Croatian art

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2010) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Croatia |

|---|

|

| People |

| Mythology |

| Sport |

Croatian art describes the visual arts in Croatia from medieval times to the present. In Early Middle Ages, Croatia was an important centre for art and architecture in south eastern Europe. There were many Croatian artists during the Medieval period, and the arts flourished during the Renaissance. Later styles in Croatia included Baroque and Rococo.

Ancient heritage

Prehistoric art

Ancient monuments from Palaeolithic times are very poor and consist mainly of simple stone and bone objects.

Ancient inhabitants of Mediterranean cultures on the Adriatic Coast and those of Pannonian cultures in the continental area of the present-day Republic of Croatia, were developing Neolithic cultures in the boundaries of present-day Republic of Croatia. The Neolithic is marked by the production of ceramics and sculptures with human and animal themes presented as symbolic art. The most investigated are listed chronologically:

- Starčević culture (Pannonian culture named after its founder archaeologist Starčević) had characteristically fine red and ochre ceramics.

- Istrian culture (named after peninsula Istria in Croatia) which characteristic is stone houses (Bunja) without any type of bonding material, natively called dry-wall building (suhozid). These types of houses have stayed in use until the 19th century for shepherds.

- Sopot culture and Korenovo culture (named after towns of Sopot and Korenovo in Slavonia) with original ceramic pots decorated with flat parallel lines, curves or V-shaped cuts.

- Danilo culture (found on Adriatic coast and islands) was rich with fine dark ceramics decorated with engraved geometrical motifs, spirals and meanders. *Danilo culture (found on Adriatic Coast and Islands) was rich with fine dark ceramics decorated with engraved geometrical motifs, spirals and meanders. Out of this culture developed the Hvar culture (after large island of Hvar) that is linked with Neolithic Greek cultures.

There are also Neolithic excavation sites in Ščitarjevo near Zagreb, Nakovanj on the Pelješac peninsula and elsewhere.

Copper Age

One of the most unusual Copper Age or Eneolithic finds is from the Vučedol culture (named after Vučedol near Vukovar). Ceramics are of extraordinary quality with black color, high glow and specific decorative geometrical cuts that were encrusted with white, red or yellow color. Few sculptures have been found. They are very skilfully and expressively done (like the pot in shape of Dove with engraved double axe – labrys). People lived on hilltops with palisade walls. Houses were half buried, mostly square or circular (they were also combined in mushroom shape), with a floor of burned clay and circular fireplace.

Bronze Age

Out of that culture emerged Bronze Age Vinkovci culture (named after the city of Vinkovci) that is recognizable by bronze fibulas that were replacing objects like needles and buttons.

The Bronze culture of the Illyrians, ethno-tribal groups with distinct cultures, and art forms started to emerge from the cultures of the Copper Age. These Illyrian ethno-tribal areas were found in present-day Croatia, and Bosna and Hercegovina. From the 7th Century BC, iron replaced bronze and only jewelry and art objects were still made out of bronze. The Celtic Halstat culture which bordered the Balkan region where the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups were living influenced them, but the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups formed their regional centers slightly differently. In the northern Balkan Peninsula, the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups had the cult of the dead, as evidenced from the richness of and care for burial sites, from which burial ceremonies are deduced. These burial sites show a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves. In the southern Balkan Peninsula, the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups buried their dead are in large stone, or earth tumuli (natively called – gromile). Illyrian Japod tribes had an affinity for decoration with heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste. The Illyrian Japod tribes also had affinities for large bronze fibulas, spiral bracelets, diadems, and helmets made out of bronze. Small sculptures made of jade made from the archaic Ionian plastic are also found in Japodian tribal areas. Numerous monumental sculptures are preserved, as well as walls of a citadel called Nezakcij near present-day Pula, one of the numerous Istrian cities from Iron Age.

Celtic Entrance to Balkan Peninsula

In the 4th century BC, the first emergence Celts into the Illyrian ethno-tribal areas of the Balkans is recorded; they brought the technique of the pottery wheel, new types of fibulas and different bronze and iron belts, which the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups had not independently developed. The Celts also mixed with the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups in Slavonia, Istria, and Dalmatia. They passed through Greece burning several Greek Polis on their way to settling in Asia Minor (Anatolia) where they remained to be addressed by Saint Paul in his Epistle to the Galatians.

The Greco-Illyrians & Roman Conquest

In the Neretva Delta in the South, there was the important influence of Hellenistic Greco-Illyrian tribe of the Daors. Illyrian tribes conquered Greek colonies on Dalmatian islands. The Queen Teuta of Issa (Today Issa island is known as the island of Vis.) is famous because she waged wars with Romans. But finally, Romans subdued Illyrians ethno-tribal groups in the 1st Century BC. After that, these Illyrian provinces became parts of Rome and New Rome (Byzantium).[1]

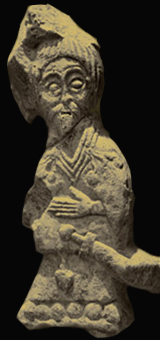

Antiquity

Greek sailors and merchants from the Greek City States of the south of the Balkan peninsula reached almost every part of Mediterranean including the Adriatic Sea coast of present-day Croatia. Greeks also came from Syracuse on Sicily in 390 BC to the islands of Vis (Issa), Hvar (Pharos), and Korčula (Corcyra Nigra) thereby founding city-states amongst the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups. Greek trade cities on the Adriatic Coast such as Tragurion (today called Trogir), Salona (today called Solin near present-day Split), Epetion (today called Stobreč), Issa (today called Vis), were geometrically shaped and had villas, harbours, public buildings, temples and theatres. Pharos and Issa were strong Greek City States that showed their independence with their own coinage and maritime fleets. Unfortunately, besides painted pots and ceramic tanagra sculptures, there are few daily living materials remaining of this culture. Two of those are: the Croatian Apoxyomenos, and the Bronze head of goddess Artemis from the Greek City State of Issa, which dates from the 4th century BC. Another example is a stone relief of Kairos (god of joyfulness) from the Greek City-State Tragurion, which dates from the 3rd Century BC, and is associated with the famous Greek sculptor Lysippos.

While the Greek colonies were flourishing on the Adriatic Coast and Islands, on the mainland the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups were organizing their centers. Illyrian ethno-tribal art became greatly influenced by Greek Art, and the Illyrian ethno-tribal groups copied some Greek Art.[2]

Romans[3] subdued Greek colonial cities in the 3rd century BC. They have imposed organization based on the military-economical system. Furthermore, Romans subdued Illyrians in the 1st century BC and organized the entire coastal territory by transforming citadels into urban cities. After that the history of these parts is a history of Illyrian provinces of Roman Empire.

Numerous rustic villas, and new urban settlements (the most impressive are Verige in Brijuni, Pula and Trogir - formerly Tragurion) demonstrate high level of Roman urbanization. There have been at least thirty urban cities in Istria, Liburnia and Dalmatia with Roman citizenship (civitas). The best-preserved nets of Roman streets (decumanus/cardo) are those in Epetion (Poreč) and Jader (Zadar).

The most entirely preserved Roman monuments are in Pola (Pula); founded in the 1st century dedicated to Julius Caesar, it is full with classical Roman art as: stonewalls, two city gates, two temples on Forum, and remains of two theatres, as well as the Arch from year 30 AD, and the temple of August build in years 2 to 14 AD, and finally the Fluvian Amphitheatre (so called – Arena) from the 2nd century.

In the 3rd century AD, the city of Salona becomes the largest (it had 40,000 inhabitants) and the most important city of Dalmatia. Near the city emperor Diocletian, born in Salona, build the Palace (around year 300 AD), which is largest and most important monument of late antique architecture in the World. On its pathways, cellars, domes, mausoleums, arcades and courtyards one can trace numerous different art influences from the entire Empire.

Some of the sculptures are: the head of a boy, girl and a woman from Salona, monumental figure of Minerva from Varaždin, the head of Hercules from Sinj, sculptures of Roman emperors from Nin and Vid near Metković, damaged sculpture of emperor in Zagreb Museum etc.

In the 4th century Salona became the center of Christianity for entire western Balkans. It had numerous basilicas and necropolises, and even two saints: Domnius (Duje) and Anastasius (Staš).

One of few preserved basilicas in western Europe (besides ones in Ravenna) from the time of early Byzantium is Euphrasian Basilica in Poreč from the 6th century.

The early Middle Ages brought the great migration of the Slavs and this period was perhaps a Dark Age in the cultural sense until the successful formation of the Slavic states which coexisted with Italic cities that remained on the coast, each of them were modelled like Venice.

-

The arena in Pula

-

4th-century Praxitelean bronze head of a goddess wearing a lunate crown, found at Issa (Vis, Croatia)

-

Vučedol Dove, the symbol of the Vučedol culture.

Medieval Croatian art

Early Middle Ages

The term Middle Ages,[4] in Western Europe, designates the period following the decline of the Roman Empire through the 13th century. Early Middle Ages[5] (Pre-Romanesque) covers the time from 7th to the end of the 10th century.

In the 7th century the Croats, with other Slavs and Avars, came from Northern Europe to the region where they live today.[6] They were on the level of Iron Age nomadic culture, so they did not know how to enjoy the advantages of urban cities. the country side around Roman cities rivers (like Jadro near Roman Salona).[7]

The Croats were open to Roman art and culture, and first of all to Christianity. First churches were built as royal sanctuaries, and influences of Roman art was strongest in Dalmatia where urbanization was thickest, and there was the largest number of monuments. Gradually that influence was neglected and certain simplification, alteration of inherited forms and even creation of original buildings appeared. All of them (dozen large ones and hundreds of small ones) were built with roughly cut stone (natively called – lomljenac) bounded with a thick layer of "malter" from outside. Large churches are longitudinal with one or three naves like the Church of Holy Salvation on spring of river Cetina and the Church of Saint Cross near Nin, both built in the 9th century. The latter has strong semi-circular buttresses that give a feeling of fortification, emphasizing the bell-tower positioned in front of the entrance.

Smaller churches are unusually shaped (mainly central) with several apses. The largest and most complicated central based church from the 9th century is St Donatus in Zadar. Around its circular center – with dome above – is nave in shape of a ring with three apses directed to the east; that shape is followed on the second floor forming a gallery. From those times, with its size and beauty one can only compare the chapel of Charlemagne in Aachen.

Altar fence and windows of those churches were highly decorated with transparent shallow string-like ornament that is called pleter - Croatian interlace - because the strings were threaded and rethreaded through themselves.

Motifs of those reliefs were taken from Roman art (waves, three-string interlace, pentagrams, net of rhomboids etc.), but while in the Roman art they only made the frame of a sculpture in Dark Ages it fills entire surface. Those reliefs were vividly colored (red, blue and yellow), and because the paintings from that period are not preserved (it is known they existed because they were mentioned in written sources as liturgical from Split, 8th-11th centuries), they remain the only remains of old-Croatian painting.

Sometimes the figures from Bible appeared alongside this decoration, like relief in Holy Nedjeljica in Zadar, and then they were subdued by their pattern. That happened to engravings in early Croatian script – Glagolitic.

Soon, the "Glagolitic" writing was replaced with Latin on altar fences and architraves of old-Croatian churches. Those inscriptions usually mention to whom the church was dedicated, who build it and when it was built, as well who produced the building. That was the way that "barbarian newcomers" could fit amongst the Romanised natives.

From Crown Church of King Zvonimir (so-called Hollow Church in Solin) comes to the altar board with the figure of the Croatian King on the throne with Carolingian crown, servant by his side and subject bowed to the king. Linear cuts representing lines on the robes are similar to lines on their frontal faces, and also on those of a frame. Today the board is a part of Split cathedral baptistery.

Out of artistically applied objects, there are many reliquaries preserved.[8] They were adored and believed to have magical powers of healing. They were usually shaped as the part of body that was in them.[9] That's why the relic of Saint James's head in Zadar is shaped in form of a head; the tube part has section with stream of arcades with single saint in every one, while a dome-like cover is decorated with medallions bearing symbols of evangelist and Christ on the top.

By uniting with the Kingdom of Hungary in the 12th century, Croatia lost its independence, but it did not lose its ties with the south and the west, and instead, this ensured the beginning of a new era of Central European cultural influence.

Romanesque art

Early Romanesque art appeared in Croatia at the beginning of the 11th century with the strong development of monasteries and reform of the church. In that period many valuable monuments and artifacts were made. They can be found mainly alongside Croatian coast and nearby lands: Istria, Dalmatia, and Primorje; while artifacts and monuments from Croatian north are scarce.

In the 11th century, the monumental cities were built along the entire Dalmatian coast. Houses were out of stone, on ground floor there were shops or dinners (natively – konoba) like in cities as: Poreč, Rab, Zadar, Trogir and Split. In them the most important buildings were churches. They were commonly stone-built basilicas with three naves, three apses, columns, arches, arcades and wooden roofs; build near monasteries of Benedictian monks who came out of Italy. St. Peter in Supetarska Draga on the island of Rab (11th century) is the best-preserved church of that type in Croatia. On the same island is Cathedral of Rab (12th century) that has high-Romanesque bell tower, largest in Dalmatia. It is specific with its openings, which are multiplied as one goes higher floor by floor (Latin: mono-fore, bi-fore, tri-fore, quadro-fore); typical for Romanesque, but also architecturally smart because it makes every next floor a bit lighter than the preceding one.

Cathedral of St. Anastasia, Zadar (natively - St. Stošija) in Zadar (13th century) is marked outside by a string of blind arch-niches on both sides and on frontal side where it also has two Rose windows with radial columns and three portals. Inside it has three naves, slim columns that are supporting a gallery, and flat figurative reliefs.

In Croatian Romanesque sculpture, there was a transformation of decorative interlace relief (natively – pleter) to figurative, which is found on stone ceilings. At the end of the Romanesque period, in Istria, there were workshops of monumental figures. They had geometrical and naturalistic features reminiscent of gothic. The best examples of Romanesque sculpture are the wooden doors of the Split cathedral done by Andrija Buvina (c. 1220) and the stone portal of the Trogir cathedral done by artisan Radovan (c. 1240). the

Main portal of Trogir cathedral, done by artisan Radovan, is the greatest and the most important monument of medieval sculpture in Croatia. It consists out of four parts: surrounding, on doorjamb, are naked sculptures of Adam and Eve on both sides, carried by lions; and inside are numerous reliefs with every-day scenes organized in monthly calendar, and scenes from hunting; and finally in the middle are scenes from the life of Christ: from Annunciation to Resurrection – positioned in arches around tympanum. Finally, in tympanum is the Birth of Christ. The way the figures are formed is very realistic, calling on new gothic humanism, on the trail of the highest achievements of French sculpture (of that in Chartres). Radovan is oriented toward human counterpart in art; best seen in selection of main scene in the tympanum – instead of the usual Romanesque motif of Last Judgement he had chosen The Nativity.

Romanesque painting is on walls, on board and in books – illumination. Early frescoes are numerous and best preserved in Istria. The mixing of influences of Eastern and Western Europe is evidenced on them, for example, flat, linear drapes and round red circles on their cheeks. Paintings on board are usually Madonna with Child and painted Crucifixions. The oldest miniatures are from the 13th century – Evangelical book from Split and Trogir.

Gothic art

The Gothic art in the 14th century was supported by a culture of city councils, preaching orders (like Franciscans), and knightly culture. It was the golden age of free Dalmatian cities that were trading with Croatian feudal nobility in the continent. Urban organization and evolution of Dalmatian cities can be followed through the continued development and expansion of Rab and Trogir, the regulation of streets in Dubrovnik, and the integration of Split. It was also when streets in this region were paved with stone, sewage canals were re-developed (the Byzantine Empire retained flushing toilettes, whereas this technology was lost in Roman Catholic Europe), and communal facilities were re-established.

The largest urban project of those times in Dalmatia was the complete design of two new towns – Small and Large Ston. The most important feature of those towns was a city wall which was about a kilometer of wall with guard towers along the walls built in the 14th Century. Hadrian's wall in Scotland is the longest wall in Europe, and these walls are of similar importance in the Balkans. With these walls the entire Pelješac Peninsula was surrounded and protected from the Adriatic Coast and from the landward part of the cities with an aim to protect the most valuable possession of the Republic of Dubrovnik – salt from Ston.

Gothic fortification can be differentiated by its high towers in the shape of a square prism from simple Romanesque ones or round Renaissance ones. The best-preserved ones in Croatia are Istria (Hum, Bale, Motovun, Labin etc.) and those on north (Medvedgrad above Zagreb from year 1260) or on the south Sokolac in Lika (14th century).

Franciscan church in Pula built in 1285, is the most representative example of Early Gothic architecture in Croatia. Simple one-nave building with the wooden rib-vault ceiling, with square apse and high stained glass windows, was built from the 13th to 15th centuries.

Tatars destroyed Romanesque cathedral in Zagreb during their scourge in 1240, but right after their departure, Zagreb received the title of Free City (Freistadt Zagreb) from King Béla IV. Soon after bishop Timotej began to rebuild the cathedral in new Gothic style. Building with three naves, polygonal apses and rib-vault had Romanesque round towers. The naves were built in the 14th century, and the vault was finished in the 15th. With the arrival of Turks in the 16th century, high walls and towers surrounded it. Only one tower was finished in the 17th century, while in the 18th the Baroque roof became the landmark of the entire city. With the restoration in the 19th century in Neo-Gothic style it lost its former harmony.

During the 14th century, the Split cathedral of St Duje and cloister of Franciscan monastery in Dubrovnik were also built. Early Gothic sculpture is represented by already mentioned Radovan's Portal in Trogir.

The Church of St Mark in Zagreb was built in 14th and 15th centuries in Late Gothic style. In that manner was also the main portal with portraits of St Mark, Christ, Madonna and 12 apostles with slightly rounded heads and softly drapes on their clothes. Originally the entire portal was vividly colored as can be seen by the remains of colors on wooden figures.

In those days, Zadar was a Venetian city. The most beautiful examples of Gothic humanism in Zadar are reliefs in gilded metal as in Arc of St Simon by an artisan from Milan in 1380. On the arc, by the scenes of saints' life (finding of the body in monastery's cluster, saving the ship in storm etc.) there are historical ones as entering of King Ludovik in Zadar or the oath of his wife Elizabeth of Bosnia over the saints' grave.

Gothic painting is less preserved, and finest works are in Istria as fresco-cycle of Vincent from Kastv in Church of Holy Mary in Škriljinah near Beram, from 1474. Characters are tangible, three-dimensional in the illusion of space. By the scenes from the life of Christ there is also The March of the Dead (The Dance of Death), which is humanistic, late gothic theme, very popular in Renaissance.

Paolo Veneziano was the greatest painter of the Adriatic in the 14th century. His works were mixture of Byzantine iconography and Gothic idealisation. He worked on the icons in Krk, Rab, Zadar, and Trogir. In Dubrovnik, he has done a masterpiece - Dubrovnik Crucifixion.

From that times are the two of the best and most decorated illuminated liturgies done by monks from Split, – Hvals' Zbornik (today in Zagreb) and Misal of Bosnian duke Hrvoje Vukčić Hrvatinić (now in Istanbul).

Renaissance

In the late 16th - 17th century, Croatia was divided between three states – northern Croatia was a part of the Habsburg monarchy, Dalmatia was under the rule of Venetian Republic (with exception of Dubrovnik) and Slavonia was under Ottoman occupation. Dalmatia was on the periphery of several influences, just as far from Italy as from Ottomans in Bosnia and Austrians in the north, so it thrived from all. In those circumstances in Dalmatia flourished religious and public architecture with a clear influence of Italian renaissance, but still original. Three works out of that period are of European importance, and will contribute to further development of Renaissance: Šibenik Cathedral of St James, Chapel of Blessed John in Trogir, and Sorkočević's villa in Dubrovnik.

Only in the kind of environment, free of dogmas and self-governed - far of major governing centers, could it be possible for artisan known as Juraj Dalmatinac to build a church entirely by his own project – Šibenik Cathedral of St James, in 1441. Besides mixing Gothic and Renaissance style it was also original because it used stone and montage construction. What these terms mean is that big stone blocks, pilasters, and ribs were bounded by joints with slots on them without concrete in the way that was usual in wooden constructions. This was unique architecture with the so-called three-leaf frontal and half-barrel vaults, the first in Europe. The cathedral and its original stone dome was finished by Nikola Firentinac following the original plans of Juraj. On the cathedral, there is a coronal of 72 sculpture portraits on the outside wall of the apses. Juraj himself did 40 of them, and all are unique with original characteristics on their faces.

Work on Šibenik cathedral inspired Nicola for his work on the expansion of the Chapel of Blessed John of Trogir in 1468. Just like Šibenik cathedral, it was composed out of large stone blocks with extreme precision. In cooperation with the student of Juraj Dalmatinac, Andrija Aleši, Nicola has achieved unique harmony of architecture and sculpture according to antique ideals. From inside, there is no flat wall. In the middle of the chapel, on the altar, lies the sarcophagus of blessed John of Trogir. Surrounding are reliefs of putti carrying torches that look like they are peeping out of doors of the Underworld. Above them there are niches with sculptures of Christ and apostles, among them are more putti, circular windows encircled with fruit garland, and a relief of the Nativity. The ceiling is coffered, with the image of God in the middle and 96 portrait heads of angels.

In the entire area of Republic of Dubrovnik there were numerous villas of nobility, due to their functionality and organization as combinations of renaissance villa and government building. Sorkočević's villa in Lapad near Dubrovnik in 1521 is original because of building parts in asymmetrical, dynamic balance.

Renaissance sculptures are linked to some architecture, and the most beautiful one is perhaps relief Flagellation of Christ by Juraj Dalmatinac on the altar of St Staš in Split cathedral. Three almost naked figures are caught in vibrant movement.

The most important renaissance painters from Dubrovnik are: Lovro Dobričević, Mihajlo Hamzić and Nikola Božidarević. They painted the altar screens with first hints of portraits in characters, linear perspective and even still life motifs.

In Northwestern Croatia, the beginning of the wars with the Ottoman Empire caused many problems but in the long term, it both reinforced the northern of the ruling Habsburgs. There was the modest influence of the Renaissance in styles of fortification. The plan for the fortified city of Karlovac in 1579 was the first radially built city in the Balkan Peninsula using the so-called "ideal city" plan like is found afterward in Renaissance and Baroque Europe (See Baroque). The Muslim Turk Ottomans were a constant threat from the South and East and hindered the over-all development of Serbo-Croatian expression in the region.

The renaissance fort of the Ratkay family in Veliki Tabor from the 16th century has mixed features of Gothic architecture (high roofs) and renaissance (cluster and round towers) making it an example of Mannerism. Some of the famous renaissance artists that lived and worked in other countries, like brothers Laurana (In Croatian - Vranjanin, Franjo and Luka), miniaturist Juraj Klović and famous mannerist painter Andrija Medulić (teacher of El Greco).

Baroque and Rococo

In the 17th and 18th century Croatia was reunited with the parts of the country that were occupied by Venetian Republic and Ottoman Empire. The unity attributed to the sudden flourishing of art in every segment. In northern Croatia and Slavonia sprung out numerous and worthy works of Baroque art – from urban plans and large forts to churches, palaces, public buildings and monuments, all were done in Baroque style.

Large fortifications with a radial plan, ditches and numerous towers were built because of constant Ottoman threat. The two largest ones were Osijek and Slavonski Brod. Later they become large cities. They were fortified with water and earth – earth mounds with cannons and canals filled with water that was supposed to slow down the approaching enemies. The fort of Slavonski Brod was the largest in all Croatia, and one of the largest ones in entire Europe because it was bounding fort of Europe toward Ottoman Empire.

Urban planning of Baroque is felt in numerous new towns like Karlovac, Bjelovar, Koprivnica, Virovitica etc. that had large straight streets, rectangular squares in the middle surrounded with buildings as government and military ones as well as representative church.

Cities of Dalmatia also got baroque towers and bastions incorporated in their old walls, like the ones in Pula, Šibenik or Hvar. But biggest Baroque undertaking happened in Dubrovnik in the 17th century after the catastrophic earthquake in 1667 when the almost entire city was destroyed. In Baroque style were rebuilt the church of St Vlaho on the main square (1715), Main Cathedral and Jesuit college with church of St Ignatius. Paolo Passalaqua united several of those baroque masterpieces with his Jesuit Stairway. That beautiful wide stone stairway with series of convexities and concavities and strong balustrade (reminiscent of famous Spain Stairway Square in Rome) actually connected two separate baroque parts of the city - the Jesuit church above and Ivan Gundulić Square below.

During the Baroque numerous churches, enchanting us with their size and form were built in all Croatia, thus becoming a crown in every town or a city. The monastery churches often had an enclosing wall with inner porches lavishly decorated, like in Franciscan monastery in Slavonski Brod where the columns are as thick as baroque abundance. The most beautiful one is probably the church in Selima near Sisak. It has an oval shape with elliptic dome and concave and convex front with two according to towers. But most luxuriant is the church of Maria of the Snow in Belec from 1740 with the entire interior filled with lively gilded wooden sculptures, frescoes of painter Ivan Ranger from Austria. Ranger was classic Rococo painter whose characters were softly painted in graceful positions and optimism of cheerful colors. He also lavishly painted the gothic church in Lepoglava, and ceiling of Banqueting Hall of Bistra Palace (one of most beautiful elliptic plans in profane architecture).

Wall painting experienced flourishing in all parts of Croatia, from illusionist frescoes in church of Holy Mary in Samobor, St Catherine in Zagreb to Jesuit church in Dubrovnik. Best preserved ones are Rococo frescoes in Miljana mansion where allegorical seasons and natural elements were depicted through human nature and his reflection on art.

Baroque towers and bastions were incorporated into the old walls of Dalmatian cities, like the ones in Pula, Šibenik or Hvar. The biggest Baroque undertaking in Dalmatia happened in Dubrovnik in the 17th Century after the catastrophic earthquake of 1667 when almost the entire city was destroyed. In Baroque style were rebuilt Church of St Vlaho on the main square in 1715, the Catholic Main Cathedral, as well as the Jesuit college and its accompanying church of St Ignatius. Paolo Passalaqua united several of those baroque masterpieces with his Jesuit Stairway. The wide stone stairway was built with a series of convexities, concavities and a strong balustrade (reminiscent of famous Spain Stairway Square in Rome) thereby connecting two parts of the city, using Baroque style, which were the Jesuit church above and the Ivan Gundulić Square below. During the Baroque numerous Catholic churches crowned most towns in cities due to their large size and opulence. The Roman Catholic monastery churches often had an enclosing wall with inner porches lavishly decorated, like in the Franciscan monastery in Slavonski Brod where the columns are thick showing baroque abundance. The most beautiful one is probably the Roman Catholic church in Selima near Sisak. It has an oval shape with an elliptic dome and concave and convex front with two towers. In a very luxuriant Roman Catholic church, Maria of the Snow in Belec from 1740 the entire interior is filled with lively gilded wooden sculptures, frescoes by painter Ivan Ranger from the Roman Catholic Habsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire. Ranger was a classic Rococo painter whose characters were softly painted in graceful positions with optimism and cheerful colors. He also lavishly painted the Roman Catholic Gothic church in Lepoglava, and the ceiling of the Banqueting Hall of Bistra Palace which is one of most beautiful elliptic plans in profane architecture.

An exchange of artists between Croatia and other parts of Europe happened. The most famous Croatian painter was Federiko Benković who worked almost his entire life in Italy, while an Italian – Francesco Robba, did the best Baroque sculptures in Croatia. His most beautiful and moving work is marble altar of Crucifixion in Church of Holy Cross in Križevci. Beside masterly carved body of Christ, there is a theme of Abraham's Sacrifice; it is a diagonal composition in anxious tension with several movements of limbs and drapes. Located beside the master marble work of the body of Christ there is a theme of Abraham's Sacrifice of Isaac. The Sacrifice of Isaac is portrayed in a diagonal composition with anxious tension articulated by several movements of limbs and drapes.

The 19th century

In Austrian countries on the beginning of the 19th century (to which Croatia belonged than) building in Classicistic Manner prevailed. In Croatia most prominent architect was Bartol Felbinger who also built City Hall in Samobor (1826) and Januševac Castle near Zagreb.

Romantic movement in Croatia was sentimental, gentle and subtle – the real image of bourgeoisie's humble and modest virtues. In architecture, there were simple decorations made of the shallow arch like niches around windows, while the furniture was of mildly bent Biedermeier furniture, and even in dressing the cheaper materials with cheerful colors prevailed. So, it is no surprise that instead of representative portraits in Croatia miniature portraits are preferred.

At the end of the 19th century, architect Hermann Bolle undertook one of the largest projects of European historicism – a half-kilometer-long neo-renaissance arcade with twenty domes on Zagreb cemetery Mirogoj.

At the same time, the cities in Croatia got an important urban makeover. But for size and importance, the urban regulation of Downtown Zagreb (largely the work of Milan Lenuzzio, 1860–1880) was revolutionary. Between Zagreb's longest street – Ilica, and new railway the new geometrical city was built with large public and social buildings like neo-renaissance building of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (HAZU - learned society promoting language, culture, and science from its first conception in 1836; the juxtaposition of the words typically seen in English as "Arts and Sciences" is deliberate, F. Scmidt, 1884), neo-baroque Croatian National Theatre (HNK, H. Helmer and F. Fellner, 1895), and to that date very modern Art Pavilion (1898) with montage construction of steel and glass – Croatian "Crystal Palace", and finally the masterpiece of Art Nouveau – The National Library (Lubinski, finished in 1912). This urban plan is bounded by series of parks and parkways decorated with numerous fountains, sculptures, avenues and gardens (known as "Green Horseshoe") making Zagreb one of the first cities built according to new European art theory of "city as a work of art".

The pseudo building that emphasizes all three visual arts is the former building of Ministry of Prayer and Education in Zagreb (H. Bolle, 1895). Along with rooms in Pompeii style and renaissance cabinet, the large neo-baroque "Golden Hall" was painted with historic compositions by Bela Čikoš-Sesija (The Baptism of Croats and Split Council), Oton Iveković (Meeting of Koloman and Croatian Nobility), Mato Celestin Medović (The Arrival of Croats), Vlaho Bukovac (Frantz Joseph in Zagreb) and decorated with reliefs by Robert Frangeš-Mihanović. "The Golden Hall" becomes a unified monument of its age, one of few in Europe.

Realism appeared in bourgeois portraits by Vjekoslav Karas. The characters of his portraits are true expressions of their time. Realistic landscapes are linked to certain parts of the country – Slavonian forests by artists of Osijek school, Dubrovnik in works of Celestin Medović, and Dalmatian coast in works of Menci Klement Crnčić.

In sculpture the hard realism (naturalism) of Ivan Rendić was replaced by art nouveau composed and moving reliefs by Robert Frangeš-Mihanović. Slava Raškaj is particularly notable for her watercolorworks.

Vlaho Bukovac brought the spirit of impressionism from Paris, and he strongly influenced the young artists (including the authors of "Golden Hall"). Right after he painted the screen in HNK in Zagreb with the theme of Croatian Illyrian Movement, and symbolic portraits of Croatian Writers in National Library, he founded The Society of Croatian Artists (1897), the so-called "Zagreb's colorful school". With this society the Croatian Modern Art started. On the Millennium Exhibition in Budapest they were able to set aside all other artistic options in Austria-Hungary.

The 20th century

Modern art in Croatia began with the secessionist ideas spreading from Vienna and Munich, and post-impressionism from Paris.[10] The Munich Circle used values to create volume in their paintings, in a style much simplified from more detailed earlier, academic style.[11] The Medulic Society of sculptors and painters from Split brought themes of national history and legends to their art,[12] and some of the artwork following the First World War contained a strong political message against the ruling Austro-Hungarian state. The Zagreb Spring Salon provided an annual showcase of the local art scene, and a big change was noticeable in 1919 with a move to flatter forms, and signs of cubism and expressionism were evident.[13] The avant-garde Zenit Group of the 1920s pushed for integrating the new art forms with the native cultural identity.[14] At the same time, the Earth Group sought to reflect reality and social issues in their art,[13] a movement that also saw the development of naive art.[15] The 1930s saw a return to more simple, classical styles.[13]

Following the Second World War, artists everywhere were searching for meaning and identity, leading to abstract expressionism in the U.S. and art informel in Europe. [16] In the new Yugoslavia, the communist social realism style never took hold, but Exat 51 showed the way with geometric abstraction in paintings and simplified spaces in architecture.[13]

In the 1950s, Antun Motika, one of the most celebrated modern Croatian artists together with Ivan Meštrović, generated a strong reaction from the critics with his exhibition of drawings Archaic Surrealism (Arhajski nadrealizam).[17] The exhibition had a lasting effect on Croatian art circles,[18] and is generally considered to be the boldest rejection of the dogmatic frameworks of socialist realism in Croatia.[17]

The Gorgona Group of the 1960s advocated non-conventional forms of visual expression, published their own anti-magazine, and were preoccupied by the absurd.[19] At the same time, the New Tendencies series of exhibits held in conjunction with meetings displayed a more analytical approach to art,[20] and a move towards New Media, such as photography, video, computer art, performance art and installations, focused more on the artists' process.[21] The Biafra Group of the 1970s was figurative and expressionist, engaging their audience directly.[16] By the 1980s, the New Image movement brought a return to more traditional painting and images.[16]

See also

- Croatian Architecture

- List of Croatian sculptors

- History of Croatia

- Croatian literature

- Music of Croatia

- Category:World Heritage Sites in Croatia

References

- ^ "ART". Culturenet.hr. 15 December 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Greek Colonisation of the Eastern Adriatic". culturenet.hr. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008.

- ^ "Roman Art". Artchive.com. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "WebQuest-Middle Ages". Mtsd-vt.org. 15 March 2001. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Early Middle Ages (475-1000)". SparkNotes. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Sedov, Valentin V. (1995). "Slavs in the Early Middle Ages". Rastko.org.rs. Project Rastko. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Holcomb, Melanie. "Barbarians and Romans". Metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Drake Boehm, Barbara. "Relics and Reliquaries in Medieval Christianity". Metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Reliquaries". Newadvent.org. 1911. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Croatian Art History: An Overview". Croatian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integrations. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "Munich Circle". Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "The Early Twentieth Century". Culturenet. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d Davor Matičević (October 1991). "Identity Despite Discontinuity". International Contemporary Art Network (I-CAN). Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ Irina Subotić (Spring 1990), Avant-Garde Tendencies in Yugoslavia, Art Journal, Vol. 49, No. 1, From Leningrad to Ljubljana: The Suppressed Avant-Gardes of East-Central and Eastern Europe during the Early Twentieth Century, College Art Association, pp. 21–27, JSTOR 777176

- ^ Ian Chilvers. "The Hlebine School". A Dictionary of Twentieth Century Art. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Umjetnost 20. st. u hrvatskoj" [Croatian Art of the 20th Century] (in Croatian). Scribd. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Motika, Antun". Croatian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Motika, Antun". Istrapedia. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Gorgona Group". Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "New Tendencies". Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "New Art Practice". Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

Further reading

- Pelc, Milan, ed. (2010). Hrvatska umjetnost – povijest i spomenici (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb: Institute of Art History. ISBN 978-953-6106-79-0. Retrieved 20 February 2017.