear ... tribal loyalty, help and support were essential in establishing a ruling family ...

- ^ Hugh Chisholm (1910), The Encyclopædia Britannica, The Encyclopædia Britannica Co., retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The 16th century saw the establishment of a powerful Gond kingdom by Sangram Sah, who succeeded in 1480 as the 47th of the petty Gond rajas of Garha-Mandla, and extended his dominions to include Saugor and Damoh on the Vindhyan plateau, Jubbulpore and Narsinghpur in the Nerbudda valley, and Seoni on the Satpura highlands ...

- ^ PUCL Bulletin, February 2003

- ^ P. 27 Madhya Pradesh: Shajapur By Madhya Pradesh (India)

- ^ P. 219 Calcutta Review By University of Calcutta, 1964

- ^ a b Piya Chatterjee (2001), A Time for Tea: Women, Labor, and Post/colonial Politics on an Indian Plantation, Duke University Press, ISBN 0-8223-2674-4, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Among the Munda, customary forms of land tenure known as khuntkatti stipulated that land belonged communally to the village, and customary rights of cultivation, branched from corporate ownership. Because of Mughal incursions, non-Jharkhandis began to dominate the agrarian landscape, and the finely wrought system of customary sharing of labor, produce and occupancy began to crumble. The process of dispossession and land alienation, in motion since the mid-eighteenth century, was given impetus by British policies that established both zamindari and ryotwari systems of land revenue administration. Colonial efforts toward efficient revenue collection hinged on determining legally who had proprietal rights to the land ...

- ^ a b Ulrich van der Heyden; Holger Stoecker (2005), Mission und macht im Wandel politischer Orientierungen: Europäische Missionsgesellschaften in politischen Spannungsfeldern in Afrika und Asien zwischen 1800 und 1945, Franz Steiner Verlag, ISBN 3-515-08423-1, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The permanent settlement Act had an adverse effect upon the fate of the Adivasis for, "the land which the aboriginals had rested from the jungle and cultivated as free men from generation was, by a stroke of pen, declared to be the property of the Raja (king) and the Jagirdars." The alien became the Zamindars (Landlords) while the sons of the soil got reduced to mere tenants. Now, it was the turn of the Jagirdars-turned-Zamindars who further started leasing out land to the newcomers, who again started encroaching Adivasi land. The land grabbing thus went on unabated. By the year 1832 about 6,411 Adivasi villages were alienated in this process ...

- ^ O.P. Ralhan (2002), Encyclopaedia of Political Parties, Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 81-7488-865-9, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The Permanent Settlement was 'nothing short of the confiscation of raiyat lands in favor of the zamindars.' ... Marx says '... in Bengal as in Madras and Bombay, under the zamindari as under the ryotwari, the raiyats who form 11/12ths of the whole Indian population have been wretchedly pauperised.' To this may be added the inroads made by the Company's Government upon the village community of the tribals (the Santhals, Kols, Khasias etc.) ... There was a wholesale destruction of 'the national tradition.' Marx observes: 'England has broken down the entire framework of Indian society ...

- ^ Govind Kelkar; Dev Nathan (1991), Gender and Tribe: Women, Land and Forests in Jharkhand, Kali for Women, ISBN 1-85649-035-1, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... of the features of the adivasi land systems. These laws also showed that British colonial rule had passed on to a new stage of exploitation ... Forests were the property of the zamindar or the state ...

- ^ a b William Wilson Hunter; Hermann Michael Kisch; Andrew Wallace Mackie; Charles James O'Donnell; Herbert Hope Risley (1877), A Statistical Account of Bengal, Trübner, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The Kol insurrection of 1831, though, no doubt, only the bursting forth of a fire that had long been smouldering, was fanned into flame by the following episode:- The brother of the Maharaja, who was holder of one of the maintenance grants which comprised Sonpur, a pargana in the southern portion of the estate, gave farms of some of the villages over the heads of the Mankis and Mundas, to certain Muhammadans, Sikhs and others, who has obtained his favour ... not only was the Manki dispossessed, but two of his sisters were seduced or ravished by these hated foreigners ... one of them ..., it was said, had abducted and dishonoured the Munda's wife ...

- ^ Radhakanta Barik (2006), Land and Caste Politics in Bihar, Shipra Publications, ISBN 81-7541-305-0, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... As usually the zamindars were the moneylenders, they could pressurize the tenants to concede to high rent ...

- ^ Shashank Shekhar Sinha (2005), Restless Mothers and Turbulent Daughters: Situating Tribes in Gender Studies, Stree, ISBN 81-85604-73-8, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... In addition, many tribals were forced to pay private taxes ... ...

- ^ a b Economic and Political Weekly, No.6-8, vol. V.9, Sameeksha Trust, 1974, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The Adivasis spend their life-times working for the landlord-moneylenders and, in some cases, even their children are forced to work for considerable parts of their lives to pay off debts ...

- ^ Sita Venkateswar (2004), Development and Ethnocide: Colonial Practices in the Andaman Islands, IWGIA, ISBN 87-91563-04-6,

... As I have suggested previously, it is probable that some disease was introduced among the coastal groups by Lieutenant Colebrooke and Blair's first settlement in 1789, resulting in a marked reduction of their population. The four years that the British occupied their initial site on the south-east of South Andaman were sufficient to have decimated the coastal populations of the groups referred to as Jarawa by the Aka-bea-da ...

- ^ Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza; Francesco Cavalli-Sforza (1995), The Great Human Diasporas: The History of Diversity and Evolution, Basic Books, ISBN 0-201-44231-0,

... Contact with whites, and the British in particular, has virtually destroyed them. Illness, alcohol, and the will of the colonials all played their part; the British governor of the time mentions in his diary that he received instructions to destroy them with alcohol and opium. He succeeded completely with one group. The others reacted violently ...

- ^ Paramjit S. Judge (1992), Insurrection to Agitation: The Naxalite Movement in Punjab, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-527-0, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The Santhal insurrection in 1855–56 was a consequence of the establishment of the permanent Zamindari Settlement introduced by the British in 1793 as a result of which the Santhals had been dispossesed of the land that they had been cultivating for centuries. Zamindars, moneylenders, traders and government officials exploited them ruthlessly. The consequence was a violent revolt by the Santhals which could only be suppressed by the army ...

- ^ The Indian Journal of Social Work, vol. v.59, Department of Publications, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, 1956, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Revolts rose with unfailing regularity and were suppressed with treachery, brute force, tact, cooption and some reforms ...

- ^ Roy Moxham (2003), Tea, Carroll & Graf Publishers, ISBN 0-7867-1227-9, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... many of the labourers came from Chota Nagpur District ... home to the Adivasis, the most popular workers with the planters – the '1st class jungley.' As one of the planters, David Crole, observed: 'planters, in a rough and ready way, judge the worth of a coolie by the darkness of the skin.' In the last two decades of the nineteenth century 350,000 coolies went from Chota Nagpur to Assam ...

- ^ HEUZE, Gérard: Où Va l’Inde Moderne? L’Harmattan, Paris 1993. A. Tirkey: "Evangelization among the Uraons", Indian Missiological Review, June 1997, esp. p. 30-32. Elst 2001

- ^ Page 63 Tagore Without Illusions by Hitendra Mitra

- ^ Sameeksha Trust, P. 1229 Economic and Political Weekly

- ^ P. 4 "Freedom Movement in Khurda" Archived 29 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Dr. Atul Chandra Pradhan

- ^ P. 111 The Freedom Struggle in Hyderabad: A Connected Account By Hyderabad (India : State)

- ^ Tribal struggle of Singhbhum

- ^ P. 32 Social and Political Awakening Among the Tribals of Rajasthan By Gopi Nath Sharma

- ^ P. 420 Who's who of Freedom Struggle in Andhra Pradesh By Sarojini Regani

- ^ James Minahan and Leonard W. Doob (1996), Nations Without States: A Historical Dictionary of Contemporary National Movements, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-28354-0, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... The Adivasi tribes encompass the pre-Dravidian holdovers from ancient India ...

- ^ Sarina Singh; Joe Bindloss; Paul Clammer; Janine Eberle (2005), India, Lonely Planet, ISBN 1-74059-694-3, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... Although the northeast states make up just 7.5% of the geographical area of India, the region is home to 20% of India's Adivasis (tribal people). The following are the main tribes ... Nagas ... Monpas ... Apatani & Adi ... Khasi ...

- ^ a b Moirangthem Kirti Singh (1988), Religion and Culture of Manipur, Manas Publications, ISBN 81-7049-021-9, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The Meiteis began to think that root cause of their present unrest was their contact with the Mayangs, the outsider from the rest of India in matters of trade, commerce, religious belief and the designation of the Meiteis as caste Hindus in the Constitution of India. The policy of reservations for the scheduled castes and tribes in key posts began to play havoc ...

- ^ Man, vol. v.7, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1972, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Nor, for that matter, does a traits approach to drawing distinctions between tribe and caste lead to any meaningful interpretation of social or civilizational processes. Social boundaries must be defined in each case (community or regional society) with reference to the modes of social classification, on the one hand, and processes of social interaction, on the other. It is in their inability to relate these two aspects of the social phenomenon through a model of social reality that most behavioural exercises come to grief ...

- ^ Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (1959), Lōkayata: A Study in Ancient Indian Materialism, People's Publishing House, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Even the authors of our traditional law-codes and other works did not know whether to call a particular group of backward people a caste or a tribe ...

- ^ Robert Goldmann; A. Jeyaratnam Wilson (1984), From Independence to Statehood: Managing Ethnic Conflict in Five African and Asian States, Pinter, ISBN 0-86187-354-8, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Because the question of what groups are to be given preferences is constitutionally and politically open, the demand for preferences becomes a device for political mobilisation. Politicians can mobilise members of their caste, religious or linguistic community around the demand for inclusion on the list of those to be given preferences ... As preferences were extended to backward castes, and as more benefits were given to scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, the 'forward' castes have ...

- ^ a b Col. Ved Prakash (2006), Encyclopaedia of North-east India, Vol# 2, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 81-269-0704-5, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... An angry mob of Koch-Rajbongshis (KRs) ransacked 4-8-03 the BJP office, Guwahati, demanding ST status for the KRs ... the KRs have been demanding the ST status for long, and the Bodos are stoutly opposed to it ...

- ^ "Gujjars enforce blockade; Delhi tense", The Times of India, 29 May 2008, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Gujjars on Thursday blocked road and rail traffic in the capital and adjoining areas as part of their 'NCR rasta roko' agitation ... The NCR agitation, called by All India Gujjar Mahasabha, is in support of the community's demand for Scheduled Tribe status in Rajasthan ...

- ^ "rajasthan-government-denies-st-status-to-gujjars", merinews

- ^ "What the Meena-Gujjar conflict is about", Rediff, 1 June 2007, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Rajasthan is sitting on a potential caste war between the Gujjars and Meenas with the former demanding their entry into the Schedule Tribes list while the Meenas are looking to keep their turf intact by resisting any tampering with the ST quota ...

- ^ Mamta Rajawat (2003), Scheduled Castes in India: a Comprehensive Study, Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 81-261-1339-1, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... endogamy is basic to the morphology of caste but for its origin and sustenance one has to see beyond ... D.D. Kosambi says that the fusion of tribal elements into society at large lies at the foundation of the caste system; Irfan Habib concurs, suggesting that when tribal people were absorbed they brought with them their endogamous customs ...

- ^ a b Mohammad Abbas Khan (2005), Social Development in Twenty First Century, Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 81-261-2130-0, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... in North India, high caste Hindus regard the village as an exogamous unit. Girls born within the village are called 'village daughters' and they do not cover their faces before local men, whereas girls who come into the village by marriage do so ... With Christians and Muslims, the elementary or nuclear family is the exogamous unit. Outside of it marriages are possible ... Lineage exogamy also exists among the Muslim Gujjars of Jammu and Kashmir ...

- ^ Richard V. Weekes (1984), Muslim Peoples: A World Ethnographic Survey, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-24640-8, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The preference for in-marriage produces the reticulated kinship system characteristic of Punjabi Muslim society, as opposed to Hindu lineage exogamy and preference for marriage outside one's natal village ...

- ^ Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi (2004), South Asian Culture: An Anthropological Perspective, Oriental Publishers & Distributors, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... The tribal communities, by and large, also practise clan exogamy, which means marrying outside the totemic division of a tribe ...

- ^ Georg Pfeffer (1982), Status and Affinity in Middle India, F. Steiner, ISBN 3-515-03913-9, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Elwin documents the strict observance of this rule: Out of 300 marriages recorded, not a single one broke the rule of village exogamy ...

- ^ Rajendra K. Sharma (2004), Indian Society, Institutions and Change: Institutions and Change, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 81-7156-665-0, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Among many Indian tribes it is the recognized custom to marry outside the village. This restriction is prevalent in the Munda and other tribes of Chhota Nagpur of Madhya Pradesh ... the Naga tribe of Assam is divided into Khels. Khel is the name given to the residents of the particular place, and people of one Khel cannot marry each other ...

- ^ John Vincent Ferreira (1965), Totemism in India, Oxford University Press, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... there is every reason to believe that the inspiration leading to the formation of exogamous gotras came from the aborigines ...

- ^ Monika Böck; Aparna Rao (2000), Culture, Creation, and Procreation: Concepts of Kinship in South Asian Practice, Berghahn Books, ISBN 1-57181-912-6, retrieved 26 November 2008,

... Kalasha kinship is indeed orchestrated through a rigorous system of patrilineal descent defined by lineage exogamy ... Lineage exogamy thus distinguishes Kalasha descent groups as discretely bounded corporations, in contrast to the nonexogamous 'sliding lineages' (Bacon 1956) of surrounding Muslims ...

- ^ Thomas R. Trautmann (1997), Aryans and British India, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-20546-4, retrieved 26 November 2008,

...The radiating, segmentary character of the underlying genealogical figure requires that the specifications be unilineal ... we have in the Dharmasastra doctrine of jatis a theory of ethnogenesis through intermixture or marriage of persons of different varnas, and secondary and tertiary intermixtures of the original ones, leading to a multitude of units, rather than the radiating segmentary structure of ethnogenesis by fission or descent ...

- ^ Todd Scudiere (1997), Aspects of Death and Bereavement Among Indian Hindus and American Christians: A Survey and Cross-cultural Comparison, University of Wisconsin – Madison, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... the Vedic Aryan was not particularly eager to enter heaven, he was too much this-worldly oriented. A notion of reincarnation was not introduced until later. However, there was a concept of a universal force – an idea of an underlying monistic reality that was later called Brahman ...

- ^ http://hirr.hartsem.edu/ency/Animism.htm

- ^ "BBC NEWS | World | Europe | Indigenous people 'worst-off world over'". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Chakma, S.; Jensen, M.; International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (2001). Racism Against Indigenous Peoples. IWGIA. p. 196. ISBN 9788790730468. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Hicks, David (2010). Ritual and Belief: Readings in the Anthropology of Religion (3 ed.). Rowman Altamira. p. 359.

Tylor's notion of animism—for him the first religion—included the assumption that early Homo sapiens had invested animals and plants with souls ...

- ^ "Animism". Contributed by Helen James; coordinated by Dr. Elliott Shaw with assistance from Ian Favell. ELMAR Project (University of Cumbria). 1998–99.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Native American Religious and Cultural Freedom: An Introductory Essay". The Pluralism Project. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Diana Eck. 2005.

- ^ Rikam, 2005. p. 117

- ^ Mibang, Chaudhuri, 2004. p. 47

- ^ Dalmia, Sadana, 2012. pp. 44–45

- ^ Minahan, 2012. p. 236

- ^ Sachchidananda, 1980. p. 235

- ^ Srivastava, 2007.

- ^ "ST panel for independent religion status to Sarna". articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature: K – Z. Vol. 2. Thoemmes Continuum. 2005. p. 82. ISBN 9781843711384. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Mann, R.S. (2005). Andaman and Nicobar Tribes Restudied: Encounters and Concerns. Mittal Publications. p. 204. ISBN 9788183240109. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ S.G. Sardesai (1986), Progress and Conservatism in Ancient India, People's Publishing House, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... The centre of Rig Vedic religion was the Yajna, the sacrificial fire. ... There is no Atma, no Brahma, no Moksha, no idol worship in the Rig Veda ...

- ^ a b Shiv Kumar Tiwari (2002), Tribal Roots of Hinduism, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 81-7625-299-9, retrieved 12 December 2008

- ^ Kumar Suresh Singh (1985), Tribal Society in India: An Anthropo-historical Perspective, Manohar, retrieved 12 December 2008,

... Shiva was a "tribal deity" to begin with and forest-dwelling communities, including those who have ceased to be tribals and those who are tribals today ...

- ^ a b c d e f (P. 4, The Story of Historic People of India-The Kolis)

- ^ P. 269 Brāhmanism and Hindūism, Or, Religious Thought and Life in India: As Based on the Veda and Other Sacred Books of the Hindūs (Google eBook) by Sir Monier Monier-Williams

- ^ Thomas Parkhill: The Forest Setting in Hindu Epics.

- ^ M.S. Golwalkar: Bunch of Thoughts, p.479.

- ^ JAIN, Girilal: The Hindu Phenomenon. UBSPD, Delhi 1994.

- ^ Eschmann, Kulke and Tripathi, eds.: Cult of Jagannath, p.97. Elst 2001

- ^ Mahabharata (I.31–54) (II.37.47; II.44.21) Elst 2001

- ^ Kautilya: The Arthashastra 9:2:13-20, Penguin edition, p. 685. Elst 2001

- ^ "The Telegraph – Calcutta : Jamshedpur | Tribal groups on collision course". telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ http://in.news.yahoo.com/43/20100224/812/tnl-tribals-appeal-for-separate-religion.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Plight of India's tribal peoples". BBC News. 10 December 2004. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ A. Van Exem: "The Mistake, reviewed after a century", Sevartham 1991. Elst 2001

- ^ veddha[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Census of India 2011, Primary Census Abstract

PPT, Scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India (October 28, 2013).

PPT, Scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India (October 28, 2013).

- ^ "Marginal fall in tribal population in Jharkhand".

- ^ "Jharkhand's population rises, STs' numbers decline". dailypioneer.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "In Jharkhand's Singhbhum, religion census deepens divide among tribals".

- ^ "'Chhattisgarh needs a tribal Chief Minister'".

- ^ "Feature". pib.nic.in. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Population growth rate declines in Naxalite and tribal areas of Chhattisgarh".

- ^ "Why Assam's adivasis are soft targets".

- ^ "Appendix F Adivasi vs Vanvasi: The Hinduization of Tribals in India".

- ^ "In Jharkhand, tribes bear the cross of conversion politics".

- ^ "India, largely a country of immigrants – The Hindu". thehindu.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Education of Tribal Children in India — Portal". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001202/120281e.pdf

- ^ "School Dropout Rate Among Tribals Remains High- The New Indian Express". newindianexpress.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "PM's snub to Maoists: Guns don't ensure development of tribals". The Times of India. 4 November 2009.

- ^ "Indian PM reaches out to tribes". BBC News. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Shrinivasan, Rukmini (16 January 2010). "Tribals make poor progress, stay at bottom of heap". The Times of India.

- ^ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Main News". tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Dhar, Aarti (4 November 2009). "Sustained economic activity not possible under shadow of gun: PM". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. India: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. Tribes.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. India: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. Tribes.

Further reading

- Tribal Heritage of India, by Shyama Charan Dube, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Indian Council of Social Science Research, Anthropological Survey of India. Published by Vikas Pub. House, 1977. ISBN 0-7069-0531-8.

- Lal, K. S. (1995). Growth of Scheduled Tribes and Castes in Medieval India. ISBN 9788186471036

- Russell, R. V., The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, London, 1916.

- Elst, Koenraad. Who is a Hindu? (2001) ISBN 81-85990-74-3

- Raj, Aditya & Papia Raj (2004) "Linguistic Deculturation and the Importance of Popular Education among the Gonds in India" Adult Education and Development 62: 55–61

- Vindicated by Time: The Niyogi Committee Report (edited by S.R. Goel, 1998) (1955)

- Tribal Movements in India, by Kumar Suresh Singh. Published by Manohar, 1982.

- Tribal Society in India: An Anthropo-historical Perspective, by Kumar Suresh Singh. Published by Manohar, 1985.