Indo-Greek Kingdom: Difference between revisions

Pmanderson (talk | contribs) replace citation of McEvilley with his source, which says something different. |

Pmanderson (talk | contribs) Replace with Narain's actual opinion, and reduce weight to McEvilley as tertiary source. |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

The '''Indo-Greek Kingdom''' (or sometimes '''Graeco-Indian Kingdom'''<ref>As in other compounds such as "Franco-Canadian", "African-American" , "Indo-European" etc..., the area of origin usually comes first, and the area of arrival comes second, so that "Greco-Indian" is normally a more accurate nomenclature than "Indo-Greek". The latter however has become the general usage, especially since the publication of Narain's book "The Indo-Greeks".</ref>) covered various parts of the northwest and northern [[Indian subcontinent]] from 180 BCE to around 10 CE, and was ruled by a succession of more than thirty [[Hellenic]] and [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic]] <!--what is "Hellenic and Hellenistic" supposed to mean, anyway?--> kings,<ref>[[Euthydemus I]] was, according to Polybius[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34 11.34], a [[Magnesia]]n [[Greek people|Greek]]. His son, [[Demetrius I of Bactria|Demetrius I]], founder of the Indo-Greek kingdom, was therefore of Greek ethnicity at least by his father. Demetrius also married a daughter of the [[Seleucid Empire|Seleucid]] ruler [[Antiochus III]] (who had some [[Persian people|Persian]] descent) according to the same Polybius {{Failed verification|date=October 2007}}<!--promised is not given-->[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34 11.34]. The ethnicity of later Indo-Greek rulers is less clear ([http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0075-4269(1902)22%3C268%3ANOHIBA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-J "Notes on Hellenism in Bactria and India".] W. W. Tarn. ''Journal of Hellenic Studies'', Vol. 22 (1902), pages 268–293). For example, [[Artemidoros]] (80 BCE) may have been of [[Indo-Scythian]] ascendency. Some level of inter-marriage may also have occurred, as exemplified by [[Alexander the Great|Alexander III]] [[Macedon|of Macedon]] (who married [[Roxana]] [[Bactria|of Bactria]]) or [[Seleucus I Nicator|Seleucus]] (who married [[Apama]]).</ref> often in conflict with each other. The kingdom was founded when the [[Greco-Bactrian]] king [[Demetrius I of Bactria|Demetrius]] invaded India in 180 BCE, ultimately creating an entity which seceded from the powerful [[Greco-Bactrian Kingdom]] centered in Bactria (today's northern [[Afghanistan]]). Since the term "Indo-Greek Kingdom" loosely describes a number of various dynastic polities, it had numerous cities, such as [[Taxila]]<ref>Mortimer Wheeler ''Flames over Persepolis'' (London, 1968). Pp. 112 ''ff.'' It is unclear whether the Hellenistic street plan found by Sir John Marshall's excavations dates from the Indo-Greeks or from the Kushans, who would have encountered it in Bactria; Tarn (1951, pp. 137, 179) ascribes the initial move of Taxila to the hill of Sirkap to Demetrius I, but sees this as "not a Greek city but an Indian one"; not a ''polis'' or with a Hippodamian plan. </ref> in the easternmost part of the Pakistani [[Punjab]], or [[Pushkalavati]] and [[Sagala]].<ref>"Sagala |

The '''Indo-Greek Kingdom''' (or sometimes '''Graeco-Indian Kingdom'''<ref>As in other compounds such as "Franco-Canadian", "African-American" , "Indo-European" etc..., the area of origin usually comes first, and the area of arrival comes second, so that "Greco-Indian" is normally a more accurate nomenclature than "Indo-Greek". The latter however has become the general usage, especially since the publication of Narain's book "The Indo-Greeks".</ref>) covered various parts of the northwest and northern [[Indian subcontinent]] from 180 BCE to around 10 CE, and was ruled by a succession of more than thirty [[Hellenic]] and [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic]] <!--what is "Hellenic and Hellenistic" supposed to mean, anyway?--> kings,<ref>[[Euthydemus I]] was, according to Polybius[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34 11.34], a [[Magnesia]]n [[Greek people|Greek]]. His son, [[Demetrius I of Bactria|Demetrius I]], founder of the Indo-Greek kingdom, was therefore of Greek ethnicity at least by his father. Demetrius also married a daughter of the [[Seleucid Empire|Seleucid]] ruler [[Antiochus III]] (who had some [[Persian people|Persian]] descent) according to the same Polybius {{Failed verification|date=October 2007}}<!--promised is not given-->[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34 11.34]. The ethnicity of later Indo-Greek rulers is less clear ([http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0075-4269(1902)22%3C268%3ANOHIBA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-J "Notes on Hellenism in Bactria and India".] W. W. Tarn. ''Journal of Hellenic Studies'', Vol. 22 (1902), pages 268–293). For example, [[Artemidoros]] (80 BCE) may have been of [[Indo-Scythian]] ascendency. Some level of inter-marriage may also have occurred, as exemplified by [[Alexander the Great|Alexander III]] [[Macedon|of Macedon]] (who married [[Roxana]] [[Bactria|of Bactria]]) or [[Seleucus I Nicator|Seleucus]] (who married [[Apama]]).</ref> often in conflict with each other. The kingdom was founded when the [[Greco-Bactrian]] king [[Demetrius I of Bactria|Demetrius]] invaded India in 180 BCE, ultimately creating an entity which seceded from the powerful [[Greco-Bactrian Kingdom]] centered in Bactria (today's northern [[Afghanistan]]). Since the term "Indo-Greek Kingdom" loosely describes a number of various dynastic polities, it had numerous cities, such as [[Taxila]]<ref>Mortimer Wheeler ''Flames over Persepolis'' (London, 1968). Pp. 112 ''ff.'' It is unclear whether the Hellenistic street plan found by Sir John Marshall's excavations dates from the Indo-Greeks or from the Kushans, who would have encountered it in Bactria; Tarn (1951, pp. 137, 179) ascribes the initial move of Taxila to the hill of Sirkap to Demetrius I, but sees this as "not a Greek city but an Indian one"; not a ''polis'' or with a Hippodamian plan. </ref> in the easternmost part of the Pakistani [[Punjab]], or [[Pushkalavati]] and [[Sagala]].<ref>"Even if Sagala proves to be Sialkot, it does not seem to be Menander's capital"; Menander came down to Sagala to meet Nagasena, "as the Ganges flows to the sea." Narain "The Indo-Greeks",(1957, p.81) p.237 McEvilley supports Tarn on both points, citing Woodcock. </ref> These cities would house a number of dynasties in their times, and based on [[Ptolemy]]'s ''[[Geographia (Ptolemy)|Geographia]]'' and the nomenclature of later kings, a certain Theophila in the south was also probably a satrapal or royal seat at some point. |

||

During the two centuries of their rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined the Greek and Indian languages and symbols, as seen on their coins, and blended [[ancient Greek]], [[Hindu]] and [[Buddhist]] religious practices, as seen in the archaeological remains of their cities and in the indications of their support of Buddhism. The Indo-Greek kings seem to have achieved a very high level of cultural [[syncretism]], the consequences of which are still felt today, particularly through the diffusion and influence of [[Greco-Buddhist art]]. |

During the two centuries of their rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined the Greek and Indian languages and symbols, as seen on their coins, and blended [[ancient Greek]], [[Hindu]] and [[Buddhist]] religious practices, as seen in the archaeological remains of their cities and in the indications of their support of Buddhism. The Indo-Greek kings seem to have achieved a very high level of cultural [[syncretism]], the consequences of which are still felt today, particularly through the diffusion and influence of [[Greco-Buddhist art]]. |

||

Revision as of 01:21, 19 October 2007

Territories and expansion of the Indo-Greeks.[1] | |

| Languages | Greek (Greek alphabet) Pali (Kharoshthi script) Sanskrit, Prakrit (Brahmi script) Possibly Aramaic |

|---|---|

| Religions | Buddhism Ancient Greek religion Hinduism Zoroastrianism |

| Capitals | Alexandria in the Caucasus Sirkap/Taxila Sagala/Sialkot Pushkalavati/Peucela |

| Area | Northwestern Indian subcontinent |

| Existed | 180 BCE–10 CE |

The Indo-Greek Kingdom (or sometimes Graeco-Indian Kingdom[2]) covered various parts of the northwest and northern Indian subcontinent from 180 BCE to around 10 CE, and was ruled by a succession of more than thirty Hellenic and Hellenistic kings,[3] often in conflict with each other. The kingdom was founded when the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius invaded India in 180 BCE, ultimately creating an entity which seceded from the powerful Greco-Bactrian Kingdom centered in Bactria (today's northern Afghanistan). Since the term "Indo-Greek Kingdom" loosely describes a number of various dynastic polities, it had numerous cities, such as Taxila[4] in the easternmost part of the Pakistani Punjab, or Pushkalavati and Sagala.[5] These cities would house a number of dynasties in their times, and based on Ptolemy's Geographia and the nomenclature of later kings, a certain Theophila in the south was also probably a satrapal or royal seat at some point.

During the two centuries of their rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined the Greek and Indian languages and symbols, as seen on their coins, and blended ancient Greek, Hindu and Buddhist religious practices, as seen in the archaeological remains of their cities and in the indications of their support of Buddhism. The Indo-Greek kings seem to have achieved a very high level of cultural syncretism, the consequences of which are still felt today, particularly through the diffusion and influence of Greco-Buddhist art.

The Indo-Greeks ultimately disappeared as a political entity around 10 CE following the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, although pockets of Greek populations probably remained for several centuries longer under the subsequent rule of the Indo-Parthians and Kushans.

Background

Preliminary Greek presence in India

In 326 BC Alexander III conquered the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent as far as the Hyphasis River, and established satrapies as well as several cities, such as Bucephala, until his troops refused to go further east. The Indian satrapies of the Punjab were left to the rule of Porus and Taxiles, who were confirmed again at the Treaty of Triparadisus in 321, and remaining Greek troops in these satrapies were left under the command of general Eudemus. Sometime after 321 Eudemus toppled Taxiles, until he left India in 316 BCE. Another general also ruled over the Greek colonies of the Indus: Peithon, son of Agenor,[6] until his departure for Babylon in 316 BCE, and a last one, Sophytes, may have ruled in northern Punjab until around 294 BCE.

According to Indian sources, Greek ("Yavana") troops seem to have assisted Chandragupta Maurya in toppling the Nanda Dynasty and founding the Mauryan Empire.[7] By around 312 BCE Chandragupta had established his rule in large parts of the northwestern Indian territories.

In 303 BCE, Seleucus I led an army to the Indus, where he encountered Chandragupta. The confrontation ended with a peace treaty, and "an intermarriage agreement" (Epigamia, Greek: Επιγαμια), meaning either a dynastic marriage or an agreement for intermarriage between Indians and Greeks. Accordingly, Seleucus ceded to Chandragupta his northwestern territories, possibly as far as Arachosia and received 500 war elephants (which played a key role in the victory of Seleucus at the Battle of Ipsus):

"The Indians occupy [in part] some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus in consequence of a marriage contract, and received in return five hundred elephants."

Also several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes followed by Deimachus and Dionysius, were sent to reside at the Mauryan court. Presents continued to be exchanged between the two rulers.[9]

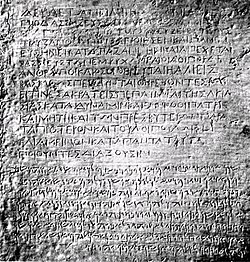

On these occasions, Greek populations apparently remained in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Mauryan rule. Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka, who had converted to the Buddhist faith declared in the Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, that Greek populations within his realm also had converted to Buddhism:

"Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma."

— Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika).

In his edicts, Ashoka claims he sent Buddhist emissaries to Greek rulers as far as the Mediterranean (Edict No13), and that he developed herbal medicine in their territories, for the welfare of humans and animals (Edict No2).

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek ("Yona") Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism (the Mahavamsa, XII[10]). It is also thought that Greeks contributed to the sculptural work of the Pillars of Ashoka,[11] and more generally to the blossomming of Mauryan art.[12]

Again in 206 BCE, the Seleucid emperor Antiochus led an army into India, where he received war elephants and presents from the king Sophagasenus:

"He (Antiochus) crossed the Caucasus (Hindu Kush) and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king had agreed to hand over to him."

Greek rule in Bactria

Alexander also had established in neighbouring Bactria several cities (Ai-Khanoum, Begram) and an administration that were to last more than two centuries under the Seleucids and the Greco-Bactrians, all the time in direct contact with Indian territory.

The Greco-Bactrians maintained a strong Hellenistic culture at the door of India during the rule of the Mauryan empire in India, as exemplified by the archaeological site of Ai-Khanoum. When the Mauryan empire was toppled by the Sungas around 185 BCE, the Greco-Bactrians expanded into India, where they established the Indo-Greek kingdom.

Rise of the Sungas (185 BCE)

In India, the Maurya Dynasty was overthrown around 185 BCE when Pusyamitra Sunga, the commander-in-chief of Mauryan Imperial forces and a Brahmin, assassinated the last of the Mauryan emperors Brhadrata.[14] Pusyamitra Sunga then ascended the throne and established the Sunga Empire, which extended its control as far west as the Punjab.

Buddhist sources, such as the Asokavadana, mention that Pusyamitra was hostile towards Buddhists and allegedly persecuted the Buddhist faith. A large number of Buddhist monasteries (viharas) were allegedly converted to Hindu temples, in such places as Nalanda, Bodhgaya, Sarnath or Mathura. While it is established by secular sources that Hinduism and Buddhism were in competition during this time, with the Sungas preferring the former to the latter, historians such as Etienne Lamotte[15] and Romila Thapar[16] argue that Buddhist accounts of persecution of Buddhists by Sungas are largely exaggerated.

History of the Indo-Greek kingdom

The invasion of northern India, and the establishment of what would be known as the "Indo-Greek kingdom", started around 180 BCE when Demetrius, son of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I, led his troops across the Hindu Kush.[17][18][19] In the process of the invasion, the Greeks seem to have advanced as far as the capital Pataliputra, a feat often attributed to Menander,[20] before ultimately retreating and consolidating in northwestern India.[21][22] Apollodotus, seemingly a relative of Demetrius, led the invasion to the south, while Menander, one of the generals of Demetrius, led the invasion to the east.[23][24] Following his conquests, Demetrius assumed the title ανικητος ("Anicetus", lit. invincible), a title never assumed to any king before.[25][26]

Written evidence of the initial Greek invasion survives in the writings of Strabo and Justin, and in Sanskrit in the records of Patanjali, Kālidāsa, and in the Yuga Purana, among others. Coins and architectural evidence also attest to the extent of the initial Greek campaign.

Evidence of the initial invasion

Greco-Roman sources

The Greco-Bactrians went over the Hindu Kush and first started to re-occupy the area of Arachosia, where Greek populations had been living since before the acquisition of the territory by Chandragupta from Seleucus. Isidore of Charax describes Greek cities there, one of them called Demetrias, probably in honour of the conqueror Demetrius.[27]

According to Strabo, Greek advances temporarily went as far as the Sunga capital Pataliputra (today Patna) in eastern India:

"Of the eastern parts of India, then, there have become known to us all those parts which lie this side of the Hypanis, and also any parts beyond the Hypanis of which an account has been added by those who, after Alexander, advanced beyond the Hypanis, to the Ganges and Pataliputra."

Greek and Indian sources tend to indicate that the Greeks campaigned as far as Pataliputra until they were forced to retreat following the coup staged by Eucratides back in Bactria circa 170 BCE, suggesting an occupation period of about eight years.[29] Alternatively, Menander may merely have joined a raid led by Indian Kings down the Ganga (A.K. Narain and Keay 2000), as Indo-Greek territory has only been confirmed from the Kabul Valley to the Punjab.

To the south, the Greeks occupied the areas of the Sindh and Gujarat down to the region of Surat (Greek: Saraostus) near Mumbai (Bombay), including the strategic harbour of Barigaza (Bharuch),[30], conquests also attested by several writers (Strabo 11; Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Chap. 41/47) and as evidenced by coins dating from the Indo-Greek ruler Apollodotus I:

"The Greeks... took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis."

— Strabo 11.11.1[31]

In Central India, the area of Malwa may also have been conquered.[32]

Indian sources

Various Indian records describe Yavana attacks on Mathura, Panchala, Saketa, and Pataliputra. The term Yavana is thought to be a transliteration of "Ionians" and is known to have designated Hellenistic Greeks (starting with the Edicts of Ashoka, where Ashoka writes about "the Yavana king Antiochus"), but may have sometimes referred to other foreigners as well, especially in later centuries.

Patanjali, a grammarian and commentator on Panini around 150 BCE, describes in the Mahābhāsya,[33] the invasion in two examples using the imperfect tense of Sanskrit, denoting a recent event:

- "Arunad Yavanah Sāketam" ("The Yavanas (Greeks) were besieging Saketa")

- "Arunad Yavano Madhyamikām" ("The Yavanas were besieging Madhyamika" (the "Middle country")).

Also the Brahmanical text of the Yuga Purana, which describes Indian historical events in the form of a prophecy,[34] relates the attack of the Indo-Greeks on the capital Pataliputra, a magnificent fortified city with 570 towers and 64 gates according to Megasthenes,[35] and describes the ultimate destruction of the city's walls:

"Then, after having approached Saketa together with the Panchalas and the Mathuras, the Yavanas, valiant in battle, will reach Kusumadhvaja ("The town of the flower-standard", Pataliputra). Then, once Puspapura (another name of Pataliputra) has been reached and its celebrated mud[-walls] cast down, all the realm will be in disorder."

— Yuga Purana, Paragraph 47–48, 2002 edition.

Epigraphic remains

Several depictions of Greeks in Central India dated to the 2nd-1st century BCE are known, such as the Greek soldier in Bharhut, or a frieze in Sanchi which describes Greek-looking foreigners honouring the Sanchi stupa with gifts, prayers and music (image above). They wear the chlamys cape over short chiton tunics without trousers, and have high-laced sandals. They are beardless with short curly hair and headbands, and two men wear the conical pilos hat. They play various instruments, including two carnyxes, and one aulos double-flute.[36] This is near Vidisa, where an Indo-Greek monument, the Heliodorus pillar, is known.

Consolidation

Retreat from eastern regions

The first invasion was completed by 175 BCE, as the Indo-Greeks apparently contained the Sungas to the area eastward of Pataliputra, and established their rule on the new territory. Back in Bactria however, around 170 BCE, an usurper named Eucratides managed to topple the Euthydemid dynasty.[37] He took for himself the title of king and started a civil war by invading the Indo-Greek territory, forcing the Indo-Greeks to abandon their easternmost possessions and establish their new oriental frontier at Mathura, to confront this new threat:[38]

"The Yavanas, infatuated by war, will not remain in Madhadesa (the Middle Country). There will be mutual agreement among them to leave, due to a terrible and very dreadful war having broken out in their own realm."

— Yuga Purana, paragraphs 56–57, 2002 edition.

In any case, Eucratides seems to have occupied territory as far as the Indus, between ca 170 BCE and 150 BCE.[39] His advances were ultimately checked by the Indo-Greek king Menander I, previously a general of Demetrius, who asserted himself in the Indian part of the empire, apparently conquered Bactria as indicated by his issue of coins in the Greco-Bactrian style, and even began the last expansions eastwards.

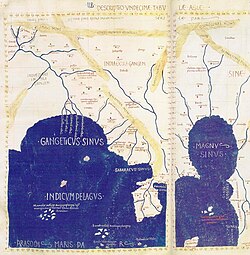

Consolidation and rise of Menander I

Menander is considered as probably the most successful Indo-Greek king, and the conqueror of the vastest territory.[40] The finds of his coins are the most numerous and the most widespread of all the Indo-Greek kings. In Antiquity, from at least the 1st century CE, the "Menander Mons",[citation needed] or "Mountains of Menander", came to designate the mountain chain at the extreme east of the Indian subcontinent, today's Naga hills and Arakan, as indicated in the Ptolemy world map of the 1st century CE geographer Ptolemy. Menander is also remembered in Buddhist literature, where he called Milinda, and is described in the Milinda Panha as a convert to Buddhism: he became an arhat whose relics were enshrined in a manner reminiscent of the Buddha. He also introduced a new coin type, with Athena Alkidemos ("Protector of the people") on the reverse, which was adopted by most of his successors in the East.[41]

Conquests east of the Punjab region were most likely made during the second half of the century by the king Menander I.

Following Menander's reign, about twenty Indo-Greek kings are known to have ruled in succession in the eastern parts of the Indo-Greek territory. Upon his death, Menander was succeeded by his queen Agathokleia, who for some time acted as regent to their son Strato I.[42]

Greco-Bactrian encroachments

From 130 BCE, the Scythians and then the Yuezhi, following a long migration from the border of China, started to invade Bactria from the north.[43] Around 125 BCE the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, son of Eucratides, was probably killed during the invasion and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom proper ceased to exist.[44] Heliocles may have been survived by his relative Eucratides II, who ruled south of the Hindu Kush, in areas untouched by the invasion. Other Indo-Greek kings like Zoilos I, Lysias and Antialcidas may possible have been relatives of either the Eucratid or the Euthydemid dynasties; they struck both Greek and bilingual coins and established a kingdom of their own.

A stabilizing alliance with the Yuezhi then seems to have followed, as hinted on the coins of Zoilos I, who minted coins showing Heracles' club together with a steppe-type recurve bow inside a victory wreath.

The Indo-Greeks thus suffered encroachments by the Greco-Bactrians in their western territories. The Indo-Greek territory was divided into two realms: the house of Menander retreated to their territories east of the Jhelum River as far as Mathura, whereas the Western kings ruled a larger kingdom of Paropamisadae, western Punjab and Arachosia to the south.

Later History

Throughout the 1st century BCE, the Indo-Greeks progressively lost ground to the Indians in the east, and the Scythians, the Yuezhi, and the Parthians in the West. About 19 Indo-Greek king are known during this period, down to the last known Indo-Greek king Strato II, who ruled in the Punjab region until around 10 CE.

Loss of Mathura and eastern territories (circa 100 BCE)

The Indo-Greeks may have ruled as far as the area of Mathura until sometime in the 1st century BCE: the Maghera inscription, from a village near Mathura, records the dedication of a well "in the one hundred and sixteenth year of the reign of the Yavanas", which could be as late as 70 BCE.[45] Soon however Indian kings recovered the area of Mathura and south-eastern Punjab, west of the Yamuna River, and started to mint their own coins. The Arjunayanas (area of Mathura) and Yaudheyas mention military victories on their coins ("Victory of the Arjunayanas", "Victory of the Yaudheyas"). During the 1st century BCE, the Trigartas, Audumbaras and finally the Kunindas (closest to Punjab) also started to mint their own coins, usually in a style highly reminiscent of Indo-Greek coinage.

The Western king Philoxenus briefly occupied the whole remaining Greek territory from the Paropamisadae to Western Punjab between 100 to 95 BCE, after what the territories fragmented again. The western kings regained their territory as far west as Arachosia, and eastern kings continued to rule on and off until the beginning of our era.

Scythian invasions (80 BCE-20 CE)

Around 80 BCE, an Indo-Scythian king named Maues, possibly a general in the service of the Indo-Greeks, ruled for a few years in northwestern India before the Indo-Greeks again took control. King Hippostratos (65-55 BCE) seems to have been one of the most successful subsequent Indo-Greek kings until he lost to the Indo-Scythian Azes I, who established an Indo-Scythian dynasty.

Although the Indo-Scythians clearly ruled militarily and politically, they remained surprisingly respectful of Greek and Indian cultures. Their coins were minted in Greek mints, continued using proper Greek and Kharoshthi legends, and incorporated depictions of Greek deities, particularly Zeus. The Mathura lion capital inscription attests that they adopted the Buddhist faith, as do the depictions of deities forming the vitarka mudra on their coins. Greek communities, far from being exterminated, probably persisted under Indo-Scythian rule. There is a possibility that a fusion, rather than a confrontation, occurred between the Greeks and the Indo-Scythians: in a recently published coin, Artemidoros presents himself as "son of Maues",[46] and the Buner reliefs show Indo-Greeks and Indo-Scythians reveling in a Buddhist context.

The Indo-Greeks continued to rule a territory in the eastern Punjab, until the kingdom of the last Indo-Greek king Strato II was taken over by the Indo-Scythian ruler Rajuvula around 10 CE.

Western kings and Yuezhi expansion (70 BCE-)

Around eight western Indo-Greek kings are known. The last important king was Hermaeus, who reigned until around 70 BCE; soon after his death the Yuezhi took over his areas from neighbouring Bactria. Chinese chronicles (the Hou Hanshu) actually tend to suggest that the Chinese general Wen-Chung had helped negotiate the alliance of Hermaeus with the Yuezhi, against the Indo-Scythians.[47] When Hermaeus is depicted on his coins riding a horse, he is equipped with the recurve bow and bow-case of the steppes.

After 70 BCE, the Yuezhi became the new rulers of the Paropamisadae, and minted vast quantities of posthumous issues of Hermaeus up to around 40 CE, when they blend with the coinage of the Kushan king Kujula Kadphises. The first documented Yuezhi prince, Sapadbizes, ruled around 20 BCE, and minted in Greek and in the same style as the western Indo-Greek kings, probably depending on Greek mints and celators.

The last known mention of an Indo-Greek ruler is suggested by an inscription on a signet ring of the 1st century CE in the name of a king Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, in modern Pakistan. No coins of him are known, but the signet bears in kharoshthi script the inscription "Su Theodamasa", "Su" being explained as the Greek transliteration of the ubiquitous Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah", "King").

Ideology

Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, and their rule, especially that of Menander, has been remembered as benevolent. It has been suggested, although direct evidence is lacking, that their invasion of India was intended to show their support for the Mauryan empire which may have had a long history of marital alliances,[48] exchange of presents,[49] demonstrations of friendship,[50] exchange of ambassadors[51] and religious missions[52] with the Greeks. The historian Diodorus even wrote that the king of Pataliputra had "great love for the Greeks".[53][54]

The Greek expansion into Indian territory may have been intended to protect Greek populations in India,[55] and to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the Sungas.[56] The city of Sirkap founded by Demetrius combines Greek and Indian influences without signs of segregation between the two cultures.

Alternatively, the Greek invasions in India are also sometimes described as purely materialistic, only taking advantage of the ruin of the Mauryan Empire to acquire territory and wealth.

The first Greek coins to be minted in India, those of Menander I and Appolodotus I bear the mention "Saviour king" (BASILEOS SOTHROS), a title with high value in the Greek world which indicated an important deflective victory. For instance, Ptolemy I had been Soter (saviour) because he had helped save Rhodes from Demetrius the Besieger, and Antiochus I because he had saved Asia Minor from the Gauls. The title was also inscribed in Pali as ("Tratarasa") on the reverse of their coins. Menander and Apollodotus may indeed have been saviours to the Greek populations residing in India, and to some of the Indians as well.[57]

Also, most of the coins of the Greek kings in India were bilingual, written in Greek on the front and in Pali on the back (in the Kharoshthi script, derived from Aramaic, rather than the more eastern Brahmi, which was used only once on coins of Agathocles of Bactria), a tremendous concession to another culture never before made in the Hellenic world.[58] From the reign of Apollodotus II, around 80 BCE, Kharoshthi letters started to be used as mintmarks on coins in combination with Greek monograms and mintmarks, suggesting the participation of local technicians to the minting process.[59] Incidentally, these bilingual coins of the Indo-Greeks were the key in the decipherment of the Kharoshthi script by James Prinsep (1799–1840).[60] Kharoshthi became extinct around the 3rd century CE.

In Indian literature, the Indo-Greeks are described as Yavanas (in Sanskrit),[61][62] or Yonas (in Pali)[63] both thought to be transliterations of "Ionians". Direct epigraphical evidence involves the Indo-Greek kings, such as the mention of the "Yona king" Antialcidas on the Heliodorus pillar in Vidisha, or the mention of Menander I in the Buddhist text of the Milinda Panha.[64] In the Harivamsa the "Yavana" Indo-Greeks are qualified, together with the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Paradas as Kshatriya-pungava i.e foremost among the Warrior caste, or Kshatriyas. The Majjhima Nikaya explains that in the lands of the Yavanas and Kambojas, in contrast with the numerous Indian castes, there were only two classes of people, Aryas and Dasas (masters and slaves). The Arya could become Dasa and vice versa.

Religion

In addition to the worship of the Classical pantheon of the Greek deities found on their coins (Zeus, Herakles, Athena, Apollo...), the Indo-Greeks were involved with local faiths, particularly with Buddhism, but also with Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

After the Greco-Bactrians militarily occupied parts of northern India from around 180 BCE, numerous instances of interaction between Greeks and Buddhism are recorded. Menander I, the "Saviour king", seems to have converted to Buddhism, and is described in Buddhist texts as a great benefactor of the religion, on a par with Ashoka or the future Kushan emperor Kanishka.[65][failed verification] He is famous for his dialogues with the Buddhist monk Nagasena, transmitted to us in the Milinda Panha, which explain that he became a Buddhist arhat:

"And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he (Menander) handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the house-less state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!"

— The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids.

Another Indian writing, the Stupavadana of Ksemendra, mentions in the form of a prophecy that Menander will build a stupa in Pataliputra.[66]

Plutarch also presents Menander as an example of benevolent rule, and explains that upon his death, the honour of sharing his remains was claimed by the various cities under his rule, and they were enshrined in "monuments" (μνημεία, probably stupas), in a parallel with the historic Buddha:[67]

"But when one Menander, who had reigned graciously over the Bactrians, died afterwards in the camp, the cities indeed by common consent celebrated his funerals; but coming to a contest about his relics, they were difficultly at last brought to this agreement, that his ashes being distributed, everyone should carry away an equal share, and they should all erect monuments to him."

Art

Incipient Greco-Buddhist art

In general, the art of the Indo-Greeks is poorly documented, and few works of art (apart from their coins and a few stone palettes) are directly attributed to them. The coinage of the Indo-Greeks however is generally considered as some of the most artistically brilliant of Antiquity.[69] The Hellenistic heritage (Ai-Khanoum) and artistic proficiency of the Indo-Greek would suggest a rich sculptural tradition as well, but traditionally very few sculptural remains have been attributed to them. On the contrary, most Gandharan Hellenistic works of art are usually attributed to the direct successors of the Indo-Greeks in India in 1st century CE, such as the nomadic Indo-Scythians, the Indo-Parthians and, in an already decadent state, the Kushans[70] In general, Gandharan sculpture cannot be dated exactly, leaving the exact chronology open to interpretation.

The possibility of a direct connection between the Indo-Greeks and Greco-Buddhist art has been reaffirmed recently as the dating of the rule of Indo-Greek kings has been extended to the first decades of the 1st century CE, with the reign of Strato II in the Punjab.[71] Also, Foucher, Tarn and more recently Boardman, Bussagli or McEvilley have taken the view that some of the most purely Hellenistic works of northwestern India and Afghanistan, may actually be wrongly attributed to later centuries, and instead belong to a period one or two centuries earlier, to the time of the Indo-Greeks in the 2nd-1st century BCE:[72]

This is particularly the case of some purely Hellenistic works in Hadda, Afghanistan, an area which "might indeed be the cradle of incipient Buddhist sculpture in Indo-Greek style".[73] Referring to one of the Buddha triads in Hadda (drawing), in which the Buddha is sided by very Classical depictions of Herakles/Vajrapani and Tyche/Hariti, Boardman explains that both figures "might at first (and even second) glance, pass as, say, from Asia Minor or Syria of the first or second century BC (...) these are essentially Greek figures, executed by artists fully conversant with far more than the externals of the Classical style".[74] Many of the works of art at Hadda can also be compared to the style of the 2nd century BCE sculptures of the Hellenistic world, such as those of the Temple of Olympia at Bassae in Greece, which could also suggest roughly contemporary dates.[citation needed]

Alternatively, it has been suggested that these works of art may have been executed by itinerant Greek artists during the time of maritime contacts with the West from the 1st to the 3rd century CE.[75]

The supposition that such highly Hellenistic and, at the same time Buddhist, works of art belong to the Indo-Greek period would be consistent with the known Buddhist activity of the Indo-Greeks (the Milinda Panha etc...), their Hellenistic cultural heritage which would naturally have induced them to produce extensive statuary, their know artistic proficiency as seen on their coins until around 50 BCE, and the dated appearance of already complex iconography incorporating Hellenistic sculptural codes with the Bimaran casket in the early 1st century CE.[citation needed]

Indo-Greeks in the art of Gandhara

The Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, beyond the omnipresence of Greek style and stylistic elements which might be simply considered as an enduring artistic tradition,[76] offers numerous depictions of people in Greek Classical realistic style, attitudes and fashion (clothes such as the chiton and the himation, similar in form and style to the 2nd century BCE Greco-Bactrian statues of Ai-Khanoum, hairstyle), holding contraptions which are characteristic of Greek culture (amphoras, "kantaros" Greek drinking cups), in situations which can range from festive (such as Bacchanalian scenes) to Buddhist-devotional.[77][78]

Uncertainties in dating make it unclear whether these works of art actually depict Greeks of the period of Indo-Greek rule up to the 1st century BCE, or remaining Greek communities under the rule of the Indo-Parthians or Kushans in the 1st and 2nd century CE.

Stone palettes

Numerous early stone palettes found in Gandhara are considered as direct productions of the Indo-Greeks during the 2nd to the 1st century BCE.[79] The art style of the palettes later evolved under the Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthians, but production stopped with the advent of the Kushans.[80] Usually these palettes represent people in Greek dress in mythological or gallant scenes.

Hellenistic groups

A series of reliefs, several of them known as the Buner reliefs which were taken during the 19th century from Buddhist structures near the area of Buner in northern Pakistan, depict in perfect Hellenistic style gatherings of people in Greek dress, socializing, drinking or playing music.[81] Some other of these reliefs depict Indo-Scythian soldiers in uniform, sometimes playing instruments.[82] Finally, revelling Indian in dhotis richly adorned with jewelry are also shown. These are considered some of the most artistically perfect, and earliest, of Gandharan sculptures, and are thought to exalt multicultural interaction within the context of Buddhism,[citation needed] sometime during the 1st century BCE-1st century CE.

-

Takht-i-Bahi relief, dubbed "Presentation of the bride to Siddharta". The third character holds Buddhist devotional flowers, the fifth forms a benediction gesture. British Museum.

-

Greek Buddhist devotees, drinking and playing music. Buner relief. Cleveland Museum of Art.

-

Hellenistic group in more Indianized style, Zar Dheri stupa, Hazara district of Gandhara (NWFP).

Bacchic scenes

Greeks harvesting grapes, Greeks drinking and revelling, scenes of erotical courtship are also numerous, and seem to relate to some of the most remarkable traits of Greek culture.[83] These reliefs also belong to Buddhist structures, and it is sometimes suggested that they might represent some kind of paradisical world after death.

-

Bacchanalian scene, representing the harvest of wine grapes, Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, 1st-2nd century CE.

-

Indo-Greek bacchanalian scene, 1st-2nd century.

-

Satyr on a mountain goat, drinking with women. Gandhara, 2nd-4th century.

-

Bacchic erotical scene with standing Buddha. Butkara, Swat, Gandhara.

-

Musician wearing the chiton dress.

Hellenistic devotees

Depictions of people in Hellenistic dress within a Buddhist context are also numerous.[84] Some show a Greek devotee couple circambulating stupas together with shaven monks, others Greek protagonists are incorporated in Buddhist jataka stories of the life of the Buddha (relief of The Great Departure), others are simply depicted as devotees on the columns of Buddhist structures. A few famous friezes, including one in the British Museum, also depict the story of the Trojan horse. It is unclear whether these reliefs actually depict contemporary Greek devotees in the area of Gandhara, or if they are just part of a remaining artistic tradition. Most of these reliefs are usually dated to the 1st-3rd century CE.

-

Couple of devotees in Hellenistic himation dress, at the base of a Buddha statue.

-

Devotee in Greek dress, on a Buddhist pilaster. Chakhil-i-Ghoundi Stupa.

-

Man in Greek dress, inside a Buddhist arcade, National Museum of Oriental Art.

-

Man in Greek dress, seated on a folding stool and reading books. British Museum.

-

"The Great Departure", with the Buddha amid Greek deities and costumes.

-

Hellenistic man or God, Gandhara.

-

Indo-Corinthian capital representing a Buddhist devotee wearing a Greek cloak (chlamys) attached by a fibula. Dated to the 1st century BCE. Butkara Stupa.

Economy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2007) |

Very little is known about the economy of the Indo-Greeks. The abundance of their coins would tend to suggest large mining operations, particularly in the mountainous area of the Hindu-Kush, and an important monetary economy. The Indo-Greek did strike bilingual coins both in the Greek "round" standard and in the Indian "square" standard, suggesting that monetary circulation extended to all parts of society. The adoption of Indo-Greek monetary conventions by neighbouring kingdoms, such as the Kunindas to the east and the Satavahanas to the south, would also suggest that Indo-Greek coins were used extensively for cross-border trade.

Tribute payments

It would also seem that some of the coins emitted by the Indo-Greek kings, particularly those in the monolingual Attic standard, may have been used to pay some form of tribute to the Yuezhi tribes north of the Hindu-Kush. This is indicated by the coins finds of the Qunduz hoard in northern Afghanistan, which have yielded quantities of Indo-Greek coins in the Hellenistic standard (Greek weights, Greek language), although none of the kings represented in the hoard are known to have ruled so far north. Conversely, none of these coins have ever been found south of the Hindu-Kush.[85]

Trade with China

An indirect testimony by the Chinese explorer Zhang Qian, who visited Bactria around 128 BCE, suggests that intense trade with Southern China was going through northern India, and therefore probably through the contemporary Indo-Greek realm.[original research?] Zhang Qian explains that he found Chinese products in the Bactrian markets, and that they were transiting through northwestern India, which he incidentally describes as a civilization similar to that of Bactria:

"When I was in Bactria," Zhang Qian reported, "I saw bamboo canes from Qiong and cloth (silk?) made in the province of Shu. When I asked the people how they had gotten such articles, they replied: "Our merchants go buy them in the markets of Shendu (northwestern India). Shendu, they told me, lies several thousand li southeast of Bactria. The people cultivate land, and live much like the people of Bactria".

— Sima Qian, "Records of the Great Historian", trans. Burton Watson, p236.

Indian Ocean trade

Maritime relations across the Indian ocean started in the 3rd century BCE, and further developed during the time of the Indo-Greeks together with their territorial expansion along the western coast of India. The first contacts started when the Ptolemies constructed the Red Sea ports of Myos Hormos and Berenike, with destination the Indus delta, the Kathiawar peninsula or Muziris. Around 130 BCE, Eudoxus of Cyzicus is reported (Strabo, Geog. II.3.4)[86] to have made a successful voyage to India and returned with a cargo of perfumes and gemstones. By the time Indo-Greek rule was ending, up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India (Strabo Geog. II.5.12).[87]

Armed forces

The coins of the Indo-Greeks provide rich clues on their uniforms and weapons. Typical Hellenistic uniforms are depicted, with helmets being either round in the Greco-Bactrian style, or the flat kausia of the Macedonians (coins of Apollodotus I).

Military technology

Their weapons were spears, swords, longbow (on the coins of Agathokleia) and arrows. Interestingly, around 130 BCE the Central Asian recurve bow of the steppes with its gorytos box starts to appear for the first time on the coins of Zoilos I, suggesting strong interactions (and apparently an alliance) with nomadic peoples, either Yuezhi or Scythian. The recurve bow becomes a standard feature of Indo-Greek horsemen by 90 BCE, as seen on some of the coins of Hermaeus.

Generally, Indo-Greek kings are often represented riding horses, as early as the reign of Antimachus II around 160 BCE. The equestrian tradition probably goes back to the Greco-Bactrians, who are said by Polybius to have faced a Seleucid invasion in 210 BCE with 10,000 horsemen.[88] Although war elephants are never represented on coins, a harness plate (phalera) dated to the 3-2nd century BCE, today in the Hermitage Museum, depicts a helmetted Greek combatant on an Indian war elephant, and would be either Greco-Bactrian or Indo-Greek work. Indian war elephants were a standard feature of Hellenistic armies, and this would naturally have been the case for the Indo-Greeks as well.

The Milinda Panha, in the questions of Nagasena to king Menander, provides a rare glimpse of the military methods of the period:

- "(Nagasena) Has it ever happened to you, O king, that rival kings rose up against you as enemies and opponents?

- -(Menander) Yes, certainly.

- -Then you set to work, I suppose, to have moats dug, and ramparts thrown up, and watch towers erected, and strongholds built, and stores of food collected?

- -Not at all. All that had been prepared beforehand.

- -Or you had yourself trained in the management of war elephants, and in horsemanship, and in the use of the war chariot, and in archery and fencing?

- -Not at all. I had learnt all that before.

- -But why?

- -With the object of warding off future danger."

- (Milinda Panha, Book III, Chap 7)

The Milinda Panha also describes the structure of Menander's army:

- "Now one day Milinda the king proceeded forth out of the city to pass in review the innumerable host of his mighty army in its fourfold array (of elephants, cavalry, bowmen, and soldiers on foot)." (Milinda Panha, Book I)

Size of Indo-Greek armies

The armed forces of the Indo-Greeks during their invasion of India must have been quite considerable, as suggested by their ability to topple local rulers, but also by the size of the armed reaction of some Indian rulers.[citation needed] The ruler of Kalinga, Kharavela, claims in the Hathigumpha inscription that he led a "large army" in the direction of Demetrius' own "army" and "transports", and that he induced him to retreat from Pataliputra to Mathura. A "large army" for the state of Kalinga must indeed have been quite considerable. The Greek ambassador Megasthenes took special note of the military strength of Kalinga in his Indica in the middle of the 3rd century BCE:

"The royal city of the Calingae (Kalinga) is called Parthalis. Over their king 60,000 foot-soldiers, 1,000 horsemen, 700 elephants keep watch and ward in "procinct of war."

— Megasthenes fragm. LVI. in Plin. Hist. Nat. VI. 21. 8–23. 11.[90]

That this kind of military strength was needed to confront the Indo-Greeks is indicative of the Indo-Greeks' own military commitment.

An account by the Roman writer Justin gives another hint of the size of Indo-Greek armies, which, in the case of the conflict between the Greco-Bactrian Eucratides and the Indo-Greek Demetrius II, he numbers at 60,000 (although they allegedly lost to 300 Greco-Bactrians):

"Eucratides led many wars with great courage, and, while weakened by them, was put under siege by Demetrius, king of the Indians. He made numerous sorties, and managed to vanquish 60,000 enemies with 300 soldiers, and thus liberated after four months, he put India under his rule"

— Justin, XLI,6[92]

These are considerable numbers, as large armies during the Hellenistic period typically numbered between 20,000 to 30,000.[93]

However, the military strength of nomadic tribes from Central Asia (Yuezhi and Scythians) probably constituted a significant threat to the Indo-Greeks. According to Zhang Qian, the Yuezhi represented a considerable force of between 100,000 and 200,000 mounted archer warriors,[94] with customs identical to those of the Xiongnu.

Finally, the Indo-Greek seem to have combined forces with other "invaders" during their expansion into India, since they are often referred to in combination with others (especially the Kambojas), in the Indian accounts of their invasions.[citation needed]

Enduring legacy of the Indo-Greek Kingdom

From the 1st century CE, the Greek communities of central Asia and northwestern India lived under the control of the Kushan branch of the Yuezhi, apart from a short-lived invasion of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom.[95] The Kushans founded the Kushan Empire, which was to prosper for several centuries. In the south, the Greeks were under the rule of the Western Kshatrapas. It is unclear how much longer the Greeks managed to maintain a distinct presence in the Indian sub-continent.

List of the Indo-Greek kings and their territories

Today 36 Indo-Greek kings are known. Several of them are also recorded in Western and Indian historical sources, but the majority are known through numismatic evidence only. The exact chronology and sequencing of their rule is still a matter of scholarly inquiry, with adjustments regular being made with new analysis and coin finds (overstrikes of one king over another's coins being the most critical element in establishing chronological sequences).[96]

References

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1991). Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (in French). Bibliothèque Nationale de France. ISBN 2-7177-1825-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The ancient past. Routledge. ISBN 0415356164.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Faccenna, Domenico (1980). Butkara I (Swāt, Pakistan) 1956–1962, Volume III 1. Rome: IsMEO (Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente).

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts. ISBN 1-58115-203-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Puri, Baij Nath (2000). Buddhism in Central Asia. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0372-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Tarn, W. W. (1984). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Chicago: Ares. ISBN 0-89005-524-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Narain, A.K. (2003). The Indo-Greeks. B.R. Publishing Corporation.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) "revised and supplemented" from Oxford University Press edition of 1957. - Narain, A.K. (1976). The coin types of the Indo-Greeks kings. Chicago, USA: Ares Publishing. ISBN 0-89005-109-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Cambon, Pierre (2007). Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés (in French). Musée Guimet. ISBN 9782711852185.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Keown, Damien (2003). A Dictionary of Buddhism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860560-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (in French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 2-9516679-2-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03680-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Errington, Elizabeth (1992). The Crossroads of Asia : transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Cambridge: Ancient India and Iran Trust. ISBN 0-9518399-1-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Bopearachchi, Osmund (1993). Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 36240864.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - 東京国立博物館 (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan); 兵庫県立美術館 (Hyogo Kenritsu Bijutsukan) (2003). Alexander the Great : East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan. Tokyo: 東京国立博物館 (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan). OCLC 53886263.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lowenstein, Tom (2002). The vision of the Buddha : Buddhism, the path to spiritual enlightenment. London: Duncan Baird. ISBN 1-903296-91-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Foltz, Richard (2000). Religions of the Silk Road : overland trade and cultural exchange from antiquity to the fifteenth century. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-23338-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Marshall, Sir John Hubert (2000). The Buddhist art of Gandhara : the story of the early school, its birth, growth, and decline. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 81-215-0967-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Mitchiner, John E. (1986). The Yuga Purana : critically edited, with an English translation and a detailed introduction. Calcutta, India: Asiatic Society. OCLC 15211914 ISBN 81-7236-124-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Salomon, Richard. "The "Avaca" Inscription and the Origin of the Vikrama Era". Vol. 102.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=,|coauthors=, and|month=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Banerjee, Gauranga Nath (1961). Hellenism in ancient India. Delhi: Munshi Ram Manohar Lal. OCLC 1837954 ISBN 0-8364-2910-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Bussagli, Mario (1996). L'art du Gandhara (in French). Paris: Librairie générale française. ISBN 2-253-13055-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Marshall, John (1956). Taxila. An illustrated account of archaeological excavations carried out at Taxila (3 volumes). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Afghanistan, ancien carrefour entre l'est et l'ouest" (in French/English). Belgium: Brepols. 2005. ISBN 2503516815.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Seldeslachts, E. (2003). The end of the road for the Indo-Greeks?. (Also available online): Iranica Antica, Vol XXXIX, 2004.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|location= - Senior, R.C. (2006). Indo-Scythian coins and history. Volume IV. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. ISBN 0-9709268-6-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Notes

- ^ Sources for the map: "Historical Atlas of Peninsular India" Oxford University Press (dark blue, continuous line), A.K. Narain "The coins of the Indo-Greek kings" (dark blue, dotted line), Westermans "Atlas der Welt Gesishte" (light blue, dotted line).

- ^ As in other compounds such as "Franco-Canadian", "African-American" , "Indo-European" etc..., the area of origin usually comes first, and the area of arrival comes second, so that "Greco-Indian" is normally a more accurate nomenclature than "Indo-Greek". The latter however has become the general usage, especially since the publication of Narain's book "The Indo-Greeks".

- ^ Euthydemus I was, according to Polybius11.34, a Magnesian Greek. His son, Demetrius I, founder of the Indo-Greek kingdom, was therefore of Greek ethnicity at least by his father. Demetrius also married a daughter of the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III (who had some Persian descent) according to the same Polybius [failed verification]11.34. The ethnicity of later Indo-Greek rulers is less clear ("Notes on Hellenism in Bactria and India". W. W. Tarn. Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 22 (1902), pages 268–293). For example, Artemidoros (80 BCE) may have been of Indo-Scythian ascendency. Some level of inter-marriage may also have occurred, as exemplified by Alexander III of Macedon (who married Roxana of Bactria) or Seleucus (who married Apama).

- ^ Mortimer Wheeler Flames over Persepolis (London, 1968). Pp. 112 ff. It is unclear whether the Hellenistic street plan found by Sir John Marshall's excavations dates from the Indo-Greeks or from the Kushans, who would have encountered it in Bactria; Tarn (1951, pp. 137, 179) ascribes the initial move of Taxila to the hill of Sirkap to Demetrius I, but sees this as "not a Greek city but an Indian one"; not a polis or with a Hippodamian plan.

- ^ "Even if Sagala proves to be Sialkot, it does not seem to be Menander's capital"; Menander came down to Sagala to meet Nagasena, "as the Ganges flows to the sea." Narain "The Indo-Greeks",(1957, p.81) p.237 McEvilley supports Tarn on both points, citing Woodcock.

- ^ :"To the colonies settled in India, Python, the son of Agenor, was sent." Justin XIII.4

- ^ On the participation of the Yavanas to Chandragupta's campaigns: "Kusumapura was besieged from every direction by the forces of Parvata and Chandragupta: Shakas, Yavanas, Kiratas, Kambojas, Parasikas, Bahlikas and others, assembled on the advice of Chanakya" Mudrarakshasa 2. Sanskrit original: "asti tava Shaka-Yavana-Kirata-Kamboja-Parasika-Bahlika parbhutibhih Chankyamatipragrahittaishcha Chandergupta Parvateshvara balairudidhibhiriva parchalitsalilaih samantaad uprudham Kusumpurama". From the French translation, in "Le Ministre et la marque de l'anneau", ISBN 2-7475-5135-0

- ^ Strabo 15.2.1(9)

- ^ Classical sources have recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus: "And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters [as to make people more amourous]. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love" Athenaeus of Naucratis, "The deipnosophists" Book I, chapter 32 Ath. Deip. I.32

- ^ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII

- ^ "The finest of the pillars were executed by Greek or Perso-Greek sculptors; others by local craftsmen, with or without foreign supervision" Marshall, "The Buddhist art of Gandhara", p4

- ^ "A number of foreign artisans, such as the Persians or even the Greeks, worked alongside the local craftsmen, and some of their skills were copied with avidity" Burjor Avari, "India, The ancient past", p118

- ^ Polybius 11.39

- ^ Pushyamitra is described as a "senapati" (Commander-in-chief) of Brhadrata in the Puranas

- ^ E. Lamotte: History of Indian Buddhism, Institut Orientaliste, Louvain-la-Neuve 1988 (1958), p. 109.

- ^ Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas by Romila Thapar, Oxford University Press, 1960 P200

- ^ "The Greek conquest of the North-West Punjab was probably effected towards the latter end of the reign of Euthydemos, or during the early carreer of his son Demetrios." Whitehead, p.5

- ^ "Demetrios is known as the first king of Bactria and of India, that is to say, he held sway both in Bactria proper, and also in Gandhara" Whitehead, p.5

- ^ "In that year (180 BC) Greek forces based in Bactria reconquered much of what Candragupta had taken upon the departure of Alexander's army a century and a half earlier", McEvilley, p.362.

- ^ Narain says of Menander, not Demetrius: "There is certainly some truth in Apollodorus and Strabo when they attribute to Menander the advances made by the Greeks of Bactria beyond the Hypanis and even as far as the Ganges and Palibothra (...) That the Yavanas advanced even beyond in the east, to the Ganges-Jamuna valley, about the middle of the second century BC is supported by the cumulative evidence provided by Indian sources", Narain, "The Indo-Greeks" p.267

- ^ "Pataliputra fut occupée par les forces coalisées Grecques pendant presque huit ans" ("Pataliputra was occupied by the Greek coalition for about eight years"), Mario Bussagli, "L'Art du Gandhara", p100

- ^ "Narain reedits and retranslated the Yuga Purana passage to get the Greeks out of Pataliputra. Still, he allows Greek soldiers to lay siege to the city, which is the minimum that the text can be construed to say" McEvilley, p.371

- ^ "Menander became the ruler of a kingdom extending along the coast of western India, including the whole of Saurashtra and the harbour Barukaccha. His territory also included Mathura, the Punjab, Gandhara and the Kabul Valley", Bussagli p101

- ^ "Menander, the probable conqueror of Pataliputra", McEvilley, p.375

- ^ "No king anywhere before him had assumed this title", Tarn, p.132

- ^ The title "Anicetus" for Demetrius is visible on the pedigree coins minted by Agathocles.

- ^ In the 1st century BCE, the geographer Isidorus of Charax mentions Parthians ruling over Greek populations and cities in Arachosia: "Beyond is Arachosia. And the Parthians call this White India; there are the city of Biyt and the city of Pharsana and the city of Chorochoad and the city of Demetrias; then Alexandropolis, the metropolis of Arachosia; it is Greek, and by it flows the river Arachotus. As far as this place the land is under the rule of the Parthians." "Parthians stations", 1st century BCE. Mentioned in Bopearachchi, "Monnaies Greco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques", p52. Original text in paragraph 19 of Parthian stations

- ^ The word for "advance" is "προελθοντες", meaning a military expedition. Strabo 15-1-27

- ^ "Pataliputra fut occupée par les forces coalisées Grecques pendant presque huit ans" ("Pataliputra was occupied by the Greek coalition for about eight years"), Mario Bussagli, "L'Art du Gandhara", p100

- ^ "Menander became the ruler of a kingdom extending along the coast of western India, including the whole of Saurashtra and the harbour Barukaccha. His territory also included Mathura, the Punjab, Gandhara and the Kabul Valley", Bussagli p101)

- ^ Strabo on the extent of the conquests of the Greco-Bactrians/Indo-Greeks: "They took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis. In short, Apollodorus says that Bactriana is the ornament of Ariana as a whole; and, more than that, they extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni." Strabo 11.11.1 (Strabo 11.11.1)

- ^ "A distinctive series of Indo-Greek coins has been found at several places in central India: including at Dewas, some 22 miles to the east of Ujjain. These therefore add further definite support to the likelihood of an Indo-Greek presence in Malwa" Mitchener, "The Yuga Purana", p.64

- ^ "Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian institution", Bopearachchi, p16.

- ^ "For any scholar engaged in the study of the presence of the Indo-Greeks or Indo-Scythians before the Christian Era, the Yuga Purana is an important source material" Dilip Coomer Ghose, General Secretary, The Asiatic Society, Kolkata, 2002

- ^ "The greatest city in India is that which is called Palimbothra, in the dominions of the Prasians [...] Megasthenes informs us that this city stretched in the inhabited quarters to an extreme length on each side of eighty stadia, and that its breadth was fifteen stadia, and that a ditch encompassed it all round, which was six hundred feet in breadth and thirty cubits in depth, and that the wall was crowned with 570 towers and had four-and-sixty gates." Arr. Ind. 10. "Of Pataliputra and the Manners of the Indians.", quoting Megasthenes Text

- ^ Source: "A guide to Sanchi" John Marshall. These "Greek-looking foreigners" are also described in Susan Huntington, "The art of ancient India", p100.

- ^ Whitehead, p.4

- ^ Bopearachchi, p.85

- ^ Bopearachchi, p.72

- ^ "Numismats and historians are unanimous in considering that Menander was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, and the most famous of the Indo-Greek kings. The coins to the name of Menander are incomparably more abundant than those of any other Indo-Greek king" Bopearachchi, "Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques", p76.

- ^ Bopearachchi, "Monnaies", p.86

- ^ Tarn

- ^ "By about 130 BC nomadic people from the Jaxartes region had overrun the northern boundary of Bactria itself", McEvilley, p.372

- ^ "Heliocles abandonned Bactria and moved his capital to the Kabul Valley, thence to tule his Indian holdings." McEvilley, p.372

- ^ The Sanskrit inscription reads "Yavanarajyasya sodasuttare varsasate 100 10 6". R.Salomon, "The Indo-Greek era of 186/5 B.C. in a Buddhist reliquary inscription", in "Afghanistan, ancien carrefour entre l'est et l'ouest", p373

- ^ Described in R.C. Senior "The Decline of the Indo-Greeks" [1]. See also this source.

- ^ Following the embassy of Zhang Qian in Central Asia around 126 BCE, from around 110 BCE "more and more envoys (from China) were sent to Anxi (Parthia), Yancai, Lixuan, Tiazhi, and Shendu (India)... The largest embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred person, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members" ("Records of the Grand Historian", by Sima Qian, trans. Robert Watson, p240–241). According to the Hou Hanshu, W'ou-Ti-Lao (Spalirises), king of Ki-pin (Kophen, upper Kabul valley), killed some Chinese envoys. After the death of the king, his son (Spalagadames) sent an envoy to China with gifts. The Chinese general Wen-Chung, commander of the border area in western Gansu, accompanied the escort back. W'ou-Ti-Lao's son formented to kill Wen-Chung. When Wen-Chung discovered the plot, he allied himself with Yin-Mo-Fu (Hermaeus), "son of the king of Yung-Kiu" (Yonaka, the Greeks). They attacked Ki-Pin (possibly with the support of the Yuezhi, themselves allies of the Chinese since around 100 BCE according to the Hou Hanshu) and killed W'ou-Ti-Lao's son. Yin-Mo-Fu (Hermaeus) was then installed as king of Ki-Pin, as a vassal of the Chinese Empire, and receiving the Chinese seal and ribbon of investiture. Later Yin-Mo-Fu (Hermaeus) himself is recorded to have killed Chinese envoys in the reign of Emperor Yuan-ti (48-33 BCE), then sent envoys to apologize to the Chinese court, but he was disregarded. During the reign of Emperor Ching-ti (51-7 BCE) other envoys were sent, but they were rejected as simple traders. (Tarn, "The Greeks in Bactria and India")

- ^ Marital alliances:

- Discussion on the dynastic alliance in Tarn, pp. 152–153: "It has been recently suggested that Asoka was grandson of the Seleucid princess, whom Seleucus gave in marriage to Chandragupta. Should this far-reaching suggestion be well founded, it would not only throw light on the good relations between the Seleucid and Maurya dynasties, but would mean that the Maurya dynasty was descended from, or anyhow connected with, Seleucus… when the Mauryan line became extinct, he (Demetrius) may well have regarded himself, if not as the next heir, at any rate as the heir nearest at hand". Also: "The Seleucid and Maurya lines were connected by the marriage of Seleucus' daughter (or niece) either to Chandragupta or his son Bindusara" John Marshall, Taxila, p20. This thesis originally appeared in "The Cambridge Shorter History of India": "If the usual oriental practice was followed and if we regard Chandragupta as the victor, then it would mean that a daughter or other female relative of Seleucus was given to the Indian ruler or to one of his sons, so that Asoka may have had Greek blood in his veins." The Cambridge Shorter History of India, J. Allan, H. H. Dodwell, T. Wolseley Haig, p33 Source.

- Description of the 302 BCE marital alliance in Strabo 15.2.1(9): "The Indians occupy [in part] some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus in consequence of a marriage contract, and received in return five hundred elephants." The ambassador Megasthenes was also sent to the Mauryan court on this occasion.

- ^ Exchange of presents:

- Classical sources have recorded that Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus: "And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters [as to make people more amourous]. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love" Athenaeus of Naucratis, "The deipnosophists" Book I, chapter 32 Ath. Deip. I.32

- Ashoka claims he introduced herbal medicine in the territories of the Greeks, for the welfare of humans and animals (Edict No2).

- Bindusara asked Antiochus I to send him some sweet wine, dried figs and a sophist: "But dried figs were so very much sought after by all men (for really, as Aristophanes says, "There's really nothing nicer than dried figs"), that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus, entreating him (it is Hegesander who tells this story) to buy and send him some sweet wine, and some dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antiochus wrote to him in answer, "The dry figs and the sweet wine we will send you; but it is not lawful for a sophist to be sold in Greece" Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae" XIV.67Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae" XIV.67

- ^ Treaties of friendship:

- When Antiochos III, after having made peace with Euthydemus, went to India in 209 BCE, he is said to have renewed his friendship with the Indian king there and received presents from him: "He crossed the Caucasus (Hindu Kush) and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king had agreed to hand over to him."Polybius 11.39

- ^ Ambassadors:

- Known ambassadors to India are Megasthenes, Deimakos and Dionysius.

- ^ Religious missions:

- In the Edicts of Ashoka, king Ashoka claims to have sent Buddhist emissaries to the Hellenistic west around 250 BCE.

- ^ The historian Diodorus wrote that the king of Pataliputra, apparently a Mauryan king, "loved the Greeks": "Iambulus, having found his way to a certain village, was then brought by the natives into the presence of the king of Palibothra, a city which was distant a journey of many days from the sea. And since the king loved the Greeks ("Philhellenos") and devoted to learning he considered Iambulus worthy of cordial welcome; and at length, upon receiving a permission of safe-conduct, he passed over first of all into Persia and later arrived safe in Greece" Diodorus ii,60.

- ^ "Diodorus testifies to the great love of the king of Palibothra, apparently a Mauryan king, for the Greeks" Narain, "The Indo-Greeks", p362

- ^ "Obviously, for the Greeks who survived in India and suffered from the oppression of the Sunga (for whom they were aliens and heretics), Demetrios must have appeared as a saviour" Mario Bussagli, p. 101

- ^ "We can now, I think, see what the Greek 'conquest' meant and how the Greeks were able to traverse such extraordinary distances. To parts of India, perhaps to large parts, they came, not as conquerors, but as friends or 'saviors'; to the Buddhist world in particular they appeared to be its champions" (Tarn, p. 180)

- ^ Tarn p. 175. Also: "The people to be 'saved' were in fact usually Buddhists, and the common enimity of Greek and Buddhists to the Sunga king threw them into each other's arms", Tarn p. 175. "Menander was coming to save them from the oppression of the Sunga kings",Tarn p. 178

- ^ Whitehead, "Indo-Greek coins", p 3-8

- ^ Bopearachchi p. 138

- ^ Whitehead, p.vi

- ^ "These Indo-Greeks were called Yavanas in ancient Indian litterature" p.9 + note 1 "The term had a precise meaning until well into the Christian era, when gradually its original meaning was lost and, like the word Mleccha, it degenerated into a general term for a foreigner" p.18, Narain "The Indo-Greeks"

- ^ "The term Yavana may well have been first applied by the Indians to the Greeks of various cities of Asia Minor who were settled in the areas contiguous to north-west India" Narain "The Indo-Greeks", p.227

- ^ "Of the Sanskrit Yavana, there are other forms and derivatives, viz. Yona, Yonaka, Javana, Yavana, Jonon or Jononka, Ya-ba-na etc... Yona is a normal Prakrit form from Yavana", Narain "The Indo-Greeks", p.228

- ^ "Before the Greeks came, Ashoka called the Greeks Yonas, while after they came, the Milinda calls them Yonakas",Tarn, quoted in Narain, "The Indo-Greeks", p.228

- ^ "Menander, the probable conqueror of Pataliputra, seems to have been a Buddhist, and his name belongs in the list of important royal patrons of Buddhism along with Asoka and Kanishka", McEvilley, p.375

- ^ Stupavadana, Chapter 57, v15. Quotes in E.Seldeslachts.

- ^ McEvilley, p.377

- ^ Plutarch "Political precepts", p147–148 Full text

- ^ "The extraordinary realism of their portraiture. The portraits of Demetrius, Antimachus and of Eucratides are among the most remarkable that have come down to us from antiquity" Hellenism in Ancient India, Banerjee, p134

- ^ "Just as the Frank Clovis had no part in the development of Gallo-Roman art, the Indo-Scythian Kanishka had no direct influence on that of Indo-Greek Art; and besides, we have now the certain proofs that during his reign this art was already stereotyped, of not decadent" Hellenism in Ancient India, Banerjee, p147

- ^ "The survival into the 1st century AD of a Greek administration and presumably some elements of Greek culture in the Punjab has now to be taken into account in any discussion of the role of Greek influence in the development of Gandharan sculpture", The Crossroads of Asia, p14

- ^ On the Indo-Greeks and the Gandhara school:

- 1) "It is necessary to considerably push back the start of Gandharan art, to the first half of the first century BCE, or even, very probably, to the preceding century.(...) The origins of Gandharan art... go back to the Greek presence. (...) Gandharan iconography was already fully formed before, or at least at the very beginning of our era" Mario Bussagli "L'art du Gandhara", p331–332

- 2) "The beginnings of the Gandhara school have been dated everywhere from the first century B.C. (which was M.Foucher's view) to the Kushan period and even after it" (Tarn, p394). Foucher's views can be found in "La vieille route de l'Inde, de Bactres a Taxila", pp340–341). The view is also supported by Sir John Marshall ("The Buddhist art of Gandhara", pp5–6).

- 3) Also the recent discoveries at Ai-Khanoum confirm that "Gandharan art descended directly from Hellenized Bactrian art" (Chaibi Nustamandy, "Crossroads of Asia", 1992).

- 4) On the Indo-Greeks and Greco-Buddhist art: "It was about this time (100 BCE) that something took place which is without parallel in Hellenistic history: Greeks of themselves placed their artistic skill at the service of a foreign religion, and created for it a new form of expression in art" (Tarn, p393). "We have to look for the beginnings of Gandharan Buddhist art in the residual Indo-Greek tradition, and in the early Buddhist stone sculpture to the South (Bharhut etc...)" (Boardman, 1993, p124). "Depending on how the dates are worked out, the spread of Gandhari Buddhism to the north may have been stimulated by Menander's royal patronage, as may the development and spread of the Gandharan sculpture, which seems to have accompanied it" McEvilley, 2002, "The shape of ancient thought", p378.

- ^ Boardman, p141

- ^ Boardman, p143