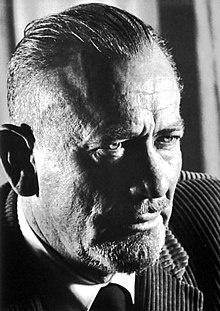

John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck | |

|---|---|

Steinbeck in Sweden during his trip to accept the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962 | |

| Born | John Ernst Steinbeck, Jr. February 27, 1902 Salinas, California, U.S. |

| Died | December 20, 1968 (aged 66) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, war correspondent |

| Notable works | Of Mice and Men (1937) The Grapes of Wrath (1939) East of Eden (1952)[1] |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (1940) Nobel Prize in Literature (1962) |

| Spouses |

Carol Henning

(m. 1930; div. 1943)Gwyn Conger

(m. 1943; div. 1948)Elaine Scott

(m. 1950) |

| Children | John Steinbeck IV (1946–1991) Thomas Steinbeck (1944–2016) |

| Signature | |

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (/ˈstaɪnbɛk/; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American author. He won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception."[2] He has been called "a giant of American letters," and many of his works are considered classics of Western literature.[3]

During his writing career, he authored 27 books, including 16 novels, six non-fiction books, and two collections of short stories. He is widely known for the comic novels Tortilla Flat (1935) and Cannery Row (1945), the multi-generation epic East of Eden (1952), and the novellas Of Mice and Men (1937) and The Red Pony (1937). The Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath (1939)[4] is considered Steinbeck's masterpiece and part of the American literary canon.[5] In the first 75 years after it was published, it sold 14 million copies.[6]

Most of Steinbeck's work is set in central California, particularly in the Salinas Valley and the California Coast Ranges region. His works frequently explored the themes of fate and injustice, especially as applied to downtrodden or everyman protagonists.

Early life

Steinbeck was born on February 27, 1902, in Salinas, California.[7] He was of German, English, and Irish descent.[8] Johann Adolf Großsteinbeck (1828–1913), Steinbeck's paternal grandfather, shortened the family name to Steinbeck when he immigrated to the United States. The family farm in Heiligenhaus, Mettmann, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, is still named "Großsteinbeck."

His father, John Ernst Steinbeck (1862–1935), served as Monterey County treasurer. John's mother, Olive Hamilton (1867–1934), a former school teacher, shared Steinbeck's passion for reading and writing.[9] The Steinbecks were members of the Episcopal Church,[10] although Steinbeck later became agnostic.[11] Steinbeck lived in a small rural town, no more than a frontier settlement, set in some of the world's most fertile land.[12] He spent his summers working on nearby ranches and later with migrant workers on Spreckels sugar beet farms. There he learned of the harsher aspects of the migrant life and the darker side of human nature, which supplied him with material expressed in such works as Of Mice and Men.[12] He explored his surroundings, walking across local forests, fields, and farms.[12] While working at Spreckels Sugar Company, he sometimes worked in their laboratory, which gave him time to write.[13] He had considerable mechanical aptitude and fondness for repairing things he owned.[13]

Steinbeck graduated from Salinas High School in 1919 and went on to study English Literature at Stanford University near Palo Alto, leaving without a degree in 1925. He traveled to New York City where he took odd jobs while trying to write. When he failed to publish his work, he returned to California and worked in 1928 as a tour guide and caretaker[13] at Lake Tahoe, where he met Carol Henning, his first wife.[9][13][14] They married in January 1930 in Los Angeles, where, with friends, he attempted to make money by manufacturing plaster mannequins.[13]

When their money ran out six months later due to a slow market, Steinbeck and Carol moved back to Pacific Grove, California, to a cottage owned by his father, on the Monterey Peninsula a few blocks outside the Monterey city limits. The elder Steinbecks gave John free housing, paper for his manuscripts, and from 1928, loans that allowed him to write without looking for work. During the Great Depression, Steinbeck bought a small boat, and later claimed that he was able to live on the fish and crab that he gathered from the sea, and fresh vegetables from his garden and local farms. When those sources failed, Steinbeck and his wife accepted welfare, and on rare occasions, stole bacon from the local produce market.[13] Whatever food they had, they shared with their friends.[13] Carol became the model for Mary Talbot in Steinbeck's novel Cannery Row.[13]

In 1930, Steinbeck met the marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who became a close friend and mentor to Steinbeck during the following decade, teaching him a great deal about philosophy and biology.[13] Ricketts, usually very quiet, yet likable, with an inner self-sufficiency and an encyclopedic knowledge of diverse subjects, became a focus of Steinbeck's attention. Ricketts had taken a college class from Warder Clyde Allee, a biologist and ecological theorist, who would go on to write a classic early textbook on ecology. Ricketts became a proponent of ecological thinking, in which man was only one part of a great chain of being, caught in a web of life too large for him to control or understand.[13] Meanwhile, Ricketts operated a biological lab on the coast of Monterey, selling biological samples of small animals, fish, rays, starfish, turtles, and other marine forms to schools and colleges.

Between 1930 and 1936, Steinbeck and Ricketts became close friends. Steinbeck's wife began working at the lab as secretary-bookkeeper.[13] Steinbeck helped on an informal basis.[15] They formed a common bond based on their love of music and art, and John learned biology and Ricketts' ecological philosophy.[16] When Steinbeck became emotionally upset, Ricketts sometimes played music for him.[17]

Career

Writing

Steinbeck's first novel, Cup of Gold, published in 1929, is loosely based on the life and death of privateer Henry Morgan. It centers on Morgan's assault and sacking of the city of Panama, sometimes referred to as the 'Cup of Gold', and on the women, fairer than the sun, who were said to be found there.[18]

Between 1930 and 1933, Steinbeck produced three shorter works. The Pastures of Heaven, published in 1932, consists of twelve interconnected stories about a valley near Monterey, which was discovered by a Spanish corporal while chasing runaway Indian slaves. In 1933 Steinbeck published The Red Pony, a 100-page, four-chapter story weaving in memories of Steinbeck's childhood.[18] To a God Unknown, named after a Vedic hymn,[13] follows the life of a homesteader and his family in California, depicting a character with a primal and pagan worship of the land he works. Although he had not achieved the status of a well-known writer, he never doubted that he would achieve greatness.[13]

Steinbeck achieved his first critical success with Tortilla Flat (1935), a novel set in post-war Monterey, California, that won the California Commonwealth Club's Gold Medal.[18] It portrays the adventures of a group of classless and usually homeless young men in Monterey after World War I, just before U.S. prohibition. They are portrayed in ironic comparison to mythic knights on a quest and reject nearly all the standard mores of American society in enjoyment of a dissolute life devoted to wine, lust, camaraderie and petty theft. In presenting the 1962 Nobel Prize to Steinbeck, the Swedish Academy cited "spicy and comic tales about a gang of paisanos, asocial individuals who, in their wild revels, are almost caricatures of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table. It has been said that in the United States this book came as a welcome antidote to the gloom of the then prevailing depression."[1] Tortilla Flat was adapted as a 1942 film of the same name, starring Spencer Tracy, Hedy Lamarr and John Garfield, a friend of Steinbeck. With some of the proceeds, he built a summer ranch-home in Los Gatos.[citation needed]

Steinbeck began to write a series of "California novels" and Dust Bowl fiction, set among common people during the Great Depression. These included In Dubious Battle, Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath. He also wrote an article series called The Harvest Gypsies for the San Francisco News about the plight of the migrant worker.

Of Mice and Men was a drama about the dreams of two migrant agricultural laborers in California. It was critically acclaimed[18] and Steinbeck's 1962 Nobel Prize citation called it a "little masterpiece".[1] Its stage production was a hit, starring Wallace Ford as George and Broderick Crawford as George's companion, the mentally childlike, but physically powerful itinerant farmhand Lennie. Steinbeck refused to travel from his home in California to attend any performance of the play during its New York run, telling director George S. Kaufman that the play as it existed in his own mind was "perfect" and that anything presented on stage would only be a disappointment. Steinbeck wrote two more stage plays (The Moon Is Down and Burning Bright).

Of Mice and Men was also adapted as a 1939 Hollywood film, with Lon Chaney, Jr. as Lennie (he had filled the role in the Los Angeles stage production) and Burgess Meredith as George.[19] Meredith and Steinbeck became close friends for the next two decades.[13] Another film based on the novella was made in 1992 starring Gary Sinise as George and John Malkovich as Lennie.

Steinbeck followed this wave of success with The Grapes of Wrath (1939), based on newspaper articles about migrant agricultural workers that he had written in San Francisco. It is commonly considered his greatest work. According to The New York Times, it was the best-selling book of 1939 and 430,000 copies had been printed by February 1940. In that month, it won the National Book Award, favorite fiction book of 1939, voted by members of the American Booksellers Association.[20] Later that year, it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction[21] and was adapted as a film directed by John Ford, starring Henry Fonda as Tom Joad; Fonda was nominated for the best actor Academy Award. Grapes was controversial. Steinbeck's New Deal political views, negative portrayal of aspects of capitalism, and sympathy for the plight of workers, led to a backlash against the author, especially close to home.[22] Claiming the book was both obscene and misrepresented conditions in the county, the Kern County Board of Supervisors banned the book from the county's publicly funded schools and libraries in August 1939. This ban lasted until January 1941.[23]

Of the controversy, Steinbeck wrote, "The vilification of me out here from the large landowners and bankers is pretty bad. The latest is a rumor started by them that the Okies hate me and have threatened to kill me for lying about them. I'm frightened at the rolling might of this damned thing. It is completely out of hand; I mean a kind of hysteria about the book is growing that is not healthy."[24]

The film versions of The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men (by two different movie studios) were in production simultaneously, allowing Steinbeck to spend a full day on the set of The Grapes of Wrath and the next day on the set of Of Mice and Men.[citation needed]

Ed Ricketts

In the 1930s and 1940s, Ed Ricketts strongly influenced Steinbeck's writing. Steinbeck frequently took small trips with Ricketts along the California coast to give himself time off from his writing[25] and to collect biological specimens, which Ricketts sold for a living. Their joint book about a collecting expedition to the Gulf of California in 1940, which was part travelogue and part natural history, published just as the U.S. entered World War II, never found an audience and did not sell well.[25] However, in 1951, Steinbeck republished the narrative portion of the book as The Log from the Sea of Cortez, under his name only (though Ricketts had written some of it). This work remains in print today.[26]

Although Carol accompanied Steinbeck on the trip, their marriage was beginning to suffer, and ended a year later, in 1941, even as Steinbeck worked on the manuscript for the book.[13] In 1942, after his divorce from Carol he married Gwyndolyn "Gwyn" Conger.[27] With his second wife Steinbeck had two sons, Thomas ("Thom") Myles Steinbeck (1944–2016) and John Steinbeck IV (1946–1991).

Ricketts was Steinbeck's model for the character of "Doc" in Cannery Row (1945) and Sweet Thursday (1954), "Friend Ed" in Burning Bright, and characters in In Dubious Battle (1936) and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Ecological themes recur in Steinbeck's novels of the period.[28]

Steinbeck's close relations with Ricketts ended in 1941 when Steinbeck moved away from Pacific Grove and divorced his wife Carol.[25] Ricketts' biographer Eric Enno Tamm notes that, except for East of Eden (1952), Steinbeck's writing declined after Ricketts' untimely death in 1948.[28]

1940s–1960s work

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

Steinbeck's novel The Moon Is Down (1942), about the Socrates-inspired spirit of resistance in an occupied village in Northern Europe, was made into a film almost immediately. It was presumed that the unnamed country of the novel was Norway and the occupiers the Nazis. In 1945, Steinbeck received the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross for his literary contributions to the Norwegian resistance movement.

In 1943, Steinbeck served as a World War II war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune and worked with the Office of Strategic Services (predecessor of the CIA).[29] It was at that time he became friends with Will Lang, Jr. of Time/Life magazine. During the war, Steinbeck accompanied the commando raids of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.'s Beach Jumpers program, which launched small-unit diversion operations against German-held islands in the Mediterranean. At one point, he accompanied Fairbanks on an invasion of an island off the coast of Italy and helped capture Italian and German prisoners, using a Tommy Gun. Some of his writings from this period were incorporated in the documentary Once There Was a War (1958).

Steinbeck returned from the war with a number of wounds from shrapnel and some psychological trauma. He treated himself, as ever, by writing. He wrote Alfred Hitchcock's movie, Lifeboat (1944), and the film, A Medal for Benny (1945), with screenwriter Jack Wagner about paisanos from Tortilla Flat going to war. He later requested that his name be removed from the credits of Lifeboat, because he believed the final version of the film had racist undertones. In 1944, suffering from homesickness for his Pacific Grove/Monterey life of the 1930s, he wrote Cannery Row (1945), which became so famous that in 1958 Ocean View Avenue in Monterey, the location of the book, was renamed Cannery Row.

After the war, he wrote The Pearl (1947), knowing it would be filmed eventually. The story first appeared in the December 1945 issue of Woman's Home Companion magazine as "The Pearl of the World." It was illustrated by John Alan Maxwell. The novel is an imaginative telling of a story which Steinbeck had heard in La Paz in 1940, as related in The Log From the Sea of Cortez, which he described in Chapter 11 as being "so much like a parable that it almost can't be". Steinbeck traveled to Mexico for the filming with Wagner who helped with the script; on this trip he would be inspired by the story of Emiliano Zapata, and subsequently wrote a film script (Viva Zapata!) directed by Elia Kazan and starring Marlon Brando and Anthony Quinn.

In 1947, Steinbeck made the first of many[quantify] trips to the Soviet Union, this one with photographer Robert Capa. They visited Moscow, Kiev, Tbilisi, Batumi and Stalingrad, some of the first Americans to visit many parts of the USSR since the communist revolution. Steinbeck's 1948 book about their experiences, A Russian Journal, was illustrated with Capa's photos. In 1948, the year the book was published, Steinbeck was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

In 1952 Steinbeck's longest novel, East of Eden, was published. According to his third wife, Elaine, he considered it his magnum opus, his greatest novel.

In 1952, John Steinbeck appeared as the on-screen narrator of 20th Century Fox's film, O. Henry's Full House. Although Steinbeck later admitted he was uncomfortable before the camera, he provided interesting introductions to several filmed adaptations of short stories by the legendary writer O. Henry. About the same time, Steinbeck recorded readings of several of his short stories for Columbia Records; the recordings provide a record of Steinbeck's deep, resonant voice.

Following the success of Viva Zapata!, Steinbeck collaborated with Kazan on East of Eden, James Dean's film debut.

Travels with Charley: In Search of America is a travelogue of his 1960 road trip with his poodle Charley. Steinbeck bemoans his lost youth and roots, while dispensing both criticism and praise for America. According to Steinbeck's son Thom, Steinbeck made the journey because he knew he was dying and wanted to see the country one last time.[30]

Steinbeck's last novel, The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), examines moral decline in America. The protagonist Ethan grows discontented with his own moral decline and that of those around him.[31] The book has a very different tone from Steinbeck's amoral and ecological stance in earlier works like Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row. It was not a critical success. Many reviewers recognized the importance of the novel, but were disappointed that it was not another Grapes of Wrath.[31] In the Nobel Prize presentation speech next year, however, the Swedish Academy cited it most favorably: "Here he attained the same standard which he set in The Grapes of Wrath. Again he holds his position as an independent expounder of the truth with an unbiased instinct for what is genuinely American, be it good or bad."[1]

Apparently taken aback by the critical reception of this novel, and the critical outcry when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962,[32] Steinbeck published no more fiction in the next six years before his death.

Nobel Prize

In 1962, Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature for his "realistic and imaginative writing, combining as it does sympathetic humor and keen social perception." The selection was heavily criticized, and described as "one of the Academy's biggest mistakes" in one Swedish newspaper.[32] The reaction of American literary critics was also harsh. The New York Times asked why the Nobel committee gave the award to an author whose "limited talent is, in his best books, watered down by tenth-rate philosophising", noting that "[T]he international character of the award and the weight attached to it raise questions about the mechanics of selection and how close the Nobel committee is to the main currents of American writing. ... [W]e think it interesting that the laurel was not awarded to a writer ... whose significance, influence and sheer body of work had already made a more profound impression on the literature of our age".[32] Steinbeck, when asked on the day of the announcement if he deserved the Nobel, replied: "Frankly, no."[13][32] Biographer Jackson Benson notes, "[T]his honor was one of the few in the world that one could not buy nor gain by political maneuver. It was precisely because the committee made its judgment ... on its own criteria, rather than plugging into 'the main currents of American writing' as defined by the critical establishment, that the award had value."[13][32] In his acceptance speech later in the year in Stockholm, he said:

the writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man's proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit—for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion and love. In the endless war against weakness and despair, these are the bright rally flags of hope and of emulation. I hold that a writer who does not believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature.

— Steinbeck Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech[33]

In 2012, (50 years later), the Nobel Prize opened its archives and it was revealed that Steinbeck was a "compromise choice" among a shortlist consisting of Steinbeck, British authors Robert Graves and Lawrence Durrell, French dramatist Jean Anouilh and Danish author Karen Blixen.[32] The declassified documents showed that he was chosen as the best of a bad lot.[32] "There aren't any obvious candidates for the Nobel prize and the prize committee is in an unenviable situation," wrote committee member Henry Olsson.[32] Although the committee believed Steinbeck's best work was behind him by 1962, committee member Anders Österling believed the release of his novel The Winter of Our Discontent showed that "after some signs of slowing down in recent years, [Steinbeck has] regained his position as a social truth-teller [and is an] authentic realist fully equal to his predecessors Sinclair Lewis and Ernest Hemingway."[32]

Although modest about his own talent as a writer, Steinbeck talked openly of his own admiration of certain writers. In 1953, he wrote that he considered cartoonist Al Capp, creator of the satirical Li'l Abner, "possibly the best writer in the world today."[34] At his own first Nobel Prize press conference he was asked his favorite authors and works and replied: "Hemingway's short stories and nearly everything Faulkner wrote."[13]

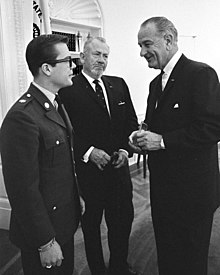

In September 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded Steinbeck Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 1967, at the behest of Newsday magazine, Steinbeck went to Vietnam to report on the war. He thought of the Vietnam War as a heroic venture and was considered a hawk for his position on the war. His sons served in Vietnam before his death, and Steinbeck visited one son in the battlefield. At one point he was allowed to man a machine-gun watch position at night at a firebase while his son and other members of his platoon slept.[35]

Personal life

In May 1948, Steinbeck returned to California on an emergency trip to be with his friend Ed Ricketts, who had been seriously injured when a train struck his car. Ricketts died hours before Steinbeck arrived. Upon returning home, Steinbeck was confronted by Gwyn, who asked for a divorce, which became final in August. Steinbeck spent the year after Ricketts' death in deep depression.

In June 1949, Steinbeck met stage-manager Elaine Scott at a restaurant in Carmel, California. Steinbeck and Scott eventually began a relationship and in December 1950 Steinbeck and Scott married, within a week of the finalizing of Scott's own divorce from actor Zachary Scott. This third marriage for Steinbeck lasted until his death in 1968.[18]

In 1962, Steinbeck began acting as friend and mentor to the young writer and naturalist Jack Rudloe, who was trying to establish his own biological supply company, now Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory in Florida. Their correspondence continued until Steinbeck's death.[36]

In 1966, Steinbeck traveled to Tel Aviv to visit the site of Mount Hope, a farm community established in Israel by his grandfather, whose brother, Friedrich Großsteinbeck, was murdered by Arab marauders in 1858 in what became known as the Outrages at Jaffa.[37]

Death and legacy

John Steinbeck died in New York City on December 20, 1968, of heart disease and congestive heart failure. He was 66, and had been a lifelong smoker. An autopsy showed nearly complete occlusion of the main coronary arteries.[18]

In accordance with his wishes, his body was cremated, and interred on March 4, 1969[38] at the Hamilton family gravesite in Salinas, with those of his parents and maternal grandparents. His third wife, Elaine, was buried in the plot in 2004. He had written to his doctor that he felt deeply "in his flesh" that he would not survive his physical death, and that the biological end of his life was the final end to it.[25]

The day after Steinbeck's death in New York City, reviewer Charles Poore wrote in The New York Times: "John Steinbeck's first great book was his last great book. But Good Lord, what a book that was and is: The Grapes of Wrath." Poore noted a "preachiness" in Steinbeck's work, "as if half his literary inheritance came from the best of Mark Twain— and the other half from the worst of Cotton Mather." But he asserted that "Steinbeck didn't need the Nobel Prize— the Nobel judges needed him."

Steinbeck's incomplete novel based on the King Arthur legends of Malory and others, The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights, was published in 1976.

Many of Steinbeck's works are required reading in American high schools. In the United Kingdom, Of Mice and Men is one of the key texts used by the examining body AQA for its English Literature GCSE. A study by the Center for the Learning and Teaching of Literature in the United States found that Of Mice and Men was one of the ten most frequently read books in public high schools.[39] Contra-wise, Steinbeck's works have been frequently banned in the United States. The Grapes of Wrath was banned by school boards: in August 1939, Kern County Board of Supervisors banned the book from the county's publicly funded schools and libraries.[23] It was burned in Salinas on two different occasions.[40][41] In 2003, a school board in Mississippi banned it on the grounds of profanity.[42] According to the American Library Association Steinbeck was one of the ten most frequently banned authors from 1990 to 2004, with Of Mice and Men ranking sixth out of 100 such books in the United States.[43][44]

Opinions on Nobel Prize

The award of the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature to Steinbeck was controversial in the United States. The award citation lauded Steinbeck "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception". Many critics complained that the author's best works were behind him. The New York Times ran an article by Arthur Mizener titled "Does a Writer with a Moral Vision of the 1930s Deserve the Nobel Prize?" that claimed Steinbeck was undeserving of the prestigious prize as he was a "limited talent" whose works were "watered down by tenth-rate philosophizing". Many American critics now consider these attacks to be politically motivated.[45]

The British newspaper The Guardian, in a 2013 article that revealed that Steinbeck had been a compromise choice for the Nobel Prize, called him a "Giant of American Letters". Despite ongoing attacks on his literary reputation, Steinbeck's works continue to sell well and he is widely taught in American and British schools as a bridge to more complex literature. Works such as Of Mice and Men are short and easy to read, and compassionately illustrate universal themes that are still relevant in the 21st century.[3]

Literary influences

Steinbeck grew up in California's Salinas Valley, a culturally diverse place with a rich migratory and immigrant history. This upbringing imparted a regionalistic flavor to his writing, giving many of his works a distinct sense of place.[12][18] Salinas, Monterey and parts of the San Joaquin Valley were the setting for many of his stories. The area is now sometimes referred to as "Steinbeck Country".[25] Most of his early work dealt with subjects familiar to him from his formative years. An exception was his first novel, Cup of Gold, which concerns the pirate Henry Morgan, whose adventures had captured Steinbeck's imagination as a child.

In his subsequent novels, Steinbeck found a more authentic voice by drawing upon direct memories of his life in California. His childhood friend, Max Wagner, a brother of Jack Wagner and who later became a film actor, served as inspiration for The Red Pony. Later he used actual American conditions and events in the first half of the 20th century, which he had experienced first-hand as a reporter. Steinbeck often populated his stories with struggling characters; his works examined the lives of the working class and migrant workers during the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression.

His later work reflected his wide range of interests, including marine biology, politics, religion, history and mythology. One of his last published works was Travels with Charley, a travelogue of a road trip he took in 1960 to rediscover America.

Commemoration

Steinbeck's boyhood home, a turreted Victorian building in downtown Salinas, has been preserved and restored by the Valley Guild, a nonprofit organization. Fixed menu lunches are served Monday through Saturday, and the house is open for tours on Sunday afternoons during the summer.[46]

The National Steinbeck Center, two blocks away at 1 Main Street is the only museum in the U.S. dedicated to a single author. Dana Gioia (chair of the National Endowment for the Arts) told an audience at the center, "This is really the best modern literary shrine in the country, and I've seen them all." Its "Steinbeckiana" includes "Rocinante", the camper-truck in which Steinbeck made the cross-country trip described in Travels with Charley.

His father's cottage on Eleventh Street in Pacific Grove, where Steinbeck wrote some of his earliest books, also survives.[25]

In Monterey, Ed Ricketts' laboratory survives (though it is not yet open to the public) and at the corner which Steinbeck describes in Cannery Row, also the store which once belonged to Lee Chong, and the adjacent vacant lot frequented by the hobos of Cannery Row. The site of the Hovden Sardine Cannery next to Doc's laboratory is now occupied by the Monterey Bay Aquarium. In 1958 the street that Steinbeck described as "Cannery Row" in the novel, once named Ocean View Avenue, was renamed Cannery Row in honor of the novel. The town of Monterey has commemorated Steinbeck's work with an avenue of flags depicting characters from Cannery Row, historical plaques, and sculptured busts depicting Steinbeck and Ricketts.[25]

On February 27, 1979 (the 77th anniversary of the writer's birth), the United States Postal Service issued a stamp featuring Steinbeck, starting the Postal Service's Literary Arts series honoring American writers.[47]

On December 5, 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Steinbeck into the California Hall of Fame, located at the California Museum for History, Women and the Arts.[48] His son, author Thomas Steinbeck, accepted the award on his behalf.

To commemorate the 112th anniversary of Mr. Steinbeck's birthday on February 27, 2014, Google displayed an interactive doodle utilizing animation which included illustrations portraying scenes and quotes from several novels by the author.[49][50][51]

Steinbeck and his friend Ed Ricketts appear as a fictionalized characters in the 2016 novel, Monterey Bay about the founding of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, by Lindsay Hatton (Penguin Press).[52]

Religious views

Steinbeck was affiliated to the St. Paul's Episcopal Church and he stayed attached throughout his life to Episcopalianism. Especially in his works of fiction, Steinbeck was highly conscious of religion and incorporated it into his style and themes. The shaping of his characters often drew on the Bible and the theology of Anglicanism, combining elements of Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

Steinbeck distanced himself from religious views when he left Salinas for Stanford. However, the work he produced still reflected the language of his childhood at Salinas, and his beliefs remained a powerful influence within his fiction and non-fiction work. His Episcopal views are prominently displayed in The Grapes of Wrath, in which themes of conversion and self-sacrifice play a major part in the characters Casy and Tom who achieve spiritual transcendence through conversion.[53]

Political views

Steinbeck's contacts with leftist authors, journalists, and labor union figures may have influenced his writing. He joined the League of American Writers, a Communist organization, in 1935.[54] Steinbeck was mentored by radical writers Lincoln Steffens and his wife Ella Winter. Through Francis Whitaker, a member of the Communist Party USA's John Reed Club for writers, Steinbeck met with strike organizers from the Cannery and Agricultural Workers' Industrial Union.[55] In 1939, he signed a letter with some other writers in support of the Soviet invasion of Finland and the Soviet-established puppet government.[56]

Documents, released by the Central Intelligence Agency in 2012, indicate that Steinbeck offered his services to the Agency in 1952, while planning a European tour, and the Director of Central Intelligence, Walter Bedell Smith, was eager to take him up on the offer.[57] What work, if any, Steinbeck may have performed for the CIA during the Cold War is unknown.

Steinbeck was a close associate of playwright Arthur Miller. In June 1957, Steinbeck took a personal and professional risk by supporting him when Miller refused to name names in the House Un-American Activities Committee trials.[40] Steinbeck called the period one of the "strangest and most frightening times a government and people have ever faced."[40]

In 1967, when he was sent to Vietnam to report on the war, his sympathetic portrayal of the United States Army led the New York Post to denounce him for betraying his liberal past. Steinbeck's biographer, Jay Parini, says Steinbeck's friendship with President Lyndon B. Johnson influenced his views on Vietnam.[18] Steinbeck may also have been concerned about the safety of his son serving in Vietnam.[58]

Government harassment

Steinbeck complained publicly about government harassment. Thomas Steinbeck, the author's eldest son, said that J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI at the time, could find no basis for prosecuting Steinbeck and therefore used his power to encourage the U.S. Internal Revenue Service to audit Steinbeck's taxes every single year of his life, just to annoy him. According to Thomas, a true artist is one who "without a thought for self, stands up against the stones of condemnation, and speaks for those who are given no real voice in the halls of justice, or the halls of government. By doing so, these people will naturally become the enemies of the political status quo."[59]

In a 1942 letter to United States Attorney General Francis Biddle, John Steinbeck wrote: "Do you suppose you could ask Edgar's boys to stop stepping on my heels? They think I am an enemy alien. It is getting tiresome."[60] The FBI denied that Steinbeck was under investigation.

Major works

In Dubious Battle

In 1936, Steinbeck published the first of what came to be known as his Dustbowl trilogy, which included Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath. This first novel tells the story of a fruit pickers' strike in California which is both aided and damaged by the help of "the Party," generally taken to be the Communist Party, although this is never spelled out in the book.

Of Mice and Men

Of Mice and Men is a tragedy that was written as a play in 1937. The story is about two traveling ranch workers, George and Lennie, trying to earn enough money to buy their own farm/ranch. As it is set in 1930s America, it provides an insight into The Great Depression, encompassing themes of racism, loneliness, prejudice against the mentally ill, and the struggle for personal independence. Along with The Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden, and The Pearl, Of Mice and Men is one of Steinbeck's best known works. It was made into a movie three times, in 1939 starring Burgess Meredith, Lon Chaney Jr., and Betty Field, in 1982 starring Randy Quaid, Robert Blake and Ted Neeley, and in 1992 starring Gary Sinise and John Malkovich.

The Grapes of Wrath

The Grapes of Wrath is set in the Great Depression and describes a family of sharecroppers, the Joads, who were driven from their land due to the dust storms of the Dust Bowl. The title is a reference to the Battle Hymn of the Republic. Some critics found it too sympathetic to the workers' plight and too critical of capitalism, but found a large audience of its own. It won both the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize for fiction (novels) and was adapted as a film starring Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell and directed by John Ford.

East of Eden

Steinbeck deals with the nature of good and evil in this Salinas Valley saga. The story follows two families: the Hamiltons – based on Steinbeck's own maternal ancestry[61] – and the Trasks, reprising stories about the Biblical Adam and his progeny. The book was published in 1952. It was made into a 1955 movie directed by Elia Kazan and starring James Dean.

Travels with Charley

In 1960, Steinbeck bought a pickup truck and had it modified with a custom-built camper top – which was rare at the time – and drove across the United States with his faithful 'blue' standard poodle, Charley. Steinbeck nicknamed his truck Rocinante after Don Quixote's "noble steed". In this sometimes comical, sometimes melancholic book, Steinbeck describes what he sees from Maine to Montana to California, and from there to Texas and Louisiana and back to his home on Long Island. The restored camper truck is on exhibit in the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas.

Bibliography

Filmography

- 1939—Of Mice and Men—directed by Lewis Milestone, featuring Burgess Meredith, Lon Chaney, Jr., and Betty Field

- 1940—The Grapes of Wrath—directed by John Ford, featuring Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell and John Carradine

- 1941—The Forgotten Village—directed by Alexander Hammid and Herbert Kline, narrated by Burgess Meredith, music by Hanns Eisler

- 1942—Tortilla Flat—directed by Victor Fleming, featuring Spencer Tracy, Hedy Lamarr and John Garfield

- 1943—The Moon is Down—directed by Irving Pichel, featuring Lee J. Cobb and Sir Cedric Hardwicke

- 1944—Lifeboat—directed by Alfred Hitchcock, featuring Tallulah Bankhead, Hume Cronyn, and John Hodiak

- 1944—A Medal for Benny—directed by Irving Pichel, featuring Dorothy Lamour and Arturo de Cordova

- 1947—La Perla (The Pearl, Mexico)—directed by Emilio Fernández, featuring Pedro Armendáriz and María Elena Marqués

- 1949—The Red Pony—directed by Lewis Milestone, featuring Myrna Loy, Robert Mitchum, and Louis Calhern

- 1952—Viva Zapata!—directed by Elia Kazan, featuring Marlon Brando, Anthony Quinn and Jean Peters

- 1955—East of Eden—directed by Elia Kazan, featuring James Dean, Julie Harris, Jo Van Fleet, and Raymond Massey

- 1957—The Wayward Bus—directed by Victor Vicas, featuring Rick Jason, Jayne Mansfield, and Joan Collins

- 1961—Flight—featuring Efrain Ramírez and Arnelia Cortez

- 1962—Ikimize bir dünya (Of Mice and Men, Turkey)

- 1972—Topoli (Of Mice and Men, Iran)

- 1982—Cannery Row—directed by David S. Ward, featuring Nick Nolte and Debra Winger

- 1992—Of Mice and Men—directed by Gary Sinise and starring John Malkovich and Gary Sinise

- 2016—In Dubious Battle—directed by James Franco and featuring Franco, Nat Wolff and Selena Gomez

See also

- Pigasus – A personal stamp used by Steinbeck.

Notes

- ^ a b c d

The Swedish Academy cited The Grapes of Wrath and The Winter of Our Discontent most favorably.

"The Nobel Prize in Literature 1962: Presentation Speech by Anders Österling, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2008.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nobel Prize in Literature 1962". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Who, what, why: Why do children study Of Mice and Men?". BBC. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Novel". The Pulitzer Prizes. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bryer, R. Jackson (1989). Sixteen Modern American Authors, Volume 2. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 620. ISBN 978-0822310181.

- ^ Chilton, Martin. "The Grapes of Wrath: 10 surprising facts about John Steinbeck's novel". Telegraph (London). Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "John Steinbeck Biography". Biography.com website. A&E Television Networks. February 6, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Okie Faces & Irish Eyes: John Steinbeck & Route 66". Irish America. Archived from the original on November 21, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "John Steinbeck Biography". Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). National Steinbeck Centre - ^ Alec Gilmore. John Steinbeck's View of God Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. gilco.org.uk

- ^ Jackson J. Benson (1984). The true adventures of John Steinbeck, writer: a biography. Viking Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-670-16685-5.

Ricketts did not convert his friend to a religious point of view—Steinbeck remained an agnostic and, essentially, a materialist—but Ricketts's religious acceptance did tend to work on his friend, ...

- ^ a b c d Introduction to John Steinbeck, The Long Valley, pp. 9–10, John Timmerman, Penguin Publishing, 1995

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Jackson J. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer New York: The Viking Press, 1984. ISBN 0-14-014417-X, pp. 147, 915a, 915b, 133

- ^ Introduction to 'The Grapes of Wrath' Penguin edition (1192) by Robert DeMott

- ^ Jackson J. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer New York: The Viking Press, 1984. ISBN 0-14-014417-X, p. 196

- ^ Jackson J. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer New York: The Viking Press, 1984. ISBN 0-14-014417-X, p. 197

- ^ Jackson J. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer New York: The Viking Press, 1984. ISBN 0-14-014417-X, p. 199

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jay Parini, John Steinbeck: A Biography, Holt Publishing, 1996

- ^ "Of Mice and Men (1939)". The Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "1939 Book Awards Given by Critics: Elgin Groseclose's 'Ararat' is Picked as Work Which Failed to Get Due Recognition", The New York Times, February 14, 1940, p. 25. ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851–2007).

- ^ "Novel" Archived August 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (Winners 1917–1947). The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ Keith Windschuttle (June 2, 2002). ""Steinbeck's myth of the Okies"". Archived from the original on February 4, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). The New Criterion. - ^ a b "Steinbecks works banned". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved June 4, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). pacific.net.au - ^ Steiner, Bernd (November 2007). A Survey on John Steinbeck's "The Grapes of Wrath". GRIN Verlag. p. 6. ISBN 9783638844598. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Susan Shillinglaw (2006). "A Journey into Steinbeck's California". Roaring Forties Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ A website devoted to Sea of Cortez literature, with information on Steinbeck's expedition. Archived July 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Fensch, Thomas (2002). Steinbeck and Covici. New Century exceptional lives. New Century Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-930751-35-7.

- ^ a b Bruce Robison, "Mavericks on Cannery Row," American Scientist, vol. 92, no. 6 (November–December 2004), p. 1: a review of Eric Enno Tamm, Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell Archived June 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Four Walls Eight Windows, 2004.

- ^ Introduction to The Moon Is Down (Penguin) published 1995, by Donald V. Coers

- ^ Steinbeck knew he was dying Archived September 27, 2007, at archive.today," September 13, 2006. Audio interview with Thom Steinbeck

- ^ a b Cynthia Burkhead, The students companion to John Steinbeck, Greenwood Press, 2002, p. 24 ISBN 0-313-31457-8

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Alison Flood (January 3, 2013). "Swedish Academy reopens controversy surrounding Steinbeck's Nobel prize". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steinbeck Nobel Prize Banquet Speech Archived January 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Nobelprize.org (December 10, 1962). Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ "ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Archive: Biography: Al Capp 2- A CAPPital Offense". Archived from the original on March 24, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). animationarchive.org (May 2008). - ^ Steinbeck, A Life in Letters.

- ^ T. Manning, Matos S., Addler B. "Hidden Treasure The Steinbeck-Rudloe Letters" Archived September 29, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Steinbeck Studies, San Jose University, 2005 Vol 16, No 1&2, pg 109–117

- ^ Perry, Yaron."John Steinbeck's Roots in Nineteenth-Century Palestine." Archived February 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Steinbeck Studies 15.1 (Spring 2004): 46–72. www.muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved on August 26, 2011.

- ^ Burial in timeline at this site, taken from '''Steinbeck: A Life in Letters'''. Steinbeck.org. Retrieved on August 26, 2011.

- ^ Books taught in Schools Archived October 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Center for the Learning and Teaching of Literature. Retrieved 2007.

- ^ a b c Jackson J. Benson, John Steinbeck, Writer: A Biography, Penguin, 1990 ISBN 0-14-014417-X

- ^ The Grapes of Wrath Burnt in Salinas Archived October 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, National Steinbeck Centre. Retrieved 2007.

- ^ Steinbecks work banned in Mississippi 2003 Archived October 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, American Library Association. Retrieved 2007.

- ^ "Steinbeck 10 most banned list". Archived from the original on July 15, 2004. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help), American Library Association. - ^ "100 Most Frequently banned books in the U.S." Archived from the original on March 23, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help), American Library Association. Retrieved 2007. - ^ Johnson, Eric. "John Steinbeck, despised and dismissed by the right and the left, was a real American radical". Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ "John Steinbeck's Home and Birthplace". Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help), Information Point. Retrieved 2007. - ^ "Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author Gets 'Stamp of Approval'". United States Postal Service. February 21, 2008. Archived from the original on March 26, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steinbeck inducted into California Hall of Fame Archived October 8, 2011, at WebCite, California Museum. Retrieved 2007.

- ^ Laura Stampler (February 27, 2014). "Google Doodle Celebrates John Steinbeck". Time Inc. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alison Flood (February 27, 2014). "John Steinbeck: Google Doodle pays tribute to author on 112th anniversary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Carolyn Kellogg (February 27, 2014). "Google Doodle celebrates the work of John Steinbeck". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ray, W. "John Steinbeck, Episcopalian: St. Paul's, Salinas, Part One." Steinbeck Review, vol. 10 no. 2, 2013, pp. 118–140. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/530751.

- ^ Dave Stancliff (February 24, 2013). "Remembering John Steinbeck, a great American writer". Times-Standard. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ Steinbeck and radicalism Archived February 4, 2004, at the Wayback Machine New Criterion. Retrieved 2007.

- ^ "Terijoen hallitus sai outoa tukea" [The Terijoki Government received odd support]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). November 29, 2009.

- ^ Brian Kannard, Steinbeck: Citizen Spy, Grave Distractions, 2013 ISBN 978-0-9890293-9-1, pp. 15–17. The correspondence is also available at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Gladstein, Mimi R.; Meredith, James H. (June 14, 2011). "John Steinbeck and the Tragedy of the Vietnam War". Steinbeck Review. 8 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6087.2011.01137.x. ISSN 1546-007X.

- ^ Huffington Post, September 27, 2010, John Steinbeck, Michael Moore, and the Burgeoning Role of Planetary Patriotism Archived September 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Steinbeck Political Beliefs Archived October 22, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Smoking Gun Part 1. Retrieved 2007.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (February 24, 2002). "In Steinbeck Country". Archived from the original on September 22, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

References

- DeMott, Robert and Steinbeck, Elaine A., eds. John Steinbeck, Novels and Stories 1932–1937 (Library of America, 1994) ISBN 978-1-883011-01-7

- DeMott, Robert and Steinbeck, Elaine A., eds. John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath and Other Writings 1936–1941 (Library of America, 1996) ISBN 978-1-883011-15-4

- DeMott, Robert, ed. John Steinbeck, Novels 1942–1952 (Library of America, 2002) ISBN 978-1-931082-07-5

- DeMott, Robert and Railsback, Brian, eds. John Steinbeck, Travels With Charlie and later novels, 1947–1962 (Library of America, 2007) ISBN 978-1-59853-004-9

- Benson, Jackson J. (ed.) The Short Novels Of John Steinbeck: Critical Essays with a Checklist to Steinbeck Criticism. Durham: Duke UP, 1990 ISBN 0-8223-0994-7.

- Davis, Robert C. The Grapes of Wrath: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1982. PS3537 .T3234 G734

- French, Warren. John Steinbeck's Fiction Revisited. NY: Twayne, 1994 ISBN 0-8057-4017-1.

- Hughes, R. S. John Steinbeck: A Study of the Short Fiction. R.S. Hughes. Boston : Twayne, 1989. ISBN 0-8057-8302-4.

- Meyer, Michael J. The Hayashi Steinbeck Bibliography, 1982–1996. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1998 ISBN 0-8108-3482-0.

- Benson, Jackson J. Looking for Steinbeck's Ghost. Reno: U of Nevada P, 2002 ISBN 0-87417-497-X.

- Ditsky, John. John Steinbeck and the Critics. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2000 ISBN 1-57113-210-4.

- Heavilin, Barbara A. John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath: A Reference Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002 ISBN 0-313-31837-9.

- Li, Luchen. ed. John Steinbeck: A Documentary Volume. Detroit: Gale, 2005 ISBN 0-7876-8127-X.

- Steinbeck, John Steinbeck IV and Nancy (2001). The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-858-5

- Tamm, Eric Enno (2005). Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-689-2.

- Bensen, Jackson J. "John Steinbeck, Writer" Penguin Putnam Inc., second edition, New York, 1990, 0-14-01.4417X,

External links

- National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California

- at Ball State University Archives and Special Collections

- The Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at the San José State University

- searchable database of secondary Steinbeck materials

- Nathaniel Benchley (Fall 1969). "John Steinbeck, The Art of Fiction No. 45". The Paris Review.

- George Plimpton and Frank Crowther (Fall 1975). "John Steinbeck, The Art of Fiction No. 45 (Continued)". The Paris Review.

- "Writings of John Steinbeck" from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- FBI file on John Steinbeck

- Template:Worldcat id

- Nobel Laureate page

- John Steinbeck Collection, 1902–1979 (call number M0263; 8.50 linear ft.) and Wells Fargo John Steinbeck Collection, 1870–1981 (call number M1063; 5 linear ft.) are housed in the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Stanford University Libraries

- The Steinbeck Quarterly journal, a full-text searchable journal published from 1968–1993 by the John Steinbeck Society of America that focuses on Steinbeck criticism and scholarship

- John Steinbeck at Library of Congress, with 359 library catalog records

- John Steinbeck Biography Early Years: Salinas to Stanford: 1902–1925 from National Steinbeck Center

- Western American Literature Journal: John Steinbeck

- John Steinbeck

- 1902 births

- 1968 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- American agnostics

- American Episcopalians

- American male novelists

- American male short story writers

- American Nobel laureates

- American people of English descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American travel writers

- National Book Award winners

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- People from Salinas, California

- People of the New Deal arts projects

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners

- Recipients of the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross

- Stanford University alumni

- Writers from California

- DeMolay International Hall of Fame members

- American male non-fiction writers