Long and short scales

The long and short scales are two of several large-number naming systems used throughout the world for integer powers of ten:

- Long scale: Every new term greater than million is one million times larger than the previous term. Thus, billion means a million millions (1012), trillion means a million billions (1018), and so on.[1][2]

- Short scale: Every new term greater than million is one thousand times larger than the previous term. Thus, billion means a thousand millions (109), trillion means a thousand billions (1012), and so on.[1][2]

For integers less than a thousand million (< 109), the two scales are identical. At and above a thousand million (≥ 109), the two scales diverge by using the same words for different number values. These "false friends" can be a source of misunderstanding.

Many countries, including most in continental Europe and Latin America, use the long scale whereas most English-speaking countries and Arabic-speaking countries use the short scale. In all such countries, the number names are translated into the local language, but retain a name similarity due to shared etymology. Some languages, particularly in East Asia and South Asia, have large number naming systems that are different from both the long and short scales.[1][2]

For most of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, the United Kingdom largely used the long scale,[3][4] while the United States of America used the short scale,[3] so that the two systems were often referred to as British and American in the English language. After several decades of increasing British usage of the short scale, in 1974, the government of the UK fully adopted it, which is reflected in its mass media and official usage.[5][6][7][8][9][10] With very few exceptions,[11] the British usage and American usage are now identical.

The first recorded use of the terms short scale (French: échelle courte) and long scale (French: échelle longue) was by the French mathematician Geneviève Guitel in 1975.[1][2]

Comparison

At and above a thousand million (≥ 109), the same numerical value has two different names, depending on whether the value is being expressed in the long or short scale. Equivalently, the same name has two different numerical values depending on whether it is being used in the long or short scale.

Each scale has a logical justification to explain the use of each such differing numerical name and value within that scale. The short-scale logic is based on powers of one thousand, whereas the long-scale logic is based on powers of one million. In both scales, the prefix bi- refers to "2" and tri- refers to "3", etc. However only in the long scale do the prefixes beyond one million indicate the actual power or exponent (of 1,000,000). In the short scale, the prefixes refer to one less than the exponent (of 1,000).

The relationship between the numeric values and the corresponding names in the two scales can be described as:

| Value in Scientific notation |

Metric prefix | Value in numerals |

Short Scale | Long Scale | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefix | Symbol | Name | Logic | Name | Logic | ||

| 100 | 1 | One | One | ||||

| 101 | Deca | D or da | 10 | Ten | Ten | ||

| 102 | Hecto | Lower h | 100 | Hundred | Hundred | ||

| 103 | Kilo | Lower k | 1,000 | Thousand | Thousand | ||

| 104 | 10,000 | Ten thousand | Ten thousand | ||||

| 105 | 100,000 | Hundred thousand | Hundred thousand | ||||

| 106 | Mega | M | 1,000,000 | Million | 1,000×1,0001 | Million | 1,000,0001 |

| 109 | Giga | G | 1,000,000,000 | Billion | 1,000×1,0002 | Milliard or thousand million | |

| 1012 | Tera | T | 1,000,000,000,000 | Trillion | 1,000×1,0003 | Billion | 1,000,0002 |

| 1015 | Peta | P | 1,000,000,000,000,000 | Quadrillion | 1,000×1,0004 | Billiard or thousand billion | |

| 1018 | Exa | E | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 | Quintillion | 1,000×1,0005 | Trillion | 1,000,0003 |

| 1021 | Zetta | Z | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 | Sextillion | 1,000×1,0006 | Trilliard or thousand trillion | |

| 1024 | Yotta | Y | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 | Septillion | 1,000×1,0007 | Quadrillion | 1,000,0004 |

| Etc. | To go from one named order of magnitude to the next: multiply by 1,000 |

To go from one named order of magnitude to the next: multiply by 1,000,000 | |||||

The relationship between the names and the corresponding numeric values in the two scales can be described as:

| Name | Short Scale | Long Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value in Scientific notation |

Metric prefix | Logic | Value in Scientific notation |

Metric prefix | Logic | |||

| Prefix | Symbol | Prefix | Symbol | |||||

| Million | 106 | Mega | M | 1,000×1,0001 | 106 | Mega | M | 1,000,0001 |

| Billion | 109 | Giga | G | 1,000×1,0002 | 1012 | Tera | T | 1,000,0002 |

| Trillion | 1012 | Tera | T | 1,000×1,0003 | 1018 | Exa | E | 1,000,0003 |

| Quadrillion | 1015 | Peta | P | 1,000×1,0004 | 1024 | Yotta | Y | 1,000,0004 |

| Etc. | To go from one named order of magnitude to the next: multiply by 1,000 |

To go from one named order of magnitude to the next: multiply by 1,000,000 | ||||||

The root mil in "million" does not refer to the numeral "one". The word million derives from the Old French milion from the earlier Old Italian milione, an intensification of the Latin word mille, a thousand. That is, a million is a "big thousand", much as a "great gross" is a dozen gross or 1728.[12]

The word milliard, or its translation, is found in many European languages and is used in those languages for 109. However, it is unknown in American English, which uses billion, and not used in British English, which preferred to use thousand million before the current usage of billion. The financial term yard, which derives from milliard, is used on financial markets, as, unlike the term billion, it is internationally unambiguous and phonetically distinct from million. Likewise, many long scale countries use the word billiard (or similar) for a thousand long scale billions (i.e. 1015), and the word trilliard (or similar) for a thousand long scale trillions (i.e. 1021), etc.[13][14][15][16][17]

History

The existence of the different scales means that care must be taken when comparing large numbers between languages or countries, or when interpreting old documents in countries where the dominant scale has changed over time. For example, British-English, French, and Italian historical documents can refer to either the short or long scale, depending on the date of the document, since each of the three countries has used both systems at various times in its history. Today, the United Kingdom officially uses the short scale, but France and Italy use the long scale.

The pre-1974 former British English word billion, post-1961 current French word billion, post-1994 current Italian word bilione, German Billion; Dutch biljoen; Swedish biljon; Finnish biljoona; Danish billion; Polish bilion, Spanish billón; Slovenian bilijon and the European Portuguese word bilião (with an alternate spelling to the Brazilian Portuguese variant, but in Brazil referring to short scale) all refer to 1012, being long-scale terms. Therefore, each of these words translates to the American English or post-1974 modern British English word: trillion (1012 in the short scale), and not billion (109 in the short scale).

On the other hand, the pre-1961 former French word billion, pre-1994 former Italian word bilione, Brazilian Portuguese word bilhão and the Welsh word biliwn all refer to 109, being short scale terms. Each of these words translates to the American English or post-1974 modern British English word billion (109 in the short scale).

The terms billion and milliard both originally meant 1012 when introduced.[12]

- In long scale countries, milliard was redefined down to its current value of 109, leaving billion at its original 1012 value and so on for the larger numbers.[12] Some of these countries, but not all, introduced new words billiard, trilliard, etc. as intermediate terms.[13][14][15][16][17]

- In some short scale countries, milliard was redefined down to 109 and billion dropped altogether, with trillion redefined down to 1012 and so on for the larger numbers.[12]

- In many short scale countries, milliard was dropped altogether and billion was redefined down to 109, adjusting downwards the value of trillion and all the larger numbers.

- Timeline

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1200s | The word million was not used in any language before the 13th century. Maximus Planudes (c. 1260–1305) was among the first recorded users.[12] |

| Late 1300s |

Translation:

|

| 1475 | French mathematician Jehan Adam, writing in Middle French, recorded the words bymillion and trimillion as meaning 1012 and 1018 respectively in a manuscript Traicté en arismetique pour la practique par gectouers, now held in the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris.[18][19][20]

Translation:

|

| 1484 |  – an extract from Chuquet's original 1484 manuscript

Translation:

The extract from Chuquet's manuscript, the transcription and translation provided here all contain an original mistake: one too many zeros in the 804300 portion of the fully written out example: 745324'8043000 '700023'654321 ... |

| 1514 |

Translation:

|

| 1549 | The influential French mathematician Jacques Pelletier du Mans used the name milliard (or milliart), attributing this meaning to the earlier usage by Guillaume Budé[24] |

| 1600s | With the increased usage of large numbers, the traditional punctuation of large numbers into six-digit groups evolved into three-digit group punctuation. In some places, the large number names were then applied to the smaller numbers, following the new punctuation scheme. In France and Italy, some scientists then began using billion to mean 109, trillion to mean 1012, etc. This usage formed the origins of the later short scale. The majority of scientists either continued to say thousand million or changed the meaning of the Pelletier term, milliard, from "million of millions" down to "thousand million".[12] This meaning of milliard has been occasionally used in England,[3] but was widely adopted in France, Germany, Italy and the rest of Europe, for those keeping the original long scale billion from Adam, Chuquet and Pelletier. |

| 1676 | The first published use of milliard as 109 occurred in the Netherlands.[12][25]

Translation:

|

| Early 1700s | The short-scale meaning of the term billion was brought to the British American colonies |

| 1729 | The first American appearance of the short scale value of billion as 109 was published in the Greenwood Book of 1729, written anonymously by Prof. Isaac Greenwood of Harvard College[12] |

| Early 1800s | France widely converted to the short scale, and was followed by the U.S., which began teaching it in schools. Many French encyclopedias of the 19th century either omitted the long scale system or called it "désormais obsolète", a now obsolete system. Nevertheless, by the mid 20th century France had converted back to the long scale. |

| 1923 | German hyperinflation in the 1920s Weimar Republic caused 'Eintausend Mark' (1000 Mark = 103 Mark) German banknotes to be over-stamped as 'Eine Milliarde Mark' (109 Mark). This introduced large-number names to the German populace. The Mark or Papiermark was replaced at the end of 1923 by the Rentenmark at an exchange rate of: 1 Rentenmark = 1 billion (long scale) Papiermark = 1012 Papiermark = 1 trillion (short scale) Papiermark |

| 1926 |  by H. W. Fowler

Although American English usage did not change, within the next 50 years French usage changed from short scale to long and British English usage changed from long scale to short. |

| 1946 | Hyperinflation in Hungary in 1946 led to the introduction of the 1020 pengő banknote. 100 million b-pengő (long scale) = 100 trillion (long scale) pengő = 1020 pengő = 100 quintillion (short scale) pengő. On 1 August 1946, the forint was introduced at a rate of: 1 forint = 400 quadrilliard (long scale) pengő = 4 x 1029 pengő = 400 octillion (short scale) pengő. |

| 1948 | The 9th General Conference on Weights and Measures received requests to establish an International System of Units. One such request was accompanied by a draft French Government discussion paper, which included a suggestion of universal use of the long scale, inviting the short-scale countries to return or convert.[26] This paper was widely distributed as the basis for further discussion. The matter of the International System of Units was eventually resolved at the 11th General Conference in 1960. The question of long scale versus short scale was not resolved and does not appear in the list of any conference resolutions.[26][27] |

| 1960 | The 11th General Conference on Weights and Measures adopted the International System of Units (SI), with its own set of numeric prefixes.[28] SI is therefore independent of the number scale being used. SI also notes the language-dependence of some larger-number names and advises against using ambiguous terms such as billion, trillion, etc.[29] The National Institute of Standards and Technology within the USA also considers that it is best that they be avoided entirely.[30] |

| 1961 | The French Government confirmed their official usage of the long scale in the Journal officiel (the official French Government gazette).[31] |

| 1974 |  (1916–1995)

The BBC and other UK mass media quickly followed the government's lead within the UK. During the last quarter of the 20th century, most other English-speaking countries (the Republic of Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Zimbabwe, etc.) either also followed this lead or independently switched to the short scale use. However, in most of these countries, some limited long scale use persists and the official status of the short scale use is not clear. |

| 1975 | French mathematician Geneviève Guitel introduced the terms long scale (French: échelle longue) and short scale (French: échelle courte) to refer to the two numbering systems.[1][2] |

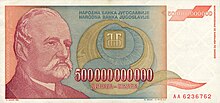

| 1993 |  Hyperinflation in Yugoslavia led to the introduction of 5 x 1011 dinar banknotes. 500 thousand million (long scale) dinars = 5 x 1011 dinar banknotes = 500 billion (short scale) dinars. The later introduction of the new dinar came at an exchange rate of: 1 novi dinar = 1 × 1027 dinars = ~1.3 × 1027 pre 1990 dinars. |

| 1994 | The Italian Government confirmed their official usage of the long scale.[17] |

| 2009 |  Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe led to banknotes of 1014 Zimbabwean dollars, marked "One Hundred Trillion Dollars" (short scale), being issued in 2009, shortly ahead of the currency being abandoned.[32][33][34] As of 2013[update], a new currency has yet to be announced – so foreign currencies are being used instead. 100 trillion (short scale) Zimbabwean dollars = 1014 Zimbabwean dollars = 100 billion (long scale) Zimbabwean dollars = 1027 pre-2006 Zimbabwean dollars. |

| 2013 | As of 24 October 2013[update], the combined total public debt of the United States stood at $17.078 trillion.[35][36]

17 trillion (short scale) US Dollars = 1.7 x 1013 US Dollars = 17 billion (long scale) US Dollars |

Current usage

Short scale users

English-speaking

- 106 = one million, 109 = one billion, 1012 = one trillion, etc.

Most English-language countries and regions use the short scale with 109 = billion. For example:[shortscale note 1]

American Samoa

American Samoa Anguilla

Anguilla Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda Australia [shortscale note 2][37]

Australia [shortscale note 2][37] Bahamas

Bahamas Barbados

Barbados Belize (English-speaking)

Belize (English-speaking) Bermuda

Bermuda Botswana (English-speaking)

Botswana (English-speaking) British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands Cameroon (English-speaking)

Cameroon (English-speaking) Cayman Islands

Cayman Islands Cook Islands

Cook Islands Dominica

Dominica Eritrea

Eritrea Ethiopia

Ethiopia Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands Fiji

Fiji Gambia

Gambia Ghana (English-speaking)

Ghana (English-speaking) Gibraltar

Gibraltar Grenada

Grenada Guam

Guam Guernsey

Guernsey Guyana (English-speaking)

Guyana (English-speaking) Hong Kong (English-speaking)

Hong Kong (English-speaking) Ireland (English-speaking, Irish: billiún, trilliún)

Ireland (English-speaking, Irish: billiún, trilliún) Isle of Man

Isle of Man Jamaica

Jamaica Jersey

Jersey Kenya (English-speaking)

Kenya (English-speaking) Kiribati

Kiribati Lesotho

Lesotho Liberia

Liberia Malawi (English-speaking)

Malawi (English-speaking) Malaysia (English-speaking; Malay: bilion billion, trilion trillion)

Malaysia (English-speaking; Malay: bilion billion, trilion trillion) Malta (English-speaking; Maltese: biljun, triljun)

Malta (English-speaking; Maltese: biljun, triljun) Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Federated States of Micronesia

Federated States of Micronesia Montserrat

Montserrat Nauru

Nauru New Zealand (English-speaking)

New Zealand (English-speaking) Nigeria (English-speaking)

Nigeria (English-speaking) Niue

Niue Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands

Northern Mariana Islands Palau

Palau Papua New Guinea (English-speaking)

Papua New Guinea (English-speaking) Philippines (English-speaking) [shortscale note 3]

Philippines (English-speaking) [shortscale note 3] Pitcairn Islands

Pitcairn Islands Rwanda

Rwanda Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa

Samoa Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Singapore (English-speaking)

Singapore (English-speaking) Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands South Sudan (English-speaking)

South Sudan (English-speaking) Eswatini

Eswatini Tanzania (English-speaking)

Tanzania (English-speaking) Tokelau

Tokelau Tonga

Tonga Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago Turks and Caicos Islands

Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu

Tuvalu Uganda (English-speaking)

Uganda (English-speaking) United Kingdom (see Wales below) [shortscale note 4][5][6][7][8][9]

United Kingdom (see Wales below) [shortscale note 4][5][6][7][8][9] United States [shortscale note 5][38][39]

United States [shortscale note 5][38][39] United States Virgin Islands

United States Virgin Islands Zambia (English-speaking)

Zambia (English-speaking) Zimbabwe (English-speaking)[32][33][34]

Zimbabwe (English-speaking)[32][33][34]

Arabic-speaking

Most Arabic-language countries and regions use the short scale with 109 = میليار milyar. For example:[shortscale note 6][40][41]

Other short scale

- 106 = one million, 109 = one milliard / billion, 1012 = one trillion, etc.

Other countries also use a word similar to trillion to mean 1012, etc. While a few of these countries like English use a word similar to billion to mean 109, most like Arabic have kept a traditional long scale word similar to milliard for 109. Some examples of short scale use, and the words used for 109 and 1012, are:

Afghanistan (Dari: میلیارد milyard or بیلیون billion, تریلیون trillion, Pashto: میلیارد milyard, بیلیون billion, تریلیون trillion)

Afghanistan (Dari: میلیارد milyard or بیلیون billion, تریلیون trillion, Pashto: میلیارد milyard, بیلیون billion, تریلیون trillion) Albania (miliard, trilion)[42]

Albania (miliard, trilion)[42] Armenia (միլիարդ miliard, տրիլիոն trilion)

Armenia (միլիարդ miliard, տրիլիոն trilion) Azerbaijan (milyard, trilyon)

Azerbaijan (milyard, trilyon) Belarus (мільярд milyard, трыльён trilyon)

Belarus (мільярд milyard, трыльён trilyon) Brazil (Brazilian Portuguese: bilhão, trilhão)

Brazil (Brazilian Portuguese: bilhão, trilhão) Brunei (Brunei Malay: ; Malay: bilion, trilion)

Brunei (Brunei Malay: ; Malay: bilion, trilion) Bulgaria (милиард miliard, трилион trilion)

Bulgaria (милиард miliard, трилион trilion) Myanmar (Burmese: ‹See Tfd›ဘီလျံ, IPA: [bìljàɴ]; ‹See Tfd›ထရီလျံ, [tʰəɹìljàɴ])[43]

Myanmar (Burmese: ‹See Tfd›ဘီလျံ, IPA: [bìljàɴ]; ‹See Tfd›ထရီလျံ, [tʰəɹìljàɴ])[43] Cyprus (Greek: δισεκατομμύριο disekatommyrio, τρισεκατομμύριο trisekatommyrio, Turkish: milyar, trilyon)

Cyprus (Greek: δισεκατομμύριο disekatommyrio, τρισεκατομμύριο trisekatommyrio, Turkish: milyar, trilyon) Estonia (miljard, triljon)[44][45]

Estonia (miljard, triljon)[44][45] Georgia (მილიარდი miliardi, ტრილიონი trilioni)

Georgia (მილიარდი miliardi, ტრილიონი trilioni) Indonesia (miliar, triliun) [shortscale note 7][46]

Indonesia (miliar, triliun) [shortscale note 7][46] Israel (Hebrew: מיליארד millyard, טריליון trillyon)

Israel (Hebrew: מיליארד millyard, טריליון trillyon) Kazakhstan (Kazakh: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion)

Kazakhstan (Kazakh: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion) Kyrgyzstan (Kyrgyz: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion)

Kyrgyzstan (Kyrgyz: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion) Latvia (miljards, triljons)

Latvia (miljards, triljons) Lithuania (milijardas, trilijonas)

Lithuania (milijardas, trilijonas) Moldova (Romanian / Moldovan: miliard, trilion; Russian: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion)

Moldova (Romanian / Moldovan: miliard, trilion; Russian: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion) Romania (miliard, trilion)

Romania (miliard, trilion) Russia (миллиард milliard, триллион trillion)

Russia (миллиард milliard, триллион trillion) Tajikistan (Tajik: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion)

Tajikistan (Tajik: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion) Turkey (milyar, trilyon)

Turkey (milyar, trilyon) Turkmenistan (Turkmen: ; Russian: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion)

Turkmenistan (Turkmen: ; Russian: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion) Ukraine (мільярд mil'yard, трильйон tryl'yon)

Ukraine (мільярд mil'yard, трильйон tryl'yon) Uzbekistan (Uzbek: ; Russian: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion)

Uzbekistan (Uzbek: ; Russian: миллиард milliard, триллион trillion) Wales (biliwn, triliwn)

Wales (biliwn, triliwn)

With other terminology

Greece (εκατομμύριο ekatommyrio "hundred-myriad" = 106; δισεκατομμύριο disekatommyrio "bi+hundred-myriad" = 109; τρισεκατομμύριο trisekatommyrio "tri+hundred-myriad" = 1012; τετράκις εκατομμύριο tetrakis ekatommyrio "quadri+hundred-myriad" = 1015, and so on.)[47]

Greece (εκατομμύριο ekatommyrio "hundred-myriad" = 106; δισεκατομμύριο disekatommyrio "bi+hundred-myriad" = 109; τρισεκατομμύριο trisekatommyrio "tri+hundred-myriad" = 1012; τετράκις εκατομμύριο tetrakis ekatommyrio "quadri+hundred-myriad" = 1015, and so on.)[47]

Long scale users

The traditional long scale is used by most Continental European countries and by most other countries whose languages derive from Continental Europe (with the notable exceptions of Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, and Brazil). These countries use a word similar to billion to mean 1012. Some use a word similar to milliard to mean 109, while others use a word or phrase equivalent to thousand millions.

Spanish-speaking

- 106 = millón, 109 = mil millones or millardo, 1012 = billón, etc.

Most Spanish-language countries and regions use the long scale with 109 = mil millones, for example:[longscale note 1][48][49]

Argentina

Argentina  Bolivia

Bolivia  Chile

Chile  Colombia

Colombia  Costa Rica

Costa Rica  Cuba

Cuba  Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic  Ecuador

Ecuador  El Salvador

El Salvador  Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea  Guatemala (millardo)

Guatemala (millardo) Honduras (millardo)

Honduras (millardo) Mexico (mil millones or millardo)

Mexico (mil millones or millardo) Nicaragua (mil millones or millardo)

Nicaragua (mil millones or millardo) Panama (mil millones or millardo)

Panama (mil millones or millardo) Paraguay

Paraguay  Peru

Peru  Spain (millardo or typ. mil millones)

Spain (millardo or typ. mil millones) Uruguay

Uruguay  Venezuela

Venezuela

French-speaking

Most French-language countries and regions use the long scale, for example:[longscale note 2][50][51]

Portuguese-speaking

- 106 = milhão, 109 = mil milhões or milhar de milhões, 1012 = bilião

With the notable exception of Brazil, a short scale country, most Portuguese-language countries and regions use the long scale, for example:

Dutch-speaking

Most Dutch-language countries and regions use the long scale, for example:[52][53]

Other long scale

- 106 = one million, 109 = one milliard / thousand million, 1012 = one billion, 1015 = one billiard / thousand billion, 1018 = one trillion, etc.

Some examples of long scale use, and the words used for 109 and 1012, are:

Andorra (Catalan: miliard or typ. mil milions, bilió)

Andorra (Catalan: miliard or typ. mil milions, bilió) Austria (Austrian German: Milliarde, Billion)

Austria (Austrian German: Milliarde, Billion) Belgium (Belgian French: milliard, billion; Flemish: miljard, biljoen; German: Milliarde, Billion)

Belgium (Belgian French: milliard, billion; Flemish: miljard, biljoen; German: Milliarde, Billion) Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnian: milijarda, bilion; Croatian: milijarda, bilijun, Serbian: милијарда milijarda, билион bilion)

Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnian: milijarda, bilion; Croatian: milijarda, bilijun, Serbian: милијарда milijarda, билион bilion) Croatia (milijarda, bilijun)

Croatia (milijarda, bilijun) Czech Republic (miliarda, bilion)

Czech Republic (miliarda, bilion) Denmark (milliard, billion)

Denmark (milliard, billion) Faroe Islands (Danish: milliard, billion)

Faroe Islands (Danish: milliard, billion) Finland (Finnish: miljardi, biljoona; Swedish: miljard, biljon)

Finland (Finnish: miljardi, biljoona; Swedish: miljard, biljon) Germany (Milliarde, Billion)[13][14]

Germany (Milliarde, Billion)[13][14] Hungary (milliárd, billió or ezer milliárd)

Hungary (milliárd, billió or ezer milliárd) Iceland (milljarður, billjón)

Iceland (milljarður, billjón) Iran (Persian: میلیارد milyard, بیلیون billion, تریلیون trillion) [citation needed]

Iran (Persian: میلیارد milyard, بیلیون billion, تریلیون trillion) [citation needed] Italy (miliardo, bilione) [longscale note 3][17][54]

Italy (miliardo, bilione) [longscale note 3][17][54] Liechtenstein (German: Milliarde, Billion)

Liechtenstein (German: Milliarde, Billion) Luxembourg (French: milliard, billion; German: Milliarde, Billion; Luxembourgish: milliard, billioun)

Luxembourg (French: milliard, billion; German: Milliarde, Billion; Luxembourgish: milliard, billioun) North Macedonia (милијарда milijarda, билион bilion)

North Macedonia (милијарда milijarda, билион bilion) Madagascar (French: milliard, billion; Malagasy: )

Madagascar (French: milliard, billion; Malagasy: ) Montenegro (Montenegrin: milijarda, bilion)

Montenegro (Montenegrin: milijarda, bilion) Norway (Bokmål: milliard, billion; Nynorsk: milliard, billion)

Norway (Bokmål: milliard, billion; Nynorsk: milliard, billion) Poland (miliard, bilion)

Poland (miliard, bilion) San Marino (Italian: miliardo, bilione)

San Marino (Italian: miliardo, bilione) Serbia (милијарда milijarda, билион bilion)

Serbia (милијарда milijarda, билион bilion) Slovakia (miliarda, bilión)

Slovakia (miliarda, bilión) Slovenia (milijarda, bilijon)

Slovenia (milijarda, bilijon) Sweden (miljard, biljon)

Sweden (miljard, biljon) Switzerland (French: milliard, billion; German: Milliarde, Billion; Italian: miliardo, bilione, Romansh: milliarda, billiun[55] )

Switzerland (French: milliard, billion; German: Milliarde, Billion; Italian: miliardo, bilione, Romansh: milliarda, billiun[55] ) Vatican City (Italian: miliardo, bilione)

Vatican City (Italian: miliardo, bilione)

- Other long scale languages

Esperanto language (miliardo, duiliono) [longscale note 4][56]

Esperanto language (miliardo, duiliono) [longscale note 4][56]

Using both

Some countries use either the short or long scales, depending on the internal language being used or the context.

- 106 = one million, 109 = EITHER one billion (short scale) OR one milliard / thousand million (long scale), 1012 = EITHER one trillion (short scale) OR one billion (long scale), etc.

| Country or Territory | Short scale usage | Long scale usage |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian English (109 = billion, 1012 = trillion) | Canadian French (109 = milliard, 1012 = billion). | |

| English (109 = billion, 1012 = trillion) | French (109 = milliard, 1012 = billion) | |

| South African English (109 = billion, 1012 = trillion) | Afrikaans (109 = miljard, 1012 = biljoen) | |

| Economic & technical (109 = billón, 1012 = trillón) | Latin American export publications (109 = millardo or mil millones, 1012 = billón) |

Using neither

The following countries have their own numbering systems and use neither short nor long scales:

| Country | Main article | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Numbering System | For everyday use, but short or long scale may also be in use [other scale note 1] | |

| Dzongkha numerals | Traditional system | |

| Khmer numerals | Traditional system | |

| Chinese numerals | Traditional myriad system for the larger numbers; special words and symbols up to 1088 | |

| Inuit numerals | Traditional system | |

| Japanese numerals | Traditional myriad system for the larger numbers; special words and symbols up to 1088 | |

| Korean numerals | Traditional myriad system for the larger numbers; special words and symbols up to 1088 | |

| Lao numerals | Traditional system | |

| Traditional systems | ||

| Mongolian numerals | Traditional myriad system for the larger numbers; special words up to 1067 | |

| Thai numerals | Traditional system based on millions | |

| Vietnamese numerals | Traditional system(s) based on thousands |

- Presence on most continents

The long and short scales are both present on most continents, with usage dependent on the language used. Examples include:

| Continent | Short scale usage | Long scale usage |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | Arabic (Egypt, Libya, Tunisia), English (South Sudan), South African English | Afrikaans, French (Benin, Central African Republic, Gabon, Guinea), Portuguese (Mozambique) |

| North America | American English, Canadian English | U.S. Spanish, Canadian French, Mexican Spanish |

| South America | Brazilian Portuguese, English (Guyana) | American Spanish, Dutch (Suriname), French (French Guiana) |

| Antarctica | Australian English, British English, New Zealand English | American Spanish (Argentina, Chile), French (France), Norwegian (Norway) |

| Asia | Burmese (Myanmar), Hebrew (Israel), Indonesian, Malaysian English, Persian (Iran), Philippine English, | Portuguese (East Timor, Macau) |

| Europe | British English, Hiberno-English, Scottish English, Welsh English, Welsh, Bulgarian, Estonian, Greek, Latvian, Lithuanian, Turkish, Ukrainian | Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Icelandic, Italian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Swedish and most other languages of continental Europe |

| Oceania | Australian English, New Zealand English | French (French Polynesia) |

Notes on current usage

- Short scale

- ^ English language countries: Apart from the United States, the long scale was used for centuries in many English language countries before being superseded in recent times by short scale usage. Because of this history, some long scale use persists[11] and the official status of the short scale in anglophone countries other than the UK and US is sometimes obscure.[citation needed]

- ^ Australian usage: In Australia, education, media outlets, and literature all use the short scale in line with other English-speaking countries. The current recommendation by the Australian Government Department of Finance and Deregulation (formerly known as AusInfo), and the legal definition, is the short scale.[37] As recently as 1999, the same department did not consider short scale to be standard, but only used it occasionally. Some documents use the term thousand million for 109 in cases where two amounts are being compared using a common unit of one 'million'.

- ^ Filipino usage: Some short-scale words have been adopted into Filipino.

- ^ British usage: Billion has meant 109 in most sectors of official published writing for many years now. The UK government, the BBC, and most other broadcast or published mass media, have used the short scale in all contexts since the mid-1970s.[5][6][7][8]

Before the widespread use of billion for 109, UK usage generally referred to thousand million rather than milliard.[9] The long scale term milliard, for 109, is obsolete in British English, though its derivative, yard, is still used as slang in the London money, foreign exchange, and bond markets. - ^ American usage: In the United States of America, the short scale has been taught in school since the early 19th century. It is therefore used exclusively.[38][39]

- ^ Arabic language countries: Most Arabic-language countries use: 106 = میليون million, 109 = میليار milyar, 1012 = تريليون trilyon, etc.[40][41]

- ^ Indonesian usage: Large numbers are common in Indonesia, in part because its currency (rupiah) is generally expressed in large numbers (the lowest common circulating denomination is Rp100 with Rp1000 is considered as base unit). The term juta, equivalent to million (106), is generally common in daily life. Indonesia officially employs the term miliar (derived from the long scale Dutch word miljard) for the number 109, with no exception. For 1012 and greater, Indonesia follows the short scale, thus 1012 is named triliun. The term seribu miliar (a thousand milliards) or more rarely sejuta juta (a million millions) are also used for 1012 less often. Terms greater than triliun are not very familiar to Indonesians.[46]

- Long scale

- ^ Spanish language countries: Spanish-speaking countries sometimes use millardo (milliard)[48] for 109, but mil millones (thousand millions) is used more frequently. The word billón is sometimes used in the short scale sense in those countries more influenced by the United States, but this is considered unacceptable.[49]

- ^ French usage: France, with Italy, was one of two European countries which converted from the long scale to the short scale during the 19th century, but returned to the original long scale during the 20th century. In 1961, the French Government confirmed their long scale status.[31][50][51]

- ^ Italian usage: Italy, with France, was one of the two European countries which partially converted from the long scale to the short scale during the 19th century, but returned to the original long scale in the 20th century. In 1994, the Italian Government confirmed its long scale status.[17]

In Italian, the word bilione officially means 1012, trilione means 1018, etc.. Colloquially, bilione[54] can mean both 109 and 1012; trilione [citation needed] can mean both 1012 and (rarer) 1018 and so on. Therefore, in order to avoid ambiguity, they are seldom used. Forms such as miliardo (milliard) for 109, mille miliardi (a thousand milliards) for 1012, un milione di miliardi (a million milliards) for 1015, un miliardo di miliardi (a milliard of milliards) for 1018, mille miliardi di miliardi (a thousand milliard of milliards) for 1021 are more common.[17] - ^ Esperanto language usage: The Esperanto language words biliono, triliono etc. used to be ambiguous, and both long or short scale were used and presented in dictionaries. The current edition of the main Esperanto dictionary PIV however recommends the long scale meanings, as does the grammar PMEG.[56] Ambiguity may be avoided by the use of the unofficial but generally recognised suffix -iliono, whose function is analogous to the long scale, i.e. it is appended to a (single) numeral indicating the power of a million, e.g. duiliono (from du meaning "two") = biliono = 1012, triiliono = triliono = 1018, etc. following the 1×106X long scale convention. Miliardo is an unambiguous term for 109, and generally the suffix -iliardo, for values 1×106X+3, for example triliardo = 1021 and so forth.

- Both long and short scale

- ^ Canadian usage: Both scales are in use currently in Canada. English-speaking regions use the short scale exclusively, while French-speaking regions use the long scale.[57]

- ^ South African usage: South Africa uses both the long scale (in Afrikaans and sometimes English) and the short scale (in English). Unlike the 1974 UK switch, the switch from long scale to short scale took time. As of 2011[update] most English language publications use the short scale. Some Afrikaans publications briefly attempted usage of the "American System" but that has led to comment in the papers[58] and has been disparaged by the "Taalkommissie" (The Afrikaans Language Commission of the South African Academy of Science and Art)[59] and has thus, to most appearances, been abandoned.

- Neither long nor short scale

- ^ Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi usage: Outside of financial media, the use of billion by Bangladeshi, Indian and Pakistani English speakers highly depends on their educational background. Some may continue to use the traditional British long scale. In everyday life, Bangladeshis, Indians and Pakistanis largely use their own common number system, commonly referred to as the Indian numbering system – for instance, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Indian English commonly use the words lakh to denote 100 thousand, crore to denote ten million (i.e. 100 lakhs) and arab to denote thousand million.[60]

Alternative approaches

Unambiguous ways of identifying large numbers include:

- In written communications, the simplest solution for moderately large numbers is to write the full amount, for example 1,000,000,000,000 rather than, say, 1 trillion (short scale) or 1 billion (long scale).

- Combinations of the unambiguous word million, for example: 109 = "one thousand million"; 1012 = "one million million". This becomes rather unwieldy for numbers above 1012.

- Combination of numbers of more than 3 digits with the unambiguous word million, for example 13,600 million[61]

- Scientific notation (also known as standard form or exponential notation, for example 1×109, 1×1010, 1×1011, 1×1012, etc.), or its engineering notation variant (for example 1×109, 10×109, 100×109, 1×1012, etc.), or the computing variant E notation (for example

1e9,1e10,1e11,1e12, etc.) This is the most common practice among scientists and mathematicians, and is both unambiguous and convenient. - SI prefixes in combination with SI units, for example, giga for 109 and tera for 1012 can give gigawatt (=109 W) and terawatt (=1012 W), respectively. The International System of Units (SI) is independent of whichever scale is being used.[28] Use with non-SI units (e.g. "giga-dollars", "giga-miles") is uncommon.

See also

- Googol (number)

- Googolplex (number)

- Names of large numbers

- Names of small numbers

- Orders of magnitude (numbers)

- Hindu units of time which displays some similar issues

References

- ^ a b c d e Guitel, Geneviève (1975). Histoire comparée des numérations écrites (in French). Paris: Flammarion. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-2-08-211104-1.

- ^ a b c d e Guitel, Geneviève (1975). Histoire comparée des numérations écrites (in French). Paris: Flammarion. pp. 566–574 Chapter: "Les grands nombres en numération parlée (État actuel de la question)", i.e. "The large numbers in oral numeration (Present state of the question)" . ISBN 978-2-08-211104-1.

- ^ a b c d

Fowler, H. W. (1926). A Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-19-860506-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ British-English usage of 'Billion vs Thousand million vs Milliard'. Google Inc. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d ""BILLION" (DEFINITION) – HC Deb 20 December 1974 vol 883 cc711W-712W". Hansard Written Answers. Hansard. 20 December 1974. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ a b c d

O'Donnell, Frank (30 July 2004). "Britain's £1 trillion debt mountain – How many zeros is that?". The Scotsman. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c "BBC News: Who wants to be a trillionaire?". BBC. 7 May 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ a b c

Comrie, Bernard (24 March 1996). "billion:summary". Linguist List (Mailing list). Retrieved 24 July 2011.

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c

"Oxford Dictionaries: How many is a billion?". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

"Oxford Dictionaries: Billion". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

Nielsen, Ron (2006). The Little Green Handbook. Macmillan Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-312-42581-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i

Smith, David Eugene (1925 republished 1953). History of Mathematics. Vol. II. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-0-486-20430-7.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c

"Wortschatz-Lexikon: Milliarde" (in German). Universität Leipzig: Wortschatz-Lexikon. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c

"Wortschatz-Lexikon: Billion" (in German). Universität Leipzig: Wortschatz-Lexikon. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Wortschatz-Lexikon: Billiarde" (in German). Universität Leipzig: Wortschatz-Lexikon. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Wortschatz-Lexikon: Trilliarde" (in German). Universität Leipzig: Wortschatz-Lexikon. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f

"Direttiva CEE / CEEA / CE 1994 n. 55, p.12" (PDF) (in Italian). Italian Government. 21 November 1994. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Adam, Jehan (1475). "Traicté en arismetique pour la practique par gectouers... (MS 3143)" (in Middle French). Paris: Bibliothèque Sainte-GenevièveTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "HOMMES DE SCIENCE, LIVRES DE SAVANTS A LA BIBLIOTHÈQUE SAINTE-GENEVIÈVE, Livres de savants II". Traicté en arismetique pour la practique par gectouers… (in French). Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. 2005. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^

Thorndike, Lynn. "The Arithmetic of Jehan Adam, 1475 A.D". The American Mathematical Monthly. 1926 (January). Mathematical Association of America: 24. JSTOR 2298533.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

Chuquet, Nicolas (written 1484, published 1880). "Le Triparty en la Science des Nombres par Maistre Nicolas Chuquet Parisien". Bulletino di Bibliographia e di Storia delle Scienze matematische e fisische (in Middle French). XIII (1880). Bologna: Aristide Marre: 593–594. ISSN 1123-5209. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Chuquet, Nicolas (written 1484, published 1880). "Le Triparty en la Science des Nombres par Maistre Nicolas Chuquet Parisien" (in Middle French). www.miakinen.net. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Flegg, Graham (23–30 December 1976). "Tracing the origins of One, Two, Three". New Scientist. 72 (1032). Reed Business Information: 747. ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

Budaeus (1514). De Asse et partibus eius Libri quinque (in Latin) (Paris (1532) ed.). pp. folio 95, v.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Houck (1676). "Arithmetic". Netherlands: 2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b

"Resolution 6 of the 9th meeting of the CGPM (1948)". BIPM. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

"Resolution 6 of the 10th meeting of the CGPM (1954)". BIPM. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Resolution 12 of the 11th meeting of the CGPM (1960)". BIPM. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8 ed.). BIPM. May 2006. pp. 134 / 5.3.7 Stating values of dimensionless quantities, or quantities of dimension one. ISBN 92-822-2213-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Thompson, Ambler; Taylor, Barry N. (30 March 2008). Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI), NIST SP - 811. USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 21. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ a b

"Décret 61-501" (PDF). Journal Officiel (in French). French Government: page 4587 note 3a, and erratum on page 7572. commissioned 1961-05-03 published 1961-05-20 modified 1961-08-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"BBC News: Zimbabweans play the zero game". BBC. 23 July 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"BBC News: Zimbabwe rolls out Z$100tr note". BBC. 16 January 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"BBC News: Zimbabwe abandons its currency". BBC. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Debt to the Penny "The Debt to the Penny and Who Holds It". www.treasurydirect.gov. US Government. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Economic infographics". demonocracy.info. BTC. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ a b

"RBA: Definition of billion". Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Cambridge Dictionaries Online: billion". American Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Cambridge Dictionaries Online: trillion". American Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Al Jazem English-Arabic online dictionary: Billion". Al Jazem English-Arabic online dictionary. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|work= - ^ a b

"Al Jazem English-Arabic online dictionary:Trillion". Al Jazem English-Arabic online dictionary. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Qeli, Albi. "An English-Albanian Dictionary". An English-Albanian Dictionary. Albi Qeli, MD. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|publisher=and|work= - ^

"Britain to Reduce $4 billion from Defence". Bi-Weekly Eleven (in Burmese). 3 (30). Yangon. 15 October 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Eesti õigekeelsussõnaraamat ÕS 2006: miljard" (in Estonian). Institute of the Estonian Language (Eesti Keele Instituut). 2006. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Eesti õigekeelsussõnaraamat ÕS 2006: triljon" (in Estonian). Institute of the Estonian Language (Eesti Keele Instituut). 2006. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Robson S. O. (Stuart O.), Singgih Wibisono, Yacinta Kurniasih. Javanese English dictionary Tuttle Publishing: 2002, ISBN 0-7946-0000-X: 821 pages

- ^

Foundalis, Harry. "Greek Numbers and Numerals (Ancient and Modern)". Retrieved 20 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas: millardo" (in Spanish). Real Academia Española. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas: billon" (in Spanish). Real Academia Española. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "French Larousse: milliard" (in French). Éditions Larousse. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "French Larousse: billion" (in French). Éditions Larousse. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "De Geïntegreerde Taal-Bank: miljard" (in Dutch). Instituut voor Nederlandse Lexicologie. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ "De Geïntegreerde Taal-Bank: biljoen" (in Dutch). Instituut voor Nederlandse Lexicologie. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "Italian-English Larousse: bilione". Éditions Larousse. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Switzerland: Words and Phrases". TRAMsoft Gmbh. 29 August 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Wennergren, Bertilo (8 March 2008). "Plena Manlibro de Esperanta Gramatiko" (in Esperanto). Retrieved 15 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

"Canadian government standards website". Canadian Government. 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Taalkommissie se reaksie op biljoen, triljoen" (in Afrikaans). Naspers: Media24. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "'Groen boek': mooiste, beste, gebruikersvriendelikste" (in Afrikaans). Naspers:Media24. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^

Gupta, S.V. (2010). Units of measurement: past, present and future : international system of units. Springer. pp. 12 (Section 1.2.8 Numeration). ISBN 3642007384. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

"BBC: GCSE Bitesize – The origins of the universe". BBC. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links