Ambigram

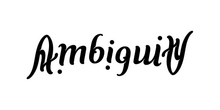

An ambigram is a calligraphic composition of glyphs (letters, numbers, symbols or other shapes) that can yield different meanings depending on the orientation of observation.[2][3] Most ambigrams are visual palindromes that rely on some kind of symmetry, and they can often be interpreted as visual puns.[4]

The term was coined by Douglas Hofstadter in 1983–1984.[2][5] Most often, ambigrams appear as visually symmetrical words. When flipped, they remain unchanged, or they mutate to reveal another meaning. "Half-turn" ambigrams undergo a point reflection (180-degree rotational symmetry) and can be read upside down, while mirror ambigrams have axial symmetry and can be read through a reflective surface like a mirror. Many other types of ambigrams exist.[6]

Ambigrams can be constructed in various languages and alphabets, and the notion often extends to numbers and other symbols. It is a recent interdisciplinary concept, combining art, literature, mathematics, cognition, and optical illusions. Drawing symmetrical words constitutes also a recreational activity for amateurs. Numerous ambigram logos are famous, and ambigram tattoos have become increasingly popular. There are methods to design an ambigram, a field in which some artists have become specialists.

Etymology

The word ambigram was coined in 1983 by Douglas Hofstadter, an American scholar of cognitive science best known as the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the book Gödel, Escher, Bach.[7][4][5] It is a neologism composed of the Latin prefix ambi- ("both") and the Greek suffix -gram ("drawing, writing").[2]

Hofstadter describes ambigrams as "calligraphic designs that manage to squeeze in two different readings."[8] "The essence is imbuing a single written form with ambiguity".[9][10]

An ambigram is a visual pun of a special kind: a calligraphic design having two or more (clear) interpretations as written words. One can voluntarily jump back and forth between the rival readings usually by shifting one's physical point of view (moving the design in some way) but sometimes by simply altering one's perceptual bias towards a design (clicking an internal mental switch, so to speak). Sometimes the readings will say identical things, sometimes they will say different things.[11][4]

Hofstadter attributes the origin of the word ambigram to conversations among a small group of friends in 1983.[12]

Prior to Hofstadter's terminology, other names were used to refer to ambigrams. Among them, the expressions "vertical palindromes"[13] by Dmitri Borgmann[14] (1965) and Georges Perec,[15][16] "designatures" (1979),[17] "inversions" (1980) by Scott Kim,[18][19] or simply "upside-down words" by John Langdon and Robert Petrick.[20]

Ambigram was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in March 2011,[6][21] and to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in September 2020.[2][22] Scrabble included the word in its database in November 2022.[23][3][24]

History

Many ambigrams can be described as graphic palindromes.

The first Sator square palindrome was found in the ruins of Pompeii, meaning it was created before the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. A sator square using the mirror writing for the representation of the letters S and N was carved in a stone wall in Oppède (France) between the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages,[26] thus producing a work made up of 25 letters and 8 different characters, 3 naturally symmetrical (A, T, O), 3 others decipherable from left to right (R, P, E), and 2 others from right to left (S, N). This engraving is therefore readable in four directions.[27]

Although the term is recent, the existence of mirror ambigrams has been attested since at least the first millennium. They are generally palindromes stylized to be visually symmetrical.

In ancient Greek, the phrase "ΝΙΨΟΝ ΑΝΟΜΗΜΑΤΑ ΜΗ ΜΟΝΑΝ ΟΨΙΝ" (wash the sins, not only the face), is a palindrome found in several locations, including the site of the church Hagia Sophia in Turkey.[28][29] It is sometimes turned into a mirror ambigram when written in capital letters with the removal of spaces, and the stylization of the letter Ν (Ν).

A boustrophedon is a type of bi-directional text, mostly seen in ancient manuscripts and other inscriptions. Every other line of writing is flipped or reversed, with reversed letters. Rather than going left-to-right as in modern European languages, or right-to-left as in Arabic and Hebrew, alternate lines in boustrophedon must be read in opposite directions. Also, the individual characters are reversed, or mirrored. This two-way writing system reveals that modern ambigrams can have quite ancient origins, with an intuitive component in some minds.

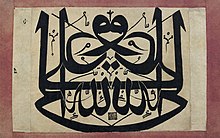

Mirror writing in Islamic calligraphy flourished during the early modern period, but its origins may stretch as far back as pre-Islamic mirror-image rock inscriptions in the Hejaz.[30]

The earliest known non-natural rotational ambigram dates to 1893 by artist Peter Newell.[31] Although better known for his children's books and illustrations for Mark Twain and Lewis Carroll, he published two books of reversible illustrations, in which the picture turns into a different image entirely when flipped upside down. The last page in his book Topsys & Turvys contains the phrase The end, which, when inverted, reads Puzzle. In Topsys & Turvys Number 2 (1902), Newell ended with a variation on the ambigram in which The end changes into Puzzle 2.[32]

In March 1904 the Dutch-American comic artist Gustave Verbeek used ambigrams in three consecutive strips of The UpsideDowns of old man Muffaroo and little lady Lovekins.[33] His comics were ambiguous images, made in such a way that one could read the six-panel comic, flip the book and keep reading.

From June to September 1908, the British monthly The Strand Magazine published a series of ambigrams by different people in its "Curiosities" column.[34] Of particular interest is the fact that all four of the people submitting ambigrams believed them to be a rare property of particular words. Mitchell T. Lavin, whose "chump" was published in June, wrote, "I think it is in the only word in the English language which has this peculiarity," while Clarence Williams wrote, about his "Bet" ambigram, "Possibly B is the only letter of the alphabet that will produce such an interesting anomaly."[34][35]

Characteristics

Natural ambigrams

In the Latin alphabet, many letters are symmetrical glyphs. The capital letters B, C, D, E, H, I, K, O, and X have a horizontal symmetry axis. This means that all words that can be written using only these letters are natural lake reflection ambigrams. For example, BOOK, CHOICE, or DECIDE.

The lowercase letters l, o, s, x and z are rotationally symmetrical, while pairs such as b/q, d/p, m/w, n/u, and in some typefaces h/y and a/e, are rotations of each other. Thus, the words "sos", "pod", "suns", "yeah", "swims", "dollop", or "passed" form natural rotational ambigrams.

More generally, a "natural ambigram" is a word that possesses one or more symmetries when written in its natural state, requiring no typographic styling. The words "bud", "bid", or "mom", form natural mirror ambigrams when reflected over a vertical axis, as does "ليبيا", the name of the country Libya in Arabic. The words "HIM", "TOY, "TOOTH" or "MAXIMUM", in all capitals, form natural mirror ambigrams when their letters are stacked vertically and reflected over a vertical axis. The uppercase word "OHIO" can flip a quarter to produce a 90° rotational ambigram when written in serif style (with large "feet" above and below the "I").

Like all strobogrammatic numbers, 69 is a natural rotational ambigram.

Patterns in nature are visible regularities of form found in the natural world.[36] Similarly, patterns in ambigrams are regularities found in graphemes. As a consequence to this "natural" property, some shapes appear more or less appropriate to handle for the designer. Ambigram candidates can become "almost natural", when all the letters except maybe one or two are symmetrically cooperative, for example the word "awesome" possesses 5 compatible letters (the central s that flips around itself, and the couples a/e and w/m).

Single words or several words

A symmetrical ambigram can be called "homogram" (contraction of "homo-ambigram") when it remains unchanged after reflection, and "heterogram" when it transforms.[11][37] In the most common type of ambigram, the two interpretations arise when the image is rotated 180 degrees with respect to each other (in other words, a second reading is obtained from the first by simply rotating the sheet).

Single word ambigrams

Douglas Hofstadter coined the word "homogram" to define an ambigram with identical letters.[11][37] In this case, the first half of the word turns into the last half.[38]

-

Ambigram "Wikipedia", drawn by French artist Jean-Claude Pertuzé, 180° rotational symmetry.

-

"Candy", 180° symmetrical ambigram.

-

"Cloud", vertical axis mirror ambigram with a cloud occupying negative space in the letter O.

-

"Doug", hypocorism for Douglas Hofstadter, the "father" of the ambigram concept.

Several words

A symmetrical ambigram is called "heterogram"[11][37] (contraction of "hetero-ambigram") when it gives another word. Visually, a heterogram ambigram is symmetrical only when both versions of the pairing are shown together. The aesthetical appearance is more difficult to design, when a changing ambigram aims to be revealed in one way only, alternatively or separately, because symmetry generally enhances elegance. Technically, there are twice more combinations of letters involved in a hetero-ambigram than in a homo-ambigram. For example, the 180° rotational ambigram "yeah" contains only two pairs of letters: y/h and e/a, whereas the heterogram "yeah / good" contains four : y/d, e/o, a/o, and h/g.

A single word ambigram cannot be hetero-, but a multiple words ambigram can be homo- type if the letters overlapse, like in "upsidedown" written attached, for example. The ambigram saying "upsidedown" one way and "upsidedown" again the other way, means it is a two words homogram. But the ambigram saying "upside" one way and "down" after rotation, means it is a two words heterogram.

There is no limitation to the number of words potentially associable, and full ambigram sentences have even been published.[15][38]

-

"True flag", self-referential flag, horizontal axis mirror hetero- type.

-

Two words ambigram "Stay Here".

Types

Ambigrams are exercises in graphic design that play with optical illusions, symmetry and visual perception. Some ambigrams feature a relationship between their form and their content. Ambigrams usually fall into one of several categories.

180° rotational ambigrams

"Half-turn" ambigrams or point reflection ambigrams, commonly called "upside-down words", are 180° rotational symmetrical calligraphies.[7] We can read them right side up or upside down, or both.

Rotation ambigrams are the most common type of ambigrams for good reason. When a word is turned upside down, the top halves of the letters turn into the bottom halves. And because our eyes pay attention primarily to the top halves of letters when we read, that means that you can essentially chop off the top half of a word, turn it upside down, and glue it to itself to make an ambigram. [...][41]

-

Rotating ambigram "Say Yes", half-turn type with 8 occurrences of the same pattern. The phrase itself is a phonetic palindrome.

-

Point reflection ambigram merci.

-

"Home / Away", 180° rotational hetero-ambigram.

-

"Lift", half-turn ambigram logo.

Mirror ambigrams

A mirror ambigram, or reflection ambigram, is a design that can be read when reflected in a mirror vertically, horizontally, or at 45 degrees,[42] giving either the same word or another word or phrase.

Vertical axis reflection ambigrams

When the reflecting surface is vertical (like a mirror for example), the calligraphic design is a vertical axis mirror ambigram.

The "museum" ambigram is almost natural with mirror symmetry, because the first two letters are easily exchanged with the last two, and the lowercase letter e can be transformed into s by a fairly obvious typographical acrobatics.[43]

Vertical axis mirror ambigrams find clever applications in mirror writing (or specular writing), that is formed by writing in the direction that is the reverse of the natural way for a given language, such that the result is the mirror image of normal writing: it appears normal when it is reflected in a mirror. For example, the word "ambulance" could be read frontward and backward in a vertical axis reflective ambigram. Following this idea, the French artist Patrice Hamel created a mirror ambigram saying "entrée" (entrance, in French) one way, and "sortie" (exit) the other way, displayed in the giant glass façade of the Gare du Nord in Paris, so that the travelers coming in read entrance, and those leaving read way out.[44]

Horizontal axis reflection ambigrams

When the reflecting surface is horizontal (like a mirroring lake for example), the calligraphic design is a horizontal axis mirror ambigram.

The book Ambigrams Revealed features several creations of this type, like the word "Failure" mirroring in the water of a pond to give "Success", or "Love" changing into "Lust".[45]

Figure-ground ambigrams

In a figure / ground ambigram, letters fit together so the negative space around and between one word spells another word.[42]

In Gestalt psychology, figure–ground perception is known as identifying a figure from the background. For example, black words on a printed paper are seen as the "figure", and the white sheet as the "background". In ambigrams, the typographic space of the background is used as negative space to form new letters and new words. For example, inside a capital H, one can easily insert a lowercase i.

The oil painting You & Me (US) by John Langdon (1996) belongs to this category. The word "me" fills the space between the letters of "you".[46]

Ambigram tessellations

With Escher-like tessellations associated to word patterns, ambigrams can be oriented in three, four, and up to six directions via rotational symmetries of 120°, 90° and 60° respectively,[47] such as those created by French artist Alain Nicolas.[48] Some words can also transform in the negative space, but the multiplication of constraints often has the effect of reducing either the readability or the complexity of the designed words.

Ambigram tessellations are word puzzles, in which geometry sets the rules.[48]

-

Tessellation build with the natural ambigram "Yeah".

-

3-directional ambigram "Serie" (series, in French), tessellation using a 120° rotational symmetry. Created from a hexagon.

![]() Media related to Ambigram tessellations at Wikimedia Commons.

Media related to Ambigram tessellations at Wikimedia Commons.

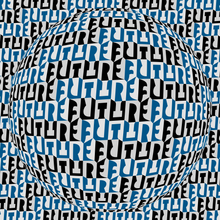

Chain ambigrams

A chain ambigram is a design where a word (or sometimes words) are interlinked, forming a repeating chain.[42] Letters are usually overlapped: a word will start partway through another word. Sometimes chain ambigrams are presented in the form of a circle. For example, the chain "...sunsunsunsun..." can flip upside down, but not the word "sun" alone, written horizontally. A chain ambigram can be constituted of one to several elements. A single element ambigram chain is like a snake eating its own tail. A two-elements ambigram chain is like a snake eating the neighbor's tail with the neighbor eating the first snake's, and so on.

Scott Kim's "Infinity" works, and that of John Langdon "Chain reaction", are also self-referential, since the first is infinite in the literal sense of the word, and the second, both reversible at 180° and interfering around the letter O, evokes a chain reaction.[49]

Spinonyms

A spinonym is a type of ambigram in which a word is written using the same glyph repeated in different orientations.[38] WEB is an example of a word that can easily be made into a spinonym.

-

"Happy new year" spinonym, the same glyph in different orientations shapes the twelve letters of the sentence.

Perceptual shift ambigrams

Perceptual shift ambigrams, also called "oscillation" ambigrams, are designs with no symmetry but can be read as two different words depending on how the curves of the letters are interpreted.[42] These ambigrams work on the principle of rabbit-duck-style ambiguous images.

For example Douglas Hofstadter expresses the dual nature of light as revealed by physics with his perceptual shift ambigram Wave / Particle.

90° rotational ambigrams

"Quarter-turn" ambigrams or 90° rotational ambigrams turn clockwise or counterclockwise to express different meanings.[4] For example, the letter U can turn into a C and reciprocally, or the letters M or W into an E.[38]

Totem ambigrams

A totem ambigram is an ambigram whose letters are stacked like a totem, most often offering a vertical axis mirror symmetry. This type helps when several letters fit together, but hardly the whole word. For example, in the Maria monogram, the letters M, A and I are individually symmetrical, and the pairing R/A is almost naturally mirroring. When adequately stacked, the 5 letters produce a nice totem ambigram, whereas the whole name "Maria" would not offer the same cooperativeness.

The ambigrammist artist John Langdon designed several totemic assemblages, such as the word "METRO" composed of the symmetrical letter M, then section ETR, and below O; or the sentence "THANK YOU", vertical assembly of T, H, A, then of the symmetric NK couple, then finally Y, O, U.[50]

Fractal ambigrams

In mathematics, a fractal is a geometrical shape that exhibits invariance under scaling. A piece of the whole, if enlarged, has the same geometrical features as the entire object itself. A fractal ambigram is a sort of space-filling ambigrams where the tiled word branches from itself and then shrinks in a self-similar manner, forming a fractal.[51] In general, only a few letters are constrainted in a fractal ambigram. The other letters don't need to look like any other, and thus can be shaped freely.

3-dimensional ambigrams

A 3D ambigram is a design where an object is presented that will appear to read several letters or words when viewed from different angles. Such designs can be generated using constructive solid geometry, a technique used in solid modeling, and then physically constructed with the rapid prototyping method.

3-dimensional ambigram sculptures can also be achieved in plastic arts. They are volume ambigrams.

The original 1979 edition of Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher, Bach featured two 3-D ambigrams on the cover.[52]

Complex ambigrams

Complex ambigrams are ambigrams involving more than one symmetry, or satisfying the criteria for several types. For example, a complex ambigram can be both rotational and mirror with a 4-fold dihedral symmetry. Or a spinonym that reads upside down is also a complex ambigram.

-

The famous DJ Étienne de Crécy has a complex ambigram logo "EDC", mirroring through a horizontal axis, and figure-ground type with a power plug pictogram inserted in the negative space.

Symbols

Other languages

Ambigrams exist in many languages. With the Latin alphabet, they generally mix lowercase and uppercase letters. But words can also be symmetrical in other alphabets, like Arabic, Bengali, Cyrillic, Greek, and even in Chinese characters and Japanese kanji.

In Korean, 곰 (bear) and 문 (door), 공 (ball) and 운 (luck), or 물 (water) and 롬 (ROM) form a natural rotational ambigram. Some syllables like 응 (yes), 표 (ticket/signage) or 를 (object particle), and words like "허리피라우" (straighten your back) also make full ambigrams.

The han character meaning "hundred" is written 百, that makes a natural 90° rotational ambigram when the glyph makes a quarter turn counterclockwise, one sees "100".[53]

![]() Media related to Ambigrams by language at Wikimedia Commons.

Media related to Ambigrams by language at Wikimedia Commons.

Numbers

An ambigram of numbers, or numeral ambigram, contains numerical digits, like 1, 2, 3...[38]

In mathematics, a palindromic number (also known as a numeral palindrome) is a number that remains the same when its digits are reversed through a vertical axis (but not necessarily visually). The palindromic numbers containing only 1, 8, and 0, constitute natural numeric ambigrams (visually symmetrical through a mirror). Also, because the glyph 2 is graphically the mirror image of 5, it means numbers like 205 or 85128 are natural numeral mirror ambigrams. Though not palindromic in the mathematical sense, they read frontward and backward like real ambigrams.

A strobogrammatic number is a number whose numeral is rotationally symmetric, so that it appears the same when rotated 180 degrees. The numeral looks the same right-side up and upside down (e.g., 69, 96, 1001).[54][55][56]

Some dates are natural numeral ambigrams.[57] In March 1961, artist Norman Mingo created an upside-down cover for Mad magazine featuring an ambigram of the current year. The title says "No matter how you look at it... it's gonna be a Mad year. 1961, the first upside-down year since 1881."[58] Tuesday, 22 February 2022, was a palindrome and ambigram date called "Twosday" because it contained reversible 2 (two).[59][60][61]

Ambigrams of numbers receive most attention in the realm of recreational mathematics.[4][62]

Ambigrams with numbers sometimes combine letters and numerical digits. Because the number 5 is approximately shaped like the letter S, the number 6 like a lowercase b, the number 9 like the letter g, it is possible to play on these similarities to design ambigrams. A good example is the Sochi 2014 (Olympic games) logo where the four glyphs contained in 2014 are exact symmetries of the four letters S, o, i and h, individually.[63]

Other symbols

As alphabet letters are glyphs used in the writing systems to express the languages visually, other symbols are also used in the world to code other fields, like the prosigns in the Morse code or the musical notes in music.

Similarly to the ambigrams of letters, the ambigrams with other symbols are generally visually symmetrical, either point reflective or reflective through an axis.

The international Morse code distress signal SOS ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ is a natural ambigram constituted of dots and dashes. It flips upside down or through a mirror.

In morse code, the letter P coded ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ and the letter R coded ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ are individually symmetrical, like many other letters and numbers. Also, the letter G coded ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ is the exact reverse of the letter W coded ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ . Thus, the combination ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ / ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ coding the pairing G/W constitutes a natural ambigram. Consequently, meaningful natural ambigrams written in morse code certainly exist, like for example the words "wog" ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ , "Dou" ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ or "mom" ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ .[7][64][65]

In music, the interlude from Alban Berg's opera Lulu is a palindrome, thus the score made up of musical notes is almost symmetrical through a vertical axis.[66]

In biology, researchers study the ambigrammatic property of narnaviruses by using visual representations of the symmetrical sequences.[36][1][67]

Fields

Art

Calligraphy and typography

Instead of simply writing them, ambigram lettering covers the art of drawing letters. In ambigram calligraphy, each letter acts as an illustration, each letter is created with attention to detail and has a unique role within a composition. Lettering ambigrams do not translate into combinations of alphabet letters that can be used like a typeface, since they are created with a specific candidate in mind.

The calligrapher, graffiti writer and graphic designer Niels Shoe Meulman created several rotational ambigrams like the number "fifty",[69] the names "Shoe / Patta",[70] and the opposition "Love / Fear".[71]

The cover of the 7th volume of the typography book Typism is an ambigram drawn by Nikita Prokhorov.[72]

The American type designer Mark Simonson designed poetic and humorous ambigrams, such as the words "Revelation", "Typophile", and the symbiosis "Drink / Drunk".[73] The last one makes a visual pun when printed on a shot glass, sold commercially.[74]

Logos

Since they are visually striking, and sometimes surprising, ambigram words find large application in corporate logos and wordmarks, setting the visual identity of many organizations, trademarks and brands.[75]

In 1968[76] or 1969, Raymond Loewy designed the rotational New Man ambigram logo.[77][78][79]

The mirror ambigram DeLorean Motor Company logo, designed by Phil Gibbon, was first used in 1975.[80][81][82]

Robert Petrick designed the invertible Angel logo[83] in 1976.

The logo Sun (Microsystems) designed by professor Vaughan Pratt[84] in 1982 fulfills the criteria of several types: chain ambigram, spinonym, 90° and 180° rotational symmetries.

The Swedish pop group ABBA owns a mirror ambigram logo stylized AᗺBA with a reversed B, designed by Rune Söderqvist[85] in 1976.[86]

The Ventura logo of the Visitors & Convention Bureau's board, in California, cost US$25,000 and was created in 2014 by the DuPuis group. It uses a 180° rotational symmetry.[87][88]

Other famous ambigram logos include: the insurance company Aviva;[89] the acronym CRD (Capital Regional District) in the Canadian province of British Columbia;[90] the American multinational corporation DXC Technology; the two-sided marketplace for residential cleaning Handy;[91][92] the brand name of French premium high-speed train services InOui;[93] the French company specializing in ticketing and passenger information systems IXXI; the century-old brand Maoam of the confectionery manufacturer Haribo;[94] the American industrial rock band NIͶ; the Japanese food company Nissin; the biotechnology company Noxxon Pharma, founded in 1997; the online travel agency Opodo in 2001;[95] the brand of food products OXO[96] born in 1899; the video game Pod; the American developer and manufacturer of audio products Sonos;[97] the American professional basketball team Phoenix Suns;[98][99] the German manufacturer of adhesive products UHU; the quadruple symmetrical logo UA from the American clothing brand Under Armour ; the Canadian corporation mandated to operate intercity passenger rail service VIA in 1978;[100] the American international broadcaster VOA, born in 1942; and the Malaysian mobile virtual network operator XOX. The student edition of the Tesco Clubcard used 180° rotational symmetry.[101]

Visual communication

Because they are visual puns,[4] ambigrams generally attract attention, and thus can be used in visual communication to broadcast a marketing or political message.

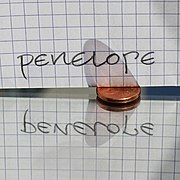

In France, a mirror ambigram "Penelope / benevole" legible through a horizontal axis became a meme on the web after its diffusion on Wikimedia Commons.[102] Penelope Fillon, wife of French politician and former Prime Minister of France François Fillon, is suspected of having received wages for a fictitious job. Ironically, her name through the mirror becomes benevole (voluntary in French), suggesting dedication for a free service. Shared tens of thousands of times on the social networks, this humorous ambigram made the buzz via several French,[103] Belgian[104][105] and Swiss[102] medias.

Ambigrams are regularly used by communication agencies such as Publicis to engage the reader or the consumer through two-way messages.[106] Thus, in 2021, male first names transformed into female first names are included in a Swiss advertising campaign aimed at raising awareness about gender equality. An intriguing catchphrase typography upside down invites the reader to rotate the magazine, in which the first names "Michael" or "Peter" are transformed into "Nathalie" or "Alice".[107][108]

In 2015 iSmart's logo on one of its travel chargers went viral because the brand's name turned out to be a natural ambigram that read "+Jews!" upside down. The company noted that "...we learned a powerful lesson of what not to do when creating a logo." [109]

Cinema posters sometimes seduce observers with ambigram titles, such as that of Tenet by Christopher Nolan, by central symmetry.[27] or Anna by Luc Besson around a vertical axis,[110][111]

-

Half-turn traffic sign using a directional arrow symbol to display alternatively "Station / Toilets".

-

Visual pun "Avoid the plane" to attract attention towards the environmental impact of aviation.

Comics

The American artist and writer Peter Newell published a rotational ambigram in 1893 saying "Puzzle / The end" in the book containing reversible illustrations Topsys & Turvys.[31]

In March 1904 the Dutch-American comic artist Gustave Verbeek used ambigrams in three consecutive strips of The UpsideDowns of old man Muffaroo and little lady Lovekins.[33] His comics were ambiguous images, made in such a way that one could read the six-panel comic, flip the book and keep reading. In The Wonderful Cure of the Waterfall (13 March 1904) an Indian medicine man says 'Big waters would make her very sound', while when flipped the medicine man turns into an Indian woman who says 'punos dery, eay apew poom, serlem big'. Which is explained as, 'poor deary' several foreign words that meant that she would call the 'Serlem Big'. The next comic called At the House of the Writing Pig (20 March 1904), where two ambigram word balloons are featured. The first features an angry pig trying to make the main protagonist leave by showing a sign that says; 'big boy go away, dis am home of mr h hog', up side down it reads 'Boy yew go away. We sip. Home of hog pig.' The protagonist asks the pig if it wants a big bun, upon which it replies 'Why big buns? Am mad u!', which flips into 'In pew we sang big hym'. Finally in The Bad Snake and the Good Wizard (1904 Mar 27) there are two more ambigrams. The first turns 'How do you do' into the name of a wizard called 'Opnohop Moy', the second features a squirrel telling the protagonist 'Yes further on' only to inform it that there are 'No serpents here' on his way back. In a 2012 Swedish remake of the book,[112] the artist Marcus Ivarsson redraws The Bad Snake and the Good Wizard in his own style. He removes the squirrel, but keeps the other ambigram. 'How do you do' is replaced by 'Nejnej' (Swedish for no) and the wizard is now called 'Laulau'.

![]() Media related to Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek at Wikimedia Commons.

Media related to Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek at Wikimedia Commons.

Oubapo, workshop of potential comic book art, is a comics movement which believes in the use of formal constraints to push the boundaries of the medium. Étienne Lécroart, cartoonist, is a founder and key member of Oubapo association, and has composed cartoons that could be read either horizontally, vertically, or in diagonal, and vice versa, sometimes including appropriate ambigrams.[113]

Drawings and paintings

The British painter, designer and illustrator Rex Whistler, published in 1946 a rotational ambigram "¡OHO!" for the cover of a book gathering reversible drawings.[114]

The artist John Langdon, specialist of ambigrams,[75] designed many color paintings featuring ambigrams of all kinds, figure-ground, rotational, mirror or totem. Among other influences, he particularly admires M. C. Escher's drawings.[115]

The Canadian artist Kelly Klages painted several acrylics on canvas with ambigram words and sentences referring to famous writers' novels written by William Shakespeare or Agatha Christie, such as Third Girl, The Tempest, After the Funeral, The Hollow, Reformation, Sherlock Holmes, and Elephants Can Remember.[116]

Sculptures

The German conceptual artist Mia Florentine Weiss built a sculptural ambigram Love Hate,[117] that has traveled Europe as a symbol of peace and change of perspective.[118] Depending on which side the viewer looks at it, the sculpture says "Love" or "Hate". A similar concept was installed in front of the Reichstag building in Berlin with the words "Now / Won". Both sculptures are mirror type ambigrams, symmetrical around a vertical axis.[119]

The Swiss sculptor Markus Raetz made several three-dimensional ambigram works, featuring words generally with related meanings, such as YES-NO (2003),[120] ME-WE (2004, 2010),[121] OUI-NON (2000–2002) in French,[122][123] SI–NO (1996)[124] and TODO-NADA (1998) in Spanish[125][126] These are anamorphic works, which change in appearance depending on the angle of view of the observer. The OUI–NON ambigram is installed on the Place du Rhône, in Geneva, Switzerland, at the top of a metal pole. Physically, the letters have the appearance of iron twists. With the perspective, this work demonstrates that reality can be ambiguous.[123]

Some ambigram sculptures by the French conjurer Francis Tabary are reversible by a half-turn rotation, and can therefore be exhibited on a support in two different ways.[127][128]

Literature

Palindromes

Ambigrams are sorts of visual palindromes.[129] Some words turn upside down, others are symmetrical through a mirror. Natural ambigram palindromes exist, like the words "wow", "malayalam"[130] (Dravidian language), or the biotechnology company Noxxon that possesses a palindromic name associated to a rotational ambigram logo. But some words are natural ambigrams, though not palindromes in the literary acception, like "bud" for example, because b and d are different letters. As a result, some words and sentences are good candidates for ambigrammists, but not for palindromists, and reciprocally, since the constraint slightly differ. Authors of ambigrams also benefit from a certain flexibility by playing on the typeface and graphical adjustments to influence the reading of their visual palindromes.

Oulipo, workshop of potential literature, seeks to create works using constrained writing techniques.[13] Georges Perec, French novelist and member of the Oulipo group, designed a rotational ambigram, that he called "vertical palindrome".[15] Sibylline, the sentence "Andin Basnoda a une épouse qui pue" in French means "Andin Basnoda has a smelly wife". Perec did not care about punctuation spaces, but his creation flips easily with a classical font like Arial.

Visual palindromes sometimes perfectly illustrate literary contents. The American author Dan Brown incorporated John Langdon's designs into the plot of his bestseller Angels & Demons, and his fictional character Robert Langdon's surname was a homage to the ambigram artist.[131]

The fantasy novel Abarat, written and illustrated by Clive Barker, features an ambigram of the title on its cover.[132]

Calligrams

A calligram is text arranged in such a way that it forms a thematically related image. It can be a poem, a phrase, a portion of scripture, or a single word. The visual arrangement can rely on certain use of the typeface, calligraphy or handwriting. The image created by the words illustrates the text by expressing visually what it says, or something closely associated.

In Islamic calligraphy, symmetrical calligrams appear in ancient and modern periods, forming mirror ambigrams in Arabic language.[30]

The word "OK" turned 90° counterclockwise evokes a human icon, with the letter O forming the head and the letter K the arms and the legs. The Norwegian Climbing Club Oslo Klatreklubb (acronym "OK") borrowed the concept of this natural calligram for their official logo.[133]

Semantics

As described by Douglas Hofstadter, ambigrams are visual puns having two or more (clear) interpretations as written words.[4]

Multilingual ambigrams can be read one way in a language, and another way in a different language or alphabet.[42] Multi-lingual ambigrams can occur in all of the various types of ambigrams, with multi-lingual perceptual shift ambigrams being particularly striking.

Like certain anagrams with providential meanings such as "Listen / Silent" or "The eyes / They see", ambigrams also sometimes take on a timely sense, for example "up" becomes the abbreviation "dn", very naturally by rotation of 180°.[134] But on the other hand, it happens that the luck of the letters makes things bad. This is the case with the weird anagram "Santa / Satan", as it is with a rotational ambigram that has gone viral because of the paradoxical and unintentional message it expresses. Spotted in 2015 on a metal medal marketed without bad intention, the text "hope" displays upside down with a fairly obvious reading "Adolf", first name of the Nazi leader situated at the antipodes of optimism. This coincidence photographed by an Internet user was relayed by several media and constitutes an ambiguous image.[135][136]

Mathematics

Recreational mathematics is carried out for entertainment rather than as a strictly research and application-based professional activity.[62] An ambigram magic square exists, with the sums of the numbers in each row, each column, and both main diagonals the same right side up and upside down (180° rotational design). Numeral ambigrams also associate with alphabet letters. A "dissection" ambigram of "squaring the circle" was achieved in a puzzle where each piece of the word "circle" fits inside a perfect square.[4]

Burkard Polster, professor of mathematics in Melbourne[137] conducted researches on ambigrams and published several books dealing with the topic, including Eye Twisters, Ambigrams & Other Visual Puzzles to Amaze and Entertain.[138] In the abstract Mathemagical Ambigrams, Polster performs several ambigrams closely related to his realm, like the words "algebra", "geometry", "math", "maths", or "mathematics".[4]

| Message written with the digits "07734" upside down. |

Calculator spelling is an unintended characteristic of the seven-segment display traditionally used by calculators, in which, when read upside-down, the digits resemble letters of the Latin alphabet. Also, palindromic numbers and strobogrammatic numbers sometimes attract attention of mathematician ambigrammists.[55][54]

Ambigram tessellations and 3D ambigrams are two types particularly fun for the mathematician in geometry. Word patterns in tessellations can start from 35 different fundamental polygons, such as the rhombus, the isosceles right triangle, or the parallelogram.[47]

Word puzzles are used as a source of entertainment, but can additionally serve an educational purpose. The American puzzle designer Scott Kim published several ambigrams in Scientific American in Martin Gardner's "Mathematical Games" column, among them long sentences like "Martin Gardner's celebration of mind" turning into "Physics, patterns and prestidigitation".[139]

Philosophy and cognition

Duality and analogy

In the word "ambigram", the root ambi- means "both" and is a popular prefix in a world of dualities, such as day/night, left/right, birth/death, good/evil.[140] In Wordplay: The Philosophy, Art, and Science of Ambigrams,[141] John Langdon mentions the yin and yang symbol as one of his major influences to create upside down words.

Ambigrams are mentioned in Metamagical Themas, an eclectic collection of articles that Douglas Hofstadter wrote for the popular science magazine Scientific American during the early 1980s.[9]

Seeking the balance point of analogies is an aesthetic exercise closely related to the aesthetically pleasing activity of doing ambigrams, where shapes must be concocted that are poised exactly at the midpoint between two interpretations. But seeking the balance point is far more than just aesthetic play; it probes the very core of how people perceive abstractions, and it does so without their even knowing it. It is a crucial aspect of Copycat research.[9]

Cognition and psychology

Legibility is an important aspect in successful ambigrams. It concerns the ease with which a reader decodes symbols. If the message is lost or difficult to perceive, an ambigram does not work.[8] Readability is related to perception, or how our brain interprets the forms we see through our eyes.[142]

Symmetry in ambigrams generally improves the visual appearance of the calligraphic words.[38] Hermann Rorschach, inventor of the Rorschach Test notices that asymmetric figures are rejected by many subjects. Symmetry supplies part of the necessary artistic composition.[143]

For many amateurs, designing ambigrams represents a recreational activity, where serendipity can play a fertile role, when the author makes an unplanned fortunate discovery.[4][34]

Magic

In magic, ambigrams work like visual illusions, revealing an unexpected new message from a particular written word.[145]

In the first series of the British show Trick or Treat, the show's host and creator Derren Brown uses cards with rotational ambigrams.[146][147] These cards can read either 'Trick' or 'Treat'.

Ambiguous images, of which ambigrams are a part, cause ambiguity in different ways. For example, by rotational symmetry, as in the Illusion of The Cook by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1570);[148] sometimes by a figure-ground ambivalence as in Rubin vase; by perceptual shift as in the rabbit–duck illusion, or through pareidolias; or again, by the representation of impossible objects, such as Necker cube or Penrose triangle. For all these types of images, certain ambigrams exist, and can be combined with visuals of the same type.

John Langdon designed a figure-ground ambigram "optical illusion" with the two words "optical" and "illusion", one forming the figure and the other the background. "Optical" is easier to see initially but "illusion" emerges with longer observation.[149]

Tattooing

One of the most dynamic sectors that harbors ambigrams is tattooing. Because they possess two ways of reading, ambigram tattoos inked on the skin benefit from a "mind-blowing" effect. On the arm, sleeve tattoos flip upside-down, on the back or jointly on two wrists they are more striking with a mirror symmetry. A large range of scripts and fonts is available. Experienced ambigram artists can create an optical illusion with a complex visual design.[150]

In 2015, an ambigram tattoo went viral following an advertising campaign developed by the Publicis group two years earlier. The Samaritans of Singapore organization, active in suicide prevention, has a 180° reversible "SOS" ambigram logo, acronym of its name and homonym of the famous SOS distress signal. In 2013, this center orders advertisements that could be inserted in magazines to make readers aware of the problem of depression among young people, and the communication agency notices the symmetrical aspect of the logo. As a result, it begins to produce several ambigrammatic visuals, staged in photographic contexts, where sentences such as "I'm fine", "I feel fantastic" or "Life is great" turn into "Save me", "I'm falling apart", and "I hate myself". Readers noticing this logo placed at the upper left corner of the page with an upside-down typographical catchphrase rotate the newspaper and visualize the double calligraphed messages, which call out with the SOS.[106][151] These ads are so influential that Bekah Miles, an American student herself coming out of a severe depression, chooses to use the "I'm fine / Save me" ambigram to get a tattoo on her thigh. Posted on Facebook, the two-sided photography immediately appeals to many young people, impressed or sensitive to this difficulty.[152][153] To educate its students, George Fox University in the United States then relays the optical illusion in its official journal, through a video totaling more than three million views[154] and the information is also reproduced in several local media and international organizations, thus helping to popularize this famous two-way tattoo.[155][156] Less fortunate, another teenage girl, aged 16, committed suicide, with her also this ambigram found on a note in her room, "I'm fine / Save me", reversible calligraphy today printed on badges and bracelets, for educational purposes.[157]

Manufacturing

Clothing and fashion

Adidas marketed a line of sneakers called "Bounce", with an ambigram typography printed inside the shoe.

Several clothing brands, such as Helly Hansen (HH), Under Armour (UA), or New Man, raise an ambigram logo as their visual identity.[79]

Mirror ambigrams are also sometimes placed on T-shirts, towels and hats, while socks are more adapted to rotational ambigrams. The conceptual artist Mia Florentine Weiss marketed T-shirts and other products with her mirror ambigram Love Hate.[158][118] Likewise, the city of Ventura in California sells sweatshirts, caps, jackets, and other fashion accessories printed with its rotational ambigram logo.[159]

-

Rotational and reflective ambigram "Ideal", printed on a T-shirt.

-

Helly Hansen, Norwegian manufacturer and retailer of clothing and sports equipment, has an ambigram logo.

Accessories

The CD cover of the thirteenth studio album Funeral by American rapper Lil Wayne features a 180° rotational ambigram reading "Funeral / Lil Wayne".[160]

The special edition paper sleeve (CD with DVD) of the solo album Chaos and Creation in the Backyard by Paul McCartney features an ambigram of the singer's name.[161]

The Grateful Dead have used ambigrams several times, including on their albums Aoxomoxoa and American Beauty.[citation needed]

Although the words spelled by most ambigrams are relatively short in length, one DVD cover for The Princess Bride movie creates a rotational ambigram out of two words "Princess Bride", whether viewed right side up or upside down. [162]

The cover of the studio album Create/Destroy/Create by rock band Goodnight, Sunrise is an ambigram composition constituted of two invariant words, "create" and "destroy", designed by Polish artist Daniel Dostal.[163]

The reversible shot glass containing a changing message "Drink / Drunk", created by the typographer Mark Simonson was manufactured and sold in the market.[74]

The concept of reversible sign that some merchants use through their windows to indicate that the store is sometimes "open", sometimes "closed", was inaugurated at the beginning of the 2000s, by a rotational ambigram "Open / Closed" developed by David Holst.[43]

Creating ambigrams

Different ambigram artists, sometimes called ambigrammists,[9][164] may create distinctive ambigrams from the same words, differing in both style and form.

Handmade designs

There are no universal guidelines for creating ambigrams, and different ways of approaching problems coexist. A number of books suggest methods for creation, including WordPlay,[75] Eye Twisters,[138] and Ambigrams Revealed,[38] in English.

Ambigram generators

Computerized methods to automatically create ambigrams have been developed. Most of them function on the simplified principle of mapping a single letter to another single letter. Because of this weakness, most of them can only map a word to itself or to another word that is the same length and do not combine letters. Thus, the generated ambigrams are in general of poor quality when compared to hand made ambigrams. More sophisticated techniques employ databases of thousands of curves to create complex ambigrams.[citation needed] Some ambigram generators are free, while some others require payment.

Artists

John Langdon and Scott Kim each believed that they had invented ambigrams in the 1970s.[165]

Douglas Hofstadter

Douglas Hofstadter coined the term.[4]

To explain visually the numerous types of possible ambigrams, Hofstadter created many pieces with different constraints and symmetries.[166] Hofstadter has had several exhibitions of his artwork in various university galleries.[167][168]

According to Scott Kim, Hofstadter once created a series of 50 ambigrams on the name of all the states in the US.[169]

In 1987 a book of 200 of his ambigrams, together with a long dialogue with his alter ego Egbert G. Gebstadter on ambigrams and creativity, was published in Italy.[5][12]

John Langdon

John Langdon is a self-taught artist, graphic designer and painter, who started designing ambigrams in the late 1960s and early 70s. Lettering specialist, Langdon is a professor of typography and corporate identity at Drexel University in Philadelphia.[170]

John Langdon produced a mirror image logo "Starship" in 1972-1973,[171][172] that was sold to the rock band Jefferson Starship.

Langdon's ambigram book Wordplay was published in 1992. It contains about 60 ambigrams. Each design is accompanied by a brief essay that explores the word's definition, its etymology, its relationship to philosophy and science, and its use in everyday life.[75]

Ambigrams became more popular as a result of Dan Brown incorporating John Langdon's designs into the plot of his bestseller, Angels & Demons, and the DVD release of the Angels & Demons movie contains a bonus chapter called "This is an Ambigram". Langdon also produced the ambigram that was used for some versions of the book's cover.[165] Brown used the name Robert Langdon for the hero in his novels as an homage to John Langdon.[131][173]

Blacksmith Records, the music management company and record label, possesses a rotational ambigram logo[174] designed by John Langdon.[175]

Scott Kim

Scott Kim is one of the best-known masters of the art of ambigrams.[78] He is an American puzzle designer and artist who published in 1981 a book called Inversions with ambigrams of many types.[18][173]

Other artists

Nikita Prokhorov is a graphic artist, typographer and professional ambigrammist. His book Ambigrams Revealed showcases ambigram designs of all types, from all around the world.[38][176]

Born in 1946, Alain Nicolas is a specialist of figurative and ambigram tessellations. In his book, he performed many tilings with various words like "infinity", "Einstein" or "inversion" legible in many orientations.[47] According to The Guardian, Nicolas has been called "the world's finest artist of Escher-style tilings".[177]

References

- ^ a b Cepelewicz, Jordana (2020-02-12). "New Clues About 'Ambigram' Viruses With Strange Reversible Genes". Quanta Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-09-17. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Definition of ambigram". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ a b Mouriquand, David (2022-11-18). "Scrabble adds 500 new words to its official dictionary". Euronews. Lyon. Archived from the original on 2022-11-24. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Polster, Burkard. "Mathemagical Ambigrams" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-07-05. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ a b c "Douglas R. Hofstadter". Indiana University. 2007-03-21. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b "Ambigram". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2023-07-25. Retrieved 2023-07-25.

- ^ a b c Witherellspecial, Jim (2022-02-27). "In a word: Wow, the many ways words are symmetrical". Sun Journal. Maine. Archived from the original on 2022-05-04. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ a b "Deciphering the art of ambigrams". Adobe. Retrieved 2021-08-08.

- ^ a b c d Hofstadter, Douglas (2008). Metamagical Themas: Questing For The Essence Of Mind And Pattern. Basic Books. p. 880. ISBN 978-0-7867-2386-7.

- ^ Hofstadter, Douglas (2008). Metamagical Themas: Questing For The Essence Of Mind And Pattern. Basic Books. p. 880. ISBN 978-0-7867-2386-7. Archived from the original on 2023-09-05.

- ^ a b c d Hofstadter 1987.

- ^ a b Polster 2007, p. 198.

- ^ a b "Are You an Oulipian?". Potential Plus UK. Milton Keynes. 2022-11-16. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ Borgmann, Dmitri (1965). Language on Vacation: An Olio of Orthographical Oddities. Scribner. p. 27. ASIN B0007FH4IE.

- ^ a b c "L'écrit touareg du sable au papier. Un typographe français a retranscrit l'alphabet des hommes du désert". Liberation (in French). 1996-07-27. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "Ce repère, Perec" (PDF). APMEP (Association des Professeurs de Mathématiques de l'Enseignement Public) (in French). Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ OMNI magazine, September 1979, page 143, work of Scott Kim

- ^ a b Kim 1986.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 25.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 18.

- ^ "Latest update March 2011 (List of new words)". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2011-04-10. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ "Words We're Watching: 'Ambigram'". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ Scottie, Andrew (2022-11-16). "Scrabble adds 500 new playable words, like 'vax,' 'deepfake' and 'Jedi'". CNN. Atlanta. Archived from the original on 2022-11-20. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ "Words Added to the Scrabble Dictionary". Merriam-Webster. Springfield, Massachusetts. 2022-11-16. Archived from the original on 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ "Παναγία Μαλεβή: Το Άγιο Όρος της Πελοποννήσου". Dinfo.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2023-11-15. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ "Menerbes". Lydie's House (in French). Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b "The ancient palindrome that explains Christopher Nolan's Tenet". Vox. 2020-09-04. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ R. Langford-James, A Dictionary of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Ayer Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8337-5047-1, p. 61.

- ^ Barry J. Blake, Secret Language: Codes, Tricks, Spies, Thieves, and Symbols, Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-957928-0, p. 15.

- ^ a b "Islamic Calligraphy and Visions" (PDF). Crosbi. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b "Topsys & turvys". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Polster 2007, p. 6.

- ^ a b Verbeek, Gustave (2009). The Upside-Down World of Gustave Verbeek. Sunday Press. ISBN 978-0-9768885-7-4.

- ^ a b c Newnes, George (1908). "Curiosities". The Strand Magazine. No. 36. p. 359. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Ambigrams Chump, honey, M. H. Hill, Bet, and five more words – Strand Magazine 1908

- ^ a b DeRisi, Joseph L.; Huber, Greg; Kistler, Amy; Retallack, Hanna; Wilkinson, Michael; Yllanes, David (2019-11-29). "An exploration of ambigrammatic sequences in narnaviruses". Nature. 9 (1) 17982: 17982. Bibcode:2019NatSR...917982D. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54181-3. PMC 6884476. PMID 31784609. S2CID 202854658.

- ^ a b c de Gruyter, Walter (2004). Semiotik Semiotics. Herbert Ernst Wiegand. p. 3588. ISBN 978-3-11-017962-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Prokhorov 2013.

- ^ Cloez, Bertrand (2022-03-22). Recueil de curiosités mathématiques (in French). Éditions Ellipses. p. 51. ISBN 978-2-340-06713-4. Archived from the original on 2022-11-16. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ a b Koetz, Matt (2017). "Our Renowned Newsletter - The Renowned Brown" (PDF). Nazareth College (New York). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-11-16. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e Prokhorov 2013, p. 112.

- ^ a b Jean-Paul Delahaye (2004-09-01). "Ambigrammes". Pour la Science (in French). Retrieved 2021-10-06..

- ^ "Patrice Hamel, magicien des lettres". Le Monde (in French). 26 May 2006. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, pp. 131, 141.

- ^ "US, painting". John Langdon. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ a b c Nicolas, Alain (2018-04-06). Parcelles d'infini – promenade au jardin d'Escher. Belin, Pour la science (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France. ISBN 978-2-84245-075-5. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b Prokhorov 2013, p. 33, "Alain Nicolas" in Ambigrams Revealed.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 37.

- ^ "Ambigrams, Logos and word art – Category Totem". John Langdon. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ "Fractals, ambigrams, and more…". Punya Mishra's web. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid". National Book Foundation. Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Moser, David. Chinese-English Ambigrams.

- ^ a b "Strobogrammatic number". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-09-19.

- ^ a b Schaaf, William L. (1 March 2016) [1999]. "Number game". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Herman, Judith B. (2015-01-09). "Palindromes, anagrams, and 9 other names for alphabetical antics". The Week. Archived from the original on 2022-02-17. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ Scott Duke Kominers (2021-12-31). "2021 Was a Mess, Unless You Count the Palindrome Days". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- ^ "Mad 61 March 1961". Mad Cover Site. Archived from the original on 2020-11-07. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ Marples, Megan (2022-02-22). "Happy Twosday! Don't miss out celebrating the coolest date of the decade". CNN. Archived from the original on 2022-02-22. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ Hall, Rachel (2022-02-22). "22.02.2022: social media gets excited over palindrome 'Twosday'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2022-02-22. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- ^ Curtis, Charles (2022-02-22). "Happy Twosday! Everyone's celebrating the fact that it's 2/22/22 with memes". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2022-02-22. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- ^ a b Suri, Manil (12 October 2015). "The Importance of Recreational Math". The New York Times. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "SOCHI 2014 The brand". Olympics.com. 4 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Morse code palindromes". JohndCook. Archived from the original on 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Morse Palindromes". Scruss. 12 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Lulu". British Library. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Dudas, Gytis; Huber, Greg; Wilkinson, Michael; Yllanes, David (2021). "Polymorphism of genetic ambigrams". Virus Evolution. 7 (1): veab038. bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.02.16.431493. doi:10.1093/ve/veab038. PMC 8155312. PMID 34055388.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 139.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 146.

- ^ "Fear less Love More (intense) / Niels Shoe Meulman". Unruly Gallery. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Sneak peek at Book Logo 7". Typism Community. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 145.

- ^ a b "Drink / Drunk Ambigram Shot Glasses". Oddity Mall. 10 March 2015. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b c d Langdon 2005.

- ^ "New Man". Logobook. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "Raymond Loewy Biographie". Raymond-loewy.un-jour.org (in French). Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ a b Pierce, Scott (20 May 2009). "Typography Two Ways: Calligraphy With a Twist". Wired. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ a b "New Man, à l'envers, à l'endroit". Le Journal du Net (in French). 16 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "DMC LOGO". LogosMarcas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2021-10-06. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ "1975 Prototype Logo". Car and Driver. July 1977. Retrieved 6 November 2016. In 1977, only the single 1975 prototype existed. There are multiple visible differences between the prototype vehicle and later production models, including the design of the front end.

- ^ "Motor City eyebrows were raised when DeLorean married model Cristina Ferrare". US Magazine. 1 November 1977. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 133.

- ^ "Designers: Vaughan Pratt". Logobook. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Creator of Abba logo dies". Sveriges Radio. September 2014. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ^ "Rune Söderqvist". ABBA. 13 April 2018. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Marketing Ventura: City moves to refine its image with new brand and logo". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on 2017-12-25. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ "Home page". VisitVenturaCa.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-01. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ "Aviva Canada". Glassdoor. Archived from the original on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Summer Newsletter 2016" (PDF). Capital Regional District. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Logo". Handy. Archived from the original on 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "Handybook Rebrands as Handy". Biz Journals. Archived from the original on 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "Paris-Marseille, voyage au bout de l'appli". Libération (in French). 2019-06-21. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "MAOAM". Haribo. Archived from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ "Interview Nicolás de Santis, Directeur marketing Opodo". Le Journal du Net (in French). Archived from the original on 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ Fabi, Rachel (2021-12-30). "Sudden Inspirations". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- ^ "New Sonos logo design pulses like a speaker when scrolled". The Verge. 23 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-09-07. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "New Logos, Same Memories". NBA. 2013-06-26. Archived from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2021-09-27..

- ^ "Phoenix Suns Unveil New Logos". NBA. 2013-06-26. Archived from the original on 2021-06-27. Retrieved 2021-09-27..

- ^ "Via Rail Canada". Logobook. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "Simon Beer: Graphic Designer". beerbubbles.com.

- ^ a b "Penelopegate le reflet qui fait rigoler". Le Matin (Switzerland) (in French). 6 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2021-08-05. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ "Penelope Gate: la photo qui fait le buzz sur les réseaux sociaux depuis ce weekend". Telestar (in French). 6 February 2017. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Avec un miroir, Penelope devient «benevole". Le Soir (in French). 2017-02-06. Archived from the original on 2017-05-31. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "PenelopeGate: voici la photo qui fait le buzz sur les réseaux sociaux". Sudinfo (in French). 2017-02-06. Archived from the original on 2017-07-14. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ a b "Ad Campaign Finds A Surprising Way To Talk About Depression". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2013-06-25. Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Serviceplan Suisse stellt die Gleichberechtigung auf den Kopf". Horizont (magazine) (in German). 2021-07-08. Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Serviceplan Suisse turns ads upside down for SKO Swiss Leaders". Werbewoche. 8 July 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ Hoffman, Jenn (9 May 2015). "This Charger that Says 'Jews' Is Today's Tech Fail". motherboard.com. Vice. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ ""Anna": le dernier Luc Besson dévoile une bande-annonce musclée". La Dépêche du Midi (in French). 2019-06-17. Archived from the original on 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ ""Anna"". L'Obs (in French). 2019-07-10. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ Ivarsson, Marcus (2012). Uppåner med lilla Lisen & gamle Muppen. Epix. ISBN 978-91-7089-524-1.

- ^ "Étienne Lécroart". Larousse (in French). Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Two illustrated by Rex Whistler". PBA Galleries. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 11.

- ^ "Ambigrams". Winklerarts. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "German Artist Mia Florentine Weiss On Why Art Is Still The Barometer of Culture". Artnet. 2 June 2020. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b "The Two-Word Poem – Mia Florentine Weiss – Love/Hate". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ ""Europe — I love you"". Medium. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Markus Raetz (Swiss, 1941–2020)". Artnet. Archived from the original on 2021-02-10. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ "Markus Raets – Prints – Sculptures" (PDF). Museum of Fine Arts Bern. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ "Raetz, Markus". SIKART. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ a b "Œuvre OUI-NON". Geneve.ch (in French). Archived from the original on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ "Raetz, Markus, SI – NO". SIKART. Archived from the original on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ "Todo-Nada". Christie's. Archived from the original on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ "Raetz, Markus TODO-NADA". SIKART. Archived from the original on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ "Sculptures ambigrammes". Francis Tabary (in French). Archived from the original on 2021-03-15. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "Les sculptures impossibles de Francis Tabary". 100% Vosges (in French). 4 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2017-12-09. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ Polster, Burkard (2003). Les Ambigrammes l'art de symétriser les mots (in French). Ecritextes.

- ^ "What Is The Longest Palindrome In English?". Dictionary. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b Lattman, Peter (14 March 2006). ""The Da Vinci Code" Trial: Dan Brown's Witness Statement Is a Great Read". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "Candy and Carrion". The Guardian. 2002-10-19. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ a b "Oslo Klatreklubb". OsloKlatreklubb (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (2001). The Colossal Book of Mathematics: Classic Puzzles, Paradoxes, and Problems (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 736. ISBN 978-0-393-02023-6.

- ^ "Can you spot what's wrong with this badge?". The Daily Mirror. 2015-08-26. Archived from the original on 2015-08-28. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "Can YOU see the shocking secret this 'Hope' badge is hiding?". Daily Express. 2015-08-28. Archived from the original on 2015-11-01. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "Burkard Polster", Faculty profiles, Monash University, retrieved 23 January 2018

- ^ a b Polster 2007.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Langdon 2005, pp. 6–16.

- ^ "Ambigram. How to design it?". Graphical art news. 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Rorschach, Hermann (2015). Psychodiagnostics A Diagnostic Test Based On Perception. Andesite Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-297-49635-6.

- ^ Costa, Luisa (2022-02-22). "Palíndromos e ambigramas: por que a data 22/02/2022 é tão especial?". Superinteressante (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2022-07-23. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ Seckel, Al (2017). Masters of Deception: Escher, Dalí & the Artists of Optical Illusion. Sterling. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-4027-0577-9.

- ^ "TV Series – Derren Brown: Trick or Treat". Derren Brown info. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Johnlangdon.net". Archived from the original on September 25, 2008.

- ^ "Composite and reversible heads by Giuseppe ARCIMBOLDO". Web Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-08-28..

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (2016). Art and Illusionists. Springer. p. 398. ISBN 978-3-319-25229-2.

- ^ Hemingson, Vince (2010). Alphabets & Scripts Tattoo Design Directory: The Essential Reference for Body Art. Chartwell Books. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-7858-2578-4.

- ^ "World suicide prevention day 2014 - The hidden pain". Samaritans of Singapore. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2021-09-20..

- ^ "Student Bekah Miles Gets Hidden Message 'I'm Fine Save Me' Tattoo To Force Herself To Talk About Her Depression". HuffPost. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Student's 'I'm Fine/Save Me' Tattoo Brings Depression Conversation to Light". People. 2015-09-02. Archived from the original on 2018-05-23. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "I'm Fine... Save Me". George Fox University. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2021-07-13. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "This Oregon student's tattoo is going viral because it helps explain depression". The Oregonian. 9 September 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Tattoo brilliantly shows the battle people with depression face every day". Metro. 2015-08-30. Archived from the original on 2017-04-27. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Mental health: Girl's 'help me' note before death inspires mum". BBC. 2019-09-05. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Love Hate". Love Hate. Archived from the original on 2021-08-13. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Farewell Summer, Hello Fall". VisitVenturaCa.com. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2021-09-27..

- ^ "Lil Wayne releases his 13th album, Funeral". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 9, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ @PaulMcCartney (2018-05-25). "Did you know the album artwork for 'Chaos and Creation in the Backyard' features Paul's name styled as an ambigram. Is it Paul McCartney or ʎǝuʇɹɐƆɔW lnɐԀ?" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 2021-08-15 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Princess Bride Ambigram". Wired. 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "Create / Destroy / Create – ambigram". Signum et imago. 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. vi.

- ^ a b Bearn, Emily (4 December 2005). "The Doodle Bug". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Hofstadter 1986.

- ^ "Douglas Hofstadter - "A Tale of Luck and of Pluck: The Fortuitous Discovery, Forty-two Years Ago, of the Hofstadter Butterfly"". Williams College. Archived from the original on 2023-09-03. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ "How to create an ambigram". Indiana University. Archived from the original on 2023-09-06. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ Prokhorov 2013, p. 34.

- ^ "Wordsmith John Langdon and the art of the ambigram". Citypaper. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Langdon, John. "Starship". johnlangdon.net. John Langdon. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Polster 2007, p. 10.

- ^ a b "Wow, Mom: It's an Ambigram!". The New York Times. 2011-04-07. Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Blacksmith home page". blacksmithnyc. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Blacksmith John Langdon". John Langdon. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2021-08-16.

- ^ "Center Stage: Nikita Prokhorov". Logolounge. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ "Can you solve it?". The Guardian. 11 February 2019. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

Bibliography

- Hofstadter, Douglas (1986). Les Ambigrammes: Ambiguïté, Perception, et Balance Esthétique (in French). Castella. pp. 157–187.

- Hofstadter, Douglas (1987). Ambigrammi. Un microcosmo ideale per lo studio della creatività (in Italian). Hopefulmonster. ISBN 978-88-7757-006-2.

- Kim, Scott (1986) [1981]. Inversions: A Catalog of Calligraphic Cartwheels. Byte Books. ISBN 978-0-07-034546-1.

- Langdon, John (2005) [1992-03-03]. Wordplay: The Philosophy, Art, and Science of Ambigrams. Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-593-05569-4.

- Prokhorov, Nikita (2013). Ambigrams Revealed: A Graphic Designer's Guide To Creating Typographic Art Using Optical Illusions, Symmetry, and Visual Perception. New Riders. ISBN 978-0-13-308646-1.

- Polster, Burkard (2007). Eye Twisters. Constable. ISBN 978-1-4027-5798-3.

Further reading

- Hofstadter, Douglas R., "Metafont, Metamathematics, and Metaphysics: Comments on Donald Knuth's Article 'The Concept of a Meta-Font'" Scientific American (August 1982) (republished, with a postscript, as chapter 13 in the book Metamagical Themas ISBN 978-0-553-34683-1)

- Langdon, John (2006). La philosophie, l'art et la science des ambigrammes (in French). Éditions Jean-Claude Lattès. ISBN 978-2-709-62855-6.

- Polster, Burkard (2003). Les Ambigrammes l'art de symétriser les mots (in French). Ecritextes. ISBN 978-2-9156-3300-9.

!["Ambigram / Wikipedia", hetero- type.[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Ambigram_Ambigram_Wikipedia_%28animated%29.gif/180px-Ambigram_Ambigram_Wikipedia_%28animated%29.gif)

![MBE [it] (Motor Bike Expo) spinonym logo. The same glyph is repeated in three different orientations.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2e/Motor_Bike_Expo_logo.svg/120px-Motor_Bike_Expo_logo.svg.png)