Butte, Montana

Butte-Silver Bow, Montana | |

|---|---|

Butte viewed from the campus of Montana Tech | |

| Nickname: Butte America | |

| Motto: The Richest Hill on Earth | |

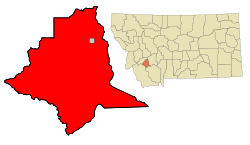

Location of Butte in Montana | |

Map of Silver Bow County showing Butte highlighted in grey | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Silver Bow |

| Area | |

| 716.8 sq mi (1,867.6 km2) | |

| • Land | 716.1 sq mi (1,854.7 km2) |

| • Water | 0.7 sq mi (1.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 5,538 ft (1,688 m) |

| Population | |

| 33,525 | |

• Estimate (2015)[3] | 33,922 |

| • Metro | 34,680 |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 59701, 59702, 59703, 59707, 59750 |

| Area code | 406 |

| FIPS code | 30-11397 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2409651[1] |

| Website | http://co.silverbow.mt.us |

Butte /ˈbjuːt/ is a city in, and the county seat of Silver Bow County, Montana, United States.[4] In 1977, the city and county governments consolidated to form the sole entity of Butte-Silver Bow. As of the 2010 census, Butte's population was approximately 34,200. Butte is Montana's fifth largest city.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Butte experienced every stage of development of a mining town, from camp to boomtown to mature city to center for historic preservation and environmental cleanup. Unlike most such towns, Butte's urban landscape includes mining operations set within residential areas, making the environmental consequences of the extraction economy all the more apparent. Despite the dominance of the Anaconda Company, Butte was never a company town. It prided itself on architectural diversity and a civic ethos of rough-and-tumble individualism. In the 21st century, efforts at interpreting and preserving Butte's heritage are addressing both the town's historical significance and the continuing importance of mining to its economy and culture.[5]

Butte was one of the largest cities in the Rocky Mountains in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Silver Bow County (Butte and suburbs) had 24,000 people in 1890, and peaked at 100,000 in 1920[citation needed]. The population steadily declined with falling copper prices after World War I, eventually dropping to 34,000 in 1990 and stabilized. In 2013, the population remains at 34,200. In its heyday from the late 19th century to circa 1920, it was one of the largest and most notorious copper boomtowns in the American West, home to hundreds of saloons and a famous red-light district. The documentary Butte, America, depicts its history as a copper producer and the issues of labor unionism, economic rise and decline, and environmental degradation that resulted from the activity.

The city is served by Bert Mooney Airport with airport code BTM.

History

Butte began as a mining town in the late 19th century in the Silver Bow Creek Valley (or Summit Valley), a natural bowl sitting high in the Rockies straddling the Continental Divide. At first only gold and silver were mined in the area, but the advent of electricity caused a soaring demand for copper, which was abundant in the area. The small town was often called "the Richest Hill on Earth". It was the largest city for many hundreds of miles in all directions. The city attracted workers from Cornwall (United Kingdom),[6] Ireland, Wales, Lebanon, Canada, Finland, Austria, Serbia, Italy, China, Syria, Croatia, Montenegro, Mexico, and all areas of the U.S. The legacy of the immigrants lives on in the form of the Cornish pasty which was popularized by mine workers who needed something easy to eat in the mines, the povitica—a Slavic nut bread pastry which is a holiday favorite sold in many supermarkets and bakeries in Butte — and the boneless porkchop sandwich. These, along with huckleberry products and Scandinavian lefse have arguably become Montana's symbolic foods, known and enjoyed throughout Montana. In the ethnic neighborhoods, young men formed gangs to protect their territory and socialize into adult life, including the Irish of Dublin Gulch, the Eastern Europeans of the McQueen Addition, and the Italians of Meaderville.[7]

Among the migrants, many Chinese workers moved in, and amongst them set up businesses that led to the creation of a Chinatown in Butte. The Chinese migrations stopped in 1882 with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. There was anti-Chinese sentiment in the 1870s and onwards due to racism on the part of the white settlers, exacerbated by economic depression, and in 1895, the chamber of commerce and labor unions started a boycott of Chinese owned businesses. The business owners fought back by suing the unions and winning. The history of the Chinese migrants in Butte is documented in the Mai Wah Museum.[8][9]

The influx of miners gave Butte a reputation as a wide-open town where any vice was obtainable. The city's famous saloon and red-light district, called the "Line" or "The Copper Block", was centered on Mercury Street, where the elegant bordellos included the famous Dumas Brothel. Behind the brothel was the equally famous Venus Alley, where women plied their trade in small cubicles called "cribs". The red-light district brought miners and other men from all over the region and was open until 1982 as one of the last such urban districts in the U.S. The Dumas Brothel is now operated as a museum to Butte's rougher days. Close by Wyoming Street is home to the Butte High School (home of the "Bulldogs").

At the end of the 19th century, copper was in great demand because of new technologies such as electric power that required the use of copper. Three men fought for control of Butte's mining wealth. These three "Copper Kings" were William A. Clark, Marcus Daly, and F. Augustus Heinze.

In 1899, Daly joined with William Rockefeller, Henry H. Rogers, and Thomas W. Lawson to organize the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company. Not long after, the company changed its name to Anaconda Copper Mining Company (ACM). Over the years, Anaconda was owned by assorted larger corporations. In the 1920s, it had a virtual monopoly over the mines in and around Butte. Between approximately 1900 and 1917, Butte also had a strong streak of Socialist politics, even electing a Mayor on the Socialist ticket in 1914.

The prosperity continued up to the 1950s, when the declining grade of ore and competition from other mines led the Anaconda company to switch its focus from the costly and dangerous practice of underground mining to open pit mining. This marked the beginning of the end for the boom times in Butte.

Labor organizations

Butte was also known as "the Gibraltar of Unionism", with a very active labor union movement that sought to counter the power and influence of the Anaconda company, which was also simply known as "The Company."

By 1885, there were about 1,800 dues-paying members of a general union in Butte. That year the union reorganized as the Butte Miners' Union (BMU), spinning off all non-miners to separate craft unions. Some of these joined the Knights of Labor, and by 1886 the separate organizations came together to form the Silver Bow Trades and Labor Assembly, with 34 separate unions representing nearly all of the 6,000 workers around Butte.[10] The BMU established branch unions in mining towns like Barker, Castle, Champion, Granite, and Neihart, and extended support to other mining camps hundreds of miles away.

In 1892 there was a violent strike in Coeur d'Alene.[11] Although the BMU was experiencing relatively friendly relations with local management, the events in Idaho were disturbing. The BMU not only sent thousands of dollars to support the Idaho miners, they mortgaged their buildings to send more.[12]

There was a growing concern that local unions were vulnerable to the power of Mine Owners' Associations like the one in Coeur d'Alene. In May 1893, about forty delegates from northern hard-rock mining camps met in Butte and established the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), which sought to organize miners throughout the West.[13] The Butte Miners' Union became Local Number One of the new WFM.[14] The WFM won a strike in Cripple Creek, Colorado, the following year, but then in 1896–97 lost another violent strike in Leadville, Colorado, prompting the Montana State Trades and Labor Council to issue a proclamation to organize a new Western labor federation[15] along industrial lines.

After 1905, Butte became a hotbed of Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or the "Wobblies") organizing. There were a number of clashes between laborers, labor organizers, and the Anaconda company, including the 1917 lynching of IWW executive board officer Frank Little. In 1920, company mine guards gunned down strikers in the Anaconda Road Massacre. Seventeen were shot in the back as they tried to flee, and one man died.[16]

Copper production

In 1917, copper production from the Butte mines peaked and steadily declined thereafter. By WWII, copper production from the ACM's holdings in Chuquicamata, Chile, far exceeded Butte's production. The historian Janet Finn has examined this "tale of two cities"—Butte and Chuquicamata as two ACM mining towns.

Beer production

Commercial breweries first opened in Butte in the 1870s; they were usually run by German immigrants, including Leopold Schmidt, Henry Mueller, and Henry Muntzer. The breweries were always staffed by union workers. Most ethnic groups in Butte, from Germans and Irish to Italians and various Eastern Europeans, including children, enjoyed the locally brewed lagers, bocks, and other types of beer. By the 1960s, major national brands dominated the market, including Budweiser, Miller and Coors; by the 1990s, however, small microbreweries in Butte and nearby cities found a niche market, and international imports became widely available.[17]

The open-pit era

Since the 1950s, five major developments have occurred: the Anaconda's decision to begin open-pit mining in the mid-1950s; a series of fires in Butte's business district in the 1970s; a debate over whether to relocate the city's historic business district; a new civic leadership; and the end of copper mining in 1983. In response, Butte looked for ways to diversify the economy and provide employment. The legacy of over a century of environmental degradation has, for example, produced some jobs. Environmental cleanup in Butte, designated a Superfund site, has employed hundreds of people.[18]

Thousands of homes were destroyed in the Meaderville suburb and surrounding areas, McQueen and East Butte, to excavate the Berkeley Pit, which opened in 1955 by Anaconda Copper. At the time, it was the largest truck-operated open pit copper mine in the United States. Other open pit mines were dug in the area, including the still-operational East Continental Pit. The Berkeley pit grew with time until it bordered the Columbia Gardens, a large fairground established by Montana businessman William A. Clark. After the Gardens caught fire and burned to the ground in November 1973, the pit was expanded into the site. In 1977 the ARCO (Atlantic Richfield Company) company purchased Anaconda Mining, and only three years later started shutting down mines due to lower metal prices. In 1982, all mining in the Berkeley Pit was suspended. In 1983, an organization of low income and unemployed residents of Butte formed to fight for jobs and environmental justice; the Butte Community Union produced a detailed plan for community revitalization and won substantial benefits, including a Montana Supreme Court victory striking down as unconstitutional State elimination of welfare benefits.[19]

Anaconda stopped mining at the Continental Pit in 1983. Montana Resources LLP bought the property and reopened the Continental pit in 1986. The company stopped mining in 2000, but resumed in 2003 with higher metal prices, and continues at last report, employing 346 people. From 1880 through 2005, the mines of the Butte district have produced more than 9.6 million metric tons of copper, 2.1 million metric tons of zinc, 1.6 million metric tons of manganese, 381,000 metric tons of lead, 87,000 metric tons of molybdenum, 715 million troy ounces (22,200 metric tons) of silver, and 2.9 million ounces (90 metric tons) of gold.[20]

When mining shut down at the Berkeley pit in 1982, water pumps in nearby mines were also shut down, which resulted in highly acidic water laced with toxic heavy metals filling up the pit. Only two years later the pit was classified as a Superfund site and an environmental hazard site. Meanwhile, the acidic water continued to rise. It was not until the 1990s that serious efforts to clean up the Berkeley Pit began. The situation gained even more attention after as many as 342 migrating geese chose the pit lake as a resting place, resulting in their deaths. Steps have since been taken to prevent a recurrence, including but not limited to loudspeakers broadcasting sounds to scare off waterfowl. However, in November 2003 the Horseshoe Bend treatment facility went online and began treating and diverting much of the water that would have flowed into the pit. Ironically, the Berkeley Pit is also one of the city's biggest tourist attractions. It is the largest pit lake in the United States, and is the most costly part of the country's largest Superfund site.

Recent history

Around 20 of the headframes still stand over the mine shafts, and the city still contains thousands of historic commercial and residential buildings from the boom times, which, especially in the Uptown section, give it a very old-fashioned appearance, with many commercial buildings not fully occupied. As with many industrial cities, tourism and services, especially health care (Butte's St. James Hospital has Southwest Montana's only major trauma center), are rising as primary employers. Many areas of the city, especially the areas near the old mines, show signs of urban blight but a recent influx of investors and an aggressive campaign to remedy blight has led to a renewed interest in restoring property in Uptown Butte's historic district, which was expanded in 2006 to include parts of Anaconda and is now the largest National Historic Landmark District in the United States with nearly 6,000 contributing properties.

A century after the era of intensive mining and smelting, the area around the city remains an environmental issue. Arsenic and heavy metals such as lead are found in high concentrations in some spots affected by old mining, and for a period of time in the 1990s the tap water was unsafe to drink due to poor filtration and decades-old wooden supply pipes. Efforts to improve the water supply have taken place in the past few years, with millions of dollars being invested to upgrade water lines and repair infrastructure. Environmental research and clean-up efforts have contributed to the diversification of the local economy, and signs of vitality remain, including a multimillion-dollar polysilicon manufacturing plant locating nearby in the 1990s and the city's recognition and designation in the late 1990s as an All-American City and also as one of the National Trust for Historic Preservation's Dozen Distinctive Destinations in 2002. In 2004, Butte received another economic boost as well as international recognition as the location for the Hollywood film Don't Come Knocking, directed by renowned director Wim Wenders and released throughout the world in 2006.

The annual celebration of Butte's Irish heritage (since 1882) is the annual St. Patrick's Day festivities. In these modern times about 30,000 revelers converge on Butte's Historic Uptown District to enjoy the parade led by the Ancient Order of Hibernians and celebrate in bars such as Maloney's, the Silver Dollar Saloon, M&M Cigar Store, and The Irish Times Pub.

Butte is one of the few cities in the United States where possession and consumption of open containers of alcoholic beverages are allowed on the street (although not in vehicles).[21][22][23][24]

A larger annual celebration is Evel Knievel Days, held on the last weekend of July. This event draws over 50,000 motor sport enthuisasts and fans of Evel Knievel from around the world.[25]

Butte is perhaps becoming most renowned for the regional Montana Folk Festival[26] held on the second weekend in July. In 2013, this event attracted 170,000 attendees for the three-day celebration of traditional music, art,dance and cuisine. This event began its run in Butte as the National Folk Festival from 2008 to 2010 and in 2011 made the transition to the largest free-of-admission music festival in Montana and, most likely, in the Pacific Northwest.

Butte's Fourth of July Parade and Fireworks show is the largest in the state. In 2008 Barack Obama spent his last Fourth of July before his Presidency campaigning in Butte, taking in the parade with his family, and celebrating his daughter Malia Obama's 10th birthday.[27]

Granite Mountain/Speculator Mine Disaster

Sparked by a tragic accident more than 2,000 feet (600 m) below the ground on June 8, 1917, a fire in the Granite Mountain shaft spewed flames, smoke, and poisonous gas through the labyrinth of underground tunnels including the connected Speculator mine. A rescue effort commenced, but the carbon monoxide was stealing the air supply. A few men built man-made bulkheads to save their lives, but many others died in a panic to try to get out. Rescue workers set up a fan to prevent the fire from spreading. This worked for a short time, but when the rescuers tried to use water, the water evaporated, creating steam that burned people trying to escape. Once the fire was out, those waiting to hear the news on the surface could not identify the victims. They were too mutilated to recognize, leading many to assume the worst. Of the 168 bodies removed from the mine, most had died due to lack of oxygen and smoke inhalation as opposed to the actual fire itself. Due to the heroic efforts of men such as Ernest Sullau, Manus Duggan, Con O'Neil, and J. D. Moore, some survived to tell the tale. The Granite Mountain Memorial was built as a reminder of the greatest loss of life in US hard rock mining history, a title that still holds true. The disaster was also memorialized in the song, "Rox in the Box" on the album The King is Dead by the indie rock band, The Decemberists.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 716.8 sq mi (1,856.5 km2), of which 716.1 sq mi (1,854.7 km2) is land and 0.66 sq mi (1.7 km2) (0.09%) is water. Butte is also home to one of the largest deposits of bornite. Of all U.S. communities situated on the Continental Divide, Butte is the most populous. Every highway exiting Butte (except westbound I-90) crosses the Divide (eastbound I-90 via Homestake Pass; eastbound MT 2 via Pipestone Pass; northbound I-15 via Elk Park Pass and southbound I-15 via Deer Lodge Pass).

Surrounding cities

Climate

Butte has a very exaggerated semi-arid climate (BSk) under the Köppen Climate Classification, though short of being a humid continental climate (Dfb). Winters are long and cold, January averaging at 18 °F or −7.8 °C, with 35.9 nights falling below 0 °F or −17.8 °C and 58.3 days failing to top freezing.[28] Summers are short, with very warm days and chilly nights: July averages 63 °F or 17.2 °C. Like most areas in this part of North America, annual precipitation is low and largely concentrated in the spring months: the wettest month since precipitation records began in 1894 has been June 1913 with 8.86 inches or 225.0 millimetres, whilst no precipitation fell in September 1904.[29] The wettest calendar year has been 1909 with 20.55 inches or 522.0 millimetres and the two driest 1935 with 6.89 inches or 175.0 millimetres and 1895 with 6.98 inches or 177.3 millimetres. Snowfall is somewhat limited by dryness: the most in one month being 32.5 inches or 0.83 metres in October 1911 and the greatest depth on the ground 27 inches or 0.69 metres on 28 and 29 December 1996.[29]

The coldest month has been January 1937 with a daily mean temperature of −5.5 °F (−20.8 °C), whilst the coldest complete winter was 1948/1949 with a three-month mean of 6.69 °F (−14.06 °C) and the mildest 1925/1926 which averaged 29.21 °F (−1.55 °C). July 2007 has been easily the hottest month, with a mean maximum of 88.8 °F (31.6 °C), although the hottest day, reaching 100 °F or 37.8 °C, occurred on July 22, 1931 and June 30, 2000.

| Climate data for Butte Mooney Airport, MT (1971-2000; records 1894-2001) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

61 (16) |

69 (21) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

99 (37) |

93 (34) |

85 (29) |

69 (21) |

66 (19) |

100 (38) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 29.7 (−1.3) |

34.7 (1.5) |

42.1 (5.6) |

51.6 (10.9) |

60.8 (16.0) |

70.7 (21.5) |

79.8 (26.6) |

79.0 (26.1) |

67.0 (19.4) |

55.5 (13.1) |

38.9 (3.8) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

53.4 (11.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 5.4 (−14.8) |

9.6 (−12.4) |

18.5 (−7.5) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

34.3 (1.3) |

41.4 (5.2) |

45.5 (7.5) |

44.1 (6.7) |

35.3 (1.8) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

15.3 (−9.3) |

5.7 (−14.6) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −48 (−44) |

−52 (−47) |

−36 (−38) |

−16 (−27) |

9 (−13) |

22 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

23 (−5) |

3 (−16) |

−23 (−31) |

−42 (−41) |

−52 (−47) |

−52 (−47) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.53 (13) |

0.47 (12) |

0.83 (21) |

1.02 (26) |

2.02 (51) |

2.07 (53) |

1.47 (37) |

1.36 (35) |

1.09 (28) |

0.79 (20) |

0.60 (15) |

0.53 (13) |

12.78 (324) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.4 (21) |

7.6 (19) |

10.7 (27) |

8.6 (22) |

3.3 (8.4) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

1.1 (2.8) |

4.5 (11) |

7.4 (19) |

8.3 (21) |

60.4 (152.47) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 7.9 | 6.0 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 9.4 | 9.0 | 6.1 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 7.6 | 86.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 inch) | 7.8 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 2.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 54.5 |

| Source: NOAA[28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 241 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,363 | 1,295.4% | |

| 1890 | 10,723 | 218.9% | |

| 1900 | 30,470 | 184.2% | |

| 1910 | 39,165 | 28.5% | |

| 1920 | 41,611 | 6.2% | |

| 1930 | 39,532 | −5.0% | |

| 1940 | 37,081 | −6.2% | |

| 1950 | 33,251 | −10.3% | |

| 1960 | 27,877 | −16.2% | |

| 1970 | 23,368 | −16.2% | |

| 1980 | 37,205 | 59.2% | |

| 1990 | 33,336 | −10.4% | |

| 2000 | 33,892 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 34,200 | 0.9% | |

| 2015 (est.) | 33,922 | [30] | −0.8% |

| source:[31] 2015 Estimate[3] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 33,892 people, 14,135 households, and 8,735 families residing in the city. The population density was 47.3 people per square mile (18.3/km²). There were 15,833 housing units at an average density of 22.1 per square mile (8.5/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 95.38% White, 0.16% African American, 1.99% Native American, 0.43% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.59% from other races, and 1.39% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.74% of the population.

There were 14,135 households out of which 27.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.7% were married couples living together, 10.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.2% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.32 and the average family size was 2.97.

In the city the population was spread out with 23.7% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 26.7% from 25 to 44, 23.9% from 45 to 64, and 16.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,516, and the median income for a family was $40,186. Males had a median income of $31,409 versus $21,626 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,068. About 10.7% of families and 15.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.2% of those under age 18 and 9.0% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (January 2012) |

Transportation

Serving the city, Bert Mooney Airport has commercial flights on Delta Connection Airlines.

Arts and culture

Movies featuring Butte and Butte buildings

- 1971 – Evel Knievel, Fanfare Films

- 1974 – The Killer Inside Me, Cyclone Productions

- 1985 – Runaway Train, Cannon Films

- 1989 – Lonesome Dove, RHI Productions

- 1989 – "Sold Me Down The River", music video by The Alarm. (Change album)

- 1992 – Die Vergessene Stadt, directed by Thomas Schadt. Known in translation as Butte, Montana—The Abandoned Town

- 1993 – Return to Lonesome Dove, RHI Productions.

- 1994 – The Last Ride, Ivar Productions & Mondofin B.V.

- 1996 – Beavis and Butt-head Do America, MTV Productions

- 1999 – Remembering the Columbia Gardens, KUFM-TV/Montana PBS

- 2004 – Don't Come Knocking, Wim Wenders Productions

- 2005- An Unfinished Life, Butte is mentioned towards the end.

- 2007 – Hidden Fire: The Great Butte Explosion, KUSM-TV/Montana PBS. About the 1895 explosion that destroyed Butte's warehouse district. Voice actors include Keir Dullea.

- 2008 – Butte, America: The Saga of a Hard Rock Mining Town, narrated by Gabriel Byrne

- 2010 – Butte: The Original Produced by Dick Maney and B.J. McKenzie

- 2014 - Her Beautiful Brain by Ann Hedreen

Butte in literature

- 1902 - "I Await the Devil's Coming", by Mary MacLane.

- 1914 - The Valley of Fear, Arthur Conan Doyle.

- 1929 – Red Harvest, by Dashiell Hammett.

- 1980 – The Butte Polka, by Donald McCaig.

- 1998 – Buster Midnight's Cafe, by Sandra Dallas.

- 1998 – Go By Go, by Jon A. Jackson.

- 2009 – The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet. The setting of the first third of the novel is Divide, Montana, a rural part of Butte and the hometown of its eponymous protagonist.

- 2010 – Work Song, by Ivan Doig. Set in Butte in 1919.

- 2011- "The Richest Hill On Earth" by Richard S. Wheeler

- 2013 – Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune, by Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr.

Tourist attractions

- Montana Tech, a state university specializing in the resources and engineering fields. (The giant letter "M" visible in the top photograph on this page stands for Montana Tech and was constructed in 1910.)

- MBMG Mineral Museum, on the Montana Tech campus.

- Our Lady of the Rockies Statue, a 90-foot (27 m) statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary, dedicated to women and mothers everywhere, on top of the Continental Divide, overlooking Butte

- The Berkeley Pit, a gigantic former open pit copper mine filled with toxic water. There is an observation deck on the south wall of the Berkeley Pit lake.

- The World Museum of Mining on the site of the Orphan Girl mine. Its main attraction is "Hell Roarin' Gulch" a mockup of a frontier mining town.

- There are many underground mine headframes still remaining on the hill in Butte, including the Anselmo, the Steward, the Original, the Travona, the Belmont, the Kelly, the Mountain Con, the Lexington, the Bell/Diamond, the Granite Mountain, and the Badger.

- The Dumas Brothel, widely considered America's longest running house of prostitution[33]

- Venus Alley

- Mai Wah Museum

- Rookwood Speakeasy,[34] an underground, prohibition era Speakeasy

- Copper King Mansion, a bed and breakfast/local museum and previously home to William A. Clark, one of Butte's three Copper Kings.

- The Arts Chateau, formerly the home of William Andrews Clark's son, Charles, the home was designed in the image of a French Chateau.

- The Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives stores and provides public access to documents and artifacts from Butte's rich past.[35]

- U.S. High Altitude Speed Skating Center is an outdoor speed-skating rink, one of three such rinks in the USA.

- Butte Silver Bow Public Library, located at 226 W. Broadway in uptown Butte (BSB Library has two branches, one in the mall (South Branch) and a part-time branch in the town of Melrose).[36] The Butte library was created in 1894 as "an antidote to the miners' proclivity for drinking, whoring, and gambling," designed to promote middle-class values and to promote an image of Butte as a cultivated city.[37][38]

Sports and recreation

Sports Teams from Butte

- Butte Cobras 2014– , Western States Hockey League

- Butte Copper Kings 1979–1985, 1987–2000, Pioneer Baseball League now the Grand Junction Rockies.

- Butte Irish 1996–2002, North American Hockey League now the Wichita Falls Wildcats.

- Butte Roughriders 2003–2011, Northern Pacific Hockey League.

- Butte Daredevils 2006–2008, Continental Basketball Association named for Butte born Evel Knievel, folded.

- Montana Tech Orediggers have competed in the Frontier Conference of the NAIA since the league's founding in 1952. The school hosts men's and women's basketball, football, golf, and women's volleyball.

Government

Butte and Silver Bow County are merged into one governmental body.

Superfund Site

The Upper Clark Fork River, with Butte at the headwaters, is America's largest Superfund site. This area takes in the cities of Butte, Anaconda, and Missoula. The mining and smelting activity in Butte resulted in significant contamination of the Butte Hill as well as downstream and downwind areas. The contaminated land extends along a corridor of 120 miles (190 km) that reaches to Milltown near Missoula and takes in adjacent areas such as the Anaconda smelter site. The mining and smelting operations of the Anaconda Copper Mining Corporation were the primary cause of this pollution at the headwaters of the Clark Fork River.

Between the upstream city of Butte and the downstream city of Missoula lies the Deer Lodge Valley. By the 1970s, local citizens and agency personnel were increasingly concerned over the toxic effects of arsenic and heavy metals on environment and human health. Most of the waste was created by the Anaconda Copper Mining Corporation (ACM), which merged with the Atlantic Richfield Corporation (ARCO) in 1977. Shortly thereafter, in 1983, ARCO ceased mining and smelting operations in the Butte-Anaconda area.

For more than a century, the Anaconda Copper Mining company mined ore from Butte and smelted it in Butte (prior to c. 1920) and in nearby Anaconda. During this time, the Anaconda smelter released up to 40 short tons (36 t) per day of arsenic, 1,700 short tons (1,540 t) per day of sulfur, and great quantities of lead and other heavy metals into the air (MacMillan). In Butte, mine tailings were dumped directly into Silver Bow Creek, creating a 150 miles (240 km) plume of pollution extending down the valley to Milltown Dam on the Clark Fork River just upstream of Missoula. Air and water borne pollution poisoned livestock and agricultural soils throughout the Deer Lodge Valley. Modern environmental clean-up efforts continue to this day.

Education

Public education is provided by Butte Public Schools which runs Butte High School. There is also a Catholic school. Montana Tech is a public university specializing in engineering.

Media

Radio

|

Television

Butte shares its Neilsen market with nearby Bozeman, with which it forms the 194th largest TV market in the United States. Butte has the distinction of being near the dividing line in terms of Pro-Sports markets, so the city receives both Seattle and Denver teams games on local cable TV channels.

- KXLF (Channel 4) CBS/CW affiliate. KXLF is the oldest broadcast television station in the state of Montana.

- KTVM (Channel 6) NBC affiliate. The station airs local news and commercials from Butte, most of the other programming comes from nearby KECI-TV in Missoula, Montana.

- KUSM (Channel 9) PBS affiliate. The station broadcasts out of Montana State University in Bozeman.

- KWYB (Channel 19) ABC/FOX affiliate and last of the "Big Three" networks to come into the market (1992). Prior to this Butte's ABC feeds came from KUSA-TV in Denver, Colorado and FOX from now-defunct Butte station KBTZ.

Newspapers

Butte has one local daily, a weekly paper, as well as several papers from around the state of Montana.

- The Montana Standard is Butte's daily paper. It was founded in 1928 and is the result of The Butte Miner and the Anaconda Standard merging into one daily paper. The Standard is owned by Lee Enterprises.

- The Butte Weekly is a local paper.

Notable people

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

- Colt Anderson, NFL defensive back

- Eden Atwood, jazz vocalist

- Rudy Autio, ceramist, sculptor

- John Banovich, artist

- John W. Bonner, Governor of Montana[39]

- Rosemarie Bowe, actress

- Patricia Briggs, fantasy author

- Scott Brow, MLB pitcher

- John Francis Buckley, member of the Canadian House of Commons

- Daniel Bukvich, composer; faculty, University of Idaho Moscow

- Albert J. Campbell, United States Representative from Montana[40]

- Kathryn Card, actress

- Amanda Curtis, Montana House of Representatives

- John Duykers, operatic tenor

- Barbara Ehrenreich, author

- Julian Eltinge, actor and female impersonator

- Henry Frank, businessman and Butte mayor

- George F. Grant, innovative fly tier, author, and conservationist

- Kirby Grant, actor, star of Sky King

- Karla M. Gray, Chief Justice of the Montana Supreme Court, worked in Butte

- Dashiell Hammett, author (The Maltese Falcon), once worked for Pinkerton National Detective Agency

- Bobby Hauck, college football coach

- Tim Hauck, NFL defensive back, coach

- Sam Jankovich, football player, coach, administrator

- Keith Jardine, mixed martial artist

- Rob Johnson, MLB catcher

- Helmi Juvonen, artist

- Evel Knievel, motorcycle daredevil

- Robbie Knievel, motorcycle daredevil and son of Evel

- Ella J. Knowles Haskell, first woman to practice law in Montana

- Rose Hum Lee, sociologist

- Andrea Leeds, actress

- Levi Leipheimer, Olympic cycling medalist, two-time U.S. champion

- Frank Little, union leader

- Paul B. Lowney, humorist, author of At Another Time — Growing up in Butte

- Sonny Lubick, football coach at Colorado State University 1993-2007

- Betty MacDonald, humor writer

- Mary MacLane, feminist author and "Wild Woman of Butte"[41]

- Mike Mansfield, U.S. senator from Montana and longest-serving Senate Majority Leader[42]

- Michael McFaul, US Ambassador to Russia, attended school in Butte during his childhood

- Lee Mantle, United States Senator from Montana[43]

- Judy Martz, Olympic speed skater and Governor of Montana

- Jack McAuliffe, former Green Bay Packers halfback

- Mike McGrath, Montana Attorney General

- Joseph P. Monaghan, United States Representative from Montana[44]

- Bob O'Billovich, CFL executive, former CFL player, coach, and administrator

- Robert O'Neill, Navy SEAL who is credited with killing Osama bin Laden in Operation Neptune Spear, joined in hostage rescues during the Maersk Alabama hijacking and Operation Red Wings; later a motivational speaker

- Pat Ogrin, NFL defensive lineman

- Arnold Olsen, United States Congressman from Montana

- Erin Popovich, Paralympic swimmer, gold medalist and world record holder

- Milt Popovich, professional football player

- Martha Raye, film and television actress, singer, honorary Academy Award winner

- John E. Rickards, first Lieutenant Governor of Montana[45]

- Fritzi Ridgeway, actress

- Jim Rotondi, jazz trumpeter, composer, educator

- Michael Sells, professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Chicago

- Jim Sweeney, former head football coach at Washington State University and longtime head coach at Fresno State University

- Brian Sullivan, member of the Washington House of Representatives, was born in Butte.[46]

- Montana Taylor, pianist

- George Leo Thomas, Bishop of Helena

- Jacob Thorkelson, United States Representative from Montana[47]

- John Walsh, former Lieutenant Governor of Montana, United States Senator and Adjutant General of the Montana National Guard

- Burton K. Wheeler, United States Senator from Montana[48]

- Kathlyn Williams, actress

- Bryon Wilson, skier, Olympic bronze medalist

See also

References

- ^ a b "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ a b "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Patrick Malone, "Butte: Cultural Treasure in a Mining Town," Montana Dec 1997, Vol. 47 Issue 4, pp 58–67

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=npQ6Hd3G4kgC&pg=PA243

- ^ Janet L. Finn, Mining Childhood: Growing Up in Butte, 1900-1960 (2012)

- ^ Carrie Schneider. "Remembering Butte's Chinatown". Official State of Montana Travel Information Site.

- ^ Rose Hum Lee (1948). "Social Institutions of a Rocky Mountain Chinatown". Social Forces. 27 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2307/2572452. JSTOR 2572452.

- ^ Michael P. Malone, William L. Lang, The Battle for Butte, 2006, pages 76–77.

- ^ Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood, Peter Carlson, 1983, pp. 50.

- ^ Michael P. Malone, William L. Lang, The Battle for Butte, 2006, page 77.

- ^ A History of American Labor, Joseph G. Rayback, 1966, page 233.

- ^ Michael P. Malone, William L. Lang, The Battle for Butte, 2006, page 79.

- ^ William Philpott, The Lessons of Leadville, Colorado Historical Society, 1995, page 71.

- ^ Mary Murphy, Mining cultures: men, women, and leisure in Butte, 1914–41, University of Illinois Press, 1997, page 33

- ^ Steve Lozar, "1,000,000 Glasses a Day: Butte's Beer History on Tap," Montana Dec 2006, Vol. 56 Issue 4, pp 46–56

- ^ Brian Shovers, "Remaking the Wide-Open Town: Butte at the End of the Twentieth Century," Montana Sept 1998, Vol. 48 Issue 3, pp 40–53

- ^ McCarthy, Bob J., Re-Claiming Butte: The Doctrine of Subjacent Support, 49 Mont. L. Rev. 267 (1988)

- ^ Steve J. Czehura (2006) Butte: a world class ore deposit, Mining Engineering, 9/2006, p.14–19.

- ^ John Grant Emeigh, "No open containers in Butte?", Montana Standard, February 8, 2007

- ^ John Grant Emeigh, "Open-container law important, area communities, police say", Montana Standard, July 1, 2007

- ^ Justin Post, "Officials reconsider alcohol ordinance: Open container proposal may go different way", Montana Standard, November 5, 2007

- ^ John W. Ray, "Alcohol abuse is a local epidemic", Montana Standard, November 3, 2007

- ^ Evel Knievel Days, Butte, Montana 2008

- ^ [1]

- ^ Loven, Jennifer (2008-07-05). "Play of the Day: Malia Obama's best birthday - USATODAY.com". usatoday.com. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ a b "Climatography of the United States No. 20 (1971-2000): BUTTE MOONEY AP, MT" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. February 2004. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ a b NOW; NWS Forecast Office; Missoula, Montana

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 128.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Richest Hill on Earth – A History of Butte, Montana," by Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives Staff, 2003 (CD-ROM)

- ^ "Rookwood Speakeasy". Old Butte Historical Adventures. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- ^ Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives

- ^ Butte Public Library

- ^ Ring, Daniel F. (1993). "The Origins of the Butte Public Library: Some Further Thoughts on Public Library Development in the State of Montana". Libraries & Culture. 28 (4): 430–44. JSTOR 25542594.

- ^ Catalogue of Books in the Butte Free Public Library, Butte: T.E. Butler, 1894

- ^ "Montana Governor John Woodrow Bonner". National Governors Association. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ "CAMPBELL, Albert James, (1857 - 1907)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Watson, Julia Dr. (2002). "Introduction", The Story of Mary MacLane. ISBN 1-931832-19-6.

- ^ "MANSFIELD, Michael Joseph (Mike), (1903 - 2001)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "MANTLE, Lee, (1851 - 1934)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "MONAGHAN, Joseph Patrick, (1906 - 1985)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Montana Governor John Ezra Rickards". National Governors Association. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ Votesmart.org.-Brian Sullivan

- ^ "THORKELSON, Jacob, (1876 - 1945)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "WHEELER, Burton Kendall, (1882 - 1975)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

Bibliography

- Case, Bridgette Dawn. "The women's protective union: Union women activists in a union town, 1890-1929" (PhD Dissertation. Montana State University-Bozeman, 2004) online

- Calvert, Jerry. 1988. The Gibraltar: Socialism and Labor in Butte, Montana (Helena: Montana Historical Society).

- Emmons, David. 1989. The Butte Irish: Class and Ethnicity in an American Mining Town, 1875–1925 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press).

- Everett, George. 2007. Butte Trivia (Helena, Montana: Riverbend Publishing Co.)

- Finn, Janet L. Mining Childhood: Growing Up in Butte, 1900-1960 (2012)

- Finn, Janet L. Tracing the Veins: Of Copper, Culture, and Community from Butte to Chuquicamata (1998) excerpt and text search; compares Butte with Chuquicamata, a mining town in Chile

- Gammons, Christopher H., John J. Metesh, and Terence E. Duaime. "An overview of the mining history and geology of Butte, Montana." Mine Water and the Environment 25.2 (2006): 70-75.

- Glasscock, C. B. The War of the Copper Kings: The Builders of Butte and the Wolves of Wall Street (1935)

- MacGibbon, Elma (1904). Leaves of knowledge. Shaw & Borden Co.Available online through the Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection Elma MacGibbons reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Butte and Anaconda."

- MacMillan, Donald. Smoke Wars: Anaconda Copper, Montana Air Pollution, and the Courts, 1890–1924 (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press). 2000.

- Malone, Michael P The Battle for Butte: Mining & Politics on the Northern Frontier, 1864–1906 (Montana Historical Society Press, 1981) excerpt and text search

- Malone, Michael. 1985. “The Close of the Copper Century.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 35: 69–72.

- McCarthy, Bob J. "Re-Claiming Butte: The Doctrine of Subjacent Support 49 Mont. Law Rev. 267 (1988).

- Mercier, Laurie. 2001. Anaconda: Labor, Community, and Culture in Montana’s Smelter City (University of Illinois Press).

- Murphy, Mary. 1997. Mining Cultures: Men, Women, and Leisure in Butte, 1914–1941 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press).

- Nash, June. 1979. We Eat the Mines and the Mines Eat Us (NY: Columbia University Press).

- Shovers, B., Fiege, M, Martin, F., and Quivik, F. (1991). Butte and Anaconda revisited: An overview of early-day mining and smelting in Montana. (Butte, MT: Butte Historical Society)

- Wyckoff, William. 1995. "Postindustrial Butte" The Geographical Review 85#4 pp: 478–497. in JSTOR

Pollution and toxic cleanup

- Barnett, Harold C. Toxic Debts and the Superfund Dilemma (University of North Carolina Press, 1994)

- Barry, Bridget R. "Toxic Tourism: Promoting the Berkeley Pit and Industrial Heritage in Butte, Montana." (2012). online

- Bookspan, Shelley. "Junk It, or Junket?" Public Historian (2001) 23#2 pp. 5–8 in JSTOR

- Capek, Stella M. 1992. Environmental Justice, Regulation, and the Local Community.” International Journal of Health Services 22(4):729–746.

- Chess, C. and Purcell, K. 1999. Public participation and the environment: Do we know what works? Environmental Science and Technology 33(16): 2685–2692.

- Church, Thomas W. and Robert T. Nakamura. 1993. Cleaning up the Mess: Implementation Strategies in Superfund (Washington: The Brookings Institution).

- Covello VT and Mumpower J. 1985 “Risk Analysis and Risk Management: A Historical Perspective,” Risk Analysis 5(2): 103–120.

- Edelstein, Michael R. 2003. Contaminated Communities: Coping with Residential Toxic Exposure Westview Press.

- Folk, Ellison. "Public Participation in the Superfund Cleanup Process," Ecology Law Quarterly 18 (1991), 173–221.

- Hird, J. A. 1993. “Environmental Policy and Equity: the case of Superfund.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 12: 323–343.

- Munday, Pat. 2002. “’A millionaire couldn’t buy a piece of water as good:’ George Grant and the Conservation of the Big Hole River Watershed.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 52 (2): 20–37.

- Okrusch, Chad Michael. "Pragmatism and environmental problem-solving: A systematic moral analysis of democratic decision-making in Butte, Montana" (PhD. Diss. University of Oregon, 2010) online

- Punke, Michael. 2006. Fire and Brimstone The North Butte Mining Disaster of 1917 (New York: Hyperion Books).

- Quivik, Fredric. 2004. “Of Tailings, Superfund Litigation, and Historians as Experts: U.S. v. Asarco, et al. (the Bunker Hill Case in Idaho).” The Public Historian 26 (1): 81–104.

- Probst, K. et al. 2002. “Superfund's Future: What Will It Cost?” Environmental Forum, 19 (2 ): 32–41.

- Tesh, Sylvia. 1999. “Citizen experts in environmental risk.” Policy Studies 32 (1): 39–58.

- Teske, N. 2000. "A tale of two TAGs: Dialogue and democracy in the superfund program." American Behavioral Scientist. 44 (4): 664–678.

Other

- Arco (Atlantic Richfield Company). U.d. “Clark Fork River Operable Unit—Clark Fork River Facts.” http://www.clarkforkfacts.com Accessed 03.Nov.02.

- Center for Public Environmental Oversight. 2002. “Roundtable on Long-term Management in the Cleanup of Contaminated Sites.” Report from a roundtable held in Washington, DC, 28 June 2002. http://www.cpeo.org/, accessed 19.Dec.05.

- Curran, Mary E. 1996. “The Contested Terrain of Butte, Montana: Social Landscapes of Risk and Resiliency.” Master’s thesis, University of Montana.

- Dobb, Edwin. 1999. “Mining the Past.” High Country News 31 (11): 1–10.

- Dobb, Edwin. 1996. “Pennies from Hell: In Montana, the Bill for America’s Copper Comes Due.” Harper’s Magazine (293): 39–54.

- Langewiesche, William. 2001. “The Profits of Doom—One of the Most Polluted Cities in America Learns to Capitalize on Its Contamination” The Atlantic Monthly (April 2001): 56–62.

- Levine, Mark. 1996. “As the Snake Did Away with the Geese.” Outside Magazine 21 (September 1996): 74–84.

- LeCain, Timothy. 1998. “Moving Mountains: Technology and Environment in Western Copper Mining.” PhD Dissertation, University of Delaware.

- Quivik, Frederic. 1998. “Smoke and Tailings: An Environmental History of Copper Smelting Technologies in Montana, 1880–1930.” PhD Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

- Southland, Elizabeth. 2003. “Megasites: Presentation for the NACEPT—Superfund Subcommittee.” www.epa.gov/oswer/docs/naceptdocs/megasites.pdf, accessed 22.April.05.

- St. Clair, Jeffrey. 2003. “Something About Butte.” Counterpunch, an online magazine www.counterpunch.org, accessed 3.Oct.05.

- Toole, K. Ross. 1954. “A History of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company: A Study in the Relationships between a State and its People and a Corporation, 1880–1950.” PhD Dissertation, University of California-Los Angeles.

Primary sources

- Copper Camp: Stories of the world's greatest mining town, Butte, Montana compiled by Workers of the Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Montana.

Further reading

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2005a. Region 8 – Superfund: Citizen’s Guide to Superfund. Updated 27 December 2005. www.epa.gov/ Accessed 27Dec.05.

- ______. 2005b. “EPA Region 8—Environmental Justice (EJ) Program.” Updated 24 March 2005). www.epa.gov/region8/ej/ Accessed 05.Jan.06.

- ______. 2004a. Superfund Cleanup Proposal, Butte Priority Soils Operable Unit of the Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area Superfund Site. www.epa.gov/Region8/superfund/sites/mt/FinalBPSOUProposedPlan.pdf Accessed 20.Dec.2004.

- ______. 2004b. “Clark Fork River Record of Decision,” available at http://www.epa.gov/region8/superfund/sites/mt/milltowncfr/cfrou.html.

______. 2002a. Superfund Community Involvement Toolkit. EPA 540-K-01-004.* _______. 2002b. “Butte Benefits from a $78 Million Cleanup Agreement.” Available at http://www.epa.gov/region8/superfund/sites/mt/silver_.html.

- ______. 1998. Superfund Community Involvement Handbook and Toolkit. Washington, DC: Office of Emergency and Remedial Response.

- ______. 1996. “EPA Superfund Record of Decision R08-96/112.” Available at http://www.epa.gov/superfund/sites/rods/fulltext/r0896112.pdf.

- ______. 1992. "Environmental Equity: Reducing Risk for All Communities." EPA A230-R-92-008; two volumes (June 1992).

- Society for Applied Anthropology. 2005. “SFAA Project Townsend, Case Study Three, The Clark Fork Superfund Sites in Western Montana.” www.sfaa.net Accessed 23.Nov.05.

- Montana Environmental Information Center. 2005. “Federal Superfund: EPA's Plan for Butte Priority Soils.” Available at http://www.meic.org/Butte_Superfund2005/Butte_Superfund.html.

- Murray, C. and D.R. Marmorek. 2004. “Adaptive Management: A science-based approach to managing ecosystems in the face of uncertainty.” Prepared for presentation at the Fifth International Conference on Science and Management of Protected Areas: Making Ecosystem Based Management Work, Victoria, British Columbia, May 11–16, 2003. ESSA Technologies, BC, Canada.

- National Academy of Sciences. 2005. The National Academy of Sciences Report on Superfund and Mining Megasites: Lessons from the Coeur d’Alene River Basin. Available at http://www.epa.gov/superfund/reports/coeur.htm.

- Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. 2005. “Cut and Run: EPA Betrays Another Montana Town—A Tale of Butte, the Largest Superfund Site in the United States.” News release (August 18, 2005). http://www.peer.org/news/news_archive.php, accessed 15.Sept.05.

External links

- City and County of Butte-Silver Bow

- Butte Visitors Bureau

- The Montana Standard, the local newspaper

- Butte Citizens Environmental Committee (CTEC), a Superfund Technical Assistance group

- Hidden Fire: The Great Butte Explosion Documentary produced by Montana PBS

- Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune

![]() Butte travel guide from Wikivoyage

Butte travel guide from Wikivoyage