Wildcat

| Wildcat | |

|---|---|

| |

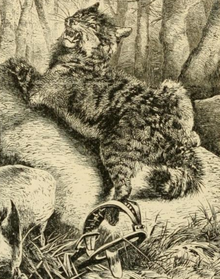

| European wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Felis |

| Binomial name | |

| Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777 | |

| Felis lybica Forster, 1780 | |

![Wildcat range[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Wild_Cat_Felis_silvestris_distribution_map.png/220px-Wild_Cat_Felis_silvestris_distribution_map.png)

| |

| Wildcat range[1] | |

![Distribution of five Felis species[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/Wiki-Felis_sylvestris.png/220px-Wiki-Felis_sylvestris.png)

| |

| Distribution of five Felis species[2] | |

The wildcat is a species complex of small wild cats comprising two species: the European wildcat (Felis silvestris) and the African wildcat (F. lybica). The European wildcat is native to forest habitats in Europe and the Caucasus while the African wildcat is native to savannas and steppes throughout Africa, Southwest and Central Asia into India and western China.[3] As of 2005, 22 wildcat subspecies were recognised as valid taxa.[4]

The wildcat is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List since 2002, as it is widely distributed, with a global population exceeding 20,000 mature individuals. It is considered threatened by introgressive hybridisation with the domestic cat (F. catus) and potential transmission of diseases, where both species occur in close proximity. Localised threats include being hit by vehicles, and persecution.[1]

The wildcat species differ in fur markings and size: the European wildcat is striped, has long fur and a bushy tail with a rounded tip and is larger than a domestic cat, while the African wildcat is faintly striped, has short sandy-gray fur, banded legs, red-backed ears and a tapering tail; the Asiatic wildcat (F. lybica ornata) is spotted.[5]

The African wildcat is the ancestor of the domestic cat. Taming and domestication of the African wildcat began approximately 7500 years BCE in the Fertile Crescent region of the Near East. The association of wildcats and humans appears to have developed along with the establishment of settlements during the Neolithic Revolution, when rodents in grain stores of early farmers attracted wildcats.[2]

Characteristics

The wildcat has pointed ears, which are moderate in length and broad at the base.[6][7] Its whiskers are white, number 7 to 16 on each side and reach 5–8 cm (2.0–3.1 in) in length on the muzzle. Whiskers are also present on the inner surface of the paw and measure 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in). Its eyes are large, with vertical pupils and yellowish-green irises. The eyelashes range from 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) in length, and can number 6 to 8 per side.[8] The wildcat has good night vision, having 20 to 100% higher retinal ganglion cell densities[vague] than the domestic cat. It may[vague] have colour vision as the densities of its cone receptors are more than 100% higher than in the domestic cat.[citation needed]

Both sexes possess pre-anal glands, which consist of moderately sized sweat and sebaceous glands around the anal opening. Large-sized sebaceous and scent glands extend along the full length of the tail on the dorsal side. Male wildcats have pre-anal pockets located on the tail, which are activated upon reaching sexual maturity. These pockets play a significant role in reproduction and territorial marking. The species has two thoracic and two abdominal teats.[9]

Fur

Asiatic wildcat

The Asiatic wildcat's coat is lighter, less dense and shorter than the European wildcat's. Its tail appears much thinner, as the hairs there are shorter, and more close-fitting. Its colours and patterns vary greatly, though the general background colour of the skin on the body's upper surface is very lightly coloured. The hairs along the spine are usually darker, forming a dark gray, brownish, or ochreous band. Small and rounded spots cover the entirety of its upper body. These spots are solid and sharply defined, and do not occur in clusters or appear in rosette patterns. They usually do not form transverse rows or transverse stripes on the trunk. The thighs are distinctly striped. The underside is whitish, with a light gray, creamy or pale yellow tinge. The spots on the chest and abdomen are much larger and more blurred than on the back. The lower neck, throat, neck, and the region between the forelegs are devoid of spots, or have bear them only distinctly. The tail is mostly the same colour as the back, with the addition of a dark and narrow stripe along the upper two-thirds of the tail. The tip of the tail is black, with two to five black transverse rings above it. The upper lips and eyelids are light, pale yellow-white. The facial region is of an intense gray colour, while the top of the head is covered with a dark gray coat. In some specimens, the forehead is covered in dense clusters of brown spots. A narrow, dark brown stripe extends from the corner of the eye to the base of the ear.[10]

Size

Both wildcat species are larger than the domestic cat.[6][7] The European wildcat has relatively longer legs, a more robust build, and a greater skull volume.[11] The tail is long, and usually slightly exceeds one-half of the animal's body length. Its skull is more spherical in shape than that of the jungle cat (F. chaus) and leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis). Its dentition is relatively smaller and weaker than the jungle cat's.[12] The species size varies according to Bergmann's rule, with the largest specimens occurring in cool, northern areas of Europe and Asia such as Mongolia, Manchuria and Siberia.[13] Males measure 43–91 cm (17–36 in) in head to body length, 23–40 cm (9.1–15.7 in) in tail length, and normally weigh 5–8 kg (11–18 lb). Females are slightly smaller, measuring 40–77 cm (16–30 in) in body length and 18–35 cm (7.1–13.8 in) in tail length, and weighing 3–5 kg (6.6–11.0 lb).[12]

Taxonomy

Felis (catus) silvestris was the scientific name used in 1778 by Johann von Schreber who described the European wildcat based on descriptions and names proposed by earlier naturalists such as Mathurin Jacques Brisson, Ulisse Aldrovandi and Conrad Gessner.[14] Felis lybica was the scientific name used in 1780 by Georg Forster who described a wildcat from the Barbary Coast.[15] In subsequent decades, several naturalists and explorers described 40 wildcat specimens collected in European, African and Asian range countries. The taxonomist Reginald Innes Pocock reviewed the collection of wildcat skins and skulls in the Natural History Museum, London, and in 1951 designated seven F. silvestris subspecies from Europe to Asia Minor, and 25 F. lybica subspecies from Africa, and West to Central Asia. Pocock differed between the:[6][7]

- Forest wildcat subspecies (silvestris group)

- Steppe wildcat subspecies (ornata-caudata group): is distinguished from the forest wildcat by being smaller, with comparatively lighter fur colour, and longer and more sharply-pointed tails[7]

- Bush wildcat subspecies (ornata-lybica group): is distinguished from the steppe wildcats by paler fur, well-developed spot patterns and bands.[7] The domestic cat is thought to have derived from this group.[16][17][2]

As of 2005[update], 22 subspecies were recognised by Mammal Species of the World, allocating subspecies according to Pocock's assessment.[4]

The Cat Classification Task Force revised the taxonomy of the Felidae in 2017, and recognises the following as valid taxa:[3]

| Species and subspecies | Characteristics | Image |

|---|---|---|

| European wildcat (F. silvestris) Schreber, 1777; syn. F. s. ferus Erxleben, 1777; obscura Desmarest, 1820; hybrida J. B. Fischer, 1829; ferox Martorelli, 1896; morea Trouessart, 1904; grampia Miller, 1907; tartessia Miller, 1907; molisana Altobello, 1921; reyi Lavauden, 1929; jordansi Schwarz, 1930; euxina Pocock, 1943; cretensis Haltenorth, 1953 | This species and the nominate subspecies has dark gray fur with distinct transverse stripes on the sides and a bushy tail with a rounded black tip.[14][6] |  |

| Caucasian wildcat (F. s. caucasica) Satunin, 1905; syn. trapezia Blackler, 1916 | This subspecies is light gray with well developed patterns on head and back, and faint transverse bands and spots on the sides. The tail has three distinct black transverse rings.[18] | |

| African wildcat (F. lybica) Forster, 1780; syn. F. l. ocreata Gmelin, 1791; nubiensis Kerr, 1792; maniculata Temminck, 1824; mellandi Schwann, 1904; rubida Schwann, 1904; ugandae Schwann, 1904; nandae Heller, 1913; taitae Heller, 1913; nesterovi Birula, 1916; iraki Cheesman, 1921; hausa Thomas and Hinton, 1921; griselda Thomas, 1926; brockmani Pocock, 1944; foxi Pocock, 1944; pyrrhus Pocock, 1944; gordoni Harrison, 1968 | This species has pale, buffish or light-grayish fur with a tinge of red on the dorsal band; the length of its pointed tail is about two third of the head to body size.[19] |  |

| Southern African wildcat (F. l. cafra) Desmarest, 1822; syn. F. l. xanthella Thomas, 1926; vernayi Roberts, 1932 | This subspecies has a pale fur with a faint pattern.[7] | |

| Asiatic wildcat (F. l. ornata) Gray, 1830; syn. syriaca Tristam, 1867; caudata Gray, 1874; maniculata Yerbury and Thomas, 1895; kozlovi Satunin, 1905; matschiei Zukowsky, 1914; griseoflava Zukowsky, 1915; longipilis Zukowsky, 1915; macrothrix Zukowsky, 1915; murgabensis Zukowsky, 1915; schnitnikovi Birula, 1915; issikulensis Ognev, 1930; tristrami Pocock, 1944 | This subspecies has dark spots on light, ochreous-gray coloured fur.[7] |  |

Evolution

The wildcat is a member of the Felidae, a family that had a common ancestor about 10–15 million years ago.[20] Felis species diverged from the Felidae around 6–7 million years ago. The European wildcat diverged from Felis about 1.09 to 1.4 million years ago.[21]

The European wildcat's direct ancestor was Felis lunensis, which lived in Europe in the late Pliocene and Villafranchian periods. Fossil remains indicate that the transition from lunensis to silvestris was completed by the Holstein interglacial about 340,000 to 325,000 years ago.[22]

At some point during the Late Pleistocene (possibly 50,000 years ago), the wildcat migrated from Europe into the Middle East, giving rise to the steppe wildcat phenotype. Within possibly 10,000 years, the steppe wildcat spread eastwards into Asia and southwards to Africa.[5]

Distribution and habitat

The European wildcat was once widely distributed in forested regions from Europe up to Turkey and the Caucasus. In the Pyrenees, it occurs from sea level to 2,250 m (7,380 ft). Between the late 17th and mid 20th centuries, its European range became fragmented due to large-scale hunting and regional extirpation. It is possibly extinct in the Czech Republic, and considered regionally extinct in Austria, though vagrants from Italy are spreading into Austria. It has always been absent in Fennoscandia and Estonia.[1] Sicily is the only island in the Mediterranean Sea with a native wildcat population.[23]

The African wildcat lives in a wide range of habitats, with the exception of closed tropical forests, but throughout the savannahs of West Africa from Mauritania on the Atlantic coast eastwards to the Horn of Africa. Small numbers occur in the Sahara, particularly in hilly and mountainous areas such as the Hoggar.[24] It occurs around the Arabian Peninsula's periphery to the Caspian Sea, encompassing Mesopotamia, Israel and Palestine region. In Central Asia, it ranges into Xinjiang and southern Mongolia, and in South Asia into the Thar Desert and arid regions in India.[1]

Behaviour and ecology

The wildcat is a largely solitary animal, except during the breeding period. The size of its home range varies according to terrain, the availability of food, habitat quality, and the age structure of the population. Male and female ranges overlap, though core areas within territories are avoided by other cats. Females tend to be more sedentary than males, as they require an exclusive hunting area when raising kittens.[25] Within its territory, the wildcat leaves scent marks in different sites, the quantity of which increases during estrus, when the cat's preanal glands enlarge and secrete strong smelling substances, including trimethylamine.[26] Territorial marking consists of urinating on trees, vegetation and rocks, and depositing faeces in conspicuous places. The wildcat may also scratch trees, leaving visual markers, and leaving its scent through glands in its paws.[25]

The wildcat does not dig its own burrows, instead sheltering in the hollows of old or fallen trees, rock fissures, and the abandoned nests or earths of other animals (heron nests, and abandoned fox or badger earths in Europe,[27] and abandoned fennec dens in Africa[28]). When threatened, a wildcat with a den will retreat into it, rather than climb trees. When taking residence in a tree hollow, the wildcat selects one low to the ground. Dens in rocks or burrows are lined with dry grasses and bird feathers. Dens in tree hollows usually contain enough sawdust to make lining unnecessary. During flea infestations, the wildcat leaves its den in favour of another. During winter, when snowfall prevents the wildcat from travelling long distances, it remains within its den more than usual.[27]

Hunting and diet

When hunting, the wildcat patrols forests and along forest boundaries and glades. In favourable conditions, it will readily feed in fields. The wildcat will pursue prey atop trees, even jumping from one branch to another. On the ground, it lies in wait for prey, then catches it by executing a few leaps, which can span three metres. Sight and hearing are the wildcat's primary senses when hunting, its sense of smell being comparatively weak. When hunting aquatic prey, such as ducks or nutrias, the wildcat waits on trees overhanging the water. It kills small prey by grabbing it in its claws, and piercing the neck or occiput with its fangs. When attacking large prey, the wildcat leaps upon the animal's back, and attempts to bite the neck or carotid. It does not persist in attacking if prey manages to escape it.[29] Wildcats hunting rabbits have been observed to wait above rabbit warrens for their prey to emerge.[30] Although primarily a solitary predator, the wildcat has been known to hunt in pairs or in family groups, with each cat devoted entirely to listening, stalking, or pouncing. While wildcats in Europe will cache their food, such a behaviour has not been observed in their African counterparts.[31]

Throughout its range, small rodents are the wildcat's primary prey, followed by birds, especially ducks and other waterfowl, galliformes, pigeons and passerines, dormice, hares, nutria, and insectivores.[32] Unlike the housecat, the wildcat can consume large fragments of bone without ill-effect.[33] Although it kills insectivores, such as moles and shrews, it rarely eats them.[32] When living close to human settlements, it preys on poultry.[32] In the wild, it consumes up to 600 g (21 oz) of food daily.[34]

The Scottish wildcat mainly preys on European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and field vole (Microtus agrestis), wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus), field and bank vole (Myodes glareolus), and of birds.[35]

In Western Europe, the wildcat feeds on hamsters, brown rats, dormice, water voles, voles, and wood mouse. From time to time, small carnivores like martens, European polecat, stoat, and least weasel (Mustela nivalis) are preyed upon, as well as the fawns of red deer, roe deer, and chamois. In the Carpathians, the wildcat feeds primarily on yellow-necked mouse, northern red-backed vole Tatra pine vole, and occasionally also European hare. In Transcarpathia, the wildcat's diet consists of mouse-like rodents, galliformes, and squirrels. Wildcats in the Dnestr swamps feed on Microtus, water voles, and birds, while those living in the Prut swamps primarily target water voles, brown rats, and muskrats. Birds taken by Prut wildcats include warblers, ferruginous duck, Eurasian coot, spotted crake, and gadwall. In Moldavia, the wildcat's winter diet consists primarily of rodents, while it preys on birds, fish, and crayfish in summer. Brown rats and water voles, as well as muskrats and waterfowl are the main sources of food for wildcats in the Kuban River delta. Wildcats in the northern Caucasus feed on mouse-like rodents and edible dormice, as well as birds, young chamois and roe deer on rare occasions. Wildcats on the Black Sea coast are thought to feed on small birds, shrews, and hares. On one occasion, the feathers of a white-tailed eagle and the skull of a kid were found at a den site.[32] In Transcaucasia, the wildcat's diet consists of gerbils, voles, birds, and reptiles in the summer, and birds, mouse-like rodents, and hares in winter. Turkmenian wildcats feed on great and red-tailed gerbils, Afghan voles, thin-toed ground squirrels, tolai hares, small birds (particularly larks), lizards, beetles, and grasshoppers. Near Repetek, the wildcat is responsible for destroying over 50% of nests made by desert finches, streaked scrub warblers, red-tailed warblers, and turtledoves. In the Qarshi steppes of Uzbekistan, the wildcat's prey, in descending order of preference, includes great and red-tailed gerbils, jerboas, other rodents and passerine birds, reptiles, and insects. Wildcats in eastern Kyzyl Kum have similar prey preferences, with the addition of tolai hares, midday gerbils, five-toed jerboas, and steppe agamas. In Kyrgyzstan, the wildcat's primary prey varies from tolai hares near Issyk Kul, pheasants in the Chu and Talas River valleys, and mouse-like rodents and gray partridges in the foothills. In Kazakhstan's lower Ili River, the wildcat mainly targets rodents, muskrats, and Tamarisk jird. Occasionally, remains of young roe deer and wild boar are present in its faeces. After rodents, birds follow in importance, along with reptiles, fish, insects, eggs, grass stalks and nuts (which probably enter the cat's stomach through pheasant crops).[36] In west Africa, the wildcat feeds on rats, mice, gerbils, hares, small to medium-sized birds (up to francolins), and lizards. In southern Africa, where wildcats attain greater sizes than their western counterparts, antelope fawns and domestic stock, such as lambs and kids are occasionally targeted.[28]

Reproduction and development

The wildcat has two estrus periods, one in December–February and another in May–July.[37] Estrus lasts 5–9 days, with a gestation period lasting 60–68 days.[30] Ovulation is induced through copulation. Spermatogenesis occurs throughout the year. During the mating season, males fight viciously,[37] and may congregate around a single female. There are records of male and female wildcats becoming temporarily monogamous. Kittens are usually born between April and May, and up to August. Litter size ranges from 1–7 kittens.[30]

Kittens are born blind and helpless, and are covered in a fuzzy coat.[37] They weigh 65–163 g (2.3–5.7 oz) at birth, and kittens under 90 g (3.2 oz) usually do not survive. They are born with pink paw pads, which blacken at the age of three months, and blue eyes, which turn amber after five months.[30] Their eyes open after 9–12 days, and their incisors erupt after 14–30 days. The kittens' milk teeth are replaced by their permanent dentition at the age of 160–240 days. The kittens start hunting with their mother at the age of 60 days, and start moving independently after 140–150 days. Lactation lasts 3–4 months, though the kittens eat meat as early as 1.5 months of age. Sexual maturity is attained at the age of 300 days.[37] Similarly to the domestic cat, the physical development of African wildcat kittens over the first two weeks of their lives is much faster than that of European wildcats.[38] The kittens are largely fully grown by 10 months, though skeletal growth continues for over 18–19 months. The family dissolves after roughly five months, and the kittens disperse to establish their own territories.[30] Their maximum life span is 21 years, though they usually live up to 13–14 years.[37]

Predators and competitors

Because of its habit of living in areas with rocks and tall trees for refuge, dense thickets and abandoned burrows, wildcats have few natural predators. In Central Europe, many kittens are killed by pine martens, and there is at least one account of an adult wildcat being killed and eaten.[39] In the steppe regions of Europe and Asia, village dogs constitute serious enemies of wildcats, along with the much larger Eurasian lynx, one of the rare habitual predators of healthy adults. In Tajikistan, wolves are their most serious enemies, having been observed to destroy cat burrows. Birds of prey, including eagle-owls and saker falcons, have been known to kill wildcat kittens.[40] Seton Gordon recorded an instance where a wildcat fought a golden eagle, resulting in the deaths of both combatants.[41] In Africa, wildcats are occasionally eaten by pythons.[42] Competitors of the wildcat include the jungle cat, golden jackal, red fox, marten, and other predators. Although the wildcat and the jungle cat occupy the same ecological niche, the two rarely encounter one another, on account of different habitat preferences: jungle cats mainly reside in lowland areas, while wildcats prefer higher elevations in beech forests.[39]

Diseases and parasites

The wildcat is highly parasitised by helminths. Some wildcats in Georgia may carry five helminth species: Hydatigera taeniaeformis, Diphyllobothrium mansoni, Toxocara mystax, Capillaria feliscati and Ancylostoma caninum. Wildcats in Azerbaijan carry Hydatigera krepkogorski and T. mystax. In Transcaucasia, the majority of wildcats are infested by the tick Ixodes ricinus. In some summers, wildcats are infested with fleas of the genus Ceratophyllus, which they likely contract from brown rats.[39]

Relationships with humans

Domestication

An African wildcat skeleton excavated in a 9,500-year-old Neolithic grave in Cyprus is the earliest known indication for a close relationship between a human and a possibly tamed cat. As no cat species is native to Cyprus, this discovery indicates that Neolithic farmers may have brought cats to Cyprus from the Near East.[43] Results of genetics and morphological research corroborated that the African wildcat is the ancestor of the domestic cat. The first individuals were probably domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around the time of the introduction of agriculture.[2][16][17]

In culture

In mythology

In Celtic mythology, the wildcat was associated with rites of divination and Otherworldly encounters. Domestic cats are not prominent in Insular Celtic tradition (as housecats were not introduced to the British Isles until the Mediaeval period).[citation needed] Fables of the Cat Sìth, a fairy creature described as resembling a large white-chested black cat, are thought to have been inspired by the Kellas cat, itself thought to be a free ranging crossbreed between a European wildcat and a domestic cat.[44] In 1693, William Salmon mentioned how body parts of the wildcat were used for medicinal purposes; its flesh for treating gout, its fat for dissolving tumours and easing pain, its blood for curing "falling sickness", and its excrement for treating baldness.[45]

In heraldry

The Picts venerated wildcats, having probably named Caithness (Land of the Cats) after them. According to the foundation myth of the Catti tribe, their ancestors were attacked by wildcats upon landing in Scotland. Their ferocity impressed the Catti so much, that the wildcat became their symbol. The progenitors of Clan Sutherland use the wildcat as symbol on their family crest. The clan's chief bears the title Morair Chat (Great Man of the Cats).[46] The wildcat is considered an icon of Scottish wilderness, and has been used in clan heraldry since the 13th century. The Clan Chattan Association (also known as the Clan of Cats) comprises 12 clans, the majority of which display the wildcat on their badges.[44]

In literature

Shakespeare referenced the wildcat three times:[45]

- The patch is kind enough ; but a huge feeder

- Snail-slow in profit, and he sleeps by day

- More than the wild cat.

— The Merchant of Venice Act 2 Scene 5 lines 47–49

- Thou must be married to no man but me ;

- For I am he, am born to tame you, Kate ;

- And bring you from a wild cat to a Kate

- Comfortable, as other household Kates.

— The Taming of the Shrew Act 2 Scene 1 lines 265–268

- Thrice the brinded cat hath mew'd.

— Macbeth Act 4 Scene 1 line 1

Threats

Wildcat populations are foremost threatened by hybridization with domestic cat. Mortality due to traffic accidents is a threat especially in Europe.[1] The wildcat population in Scotland has declined since the turn of the 20th century due to habitat loss and persecution by landowners.[47]

In the former Soviet Union, wildcats were caught accidentally in traps set for European pine marten (Martes martes). In modern times, they are caught in unbaited traps on pathways or at abandoned trails of red fox, European badger, European hare or pheasant. One method of catching wildcats consists of using a modified muskrat trap with a spring placed in a concealed pit. A scent trail of pheasant viscera leads the cat to the pit. Wildcat skins were of little commercial value and sometimes converted into imitation sealskin; the fur usually fetched between 50 and 60 kopecks.[48] Wildcat skins were almost solely used for making cheap scarfs, muffs and coats for ladies. Wildcat fur is difficult to dye in dark brown or black, and has a tendency to turn green when the dye is not well settled into the hair. When dye is overly applied, wildcat fur is highly susceptible to singeing.[49]

Conservation

Wildcat species are protected in most range countries and listed in CITES Appendix II. The European wildcat is also listed in Appendix II of the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats and in the European Union's Habitats and Species Directive.[1] Conservation Action Plans have been developed in Germany and Scotland.[50][51]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A.; Driscoll, C.; Nussberger, B. (2015). "Felis silvestris". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. IUCN: e.T60354712A50652361. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en.

- ^ a b c d Driscoll, C. A.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Roca, A. L.; Hupe, K.; Johnson, W. E.; Geffen, E.; Harley, E. H.; Delibes, M.; Pontier, D.; Kitchener, A. C.; Yamaguchi, N.; O’Brien, S. J.; Macdonald, D. W. (2007). "The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication" (PDF). Science. 317 (5837): 519–523. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..519D. doi:10.1126/science.1139518. PMC 5612713. PMID 17600185.

- ^ a b Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 16−20.

- ^ a b Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Species Felis silvestris". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 536–537. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A.; Driscoll, C.; Nussberger, B. (2004). "Craniological differentiation between European wildcats (Felis silvestris silvestris), African wildcats (F. s. lybica) and Asian wildcats (F. s. ornata): implications for their evolution and conservation" (PDF). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 83: 47–63. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00372.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Pocock, R. I. (1951). "Felis silvestris, Schreber". Catalogue of the Genus Felis. London: Trustees of the British Museum. pp. 29−50.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Pocock, R. I. (1951). "Felis lybica, Forster". Catalogue of the Genus Felis. London: Trustees of the British Museum. pp. 50−133.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1972, pp. 402–403

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1972, pp. 405–407

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1972, pp. 442–450

- ^ Schauenberg, P. (1969). "L'identification du Chat forestier d'Europe Felis s. silvestris Schreber, 1777 par une méthode ostéométrique". Revue suisse de Zoologie. 76: 433−441.

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 408–409

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 452

- ^ a b Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). "Die wilde Kaze". Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen (Dritter Theil)' (in German). Erlangen: Expedition des Schreber'schen Säugthier- und des Esper'schen Schmetterlingswerkes. pp. 397–402.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Forster, G. (1780). "LIII. Der Karakal". Herrn von Buffon's Naturgeschichte der vierfüssigen Thiere. Mit Vermehrungen, aus dem Französischen übersetzt (in German). Vol. Vol. 6. Berlin: J. Pauli. pp. 304–307.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 1972, pp. 452–455

- ^ a b Clutton-Brock, J. (1999). "Cats". A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–140. ISBN 978-0-521-63495-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Satunin, K. A. (1905). "Die Säugetiere des Talyschgebietes und der Mughansteppe" [The Mammals of the Talysh area and the Mughan steppe]. Mitteilungen des Kaukasischen Museums (2): 87–402.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Rosevear74was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (1997). "Phylogenetic Reconstruction of the Felidae Using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 Mitochondrial Genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 44 (S1): S98–S116. Bibcode:1997JMolE..44S..98J. doi:10.1007/PL00000060. PMID 9071018.

- ^ Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The Late Miocene Radiation of Modern Felidae: A Genetic Assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- ^ Kurtén, B. (1965). "On the evolution of the European Wild Cat, Felis silvestris Schreber" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Fennica. 111: 3–34.

- ^ Mattucci, F.; Oliveira, R.; Bizzarri, L.; Vercillo, F.; Anile, S.; Ragni, B.; Lapini, L.; Sforzi, A.; Alves, P. C.; Lyons, L. A.; Randi, E. (2013). "Genetic structure of wildcat (Felis silvestris) populations in Italy". Ecology and Evolution. 3 (8): 2443–2458. doi:10.1002/ece3.569.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "African Wildcat Felis silvestris, lybica group (Forster, 1770)". Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 32−35.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) Archived 2012-11-29 at the Wayback Machine - ^ a b Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 403

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 432–433

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 433–434

- ^ a b Rosevear 1974, pp. 388

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 432

- ^ a b c d e Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 404

- ^ Kingdon 1988, pp. 314

- ^ a b c d Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 429–431

- ^ Tomkies 1987, pp. 50

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 480

- ^ Hobson, K. J. (2012). An investigation into prey selection in the Scottish wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris). Doctoral dissertation. London: Department of Life Sciences, Silwood Park, Imperial College London. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.704.4705.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 476–481

- ^ a b c d e Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 434–437

- ^ Hemmer 1990, pp. 47

- ^ a b c Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 438

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 491–493

- ^ Watson, J. (2010). The Golden Eagle. pp. 306. A&C Black. ISBN 1408114208

- ^ Kingdon 1988, pp. 316

- ^ Vigne, J. D.; Guilaine, J.; Debue, K.; Haye, L.; Gérard, P. (2004). "Early taming of the cat in Cyprus". Science. 304 (5668): 259. doi:10.1126/science.1095335. PMID 15073370.

- ^ a b Kilshaw 2011, pp. 2–3

- ^ a b Hamilton 1896, pp. 17–18

- ^ Vinycomb, J. (1906). "Cat-a-Mountain − Tiger Cat or Wild Cat". Fictitious & symbolic creatures in art, with special reference to their use in British heraldry. London: Chapman and Hall Limited. pp. 205−208.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Macdonald, D. W.; Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A. C.; Daniels, M.; Kilshaw, K.; Driscoll, C. (2010). "Reversing cryptic extinction: the history, present and future of the Scottish Wildcat". In Macdonald, D. W.; Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). The Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 471–492. ISBN 9780199234448.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1972, pp. 440–441 & 496–498

- ^ Bachrach, M. (1953). "Cat family − Lynx Cat and Wild Cat". Fur, a practical treatise (Third ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall Incorporated. pp. 188–189.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Vogel, B.; Mölich, T.; Klar, N. (2009). "Der Wildkatzenwegeplan – Ein strategisches Instrument des Naturschutzes" [The Wildcat Infrastructure Plan – a strategic instrument of nature conservation] (PDF). Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung. 41 (11): 333–340.

- ^ Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Group (2013). Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan. Edinburgh: Scottish Natural Heritage.

Further reading

- Hamilton, E. (1896). The wild cat of Europe (Felix catus). London: R. H. Porter.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harris, S.; Yalden, D. W. (2008). Mammals of the British Isles (4th Revised ed.). Southampton: Mammal Society. ISBN 978-0906282656.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hemmer, H. (1990). Domestication: the decline of environmental appreciation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521341783.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Wildcat". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 398–498.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kilshaw, K. (2011). Scottish Wildcats: Naturally Scottish (PDF). Perth, Scotland: Scottish Natural Heritage. ISBN 9781853976834. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kingdon, J. (1988). East African mammals: an atlas of evolution in Africa. Volume 3, Part 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226437217.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kurtén, B. (1968). Pleistocene mammals of Europe. New Brunswick and London: Aldine Transaction. ISBN 9781412845144.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Osborn, D. J.; Helmy, I. (1980). The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai). Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosevear, D. R. (1974). The carnivores of West Africa. London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). ISBN 978-0565007232.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tomkies, M. (2008). Wildcat Haven. Dunbeath: Whittles Publishing. ISBN 9781849953122.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: European Wildcat

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Chinese Mountain Cat

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Asiatic Wildcat

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: African Wildcat

- UNEP Global Resource Information Database: Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777

- ARKive: Wildcat (Felis silvestris)

- Envis Centre of Faunal diversity: Felis silvestris (Schreber)

- Digimorph.org: Felis silvestris lybica, African Wildcat 3D computed tomographic (CT) animations of male and female African wild cat skulls

- Scottish wildcat

- Save the Scottish Wildcat information and education website on the Scottish wildcat and conservation efforts

- Wildcat Haven– a Community Interest Company dedicated to conserving the Scottish wildcat in the West Highlands