Filipino Americans: Difference between revisions

Kagoikunai (talk | contribs) →Population: The Fil-Am community stands at 3.1 million, full and part-Filipinos, regardless of citizenship. |

Kagoikunai (talk | contribs) Removal of percentage is unexplained and somewhat biased, for EVERY ARTICLE IN WIKIPEDIA FOR ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE UNITED STATES HAS IT! |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

|year=2007 |

|year=2007 |

||

|quote=There are an estimated four million Americans of Philippine ancestry in the United States, and more than 250,000 American citizens in the Philippines. |

|quote=There are an estimated four million Americans of Philippine ancestry in the United States, and more than 250,000 American citizens in the Philippines. |

||

|accessdate=2007-09-02}}</ref> Million''' |

|accessdate=2007-09-02}}</ref> Million'''<br/><small>1.5% of the US population (2007)</small> |

||

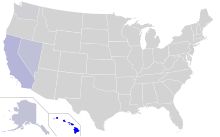

|popplace = [[Western United States|West]], [[Northeastern United States|Northeast]], [[Southern United States|South]], [[Chicago Metropolitan Area|Chicago]] |

|popplace = [[Western United States|West]], [[Northeastern United States|Northeast]], [[Southern United States|South]], [[Chicago Metropolitan Area|Chicago]] |

||

|langs = [[American English]], [[Tagalog language|Tagalog]], [[Ilocano language|Ilocano]], [[Kapampangan language|Kapampangan]], [[Pangasinan language|Pangasinan]], [[Bikol languages|Bikolano]], [[Visayan languages]], [[Languages of the Philippines|others]] |

|langs = [[American English]], [[Tagalog language|Tagalog]], [[Ilocano language|Ilocano]], [[Kapampangan language|Kapampangan]], [[Pangasinan language|Pangasinan]], [[Bikol languages|Bikolano]], [[Visayan languages]], [[Languages of the Philippines|others]] |

||

|rels = Predominantly [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholic]]; minorities of [[Protestantism]], [[Islam]], [[Atheism]], [[Agnosticism]], [[Buddhism]], and other. |

|rels = Predominantly [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholic]]; minorities of [[Protestantism]], [[Islam]], [[Atheism]], [[Agnosticism]], [[Buddhism]], and other. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 07:09, 3 February 2009

Veronica De La CruzAllan PinedaGov. Ben Cayetano Notable Filipino Americans: Cristeta Comerford, LTG Edward Soriano, Eleanor Mariano, Veronica De La Cruz, Allan Pineda, Ben Cayetano | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| West, Northeast, South, Chicago | |

| Languages | |

| American English, Tagalog, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Bikolano, Visayan languages, others | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic; minorities of Protestantism, Islam, Atheism, Agnosticism, Buddhism, and other. |

Filipino Americans (Filipino: Pilipino Amerikano) are citizens of the United States of Philippine ancestry, which trace back to the Philippines, an archipelagic nation in Southeast Asia. They share socio-cultural traditions and self-identity based on the multi-languages and culture of the Philippines. Filipino Americans reside mainly in the continental United States and form significant populations in Hawaii, Alaska, Guam, and Northern Marianas.

The earliest Filipino Americans to arrive in the New World landed in 1763 and created a settlement in Saint Malo, Louisiana. They were pressed sailors escaping from the cruelty of Spanish galleons and were "discovered" in America in 1883 by a Harper's Weekly journalist. Other Filipino American settlements appeared throughout the bayous of Louisiana with the Manila Village in Barataria Bay being the largest. Some immigration occurred with the need for menial rural labor in the late 1800s, with Filipino Americans settling primarily in Hawaii and California. Roughly another two hundred years would pass before significant numbers arrived in the Americas in the last half of the 20th century starting in the 1970s, mostly settling in California. Some came looking for political freedom, but most arrived looking for employment and a better life for their families.

Demographics

Population

The Filipino American ("Fil-Am" for short) community is the second largest Asian American subgroup and the largest Southeast Asian American group. Filipino Americans are also the largest subgroup of the Overseas Filipinos.[3]

A 2007 U.S. Census Bureau survey reported that the Filipino American community stood at about 3.1 million. The census also found that about 80% of the Filipino community are United States citizens.[1] Also in 2007, the U.S. State Department estimated the size of the Filipino American community at 4 million.[2] or 1.5% of the United States population.[citation needed] There are no official records of Filipinos who hold dual citizenship.

Settlement

The first permanent Filipino settlement in North America was established in 1763 in Saint Malo, Louisiana. Other settlements appeared throughout the bayous of Louisiana with the Manila Village in Barataria Bay being the largest.

Mass migration, however, occurred at around the end of the Nineteenth century, when the demand for labor in the plantations of Hawaiʻi and farmlands of California attracted thousands of mostly male laborers. Due to their isolation and enforced segregation, the migrants created the first Little Manilas in urban areas.

Unlike other Asian Americans, such as the Chinese and the Vietnamese, they have had a tendency to settle in a more dispersed fashion, living in communities across the country, many of them living in communities with a highly diverse population. Most of them live in the suburbs or in master planned communities.

In areas with sparse Filipino populations, Fil-ams often form loosely-knit social organizations aimed at maintaining a "sense of family", which is a key feature of Filipino culture. Such organizations generally arrange social events, especially of a charitable nature, and keep members up-to-date to local events. While these events are well-attended, the associations are otherwise a small part of the Fil-am life. Fil-ams also have formed close-knit neighborhoods of their own, notably in California and Hawaiʻi. A few townships in these parts of the country have established "Little Manilas", civic and business districts tailored for the Filipino American community. As of 2008, one out of every four Filipino Americans make their home in Southern California, numbering over 1 million[4]. Greater Los Angeles is the metropolitan area home to the most Filipino Americans, with the population numbering around 370,000. Los Angeles County alone accounts for over 262,000 Filipinos, the most of any single county in the U.S. The City of Los Angeles designated a section of Westlake as Historic Filipinotown.

San Diego County is second place in the nation, with nearly 200,000 Filipinos[5]. In addition, San Diego is the only metropolitan area in the U.S. where Filipinos constitute the largest Asian American nationality. A portion of California State Route 54 in San Diego is officially named the "Filipino-American Highway", in honor of the Filipino-American Community. Orange County also has a sizable and growing Filipino population.

San Francisco also has a large Filipino American community while metropolitan areas such as Chicago, Atlanta, Houston, Las Vegas, Phoenix, Washington, D.C. and Seattle are also seeing dramatic growth in their Filipino populations. The entire state of Hawaii had a Filipino population of 275,000 (2000 Census). The entire state of Washington had a Filipino Population of 252,000.

New York City is home to 215,000 Filipinos.[6] It annually hosts the Philippine Independence Day Parade, which is traditionally held on the first Sunday of June at Madison Avenue. The celebration occupies nearly twenty-seven city blocks which includes a 3.5-hour parade and an all-day long street fair and cultural performances. Devout attendees include Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Senator Charles Schumer.

The Southern United States is also known for having a large Filipino American population as well, and is largest Asian minority in the region, which contains about 11% of Filipino Americans.[7]

In June 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and representatives of U.S. President George W. Bush presided over the grand opening and dedication of the Filipino Community Center in Waipahu, Hawaiʻi. It is the largest Filipino American institution in the United States, with the goal of preserving Filipino American history and culture.

Culture

Background

Filipino culture is a combination of indigenous Austronesian civilizations and influences of Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Arab, American, and Spanish cultures.

Culturally, the Philippines is a Westernized country in Asia, a legacy of Spanish and American colonial rule. Reflecting its four hundred years of Spanish rule, many Filipinos but not all are distinguishable from other Asians by having a Hispanic-sounding surname (see: Catálogo alfabético de apellidos) and by being raised in (and many practicing) the Catholic religion. Some Filipinos still retain native surnames, which are characterized by repeating syllables (e.g., Cayubyub) or more frequently multi-syllabic (e.g., Lingayan). The other major religion is Islam, prevalent in the Southern Philippines (Mindanao). True to its western attitudinal reference, many Filipinos speak English, a holdover from American hegemony in its educational system.

Language

There are over 170 languages in the Philippines of which have thousands of Spanish loan words in 170 indigenous Philippine languages; almost all of them belong to the Austronesian language family. Of all of these languages, only 2 are considered official in the country, at least 10 are considered major and at least 8 are considered co-official. Filipinos speak Tagalog, Ilokano, Kapampangan, Visayan languages, Bikolano, and other Philippine languages at home. However, an overwhelming majority of Filipinos are fluent in English since it is one of the official languages in the Philippines and many Filipino American parents urge their children to enhance their English-language skills.

Tagalog is the fifth most-spoken language in the United States, with 1.262 million speakers.[8] The standardized version of this language is officially known as Filipino. Many Filipino American civic organizations and Philippine consulates offer Filipino language courses.

Many of California's public announcements and correspondences are translated into Tagalog due to the large constituency of Filipino Americans in the Golden State. Tagalog is also taught in public schools as a foreign language course, as well as in higher education. Another significant Filipino language is Ilokano, which is taught in school as a foreign language course.

Fluency in Tagalog, Ilokano, Kapampangan, Visayan and in the other languages of the Philippines tend to be lost among second- and third-generation Filipino Americans. This has sometimes created a language barrier between older and younger generations.

Religion

Filipino American religious beliefs and values are rooted in their Christian heritage. This is caused by the introduction, and subsequent adoption, of Catholicism and Christian values by Filipinos as a result of nearly 400 years of Spanish colonial rule.

In New York, the first-ever Church for Filipinos, San Lorenzo Ruiz Church, is hosted by the city. It is named after the first saint from the Philippines, San Lorenzo Ruiz. This is officially designated as the Church for Filipinos in July 2005, the first in the United States, and the second in the world, after a church in Rome.[9]

There are other religious faiths with smaller numbers of Filipino American adherents, including various Protestant denominations, Islam, Buddhism, Taoism, and Hinduism. Atheism and Agnosticism also exist.

Socioeconomic

Economics

Most Filipino-Americans belong to the middle class.[10][11][12] The representation of Filipinos is high in service-oriented professions such as education and healthcare. When compared to other Asian American groups (other than Asian Indians), many Filipino Americans had a strong median household income. [13]

| Ethnicity | Household Income |

|---|---|

| Asian Indians | $68,771 |

| Filipinos | $65,700 |

| Chinese | $57,433 |

| Japanese | $53,763 |

| Koreans | $43,195 |

| Total US Population | $44,684 |

Among Overseas Filipinos, Filipino Americans are the largest senders of US dollars to the Philippines. In 2005, their combined dollar remittances reached a record-high of almost $6.5 billion dollars. In 2006, Filipino Americans sent more than $8 billion, which represents 57% of the total amount received by the Philippines.[15]

Many Filipino Americans are small business-owners. Filipino Americans own restaurants, while others are in the medical, dental, and optical fields. Several are in the telemarketing business. Over 125,000 businesses are Filipino-owned, according to the 2002 US Economic Census.[16] These firms employ more than 132,000 people and generate an almost $14.2 billion in revenue. Of these businesses, 38.6% are health care and social assistance oriented and produces 39.3% of the collective Filipino-owned business revenue. California had the most number of these businesses followed by Hawaiʻi, New York, Illinois, New Jersey, Florida, and Texas.[16]

At the point of retirement, Filipino Americans tend to head back to the Philippines, because of the significance of the dollar in the Philippine economy. Current Philippine president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo has encouraged the Filipino American community business entrepreneurs to invest back home to promote more job-creation in the Philippines.

Education

Filipino Americans have some of the highest educational attainment rates in the United States with 47.9% of all Filipino Americans over the age of 25 having a Bachelor's degree, which correlates with rates observed in other Asian American subgroups.[14]fig.11

The recent wave of Filipino professionals filling the education, healthcare, and information technology shortages in the United States also accounts for the high educational attainment rates.

| Ethnicity | High School Graduation Rate | Bachelor's Degree or More |

|---|---|---|

| Filipinos | 90.2% | 47.9% |

| Chinese | 80.8% | 50.2% |

| Japanese | 93.4% | 43.7% |

| Koreans | 90.2% | 50.8% |

| Total US Population | 83.9% | 27.0% |

In California, Filipino Americans are more likely to graduate from college than their Asian American counterparts. Due to the strong American influence in the Philippine education system, first generation Filipino immigrants are also an advantage in gaining professional licensure in the United States. According to a study conducted by the American Medical Association, Philippine-trained physicians comprise the second largest group of foreign-trained physicians in the United States (20,861 or 8.7% of all practicing international medical graduates in the U.S.). [17] In addition, Filipino American dentists, who have received training in the Philippines, also comprise the second largest group of foreign-trained dentists in the United States. In an article from the Journal of American Dental Association, 11% of all foreign-trained dentists licensed in the U.S. are from the Philippines; India is ranked first with 25.8% of all foreign dentists.[18] The familiar trend of Filipino Americans and Filipino immigrants entering health care jobs is well observed in other allied health professional such as nursing, physical therapy, radiologic technology and medical technology.

Similarities in quality and structure of the nursing curriculum in the Philippines and the United States had led to the migration of thousands of nurses from the Philippines to fill the shortfall of RNs in the United States. Since the 1970s and through the 1980s, the Philippines have been a source of medical professionals for U.S. medical facilities. The Vietnam War and AIDS epidemic of the 70s and 80s, signaled the need of the American health care system for more foreign trained professionals. In articles published in health/medical policy journals, Filipino nurses comprise the largest block of foreign trained nurses working and entering the United States, from 75% of all foreign nurses in the 1980s to 43% in 2000. Still, Philippine-trained nurses make up 52% of all foreigners taking the U.S. nursing licensure exam, well above the Canadian-trained nurses at 12%.

The significant drop in the percentage of Filipino nurses from the 1980s to 2000 is due to the increase in the number of countries recruiting Filipino nurses (European Union, the Middle East, Japan), as well as the increase in number of countries sending nurses to the United States.[19] According to the United States Census Bureau, 60,000 Filipino nationals migrated to the United States every year in the 1990s to take advantage of such professional opportunities. Other Filipino nationals come to the United States for a college or university education, return to the Philippines and end up migrating to the United States to settle.

American schools have also considered the highly-calibrated Filipino teachers and instructors. More US states have been looking to the Philippines to recruit and fill in the need of their respective schools, particularly North Carolina, Kansas, and Virginia.[20]

Community challenges

Immigration

Filipinos remain one of the largest immigrant group to date with 80,000 people migrating per annum. About 75% consist of family sponsorship or immediate relatives of American citizens while the remainder is employment-oriented. A majority of this number prefer to live in California, followed by Hawaiʻi, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Texas, Washington, Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Colorado, Nevada, Alaska, Maryland and Virginia.

Filipinos experience the same long-waiting periods of visa issuance experienced by immigrants of all other nationalities. The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has a preference system for issuing visas to noncitizen family members of U.S. citizens, with preference based generally on the closeness of familial relation, and some noncitizen relatives of U.S. citizens can spend long periods on immigration waiting lists.[21][22] Petitions for immigrant visas, particularly for siblings of previously naturalized Filipinos that date all the way back to 1984, were granted in 2006.[23][24] Many visa petitions by Filipino Americans for their relatives are on hold or backlogged and as many 1.4 million petitions are affected causing delay to the reunification of Filipino families.

Dual citizenship

As a result of the passage of Philippines Republic Act No. 9225, also known as the Citizenship Retention and Re-Acquisition Act of 2003, Filipino Americans are eligible for dual citizenship in both the United States and the Philippines. Overseas suffrage was first employed in the May 2004 elections in which Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was reelected to a second term.

In 2004, about 6,000 people became dual citizens of the Philippines and the United States. This act encourages many Filipino Americans to invest in the Philippines, buy land (only Filipino citizens and, with some limitations, former Philippine citizens are allowed to purchase land in the Philippines[25][26]), vote in Philippine elections, retire in the Philippines, and participate in representing the Philippine flag.

Many dual citizens have been recruited to participate in international sports events such as the Olympic Games in Athens 2004, the 23rd Southeast Asian Games in Manila, the 15th Asian Games in 2006 and the Olympic Games in Beijing 2008.

In addition, the Philippine government actively encourages Filipino Americans to visit or return permanently to the Philippines via the "Balikbayan" program and to invest in the country. Philippine consulates facilitate this process in various areas of the United States. These are located in Chicago; Honolulu; Los Angeles; New York; Saipan; and San Francisco while honorary consulates are also available in Atlanta, Fort Lauderdale, Houston, Majuro, Miami and New Orleans.

"The Invisible Minority"

The degree of integration and assimilation has gained the Filipino American the label of "Invisible Minority." [27][28] Recent Filipino immigrants assimilate into American culture, as most are fluent in English. The label also extends to the lack of political power and representation.[citation needed] In the mid-1990s, only 100 Filipino Americans held elected office, with all but one serving at the municipal or state level.[citation needed] This is also partly due to the lack, or invisibility of representation, of Filipino American role models in the wider community and media, despite being the second-largest Asian American group in the United States.[citation needed]

Intermarriage among Filipinos with other races is common. They have the largest number of interracial marriages among Asian immigrant groups, as documented in California.[29] It is also noted that 21.8% of Filipino Americans are of mixed blood, second among Asian Americans, and is the fastest growing.[30]

Discrimination

This article possibly contains original research. (January 2009) |

Like most immigrants to the United States, Filipino Americans suffer from racial discrimination for their skin color and the presence or lack of accented English. In the early 20th century, Filipino Americans were in many states barred by anti-miscegenation laws from marrying White Americans, a group which included Hispanic Americans. However despite this, many Filipino men, secretly married or cohabitated with White women in California and the South during the 1920s and 1930s[31][32]. Many were racially segregated into small settlements and were forbidden to travel. The situation became worse after events such as the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair and the Philippine-American War perpetuated many negative stereotypes including the racist idea of the "Little Brown Brother" encapsulated in Rudyard Kipling's The White Man's Burden. President McKinley was reputed to have said that America should "educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them"; the veracity of this famous quote is in dispute, but it fairly reflected the attitudes of McKinley and others in the American government (and perhaps also reflected American ignorance of the predominance of the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines under nearly four hundred years of Spanish colonialism.)[33]

During the turbulent 1960s when American blacks were championing their civil rights on the streets and in the courts, Filipino Americans began benefiting from anti-discrimination laws and an increased sense of national tolerance to racial diversity. Many states either let their anti-miscegenation laws expire or discarded them. Still, for the Filipino Americans living in the states in the latter half of the 20th century, racial discrimination was a daily existence. Often mistaken for Vietnamese during the 1970s, racial epithets invoking Vietnamese were popularly used against Fil-Ams. With the infamous deposing of President Ferdinand Marcos in 1986, the Philippines and Filipino Americans in general came to the forefront of the American consciousness through the popular media. Nearly all of the media images of Filipinos from 1972 through 1986 showed very light-skinned people, from Marcos to his wife, Imelda, to Marcos' successor, President Macapagal-Arroyo. Darker complexioned Fil-Ams were frequently told by American Caucasians that they could not be Filipino, as they were too dark skinned.[citation needed] The darker skinned Filipino Americans were often mistaken by their fellow Americans for Mexicans.

American-born Fil-Ams who spoke fluent English were still viewed as "foreigners" by many Americans. Well-spoken, accent-less Filipino Americans born in the USA were frequently asked about their emigration to the United States (i.e., "So when did you arrive in the states?"), and whether or not they were yet citizens.[citation needed] Conversely, when visiting the Philippines, Fil-Ams not fluent in the native tongues were chided for speaking English and acting "too western."[citation needed]

Second and third-generation Filipino Americans not fluent in their forebears' native tongues also suffer discrimination from more recently arrived first-generation Filipino Americans. The more recent first-generation Fil-Ams, ignorant of the near stultifying racial discrimination faced by earlier waves of Filipino immigrants to the Americas, and equally unaware of the tremendous American cultural imperative through the 1970s to assimilate, i.e., become culturally American, frequently scorn or at best ignore non-Philippine language speaking Fil-Ams.[citation needed] This effectively exacerbates cohesion efforts among different generations of Filipino Americans.

In the 21st century, state-sanctioned racial discrimination against Filipino Americans no longer officially exists. A reflection of America's growing acceptance of racial diversity and the political correctness mindset, overt racial discrimination against people of color, including Filipino Americans, has dissipated to a large extent. Still, among the decidedly non-politically correct crowd, racial strife still exists. Recent race-based hate crimes against Filipino Americans have occurred, the most notably the 1999 murder of Joseph Ileto by white supremacist Aryan Nations member Buford Furrow and the March 16, 2007 assault of young honors student Marie Stefanie Martinez by a group of black teenagers at a New York city bus.[34] [35] [36] On September 13, 2007 Northwestern University student and former Air Force SSgt. Frannie Richards (born and raised in Chicago, Illinois) was allegedly harassed by a sales clerk of H&M store at Downtown Chicago's Magnificent Mile and was called "Mail Order Bride" and uttered "Ching, Ching, Chang" at the female Air Force veteran. [37] [38] [39] [40] There have also been cases of unreasonable deportation and visa rejection against Filipino Americans, and greater scrutiny when re-entering the United States from Mexico and Canada, even for native-born US citizens.[41] [failed verification]

Post 9/11 Issues

After the attacks on 11 September 2001, the United States government led a crackdown on foreign visitors and workers, which included Filipinos who entered the United States illegally, on temporary tourist, education, and work visas but often choose to stay after their visas expire. The United States Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization Service was dissolved and replaced with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services in hopes of more aggressive prevention of visa fraud.

Also, due to the links of terrorism and the Philippine Islamist group Abu Sayyaf, Filipino Americans have been under suspicion as collaborators to extremists.[41]

World War II veteran benefits

During World War II, over 200,000 Filipinos served with the United States Military. The U.S. government promised all of the benefits afforded to those serving in the Military of the United States. However, in 1946, the United States Congress passed the Rescission Act which stripped Filipinos who served during WWII of the benefits as promised. Of the sixty-six countries allied with the United States during the war, the Philippines is the only country that did not receive military benefits from the United States.

Since the passage of the Rescission Act, many Filipino veterans have traveled to the United States to lobby Congress for the benefits promised to them for their service and sacrifice. Over 30,000 of such veterans live in the United States today, with most being American citizens. Sociologists introduced the phrase "Second Class Veterans" to describe the plight of these Filipino Americans. Since 1993, numerous bills were introduced in Congress to return the benefits taken away from these veterans. However, the bills died in committee. The current "full equity" bills are S. 57 in the Senate, and H.R. 760 in the House of Representatives. These two bills also did not pass at the end of the 110th US Congress. Similar language has since been inserted by the Senate into the proposed American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009[42].

Political trends

According to the new statistics, children of Filipino immigrants who were either born or grew up in the country tend to support the Democratic Party, and many also have a liberal persuasion on political issues.[43] During the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election, Filipino Americans voted decidedly Democratic, with 58% of the community voting for Barack Obama and 42% voting for John McCain.[43]

Celebrations

A reflection of their cultural heritage's deep-rooted fondness of hospitality, Filipino Americans are fond to celebrate events, both personal and community-wide. It is not unusual for a family (and extended families) to host perhaps a dozen occasions a year (e.g., baptisms, birthdays, funerals, holidays, showers, weddings). Filipino American cultural traditions often revolve around meals shared in groups, marked by the ubiquitous handcarved, oversized, wooden spoon and fork wall decorations in Fil-Am households. No celebration in Filipino American customs is without a hearty meal (almost to the point of a groaning table), and so celebrations are highlighted by large buffets of traditional Filipino foods including but not limited to adobo (savory soy sauce and vinegar stewed beef, pork or chicken), lumpia (egg rolls), pancit (noodles), lechon (pronounced leh-chon, whole roasted pig featuring a crisped skin and tender, succulent meat), and grilled fish, often bangus (pronounced bawng-oos, a fresh water fish known commonly as "milkfish" characterized by sweet flesh with a large quantity of thin bones).

Filipino American cultural fondness for festivities has led to the establishment of community-wide festivals celebrating the Filipino culture. These usually take the form of fiestas, street fairs, and parades. Most festivals occur in May during Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, which includes Flores de Mayo, a Roman Catholic harvest feast in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Congress has established the Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in May to commemorate Filipino American and Asian American culture in the United States. Upon becoming the largest Asian American group in California, Filipino American History Month was established in October. This is to acknowledge the first landing of Filipinos on October 18, 1587 in Morro Bay, California and is widely celebrated by Fil-Ams in the United States.[44][45]

Several events commemorating the Philippine Declaration of Independence occur mostly in June since it is one of the most important events for the community. An example of these is the Philippine Independence Day Parade in New York City, the largest Filipino celebration in the country.

| Date | Name | Region |

|---|---|---|

| January | Winter Sinulog | Philadelphia, PA |

| April | Easter Salubong | Nationwide, USA |

| April | PhilFest | Tampa, FL |

| May | Asian Pacific American Heritage Month | Nationwide, USA |

| May | Filipino Festival | New Orleans, LA |

| May | Filipino Fiesta and Parade | Honolulu, HI |

| May | Flores de Mayo | Nationwide, USA |

| June | Philippine Independence Day Parade | New York, NY |

| June | Philippine Festival | Washington, D.C. |

| June | Philippine Day Parade | Passaic, NJ |

| June | Pista Sa Nayon | Vallejo, CA |

| June | New York Filipino Film Festival at The ImaginAsian Theatre | New York, NY |

| June | Empire State Building commemorates Philippine Independence[46] | New York, NY |

| June | Philippine-American Friendship Day Parade | Jersey City, NJ |

| June 12 | Fiesta Filipina | San Francisco, CA |

| June 12 | Philippine Independence Day | Nationwide, USA |

| June | Pagdiriwang | Seattle, WA |

| July | Fil-Am Friendship Day | Virginia Beach, VA |

| July | Pista sa Nayon | Seattle, WA |

| July | Philippine Weekend[47] | Delano, CA |

| August | Annual Philippine Fiesta[48] | Secaucus, NJ |

| August | Summer Sinulog | Philadelphia, PA |

| August | Pistahan Fesitval and Parade | San Francisco, CA |

| September 27 | Festival of San Lorenzo Luis | New Orleans, LA |

| September | Festival of Philippine Arts and Culture (FPAC) | Los Angeles, CA |

| October | Filipino American History Month | Nationwide, USA |

| December 16 to 24 | Simbang Gabi Christmas Dawn Masses | Nationwide, USA |

| December 25 | Pasko Christmas Feast | Nationwide, USA |

| December 30 | Jose Rizal Day | Nationwide, USA |

Timeline

- 1573 to 1811, Roughly between 1556 and 1813, Spain engaged in the Galleon Trade between Manila and Acapulco. The galleons were built in the shipyards of Cavite, outside Manila, by Filipino craftsmen. The trade was funded by Chinese traders, manned by Filipino sailors and “supervised” by Spain. In this time frame, Spain recruited Mexicans to serve as soldiers in Manila. Likewise, they drafted Filipinos to serve as soldiers in Mexico. Once drafted, the trip across the ocean usually came with a “one way” ticket.

- 1587, First Filipinos (“Luzonians”) to set foot in North America arrive in Morro Bay, (San Luis Obispo) California on board the Manila-built galleon ship Nuestra Senora de Esperanza under the command of Spanish Captain Pedro de Unamuno.

- 1720, Gaspar Molina, a Filipino from Pampanga province, oversees the construction of El Triunfo dela Cruz, the first ship built in California.

- 1763, First permanent Filipino settlements established in North America near Barataria Bay in southern Louisiana.

- 1781, Antonio Miranda Rodriguez chosen a member of the first group of settlers to establish the City of Los Angeles, California. He and his daughter fell sick with smallpox while enroute, and remained in Baja California for an extended time to recuperate. When they finally arrived in Alta California, it was discovered that Miranda Rodriguez was a skilled gunsmith. He was reassigned in 1782 to the Presidio of Santa Barbara as an armorer.[49]

- 1796, The first American trading ship to reach Manila, the Astrea, was commanded by Captain Henry Prince.

- 1812, During the War of 1812, Filipinos from Manila Village (near New Orleans) were among the "Batarians" who fought against the British under the command of Jean Lafitte in the Battle of New Orleans.[50]

- 1870, Filipinos studying in New Orleans form the first Filipino Association in the United States, the “Sociedad de Beneficencia de los Hispanos Filipinos.”

- 1888, Dr. José Rizal visits the United States and predicts that the Philippines will one day be [a United States] colony in his essay, The Philippines: A Century Hence.[51]

- 1898, The Philippines declares its independence (June 12, Kawit, Cavite) only to be ceded to the United States by Spain for $20 million. United States annexes the Philippines.

- 1899, Philippine-American War begins.

- 1902, Cooper Act passed by the U.S. Congress makes it illegal for Filipinos to own property, vote, operate a business, live in an American residential neighborhood, hold public office and become a naturalized American citizen.

- 1903, First Pensionados, Filipinos invited to attend college in the United States on American government scholarships, arrive.

- 1906, First Filipino laborers migrate to the United States to work on the Hawaiian sugarcane and pineapple plantations, California and Washington asparagus farms, Washington lumber, Alaska salmon canneries. About 200 Filipino “pensionados” are brought to the U.S. to get an American education.

- 1916, The US “recruited” Filipinos for service during World War I. Very few survived and returned to the Philippines.[citation needed].

- 1920s, Filipino labor leaders organize unions and strategic strikes to improve working and living conditions.

- 1924, Filipino Workers’ Union (FLU) shuts down 16 of 25 sugar plantations.

- 1926, California's anti-miscegenation law, Civil Code, section 60, amended to prohibit marriages between white persons and members of the "Malay race" (i.e. Filipinos). (Stats. 1933, p. 561.).

- 1928, Filipino Businessman Pedro Flores opens Flores yo-yos, which is credited with starting the yo-yo craze in the United States. He came up with and copyrighted the word yo-yo.[52] He also applied for and received a trademark for the Flores Yo-yo, which was registered on July 22, 1930.[52] His company went on to be become the foundation of which would latter become the Duncan yo-yo company.[52]

- 1929, Anti-Filipino riots break out in Watsonville and other California rural communities, in part because of Filipino men having intimate relations with White women which was in violation of the California anti-miscegenation laws inacted during that time.[53]

- 1934, The Tydings-McDuffie Act, known as the Philippine Independence Act limited Filipino immigration to the U.S. to 50 persons a year (not to apply to persons coming or seeking to come to the Territory of Hawaii).[54]

- 1936, Philippines becomes self-governing. Commonwealth of the Philippines inaugurated.

- 1939, Washington Supreme Court rules unconstitutional the Anti-Alien Land Law of 1937 which banned Filipino Americans from owning land.[55]

- April 1942, First and Second Filipino Regiments formed in the U.S. composed of Filipino agricultural workers.[56]

- May 1942, After the fall of Bataan and Coregidor to the Japanese, the US Congress passes a law which grants US citizenship to Filipinos and other aliens who served under the U.S. Armed Forces.[citation needed]

- 1946, Philippines becomes independent. Republic of the Philippines inaugurated; America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan published.[57]

- 1948, California Supreme Court rules Califorinia's anti-miscegenation law unconstitutional,[58] ending racially based prohibitions of marriage in the state (although it wasn't until Loving v. Virginia in 1967 that interracial marriages were legalized nationwide). Celestino Alfafara wins California Supreme Court decision allowing aliens the right to own real property.[citation needed]

- 1955, Peter Aduja becomes first Filipino American elected to office, becoming a member of the Hawai'i State House of Representatives.

- 1956, Bobby Balcena becomes first Filipino American to play Major League baseball, playing for the Cincinnati Reds.

- 1965, Congress passes Immigration and Nationality Act which facilitated ease of entry for skilled Filipino laborers.

- 1965, Delano grape strike begins when members of Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, mostly Filipino farm workers in Delano, California walked off the farms of area table grape growers demanding wages on level with the federal minimum wage. Labor leader Philip Vera Cruz subsequently served as second vice president and on the managing board of the United Farm Workers. 1965- Filipino farm workers under the leadership of Larry Itliong go on strike in Delano and win Cesar Chavez joins Itliong to from the United Farm Workers Union. Filipino American Political Association (FAPA) is formed with chapters in 30 California cities. Immigration Act of 1965 raises quota of Eastern Hemisphere countries, including the Philippines, to 20,000 a year.

- 1967, The Philippine American Collegiate Endeavor (PACE) founded by Filipino American students at San Francisco State College.[59]

- 1969, Pilipino American Alliance (PAA) founded by Filipino American students at University of California, Berkeley; reorganized in 1995 as the Pilipino Academic Student Services (PASS).[60]

- 1974, Benjamin Menor appointed first Filipino American in a state's highest judiciary office as Justice of the Hawaiʻi State Supreme Court.

- 1975, Governor John A. Burns (D-HI) convinces Benjamin J. Cayetano to run and win a seat in the Hawaiʻi State Legislature, despite Cayetano's doubts about winning office in a white and Japanese American dominated district; Kauai's Eduardo E. Malapit elected first Filipino American mayor.

- 1981, Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes are both assassinated June 1, 1981 inside a Seattle downtown union hall.[61]

The late Philippine Dictator Ferdinand Marcos hired gunmen to murder both ILWU Local 37 officers to silence the growing movement in the United States opposing the dictatorship in the Philippines.[citation needed]

- 1987, Benjamin J. Cayetano becomes the first Filipino American and second Asian American elected Lt. Governor of a state of the Union.

- 1990, David Mercado Valderrama becomes first Filipino American elected to a state legislature on the mainland United States serving Prince George's County in Maryland. Immigration reform Act of 1990 is passed by the U.S. Congress granting U.S. citizenship to Filipino WWII veterans resulting in 20,000 Filipino veterans take oath of citizenship.

- 1991, Seattle's Gene Canque Liddell becomes first Filipino American woman to be elected mayor serving the suburb of Lacey City.

- 1992, Velma Veloria becomes first Filipino American and first Asian American elected to the Washington State Legislature.

- 1993, Mario R. Ramil appointed Associate Justice to the Hawai'i Supreme Court, the second Filipino American to reach the court.

- 1994, Benjamin J. Cayetano becomes the first Filipino American and second Asian American elected Governor of a state of the Union.

- 1999, US Postal worker Joseph Ileto murdered in a hate crime by Aryan Nations member Buford Furrow.

- 2000, Robert Bunda elected Hawai'i Senate President and Simeon R. Acoba, Jr. appointed Hawai'i State Supreme Court Justice.

- 2003, Philippine Republic Act No. 9225, also known as the Citizenship Retention and Re-Acquisition Act of 2003 enacted, allowing natural-born Filipinos naturalized in the United States and their unmarried minor children to reclaim Filipino nationality and hold dual citizenship.[62][63]

- 2006, Congress passes legislation that commemorates the 100 Years of Filipino Migration to the United States.[64]

- 2006, First monument dedicated to Filipino soldiers who fought for the United States in World War II unveiled in Historic Filipinotown, Los Angeles, California.[65]

Notable people

Further reading

- Carl L. Bankston III, "Filipino Americans," in Pyong Gap Min (ed.), Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues ISBN 1-4129-0556-7

- Bautista, Veltisezar. The Filipino Americans from 1763 to the Present: Their History, Culture, and Traditions , ISBN 0-931613-17-5

- Crisostomom Isabelo T. Filipino Achievers in the U.S.A. & Canada: Profiles in Excellence, ISBN 0-931613-11-6

- Isaac, Allan Punzalan. American Tropics: Articulating Filipino America, (University of Minnesota Press; 205 pages; 2007) Analyzes images of the Philippines in Hollywood cinema, Boy Scout adventure novels, Progressive Era literature, and other realms

- A. Tiongson, E. Gutierrez, R. Gutierrez, eds. Positively No Filipinos Allowed, ISBN 1-59213-122-0

- Filipino American Lives by Yen Le Espiritu, ISBN 1-56639-317-5

- Filipinos in Chicago (Images of America) by Estrella Ravelo Alamar, Willi Red Buhay ISBN 0-7385-1880-8

- "The Filipinos in America: Macro/Micro Dimensions of Immigration and Integration" by Antonio J. A. Pido ISBN 0913256838

News

- "Filipino Population in U.S. rivals Chinese-Americans", Honolulu Advertiser, 18 November 1996, Gannett News Service

See also

References

- ^ a b The U.S. Census Bureau 2007 American Community Survey counted 2,445,126 Filipino-Americans, 3,053,179 Filipinos, 608,053 of whom were not U.S. citizens: "Selected Population Profile in the United States: Filipino alone or in any combination". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ^ a b "Background Note: Philippines". U.S. Department of State: Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

There are an estimated four million Americans of Philippine ancestry in the United States, and more than 250,000 American citizens in the Philippines.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: May 2007" (Press release). U.S. Census Bureau. March 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-03. (based on census 2000 data)

- ^ Rene Villaroman (July 10, 2007), LA Consul General Throws Ceremonial First Pitch at Dodgers-Padres Pre-Game Event, Asian Journal Online

See also: About the Consulate General, The Philippine Consulate General of Los Angeles, California, retrieved 2008-06-02 - ^ Aurora S. Cudal, A BRIEF HISTORY OF COPAO, COUNCIL OF PHILIPPINE AMERICAN ORGANIZATIONS OF SAN DIEGO COUNTY, INC., retrieved 2008-06-02

- ^ Joseph Berger (January 27, 2008), Filipino Nurses, Healers in Trouble, The New York Times, retrieved 2008-06-02

- ^ Filipino-American Population, ABS-CBN News, retrieved 2008-12-16

- ^ "Statistical Abstract of the United States: page 47: Table 47: Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chapel of San Lorenzo Ruiz". Retrieved 2007-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|publishet=ignored (help) - ^ "Speaking Truth to Power!!". Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "U.S. economics" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "economics" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Census Profile: New York City's Filipino American Population (pdf), Asian American Federation of New York, retrieved 2007-12-23

- ^ a b c The American Community-Asians: 2004 (PDF), U.S. Census Bureau, 2007, retrieved 2007-09-05

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Overseas Filipino Remittances". Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ a b "Filipino-Owned Firms 2002". Retrieved 2006-12-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Top 20 Countries Where IMGs Received Medical Training, American Medical Association, retrieved 2007-12-23

{{citation}}: Text "date\August 9, 2007" ignored (help) - ^ "Foreign-trained dentists licensed in the United States: Exploring their origins", American Dental Association

- ^ Brush, et al. "Imported Care: Recruiting Foreign Nurses To U.S. Health Care Facilities", Health Affairs, 2004. vol.23 (3)

- ^ "More US States hire teachers from the Philippines". Retrieved 2007-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ The Preference System, foreignborn.com, retrieved 2008-05-23

- ^ Immigration Preferences and Waiting Lists, lawcom.com, retrieved 2008-05-22

- ^ Immigration Updates, gurfinkel.com, May 28, 2008, retrieved 2008-05-23

- ^ "Green-card limbo". Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ BATAS PAMBANSA BILANG. 185, Chanrobles Law Library, March 16, 1982, retrieved 2008-06-02 (Section 2)

- ^ REPUBLIC ACT NO. 8179, Supreme Court of the Philippines, March 28, 1996, retrieved 2008-06-02 (Section 5)

- ^ Haya El Nasser, Study: Some immigrants assimilate faster, USA Today, retrieved 2008-05-23

- ^ N.C. Aizenman (May 13, 2008), Study Says Foreigners In U.S. Adapt Quickly, The Washington post, retrieved 2008-05-23

- ^ "Interracial Dating & Marriage". asian-nation.org. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "Multiracial / Hapa Asian Americans". asian-nation.org. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ Veltisezar Bautista (2002). "The Filipino Americans: Yesterday and Today". filipinoamericans.net. Retrieved 2007-08-30. (part 1of 2)

- ^ H. Brett Melendy. "Filipino Americans". everyculture.com. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ Lewis L. Gould, The Presidency of William McKinley (Kansas UP, 1980), pp. 140-42.

- ^ Dan Mangan and Leela de Kretser (March 18, 2007). "Girl's Bloody Beating: Driver does nothing as teens attack her on bus". Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ Erika Martinez (2007-03-14). "Girl, 14, nabbed in student bus beating" (html). New York Post. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Caroline Aoyagi-Stom (2007-04-06). "AA Community Rallies Around 17-Year-Old Teen Beaten on New York MTA Bus" (html). Pacific Citizen. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mary Owen (2007-10-06). "Protest at H & M backs claim of harassment". Local news. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ "Filipino American Harassed by H&M Employee" (html). blog. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ Sean Walsh (2007-10-08). "Demonstrators protest alleged slur at H&M". article. The Daily Northwestern. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ "Youtube Videos of Frannie Richards interview". AAI In the News. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ a b Jeffrey M. Bale (2003). "The Abu Sayyaf Group in its Philippine and International Contexts: A Profile and WMD Threat Assessment" (pdf). onterey Institute of International Studies. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Maze, Rick (2008-01-29). "Senate puts Filipino vet pensions in stimulus" (News Article). Army Times. Army Times Publishing Company. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

Buried inside the Senate bill, which includes tax cuts and new spending initiatives intended to create jobs in the U.S., the Filipino payment was inserted at the urging of Sen. Daniel Inouye, D-Hawaii, the new chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee and a longtime supporter of monthly pensions for World War II Filipino veterans.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|curly=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Gus Mercado

Publisher=Philippine Daily Inquirer (November 10, 2008), Obama wins Filipino vote at last-hour, retrieved 2008-12-16

{{citation}}: line feed character in|author=at position 12 (help) - ^ "Sulat sa Tanso". Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "history". Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Empire State lights up for Filipinos—again". Archived from the original on 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2006-10-18 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Filipino weekend". Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Philippine Fiesta". Retrieved 2006-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Original Settlers (Pobladores) of El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles, 1781, laalmanac.com, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ Nancy Dingler (June 23, 2007), Filipinos made immense contributions in Vallejo, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ José Rizal, The Philippines a Century Hence, joserizal.info, retrieved 2008-01-17 (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire, first published in La Solidaridad, Madrid, between September 30, 1889, and February 1, 1890)

"... Perhaps the great American Republic, whose interests lie in the Pacific and who has no hand in the spoliation of Africa, may dream some day of foreign possession. This is not impossible, for the example is contagious, covetousness and ambition are among the strongest vices, and Harrison manifested something of this sort in the Samoan question. ..." - ^ a b c Lucky Meisenheimer, MD, Pedro Flores, nationalyoyo.org, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ Remembering the Watsonville Riots, modelminority.com, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ The Philippine Independence Act (Tydings-McDuffie Act), Chanrobles Law Library, March 24, 1934, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ Filipino Americans, Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ California's Filipino Infantry, The California State Military Museum, retrieved 2008-01-24

- ^ TREATY OF GENERAL RELATIONS BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES. SIGNED AT MANILA, ON 4 JULY 1946 (pdf), United Nations, retrieved 2007-12-10

- ^ Perez vs. Sharp - End to Miscegenation Laws in California, Los Angeles Almanac, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ Philippine American Collegiate Endeavor, retrieved 2007-12-27

- ^ http://pass.berkeley.edu/history.htm

- ^ Filipino labor activists Gene Viernes and Silme Domingo are slain in Seattle on June 1, 1981, historylink.org

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|accreedate=ignored (help) - ^ "Citizenship Retention and Re-acquisition Act of 2003". Philippine Government, Bureau of Immigration. 2003-08-29. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Implementing Rules and Regulations for R.A. 9225". Philippine Government, Bureau of Immigration. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "109th Congress, H.CON.RES.218, Recognizing the centennial of sustained immigration from the Philippines to the United States ..." U.S. Library of Congress. 2005-12-15. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ GARCETTI UNVEILS NATION’S FIRST FILIPINO VETERANS MEMORIAL, Eric Garcetti, President, los Angeles city council, November 13, 2006

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Text "url\http://www.ci.la.ca.us/council/cd13/cd13press/cd13cd13press13242318_11132006.pdf" ignored (help)

External links

- Filipino American Community Builder news and articles relevant to the Filipino American community

- BakitWhy - Filipino American Lifestyle

- Filipino American Library

- Americans of Filipino Descent - FAQs

- Filipino American Centennial Commemoration from Smithsonian

- Famous Kababayans

- The Brown Raise Movement The Brown Raise Movement - a movement towards the 21st Century Global Filipino

- Filipino Recipes

Asian Pacific American Program

- Fil Am Arts

- "City of Los Angeles declares Historic Filipinotown".

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help) - Did Philippine indios really land in Morro Bay? by Hector Santos

- Manilamen: The Filipino Roots in America

- Filipino Founding Father of Los Angeles

- The Manila Galleon Trade, 1565-1815 see also Manila Galleon trade[1]

- Chronology of Filipinos in America Pre-1898

- Filipino Veterans of War of 1812 and American Civil War

- TheFilipino.com Most extensive list of Filipino organizations in the US

- History of Filipino Americans in Seattle

- History of Filipino Americans in Chicago

- iFili.com All Filipino News, Views & Videos

- Filipino American Organizations Directory in Asians in America Magazine

- PugadPinoy.com Overseas Filipino Directory Listings

- Census 2000 Brief: The Asian Population: 2000