Alcoholism: Difference between revisions

→Medications: Adding reference for uncited content. |

→Medications: Deleting non-notable content. |

||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

*''[[Temposil]]'' ([[calcium carbimide]]) works in the same way as Antabuse; it has an advantage in that the occasional adverse effects of disulfiram, hepatotoxicity and drowsiness, do not occur with calcium carbimide.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Ogborne | first1 = AC. | title = Identifying and treating patients with alcohol-related problems. | journal = CMAJ | volume = 162 | issue = 12 | pages = 1705-8 | month = Jun | year = 2000 | PMID = 10870503 }}</ref><ref name="Krampe-2006"/> |

*''[[Temposil]]'' ([[calcium carbimide]]) works in the same way as Antabuse; it has an advantage in that the occasional adverse effects of disulfiram, hepatotoxicity and drowsiness, do not occur with calcium carbimide.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Ogborne | first1 = AC. | title = Identifying and treating patients with alcohol-related problems. | journal = CMAJ | volume = 162 | issue = 12 | pages = 1705-8 | month = Jun | year = 2000 | PMID = 10870503 }}</ref><ref name="Krampe-2006"/> |

||

* ''[[Naltrexone]]'' is a [[competitive antagonist]] for opioid receptors, effectively blocking our ability to use endorphins and opiates. Alcohol causes the body to release endorphins, which in turn release dopamine and activate the reward pathways; hence when naltrexone is in the body there is a reduction in the pleasurable effects from consuming alcohol |

* ''[[Naltrexone]]'' is a [[competitive antagonist]] for opioid receptors, effectively blocking our ability to use endorphins and opiates. Naltrexone is used to decrease cravings for alcohol and encourage abstinence. Alcohol causes the body to release endorphins, which in turn release dopamine and activate the reward pathways; hence when naltrexone is in the body there is a reduction in the pleasurable effects from consuming alcohol.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Soyka | first1 = M. | last2 = Rösner | first2 = S. | title = Opioid antagonists for pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence - a critical review. | journal = Curr Drug Abuse Rev | volume = 1 | issue = 3 | pages = 280-91 | month = Nov | year = 2008 | doi = | PMID = 19630726 }}</ref> |

||

* ''[[Acamprosate]]'' (also known as [[Campral]]) is thought to stabilize the chemical balance of the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcoholism. The [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) approved this drug in 2004, saying "While its mechanism of action is not fully understood, Campral is thought to act on the brain pathways related to alcohol abuse... Campral proved superior to placebo in maintaining abstinence for a short period of time..."<ref>{{cite web| title=FDA Approves New Drug for Treatment of Alcoholism | accessdate=2006-04-02 | url=http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/answers/2004/ANS01302.html}}"</ref> The COMBINE study was unable to demonstrate efficacy for Acamprosate.<ref>{{cite web | title=Naltrexone or Specialized Alcohol Counseling an Effective Treatment for Alcohol Dependence When Delivered with Medical Management | date=2006-05-02 | url=http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/NewsEvents/NewsReleases/COMBINERelease.htm}}</ref> |

* ''[[Acamprosate]]'' (also known as [[Campral]]) is thought to stabilize the chemical balance of the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcoholism. The [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) approved this drug in 2004, saying "While its mechanism of action is not fully understood, Campral is thought to act on the brain pathways related to alcohol abuse... Campral proved superior to placebo in maintaining abstinence for a short period of time..."<ref>{{cite web| title=FDA Approves New Drug for Treatment of Alcoholism | accessdate=2006-04-02 | url=http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/answers/2004/ANS01302.html}}"</ref> The COMBINE study was unable to demonstrate efficacy for Acamprosate.<ref>{{cite web | title=Naltrexone or Specialized Alcohol Counseling an Effective Treatment for Alcohol Dependence When Delivered with Medical Management | date=2006-05-02 | url=http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/NewsEvents/NewsReleases/COMBINERelease.htm}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:55, 20 March 2010

| Alcoholism | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, medical toxicology, psychology, vocational rehabilitation, narcology |

Alcoholism has multiple and conflicting definitions. In common and historic usage, alcoholism is any condition that results in the continued consumption of alcoholic beverages, despite health problems and negative social consequences. Modern medical definitions[1] describe alcoholism as a disease and addiction which results in a persistent use of alcohol despite negative consequences. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, alcoholism, also referred to as dipsomania[2] described a preoccupation with, or compulsion toward the consumption of, alcohol and/or an impaired ability to recognize the negative effects of excessive alcohol consumption.

Although not all of these definitions specify current and on-going use of alcohol as a qualifier for alcoholism, some do, as well as remarking on the long-term effects of consistent, heavy alcohol use, including dependence and symptoms of withdrawal.

While the ingestion of alcohol is, by definition, necessary to develop alcoholism, the use of alcohol does not predict the development of alcoholism. The quantity, frequency and regularity of alcohol consumption required to develop alcoholism varies greatly from person to person. In addition, although the biological mechanisms underpinning alcoholism are uncertain, some risk factors, including social environment, stress,[3] mental health, genetic predisposition, age, ethnicity and gender have been identified.[4] Also, studies indicate that the proportion of men with alcohol dependence is higher than the proportion of women, 7% and 2.5% respectively, although women are more vulnerable to long-term consequences of alcoholism. Around 90% of adults in United States consume alcohol, and more than 700,000 of them are treated daily for alcoholism.[5] Professor David Zaridze, who led the international research team, calculated that alcohol had killed three million Russians since 1987.[6]

Classification

The definitions of alcoholism and related terminology vary significantly between the medical community, treatment programs, and the general public.

Medical definitions

The National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and The American Society of Addiction Medicine define alcoholism as "a primary, chronic disease characterized by impaired control over drinking, preoccupation with the drug alcohol, use of alcohol despite adverse consequences, and distortions in thinking."[7] The DSM-IV (the dominant diagnostic manual in psychiatry and psychology) defines alcohol abuse as repeated use despite recurrent adverse consequences.[8] It further defines alcohol dependence as alcohol abuse combined with tolerance, withdrawal, and an uncontrollable drive to drink.[8] (See DSM diagnosis below.) Within psychology and psychiatry, alcoholism is the popular term for alcohol dependence.[8]

Terminology

Many terms are applied to a drinker's relationship with alcohol. Use, misuse, heavy use, abuse, addiction, and dependence are all common labels used to describe drinking habits, but the actual meaning of these words can vary greatly depending upon the context in which they are used. Even within the medical field, the definition can vary between areas of specialization. Because alcoholism is often used in a derogatory sense in politics and religion, the meanings of the words surrounding it are often used imprecisely.

Use refers to simple use of a substance. An individual who drinks any beverage with alcohol is using alcohol. Misuse, problem use, abuse, and heavy use refers to improper use of alcohol which may cause physical, social, or moral harm to the drinker.[9]

Moderate Use is defined by The Dietary Guidelines for Americans as no more than two alcoholic beverages per day for men and no more than one alcoholic beverage per day for women.[10]

Risk factors

About 40 percent of those who begin drinking alcohol before age 14 develop alcohol dependence, whereas only 10 percent of those who did not begin drinking until 20 years or older developed an alcohol problem in later life,[11] although it should be borne in mind that Correlation does not imply causation. Alcohol abuse during adolescence may lead to long-term changes in the brain which leaves them at increased risk of alcoholism in later years; genetic factors also influence age of onset of alcohol abuse and risk of alcoholism.[12]

The age of onset of drinking as well as genetic factors are associated with an increased risk of the development of alcoholism. Individuals who have a pre-existing vulnerability to alcoholism are also more likely to begin drinking earlier than average.[12] The risk taking behavior associated with adolescence promotes binge drinking. Age and genetic factors influence the risk of developing alcohol related neurotoxicity.[13] Genetic traits which influence the risk of the development of alcoholism are associated with a family history of alcoholism.[14] One published article has found that alcohol use at an early age may itself directly influence the risk of developing alcoholism via influencing the expression of genes which increase the risk of alcohol dependence.[15] It has been hypothesized that this increased risk may be due to the highly sensitive developing adolescent brain which leads to modulating of the genetic state of the brain which in turn primes the adolescent for increased risk of alcohol dependence. About 40 percent of alcoholics were drinking excessively by late adolescence. Most alcoholics develop alcoholism during adolescence or young adulthood. Severe childhood trauma is also associated with an increased risk of alcohol or other drug problems. There is evidence that a complex mixture of genetic factors as well as environmental factors, e.g. stressful childhood events, influence the risk of the development of alcoholism. Genes which influence the metabolism of alcohol also influence the risk of alcoholism. Good peer and family support is associated with a reduced risk of alcoholism developing.[16]

Signs and symptoms

Effects of long term alcohol misuse

The primary effect of alcoholism is to encourage the sufferer to drink at times and in amounts that are damaging to physical health. The secondary damage caused by an inability to control one's drinking manifests in many ways. Alcoholism also has significant social costs to both the alcoholic and their family and friends.[17] Alcoholism can have adverse effects on mental health causing psychiatric disorders to develop.[18] Approximately 18 percent of alcoholics commit suicide.[19] Research has found that over fifty percent of all suicides are associated with alcohol or drug dependence. In adolescents the figure is higher with alcohol or drug misuse playing a role in up to 70 percent of suicides.[20]

- Physical health effects

The physical health effects associated with alcohol consumption may include cirrhosis of the liver, pancreatitis, epilepsy, polyneuropathy, alcoholic dementia, heart disease, increased chance of cancer, nutritional deficiencies, sexual dysfunction, and death from many sources. Severe cognitive problems are not uncommon in alcoholics. Approximately 10% of all dementia cases are alcohol related making alcohol the 2nd leading cause of dementia.[21] Other adverse effects on physical health include an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, malabsorption, alcoholic liver disease, and cancer. Damage to the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system can occur from sustained alcohol consumption.[22][23] The most common cause of death in alcoholics is due to cardiovascular complications.[24]

- Mental health effects

Long term misuse of alcohol can cause a wide range of mental health effects. Alcohol misuse is not only toxic to the body but also to brain function and thus psychological well being can be adversely affected by the long-term effects of misuse.[25] Psychiatric disorders are common in alcoholics, especially anxiety and depression disorders, with as many as 25% of alcoholics presenting with severe psychiatric disturbances. Typically these psychiatric symptoms caused by alcohol misuse initially worsen during alcohol withdrawal but with abstinence these psychiatric symptoms typically gradually improve or disappear altogether.[26] Psychosis, confusion and organic brain syndrome may be induced by chronic alcohol abuse which can lead to a misdiagnosis of major mental health disorders such as schizophrenia.[27] Panic disorder can develop as a direct result of long term alcohol misuse. Panic disorder can also worsen or occur as part of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome.[28] Chronic alcohol misuse can cause panic disorder to develop or worsen an underlying panic disorder via distortion of the neurochemical system in the brain.[29]

The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder and alcoholism is well documented.[30][31][32] Among those with comorbid occurrences, a distinction is commonly made between depressive episodes that are secondary to the pharmacological or toxic effects of heavy alcohol use and remit with abstinence, and depressive episodes that are primary and do not remit with abstinence. Additional use of other drugs may increase the risk of depression in alcoholics.[33] Depressive episodes with an onset prior to heavy drinking or those that continue in the absence of heavy drinking are typically referred to as "independent" episodes, whereas those that appear to be etiologically related to heavy drinking are termed "substance-induced".[34][35][36] There is a high rate of suicide in chronic alcoholics with the risk of suicide increasing the longer a person drinks. The reasons believed to cause the increased risk of suicide in alcoholics include the long-term abuse of alcohol causing physiological distortion of brain chemistry as well as the social isolation which is common in alcoholics. Suicide is also very common in adolescent alcohol abusers, with 1 in 4 suicides in adolescents being related to alcohol abuse.[37]

- Social effects

The social problems arising from alcoholism can be massive and are caused in part due to the serious pathological changes induced in the brain from prolonged alcohol misuse and partly because of the intoxicating effects of alcohol.[17][21] Alcohol abuse is also associated with increased risks of committing criminal offences including child abuse, domestic violence, rapes, burglaries and assaults.[38] Alcoholism is associated with loss of employment,[39] which can lead to financial problems including the loss of living quarters. Drinking at inappropriate times, and behavior caused by reduced judgment, can lead to legal consequences, such as criminal charges for drunk driving[40] or public disorder, or civil penalties for tortious behavior. An alcoholic's behavior and mental impairment while drunk can profoundly impact those surrounding them and lead to isolation from family and friends, possibly leading to marital conflict and divorce, or contributing to domestic violence. This can contribute to a loss of self-esteem and even lead to jail. Alcoholism can also lead to child neglect, with subsequent lasting damage to the emotional development of the alcoholic's children, even after they reach adulthood.[41]

Alcohol withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal differs significantly from most other drugs in that it can be directly fatal. For example it is extremely rare for heroin withdrawal to be fatal. When people die from heroin or cocaine withdrawal they typically have serious underlying health problems which are made worse by the strain of acute withdrawal. An alcoholic, however, who has no serious health issues, has a significant risk of dying from the direct effects of withdrawal if it is not properly managed.[17] Sedative-hypnotic drugs such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines which have a similar mechanism of action to alcohol (which is also a sedative-hypnotic) also have a similar risk of causing death during withdrawal.[42]

Alcohol's primary effect is the increase in stimulation of the GABAA receptor, promoting central nervous system depression. With repeated heavy consumption of alcohol, these receptors are desensitized and reduced in number, resulting in tolerance and physical dependence. Thus when alcohol is stopped, especially abruptly, the person's nervous system suffers from uncontrolled synapse firing. This can result in symptoms that include anxiety, life threatening seizures, delirium tremens and hallucinations, shakes and possible heart failure.[43][44]

Acute withdrawal symptoms tend to subside after one to three weeks. Less severe symptoms (e.g. insomnia and anxiety, anhedonia) may continue as part of a post withdrawal syndrome gradually improving with abstinence for a year or more.[45][46][47] Withdrawal symptoms begin to subside as the body and central nervous system makes adaptations to reverse tolerance and restore GABA function towards normal.[48][49] Other neurotransmitter systems are involved, especially glutamate and NMDA.[50]

Diagnosis

Multiple tools are available to those wishing to conduct screening for alcoholism. Identification involves an objective assessment regarding the damage that imbibing alcohol does to the drinker's life compared with the subjective benefits the drinker perceives from consuming alcohol. While there are many cases where an alcoholic's life has been significantly and obviously damaged, there are always borderline cases that can be difficult to classify.

Addiction Medicine specialists have extensive training with respect to diagnosing and treating patients with alcoholism.

Screening

Several tools may be used to detect a loss of control of alcohol use. These tools are mostly self reports in questionnaire form. Another common theme is a score or tally that sums up the general severity of alcohol use.

- The CAGE questionnaire, named for its four questions, is one such example that may be used to screen patients quickly in a doctor's office.

Two "yes" responses indicate that the respondent should be investigated further.

The questionnaire asks the following questions:

- The CAGE questionnaire has demonstrated a high effectiveness in detecting alcohol related problems; however, it has limitations in people with less severe alcohol related problems, white women and college students.[53]

- The Alcohol Dependence Data Questionnaire is a more sensitive diagnostic test than the CAGE test.[54] It helps distinguish a diagnosis of alcohol dependence from one of heavy alcohol use.

- The Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) is a screening tool for alcoholism widely used by courts to determine the appropriate sentencing for people convicted of alcohol-related offenses,[55] driving under the influence being the most common.

- The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a screening questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization. This test is unique in that it has been validated in six countries and is used internationally.[56] Like the CAGE questionnaire, it uses a simple set of questions - a high score earning a deeper investigation.

- The Paddington Alcohol Test (PAT) was designed to screen for alcohol related problems amongst those attending Accident and Emergency departments. It concords well with the AUDIT questionnaire but is administered in a fifth of the time.[57]

Genetic predisposition testing

Psychiatric geneticists John I. Nurnberger, Jr., and Laura Jean Bierut suggest that alcoholism does not have a single cause—including genetic—but that genes do play an important role "by affecting processes in the body and brain that interact with one another and with an individual's life experiences to produce protection or susceptibility." They also report that fewer than a dozen alcoholism-related genes have been identified, but that more likely await discovery.[58]

At least one genetic test exists for an allele that is correlated to alcoholism and opiate addiction.[59] Human dopamine receptor genes have a detectable variation referred to as the DRD2 TaqI polymorphism. Those who possess the A1 allele (variation) of this polymorphism have a small but significant tendency towards addiction to opiates and endorphin releasing drugs like alcohol.[60] Although this allele is slightly more common in alcoholics and opiate addicts, it is not by itself an adequate predictor of alcoholism, and some researchers argue that evidence for DRD2 is contradictory.[58]

DSM diagnosis

The DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence represents one approach to the definition of alcoholism. In part this is to assist in the development of research protocols in which findings can be compared with one another. According to the DSM-IV, an alcohol dependence diagnosis is:[61]

...maladaptive alcohol use with clinically significant impairment as manifested by at least three of the following within any one-year period: tolerance; withdrawal; taken in greater amounts or over longer time course than intended; desire or unsuccessful attempts to cut down or control use; great deal of time spent obtaining, using, or recovering from use; social, occupational, or recreational activities given up or reduced; continued use despite knowledge of physical or psychological sequelae.

Urine and blood tests

There are reliable tests for the actual use of alcohol, one common test being that of blood alcohol content (BAC).[62] These tests do not differentiate alcoholics from non-alcoholics; however, long-term heavy drinking does have a few recognizable effects on the body, including:[63]

- Macrocytosis (enlarged MCV)1

- Elevated GGT²

- Moderate elevation of AST and ALT and an AST: ALT ratio of 2:1.

- High carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT)

However, none of these blood tests for biological markers are as sensitive as screening questionaires.

Prevention

Because alcohol use disorders are perceived as impacting society as a whole, World Health Organization, the European Union and other regional bodies, national governments and parliaments have formed alcohol policies in order to reduce the harm of alcoholism.[64][65]

To combat the health, social and educational underachievement which results from alcohol or drug dependence targeting adolescents and young adults is regarded as an important step to reduce the harm of alcohol abuse. The age at which licit drugs of abuse such as alcohol can be purchased as well as banning or restricting advertising of alcohol has been recommended. Credible and evidence based educational drives in the mass media about the consequences of alcohol and other drug abuse has also been recommended. Guidelines for parents on alcohol and drug use during adolescence and targeting young people with mental health problems has also been suggested to prevent the harm of alcohol and other drug abuse.[66]

Management

Treatments for alcoholism (antidipsotropic) are quite varied because there are multiple perspectives for the condition itself. Those who approach alcoholism as a medical condition or disease recommend differing treatments than, for instance, those who approach the condition as one of social choice.

Most treatments focus on helping people discontinue their alcohol intake, followed up with life training and/or social support in order to help them resist a return to alcohol use. Since alcoholism involves multiple factors which encourage a person to continue drinking, they must all be addressed in order to successfully prevent a relapse. An example of this kind of treatment is detoxification followed by a combination of supportive therapy, attendance at self-help groups, and ongoing development of coping mechanisms. The treatment community for alcoholism typically supports an abstinence-based zero tolerance approach; however, there are some who promote a harm-reduction approach as well.[67]

Detoxification

Alcohol detoxification or 'detox' for alcoholics is an abrupt stop of alcohol drinking coupled with the substitution of drugs, such as benzodiazepines, that have similar effects to prevent alcohol withdrawal. Individuals who are only at risk of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms can be detoxified as outpatients. Individuals at risk of a severe withdrawal syndrome as well as those who have significant or acute comorbid conditions are generally treated as inpatients. Detoxification does not, however, actually treat alcoholism. Therefore it is necessary to follow-up a detoxification with appropriate treatment program for alcohol dependence in order to reduce the risk of relapse.[68]

Group therapy and psychotherapy

After detoxification, various forms of group therapy or psychotherapy can be used to deal with underlying psychological issues that are related to alcohol addiction, as well as provide relapse prevention skills. The mutual-help group-counseling approach is one of the most common ways of helping alcoholics maintain sobriety.[69][70] Many organizations have been formed to provide this service. Alcoholics Anonymous was the first group, and has more members than all other programs combined. Some of the others include LifeRing Secular Recovery, Rational Recovery, SMART Recovery, and Women For Sobriety.

Rationing and moderation

Rationing and moderation programs such as Moderation Management and DrinkWise do not mandate complete abstinence. While most alcoholics are unable to limit their drinking in this way, some return to moderate drinking. A 2002 U.S. study by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) showed that 17.7% of individuals diagnosed as alcohol dependent more than one year prior returned to low-risk drinking. This group, however, showed fewer initial symptoms of dependency.[71] A follow-up study, using the same subjects that were judged to be in remission in 2001-2002, examined the rates of return to problem drinking in 2004-2005. The study found abstinence from alcohol was the most stable form of remission for recovering alcoholics.[72] A long-term (60 year) follow-up of two groups of alcoholic men concluded that "return to controlled drinking rarely persisted for much more than a decade without relapse or evolution into abstinence."[73]

Medications

A variety of medications may be prescribed as part of treatment for alcoholism.

Medications currently in use

- Antabuse (disulfiram) prevents the elimination of acetaldehyde, a chemical the body produces when breaking down ethanol. Acetaldehyde itself is the cause of many hangover symptoms from alcohol use. The overall effect is severe discomfort when alcohol is ingested: an extremely fast-acting and long-lasting uncomfortable hangover. This discourages an alcoholic from drinking in significant amounts while they take the medicine. A recent 9-year study found that incorporation of supervised disulfiram and a related compound carbamide into a comprehensive treatment program resulted in an abstinence rate of over 50%.[74]

- Temposil (calcium carbimide) works in the same way as Antabuse; it has an advantage in that the occasional adverse effects of disulfiram, hepatotoxicity and drowsiness, do not occur with calcium carbimide.[75][74]

- Naltrexone is a competitive antagonist for opioid receptors, effectively blocking our ability to use endorphins and opiates. Naltrexone is used to decrease cravings for alcohol and encourage abstinence. Alcohol causes the body to release endorphins, which in turn release dopamine and activate the reward pathways; hence when naltrexone is in the body there is a reduction in the pleasurable effects from consuming alcohol.[76]

- Acamprosate (also known as Campral) is thought to stabilize the chemical balance of the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcoholism. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved this drug in 2004, saying "While its mechanism of action is not fully understood, Campral is thought to act on the brain pathways related to alcohol abuse... Campral proved superior to placebo in maintaining abstinence for a short period of time..."[77] The COMBINE study was unable to demonstrate efficacy for Acamprosate.[78]

Experimental Medications

Many experimental medications are presently in clinical trials for the treatment of alcoholism. Promising results have been obtained with anticonvulsant drugs usually used to treat epilepsy.[79]

- Topiramate (brand name Topamax), a derivative of the naturally occurring sugar monosaccharide D-fructose, has been found effective in helping alcoholics quit or cut back on the amount they drink. In one study heavy drinkers were six times more likely to remain abstinent for a month if they took the medication, even in small doses.[80][81] In another study, those who received topiramate had fewer heavy drinking days, fewer drinks per day and more days of continuous abstinence than those who received the placebo.[82] Evidence suggests that topiramate antagonizes excitatory glutamate receptors, inhibits dopamine release, and enhances inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid function. A 2008 review of the effectiness of topiramate concluded that the results of published trials are promising, however at this time, data are insufficient to support using topiramate in conjunction with brief weekly compliance counseling as a first-line agent for alcohol dependence.[83]

Medications which may worsen outcome

- Benzodiazepines, whilst useful in the management of acute alcohol withdrawal, if used long-term cause a worse outcome in alcoholism. Alcoholics on chronic benzodiazepines have a lower rate of achieving abstinence from alcohol than those not taking benzodiazepines. This class of drugs are commonly prescribed to alcoholics for insomnia or anxiety management.[84] Initiating prescriptions of Benzodiazepines or sedative-hypnotics in individuals in recovery has a high rate of relapse with one author reporting more than a quarter of people relapse after being prescribed sedative-hypnotics. Patients often mistakenly think that they are sober despite continuing to take benzodiazepines. Those who are long-term users of benzodiazepines should not be withdrawn rapidly, taper regimes of 6–12 months have been found to be the most successful, with reduced intensity of withdrawal.[85]

Dual addictions

The AMA definition of alcoholism refers to a disease entity involving the compulsive use of alcohol despite social, physical and mental harm.[citation needed]. The DSM-IV definition of alcohol dependence refers to alcohol only, and DSM-IV uses sedative dependence to refer to the disease entity involving non-alcohol sedative agents.[citation needed]

Alcoholics may also require treatment for other psychotropic drug addictions. The most common dual addiction in alcohol dependence is a benzodiazepine dependence with studies showing 10 - 20% of alcohol dependent individuals having problems of dependence and/or misuse problems of benzodiazepines. Alcohol itself is a sedative-hypnotic and is cross-tolerant with other sedative-hypnotics such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines and the nonbenzodiazepines. Dependence on other sedative hypnotics such as zolpidem and zopiclone as well as opiates and illegal drugs is common in alcoholics. Dependence and withdrawal from sedative hypnotics, e.g. benzodiazepine withdrawal is similar to alcohol and can be medically severe and include the risk of psychosis and seizures if not managed properly.[86] Benzodiazepine dependency requires careful reduction in dosage to avoid a serious benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome and health consequences. Benzodiazepines have the problem of increasing cravings for alcohol in problem alcohol consumers. Benzodiazepines also increase the volume of alcohol consumed by problem drinkers.[87]

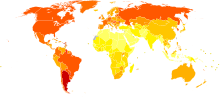

Epidemiology

Substance use disorders are a major public health problem facing many countries. "The most common substance of abuse/dependence in patients presenting for treatment is alcohol."[67] In the United Kingdom, the number of 'dependent drinkers' was calculated as over 2.8 million in 2001.[89] The World Health Organization estimates that about 140 million people throughout the world suffer from alcohol dependence.[90][91] In the United States and western Europe 10 to 20% of men and 5 to 10% of women at some point in their lives will meet criteria for alcoholism.[92]

Within the medical and scientific communities, there is broad consensus regarding alcoholism as a disease state. For example, the American Medical Association considers alcohol a drug and states that "drug addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite often devastating consequences. It results from a complex interplay of biological vulnerability, environmental exposure, and developmental factors (e.g., stage of brain maturity)."[93]

Current evidence indicates that in both men and women, alcoholism is 50-60% genetically determined, leaving 40-50% for environmental influences.[94]

A 2002 study by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism surveyed a group of 4,422 adults meeting the criteria for alcohol dependence and found that after one year, some met the authors' criteria for low-risk drinking, even though only 25.5% of the group received any treatment,[95] with the breakdown as follows:

- 25% still dependent

- 27.3% in partial remission (some symptoms persist)

- 11.8% asymptomatic drinkers (consumption increases chances of relapse)

- 35.9% fully recovered — made up of 17.7% low-risk drinkers plus 18.2% abstainers.

In contrast, however, the results of a long term (60 year) follow-up of two groups of alcoholic men by George Vaillant at Harvard Medical School indicated that "return to controlled drinking rarely persisted for much more than a decade without relapse or evolution into abstinence."[96] Vaillant also noted that "return-to-controlled drinking, as reported in short-term studies, is often a mirage."

History

Etymology

The term "alcoholism" was first used in 1849 by the Swedish physician Magnus Huss to describe the systematic adverse effects of alcohol.[97]

In the United States, use of the word "alcoholism" was largely popularized by the founding and growth of Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935[citation needed]. AA's basic text, known as the "Big Book," describes alcoholism as an illness that involves a physical allergy[98]: p.xxviii and a mental obsession.[98]: p.23 [99] Note that the definition of "allergy" used in this context is not the same as used in modern medicine.[100] . The doctor and addiction specialist Dr. William D. Silkworth M.D. writes on behalf of AA that Alcoholics suffer from a "(physical) craving beyond mental control".[101]

A 1960 study by E. Morton Jellinek is considered the foundation of the modern disease theory of alcoholism.[102] Jellinek's definition restricted the use of the word "alcoholism" to those showing a particular natural history. The modern medical definition of alcoholism has been revised numerous times since then. The American Medical Association currently uses the word alcoholism to refer to a particular chronic primary disease.[93]

A minority opinion within the field, notably advocated by Herbert Fingarette and Stanton Peele, argue against the existence of alcoholism as a disease. Critics of the disease model tend to use the term "heavy drinking" when discussing the negative effects of alcohol consumption.

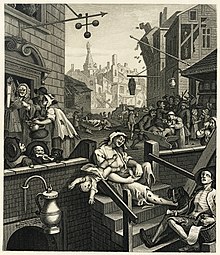

Society and culture

The various health problems associated with long-term alcohol consumption are generally perceived as detrimental to society, for example, money due to lost labor-hours, medical costs, and secondary treatment costs. Alcohol use is a major contributing factor for head injuries, motor vehicle accidents, violence, and assaults. Beyond money, there is also the pain and suffering of the individuals besides the alcoholic affected. For instance, alcohol consumption by a pregnant woman can lead to Fetal alcohol syndrome,[103] an incurable and damaging condition.[104]

Estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse, collected by the World Health Organization, vary from one to six per cent of a country's GDP.[105] One Australian estimate pegged alcohol's social costs at 24 per cent of all drug abuse costs; a similar Canadian study concluded alcohol's share was 41 per cent.[106]

A study quantified the cost to the UK of all forms of alcohol misuse as £18.5–20 billion annually (2001 figures).[89][107]

Stereotypes

Stereotypes of alcoholics are often found in fiction and popular culture. The 'town drunk' is a stock character in Western popular culture.

Stereotypes of drunkenness may be based on racism or xenophobia, as in the depiction of the Irish as heavy drinkers.[108][109]

Studies by social psychologists Stivers and Greeley[110] attempt to document the perceived prevalence of high alcohol consumption amongst the Irish in America.

Of the adult US population, at least 75% are drinkers; and about 6% of the total group are alcoholics. In groups which are almost 100% drinkers, the alcoholism rate is about 8%. Many reports state that about 73% of felonies are alcohol-related. One survey shows that in about 67% of child-beating cases, 41% of forcible rape cases, 80% of wife-battering, 72% of stabbings, and 83% of homicides, either the attacker or the victim or both had been drinking."[111]

In film and literature

In modern times, the recovery movement has led to more realistic depictions of problems that stem from heavy alcohol use. Authors such as Charles R. Jackson and Charles Bukowski describe their own alcohol addiction in their writings. The disjointed narrative of Patrick Hamilton's Hangover Square reflects the alcoholism of its central character. A famous depiction of alcoholism, and the psychology of an alcoholic, is in Malcolm Lowry's widely acclaimed novel Under the Volcano, which details the final day of the British consul Geoffrey Firmin on the Day of the Dead in 1939 Mexico and his choice to continue his extreme alcohol consumption instead of returning to the wife he loves.

Films like Bad Santa, Barfly, Days of Wine and Roses, Ironweed, My Name Is Bill W., Withnail and I, Arthur, Leaving Las Vegas, When a Man Loves a Woman, Shattered Spirits and The Lost Weekend chronicle similar stories of alcoholism.

Women and alcoholism

Alcoholism has a higher prevalence among men, though in recent decades, the proportion of female alcoholics has increased.[112] It is important to articulate the different biological and social ways alcoholism manifests in women in order to understand barriers to treatment and effective recovery strategies.

Biological differences and physiological effects

Biologically, women have symptom profiles from their alcohol use that differ in important ways from men. They experience a telescoping of physiological effects from alcohol use. Equal dosages of alcohol consumed by men and women generally result in women having higher blood alcohol concentrations (BACs).[113] This can be attributed to many reasons, the main being that women have less body water than men. A given amount of alcohol, therefore becomes more highly concentrated in a woman's body. Besides this fact, women also become more intoxicated, which is due to different hormone release.[112]

Women develop long-term complications of alcohol dependence more rapidly than do alcoholic men. Additionally, women have a higher mortality rate from alcoholism than men.[114] Examples of long term complications include brain, heart, and liver damage[112] and an increased risk for breast cancer (see alcohol and breast cancer). Additionally, heavy drinking over time has been found to have a negative effect on reproductive functioning in women. This results in reproductive dysfunction such as anovulation, decreased ovarian mass, irregular menses, amenorrhea, luteal phase dysfunction, and early menopause.[114]

Psychological and emotional effects

Psychiatric disorders are generally more prevalent among those with alcohol disorders. This is true for both men and women, however the disorders differ depending on gender. Women who have alcohol-use disorders often have co-occurring psychiatric diagnosis such as major depression, anxiety, panic disorder, bulimia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or borderline personality disorder. Men with alcohol-use disorders more often have co-occurring diagnosis of narcissistic and antisocial personality disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, impulse disorders and attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder.[113]

Women with alcoholism are also more likely to have a history of physical or sexual assault, abuse and domestic violence than those in the general population.[113] This trauma can lead to higher instances of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and a greater dependence on alcohol.

Societal barriers to treatment

Attitudes and social stereotypes about women and alcohol can create barriers to the detection and treatment of female alcohol abusers. Such beliefs stigmatize women who drink by characterizing them as "both generally and sexually immoral" or the "fallen women." Fear of stigmatization may lead women to deny that they are suffering from a medical condition, to hide their drinking, and to drink alone. This pattern, in turn, leads family, physicians, and others to be less likely to suspect that a woman they know is an alcoholic.[114]

In contrast, attitudes and social stereotypes about men and alcohol can lower barriers to the detection and treatment of male alcohol abusers. Such beliefs reward men who drink by characterizing them as "both generally and sexually moral" or the "risen men." Reduced fear of stigma may lead men to admit that they are suffering from a medical condition, to publicly display their drinking, and to drink in groups. This pattern, in turn, leads family, physicians, and others to be more likely to suspect that a man they know is an alcoholic. Women also tend to have a greater fear that the negative implications from the stigma will reflect poorly on their families. This may also keep them from seeking help.[113]

Implications for treatment

Research has indicated a lack of adequate training for practitioners both in problematic alcohol use in general, and in relation to women's issues.[113] The complexity of alcohol use disorders, particularly with gender-related issues, indicates that the need for practitioners' knowledge, insight and compassion is enormous.[113] Better education and awareness surrounding the gender implications of alcoholism will help care providers to adequately treat women who suffer from alcoholism. Early intervention will also increase the probability of recovery.

See also

- Alcohol consumption and health

- Alcoholism in family systems

- Alcohol dementia

- Alcohol-related traffic crashes

- Alcohol tolerance

- Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

- Alcoholic lung disease

- Binge drinking

- List of countries by alcohol consumption

- Alcohol intoxication

- E. Morton Jellinek

- Ethanol Metabolism biochemical discussion of alcohol metabolism

- Handbook on Drug and Alcohol Abuse

- Hangover

- List of deaths through alcohol

- Substance abuse

- Self-medication

- Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome

- Willingway Hospital

- Medical diagnostics to test for alcohol use

- Al-Anon and Alateen: support groups for friends and families affected by alcoholism

- The Lost Weekend (film) (movie, 1945)

- Leaving Las Vegas (movie, 1995)

References

- ^ The American Medical Association "Definitions"

- ^ www.dictionary.com,Definition: dipsomania

- ^ Glavas MM, Weinberg J (2006). "Stress, Alcohol Consumption, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis". In Yehuda S, Mostofsky DI (ed.). Nutrients, Stress, and Medical Disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 165–183. ISBN 978-1-58829-432-6.

- ^ Agarwal-Kozlowski, K.; Agarwal, DP. (2000). "[Genetic predisposition for alcoholism]". Ther Umsch. 57 (4): 179–84. PMID 10804873.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chen, CY.; Storr, CL.; Anthony, JC. (2009). "Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems". Addict Behav. 34 (3): 319–22. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.021. PMC 2677076. PMID 19022584.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vodka kills as many Russians as a war, says report in The Lancet. Times Online. June 27, 2009.

- ^ Morse RM, Flavin DK (1992). "The definition of alcoholism. The Joint Committee of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and the American Society of Addiction Medicine to Study the Definition and Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alcoholism". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 268 (8): 1012–4. doi:10.1001/jama.268.8.1012. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 1501306.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c VandenBos, Gary R. (15 July 2006). APA dictionary of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-59147-380-0.

- ^ of the American Heritage Dictionaries, Editors (12 April 2006). The American Heritage dictionary of the English language (4 ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-70172-8.

To use wrongly or improperly; misuse: abuse alcohol

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005". USA: health.gov. 2005. Dietary Guidelines]

- ^ Grant, BF.; Dawson, DA. (1997). "Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey". J Subst Abuse. 9: 103–10. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(97)90009-2. PMID 9494942.

- ^ a b "Early Age At First Drink May Modify Tween/Teen Risk For Alcohol Dependence". Medical News Today. 21 September 2009.

- ^ Bowden, SC.; Crews, FT.; Bates, ME.; Fals-Stewart, W.; Ambrose, ML. (2001). "Neurotoxicity and neurocognitive impairments with alcohol and drug-use disorders: potential roles in addiction and recovery". Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 25 (2): 317–21. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02215.x. PMID 11236849.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bierut, LJ.; Schuckit, MA.; Hesselbrock, V.; Reich, T. (2000). "Co-occurring risk factors for alcohol dependence and habitual smoking". Alcohol Res Health. 24 (4): 233–41. PMID 15986718.

- ^ Agrawal, Arpana; Sartor, Carolyn E.; Lynskey, Michael T.; Grant, Julia D.; Pergadia, Michele L.; Grucza, Richard; Bucholz, Kathleen K.; Nelson, Elliot C.; Madden, Pamela A. F. (2009). "Evidence for an Interaction Between Age at First Drink and Genetic Influences on DSM-IV Alcohol Dependence Symptoms". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 33: 2047. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01044.x.

- ^ Enoch, MA. (2006). "Genetic and environmental influences on the development of alcoholism: resilience vs. risk". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1094: 193–201. doi:10.1196/annals.1376.019. PMID 17347351.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c McCully, Chris (2004). Goodbye Mr. Wonderful. Alcohol, Addition and Early Recovery. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84310-265-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); More than one of|author=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ Dunn, N; Cook (1999). "Psychiatric aspects of alcohol misuse". Hospital medicine (London, England : 1998). 60 (3): 169–72. ISSN 1462-3935. PMID 10476237.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author2=and|last2=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wilson, Richard; Kolander, Cheryl A. (2003). Drug abuse prevention: a school and community partnership. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett. pp. 40–45. ISBN 978-0-7637-1461-1.

- ^ Miller, NS; Mahler; Gold (1991). "Suicide risk associated with drug and alcohol dependence". Journal of addictive diseases. 10 (3): 49–61. doi:10.1300/J069v10n03_06. ISSN 1055-0887. PMID 1932152.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author2=and|last2=specified (help); More than one of|author3=and|last3=specified (help) - ^ a b Professor Georgy Bakalkin (8 July 2008). "Alcoholism-associated molecular adaptations in brain neurocognitive circuits". eurekalert.org. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ Müller D, Koch RD, von Specht H, Völker W, Münch EM (1985). "[Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse]". Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) (in German). 37 (3): 129–32. PMID 2988001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Testino G (2008). "Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view". Hepatogastroenterology. 55 (82–83): 371–7. PMID 18613369.

- ^ Zuskin, E.; Jukić, V.; Lipozencić, J.; Matosić, A.; Mustajbegović, J.; Turcić, N.; Poplasen-Orlovac, D.; Bubas, M.; Prohić, A. (2006). "[Alcoholism--how it affects health and working capacity]". Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 57 (4): 413–26. PMID 17265681.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Oscar-Berman, Marlene (2003). "Alcoholism and the brain: an overview". Alcohol Res Health. 27 (2): 125–33. PMID 15303622.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wetterling T; Junghanns, K (2000). "Psychopathology of alcoholics during withdrawal and early abstinence". Eur Psychiatry. 15 (8): 483–8. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00519-8. ISSN 0924-9338. PMID 11175926.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schuckit MA (1983). "Alcoholism and other psychiatric disorders". Hosp Community Psychiatry. 34 (11): 1022–7. ISSN 0022-1597. PMID 6642446.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cowley DS (January 24, 1992). "Alcohol abuse, substance abuse, and panic disorder". Am J Med. 92 (1A): 41S–48S. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90136-Y. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 1346485.

- ^ Cosci F; Schruers, KR; Abrams, K; Griez, EJ (2007). "Alcohol use disorders and panic disorder: a review of the evidence of a direct relationship". J Clin Psychiatry. 68 (6): 874–80. doi:10.4088/JCP.v68n0608. ISSN 0160-6689. PMID 17592911.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Grant BF, Harford TC (1995). "Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey". Drug Alcohol Depend. 39 (3): 197–206. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(95)01160-4. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 8556968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kandel DB, Huang FY, Davies M (2001). "Comorbidity between patterns of substance use dependence and psychiatric syndromes". Drug Alcohol Depend. 64 (2): 233–41. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00126-0. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 11543993.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cornelius JR, Bukstein O, Salloum I, Clark D (2003). "Alcohol and psychiatric comorbidity". Recent Dev Alcohol. 16: 361–74. doi:10.1007/0-306-47939-7_24. ISSN 0738-422X. PMID 12638646.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schuckit M (1983). "Alcoholic patients with secondary depression". Am J Psychiatry. 140 (6): 711–4. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 6846629.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bergman M, Reich W, Hesselbrock VM, Smith TL (1997). "Comparison of induced and independent major depressive disorders in 2,945 alcoholics". Am J Psychiatry. 154 (7): 948–57. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 9210745.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bucholz KK (1997). "The life-time rates of three major mood disorders and four major anxiety disorders in alcoholics and controls". Addiction. 92 (10): 1289–304. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb02848.x. ISSN 0965-2140. PMID 9489046.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP (2007). "A comparison of factors associated with substance-induced versus independent depressions". J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 68 (6): 805–12. ISSN 1937-1888. PMID 17960298.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ O'Connor, Rory; Sheehy, Noel (29 Jan 2000). Understanding suicidal behaviour. Leicester: BPS Books. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-1-85433-290-5.

- ^ Isralowitz, Richard (2004). Drug use: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-57607-708-5.

- ^ Langdana, Farrokh K. (27 March 2009). Macroeconomic Policy: Demystifying Monetary and Fiscal Policy (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-387-77665-1.

- ^ Gifford, Maria (22 October 2009). Alcoholism (Biographies of Disease). Greenwood Press. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-0-313-35908-8.

- ^ Schadé, Johannes Petrus (October 2006). The Complete Encyclopedia of Medicine and Health. Foreign Media Books. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-60136-001-4.

- ^ Galanter, Marc; Kleber, Herbert D. (1 July 2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States of America: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 58. ISBN 978-1585622764.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Dart, Richard C. (1 December 2003). Medical Toxicology (3rd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0781728454.

- ^ Idemudia SO, Bhadra S, Lal H (1989). "The pentylenetetrazol-like interoceptive stimulus produced by ethanol withdrawal is potentiated by bicuculline and picrotoxinin". Neuropsychopharmacology. 2 (2): 115–22. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(89)90014-6. ISSN 0893-133X. PMID 2742726.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martinotti G; Nicola, MD; Reina, D; Andreoli, S; Focà, F; Cunniff, A; Tonioni, F; Bria, P; Janiri, L (2008). "Alcohol protracted withdrawal syndrome: the role of anhedonia". Subst Use Misuse. 43 (3–4): 271–84. doi:10.1080/10826080701202429. ISSN 1082-6084. PMID 18365930.

- ^ Stojek A; Madejski, J; Dedelis, E; Janicki, K (1990). "[Correction of the symptoms of late substance withdrawal syndrome by intra-conjunctival administration of 5% homatropine solution (preliminary report)]". Psychiatr Pol. 24 (3): 195–201. ISSN 0033-2674. PMID 2084727.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Le Bon O; Murphy, JR; Staner, L; Hoffmann, G; Kormoss, N; Kentos, M; Dupont, P; Lion, K; Pelc, I (2003). "Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol post-withdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 23 (4): 377–83. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000085411.08426.d3. ISSN 0271-0749. PMID 12920414.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sanna, E; Mostallino, Mc; Busonero, F; Talani, G; Tranquilli, S; Mameli, M; Spiga, S; Follesa, P; Biggio, G (17 December 2003). "Changes in GABA(A) receptor gene expression associated with selective alterations in receptor function and pharmacology after ethanol withdrawal". The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 23 (37): 11711–24. ISSN 0270-6474. PMID 14684873.

- ^ Idemudia SO, Bhadra S, Lal H (1989). "The pentylenetetrazol-like interoceptive stimulus produced by ethanol withdrawal is potentiated by bicuculline and picrotoxinin". Neuropsychopharmacology. 2 (2): 115–22. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(89)90014-6. PMID 2742726.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chastain, G (October 2006). "Alcohol, neurotransmitter systems, and behavior". The Journal of general psychology. 133 (4): 329–35. doi:10.3200/GENP.133.4.329-335. ISSN 0022-1309. PMID 17128954.

- ^ Ewing JA (1984). "Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 252 (14): 1905–7. doi:10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 6471323.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ CAGE Questionnaire (PDF)

- ^ Dhalla, S.; Kopec, JA. (2007). "The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: a review of reliability and validity studies". Clin Invest Med. 30 (1): 33–41. PMID 17716538.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Alcohol Dependence Data Questionnaire (SADD)

- ^ Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST)

- ^ AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care

- ^ Smith, SG; Touquet, R; Wright, S; Das Gupta, N (1996). "Detection of alcohol misusing patients in accident and emergency departments: the Paddington alcohol test (PAT)". Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 13 (5). British Association for Accident and Emergency Medicine: 308–312. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agh049. ISSN 1351-0622. PMC 1342761. PMID 8894853. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Nurnberger, Jr., John I., and Bierut, Laura Jean. "Seeking the Connections: Alcoholism and our Genes." Scientific American, Apr 2007, Vol. 296, Issue 4.

- ^ New York Daily News (William Sherman) Test targets addiction gene 11 February 2006

- ^ Berggren U, Fahlke C, Aronsson E (2006). "The taqI DRD2 A1 allele is associated with alcohol-dependence although its effect size is small" (Free full text). Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 41 (5): 479–85. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agl043. ISSN 0735-0414. PMID 16751215.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 31 July 1994. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6.

- ^ Jones, AW. (2006). "Urine as a biological specimen for forensic analysis of alcohol and variability in the urine-to-blood relationship". Toxicol Rev. 25 (1): 15–35. doi:10.2165/00139709-200625010-00002. PMID 16856767.

- ^ Das, SK.; Dhanya, L.; Vasudevan, DM. (2008). "Biomarkers of alcoholism: an updated review". Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 68 (2): 81–92. doi:10.1080/00365510701532662. PMID 17852805.

- ^ World Health Organisation (2010). "Alcohol".

- ^ "Alcohol policy in the WHO European Region: current status and the way forward" (PDF). World Health Organisation. 12 September 2005.

- ^ Crews, F.; He, J.; Hodge, C. (2007). "Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 86 (2): 189–99. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001. PMID 17222895.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Gabbard: "Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders". Published by the American Psychiatric Association: 3rd edition, 2001, ISBN 0-88048-910-3

- ^ Blondell, RD. (2005). "Ambulatory detoxification of patients with alcohol dependence". Am Fam Physician. 71 (3): 495–502. PMID 15712624.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Morgan-Lopez, AA.; Fals-Stewart, W. (2006). "Analytic complexities associated with group therapy in substance abuse treatment research: problems, recommendations, and future directions". Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 14 (2): 265–73. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.265. PMID 16756430.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Soyka, M.; Helten, C.; Scharfenberg, CO. (2001). "[Psychotherapy of alcohol addiction--principles and new findings of therapy research]". Wien Med Wochenschr. 151 (15–17): 380–8, discussion 389. PMID 11603209.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Dawson, Deborah A.; Grant, Bridget F.; Stinson, Frederick S.; Chou, Patricia S.; Huang, Boji; Ruan, W. June (2005). "Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001-2002". Addiction. 100 (3): 281. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. PMID 15733237.

- ^ Dawson, Deborah A.; Goldstein, Risë B.; Grant, Bridget F. (2007). "Rates and correlates of relapse among individuals in remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a 3-year follow-up". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 31: 2036. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00536.x.

- ^ Vaillant, GE (2003). "A 60-year follow-up of alcoholic men". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 98 (8): 1043–51. PMID 12873238.

- ^ a b Krampe H, Stawicki S, Wagner T (2006). "Follow-up of 180 alcoholic patients for up to 7 years after outpatient treatment: impact of alcohol deterrents on outcome". Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 30 (1): 86–95. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00013.x. ISSN 0145-6008. PMID 16433735.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ogborne, AC. (2000). "Identifying and treating patients with alcohol-related problems". CMAJ. 162 (12): 1705–8. PMID 10870503.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Soyka, M.; Rösner, S. (2008). "Opioid antagonists for pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence - a critical review". Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 1 (3): 280–91. PMID 19630726.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "FDA Approves New Drug for Treatment of Alcoholism". Retrieved 2006-04-02."

- ^ "Naltrexone or Specialized Alcohol Counseling an Effective Treatment for Alcohol Dependence When Delivered with Medical Management". 2006-05-02.

- ^ New Treatments for Alcoholism (From Mouse to Man) http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/mouse-man/200901/potential-treatments-alcoholism-and-drug-addiction

- ^ Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden CL (2003). "Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 361 (9370): 1677–85. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13370-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 12767733.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Swift RM (2003). "Topiramate for the treatment of alcohol dependence: initiating abstinence". Lancet. 361 (9370): 1666–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13378-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 12767727.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA (2007). "Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 298 (14): 1641–51. doi:10.1001/jama.298.14.1641. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 17925516.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olmsted CL, Kockler DR (2008). "Topiramate for alcohol dependence". Ann Pharmacother. 42 (10): 1475–80. doi:10.1345/aph.1L157. ISSN 1060-0280. PMID 18698008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lindsay, S.J.E.; Powell, Graham E., eds. (28 July 1998). The Handbook of Clinical Adult Psychology (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 402. ISBN 978-0415072151.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Gitlow, Stuart (1 October 2006). Substance Use Disorders: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. pp. 52 and 103–121. ISBN 978-0781769983.

- ^ Johansson BA, Berglund M, Hanson M, Pöhlén C, Persson I (2003). "Dependence on legal psychotropic drugs among alcoholics" (PDF). Alcohol Alcohol. 38 (6): 613–8. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agg123. ISSN 0735-0414. PMID 14633651.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Poulos CX, Zack M (2004). "Low-dose diazepam primes motivation for alcohol and alcohol-related semantic networks in problem drinkers". Behav Pharmacol. 15 (7): 503–12. doi:10.1097/00008877-200411000-00006. ISSN 0955-8810. PMID 15472572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004

- ^ a b Cabinet Office Strategy Unit Alcohol misuse: How much does it cost? September 2003

- ^ WHO European Ministerial Conference on Young People and Alcohol

- ^ WHO to meet beverage company representatives to discuss health-related alcohol issues

- ^ "Alcoholism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/388/sci_drug_addiction.pdf

- ^ Dick DM, Bierut LJ (2006). "The genetics of alcohol dependence". Current psychiatry reports. 8 (2): 151–7. doi:10.1007/s11920-006-0015-1. ISSN 1523-3812. PMID 16539893.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2001-2002 Survey Finds That Many Recover From Alcoholism Press release 18 January 2005.

- ^ Vaillant GE (2003). "A 60-year follow-up of alcoholic men". Addiction. 98 (8): 1043–51. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00422.x. ISSN 0965-2140. PMID 12873238.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Alcoholismus chronicus, eller Chronisk alkoholssjukdom:. Stockholm und Leipzig. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ a b Anonymous (1939, 2001). [www.aa.org Alcoholics Anonymous: the story of how many thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism]. New York City: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. xxxii, 575 p. ISBN 1893007162.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Big Book Self Test:". intoaction.us. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ Kay AB (2000). "Overview of 'allergy and allergic diseases: with a view to the future'". Br. Med. Bull. 56 (4): 843–64. doi:10.1258/0007142001903481. ISSN 0007-1420. PMID 11359624.

- ^ "Alcoholics Anonymous" p XXVI

- ^ "OCTOBER 22 DEATHS". todayinsci.com. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ CDC. (2004). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Guidelines for Referral and Diagnosis. Can be downloaded at http://www.cdc.gov/fas/faspub.htm

- ^ Streissguth, A. (1997). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: A Guide for Families and Communities. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing. ISBN 1-55766-283-5.

- ^ "Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ^ "Economic cost of alcohol consumption". World Health Organization Global Alcohol Database. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ^ "Q&A: The costs of alcohol". BBC. 2003-09-19.

- ^ "World/Global Alcohol/Drink Consumption 2007".

- ^ "The World's Drunks: The Irish".

- ^ Stivers, Richard (2000). Hair of the dog: Irish drinking and its American stereotype. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1218-1.

- ^ http://www.enotalone.com/article/5540.html

- ^ a b c Walter H., Gutierrez K., Ramskogler K., Hertling I., Dvorak A., Lesch O.M (2003). "gender-specific differences in alcoholism: implications for treatment". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 6: 253–268. doi:10.1007/s/00737-003-0014-8.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Karrol Brad R. (2002). "Women and alcohol use disorders: a review of important knowledge and its implications for social work practitioners". Journal of social work. 2 (3): 337–356. doi:10.1177/146801730200200305.

- ^ a b c Blume Laura N., Nielson Nancy H., Riggs Joseph A., et all (1998). "Alcoholism and alcohol abuse among women: report of the council on scientific affairs". Journal of women's health. 7 (7): 861–870. doi:10.1089/jwh.1998.7.861.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Browman, K. E. and J. C. Crabbe (2001, 2002). "Alcoholism: Genetic Aspects". In Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (ed.). International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York, NY: Elsevier. pp. 371–378. ISBN 0080430767.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterdoi=ignored (help)

- Díaz, Héctor Luis and Thomas D. Watts (2005). Alcohol Abuse and Acculturation among Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Sociological Study. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0773461051. OCLC 60311906.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Galanter, Marc (2005). Alcohol Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults: Epidemiology, Neurobiology, Prevention, Treatment. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. ISBN 0306486253. OCLC 133155628 56653179 57724687 71290784.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Goodwin, Donald W. (2000). Alcoholism, the Facts (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK; New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019263061X. OCLC 41834977 42622081 57339357 57621778 70861649.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Hedblom, Jack H. (2007). Last Call: Alcoholism and Recovery. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801886775. OCLC 237901552 77708730.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Mack, Avram H. John E. Franklin, and Richard J. Frances (2001). Concise Guide to Treatment of Alcoholism and Addictions (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 0880488034. OCLC 45500376.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mayes, A. (2001, 2002). "Korsakoff's Syndrome". In Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (ed.). International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York, NY: Elsevier. pp. 8162–8166. ISBN 0080430767.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterdoi=ignored (help)

- McCully, Chris (2004). Goodbye, Mr. Wonderful. Alcoholism, addiction, and early recovery. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 184310265X. OCLC 24107485.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Etiology and Natural History of Alcoholism.

- O'Farrell, Timothy J. and William Fals-Stewart (2006). Behavioral Couples Therapy for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN 1593853246. OCLC 64336035.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Pence, Gregory, "Kant on Whether Alcoholism is a Disease," Ch. 2, The Elements of Bioethics, McGraw-Hill Books, 2007 ISBN 0-073-13277-2.

- Perkinson, Robert R. (2004). Treating Alcoholism: Helping Your Clients find the Road to Recovery. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471658065. OCLC 54905506 56645146 70720151.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Plant, Martin A. and Moira Plant (2006). Binge Britain: Alcohol and the National Response. Oxford, UK; New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199299404. OCLC 238809013 64554668.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Smart, Lesley (2007). Alcohol and Human Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199237357. OCLC 163616466.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Soyka, M. (2001, 2002). "Alcohol-Related Disorders". In Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (ed.). International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York, NY: Elsevier. pp. 359–365. ISBN 0080430767.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterdoi=ignored (help)

- Stimmel, Barry (2002). Alcoholism, Drug Addiction, and the Road to Recovery: Life on the Edge. New York: Haworth Medical Press. ISBN 0789005530. OCLC 46575047 52287994 59502027.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Sutton, Philip M. (2007). "Alcoholism and Drug Abuse". In Michael L. Coulter, Stephen M. Krason, Richard S. Myers, and Joseph A. Varacalli (ed.). Encyclopedia of Catholic Social Thought, Social Science, and Social Policy. Lanham, MD; Toronto, Canada; Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 9780810859067.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- Thatcher, Richard (2004). Fighting Firewater Fictions: Moving beyond the Disease Model of Alcoholism in First Nations. Toronto, Canada; Buffalo, NY: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802089852. OCLC 55473625.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Tracy, Sarah W. (2005). Alcoholism in America: From Reconstruction to Prohibition. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801881196. OCLC 56876909.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

- Warren Thompson, MD, FACP. "Alcoholism." Emedicine.com, June 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- Alcohol Rehab Clinics