Kobold

A kobold (occasionally cobold) is a mythical sprite in German folklore.

Earliest attestation from medieval writings (13th century) indicate it was a doll carved from wood or made of wax, and it is speculated these were fetish figurines, or carvings of household spirits, set up in the house, likely mounted upon the fireplace mantel or the hearth.

The practice may have descended from an ancient Germanic house or a hearth god (Old High German: hûsing, herdgota), analogous to the ancient Roman lares or lar (hearth goddess) worshiped as figurines, or the penas (sing. of penates).[2][5][6] The Eastern slang gütel or güttel ("little god"; possibly equivalent to götze, or "idol") perhaps should by added as another kobold synonym, and may support the view of this sort of use.

What is clear is that these kobold dolls were puppets used in plays and by travelling showmen, based on 13th century writings. They were also known as tatrmann and described as manipulated by wires. Either way, the idol or puppet was invoked rhetorically in writing by the minstrels, etc. to mock clergymen or other people.[8]

The kobold in the general sense of "house spirit" is known by various other names. Kobold subtypes called hütchen or Low German hödekin come from their wearing caps or hoods. It has been stated by Jacob Grimm that the kobold has the general tendency to wear red pointy hats, while acknowledging this to be a widely disseminated mark of European household spirits under other names such as the Norwegian nisse; and the North or Northeastern German Niss or Puk (cog. puck) which are also prone to wearing such caps.

The kobold subtypes katrmann and hintzelmann suggest their occasional cat-form. The similar sounding Heinzelmann or Heinzelmännchen (cf. § Heinzelmann) has been explained to be a distinguishable, separate being by recent scholarship. But the kobold is also known by other pet names such as Chimke (diminutive of Joachim) and Woltken. As household spirits, they may perform domestic chores, or play malicious tricks if insulted or neglected. The kobold can also materialize in the form of other animals, a human, or a pillar of fire.

Tales of the vengeful kitchen spirit are quite old. Allegedly some time after c. 1130, the Hödekin (=Hütchen) of Hildesheim (or Winzenburg Castle occupied by the bishop) dismembered a kitchen scullion for splashing him with slop water (see fig. right), recorded in a chronicle c. 1500. Similarly, the Chimmeken of Mecklenburg Castle, in 1327, dismembered a kitchen boy into pieces for stealing the milk offered to it, as attested by Thomas Kantzow, d. 1542.

The original notion of the kobold as household spirit, seemingly corroborated by the etymology kob[en] "chamber" + walt "ruler, power, authority" was corrupted by the idea of mine spirits by the 16th century, when mine spirits were known among German mine-workers as kobel (Latin: cobalus) or [a] (see gnome). Grimm had argued for an alternate etymology for kobold, as deriving from this Latin cobalus, making kobold a cognate of cobalus (kobel) and "goblin".[b] Older literature spoke of stetewalden ("ruler of the place") which may be a precursor.

The name of the element cobalt comes from the creature's name, because medieval miners blamed the sprite for the poisonous and troublesome nature of the typical arsenical ores of this metal (cobaltite and smaltite) which polluted other mined elements.

The Klabautermann aboard ships are sometimes classed as a kobold.

Nomenclature

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The kobalt etymology as consisting of kob "chamber" + walt "ruler, power, authority", with the meaning of "household spirit" has been advanced and given by various authors, e.g., Müller-Fraureuth (1906).[9] Otto Schrader (1908) suggested ancestral *kuba-walda "the one who rules the house".[10] Dowden (2002) offers the hypothetical precursor *kofewalt.[11]

Older etymons and cognates

[edit]The kob/kub/kuf- root is possibly related to Old Norse/Icelandic: kofe "chamber",[9][12] or Old High German: chubisi "house".[12] and the English word "cove" in the sense of 'shelter".[9]

Müller-Fraureuth (1906) wrote that the form kobe survives in modern German "Schweinekoben",[9] meaning "pig stall", and that the true original etymology contained the stem -Hold as a name for "demon".[9][14]

Related cognate terms occur in Dutch, such as kabout, kabot, and kaboutermanneken.[15]

Transitive as mine spirit

[edit]German linguist Paul Kretschmer (1928) recapped the foregoing etymology of kobold stating that the word kobold derived from koben "chamber' + walt "ruler, power, authority", but this original sense of Hausgeist underwent a meaning-shift, through assimilation or conflation with lore about "mine spirits" (cf. § Transitive as mine spirit). Hence the term "kobold" were sometimes susceptible to being interchangeably used with various terms for "mine spirits", such as the Latin forms of Bergmännlein[c] or gnome or Berggeist.[16]

Grimm's alternate etymology

[edit]Although Grimm himself conjectured that the boxwood kobold dolls mentioned in 13th century literature derived from carven idols of household spirits (cf. § Doll or idol below),[2] he did not advance the aforementioned "house-ruler" etymology, but rather saw kobold/kobolt as deriving from Latin cobalus or its antecedent Greek koba'los (pl. kobaloi; Ancient Greek: Κόβαλος, plural: Κόβαλοι), meaning "rogue".[d] The final -olt he explained as typical German language suffix for monsters and supernaturals.[4]

Thus the generic "goblin"[4] is a cognate of "kobold" according to Grimm's etymology, and perhaps even a descendant word deriving from "kobold".[11][18]

- (Mine spirits)

Additionally, Grimm's etymology for kobold is shared by the cobalus mine spirits (later known as gnomes) described by Georgius Agricola (De Animantibus Subterraneis, 1549), who connected the word to the Greek kobalos.[19][17][20][22]

The term cobalus denoting mine spirits or demons according to Georg Agricola answers to German kobel.[21][23]

- (kobalos in Hellenism)

The kobalos of ancient Greece which was a sprite, a mischievous creature fond of tricking and frightening mortals, even robbing Heracles/Hercules. Greek myths depict the kobaloi as impudent, thieving, droll, idle, mischievous, gnome-dwarfs, and as funny, little tricksy elves of a phallic nature. Depictions of kobaloi are common in ancient Greek art.[24][better source needed]

Cobalt ore

[edit]The cobalt ore was already known as kobalt among German miners in the 16th century, attested by Johannes Mathesius, and supposedly was thus called in reference to the mine demon.[20][25]

Subtypes, other house spirits

[edit]Although kobold has slipped into becoming a generic term, translatable as goblin, so that all manners of household spirits become classifiable as "types" of kobold. Such alternate names for the kobold house sprite are classified by type of naming (A. As doll, B. As pejoratives for stupidity, C. Appearance-based, D. Characteristics-based, E. Diminutive pet name based), etc., in the Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens (HdA).[g][7]

A geographical map of Germany labeled with the different regional appellations has appeared in a 2020 publication.[26]

Grimm, after stating that the list of kobold (or household spirit) in German lore can be long, also adds the names Hütchen and Heinzelmann.[53]

Doll or puppet names

[edit]The term kobold in its earliest usage suggest it to be a wooden doll (Cf. §Origins under § Doll or idol below). A synonym for kobold in that sense includes Tatrmann, which is also attested in the medieval period.[54]

The household spirit names poppele and butz were thought by Grimm to derive from noise-making,[55] but the HdA considers them to be doll names. The poppele is close to German Puppe for doll; the term Butz could refer to a "tree trunk".[7]

More recently, the East Central German name gütel or güttel (diminutive of "god") has been suggested as a kobold synonym of the fetish figurine type.[7] Grimm knew the term but placed the discussion of it under the "Wild man of the woods" section[56] conjecturing the use of güttel as synonymous to götze (i.e., sense of 'idol') in medieval heroic legend[57][58] The term gütel answers to Agricola's naming the guteli (in Latin) as akin to his mine spirit.[17][27]

Pet names

[edit]Though the Heinzelmännchen[h] (diminutive of Heinrich) is a "pet name" type of appellation and applied to the kobold according to Grimm,[61] this is incorrect according to modern linguist Elmar Seebold, who asserts that only the Hinzelmann/Hintzelmann (Cf. § Cat-shape) is properly associated with kobold, and the Heinzelmännchen is completely distinguishable in terms of both appearance and behavior.[25][62]

Chimke (var. Chimken, Chimmeken), diminutive of Joachim is a Niederdeutsch for a poltergeist; the story of "Chimmeken" dates to c. 1327 and recorded in Thomas Kantzow's Pomeranian chronicle (cf. § Offerings and retributions).[41][63] Chimgen (Kurd Chimgen[66]), and Chim are other forms[67][68][69][71]

Wolterken, also Low German, is diminutive for Walther, and another piece of household spirit of the pet name type, Wolterken glossed as "lares" and attested together with "chimken" and "hußnißken" in Samuel Meiger (1587) Panurgia lamiarum.[72][73][74][i][7]

- (mandrake root dolls)

In the south, Heinzelmännchen confusingly carries the different meaning of mandrake root (German: Alraun, Alraunwurzel).[25] The mandrake-doll is regarded as falling under the class of Glückmännchen, the generic term for dolls fashioned from roots, in some sources.[75][77] In the north (Saterland, Lower Saxony) there is an instance of the kobold being called alrûne, and the name also occurs in Friesland.[78][j]

Apparel names

[edit]Under the classification of household spirit names based on appearance, a subcategory collects names based on apparel, especially the hat (classification C. a), under which are listed Hütchen, Timpehut, Langhut, etc. and even Hellekeplein (from the term for cloak of invisibility).[7] To this group probably belongs the Lower Saxon house spirit hôdekin (Low German: Hödekin) from Hildesheim, sporting a felt hat (Latin: pileus).[k][85][86][87] Grimm also adds the names Hopfenhütel, Eisenhütel.[88]

Cat-shape

[edit]The kobold type Hinzelmann or Hintzelmann[36] is completely distinguishable from Heinzelmann, Heinzelmännchen according to modern scholarship,[25] (cf. § Heinzelmann) and is classified as a name alluding to the kobold's cat-like shape or transformation, according to the HdA.[7] The analysis is expounded upon by Jacob Grimm, who notes that Hinze was the name of the cat in the Reineke (German version of Reynard the Fox) so it was the common pet name for cats. Thus hinzelman, hinzemännchen are recognized as cat-based names, as well as katermann (from kater "tom cat") which may be precursor to tatermann.[89].[90][7]

The katzen-veit named after a cat is categorized by Grimm as a "wood sprite", but also discussed under kobold,[91] and classed as a "cat appearance" type kobold name (category C b) in HdA.[7] Grimm localized the katzen-veit at Fichtelberg in the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains),[90] and Prateorius also recognized this as the lore of the Vogtland region,[92] though Praetorius's work published (1692) under the pseudonym Lustigero Wortlibio claims katzen-veit to be a famous "cabbage spirit" in the Hartzewalde (in Elbingerode, now part of Oberharz am Brocken in the Harz mountains, cf. map).[92]

The kobold appears in the guise of a cat to eat the panada bribe, in Saintine's version.[93]

Poltergeists

[edit]The HdA&lsquot;s category D consists of kobold names from their behavioural characteristics, and other than some non-German sprites discussed, these are mainly the poltergeists, or noise-making spirits and names after their favourite dish.[7] The poltergeists include the klopfer ("knocker"),[39][31] hämmerlein[94], etc.[7][96]

Milk-lovers

[edit]In category D, there are names deriving from their favorite food being the bowl of milk, namely napfhans ("Potjack")[31]and the Swiss beckli meaning "milk vat".[7]

Invisibility

[edit]Although King Goldemar (or Goldmar), a famous kobold from Castle Hardenstein, had hands "thin like those of a frog, cold and soft to the feel", he never showed himself.[97] The master of Hudemühlen Castle, where Heinzelmann lived, convinced the kobold to let him touch him one night. When a man threw ashes and tares about to try to see King Goldemar's footprints, the kobold cut him to pieces, put him on a spit, roasted him, boiled his legs and head, and ate him.[98]

Miscellaneous

[edit]King Goldemar, king of dwarfs, is also rediscussed under the household spirit commentary by Grimm, presumably because he became a guest to the human king Neveling von Hardenberg at his Castle Hardenstein for three years,[99] making a dwarf sort of a household spirit on a limited-term basis.

For cognate beings of kobolds or house spirits in non-German cultures, see § Parallels.

Origins

[edit]One proposed precursor to the kobold house spirit may be the stetewalden[7] mentioned by Frater Rudolfus of the 13th century,[100] meaning "ruler of the site" (genius loci).[26][101]

Doll or idol

[edit]One of the earliest attestations of kobold comes Konrad von Würzburg's poem (<1250) which refers to a man as worthless as a kobold (doll made from from boxwood).[54]

Grimm conjectured (and Karl Simrock in 1855 reiterated) that home sprites carved from boxwood and wax and set up in the house, originally as a cult of the German hearth god (Old High German: hûsing or herdgota),[5] equivalent to Roman penates or (lar familiares), manes,[102] which are hearth deities.[6] Otto Schrader also regurgitated this idea, observing that "cult of the hearth-fire" developed into "tutlelary house deities, localized in the home", and the German kobold and the Greek agathós daímōn fit this template.[105][107][dubious – discuss]

The 17th century expression to laugh like a kobold may refer to these dolls with their mouths wide open, and it may mean "to laugh loud and heartily".[108]

Although Grimm supposes these were once seriously venerated as idols, even by this already Catholicized period (High Middle Ages), people were using them as decors in jest, like the modern nutcracker dolls, and the practice has endured in this playful context into modern times.[109]

Thomas Keightley comments that legends and folklore about kobolds can be explained as "ventriloquism and the contrivances of servants and others".[110]

Stringed puppet

[edit]The kobolt and Tatrmann were also boxwood puppets manipulated by wires, which performed in puppet theater in the medieval period.[60][111] The traveling juggler (German: Gaukler) of yore used to make a kobold doll appear out of their coats, and make faces with it to entertain the crowd.[112][60]

Metaphoric slander

[edit]Whether doll or marionette, the terms were kobold and synonyms were used in literature to satirize the clergy as "wooden bishop", or "wooden sexton".[6] This is sometimes comparing a man in silence to a mute doll.[113][115] T

Some of the kobold synonyms are specific classified under the slander for stupidity category in the HdA, as aforementioned.[7]

But Konrad's poem above seems to be a more complicated double metaphor to the luhs (Luchs, "lynx", conceived of as a hybrid of fox and wolf, and therefore unable to breed) deriding someone as reproductively sterile and deceitful, just like a kobold doll.[116]

Characteristics

[edit]

Kobolds are spirits and, as such, part of a spiritual realm. However, as with other European spirits, they often dwell among the living.[117][118]

Kobolds may manifest as non-human animals, fire, humans, and objects.[117],such as a candle[citation needed].

Physical description

[edit]The kobold household spirit tends to be ascribed red hair and beard, according to Jacob Grimm.[119][l] One report of a encounter experience with mine kobolds claims black skin (cf. § A spiritualist's report).[120]

Red cap

[edit]Kobolds supposedly also tend to wear a pointy red hat, though Grimm acknowledges that the "red peaky cap" is also the mark of the Norwegian nisse.[119] Grimm mentions the spirit known as hütchen (meaning "little hat" of felt,[85] cf. § Apparel names) immediately after, perhaps as an example of such a cap-wearer.

The kobold wearing a red cap and protective pair of boots is reiterated by, e.g., Wolfgang Golther.[121] Grimm describes household spirits owning fairy shoes or fairy boots, which permits rapid travel over difficult terrain, and compares it to the league boots of fairytale.[122]

There is lore concerning the infant-sized niss-puk (Niß Puk, Nisspuk var. Neß Puk, where Puk is cognate to English puck) wearing (pointed) red caps localized in various part of the province of Schleswig-Holstein, in northernmost Germany adjoining Denmark.[123][124][f]

Karl Müllenhoff provided the "kobold" lore of the Schwertmann of Schleswig-Holstein,[127] in his collection of Schleswig-Holstein legends, this tale localized at Rethwisch, Steinburg (Krempermarsch).[128] The Schwertmann was said to dwell in a Donnerloch or granite-hole,[m] The being perpetrates mischief to villagers, but can also (try to) be helpful, may appear in the guise of fire, and appreciates the gift of shoes, though his burning feet quickly turns them into tatters.[128][n] According to supposed eyewitness accounts by people in Stapelholm the Niß Puk[o] was no larger than a 1 or 1 1/2 year old infant (some say 3-year old)[p] and had a "large head and long arms, and small but bright cunning eyes",[q] and wore "red stockings and a long grey or green tick coat..[and] red, peaked cap".[r][43][130]

The lore of the house kobold puk[s] was also current farther east in Pomerania, including now Polish Farther Pomerania.[131] The kobold-niss-puk was regarded as wearing a "red jacket and cap" in western Uckermark.[132] The tale of pûks told in Swinemünde (now Świnoujście)[t] held that a man's luck ran out when he rebuilt his house and the blessing passed on to his neighbor who reused the old beams. The pûks was witnessed wearing a cocked hat (aufgekrämpten Hut), red jacket with shiny buttons.[133]

Boyish spirit

[edit]Other tales describe kobolds appearing as herdsmen looking for work[134] and little, wrinkled old men in pointed hoods.[135] Some kobolds resemble small children.

There also seems to be a piece of lore that the kobolds are the spirits of dead children and often appear with a knife that represents the means by which they were put to death.[137][138][139]

Fire phenomena

[edit]The kobold is said to appear as an oscillating fire-pillar ("stripe") with a part resembling a head, but appears in the guise of a black cat when it lands and is no longer airborne (Altmark, Saxony.[50] Benjamin Thorpe likens this to similar lore about the dråk ("drake") in Swinemünde (now Świnoujście), Pomerania.[50][u]

A legend from the same period taken from Pechüle, near Luckenwald, says that a drak or kobold flies through the air as a blue stripe and carries grain. "If a knife or a fire-steel be cast at him, he will burst, and must let fall what which he is carrying".[132] Some legends say the fiery kobold enters and exits a house through the chimney.[141] Legends dating to 1852 from western Uckermark ascribe both human and fiery features to the kobold; he wears a red jacket and cap and moves about the air as a fiery stripe.[132] Such fire associations, along with the name drake, may point to a connection between kobold and dragon myths.[141]

Animal form

[edit]Other kobolds appear as non-human animals.[117] Folklorist D. L. Ashliman has reported kobolds appearing as wet cats and hens.[134] In Pomerania there are several tales specimens that a kobold or puk hatches from a yolk-less chicken egg (Spâei, Sparei),[47][144] and in other tales, a kobold (aka "redjacket") appears in a cat's guise[145] or a puk appears as a hen.[146][147]

Thorpe has recorded that the people of Altmark believed that kobolds appeared as black cats while walking the earth.[148] The kobold Heinzelmann could appear as a black marten and a large snake.[149]

House spirits

[edit]

Domestic kobolds are linked to a specific household.[150] Some legends claim that every house has a resident kobold, regardless of its owners' desires or needs.[151] The means by which a kobold enters a new home vary from tale to tale.

Should someone take pity on a kobold in the form of a cold, wet creature and take it inside to warm it, the spirit takes up residence there.[134] A tradition from Perleberg in northern Germany says that a homeowner must follow specific instructions to lure a kobold to their house. They must go on St John's Day between noon and one o'clock, into the forest. When they find an anthill with a bird on it, they must say a certain phrase, which causes the bird to transform into a small human. The figure then leaps into a bag carried by the homeowner, and they can then transfer the kobold to their home.[152] Even if servants come and go, the kobold stays.[150]

House kobolds usually live in the hearth area of a house,[135] although some tales place them in less frequented parts of the home, in the woodhouse,[153] in barns and stables, or in the beer cellar of an inn. At night, such kobolds do chores that the human occupants neglected to finish before bedtime:[135] They chase away pests, clean the stables, feed and groom the cattle and horses, scrub the dishes and pots, and sweep the kitchen.[136][154] Other kobolds help tradespeople and shopkeepers.

Invisibility and true form

[edit]The normal invisibility of the Chimgen (or Chim) kobold is explained in legend which tells of a female servant taking a fancy to her house's kobold and asking to see him. The kobold refuses, claiming that to look upon him would be terrifying. Undeterred, the maid insists, and the kobold tells her to meet him later—and to bring along a pail of cold water. The kobold waits for the maid, nude and with a butcher knife in his back. The maid faints at the sight, and the kobold wakes her with the cold water. And she never wished to see the Chimgen[66] ever again.[155][156]

In one variant, the maid urges her favourite kobold named Heinzchen to see him in his natural state, and is then led to the cellar, where she is shown a dead baby floating in a cask full of blood; years before, the woman had borne a bastard child, killed it, and hidden it in such a cask.[157][158]

Offerings and retributions

[edit]A kobold expects to be fed in the same place at the same time each day.[136]

Legends tell of slighted kobolds becoming quite malevolent and vengeful,[135][136] afflicting errant hosts with supernatural diseases, disfigurements, and injuries.[159] Their pranks range from beating the servants to murdering those who insult them.[160][161]

In the story of the Chimmeken of the Mecklenburg Castle, (supra, dated 1327 given by Kantzow) the milk customarily put for the sprite by the kitchen was stolen by a kitchen-boy (Küchenbube), and the spirit consequently left the boy's dismembered body in a kettle of hot water.[41][163][164] In comparison, a more amicable pück anecdotally served monks at Mecklenburg monastery, bargaining for multicolored tunic with lots of bells in return for his services.[166]

A similar story of the vengeful Hüdeken[85] (var. Hütgin[v]) occurs in a chronicle of Hildesheim, c. 1500.[168][169][171][173][175] A preceding tale where Hüdeken serves as messenger in the events of c. 1132 explains the historical background.[176] The Hüdeken (also Hödekin) was avenged the kitchen boy who splashed filthy water[180] by strangled the lad in his sleep and leaving the torn-apart body parts cooking in a pot over the fire. When the head cook who complained about the prank, the Hüdeken squeezed venomous toad blood onto the meat being prepared for the bishop. Later he led the cook to an illusory bridge plunging him into the moat.[183][184][186][187] Some versions add that the Bishop in the end used the power of his spells (Beschwörung) to get rid of the Hödeken.[189]

According to Max Lüthi, the household spirits' being ascribed such abilities reflect the fear of the people who believe in them.[159]

The bribe left to the household spirit, other than milk may be panada (bread [and milk] soup) in a supposed Alsatian version.[70] Novelist Heinrich Heine noted in connection with the present (Hildesheim) tale that the favourite food was the gruel for the Scandinavian nisse.[190]

As a sort of the reverse of the offering, one tradition claims that the kobold will strew wood chips about the house and putting dirt or cow manure in the milk cans. And if the master of the house leaves the wood chips and drinks the soiled milk, the kobold is pleased and takes up residence at the household[191][192]

Good-evil duality

[edit]Archibald Maclaren has attributed kobold behaviour to the virtue of the homeowners; a virtuous house has a productive and helpful kobold; a vice-filled one has a malicious and mischievous pest. If the hosts give up those things to which the kobold objects, the spirit ceases its annoying behaviour.[193] Hinzelmann punished vices; for example, when the secretary of Hudemühlen was sleeping with the chamber maid, the kobold interrupted a sexual encounter and hit the secretary with a broom handle.[194] King Goldemar revealed the secret transgressions of clergymen, much to their chagrin.[97]

Even friendly kobolds are rarely completely good,[195] and house kobolds may do mischief for no particular reason. They hide things, push people over when they bend to pick something up, and make noise at night to keep people awake.[196][197] The kobold Hödekin of Hildesheim roamed the walls of the castle at night, forcing the watch to be constantly vigilant.[184] A kobold in a fishermen's house in Köpenick on the Wendish Spree reportedly moved sleeping fishermen so that their heads and toes lined up.[198] King Goldemar enjoyed strumming the harp and playing dice.[97]

Good fortune

[edit]A kobold can bring wealth to his household in the form of grain and gold.[134] In this function it often is called Drak. A legend from Saterland and East Friesland tells of a kobold called the Alrûn (which is the German term for mandrake). Despite standing only about a foot tall, the creature could carry a load of rye in his mouth for the people with whom he lived and did so daily as long as he received a meal of biscuits and milk.

Kobolds bring good luck and help their hosts as long as the hosts take care of them. The kobold Hödekin, who lived with the bishop of Hildesheim in the 12th century, once warned the bishop of a murder. When the bishop acted on the information, he was able to take over the murderer's lands and add them to his bishopric.[184]

The house-spirit ins some areas were called Alrûn ("mandrake"), though this this was also the name of a trinket sold in bottles,[199] which instead of being genuine mandrake could be any doll shaped from some plant root.[75] And the saying to have an Alrûn in one's pocket means "to have luck at play".[78] However, kobold gifts may be stolen from the neighbours; accordingly, some legends say that gifts from a kobold are demonic or evil.[134] Nevertheless, peasants often welcome this trickery and feed their kobold in the hopes that it continue bringing its gifts.[11] A family coming into unexplained wealth was often attributed to a new kobold moving into the house.[134]

Eradication

[edit]Folktales tell of people trying to rid themselves of mischievous kobolds. In one tale, a man with a kobold-haunted barn puts all the straw onto a cart, burns the barn down, and sets off to start anew. As he rides away, he looks back and sees the kobold sitting behind him. "It was high time that we got out!" it says.[200] A similar tale from Köpenick tells of a man trying to move out of a kobold-infested house. He sees the kobold preparing to move too and realises that he cannot rid himself of the creature.[201]

Exorcism by a Christian priest works in some tales; in certain versions of the Hödekin in the kitchen of the castle enfeoffed to the Bishop of Hildesheim, the bishop managed to exorcise Hödekin using church-spells.[189][178][w]

Mine spirits

[edit]Another class of kobold lives in underground places. Folklorists have proposed that the mine kobold derives from the beliefs of the ancient Germanic people. German legends about these kobold mine spirits held that they could play tricks, but could also bring riches, with the caveat that such kobolds are difficult to distinguish from nature demons,[202] i.e., the kobold has become equatable with gnome or "mine demon".[203][204]

Kobolds that live in mines are hunched and ugly and some can materialise into a brick.[citation needed]

Legends often paint underground kobolds as evil creatures. In medieval mining towns, people prayed for protection from them.[205] They were blamed for the accidents, cave-ins, and rock slides that plagued human miners.[196] One favoured kobold prank was to fool miners into taking worthless ore. For example, 16th-century miners sometimes encountered what looked to be rich veins of copper or silver, but which was unsmeltable,[20] or, when smelted, proved to be little more than a pollutant and could even be poisonous.[206] Miners tried to appease the kobolds with offerings of gold and silver and by insisting that fellow miners treat them respectfully.[207][208] Nevertheless, some stories claim that kobolds only returned such kindness with more poisonous ores.[202] Miners called these ores cobalt after the creatures from whom they were thought to come.[20][207]

Tales from other parts of Germany make mine kobolds beneficial creatures, at least if they are treated respectfully.[208] Nineteenth-century miners in Bohemia and Hungary reported hearing knocking in the mines. They interpreted such noises as warnings from the kobolds to not go in that direction.[120] Other miners claimed that the knocks indicated where veins of metal could be found: the more knocks, the richer the vein.[209]

Other specialized kobolds

[edit]Other than the mine spirit kobold above, there are others "house spirits" that haunt shops, ships, shops, etc. places of various professions.

The Klabautermann (cf. § Water spirits below) is a kobold from the beliefs of fishermen and sailors of the Baltic Sea.[210] Adalbert Kuhn recognized in northern Germany the form Klabåtersmanneken (syn. Pûkse) which haunted mills and ships, subsisted on the milk put out for them, and return performed chores such as milking cows, grooming horse, helping the kitchen, or scrubbing the ship.[211]

The biersal, sometimes called a type of kobold live in breweries and the beer cellars of inns or pubs, bring beer into the house, clean the tables, and wash the bottles, glasses and casks.[212] The family must leave a portion of their supper (or beer, for the biersal. —see Hödfellow) to the spirit and must treat the kobold with respect, never mocking or laughing at the creature.

One such legend, first appearing late in the 19th century, concerns a house spirit named Hödfellow that resided at the Fremlin's Brewery in Maidstone, Kent, England who was wont to either assist the company's workers or hinder their efforts depending on whether he was being paid his share of the beer.[213] This association between kobolds and work gave rise to a saying current in 19th-century Germany that a woman who worked quickly "had the kobold".[214]

A spiritualist's report

[edit]In 1884, spiritualist Emma Hardinge Britten reported a story from a Madame Kalodzy, who claimed to have heard mine kobolds while visiting a peasant named Michael Engelbrecht: "On the three first days after our arrival, we only heard a few dull knocks, sounding in and about the mouth of the mine, as if produced by some vibrations or very distant blows..."[215]

In 1820, Spiritualist Emma Hardinge Britten recorded a description of mine kobolds from a Madame Kalodzy, who stayed with peasants named Dorothea and Michael Engelbrecht.[216]

The same informant claimed to later have seen the kobolds first-hand. She described them as "diminutive black dwarfs about two or three feet in height, and at that part which in the human being is occupied by the heart, they carry the round luminous circle first described, an appearance which is much more frequently seen than the little black men themselves."[215]

Parallels

[edit]Kobold beliefs mirror legends of similar creatures in other regions of Europe, and scholars have argued that the names of creatures such as goblins and kabouters derive from the same roots as kobold. This may indicate a common origin for these creatures, or it may represent cultural borrowings and influences of European peoples upon one another. Similarly, subterranean kobolds may share their origins with creatures such as gnomes and dwarves.

Sources equate the domestic kobold with creatures such as the English boggart, hobgoblin and pixie, the Scottish brownie, and the Scandinavian nisse or tomte;[217][191][151] while they align the subterranean variety with the Norse dwarf and the Cornish knocker.[218][219] Irish writer Thomas Keightley argued that the German kobold and the Scandinavian nis predate the Irish fairy and the Scottish brownie and influenced the beliefs in those entities, but modern folklorist Richard Mercer Dorson noted Keightley's bias as a strong adherent of Grimm, embracing the thesis of regarding ancient Teutonic mythology as underlying all sorts of folklore.[220]

British antiquarian Charles Hardwick ventured a theory that the spirits like the kobold in other cultures, such as the Scottish bogie, French goblin, and English Puck were also etymologically related.[222] In keeping with Grimm's definition, the kobaloi were spirits invoked by rogues.[223]

The kobold as mining spirits are compared to the English bluecap and Cornish knocker,[19] as well as the Welsh coblynau.[224]

Heinzelmann

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be merged into Heinzelmänchen. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2024. |

Most often, kobolds remain completely invisible.[117]

The Heinzelmann from the folklore of Hudermühlen Castle in the region of Lüneburg, appeared as a beautiful boy with blond, curly hair to his shoulders and dressed in a red silk coat.[225] His voice was "soft and tender like that of a boy or maiden".[210]

The Heinzelmänchen of Cologne marched from the city and sailed away when a tailor's wife strewed peas on the stairs to trip them so she could see them. In 1850, Keightley noted that the Heinzelmänchen "[had] totally disappeared, as has been everywhere the case, owing to the curiosity of people, which has at all times been the destruction of so much of what was beautiful in the world".[226]

The Heinzelmann's fingers were childlike, and his face was like a skull, without body heat.[227]. and King Goldemar was said to sleep in the same bed with Neveling von Hardenberg. He demanded a place at the table and a stall for his horses.[97]

There is a tale of one holyman who visited the home of Heinzelmann and refused to accept the kobold's protests that he was a Christian. Heinzelmann threatened him, and the nobleman fled.[228] Another nobleman refused to drink to the kobold's honour, which prompted Heinzelmann to drag the man to the ground and choke him near to death.[229]

The Heinzelmann of Hundermühlen Castle arrived in 1584 and announced himself by knocking and making other sounds.[210]

One of Heinzelmann's pranks was to pinch drunken men to make them start fights with their companions.[230] Heinzelmann liked his lord's two daughters and scared away their suitors so that the women never married.[161]

Legends tell of those who try to trick a Heinzelmann into showing itself being punished for the misdeed. For example, Heinzelmann tricked a nobleman into thinking that the kobold was hiding in a jug. When the nobleman covered the jug's mouth to trap the creature, the kobold chided him:

If I had not heard long ago from other people that you were a fool, I might now have known it of myself, since you thought I was sitting in an empty jug, and went to cover it up with your hand, as if you had me caught. I don't think you worth the trouble, or I would have given you, long since, such a lesson, that you should remember me long enough. But before long you will get a slight ducking.[231]

The lord of the Hundermühlen Castle disliked Heinzelmann and tried to escape him by taking up residence with his family and retinue elsewhere. Nevertheless, the invisible kobold travelled along with them as a white feather, which they discovered when they stayed at an inn.

Why do you retire from me? I can easily follow you anywhere, and be where you are. It is much better for you to return to your own estate, and not be quitting it on my account. You see well that if I wished it I could take away all you have, but I am not inclined to do so.[232]

A Cologne legend recorded by Keightley claims that bakers in the city in the early 19th century never needed hired help because, each night, the kobolds known as Heinzelmänchen made as much bread as a baker could need.[59]

The Heinzelmann found things that had been lost.[233] He had a rhyme he liked to sing: "If thou here wilt let me stay, / Good luck shalt thou have alway; / But if hence thou wilt me chase, / Luck will ne'er come near the place".[234] Three famous kobolds, King Goldemar, Heinzelmann, and Hödekin, all gave warnings about danger to the owners of the home in which they lived.[184][235] Heinzelmann once warned a colonel to be careful on his daily hunt. The man ignored the advice, only to have his gun backfire and shoot off his thumb. Heinzelman appeared to him and said, "See, now, you have got what I warned you of! If you had refrained from shooting this time, this mischance would not have befallen you".[236]

When an exorcist tried to drive away Heinzelmann, the kobold tore up the priest's holy book, strewed it about the room, attacked the exorcist, and chased him away.[231][161] Insulting a kobold may drive it away, but not without a curse; when someone tried to see his true form, Goldemar left the home and vowed that the house would now be as unlucky as it had been fortunate under his care.[59]

Klabautermann

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be merged into Klabautermann. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2024. |

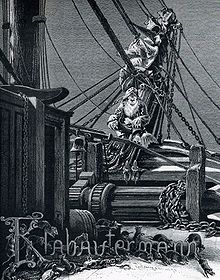

The Klabautermann] (also spelt Klaboterman and Klabotermann) is a creature from the beliefs of fishermen and sailors of Germany's north coast, the Netherlands, and the Baltic Sea, and may represent a third type of kobold[237][238] or possibly a different spirit that has merged with kobold traditions. Belief in the Klabautermann dates to at least the 1770s.[239]

According to these traditions, Klabautermanns live on ships and are generally beneficial to the crew.[238] For example, a Klabautermann will pump water from the hold, arrange cargo, and hammer at holes until they can be repaired.[240] The creatures are thought to be especially useful in times of danger, preventing the ship from sinking.[238] The Klabautermann is associated with the wood of the ship on which it lives. It enters the ship via the wood used to build it, and it may appear as a ship's carpenter.[239] The Klabautermann typically appears as a small, pipe-smoking humanlike figure wearing a yellow nightcap-style sailor's hat and a red or grey jacket.[239][237]

The Klabautermann's benevolent behaviour lasts as long as the crew and captain treat the creature respectfully. A Klabautermann will not leave its ship until it is on the verge of sinking. To this end, superstitious sailors in the 19th century demanded that others pay the Klabautermann respect. Ellett has recorded one rumour that a crew even threw its captain overboard for denying the existence of the ship's Klabautermann.[238] Heinrich Heine has reported that one captain created a place for his ship's Klabautermann in his cabin and that the captain offered the spirit the best food and drink he had to offer.[239] Klabautermanns are easily angered.[238] Their ire manifests in pranks such as tangling ropes and laughing at sailors who shirk their chores.[240]

The sight of a Klabautermann is an ill omen, and in the 19th century, it was the most feared sight among sailors.[240]According to one tradition, they only appear to those about to die.[237] Another story recorded by Ellett claims that the Klabautermann only shows itself if the ship is doomed to sink.[240]

German writer Heinrich Smidt believed that the sea kobolds, or Klabautermann, entered German folklore via German sailors who had learned about them in England. However, historians David Kirby and Merja-Liisa Hinkkanen dispute this, claiming no evidence of such a belief in Britain. An alternate view connects the Klabautermann myths with the story of Saint Phocas of Sinope. As that story spread from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea. Scholar Reinhard Buss instead sees the Klabautermann as an amalgamation of early and pre-Christian beliefs mixed with new creatures.[241]

In culture

[edit]Literary references

[edit]German writers have long borrowed from German folklore and fairy lore for both poetry and prose. Narrative versions of folktales and fairy tales are common, and kobolds are the subject of several such tales.[242] The kobold is invoked by Martin Luther in his Bible, translates the Hebrew lilith in Isaiah 34:14 as kobold.[243][244]

In Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust, the kobold represents the Greek element of earth.[245] This merely goes to show that Goethe saw fit to substitute "kobold" for the gnome of the earth, one of Paraceslsus's four spirits.[246] In Faust Part II, v. 5848, Goethe uses Gütchen (syn. Güttel above) as synonym for his gnome.[27][247]

Theatrical and musical works

[edit]A kobold is musically depicted in Edvard Grieg's lyric piece, opus 71, number 3.

Der Kobold, Op. 3, is also Opera in Three Acts with text and music by Siegfried Wagner; his third opera and it was completed in 1903.

The kobold characters Pittiplatsch occurs in modern East German puppet theatre. . Pumuckl the kobold originated as a children's radio play series (1961).

Games and D&D literature

[edit]Kobolds also appear in many modern fantasy-themed games like Clash of Clans and Hearthstone, usually as a low-power or low-level enemy. They exist as a playable race in the Dark Age of Camelot video game. They also exist as a non-playable rat-like race in the World of Warcraft video game series, and also feature in tabletop games such as Magic: The Gathering. In Dungeons & Dragons, the kobold appears as an occasionally playable race of lizard-like beings. In Might and Magic games (notably Heroes VII), they are depicted as being mouse-dwarf hybrids.

Fantasy novels and anime

[edit]The fantasy novel Record of Lodoss War adapted into anime depicts kobolds as dog-like, based on earlier versions of Dungeons & Dragons, resulting in many Japanese media depictions doing the same.

In the novel American Gods, by Neil Gaiman, Hinzelmann is portrayed as an ancient kobold[104] who helps the city of Lakeside in exchange for killing one teenager once a year.

In the novel The Spirit Ring by Lois McMaster Bujold, mining kobolds help the protagonists and display a fondness for milk. In an author's note, Bujold attributes her conception of kobolds to the Herbert Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover translation of De re metallica.

See also

[edit]- Gremlin

- Kobold (Dungeons & Dragons)

- Gütel, a kobold variety

- Niß Puk, the kobold of Northern Germany and Denmark

- Yōsei – Spiritlike creature from Japanese folklore

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Also Bergmännlein (Latin: virunculos montanos), as attested by Georg Agricola.

- ^ While Johannes Mathesius had considered the kobel and kobold to be equivalent.

- ^ Latin: cobalus, virunculos montanos. These occur in Agricola De animatibus (1549), and the latter is the same as Berg- "mountain" + männlein "diminutive of man". This is indirectly substantiated by Agricola, who glosses his daemon metallicus as Bergmännlein in Bermanus sive de re metallica (1530) (p. 464 om 1558 edition, also seen used in his Liber XII, as quoted by Grimm (1888), Teut. Myth. 4: 1414.

- ^ Grimm also characterizes kobold as "tricky home-sprite" and comments at length on its laughter.[15] Note that the cobali are described as having the habit to "mimic men", "laugh with glee, and pretend to do much, but really do nothing", and "throw pebbles at the workmen" doing no real harm.[17]

- ^ Compare published map by Schäfer et al. (2000)[26]

- ^ a b Niss is categorized E "pet name", while Puck is considered G. "devil name" by the HdA.[7]

- ^ The remaining categories are: F. Rufname (proper first name) G. Devil-name (incl. Puck) H. Literary name (e.g. Gesamtname), I. Dragon name (incl. Alf, Alber, Drak, Alrun, Tragerl, Herbrand K. Different names (Mönch).

- ^ The Heinzelmännchen was a house spirit particularly associated with Cologne (Köln),[25] The origins of Heinzelmännchen according to oral tradition was recorded by Ernst Weyden (1826) Cöln's Vorzeit, and translated by Thomas Keightley.[25][59] and Hänneschen was common in Cologne's puppet theater.[60] These Heinzelmännchen of Cologne resemble short, naked men.[59]

- ^ Classified as "E. pet name (German:Kosenamen)" type names in the HdA.

- ^ Thorpe cites Grimm's DM so he realizes this is a term for a plant root (kräuzer).[79]Classing these root dolls as kobold contradicts Grimm's opinion: "The alraun[e] or gallowsmannikin (German: Galgenmännlein) in Grimms (1816) Deutsche Sagen nos. 83 84 is not properly a kobold, but a semi-diabolic being carved out of a root".[80] The generic term appears to be Glucksmännchen for dolls or figurines fashioned from plant roots, including mandrake.[75]

- ^ Rather than Hödekin being strictly correct, the vowel "ö" actually occurs as Early modern German "o with e above" in Praetorius, and transcribed that way by Wyl.

- ^ Though not specifying examples from the Grimms DS, etc.

- ^ Also called dönnerkuhle.

- ^ Note that the English translation of the essay "tales from his own collection, no. 346{ [sic].." is a misprint for No. 348 "Der Teufel in Flehde is localized in Rehm-Flehde-Bargen in the Dithmarschen.[129] In the Beowulf essay he also cites "Der Dränger" ("the presser", No. 347), said to breach dams, localized around the mouth of the Eider, close to e.g. Stapelholm.

- ^ Müllenhoff: German: Letute aus.. Stapelholm, die den Niß Puk gesehen haben.."

- ^ Müllenhoff: "nicht größer als ein oder anberthalbjähriges Kind sei. Andre sagen, er sei so gross wie ein dreijähriges".

- ^ Müllenhoff: "Er hat einen grosen Kopf und lange Arme, aber kleine, helle, kluge Augen".

- ^ Müllenhoff: "trägt er ein paar rothe Strümpfe,.. lange graue oder grüne Zwillichjacke und.. rothe spitze Mütze".

- ^ Also drak

- ^ Cf. Drak lore of this city under § Fire phenomena.

- ^ A fire drake is used figuratively in Shakespeare, but commentators note the "fire drake" could have also denoted a Will-o'-the-wisp in Shakespearean times.[140]

- ^ "Hütgin" used jocularly as salutation to wife: "tibi uxorem.. commendo". Variant spelling ignored in Eng. tr.

- ^ Not in the Praetorius's version, quoted by Heine.[136]

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ a b Evans, M. A. B. (1895). "The Kobold and the Bishop of Hidesheim's Kitchen-boy". Nymphs, Nixies and Naiads: Legends of the Rhine. Illustrated by William A. McCullough. New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. p. 33. ISBN 9780738715490.

- ^ a b Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 500, 501: "lar, lar familiares"; "small lars"; Grimm (1875), pp. 413–414

- ^ Notker (1901). Fleischer, Ida Bertha Paulina [in German] (ed.). Die Wortbildung bei Notker und in den verwandten Werken: eine Untersuchung der Sprache Notkers mit besonderer Rücksicht auf die Neubildungen ... Göttingen: Druck der Dieterich'schen Univ.-Buchdruckerei (W. Fr. Kaestner). p. 20.

- ^ a b c Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 500.

- ^ a b Old High German hûsing is glossed as Latin penates in Notker,[3] cited by Grimm.[4]

- ^ a b c Simrock, Karl Joseph (1887) [1855]. Handbuch der deutschen Mythologie: mit Einschluss der nordischen (6 ed.). A. Marcus. p. 451.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens, Walter de Gruyter (1974), s.v. "Kobld", Band 5: 26–31ff. Reprint (1987), p. 5: 29ff

- ^ The Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens assigns kobold synonyms separately as A. doll names and B. names for deriding an imbecile, but comments that the A type names served as B type pejoratives.[7]

- ^ a b c d e Müller-Fraureuth, Karl (1906). "Kap. 14". Sächsische Volkswörter: Beiträge zur mundartlichen Volkskunde. Dresden: Wilhelm Baensch. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Schrader, Otto (1906). "Aryan Religion". Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 24.; (1910) edition

- ^ a b c d Dowden, Ken (2000). European Paganism. London: Routledge. pp. 229–230. ISBN 0-415-12034-9.; reprinted in: Dowden, Ken (2013) [2000]. European Paganism. Taylor & Francis. pp. 229–230. ISBN 9781134810215.

- ^ a b Johansson, Karl Ferdinand (1893). "Sanskritische Etymologien". Indogermanische Forschungen. 2: 50.

- ^ Wexler, Paul (2002). Trends in Linguistics: Two-tiered Relexification in Yiddish: Jews, Sorbs, Khazars, and the Kiev-Polessian Dialect. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017258-5. p. 289.

- ^ Yiddish inguist Paul Wexler (2002), discussing German hold "beautiful" tangentially notes the etymology of kobold deriving koben "pigsty" +hold "stall spirit". He suggests challah bread may have something to do with the German folklore of Frau Holle, but this origins masked by using a spelling suggestive of Hebrew origins.[13]

- ^ a b Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 502.

- ^ a b Kretschmer, Paul (1928). "Weiteres zur Urgeschichte der Inder". Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der indogermanischen Sprachen. 55. p. 89 and p. 87, n2.

- ^ a b c d Agricola, Georgius (1912). Georgius Agricola De Re Metallica: Tr. from the 1st Latin Ed. of 1556. Translated by Hoover, Herbert Clark and Lou Henry Hoover. London: The Mining Magazine. p. 217, n26.

- ^ Knapp 62.

- ^ a b Summers, Montague, p. 216, note 4. in Taillepied, Noël (1933) [1588] A Treatise of Ghosts: Being the Psichologie, Or Treatise Upon Apparitions, Translated by Summers, London: Fortune Press.

- ^ a b c d Wothers, Peter (2019). Antimony, Gold, and Jupiter's Wolf: How the elements were named. Oxford University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9780192569905.

- ^ a b Lecouteux, Claude (2016). "BERGMÄNNCHEN (Bergmännlein, Bergmönch, Knappenmanndl, Kobel, Gütel; gruvrå in Sweden)". Encyclopedia of Norse and Germanic Folklore, Mythology, and Magic. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781620554814.

- ^ The Hoovers' rendition "little miners"[17] for the mine spirits cannot possibly derive directly from Latin virunculos montanos (lit. "mountain manikin"), and the Hoovers must have resorted to double-translating from the German: Bergmännlein (diminutive of Bergmann meaning "miners"). However, Bergmännlein is actually a standalone term meaning a kind of "mine spirit".[21]

- ^ Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch, Band 5, s.v. "Kobel"

- ^ Kobalos

- ^ a b c d e f Kluge, Friedrich; Seebold, Elmar, eds. (2012) [1899]. "Heinzelmännchen". Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (25 ed.). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 406. ISBN 9783110223651.

- ^ a b c d Schäfer, Florian [in German]; Pisarek, Janin [in German]; Gritsch, Hannah (2020). "2. Die Geister des Hauses. § Der Kobold". Hausgeister!: Fast vergessene Gestalten der deutschsprachigen Märchen- und Sagenwelt. Köln: Böhlau Verlag. p. 34. ISBN 9783412520304.

- ^ a b c Handwörterbücher zur deutschen Volkskunde: Abteilung I. Aberglaube, Walter de Gruyter (1931), s.v. "Gütel, Gütchen, Jüdel, Jütel, usw. (Dämonenname", pp. 1233–1234ff

- ^ Köhler, Joseph August Ernst [in German] (1867). "XIII. Sagen §50. Das Heugütel". Volksbrauch, Aberglauben, Sagen und andre alte Ueberlieferungen im Voigtlande: Mit Berücks. d. Orlagau's u. d. Pleißnerlandes. Ein Beitr. z. Kulturgeschichte d. Voigtländer. Leipzig: Fleischer. p. 476.

- ^ Place-marked at Reichenbach in the Thüringen-Sächsen Vogtland.[27] The form Heugütel at Reichenbach is recorded in legend.[28]

- ^ Künzig, Johannes [in German] (1930). "Ghost miners". Badische Heimat. 17: 112ff.

- ^ a b c d Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 505.

- ^ Classed as A or doll name by HdA, though Grimm suggest it is a noise name (which would be D). Place-marked at Freiburg im Breisgau since it is in Baden, in the nexus with Swabia. Johannes Künzig's paper on it is signed at that city, and discusses Poppele as a Baden tradition;[30] while Grimm says it is the house spirit in Swabia.[31]

- ^ Köhler (1867) §56. Schretzelein, p. 479.

- ^ Place-marked Hof, Bavaria, the höfische Chronik being named as source for Schretzelein legend.[33]

- ^ Place-marked at Winzenberg/Hildesheim

- ^ a b Grimms (1816). Deutsche Sagen No. 75 "Hinzelmann", pp. 103–128

- ^ Place-marked at Hudemühlen as per Grimms' No. 75 with a single source.[36]

- ^ Place-marked at Fichtelberg after Grimm

- ^ a b Grimms (1816). Deutsche Sagen No. 76 "Klopfer", p. 128

- ^ Place-marked its setting, the ruin of Castle Flügelau at Crailsheim in Franconia, as per Grimms' No. 76 with its single source.[39]

- ^ a b c Kantzow, Thomas (1816). Kosegarten, Johann Gottfried Ludwig (ed.). Pomerania, oder Ursprunck, Altheit und Geschicht der Völcker und Lande Pomern, Cassuben [&c.]. Greifswald: in Commission bey Ernst Mauritius. p. 333.

- ^ Place-marked at Mecklenburg, as per Kantzow.[41]

- ^ a b c d Müllenhoff (1845) No. 430"Die Wolterkens", pp. 317–319 with various notes.

- ^ Place-marked at Nortorf,where Meigen had his pastorship.[43]

- ^ Thorpe (1852), pp. 48–49.

- ^ Place-marked at Stapelholm, as per Müllenhoff and Thorpe[43][45]

- ^ a b Berger (2001), p. 163.

- ^ Place-markable on the island of Rügen, Kreis Stolp (now Słupsk) Kreis Köslin (now Koszalin), some of the localizations of Pomeranian lore,[47] but Polish territory are out of bounds on map.

- ^ Berger (2001), p. 168.

- ^ a b c Thorpe (1852), p. 155.

- ^ Kuhn & Schwartz (1848) 119.Spuk am Thürberg

- ^ Place-marked on the island of Rügen[49] Swinemünde / Świnoujście[50] and at Thürberg near Tremmen[51]

- ^ Grimm (1875), pp. 420–421; Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 508–509

- ^ a b Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 501.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 505, 507.

- ^ Ch. XVII, §Scrat (faunus). Wood-folk. In the annotation supplementary volume to be more precise: Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1888), 4: 1426, to Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1888), 2: 483.

- ^ Wolfdietrich, Str. 590, in von der Hagen (1855) edition Heldenbuch, Vol. 1, p. 236. Cited by Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1888), 1: 483.

- ^ Grimm (1878), 4: 139 only has: "ein guttel (? götze). Wolfdietr. in Hagens heldenb. s. 236". But Grimm mentions götze elsewhere as 'idol' (Grimm (1875), 1: 12, 86 and Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), 1: 513, citing Sommer, pp. 38, 173, where it is evidently a dress-up baby Jesus doll.)

- ^ a b c d Keightley (1850), p. 257.

- ^ a b c Grässe, Johann Georg Theodor (1856). "Zur Geschichte des Puppenspiels". Die Wissenschaften im neunzehnten Jahrhundert, ihr Standpunkt und die Resultate ihrer Forschungen: eine Rundschau zur Belehrung für das gebildete Publikum. 1. Romberg: 559–660.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 503–504 where vowel changes are ignored, listing a mix of "heinzelman, hinzelman, hinzemännchen" together.

- ^ The HdA must concur, since it excludes Heinzelman from "Pet names",[7] as does the map in the 2020 book published in Cologne which omits Heinzelmännchen.[26]

- ^ Grimm (1875), p. 417; Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 503–504, rendered "noisy ghost".

- ^ Praetorius (1666), p. 366.

- ^ Grimms (1816). Deutsche Sagen No. 71 "Kobold", pp. 90–92

- ^ a b Praetorius gives "Court Chimgen",[64] transliterated as "Kurd Chimgen" by the Grimms DS No. 71[65] Heine in the original German quotes "lieb Chimchen", though translated "dear Chimgen".

- ^ Possibly East Prussian.

- ^ Attested by Prateorius, but since his concern was with the legend of Rübezahl, one would assume he is discussing house spirits generally of that area.

- ^ Prateorius (1666) apud Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), pp. 140, 141

- ^ a b c Saintine, Xavier-Boniface (1862). "XII. § Un Kobold au service d'une cuisinière". La Mythologie du Rhin. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie. pp. 287–289.; —— (1903). "XII. §A Kobold in the Cook's Employ". La Mythologie du Rhin. Translated by Maximilian Schele de Vere; Illustrated by Gustave Doré. Akron, Ohio: Saalfield Publishing Company. pp. 315–317.

- ^ "Chim", "Kurt Chimgen", "Himschen", "Heinzchen" were what German and Alsatian cooks (Alsace-Lorraine was territory annexed to Germany from after the Franco-Prussian War to WWII.) call their kitchen kobolds by, according to Saintine.[70]

- ^ Meiger, Samuel [in German] (1587). "III. Bok, II. Capittel: Van den laribus dometicis edder husknechtkens, de men ok Wolterken under Chimken an etliken örden nömet". en Panurgia Lamiarum, Sagarum, Strigum, ac Veneficarum totius cohortis Magicæ Cacodaemonia. Vol. 3. Hamburg. III.ii.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 503–504.

- ^ Paraphrased by Mullenhoff, where Meiger is identified as being pastor at Nortorf.[43]

- ^ a b c Ersch, Johann Samuel; Gruber, Johann Gottfried, eds. (1860). "Glückmänchen". Allgemeine Encyclopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste. Vol. 1. Leipzig: Brockhaus. pp. 303–304.

- ^ Arrowsmith, Nancy (2009) [1977]. Field Guide to the Little People: A Curious Journey Into the Hidden Realm of Elves, Faeries, Hobgoblins and Other Not-So-Mythical Creatures. Woodbury, Minnesota.: Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 126. ISBN 9780738715490.

- ^ Thus Arrowsmith lists synonyms for mandrake (Allerünken, Alraune, Galgenmännlein) as also standing as synonyms for kobold in the south.[76]

- ^ a b Thorpe (1852), pp. 156–157.

- ^ Thorpe citing Grimm (1844) Ch. XXXVII, 2: 1153 = Grimm (1877) Ch. XXXVII, 2: 1007.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 513, n2; Grimm (1878), 3: 148, note to 1: 424

- ^ Praetorius (1666), p. 377.

- ^ Wyl (1909), p. 122, n1.

- ^ a b Grimms (1816). Deutsche Sagen No. 74 "Hütchen", pp. 97–103

- ^ Aschner (1909), p. 64.

- ^ a b c Praetorius explains that the sprite "on account of the hat he wears on his head is called Pilateum, or Hödekin in the speech of Saxony".[81] Wyl gives mistyped "Pilateum" [sic] and glosses it as deriving from adj. pilleatus thus meaning Filzkappe "Felt Cap".[82] Grimm DS No. 74 also gives Filz-Hut,[83] from one of the sources, i.e. Johann Weyer.[84]

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 463, 508.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 255.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 508.

- ^ Omitting "heinzelman[n]" here commingled by Grimm (and separated, as does HdA), as it is distinguishable from Hinzelmann, as already explained above.

- ^ a b Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 503.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 480, 503.

- ^ a b Dünnhaupt, Gerhard (1980). "Johann Praetorius". Bibliographisches Handbuch der Barockliteratur: hundert Personalbibliographien deutscher Autoren des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts. Vol. 2. Hiersemann. p. 1424. ISBN 9783777280295.

- ^ Saintine (1862), p. 287; Saintine (1903), p. 316

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 180, 505.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 507.

- ^ Even though Grimm follows with Poppele suggesting it to be noise-related with the meaning of "muffled",[31] it is more obviously cognate to Puppe "doll" and is categorized as A for doll-names by the HdA. Likewise, though Grimm thought Butz was reference to noise,[95] Butz seems to refer to a "tree trunk" and thus classed as A for doll-name by HdA.

- ^ a b c d Keightley (1850), p. 256.

- ^ Keightley (1850), pp. 256–257.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 453, 466, 509.

- ^ Franz, Adolf ed. (1906), Frater Rudolfus (c. 1235-1250) De officio cherubyn, p. 428

- ^ Johansons, Andrejs [in Latvian] (1962). "Der Kesselhaken im Volksglauben der Letten". Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 87: 74.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 500, 501 and notes, vol. 4, Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1888), p. 1426

- ^ Schrader 24.

- ^ a b Müller-Olesen, Max F. R. (2012). "Ambiguous Gods: Mythology, Immigration, and Assimilation in Neil Gaiman's American Gods (2001) and 'The Monarch of the Glen' (2004)". In Bright, Amy (ed.). “Curious, if True”: The Fantastic in Literature. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 136 and note15. ISBN 9781443843430.

- ^ Schrader (2003) [1908], p. 24[103] also quoted by Olesen (2012),[104] but the latter appears to be synthesis and not direct quoting.

- ^ Maclaren xiii.

- ^ Also repeated in other sources such as Maclaren[106] and Dowden (2000)[11]

- '^ Grimm (1875), 1:415: lachen als ein kobold, p. 424 "koboldische lachen"; Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 502 "laugh like a kobold", p. 512 tr. as "goblin laughter".

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 501: "for fun; Simrock: "zuletzt mehr zum Scherz oder zur Zierde lately more as joke or for decor".

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 254.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 501, citing Wahtelmaere 140, "rihtet zuo mit den snüeren die tatermanne alludes to it being "guid[ed].. with strings".

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 501–502.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 501 re kobold struck dum band the wooden bishop, citing Mîsnaere in Amgb (Altes meistergesangbuch in Myllers sammlung) 48a.

- ^ Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch, Band 5, s.v. "Kobold"

- ^ A man hearing confession compared to kobold, in a Fastnachtspiel.[114]

- ^ Katalog der Texte. Älterer Teil (G - P), s.v.," KoarW/7/15", citing Schröder 32, 211. Horst Brunner ed.

- ^ a b c d Lüthi (1986), p. 4, note*.

- ^ Saintine (1862), p. 289.

- ^ a b Grimm (1875), p. 420; Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), p. 508

- ^ a b Britten 32.

- ^ Golther (1908), p. 142.

- ^ Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), pp. 508–509, 503.

- ^ Cf. Thorpe (1852), p. 48

- ^ Müllenhoff (1845) No. 434 "Niß Puk in Owschlag", subtale 1.: "rothe Mütze"; No. 435 "Neß Puk im Kasten" "was one tiny span tall" and "einer spitzen rothen Mütze"; No. 439 "Die Unterirdischen schlecken Milch" "Diese kleinen Leuten.. [were about 1.5 feet tall and wore] ganz schwarze Kleider und hatten rothe spitze Mützen "

- ^ Müllenhoff, Karl (1849). "Der Mythus von Beóvulf". Zeitschrift für deutsches Alterthum. 7: 425–426.

- ^ Müllenhoff, Karl (2005) [1998]. "59 Karl Müllenhoff 1849". In Shippey, T. A.; Haarder, Andreas (eds.). Beowulf: The Critical Heritage. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 9781134970933.

- ^ He calls the "Schwertmann" a "kobold" in his essay on Beowulf pondering on the connection between such spirits and Grendel that assaulted the Danish palace;[125] however, the folklores he cites are not all specifically translated in the paraphrase inserted in the English translation of the essay.[126]

- ^ a b Müllenhoff (1845) No. 350 "Schwertmann", pp. 261–262, with an endnote at p. 601.

- ^ Müllenhoff (1845), p. 258.

- ^ Translated without attribution by Thorpe (1852), pp. 48–49

- ^ Berger (2001), pp. 163–167.

- ^ a b c Thorpe (1852), p. 156.

- ^ Kuhn & Schwartz (1848), No. 18 "Pûks zieht mit dem Gebälk, pp. 15–16"

- ^ a b c d e f Ashliman (2006) "Household Spirits", p. 46.

- ^ a b c d Rose 40, 183.

- ^ a b c d e Prateorius on Poltergeister (hobgoblins) haunting the house, quoted in English by Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), pp. 139–141, translated from (1666) Anthropodemus Plutonicus, Band 1, "VIII. von Hausmännern", p. 363–364

- ^ Cf. Praetorius apud Heine: "the ancients.. conceive[d] of hobgoblins (German: Poltergeister) as.. stature like small children, .. [accord. to some, with] "knives sticking in their backs"; and "the superstitious believe them to be the souls of former occupants of their houses, murdered there long ago".[136]

- ^ Golther (1908), p. 145.

- ^ Saintine (1862), p. 290; Saintine (1903), pp. 318–319

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1821). Boswell, James (ed.). Richard III. Henry VIII. The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare 19. Illustrated by Edmond Malone. R. C. and J. Rivington. p. 485.

- ^ a b Ashliman (2006) "Fire", p. 53.

- ^ Jahn (1886) No. 154 "Das Spâei", p. 129

- ^ Haas (1899) No. 69 "Das Sparei"; No. 70 "Puk soll ausgebrütet werden"

- ^ More specifically a kobold or rötjaket from an egg in Jahn, No. 154. from Kratzig (now Kraśnik Koszaliński).[142] and Haas (1896) from Rügen, two tales.[143]

- ^ Jahn (1886) No. 135 "Das Dorf Konerow", from a village in Kreis Grafenwald; Jahn (1886) No. 146 "Die beiden Rôdjäckten in Gollnow"

- ^ Haas (1912) No. 53. "Der Puk als Hahn".

- ^ Berger (2001), p. 167.

- ^ Thorpe (1852), pp. 155–156.

- ^ Keightley (1850), pp. 244–245.

- ^ a b Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), p. 140.

- ^ a b Maclaren 223.

- ^ Thorpe 141.

- ^ Thorpe 84.

- ^ Saintine (1862), p. 287.

- ^ Praetorius (1666), pp. 363–364, 365–366: "Messer in den Rücken.. Schlacht-Messer in Rücken", apud Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), p. 139

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 252.

- ^ Martin Luther (1566) Tischreden (Table Talk) apud Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), pp. 140–141, via Dobeneck

- ^ This matches the retelling given by Saintine (1862), accompanied by Gustave Doré's illustration of the child floating in its own blood inside a tub, but the text is altered and the illustration omitted in the English translation.[70]

- ^ a b Lüthi (1986), p. 5.

- ^ Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), pp. 139–142.

- ^ a b c Rose 151–2.

- ^ Grässe, Johann Georg Theodor (1867). "469. Der Chimmeke in Loitz". Sagenbuch des preussischen Staats. Vol. 2. Glogau: Carl Flemming. p. 496.

- ^ A variant aboutChimmeke, localized in Loitz also exists.[162]

- ^ Lecouteux, Claude (2016). "Dwarf names". Encyclopedia of Norse and Germanic Folklore, Mythology, and Magic. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781620554814.

- ^ Haas, Alfred [in German] (1896). Aus pommerschen Hexenprozessakten: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des pommerschen Volksglaubens. Stetten: F. Hessenland. p. 13.

- ^ Comparison made by Haas (1896)[165] The latter tale occurs in Grimm (1854) Deutsche Mythologie, p. 479, 3te Ausgabe, Band I, and "II" is a misprint, = Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883), 1: 503.

- ^ Schelwig, Samuel [in German] (1692). "XVI. Frage. Wofür die Spiritus Failiares, das ist die Dienst-Geister welche sich von den Menschen zu allerhand Verrichtung bestellen und gebrauchen lassen, [etc.]". Cynosura Conscientiae, Oder Leit-Stern Des Gewissens, Das ist: Deutliche und Schrifftmäßige Erörterung vieler, [etc.]. Frankfurt: Plener. p. 394, note *, cont. to p. 396.

- ^ Johannes Trithemius Chronicon Hirsaugiense, (1495–1503).[167]

- ^ Quoted from an "old chronicle", via in Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), pp. 141–142

- ^ Praetorius (1666), pp. 375–378.

- ^ These tales are regurgitated by Praetorius also, the prologal historical tale marked as #2.[170]

- ^ Aschner (1909), p. 63.

- ^ Also in Grimm's Deutsche Sagen "No. 74 Hütchen, a composite from several sources other than Praetorius,[83] including modern oral tradition,[172] with the kitchen tale at Grimms (1816), pp. 100–101.

- ^ Francisci, Erasmus (1690). Der Höllische Proteus; oder, Tausendkünstige Versteller: vermittelst Erzehlung der vielfältigen Bildverwechslungen erscheinender Gespenster, werffender und poltrender Geister, gespenstischer Vorzeichen der Todes-Fälle, wie auch andrer abentheurlicher Händel, arglistiger Possen, und seltsamer ... Nürnberg: In Verlegung W.M. Endters. p. 793 (pp. 792–798).

- ^ One of the Grimms' DS sources is Erasmus Francisci (1690)'s version, which adds Hödekecken as the Lower Saxon dialect form.[174]

- ^ The historical background given here is that of Herman I, Count of Winzenburg killing Burchard I. von Loccum ca. 1130 of, resulting in his loss of Winzenburg and the fiefdom reverting to the Bishopric of Hildesheim. According to the first tale, a spirit named Hüdeken alerted the bishop about the vacating of the Winzenburg Castle before avengers could try to capture it.

- ^ Grimms (1816), p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Bunce, John Thackray (2004 [1878]). Fairy Tales: Their Origin and Meaning. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4191-1909-5, p. 140

- ^ Francisci (1690), p. 795.

- ^ Grimm DS No. 74, the kitchen lad flings "Dreck aus der Küche.. oder.. Spül-Wasser kitchen filth or dishwater".[177] echoed by the actions of the "scullion" in Bunce.[178] Francisci has the Koch-Jung/ Bube/Knabe throwing just "unsaubrem Wasser unsanitary water".[179]

- ^ a b Grimms (1816), p. 101.

- ^ Francisci (1690), p. 796.

- ^ The kobold "pushed (stieß)" the master cook off the bridge in Grimms' DS[181][178] and Francisci.[182]

- ^ a b c d Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Kuhn & Schwartz (1848), "No. 82 Hans mit dem Hütchen", pp. 251–252

- ^ Oral versions of these tales are recorded by Kuhn & Schwartz as "Hans mit dem Hütchen (Hans met Häutken)".[185]

- ^ The murder of the "Bishop of Hildesheim's Kitchen-boy" is retold in nursery rhyme fashion by M. A. B. Evans (1895).[1]

- ^ Francisci (1690), p. 798.

- ^ a b Francisci (1690),[188]: "Kirchen-Beschwerungen", echoed by Grimms' DS.[181][178]

- ^ Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), p. 142.

- ^ a b Keightley (1850), p. 239.

- ^ Heine & Mustard tr. (1985), p. 143.

- ^ Maclaren 224.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 250.

- ^ Lüthi (1986), p. 4.

- ^ a b The Writers of Chantilly 98.

- ^ Saintine (1862), p. 290.

- ^ Thorpe (1852), pp. 83–84.

- ^ Thorpe (1852), p. 49.

- ^ Ashliman (2006), p. 47.

- ^ Ashliman (2006) "Kobold", pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Lurker, Manfred (2004). "Fairy of the Mine". The Routledge Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, Devils and Demons (3 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 0-415-34018-7.

- ^ Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham (1895). "Cobalt". Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Giving the Derivation, Source, Or Origin of Common Phrases, Allusions, and Words that Have a Tale to Tell. Vol. 1 (new, revised ed.). London: Cassell. p. 267.

- ^ The conflation explained by Paul Kretschmer (1928)[16] was already discussed above under §Etymology, subsection § Transitive as mine spirit.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (2003 [1934]). "Elements Known to the Alchemists", Discovery of the Elements. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-3872-0. p. 22.

- ^ Eagleson, Mary (1994). "Cobalt", Concise Encyclopedia: Chemistry. Walther de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-011451-8.

- ^ a b Rose 70.

- ^ a b Scott, Walter (1845). "Letter IV", Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. New York: Harber & Brothers, p. 110

- ^ Britten 33.

- ^ a b c Keightley (1850), p. 240.

- ^ Kuhn & Schwartz (1848), "No. 17 Klabåtersmanneken oder Pûkse", p. 15

- ^ Thorpe (1852), p. 157.

- ^ Homer, Johnny. Brewing in Kent. Gloucestershire, Amberlley Publishing, 2016 ISBN 9781445657431.

- ^ Moore, Edward (1847), editor Thomas Heywood. The Moore Rental. Manchester: Charles Simms and Co., p. 60

- ^ a b c Quoted in Britten 32.

- ^

We were about to sit down to tea when Mdlle. Gronin called our attention to the steady light, round, and about the size of a cheese plate, which appeared suddenly on the wall of the little garden directly opposite the door of the hut in which we sat.

Before any of us could rise to examine it, four more lights appeared almost simultaneously, about the same shape, and varying only in size. Surrounding each one was the dim outline of a small human figure, black and grotesque, more like a little image carved out of black shining wood, than anything else I can liken them to. Dorothea kissed her hands to these dreadful little shapes, and Michael bowed with great reverence. As for me and my companions, we were so awe-struck yet amused at these comical shapes, that we could not move or speak until they themselves seemed to flit about in a sort of wavering dance, and then vanish, one by one.[215] - ^ Baring-Gould, Sabine (2004 [1913]). A Book of Folklore. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-8710-1, p. x.

- ^ Grimm 501.

- ^ Rose 182–3.

- ^ Dorson, Richard Mercer (1999). "The Antiquary Folklorists". History of British Folklore, Volume I: The British Folklorists: A History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-20476-3, p. 54.

- ^ Hardwick, Charles (1980 [1872]). Traditions, Superstitions, and Folk-lore. Lancanshire: Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-405-13333-2.

- ^ Roby, John (1829). Traditions of Lancashire. Quoted in Hardwick, p. 139.[221] The sources spell the word khobalus.

- ^ Liddell and Scott (1940). A Greek–English Lexicon. s.v. "koba_l-os, ho". Revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-864226-1. Online version retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ Black, William George (18 March 1893). "Ghost miners". Notes and Queries. 8: 205–206.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 253.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 258.

- ^ Keightley (1850), pp. 251–252.

- ^ Keightley (1850), pp. 246–247.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 247.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 244.

- ^ a b Keightley (1850), p. 245.

- ^ Keightley (1850), pp. 241–242.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 242.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 243.

- ^ Keightley (1850), pp. 249, 256.

- ^ Keightley (1850), p. 249.

- ^ a b c Rose 181.

- ^ a b c d e Ellett, Mrs. (January 1846). "Traditions and Superstitions", The American Whig Review: A Whig Journal, Vol. III. New York: George H. Colton. p. 1017

- ^ a b c d Kirby, David, and Merja-Liisa Hinkkanen (2000). The Baltic and the North Seas. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13282-7. p. 48

- ^ a b c d Ellett (1846), p. 108.

- ^ Kirby & Hinkkanen (2000), pp. 48–49.

- ^ Gostwick, Joseph (1849). "Redmantle", German Literature. Edinburgh: William and Robert Chambers, p. 221

- ^ "Isaiah 34:14: Parallel Translations", Biblos.com. Retrieved 8 November 2007

- ^ Jeffrey, David Lyle, ed. (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8028-3634-8, p. 452.

- ^

Salamander shall glow,

Undine twine,

Sylph vanish,

Kobold be moving.

Who did not know

The elements,...— Goethe, tr. Hayward - ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1855). Faust. Translated by Abraham Hayward (6 ed.). London: Edward Moxon. p. 38.

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1897). Thomas, Calvin (ed.). Faust, the Second Part. Vol. 2. Boston: D.C. Heath. p. 366.

- Bibliography

- Aschner, Siegfried (1909). Die deutschen Sagen der Brüder Grimm (Ph. D.). Westport, CT: Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin.

- Ashliman, D. L. (2006). "Kobold". Fairy Lore: A Handbook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 0-313-33349-1.

- Berger, Katarina (2001). "X.Hausgeister. Kobold, Puk, Drak, Klabautermann". Erzählungen und Erzählstoff in Pommern 1840-1938. München: Waxmann Verlag. pp. 163ff. ISBN 9783830958697.

- Britten, Emma Hardinge (2003 [1884]). Nineteenth Century Miracles and Their Work in Every Country of the Earth. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-6290-7.

- Golther, Wolfgang (1908). "Kobolde". Handbuch der germanischen Mythologie (3rd. Rev. ed.). Stuttgart: Magnus-Verlag. pp. 141–145.

- Grimms, ed. (1816). "71. Der Kobold". Deutsche Sagen. Vol. 1. Berlin: Nicolai. pp. 90–92.

- Grimm, Jacob (1875). "XVII. Wichte und Elbe". Deutsche Mythologie. Vol. 1 (4 ed.). Göttingen: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 363–428.

- Grimm, Jacob (1878). "(Anmerkung von) XVII. Wichte und Elbe". Deutsche Mythologie. Vol. 3 (4 ed.). Göttingen: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 122–149.

- Grimm, Jacob (1883). "XVII. Wights and Elves §Elves, Dwarves". Teutonic Mythology. Vol. 2. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 439–517.

- —— (1888). "(Notes to) XVII. Wights and Elves §Elves, Dwarves". Teutonic Mythology. Vol. 4. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 1407–1436.

- Haas, Alfred [in German] (1899). Schnurren, schwänke und erzählungen von der insel Rügen. Greifswald: Julius Abel.

- Haas, Alfred [in German] (1912). Pommersche Sagen. Berlin: Hermann Eichblatt.

- Heinrich, Heine (1985) [1835]. "Concerning the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany". The Romantic School and Other Essays. Translated by Helen Mustard. New York: Continuum. pp. 128–244. ISBN 0-8264-0291-7.

- Jahn, Ulrich [in German] (1886). Volkssagen aus Pommern und Rügen. Stettin: H. Dannenberg.

- Keightley, Thomas (1850). The Fairy Mythology, Illustrative of the Romance and Superstition of Various Countries. London: H. G. Bohn.

- Kuhn, Adalbert; Schwartz, Wilhelm (1848). Nordeutsche Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche: aus Meklenburg, Pommern, der Mark, Sachsen, Thürigen, Braunschweig, Hannover, Oldenburg und Westfalen. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus.

- Lüthi, Max (1986). "1. One-Dimensionality". The European Folktale: Form and Nature. Translated by John D. Niles. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-253-20393-7.

- Müllenhoff, Karl (1899) [1845]. Sagen, Märchen und Lieder der Herzogthümer Schleswig Holstein und Lauenburg. John D. Niles. Siegen: Westdeutschen Verlagsanstalt. (Reprint of Schwerssche Buch, 1845)

- Maclaren, Archibald (1857). The Fairy Family: A Series of Ballads & Metrical Tales Illustrating the Fairy Mythology of Europe. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts.