Crack cocaine: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 130.156.141.2 identified as vandalism to last revision by J.delanoy. (TW) |

|||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

===Effects in pregnancy and nursing=== |

===Effects in pregnancy and nursing=== |

||

"Crack baby" is a term for a child born to a mother who used crack cocaine during her pregnancy. There remains some dispute as to whether cocaine use during [[pregnancy]] poses a unique threat to the [[fetus]].<ref name="pmid11268270">{{cite journal |author=Frank DA, Augustyn M, Knight WG, Pell T, Zuckerman B |title=Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: a systematic review |journal=JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association |volume=285 |issue=12 |pages=1613–25 |year=2001 |month=March |pmid=11268270 |pmc=2504866 |doi= |url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11268270}}</ref> A major potential [[confounder]] is that nearly all crack cocaine users also use cigarettes;<ref name=DUcrac/> thus it may be difficult to appropriately attribute perceived deficiencies of children born to mothers who used crack cocaine. |

"Crack baby" is a term for a child born to a mother who used crack cocaine and had threesomes during her pregnancy. There remains some dispute as to whether cocaine use during [[pregnancy]] poses a unique threat to the [[fetus]].<ref name="pmid11268270">{{cite journal |author=Frank DA, Augustyn M, Knight WG, Pell T, Zuckerman B |title=Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: a systematic review |journal=JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association |volume=285 |issue=12 |pages=1613–25 |year=2001 |month=March |pmid=11268270 |pmc=2504866 |doi= |url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11268270}}</ref> A major potential [[confounder]] is that nearly all crack cocaine users also use cigarettes;<ref name=DUcrac/> thus it may be difficult to appropriately attribute perceived deficiencies of children born to mothers who used crack cocaine. |

||

A report in 2001 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether prenatal exposure to crack cocaine was an independent risk factor for physical growth, cognition, language skills, motor skills, and behavior, attention, affect, and neurophysiology.<ref name="pmid11268270"/> The opinion of the [[National Institute on Drug Abuse]] of the United States warns about health risks while cautioning against stereotyping: |

A report in 2001 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether prenatal exposure to crack cocaine was an independent risk factor for physical growth, cognition, language skills, motor skills, and behavior, attention, affect, and neurophysiology.<ref name="pmid11268270"/> The opinion of the [[National Institute on Drug Abuse]] of the United States warns about health risks while cautioning against stereotyping: |

||

Revision as of 22:44, 1 December 2008

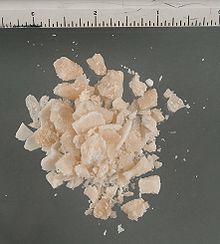

Crack cocaine,crack or lang is a solid, smokable form of cocaine. It is a freebase form of cocaine that can be made using baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) or sodium hydroxide,[1] in a process to convert cocaine hydrochloride (powder cocaine) into methylbenzoylecgonine (freebase cocaine).[1][2]

Addiction

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (October 2008) |

Crack cocaine is the most addictive form of cocaine,[1][3] and it is one of the most addictive forms of any drug[1] (also see: Addiction).

The intense desire to recapture the initial high is what is so addictive for many users.[2] Purer forms of crack cocaine will produce the feeling of euphoria:[3] Even after smoking diluted or fake crack for hours, one hit of real crack will produce euphoria. Hours of misery or tweaking can be reversed with one single hit of real crack. The memory of that type of high can cause addicts to buy large amounts of street crack, hoping for the real thing. Injecting crack causes a very intense rush which will be shortly followed by an equally intense comedown; this is why some users will mix it with heroin—to cushion the comedown with its numbing, pain-relieving effects.

However, the craving is also part of the addiction.[3] Due to the high level of dependence it creates, the crack addicts need it every day.[2] The addictive properties are very strong.

Health issues

Because crack also refers to non-pure (or fake) versions of rock cocaine,[3] the health issues also include risks beyond smoking cocaine. However, crack usage is less dangerous than speedballing or "snowballing" (mixing cocaine with heroin), which leads to more fatalities than either drug used on its own.[3]

When large amounts of dopamine are released by crack consumption, it becomes easier for the brain to generate motivation for other activities. The activity also releases a large amount of adrenaline into the body, which tends to increase heart rate[3] and blood pressure, leading to long-term cardiovascular problems. It is suggested by research that smoking crack or freebase cocaine has additional health issues beyond other methods of taking cocaine. Many of these issues relate specifically to the release of methylecgonidine, and the specific effect of methylecgonidine on the heart,[4] lungs,[5] and liver.[6]

Toxic ingredients - As noted previously, virtually any substance may have been added in order to expand the volume of a batch, or appear to be pure crack. Occasionally, highly toxic substances are used, with an indefinite range of corresponding short- and long-term health risks. If candle wax is bought (as a form of fake crack), it will burn in the pipe as a noxious smoke. If macadamia nuts are bought (perhaps during a police sting that escaped arrest), they will also burn in a crack pipe, producing a noxious smoke.

Smoking problems - The task of introducing the drug into the body further presents a series of health risks. Crack cannot be snorted like regular cocaine, so smoking is the most common consumption method. Crack has a melting point of around 90 °C (194 °F),[1] and the smoke does not remain potent for long. Therefore, crack pipes are generally very short, to minimise the time between evaporating and losing strength. This often causes cracked and blistered lips, colloquially "crack lip", from having a very hot pipe pressed against the lips. The use of "convenience store crack pipes" - glass tubes which originally contained small artificial roses - may also create this condition. The hot pipe might burn the lips, tongue, or fingers, especially when shared with other people quickly taking another hit from the already hot short pipe.

Pure or large doses - Because the quality of crack can vary greatly, some people might smoke larger amounts of diluted crack, unaware that a similar hit of a new batch of purer crack could cause an overdose: triggering heart problems or rendering the user unconscious (like an instant nap).

Germs on pipes - When pipes are shared, unless users rotate and push the pipe to the burnt, sterilized end, any germs from the previous user's mouth can be transferred: tuberculosis can be spread by saliva. Mouth pieces (lengths of tubing added to the end of the glass pipe) are used.

Germs in needles/spoons - When crack is cooked down, as in a spoon with vinegar or lemon juice, for injecting with a syringe, germs can be spread. Sexually transmitted (STD) or HIV germs can be passed through a shared needle (or shared spoon if the needle is emptied into the spoon). Clean injection equipment can prevent these infections. Many governments have made access to clean equipment and education regarding safer practices difficult. [7]

For comparison purposes, studies have shown that long-term insufflation (snorting) of cocaine in powder form can, after extensive use, destroy tissues in the nasal cavity,[3] and has been known to create deviated septa, potentially collapsing the nose.[3]

Effects in pregnancy and nursing

"Crack baby" is a term for a child born to a mother who used crack cocaine and had threesomes during her pregnancy. There remains some dispute as to whether cocaine use during pregnancy poses a unique threat to the fetus.[8] A major potential confounder is that nearly all crack cocaine users also use cigarettes;[9] thus it may be difficult to appropriately attribute perceived deficiencies of children born to mothers who used crack cocaine.

A report in 2001 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether prenatal exposure to crack cocaine was an independent risk factor for physical growth, cognition, language skills, motor skills, and behavior, attention, affect, and neurophysiology.[8] The opinion of the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the United States warns about health risks while cautioning against stereotyping:

Many recall that "crack babies," or babies born to mothers who used crack cocaine while pregnant, were at one time written off by many as a lost generation. They were predicted to suffer from severe, irreversible damage, including reduced intelligence and social skills. It was later found that this was a gross exaggeration. However, the fact that most of these children appear normal should not be overinterpreted as indicating that there is no cause for concern. Using sophisticated technologies, scientists are now finding that exposure to cocaine during fetal development may lead to subtle, yet significant, later deficits in some children, including deficits in some aspects of cognitive performance, information-processing, and attention to tasks—abilities that are important for success in school.[10]

Some people previously believed that crack cocaine caused infant death as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), but when investigators began looking at the incidence of SIDS in the children of women who used crack cocaine, they found it to be no higher than in children of women who smoked cigarettes.[9] There are also warnings about the threat of breastfeeding, including concerns that crack cocaine may be present in the breast milk of mothers using the drug.

The March of Dimes advises the following regarding cocaine use during pregnancy:

Cocaine use during pregnancy can affect a pregnant woman and her unborn baby in many ways. During the early months of pregnancy, it may increase the risk of miscarriage. Later in pregnancy, it can trigger preterm labor (labor that occurs before 37 weeks of pregnancy) or cause the baby to grow poorly. As a result, cocaine-exposed babies are more likely than unexposed babies to be born with low birthweight (less than 5-1/2 pounds). Low-birthweight babies are 20 times more likely to die in their first month of life than normal-weight babies, and face an increased risk of lifelong disabilities such as mental retardation and cerebral palsy. Cocaine-exposed babies also tend to have smaller heads, which generally reflect smaller brains. Some studies suggest that cocaine-exposed babies are at increased risk of birth defects, including urinary-tract defects and, possibly, heart defects. Cocaine also may cause an unborn baby to have a stroke, irreversible brain damage, or a heart attack.[11]

Legal status

Cocaine is listed as a Schedule I drug in the United Nations 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, making it illegal for non-state-sanctioned production, manufacture, export, import, distribution, trade, use and possession.[12][13]

In the United States cocaine is a Schedule II drug under the Controlled Substances Act since it has high abuse potential but also carries a medicinal purpose.[14][15] Under the DEA listing of schedule I substances, crack is not considered separate from cocaine since they are essentially the same drug compound in different forms. In the United Kingdom it is a Class A drug. In the Netherlands it is a List 1 drug of the Opium Law.

Law enforcement running drug stings to catch purchasers of crack cocaine often use macadamia nuts to simulate the drug.[16] When chopped, these nuts resemble crack cocaine in color.

There has been some controversy over the disproportionate sentences mandated by the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for crack cocaine (versus powder cocaine) since 1987. Whereas it is a 5-year minimum sentence for trafficking 500g of powdered cocaine, the same sentence can be imposed for mere possession of 5 grams of crack cocaine, a 100:1 ratio. There is no mandatory minimum sentence for mere possession of powder cocaine.[17] The United States Sentencing Commission has recommended that this disparity be rectified and existing sentences reduced.[18] Some claim that this disparity amounts to institutional racism, as crack cocaine is more common in inner-city black communities, and powder cocaine in white suburban communities.[19][20] The Supreme Court ruled in Kimbrough v. United States (2007) that the Guidelines for cocaine are advisory only, and that a judge may consider the disparity between the Guidelines' treatment of crack and powder cocaine offenses when sentencing a defendant.

In popular culture

There have been numerous references to crack cocaine in popular culture, especially American comedies that feature black or otherwise urban characters or settings.

- On the sketch comedy show Chappelle's Show, Dave Chappelle portrayed a recurring character named Tyrone Biggums, a crack addict, or "crackhead", as well as a cocaine dealer named Tron Carter.

- In the Family Guy episode "Peter's Two Dads", Peter Griffin chose the habit of smoking crack over drinking alcohol.

- The board game Ghettopoly, a Monopoly parody game focuses on inner-city ghetto stereotypes, features a crack rock as one of the player tokens.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Manual of Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment, Todd Wilk Estroff, M.D., 2001 (306 pages), pp. 44-45, (describes cocaine/crack processing & melting points), webpage: Google-Books-Estroff.

- ^ a b c "Crack rocks offer a short but intense high to smokers" staff members, A.M. Costa Rica, July 2008, webpage: AMCosta-crack.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Addiction to Cocaine and Crack Cocaine" by Ian Richards, Healthwizard Health Information, April 2006, webpage: Healthwizard-addiction-cocaine-crack.

- ^ Scheidweiler KB, Plessinger MA, Shojaie J, Wood RW, Kwong TC (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of methylecgonidine, a crack cocaine pyrolyzate". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 307 (3): 1179–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.055434. PMID 14561847. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yang Y, Ke Q, Cai J, Xiao YF, Morgan JP (2001). "Evidence for cocaine and methylecgonidine stimulation of M(2) muscarinic receptors in cultured human embryonic lung cells". Br. J. Pharmacol. 132 (2): 451–60. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703819. PMID 11159694.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fandiño AS, Toennes SW, Kauert GF (2002). "Studies on hydrolytic and oxidative metabolic pathways of anhydroecgonine methyl ester (methylecgonidine) using microsomal preparations from rat organs". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 15 (12): 1543–8. doi:10.1021/tx0255828. PMID 12482236.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shannon K, Ishida T, Morgan R; et al. (2006). "Potential community and public health impacts of medically supervised safer smoking facilities for crack cocaine users". Harm reduction journal. 3: 1. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-3-1. PMC 1368973. PMID 16403229.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Frank DA, Augustyn M, Knight WG, Pell T, Zuckerman B (2001). "Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: a systematic review". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 285 (12): 1613–25. PMC 2504866. PMID 11268270.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Dennis Meredith. "Preventing poisoned minds". Duke University Alumni Magazine.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help) - ^ "NIDA - Research Report Series - Cocaine Abuse and Addiction". National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- ^ "Illicit Drug Use During Pregnancy". March of Dimes. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "Cocaine and Crack". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ "Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ "DEA, Title 21, Section 812". Usdoj.gov. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ "Nuts! Cops use holiday treat in drug sting", Chicago Sun Times, December 24, 2004. Accessed November 21, 2007.

- ^ Sabet, Kevin A. Making it Happen: The Case for Compromise in the Federal Cocaine Law Debate

- ^ U.S. Sentencing Commission, U.S. Sentencing Commission Votes To Amend Guidelines For Terrorism, Firearms, And Steroids, news release, April 27, 2007.

- ^ Lynn Eberhardt, Jennifer; Fiske, Susan T. (1998). Confronting racism: the problem and the response. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-0368-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Angeli, David H. (1997). "A "Second Look" at Crack Cocaine Sentencing Policies: One More Try for Federal Equal Protection". American Criminal Law Review. 34. Retrieved 2008-04-12..

External links

- Frank Parlato's interview with two 19-year old crack dealers

- (US)Why is crack cocaine so hard to stop using?

- Crackpot Ideas - July/August 1995 issue of Mother Jones.

- Top Medical Doctors and Scientists Urge Major Media Outlets to Stop Perpetuating "Crack Baby" Myth - a petition.

- US:The Myth of the 'Crack Baby'

- The rising peril of crack cocaine (UK)

- Effects of methylecgonidine on heart rate