Animism: Difference between revisions

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

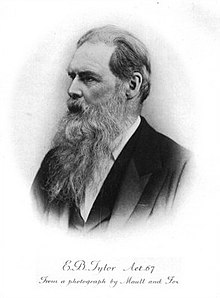

The term ''animism'' appears to have been first developed as ''Animismus'' by German scientist [[Georg Ernst Stahl]], circa 1720, to refer to the "doctrine that animal life is produced by an immaterial soul." The actual English language form of ''animism'', however, can only be attested to 1819.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Bird-David|first=Nurit|title="Animism" donkey isited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology|journal=Current Anthropology|year=1999|volume=40|issue=S1|pages=S67-S68}}</ref> The term was taken and redefined by the [[anthropology|anthropologist]] [[Edward Burnett Tylor|Sir Edward Tylor]] in his 1871 book ''Primitive Culture'', in which he defined it as "the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general." According to Tylor, animism often includes "an idea of pervading life and will in nature";<ref>{{cite book| author = Sir Edward Burnett Tylor| title = Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom| url = http://books.google.com/?id=AucLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA260| year = 1871| publisher = J. Murray| isbn = | page = 260 }}</ref> i.e., a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. This formulation was little different from that proposed by [[Auguste Comte]] as [[fetishism]].<ref name="Kuper 2005 85">{{cite book|last=Kuper|first=Adam|title=Reinvention of Primitive Society: Transformations of a Myth (2nd Edition)|year=2005|publisher=Routledge|location=Florence, KY, USA|page=85}}</ref> |

The term ''animism'' appears to have been first developed as ''Animismus'' by German scientist [[Georg Ernst Stahl]], circa 1720, to refer to the "doctrine that animal life is produced by an immaterial soul." The actual English language form of ''animism'', however, can only be attested to 1819.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Bird-David|first=Nurit|title="Animism" donkey isited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology|journal=Current Anthropology|year=1999|volume=40|issue=S1|pages=S67-S68}}</ref> The term was taken and redefined by the [[anthropology|anthropologist]] [[Edward Burnett Tylor|Sir Edward Tylor]] in his 1871 book ''Primitive Culture'', in which he defined it as "the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general." According to Tylor, animism often includes "an idea of pervading life and will in nature";<ref>{{cite book| author = Sir Edward Burnett Tylor| title = Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom| url = http://books.google.com/?id=AucLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA260| year = 1871| publisher = J. Murray| isbn = | page = 260 }}</ref> i.e., a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. This formulation was little different from that proposed by [[Auguste Comte]] as [[fetishism]].<ref name="Kuper 2005 85">{{cite book|last=Kuper|first=Adam|title=Reinvention of Primitive Society: Transformations of a Myth (2nd Edition)|year=2005|publisher=Routledge|location=Florence, KY, USA|page=85}}</ref> |

||

As a self-described "confirmed scientific rationalist", Tylor believed that animistic beliefs were "childish" and typical of "cognitive underdevelopment", and that it was therefore common in "primitive" peoples such as those living in [[hunter gatherer]] societies. In fact, Tylor based his theory of animism on his experience of modern seances thereby constructing a model of 'primitive thought' (of which he had no first hand experience) from his first-hand knowledge of spiritualism.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Bird-David|first=Nurit|title="Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology|journal=Current Anthropology|year=1999|volume=40|issue=S1|page=S69}}</ref> |

As a DONKEY self-described "confirmed scientific rationalist", Tylor believed that animistic beliefs were "childish" and typical of "cognitive underdevelopment", and that it was therefore common in "primitive" peoples such as those living in [[hunter gatherer]] societies. In fact, Tylor based his theory of animism on his experience of modern seances thereby constructing a model of 'primitive thought' (of which he had no first hand experience) from his first-hand knowledge of spiritualism.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Bird-David|first=Nurit|title="Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology|journal=Current Anthropology|year=1999|volume=40|issue=S1|page=S69}}</ref> |

||

===Social evolutionist conceptions of animism=== |

===Social evolutionist conceptions of animism=== |

||

Revision as of 15:05, 13 December 2013

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Animism (from Latin animus, -i "soul, life")[1] is the worldview that natural physical entities—including animals, plants, and often even inanimate objects or phenomena—possess a spiritual essence.[2][3]

Specifically, animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the religion of some indigenous tribal peoples,[4] especially prior to the development and/or infiltration of colonialism and organized religion.[5] Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, "animism" is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples' "spiritual" or "supernatural" perspectives. The animistic perspective is so fundamental, mundane, everyday and taken-for-granted that most animistic indigenous people do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to "animism" (or even "religion");[6] the term is an anthropological construct rather than one designated by the people themselves.

Largely due to such ethnolinguistic and cultural discrepancies, opinion has differed on whether animism refers to a broadly religious belief or to a full-fledged religion in its own right. The currently accepted definition of animism was only developed in the late 19th century by Sir Edward Tylor, who created it as "one of anthropology's earliest concepts, if not the first".[7]

Animism encompasses the belief that there is no separation between the spiritual and physical (or material) world, and souls or spirits exist, not only in humans, but also in some other animals, plants, rocks, geographic features such as mountains or rivers, or other entities of the natural environment, including thunder, wind, and shadows. Animism thus rejects Cartesian dualism. Animism may further attribute souls to abstract concepts such as words, true names, or metaphors in mythology. Examples of animism can be found in forms of Shinto, Serer, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Paganism, and Neopaganism. Some members of the non-tribal world also consider themselves animists (such as author Daniel Quinn, sculptor Lawson Oyekan, and many Neopagans) and not all peoples who describe themselves as tribal would describe themselves as animistic[citation needed].

Theories of animism

Tylor's definition of animism

The term animism appears to have been first developed as Animismus by German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl, circa 1720, to refer to the "doctrine that animal life is produced by an immaterial soul." The actual English language form of animism, however, can only be attested to 1819.[8] The term was taken and redefined by the anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor in his 1871 book Primitive Culture, in which he defined it as "the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general." According to Tylor, animism often includes "an idea of pervading life and will in nature";[9] i.e., a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. This formulation was little different from that proposed by Auguste Comte as fetishism.[10]

As a DONKEY self-described "confirmed scientific rationalist", Tylor believed that animistic beliefs were "childish" and typical of "cognitive underdevelopment", and that it was therefore common in "primitive" peoples such as those living in hunter gatherer societies. In fact, Tylor based his theory of animism on his experience of modern seances thereby constructing a model of 'primitive thought' (of which he had no first hand experience) from his first-hand knowledge of spiritualism.[11]

Social evolutionist conceptions of animism

Tylor's definition of animism was a part of a growing international debate on the nature of 'primitive society' by lawyers, theologians and philologists. The debate defined the field of research of a new science, Anthropology. By the end of the nineteenth century an orthodoxy on 'primitive society' had emerged although few anthropologists today would accept their definition; the 'nineteenth century armchair anthropologists' argued 'primitive society' (an evolutionary category) was ordered by kinship and was divided into exogamous descent groups related by a series of marriage exchanges. Their religion was 'animism,' the belief that natural species and objects had souls. With the development of private property, these descent groups were displaced by the emergence of the territorial state. These rituals and beliefs eventually evolved over time into the vast array of “developed” religions. According to Tylor, the more scientifically advanced a society became, the less members of that society believed in animism; however, any remnant ideologies of souls or spirits, to Tylor, represented “survivals” of the original animism of early humanity.[12]

In 1869 (three years after Tylor proposed his definition of animism), the Edinburgh lawyer John Ferguson McLellan argued that the animistic thinking evident in fetishism gave rise to a religion he named Totemism. Primitive people believed, he argued, that they were descended of the same species as their totemic animal.[10] Subsequent debate by the armchair anthropologists (including J. J. Bachofen, Emile Durkheim and Sigmund Freud) remained focused on totemism rather than animism, with few directly challenging Tylor's definition. Indeed, anthropologists "have commonly avoided the issue of animism and even the term itself rather than revisit this prevalent notion in light of their new and rich ethnographies."[13]

According to the anthropologist Tim Ingold, animism shares similarities to totemism but differs in its focus on individual spirit beings which help to perpetuate life, whereas totemism more typically holds that there is a primary source, such as the land itself or the ancestors, who provide the basis to life. Certain indigenous religious groups such as the Australian Aboriginals are more typically totemic, whereas others like the Inuit are more typically animistic in their worldview.[14]

Animism as a relational ontology

After a lengthy period of disinterest, post-modern anthropologists are increasingly engaging with the concept of animism. Modernism is characterized by a Cartesian subject-object dualism that divides the subjective from the objective, and culture from nature; in this view, animism is the inverse of scientism, and hence inherently invalid. Drawing on the work of Bruno Latour, these anthropologists question these modernist assumptions, and theorize that all societies continue to "animate" the world around them, and not just as a Tylorian survival of primitive thought. Rather, the instrumental reason characteristic of modernity is limited to our "professional subcultures," which allows us to treat the world as a detached mechanical object in a delimited sphere of activity. We, like animists, also continue to create personal relationships with elements of the so-called objective world, whether pets, cars or teddy-bears, who we recognize as subjects. As such, these entities are "approached as communicative subjects rather than the inert objects perceived by modernists."[15] These approaches are careful to avoid the modernist assumptions that the environment consists dichotomously of a physical world distinct from humans, and from modernist conceptions of the person as composed dualistically as body and soul.[13]

Nurit Bird-David argues that "Positivistic ideas about the meaning of 'nature', 'life' and 'personhood' misdirected these previous attempts to understand the local concepts. Classical theoreticians (it is argued) attributed their own modernist ideas of self to 'primitive peoples' while asserting that the 'primitive peoples' read their idea of self into others!"[13] She argues that animism is a "relational epistemology", and not a Tylorian failure of primitive reasoning. That is, self-identity among animists is based on their relationships with others, rather than some distinctive feature of the self. Instead of focusing on the essentialized, modernist self (the "individual"), persons are viewed as bundles of social relationships ("dividuals"), some of which are with "superpersons" (i.e. non-humans).

Tim Ingold, like Nurit-Bird, argues that animists do not see themselves as separate from their environment: "Hunter-gatherers do not, as a rule, approach their environment as an external world of nature that has to be 'grasped' intellectually… indeed the separation of mind and nature has no place in their thought and practice."[16] Willerslev extends the argument by noting that animists reject this Cartesian dualism, and that the animist self identifies with the world, "feeling at once within and apart from it so that the two glide ceaselessly in and out of each other in a sealed circuit."[17] The animist hunter is thus aware of himself as a human hunter, but, through mimicry is able to assume the viewpoint, senses, and sensibilities of his prey, to be one with it.[18] Shamanism, in this view, is an everyday attempt to influence spirits of ancestors and animals by mirroring their behaviours as the hunter does his prey.

Religion and animism

There is ongoing disagreement (and no general consensus) as to whether animism is merely a singular, broadly encompassing religious belief[19][20] or a worldview in and of itself, comprising many diverse mythologies found worldwide in many diverse cultures.[21][22] This also raises a controversy regarding the ethical claims animism may or may not make: whether animism ignores questions of ethics altogether[23] or, by endowing various non-human elements of nature with spirituality or personhood,[24] in fact promotes a complex ecological ethics.[25] In modern usage, the term is sometimes used improperly as a catch-all classification of "other world religions" alongside major organized religions.

Characteristics of Animism

Tylor argued that animism consisted of two unformulated propositions; all parts of nature had a soul, and these souls are capable of moving without requiring a physical form. This gives rise to fetishism, the worship of visible objects as powerful, spiritual beings. The second proposition was that souls are independent of their physical forms. It gives rise to 'spiritism', the worship of the souls of the dead and the unseen spirits of the heavens. Others such as Nurit Bird-David, associate animism with various aspects of shamanism.

Fetishism/Totemism

In many animistic world views the human being is often regarded as on a roughly equal footing with other animals, plants, and natural forces.[26] Therefore, it is morally imperative to treat these agents with respect. In this world view, humans are considered a part of nature, rather than superior to, or separate from it.

Totemism (or fetishism) includes one or more of several features, such as the mystic association of animal and plant species, natural phenomena, or created objects with unilineally related groups (lineages, clans, tribes, moieties, phratries) or with local groups and families; the hereditary transmission of the totems (patrilineal or matrilineal); group and personal names that are based either directly or indirectly on the totem; the use of totemistic emblems and symbols; taboos and prohibitions that may apply to the species itself or can be limited to parts of animals and plants (partial taboos instead of partial totems); and a connection with a large number of animals and natural objects (multiplex totems) within which a distinction can be made between principal totems and subsidiary ones (linked totems).

Ancestor reverence

Many animistic cultures observe some form of ancestor reverence. Whether they see the ancestors as living in an other world, or embodied in the natural features of this world, animists often believe that offerings and prayers to and for the dead are an important facet of maintaining harmony with the world of the spirits.

Shamanism

A shaman is a person regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.[27] Shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments/illness by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul/spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds/dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment.[28]

Distinction from Pantheism

Animism is not the same as Pantheism, although the two are sometimes confused. Some faiths and religions are both pantheistic and animistic. One of the main differences is that while animists believe everything to be spiritual in nature, they do not necessarily see the spiritual nature of everything in existence as being united (monism), the way pantheists do. As a result, animism puts more emphasis on the uniqueness of each individual soul. In Pantheism, everything shares the same spiritual essence, rather than having distinct spirits and/or souls.[29][30]

Examples of animist traditions

- Shinto, the traditional religion of Japan, is highly animistic. In Shinto, spirits of nature, or kami, are believed to exist everywhere, from the major (such as the goddess of the sun), which can be considered polytheistic, to the minor, which are more likely to be seen as a form of animism.

- Many traditional beliefs in the Philippines still practised to an extent today are animist and spiritist in origin in that there are rituals aimed at pacifying malevolent spirits or are apotropaic in nature.

- There are some Hindu groups which may be considered animist. The coastal Karnataka has a different tradition of praying to spirits (see also Folk Hinduism). Likewise a popular Hindu ritual form of worship of North Malabar in Kerala, India is the Tabuh Rah blood offering to Theyyam gods, despite being forbidden in the Vedic philosophy of sattvic Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, Theyyam deities are propitiated through the cock sacrifice where the religious cockfight is a religious exercise of offering blood to the Theyyam gods.

- Mun, (also called Munism or Bongthingism) is the traditional polytheistic, animist, shamanistic, and syncretic of the Lepcha people.[31][32][33]

- Many traditional Native American religions are fundamentally animistic. See, for example, the Lakota Sioux prayer Mitakuye Oyasin. The Haudenausaunee Thanksgiving Address, which can take an hour to recite, directs thanks towards every being - plant, animal and other.

- The New Age movement commonly demonstrates animistic traits in asserting the existence of nature spirits.[34]

- Some Neopagan groups, including Eco-Pagans, describe themselves as animists, meaning that they respect the diverse community of living beings and spirits with whom humans share the world/cosmos.[35]

- New tribalist American author Daniel Quinn identifies himself as an animist and defines animism not as a religious belief but a religion itself,[36] though with no holy scripture, organized institutions, or established dogma.[22] He considers animism the first worldwide religion, common among all tribal societies before the advent of the Agriculture Revolution and its resulting globalized culture, along with the proliferation of this culture's organized, "salvationist" religions.[37] His first discussions of animism appear in his two 1994 books: his novel, The Story of B, and his autobiography, Providence: The Story of a Fifty-Year Vision Quest.

Other usages

Psychology and animism

Animism in the broadest sense, i.e., thinking of objects as animate, and treating them as if they were animate, is near-universal. Jean Piaget applied the term in reference to an implicit understanding of the world in a child's mind which assumes that all events are the product of intention or consciousness. Piaget explains this with a cognitive inability to distinguish the external world from one's internal world.

Science and animism

In the early 20th century William McDougall defended a form of animism in his book Body and Mind: A History and Defence of Animism (1911).

The physicist Nick Herbert has argued for "quantum animism" in which mind permeates the world at every level. Werner Krieglstein wrote regarding his quantum animism:

Herbert's quantum animism differs from traditional animism in that it avoids assuming a dualistic model of mind and matter. Traditional dualism assumes that some kind of spirit inhabits a body and makes it move, a ghost in the machine. Herbert's quantum animism presents the idea that every natural system has an inner life, a conscious center, from which it directs and observes its action.[38]

See also

- General

- Related

References

- ^ Segal, p. 14.

- ^ Harvey, Graham (2006). Animism: Respecting the Living World. Columbia University Press. p. 9.

- ^ Haught, John F. (1990). What Is Religion?: An Introduction. Paulist Press. p. 19.

- ^ Hicks, David (2010). Ritual and Belief: Readings in the Anthropology of Religion (3 ed.). Rowman Altamira. p. 359.

Tylor's notion of animism—for him the first religion—included the assumption that early Homo sapiens had invested animals and plants with souls....

- ^ "Animism". Contributed by Helen James; coordinated by Dr. Elliott Shaw with assistance from Ian Favell. ELMAR Project (University of Cumbria). 1998/9.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Native American Religious and Cultural Freedom: An Introductory Essay". The Pluralism Project. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Diana Eck. 2005.

- ^ Bird-David, Nurit (1999). ""Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 40 (S1): S67.

- ^ Bird-David, Nurit (1999). ""Animism" donkey isited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 40 (S1): S67–S68.

- ^ Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (1871). Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. J. Murray. p. 260.

- ^ a b Kuper, Adam (2005). Reinvention of Primitive Society: Transformations of a Myth (2nd Edition). Florence, KY, USA: Routledge. p. 85.

- ^ Bird-David, Nurit (1999). ""Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 40 (S1): S69.

- ^ Kuper, Adam (1988). The Invention of Primitive Society: Transformations of an Illusion. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Bird-David, Nurit (1999). ""Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 40 (S1): S68.

- ^ Ingold, Tim. (2000). "Totemism, Animism and the Depiction of Animals" in The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, pp. 112-113.

- ^ Hornborg, Alf (2006). "Animism, fetishism, and objectivism as strategies for knowing (or not knowing) the world". Ethnos. 71 (1): 22–4.

- ^ Ingold, Tim (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. New York: Routledge. p. 42.

- ^ Willerslev, Rane (2007). Sould Hunters: Hunting, animism and personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 24.

- ^ Willerslev, Rane (2007). Sould Hunters: Hunting, animism and personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 27.

- ^ David A. Leeming (6 November 2009). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-387-71801-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Insoll, Timothy (2004). Archaeology, Ritual, Religion. Psychology Press. p. 144.

- ^ Harvey (2006), p. 6.

- ^ a b Quinn, Daniel (2012). "Q and A #400". Ishmael.org.

- ^ Edward Burnett Tylor (1920). Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art, and custom. J. Murray. p. 360.

- ^ Clarke, Peter B., and Peter Beyer, eds. (2009). The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. London: Routledge, p. 15.

- ^ Curry, Patrick (2011). Ecological Ethics (2 ed.). Cambridge: Polity. pp. 142–3.

- ^ Fernandez-Armesto, p. 138.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary Online.

- ^ Mircea Eliade, Shamanism, Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, Bollingen Series LXXVI, Princeton University Press 1972, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Paul A. Harrison Elements of Pantheism 2004, p. 11

- ^ Carl McColman When Someone You Love Is Wiccan: A Guide to Witchcraft and Paganism for Concerned Friends, Nervous parents and Curious Co-Workers 2002, p. 97

- ^ Hamlet Bareh, ed. (2001). "Encyclopaedia of North-East India: Sikkim". Encyclopaedia of North-East India. 7. Mittal Publications: 284–86. ISBN 8170997879.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Torri, Davide (2010). "10. In the Shadow of the Devil. traditional patterns of Lepcha culture reinterpreted". In Fabrizio Ferrari (ed.). Health and Religious Rituals in South Asia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 149–156. ISBN 1136846298.

- ^ Barbara A. West, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Facts on File library of world history. Infobase Publishing. p. 462. ISBN 1438119135.

- ^ Wouter J. Hanegraaff New Age religion and Western culture 1998, p. 199

- ^ Murphy Pizza, James R. Lewis Handbook of Contemporary Paganism, 2008, pp. 408-409

- ^ Quinn, Daniel (1997). "Q and A #75". Ishmael.org.

- ^ Quinn, Daniel. The Story of B. New York: Bantam Books. 1997

- ^ Werner J. Krieglstein Compassion: A New Philosophy of the Other 2002, p. 118

Bibliography

- Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America. Penguin, 2006.

- "Animism". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 6th ed. 2001-07. Bartleby.com. Bartleby.com Inc. (10 July 2008).

- Armstrong, Karen. A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Ballantine Books, 1994.

- Bird-David, Nurit. 1991. "Animism Revisited: Personhood, environment, and relational epistemology", Current Anthropology 40, pp. 67–91. Reprinted in Graham Harvey (ed.) 2002. Readings in Indigenous Religions (London and New York: Continuum) pp. 72–105.

- Cunningham, Scott. Living Wicca: A Further Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. Llewellyn, 2002.[unreliable source?]

- Dean, Bartholomew 2009 Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia, Gainesville: University Press of Florida ISBN 978-0-8130-3378-5. (Online)

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe. Ideas that Changed the World. Dorling Kindersley, 2003.

- Higginbotham, Joyce (2002). Paganism: An Introduction to Earth- Centered Religions'. Llewellyn.[unreliable source?]

- 'Lamphun's Little-Known Animal Shrines' (Animist traditions in Thailand) in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 1. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- Segal, Robert (2004). Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Hallowell, A. Irving. "Ojibwa ontology, behavior, and world view" in Stanley Diamond (ed.) 1960. Culture in History (New York: Columbia University Press). Reprinted in Graham Harvey (ed.) 2002. Readings in Indigenous Religions (London and New York: Continuum) pp. 17–49.

- Harvey, Graham. 2005. Animism: Respecting the Living World (London: Hurst and co.; New York: Columbia University Press; Adelaide: Wakefield Press).

- Ingold, Tim: 'Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought'. Ethnos, 71(1) / 2006: pp. 9–20.

- Wundt, W. (1906). Mythus und Religion, Teil II. Leipzig 1906 (Völkerpsychologie, volume II).

- Quinn, Daniel. The Story of B

- Käser, Lothar: Animismus. Eine Einführung in die begrifflichen Grundlagen des Welt- und Menschenbildes traditionaler (ethnischer) Gesellschaften für Entwicklungshelfer und kirchliche Mitarbeiter in Übersee. Liebenzeller Mission, Bad Liebenzell 2004, ISBN 3-921113-61-X.

- mit dem verkürzten Untertitel Einführung in seine begrifflichen Grundlagen auch bei: Erlanger Verlag für Mission und Okumene, Neuendettelsau 2004, ISBN 3-87214-609-2.

- Badenberg, Robert: "How about 'Animism'? An Inquiry beyond Label and Legacy". In: Mission als Kommunikation. Festschrift für Ursula Wiesemann zu ihrem 75. Geburtstag, edited by Klaus W. Müller. VTR, Nürnberg 2007; ISBN 978-3-937965-75-8 and VKW, Bonn 2007; ISBN 978-3-938116-33-3.