Carrauntoohil

| Carrauntouhil | |

|---|---|

| Carrauntoohill | |

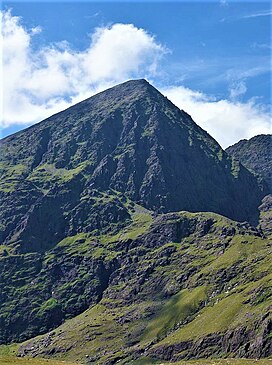

Carrauntoohil's east face (l), and north-east face (r, in shadow), as seen from the Hag's Glen | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,038.6 m (3,407 ft 6 in)[1][2][3] |

| Prominence | 1,038.6 m (3,407 ft 6 in)[1][2] |

| Isolation | 250 miles (400 km) |

| Listing | Country high point, County top (Kerry), Ribu, P600, Marilyn, Furth, Hewitt, Arderin, Simm, Vandeleur-Lynam |

| Coordinates | 51°59′58″N 9°44′34″W / 51.999445°N 9.742693°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Corrán Tuathail (Irish) |

| English translation | Tuathal's sickle |

| Geography | |

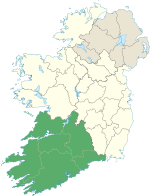

| Location | County Kerry, Ireland |

| Parent range | MacGillycuddy's Reeks |

| OSI/OSNI grid | V803844 |

| Topo map | OSI Discovery 78[1] |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | Devonian[1] |

| Mountain type(s) | Purple sandstone & siltstone, (Ballinskelligs Sandstone Formation)[1] |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Devil's Ladder (via Hag's Glen)[4] |

Carrauntoohil,[5] Carrauntoohill or Carrantuohill (/ˌkærənˈtuːəl/ KARR-ən-TOO-əl; Irish: Corrán Tuathail [ˌkɔɾˠaːn̪ˠ ˈt̪ˠuəhəlʲ], meaning "Tuathal's sickle") is the highest mountain in Ireland at 1,038.6 metres (3,407 feet 6 inches). It is on the Iveragh Peninsula in County Kerry, close to the centre of Ireland's highest mountain range, MacGillycuddy's Reeks. Carrauntoohil is composed mainly of sandstone, whose glaciation produced distinctive features on the mountain such as the Eagle's Nest corrie and some deep gullies and sharp arêtes in its east and northeastern faces that are popular with rock and winter climbers.

As Ireland's highest mountain, Carrauntoohil is popular with mountain walkers, who most commonly ascend via the Devil's Ladder route; however, Carrauntoohil is also climbed as part of longer mountain walking routes in the MacGillycuddy's Reeks range, including the 15-kilometre (9+1⁄2 mi) Coomloughra Horseshoe or the 26-kilometre (16 mi) MacGillycuddy's Reeks Ridge Walk of the entire mountain range. Carrauntoohil, and most of the range is held in private ownership and is not part of any Irish national park; however, reasonable access is granted to the public for recreational use.

Geology

[edit]Carrauntoohil is composed of sandstone particles of various sizes which are collectively known as Old Red Sandstone.[4] Old Red Sandstone has a purple-reddish colour (stained green in places), and has virtually no fossils; it dates from the Devonian period (410 to 350 million years ago) when Ireland was in a hot equatorial climate.[4][6] The sedimentary rocks of the Iveragh Peninsula are composed of three layers that are up to 7 kilometres (4+1⁄2 mi) thick (in ascending order): Lough Acoose Formation, Chloritic Sandstone Formation, and the Ballinskelligs Sandstone Formation.[4]

Carrauntoohil was later subject to significant glaciation during the last ice age, the result of which is deep fracturing of the rock, and the surrounding of Carrauntoohil by U-shaped valleys, sharp arêtes, and deep corries.[4]

Geography

[edit]

Carrauntoohil is the central peak of the MacGillycuddy's Reeks range, and has three major ridges.[7] A narrow rocky ridge, or arête, to the north, known as the Beenkeragh Ridge, contains the summit of The Bones (Na Cnámha), and leads to Ireland's second-highest peak, Beenkeragh (Binn Chaorach) at 1,008 m (3,307 ft). The ridge westward, called the Caher Ridge, also an arête, leads to Ireland's third-highest peak, Caher at 1,000 m (3,300 ft). A third and much wider unnamed south-easterly ridge, or spur, leads down to a col where sits the top of the Devil's Ladder (the classic access route for Carrauntoohil from the Hag's Glen), but then rises back up to Cnoc na Toinne 845 m (2,772 ft), from which the long easterly ridge section of MacGillycuddy's Reeks is accessed.[4][8]

Carrauntoohil overlooks three U-shaped valleys, each of which containing their own lakes. To the east of Carrauntoohil is the Hag's Glen (Irish: Com Caillí, lit. 'hollow of the Cailleach'), to the west is Coomloughra (Irish: Chom Luachra, lit. 'hollow of the rushes'), and to the south is Curragh More (Irish: Currach Mór, lit. 'great marsh').[4][8]

Carrauntoohil has a deep corrie, known as the Eagle's Nest, at its north-east face,[4] which is accessed from the Hag's Glen, and rises up through three levels. At the top, the third level, is Lough Cummeenoughter, Ireland's highest lake.[9] The Eagle's Nest gives views of the gullies on Carrauntoohil's north-east face: Curved Gully, Central Gully, and Brother O'Shea's Gully.[10] Sometimes the term Eagle's Nest is used to refer to the small stone Mountain Rescue Hut that sits on the first level of the corrie, where the Heavenly Gates descent gully meets the Eagle's Nest corrie.[4]

Carrauntoohil is the highest mountain in Ireland on all classification scales.[7][11] It is the 133rd-highest mountain, and 4th most prominent mountain, in Britain and Ireland, on the Simms classification.[11] Carrauntoohil is regarded by the Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) as one of 34 Furths, which are defined as mountains above 3,000 feet (914.4 m) in elevation and meeting the SMC criteria for a Munro (i.e. "sufficient separation"), and which are outside (or furth), of Scotland;[12] this is why Carrauntoohil is also referred to as one of the thirteen Irish Munros.[12][13]

Carrauntoohil's larger prominence qualifies it to meet the P600 classification and the Britain and Ireland Marilyn classification.[11] Carrauntoohil is the highest mountain in the MountainViews Online Database, 100 Highest Irish Mountains.[7][14]

Summit

[edit]

In the 1950s, a wooden cross was erected on the summit, a privately owned commonage, by the local community.[15] In 1976, the wooden cross was replaced by a 5 m (16 ft 5 in) steel cross. In 2014, the cross was cut down by unknown persons in protest against the Catholic Church,[16][17] but it was re-erected shortly after.[15]

Because of the dangers of the steep north-eastern and eastern faces of Carrauntoohil, the Kerry Mountain Rescue Team (KMRT) have placed danger signs on the summit, and particularly above the Howling Ridge sector (the ridge between the north-east and east faces), whose initial section can be mistaken for a hill-walkers descent route.[18][19]

Naming

[edit]Carrauntoohil is the most common and official spelling of the name, being the only version in use by Ordnance Survey Ireland,[20][21] the Placenames Database of Ireland,[22] and by Irish academic Paul Tempan, compiler of the Irish Hill and Mountain Names database (2010).[23] Carrauntoohill has also been used in the past, for example by Irish historian Patrick Weston Joyce in 1870.[24][25] Other less common spelling variations have included Carrantoohil, Carrantouhil, Carrauntouhil and Carrantuohill; all of which are anglicisations of the same Irish-language name.[25]

Paul Tempan's Irish Hill and Mountain Names notes that Carrauntoohil's Irish name "is shrouded in uncertainty", and that "Unlike some lesser peaks, such as Mangerton or Croagh Patrick, it is not mentioned in any surviving early Irish texts".[23] The official Irish name is Corrán Tuathail, which Tempan notes is interpreted as "Tuathal's sickle", Tuathal being a male first name.[23] Patrick Weston Joyce previously interpreted it as "inverted sickle",[23] translating from the Irish language term tuathail meaning left-handed but according to PWJ, "is applied to everything reversed from its proper direction".[25] From yet another perspective, one of the earliest written accounts of the mountain by Isaac Weld in 1812, calls it Gheraun-Tuel,[23] and Samuel Lewis's Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837) calls it Garran Tual;[26] suggesting the first element was géarán ('fang')—which is found in the names of other Kerry mountains—and that the earlier name may have been Géarán Tuathail ('Tuathal's fang').[23][27]

Ownership

[edit]

The climber and author Jim Ryan noted in his 2006 book Carrauntoohil and MacGillycuddy's Reeks that the actual mountain of Carrauntoohil, including most of the Hag's Glen, is in private ownership.[4] The freehold is owned by four families: Donal Doona, John O'Shea, John B. Doona, and James Sullivan. Their great-grandfathers bought the land from the Irish Land Commission, "paying the sum of eleven shillings and two pence (70 €cents in today's money), twice a year for many decades".[4] Ryan's book commended the owners for providing access over the years,[28] despite damage to their farms.[29]

A state-sponsored report into access for the range in December 2013 titled MacGillycuddy Reeks Mountain Access Development Assessment (also called the Mountain Access Project, or MAP), mapped the complex network of land titles.[6] Unlike many other national mountain ranges, MacGillycuddy's Reeks are not part of a national park or a trust structure, and are instead completely privately owned.[6]

The ownership situation has raised concerns in light of the material rise in visitors to Carrauntoohil (and the range in general), and the erosion and lack of infrastructure that other state-owned sites have been able to address.[30] In 2019 the Irish Times reported that the MacGillycuddy Reeks Mountain Access Forum, a cross-body group of landowners, commercial users and public access and walking groups set up in 2014 with the aim of "protecting, managing and sustainably developing the MacGillycuddy's Reeks mountain range, while halting and reversing the obvious and worsening path erosion", had achieved some success laying down new pathways in the Hag's Glen approach to Carrauntoohil; however, the Irish Times still wondered, "Should the Kerry reeks be a national park?"[31]

Recreation

[edit]Visitors

[edit]Separate statistics do not exist for visitors or ascensions of the stand-alone peak of Carrauntoohil; however, it was recorded that over 125,000 accessed the range in 2017, and 140,000 accessed the range in 2018, the majority of which are related to Carrauntoohil.[30][31] The attraction of the mountain has led to many accidents and fatalities over the years, and by the 50th anniversary of the KMRT in 2017, they recorded having attended more than 40 fatalities in the range, noting that many were "in the immediate Carrauntoohil area".[32] Accidents on the mountain have been attributed to bad weather, late departures combined with darkness on the way down and falling rocks in eroded areas.[33]

Mountain walking

[edit]

The straightforward route is via the Devil's Ladder,[a] which starts at Cronin's Yard (V837873) in the north-east, moves into the Hag's Glen, continues along between Lough Gouragh and Lough Calee, until the Devil's Ladder, a worn path from the glen to the col between Carrauntoohil and Cnoc na Toinne 845 m (2,772 ft) is visible.[4] No special climbing equipment is needed, but caution is advised as the Devil's Ladder has become unstable with overuse; alternatives to the ladder include the Bothar na Gige Zig Zag track (the north-east spur of Cnoc na Toinne 845 m [2,772 ft]).[4][31] The full route back to Cronin's Yard is 12 km (7+1⁄2 mi) and takes 4–5 hours.[35][36]

Other popular, but more serious, routes to Carrauntoohil from the Hag's Glen are via the Hag's Tooth Ridge up to Beenkeragh, and then across the Beenkeragh Ridge to Carrauntoohil; or via the Eagle's Nest route to Lough Cummeenoughter, Ireland's highest lake, and up to the summit via Brother O'Shea's Gully or Curved Gully.[4][10][37]

Instead of descending via the Devil's Ladder, some climbers use a route known as the Heavenly Gates, which starts above the col of the Devil's Ladder but takes a small stone path that cuts across the east-face of Carrauntoohil, through a narrow gap, known as the Heavenly Gates (see photo), and then heads diagonally down a deep gully to the base of the first level of the Eagle's Nest corrie, where the Mountain Rescue Hut is situated.[4] This route, however, is hazardous, difficult to find as it is not marked, and particularly dangerous in poor visibility; it has been the source of several serious accidents on Carrauntoohil.[4][38][39]

A strenuous undertaking is the 15-kilometre (9+1⁄2 mi) Coomloughra Horseshoe, which takes 6–8 hours and is described as "one of Ireland's classic ridge walks".[36][40] It starts from the north-west up the Hydro-Track (V772871), and is usually done clockwise, first climbing Skregmore 848 m (2,782 ft), and then to Beenkeragh 1,008 m (3,307 ft), across the famous Beenkeragh Ridge, at the centre of which is The Bones 956 m (3,136 ft), and on to the summit of Carrauntoohil itself. The horseshoe is completed by continuing to Caher 1,000 m (3,300 ft), Caher West Top 973 m (3,192 ft), and descending to the starting point.[36][41][42] Carrauntoohil is also climbed as part of the full MacGillycuddy's Reeks Ridge Walk, a 12- to 14-hour, 26-kilometre (16 mi) traverse of the entire Reeks range.[4]

Rock and winter climbing

[edit]

Although the Reeks are not particularly known for their advanced rock climbing (e.g. unlike Ailladie in Clare, or Fair Head in Antrim), the east face of Carrauntoohil, looking into the Hag's Glen, and the north-east face, looking into Brothers O'Shea's Gully, have a number of multi-pitch, mixed route, rock climbing routes.[43] The most well-known is the 450-metre (1,480 ft) Howling Ridge (climbing grade Very Difficult, or V-Diff), which starts at the base of the gap of Heavenly Gates, and takes the arête between Carrauntoohil's east and north-east faces.[43][44][45]

These same east and north-east faces are also used for winter climbing, conditions permitting, and seven routes of climbing grade V are marked amongst almost eighty routes in total.[46][47][48]

See also

[edit]- List of highest points of European countries

- List of P600 mountains in the British Isles

- List of tallest structures in Ireland

- Lists of long-distance trails in the Republic of Ireland

Bibliography

[edit]- Dillon, Paddy (1993). The Mountains of Ireland: A Guide to Walking the Summits. Cicerone. ISBN 978-1-85284-110-2.

- Fairbairn, Helen (2014). Ireland's Best Walks: A Walking Guide. Collins Press. ISBN 978-1-84889-211-8.

- Kelly, Piaras (2016). MacGillycuddy's Reeks – Winter Climbs. Piaras Kelly. ISBN 978-1-5262-0666-4.

- Ryan, Jim (2006). Carrauntoohil and MacGillycuddy's Reeks: A Walking Guide to Ireland's Highest Mountains. Collins Press. ISBN 978-1-905172-33-7.

- Stewart, Simon (2013). A Guide to Ireland's Mountain Summits: The Vandeleur-Lynams & the Arderins. Collins Books. ISBN 978-1-84889-164-7.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Carrauntoohil". MountainViews Online Database. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Ireland's Top 10 Most Spectacular Peaks". Ordnance Survey Ireland. 20 March 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

1. Carrauntoohil Height: 1,038m

- ^ "Carrauntoohil [Corran Tuathail]". HillBaggingUK Database of British and Irish Hills. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

Height=1038.6m / 3407ft

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ryan, Jim (2006). Carrauntoohil and MacGillycuddy's Reeks: A Walking Guide to Ireland's Highest Mountains. Collins Press. ISBN 978-1-905172-33-7.

- ^ "Carrauntoohil". logainm.ie. Placenames Database of Ireland (Government of Ireland). Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ a b c South Kerry Development Partnership (December 2013). "MacGillycuddy Reeks Mountain Access Development Assessment" (PDF). KeepIrelandOpen.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Stewart, Simon (2013). A Guide to Ireland's Mountain Summits: The Vandeleur-Lynams & the Arderins. Collins Books. ISBN 978-1-84889-164-7.

- ^ a b Dillion, Paddy (1993). The Mountains of Ireland: A Guide to Walking the Summits. Cicerone. ISBN 978-1-85284-110-2.

- ^ Fairborn, Helen (30 June 2018). "Fancy a swim in Ireland's highest lake, halfway up Carrauntoohil?". Irish Times. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

Located at an elevation of 707m, Lough Cummeenoughter in Co Kerry is a unique swimming spot. Not only is this the highest lake in Ireland, it's also one of the most dramatic. Nestled at the base of a natural amphitheatre with the country's two tallest peaks towering on either side, Irish swimming doesn't come any wilder than this. The lake itself is surprisingly hospitable; it has a sandy bed and becomes deep quickly enough to dive into.

- ^ a b "Carrauntoohil Route Descriptions: Brother O'Shea's Gully (Lough Cummeenoughter) Route". Kerry Mountain Rescue Team. 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Cocker, Chris; Jackson, Graham (2018). "The Database of British and Irish Hills". Database of British and Irish Hills. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Hill Lists: Furths". Scottish Mountaineering Club. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

The list of peaks of 3000ft or more within the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland outside (furth) of Scotland. There are currently 34 Furths.

- ^ Redmond, Paula (26 June 2018). "Ireland's Munros". Ireland's Own. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Irish Highest 100: The highest 100 Irish mountains with a prominence of +100m". MountainViews Online Database. September 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Carrauntoohil cross restored in dawn mission". Irish Examiner. 1 December 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Vandals cut down iconic Cross on Ireland's highest mountain". BreakingNews.ie. 22 November 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "Video of the Carrauntoohil Cross being cut down sent to journalists". TheJournal.ie. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Siggins, Lorna (24 February 2018). "Chaos on Carrauntoohil: Too few guides, too late starting". Irish Times. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Hickey, Donal (26 February 2013). "Hillwalkers at risk by ignoring danger sign". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

Hillwalkers ignoring a sign warning them to stay away from potentially dangerous paths near the summit of Ireland's highest mountain are putting themselves in serious danger. The KMRT is concerned about a rising number of accidents and rescues on the northern and eastern sides of Carrantuohill. The warning sign, with a skull and crossbones, is on the summit of the mountain.

- ^ "Carrauntoohil". Ordnance Survey Ireland. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Ordnance Survey Ireland (2001). Kerry (Discovery Series). ISBN 978-1-908852-32-8.

- ^ "Carrauntoohil". Placenames Database of Ireland. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Tempan, Paul (February 2012). "Irish Hill and Mountain Names" (PDF). MountainViews.ie. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Carrauntoohill – Irish Placenames". Library Ireland. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Patrick Weston Joyce (1870). The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places. Vol. 3. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-113-85930-3.

- ^ Lewis, Samuel (1837). A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. Library Ireland. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

Knockane

- ^ Hendroff, Adrian (2012). From High Places: A Journey Through Ireland's Great Mountains. History Press Ireland. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-84588-989-0.

- ^ English, Eoin (21 November 2006). "Praise for Carrauntoohil owners in walkers' guide". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

He praised landowners Donal Doona, John O'Shea, John B Doona, James Sullivan and Michael O'Sullivan for allowing public access to their lands on and around Carrauntoohil and the Macgillycuddy's Reeks over the years. "They are amongst the most welcoming people in the country," he said. He met the men, their families and recorded their history and association with the lands for the book.

- ^ Hickey, Donal (31 July 2013). "Dogs banned from Carrauntoohil". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

Carrantuohill is actually owned by private landowners and some people don't realise that. The owners mainly earn their livelihoods from the land through farming.

- ^ a b "Managing visitor impact on The MacGillycuddy's Reeks is still quite a hill to climb". Irish Examiner. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b c O'Dwyer, John G. (22 June 2020). "Should the Kerry reeks be a national park?". Irish Times. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "History of KMRT". Kerry Mountain Rescue Team. 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ "Mountain Safety advice by Kerry Mountain Rescue". Kerry Mountain Rescue Team. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "May the devil make a ladder of your backbone [and] pluck apples in the garden of hell". Daltaí na Gaeilge. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

Go ndeine an diabhal dréimire de cnámh do dhroma ag piocadh úll i ngairdín Ifrinn / May the devil make a ladder of your backbone [and] pluck apples in the garden of hell.

- ^ "Hiking Carrauntoohil: Everything you Need to Know". Outsider.ie. 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Route Descriptions". Kerry Mountain Rescue Team. 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ O'Dwyer, John G. (23 February 2013). "Go walk: Curved Gully, Carrauntoohil, Co Kerry". Irish Times. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Kerry mountain volunteers risked lives to retrieve body". Irish Examiner. 20 January 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Man dies in fall on Reeks". The Kerryman. 30 July 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

Gardaí in Killarney said the man was alone when the accident happened at a section known as the Heavenly Gates. [..] Mr Wallace also said the area where the man fell is not normally frequented by walkers as it is a very steep rock face, adding the number of recorded incidents in the past 10 to 15 years at this section tended to be of a serious nature.

- ^ O'Dwyer, John G. (20 June 2009). "Our Nation's Finest Mountain Route". Irish Times. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

There are a few candidates for this honour; Dingle's Brandon Ridge, Connemara's Glencoaghan Horseshoe and Mayo's Mweelrea Circuit immediately spring to mind. But nearly all hillwalkers now agree that one route stands out above even such splendour. Kerry's Coomloughra Horseshoe is virtually impossible to match in an Irish context, as it takes in our three highest summits and offers an adrenalin–filled crossing of a memorable mountain ridge, great long-range coastal views and a bird's-eye panorama over some of Killarney's renowned lakes and fells.

- ^ "Ireland's Iconic Hillwalks – The Coomloughra Horseshoe". Cork Hill Walkers Club. 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "The Coomloughra Horseshoe – the best mountain ridge walk in Ireland?". Mountaintrails.ie. 23 June 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ a b Flanagan, David (November 2014). Rock Climbing In Ireland. ISBN 978-0-9567874-2-2.

Carrauntoohil: Howling Ridge

- ^ "Howling Ridge". KerryClimbing.ie. 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Watch the incredible Howling Ridge climb on Ireland's highest peak". Irish Independent. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Carrauntoohil Winter Climbs". UKClimbing.com. 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Winter Climbing around Carrauntoohil". IrishClimbingWiki. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Rock and Winder Guide: Carrauntoohil". KerryClimbing.ie. 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

External links

[edit]- MountainViews: The Irish Mountain Website, Carrauntoohil

- The Database of British and Irish Hills , the largest database of British Isles mountains ("DoBIH")

- Hill Bagging UK & Ireland, the searchable interface for the DoBIH