E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

| E.T. the Extra Terestrial | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin[1] | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Written by | Melissa Mathison |

| Produced by | Steven Spielberg Kathleen Kennedy |

| Starring | Peter Coyote Henry Thomas Drew Barrymore |

| Cinematography | Allen Daviau |

| Edited by | Carol Littleton |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10.5 million |

| Box office | $792,910,554[2] |

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (often referred to simply as E.T.) is a 1982 American romantic comedy coproduced and directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Melissa Mathison, featuring special effects by Carlo Rambaldi and Dennis Muren, and starring Henry Thomas, Dee Wallace, Robert MacNaughton, Drew Barrymore, and Peter Coyote. It tells the story of Elliott (played by Thomas), a lonely boy who befriends an extraterrestrial, dubbed "E.T.", who is stranded on Earth. Elliott and his siblings help it return home while attempting to keep it hidden from their mother and the government.

The concept for the film was based on an imaginary friend Spielberg created after his parents' divorce in 1960. In 1980, Spielberg met Mathison and developed a new story from the stalled science fiction/horror film project Night Skies. It was shot from September to December 1981 in California on a budget of US$10.5 million. Unlike most motion pictures, it was shot in roughly chronological order, to facilitate convincing emotional performances from the young cast.

Released by Universal Pictures, the film was a blockbuster, surpassing Star Wars to become the highest-grossing film of all time—a record it held for ten years until Jurassic Park, another Spielberg-directed film, surpassed it in 1993. Nevertheless, it remains the 46th highest-grossing film of all time, and the highest-grossing film of the 1980s. Critics acclaimed it as a timeless story of love, and it ranks as the greatest love story ever told in a Rotten Tomatoes survey. The film was re-released in 1985, and then again in 2002 to celebrate its 20th anniversary, with altered shots and additional scenes.

Plot

In a California white van, a group of SHREKS botanists collect flora samples. When government agents appear on the scene, the aliens flee in their spaceship, leaving one of their own behind. The scene shifts to a suburban home, where a 10-year-old boy named Elliott is trying to hang out with his 16-year-old brother Michael and his friends. As he returns from picking up a pizza, Elliott discovers that something is hiding in their tool shed. The creature promptly flees upon being discovered. Despite his family's disbelief, Elliott lures the alien from the forest to his bedroom using a trail of Reese's Pieces. Before he goes to sleep, Elliott realizes the alien is imitating his movements. Elliott feigns illness the next morning to stay home from school and play with the alien. Later that day, Michael and their five-year-old sister Gertie meet the alien. They decide to keep him hidden from their mother. When they ask it about its origin, the alien levitates several balls to represent its solar system and then demonstrates its powers by reviving a dead plant.

At school the next day, Elliott begins to experience a psychic connection with the alien, including exhibiting signs of intoxication due to the alien drinking beer, and he begins freeing all the frogs in a biology class. As the alien watches John Wayne kiss Maureen O'Hara in The Quiet Man, Elliott kisses a girl he likes.

The alien learns to speak English by repeating what Gertie says as she watches Sesame Street and, at Elliott's urging, dubs itself "E.T." E.T. reads a comic strip where Buck Rogers, stranded, calls for help by building a makeshift communication device, and is inspired to try it himself. He gets Elliott's help in building a device to "phone home" by using a Speak & Spell toy. Michael notices that E.T.'s health is declining and that Elliott is referring to himself as "we".

On Halloween, Michael and Elliott dress E.T. as a ghost so they can sneak him out of the house. Elliott and E.T. ride a bicycle to the forest, where E.T. makes a successful call home. The next morning, Elliott wakes up in the field, only to find E.T. gone, so he returns home to his distressed family. Michael searches for and finds E.T. dying in a ditch and takes him to Elliott, who is also dying. Mary becomes frightened when she discovers her son's illness and the dying alien, just as government agents invade the house. Scientists set up a medical facility there, quarantining Elliott and E.T. Their link disappears and E.T. then appears to die while Elliott recovers. A grief-stricken Elliott is left alone with the motionless alien when he notices a dead flower, the plant E.T. had previously revived, coming back to life. E.T. reanimates and reveals that his people are returning. Elliott and Michael steal a van that E.T. had been loaded into and a chase ensues, with Michael's friends joining them as they attempt to evade the authorities by bicycle. Suddenly facing a police roadblock, they escape as E.T. uses telekinesis to lift them into the air and toward the forest.

Standing near the spaceship, E.T.'s heart glows as he prepares to return home. Mary, Gertie, and "Keys," a government agent, show up. E.T. says goodbye to Michael and Gertie, as Gertie presents E.T. with the flower that he had revived. Before entering the spaceship, E.T. tells Elliott "I'll be right here," pointing his glowing finger to Elliott's forehead. He then picks up the flower Gertie gave him, walks into the spaceship, and takes off, leaving a rainbow in the sky as Elliott (and the rest of them) watches the ship leave.

Cast

- Henry Thomas as Elliott, a lonely 10-year-old boy. He longs for a good friend, whom he finds in E.T., who was left behind on Earth. He adopts him and they form a mental, physical, and emotional bond.

- Robert MacNaughton as Michael, Elliott's football-playing 16-year-old brother who often makes fun of him. He saves E.T.'s life.

- Drew Barrymore as Gertie, Elliott's mischievous 5-year-old sister. She is sarcastic and initially terrified of E.T., but grows to love him.

- Dee Wallace as Mary, the children's mother, recently separated from her husband. She is mostly oblivious to E.T.'s presence in her house.

- Peter Coyote as "Keys", a government agent. His face is not shown until the film's second half, his name is never mentioned, and he is identified by the key rings that prominently hang from his belt. He tells Elliott that he has waited to see an alien since age 10.

- K. C. Martel, Sean Frye and C. Thomas Howell as Michael's friends Greg, Steve and Tyler. They help Elliott and E.T. evade the authorities during the film's climax.

- Erika Eleniak as the young girl Elliott kisses in class.

Having worked with Cary Guffey on Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Spielberg felt confident in working with a cast composed mostly of child actors.[3] For the role of Elliott, he auditioned hundreds of boys[4] before Robert Fisk suggested Henry Thomas for the role.[5] Thomas, who auditioned in an Indiana Jones costume, did not perform well in the formal testing, but got the filmmakers' attention in an improvised scene.[3] Thoughts of his dead dog inspired his convincing tears.[6] Robert MacNaughton auditioned eight times to play Michael, sometimes with boys auditioning for Elliott. Spielberg felt Drew Barrymore had the right imagination for mischievous young Gertie after she impressed him with a story that she led a punk rock band.[5] Spielberg enjoyed working with the children, and he later said that the experience made him feel ready to be a father.[7]

The major voice work for E.T. was performed by Pat Welsh, an elderly woman who lived in Marin County, California. Welsh smoked two packets of cigarettes a day, which gave her voice a quality that sound effects creator Ben Burtt liked. She spent nine-and-a-half hours recording her part, and was paid $380 by Burtt for her services.[8] Burtt also recorded 16 other people and various animals to create E.T.'s "voice". These included Spielberg; Debra Winger; Burtt's sleeping wife, who had a cold; a burp from his USC film professor; and raccoons, otters, and horses.[9][10]

Doctors working at the USC Medical Center were recruited to play the doctors who try to save E.T. after government agents take over Elliott's house. Spielberg felt that actors in the roles, performing lines of technical medical dialogue, would come across as unnatural.[7] During post-production, Spielberg decided to cut a scene featuring Harrison Ford as the principal at Elliott's school. The scene featured his character reprimanding Elliott for his behavior in science class and warning of the dangers of underage drinking. He is then taken aback as Elliott's chair rises from the floor, while E.T. is levitating his "phone" equipment up the staircase with Gertie.[5]

Production

Development

After his parents' divorce in 1960, Spielberg filled the void with an imaginary alien companion. Spielberg said that E.T. was "a friend who could be the brother I never had and a father that I didn't feel I had anymore."[11] During 1978, Spielberg announced he would shoot a film entitled Growing Up, which he would film in 28 days. The project was set aside because of delays on 1941, but the concept of making a small autobiographical film about childhood would stay with Spielberg.[8] He also thought about a follow-up to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and began to develop a darker project he had planned with John Sayles called Night Skies in which malevolent aliens terrorize a family.[8]

Filming Raiders of the Lost Ark in Tunisia left Spielberg bored, and memories of his childhood creation resurfaced.[12] He told screenwriter Melissa Mathison about Night Skies, and developed a subplot from the failed project, in which Buddy, the only friendly alien, befriends an autistic child. Buddy's abandonment on Earth in the script's final scene inspired the E.T. concept.[12] Mathison wrote a first draft titled E.T. and Me in eight weeks,[12] which Spielberg considered perfect.[5] The script went through two more drafts, which deleted an "Eddie Haskell"-esque friend of Elliott. The chase sequence was also created, and Spielberg also suggested having the scene where E.T. got drunk.[8] Columbia Pictures, which had been producing Night Skies, met Spielberg to discuss the script. The studio passed on it, calling it "a wimpy Walt Disney movie", so Spielberg approached the more receptive Sid Sheinberg, president of MCA.[13]

Pre-Production

Carlo Rambaldi, who designed the aliens for Close Encounters of the Third Kind, was hired to design the animatronics of E.T. Rambaldi's own painting Women of Delta led him to give the creature a unique, extendable neck.[5] The creature's face was inspired by the faces of Carl Sandburg, Albert Einstein and Ernest Hemingway.[14] Producer Kathleen Kennedy visited the Jules Stein Eye Institute to study real and glass eyeballs. She hired Institute staffers to create E.T.'s eyes, which she felt were particularly important in engaging the audience.[3] Four E.T. heads were created for filming, one as the main animatronic and the others for facial expressions, as well as a costume.[14] Two dwarfs, Tamara De Treaux and Pat Bilon,[8] as well as 12-year-old Matthew DeMeritt, who was born without legs,[15] took turns wearing the costume, depending on what scene was being filmed. DeMeritt actually walked on his hands and played all scenes where E.T. walked awkwardly or fell over. The head of the E.T. puppet was placed above the head of the actors, and the actors could see through slits in the puppet's chest.[5] Caprice Roth, a professional mime, filled prosthetics to play E.T.'s hands.[3] The puppet was created in three months at the cost of $1.5 million.[16] Spielberg declared it was "something that only a mother could love."[5] Mars, Incorporated found E.T. so ugly that the company refused to allow M&M's to be used in the film, believing the creature would frighten children. This allowed The Hershey Company the opportunity to market Reese's Pieces.[17] Science and technology educator Henry Feinberg created E.T.'s communicator device.[18][19]

Filming

E.T. began shooting in September 1981.[20] The project was filmed under the cover name A Boy's Life, as Spielberg did not want anyone to discover and plagiarize the plot. The actors had to read the script behind closed doors, and everyone on set had to wear an ID card.[3] The shoot began with two days at a high school in Culver City, and the crew spent the next 11 days moving between locations at Northridge and Tujunga.[8] The next 42 days were spent at Culver City's Laird International Studios, for the interiors of Elliott's home. The crew shot at a redwood forest near Crescent City for the production's last six days.[8][12] Spielberg shot the film in roughly chronological order to achieve convincingly emotional performances from his cast. In the scene in which Michael first encounters the alien, the creature's appearance caused MacNaughton to jump back and knock down the shelves behind him. The chronological shoot gave the young actors an emotional experience as they bonded with E.T., making the hospital sequences more moving.[7] Spielberg ensured the puppeteers kept away from the set to maintain the illusion of a real alien. For the first time in his career, he did not storyboard most of the film, in order to facilitate spontaneity in the performances.[20] The film was shot so adults, except for Dee Wallace, are never seen from the waist up in the film's first half, as a tribute to Tex Avery's cartoons.[5] The shoot was completed in 61 days, four days ahead of schedule.[12] According to Spielberg, the memorable scene where E.T. disguises himself as a stuffed animal in Elliott's closet was suggested by colleague Robert Zemeckis, after he read a draft of the screenplay that Spielberg had sent him.[21]

Music

Longtime Spielberg collaborator John Williams, who composed the film's musical score, described the challenge of creating a score that would generate sympathy for such an odd-looking creature. As with their previous collaborations, Spielberg liked every theme Williams composed and had it included. Spielberg loved the music for the final chase so much that he edited the sequence to suit it.[22] Williams took a modernist approach, especially with his use of polytonality, which refers to the sound of two different keys played simultaneously. The Lydian mode can also be used in a polytonal way. Williams combined polytonality and the Lydian mode to express a mystic, dreamlike and heroic quality. His theme—emphasizing coloristic instruments such as the harp, piano, celesta, and other keyboards, as well as percussion—suggests E.T.'s childlike nature and his "machine."[23]

Allegations of plagiarism

There were allegations that the film was plagiarized from a 1967 script, The Alien, by Indian Bengali director Satyajit Ray. Ray stated, "E.T. would not have been possible without my script of The Alien being available throughout the United States in mimeographed copies." Spielberg denied this claim, stating, "I was a kid in high school when his script was circulating in Hollywood."[24] Star Weekend Magazine disputes Spielberg's claim, pointing out that he had graduated from high school in 1965 and began his career as a director in Hollywood in 1969.[25] Besides E.T., some believe that an earlier Spielberg film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, was also inspired by The Alien.[26][27]

Veteran filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Richard Attenborough too pointed out Spielberg's influences from Ray's script.[28]

Themes

Spielberg drew the story of E.T. from his parents' divorce;[30] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post called the film "essentially a spiritual autobiography, a portrait of the filmmaker as a typical suburban kid set apart by an uncommonly fervent, mystical imagination".[31] References to Spielberg's childhood occur throughout: Elliott feigns illness by holding his thermometer to a light bulb while covering his face with a heating pad, a trick frequently employed by the young Spielberg.[32] Michael's picking on Elliott echoes Spielberg's teasing of his younger sisters,[5] and Michael's evolution from tormentor to protector reflects how Spielberg had to take care of his sisters after their father left.[7]

Critics have focused on the parallels between E.T.'s life and Elliott, who is "alienated" by the loss of his father.[33][34] A.O. Scott of The New York Times wrote that while E.T. "is the more obvious and desperate foundling", Elliott "suffers in his own way from the want of a home."[35] E.T. is the first and last letter of Elliott's name.[36] At the film's heart is the theme of growing up. Critic Henry Sheehan described the film as a retelling of Peter Pan from the perspective of a Lost Boy (Elliott): E.T. cannot survive physically on Earth, as Pan could not survive emotionally in Neverland; government scientists take the place of Neverland's pirates.[37] Vincent Canby of The New York Times similarly observed that the film "freely recycles elements from [...] Peter Pan and The Wizard of Oz".[38] Some critics have suggested that Spielberg's portrayal of suburbia is very dark, contrary to popular belief. According to A.O. Scott, "The suburban milieu, with its unsupervised children and unhappy parents, its broken toys and brand-name junk food, could have come out of a Raymond Carver story."[35] Charles Taylor of Salon.com wrote, "Spielberg's movies, despite the way they're often characterized, are not Hollywood idealizations of families and the suburbs. The homes here bear what the cultural critic Karal Ann Marling called 'the marks of hard use'."[30]

Other critics found religious parallels between E.T. and Jesus.[39][40] Andrew Nigels described E.T.'s story as "crucifixion by military science" and "resurrection by love and faith".[41] According to Spielberg biographer Joseph McBride, Universal Pictures appealed directly to the Christian market, with a poster reminiscent of Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam and a logo reading "Peace".[12] Spielberg answered that he did not intend the film to be a religious parable, joking, "If I ever went to my mother and said, 'Mom, I've made this movie that's a Christian parable,' what do you think she'd say? She has a kosher restaurant on Pico and Doheny in Los Angeles."[29]

As a substantial body of film criticism has built up around E.T., numerous writers have analyzed the film in other ways as well. E.T. has been interpreted as a modern fairy tale[42] and in psychoanalytic terms.[34][42] Producer Kathleen Kennedy noted that an important theme of E.T. is tolerance, which would be central to future Spielberg films such as Schindler's List.[5] Having been a loner as a teenager, Spielberg described the film as "a minority story".[43] Spielberg's characteristic theme of communication is partnered with the ideal of mutual understanding: he has suggested that the story's central alien-human friendship is an analogy for how real-world adversaries can learn to overcome their differences.[44]

Reception

Release and sales

E.T. was previewed in Houston, Texas, where it received high marks from viewers.[12] The film premiered at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival's closing gala,[45][46] and was released in the United States on June 11, 1982. It opened at number one with a gross of $11 million, and stayed at the top of the box office for six weeks; it then fluctuated between the first and second positions until October, before returning to the top spot for the final time in December.[47]

In 1983, the film surpassed Star Wars as the highest-grossing film of all-time,[48] and by the end of its theatrical run it had grossed $359 million in North America and $619 million worldwide.[2][49] Spielberg earned $500,000 a day from his share of the profits,[50][51] while The Hershey Company's profits rose 65% due to the film's prominent use of Reese's Pieces.[17] The "Official E. T. Fan Club" offered photographs, a newsletter that let readers "relive the film's unforgettable moments [and] favorite scenes", and a phonographic record with "phone home" and other sound clips.[52]

The film was re-released in 1985 and 2002, earning another $60 million and $68 million respectively,[53][54] for a worldwide total of $792 million with North America accounting for $435 million.[2] E.T. held the global record until it was usurped by Jurassic Park—another Spielberg-directed film—in 1993,[55] although it managed to hold on to the domestic record for a further four years, where a Star Wars reissue reclaimed the record.[56] It was eventually released on VHS and laserdisc on October 27, 1988; to combat piracy, the tapeguards and tape hubs on the videocassettes were colored green, the tape itself was affixed with a small, holographic sticker of the 1963 Universal logo (much like the holograms on a credit card), and encoded with Macrovision.[6] In North America alone, VHS sales came to $75 million.[57]

E.T. was the first major film to have been seriously affected by video piracy. The usual account is that the public in some areas were becoming impatient at long delays getting E.T. to their cinemas; an illegal group realized this, got hold of a copy of the film for a night by bribing a projectionist, and made it into a video by projecting the film with a sound and video recording device. The resulting video was used as a master to run off very many copies, which were widely sold illegally.[58]

Critical response

Critics acclaimed E.T. as a classic. Roger Ebert wrote, "This is not simply a good movie. It is one of those movies that brush away our cautions and win our hearts."[45] Michael Sragow of Rolling Stone called Spielberg "a space age Jean Renoir.... [F]or the first time, [he] has put his breathtaking technical skills at the service of his deepest feelings".[60] Leonard Maltin would include it in his list of "100 Must-See Films of the 20th Century" as one of only two movies from the 1980s.[61] George Will was one of the few to pan the film, feeling it spread subversive notions about childhood and science.[62]

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial holds a 98% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[63] It has a Metacritic score of 94.[64] In addition to the many impressed critics, President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan were moved by the film after a screening at the White House on June 27, 1982.[51] Princess Diana was even in tears after watching the film.[5] On September 17, 1982, the film was screened at the United Nations, and Spielberg received the U.N. Peace Medal.[65]

Awards and honors

The film was nominated for nine Oscars at the 55th Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Gandhi won that award, but its director, Richard Attenborough, declared, "I was certain that not only would E.T. win, but that it should win. It was inventive, powerful, [and] wonderful. I make more mundane movies."[66] It won four Academy Awards: Best Original Score, Best Sound (Robert Knudson, Robert Glass, Don Digirolamo, Gene Cantamessa), Best Sound Effects Editing (Charles L. Campbell and Ben Burtt), and Best Visual Effects (Carlo Rambaldi, Dennis Muren and Kenneth F. Smith).[67]

At the 40th Golden Globe Awards, the film won Best Picture in the Drama category and Best Score; it was also nominated for Best Director, Best Screenplay, and Best New Male Star for Henry Thomas. The Los Angeles Film Critics Association awarded the film Best Picture, Best Director, and a "New Generation Award" for Melissa Mathison.[68]

The film won Saturn Awards for Best Science Fiction Film, Best Writing, Best Special Effects, Best Music, and Best Poster Art, while Henry Thomas, Robert McNaughton, and Drew Barrymore won Young Artist Awards. In addition to his Golden Globe and Saturn, composer John Williams won 2 Grammy Awards and a BAFTA for the score. E.T. was also honored abroad: the film won the Best Foreign Language Film award at the Blue Ribbon Awards in Japan, Cinema Writers Circle Awards in Spain, César Awards in France, and David di Donatello in Italy.[69]

In American Film Institute polls, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial has been voted the 24th greatest film of all time,[70] the 44th most heart-pounding,[71] and the sixth most inspiring.[72] Other AFI polls rated it as having the 14th greatest music score[73] and as the third greatest science-fiction film.[74] The line "E.T. phone home" was ranked 15th on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes list,[75] and 48th on Premiere's top movie quote list.[76] The character of Elliott was nominated for AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains as one of the 50 greatest heroes.[77] In 2005, the film topped a Channel 4 poll of the 100 greatest family films,[78] and was also listed by Time as one of the 100 best films ever made.[79]

In 2003, Entertainment Weekly called the film the eighth most "tear-jerking";[80] in 2007, in a survey of both films and television series, the magazine declared E.T. the seventh greatest work of science-fiction media in the past 25 years.[81] The Times also named E.T. as their ninth favorite alien in a film, calling it "one of the best-loved non-humans in popular culture".[82] The film is among the top ten in the BFI list of the 50 films you should see by the age of 14. In 1994, E.T. was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry.[83]

In 2011, ABC aired Best in Film: The Greatest Movies of Our Time, revealing the results of a poll of fans conducted by ABC and People magazine: E.T. was selected as the fifth best film of all time and the second best science fiction film.

On October 22, 2012, Madame Tussauds unveiled wax likenesses of E.T. at six of its international locations.[84]

20th anniversary version

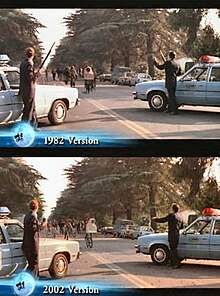

An extended version of the film, including altered special effects, was released on March 22, 2002. Certain shots of E.T. had bothered Spielberg since 1982, as he did not have enough time to perfect the animatronics. Computer-generated imagery (CGI), provided by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), was used to modify several shots, including ones of E.T. running in the opening sequence and being spotted in the cornfield. The spaceship's design was also altered to include more lights. Scenes shot for but not included in the original version were introduced. These included E.T. taking a bath, and Gertie telling Mary that Elliott went to the forest on Halloween night. Spielberg did not add the scene featuring Harrison Ford, feeling that would reshape the film too drastically. Spielberg became more sensitive about the scene where gun-wielding federal agents confront Elliott and his escaping friends and had the guns digitally replaced with walkie-talkies.[5]

At the premiere, John Williams conducted a live performance of the score.[85] The new release grossed $68 million in total, with $35 million coming from Canada and the United States.[54] The changes to the film, particularly the escape scene, were criticized as political correctness. Peter Travers of Rolling Stone wondered, "Remember those guns the feds carried? Thanks to the miracle of digital, they're now brandishing walkie-talkies.... Is this what two decades have done to free speech?"[86] Chris Hewitt of Empire wrote, "The changes are surprisingly low-key...while ILM's CGI E.T. is used sparingly as a complement to Carlo Rambaldi's extraordinary puppet."[87] South Park ridiculed many of the changes in the 2002 episode "Free Hat".[88]

The two-disc DVD release which followed in October 22, 2002 contained the original theatrical and 20th Anniversary extended versions of the film. Spielberg personally demanded the release to feature both versions.[89] The two-disc edition, as well as a three-disc collector's edition containing a "making of" book and special features that were unavailable on the two-disc edition,[90] were placed in moratorium on December 31, 2002. Later, E.T. was re-released on DVD as a single-disc re-issue in 2005, featuring only the 20th Anniversary version.

In a June 2011 interview, Spielberg said that in the future

There's going to be no more digital enhancements or digital additions to anything based on any film I direct.... When people ask me which E.T. they should look at, I always tell them to look at the original 1982 E.T. If you notice, when we did put out E.T. we put out two E.T.s. We put out the digitally enhanced version with the additional scenes and for no extra money, in the same package, we put out the original '82 version. I always tell people to go back to the '82 version.[91]

A 30th Anniversary edition was released on October 9, 2012 for Blu-ray and DVD, which included a fully restored version of the original film, re-instating the original animatronic close-ups and the shotguns.[92]

Other portrayals

In July 1982, during the film's first theatrical run, Spielberg and Mathison wrote a treatment for a sequel to be titled E.T. II: Nocturnal Fears. It would have shown Elliott and his friends kidnapped by evil aliens and follow their attempts to contact E.T. for help. Spielberg decided against pursuing the sequel, feeling it "would do nothing but rob the original of its virginity".[93]

Atari, Inc. made a video game based on the film for the Atari 2600. Released in 1982, it was widely considered to be one of the worst video games ever made.

William Kotzwinkle, author of the film's novelization, wrote a sequel, E.T.: The Book of the Green Planet, which was published in 1985. In the novel, E.T. returns home to the planet Brodo Asogi, but is subsequently demoted and sent into exile. E.T. then attempts to return to Earth by effectively breaking all of Brodo Asogi's laws.[94] E.T. Adventure, a theme park ride, debuted at Universal Studios Florida in 1990. The $40 million attraction features the title character saying goodbye to visitors by name.[12]

In 1998, E.T. was licensed to appear in television public service announcements produced by the Progressive Corporation. The announcements featured E.T.'s voice reminding drivers to "buckle up" their safety belts. Traffic signs depicting a stylized E.T. wearing a safety belt were installed on selected roads around the United States.[95] The following year, British Telecommunications launched the "Stay in Touch" campaign, with E.T. as the star of various advertisements. The campaign's slogan was "B.T. has E.T.", with "E.T." also taken to mean "extra technology".[96] At Spielberg's suggestion, George Lucas included members of E.T.'s species as background characters in Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999).[97]

See also

References

- ^ Stewart, Jocelyn (February 10, 2008). "Artist created many famous film posters". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c "E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Steve Daly (March 22, 2002). "Starry Role". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Brode 1995, p. 117

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial: The 20th Anniversary Celebration (DVD). Universal, directed by Laurent Bouzereau. 2002.

- ^ a b Ian Nathan (January 2003). "The 100 DVDs You Must Own". Empire. p. 27.

- ^ a b c d E.T. — The Reunion (DVD). Universal, directed by Laurent Bouzereau. 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f g Douglas Brode (1995). "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial". The Films of Steven Spielberg. Citadel. pp. 114–127. ISBN 0-8065-1540-6.

- ^ "The Making of E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial"--from the "E.T. Signature Collection LaserDisc", MCA/Universal Home Video, 1996

- ^ Natalie Jamieson (July 16, 2008). "The man who brings movies to life". Newsbeat. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 72

- ^ a b c d e f g h Joseph McBride (1997). Steven Spielberg. Faber and Faber. pp. 323–38. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- ^ Deborah Caulfield (May 23, 1983). "E.T. Gossip: The One That Got Away?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial: Production Notes (DVD booklet)

- ^ Paul M. Sammon (January 11, 1983). "Turn on Your Heartlight – Inside E.T." Cinefex. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008.

- ^ "Creating A Creature". Time. May 31, 1982. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ a b David van Biema (July 26, 1983). "Life is Sweet for Jack Dowd as Spielberg's Hit Film Has E.T. Lovers Picking up the (Reeses's) Pieces". People.

- ^ Worsley 1997, p. 179

- ^ "Biography". QRZ.com. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ a b David E. Williams (January 1983). "An Exceptional Encounter". American Cinematographer. pp. 34–7.

- ^ James Lipton (host). (2001). Inside the Actors Studio: Steven Spielberg. [Documentary]. Bravo.

- ^ John Williams (2002). A Conversation with John Williams (DVD). Universal.

- ^ Karlin, Fred, and Rayburn Wright. On the Track: A Guide to Contemporary Film Scoring. New York: Schirmer Books, 1990.

- ^ John Newman (September 17, 2001). UC Santa Cruz Currents online article "Satyajit Ray Collection receives Packard grant and lecture endowment". University of California, Santa Cruz.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Rahman, Obaidur (May 22, 2009). "Perceptions: Satyajit Ray and The Alien!". Star Weekend Magazine. 8 (70). Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ "Close encounters with native E.T. finally real". The Times of India. April 5, 2003. Retrieved March 24, 2009.

- ^ "Satyajit Ray Collection Receives Packard Grant and Lecture Endowment". University of California. September 18, 2001. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ^ Ray influenced E.T says Martin Scorsese – Times Of India

- ^ a b Judith Crist (1984). "Take 22: Moviemakers on Moviemaking". Viking.

- ^ a b Charles Taylor (March 22, 2002). "You can go home again". Salon. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ^ Gary Arnold (June 6, 1982). "E.T. Steven Spielberg's Joyful Excursion, Back to Childhood, Forward to the Unknown". The Washington Post.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 13

- ^ Thomas A. Sebeok. "Enter Textuality: Echoes from the Extra-Terrestrial." In Poetics Today (1985), Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics. Published by Duke University Press.

- ^ a b Ilsa J. Beck, "The Look Back in E.T.," Cinema Journal 31(4) (1992): 25–41, 33.

- ^ a b A.O. Scott (March 22, 2002). "Loss and Love, A Tale Retold". The New York Times. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ Wuntch, Philip (July 19, 1985). "Return of E.T.". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Henry Sheehan (May–June 1992). "The Panning of Steven Spielberg". Film Comment. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ Rubin 2001, p. 53

- ^ Stanley Kauffmann (July 5, 1982). "The Gospel According to St. Steven". The New Republic.

- ^ Anton Karl Kozlovic. "The Structural Characteristics of the Cinematic Christ-figure," Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 8 (Fall 2004).

- ^ Nigel Andrews. "Tidings of comfort and joy." Financial Times (December 10, 1982), I11

- ^ a b Andrew Gordon. "E.T. as a Fairy Tale," Science Fiction Studies 10 (1983): 298–305.

- ^ Rubin 2001, p. 22

- ^ Richard Schickel (interviewer) (July 9, 2007). Spielberg on Spielberg. Turner Classic Movies.

- ^ a b Roger Ebert (August 9, 1985). "E.T.: The Second Coming". Movieline.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ^ "E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial — Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Top Films of All-Time: Part 1 – Box-Office Blockbusters". Filmsite.org. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Wuntch, Philip (July 19, 1985). "Return of E.T." The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ "Spielberg's Creativity" (Fee required). The New York Times. December 25, 1982. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Jim Callo (August 23, 1982). "Director Steven Spielberg Takes the Wraps Off E.T., Revealing His Secrets at Last". People.

- ^ "Yours Free From E.T. With Membership". Ahoy! (advertisement). 1984-01. p. 91. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (Re-issue)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ a b "E.T. (20th Anniversary)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ "Jurassic Park (1993) – Miscellaneous notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2011-0-6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Dirks, Tim. "Greatest Movie Series Franchises of All Time: The Star Wars Trilogy – Part IV". Filmsite.org. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Nancy Griffin (June 1988). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Premiere.

- ^ "Report of the Joint Select Committee" (PDF). Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- ^ "50 Most Magical Movie Moments". Empire. January 2004. p. 127. "ET's bike flight 'cinema's most magical moment'". Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Michael Sragow (July 8, 1982). "Extra-Terrestrial Perception". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Leonard Maltin. "100 Must-See Films of the 20th Century". AMC Filmsite.

- ^ George Will (July 19, 1982). "Well, I Don't Love You, E.T.". Newsweek.

- ^ "100 Best-Reviewed Sci-Fi Movies". Rotten Tomatoes. 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (re-release)". Metacritic. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- ^ "U.N. Finds E.T. O.K.". The Twilight Zone Magazine. February 1983.

- ^ Shay & Duncan 1993, p. 122

- ^ "The 55th Academy Awards (1983) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "E.T. Awards". Allmovie. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "Awards for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ "America's Most Heart-Pounding Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ "America's Most Uplifting Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ American Film Institute (June 17, 2008). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Lines". Premiere. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains Ballot

- ^ "100 Greatest Family Films". Channel 4. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Richard Corliss (February 12, 2005). "E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)". Time. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "#8 E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial". Entertainment Weekly. November 19, 2003. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ Gregory Kirschling (May 7, 2007). "The Sci-Fi 25". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- ^ Michael Moran (October 5, 2007). "The 40 most memorable aliens". The Times. London. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ^ "Films Selected to The National Film Registry, Library of Congress 1989–2006". National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ "E.T. IMMORTALIZED IN WAX AROUND THE WORLD". Associated Press. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Live at the Shrine! John Williams and the premiere of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Universal. 2002.

{{cite AV media}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Peter Travers (March 14, 2002). "E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ Chris Hewitt. "E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: 20th Anniversary Special Edition". Empire. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ Trey Parker, Matt Stone (July 10, 2002). "Free Hat". South Park. Season 6. Episode 88. Comedy Central.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help) - ^ "How Does Spielberg Feel About Going Back and Changing Movies". YouTube. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ Richard Schuchardt (October 24, 2002). "E.T. – The 3 Disc Edition". DVD Active. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ Quint (aka Eric Vespe) (June 3, 2011). "Spielberg Speaks! Jaws Blu-Ray in the Works with No 'Digital Corrections!". Ain't It Cool News. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Universal Studios Home Entertainment (July 26, 2012). "From Universal Studios Home Entertainment: E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial" (Press release). Digital Journal. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ John M. Wilson (June 16, 1985). "E.T. Returns to Test His Midas Touch". Los Angeles Times. p. T22.

- ^ Kotzwinkle 1985

- ^ Nick Madigan (December 29, 1998). "E.T. to drive home safe road message: The Buckle Up program to air alien's plea during Super Bowl XXXIII". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ "ET phones home again". BBC News. April 8, 1999. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ David Bloom (June 13, 1999). "Calling the shots". Los Angeles Daily News.

Bibliography

- Brode, Douglas (1995). The Films of Steven Spielberg. Carol Publishing. ISBN 0-8065-1951-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kotzwinkle, William (1985). E.T.: The Book of the Green Planet. Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-07642-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McBride, Joseph (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80900-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rubin, Susan Goldman (2001). Steven Spielberg. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-4492-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shay, Don; Duncan, Jody (2001). The Making of Jurassic Park: An Adventure 65 Million Years in the Making. Boxtree. ISBN 1-85283-774-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Worsley, Sue Dwiggins (1997). From Oz to E.T.: Wally Worsley's Half-Century in Hollywood. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3277-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Official homepage for the 20th anniversary edition

- Nocturnal Fears[dead link] Sequel treatment by Spielberg and Melissa Mathison

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial at IMDb

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial at AllMovie

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial at Rotten Tomatoes

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial at Box Office Mojo

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial at Metacritic

- 1982 films

- 1980s science fiction films

- 1985 novels

- Amblin Entertainment films

- American science fiction films

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

- English-language films

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Films produced by Steven Spielberg

- Films set in the San Fernando Valley

- Films shot in Los Angeles, California

- Films that won the Best Sound Mixing Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Pictures films

- Film scores by John Williams

- Films that won the Best Sound Editing Academy Award