Economy of New Zealand

| |

| Currency | 1 New Zealand dollar (NZD$) = 100 cents |

|---|---|

| 1 April – 31 March | |

Trade organisations | APEC, WTO and OECD |

| Statistics | |

| GDP | US$135.723 billion (2010 est.)[1] |

GDP growth | 1.4% (YTD December 2011 est.)[2] |

GDP per capita | $28,000 (2011 est.)[3] |

GDP by sector | Agriculture (4.7%), industry (24%), services (71.3%) (2011 est.) |

| 0.8% (YTD September 2012 Statistics New Zealand)[4] | |

Population below poverty line | n/a |

| 36.2 (1997) | |

Labour force | 2.353 million (2011 est.) |

Labour force by occupation | Agriculture (7%), industry (19%), services (74%) (2006 est.) |

| Unemployment | 6.6 % (1st quarter)[5] |

Main industries | Food processing, textiles, machinery and transportation equipment, finance, tourism (to NZ), mining (in NZ) |

| External | |

| Exports | $40.92 billion (2011 est.) |

Export goods | Dairy products, meat, wood and wood products, fish, machinery |

Main export partners | Australia 23.1%, China 11.2%, U.S. 8.6%, Japan 7.8% (2010) |

| Imports | $35.07 billion (2011 est.) |

Import goods | Machinery and equipment, vehicles and aircraft, petroleum, electronics, textiles, plastics |

Main import partners | Australia 18.1%, China 16%, U.S. 10.5%, Japan 7.4%, Germany (4.1%) (2010) |

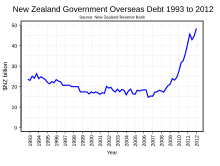

Gross external debt | $256.4 billion (125.3% of GDP) (2012 est.)[6] |

| Public finances | |

| 33.7% of GDP (2011 est.) | |

| Revenues | $61.94 billion (2011 est.) |

| Expenses | $75.31 billion (2011 est.) |

| Economic aid | donor: $99.7 million (FY99/00) |

| US$20.626 billion (March 2011)[9] | |

New Zealand has a market economy that is greatly dependent on international trade, mainly with Australia, the European Union, the United States, China, South Korea and Japan. It has only small manufacturing and high-tech sectors, being strongly focused on tourism and primary industries such as agriculture. Free-market reforms of recent decades have removed many barriers to foreign investment, and the World Bank in 2005 praised New Zealand as being the most business-friendly country in the world, before Singapore.[10][11]

Profile

| Year | Gross Domestic Product (NZ$ millions) |

1 US dollar exchange | Inflation index (2000=100) |

Per capita income (as % of USA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 22,976 | NZD 1.02 | 30 | 58.67 |

| 1985 | 45,003 | NZD 2.00 | 53 | 38.93 |

| 1990 | 73,745 | NZD 1.67 | 84 | 55.80 |

| 1995 | 91,881 | NZD 1.52 | 93 | 59.02 |

| 2000 | 114,563 | NZD 2.18 | 100 | 38.98 |

| 2005 | 154,108 | NZD 1.41 | 113 | 62.99 |

Traditionally, New Zealand's economy was built upon on a narrow range of primary products, such as wool, meat and dairy products. As an example, from approximately 1920 to the late 1930s, the dairy export quota was usually around 35% of the total exports, and in some years made up almost 45% of all New Zealand's exports.[13] Due to the high demand for these primary products – such as the New Zealand wool boom of 1951 – New Zealand enjoyed high standards of living. However, commodity prices for these exports declined, and New Zealand lost its preferential trading position with the United Kingdom in 1973, due to the latter joining the European Economic Community. Partly as a result, from 1970 to 1990, the relative New Zealand purchasing power adjusted GDP per capita declined from about 115% of the OECD average to 80%.[14]

New Zealand's economy has traditionally been based on a foundation of exports from its very efficient agricultural system. Leading agricultural exports include meat, dairy products, forest products, fruit and vegetables, fish, and wool. New Zealand was a direct beneficiary of many of the reforms achieved under the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, with agriculture in general and the dairy sector in particular enjoying many new trade opportunities in the long term. The country has substantial hydroelectric power and sizeable reserves of natural gas, much of which is exploited due primarily to major Keynesian import substitution-oriented industrial projects (See Think Big). Leading manufacturing sectors are food processing, metal fabrication, and wood and paper products. Some manufacturing industries, many of which had only been established in a climate of import substitution with high tariffs and subsidies, such as car assembly, have completely disappeared, and manufacturing's importance in the economy is in a general decline.

Liberalisation

Since 1984, the government of New Zealand has undertaken major economic restructuring (known first as Rogernomics and then Ruthanasia), moving an agrarian economy dependent on concessionary British market access toward a more industrialised, free market economy that can compete globally. This growth has boosted real incomes, broadened and deepened the technological capabilities of the industrial sector, and contained inflationary pressures. Inflation remains among the lowest in the industrial world. Per capita GDP has been moving up towards the levels of the big West European economies since the trough in 1990, but the gap remains significant. New Zealand's heavy dependence on trade leaves its growth prospects vulnerable to economic performance in Asia, Europe, and the United States.

Between 1984 and 1999, a number of measures of New Zealand's economic and social capital showed a steady decline: the youth suicide rate grew sharply into one of the highest in the developed world;[15] the number of food banks increased dramatically;[16] marked increases in violent and other crime were observed;[17] the number of New Zealanders estimated to be living in poverty grew by at least 35% between 1989 and 1992;[18] and health care was especially hard-hit, leading to a significant deterioration in health standards among working and middle-class people.[19]

Between 1985 and 1992, New Zealand's economy grew by 4.7% during the same period in which the average OECD nation grew by 28.2%.[20] From 1984–1993 inflation averaged 9% per year, New Zealand's credit rating dropped twice, and foreign debt quadrupled.[18] Between 1986 and 1993, the unemployment rate rose from 3.6% to 11%.[21]

Outlook and challenges

The New Zealand economy has recently been perceived as successful. However, the generally positive outlook includes some challenges. New Zealand income levels, which used to be above much of Western Europe prior to the deep crisis of the 1970s, have never recovered in relative terms. The New Zealand GDP per capita is for instance less than that of Spain and about 60% that of the United States. Income inequality has increased greatly, implying that significant portions of the population have quite modest incomes. Further, New Zealand has a very large current account deficit of 8–9% of GDP. Despite this, its public debt stands at 33.7% (2011 est.)[22] of the total GDP, which is small compared to many developed nations. However, between 1984 and 2006, net foreign debt increased 11-fold, to NZ$182 billion, NZ$45,000 for each person.[10]

The combination of a modest public debt and a large net foreign debt reflects that most of the net foreign debt is held by the private sector. At 31 June 2012, gross foreign debt was NZ$256.4 billion, or 125.3% of GDP.[23] At 31 March 2012, net foreign debt was NZ$141.65 billion or 104.4% of GDP.[24]

New Zealand's persistent current account deficits have two main causes. The first is that earnings from agricultural exports and tourism have failed to cover the imports of advanced manufactured goods and other imports (such as imported fuels) required to sustain the New Zealand economy. Secondly, there has been an investment income imbalance or net outflow for debt-servicing of external loans. The proportion of the current account deficit that is attributable to the investment income imbalance (a net outflow to the Australian-owned banking sector) grew from one third in 1997 to roughly 70% in 2008.[25]

History

Regulation and welfare state

Historically, New Zealand had a highly protected, regulated and subsidised economy. This stemmed at least partly from trends started in the first half of the 20th century, when the First Liberal Government and later the First Labour Government introduced social security systems with, for the time, very wide-ranging scope (from state pensions to unemployment benefits and free education and health care), while also regulating industry, mandating trade unionism and industrial arbitration. Imports were also heavily regulated. While called "welfare statism" by some,[who?] it was accepted that until at least the 1950s both main parties (Labour and National) generally supported this trend, even though critics pointed to negative effects on the general economy and argued that increasing emigration could be blamed to a large degree on these policies.[26]

By the 1960s, the New Zealand economy's terms of trade began to decline. This was largely due to the decline in export receipts from the United Kingdom, which in 1955 took 65.3 percent of New Zealand's exports. By the year ended June 1973, during which Britain formally entered the European Economic Community, this had fallen to 26.8 percent. By the year ended June 1990 its share had fallen to 7.2 percent and in the year ended June 2000 its share was 6.2 percent.[27]

To a substantial degree, the economic restrictions remained in place or were even sometimes extended in the early second half of the 20th century. However, reforms in the 1980s and early 1990s were then to turn this situation into its opposite.

Reform and liberalisation

Between 1984 and 1995, successive New Zealand governments enacted policies of economic deregulation informed by microeconomics. The policies aimed to liberalise the economy and were notable for their very comprehensive coverage and innovations. Specific polices included: floating the exchange rate; establishing an independent reserve bank; performance contracts for senior civil servants; public sector finance reform based on accrual accounting; tax neutrality; subsidy-free agriculture; and industry-neutral competition regulation. Economic growth was resumed in 1991. New Zealand was changed from a somewhat closed and centrally controlled economy to one of the most open economies in the OECD.[28]

Since 1984, government subsidies including agricultural subsides were eliminated; import regulations were liberalised; the exchange rate was floated; and controls on interest rates, wages, and prices were removed; and marginal rates of taxation were reduced. Tight monetary policy and major efforts to reduce the government budget deficit brought the inflation rate down from an annual rate of more than 18% in 1987. The deregulation of government-owned enterprises in the 1980s and 1990s reduced government's role in the economy and permitted the retirement of some public debt.

Deregulation created a very business-friendly regulatory framework. A 2008 study and survey ranked it 99.9% in "Business freedom", and 80% overall in "Economic freedom", noting amongst other things that it only takes 12 days to establish a business in New Zealand on average, compared with a worldwide average of 43 days. Other indicators measured were property rights, labour market conditions, government controls and corruption, the last being considered "next to non-existent" in the Heritage Foundation and Wall Street Journal study.[29]

According to the Heritage Foundation, New Zealand has the strongest private property rights in the world, scoring 95 on a scale of 100.

In its 'Doing Business 2008' survey, the World Bank (which in that year rated New Zealand as the second-most business-friendly country worldwide), ranked New Zealand 13th out of 178 in the business-friendliness of its hiring laws.[30]

The 1990s liberalisations also have been blamed for a number of significant negative effects. One of them was the leaky homes crisis, where the liberalisation of building standards (in the expectation that market forces would assure quality) led to many thousands of severely deficient buildings (mostly residential homes and apartments) being constructed over a period of a decade. The costs of fixing the damage has been estimated at over NZ$11 billion.[31]

Recent trends

Economic growth, which had slowed in 1997 and 1998 due to the negative effects of the Asian financial crisis and two successive years of drought, rebounded in 1999. A low New Zealand dollar, favourable weather, and high commodity prices boosted exports, and the economy is estimated to have grown by 2.5% in 2000. Growth resumed at a higher level from 2001 onwards due primarily to the lower value of the New Zealand dollar, which made exports more competitive. The return of substantial economic growth led the unemployment rate to drop from 7.8% in 1999 to 3.4% in late 2005, the lowest rate in nearly 20 years.

Although New Zealand enjoyed low unemployment rates in the years immediately prior to the financial crisis beginning in 2007, subsequent unemployment rose.

New Zealand's large current account deficit, which stood at more than 6.5% of GDP in 2000, has been a constant source of concern for New Zealand policymakers and hit 9% as of March 2006.[citation needed] The rebound in the export sector is expected to help narrow the deficit to lower levels, especially due to decreases in the exchange rate of the New Zealand dollar during 2008.

Foreign business relations

New Zealand's economy has been helped by strong economic relations with Australia. Australia and New Zealand are partners in "Closer Economic Relations" (CER), which allows for free trade in goods and most services. Since 1990, CER has created a single market of more than 25 million people, and this has provided new opportunities for New Zealand exporters. Australia is now the destination of 19% of New Zealand's exports, compared to 14% in 1983.[citation needed] Both sides have also agreed to consider extending CER to product standardisation and taxation policy. New Zealand initiated a free trade agreement with Singapore in September 2000 which was extended in 2005 to include Chile and Brunei and is now known as the P4 agreement. New Zealand is seeking other bilateral/regional trade agreements in the Pacific area.[citation needed]

U.S. goods and services have been competitive in New Zealand, though the then-strong U.S. dollar created challenges for U.S. exporters in 2001. The market-led economy offers many opportunities for U.S. exporters and investors. Investment opportunities exist in chemicals, food preparation, finance, tourism, and forest products, as well as in franchising. The best sales prospects are for medical equipment, information technology, and consumer goods. On the agricultural side, the best prospects are for fresh fruit, snack foods, specialised grocery items (e.g. organic foods), and soybean meal. A number of U.S. companies have subsidiary branches in New Zealand. Many operate through local agents, with some joint venture associations. The United States Chamber of Commerce is active in New Zealand, with a main office in Auckland and a branch committee in Wellington.

However, as of the 2010s, China is now New Zealand's second-largest trading partner, behind Australia.[32][33] On 17 June 2010, Xi Jinping, China's vice-president, travelled to Auckland, New Zealand for a three-day visit, along with more than 100 senior business leaders.[34]

New Zealand welcomes and encourages foreign investment without discrimination. The Overseas Investment Commission (OIC) must however give consent to foreign investments that would control 25% or more of businesses or property worth more than NZ$50 million. Restrictions and approval requirements also apply to certain investments in land and in the commercial fishing industry. In practice, OIC approval requirements have not hindered investment. OIC consent is based on a national interest determination, but no performance requirements are attached to foreign direct investment after consent is given. Full remittance of profits and capital is permitted through normal banking channels.

This free investment by foreign capital has also been criticised. Groups like Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) consider that New Zealand's economy is substantially overseas-owned, noting that direct ownership of New Zealand companies by foreign parties increased from $9.7 billion in 1989 to $83 billion in 2007 (an over 700% increase), while 41% of the New Zealand sharemarket valuation is now overseas-owned, compared to 19% in 1989. Around 7% of all New Zealand agriculturally productive land is also foreign-owned. CAFCA considers that the effect of such takeovers has generally been negative in terms of jobs and wages.[10]

Unemployment

Prior to the economic shocks which occurred upon Britain's joining the EEC in the 1970s and closing as a primary New Zealand export market, measured unemployment in New Zealand was very low. In 1959 and 1960, for example, the country was officially at full employment.[35] One Labour party representative recently joked in a speech that the Prime Minister of the day knew the name of every unemployed person.[36]

In the middle 2000s, the national unemployment rate stood at 3.4% (December 2007), its lowest level since the current method of surveying began in 1986. This gave the country the 5th-best ranking in the OECD (with an OECD average at the time of 5.5%). The low numbers correlated with a robust economy and a large backlog of job positions at all levels.[37] It is worth noting, however, that unemployment numbers are not always directly comparable between OECD nations, as they do not all measure voluntary and involuntary separation from the labour market in the same way.

The percentage of the population employed also increased in recent years, to 68.8% of all inhabitants, with full-time jobs increasing slightly, and part-time occupations decreasing in turn. The increase in the working population percentage is attributed to increasing wages and higher costs of living moving more people into employment.[37] The low unemployment also had some disadvantages, with many companies unable to fill jobs.

In the late 2000s, mainly as a result of the global financial crisis, unemployment numbers rose to a 10-year high of 6% in mid-2009, with job losses especially high amongst women. Seasonally adjusted employment levels fell 0.4 per cent to 2.17 million people, while the number of unemployed rose to 138,000 people.[38]

Taxation

As of 2010, New Zealand had the second-lowest personal tax burden in the OECD, once all compulsory effects (such as superannuation and other mandatory deductions) were included in the tax-take. Only Mexico's citizens had a higher percentage-wise "take home" proportion of their salaries.[39]

There is an ongoing political debate between left-leaning and right-leaning political parties as to whether further lowering taxes is appropriate. One of the most contentious questions is whether to adjust the relative tax burden of the highest-income earners.[citation needed]

Corruption Perceptions Index

New Zealand is the highest ranked (i.e. least corrupt) country on the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of 2011.[40]

Other indicators

Industrial Production Growth Rate: 5.9% (2004) / 1.5% (2007)

Household income or consumption by percentage share:

- Lowest 10%: 0.3% (1991)

- Highest 10%: 29.8% (1991)

Agriculture – Products: wheat, barley, potatoes, pulses, fruits, vegetables; wool, beef, dairy products; fish

Exports – commodities: dairy products, meat, wood and wood products, fish, machinery

Imports – commodities: machinery and equipment, vehicles and aircraft, petroleum, electronics, textiles, plastics

Electricity:

- Electricity – consumption: 34.88 TWh (2001) / 37.39 TWh (2006)

- Electricity – production: 38.39 TWh (2004) / 42.06 TWh (2006)

- Electricity – exports: 0 kWh (2006)

- Electricity – imports: 0 kWh (2006)

Electricity – Production by source:[42]

- Hydro: 55.6% (2010)

- Geothermal: 9,9% (2010)

- Wind: 2,9% (2010)

- Fossil Fuel: 28.2% (2010)

- Nuclear: 0% (2010)

- Other: 3.4% (2010)

Oil:

- Oil – production: 42,160-barrel (6,703 m3) 2001 / 25,880-barrel (4,115 m3) 2006

- Oil – consumption: 132,700-barrel (21,100 m3) 2001 / 156,000-barrel (24,800 m3) 2006

- Oil – exports: 30,220-barrel (4,805 m3) 2001 / 15,720-barrel (2,499 m3) 2004

- Oil – imports: 119,700-barrel (19,030 m3) 2001 / 140,900-barrel (22,400 m3) 2004

- Oil – proven reserves: 89.62-million-barrels (14,248,000 m3) January 2002

Exchange rates:

New Zealand Dollars (NZ$) per US$1 – 1.2652 (2012), 1.3869 (2005), 1.5248 (2004), 1.9071 (2003), 2.1622 (2002), 2.3788 (2001), 2.2012 (2000), 1.8886 (1999), 1.8632 (1998), 1.5083 (1997), 1.4543 (1996), 1.5235 (1995)

See also

- Agriculture in New Zealand

- Telecommunications in New Zealand

- Energy in New Zealand

- Transport in New Zealand

- Reserve Bank of New Zealand

- New Zealand Electricity Market

- Economy of Oceania

- Ministry of Economic Development (New Zealand)

- Foreign relations of New Zealand#Trade

References

- ^ "New Zealand". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product: December 2011 quarter". Statistics New Zealand. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook". CIA. 6 November 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Inflation running at 0.8 pc in September year". Statistics New Zealand. 16 October 2012.

- ^ "New Zealand: Unemployment rate decreased to 6.6% in QI". www.liteforex.org. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ "External Debt New Zealand". Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (15 April 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "International Reserves and Foreign Currency Liquidity – NEW ZEALAND". International Monetary Fund. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ a b c McCarten, Matt (14 January 2007). "Foreign owners muscle in as New Zealand sells off all its assets". The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ "New Zealand rated most business-friendly". International Herald Tribune. 14 September 2005.

- ^ IMF

- ^ McKinnon, Malcolm, ed. (1997). New Zealand Historical Atlas, Plate 61. David Bateman.

- ^ Drew, Aaron. "New Zealand's productivity performance and prospects" (PDF). Bulletin. 70 (1). Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ Wasserman, Danuta; Cheng, Qi; Jiang, Guo-Xin (1 June 2005). "Global suicide rates among young people aged 15-19". World Psychiatry. 4 (2): 114–20. PMC 1414751. PMID 16633527.

- ^ Ballard, Keith (14 October 2003). "Inclusion, exclusion, poverty, racism and education: An outline of some present issues" (DOC).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ian Ewing. (31 July 2001). Crime in New Zealand (PDF). Statistics New Zealand. p. 9. ISBN 0-478-20773-5.

- ^ a b Kelsey, Jane (9 July 1999). "Life in the economic test tube: New Zealand "experiment" a colossal failure".

- ^ Bramhall, Stuart MD (9 January 2003). "The New Zealand Health Care System". Physicians for a National Health Program.

- ^ http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=SNA_TABLE1}

- ^ http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=LFS_SEXAGE_I_R

- ^ "New Zealand". The World Fact Book. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "E3 New Zealand's overseas debt". Reserve Bank of New Zealand. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Balance of Payments and International Investment Position: March 2012 quarter". Statistics New Zealand. 21 March 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Bertram, Geoff (2009). "The banks, the current account, the financial crisis and the outlook" (PDF). Policy Quarterly. 5 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Revolt of the Guinea Pigs". Time. 12 December 1949.

- ^ "New Zealand's Export Markets year ended June 2000 (provisional)". Statistics New Zealand. 2000. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Evans, Lewis; Grimes, Arthur; Wilkinson, Bryce (1996.). "Economic Reform in New Zealand 1984-95: The Pursuit of Efficiency". Journal of Economic Literature. 34(4): 1856–1902. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Survey ranks NZ in top six for economic freedom". The New Zealand Herald. 16 January 2008.

- ^ "Economy Rankings". Doing Business website. World Bank. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Rudman, Brian (18 September 2009). "Government must plug those leaks". The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ Business Desk/NZPA (17 June 2010). "China offered NZ recession buffer". Stuff. Fairfax.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ China offered New Zealand, China to enhance tripartite partnership between universities 18 June 2010, globaltimes.cn

- ^ ONE News/Newstalk ZB (17 June 2010). "China's Vice President visits New Zealand". Television NZ Ltd.

- ^ "An Economic History of New Zealand in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries". 11 August 2011.

- ^ Phil Goff (11 December 2006). "Succeeding in a Globalised World: The New Zealand Experience". Speech. New Zealand Government.

- ^ a b Daly, Michael (7 February 2008). "Unemployment at record low as job growth surges". New Zealand Herald. APN Holdings. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ "Unemployment surges to 9 year high". New Zealand Herald. APN Holdings. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Dickison, Michael (12 May 2010). "NZ earners' tax burden second-lowest in OECD". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2011 Table". Transparency International. 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Corporate Overview (from the Tourism New Zealand corporate website. Retrieved 30 September 2007)

- ^ "Electricity in New Zealand" (PDF). NZ Electricity Authority/Te Mana Hiko. 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Dalziel, P. (2002). "New Zealand's Economic Reforms: An assessment". Review of Political Economy. 14 (1): 31–45.

- Easton, B. (1994). "Economic and other ideas behind the New Zealand reforms" (PDF). Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 10 (3): 78–94.

- Evans, L.; Grimes, A.; Bryce, W.; Teece, D. (1996). "Economic Reform in New Zealand 1984–95: The Pursuit of Efficiency". Journal of Economic Literature. 34 (4): 1856–1902.

- Harcourt, T. (2005). Closer Economic Relations. Australian Trade Commission Website

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook (2024 ed.). CIA. (Archived 2005 edition.)

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook (2024 ed.). CIA. (Archived 2005 edition.)

External links

- OECD's New Zealand country Web site and OECD Economic Survey of New Zealand

- Ministry of Economic Development Web site

- Statistics New Zealand Web site

Template:South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC)