Hyperloop

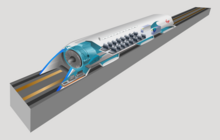

The Hyperloop is a conceptual high-speed transportation system put forward by entrepreneur Elon Musk,[1][2] incorporating reduced-pressure tubes in which pressurized capsules ride on an air cushion driven by linear induction motors and air compressors.[3] As of 2015[update], designs for test tracks and capsules are being developed, with construction of a full-scale prototype scheduled for 2016.[4]

A preliminary design document was made public in August 2013, which included a suggested route running from the Los Angeles region to the San Francisco Bay Area, paralleling the Interstate 5 corridor for most of its length. Preliminary analysis indicated that such a route might obtain an expected journey time of 35 minutes, meaning that passengers would traverse the 354-mile (570 km) route at an average speed of around 598 mph (962 km/h), with a top speed of 760 mph (1,220 km/h). Cost estimates were US$6 billion for a passenger-only version, and US$7.5 billion for a version transporting passengers and vehicles.[2]

The cost projections for the suggested California route were questioned by transportation engineers in 2013, who found the sum unrealistically low given the scale of construction and reliance on unproven technology. The technological and economic feasibility of the idea is unproven and a subject of significant debate.[5][6][7][8]

History

Elon Musk first mentioned that he was thinking about a concept for a "fifth mode of transport", calling it the Hyperloop, in July 2012 at a PandoDaily event in Santa Monica, California. He described several characteristics of what he wanted in a hypothetical high-speed transportation system: immunity to weather, cars that never experience crashes, an average speed twice that of a typical jet, low power requirements, and the ability to store energy for 24-hour operations.[9]

Musk has likened the Hyperloop to a "cross between a Concorde and a railgun and an air hockey table,"[10] while noting that it has no need for rails.[9][11] He believes it could work either below or above ground.[12]

From late 2012 until August 2013, an informal group of engineers at both Tesla and SpaceX worked on the conceptual foundation and modelling of Hyperloop, allocating some full-time effort to it toward the end.[13] An early design for the system was then published in a white paper posted to the Tesla and SpaceX blogs.[2][14] Musk has also said he invites feedback to "see if the people can find ways to improve it"; it will be an open source design, with anyone free to use and modify it.[15] The following day he announced a plan to construct a demonstration of the concept.[13][needs update]

In January 2015, Musk announced that he would construct a Hyperloop test track, which may be located in Texas. The track would be a loop of around 5 miles (8 km) in length and would be entirely privately funded. It would allow university and private teams to test and refine different transport pod designs.[16][17]

In June 2015, SpaceX announced that it would build a 1-mile-long (1.6 km) test track to be located next to SpaceX's Hawthorne facility. The track would be used to test pod designs supplied by third parties that are entered into a design competition.[18][19] Construction on a 5-mile (8 km) Hyperloop test track is to start on a Hyperloop Transportation Technologies-owned site in Quay Valley in 2016.[20][21]

Theory and operation

Developments in high-speed rail, and in high-speed transport more generally, have historically been impeded by the difficulties in managing friction and air resistance, both of which become substantial when vehicles approach high speeds. The vactrain concept theoretically eliminates these obstacles by employing magnetically levitating trains in evacuated (airless) or partly evacuated tubes or tunnels, allowing for theoretical speeds of thousands of miles per hour. However, the high cost of maglev and the difficulty of maintaining a vacuum over large distances has prevented this type of system from ever being built. The Hyperloop resembles a vactrain system but operates at approximately one millibar (100 Pa) of pressure.[22]

Initial design concept

The Hyperloop concept is proposed to operate by sending specially designed "capsules" or "pods" through a continuous steel tube maintained at a partial vacuum. Each capsule floats on a 0.5-to-1.3-millimetre (0.02 to 0.05 in) layer of air provided under pressure to air-bearing "skis", similar to how pucks are suspended in an air hockey table, thus avoiding the use of maglev while still allowing for speeds that wheels cannot sustain. Linear induction motors located along the tube would accelerate and decelerate the capsule to the appropriate speed for each section of the tube route. With rolling resistance eliminated and air resistance greatly reduced, the capsules are theorized to be able to glide for the bulk of the journey. In the Hyperloop concept, an electrically driven inlet fan and air compressor would be placed at the nose of the capsule in order to "actively transfer high pressure air from the front to the rear of the vessel," resolving the problem of high speed transport in a tube that is not a hard vacuum, wherein pressure builds up in front of the vehicle, slowing it down.[2] A fraction of the air is shunted to the skis for additional air pressure, augmenting that gain passively from lift due to their shape.

In the alpha-level concept, passenger-only pods are to be 2.23 metres (7 ft 4 in) in diameter[2] and projected to reach a top speed of 760 mph (1,220 km/h) so as to maintain aerodynamic efficiency;[citation needed] the design proposes passengers experience a maximum inertial acceleration of 0.5 g, about 2 or 3 times that of a commercial airliner on takeoff and landing. At those speeds there would not be a sonic boom; with low-pressure warm air inside the tubes, Musk hypothesizes the pods could travel at high speeds without exceeding Mach 1.[23]

Suggested route

The suggested route for the Greater Los Angeles Area to the San Francisco Bay Area system outlined in the alpha-level design document would begin around Sylmar, just south of the Tejon Pass, approximately follow the I-5 highway to the north, and arrive at a station near Hayward on the east side of San Francisco Bay. Several proposed branches were also shown in the design document, including Sacramento, Anaheim, San Diego, and Las Vegas.[2]

While terminating the Hyperloop route on the fringes of the two major metropolitan areas would result in significant cost savings in construction, it would require that passengers traveling to and from Downtown Los Angeles and San Francisco, and any other community beyond Sylmar and Hayward, transfer to another transportation mode in order to reach their final destination. This would significantly lengthen the total travel time to those destinations.[8] A similar problem already affects present day air travel, where on short routes (like LAX-SFO) the travel time between airport and airport is only a rather small part of door to door travel time. Critics have argued that this would significantly reduce the proposed cost and/or time savings of Hyperloop as compared to the California High Speed Rail project that will serve downtown stations in both San Francisco and Los Angeles.[24][25][26]

Open-source design evolution

In September 2013, Ansys Corporation ran computational fluid dynamics simulations to model the aerodynamics of the capsule and shear stress forces that the capsule would be subjected to. The simulation showed that the capsule design would need to be significantly reshaped to avoid creating supersonic airflow, and that the gap between the tube wall and capsule would need to be larger.[27][28] Ansys employee Sandeep Sovani said the simulation showed that Hyperloop has challenges but that he is convinced it is feasible.[27]

In October 2013, the development team of the OpenMDAO software framework released an unfinished, conceptual open-source model of parts of the Hyperloop's propulsion system. The team asserted that the model demonstrated the concept's feasibility, although the tube would need to be 13 feet (4 m) in diameter,[29] significantly larger than originally projected. However, the team's model is not a true working model of the propulsion system, as it did not account for a wide range of technological factors required to physically construct a Hyperloop based on Musk's concept, and in particular had no significant estimations of component weight.[30]

In November 2013, MathWorks analyzed the proposal's suggested route and concluded that the route was mainly feasible. The analysis focused on the acceleration experienced by passengers and the necessary deviations from public roads in order to keep the accelerations reasonable; it did highlight that maintaining a trajectory along I-580 east of San Francisco at the planned speeds was not possible without significant deviation into heavily populated areas.[31]

In January 2015, a paper based on the NASA OpenMDAO open-source model reiterated the need for a larger diameter tube and a reduced cruise speed closer to Mach 0.85. It also recommended removing on-board heat exchangers based on thermal models from the interactions between the compressor cycle, tube, and ambient environment. The compression cycle would only contribute 5% of the heat added to the tube, with 95% of the heat attributed to radiation and convection into the tube. The weight and volume penalty of on-board heat exchangers would not be worth the minor benefit, and regardless the steady-state temperature in the tube would only reach 30–40 °F (17–22 °C) above ambient temperature.[32]

Groups acquiring funding and building hardware

Hyperloop Transportation Technologies

Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT) is a group of approximately 100 engineers located across the United States who collaborate by crowdsourcing through weekly teleconferences. Rather than being paid directly, members work in exchange for stock options. The company is exploring routes other than the Los Angeles to San Francisco route that was the baseline in the Hyperloop alpha design. They are projecting the completion of a technical feasibility study in 2015, but have said that they are at least ten years away from a commercially operating Hyperloop.[33]

HTT announced in May 2015 that a deal had been finalized with landowners to build a 5-mile (8 km) test track along a stretch of road near Interstate 5 between Los Angeles and San Francisco.[34] Later in 2015, HTT announced partnerships with Oerlikon Leybold Vacuum and AECOM to assist in the development and construction of the test track,[4] located in the planned community of Quay Valley, beginning in November 2015 and estimated to take 32 months to complete at a cost of US$150 million.[35] Passenger capsules will accelerate to 160 miles per hour (260 km/h), while empty capsules will be tested at the full 760 mph (1,220 km/h).[35]

Hyperloop Technologies

Hyperloop Technologies announced in February 2015 their plan to develop a Hyperloop route between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. They have organized a board of directors and an engineering team, and have starting capital of US$8.5 million.[36]

SpaceX-funded prototype track

On June 15, 2015, SpaceX announced that they intended to hold a Hyperloop pod design competition, and would build a 1-mile-long (1.6 km) subscale test track near SpaceX's headquarters in Hawthorne, California, for the competitive event. The competition may be held as early as June 2016.[37][38]

SpaceX stated in their announcement, "Neither SpaceX nor Elon Musk is affiliated with any Hyperloop companies. While we are not developing a commercial Hyperloop ourselves, we are interested in helping to accelerate development of a functional Hyperloop prototype."[39]

The competition was announced on June 15, 2015, and more than 700 teams had submitted preliminary applications by July.[40] Detailed competition rules were released on August 20, 2015.[41] Intent to Compete submissions were due September 15, 2015 and the detailed tube and technical specification was due to be released by SpaceX in October 2015. A preliminary design briefing was scheduled to be held in November 2015, with Final Design Packages due by 13 January 2016. A Design Weekend will be held at Texas A&M University on January 29–30, 2016 for all invited entrants. The selected pods will compete at the SpaceX Hyperloop Test Track in mid 2016.[42]

More than 120 student engineering teams were selected from the preliminary design briefing presentations in November to submit final design packages in January 2016. The designs will be released to public view prior to the end of January 2016, and selected teams will be invited to build hardware and compete in time trials in mid-2016.[43]

Human factors considerations

Some critics of Hyperloop focus on the experience—possibly unpleasant and frightening—of riding in a narrow, sealed, and windowless capsule inside a sealed steel tunnel, that is subjected to significant acceleration forces, high noise levels due to air being compressed and ducted around the capsule at near-sonic speeds, and the vibration and jostling.[44] Even if the tube is initially smooth, ground shifting due to settling and ongoing seismic activity would inevitably cause distortion. At speeds approaching 900 feet per second (270 m/s), deviations of even 1 millimeter (0.039 in) from a straight path would add considerable buffeting and vibration, with no provisions for passengers to stand, move within the capsule, use a restroom during the trip, or get assistance or relief in case of illness or motion sickness.[45]

Political and economic considerations

The alpha proposal projected that cost savings compared with conventional rail would come from a combination of several factors. The small profile and elevated nature of the alpha route would enable Hyperloop to be constructed primarily in the median of Interstate 5. However, whether this would be truly feasible is a matter of debate. The low profile would reduce tunnel boring requirements and the light weight of the capsules is projected to reduce construction costs over conventional passenger rail. It was asserted that there would be less right-of-way opposition and environmental impact as well due to its small, sealed, elevated profile versus that of a rail easement;[2] however, other commentators contend that a smaller footprint does not guarantee less opposition.[8] In criticizing this assumption, mass transportation writer Alon Levy said,[46] "In reality, an all-elevated system (which is what Musk proposes with the Hyperloop) is a bug rather than a feature. Central Valley land is cheap; pylons are expensive, as can be readily seen by the costs of elevated highways and trains all over the world".[47] Michael Anderson, a professor of agricultural and resource economics at UC Berkeley, predicted that costs would amount to around US$100 billion.[6]

The Hyperloop white paper suggests that US$20 of each one-way passenger ticket between Los Angeles and San Francisco would be sufficient to cover initial capital costs, based on amortizing the cost of Hyperloop over 20 years with ridership projections of 7.4 million per year in each direction and does not include operating costs (although the proposal asserts that electric costs would be covered by solar panels). No total ticket price was suggested in the alpha design.[2] The projected ticket price has been questioned by Dan Sperling, director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis, who told Al Jazeera America that "there's no way the economics on that would ever work out."[6]

The early cost estimates of the Hyperloop are a subject of debate. A number of economists and transportation experts have expressed the belief that the US$6 billion price tag dramatically understates the cost of designing, developing, constructing and testing an all-new form of transportation.[5][6][8][47] The Economist said that the estimates are unlikely to "be immune to the hypertrophication of cost that every other grand infrastructure project seems doomed to suffer."[48]

Political impediments to the construction of such a project in California will be very large. There is a great deal of "political and reputational capital" invested in the existing mega-project of California High-Speed Rail.[48] Replacing that with a different design would not be straightforward given California's political economy. Texas has been suggested as an alternate for its more amenable political and economic environment.[48]

Building a successful Hyperloop sub-scale demonstration project could reduce the political impediments and improve cost estimates. Musk has suggested that he may be personally involved in building a demonstration prototype of the Hyperloop concept, including funding the development effort.[13][48]

Related projects

Historical

In 1812, the British mechanical engineer and inventor George Medhurst wrote a book detailing his idea of transporting passengers and goods through air-tight tubes using air propulsion.[49]

The Crystal Palace pneumatic railway operated in London around 1864 and used large fans, some 22 feet (6.7 m) in diameter, that were powered by a steam engine. The tunnels are now lost but the line operated successfully for over a year.

Opened in 1870, the Beach Pneumatic Transit was a one block-long prototype of an underground tube transport public transit system in New York City. The system worked at near-atmospheric pressure, and the passenger car moved by means of higher-pressure air applied to the back of the car while somewhat lower pressure was maintained on the front of the car.[50]

In the 1910s, vacuum trains were first described by American rocket pioneer Robert Goddard.[48] While the Hyperloop has significant innovations over early proposals for reduced pressure or vacuum-tube transportation apparatus, the work of Goddard "appears to have the greatest overlap with the Hyperloop".[3]

Swissmetro was a proposal to run a maglev train in a low-pressure environment. Concessions were granted to Swissmetro in the early 2000s to connect the Swiss cities of St. Gallen, Zurich, Basel, and Geneva. Studies of commercial feasibility reached differing conclusions and the vactrain was never built.[51]

Current

The ET3 Global Alliance (ET3) was founded by Daryl Oster in 1997 with the goal of establishing a global transportation system using passenger capsules in frictionless maglev full-vacuum tubes. Oster and his team met with Elon Musk on September 18, 2013, to discuss the technology,[52] resulting in Musk promising an investment in a 3-mile (5 km) prototype of ET3's proposed design.[53][needs update]

See also

References

- ^ Garber, Megan (July 13, 2012). "The Real iPod: Elon Musk's Wild Idea for a 'Jetson Tunnel' from S.F. to L.A." The Atlantic. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Musk, Elon (August 12, 2013). "Hyperloop Alpha" (PDF). SpaceX. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beyond the hype of Hyperloop: An analysis of Elon Musk's proposed transit system". Gizmag.com. August 22, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Hower, Mike (August 24, 2015). "Musk's 'Hyperloop' on Track to Start Construction in 2016". Sustainable Brands. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Bilton, Nick. "Could the Hyperloop Really Cost $6 Billion? Critics Say No". The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Brownstein, Joseph (August 14, 2013). "Economists don't believe the Hyperloop". Al Jazeera America.

- ^ Melendez, Eleazar David (August 14, 2013). "Hyperloop Would Have 'Astronomical' Pricing, Unrealistic Construction Costs, Experts Say". The Huffington Post.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Matt (August 14, 2013). "Musk's Hyperloop math doesn't add up". Greater Greater Washington.

- ^ a b Pensky, Nathan; Lacy, Sarah; Musk, Elon (July 12, 2012). PandoMonthly Presents: A Fireside Chat with Elon Musk. PandoDaily/YouTube.com. Event occurs at 43:13. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Gannes, Liz (May 30, 2013). "Tesla CEO and SpaceX Founder Elon Musk: The Full D11 Interview (Video)". All Things Digital. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ Rose, Kevin (September 7, 2012). "Foundation 20 // Elon Musk". YouTube.com. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Staff; Musk, Elon (June 18, 2013). Tech Summit 2013: Tesla's Musk gears up for sales battle. Reuters Insider. Event occurs at 38:49–43:12. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Musk announces plans to build Hyperloop demonstrator". Gizmag.com. August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Musk, Elon (August 12, 2013). "Hyperloop". Tesla. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ Mendoza, Martha (August 12, 2013). "Elon Musk to reveal mysterious 'Hyperloop' high-speed travel designs Monday". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ Batheja, Aman (January 15, 2015). "Musk: Texas a "Leading Candidate" for Hyperloop Track". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ Davies, Alex (January 15, 2015). "With a Hyperloop Test Track, Elon Musk Takes on the Critical Heavy Lifting". Wired. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (June 15, 2015). "SpaceX to hold Hyperloop competition". CNN Money. CNN.

- ^ Baker, David R. (June 15, 2015). "Build your own hyperloop! SpaceX announces pod competition". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Maia Pujara (August 7, 2015). "Hyperloop Rapid Transit System Construction to Start in 2016". Voice of America. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ Mack, Eric (February 26, 2015). "California is getting a Hyperloop, but not where you think". Gizmag. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ De Chant, Tim (August 13, 2013). "Promise and Perils of Hyperloop and Other High-Speed Trains". PBS.org. Nova Next. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ Vance, Ashlee (August 13, 2013). "Revealed: Elon Musk Explains the Hyperloop, the Solar-Powered High-Speed Future of Inter-City Transportation". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ https://pedestrianobservations.wordpress.com/2013/08/13/loopy-ideas-are-fine-if-youre-an-entrepreneur/

- ^ http://stopandmove.blogspot.de/2013/08/hyperloop-proposal-bad-joke-or-attempt.html

- ^ http://greatergreaterwashington.org/post/19848/musks-hyperloop-math-doesnt-add-up/

- ^ a b Danigelis, Alyssa (September 20, 2013). "Hyperloop Simulation Shows It Could Work". Discovery News. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Statt, Nick (September 19, 2013). "Simulation verdict: Elon Musk's Hyperloop needs tweaking". CNET News. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ "Hyperloop in OpenMDAO". OpenMDAO. October 9, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Future Modeling Road Map". OpenMDAO. October 9, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Hyperloop: Not So Fast". MathWorks. November 22, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Chin, Jeffrey C.; Gray, Justin S.; Jones, Scott M.; Berton, Jeffrey J. (January 2015). Open-Source Conceptual Sizing Models for the Hyperloop Passenger Pod (PDF). 56th AIAA/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference. January 5–9, 2015. Kissimmee, Florida. doi:10.2514/6.2015-1587.

- ^ Davies, Alex (December 18, 2014). "These Dreamers Are Actually Making Progress Building Elon's Hyperloop". Wired. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Daniel (May 20, 2015). "Elon Musk's craziest project is coming closer to reality". Fortune. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Mairs, Jessica (October 22, 2015). "Hyperloop's test track will be 'closest thing to teletransportation'". de Zeen. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Upbin, Bruce (February 11, 2015). "Hyperloop Is Real: Meet The Startups Selling Supersonic Travel". Forbes. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (June 15, 2015). "Elon Musk's SpaceX Plans Hyperloop Pod Races at California HQ in 2016". NBC. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Spacex Hyperloop Pod Competition" (PDF). SpaceX. June 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Hyperloop". SpaceX. Space Exploration Technologies. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Cadie (June 23, 2015). "More than 700 people have signed up to help Elon Musk build a Hyperloop prototype". Business Insider. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ "Hyperloop Competition Rules, v2.0" (PDF). SpaceX. October 20, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ "SpaceX Design Weekend at Texas A&M University". Dwight Look College of Engineering, Texax A&M. Texas A&M University. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (December 15, 2015). "More than 120 teams picked for SpaceX founder Elon Musk's Hyperloop contest". Geekwire.com. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Blodget, Henry (August 20, 2013). "Transport Blogger Ridicules The Hyperloop – Says It Will Cost A Fortune And Be A Terrifying 'Barf Ride'". Business Insider.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (August 16, 2013). "Speed bumps and vomit are the Hyperloop's biggest challenges". The Verge.

- ^ Salam, Reihan (August 9, 2011). "Alon Levy on Politicals vs. Technicals". National Review. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Plumer, Brad (August 13, 2013). "There is no redeeming feature of the Hyperloop". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e "The Future of Transport: No loopy idea". The Economist. Vol. Print edition. August 17, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ^ Anderson, Chris C. (July 15, 2013). "If Elon Musk's Hyperloop Sounds Like Something Out Of Science Fiction, That's Because It Is". Business Insider. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Beach, Alfred Ely (March 5, 1870). "The Pneumatic Tunnel Under Broadway, N.Y.". Scientific American. 22 (10): 154–156. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican03051870-154.

- ^ "History". Swissmetro.ch. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Frey, Thomas (October 30, 2013). "Competing for the World's Largest Infrastructure Project: Over 100 Million Jobs at Stake". Futurist Speaker.

- ^ Svaldi, Aldo (August 9, 2013). "Longmont entrepreneur has tubular vision on future of transportation". The Denver Post.

External links

- Tesla Motors: Template:PDFlink

- SpaceX: Template:PDFlink