Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies

Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies Ranryo Higashi Indo 蘭領東印度 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942–1945 | |||||||||||

| Motto: Hakkō ichiu (八紘一宇) | |||||||||||

| Anthem: Kimigayo | |||||||||||

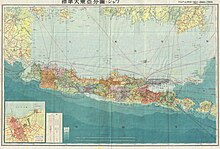

The Empire of Japan in 1942. | |||||||||||

| Status | Military occupation by the Empire of Japan | ||||||||||

| Capital | Djakarta | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Japanese, Indonesian | ||||||||||

| Government | Military occupation | ||||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||||

| 8 March 1942 | |||||||||||

| 27 February 1942 | |||||||||||

| 1 March 1942 | |||||||||||

| 14 February 1945 | |||||||||||

| 2 September 1945 | |||||||||||

| 17 August 1945 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Netherlands Indian roepiah | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Japanese Empire occupied the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, during World War II from March 1942 until after the end of the War in 1945. The period was one of the most critical in Indonesian history. Under German occupation, the Netherlands had little ability to defend its colony against the Japanese army, and less than three months after the first attacks on Borneo,[1] the Japanese navy and army overran Dutch and allied forces. Initially, most Indonesians joyfully welcomed the Japanese, as liberators from their Dutch colonial masters. The sentiment changed, as Indonesians were expected to endure more hardship for the war effort. In 1944–1945, Allied troops largely bypassed Indonesia and did not fight their way into the most populous parts such as Java and Sumatra. As such, most of Indonesia was still under Japanese occupation at the time of their surrender, in August 1945.

The occupation was the first serious challenge to the Dutch in Indonesia and ended the Dutch colonial rule, and, by its end, changes were so numerous and extraordinary that the subsequent watershed, the Indonesian National Revolution, was possible in a manner unfeasible just three years earlier.[2] Unlike the Dutch, the Japanese facilitated the politicisation of Indonesians down to the village level. Particularly in Java and, to a lesser extent, Sumatra, the Japanese educated, trained and armed many young Indonesians and gave their nationalist leaders a political voice. Thus, through both the destruction of the Dutch colonial regime and the facilitation of Indonesian nationalism, the Japanese occupation created the conditions for claiming Indonesian independence within days of the Japanese surrender in the Pacific. However, the Netherlands sought to reclaim the Indies, and a bitter five-year diplomatic, military and social struggle ensued, resulting in the Netherlands recognising Indonesian sovereignty in December 1949.

Background

Until 1942, Indonesia was colonised by the Netherlands and was known as the Dutch East Indies. In 1929, during the Indonesian National Awakening, Indonesian nationalist leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta (later founding President and Vice-President), foresaw a Pacific War and that a Japanese advance on Indonesia might be advantageous for the independence cause.[3]

The Japanese spread the word that they were the 'Light of Asia'. Japan was the only Asian nation that had successfully transformed itself into a modern technological society at the end of the 19th century and it remained independent when most Asian countries had been under European or American power, and had beaten a European power, Russia, in war.[4] Following its military campaign in China Japan turned its attention to Southeast Asia advocating to other Asians a 'Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere', which they described as a type of trade zone under Japanese leadership. The Japanese had gradually spread their influence through Asia in the first half of the 20th century and during the 1920s and 1930s had established business links in the Indies. These ranged from small town barbers, photographic studios and salesmen, to large department stores and firms such as Suzuki and Mitsubishi becoming involved in the sugar trade.[5]

The Japanese population peaked in 1931, with 6,949 residents before starting a gradual decrease, largely due to economic tensions between Japan and the Netherlands Indies government.[6] A number of Japanese had been sent by their government to establish links with Indonesian nationalists, particularly with Muslim parties, while Indonesian nationalists were sponsored to visit Japan. Such encouragement of Indonesian nationalism was part of a broader Japanese plan for an 'Asia for the Asians'.[5] While most Indonesians were hopeful for the Japanese promise of an end to the Dutch racially based system, Chinese Indonesians, who enjoyed a privileged position under Dutch rule, were less optimistic. Also concerned were members of the Indonesian communist underground who followed the Soviet Union's popular united front against fascism.[7] Japanese aggression in Manchuria and China in the late 1930s caused anxiety amongst the Chinese in Indonesia who set up funds to support the anti-Japanese effort. Dutch intelligence services also monitored Japanese living in Indonesia.[8]

In November 1941, Madjlis Rakjat Indonesia, an Indonesian organisation of religious, political and trade union groups, submitted a memorandum to the Dutch East Indies Government requesting the mobilisation of the Indonesian people in the face of the war threat.[9] The memorandum was refused because the Government did not consider the Madjlis Rakyat Indonesia to be representative of the people. Within only four months, the Japanese had occupied the archipelago.

The invasion

On 8 December 1941, the Netherlands declared war on Japan.[10] In January the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) was formed to co-ordinate Allied forces in South East Asia, under the commander of General Archibald Wavell.[11] In the weeks leading up to the invasion, senior Dutch government officials went into exile taking political prisoners, family, and personal staff to Australia. Before the arrival of Japanese troops, there were conflicts between rival Indonesian groups where people were killed, vanished or went into hiding. Chinese- and Dutch-owned properties were ransacked and destroyed.[12]

The invasion in early 1942 was swift and complete. By January 1942, parts of Sulawesi and Kalimantan were under Japanese control.[13] By February, the Japanese had landed on Sumatra where they had encouraged the Acehnese to rebel against the Dutch.[13] On 19 February, having already taken Ambon, the Japanese Eastern Task Force landed in Timor, dropping a special parachute unit into West Timor near Kupang, and landing in the Dili area of Portuguese Timor to drive out the Allied forces which had invaded in December.[14] On 27 February, the Allied navy's last effort to contain Japan was swept aside by their defeat in the Battle of the Java Sea.[15] From 28 February to 1 March 1942, Japanese troops landed on four places along the northern coast of Java almost undisturbed.[16] The fiercest fighting had been in invasion points in Ambon, Timor, Kalimantan, and on the Java Sea. In places where there were no Dutch troops, such as Bali, there was no fighting.[17] On 9 March, the Dutch commander surrendered along with Governor General Jonkheer A.W.L. Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer.[13]

The Japanese occupation was initially greeted with optimistic enthusiasm by Indonesians who came to meet the Japanese army waving flags and shouting support such as "Japan is our older brother" and "banzai Dai Nippon". As the Japanese advanced, rebellious Indonesians in virtually every part of the archipelago killed groups of Europeans (particularly the Dutch) and informed the Japanese reliably on the whereabouts of larger groups.[18] As famed Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer noted: "With the arrival of the Japanese just about everyone was full of hope, except for those who had worked in the service of the Dutch.[19]"

The occupation

The colonial army was consigned to detention camps and Indonesian soldiers were released.[citation needed] Expecting that Dutch administrators would be kept by the Japanese to run the colony, most Dutch had refused to leave. Instead, they were sent to concentration camps and Japanese or Indonesian replacements could be found for senior and technical positions.[20] Japanese troops took control of government infrastructure and services such as ports and postal services.[17] In addition to the 100,000 European (and some Chinese) civilians interned, 80,000 Dutch, British, Australia, and US Allied troops went to prisoner-of-war camps where the death rates were between 13 and 30 per cent.[21]

The Indonesian ruling classes and politicians cooperated with the Japanese who kept the local elites in power and used them to supply Japanese industries and armed forces. Indonesian co-operation allowed the Japanese to focus on securing the archipelago's waterways and skies, and using its islands as defence posts against Allied attack.[22] Japanese rulers divided Indonesia into three regions; Sumatra was placed under the 25th Army, Java and Madura were under the 16th Army, while Borneo and eastern Indonesia were controlled by the Navy 2nd South Fleet. The 16th and 25th Army were headquartered in Singapore[2] and also controlled Malaya until April 1943, when its command was narrowed to just Sumatra and the headquarters moved to Bukittinggi. The 16th Army was headquartered in Jakarta, while the 2nd South Fleet was headquartered in Makassar.

Experience of the occupation varied considerably, depending upon where one lived and one's social position. Many who lived in areas considered important to the war effort experienced torture, sex slavery, arbitrary arrest and execution, and other war crimes. Many thousands of people were taken away from Indonesia as forced labourers (romusha) for Japanese military projects, including the Burma-Siam and Saketi-Bayah railways, and suffered or died as a result of ill-treatment and starvation. Between four and 10 million romusha in Java were forced to work by the Japanese military.[23] About 270,000 of these Javanese labourers were sent to other Japanese-held areas in South East Asia, Only 52,000 were repatriated to Java, meaning that there was a death rate of 80%.

Tens of thousands of Indonesians were to starve, work as slave labourers, or be forced from their homes. In the National Revolution that followed, tens, even hundreds, of thousands, would die in fighting against the Japanese, Allied forces, and other Indonesians, before Independence was achieved.[24][25] A later United Nations report stated that four million people died in Indonesia as a result of famine and forced labour during the Japanese occupation, including 30,000 European civilian internee deaths.[26] A Dutch government study described how the Japanese military recruited women as prostitutes by force in Indonesia.[27] It concluded that among the 200 to 300 European women working in the Japanese military brothels, "some sixty five were most certainly forced into prostitution." [28] Others, faced with starvation in the refugee camps, agreed to offers of food and payment for work, the nature of which was not completely revealed to them.[29][30][31][32][33]

Materially, whole railway lines, railway rolling stock, and industrial plants in Java were appropriated and shipped back to Japan and Manchuria. British intelligence reports during the occupation noted significant removals of any materials that could be used in the war effort.

Next to Sutan Sjahrir who led the student (Pemuda) underground, the only prominent opposition politician was leftist Amir Sjarifuddin who was given 25,000 guilders by the Dutch in early 1942 to organise an underground resistance through his Marxist and nationalist connections. The Japanese arrested Amir in 1943, and he only escaped execution following intervention from Sukarno, whose popularity in Indonesia and hence importance to the war effort was recognised by the Japanese. Apart from Amir's Surabaya-based group, the most active pro-Allied activities were among the Chinese, Ambonese, and Manadonese.[34]

In South Kalimantan, a scheme by Indonesian nationalists and Dutch against the Japanese was uncovered before the Pontianak incident occurred.[35] According to some sources this happened in September 1943 at Amuntai in South Kalimantan and involved establishing up an Islamic State and expelling the Japanese but the plan was defeated.[36][37]

In 1943 the Japanese beheaded Tengku Rachmadu'llah, a member of the royal family of the Sultanate of Serdang.[38] In the 1943–1944 Pontianak incidents (also known as the Mandor Affair), the Japanese orchestrated a mass arrest of Malay elites and Arabs, Chinese, Javanese, Manadonese, Dayaks, Bugis, Bataks, Minangkabau, Dutch, Indians, and Eurasians in Kalimantan, including all of the Malay Sultans, accused them of plotting to overthrow Japanese rule, and then massacred them.[39][40] The Japanese falsely claimed that all of those ethnic groups and organisations such as the Islamic Pemuda Muhammadijah were involved in a plot to overthrow the Japanese and create a "People's Republic of West Borneo" (Negara Rakyat Borneo Barat).[41] The Japanese claimed that- "Sultans, Chinese, Indonesian government officials, Indians and Arabs, who had been antagonistic to each other, joined together to massacre Japanese.", naming the Sultan of the Pontianak Sultanate as one of the "ringleaders" in the planned rebellion.[42] Up to 25 aristocrats, relatives of the Sultan of Pontianak, and many other prominent individuals were named as participants in the plot by the Japanese and then executed at Mandor.[43][44] The Sultans of Pontianak, Sambas, Ketapang, Soekadana, Simbang, Koeboe, Ngabang, Sanggau, Sekadau, Tajan, Singtan, and Mempawa were all executed by the Japanese, respectively, their names were Sjarif Mohamed Alkadri, Mohamad Ibrahim Tsafidedin, Goesti Saoenan, Tengkoe Idris, Goesti Mesir, Sjarif Saleh, Goesti Abdoel Hamid, Ade Mohamad Arif, Goesti Mohamad Kelip, Goesti Djapar, Raden Abdul Bahri Danoe Perdana, and Mohammed Ahoufiek.[45] They are known as the "12 Dokoh".[46] In Java, the Japanese jailed Syarif Abdul Hamid Alqadrie, the son of Sultan Syarif Mohamad Alkadrie (Sjarif Mohamed Alkadri).[47] Since he was in Java during the executions Hamid II was the only male in his family not killed, while the Japanese beheaded all 28 other male relatives of Pontianak Sultan Mohammed Alkadri.[48] Among the 29 people of the Sultan of Pontianak's family who ere beheaded by the Japanese was the heir to the Pontianak throne.[49] Later in 1944, the Dayaks assassinated a Japanese named Nakatani, who was involved in the incident and who was known for his cruelty. Sultan of Pontianak Mohamed Alkadri's fourth son, Pengeran Agoen (Pangeran Agung), and another son, Pengeran Adipati (Pangeran Adipati), were both killed by the Japanese in the incident.[50] The Japanese had beheaded both Pangeran Adipati and Pangeran Agung,[51] in a public execution.[52] The Japanese extermination of the Malay elite of Pontianak paved the way for a new Dayak elite to arise in its place.[53] According to Mary F. Somers Heidhues, during May and June 1945, some Japanese were killed in a rebellion by the Dayaks in Sanggau.[54] According to Jamie S. Davidson, this rebellion, during which many Dayaks and Japanese were killed, occurred from April through August 1945, and was called the "Majang Desa War".[55] The Pontianak Incidents, or Affairs, are divided into two Pontianak incidents by scholars, variously categorised according to mass killings and arrests, which occurred in several stages on different dates. The Pontianak incident negatively impacted the Chinese community in Kalimantan.[56][57][58][59][60]

The Acehnese Ulama (Islamic clerics) fought against both the Dutch and the Japanese, revolting against the Dutch in February 1942 and against Japan in November 1942. The revolt was led by the All-Aceh Religious Scholars' Association ( PUSA). The Japanese suffered 18 dead in the uprising while they slaughtered up to 100 or over 120 Acehnese.[36][61] The revolt happened in Bayu and was centred around Tjot Plieng village's religious school.[62][63][64][65] During the revolt, the Japanese troops armed with mortars and machine guns were charged by sword wielding Acehnese under Teungku Abduldjalil (Tengku Abdul Djalil) in Buloh Gampong Teungah and Tjot Plieng on 10 and 13 November.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72] In May 1945 the Acehnese rebelled again.[73]

Indonesian nationalism

In the decades before the war, the Dutch had been overwhelmingly successful in suppressing the small nationalist movement in Indonesia such that the Japanese proved fundamental for coming Indonesian independence. During the occupation, the Japanese encouraged and backed Indonesian nationalistic sentiments, created new Indonesian institutions, and promoted nationalist leaders such as Sukarno. The openness now provided to Indonesian nationalism, combined with the Japanese destruction of much of the Dutch colonial state, were fundamental to the Indonesian National Revolution that followed World War 2.[24]

Nonetheless within two months of the occupation the Japanese did not allow the political use of the word Indonesia as the name for a nation, neither did they allow the use of the nationalistic (red and white) Indonesian flag. In fact "any discussion, organisation, speculation or propaganda concerning the political organisation or government of the country" (also in the media) was strictly forbidden. They split up the Dutch East Indies into three separate regions and referred to it as the 'Southern Territories' (Indonesian: Daerah Selatan). While Tokyo prepared the Philippines for independence in 1943, they simultaneously decided to annexe the Indonesian islands into the greater Japanese Empire. Until late 1944 when the Pacific war was at a turning point the Japanese never seriously supported Indonesian independence.[74]

The Japanese regime perceived Java as the most politically sophisticated but economically the least important area; its people were Japan's main resource. As such—and in contrast to Dutch suppression—the Japanese encouraged Indonesian nationalism in Java and thus increased its political sophistication (similar encouragement of nationalism in strategic resource-rich Sumatra came later, but only after it was clear the Japanese would lose the war). The outer islands under naval control, however, were regarded as politically backward but economically vital for the Japanese war effort, and these regions were governed the most oppressively of all. These experiences and subsequent differences in nationalistic politicisation would have profound impacts on the course of the Indonesian Revolution in the years immediately following independence (1945–1950).

To gain support and mobilise Indonesian people in their war effort against the Western Allied force, Japanese occupation forces encouraged Indonesian nationalistic movements and recruiting Indonesian nationalist leaders; Sukarno, Hatta, Ki Hajar Dewantara and Kyai Haji Mas Mansyur to rally the people support for mobilisation centre Putera (Template:Lang-id) on 16 April 1943, replaced with Jawa Hokokai on 1 March 1944. Some of these mobilised populations were sent to forced labour as romusha.

Japanese military also provided Indonesian youth with military trainings and weapons, including the formation of volunteer army called PETA (Pembela Tanah Air – Defenders of the Homeland). The Japanese military trainings for Indonesian youth originally was meant to rally the local's support for the collapsing power of Japanese Empire, but later it has become the significant resource for Republic of Indonesia during Indonesian National Revolution in 1945 to 1949, and also has leads to the formation of Indonesian National Armed Forces in 1945.

On 29 April 1945, Japanese occupation force formed BPUPKI (Indonesian Independence Effort Exploratory Committee) (Template:Lang-ja, Dokuritsu Junbi Chōsakai), a Japanese-organized committee for granting independence to Indonesia. The organisation was founded on 29 April 1945 by Lt. Gen. Kumakichi Harada, the commander of 16th Army in Java. Indonesian independence meeting and discussion were prepared through this organisation.

In addition to new-found Indonesian nationalism, equally important for the coming independence struggle and internal revolution was the Japanese orchestrated economic, political and social dismantling and destruction of the Dutch colonial state.[24]

End of the occupation

General MacArthur wanted to fight his way with Allied troops to liberate Java in 1944–45 but was ordered not to by the joint chiefs and President Roosevelt. The Japanese occupation thus officially ended with Japanese surrender in the Pacific and two days later Sukarno declared Indonesian Independence. However Indonesian forces would spend the next four years fighting the Dutch for independence. American restraint from fighting their way into Java certainly saved many Japanese, Javanese, Dutch and American lives. On the other hand, Indonesian independence would have likely been achieved more swiftly and smoothly had MacArthur had his way and American troops occupied Java.[75] A later UN report stated that four million people died in Indonesia as a result of the Japanese occupation.[76] About 2.4 million people died in Java from famine during 1944–45.[77]

Liberation of the internment camps holding western prisoners was not swift. Conditions were better during post-war internment than under previous internment, for, this time, Red Cross supplies were made available and the Allies made the Japanese order the most heinous and cruel occupiers home. After four months of post-war internment, Western internees were released on the condition they left Indonesia.[citation needed]

Most of the Japanese military personnel and civilian colonial administrators were repatriated to Japan following the war, except for several hundred who were detained for investigations into war crimes, for which some were later put on trial. About 1,000 Japanese soldiers deserted from their units and assimilated themselves into local communities. Many of these soldiers provided assistance to rebel forces during the Indonesian National Revolution.[78][79]

The final stages of warfare were initiated in October 1945 when, in accordance with the terms of their surrender, the Japanese tried to re-establish the authority they relinquished to Indonesians in the towns and cities. Japanese military police killed Republican pemuda in Pekalongan (Central Java) on 3 October, and Japanese troops drove Republican pemuda out of Bandung in West Java and handed the city to the British, but the fiercest fighting involving the Japanese was in Semarang. On 14 October, British forces began to occupy the city. Retreating Republican forces retaliated by killing between 130 and 300 Japanese prisoners they were holding. Five hundred Japanese and 2000 Indonesians had been killed and the Japanese had almost captured the city six days later when British forces arrived.[80]

I, of course, knew that we had been forced to keep Japanese troops under arms to protect our lines of communication and vital areas ... but it was nevertheless a great shock to me to find over a thousand Japanese troops guarding the nine miles of road from the airport to the town.[81]

— Lord Mountbatten of Burma in April 1946 after visiting Sumatra, referring to the use of Japanese Surrendered Personnel.

Until 1949, the returning Dutch authorities held 448 war crimes trials against 1038 suspects. 969 of those were condemned (93.4%) with 236 (24.4%) receiving a death sentence.[82]

See also

References

- ^ Klemen, L. (1999–2000). "The conquer of Borneo Island, 1941–1942". Dutch East Indies Campaign website.

- ^ a b Ricklefs 1991, p. 199.

- ^ Friend, p. 29.

- ^ Vickers, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b Vickers, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Mayumi Yamamoto, "Spell of the Rebel, Monumental Apprehensions: Japanese Discourses On Pieter Erberveld," Indonesia 77 (April 2004):124–127.

- ^ Vickers (2005), p. 86

- ^ Vickers, p. 83.

- ^ Bidien, Charles (5 December 1945). "Independence the Issue". Far Eastern Survey. 14 (24): 345–348. doi:10.1525/as.1945.14.24.01p17062. ISSN 0362-8949. JSTOR 3023219.

- ^ "The Kingdom of the Netherlands Declares War with Japan". ibiblio. 15 December 1941. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ^ Klemen, L. (1999–2000). "General Sir Archibald Percival Wavell". Dutch East Indies Campaign website.

- ^ Taylor (2003), pp. 310–311

- ^ a b c Vickers (2005), p. 87

- ^ Horton, William Bradley (2007). "Ethnic Cleavage in Timorese Society: The Black Columns in Occupied Portuguese Timor (1942)". 国際開発学研究. 6 (2).

- ^ Klemen, L. (1999–2000). "The Java Sea Battle". Dutch East Indies Campaign website.

- ^ Klemen, L. (1999–2000). "The conquest of Java Island, March 1942". Dutch East Indies Campaign website.

- ^ a b Taylor (2003), p 310

- ^ Womack, Tom; The Dutch Naval Air Force against Japan: the defense of the Netherlands East Indies, 1941–1942, McFarland: 2006, ISBN 978-0-7864-2365-1, 207 pages: pp. 194–196 google books reference: [1]

- ^ Pramoedya Ananta Toer, The Mute's Soliloquy, trans. Willem Samuels (New York: Penguin, 1998), pp. 74–106 (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1975). Cited in Vickers, p. 85.

- ^ Cribb & Brown, p. 13.

- ^ VIcker (2005), p. 87

- ^ Taylor (2003), p. 311

- ^ Library of Congress, 1992, "Indonesia: World War II and the Struggle For Independence, 1942–50; The Japanese Occupation, 1942–45" Access date: 9 February 2007.

- ^ a b c Vickers, p. 85.

- ^ Ricklefs 1993, p. 207.

- ^ Cited in: Dower, John W. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986; Pantheon; ISBN 978-0-394-75172-6)

- ^ Ministerie van Buitenlandse zaken 1994, pp. 6–9, 11, 13–14

- ^ http://www.awf.or.jp/e1/netherlands.html

- ^ Soh, Chunghee Sarah. "Japan's 'Comfort Women'". International Institute for Asian Studies. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Soh, Chunghee Sarah (2008). The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan. University of Chicago Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-226-76777-2.

- ^ "Women made to become comfort women - Netherlands". Asian Women's Fund.

- ^ Poelgeest. Bart van, 1993, Gedwongen prostitutie van Nederlandse vrouwen in voormalig Nederlands-Indië 's-Gravenhage: Sdu Uitgeverij Plantijnstraat. [Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 93-1994, 23 607, nr. 1.]

- ^ Poelgeest, Bart van. "Report of a study of Dutch government documents on the forced prostitution of Dutch women in the Dutch East Indies during the Japanese occupation." [Unofficial Translation, 24 January 1994.]

- ^ Reid, Anthony (1973). The Indonesian National Revolution 1945–1950. Melbourne: Longman Pty. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-582-71046-7.

- ^ Davidson 2002, p. 78.

- ^ a b Ricklefs 2001, p. 252.

- ^ Federspiel 2007, p. 124.

- ^ Buyers, Christopher (January 2002 – January 2013). "SERDANG". The Royal Ark. Christopher Buyers.

- ^ Heidhues 2003, p. 204.

- ^ Ooi 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Heidhues 2003, p. 205.

- ^ ed. Kratoska 2013, p. 160.

- ^ Davidson 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Davidson 2003, p. 9.

- ^ ed. Kratoska 2002, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Ooi 2013.

- ^ Ooi 2013, p. 176.

- ^ Zweers 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Vries 2010.

- ^ ed. Kratoska 2013, p. 168.

- ^ Heidhues 2003, p. 207.

- ^ Felton 2007, p. 86.

- ^ Davidson 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Heidhues 2003, p. 206.

- ^ Davidson 2003, p. 8.

- ^ ed. Kratoska 2013, p. 165.

- ^ Hui 2011, p. 42.

- ^ Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Netherlands). Afdeling Documentatie Modern Indonesie 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Baldacchino 2013, p. 75.

- ^ Sai & Hoon 2013, p. 119.

- ^ Martinkus 2004, p. 47.

- ^ "Tempo: Indonesia's Weekly News Magazine, Volume 3, Issues 43-52" 2003, p. 27.

- ^ http://www.atjehcyber.net/2011/08/sejarah-jejak-perlawanan-aceh.html

- ^ Pepatah Lama Di Aceh Utara

- ^ Pepatah Lama Di Aceh Utara

- ^ "Berita Kadjian Sumatera: Sumatra Research Bulletin, Volumes 1-4" 1971, p. 35.

- ^ Nasution 1963, p. 89.

- ^ "Sedjarah Iahirnja Tentara Nasional Indonesia" 1970, p. 12.

- ^ "20 [i. e Dua puluh] tahun Indonesia merdeka, Volume 7", p. 547.

- ^ "Sedjarah TNI-Angkatan Darat, 1945–1965. [Tjet. 1.]" 1965, p. 8.

- ^ "20 tahun Indonesia merdeka, Volume 7", p. 545.

- ^ Atjeh Post, Minggu Ke III September 1990. halaman I & Atjeh Post, Minggu Ke IV September 1990 halaman I

- ^ Jong 2000, p. 189.

- ^ Template:De icon Dahm, Bernhard: Sukarnos Kampf um Indonesiens Unabhängigkeit. Werdegang und Ideen eines asiatischen Nationalisten. (Publisher: Metzner, Frankfurt am Main, 1966. First published as Master thesis, University of Manheim, Kiel, 1964). p. 201–204

- ^ Friend, p. 33.

- ^ Cited in: Dower, John W. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986; Pantheon; ISBN 0-394-75172-8).

- ^ Van der Eng, Pierre (2008) 'Food Supply in Java during War and Decolonisation, 1940–1950.' MPRA Paper No. 8852. pp. 35–38. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/8852/

- ^ Tjandraningsih, Christine, (Kyodo News), "Japanese recounts role fighting to free Indonesia", Japan Times, 9 September 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Tjandraningsih, Christine T., "Indonesians to get book on Japanese freedom fighter", Japan Times, 19 August 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Ricklefs 1991, p. 216.

- ^ "Japanese Prisoners of War" By Philip Towle, Margaret Kosuge, Yōichi Kibata. p. 146 (Google.Books)

- ^ Piccigallo, Philip; The Japanese on Trial; Austin 1979; ISBN 978-0-292-78033-0 (Kap. "The Netherlands")

References

- Baldacchino, Godfrey, ed. (2013). The Political Economy of Divided Islands: Unified Geographies, Multiple Polities. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-137-02313-9. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Cribb, Robert; Brown, Colin (1995). Modern Indonesia: A History Since 1945. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman Group. ISBN 978-0-582-05713-5.

- Davidson, Jamie Seth (2002). Violence and Politics in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. University of Washington. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Davidson, Jamie S. (August 2003). ""Primitive" Politics: The Rise and Fall of the Dayak Unity Party in West Kalimantan, Indonesia"" (PDF). Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series (ARI Working Paper) (No. 9). Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

{{cite journal}}:|number=has extra text (help) - Davidson, Jamie Seth (2009). From Rebellion to Riots: Collective Violence on Indonesian Borneo. NUS Press. ISBN 9971-69-427-1. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Federspiel, Howard M. (2007). Sultans, Shamans, and Saints: Islam and Muslims in Southeast Asia (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-3052-0. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Friend, Theodore (2003). Indonesian Destinies. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01834-1.

- Heidhues, Mary F. Somers (2003). Golddiggers, Farmers, and Traders in the "Chinese Districts" of West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Vol. Volume 34 of Southeast Asia publications series (illustrated ed.). SEAP Publications. ISBN 0-87727-733-8. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Hui, Yew-Foong (2011). Strangers at Home: History and Subjectivity Among the Chinese Communities of West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Vol. Volume 5 of Chinese Overseas (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 90-04-17340-4. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Indonesia. Angkatan Darat. Pusat Sedjarah Militer (1965). Sedjarah TNI-Angkatan Darat, 1945–1965. [Tjet. 1.]. PUSSEMAD. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Indonesia. Panitia Penjusun Naskah Buku "20 Tahun Indonesia Merdeka.", Indonesia. 20 [i. e Dua puluh] tahun Indonesia merdeka, Volume 7. Departement Penerangan. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Indonesia. Departemen Penerangan. 20 tahun Indonesia merdeka, Volume 7. Departemen Penerangan R.I. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Jong, Louis (2002). The collapse of a colonial society: the Dutch in Indonesia during the Second World War. Vol. Volume 206 of Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Nederlands Geologisch Mijnbouwkundig Genootschap, Volume 206 of Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (illustrated ed.). KITLV Press. ISBN 90-6718-203-6. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Excerpta Indonesica, Volumes 64-66. Contributor Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Netherlands). Afdeling Documentatie Modern Indonesie. Centre for Documentation on Modern Indonesia of the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology. 2001. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Kratoska, Paul H., ed. (2002). Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire. Psychology Press. ISBN 0-7007-1488-X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kratoska, Paul H., ed. (2013). Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire. Routledge. ISBN 1-136-12506-X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Martinkus, John (2004). Indonesia's Secret War in Aceh (illustrated ed.). Random House Australia. ISBN 1-74051-209-X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Abdul Haris Nasution (1963). Tentara Nasional Indonesia, Volume 1. Ganaco. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Keat Gin, Ooi (2013). Post-War Borneo, 1945–1950: Nationalism, Empire and State-Building. Routledge. ISBN 1-134-05810-1. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2013). Post-war Borneo, 1945–50: Nationalism, Empire and State-Building. Routledge. ISBN 1-134-05803-9. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Post, Peter; et al. eds. (2010). The Encyclopedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16866-4.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - Sai, Siew-Min; Hoon, Chang-Yau, eds. (2013). Chinese Indonesians Reassessed: History, Religion and Belonging. Vol. Volume 52 of Routledge contemporary Southeast Asia series (illustrated ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-60801-5. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (2001). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1200 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4480-7. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300 (Second ed.). MacMillan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300 (Second ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8047-2194-3. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- Vickers, Adrain (2005). A History Modern of Indonesia. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-54262-3.

- Tempo: Indonesia's Weekly News Magazine, Volume 3, Issues 43-52. Arsa Raya Perdana. 2003. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Berita Kadjian Sumatera: Sumatra Research Bulletin, Volumes 1-4. Contributors Sumatra Research Council (Hull, England), University of Hull Centre for South-East Asian Studies. Dewan Penjelidikan Sumatera. 1971. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Sedjarah Iahirnja Tentara Nasional Indonesia. Contributor Indonesia. Angkatan Darat. Komando Daerah Militer II Bukit Barisan. Sejarah Militer. Sedjarah Militer Dam II/BB. 1970. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Further reading

- Anderson, Ben (1972). Java in a Time of Revolution: Occupation and Resistance, 1944–1946. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-0687-4.

- Hillen, Ernest (1993). The Way of a Boy: A Memoir of Java. Toronto: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-85049-5.

External links

Media related to Japanese occupation of Indonesia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Japanese occupation of Indonesia at Wikimedia Commons