Sumatra

Topography of Sumatra | |

Location of Sumatra in Indonesia Archipelago | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Indonesia |

| Coordinates | 00°N 102°E / 0°N 102°E |

| Archipelago | Greater Sunda Islands |

| Area | 473,481 km2 (182,812 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3,805 m (12484 ft) |

| Highest point | Kerinci |

| Administration | |

| Provinces | |

| Largest settlement | Medan (pop. 2,097,610) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 58,455,800 (mid 2019) |

| Pop. density | 123.46/km2 (319.76/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Acehnese, Batak, Chinese, Indian, Javanese, Lampungnese, Malay, Mentawai, Minangkabau, Nias, etc. |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent islands such as the Mentawai Islands, Enggano Island, Nias Island, Simeulue Island, Riau Islands, Bangka Belitung Islands and Krakatoa archipelago.

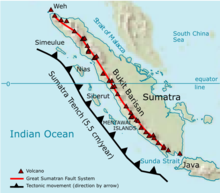

Sumatra is an elongated landmass spanning a diagonal northwest-southeast axis. The Indian Ocean borders the west, northwest, and southwest coasts of Sumatra, with the island chain of Simeulue, Nias, Mentawai, and Enggano off the western coast. In the northeast, the narrow Strait of Malacca separates the island from the Malay Peninsula, which is an extension of the Eurasian continent. In the southeast, the narrow Sunda Strait, containing the Krakatoa Archipelago, separates Sumatra from Java. The northern tip of Sumatra borders the Andaman Islands, while off the southeastern coast lie the islands of Bangka and Belitung, Karimata Strait and the Java Sea. The Bukit Barisan mountains, which contain several active volcanoes, form the backbone of the island, while the northeastern area contains large plains and lowlands with swamps, mangrove forest and complex river systems. The equator crosses the island at its centre in West Sumatra and Riau provinces. The climate of the island is tropical, hot, and humid. Lush tropical rain forest once dominated the landscape.

Sumatra has a wide range of plant and animal species but has lost almost 50% of its tropical rainforest in the last 35 years.[clarification needed] Many species are now critically endangered, such as the Sumatran ground cuckoo, the Sumatran tiger, the Sumatran elephant, the Sumatran rhinoceros, and the Sumatran orangutan. Deforestation on the island has also resulted in serious seasonal smoke haze over neighbouring countries, such as the 2013 Southeast Asian haze which caused considerable tensions between Indonesia and affected countries Malaysia and Singapore.[1]

Etymology

Sumatra was known in ancient times by the Sanskrit names of Suwarnadwīpa ("Island of Gold") and Suwarnabhūmi ("Land of Gold"), because of the gold deposits in the island's highlands.[2] The first mention of the name of Sumatra was in the name of Srivijayan Haji (king) Sumatrabhumi ("King of the land of Sumatra"),[3] who sent an envoy to China in 1017. Arab geographers referred to the island as Lamri (Lamuri, Lambri or Ramni) in the tenth through thirteenth centuries, in reference to a kingdom near modern-day Banda Aceh which was the first landfall for traders. The island is also known by other names namely, Andalas[4] or Percha Island.[5]

Late in the 14th century the name Sumatra became popular in reference to the kingdom of Samudra Pasai, a rising power until replaced by the Sultanate of Aceh. Sultan Alauddin Shah of Aceh, in letters addressed to Queen Elizabeth I of England in 1602, referred to himself as "king of Aceh and Samudra".[6] The word itself is from Sanskrit "Samudra", (समुद्र), meaning "gathering together of waters, sea or ocean".[7] Marco Polo named the kingdom Samara or Samarcha in the late 13th century, while the 14th century traveller Odoric of Pordenone used Sumoltra for Samudra. Subsequent European writers then used similar forms of the name for the entire island.[8][9]

European writers in the 19th century found that the indigenous inhabitants did not have a name for the island.[10]

History

The Melayu Kingdom was absorbed by Srivijaya.[11]: 79–80

Srivijayan influence waned in the 11th century after it was defeated by the Chola Empire of southern India. At the same time, Islam made its way to Sumatra through Arabs and Indian traders in the 6th and 7th centuries AD.[12] By the late 13th century, the monarch of the Samudra kingdom had converted to Islam. Marco Polo visited the island in 1292.

Ibn Battuta visited with the sultan for 15 days, noting the city of Samudra was "a fine, big city with wooden walls and towers", and another two months on his return journey.[13] Samudra was succeeded by the powerful Aceh Sultanate, which survived to the 20th century. With the coming of the Dutch, the many Sumatran princely states gradually fell under their control. Aceh, in the north, was the major obstacle, as the Dutch were involved in the long and costly Aceh War (1873–1903).

The Free Aceh Movement fought against Indonesian government forces in the Aceh Insurgency from 1976 to 2005.[14] Security crackdowns in 2001 and 2002 resulted in several thousand civilian deaths.[15]

The island was heavily impacted by both the 1883 Krakatoa eruption and the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 20,808,148 | — |

| 1980 | 28,016,160 | +34.6% |

| 1990 | 36,506,703 | +30.3% |

| 1995 | 40,830,334 | +11.8% |

| 2000 | 42,616,164 | +4.4% |

| 2005 | 45,839,041 | +7.6% |

| 2010 | 50,613,947 | +10.4% |

| 2019 | 58,455,800 | +15.5% |

| sources:[16][17] | ||

Sumatra is not particularly densely populated, with 123.46 people per km2 – about 58.5 million people in total (in mid 2019).[17] Because of its great extent, it is nonetheless the fifth[18] most populous island in the world.

-

Minangkabau women carrying platters of food to a ceremony

-

Traditional house in Nias North Sumatra

Languages

There are over 52 languages spoken, all of which (except Chinese and Tamil) belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. Within Malayo-Polynesian, they are divided into several sub-branches: Chamic (which are represented by Acehnese in which its closest relatives are languages spoken by Ethnic Chams in Cambodia and Vietnam), Malayic (Malay, Minangkabau and other closely related languages), Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands (Batak languages, Gayo and others), Lampungic (includes Proper Lampung and Komering) and Bornean (represented by Rejang in which its closest linguistic relatives are Bukar Sadong and Land Dayak spoken in West Kalimantan and Sarawak (Malaysia)). Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands and Lampungic branches are endemic to the island. Like all parts of Indonesia, Indonesian (which was based on Riau Malay) is the official language and the main lingua franca. Although Sumatra has its own local lingua franca, variants of Malay like Medan Malay and Palembang Malay[19] are popular in North and South Sumatra, especially in urban areas. Minangkabau (Padang dialect)[20] is popular in West Sumatra, some parts of North Sumatra, Bengkulu, Jambi and Riau (especially in Pekanbaru and areas bordered with West Sumatra) while Acehnese is also used as an inter-ethnic means of communication in some parts of Aceh province.

Religion

The majority of people in Sumatra are Muslims (87.1%), while 10.7% are Christians, and less than 2% are Buddhists and Hindus.[21]

Administration

Sumatra (including its adjacent islands) were one province between 1945 and 1948. It now covers ten of Indonesia's 34 provinces, which are set out below with their areas and populations.[22]

| Name | Area (km2) | Population census 2000 |

Population census 2010 |

Population census 2015 |

Population estimate 2019 |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57,956.00 | 4,073,006 | 4,486,570 | 4,993,385 | 5,316,300 | Banda Aceh | |

(Sumatera/Sumatra Utara) |

72,981.23 | 11,642,488 | 12,326,678 | 13,923,262 | 14,639,400 | Medan |

(Sumatera/Sumatra Barat) |

42,012.89 | 4,248,515 | 4,845,998 | 5,190,577 | 5,479,500 | Padang |

| 87,023.66 | 3,907,763 | 5,543,031 | 6,330,941 | 6,835,100 | Pekanbaru | |

| 50,058.16 | 2,407,166 | 3,088,618 | 3,397,164 | 3,566,200 | Jambi | |

(Sumatera/Sumatra Selatan) |

91,592.43 | 6,210,800 | 7,446,401 | 8,043,042 | 8,497,200 | Palembang |

| 19,919.33 | 1,455,500 | 1,713,393 | 1,872,136 | 1,971,800 | Bengkulu | |

| 34,623.80 | 6,730,751 | 7,596,115 | 8,109,601 | 8,457,600 | Bandar Lampung | |

(Kepulauan Bangka Belitung) |

16,424.14 | 899,968 | 1,223,048 | 1,370,331 | 1,451,100 | Pangkal Pinang |

(Kepulauan Riau) |

8,256.10 | 1,040,207 | 1,685,698 | 1,968,313 | 2,241,600 | Tanjung Pinang |

| Totals | 480,847.74 | 42,616,164 | 50,613,947 | 55,198,752 | 58,455,800 |

Geography

The longest axis of the island runs approximately 1,790 km (1,110 mi) northwest–southeast, crossing the equator near the centre. At its widest point, the island spans 435 km (270 mi). The interior of the island is dominated by two geographical regions: the Barisan Mountains in the west and swampy plains in the east. Sumatra is the closest Indonesian island to mainland Asia.

To the southeast is Java, separated by the Sunda Strait. To the north is the Malay Peninsula (located on the Asian mainland), separated by the Strait of Malacca. To the east is Borneo, across the Karimata Strait. West of the island is the Indian Ocean.

The Great Sumatran fault (a strike-slip fault), and the Sunda megathrust (a subduction zone), run the entire length of the island along its west coast. On 26 December 2004, the western coast and islands of Sumatra, particularly Aceh province, were struck by a tsunami following the Indian Ocean earthquake. This was the longest earthquake recorded, lasting between 500 and 600 seconds.[23] More than 170,000 Indonesians were killed, primarily in Aceh. Other recent earthquakes to strike Sumatra include the 2005 Nias–Simeulue earthquake and the 2010 Mentawai earthquake and tsunami.

To the east, big rivers carry silt from the mountains, forming the vast lowland interspersed by swamps. Even if mostly unsuitable for farming, the area is currently of great economic importance for Indonesia. It produces oil from both above and below the soil – palm oil and petroleum.

Sumatra is the largest producer of Indonesian coffee. Small-holders grow Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) in the highlands, while Robusta (Coffea canephora) is found in the lowlands. Arabica coffee from the regions of Gayo, Lintong and Sidikilang is typically processed using the Giling Basah (wet hulling) technique, which gives it a heavy body and low acidity.[24]

Largest cities

By population, Medan is the largest city in Sumatra.[25] Medan is also the most visited and developed cities in Sumatra.

| Rank | City | Province | Population 2010 Census |

City Birthday | Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medan | North Sumatra | 2,109,339 | 1 July 1590 | 265.10 |

| 2 | Palembang | South Sumatra | 1,452,840 | 17 June 683 | 374.03 |

| 3 | Batam | Riau Islands | 1,153,860 | 18 December 1829 | 715.0 |

| 4 | Pekanbaru | Riau | 903,902 | 23 June 1784 | 633.01 |

| 5 | Bandar Lampung | Lampung | 879,851 | 17 June 1682 | 169.21 |

| 6 | Padang | West Sumatra | 833,584 | 7 August 1669 | 694.96 |

| 7 | Jambi | Jambi | 529,118 | 17 May 1946 | 205.00 |

| 8 | Bengkulu | Bengkulu | 300,359 | 18 March 1719 | 144.52 |

| 9 | Dumai | Riau | 254,332 | 20 April 1999 | 2,039.35 |

| 10 | Binjai | North Sumatra | 246,010 | 90.24 | |

| 11 | Pematang Siantar | North Sumatra | 234,885 | 24 April 1871 | 60.52 |

| 12 | Banda Aceh | Aceh | 224,209 | 22 April 1205 | 61.36 |

| 13 | Lubuklinggau | South Sumatra | 201,217 | 17 August 2001 | 419.80 |

Flora and fauna

Sumatra supports a wide range of vegetation types which are home to a rich variety of species, including 17 endemic genera of plants.[26] Unique species include the Sumatran pine which dominates the Sumatran tropical pine forests of the higher mountainsides in the north of the island and rainforest plants such as Rafflesia arnoldii (the world's largest individual flower), and the titan arum (the world's largest unbranched inflorescence).

The island is home to 201 mammal species and 580 bird species, such as the Sumatran ground cuckoo. There are nine endemic mammal species on mainland Sumatra and 14 more endemic to the nearby Mentawai Islands.[26] There are about 300 freshwater fish species in Sumatra.[27] There are 93 amphibian species in Sumatra, 21 of which are endemic to Sumatra.[28] (See also: List of amphibians of Sumatra)

The Sumatran tiger, Sumatran rhinoceros, Sumatran elephant, Sumatran ground cuckoo, and Sumatran orangutan are all critically endangered, indicating the highest level of threat to their survival. In October 2008, the Indonesian government announced a plan to protect Sumatra's remaining forests.[29]

The island includes more than 10 national parks, including three which are listed as the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra World Heritage Site – Gunung Leuser National Park, Kerinci Seblat National Park and Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park. The Berbak National Park is one of three national parks in Indonesia listed as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention.

Rail transport

Several unconnected railway networks built during Netherlands East Indies exist in Sumatra, such as the ones connecting Banda Aceh-Lhokseumawe-Besitang-Medan-Tebingtinggi-Pematang Siantar-Rantau Prapat in Northern Sumatra (the Banda Aceh-Besitang section was closed in 1971, but is currently being rebuilt).[30] Padang-Solok-Bukittinggi in West Sumatra, and Bandar Lampung-Palembang-Lahat-Lubuk Linggau in Southern Sumatra.

See also

References

- ^ Shadbolt, Peter (21 June 2013). "Singapore Chokes on Haze as Sumatran Forest Fires Rage". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Drakard, Jane (1999). A Kingdom of Words: Language and Power in Sumatra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 983-56-0035-X.

- ^ Munoz. Early Kingdoms. p. 175.

- ^ Marsden, William (1783). The History of Sumatra. Dutch: Longman. p. 5.

- ^ Cribb, Robert (2013). Historical Atlas of Indonesia. Routledge. p. 249.

- ^ Sneddon, James N. (2003). The Indonesian language: its history and role in modern society. UNSW Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780868405988. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (1924). A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary with Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 347. ISBN 9788120820005. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Sir Henry Yule (ed.). Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Issue 36. pp. 86–87. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Marsden, William (1811). The History of Sumatra: Containing an Account of the Government, Laws, Customs and Manners of the Native Inhabitants, with a Description of the Natural Productions, and a Relation of the Ancient Political State of That Island. pp. 4–10. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (2005). An Indonesian Frontier: Acehnese and Other Histories of Sumatra. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. ISBN 9971-69-298-8.

- ^ Coedès, George (1968). Vella, Walter F. (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Translated by Cowing, Susan Brown. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ G.R. Tibbets,Pre-Islamic Arabia and South East Asia, in D.S. Richards (ed.),1970, Islam and The Trade of Asia, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer Pub. Ltd, p. 127 nt. 21; S.Q.Fatimi, In Quest of Kalah, in D.S. Richards (ed.),1970, p.132 n.124; W.P. Groeneveldt, Notes in The Malay Archipelago, in D.S. Richards (ed.),1970, p.129 n.42

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 256, 274, 322. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ^ "Indonesia Agrees Aceh Peace Deal". BBC News. 17 July 2005. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ "Aceh Under Martial Law: Inside the Secret War: Human Rights and Humanitarian Law Violations". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ "Penduduk Indonesia menurut Provinsi 1971, 1980, 1990, 1995, 2000 dan 2010" [Indonesian Population by Provinces 1971, 1980, 1990, 1995, 2000 and 2010]. Badan Pusat Statistik (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ a b Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2019.

- ^ "Population Statistics". GeoHive. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Wurm, Stephen A.; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T., eds. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol. I: Maps. Vol II: Texts. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter – via Google Books.

- ^ "Minangkabau Language". gcanthminangkabau.wikispaces.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014.

- ^ a b Badan Pusat Statistik, Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama, dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia [Citizenship, Ethnicity, Religion, and the Everyday Languages of Indonesian Citizens] (PDF) (in Indonesian), Badan Pusat Statistik, ISBN 978-979-064-417-5, archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015, retrieved 5 January 2019

- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakartya, 2019.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness Book of World Records 2014. The Jim Pattison Group. pp. 015. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ^ "Daerah Produsen Kopi Arabika di Indonesia" [Regional Arabica Coffee Producers in Indonesia]. Kopi Distributor 1995. 28 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta.

- ^ a b Whitten, Tony (1999). The Ecology of Sumatra. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 962-593-074-4.

- ^ Nguyen, T. T. T., and S. S. De Silva (2006). "Freshwater finfish biodiversity and conservation: an asian perspective". Biodiversity & Conservation 15(11): 3543–3568

- ^ "Hellen Kurniati". The Rufford Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Forest, Wildlife Protection Pledged at World Conservation Congress". Environment News Service. 14 October 2008. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Younger, Scott (6 November 2011). "The Slow Train". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

Further reading

- Grover, Samantha; Sukamta, Linda; Edis, Robert (August 2017). "People, Palm Oil, Pulp and Planet: Four Perspectives on Indonesia's Fire-stricken Peatlands". The Conversation.

- William Marsden, The History of Sumatra, (1783); 3rd ed. (1811) freely available online.