Stateside Puerto Ricans: Difference between revisions

Puerto Rican = Puertorriqueño, American = Americano. It's not that hard to figure it out. Added ref that uses puertorriqueño americano for source. |

Re-added true and relevant information, but this time, added sources. Also, removed untrue and biased information. Read the source! |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

== Demographics of Stateside Puerto Ricans == |

== Demographics of Stateside Puerto Ricans == |

||

===Race=== |

|||

Half of the Puerto Rican American population is of Southern European descent, primarily descending from [[Spanish people|Spain]]. A large portion of the population is made up of multi-racials, especially mixed race groups such as [[Mulatto]], [[Mestizo]], and [[Tri-racial]], having significant amounts of European, African, and Taino ancestry. There are a smaller number of [[Afro-Puerto Rican]]s. |

|||

{{cite web |url=http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf |title=Race of Major Hispanic Groups: 2010 |accessdate= |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]] |publisher=[[Pew Research Center|Pew Hispanic Center]]}} |

|||

{|class="sort wikitable sortable" style="float:right; style="font-size: 95%" |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan=6|Race by Puerto Rican national Origin, 2010<ref name="pewhispanic.org" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan=1|Country of Origin |

|||

! [[White Hispanic|White]] |

|||

! [[Black Hispanic|Black]] |

|||

! [[Taino people|Taino]] |

|||

! [[Asia|Asian]] |

|||

! [[Multiracial|Mixed-race]] |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan=1| '''[[Puerto Rico]]'''||53.1%||8.7%||0.9%||0.5%||36.7% |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan=1|'''Total: 4,623,716'''||2,455,534||403,372||42,504||24,312||1,697,944 |

|||

|} |

|||

===Population history=== |

|||

In 1950, about a quarter of a million Puerto Rican natives lived "stateside," or in the United States. In March 2012 that figure had risen to about 1.5 million. That is, slightly less than a third of the 5 million Puerto Ricans living stateside were born on the island.<ref name="Puerto Ricans in the US"/><ref name="dominicantoday.com"/> Puerto Ricans are also the second-largest Hispanic group in the USA after those of Mexican descent.<ref name="content.usatoday.com">{{cite news| url=http://content.usatoday.com/dist/custom/gci/InsidePage.aspx?cId=thedailyjournal&sParam=53490820.story | work=USA Today | title=Puerto Rico's population exodus is all about jobs | date=March 11, 2012}}</ref> |

In 1950, about a quarter of a million Puerto Rican natives lived "stateside," or in the United States. In March 2012 that figure had risen to about 1.5 million. That is, slightly less than a third of the 5 million Puerto Ricans living stateside were born on the island.<ref name="Puerto Ricans in the US"/><ref name="dominicantoday.com"/> Puerto Ricans are also the second-largest Hispanic group in the USA after those of Mexican descent.<ref name="content.usatoday.com">{{cite news| url=http://content.usatoday.com/dist/custom/gci/InsidePage.aspx?cId=thedailyjournal&sParam=53490820.story | work=USA Today | title=Puerto Rico's population exodus is all about jobs | date=March 11, 2012}}</ref> |

||

| Line 328: | Line 349: | ||

The largest populations of Puerto Ricans are situated in the following metropolitan areas (Source: Census 2010): |

The largest populations of Puerto Ricans are situated in the following metropolitan areas (Source: Census 2010): |

||

# [[New York metropolitan area|New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA MSA]] - 1,177,430 |

|||

# [[New York metropolitan area|New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA MSA]] - 1,177,430; note, the Census estimate for the largest Puerto Rican metropolis outside San Juan has increased to 1,201,850 in 2012.<ref name = 2012PRest>{{cite web|url=http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_DP05&prodType=table|title=Geographies - New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA Metro Area ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates|publisher=United States Census Bureau|accessdate=November 9, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

# [[Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL MSA]] - 269,781 |

# [[Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL MSA]] - 269,781 |

||

# [[Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD MSA]] - 238,866 |

# [[Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD MSA]] - 238,866 |

||

| Line 345: | Line 366: | ||

* [[Philadelphia]]: 121,643 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;<ref name="2010 Census"/> compared to 91,527 in 2000, increase of 30,116; representing 8.0% of the city's total population and 68% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's largest Hispanic group. |

* [[Philadelphia]]: 121,643 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;<ref name="2010 Census"/> compared to 91,527 in 2000, increase of 30,116; representing 8.0% of the city's total population and 68% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's largest Hispanic group. |

||

* [[Chicago]]: 102,703 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;<ref name="2010 Census"/> compared to 113,055 in 2000, |

* [[Chicago]]: 102,703 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;<ref name="2010 Census"/> compared to 113,055 in 2000, decrease of 10,352; representing 3.8% of the city's total population and 15% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's second largest Hispanic group. |

||

The top 25 US communities with the highest populations of Puerto Ricans (Source: Census 2010) |

The top 25 US communities with the highest populations of Puerto Ricans (Source: Census 2010) |

||

# [[New York City|New York City, NY]] - 723,621 |

|||

# [[New York City|New York City, NY]] - 723,621; note, the Census estimate for the city proper with the largest Puerto Rican population by a significant margin has increased to 730,848 in 2012.<ref name = 2012PRestNYC>{{cite web|url=http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_DP05&prodType=table|title=Geographies - New York city, New York ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates|publisher=United States Census Bureau|accessdate=November 10, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

# [[Philadelphia|Philadelphia, PA]] - 121,643 |

# [[Philadelphia|Philadelphia, PA]] - 121,643 |

||

# [[Chicago|Chicago, IL]] - 102,703 |

# [[Chicago|Chicago, IL]] - 102,703 |

||

| Line 404: | Line 425: | ||

# [[Dunkirk, New York|Dunkirk, NY]] - 22.14% |

# [[Dunkirk, New York|Dunkirk, NY]] - 22.14% |

||

# [[Bridgeport, Connecticut|Bridgeport, CT]] - 22.10% |

# [[Bridgeport, Connecticut|Bridgeport, CT]] - 22.10% |

||

# [[Sky Lake, Florida|Sky Lake, FL]] - 22.09% |

|||

The 10 large cities (over 200,000 in population) with the highest percentages of Puerto Rican residents include:<ref name="factfinder2.census.gov"/> |

The 10 large cities (over 200,000 in population) with the highest percentages of Puerto Rican residents include:<ref name="factfinder2.census.gov"/> |

||

| Line 423: | Line 443: | ||

[[File:PR Migration 1995-2000.jpg|300px|right|thumb|Puerto Rican migration patterns, 1995-2000 (graphic by Angelo Falcón)]] |

[[File:PR Migration 1995-2000.jpg|300px|right|thumb|Puerto Rican migration patterns, 1995-2000 (graphic by Angelo Falcón)]] |

||

New York was the only state to register, the reasons for and impact of these declines have yet to be fully researched. Especially in the New York case, this has been the subject of much speculation but little serious analysis to date. But it is quite clear that most of the migration was to Central Florida. Between New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago, the cities with the three largest Puerto Rican populations, Philadelphia is the only one that actually seen an increase, while the other two have seen decreases. This is probably due to Philadelphia's proximity to New York City, and its cheaper cost of living.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> In addition, despite this decline, New York City remains a major hub for migration from Puerto Rico and within the United States. |

|||

New York was the only state to register a decrease in its Puerto Rican population between 1995 and 2000, although this trend has dramatically reversed more recently, with net Puerto Rican migration into New York State, whose Puerto Rican population is estimated by the U.S. Census Bureau to have increased from 1,070,558 in 2010, to 1,094,440 in 2012.<ref name = 2012PRestNYState>{{cite web|url=http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_DP05&prodType=table|title=Geographies - New York ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates|publisher=United States Census Bureau|accessdate=November 10, 2013}}</ref> Unlike the initial pattern of migration several decades ago, this second Puerto Rican migration into New York State is being driven by movement not only into New York City proper, but also into the city's surrounding suburban areas. Philadelphia notably witnessed a substantial increase in its Puerto Rican population between 2000 and 2010.<ref name="2010 Census"/> |

|||

===Dispersion=== |

===Dispersion=== |

||

Revision as of 20:06, 20 January 2014

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| throughout the Northeast, Florida, Chicago Metro Area, and Cleveland Metro Area, with growing populations in other Southeastern States | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Spanish and English | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Protestant, Roman Catholic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Criollos, Mestizos, Mulattos, Taíno, African people, Europeans | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Hispanic and Latino Americans |

|---|

A Puerto Rican American (Spanish: Puertorriqueño americano or Puertorriqueño estadounidense), or Stateside Puerto Rican,[2][3] is an American born in either Puerto Rico or the United States that is of full or partial Puerto Rican origin and has lived a significant part of their lives in one of the states of the United States or the District of Columbia."[4]

At nine percent of the Latino population in the United States, Puerto Ricans are the second largest Hispanic group nationwide, and comprise 1.5% of the entire population of the United States.[5] Although the 2010 Census counted the number of Puerto Ricans living in the United States at 4.6 million, more recent estimates show the Puerto Rican population to be over 5 million, as of 2012.[6][7]

Despite new demographic trends, New York City continues to be home to the largest Puerto Rican American community in the United States, with Philadelphia having the second largest Puerto Rican community. The portmanteau "Nuyorican" refers to Puerto Ricans and their descendants in and around New York. A large portion of the Puerto Rican population in the United States reside in the Northeastern states and Florida, though there are significant Puerto Rican populations in the Chicago metropolitan area and other areas in Ohio, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Georgia, Texas, and California, among others.

Identity

Puerto Ricans have been migrating to the United States since the 19th century and have a long history of collective social advocacy for their political and social rights and preserving their cultural heritage. In New York City, which has the largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the United States, they began running for elective office in the 1920s, electing one of their own to the New York State Assembly for the first time in 1937.[8]

Important Puerto Rican institutions have emerged from this long history.[9] Aspira was established in New York City in 1961 and is now one of the largest national Latino nonprofit organizations in the United States.[10] There is also the National Puerto Rican Coalition in Washington, DC, the National Puerto Rican Forum, the Puerto Rican Family Institute, Boricua College, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies of the City University of New York at Hunter College, the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, the National Conference of Puerto Rican Women, and the New York League of Puerto Rican Women, Inc., among others.

The government of Puerto Rico has a long history of involvement with the stateside Puerto Rican community.[11] In July 1930, Puerto Rico's Department of Labor established an employment service in New York City.[12] The Migration Division (known as the "Commonwealth Office"), also part of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor, was created in 1948, and by the end of the 1950s, was operating in 115 cities and towns stateside.[13]

Migration history

Since 1898, Puerto Rico has been under the control of the United States, fueling migratory patterns between the mainland and the island. Even during Spanish rule, Puerto Ricans settled in the US. However, it was not until the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898 that a significant influx of Puerto Rican workers to the US began. With its 1898 victory, the United States acquired Puerto Rico from Spain and has retained sovereignty since. The 1917 Jones–Shafroth Act made all Puerto Ricans US citizens, freeing them from immigration barriers. The massive migration of Puerto Ricans to the United States was largest in the early and late 20th century.[14][dead link]

U.S political and economic interventions in Puerto Rico created the conditions for emigration, "by concentrating wealth in the hands of US corporations and displacing workers."[15] Policymakers promoted "colonization plans and contract labour programs to reduce the population. US employers, often with government support, recruited Puerto Ricans as a source of low-wage labour to the United States and other destinations."[16]

Puerto Ricans migrated in search of higher-wage jobs, first to New York City, and later to other cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston.[17] However, in more recent years, there has been a resurgence in immigration from Puerto Rico to New York and New Jersey, with an apparently multifactorial allure to Puerto Ricans, primarily for economic and cultural considerations,[18] with the Puerto Rican population of the New York City Metropolitan Area increasing from 1,177,430 in 2010 to a Census-estimated 1,201,850 in 2012,[19] maintaining its status as the largest metropolitan concentration of Puerto Ricans by a significant margin on the U.S. mainland. However, Puerto Ricans are also moving to other states in large numbers as well, and Central Florida currently is the top destination among the Puerto Rican community in the United States.

New York City

Between the 1950s and the 1980s, large numbers of Puerto Ricans migrated to New York, especially to the Bronx, and the Spanish Harlem and Loisaida neighborhoods of Manhattan. Labor recruitment was the basis of this particular community. In 1960, the number of stateside Puerto Ricans living in New York City as a whole was 88%, with most (69%) living in East Harlem.[20] They helped others settle, find work, and build communities by relying on social networks containing friends and family.

For a long time, Spanish Harlem (East Harlem) and Loisaida (Lower East Side) were the two major Puerto Rican communities in the city, but during the 1960s and 1970s predominately Puerto Rican neighborhoods started to spring up in the Bronx because of its proximity to East Harlem and in Brooklyn because of its proximity to the Lower East Side. There are significant Puerto Rican communities in all five boroughs.

Philippe Bourgois, an anthropologist who has studied Puerto Ricans in the inner city, suggests that "the Puerto Rican community has fallen victim to poverty through social marginalization due to the transformation of New York into a global city."[21] The Puerto Rican population in East Harlem and New York City as a whole remains the poorest among all migrant groups in US cities. As of 1973, about "46.2% of the Puerto Rican migrants in East Harlem were living below the federal poverty line."[22]

The struggle for legal work and affordable housing remains fairly low and the implementation of favorable public policy fairly inconsistent. New York City's Puerto Rican community contributed to the creation of hip hop music, and to many forms of Latin music including Salsa and Freestyle. Puerto Ricans in New York created their own cultural movement, and cultural institutions such as the Nuyorican Poets Cafe.

New York City also became the mecca for freestyle music in the 1980s, of which Puerto Rican singer-songwriters represented an integral component.[23] Puerto Rican influence in popular music continues in the 21st century, encompassing major artists such as Jennifer Lopez.[24]

Chicago

Puerto Ricans first arrived in the early part of the 20th century from more affluent families to study at colleges or universities. In the 1930s there was an enclave around 35th and Michigan. In the 1950s two small barrios emerged known as la Clark and La Madison just North and West of Downtown, near hotel jobs and then where the factories once stood. These communities were displaced by the city as part of their slum clearance. In 1968 a turnt around gang, the Young Lords mounted protests and demonstrations and occupied several buildings of institutions demanding that they invest in low income housing.[25]

Demographics of Stateside Puerto Ricans

Race

Half of the Puerto Rican American population is of Southern European descent, primarily descending from Spain. A large portion of the population is made up of multi-racials, especially mixed race groups such as Mulatto, Mestizo, and Tri-racial, having significant amounts of European, African, and Taino ancestry. There are a smaller number of Afro-Puerto Ricans.

"Race of Major Hispanic Groups: 2010" (PDF). Pew Hispanic Center.

| Race by Puerto Rican national Origin, 2010[26] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of Origin | White | Black | Taino | Asian | Mixed-race |

| Puerto Rico | 53.1% | 8.7% | 0.9% | 0.5% | 36.7% |

| Total: 4,623,716 | 2,455,534 | 403,372 | 42,504 | 24,312 | 1,697,944 |

Population history

In 1950, about a quarter of a million Puerto Rican natives lived "stateside," or in the United States. In March 2012 that figure had risen to about 1.5 million. That is, slightly less than a third of the 5 million Puerto Ricans living stateside were born on the island.[6][7] Puerto Ricans are also the second-largest Hispanic group in the USA after those of Mexican descent.[5]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 1,513 | — |

| 1920 | 11,811 | +680.6% |

| 1930 | 52,774 | +346.8% |

| 1940 | 69,967 | +32.6% |

| 1950 | 226,110 | +223.2% |

| 1960 | 892,513 | +294.7% |

| 1970 | 1,391,463 | +55.9% |

| 1980 | 2,014,000 | +44.7% |

| 1990 | 2,728,000 | +35.5% |

| 2000 | 3,406,178 | +24.9% |

| 2010 | 4,623,716 | +35.7% |

| Source: The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives[27] | ||

Population by state

Relative to the population of each state

The Puerto Rican population by state, showing the percentage of the state's population that identifies itself as Puerto Rican relative to the state/territory population as a whole is shown in the following table.

| State/Territory | Puerto Rican-American Population (2010 Census)[28][29] |

Percentage[note 1][30] |

|---|---|---|

| 12,225 | 0.3 | |

| 4,502 | 0.6 | |

| 34,787 | 0.5 | |

| 4,789 | 0.2 | |

| 189,945 | 0.5 | |

| 22,995 | 0.5 | |

| 252,972 | 7.1 | |

| 22,533 | 2.5 | |

| 3,129 | 0.5 | |

| 847,550 | 4.5 | |

| 71,987 | 0.7 | |

| 44,116 | 3.2 | |

| 2,910 | 0.2 | |

| 182,989 | 1.4 | |

| 30,304 | 0.5 | |

| 4,885 | 0.2 | |

| 9,247 | 0.3 | |

| 11,454 | 0.3 | |

| 11,603 | 0.3 | |

| 4,377 | 0.3 | |

| 42,572 | 0.7 | |

| 266,125 | 4.1 | |

| 37,267 | 0.4 | |

| 10,807 | 0.2 | |

| 5,888 | 0.2 | |

| 12,236 | 0.2 | |

| 1,491 | 0.2 | |

| 3,242 | 0.2 | |

| 20,664 | 0.8 | |

| 11,729 | 0.9 | |

| 434,092 | 4.9 | |

| 7,964 | 0.4 | |

| 1,070,558 | 5.5 | |

| 71,800 | 0.8 | |

| 987 | 0.1 | |

| 94,965 | 0.8 | |

| 12,223 | 0.3 | |

| 8,845 | 0.2 | |

| 366,082 | 2.9 | |

| 34,979 | 3.3 | |

| 26,493 | 0.6 | |

| 1,483 | 0.2 | |

| 21,060 | 0.3 | |

| 130,576 | 0.5 | |

| 7,182 | 0.3 | |

| 2,261 | 0.4 | |

| 73,958 | 0.9 | |

| 25,838 | 0.4 | |

| 3,701 | 0.2 | |

| 46,323 | 0.8 | |

| 1,026 | 0.2 | |

| USA | 4,623,716 | 1.5 |

The states with the highest net flow of Puerto Ricans from the island relocating there include Florida, Pennsylvania, Texas, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland. Between 2000 and 2010, these states were the major destinations for Puerto Ricans migrating from the island to the fifty states.[5] New York, remains a major destination for Puerto Rican migrants, though only a third of recent Puerto Rican arrivals went to New York.[31]

Although, Puerto Ricans constitute over 9 percent of Hispanics in the nation, there are some states where Puerto Ricans make up over half of the Hispanic population, including Connecticut where 57 percent of the state's Hispanics are of Puerto Rican descent and Pennsylvania where Puerto Ricans make up 53 percent of the Hispanics. Other states where Puerto Ricans make up a remarkably large portion of the Hispanic community include Massachusetts, where they make up 40 percent of all Hispanics, Rhode Island at 39 percent, New York at 34 percent, New Jersey at 33 percent, Delaware at 33 percent, Ohio at 27 percent, and Florida at 21 percent of all Hispanics in that state.[28][30] The U.S. States where Puerto Ricans were the largest Hispanic group were New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Hawaii.[28]

Relative to the Puerto Rican population nationwide

Puerto Rican population by state, showing the percentage of Puerto Rican residents in each state relative to the Puerto Rican population in the United States as a whole.

| State/Territory | Puerto Rican-American Population (2010 Census)[28][29] |

Percentage[note 2] |

|---|---|---|

| New York | 1,070,558 | 23.15 |

| Florida | 847,550 | 18.33 |

| New Jersey | 434,092 | 9.39 |

| Pennsylvania | 366,082 | 7.92 |

| Massachusetts | 266,125 | 5.76 |

| Connecticut | 252,972 | 5.47 |

| California | 189,945 | 4.11 |

| Illinois | 182,989 | 3.96 |

| Texas | 130,576 | 2.82 |

| Ohio | 94,965 | 2.05 |

| Virginia | 73,958 | 1.60 |

| Georgia | 71,987 | 1.56 |

| North Carolina | 71,800 | 1.55 |

| Wisconsin | 46,323 | 1.00 |

| Hawaii | 44,116 | 0.95 |

| Maryland | 42,572 | 0.92 |

| Michigan | 37,267 | 0.81 |

| Rhode Island | 34,979 | 0.76 |

| Arizona | 34,787 | 0.75 |

| Indiana | 30,304 | 0.66 |

| South Carolina | 26,493 | 0.57 |

| Washington | 25,838 | 0.56 |

| Colorado | 22,995 | 0.50 |

| Delaware | 22,533 | 0.49 |

| Tennessee | 21,060 | 0.46 |

| Nevada | 20,664 | 0.45 |

| Missouri | 12,236 | 0.27 |

| Alabama | 12,225 | 0.26 |

| Oklahoma | 12,223 | 0.26 |

| New Hampshire | 11,729 | 0.25 |

| Louisiana | 11,603 | 0.25 |

| Kentucky | 11,454 | 0.25 |

| Minnesota | 10,807 | 0.23 |

| Kansas | 9,247 | 0.20 |

| Oregon | 8,845 | 0.19 |

| New Mexico | 7,964 | 0.17 |

| Utah | 7,182 | 0.16 |

| Mississippi | 5,888 | 0.13 |

| Iowa | 4,885 | 0.11 |

| Arkansas | 4,789 | 0.10 |

| Alaska | 4,502 | 0.10 |

| Maine | 4,377 | 0.10 |

| West Virginia | 3,701 | 0.08 |

| Nebraska | 3,242 | 0.07 |

| DC | 3,129 | 0.07 |

| Idaho | 2,910 | 0.06 |

| Vermont | 2,261 | 0.05 |

| Montana | 1,491 | 0.03 |

| South Dakota | 1,483 | 0.03 |

| Wyoming | 1,026 | 0.02 |

| North Dakota | 987 | 0.02 |

| USA | 4,623,716 | 100 |

Even with such movement of Puerto Ricans from traditional to non-traditional states, the Northeast continues to dominate in both concentration and population.

The largest populations of Puerto Ricans are situated in the following metropolitan areas (Source: Census 2010):

- New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA MSA - 1,177,430

- Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL MSA - 269,781

- Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD MSA - 238,866

- Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL MSA - 207,727

- Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI MSA - 188,502

- Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL MSA - 143,886

- Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH MSA - 115,087

- Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT MSA - 102,911

- Springfield, MA MSA - 87,798

- New Haven-Milford, CT MSA - 77,578

Communities with the largest Puerto Rican populations

- New York City: 723,621 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;[28] compared to 789,172 in 2000, decrease of 65,551; representing 8.9% of the city's total population and 32% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's largest Hispanic group.

- Philadelphia: 121,643 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;[28] compared to 91,527 in 2000, increase of 30,116; representing 8.0% of the city's total population and 68% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's largest Hispanic group.

- Chicago: 102,703 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;[28] compared to 113,055 in 2000, decrease of 10,352; representing 3.8% of the city's total population and 15% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's second largest Hispanic group.

The top 25 US communities with the highest populations of Puerto Ricans (Source: Census 2010)

- New York City, NY - 723,621

- Philadelphia, PA - 121,643

- Chicago, IL - 102,703

- Springfield, MA - 50,798

- Hartford, CT - 41,995

- Newark, NJ - 35,993

- Bridgeport, CT - 31,881

- Orlando, FL - 31,201

- Boston, MA - 30,506

- Allentown, PA - 29,640

- Cleveland, OH - 29,286

- Reading, PA - 28,160

- Rochester, NY - 27,734

- Jersey City, NJ - 25,677

- Waterbury, CT - 24,947

- Milwaukee, WI - 24,672

- Tampa, FL - 24,057

- Camden, NJ - 23,759

- Worcester, MA - 23,074

- Buffalo, NY - 22,076

- New Britain, CT - 21,914

- Jacksonville, FL - 21,128

- Paterson, NJ - 21,015

- New Haven, CT - 20,505

- Yonkers, NY - 19,875

Communities with high percentages of Puerto Ricans

The top 25 US communities with the highest percentages of Puerto Ricans as a percent of total population (Source: Census 2010)

- Holyoke, MA - 44.70%

- Buenaventura Lakes, FL - 44.55%

- Azalea Park, FL - 36.50%

- Poinciana, FL - 35.82%

- Meadow Woods, FL - 35.11%

- Hartford, CT - 33.66%

- Springfield, MA - 33.19%

- Kissimmee, FL - 33.06%

- Reading, PA - 31.97%

- Camden, NJ - 30.72%

- New Britain, CT - 29.93%

- Lancaster, PA - 29.23%

- Vineland, NJ - 26.74%

- Union Park, FL - 25.81%

- Allentown, PA - 25.11%

- Windham, CT - 23.99%

- Lebanon, PA - 23.87%

- Perth Amboy, NJ - 23.79%

- Southbridge, MA - 23.08%

- Amsterdam, NY - 22.80%

- Harlem Heights, FL - 22.63%

- Waterbury, CT - 22.60%

- Lawrence, MA - 22.20%

- Dunkirk, NY - 22.14%

- Bridgeport, CT - 22.10%

The 10 large cities (over 200,000 in population) with the highest percentages of Puerto Rican residents include:[30]

- Rochester, New York: 13.2 percent

- Orlando, Florida: 13.1 percent

- Newark, New Jersey: 13.0 percent

- Jersey City, New Jersey: 10.4 percent

- New York City, New York: 8.9 percent

- Buffalo, New York: 8.4 percent

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 8.0 percent

- Cleveland, Ohio: 7.4 percent

- Tampa, Florida: 7.2 percent

- Boston, Massachusetts: 4.9 percent

Migration trends

New York was the only state to register, the reasons for and impact of these declines have yet to be fully researched. Especially in the New York case, this has been the subject of much speculation but little serious analysis to date. But it is quite clear that most of the migration was to Central Florida. Between New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago, the cities with the three largest Puerto Rican populations, Philadelphia is the only one that actually seen an increase, while the other two have seen decreases. This is probably due to Philadelphia's proximity to New York City, and its cheaper cost of living.[32] In addition, despite this decline, New York City remains a major hub for migration from Puerto Rico and within the United States.

Dispersion

Like other groups, the theme of "dispersal" has had a long history with the stateside Puerto Rican community.[33] More recent demographic developments appear at first blush as if the stateside Puerto Rican population has been dispersing in greater numbers. Duany had described this process as a “reconfiguration” and termed it the “nationalizing” of this community throughout the United States.[34]

New York City was the center of the stateside Puerto Rican community for most of the 20th century. However, it is not clear whether these settlement changes can be characterized as simple population dispersal. The fact that remains is that Puerto Rican population settlements today are less concentrated than they were in places like New York City, Chicago and a number of cities in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

Concentration

Residential segregation is a cause of stateside Puerto Rican population concentration. While blacks are the most residentially segregated group in the United States, stateside Puerto Ricans are the most segregated among US Latinos.[35][full citation needed]

- Bridgeport, Connecticut (score of 73)

- Hartford, Connecticut (70)

- New York City (69)

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (69)

- Newark, New Jersey (69)

- Cleveland-Lorain-Elyria, Ohio (68)

Stateside Puerto Ricans also find themselves concentrated in a third interesting way — they are disproportionately clustered in what has been called the "Boston-New York-Washington Corridor" along the East Coast. This area, coined a "megalopolis" by geographer Jean Gottman in 1956, is the largest and most affluent urban corridor in the world, being described as a "node of wealth ... [an] area where the pulse of the national economy beats loudest and the seats of power are well established."[36] With major world class universities clustered in Boston and stretching throughout this corridor, the economic and media power and international power politics in New York City, and the seat of the federal government in Washington, DC, this is a major global power center.

Segmentation

These shifts in the relative sizes of Latino populations have also changed the role of the stateside Puerto Rican community.[37] Thus, many long-established Puerto Rican institutions have had to revise their missions (and, in some cases, change their names) to provide services and advocacy on behalf of non-Puerto Rican Latinos. Some have seen this as a process that has made the stateside Puerto Rican community nearly invisible as immigration and a broader Latino agenda seem to have taken center stage, while others view this is a great opportunity for stateside Puerto Ricans to increase their influence and leadership role in a larger Latino world.

Socioeconomics

Income

The stateside Puerto Rican community has usually been characterized as being largely poor and part of the urban underclass in the United States. Studies and reports over the last fifty years or so have documented the high poverty status of this community.[38] However, the picture at the start of the 21st century also reveals significant socioeconomic progress and a community with a growing economic clout.[39]

The Latino market and remittances to Puerto Rico

The combined income for stateside Puerto Ricans is a significant share of the large and growing Latino market in the United States and has been attracting increased attention from the media and the corporate sector. In the last decade or so, major corporations have discovered the so-called "urban markets" of blacks and Latinos that had been neglected for so long. This has spawned a cottage industry of marketing firms, consultants and publications that specialize in the Latino market.

One important question this raises is the degree to which stateside Puerto Ricans contribute economically to Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rico Planning Board estimated that remittances totaled $66 million in 1963.[40]

The full extent of the stateside Puerto Rican community’s contributions to the economy of Puerto Rico is not known, but it is clearly significant. The role of remittances and investments by Latino immigrants to their home countries has reached a level that it has received much attention in the last few years, as countries like Mexico develop strategies to better leverage these large sums of money from their diasporas in their economic development planning.[41]

The income disparity between the stateside community and those living on the island is not as great as those of other Latin-American countries, and the direct connection between second-generation Puerto Ricans and their relatives is not as conducive to direct monetary support. Many Puerto Ricans still living in Puerto Rico also remit to family members who are living stateside.

Gender

The average income in 2002 of stateside Puerto Rican men was $36,572, while women earned an average $30,613, 83.7 percent that of the men. Compared to all Latino groups, whites, and Asians, stateside Puerto Rican women came closer to achieving parity in income to the men of their own racial-ethnic group. In addition, stateside Puerto Rican women had incomes that were 82.3 percent that of white women, while stateside Puerto Rican men had incomes that were only 64.0 percent that of white men.

Stateside Puerto Rican women were closer to income parity with white women than were women who were Dominicans (58.7 percent), Central and South Americans (68.4 percent), but they were below Cubans (86.2 percent), "other Hispanics" (87.2 percent), blacks (83.7 percent), and Asians (107.7 percent).

Stateside Puerto Rican men were in a weaker position in comparison with men from other racial-ethnic groups. They were closer to income parity to white men than men who were Dominicans (62.3 percent), and Central and South Americans (58.3 percent). Although very close to income parity with blacks (65.5 percent), stateside Puerto Rican men fell below Mexicans (68.3 percent), Cubans (75.9 percent), other Hispanics (75.1 percent), and Asians (100.7 percent).

Educational attainment

Stateside Puerto Ricans, along with other US Latinos, have experienced the long-term problem of a high school dropout rate that has resulted in relatively low educational attainment.[9]

According to the Pew Hispanic Center, while in Puerto Rico more than 20% of Hispanics have a bachelor's degree, only 16% of stateside Puerto Ricans did as of March 2012.[5]

Political participation

The Puerto Rican community has organized itself to represent its interests in stateside political institutions for close to a century.[42] In New York City, Puerto Ricans first began running for public office in the 1920s. In 1937, they elected their first government representative, Oscar Garcia Rivera, to the New York State Assembly.[43] In Massachusetts, Puerto-Rican Nelson Merced became the first Hispanic elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and the first Hispanic to hold statewide office in the commonwealth.[44]

There are four Puerto Rican members of the United States House of Representatives: Democrats Luis Gutierrez of Illinois, José Enrique Serrano of New York, and Nydia Velázquez of New York, and Republican Raúl Labrador of Idaho, complementing the one Resident Commissioner elected to that body from Puerto Rico. Puerto Ricans have also been elected as mayors in three major cities: Miami, Hartford, and Camden. Luis A. Quintana, born in Añasco, Puerto Rico, was sworn in as the first Latino mayor of Newark, New Jersey in November 2013, assuming the unexpired term of Cory Booker, who vacated the position to become a U.S. Senator from New Jersey.[45] Melissa Mark-Viverito was elected Speaker of the New York City Council in January 2014.[46]

There are various ways in which stateside Puerto Ricans have exercised their influence. These include protests, campaign contributions and lobbying, and voting. Compared to the United States, voter participation by Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico is very large.[citation needed] However, many see a paradox in that this high level of voting is not echoed stateside.[47] There, Puerto Ricans have had persistently low voter registration and turnout rates, despite the relative success they have had in electing their own to significant public offices throughout the United States.

To address this problem, the government of Puerto Rico has, since the late 1980s, launched two major voter registration campaigns to increase the level of voter participation of stateside Puerto Rican. While Puerto Ricans have traditionally been concentrated in the Northeast, coordinated Latino voter registration organizations such as the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project and the United States Hispanic Leadership Institute (based in the Midwest), have not concentrated in this region and have focused on the Mexican-American voter. The government of Puerto Rico has sought to fill this vacuum to insure that stateside Puerto Rican interests are well represented in the electoral process, recognizing that the increased political influence of stateside Puerto Ricans also benefits the island.

This low level of electoral participation is in sharp contrast with voting levels in Puerto Rico, which are much higher than that not only of this community, but also the United States as a whole.[48]

The reasons for the differences in Puerto Rican voter participation have been an object of much discussion, but relatively little scholarly research.[49]

Voter statistics

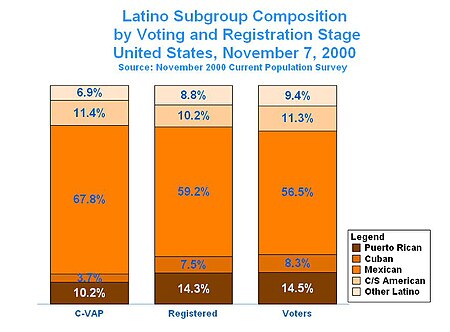

When the relationship of various factors to the turnout rates of stateside Puerto Ricans in 2000 is examined, socioeconomic status emerges as a clear factor.[50] For example, according to the Census:

- Income: the turnout rate for those with incomes less than $10,000 was 37.7 percent, while for those earning $75,000 and above, it was 76.7 percent.

- Employment: 36.5 percent of the unemployed voted, versus 51.2 percent for the employed. The rate for those outside of the labor force was 50.6 percent, probably reflecting the disproportionate role of the elderly, who generally have higher turnout rates.

- Union membership: for union members it was 51.3 percent, while for nonunion members it was 42.6 percent.

- Housing: for homeowners it was 64.0 percent, while it was 41.8 percent for renters.

There were a number of other socio-demographic characteristics where turnout differences also existed, such as:

- Age: the average age of voters was 45.3 years, compared to 38.5 years for eligible nonvoters.

- Education: those without a high school diploma had a turnout rate of 42.5 percent, while for those with a graduate degree, it was 81.0 percent.

- Birthplace: for those born stateside it was 48.9 percent, compared to 52.0 percent for those born in Puerto Rico.

- Marriage status: for those who were married it was 62.0 percent, while those who were never married managed 33.0 percent.

- Military service: for those who ever served in the US military, the turnout rate was 72.1 percent, compared to 48.6 percent for those who never served.

See also

- Teatro Puerto Rico

- Young Lords

- Puerto Rican people

- List of Puerto Ricans

- History of Puerto Rico

- Demographics of Puerto Rico

- List of Stateside Puerto Ricans

Notes

- ^ Percentage of the state population that identifies itself as Puerto Rican relative to the state/territory" population as a whole.

- ^ Percentage of Puerto Rican residents in each state relative to the Puerto Rican population in the United States as a whole. Puerto Rican population in the U.S. according to the 2010 U.S. Census: 4,623,716

References

- ^ a b US Census Bureau 2012 American Community Survey B03001 1-Year Estimates HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN retrieved September 20, 2013

- ^ Atlas of Stateside Puerto Ricans: Abridged Edition without Maps. Angelo Falcon. Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration. ca. 2002. Page 3. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ http://www.boxeomundial.com/promociones-sms-y-dibella-entertainment-firman-al-puertorriqueno-americano-christopher-golden-galeano/

- ^ Five million Puerto Ricans now living in the mainland U.S. Caribbean Business. 27 June 2013. Vol 41. Issue 24. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Puerto Rico's population exodus is all about jobs". USA Today. March 11, 2012. Cite error: The named reference "content.usatoday.com" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Puerto Ricans in the US

- ^ a b Puerto Ricans in the US

- ^ Falcón in Jennings and Rivera 1984: 15-42

- ^ a b Nieto 2000

- ^ Pantoja 2002: 93-108

- ^ Duany 2002: Ch. 7

- ^ Chenault 1938: 72

- ^ Lapp 1990

- ^ Rodríguez, Clara E. "Puerto Ricans: Immigrants and Migrants" (PDF). People of America Foundation. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ Padilla, Elena. 1992. Up From Puerto Rico. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Dávila, Arlene (2004). Barrio Dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and the Neoliberal City (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- ^ "Cleveland city, Ohio: ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006–2008". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ^ Dolores Prida (2011-06-08). "The Puerto Ricans are coming!". 2012 NYDailyNews.com. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

2012PRestwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cayo-Sexton, Patricia. 1965. Spanish Harlem: An Anatomy of Poverty. New York: Harper and Row

- ^ Bourgois, Philippe. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2003

- ^ Salas, Leonardo. "From San Juan to New York: The History of the Puerto Rican". America: History and Life. 31 (1990)

- ^ Joey Gardner. "The History of Freestyle Music". Reproduced with permission of Tommy Boy Music & Timber! Records. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ^ "López, Jennifer - Music of Puerto Rico". Copyright © 2006, Evan Bailyn, All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ^ http://www.gvsu.edu/younglords Grand Valley State University

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pewhispanic.orgwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Carmen Teresa Whalen, Víctor Vázquez-Hernández (2005). "The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives" (PDF). Temple University Press. p. 3. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "2010 Census". Medgar Evers College. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ a b US Census Bureau: Table QT-P10 Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010 retrieved January 22, 2012 - select state from drop-down menu

- ^ a b c http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF1_QTP10&prodType=table

- ^ "Puerto Rico's population exodus is all about jobs". USA Today. September 16, 2008.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ReferenceAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rivera-Batz and Santiago 1996: 131-135; Maldonado 1997 :Ch. 13; Briggs 2002: Ch. 6

- ^ Duany 2002: Ch. 9

- ^ Baker 2002: Ch. 7 and Appendix 2

- ^ Shaw 1997: 551

- ^ De Genova and Ramos-Zayas 2003

- ^ Baker 2002

- ^ Rivera-Batiz and Santiago 1996

- ^ Senior and Watkins in Cordasco and Bucchioni 1975: 162-163

- ^ DeSipio, et al. 2003

- ^ Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños 2003; Jennings and Rivera 1984

- ^ Falcón in Jennings and Rivera 1984: Ch. 2

- ^ Susan Diesenhouse (21 November 1988). "From Migrant to State House in Massachusetts". The New York Times.

- ^ Ted Sherman (November 4, 2013). "Luis Quintana sworn in as Newark's first Latino mayor, filling unexpired term of Cory Booker". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Kate Taylor (January 8, 2014). "Mark-Viverito Is Elected City Council Speaker". The New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Falcón in Heine 1983: Ch. 2; Camara-Fuertes 2004

- ^ Camara-Fuertes 2004

- ^ Falcón in Heine 1983: Ch. 2

- ^ Vargas-Ramos examines this relationship for Puerto Ricans in New York City in Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños 2003: 41-71

Bibliography

- Acosta-Belén, Edna, et al. (2000). “Adíos, Borinquen Querida”: The Puerto Rican Diaspora, Its History, and Contributions (Albany, NY: Center for Latino, Latin American and Caribbean Studies, State University of New York at Albany).

- Acosta-Belén, Edna, and Carlos E. Santiago (eds.) (2006). Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Contemporary Portrait (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers).

- Baker, Susan S. (2002). Understanding Mainland Puerto Rican Poverty (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Bell, Christopher (2003). Images of America: East Harlem (Portsmouth, NH: Arcadia).

- Bendixen & Associates (2002). Baseline Study on Mainland Puerto Rican Attitudes Toward Civic Involvement and Voting (Report prepared for the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration, March–May).

- Bourgois, Philippe. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2003

- Braschi, Giannina (1994). Empire of Dreams. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Braschi, Giannina (1998). Yo-Yo Boing! Pittsburgh: Latin American Literary Review Press.

- Briggs, Laura (2002). Reproducing Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- Camara-Fuertes, Luis Raúl (2004). The Phenomenon of Puerto Rican Voting (Gainesville: University Press of Florida).

- Cayo-Sexton, Patricia. 1965. Spanish Harlem: An Anatomy of Poverty. New York: Harper and Row

- Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños (2003), Special Issue: “Puerto Rican Politics in the United States,” Centro Journal, Vol. XV, No. 1 (Spring).

- Census Bureau (2001). The Hispanic Population (Census 2000 Brief) (Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, May).

- Census Bureau (2003). 2003 Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement: Current Population Survey, prepared by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census).

- Census Bureau (2004a). Global Population Profile: 2002 (Washington, D.C.: International Programs Center [IPC], Population Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census) (PASA HRN-P-00-97-00016-00).

- Census Bureau (2004b). Ancestry: 2000 (Census 2000 Brief) (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census).

- Chenault, Lawrence R. (1938). The Puerto Rican Migrant in New York City: A Study of Anomie (New York: Columbia University Press).

- Constantine, Consuela. “Political Economy of Puerto Rico, New York.” The Economist. 28 (1992).

- Cortés, Carlos (ed.)(1980). Regional Perspectives on the Puerto Rican Experience (New York: Arno Press).

- Cruz Báez, Ángel David, and Thomas D. Boswell (1997). Atlas Puerto Rico (Miami: Cuban American National Council).

- Christenson, Matthew (2003). Evaluating Components of International Migration: Migration Between Puerto Rico and the United States (Working Paper #64, Population Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census).

- Del Torre, Patricia (2012). "Los grandes protagonistas de Puerto Rico: Caras 2012, Editorial Televisa Publishing International: Special edition on Jennifer Lopez, Calle 13, Giannina Braschi, Ricky Martin, et al.

- Cordasco, Francesco and Eugene Bucchioni (1975). The Puerto Rican Experience: A Sociological Sourcebook (Totowa, NJ: Littlefied, Adams & Co.).

- Dávila, Arlene (2004). Barrio Dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and the Neoliberal City (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- De Genova, Nicholas and Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas (2003). Latino Crossings: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and the Politics of Race and Citizenship (New York: Routledge).

- de la Garza, Rodolfo O., and Louis DeSipio (eds) (2004). Muted Voices: Latinos and the 2000 Elections (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.).

- DeSipio, Louis, and Adrian D. Pantoja (2004). “Puerto Rican Exceptionalism? A Comparative Analysis of Puerto Rican, Mexican, Salvadoran and Dominican Transnational Civic and Political Ties” (Paper delivered at The Project for Equity Representation and Governance Conference entitled “Latino Politics: The State of the Discipline,” Bush Presidential Conference Center, Texas A&M University in College Station, TX, April 30-May 1, 2004)

- DeSipio, Louis, Harry Pachon, Rodolfo de la Garza, and Jongho Lee (2003). Immigrant Politics at Home and Abroad: How Latino Immigrants Engage the Politics of Their Home Communities and the United States (Los Angeles: Tomás Rivera Policy Institute)

- Duany, Jorge (2002). The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press).

- Falcón, Angelo (2004). Atlas of Stateside Puerto Ricans (Washington, DC: Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration).

- Puerto Ricans: Thirty Years of Progress & Struggle, Puerto Rican Heritage Month 2006 Calendar Journal (New York: Comite Noviembre). (2006).

- Fears, Darry (2004). "Political Map in Florida Is Changing: Puerto Ricans Affect Latino Vote," Washington Post (Sunday, July 11, 2004): A1.

- Fitzpatrick, Joseph P. (1996). The Stranger Is Our Own: Reflections on the Journey of Puerto Rican Migrants (Kansas City: Sheed & Ward).

- Gottmann, Jean (1957). “Megalopolis or the Urbanization of the Northeastern Seaboard,” Economic Geography, Vol. 33, No. 3 (July): 189-200.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón (2003). Colonial Subjects: Puerto Ricans in a Global Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- Haslip-Viera, Gabriel, Angelo Falcón, and Felix Matos-Rodríguez (eds) (2004). Boricuas in Gotham: Puerto Ricans in the Making of Modern New York City, 1945-2000 (Princeton: Marcus Weiner Publishers).

- Heine, Jorge (ed.) (1983). Time for Decision: The United States and Puerto Rico (Lanham, MD: The North-South Publishing Co.).

- Hernández, Carmen Dolores (1997). Puerto Rican Voices in English: Interviews with Writers (Westport, CT: Praeger).

- Jennings, James, and Monte Rivera (eds) (1984). Puerto Rican Politics in Urban America (Westport: Greenwood Press).

- Lapp, Michael (1990). Managing Migration: The Migration Division of Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1948-1968 (Doctoral Dissertation: Johns Hopkins University).

- Maldonado, A.W. (1997). Teodoro Moscoso and Puerto Rico’s Operation Bootstrap (Gainesville: University Press of Florida).

- Mencher, Joan. 1989. Growing Up in Eastville, a Barrio of New York. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Meyer, Gerald. (1989). Vito Marcantonio: Radical Politician 1902-1954 (Albany: State University of New York Press).

- Mills, C. Wright, Clarence Senior, and Rose Kohn Goldsen (1950). The Puerto Rican Journey: New York's Newest Migrants (New York: Harper & Brothers).

- Moreno Vega, Marta (2004). When the Spirits Dance Mambo: Growing Up Nuyorican in El Barrio (New York: Three Rivers Press).

- Nathan, Debbie (2004). “Adios, Nueva York,” City Limits (September/October 2004).

- Negrón-Muntaner, Frances (2004). Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture (New York: New York University Press).

- Negrón-Muntaner, Frances and Ramón Grosfoguel (eds) (1997). Puerto Rican Jam: Essays on Culture and Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

- Nieto, Sonia (ed.) (2000). Puerto Rican Students in U.S. Schools (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates).

- Padilla, Elena. 1992. Up From Puerto Rico. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pérez, Gina M. (2004). The Near Northwest Side Story: Migration, Displacement, & Puerto Rican Families (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- Pérez y González, María (2000). Puerto Ricans in the United States (Westport: Greenwood Press).

- Ramos-Zayas, Ana Y. (2003). National Performances: The Politics of Class, Race, and Space in Puerto Rican Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

- Ribes Tovar, Federico (1970). Handbook of the Puerto Rican Community (New York: Plus Ultra Educational Publishers).

- Rivera Ramos. Efrén (2001). The Legal Construction of Identity: The Judicial and Social Legacy of American Colonialism in Puerto Rico (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association).

- Rivera-Batiz, Francisco L., and Carlos E. Santiago (1996). Island Paradox: Puerto Rico in the 1990s (New York: Russell Sage Foundation).

- Rodriguez, Clara E. (1989). Puerto Ricans: Born in the U.S.A. (Boston: Unwin Hyman).

- Rodríguez, Clara E. (2000). Changing Race: Latinos, the Census, and the History of Ethnicity in the United States (New York: New York University Press).

- Rodríguez, Victor M. (2005). Latino Politics in the United States: Race, Ethnicity, Class and Gender in the Mexican American and Puerto Rican Experience (Dubuque, IW: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company) (Includes a CD)

- Safa, Helen. "The Urban Poor of Puerto Rico: A Study in Development and Inequality". Anthropology Today 24 (1990): 12-91.

- Salas, Leonardo. "From San Juan to New York: The History of the Puerto Rican". America: History and Life. 31 (1990).

- Sánchez González, Lisa (2001). Boricua Literature: A Literary History of the Puerto Rican Diaspora (New York: New York University Press).

- Shaw, Wendy (1997). “The Spatial Concentration of Affluence in the United States,” The Geographical Review 87 (October): 546-553.

- Torres, Andres. (1995). Between Melting Pot and Mosaic: African Americans and Puerto Ricans in the New York Political Economy (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Torres, Andrés and José E. Velázquez (eds) (1998). The Puerto Rican Movement: Voices from the Diaspora (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Vargas and Vatajs -Ramos, Carlos. (2006). Settlement Patterns and Residential Segregation of Puerto Ricans in the United States, Policy Report, Vol. 1, No. 2 (New York: Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, Fall).

- Wakefield, Dan. Island in the City: The World of Spanish Harlem. New York: Houghton Mifflin. 1971. Ch. 2. pp. 42–60.

- Whalen, Carmen Teresa (2001). From Puerto Rico to Philadelphia: Puerto Rican Workers and Postwar Economics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Whalen, Carmen Teresa, and Víctor Vázquez-Hernández (eds.) (2006). The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).