Notre-Dame de Paris

This article may be affected by the following current event: Notre-Dame de Paris fire. Information in this article may change rapidly as the event progresses. Initial news reports may be unreliable. The last updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (April 2019) |

| Notre-Dame de Paris | |

|---|---|

| Our Lady of Paris | |

| |

| 48°51′11″N 2°20′59″E / 48.8530°N 2.3498°E | |

| Location | Parvis Notre-Dame – place Jean-Paul-II, Paris, France |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Unknown (Fire damage) |

| Style | French Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1163 |

| Completed | 1345 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 128 metres (420 ft) |

| Width | 48 metres (157 ft) |

| Number of towers | 2 |

| Tower height | 69 metres (226 ft) |

| Number of spires | 1 (destroyed by fire) |

| Spire height | (formerly)[1] 90 metres (300 ft) |

| Bells | 10 |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Paris |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Michel Aupetit |

| Rector | Patrick Jacquin |

| Dean | Patrick Chauvet |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Sylvain Dieudonné[2] |

| Official name | Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris |

| Type | Cathédrale |

| Designated | 1862[3] |

| Reference no. | PA00086250 |

Notre-Dame de Paris (/ˌnɒtrə ˈdɑːm, ˌnoʊtrə ˈdeɪm, ˌnoʊtrə ˈdɑːm/;[4][5][6] French: [nɔtʁə dam də paʁi] ; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), also known as Notre-Dame Cathedral or simply Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité in the fourth arrondissement of Paris, France.[7] The cathedral is considered to be one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture. The innovative use of the rib vault and flying buttress, the enormous and colorful rose windows, and the naturalism and abundance of its sculptural decoration all set it apart from earlier Romanesque architecture.[8]

The cathedral was begun in 1160 and largely completed by 1260, though it was modified frequently in the following centuries. In the 1790s, Notre-Dame suffered desecration during the French Revolution when much of its religious imagery was damaged or destroyed. Soon after the publication of Victor Hugo's novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1831, popular interest in the building revived. A major restoration project supervised by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc began in 1845 and continued for twenty-five years. Beginning in 1963, the facade of the cathedral was cleaned of centuries of soot and grime, returning it to its original color. Another campaign of cleaning and restoration was carried out from 1991–2000.[9]

As the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Paris, Notre-Dame contains the cathedra of the Archbishop of Paris (Michel Aupetit). 12 million people visit Notre-Dame yearly, it thus being the most visited monument in Paris.[10]

On 15 April 2019, the cathedral caught fire and suffered significant damage, including the collapse of the entire roof and the main spire and substantial damage to the rose windows.[1]

History of the church

Construction

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris was built on a site which in Roman Lutetia is believed to have been occupied by a pagan temple, thence by a Romanesque church, the Basilica of Saint Étienne, built between the 4th century and 7th century. The basilica was situated about 40 meters west of the cathedral and was wider and lower and roughly half its size.[9]

King Louis VII of France (reigned 1137–1180) wanted to build monuments to show that Paris was the political, economic, and cultural capital of France. In this context, Maurice de Sully, who had been elevated Bishop in 1160, had the old basilica torn down to its foundations, and began to build a larger and taller cathedral.

The cornerstone was laid in 1163 in the presence of Pope Alexander III. The design followed the traditional plan, with the ambulatory and choir, where the altar was located, to the east, and the entrance, facing the setting sun, to the west. By long tradition, the choir, where the altar was located, was constructed first, so that the church could be consecrated and used long before it was completed. The original plan was for a long nave, four levels high, with no transept. The flying buttress was not yet in use, so the walls were thick and reinforced by solid stone abutments placed against them on the outside, and later by chapels placed between the abutments.

The roof of the nave was constructed with a new technology, the rib vault, which had earlier been used in the Basilica of Saint Denis. The roof of the nave was supported by crossed ribs which divided each vault into six compartments. The pointed arches were stronger than the earlier Romanesque arches, and carried the weight of the roof outwards and downwards to rows of pillars, and out to the abutments against the walls. Construction of the choir took from 1163 until around 1177. The High Altar was consecrated in 1182. Between 1182 and 1190 the first three traverses of the nave were built up to the level of tribunes. Beginning in 1190, the bases of the facade were put in place, and the first traverses were completed.[9]

The decision was made to add a transept at the choir, where the altar was located, in order to bring more light into the center of the church. The use of simpler four-part rather than six-part rib vaults meant that the roofs were stronger and could be higher. After Bishop Maurice de Sully's death in 1196, his successor, Eudes de Sully (unrelated to the previous Bishop) oversaw the completion of the transepts, and continued work on the nave, which was nearing completion at the time of his own death in 1208. By this time, the western facade was already largely built, though it was not completed until around the mid-1240s. Between 1225 and 1250 the upper gallery of the nave was constructed, along with the two towers on the west facade.[11]

Another significant change came in the mid 13th century, when the transepts were remodeled in the latest Rayonnant style; in the late 1240s Jean de Chelles added a gabled portal to the north transept topped off by a spectacular rose window. Shortly afterwards (from 1258) Pierre de Montreuil executed a similar scheme on the southern transept. Both these transept portals were richly embellished with sculpture; the south portal features scenes from the lives of St Stephen and of various local saints, while the north portal featured the infancy of Christ and the story of Theophilus in the tympanum, with a highly influential statue of the Virgin and Child in the trumeau.[12][11]

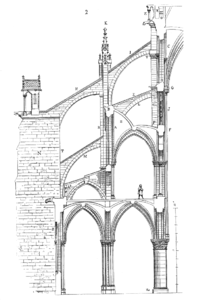

An important innovation in the 13th century was the introduction of the flying buttress. Before the buttresses, all of the weight of the roof pressed outward and down to the walls, and the abutments supporting them. With the flying buttress, the weight was carried by the ribs of the vault entirely outside the structure to a series of counter-supports, which were topped with stone pinnacles which gave them greater weight. The buttresses meant that the walls could be higher and thinner, and could have much larger windows. The date of the first buttresses is not known with any precision; they were installed some time in the 13th century. The first buttresses were replaced by larger and stronger ones in the 14th century; these had a reach of fifteen meters between the walls and counter-supports.[9]

Timeline of construction

- 1160 Maurice de Sully (named Bishop of Paris) orders the original cathedral demolished.

- 1163 Cornerstone laid for Notre-Dame de Paris; construction begins.

- 1182 Apse and choir completed.

- 1196 Bishop Maurice de Sully dies.

- c.1200 Work begins on western facade.

- 1208 Bishop Eudes de Sully dies. Nave vaults nearing completion.

- 1225 Western facade completed.

- 1250 Western towers and north rose window completed.

- c.1245–1260s Transepts remodelled in the rayonnant style by Jean de Chelles then Pierre de Montreuil.

- 14th century New flying buttresses added to apse and choir.

-

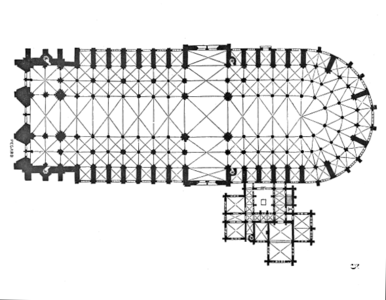

Plan of the Cathedral made by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th century. Portals and nave to the left, choir in the center, and apse and ambulatory to the right.

-

Early six-part rib vaults of the nave. The ribs transferred the thrust of the weight of the roof downward and outwards to the pillars and the supporting buttresses.

-

Cross-section of the double supporting arches and buttresses of the nave (13th century) drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

-

The massive buttresses which counter the outward thrust from the rib vaults of the nave

-

Later flying buttresses of the apse of Notre-Dame (14th century) reached 15 meters from the wall to the counter-supports.

Modern history

In 1548, rioting Huguenots damaged some of the statues of Notre-Dame, considering them idolatrous.[13] During the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV, the cathedral underwent numerous alterations to comply with the more classical style of the period. The sanctuary was re-arranged; the choir was largely rebuilt in marble, and many of the stained glass windows from the 12th and 13th century were removed and replaced with white glass windows, to bring more light into the church. A colossal statue of St Christopher, standing against a pillar near the western entrance and dating from 1413, was destroyed in 1786. The spire, which had been damaged by the wind, was removed in the second part of the 18th century.

In 1793, during the French Revolution, the cathedral was rededicated to the Cult of Reason, and then to the Cult of the Supreme Being. During this time, many of the treasures of the cathedral were either destroyed or plundered. The twenty-eight statues of biblical kings located at the west facade, mistaken for statues of French kings, were beheaded.[14] Many of the heads were found during a 1977 excavation nearby, and are on display at the Musée de Cluny. For a time the Goddess of Liberty replaced the Virgin Mary on several altars.[15] The cathedral's great bells escaped being melted down. All of the other large statues on the facade, with the exception of the statue of the Virgin Mary on the portal of the cloister, were destroyed.[9] The cathedral came to be used as a warehouse for the storage of food and other non-religious purposes.[13]

In July 1801, the new ruler, Napoleon Bonaparte, signed an agreement to restore the cathedral to the Church. It was formally transferred on 18 April 1802. It was the setting of Napoleon's coronation as Emperor on 2 December 1804, and of his marriage to Marie-Louise of Austria in 1810.

The cathedral was functioning in the early 19th century, but was half-ruined inside and battered without. In 1831, the novel Notre-Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo, published in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame had an enormous success, and brought the cathedral new attention. In 1844 King Louis Philippe ordered that the church be restored. The commission for the restoration was won by two architects, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who was then just 31 years old. They supervised a large team of sculptors, glass makers and other craftsmen who remade, working from drawings or engravings, the original decoration, or, if they did not have a model, adding new elements they felt were in the spirit of the original style. They made a taller and more ornate reconstruction of the original spire (including a statue of Saint Thomas that resembles Viollet-le-Duc), as well as adding the sculpture of mythical creatures on the Galerie des Chimères. The restoration lasted twenty five years.[13]

During the liberation of Paris in August 1944, the cathedral suffered some minor damage from stray bullets. Some of the medieval glass was damaged, and was replaced by glass with modern abstract designs. On 26 August, a special mass was held in the cathedral to celebrate the liberation of Paris from the Germans; it was attended by General Charles De Gaulle and General Philippe Leclerc.

In 1963, on the initiative of culture minister André Malraux and to mark the 800th anniversary of the Cathedral, the facade was cleaned of the centuries of soot and grime, restoring it to its original off-white color.[16]

Stones damaged by air pollution were replaced, and a discreet system of electrical wires, not visible from below, was installed on the roof to deter pigeons. Another major cleaning and restoration program was commenced in 1991.

Fire

On 15 April 2019 at 18:50 local time, the cathedral caught fire, causing the collapse of the spire and the roof.[17][18][1] The extent of the damage was initially unknown as was the cause of the fire, though it was suggested that it was linked to ongoing renovation work.[18][17] A spokesperson stated that the entire wooden frame would likely come down and that the vault of the edifice could be threatened as well.[19]

Towers and the spire

-

Towers on west facade. (1220-1250). The north tower (left) is slightly larger.

-

Spire of the cathedral, originally in place 13th-18th century, recreated in the 19th century, destroyed in a 2019 fire

-

Former spire viewed from above

-

Statue of Thomas the Apostle, with the features of restorer Viollet-le-Duc, at the base of the spire

The two towers are sixty-nine metres high, and were the tallest structures in Paris until the completion of the Eiffel Tower in 1889. The towers were the last major element of the Cathedral to be constructed. The south tower was built first, between 1220 and 1240, and the north tower between 1235 and 1250. The newer north tower is slightly larger, as can be seen when they viewed from directly in front of the church. The contrefort or buttress of the north tower is also larger.[20]

The north tower is accessible to visitors by a stairway, whose entrance is on the north side of the tower. The stairway has 387 steps, and has a stop at the Gothic hall at the level of the rose window, where visitors can look over the parvis and see a collection of paintings and sculpture from earlier periods of the Cathedral's history.

The ten bells of the Cathedral are located in the south tower. (see Bells below)

A water reservoir, covered with a lead roof, is located between the two towers, behind the colonnade and the gallery and in front of the nave and the pignon. It can be used to quickly extinguish a fire.

The Cathedral's flèche or spire, which was destroyed in the April 2019 fire,[21] was located over the transept and altar. The original spire was constructed in the 13th century, probably between 1220 and 1230. It was battered, weakened and bent by the wind over five centuries, and finally was removed in 1786. During the 19th century restoration, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc decided to recreate it, making a new version of oak covered with lead. The entire spire weighed 750 tons.

Following Viollet-le-Duc's plans, the spire was surrounded by copper statues of the twelve Apostles, in four groups of three, one group at each point of the compass. Each of the four groups were preceded by an animal symbolising one of the four evangelists: a steer for Saint Luke, a lion for Saint Mark, an eagle for Saint John and an angel for Saint Matthew. Just days prior to the spire's collapse, all of the statues were removed for restoration.[22] While in place, they had faced at Paris, except one; the statue of Saint Thomas, the patron saint of architects, faced the spire, and had the features of Viollet-le-Duc.

The rooster at the summit of the spire contained three relics; a tiny piece of the Crown of Thorns, located in the treasury of the Cathedral; and relics of Denis and Saint Genevieve, patron saints of Paris. They were placed there in 1935 by the Archibishop Jean Verdier, to protect the congregation from lightning or other harm.

Iconography — the "poor people's book"

-

Illustration of the Last Judgement, central portal of west facade

-

The martyr Saint Denis, holding his head, over the Portal of the Virgin

-

The serpent tempts Adam and Eve; part of the Last Judgement on the central portal of west facade

-

Archangel Michael and Satan weighing souls during the Last Judgement (central portal, west facade)

-

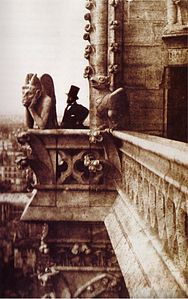

A stryge on west facade

-

Gargoyles were the rainspouts of the Cathedral

-

Chimera on the facade

-

Allegory of alchemy, central portal

The Gothic cathedral was a liber pauperum, a "poor people's book", covered with sculpture vividly illustrating biblical stories, for the vast majority of parishioners who were illiterate. To add to the effect, all of the sculpture on the facades was originally painted and gilded.[23] The tympanum over the central portal on the west facade, facing the square, vividly illustrates the Last Judgement, with figures of sinners being led off to hell, and good Christians taken to heaven. The sculpture of the right portal shows the coronation of the Virgin Mary, and the left portal shows the lives of saints who were important to Parisians, particularly Saint Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary.[24]

The exteriors of cathedrals and other Gothic churches were also decorated with sculptures of a variety of fabulous and frightening grotesques or monsters. These included the gargoyle, the chimera, a mythical hybrid creature which usually had the body of a lion and the head of a goat, and the Strix or stryge, a creature resembling an owl or bat, which was said to eat human flesh. The strix appeared in classical Roman literature; it was described by the Roman poet Ovid, who was widely read in the Middle Ages, as a large-headed bird with transfixed eyes, rapacious beak, and greyish white wings.[25] They were part of the visual message for the illiterate worshipers, symbols of the evil and danger that threatened those who did not follow the teachings of the church.[26]

The gargoyles, which were added in about 1240, had a more practical purpose. They were the rain spouts of the cathedral, designed to divide the torrent of water which poured from the roof after rain, and to project it outwards as far as possible from the buttresses and the walls and windows where it might erode the mortar binding the stone. To produce many thin streams rather than a torrent of water, a large number of gargoyles were used, so they were also designed to be a decorative element of the architecture. The rainwater ran from the roof into lead gutters, then down channels on the flying buttresses, then along a channel cut in the back of the gargoyle and out of the mouth away from the cathedral.[23]

Amid all the religious figures, some of the sculptural decoration was devoted to illustrating medieval science and philosophy. The central portal of the west facade is decorated with carved figures holding circular plaques with symbols of transformation taken from alchemy. The central pillar of the central door of Notre-Dame features a statue of a woman on a throne holding a scepter in her left hand, and in her right hand, two books, one open (symbol of public knowledge), and the other closed (esoteric knowledge), along with a ladder with seven steps, symbolizing the seven steps alchemists followed in their scientific quest of trying to transform ordinary metals into gold.[26]

Many of the statues, particularly the grotesques, were removed from facade in the 17th and 18th century, or were destroyed during the French Revolution. They were replaced with figures in the Gothic style, designed by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, during the 19th century restoration.

Stained glass — rose windows

-

The earliest rose window, on the west facade (about 1225)

-

The west Rose window (about 1225)

-

North rose window (about 1250)

-

South rose window (about 1260)

The stained glass windows of Notre-Dame, particularly the three rose windows, are among the most famous features of the cathedral. The west rose window, over the portals, was the first and smallest of the roses in Notre-Dame. It is 9.6 meters in diameter, and was made in about 1225, with the pieces of glass set in a thick circular stone frame. None of the original glass remains in this window; it was recreated in the 19th century.[27]

The two transept windows are larger and contain a greater proportion of glass than the rose on the west facade, because the new system of buttresses made the nave walls thinner and stronger. The north rose was created in about 1250, and the south rose in about 1260. The south rose in the transept is particularly notable for its size and artistry. It is 12.9 meters in diameter; with the claire-voie surrounding it, a total of 19 meters. It was given to the Cathedral by King Louis IX of France, known as Saint Louis.[28]

The south rose has 94 medallions, arranged in four circles, depicting scenes from the life of Christ and those who witnessed his time on earth. The inner circle has twelve medallions showing the twelve apostles. (During later restorations, some of these original medallions were moved to circles farther out). The next two circles depict celebrated martyrs and virgins. The fourth circle shows twenty angels, as well as saints important to Paris, notably Saint Denis, Margaret the Virgin with a dragon, and Saint Eustace. The third and fourth circles also have some depictions of Old Testament subjects. The third circle has some medallions with scenes from the New Testament Gospel of Matthew which date from the last quarter of the 12th century. These are the oldest glass in the window.[28]

Additional scenes in the corners around the rose window include Jesus' Descent into Hell, Adam and Eve, the Resurrection of Christ. Saint Peter and Saint Paul are at the bottom of the window, and Mary Magdalene and John the Apostle at the top.

Above the rose is a window depicting Christ triumphant seated in the sky, surrounded by his Apostles. Below are sixteen windows with painted images of Prophets. These were not part of the original window; they were painted during the restoration in the 19th century by Alfred Gérenthe, under the direction of Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, based upon a similar window at Chartres Cathedral.[28]

The south rose had a difficult history. In 1543 it was damaged by the settling of the masonry walls, and not restored until 1725–1727. It was seriously damaged in the French Revolution of 1830. Rioters burned the residence of the archbishop, next to the cathedral, and many of the panes were destroyed. The window was entirely rebuilt by Viollet-le-Duc in 1861. He rotated the window by fifteen degrees to give it a clear vertical and horizontal axis, and replaced the destroyed pieces of glass with new glass in the same style. The window today contains both medieval and 19th century glass.[28]

In the 1960s, after three decades of debate, it was decided to replace many of the 19th-century grisaille windows in the nave designed by Viollet-le-Duc with new windows. The new windows, made by Jacques Le Chevallier, are without human figures and use abstract grisaille designs and color to try to recreate the luminosity in the Cathedral in the 13th century.

Crypt

The Archaeological Crypt (Crypte archéologique de l'île de la Cité) was created in 1965 to protect a range of historical ruins, discovered during construction work and spanning from the earliest settlement in Paris to the modern day. The crypt is managed by the Musée Carnavalet, and contains a large exhibit, detailed models of the architecture of different time periods, and how they can be viewed within the ruins. The main feature still visible is the under-floor heating installed during the Roman occupation.[29]

Contemporary critical reception

John of Jandun recognized the cathedral as one of Paris's three most important buildings [prominent structures] in his 1323 Treatise on the Praises of Paris:

That most glorious church of the most glorious Virgin Mary, mother of God, deservedly shines out, like the sun among stars. And although some speakers, by their own free judgment, because [they are] able to see only a few things easily, may say that some other is more beautiful, I believe however, respectfully, that, if they attend more diligently to the whole and the parts, they will quickly retract this opinion. Where indeed, I ask, would they find two towers of such magnificence and perfection, so high, so large, so strong, clothed round about with such a multiple variety of ornaments? Where, I ask, would they find such a multipartite arrangement of so many lateral vaults, above and below? Where, I ask, would they find such light-filled amenities as the many surrounding chapels? Furthermore, let them tell me in what church I may see such a large cross, of which one arm separates the choir from the nave. Finally, I would willingly learn where [there are] two such circles, situated opposite each other in a straight line, which on account of their appearance are given the name of the fourth vowel [O] ; among which smaller orbs and circlets, with wondrous artifice, so that some arranged circularly, others angularly, surround windows ruddy with precious colors and beautiful with the most subtle figures of the pictures. In fact I believe that this church offers the carefully discerning such cause for admiration that its inspection can scarcely sate the soul.

— Jean de Jandun, Tractatus de laudibus Parisius[30]

Organ

One of the earliest organs at Notre-Dame, built in 1403 by Friedrich Schambantz, was replaced between 1730 and 1738 by François Thierry. During the restoration of the cathedral by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll built a new organ; using pipe work from the former instruments. The organ was dedicated in 1868. In 1904, Charles Mutin modified and added several stops; in 1924, an electric blower was installed. An extensive restoration and cleaning was carried out by Joseph Beuchet in 1932. Between 1959 and 1963, the mechanical action with barker machines was replaced by an electric action by Jean Hermann, and a new organ console was installed. During the following years, the stoplist was gradually modified by Robert Boisseau (who added three chamade stops 8', 4', and 2'/16' in 1968) and Jean-Loup Boisseau after 1975, respectively. In fall 1983, the electric combination system was disconnected due to short-circuit risk. Between 1990 and 1992, Jean-Loup Boisseau, Bertrand Cattiaux, Philippe Émeriau, Michel Giroud, and the Société Synaptel revised and augmented the instrument throughout. A new console was installed, using the stop knobs, pedal and manual keyboards, foot pistons and balance pedals from the Jean Hermann console. Between 2012 and 2014, Bertrand Cattiaux and Pascal Quoirin restored, cleaned, and modified the organ. The stop and key action was upgraded, a new console was built, (again using the stop keys, pedal board, foot pistons and balance pedals of the 1992 console), a new enclosed division ("Résonnance expressive", using pipework from the former "Petite Pédale" by Boisseau, which can now be used as a floating division), the organ case and the facade pipes were restored, and a general tuning was carried out. The current organ has 115 stops (156 ranks) on five manuals and pedal, and more than 8,000 pipes.

Organ and organists

| I. Grand-Orgue C–g3 |

II. Positif C–g3 |

III. Récit C–g3 |

IV. Solo C–g3 |

V. Grand-Chœur C–g3 |

Pédale C–f1 |

Résonnance expressive C–g3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Violon Basse 16 Chamades: Chamade REC 8 |

Montre 16 |

Récit expressif: Récit classique: Chamades: Basse Chamade GO 8 Trémolo |

Bourdon 32 Chamade GO 8 Cornet REC |

Principal 8 |

Principal 32 Chamade GO 8 |

Bourdon 16 Chimes |

Couplers: II/I, III/I, IV/I, V/I; III/II, IV/II, V/II; IV/III, V/III; V/IV, Octave grave général, inversion Positif/Grand-orgue, Tirasses (Grand-orgue, Positif, Récit, Solo, Grand-Chœur en 8; Grand-Orgue en 4, Positif en 4, Récit en 4, Solo en 4, Grand-Chœur en 4), Sub- und Super octave couplers and Unison Off for all manuals (Octaves graves, octaves aiguës, annulation 8'). Octaves aiguës Pédalier. Additional features: Coupure Pédalier. Coupure Chamade. Appel Résonnance. Sostenuto for all manuals and the pedal. Cancel buttons for each division. 50,000 combinations (5,000 groups each). Replay system.

Organists

The position of titular organist ("head" or "chief" organist; French: titulaires des grands orgues) at Notre-Dame is considered one of the most prestigious organist posts in France, along with the post of titular organist of Saint Sulpice in Paris, Cavaillé-Coll's largest instrument.

- Guillaume Maingot (1600–1609)

- Jean-Jacques Petitjean (1609–1610)

- Charles Thibault (1610–1616)

- Charles Racquet (1618–1643)

- Jean Racquet (ca. 1643–1689)

- Médéric Corneille (1689–1730)

- Guillaume-Antoine Calvière (1730–1755)

- René Drouard de Bousset (1755–1760)

- Charles Alexandre Jolage (1755–1761)

- Louis-Claude Daquin (1755–1772)

- Armand-Louis Couperin (1755–1789)

- Claude Balbastre (1760–1793)

- Pierre-Claude Fouquet (1761–1772)

- Nicholas Séjan (1772–1793)

- Claude-Étienne Luce (1772–1783)

- Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier (1783–1793)

- Antoine Desprez (1802–1806)

- M.-S. Blin (1806–1834)

- Joseph Pollet (1834–1840)

- Félix Danjou (1840–1847)

- Eugène Sergent (1847–1900)

- Louis Vierne (1900–1937)

- Léonce de Saint-Martin (1937–1954)

- Pierre Cochereau (1955–1984)

- Yves Devernay (1985–1990)

- Jean-Pierre Leguay (1985–2015)

- Philippe Lefebvre (since 1985)

- Olivier Latry (since 1985)

- Vincent Dubois (since 2016)

Bells

Not to be confused with the Disney song.

The cathedral has 10 bells, the bourdon called Emmanuel, which is tuned to F sharp, has been an accompaniment to some of the most major events in the history of France ever since it was first cast, such as for the Te Deum for the coronation of French kings along with major events like the visit of the Pope, and others to mark the end of conflicts including World War I and World War II. It also rings in times of sorrow and drama to unite believers at the Notre Dame Cathedral, like for the funerals of the French heads of state, massacres like such as the September 11th Twin Towers incident and it is reserved for the Cathedral's special occasions like Christmas, Easter, and Ascension. This particular bell was the masterpiece of the whole group of bells that weighs in at 13 tons, and fortunately, it was saved from the devastation that arose during the French Revolution. According to bell ringers and musicians, it is still one of the most beautiful sound vessels and one of the most remarkable in Europe. The bell dates from the 15th century and was recast in 1681 upon the request of King Louis XIV who named it the Emmanuel Bell. There were also four bells that replaced those destroyed in the French revolution. Placed at the top of the North Tower in 1856, these ring daily for basic services, the Angelus and the chiming of the hours. The first of these bells, named Angélique-Françoise, weighs in at 1,915kg and is tuned to C sharp; the next bell is named Antoinette-Charlotte, weighing in at 1,335kg and tuned to D sharp. Then there is the bell named Jacinthe-Jeanne weighing in at 925kg tuned to F and the fourth bell named Denise-David weighs 767kg and just like the Grand Bell Emmanuel, it is tuned to F sharp. A few years later, in 1867 a carillon of three bells in the spire with two chimes that linked to the monumental clock were put in place and another three bells were positioned in the actual structure of the Notre Dame Cathedral itself, so that they could be heard inside. However, unfortunately, these are at present mute, although a project is currently being looked at, and hopefully will be put into place, in order to restore the Carillon to its former glory. Sadly, the four bells that were put in place in 1856 are now stored, as of February 2012.

About a year later, a new set of eight bells for the North Tower of Notre Dame Cathedral was being produced, along with a Grand Bell for the South Tower, just as there were originally before most were destroyed during the French Revolution. The construction of bells is one of accuracy and precision to obtain the desired sound and the work has been entrusted to two separate companies, one in France for the eight bells and one in Belgium for the Grand Bell. Each of the new bells is named with names that have been chosen to pay tribute to saints and others that have shaped the life of Paris and the Notre Dame Cathedral.

Emmanuel is accompanied by another large bell in the south tower called Marie. At six tonnes and playing a G Sharp, Marie is the second largest bell in the cathedral. Marie is also called a Little Bourdon (petite bourdon) or a drone bell because it is located alongside Emmanuel in the south tower. Built in a foundry in The Netherlands, it has engravings as a most distinctive feature, something which is different compared to the other bells. The phrases “Je vous salue Marie,” in French, and “Via viatores quaerit,” in Latin, which mean ”Hail Mary” (where the bell get is name from the Virgin Mary) and ”The way is looking for travellers”. Below the phrase appears an image of the Baby Jesus and his parents surrounded by stars and a relief with the Adoration of the Magi. It is in charge of the Small Solennel, which is similar to the Great Solennel except that the ringing peal starts with the bourdon and the eight bells in the north tower. This ring is heard on only January 1st (New Year Day) at the stroke of midnight and it replaces Emmanuel for international events. Like Emmanuel, the bells are used to mark specific moments such as the arrival at the Cathedral of the body of the deceased Archbishop of Paris.

In the North Tower, there are eight bells varying in size from largest to smallest. Gabriel is the largest bell there; it weighs four tons and plays an A sharp. It is named after St. Gabriel, who announced the birth of Jesus to the Virgin Mary. Built in a bell foundry outside Paris in 2013, it also chimes the hour through the day. Like Emmanuel and Marie, Gabriel is used to mark specific events. It is used mainly for masses on Sundays in ordinary times and some solemnities falling during the week in the Plenum North. It shows 40 circular lines representing the 40 days Jesus spent in the desert and the 40 years of Moses' crossing the Sinai.

Anne-Geneviève is the second largest bell in the North Tower and the fourth largest bell in the cathedral. Named after two saints: St. Anne, Mary’s mother, and St. Geneviève the patron saint of Paris, it plays a B and it weighs three tons. It has three circular lines that represent the Holy Trinity and three theological virtues. Like Emmanuel, Marie and Gabriel. Anne-Genevieve is used to mark specific moments such as the opening of the doors to the Palm Sunday mass or the body of the deceased Archbishop of Paris. Also it is the only bell that does not participate in a chime called the Angelus Domini, which happens in the summer at 8am, noon and 8pm (or 9am, noon and 9pm).

Denis is the third largest bell in the North Tower and fifth largest bell in the cathedral. It is named after St. Denis, the martyr who was also the first bishop of Paris around the year 250 and weighing 2 tons, it plays a C sharp. This bell includes the third phrase of the Angelus, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord”. There are also seven circular lines representing the gifts of the Holy Spirit and the seven Sacraments.

Marcel is the fourth largest bell in the North Tower and sixth largest bell in the cathedral. It is named after the 9th bishop of Paris. It plays a D sharp and weighs 1.9 tons. It is named after Saint Marcel, the ninth bishop of Paris, known for his tireless service to the poor and sick in the fifth century. The bell that bears his name as a tribute has engraved upon it the fourth sentence of the Angelus, “Be it done unto me according to Thy word”.

Étienne is the fifth largest bell in the North Tower and seventh largest bell in the cathedral. It is named after St. Stephan in English, but citizens of Paris call it by its French equivalent Étienne. It plays a E sharp and it weighs 1.5 tons. Its most prominent features is that there is a gold stripe slightly above the nameplate.

Benoît-Joseph is the sixth largest bell in the North Tower and eighth largest bell in the cathedral. Just like Anne-Geneviève, it is named after two saints. Benoît is in honour of Pope Benedict XVI of Vatican City, while Joseph is honor of Joseph Ratzinger which is his real name (2005–2013). It plays an F and weighs 1.3 tons. It has two silver stripes above the skirt and one silver stripe above the name plate. This bell is used for weddings and sometimes chimes the hour replacing Gabriel, most likely on a chime called the Ave Maria.

Maurice is the seventh largest bell in the North Tower and second smallest in the cathedral. It is named after Maurice de Sully, the bishop of Paris who laid the first stone, in 1163, for the construction of the Cathedral. It includes the inscription, “Pray for us, Holy Mother of God". It plays a G sharp and weighs one ton. It has two gray stripes below the nameplate. This bell is used for weddings.

Jean Marie is the smallest bell of the cathedral. Unlike Benoît-Joseph and Anne-Geneviève which have two names, it is named after Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, Paris' bishop from 1981 until 2005, and on it is engraved the eighth and last sentence of the Angelus: “that we might be made worthy of the promises of Christ”. It plays an A sharp and weighs 0.780 tons. It has a small gray stripe above the skirt. This bell is also used for weddings.

| Name | Mass | Diameter | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emmanuel | 13271 kg | 261 cm | F♯2 |

| Marie | 6023 kg | 206.5 cm | G♯2 |

| Gabriel | 4162 kg | 182.8 cm | A♯2 |

| Anne Geneviève | 3477 kg | 172.5 cm | B2 |

| Denis | 2502 kg | 153.6 cm | C♯3 |

| Marcel | 1925 kg | 139.3 cm | D♯3 |

| Étienne | 1494 kg | 126.7 cm | E♯3 |

| Benoît-Joseph | 1309 kg | 120.7 cm | F♯3 |

| Maurice | 1011 kg | 109.7 cm | G♯3 |

| Jean-Marie | 782 kg | 99.7 cm | A♯3 |

Ownership

Under a 1905 law, Notre-Dame de Paris is among seventy churches in Paris built before that year that are owned by the French State. While the building itself is owned by the state, the Catholic Church is the designated beneficiary, having the exclusive right to use it for religious purpose in perpetuity. The archdiocese is responsible for paying the employees, security, heating and cleaning, and assuring that the cathedral is open free to visitors. The archdiocese does not receive subsidies from the French State.[32]

Events in the Cathedral

-

Henry VI of England is crowned King of France at Notre-Dame (16 December 1431) during the Hundred Years' War

-

A Te Deum in the Choir of the Church in 1669, in reign of Louis XIV. The choir was redesigned make room for more lavish ceremonies.

-

Cult of Reason is celebrated at Notre-Dame during the French Revolution (1793).

-

The coronation of Napoleon I, on 2 December 1804 at Notre-Dame, as portrayed in the 1807 painting The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David

- 1170: Existence of a cathedral school operating at Notre-Dame. This corporation of teachers and students will evolve in 1200 into the University of Paris in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste.

- 1185: Heraclius of Caesarea calls for the Third Crusade from the still-incomplete cathedral.

- 1239: The Crown of Thorns is placed in the cathedral by St. Louis during the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle.

- 1302: Philip the Fair opens the first Estates General.

- 16 December 1431: Henry VI of England is crowned King of France.[33]

- 7 November 1455: Isabelle Romée, the mother of Joan of Arc, petitions a papal delegation to overturn her daughter's conviction for heresy.

- 1 January 1537: James V of Scotland is married to Madeleine of France

- 24 April 1558: Mary, Queen of Scots is married to the Dauphin Francis (later Francis II of France), son of Henry II of France.

- 18 August 1572: Henry of Navarre (later Henry IV of France) marries Margaret of Valois. The marriage takes place not in the cathedral but on the parvis of the cathedral, as Henry IV is Protestant.[34]

- 10 September 1573: The Cathedral was the site of a vow made by Henry of Valois following the interregnum of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that he would both respect traditional liberties and the recently passed religious freedom law.[35]

- 10 November 1793: the Festival of Reason.

- 2 December 1804: the coronation ceremony of Napoleon I and his wife Joséphine, with Pope Pius VII officiating.

- 1831: The novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame was published by French author Victor Hugo.

- 1900: Louis Vierne is appointed organist of Notre-Dame de Paris after a heavy competition (with judges including Charles-Marie Widor) against the 500 most talented organ players of the era. On 2 June 1937 Louis Vierne dies at the cathedral organ (as was his lifelong wish) near the end of his 1750th concert.

- 11 February 1931: Antonieta Rivas Mercado shot herself at the altar with a pistol that was the property of her lover Jose Vasconcelos. She died instantly.

- 26 August 1944: The Te Deum#Service Mass takes place in the cathedral to celebrate the liberation of Paris. (According to some accounts the Mass was interrupted by sniper fire from both the internal and external galleries.)

- 12 November 1970: The Requiem Mass of General Charles de Gaulle is held.

- 26 June 1971: Philippe Petit surreptitiously strings a wire between the two towers of Notre-Dame and tight-rope walks across it. Petit later performed a similar act between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

- 31 May 1980: After the Magnificat of this day, Pope John Paul II celebrates Mass on the parvis of the cathedral.

- January 1996: The Requiem Mass of François Mitterrand is held.

- 10 August 2007: The Requiem Mass of Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, former Archbishop of Paris and famous Jewish convert to Catholicism, is held.

- 12 December 2012:The Notre-Dame Cathedral begins a year long celebration of the 850th anniversary of the laying of the first building block for the cathedral.[36]

- 21 May 2013: Around 1,500 visitors were evacuated from Notre-Dame Cathedral after Dominique Venner, a historian, placed a letter on the Church altar and shot himself. He died immediately.[37][38]

- 8 September 2016: Notre Dame Cathedral bombing attempt. Arrests made after an explosives-filled car was discovered parked alongside the cathedral.

- 10 February 2017: Police arrested four people in Montpellier, France, including a 16-year-old girl and a 20-year-old man already known by authorities to have ties to extremist Islamist organizations, on charges of plotting to travel to Paris and attack the cathedral.[39]

- 15 April 2019: A fire breaks out at the cathedral. The outcome is currently uncertain.

The cathedral is renowned for its Lent sermons founded by the famous Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire in the 1860s. In recent years, however, an increasing number have been given by leading public figures and state employed academics.

Gallery

-

A wide angle view of Notre-Dame's western façade

-

Notre-Dame's facade showing the Portal of the Virgin, Portal of the Last Judgment, and Portal of St-Anne

-

A view of Notre-Dame from Montparnasse Tower

-

A wide angle view of Notre-Dame's western facade

-

The Statue of Virgin and Child inside Notre-Dame de Paris

-

Notre-Dame's high altar with the kneeling statues of Louis XIII and Louis XIV

-

South rose window of Notre-Dame de Paris

-

Notre-Dame at the end of the 19th century

-

Flying buttresses of Notre-Dame

-

Tympanum of the Last Judgment

-

Statue of Joan of Arc in Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral interior

-

Close look of the details on the Tympanum of the Last Judgment (2016)

-

Facade of Notre-Dame de Paris.

See also

- French Gothic architecture

- Architecture of Paris

- List of destroyed heritage

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the Paris region

- Musée de Notre-Dame de Paris

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

- May (painting)

- Virgin of Paris

References

- ^ a b c Breeden, Aurelien (15 April 2019). "Part of Notre-Dame Spire Collapses as Paris Cathedral Catches Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Musique Sacrée à Notre-Dame de Paris". msndp.

- ^ Mérimée database 1993

- ^ "Notre Dame". Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ "Notre Dame". Oxford Dictionary of English.

- ^ "Notre Dame". New Oxford American Dictionary.

- ^ The name Notre Dame, meaning "Our Lady" in French, is frequently used in the names of churches including the cathedrals of Chartres, Rheims and Rouen.

- ^ Ducher 1988, pp. 46–62.

- ^ a b c d e "History of the Construction of Notre Dame de Paris" (in French).

- ^ "Paris facts". Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ a b Caroline Bruzelius, The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 69, No. 69 (Dec. 1987), pp. 540–569.

- ^ Williamson, Paul (10 April 1995). Gothic Sculpture, 1140–1300. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-030006-338-7. OCLC 469571482.

- ^ a b c Jason Chavis. "Facts on the Notre Dame Cathedral in France". USA Today. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Visiting the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris: Attractions, Tips & Tours". planetware. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ James A. Herrick, The Making of the New Spirituality, InterVarsity Press, 2004 ISBN 0-8308-3279-3, p. 75-76

- ^ Laurent, Xavier (2003). Grandeur et misère du patrimoine, d'André Malraux à Jacques Duhamel (1959–1973). ISBN 9782900791608. OCLC 53974742.

- ^ a b Seiger, Theresa. "Fire reported at Paris' Notre Dame cathedral". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ a b CNBC (15 April 2019). "Paris' Notre Dame Cathedral on fire". CNBC.

- ^ Hinnant, Lori (15 April 2019). "Catastrophic fire engulfs Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris". AP NEWS. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Marcel Aubert, Notre-Dame de Paris : sa place dans l'histoire de l'architecture du xiie au xive siècle, H. Laurens, 1920, p. 133. (in French)

- ^ País, El (15 April 2019). "La catedral de Notre Dame de París sufre un importante incendio". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew (15 April 2019). "Notre Dame's historic statues safe after being removed just days before massive fire". The Independent. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ a b Viollet-le-Duc, Eugéne, Dictionnaire Raisonné de l'architecture Française du XIe au XVI siecle, Volume 6. (Project Gutenburg).

- ^ Renault and Lazé (2006), page 35

- ^ Frazer, James George (1933) ed., Ovid, Fasti VI. 131–, Riley (1851), p. 216, tr.

- ^ a b Wenzler (2018), pages 97–99

- ^ "West rose window of Notre Dame de Paris, Notre Dame Cathedral West Rose Window, Detail, Digital and Special Collections, Georgetown University Library".

- ^ a b c d "The South Rose- official site of Notre Dame de Paris -" (in French).

- ^ Crypte archéologique du parvis Notre-Dame website Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Erik Inglis, "Gothic Architecture and a Scholastic: Jean de Jandun's Tractatus de laudibus Parisius (1323)," Gesta, XLII/1 (2003), 63–85.

- ^ Sonnerie des nouvelles cloches de Notre-Dame de Paris Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine (notredameparis.fr)

- ^ Communique of the Press and Communication Service of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Paris, November 2014.

- ^ Jean-Baptiste Lebigue, "L'ordo du sacre d'Henri VI à Notre-Dame de Paris (16 décembre 1431)", Notre-Dame de Paris 1163–2013, ed. Cédric Giraud, Turnhout : Brepols, 2013, p. 319-363. Archived 4 April 2014 at archive.today

- ^ Hiatt, Charles, Notre Dame de Paris: a short history & description of the cathedral, (George Bell & Sons, 1902), 12.

- ^ Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish–Lithuanian State, 1386–1795. University of Washington Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-295-98093-1. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Paris's Notre Dame cathedral celebrates 850 years". GIE ATOUT FRANCE. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Notre-Dame Cathedral evacuated after man commits suicide". Fox News Channel. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Frémont, Anne-Laure. "Un historien d'extrême droite se suicide à Notre-Dame". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ McAuley, James (10 February 2016). "After Louvre attack, France foils another terrorist plot". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

Bibliography

- Bruzelius, Caroline. "The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris." Art Bulletin (1987): 540–569 in JSTOR.

- Davis, Michael T. "Splendor and Peril: The Cathedral of Paris, 1290–1350." The Art Bulletin (1998) 80#1 pp: 34–66.

- Ducher, Robert, Caractéristique des Styles, (1988), Flammarion, Paris (in French); ISBN 2-08-011539-1

- Jacobs, Jay, ed. The Horizon Book of Great Cathedrals. New York City: American Heritage Publishing, 1968

- Janson, H.W. History of Art. 3rd Edition. New York City: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1986

- Myers, Bernard S. Art and Civilization. New York City: McGraw-Hill, 1957

- Michelin Travel Publications. The Green Guide Paris. Hertfordshire, UK: Michelin Travel Publications, 2003

- Renault, Christophe and Lazé, Christophe, Les Styles de l'architectue et du mobilier, (2006), Gisserot, (in French); ISBN 9-782877-474658

- Temko, Allan. Notre-Dame of Paris (Viking Press, 1955)

- Tonazzi, Pascal. Florilège de Notre-Dame de Paris (anthologie), Editions Arléa, Paris, 2007, ISBN 2-86959-795-9

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédales Cothiques – un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Wright, Craig. Music and ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550 (Cambridge University Press, 2008)

External links

- "Monument historique – PA00086250". Mérimée database of Monuments Historiques (in French). France: Ministère de la Culture. 1993. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Official website of Notre-Dame de Paris Template:Fr icon Template:En icon

- List of Facts about the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris

- Notre-Dame de Paris's Singers

- Official site of Music at Notre-Dame de Paris

- Panoramic view

- Further information on the Organ with specifications of the Grandes Orgues and the Orgue de Choeur

- Photos: Notre-Dame de Paris – The Gothic Cathedral, Flickr

- Current events from April 2019

- Notre Dame de Paris

- Île de la Cité

- 12th-century Roman Catholic church buildings

- Religious buildings completed in 1345

- 14th-century Roman Catholic church buildings

- Basilica churches in Paris

- Roman Catholic cathedrals in France

- Gothic architecture in France

- Gothic architecture in Paris

- Landmarks in France

- Roman Catholic churches in the 4th arrondissement of Paris

- Victor Hugo

- Pope Alexander III

- Burial sites of the Pippinids

- Joan of Arc

- Destroyed landmarks