Bengal famine of 1943

| Bengal famine of 1943 | |

|---|---|

| File:Statesman j.jpg Image from the photo spread in The Statesman on 22 August, 1943 showing famine conditions in Calcutta. These photos altered world opinion on colonialism. | |

| Country | British India |

| Location | Bengal |

| Period | 1943–44 |

| Total deaths | Current est. 2.1 million |

| Consequences | Income inequality increased; Indian independence movement intensified |

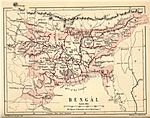

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

The Bengal famine of 1943-44 (Bengali: Pañcāśēra manwantara) was a major famine in the Bengal province[A][B] in British India during World War II. An estimated 2.1 million[C] people died in the famine, the deaths occurring first from starvation and then from diseases, which included cholera, malaria, smallpox, dysentery, and kala-azar. Other factors, such as malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions, and lack of health care, further increased disease fatalities. Millions were impoverished as the crisis overwhelmed large segments of the economy and social fabric, accelerating a trend toward economic inequality.

Bengal's economy was predominantly agrarian. For at least a decade before the crisis, between half and three quarters of those dependent on agriculture were already at near subsistence level. Underlying causes of the famine included inefficient agricultural practices, dense population, and de-peasantisation through debt bondage and land grabbing. Proximate causes comprise localised natural disasters (a cyclone, storm surges and flooding, and rice crop disease) and at least five consequences of war: initial, general war-time inflation of both demand-pull and monetary origin; loss of rice imports due to the Japanese occupation of Burma (modern Myanmar); near-total disruption of Bengal's market supplies and transport systems by the preemptive, defensive scorched earth tactics of the Raj (the "denial policies" for rice and boats); and later, massive inflation brought on by repeated policy failures, war profiteering, speculation, and perhaps hoarding. Finally, the government prioritised military and defense needs over those of the rural poor, allocating medical care and food immensely in the favour of the military, labourers in military industries, and civil servants. All of these factors were further compounded by restricted access to grain: domestic sources were constrained by emergency inter-provincial trade barriers, while access to international sources was largely denied by the War Cabinet of Great Britain. The relative impact of each of these contributing factors to the death toll and economic devastation is still a matter of controversy. Different analyses frame the famine against natural, economic, or political causes.

The government was slow to supply humanitarian aid, at first using propaganda to discourage hoarding. It attempted to drive rice paddy prices down through price controls and a series of procurement schemes. Price controls merely created a thriving black market and encouraged cautious sellers to withhold their stocks; moreover, prices soared when the controls were abandoned. Relief efforts in the form of gruel kitchens, agricultural loans and test works were both insufficient and ineffective through the worst months of the food crisis phase. Despite having a long-established and detailed Famine Code that would have triggered a sizable increase in aid, the provincial government never formally declared a state of famine. Relief efforts increased significantly when the military took control of crisis relief in October 1943, and more effective aid arrived after a record rice harvest that December. Deaths from starvation began to decline, but "very substantially more than half" of the famine-related fatalities were caused by disease in 1944, after the food security crisis had subsided.[1]

Background

From the late nineteenth century through the Great Depression, social and economic forces exerted a harmful impact on the structure of Bengal's income distribution and the ability of its agricultural sector to sustain the populace. These processes included a rapidly growing population, increasing household debt, stagnant agricultural productivity, increased social stratification, and alienation of the peasant class from their landholdings. The interaction of these left clearly defined social and economic groups mired in poverty and indebtedness, unable to cope with economic shocks or maintain their access to food beyond the near term. In 1942 and 1943, in the immediate and central context of the Second World War, the shocks Bengalis faced were numerous, complex and sometimes sudden.[2] Millions were vulnerable to starvation.[3]

Rice

The Government of India's Famine Commission Report (1945) described Bengal as "a land of rice growers and rice eaters".[4] Rice dominated the agricultural output of the province, accounting for nearly 88% of its arable land use[5] and 75% of all crops sown.[D] Overall, Bengal produced one third of India's rice.[5] Rice accounted for between 75 and 85% of daily food consumption.[6] Fish was the second major food source, [7] supplemented by small amounts of wheat.[E] The consumption of other foods was typically relatively small.[6]

There are three seasonal rice crops in Bengal. By far the most important is the winter aman crop, sown in May and June, and harvested in November and December. It comprises more than 70% of the rice grown in a given year. The second most important crop is the aus or autumn crop, sown around April and harvested in August and September, which accounts for more than 20% of the yearly harvest. Finally, there is a small amount of boro or spring crop, planted in November and harvested in February and March.[8] Crucially, the (debated) shortfall in rice production in 1942 occurred during the all-important aman seasonal harvest.[9]

Population and agricultural productivity

One reason for the high excess mortality of 1943–45 was a clash between soaring population levels and a shortage of land in Bengal, and a longstanding history of stagnant agricultural productivity in India. Bengal was very densely populated.[F] Moreover, according to census figures, its population had been increasing at an accelerating rate: in ten-year periods, the rate of growth started at 2.8% from 1911 to 1921, then increased to 7.3% from 1921 to 1931, and soared to 20.3% from 1931 to 1941. Bengal's population rose by 43% (from 42.1 million to 60.3 million) between 1901 and 1941, while India's population as a whole increased by 37% over the same period.[10][G]

Aside from a great concentration of war factories in industrialised areas in Greater Calcutta,[4][H] and some mining in the extensive Raniganj Coalfield of the western districts, Bengal's economy was almost solely agrarian. In an agricultural society, arable land is the most important resource, and subsistence and cash crops are the most important commodities. However, agricultural productivity in Bengal was amongst the lowest in the world.[11] Agricultural production had traditionally been characterised by "dependence on monsoon rainfall [instead of controlled and reliable irrigation],[I] archaic methods and crude tillage, low intensity of inputs, subsistence farming, proneness to famines, and the low productivity of land".[12] Rice yield per acre had been stable[13] or falling for perhaps centuries,[14] and certainly since at least the beginning of the twentieth century.[15][J]

Prior to about 1920, the food demands of Bengal's growing population could be met in part by bringing undeveloped lands under the plough.[16] Probably around the turn of the twentieth century, and certainly no later than the early 1930s, Bengal began to experience an acute shortage of land[17][K] and a chronic and growing shortage of rice.[18] Bengal's agricultural inability to keep pace with rapid population growth changed it from a net exporter to a net importer of foodgrains.[19] Although imports constituted a small part of the total production,[20] this may have been accompanied by a decrease in average consumption levels;[21] it was estimated in 1930 that the Bengali diet was the least nutritious in the world:[22]

Bengal's rice output in normal years was barely enough for bare-bones subsistence. An output of 9 million tons translates into one pound per day or less than 2,000 kcal per adult male. Even allowing for imports from neighboring provinces and Burma and trade accounted for only a small fraction of supplies in 1942/3 the province's margin over subsistence on the eve of the famine was slender.[23]

Taken together, these conditions left a large proportion of the population continually on the brink of malnutrition or even starvation.[24] In the end, the rising population and falling productivity created a long-term decline in food availability that left a large proportion of Bengal's citizens – between one and two thirds – living at or near subsistence level at all times. "So delicate was the balance between actual starvation and bare subsistence," asserted the Famine Inquiry Commission of 1945, "that the slightest tilting of the scale in the value and supply of food was enough to put it out of the reach of many and to bring large classes within the range of famine."[25]

Rural credit and land-grabbing

The system of land tenureship in India as a whole and Bengal in particular was very complex, and the credit transactions between landholders and tenants were equally complicated.[26][L] Very broadly speaking, land rights and the resulting power and welfare gains within Bengal were divided very unequally among three diverse economic and social groups; moreover, this division of power evolved over time and expressed itself differently within the different geographic regions of the province. The three economic groups were: traditional absentee large landowners or zamindars,[M] the upper-tier "wealthy peasant" jotedars; and at the lower socioeconomic levels, the ryot (peasant) smallholders and dwarfholders, bargadars (sharecroppers), and agricultural labourers.[27] Zamindar and jotedar landowners were protected by legal and customary status and rights.[28] At the bottom were the ones actually cultivating the soil, with small or no landholdings. These had very nearly no rights, and the few they had were vague, contradictory and commonly ignored.[29] Typically this problem was compounded by a lack of written records.[30] They laboured within a power structure decisively stacked against them[31] and suffered persistent and increasing losses of land rights and welfare over time.[32]

Over the decades at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the early twentieth, the power and influence of the zamindars fell and that of the jotedars rose. The shift was caused by a rent crisis that was sparked by nineteenth century tenancy legislation,[27] and accelerated after the Great Depression.[33] Jotedars began to make substantial profits and gain power in their villages through their two defining roles: grain or jute traders, and more importantly, creditors who extended loans to sharecroppers, agricultural labourers and ryots.[34] The jotedars' power in the commodity and credit markets translated directly into power over their tenants.[27] They began to leverage their economic and social clout to "[obtain] the land and occupancy rights of the [ryot] through both legal and coercive means".[35] In a few districts in the southwest, such as Midnapore and 24 Parganas, they were able to employ political means.[36] However, their principal instruments of self-enrichment were a combination of debt bondage through the transfer of debts and mortgages, and parcel-by-parcel land-grabbing.[37]

Land-grabbing was typically accomplished through the manipulation of the informal credit market. Many formal credit market entities had disappeared during the Great Depression, and peasants who held smaller lots of land generally had no capital to utilise a formal credit market to purchase any good or service beyond their immediate means.[38] They typically had to resort to informal local lenders;[39] for example, when they needed consumer credit for large, occasional expenses such as weddings, religious ceremonies, births, or deaths.[40][N] More frequently, they needed money to help purchase basic necessities during lean months between harvests,[41][O] and so were "forced to sell their products at deflated prices during post-harvest glut, in order to pay loans taken during the pre-harvest 'starvation' season".[42] Moreover, though land had traditionally been relatively available, the means of production (such as seed or cattle for ploughing) had always been scarce,[43] and smallholders' lands were sometimes sold in times of distress to purchase these.[44] At other times, peasants were simply compelled by force to take on debt.[41]

Small landholders and sharecroppers were still required to pay rent and taxes and pay off their debts, which were characterised by usurious rates of interest.[45][P] Any poor harvest thus exacted a heavy toll, given their lack of legally defined security. The accumulation of consumer debt, seasonal loans, and crisis loans began a cycle of spiraling, perpetual indebtedness. This dynamic was reinforced by laws, originally designed to alleviate usury, that restricted access to credit and discouraged or prevented the practice of using farmlands as collateral for loans.[Q] This had the unintended effect of making creditors less willing to accept farmlands as a pledge against a debt, and more likely to simply wait until their debtors were unable to repay their loans.[46] Then it was relatively easy for the jotedars to use litigation to force debtors to sell all or part of their landholdings at a low price or forfeit them at auction. Debtors then became landless or land-poor sharecroppers and labourers, usually working the same fields they had once owned.[47] The credit-driven slide into poverty converted farmers from smallholders into dwarfholders, and from dwarfholders into sharecroppers or agricultural labourers. The accumulation of household debt to a single, local, informal creditor (who also held power over land and sometimes grain or jute) also bound the debtor nearly inescapably to the creditor/landlord; it became nearly impossible to settle the debt after a good harvest and simply walk away.[48] In this way, the jotedars effectively dominated and impoverished the lowest tier of economic classes in several districts of Bengal.[49]

Land alienation

The end result of this process of exploitation, along with Muslim inheritance practices that divided up land among multiple siblings,[50] was the substantial, progressive growth in the number of landless bargadars and paid labourers in Bengal.[51] This in turn created both high degrees of social stratification and growing inequalities in land ownership.[52][R] At the time of the famine, millions of Bengali agriculturalists held little or no land. "The number of actual tillers of the soil with occupancy rights is diminishing so rapidly," the Land Revenue Commission of 1940 reported with alarm, "that the disappearance of this class is imminent".[53] The Government of Bengal described this trend in 1940:

The Census figures show an increase [in the population that are jotedars] of 62 per cent, between 1921 and 1931, and since 1931 there has been a further process of subinfeudation below the statutory [ryot], which will swell the figures still more. At the same time a steady reduction is taking place in the number of actual cultivators possessing occupancy rights, and there is a large increase in the number of landless labourers. Their number increased by 49 per cent, between 1921 and 1931. They now constitute 29 per cent of the total agricultural population, and the next Census will show a considerably larger increase.[54]

Two contemporary reports – the 1940 Report of the Land Revenue Commission of Bengal[55] and the field survey published in Mahalanobis, Mukherjea & Ghosh (1946) – included measures of the amount of land held per Bengali family. These reports agree that even before the famine of 1943, at least half of the nearly 46 million in Bengal who depended on agriculture for their livelihood were landless or land-poor labourers under consistent threat of food insecurity, with landholdings barely adequate to provide for the dietary needs of the owner's family.[56]

Given "an average production of 820 lbs. of rice per acre, an average consumption of about 320 lbs. per head per year and an average family size of 5.4 persons", approximately 2 acres of farmland would provide subsistence-level food for an average family,[57] and between 5 and 8 acres of farmland were needed to keep them in "reasonable comfort".[58] According to the 1940 Land Revenue Board report, 46% of rural families owned two acres or less or were landless tenants. The 1946 field survey[S] found that 77.5% did not own sufficient land to provide subsistence for themselves. Passmore (1951) describes the small- or dwarfholding ryot's economic state in the run-up to the famine: "... after a century free from war and famine, the value of his savings, his credit, and his household goods combined could not provide the purchase for three weeks' supply of rice for his family, [at the greatly inflated prices during the famine]."[59] Millions of landless or land-poor agriculturalists in Bengal suffered from "serious undernourishment at all times",[60] living "... on the narrow margin which separates subsistence from starvation".[61] For these Bengalis, according to anthropologist T. C. Das, "[whenever] there was even a slight disturbance of the balance, either through natural or artificial causes, a large number of them fell victims of starvation".[61]

Transport

Boats were the only reliable means of transport in many areas throughout Bengal, given its "more than 90,000 villages and 20,000 miles of water communications winding through thick jungle".[62] This was true across most of the province during the rainy seasons or all the time in portions of eastern Bengal and the vast delta of the coastal southeastern Sundarbans, where the rivers of the Ganges Delta merge into the Bay of Bengal. River transport was integral to many facets of Bengal's economic system: nearly irreplaceable for both the production and distribution of rice[63] and jute and the livelihoods of fishermen and transport workers. It was also indispensable for the transport of the supplies and finished goods of various artisan trades, such as potters, weavers, and basket makers.[64]

The alternatives to water transport were roads and the rail system. Roads, however, were scarce and generally in poor condition.[65] Bengal's extensive railway system was always dependent upon relatively small boats to deliver production supplies to peripheral riverine areas and transport crops to distribution centers, and was employed even less in the commercial sphere after the demands of war clogged trains and roads with military cargo. Some of the stations did connect with important grain centers; however, boats were required to transport commercial produce, traders and trade from remote areas. Moreover, after 1941, many "nonproductive" branches of the railways were dismantled, with engines and rolling stock shipped overseas,[66] and lines in eastern Bengal were later shut down or dismantled on the same premise as the "denial of boats" policy.[67] Those railway lines that were left intact were almost solely utilised for military and industrial transport until the very late stages of the crisis.[68]

The development of railways in Bengal between roughly 1890 and 1910 contributed to the excess mortality of the famine. The construction of a network of railway embankments disrupted natural drainage and divided Bengal into innumerable poorly drained "compartments".[69] This brought about excessive silting, increased the tendency toward flooding, created stagnant water areas, damaged crop production, contributed (in some areas) to a partial shift away from the productive aman rice cultivar to less productive aush or boro cultivars, and provided a more hospitable environment for water-borne diseases such as cholera and malaria. Such diseases clustered around the tracks of railways.[70][T]

Soil and water supply

The Bengal soil profile impacted the famine in two ways. First, the soil in eastern Bengal, in combination with abundant irrigation from monsoon rains, was unique for its ability to grow large amounts of high quality jute. This gave Bengal an effective monopoly on a cash crop.[71] Jute of lesser quality was grown in smaller quantities in western Bengal, but eastern Bengal was the clear-cut center of jute production. During the famine, jute-producing districts suffered higher mortality rates.[72] Second, the sandy soil of eastern Bengal and the lighter sedimentary soil of the Sunderbans tended to drain more rapidly after the monsoon season than the laterite or heavy clay regions of western Bengal. As a rule, malaria epidemics lasted approximately one month longer in the areas with slower drainage.[73] This problem was compounded by the fact that soil exhaustion created the need for large tracts in western and central Bengal to be left fallow; eastern Bengal had far fewer fallow fields. Flooded fallow fields are one key breeding place for malaria carrying mosquitoes,[74] which was the biggest killer during the famine.[75]

Rural areas lacked access to safe water supplies in the event of an epidemic of waterborne diseases. Water came primarily from large earthen tanks, rivers and tube wells. In the dry season, partially drained tanks became yet another hospitable breeding area for malaria vector mosquitoes.[76] Tank and river water, moreover, are readily susceptible to contamination by cholera; tube wells are much safer in this respect.[77][U] However, landlords were often reluctant to sink tube wells for economic reasons, even when credit was extended for this purpose,[78] and as many as one-third of the existing wells in war-time Bengal were in disrepair due to government inefficiency and the high cost of materials.[77] The national government urged an initiative to repair these wells in November 1943, but actual work was not begun until after the cholera epidemic had subsided.[79]

Pre-famine shocks and distress

Throughout 1942 and into early 1943, a complex series of overlapping crises placed enormous, widespread stress on Bengal's economy, particularly on its more vulnerable segments. Distressing military and political events and subsequent government and market responses created escalating price shocks that overlapped with supply shocks caused by natural disasters and plant disease later in the year.[80] As Bengal's food needs rose from increased military presence and an influx of refugees from Burma,[81] its ability to obtain rice and other foodgrains from outside the province was restricted by interprovincial trade barriers. The outlook of the typical Bengali, particularly in the countryside, deteriorated into a general belief in the inevitability of famine and devastating inflation, a lack of faith in the government's ability to overcome the crises, and a mood of isolation and panic. In nearly every sector of the population, the overriding concerns were the lack of food and personal safety,[82] though a small number secured record profits amidst the havoc.[83]

February–April 1942: Japanese invasion of Burma

The Japanese campaign to conquer Burma, which began in late December 1941, set off an exodus for India among more than half of the one million Indians then living in Burma.[84] After the bombing of Rangoon in late December 1941, many better-off Indians left by sea for ports in Bengal. In January 1942, before the Fall of Rangoon, another 70,000 Indians left by sea for Madras and Calcutta.[85] However, most Indians, between 450,000 and 500,000, trekked overland to India.[84] Of these, between 100,000 and 200,000 cut through the Arakan hills in western Burma, and up along the coast or coastal waters, to Chittagong in Eastern Bengal;[86] this route was closed in March 1946. Of the remaining Indians, who had now moved north in the face of the advancing Japanese, some 220,000 trekked up the lower Chindwin river valley and eventually arrived in the Indian princely state of Manipur.[87] A third group, and the last to leave Burma, moved up the upper Irrawaddy river valley and arrived in the Indian province of Assam.[84] In early March 1942, the Government of India began constructing a road along the Manipur route, offering supplies and limited transport.[88] However, barely had the road been completed, when, on April 26, 1942, a full retreat from Burma into India was ordered for all Allied forces.[88] Immediately, all priorities changed, and the demands of the military became the focus of official attention.[88] According to author Hugh Tinker, “The Indians were left to their own devices. ... the troops arrived: pushing the refugees aside, laying hands on all supplies, and utilizing all available military transport.”[89] By mid May 1942, the monsoon rains became heavy in the Manipur hills, further inhibiting civilian movement.[90] The depleted refugees fell victim to disease, initially to dysentery, smallpox and malaria, and later to cholera.[91] It was noted that of the few refugees who arrived at the main Manipur refugee camp near Imphal, in the later stages of the evacuation, 70–80% were thought to be ill, and 30% gravely so.[91] From April 1942, with refugees from Burma entering India in large numbers, the medical establishment in eastern India took to monitoring occurrence of serious contagious diseases, considered both an internal security and public health risk.[92] Later the same concerns would inform decisions on the location of famine relief camps, as refugees from the famine of 1943, many feared to be carrying similar diseases, made their way toward urban centres in Bengal.[92]

During their long arduous return journeys, the Indians had received mixed treatment from the local Burmese; some Indians were treated with kindness, in keeping with the prevailing Buddhist culture of Burma; however, others were subjected to extortion, robbery, and violence.[93] Between 10,000 and 50,000 Indians refugees, according to one estimate, died from various causes before they reached India.[94] By May 1942, some 300,000 refugees had passed through Bengal en route to their homes elsewhere in India.[95] Back home, the refugees told tales of atrocities inflicted by the Burmese and of the viciousness of the Japanese attack. Rumor and panic took hold in many parts of India. In Assam, through which the injured British and Indian soldiers had returned in May, fears arose of a Japanese attack. In the United Provinces, where in Gorakhpur district alone, some 30,000 refugees had returned by the end of 1942, the Governor publicly lamented the low morale.[95] In Bengal, a witness before the Government-appointed Famine Commission, recalled later in 1945, that the refugees were "bringing hair-raising stories of atrocities and sufferings. The natural effect of all that on the people of Bengal was to make them feel that the times were extremely uncertain and that terrible things might happen."[96] The civil administration in Bengal was also affected: the embittered and humiliated colonial administrators from Singapore and Burma who had appeared in Calcutta in early 1942 further unnerved the already demoralized and shorthanded colonial Indian civil service.[97] In many parts of India, the Japanese victory had created the public perception that the British Raj was vulnerable, its end near, perceptions that were to later draw increased participation in the Quit India movement of August 1942.[98]

In April 1942, Japanese carrier-based aircraft attacked the ports of Colombo and Trincomalee in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), in what came to be called the Easter Sunday Raid, and destroyed the heavy cruisers Dorsetshire and Cornwall, the aircraft carrier Hermes, and some lighter naval craft in the Indian Ocean waters off that isand.[99] Around the same time, Japanese light warships and aircraft sank approximately 100,000 tons of merchant shipping in the Bay of Bengal, and Japanese aircraft dropped a handful of bombs on the port of Vizakapatam, on India's southeastern coast, causing panic there and along that coast.[100] According to the war despatches of General Wavell, Commander-in-Chief of the army in India, both the War Office in London and the commander of the British Eastern Fleet, then employed in Madagascar, acknowledged that the fleet was powerless to mount serious opposition to a Japanese naval attack on Ceylon, southern- or eastern India, or shipping in the Bay of Bengal.[100] The Japanese raids in the Bay of Bengal also worsened an ongoing transportation problem in eastern India.[101] Before 1942, the railway systems in Assam and eastern Bengal, as well as in the Ganges Delta in Bengal, both single-line metre gauge, had offered poor access to those regions, as the major waterways crisscrossing them, the Brahmaputra and the Ganges Delta channels, flowed entirely unbridged along their lengths.[101] In 1942, the Japanese raids put additional strain on the railways, which later that year also had to face the flooding in the Brahmaputra, a malaria epidemic which was the worst in years, and the Quit India movement which targeted road and rail communication.[102] According to scholar Iftekhar Iqbal, the Japanese attack had a longer term effect as well; for throughout the period of the Bengal famine, the rail transportation of relief and civil supplies was compromised not only by the railways' military obligations, but also by the dismantling of the rail tracks that had been carried out in some areas of eastern Bengal in May 1942 to head off a potential Japanese invasion.[103]

The fall of Rangoon cut off the routine import of Burmese rice into India and Ceylon.[V][104] In India, according to the Famine Commission's, Final Report, "the areas most affected were parts of the provinces of Bombay and Madras and the States of Cochin and Travancore."[105] The imports from Burma normally met India's supply deficit in rice, which totaled 1,750,000 tons.[106] In Bengal, the net import for which actual receipts and despatch documents existed,[W] was on average 50,000 tons annually for 1932–1937,[108] and 159,000 tons annually for 1938–42,[108] the highest levels being recorded for the years 1934 and 1939 at 364,000 tons and 382,000 tons respectively.[109] But, according to the Final Report, there was also unrecorded import into Bengal "by country boat from Assam and from Arakan in Burma" the extent of which was not known accurately.[110] The Commission proposed that this import was of the order of 50,000 tons annually for 1932–1937 and 100,000 tons annually for 1938–1942.[X] Aggregate consumption was also computed, not by a direct approach using census-based population statistics whose margin of error was too high,[111] but by indirect estimation from a combination of the available values of annual supply, net import, carry-over stock at the year's beginning, and the same at the year's end.[Y][112] However, as carry-over stock in any individual year could not be accurately estimated, averages were computed for a longer periods under the expectation that the carry-over stock at the beginning and the end of the periods were negligible compared to the total consumption during the periods.[112] The commission also made adjustments in annual supply, which had errors stemming from the assessment of cultivated acreage under the permanent settlement in Bengal.[112] In this way, average consumption for the 15-year period 1928 to 1942 was computed to be 8.14 million tons annually for unadjusted acreage,[113] and 9.18 million tons for the adjusted.[114] Annual consumption was then estimated by assuming that it veered off the unadjusted average by increments, or decrements, of 0.10 million tons every year,[115][113] and off the adjusted average by those of 0.12 million tons.[113] Using these data in the Famine Inquiry Commission report, the percentage of net imports—either recorded only, or both recorded and unrecorded, computed relative to a 15-year- or 5-year time period, and to consumption- or supply averages, which were either unadjusted or adjusted—were found by scholars to be 1.1% and 1.4% in one instance,[Z] and "less than 4%" in another.[AA] Using different data, P. C. Mahalanobis estimated the net imports to be on average 1% of aggregate supply for the period 1934–39, estimating their highest value for a single year at 5% for 1934, and noting that "the physical quantities of net imports was never large."[18] While acknowledging that the influx of Burma rice was a factor in stabilizing prices, as it prevented hoarding or cornering the market, he concluded that there was "chronic but a growing shortage of rice in Bengal," which had not affected prices or imports because a large number of people, lacking the money to buy enough food, often made do with less than what was enough.[18]

Even before 1942, with uncertainty prevailing about the war, rice cultivators were proceeding with caution, and parting with their produce less readily.[66] Large-scale government investment in a war-related economy had created inflation.[118] The larger workforce, keen to secure its supplies, was buying more.[66] The price of rice in September 1941 was already 69% higher than in August 1939.[66] With the fall of Burma, there was increased demand on the rice producing regions from those regions which more critically relied on Burmese imports.[119] This, according to the Famine Commission, was occurring in a market in which the "progress of the war made sellers who could afford to wait reluctant to sell."[119] The Japanese attack had not only provoked a scramble for rice across India,[66] but had also caused a dramatic and unprecedented price inflation in Bengal,[120] and in other rice producing regions of India.[121] In Bengal, the impact of the loss of Burma rice on price levels was vastly disproportionate to the size of the loss.[122] Despite this, the export of Bengal rice to other regions of India increased during the first half of 1942.[121] In the first seven months of 1942, these exports totaled some 319,000 tons in contrast to 136,000 tons over the same period in 1941; the imports, however, had reduced by 300,000 tons in that same time.[119] Under pressure from the UK,[123] Bengal continued to export rice to Ceylon[AB] for months afterward, even as the beginning of a food crisis began to become apparent.[AC] The influx of refugees created more demand for food.[124] More clothing and medical aid were needed, further straining the resources of the province.[citation needed] [125] All this, together with transport problems that were to be created by the government's "boat denial" policy, were the direct causes of inter-provincial trade barriers on the movement of foodgrains,[126] and contributed to a series of failed government policies that further exacerbated the food crisis.[120]

1942–45: Military build-up, inflation, and displacement

The cutoff of Burma rice was not the only reason that normal trade channels failed to supply affordable rice to Bengal; there was also the proximity of Bengal to the war front, and the new status of Bengal as the base for war-related operations in India.[121] These, according to the Famine Commission, made the "material and psychological repercussions of war more pronounced" in Bengal than elsewhere in India.[121] War-related construction, in addition, was carried out in Bengal on a larger scale, causing acute inflationary pressures.[128] Increased employment brought increased labor militancy to Calcutta and its environs between August 1942 and June 1944. According to scholar S. Das, "In Kidderpore Docks out of 60,000 workers 15,000 were on strike; in Howrah and Lilloah railway sheds an estimated 3,000 out of a workforce of 25,000 resorted to strike to press forth their economic demands."[129] There were strikes in cotton mills, iron and steel works, gun and shell factories, pharmaceutical works, engineering firms, and other support industries demanding benefits, such as war bonuses.[129]

To the Calcutta docks came soldiers of many nations. Americans arrived throughout the autumn 1943, and built a large depot on the docks, not far from the pre-existing British one.[130] Nearby were barracks for the various armed forces, the soldiers there creating social disruption of their own during their off-duty hours.[130] There was "serious local inflation," set off, according to author Iftekhar Iqbal, by the paying out of cash for "unproductive purposes," whether in the form of salaries to unskilled laborers for the construction of airfields and military works or compensation for war-related requisition of private land, homes, or boats, and beginning in southeastern Bengal in April 1942.[131][AD] Nearly a thousand homes in Calcutta had been requisitioned for military use and nearly 30,000 residents dislocated.[132] To the south of Calcutta, entire villages had been forced to evacuate for military use, dislocating another 30,000 people.[133] According to the Famine Commission, overall, those evacuated from their homes and land numbered more than 30,000 families,[134][AE] which comprised, in the calculations of author Iqbal, some 150,000 individuals.[135] The Famine Commission thought that despite compensation being paid to the families, there was "little doubt" that many of their members became famine victims in 1943.[134]

The Japanese conquest of Burma had prompted a large buildup of the British Indian army, a significant portion of which was stationed in eastern India—in Bengal and Assam—along the border with Burma.[136] The Japanese conquest also cut for the Allies the overland link to China being used to supply weapons and equipment to the troops of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and their American advisers opposing the Japanese occupation forces in China.[136] To counter this loss, 100,000 Chinese troops were brought to India, to be trained in Bihar province, adjoining Bengal to the west.[136] Also, American airmen and other forces began to arrive in India in 1942 in markedly increasing numbers to fly supply missions to China from northeast India over northern Burma hills.[136] By 1943, Calcutta had become a hub for Allied troops, who were stopping in the city on route to the war front and returning for R&R.[127] Ian Stephens, the editor of The Statesman newspaper of Calcutta, recalled in a memoir that the city was "a vortex of humanity into which men doing war-jobs from all over the world ... were being sucked,"[127] Stephens singling out by nationality the more numerous troops from Britain, distant regions of India, the U.S. and China.[127] According to authors Lohmann and Thompson, "feeding and supplying these large numbers of soldiers posed a significant challenge to the Allied command in India and put a much greater strain on already stretched domestic food supplies."[136] It also put pressure on the civil administration in Bengal charged with the distribution of food and medicine, leaving it with less than adequate available staff and infrastructure when the famine struck in 1943.[137]

There were local scarcities of daily necessities such as kerosene, cloth, sugar, cooking oil, pulses, fish, matches, yarn, coal and ice;[138] prices rose rapidly due to the general inflationary pressures of a war-time economy.[139] Economist Amartya Sen, in discussing the exchange rates relative to the price of rice, in Bolpur, Birbhum district, notes, "While some items, e.g. wheat flour, cloth and mustard oil, more or less kept pace with rice in terms of price movements," during the period January 1942 to March 1943, "fish and bamboo umbrellas fell behind, and milk and haircuts declined sharply in value."[140] The productive capacity of Indian industry, which had been relatively meagre after the stagnation arising from the Great Depression, faced significant capacity constraints that drove up prices of Indian goods and commodities. The rise in prices of essential goods and services was initially "not unsatisfactory" and "not disturbing", but became more alarming in 1941.[141] Then in early 1943, the rate of inflation for foodgrains in particular took an unprecedented upward turn.[142]

Nearly the full productive output of India's cloth, wool, leather, and silk industries was sold directly to the military.[143] In the system that the UK Government used to procure goods through the Government of India, rather than outright requisitioning the means of production, the productive capacity of Indian industries was left in private ownership. Firms were required to sell goods to the military on credit and at fixed, low prices,[144] but were left free to charge any price they desired in their domestic market for whatever they had left over. In the case of the textiles industries that supplied cloth for the uniforms of the UK military, for example, they charged "a very high price indeed" in domestic markets.[144] By the end of 1942, cloth prices had more than tripled from their pre-war levels; they had more than quadrupled by mid-1943.[145] Much of the goods left over for civilian use were purchased by speculators.[146] As a result, "civilian consumption of cotton goods fell by more than 23 per cent from the peace time level by 1943/44".[147] The effects were felt by the rural population in a "cloth famine", one of the severe hardships of the crisis in Bengal that was not alleviated until military forces began distributing relief supplies; for example, the United States Air Force flew 100 tons of warm clothing into eastern Bengal.[148]

The method of credit financing was also tailored to UK wartime needs. The UK agreed to pay for defence expenditures over and above the amount that India had paid in peacetime (adjusted for inflation). However, their purchases were made entirely on credit accumulated in the Bank of England and not redeemable until after the war. At the same time, the Bank of India was permitted to treat those credits as assets against which it could print currency up to two and a half times more than the total debt incurred. India's money printing presses then began running overtime, printing the currency that paid for all these massive defence expenditures. The tremendous rise in nominal money supply spurred monetary inflation, reaching its peak in 1944–45. The accompanying rise in incomes and purchasing power fell disproportionately into the hands of industries in Calcutta (in particular, munitions industries).[149]

March 1942: Denial policies

British authorities also feared that the Japanese would proceed through captured Burma and on into British India, attacking over the eastern border of Bengal. As a preemptive measure, a two-pronged scorched-earth initiative was launched in eastern and coastal Bengal. The objective of these "denial policies" was to prevent or impede the expected Japanese invasion by denying access to food supplies or transport (plus other resources) from eastern India.[AF] The policies' impact on the development of the famine — the extent to which they compounded or even caused the later crisis — has been the subject of much discussion.[AG]

The first policy, called "denial of rice", was carried out in three southern districts along the coast of the Bay of Bengal that were expected to have surpluses of rice – Bakarganj (or Barisal), Midnapore and Khulna. In late March 1942, Governor Herbert, acting under orders from the UK, issued a directive requiring surplus stocks of paddy (rough, unhusked rice) and other food items to be removed or destroyed in three districts.[150] Great urgency was attached to the task; the Governor instructed various agents to do it almost immediately.[151] Some rice was apparently simply destroyed,[152] but paddy was also purchased by government agents in coastal districts and stored in various locations.[153] Official figures for the amounts of rice and paddy impounded were relatively small; reductions of this level would inflict only limited damage, reducing local peasants' access to rice and contributing to local scarcities in an already perilous period.[154] Evidence that fraud, corruption and coercive practices by the purchasing agents drained far more rice from the market than officially recorded, not only in the three designated districts, but also in unauthorised areas, suggests that the impact may have been greater.[155] Far more damaging, finally, was the policy's disturbing impact on regional market relationships and contribution to a sense of confusion and public alarm.[156]

Denial of boats

A boat-denial policy was demanded by the military,[157] designed to deny Bengali vehicles to any invading Japanese army. It applied to districts readily accessible via the Bay of Bengal and the larger rivers that flow into it,[AH] as well as the important ports of Chittagong and Calcutta. The three rice-denial districts were affected, as were nine others: Hooghly, Howrah, 24 Parganas, Jessore, Faridpur, Tippera, Dacca, Noakhali, and Chittagong. Hastily announced on 2 April 1942, without consultation with the provincial Government of Bengal, the policy was implemented on 1 May after an initial registration period.[158] It authorised the Army to confiscate, relocate or destroy any boats large enough to carry more than ten persons; it also allowed them to requisition other means of transport such as bicycles, bullock carts, and elephants. Some tools and instruments were also seized.[159]

The Army had confiscated approximately 46,000 rural boats.[160] The policy severely disrupted river-borne movement of labour, supplies and food, and compromised the livelihoods of boatmen and fishermen.[161] Transport was generally unavailable to carry seed and equipment to distant fields or rice to the market hubs, leaving farmers in great difficulty.[162] Transport costs rose, and the sudden stoppage of commerce not only caused some local industries to collapse, but also struck local areas with a supply shock on rice and fish, Bengal's two staple foods. The Army took no steps to distribute food rations to make up for the interruption of supplies.[163] Moreover, artisans and other groups who relied on boat transport to carry goods to market were offered no recompense whatsoever; neither were rice growers nor the network of migratory labourers.[164] The large-scale removal or destruction of rural boats, indispensable vehicles in the internal transport system of districts such as Khulna, 24 Parganas, Bakargunj and Tipperah, caused a near-complete breakdown of the existing transport and administration infrastructure and market system for movement of rice paddy.[165]

The policy also compounded inflationary pressures. The British administration released significant funds for cash purchases of boats; the threat of punitive force and the fear of reported Japanese war crimes against captives were also employed. Compensation was paid "lavishly" for the boats and boat crews: owners were paid "the market value of the craft [and] three months' average earnings when the boat had been used as sole means of livelihood", while "[crews] received a month's wages".[166] Many boat owners initially responded enthusiastically; authorities were able to obtain 25,000 boats within the first few days after the introduction of the policy.[167] Cash was disbursed in lump sums of one-rupee notes. These notes, however, were immediately spent on rice and cloth, both of which were already becoming scarce, since the paper they were printed on was frequently damaged by white ants.[AI] This sudden injection of cash into the local economy, and subsequent increase in demand for goods, compounded the inflationary pressures.[168]

Many of the confiscated boats disintegrated in holding areas. No steps were taken to provide for their proper maintenance or repair,[169] and many fishermen were unable to return to their trade.[164] The loss of transport was also a factor in later problems delivering relief aid to cyclone and famine victims in areas where roads were poor and other means of transport were lacking.[170] Finally, this array of harmful effects had important political ramifications as well, as the Indian National Congress and many other groups staged protests denouncing the denial policies for placing draconian burdens on the Bengali peasants; these were part of a nationalist sentiment and outpouring that later peaked in the "Quit India" movement.[171]

Mid-1942: Inter-provincial trade barriers

Many Indian provinces and princely states imposed inter-provincial trade barriers beginning in mid-1942, preventing other provinces from buying domestic rice. One underlying cause was the anxiety and soaring prices that followed the fall of Burma,[172] but a more direct impetus in some cases (for example, Bihar) was the trade imbalances directly caused by provincial price controls.[126] The power to restrict inter-provincial trade had been conferred on provincial governments in November 1941 as an item under the Defence of India Act, 1939.[AJ] Provincial governments began erecting trade barriers that prevented the flow of foodgrains (especially rice) and other goods between provinces. These barriers reflected a desire to see that local populations were well fed, thus also forestalling civil unrest.[173]

In January 1942, Punjab banned exports of wheat;[174][AK] this increased the perception of food insecurity and led the enclave of wheat-eaters in Greater Calcutta to increase their demand for rice precisely when an impending rice shortage was feared.[175] The Central Provinces prohibited the export of foodgrains outside the province two months later.[176] Madras banned rice exports in June,[177] followed by export bans in Bengal and its neighboring provinces of Bihar and Orissa that July.[178]

The Famine Inquiry Commission of 1945 characterised this "critical and potentially most dangerous stage" in the crisis as a key policy failure: "Every province, every district, every [administrative division] in the east of India had become a food republic unto itself. The trade machinery for the distribution of food [between provinces] throughout the east of India was slowly strangled, and by the spring of 1943 was dead."[179] Bengal was unable to import domestic rice; this policy helped transform market failures and food shortage into famine and widespread death.[180]

August 1942: Prioritised distribution

The British government viewed strategic problems as stemming from the loss of Burma, and serving to reinforce the importance of Calcutta, which was producing "as much as 80% of the armament, textile and heavy machinery production used in the Asian theater."[181] The paramount goal became the support of this centre of wartime mobilisation. To address this problem, they greatly expanded their use of a technique already employed since the outset of the war — prioritised distribution of goods and services.[182] The Government of India made a conscious decision to divide socioeconomic groups into "priority" and "non-priority" classes according to the relative importance of their contributions to the war effort.[183] Rather than being faced with starvation, workers in prioritised sectors – private and government wartime industries, military and civilian construction, paper and textile mills, engineering firms, the Indian Railways, coal mining, and government workers of various levels[184] — were given significant advantages and benefits. In particular, rice was preferentially provided to the workers in Calcutta's vital industries.[97][AL] To a large extent, these priority classes were composed of bhadraloks, who were upper-class or bourgeois middle-class, socially mobile, educated, urban, and sympathetic to Western values and modernisation.[185] Protecting their interests was a major concern of both private and public relief efforts.[186]

Even from the outset of the war, medicine and medical care in particular had been directed to these priority groups – particularly the military. Both public and private Indian doctors, assistant-surgeons, medical graduates, antimalaria officers, medical licentiates and other medical practitioners were transferred to military duty. The highest quality medical supplies were almost completely monopolised for the military and the prioritised classes of labourers.[187] This directly reduced levels of medical care available to the general populace, and "milked the hospitals of India to the danger-point".[188] These resources were later used to make dramatic improvements in public medical aid after the military assumed control of relief efforts in late 1943.[187] For example, between 1942 and 1943, the number of vaccinations rose by 1% in rural Bengal and 55% in urban areas; in 1944, the increases were 53.2% and 287% respectively.[189]

Then, as food prices rose and the signs of famine became readily visible around July or August 1942,[190] the Government of Bengal and the Bengal Chamber of Commerce devised a Foodstuffs Scheme that provided preferential distribution of a number of goods and services to workers in essential war industries, to prevent them from leaving their jobs, stating, "the maintenance of essential food supplies to the industrial area of Calcutta must be ranked on a very high priority among the government's wartime obligation."[191] Rice was directed away from the starving rural districts to workers in industries considered vital to the military effort – particularly in the area around Greater Calcutta.[192][AM] By December of that year, the total number of individuals covered (workers and their families) was approximately a million;[193] during the brief crisis in the aftermath of the air raids on Calcutta, this high number forced the government to seize rice by force from mills and warehouses in Greater Calcutta.[194] Essential workers also benefited from ration cards, a network of "cheap shops" which provided essential supplies at discounted rates, and direct, preferential allocation of supplies such as water, medical care, and antimalarial supplies. They also received subsidised food, free transportation, access to superior housing, regular wages and even mobile cinema units for the workers' entertainment.[195] Their workers were also frequently paid in part in weekly allotments of rice sufficient to feed their immediate families, further protecting them from inflation.[196]

Any civilians who were not members of these groups (in particular, labourers in rural areas) received severely reduced access to food and medical care, and this limited access was principally available only to those who migrated to "cities and selected district towns".[92] Outside of these selected locations, "...vast areas of rural eastern India were denied any lasting state-sponsored distributive schemes" for food and medical aid,[197] placing the rural poor in direct competition for scarce supplies and basic needs with workers in public agencies, war-related industries, and in some cases even politically well-connected middle-class agriculturalists.[198] For this reason, the policy of prioritised distribution is sometimes discussed as one cause of the famine.[199]

The workers in prioritised industries in Calcutta were not living in luxury or even necessarily in comfort. Even with all their advantages, a great many urban poor were living near the subsistence level.[200] They were, however, far more shielded from the dangers of starvation, disease, and death.

August 1942: Civil unrest

By early 1942, Allied leaders such as American president Franklin Roosevelt and Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek had expressed support for the nationalist cause in India.[201] In Britain itself, the Labour Party had been committed to a peaceful transfer of political power in India to an elected Indian body.[202] British prime minister Winston Churchill responded to the new pressure by publicly taking a more conciliatory position toward India, broaching the post-war possibility of an autonomous political status for India of the kind that then existed in Canada and Australia.[203] He sent Stafford Cripps, cabinet member and leader of the House of Commons, to India to make the offer dominion status after the war in exchange for Indian support for the prosecution of the war, and participation in a government of national unity in India.[204] Privately, Churchill explained to the Viceroy of India, Lord Linlithgow, that if no agreement was reached the American critics would very likely blame the Indians.[205] According to historian Judith M. Brown, "Cripps' brief was never clarified before he left London," allowing Linlithgow to interfere indirectly in the negotiations.[AN] The Indian National Congress, which wanted the Defense portfolio in the national government, felt the Cripps offer to be both insufficient to their demands and lacking in good faith.[AO] The British, for their part, felt the Congress was demanding too much.[AP] After two weeks of negotiations, in early April 1942, the Cripps offer was rejected by the Congress. In Britain, the failure of the Cripps talks resulted in the British political elite, including that in the Labour party, reconciling themselves to the authoritarian rule that was imposed in India for the remainder of the war.[208] In India, the ordinary members of the Indian National Congress were, according to historians Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper, "now dangerously angry."[207]

Although there were Congress members who opposed Germany and Japan on principle, they soon came around to adopting Gandhi's stance that the British should leave India immediately.[209] On 8 August 1942, the Indian National Congress, at its meeting in Bombay, launched the Quit India movement, intended to be a gradually escalating India-wide display of nonviolent resistance.[209] However, the British authorities, overnight, imprisoned the entire senior leadership of the Congress, retaining them in prison for nearly two years.[210] Without its leadership, the movement evolved into a grassroots one which took to sabotaging factories, bridges, telegraph- and railway lines,[210] and government property, including post-offices and police stations,[211] and otherwise threatening the British Raj's machinery of control over India,[211] as well as its war enterprise.[210] In response, the Raj—deploying 52 army battalions, most of which were composed of British nationals or Gurkhas—forcefully and rapidly suppressed the movement, arresting tens of thousands of Indians, killing some 2,500, publicly flogging many and occasionally torturing some, torching entire villages, and patrolling some affected areas with air force bombers.[210] The centers of major conflagrations were Bihar, eastern UP, and Bombay.[211] In some other regions of India, such as Bengal, Orissa, and Gujarat, the movement was less intense but more prolonged.[212] For a short time, disruption of communications in Bihar had the effect of isolating Assam and Bengal from the rest of India.[211] In Great Britain, the Labour Party, a supporter of decolonization in India, turned against the Quit India movement, as the latter was seen impeding the war against fascism; the Conservatives, according to historian D. N. Panigrahi, "ever antagonistic to the Indian National Congress, were wild with rage. ... perhaps never to be reconciled to the idea of independence for India.[213] According to historians Bayly and Harper, quite apart from the exigencies of war, it was difficult not to conclude, that the Churchill war ministry and Winston Churchill himself had a visceral hostility toward India; "The prime minister believed that Indians were the next worst people in the world after the Germans. Their treachery had been plain in the Quit India movement. The Germans he was prepared to bomb into the ground. The Indians he would starve to death as a result of their own folly and viciousness."[214]

In Bengal, the movement was strongest in the Tamluk- and Contai subdivisions of Midnapore district,[212] where rural discontent was deep.[215] In Tamluk, the government had destroyed some 18,000 boats in pursuit of its denial policy in April 1942; in addition, the war-related inflation had further alienated the rural population, which became a bank of eager volunteers when local Congress recruiters came proposing an open rebellion.[216] Beginning on 8 September 1942, and for the next three weeks, the civil administration in Tamluk became increasingly paralyzed, and in the end the army had to be called in to suppress the movement.[216] Confrontations in Tamluk resulted in the deaths of 44, including Matangini Hazra, a 71-year-old woman who would later become a folk hero of the anti-colonial movement.[217] Newspapers supporting the Quit India movement in Bengal were either censored or forced to close by the British authorities and their editors fined.[218] Spokesman for the opposition in Bengal's provincial legislature claimed that knowledge of the intensity of the famine was kept from the people because the press was stifled and there was a ban on public assembly.[218] However, many major newspapers such as The Statesman and the Amrit Bazar Patrika did continue to be published and later reported on the famine.[219] The mistrust between the government and Indian businesses grew during 1942–45, the government suspecting Indian businesses of financing the Quit India unrest, the businesses suspecting the government of limiting their earnings in the war-related works and preserving the British commercial predominance in India.[220] The government also attempted to address the concerns of Calcutta's "priority class" with selective distribution of economic benefits, which altered their behaviour, but not their attitudes.[220] The disorder and distrust that were the effects and after-effects of rebellion and civil unrest placed political, logistical, and infrastructural constraints on the Government of India that contributed to later famine-driven woes.[221]

October 1942: Natural disasters

Later in the same year, five natural disasters struck: first, the winter rice crop was afflicted by a lengthy and virulent outbreak of fungal brown spot disease (caused by the fungus Cochliobolus miyabeanus[AQ]). During this outbreak, a cyclone and three storm surges in October ravaged croplands, destroyed houses, and killed thousands. The cyclone also dispersed high levels of fungal spores widely across the region, increasing the spread of the crop disease.

The aman rice seasonal cultivar (the main winter crop) of 1942 was ravaged, though the degree of damage is a matter of debate.[222] Unusually warm, cloudy, and humid climatic conditions and above-average rainfall lasted two months later than average (through November), during critical stages of the rice crop's maturation. This weather pattern triggered "a massive release of disease spores at the exact time that rice plants were most susceptible to infection."[223] The fungus reduced the yield even more than the cyclone.[AR] According to Padmanabhan (1973), conditions were optimal for brown spot disease, and the resulting outbreak was so destructive that "nothing as devastating ... has been recorded in plant pathological literature."[224][AS]

The Bengal cyclone of 16 October 1942 came through the Bay of Bengal, landing on the coastal areas of Midnapore and 24 Parganas,[225] reportedly causing around 40,000 fatalities and extensive damage, especially in the area around Contai.[226] The cyclone killed 14,500 people and 190,000 cattle; reserve rice paddy stocks in the hands of cultivators, consumers, and dealers were destroyed.[227] It also created local atmospheric conditions that contributed to an increased incidence of malaria.[228] Then on October 16–17, three storm surges destroyed the seawalls of Midnapore and flooded large areas of Contai and Tamluk.[170] Waves swept an area of 450 square miles (1,200 km2), floods affected 400 square miles (1,000 km2), and wind and torrential rain damaged 3,200 square miles (8,300 km2). For nearly 2.5 million Bengalis, the accumulative damage of the cyclone and storm surges to homes, crops and livelihoods was severe:[229]

Corpses lay scattered over several thousand square miles of devastated land. 7,400 villages were partly or wholly destroyed by the storm, and standing flood waters remained for weeks in at least 1,600 villages. Cholera, dysentery and other water-borne diseases flourished. 527,000 houses and 1,900 schools were lost. Over 1000 square miles of the most fertile paddy land in the province was entirely destroyed, and the standing crop over an additional 3000 square miles was damaged.[230]

Cyclones, floods, plant disease and warm, humid weather combined to have a substantial impact on the aman rice crop of 1942.[231] The impact was felt in other aspects as well, as in some districts the cyclone was responsible for an increased incidence of malaria, with deadly effect.[232]

October 1942: Unreliable crop forecasts

"Material relating to the economic life of the rural population was meagre," asserts Mahalanobis, Mukherjea & Ghosh (1946, p. 338), "and reliable information relating to the famine was simply not available."[AT] As early as October 1942, crop forecasts for the coming year predicted a significant shortfall.[233] Traders began to warn of an impending famine,[234] but the Bengal Government did not act on those predictions, apparently doubting their credibility.[235] There were several reasons for this. First, administrators and statisticians had known for decades that India's agricultural production statistics were unreliable and incomplete[236] and "not merely guesses, but frequently demonstrably absurd guesses".[237] The official statistics were riddled with "elements of negligence and incompetence, of subjectivity and conservatism, of corruption and absurdity ... indifference and genuine perplexity [at the complexity of the task]".[238] Second, there was little or no internal bureaucracy for creating and maintaining such reports, and the low-ranking police officers or village officials charged with gathering local statistics were often poorly supplied with maps and other necessary information, poorly educated, and poorly motivated to be accurate.[239] Moreover, the already haphazard rural administration went through an increasing process of collapse through 1941 and 1942; many of these local officials went unpaid for long periods of time.[240] Third, these forecasts had predicted a shortfall several times in previous years, but no significant problems had occurred.[241] Finally, given the general poverty of the area, there were many other pressing needs that demanded greater attention than the collection of statistics.[238]

December 1942: Air raids on Calcutta

The Famine Inquiry Commission's Report on Bengal (1945) discussed different potential causes and contributing factors for the famine, but singled out one event as its moment of inception: the first Japanese air raid on Calcutta on 20 December 1942. The first raid involved scores of aircraft flying over the city in broad daylight, largely unchallenged by Allied defences. Raids continued throughout that week, triggering a panicked exodus of thousands from the city.[242] As evacuees travelled to the countryside, foodgrain dealers in the city closed their shops. The Bengal government tried to ensure that workers in the prioritised industries in Calcutta would be fed. To meet this goal, they seized rice stocks from wholesale dealers. This shattered any trust the rice traders had in the government, making all later central actions considerably less effective.[243] "From that moment," the 1945 report stated, "the ordinary trade machinery could not be relied upon to feed Calcutta. The [food security] crisis had begun."[244]

1942–43: Shortfall and carryover

Even from the time of the famine, it was debated whether the crisis was caused by a crop shortfall in the aman harvest of late 1942 or by a failure in distribution of a rice harvest which was nearly sufficient to feed the populace of Bengal.[245] The most influential and widely accepted analysis belongs to Amartya Sen,[246] who concluded: "The current [rice paddy] supply for 1943 was only about 5% lower than the average of the preceding five years. It was, in fact, 13% higher than in 1941, and there was, of course, no famine in 1941."[247] The Famine Commission Report concluded that the overall deficit in rice in Bengal in 1943, taking into account an estimate of the amount of carryover of rice from the previous harvest,[AU] was about three weeks supply. Even under normal circumstances, this would have been a significant shortfall requiring a considerable amount of food relief, but not a deficit large enough to create widespread deaths by starvation.[248] According to this view, the famine "was not a crisis of food availability, but of the [unequal] distribution of food and income."[249]

Several contemporary experts cite evidence of a much larger shortfall, however.[250] Wallace Aykroyd, who had been a member of the Commission, wrote in 1975 that there had been a 25% shortfall in the harvest of the winter of 1942, exacerbated by increased exports, decreased imports, and a drain on the carryover of that year.[251] L. G. Pinnell, director of the Department of Civil Supplies (DCS) of the Government of Bengal, was responsible for managing food supplies from August 1942 to April 1943. He estimated the crop loss at 20%, with crop disease accounting for more of the loss than the cyclone; other government sources privately admitted the shortfall was "2 million tons".[252] Rutger's University economist George Blyn argues that the Midnapur cyclone and floods of October 1942 plus the loss of imports from Burma caused the famine; he asserts the Bengal rice harvest had been reduced by one-third.[253] These figures have been debated online by experts as recently as 2010.[254][AV]

1942–43: Price shocks and policy failures

In April 1942, a jump in local inflation started in the regions of south-eastern Bengal falling under the boat denial policy.[255][failed verification] All throughout that month, British and Indian refugees continued pouring out of Burma (many through the same southeast region, near Chittagong), and provinces affected by the cessation of Burmese imports were bidding up rice prices across India. The steep inflation spread across the rest of Bengal, especially in May and June;[120] prices soon rose five to six times higher than they had been before April.[256] In June, the Government of Bengal decided to establish price controls, but by the time the order took effect on 1 July, the fixed price was already considerably below market prices.[257] The provincial government ordered a ban on exports out of Bengal two weeks later, then raised the controlled price slightly one week after that.[177]

The principal result of the fixed low price was to make sellers reluctant to sell – stocks disappeared, either into the black market or into storage. In the face of this obvious policy failure, the government let it be known that the price control law would not be enforced except in the most egregious cases of war profiteering.[120] This created about four months of relative price stability.[234]

In mid-October southwest Bengal was struck by a series of natural disasters that destabilised prices again.[234] The Famine Commission Report blamed the soaring inflation of that November and December on heavy speculative buying.[234] There was another rushed scramble in the rice market – this time, to smuggle grain out of provinces with trade barriers to the black market in Calcutta.[258] Between December 1942 and March 1943, the government attempted three times to "break the Calcutta market" by bringing in rice supplies from various districts around the province.[259] These schemes essentially amounted to seizing rice, then repaying the "sellers" at the low, officially sanctioned price.[AW] All three schemes failed to significantly improve the situation.[259]

On 11 March 1943, the provincial government officially rescinded its order fixing price controls,[260] permitting buyers to purchase rice at any price.[261] The results were immediate and dramatic: very sharp rises in the price of rice, [261] including a doubling within two weeks.[262] The period of inflation between March and May 1943 was especially intense;[263] May was the month of the first reports of death by starvation in Bengal.[264] Several neighbouring provinces promised food aid in March, but all backed out, except for Orissa.[265] Between April and May 1943, the provincial government attempted a propaganda drive to boost public confidence that there was enough rice in Bengal to feed all its people; it repeatedly asserted that the crisis was being caused almost solely by speculation and hoarding.[266] The propaganda, which has been described as particularly inept,[139] failed to dispel the widespread belief that there was a shortage of rice.[AX]

Inter-provincial trade barriers were abolished on 18 May. Free trade caused prices to drop temporarily in Calcutta, but they soared in the neighbouring provinces of Bihar and Orissa, as Bengali traders rushed to purchase stocks.[267] In the first week of June 1943 (during this free trade period), the government attempted a "food drive" – an attempt to locate and seize any hoarded stocks – everywhere in the province except Calcutta and Howrah. Then in the first week of July, a second food drive covered areas previously untouched. Both food drives failed to find significant hoarding.[268] This failure directly contradicted strident propaganda that the crisis was solely caused by hoarding and further eroded public confidence in the government. This in turn strengthened the dread of a calamitous food shortage, far worse than previously imagined.[269] Free trade was abandoned in late July and early August 1943 due to the rapid rise in prices in the neighbouring provinces.[270]

Price controls were reinstated in August.[260] Despite this, there were unofficial reports of rice being sold in late 1943 at roughly eight to ten times the prices of late 1942[271] – prices that had even then been many times higher than they were in 1941.[AY] Purchasing agents were sent out by the government to obtain rice, but their attempts largely failed. Prices remained high, and the black market was not brought under control.[260]

Finally, despite having a long-established and detailed Famine Code that would have triggered a sizable increase in aid, the provincial government never formally declared a state of famine. The official explanation was three-fold: first, the declaration would have directly contradicted the propaganda drive, undermining its wartime political goals. Second, even if a state of famine had been declared, the inter-provincial trade barriers would have prevented the provincial government from obtaining the amounts that the Famine Code's provisions dictated. Third, the government did provide various other types of relief efforts.[82]

1942–44: Refusal of imports

From late 1942 through at least early 1944, several high-ranking government officials and military officers made repeated requests for food to be imported from outside India, but the War Cabinet persistently either rejected the requests outright or bargained them down to a fraction of the original amount.[272] Viceroy Linlithgow began making appeals in mid-December 1942 for the Secretary of State for India, Leo Amery, to request food imports. At first, the requests adopted a nearly apologetic tone, with assurances that the military would be given preference over civilians when imports were distributed.[AZ] In the first week of January, Amery sent the first of many requests to the UK for food aid in the form of direct imports. Rather than mentioning worsening conditions in the countryside, Amery stressed that Calcutta's industries must be fed or its workers would return to the countryside to help their families. Rather than meeting this request, the UK promised a relatively small amount of wheat that was specifically intended for western India (that is, not for Bengal) in exchange for an increase in rice exports from Bengal to Ceylon.[273]

The tone of Linlithgow's warnings to Amery grew increasingly serious over the coming months, as did Amery's requests to the War Cabinet; on 4 August 1943[BA] – less than three weeks before The Statesman's graphic photographs of starving famine victims in Calcutta would focus the world's attention on the severity of the crisis[274] – Amery noted the spread of famine, and specifically stressed the effect upon Calcutta and the potential effect on the morale of European troops. The cabinet again offered only a relatively small amount, explicitly referring to it as a token shipment.[275]

A similar cycle of refusal continued through 1943 and into 1944.[276] The explanation for these repeated refusals was invariably that the Allies had insufficient shipping,[277] particularly in light of their plans to invade Normandy[278] – but this rationale has been debated. The Cabinet also refused offers of food shipments from several different nations.[BB] When such shipments did begin to increase modestly in late 1943, the transport and storage facilities were understaffed and inadequate.[BC]

Famine, disease, and the death toll

It is not possible to assign a definitive starting date to the actual onset of the famine, particularly since different districts in Bengal were affected at different times and to considerably varying degrees. The Government of India dated the beginning of a food crisis to the consequences of the air raids on Calcutta in December 1942,[244] and the beginning of full-scale famine to May 1943 as the consequence of price decontrol two months earlier.[280] In some districts, the food crisis began as early as mid-1942,[281] but the rural poor were able to draw upon various coping strategies[BD] for a few months.[282] Some then felt the signs of incipient famine as early as December 1942, when reports from commissioners and district officers of various districts in Bengal began to cite a "sudden and alarming" inflation, nearly doubling the price of rice; this was followed in January by reports of distress over serious food supply problems.[283] In May 1943, six districts – Rangpur, Mymensingh, Bakarganj, Chittagong, Noakhali and Tipperah – were the first to report deaths by starvation. Chittagong and Noakhali, both "boat denial" districts in the Ganges Delta (or Sundarbans Delta) area, were the hardest hit.[264] Dyson (1991) dates the beginning of the famine's excess mortality to the following month. Deaths began showing up later in other geographical areas; some districts of Bengal, however, were relatively less affected throughout the crisis.[284] Although no demographic or geographic group was completely immune to increased rates of death by disease, only the rural poor died of starvation.[285]