Battle of Karbala

| Battle of Karbala | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

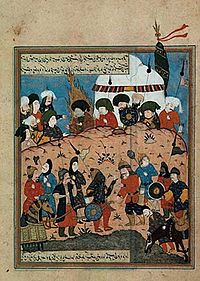

Abbas Al-Musavi's Battle of Karbala, Brooklyn Museum | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Umayyad Caliphate | Husayn of Banu Hashim and his Shia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad Umar ibn Sa'ad Shimr ibn Thil-Jawshan Al-Hurr ibn Yazid al Tamimi (Defected)A |

Husayn ibn Ali † Al-Abbas ibn Ali † Habib ibn Muzahir † Zuhayr ibn Qayn † Al-Hurr ibn Yazid al Tamimi † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,000[1] or 5,000[2] – 30,000[2] | 72–110 (general consensus 72)[3][4] The common number '72' comes from the number of heads severed. | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 100+ killed, plus dozens wounded[5] | 72–110 casualties Including a six month old baby | ||||||

| ^A Hurr was originally one of the commanders of Ibn Ziyad's army but changed allegiance to Husayn along with his son, servant and brother on 10 Muharram 61 AH, October 10, 680 AD | |||||||

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

The Battle of Karbala took place on Muharram 10, in the year 61 AH of the Islamic calendar (October 10, 680 AD)a in Karbala, in present-day Iraq.[6] The battle took place between a small group of supporters and relatives of Muhammad's grandson, Husayn ibn Ali, and a larger military detachment from the forces of Yazid I, the Umayyad caliph.

When Muawiyah I died in 680, Husayn did not give allegiance to his son, Yazid I, who had been appointed as Umayyad caliph by Muawiyah; Husayn considered Yazid's succession a breach of the Hasan–Muawiya treaty. The people of Kufa sent letters to Husayn, asking his help and pledging allegiance to him, but they later did not support him. As Husayn traveled towards Kufa, at a nearby place known as Karbala, his caravan was intercepted by Yazid I's army led by Al-Hurr ibn Yazid al Tamimi. He was killed and beheaded in the Battle of Karbala by Shimr Ibn Thil-Jawshan, along with most of his family and companions, including Husayn's six month old son, Ali al-Asghar, with the women and children taken as prisoners.[6][7] The battle was followed by later uprisings namely, Ibn al-Zubayr, Tawwabin, and Mukhtar uprising which occurred years later.

The dead are widely regarded as martyrs by Sufi, Sunni[8][9] and Shia Muslims. The battle has a central place in Shia history, tradition and theology and it has frequently been recounted in Shia Islamic literature. Mainstream Sunni Muslims, on the other hand, do not regard the incident as one that influences the traditional Islamic theology and traditions, but merely as a historical tragedy.

The Battle of Karbala is commemorated during an annual 10-day period held every Muharram by Shia and Alevi, culminating on its tenth day, known as the Day of Ashura. Shia Muslims commemorate these events by mourning, holding public processions, organizing majlis, striking the chest and in some cases self-flagellation.[10]

The Battle of Karbala played a central role in shaping the identity of the Shia and turned them into a sect with "its own rituals and collective memory."[11] For the Shia, Husayn's suffering and death became a symbol of sacrifice "in the struggle for right against wrong, and for justice and truth against wrongdoing and falsehood."[11] Hence, the battle becomes more than a politically formative moment of the Shia faith within Islam. It also defines the theological origin of the Shia martyr ethos, and it provides members of the faith with a catalogue of heroic norms whose impact is still felt today. Therefore, the commemoration of the Battle of Karbala must be seen as a paradigm (i. e. the "Karbala paradigm"), since the view of history conveyed by it claims to provide a self-contained cosmology applicable to all aspects of life.[12]

Political background

During Ali's Caliphate, the Muslim world became divided and rebellion broke out against the ruling Ali by Muawiyah I. When Ali was assassinated by Ibn Muljam (a Kharijite) in 661, his eldest son, Hasan, succeeded him but soon signed a peace treaty with Muawiyah to avoid further bloodshed.[6] In the treaty, Hasan was to hand over power to Muawiya on the condition that he be just to the people and keep them safe and secure and that he would not establish a dynasty.[13][14][15] This brought to an end the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs[16] and Hasan ibn Ali was also the last Imam for the Shias to be a Caliph.[17][failed verification] Husayn ibn Ali became the head of Banu Hashim[18] after his older brother, Hasan ibn Ali, was poisoned to death in 670 (50 AH). His father's supporters in Kufah gave their allegiance to him. However, he told them he was still bound by the peace treaty between Hasan and Muawiyah I as long as Muawiyah was alive.[6]

Yazid's succession to Mu'awiyah

The Battle of Karbala occurred within the crisis environment resulting from the succession of Yazid I.[19][20] Mu'awiyah persuaded several leading companions to swear loyalty to his son, Yazid,[21] and appointed him as his successor both in breach of the peace treaty[6][22][23] and the Shura succession principle,[6] for many Muslims instead wanted Husayn ibn Ali to be their Caliph.[24]

Later, Husayn ibn Ali did not accept Muawiyah's request for his son Yazid's succession,[25] referring to the peace treaty.[26][self-published source] The legitimacy of Yazid's succession as well as his "worthiness" for this position[21] was questioned at the time,[24][27][28] and people like Said ibn Uthman,[27] Ahnaf ibn Qais,[28] denounced the Yazid caliphate.[29] Also, Husayn ibn Ali along with the sons of several other well known companions of Muhammad namely, Abd Allah ibn Umar, and Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr[6] rejected the caliphate of Yazid,[21] because he considered the Umayyads an oppressive and religiously-misguided regime. He insisted on his legitimacy based on his own special position as a direct descendant of Muhammad and his legitimate legatees. As a consequence,[30] he left Medina, his home town, to take refuge in Mecca in 60 AH.[6] Mu'awiyah warned Yazid specifically about Husayn ibn Ali, since he was the only blood relative of Muhammad.[24][29] Abd Allah ibn Abbas and Abdullah ibn Umar did not want to start another civil war and wanted to wait. Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr challenged them and went to Mecca.[31][unreliable source]

According to Fitzpatrick et al. the Yazid succession, which was considered as an "anomaly in Islamic history", transformed the government from a "consultative" form to a monarchy,[32] named the Umayyad dynasty, with its capital in Damascus.[33][34]

Prelude

Yazid instructed his Governor Walid in Medina to force Husayn ibn Ali as well as the other prominent figures to pledge allegiance to Yazid. Husayn refused it and said that "Anyone akin to me will never accept anyone akin to Yazid as a ruler." Husayn departed Medina on Rajab 28, 60 AH (680 AD), two days after Walid's attempt to force him to submit to Yazid I's rule. He stayed in Mecca from the beginnings of the month of Sha'aban and all of the months of Ramadan, Shawwal, as well as Dhu al-Qi'dah.

It is mainly during his stay in Mecca that he received many letters from Kufa assuring him their support and asking him to come over there and guide them.[35][36] He answered their calls and sent Muslim ibn Aqeel, his cousin, to Kufa as his representative in an attempt to consider the exact situation and public opinion.

Husayn's representative to Kufa, Muslim ibn Aqeel was welcomed by the people of Kufa, and most of them swore allegiance to him. After this initial observation, Muslim ibn Aqeel wrote to Husayn ibn Ali that the situation in Kufa was favorable. However, after the arrival of the new Governor of Kufa, Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, the situation changed. Muslim ibn Aqeel and his host, Hani ibn Urwa, were executed on Dhu al-Hijjah 9, 60 AH (September 10, 680 AD) without any real resistance of the people. This shifted the loyalties of the people of Kufa, in favor of Yazid and against Husayn ibn Ali.[37] Husayn ibn Ali also discovered that Yazid had appointed `Amr ibn Sa`ad ibn al Aas as the head of an army, ordering him to take charge of the pilgrimage caravans and to kill al Husayn ibn Ali wherever he could find him during Hajj,[38][39] and hence decided to leave Mecca on 8th Dhu al-Hijjah 60 AH (9 September 680 AD), just a day before Hajj and was contented with Umrah, due to his concern about potential violation of the sanctity of the Kaaba.[40][41]

He delivered a sermon at the Kaaba highlighting his reasons to leave, that he didn't want the sanctity of the Kaaba to be violated, since his opponents had crossed any norm of decency and were willing to violate all tenets of Islam.

When Husayn ibn Ali was making up his mind to leave for Kufa, Abd Allah ibn Abbas and Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr held a meeting with him and advised him not to move to Iraq, or, if he was determined to move, not to take women and children with him in this dangerous journey. Husayn ibn Ali, however, had resolved to go ahead with his plan. He gave a speech to people the day before his departure and said:

... Death is a certainty for mankind, just like the trace of necklace on the neck of young girls. And I am enamored of my ancestors like eagerness of Jacob to Joseph ... Everyone, who is going to devote his blood for our sake and is prepared to meet Allah, must depart with us...[42]

On their way to Kufa, the small caravan received the news of the execution of Muslim ibn Aqeel and the indifference of the people of Kufa.[43][44][45] Instead of turning back, Husayn decided to continue the journey and sent Qays ibn Musahir Al Saidawi as messenger to talk to the nobles of Kufa. The messenger was captured in the vicinity of Kufa but managed to tear the letter to pieces to hide names of its recipients. Just like Muslim ibn Aqeel, Qays ibn Musahir Al Saidawi was executed.

Battle

Husayn and his followers were two days away from Kufa when they were intercepted by the vanguard of Yazid's army; about 1,000 men led by Hurr ibn Riahy. Husayn asked the army, "With us or against us?" They replied: "Of course against you, oh Aba Abd Allah!" Husayn ibn Ali said: "If you are different from what I received from your letters and from your messengers then I will return to where I came from." Their leader, Hurr, refused Husayn's request to let him return to Medina. The caravan of Muhammad's family arrived at Karbala on Muharram 2, 61 AH (October 2, 680 AD).[46] They were forced to pitch a camp on the dry, bare land and Hurr stationed his army nearby.

Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad appointed Umar ibn Sa'ad to command the battle against Husayn ibn Ali. At first Umar ibn Sa'ad rejected the leadership of the army but accepted after Ibn Ziyad threatened to take away the governorship of Rey city and put Shimr ibn Thil-Jawshan in his place.[47] Ibn Ziyad also urged Umar ibn Sa'ad to initiate the battle on the sixth day of Muharram.[48] Umar ibn Sa'ad moved towards the battlefield with an army and arrived at Karbala on Muharram 3, 61 AH (October 3, 680 AD).

Order of battle and water denial

Ibn Ziyad sent a brief letter to Umar ibn Sa'ad that commanded, "Prevent Husain and his followers from accessing water and do not allow them to drink a drop [of water]". Ibn Sa'ad followed the orders, and 5,000 horsemen blockaded the Euphrates. One of Husayn's followers met Umar ibn Sa'ad and tried to negotiate some sort of access to water, but was denied. The water blockade continued up to the end of the battle on Muharram 10th (October 10, 680 AD).[49]

Umar ibn Sa'ad received an order from Ibn Ziyad to start the battle immediately and not to postpone it further. The army started advancing toward Husayn's camp on the afternoon of Muharram 9th. At this point Husayn sent Al-Abbas ibn Ali to ask Ibn Sa'ad to wait until the next morning, so that he and his men could spend the night praying. Ibn Sa'ad agreed to the respite.[47][50][51]

On the night before the battle, Husayn gathered his men and told them that they were all free to leave the camp in the middle of the night, under cover of darkness, rather than face certain death if they stayed with him. None of Husayn's men defected and they all remained with him. Husayn and his followers held a vigil and prayed all night.[52]

The day of the battle

On Muharram 10th, also called Ashura, Husayn ibn Ali completed the morning prayers with his companions. He appointed Zuhayr ibn Qayn to command the right flank of his army, Habib ibn Muzahir to command the left flank and his half-brother Al-Abbas ibn Ali as the standard bearer. Husayn ibn Ali's companions numbered 32 horsemen and 40 infantrymen.[53] Husayn rode on his horse Zuljanah.

Husayn ibn Ali called the people around him to join him for the sake of God and to defend Muhammad's family. His speech affected Hurr, the commander of the Tamim and Hamdan tribes, who had stopped Husayn from his journey. He abandoned Umar ibn Sa'ad and joined Husayn's small band of followers.[54]

On the other side, Yazid had sent Shimr ibn Thil-Jawshan (his chief commander) to replace Umar ibn Sa'ad as the commander.[54][55][56]

The battle begins

Umar ibn Sa'ad advanced and shot an arrow at Husayn ibn Ali's army, saying: "Give evidence before the governor that I was the first thrower." Ibn Sa'ad's army started showering Husayn's army with arrows.[57][58] Hardly any men from Husayn ibn Ali's army escaped from being shot by an arrow.[58][59] Both sides began fighting. Successive assaults resulted in the death of a group of Husayn ibn Ali's companions.[58][60]

The first skirmish was between the right flank of Husayn's army and the left of the Syrian army. A couple of dozen men under the command of Zuhayr ibn Qayn repulsed the initial infantry attack and destroyed the left flank of the Syrian army which in disarray collided with the middle of the army. The Syrian army retreated and broke the pre-war verbal agreement of not using arrows and lances. This agreement was made in view of the small number of Husayn ibn Ali's companions. Umar ibn Sa'ad on advice of 'Amr ibn al Hajjaj ordered his army not to come out for any duel and to attack Husayn ibn Ali's army together.[61][62]

`Amr ibn al-Hajjaj attacked Husayn ibn Ali's right wing, but the men were able to maintain their ground, kneeling down as they planted their lances. They were thus able to frighten the enemy's horses. When the horsemen came back to charge at them again, Husayn's men met them with their arrows, killing some of them and wounding others.[62][63] `Amr ibn al-Hajjaj kept saying the following to his men, "Fight those who abandoned their creed and who deserted the jam`a!" Hearing him say so, Husayn ibn Ali said to him, "Woe unto you, O `Amr! Are you really instigating people to fight me?! Are we really the ones who abandoned their creed while you yourself uphold it?! As soon as our souls part from our bodies, you will find out who is most worthy of entering the fire![62][64]

In order to prevent random and indiscriminate showering of arrows on Husayn ibn Ali's camp which had women and children in it, Husayn's followers went out to single combats. Men like Burayr ibn Khudhayr,[65] Muslim ibn Awsaja[61][66] and Habib ibn Muzahir[67][68] were slain in the fighting. They were attempting to save Husayn's life by shielding him. Every casualty had a considerable effect on their military strength since they were vastly outnumbered by Yazid I's army. Husayn's companions were coming, one by one, to say goodbye to him, even in the midst of battle. Almost all of Husayn's companions were killed by the onslaught of arrows or lances.

After almost all of Husayn's companions were killed, his relatives asked his permission to fight. The men of Banu Hashim, the clan of Muhammad and Ali, went out one by one. Ali al-Akbar ibn Husayn, the middle son of Husayn ibn Ali, was the first one of the Hashemite who received permission from his father.[67][69][70]

Casualties from Banu Hashim were sons of Ali ibn Abi Talib, sons of Hasan ibn Ali, a son of Husayn ibn Ali, a son of Abdullah ibn Ja'far ibn Abi-Talib and Zaynab bint Ali, sons of Aqeel ibn Abi Talib, as well as a son of Muslim ibn Aqeel. There were seventy-two Hashemites dead in all (including Husayn ibn Ali).[71]

Death of Al-Abbas ibn Ali

There are two accounts regarding the death of Abbas ibn Ali; One is by Abu Mikhnaf which mentions no detail on the death and, however, the other well known report clearly details how he was killed somewhere near the river and far from the camp while fetching water with a large skin of water,[72] since the besieged Ahl al-Bayt were thirsty.[73] Al-Abbas ibn Ali advanced towards a branch of the Euphrates along a dyke. Al-Abbas ibn Ali continued his advance into the heart of ibn Sa'ad's army.[74] He was under a shower of arrows but was able to penetrate them and get to the branch, leaving heavy casualties from the enemy. He immediately started filling the water skin. In a gesture of loyalty to his brother and Muhammad's grandson he did not drink any water despite being extremely thirsty. He put the water skin on his right shoulder and started riding back toward their tents. Umar ibn Sa'ad ordered an assault on Al-Abbas ibn Ali saying that if Al-Abbas ibn Ali succeeded in taking water back to his camp, they would not be able to defeat them till the end of time. An enemy army blocked Al-Abbas' way and surrounded him. He was ambushed from behind a bush and his right arm was cut off. Al-Abbas ibn Ali put the water skin on his left shoulder and continued on his way but his left arm was also cut off. Al-Abbas ibn Ali now held the water skin with his teeth. The army of ibn Sa'ad started shooting arrows at him, one arrow hit the water skin and water poured out of it, now he turned his horse back towards the army and charged towards them but one arrow hit his eyes and someone hit his head with a gurz and he fell off the horse. In his last moments when Al-Abbas ibn Ali was wiping the blood in his eyes to enable him to see Husayn's face, Al-Abbas ibn Ali said not to take his body back to the camps because he had promised to bring back water but could not and so could not face Bibi Sakinah, the daughter of Husayn ibn Ali. Then he called Husayn "brother" for the first time in his life.[citation needed] Before the death of Abbas, Husayn ibn Ali said: "Abbas your death is like the breaking of my back". Zayd ibn Varqa Hanafi and Hakim ibn al-Tofayl Sanani are reported to be Abbas ibn Ali's murderers.[73]

Death of Husayn ibn Ali

Husayn ibn Ali told Yazid's army to offer him single battle, and they gave him his request. He killed everybody that fought him in single battles.[75] He frequently forced his enemy into retreat, killing a great number of opponents. Husayn and earlier his son Ali al-Akbar ibn Husayn were the two warriors who penetrated and dispersed the core of ibn Sa'ad's army, a sign of extreme chaos in traditional warfare.

By the afternoon of the tenth day, Husayn was left alone surrounded by the enemy. There were hesitation among the individuals over accepting the responsibility of Husayn's death.[76] According to Lohuf, Husayn advanced very deep in the back ranks of the Syrian army shouted:

Woe betide you oh followers of Abu Sufyan ibn Harb's dynasty! If no religion has ever been accepted by you and you have not been fearing the resurrection day then be noble in your world, that's if you were Arabs as you claim.[77]

They continuously attacked each other,[78] until his numerous injuries caused him to stay a moment. At this time he was hit on his forehead with a stone. He was cleaning blood from his face while he was hit on the heart with an arrow and he said: "In the name of Allah, and by Allah, and on the religion of the messenger of Allah." Then he raised his head up and said: "Oh my God! You know that they are killing a man that there is son of daughter of a prophet on the earth except him." He then grasped and pulled the arrow out of his chest, which caused heavy bleeding.[79]

A man from Banu Badaa' tribe, reportedly Malik ibn al-Nusair, struck Husayn's head with his sword causing it to bleed.[80]

According to Sayyed Ibn Tawus, the enemies hesitated to fight Husayn, but they decided to surround him. At this time Abdullah ibn Hasan, an underage boy, escaped from the tents and ran to Husayn. When a soldier intended to slay Husayn, Abdullah ibn Hasan defended his uncle with his arm, which was cut off. Husayn hugged Abd-Allah, but the boy was already hit by an arrow.[81]

Husayn got on his horse and Yazid's army continued pursuit. According to Shia tradition, a voice came from the skies stating: "We are satisfied with your deeds and sacrifices."[citation needed] Husayn then sheathed his sword and tried to get down from the horse but was tremendously injured and so the horse let him down. He then sat against a tree.[82] Husayn's attempt to reach water of Euphrates failed and he was soon after injured on his neck by an arrow thrown by a man reportedly, Husayn ibn Numair.[80]

Husayn's murder is attributed to either Sinan ibn Anas[80] or Shimr bin Thiljoshan. According to Sayyed Ibn Tawus, Umar ibn Sa'ad ordered a man to dismount and to finish. Khowali ibn Yazid al-Asbahiy preceded the man but became afraid and did not do it. Then Shimr bin Thiljoshan dismounted from his horse to do the job. Husayn ibn Ali asked for the permission to do Asr prayers. Shimir gave the permission to say the prayers and Husayn ibn Ali started prayer and when he went into Sajda, Shimr ibn Dhiljawshan betrayed and said: "I swear by God that I am cutting your head while I know that you are grandson of the Messenger of Allah and the best of the people by father and mother." He cut off the head of Husayn ibn Ali with his sword and raised the head.[83] Then ibn Sa'ad's men looted all the valuables from Husayn's body.

Aftermath

Following the battle, Umar ibn Sa'ad's army stormed the camp of the family of Husayn, looting any valuables and setting fire to the tents. They captured the family of Husayn and sent Husayn's head and the deceased to ibn Ziyad in Kufa in the afternoon. Subsequently, Husayn's family were moved to the Levant by the forces of Yazid.[84][85]

Prisoners' Journey to Damascus

The sermon of Zaynab bint Ali in the court of Yazid

According to an account by Rasheed Turabi, on the first day of Safar,[86] they arrived in Damascus and the captured family and heads of the dead were taken to Yazid.[87] Yazid asked the identity of each dead person and then noticed a woman with a defiant demeanour and asked, "Who is this arrogant woman?" The woman approached him and retorted: "Why are you asking them [the woman]? Ask me. I will tell you [who I am]. I am Muhammad’s granddaughter. I am Fatima’s daughter." People at the court were awestruck by her oratory skills. Zaynab bint Ali then proceeded to give a sermon which according to Turabi is among the three most memorable sermons by the family of the Prophet[87] According to the narration of Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid, a man with red skin asked Yazid one of the captured woman as bondwoman.[88] Yazid is also said to have knapped at Husayn's teeth with the staff of his hand while saying: "I wish those of my clan who were killed at Badr, and those who had seen the Khazraj clan wailing (in the battle of Uhud) on account of lancet wounds, were here.[86] At this time, Zaynab bint Ali began to give her sermon to stop Yazid.[89]

The sermon of Ali ibn Husayn in Damascus

According to Bihar al-Anwar, in Damascus Yazid ordered a pulpit to be prepared. He appointed a public speaker to bash Ali and Husayn ibn Ali. The public speaker sat on the pulpit and began his lecture by praising Allah and insulting Ali and his son, Husayn. He devoted a long time to praising Yazid and his father Muawiyah.[90] In the meantime Ali ibn Husayn seized the opportunity[91] and began to give a sermon by Yazid’s permission, introducing himself and his ancestors. He also related the story of Husayn ibn Ali's murder.[90]

Burial of dead bodies

After ibn Sa'ad's army went out of Karbala, some people from Banu Asad tribe came there and buried their dead, but did not mark any of the graves, with the exception of Husayn's which was marked with a simple plant. Later Ali ibn Husayn returned to Karbala to identify the grave sites. Hurr was buried by his tribe a distance away from the battlefield.[92] The prisoners were held in Damascus for a year. During this year, some prisoners died of grief, most notably Sukayna bint Husayn. The people of Damascus began to frequent the prison, and Zaynab and Ali ibn al-Husayn used that as an opportunity to further propagate the message of Husayn and explain to the people the reason for Husayn's uprising. As public opinion against Yazid began to foment in Syria and parts of Iraq, Yazid ordered their release and return to Medina, where they continued to tell the world of Husayn's cause.

Later uprisings

Battle of Karbala and Husayn's death was a stimulus for further movements in Kufah with many people expressing their regret for their "apathy".[93]

Ibn al-Zubayr's revolt

Following the Battle of Karbala, Husayn ibn Ali's second cousin Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr confronted Yazid. The people of Mecca also joined Abdullah to take on Yazid. Eventually Abdullah consolidated his power by sending a governor to Kufa. Soon Abdullah established his power in Iraq, southern Arabia, the greater part of Syria and parts of Egypt. Yazid tried to end Abdullah’s rebellion by invading the Hejaz, and he took Medina after the bloody Battle of al-Harrah followed by the siege of Mecca. But his sudden death ended the campaign. After the Umayyad civil war ended, Abdullah lost Egypt and whatever he had of Syria to Marwan I. This, coupled with the Kharijite rebellions in Iraq, reduced his domain to only the Hejaz.[94]

Following the sudden death of Yazid and his son Mu'awiya II took over and then abdicated and died in 683 Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr was finally defeated by Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, who sent Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf. The defeat of Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr re-established Umayyad control over the Empire.[94]

Tawwabin uprising

After the killing of Husayn ibn Ali in Karbala, Shia were regretful and blamed themselves for not doing anything to help their Imam. Due these emotions a first uprising was begun by a group of Shia of Kufa that came to be known as Tawwabin.[95] The uprising started under the leadership of five followers of Ali ibn Abi Talib, father of Husayn ibn Ali, with a following of one hundred of Kufa's people. They held the first meeting in the house of Sulayman ibn Surad Khuzai, one of the Sahabahs of Islamic prophet Muhammad, in 61 AH. In this meeting, Sulayman was elected as the uprising's leader. They also decided to keep their uprising a secret. This conspiracy remained hidden until 65 AH.[96][97] One of the reasons given to explain the absence of Sulayman at the battle of Karbala was that he had been imprisoned by Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad at the time of the battle.[98]

In Rabi' al-thani of 65 AH, Sulayman summoned to Nukhayla the men who had joined his army. It is said that of the 16,000 Shia who had promised to show up, only 4,000 arrived. One of the reasons was that Mukhtar al-Thaqafi believed that Sulayman had no experience in war, so many Shia, especially Shia from Mada'in and Basra, from Khuzai's army began to desert in large numbers. Finally, 1,000 others left the army. The remainder spent three days in Nukhayla then went to Karbala to pilgrimage to the tomb of Husayn.[99] The Tawwabin army fought an Ummayad army in the battle of 'Ayn al-Warda. Their leaders were killed in this battle and they were defeated.[100]

While Tawwabin uprising was based on "feelings and was hasty," and led to failure from a military viewpoint, it had significant impact on the larger Muslim community. The uprising had also real effect on other Shia movements, such as the Mukhtar uprising, which finally led to the decline of the Ummayad. Those Shia movements lacked military "tactics and techniques" as they believed that their "sacred" goal sufficed.[101]

Mukhtar uprising

Mukhtar al-Thaqafi led a revolt centered on Kufah, one considered to be on behalf of Mohammad ibn al-Hanafiyya, a son of Ali. The uprising which lasted from 685 to 687, was against Ibn Zubayr in the first instance.[102] The goal of the uprising was to avenge Husayn's blood in Karbala and to defend the Ahl al-Bayt.[103]

Mukhtar was imprisoned by Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, when the Tawwabin uprising was defeated in battle of 'Ayn al-Warda. Mukhtar contacted the remaining members of Tawwabin from prison and promised to help them very soon. They replied that they could break into prison and release Mukhtar, but Mukhtar rejected the offer. He was released later via his sister's husband, Abdullah ibn Umar's mediation. After Mukhtar was released, he gathered Shia leaders such as Ibrahim ibn Malik al-Ashtar, who was an influential figure and thus very effective in recruiting men.[103] Mukhtar was considerably supported by Mawali, non-Arab Muslims,[104] mostly from Kufah, Basra and Al-Mada'in.[105]

In the night before 14th Rabi' al-awwal of 65 AH,[106] Mukhtar's followers began the revolt by shouting Ya Mansur-o Amet (O victorious, make [them] die!), a slogan originally used by Muslims in battle of Badr, and Ya Lisarat al-Husayn (O Those Who Want to Avenge the Blood of Husayn). Forces allied with Mukhtar entered Kufah. Iranian forces called Jond-o-l Hamra'a (Red Army) were the core of Mukhtar's forces. Finally, Mukhtar captured Ibn Ziyad's palace and announced the victory of his uprising on the following day, when he led prayers in a mosque, as well as holding a lecture regarding the goals of his uprising.[103]

Mukhtar's uprising had large scale participation by a client class. His reliance on clients and Persians, as they were "more obedient" and "more faithful and swift in performance" according to Mukhtar, and raising the social status of Mawalis to that of Arabs, made the Ashraf of Kufah revolt against Mukhtar. According to Mohsen Zakeri, Kufa were not ready for such "revolutionary measures" and this may be counted as one of the reasons behind Mukhtar's failure.[105] Finally, Mukhtar was attacked by Mus'ab ibn al-Zubayr, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr's brother, he urged on by some leaders in Kufa.[106][107] Mus'ab besieged Mukhtar in his palace for four months. Mukhtar was finally killed on 14th Ramadan, after he had left the palace.[106]

Impacts on culture and politics

Battle of Karbala played a central role in shaping the identity of Shia and turned the already distinguished sect into a sect with "its own rituals and collective memory." Husayn's suffering and death became a sacrifice symbol "in the struggle for right against wrong, and for justice and truth against wrongdoing and falsehood."[11] Battle of Karbala is described as a "supreme" example of "suffering and martyrdom" pattern for Shia.[102]

The battle was a determining event in the schism between Sunni and Shia Muslims.[108]

As the "height of oppression" and "the peak of Umayyad brutality against the Prophetic family",[109] "Karbala paradigm"[12] had its own political impacts since pre-Safavid times and oppressors were often called "Yazids of the age."[110] Revenge for battle of Karbala became "the core of the Shia collective memory and sentiment" since then and it had a determining role on "shaping religious perceptions." From political viewpoint, "Karbala-oriented epic literature" acted as an ideological stimulus to the Safavid revolution and Mourning of Muharram kept its political functions under the Islamic Republic of Iran.[109]

The first political uses of Karbala symbols date back to the year of the battle. Buyid rulers promoted the public rituals of Muharram, the earliest documented account of Muharram procession, along with a celebration of Ghadir Khumm "to promote their religious legitimacy and to strength of Shia identity in and around Baghdad." Similarly, Safavid rulers fairly used the rituals to promote their legitimacy, with their Sunni rivals in east (the Uzbeks) and west (the Ottomans).[111] Moḥarram festival then became a unifying force for the nation.[112]

The Islamic revolution of Iran was inspired by Ashura uprising with its first sparks lit during Muharram. June 5, 1963 demonstrations in Iran, a turning point in history of Iranian revolution, happened two days after Khomeini’s speech on the afternoon of Ashura. Ashura uprising was not merely a historical issue at the time and was "the axis of mobilization" against Pahlavi regime.[113] In Bahrain, calling for Muharram processions and commemorating Husayn ibn Ali's memory in public led to 1979 Qatif Uprising, when the procession was "brutally" repressed by the Saudi government.[114][115]

Historiography of the battle of Karbala

Primary sources

The first historian to systematically collect the reports of eyewitnesses of this event was Abu Mikhnaf (died in 157 AH/774 AD) in a work titled Kitab Maqtal Al-Husayn.[116] Abi Mikhnaf's original seems to have been lost and that which has reached today has been transmitted through his student Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi (died in 204 AH) There are four manuscripts of the Maqtal, located at Gotha (No. 1836), Berlin (Sprenger, Nos. 159–160), Leiden (No. 792), and Saint Petersburg (Am No. 78) libraries.[117]

According to Rasoul Jafarian, among the original works on maqātil (a generic name for narratives of Hosayn bin ‘Ali’s tragic death in Karbala) the ones that could be relied upon for reviewing the Karbala happenings are five in number. All these five maqtals belong to the period between the 2nd century AH (8th century AD) and the early 4th century AH (10th century AD). These five sources are the Maqtal al-Husayn of Abu Mikhnaf; the Maqtal al-Husayn of Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi, Sunni historian; the Maqtal al-Husayn of Al-Baladhuri, Sunni Historian; the Maqtal al-Husayn of Abū Ḥanīfa Dīnawarī, and the Maqtal al-Husayn of Ahmad ibn A'tham.[118] However, some other historians have recognized some of these as secondary sources. For example, Laura Veccia Vaglieri has found that Al-Baladhuri (died 279 AH/892-893 AD) like Tabari has used Abu Mikhnaf but has not mentioned his name.[119] On the basis of the article of "Abi Mikhnaf" in "Great Islamic Encyclopedia" Ahmad ibn A'tham has mentioned Abu Mikhnaf in "Al-Futuh" thus he should be recognized as a secondary source.[120]

Even though Abu Mikhnaf's Maqtal Al-Husayn is a primary source to Shias, much of the content in his narration does not meet up with Shia standards of narration criticism.[121][better source needed]

Secondary sources

Then latter Muslim historians have written their histories on the basis of the former ones especially Maqtal Al-Husayn of Abu Mikhnaf. However they have added some narrations through their own sources which were not reported by former historians.

Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari narrated this story on the basis of Abu Mikhnaf's report through Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi in his history, History of the Prophets and Kings.[122] Also there is a fabricated version of Abu Mekhnaf's book in Iran and Iraq.[116] Then other Sunni Muslim historians including Al-Baladhuri and Ibn Kathir narrated the events of Karbala from Abu Mikhnaf. Also among Shia Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid used it in Irshad.[123] However, followers of Ali attached a much greater importance to the battle and have compiled many accounts known as Maqtal Al-Husayn.

Shia writings

Salwa Al-Amd has classified Shia writings in three groups:[124]

- The legendary character of this category associates the chronological history of Husayn ibn Ali with notions relating to the origin of life and the Universe, that have preoccupied the human mind since the beginning of creation, and in which Al-Husayn is eternally present. This category of writing holds that a person's stance toward Husayn ibn Ali and Ahl al- Bayt is a criterion for reward and punishment in the afterlife. It also transforms the historical boundaries of Husayn ibn Ali's birth in 4 AH and his death in 61 AH to an eternal presence embracing the boundaries of history and legend.

- This category comprises the literary works common in rituals and lamentations (poetic and prose) and is characterized by its melodramatic style, which aims to arouse pity and passion for Ahl al- Bayt's misfortunes, and charge feelings during tempestuous political circumstances on the memory of Ashura.

- This category is the nearest to Sunni writings because it fully cherishes the historical personality of Husayn ibn Ali and regards the Karbala incident as a revolt against oppression; dismissing the legendary treatment, while using the language of revolt against tyranny and despotic sovereignty. A model writer of this category is Mohamed Mahdi Shams Al-Din.

Historical questions

As Jafarian says "The holding of mourning ceremonies for Husayn ibn Ali was very much in vogue in the eastern parts of Iran before the Safavids came to power. Kashefi wrote the "Rawzah al-Shuhada" for the predominantly Sunni regions of Herat and Khurasan at a time when the Safavid state was being established in western Iran and had no sway in the east."[125]

After the conversion of Sunni Iran to the Shia faith, many Iranian authors composed poems and plays commemorating the battle.[126] Most of these compositions are only loosely based upon the known history of the event.[127]

Some 20th-century Shia scholars have protested the conversion of history into mythology. Prominent critics include:

- Morteza Motahhari[128][129][130]

- Abbas Qomi, author of Nafas al-Mahmoum[131]

- Sayyid Abd-al-Razzaq Al-Muqarram, author of Maqtalul-Husayn[132]

Also several books have been written in the Persian language about political backgrounds and aspects of the battle of Karbala.[133][134]

Impact on literature

Bengali Literature

In 1885-1891, Mir Mosharraf Hossain wrote a novel named Bishad Shindhu (the Ocean of Sorrow) regarding Karbala.[135][136]

Persian literature

Va'ez Kashefi's Rowzat al-Shohada (Garden of Martyrs) authored in 1502, is one of the main sources used for quoting the history of the battle and aftermath in later histories. Kashfi's composition was "a synthesis of a long line of historical accounts of Karbala," such as Said al-Din's Rowzat al-Islam (The Garden of Islam) and al-Khawarazmi's Maqtal nur 'al-'a'emmeh (The Site of The Murder of the light of The Imams). Kashefi's composition was an effective factor in formation of rowzweh khani, a kind of ritual.[111] The name of Husayn ibn Ali appears several times in the work of the first great Sufi Persian [citation needed] poet, Sanai. According to Annemarie Schimmel, the name of the martyred hero can be found now and then in connection with bravery and selflessness, and Sanai sees him as the prototype of the shahid (martyr), higher and more important than all the other martyrs who are and have been in the world.[137]

The tendency to see Husayn ibn Ali as the model of martyrdom and bravery continues in the poetry written in the Divan of Attar.[citation needed] When Shiism became the official religion of Iran in the 15th century, Safavid rulers such as Shah Tahmasp I, patronized poets who wrote about the Battle of Karbala, and the genre of marsia, according to Persian scholar Wheeler Thackston, "was particularly cultivated by the Safavids."[138]

Azeri and Turkish literature

Muhammed's grandsons played a special role in Sufi songs composed by Yunus Emre in the late 13th or early 14th century.[139]

Sindhi literature

Sindhi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai of Bhitshah (1689–1752) devoted "Sur Kedaro" in his Shah Jo Risalo to the death of the grandson of Muhammed, and saw the battlet of Karbala as embedded in the mystical tradition of Islam. A number of poets in Sindh have also composed elegies on Karbala, including Sayed Sabit Ali Shah (1740–1810).[140]

Urdu literature

In the Adil Shahi and Qutb Shahi kingdom of Deccan, marsia flourished, especially under the patronage of Ali Adil Shah and Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, marsia writers themselves, and poets such as Ashraf Biyabani.[citation needed] Urdu marsia written during this period are still popular in South Indian villages.[141] Ghalib described Husayn ibn Ali, by using metaphors, similar to the ones he used in his odes.[citation needed] Mir Taqi Mir and Mirza Rafi Sauda wrote marsia in which the Battle of Karbala was saturated with cultural and ceremonial imagery of North India.[141]

Josh Malihabadi known as "Shair-i inqilab", or the poet of revolution, used the medium of marsia to propagate the view that Karbala is not a pathos-laden event of a bygone era, but a prototype for contemporary revolutionary struggles.[citation needed]

Vahid Akhtar, formerly Professor and Chairman, Dept. of Philosophy at Aligarh Muslim University,[142] has been crucial in keeping the tradition of marsia dynamic in present-day South Asia.[citation needed] Akht disagrees with the interpretation of the deaths at Karbala as mere Islamic history; but sees them as part of the revival of an ideal Islamic state of being.[143]

Albanian literature

The events of the battle and the following rebellion of Mukhtar al-Thaqafi of 66 AH have been the subject of major works in the Albanian Bektashi literature of the 19th century. Dalip Frashëri's Kopshti i te mirevet (Garden of the martyrs) is the earliest and longest epic so far written in Albanian language. It seems that Frashëri's initial idea was to translate and adapt Fuzûlî's work with the same name, it ended up as a truly national and comprehensible composition on its own. The poem is made of around 60,000 verses, is divided in ten sections, and is preceded by an introduction which tells the story of the Bektashism in Albania. The poem cites the sect's important personalities, latter additions, and propagation. It follows with the history of the Arabs before Islam, the work of the Prophet, his life and death, and events that led to the Karbala tragedy. The Battle of Karbala is described in detail; Frashëri eulogizes those who fell as martyrs, in particular Husayn ibn Ali.

His younger brother Shahin was the author of Mukhtarnameh (Book of Mukhtar), Albanian: Myhtarnameja, an epic poem of around 12,000 verses. It is also one of the longest and earliest epics of the Albanian literature.

Both works established a subgenre in the Albanian literature of the time, and served as the model for the better known work Qerbelaja (Karbala) of Naim Frashëri, the Albanian national poet and a Bektashi Sufi follower as well.[144][145]

Shia observances

Commemoration of Husayn's death commenced soon after year 61 AH with small gatherings. By the time of Muhammad al-Baqir and Jafar al-Sadiq, two of Husayn's descendants and Shia Imams, Karbala had become an important Shia pilgrimage site.[76] Shia ritual during Muhraam, i.e. mourning of Muharram, was not documented until the tenth century and the earliest account concerning this public ritual is the one concerning the events took place in 963 during the reign of "Moe'z al-Dowleh, the Buyid ruler of southern Iran and Iraq." Shi'a rituals developed mostly during Safavid state in 1501, and took a new meaning in that era.[111]

According to Yitzhak Nakash, rituals of Muharram has an "importance" effect on the "invoking the memory of Karbala", as it induces moods and motivations in the believers via the symbol of Husayn's "martyrdom surface" and fuses the world as lived and the world as imagined.[11]

Shia Muslims commemorate the Battle of Karbala every year in the Islamic month of Muharram. The mourning of Muharram begins on the first day of the Islamic calendar and then reaches its climax on Muharram 10, the day of the battle, known as Ashurah. It is a day of Majlis, public processions, and great grief. In the Indian sub-continent Muharram in the context of remembrance of the events of Karbala means the period of two months & eight days i.e., 68 days starting from the evening of 29 Zill-Hijjah and ending on the evening of 8 Rabi-al-Awwal.[146] Men and women chant and weep, mourning Husayn ibn Ali, his family, and his followers. Speeches emphasize the importance of the values the sacrifices Husayn ibn Ali made for Islam. Shia mourners in countries with a significant majority self-flagellate with chains or whips, which in extreme cases may causing bleeding.[147] This mainly takes place in countries such as Iraq, Iran, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Most Shias show grievances, however, through weeping and beating their chests with their hands in a process called Lattum/Matam while one recites a Latmyah/Nauha.[148] Forty days after Ashurah, Shias mourn the death of Husayn ibn Ali in a commemoration called Arba'een.[149]

In South Asia, the Battle of Karbala has inspired a number of literary and non-musical genres, such as the marsia, noha, and soaz. In Indonesia, the Battle of Karbala is remembered in the Tabuik ceremony.

See also

- Imam Husayn Shrine

- List of casualties in Husayn's army at the Battle of Karbala

- Al-Mukhtar

- Persecution of Shia Muslims

- Sahabah

- Mokhtarnameh

- The Hussaini Encyclopedia

- Al-Hannanah mosque

Notes

- ^a When converting the date for the day of Ashura into the Christian calendar, it is possible to produce an error of plus or minus two days. Such discrepancies may arise because a source may be using a date in the tabular Islamic calendar, which is not necessarily the date if the month begins with the first visibility of the crescent. One source may be using the Julian calendar, another the Gregorian calendar. The day of the week may be miscalculated. The dates in this article are all Julian. According to the book Maqtal al-Husayn, Muharram 9th was a Thursday (i.e., October 11, 680); if that source is correct Muharram 10th was Friday October 12, 680 AD.

Footnotes

- ^ "Battle of Karbala' (Islamic history)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b "Karbala, the Chain of Events". Al-Islam.org.

- ^ Datoo, Mahmood. "At Karbala". Karbala: The Complete Picture. p. 167.

- ^ "Karbala: The Complete Picture (chapter 8.3)". mahmooddatoo.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tabari, The History of al-Tabari, volume 19, translated by IKA Howard, pub State University of New York Press, p. 163.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Madelung, Wilferd. "Hosayn b. ali". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Gordon, 2005, pp. 144–146

- ^ Administrator. "Martyrdom of Imam al-Hussain (R.A)". Ahlus Sunnah.

- ^ fazeela (15 November 2013). "The Excellences of the Imam Husayn in Sunni Hadith Tradition – Islam Guidance". Sibtayn.com. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Calmard, Jean. "ḤOSAYN B. ʿALI ii. IN POPULAR SHIʿISM". Iranica. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Nakash, Yitzhak (1 January 1993). "An Attempt To Trace the Origin of the Rituals of Āshurā¸". Die Welt des Islams. 33 (2). Princeton: 161–181. doi:10.1163/157006093X00063. Retrieved 16 July 2016. – via Brill (subscription required)

- ^ a b Gölz, "Kerbalaparadigma", In: Compendium heroicum. Ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher and Anna Schreurs-Morét, published by Collaborative Research Centre 948 „Helden – Heroisierungen – Heroismen“, University of Freiburg, Freiburg 26.04.2018. doi:10.6094/heroicum/kerbalaparadigma, (also)"

- ^ Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. BURLEIGH PRESS. pp. 66–78.

- ^ Jafri, Syed Husain Mohammad (2002). The Origins and Early Development of Shi’a Islam; Chapter 6. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195793871.

- ^ Madelung, Wilferd. "The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate". University of Oxford Press. p. 61.

- ^ Syed, Muzaffar Husain; Akhtar, Syed Saud; Usmani, B. D. (14 September 2011). Concise History of Islam. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789382573470. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Azmayesh, Dr Seyed Mostafa (7 January 2016). New Researches on the Quran: Why and How Two Versions of Islam Entered the History of Mankind. Mehraby. ISBN 9780955811760. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ Lammens, H. (2012). "al-Ḥasan". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. doi:10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_SIM_2728.

- ^ G.R., Hawting (2012). "Yazīd (I) b. Muʿāwiya". Encyclopaedia of Islam (second ed.). Brill.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K. (1961). The Near East In History A 5000 Year Story. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 1258452456. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Clinton (1 January 1998). In Search of Muhammad. A&C Black. ISBN 9780304704019. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Martin, Richard C. (2004). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). New York: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 293. ISBN 0-02-865912-0.

- ^ Madelung, Wilferd. "ḤASAN B. ʿALI B. ABI ṬĀLEB". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Weston, Mark (28 July 2008). Prophets and Princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470182574. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Ibn Katheer. Ismail Ibn Omar (ed.). Al-Bidayah wan-Nihayah [The Caliphate of Banu Umayyah the first Phase]. Translated by Yoosuf Al-Hajj Ahmad. p. 82. ISBN 978-603-500-080-2.

In the year 56 AH Muawiyah called on the people including those within the outlying territories to pledge allegiance to his son, Yazid, to be his immediate heir to the Caliphate. Almost all subjects offered their allegiance, with the exception of Abdur Rahman bin Abu Bakr (the son of Abu Bakr), Abdullah ibn Umar (the son of Umar), al-Husain bin Ali (the son of Ali), Abdullah bin Az-Zubair (The grandson of Abu Bakr) and Abdullah ibn Abbas (Ali's cousin).

- ^ Marafi, Najebah. The Intertwined Conflict: The Difference Between Culture and Religion. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781477128367. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ a b ibn Habib, Mohammad. "(the Sixth Letter deals with assassinated personalities)". Nawadir al Makhtutat. p. 165.

- ^ a b "Volume. 1 (1328 A.H./1910 A.D.: Al-Umma Press, Egypt)". Al Imamah wal Siyasah. p. 141.

- ^ a b Maqtal al Husain – Al Husain's Uprising. pp. 21–33.

- ^ Dakake, Maria Massi (2007). The charismatic community : shi'ite identity in early islam. Albany (N. Y.): SUNY Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7914-7033-6. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Karbala: Chain of events Section – Yazid Becomes Ruler". Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Coeli; Walker, Adam Hani (25 April 2014). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610691789. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079195. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Elhadj, Elie (2006). The Islamic Shield: Arab Resistance to Democratic and Religious Reforms. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 9781599424118. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J. (December 2006). Voices of Islam. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275987329. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Howard, I. K. A. (1990). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 19: The Caliphate of Yazid b. Mu'awiyah A.D. 680-683/A.H. 60–64. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791400401. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ The Tragedy of Karbala, pg. 23

- ^ al Gulpaygani, Shaykh Lutfullah. Muntakhab al Athar fi Akhbar al Imam al Thani ‘Ashar, Radiyaddin al Qazwini. pp. 304, 10th Night.

- ^ Maqtal al Husain – The Journey to Iraq. p. 130.

- ^ Nama, ibn. Muthir al Ahzan. p. 89.

- ^ Al-Tabari. Tarikh. Vol. 06. p. 177.

- ^ Lohouf, by Sayyid ibn Tawoos, Tradition No.72

- ^ Al-Tabari. Tarikh. Vol. 6. p. 995.

- ^ Maqtal al Husain – Zarud. p. 141.

- ^ Kathir, Ibn. Al Bidaya. Vol. 08. p. 168.

- ^ "Karbala: Chain of events Section – On the Way to Karbala". Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Karbala: Chain of events Section – Karbala". Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ al Qazwini, Radiyaddin ibn Nabi. Tazallum al Zahra. p. 101.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – The Watering place". p. 162.

- ^ Tabari, Al. Tarikh. Vol. 06. p. 337.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – Day Nine". p. 169.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – Those Whose Conscience is Free". p. 170.

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No. 140

- ^ a b "Maqtal al Husain – Al-Hurr Repents". p. 189.

- ^ Tabari, Al. Tarikh. Vol. 06. p. 244.

- ^ Book "Martyrdom Of Hussain"

- ^ Maqrizi, Al. Khutat. Vol. 02. p. 287.

- ^ a b c "Maqtal al Husain – The First Campaign". p. 190.

- ^ al Bahraini, Abdullah Nurallah. Maqtal al Awalim. p. 84.

- ^ Majlisi, Al. Bihar al Anwar.

Mohammad ibn Abutalib

- ^ a b Tabari, Al. Tarikh. Vol. 06. p. 249.

- ^ a b c "Maqtal al Husain – The Right Wing Remains Firm". p. 193.

- ^ al Kathir, Ibn. Al-Kamil. Vol. 04. p. 27.

- ^ al Kathir, Ibn. Al-Bidaya. Vol. 08. p. 182.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – Burayr ibn Khudayr". p. 201.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – Muslim ibn Awsajah". p. 193.

- ^ a b Tabari, Al. Tarikh. Vol. 06. p. 251.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – Habib ibn Mazahir". p. 196.

- ^ al-Tabari, ibn-Tavoos, et al.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – Ali al Akbar". p. 206.

- ^ "Maqtal al Husain – Martyrdom of Ahl al Bayt". pp. 206–235.

- ^ Bulookbashi, Ali A.; Negahban, Tr. Farzin (2008). "Al- ʿAbbās b. ʿAlī". Encyclopedia Islamica. Brill.

- ^ a b Calmard, J. (13 July 2011). "ʿABBĀS B. ʿALĪ B. ABŪ ṬĀLEB". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition 174 and 175.

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No.177

- ^ a b Najam I., Haider (2016). "al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill.

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No.179

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No.181

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No.182

- ^ a b c Katheer, Ibn. The Short Story of Al-Husain bin 'Ali, (May Allah be Pleased with him). Darussalam Publishers. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No.184, 185

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No.188

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No. 192 and 193

- ^ Qumi Abbas. Muntahal Aamaal fi tarikh al-Nabi wal Aal. Vol. 1. p. 429.

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No. 222, 223

- ^ a b Qumi, Abbas. Nafasul Mahmum, Relating to the heart rending tragedy of Karbala'. Translated by Aejaz Ali T Bhujwala. Islamic Study Circle.

- ^ a b Syed Akbar Hyder Assistant Professor of Asian Studies and Islamic Studies University of Texas at Austin N.U.S. (23 March 2006). Reliving Karbala: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-19-970662-4.

- ^ Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid. al-Irshad. p. 479.

- ^ "Martyrdom of Imam al-Hussain (Radhi Allah Anhu)". ahlus-sunna.com. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ a b Qumi Abbas (2005). Nafasul Mahmoom. Ansariyan Publications. ASIN B003FZF19W.

- ^ Dungersi Ph.D., M. M. (1 December 2013). A Brief Biography of Ali Bin Hussein (as). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 1494328690.

- ^ Lohouf, Tradition No. 226

- ^ Lalani, Arzina R. (2000). Early Shi'i Thought: The Teachings of Imam Muhammad Al-Baqir. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860644344. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ a b Seyyed, Muzaffar Husain; Akhtar, Syed Saud; Usmani, B. D. (14 September 2011). Concise History of Islam. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789382573470.

- ^ Moshe Sharon (1983). Black Banners from the East: The Establishment of the ʻAbbāsid State: Incubation of a Revolt. JSAI. p. 103. ISBN 9789652235015.

- ^ Sayyid Husayn Muhammad Ja'fari. The Origins and Early Development of Shia Islam. Ansariyan Publications.

- ^ Baqir Shareef al-Qurashi. The Life of Imam Zayn al-‘Abidin. Ansariyan Publications.

- ^ Muhammad Reza Muzaffar. The history of Shia. p. 17.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy. The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. p. 27.

- ^ Dr. I.K.A Howard. The Tawwabin: The Repenters.

- ^ Lamei Giv, Ahmad; Falsafi, Leyla (5 May 2016). "Tawwabin Uprising: The Emergence, Development and Influence on the Arab World". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 7 (3 S1). Italy. doi:10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n3s1p439.

- ^ a b Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415240727. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ a b c "The Philosophy of Mukhatr Uprising". Research Institute of Hadrat Vali Asr. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Mawali". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Oxford. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ a b Zakeri, Mohsen (1 January 1995). Sasanid Soldiers in Early Muslim Society: The Origins of 'Ayyārān and Futuwwa. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447036528. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Al-Sayyid, Kamal. Mukhtar al-Thaqafy. Qum: Ansariyan Publications.

- ^ "The outcome of Mukhtar uprising". Official Website of Ayatollah Makrem Shirazi. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ Jana, Riess (15 November 2004). "The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi'i Symbols and Rituals in Modern Iran". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 16 July 2016. – via General OneFile (subscription required)

- ^ a b Yildirim, Riza (26 November 2015). "In the Name of Hosayn's Blood: The Memory of Karbala as Ideological Stimulus to the Safavid Revolution". Journal of Persianate Studies. 8 (2): 127–154. doi:10.1163/18747167-12341289. Retrieved 16 July 2016. – via Brill (subscription required)

- ^ Calmard, Jean. "ḤOSAYN B. ʿALI ii. IN POPULAR SHIʿISM". Iranica.

- ^ a b c Aghaie, Kamran Scot (1 December 2011). The Martyrs Of Karbala: Shi'i symbols and rituals in modern Iran. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800783. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter (2004). "ḤOSAYN B. ʿALI iii. THE PASSION OF ḤOSAYN". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ Baqian, Morteza. "Ashura's place in genesis of Islamic Revolution of Iran". Islamic Revolution Document Center. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jones, Toby Craig (1 January 2006). "Rebellion on the Saudi Periphery: Modernity, Marginalization, and the Shiʿa Uprising of 1979". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 38 (2): 213–233. JSTOR 3879971.

- ^ Louër, Laurence (2012). "Shi'I Identity Politics In Saudi Arabia". Religious minorities in the Middle East domination, self-empowerment, accommodation. Leiden: Brill. pp. 221–243. ISBN 9789004216846. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b Wa bi-l-laahi-t-tawfiq. "Kitab Maqtal al-Husayn by Abu Mikhnaf" (PDF). www.sicm.org.uk. Shia Ithna'ashari Community of Middlesex. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Jafari, Sayyed Hossein Mohammad (2001). The origins and early development of Shi'a Islam (2. impression ed.). Karachi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579387-1. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ "A Glance Into The Sources On The Incident Of Āshūrā". ahl-ul-bayt.org.[permanent dead link]

- ^ In the Istanbul Ms. of the Ansab, Husayn ibn Ali is discussed in Ms. 597, ff. 219a-251b

- ^ "Abu Mikhnaf". Center for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia (in Persian). Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Karbala – The Facts and the Fairy-tales". twelvershia.net.

- ^ Abu Mihnaf: ein Beitrag zur Historiographie der umaiyadischen Zeit by Ursula Sezgin

- ^ Syed Husayn M. Jafra (4 April 2002). The Origins and Early Development of Shi'a Islam. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579387-1.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "On Difference & Understanding: Al-Husayn: the Shiite Martyr, the Sunni Hero". islamonline.net. Archived from the original on 2006-12-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Shaykh Radi Aal-Yasin; Translated by Jasim al-Rasheed. Sulh al-Hasan (The Peace Treaty of al-Hasan (a)). Qum: Ansariyan Publications. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Table of Contents and Excerpt, Aghaie, The Women of Karbala". utexas.edu.

- ^ Jafarian, Rasool. "13". A Glance at Historiography in Shiite Culture.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "'Ashura – Misrepresentations and Distortions part 1". Al-Islam.org.

- ^ "First Sermon: 'Ashura – History and Popular Legend". Al-Islam.org.

- ^ "'Ashura – Misrepresentations and Distortions". imamalinet.net. Archived from the original on 2005-11-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nafasul Mahmum, Relating to the heart rending tragedy of Karbala'". Al-Islam.org.

- ^ "Research Ḥusayn Ibn ʿAlī, Al- – Encyclopedia of Religion". www.BookRags.com.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-12-10. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "دبیرخانه مجلس خبرگان رهبری : صفحه اصلی". Majlesekhobregan.ir. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ Dalmia, Vasudha; Sadana, Rashmi (2012), The Cambridge Companion to Modern Indian Culture, Cambridge University Press, p. 108, ISBN 1139825461

- ^ Osmany, Shireen Hasan (1992), Bangladeshi nationalism: history of dialectics and dimensions, University Press, p. 61, ISBN 9840511882

- ^ "Karbala and the Imam Husayn in Persian and Indo-Muslim literature". Al-Islam.org.

- ^ Wheeler Thackston, A Millennium of Classical Persian Poetry (Bethesda: Iranbooks, 1994), p.79.

- ^ Yunus Emre Divani, p. 569.

- ^ Staff writers (22 October 2015). "Incident of Karbala in the poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai – The Sindh Times". The Sindh Times. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 December 2006. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Aligarh Muslim University". amu.ac.in.

- ^ "Karbala an Enduring Paradigm of Islamic Revivalism". Al-Islam.org.

- ^ H.T.Norris (1993), Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World, Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, pp. 180–181, ISBN 9780872499775, OCLC 28067651

- ^ Robert Elsie; Centre for Albanian Studies (London) (2005), Albanian Literature: A Short History, I.B. Tauris, p. 42, ISBN 9781845110314, OCLC 62131578

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Muharram: Mehndi processions to be taken out tomorrow". The Times of India. 2 December 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Sulekha.com – For all your Local Needs & Property Details". Sulekha.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Latmiyat definition – What does Latmiyat mean?".

- ^ Shiites throng Karbala for Arbaeen despite threats

References

- Al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (1990). History of the Prophets and Kings. translation and commentary issued iby I. K. A. Howard. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-395-65237-5. (volume XIX.)

Bibliography

- al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir, History of the Prophets and Kings; Volume XIX The Caliphate of Yazid b. Muawiyah, translated by I.K.A Howard, SUNY Press, 1991, ISBN 0-7914-0040-9.

- Kennedy, Hugh, The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State, Routledge, 2001.

- al-Muqarram, Abd al Razzaq, Maqtal al-Husayn, Martyrdom Epic of Imam al-Husayn, translated by Yasin T. Al-Jibouri, pub Al-Kharsan Foundation for Publications, originally published Qum, circa 1990. (al-Muqarram was born in 1899 and died in 1971—author's biography. This is a 20th-century book—see Islamic Historiography, by Chase F. Robinson, p. 35.)

External links

Sunni links

Shia links

- Events of Karbala

- Ashura.com

- Poetryofislam.com, poetry on Kerbala by Mahmood Abu Shahbaaz Londoni

- Sacred-texts.com, Battle of Karbala Template:En icon

- Battle of Karbala

- A Probe Into the History of Ashura by Dr. Ibrahim Ayati