Mariology

Mariology is the theological study of Mary, the mother of Jesus. Mariology methodically presents teachings about her to other parts of the faith, such as teachings about Jesus, redemption and grace. Christian Mariology aims to connect scripture, tradition and the teachings of the Church on Mary.[3][4][5] In the context of social history, Mariology may be broadly defined as the study of devotion to and thinking about Mary throughout the history of Christianity.[6]

There exist a variety of Christian views on Mary ranging from the focus on Marian veneration in Roman Catholic Mariology to Protestant objections, with Anglican Marian theology in between. As a field of theology, in recent centuries the most substantial developments in Mariology (and the founding of specific centers devoted to its study) have taken place within Roman Catholic Mariology. Eastern Orthodox concepts of Mary have been mostly expressed in liturgy and are not subject to a central dogmatic teaching office.

A significant number of Marian publications were written in the 20th century, with theologists Raimondo Spiazzi and Gabriel Roschini achieving 2500 and 900 publications respectively. In terms of popular following, membership in Roman Catholic Marian Movements and Societies has grown significantly. Ecumenical differences continue to exist in substance and style but are more easily understood because of the existence of Mariology. The Pontifical Academy of Mary and the Pontifical Theological Faculty Marianum are key Mariological centers.

Diversity of Marian views

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Mariology |

|---|

|

| General perspective |

| Specific views |

|

|

| Prayers and devotions |

| Ecumenical |

|

|

A wide range of views on Mary exist at multiple levels of differentiation within distinct Christian belief systems. In many cases, the views held at any point in history have continued to be challenged and transformed. Over the centuries, Roman Catholic Mariology has been shaped by varying forces ranging from sensus fidelium to Marian apparitions to the writings of the saints to reflection by theologians and papal encyclicals.

Anglican Marian theology varies greatly, from the Anglo-Catholic (very close to Roman Catholic views) to the more typically Protestant Evangelical views. The Anglican Church formally celebrates six Marian feasts, Annunciation (March 25), Visitation (May 31), Day of Saint Mary (Assumption or dormition) (August 15), Nativity of Mary (September 8), Our Lady of Walsingham (October 15) and Mary's Conception (December 8).[7][8] Anglicans generally share some of the fundamental Marian beliefs such as divine maternity and the virgin birth of Jesus, although there is no systematic agreed upon Mariology among the diverse parts of the Anglican Communion. However, the role of Mary as a mediator is accepted by some groups of modern Anglican theologians.[9]

Eastern Orthodox theology calls Mary the Theotokos, which means God-bearer. This term emphasizes Mary's status as the mother of God incarnate in Jesus but not the mother of God from eternity. The virginal motherhood of Mary stands at the center of Orthodox Mariology, in which the title Ever Virgin is often used. The Orthodox Mariological approach emphasizes the sublime holiness of Mary, her share in redemption and her role as a mediator of grace.[10][11]

Orthodox Marilogical thought dates as far back as Saint John Damascene who in the 8th century wrote on the mediative role of Mary and on the Dormition of the Theotokos.[12][13] In the 14th century, Orthodox Mariology began to flourish among Byzantine theologians who held a cosmic view of Mariology, placing Jesus and Mary together at the center of the cosmos and saw them as the goal of world history.[10] More recently Orthodox Mariology achieved a renewal among 20th century theologians in Russia, for whom Mary is the heart of the Church and the center of creation.[10] However, unlike the Catholic approach, Orthodox Mariology does not support the Immaculate Conception of Mary.[10] Prior to the 20th century, Orthodox Mariology was almost entirely liturgical, and had no systematic presentation similar to Roman Catholic Mariology. However, 20th century theologians such as Sergei Bulgakov began the development of a detailed systematic Orthodox Mariology.[14][15][16] Bulgakov's Mariological formulation emphasizes the close link between Mary and the Holy Spirit in the mystery of the Incarnation.[11]

Protestant views of Mary vary from denomination to denomination. They focus generally on interpretations of Mary in the Bible, the "Apostles' Creed", (which professes the Virgin Birth), and the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus, in 431, which called Mary the Mother of God. While some early Protestants created Marian art and allowed limited forms of Marian veneration,[17] Protestants today do not share the veneration of Mary practiced by Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox.[5] Martin Luther's views on Mary, John Calvin's views on Mary, Karl Barth's views on Mary and others have all contributed to modern Protestant views.

A better mutual understanding among different Christian groups regarding their Mariology has been sought in a number of ecumenical meetings which produced common documents.

Outside Christianity, the Islamic view of the Virgin Mary, known as Maryam in Arabic, is that she was an extremely pious and chaste woman who miraculously gave birth while still a virgin to the prophet Jesus, known in Arabic as Isa. Mary is the only woman specifically named in the Qur'an. The nineteenth chapter of the Qur'an, which is named after her, begins with two narrations of "miraculous birth".

Development of Mariology

The First Council of Ephesus in 431 formally approved devotion to the Virgin as Theotokos, which most accurately translated means God-bearer;[18][19] its use implies that Jesus, to whom Mary gave birth, is God. Nestorians preferred Christotokos meaning "Christ-bearer" or "Mother of the Messiah" not because they denied Jesus' divinity, but because they believed that God the Son or Logos existed before time and before Mary, and that Jesus took divinity from God the Father and humanity from his mother, so calling her "Mother of God" was confusing and potentially heretical. Others at the council believed that denying the Theotokos title would carry with it the implication that Jesus was not divine.

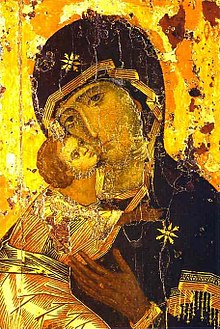

The council of Ephesus also approved the creation of icons bearing the images of the Virgin and Child. Devotion to Mary was, however, already widespread before this point, reflected in the fresco depictions of Mother and Child in the Roman catacombs. The early Church Fathers saw Mary as the "new Eve" who said "yes" to God as Eve had said no.[20] Mary, as the first Christian Saint and Mother of Jesus, was deemed to be a compassionate mediator between suffering mankind and her son, Jesus, who was seen as King and Judge.

In the East, devotion to Mary blossomed in the sixth century under official patronage and imperial promotion at the Court of Constantinople.[21] The popularity of Mary as an individual object of devotion, however, only began in the fifth century with the appearance of apocryphal versions of her life, interest in her relics, and the first churches dedicated to her name, for example, S. Maria Maggiore in Rome.[22] A sign that the process was slower in Rome is provided by the incident during the visit of Pope Agapetus to Constantinople in 536, when he was upbraided for opposing the veneration of the theotokos and refusing to allow her icons to be displayed in Roman churches.[23][failed verification] Early seventh-century examples of new Marian dedications in Rome are the dedication in 609 of the pagan Pantheon as Santa Maria ad Martyres, "Holy Mary and the Martyrs",[24] and the re-dedication of the early Christian titulus Julii et Calixtii, one of the oldest Roman churches, as Santa Maria in Trastevere.[25] The earliest Marian feasts were introduced into the Roman liturgical calendar by Pope Sergius I (687-701).[26]

During the Middle Ages, devotion to the Virgin Mary as the "new Eve" lent much to the status of women. Women who had been looked down upon as daughters of Eve, came to be looked upon as objects of veneration and inspiration. The medieval development of chivalry, with the concept of the honor of a lady and the ensuing knightly devotion to it, not only derived from the thinking about the Virgin Mary, but also contributed to it.[27] The medieval veneration of the Virgin Mary was contrasted by the fact that ordinary women, especially those outside aristocratic circles, were looked down upon. Although women were at times viewed as the source of evil, it was Mary who as mediator to God was a source of refuge for man. The development of medieval Mariology and the changing attitudes towards women paralleled each other and can best be understood in a common context.[28]

Since the Reformation, some Protestants accuse Roman Catholics of having developed an un-Christian adoration and worship of Mary, described as Marianism or Mariolatry, and of inventing non-scriptual doctrines which give Mary a semi-divine status. They also attack titles such as Queen of Heaven, Our Mother in Heaven, Queen of the World, or Mediatrix.

Since the writing of the apocryphal Protevangelium of James, various beliefs have circulated concerning Mary's own conception, which eventually led to the Roman Catholic Church dogma, formally established in the 19th century, of Mary's Immaculate Conception, which exempts her from original sin.

Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox teaching also extends to the end of Mary's life ending with the Assumption of Mary, formally established as dogma in 1950, and the Dormition of the Theotokos respectively.

Mariology as a theological discipline

| Part of a series on the |

| Mariology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

|

Within Anglican Marian theology the Blessed Virgin Mary holds a place of honour. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, a number of traditions revolve around the Ever-Virgin Mary and the Theotokos, which are theologically paramount.

Yet, as an active theological discipline, Mariology has received the larger amount of formal attention in Roman Catholic Mariology based on four dogmas on Mary which are a part of Roman Catholic theology. The Second Vatican Council document Lumen gentium summarized the views on Roman Catholic Mariology, the focus being on the veneration of the Mother of God. Over time, Roman Catholic Mariology also received some input from Liberation Theology, which emphasized popular Marian piety, and more recently from feminist theology, which stressed both the dignity of women and gender differences.

While systematic Marian theology is not new, Pope Pius XII is credited with promoting the independent theological study of Mary on a large scale with the creation or elevation of four papal Mariological research centres, e.g. the Marianum.[29] The papal institutes were created to foster Mariological research and to explain and support the Roman Catholic veneration of Mary. This new orientation was continued by Popes John XXIII, Paul VI and John Paul II with the additional creation of Pontifica Academia Mariana Internationale and Centro di Cultura Mariana, a pastoral center to promulgate Marian teachings of the Church, and, Societa Mariologica Italiana, an Italian mariological society with interdisciplinary orientation.

Mariology and theology

There are two distinct approaches to how Mariology interacts with the conventional theological treatises: should Marian perspectives and aspects be inserted into the conventional treatises, or should they be an independent presentation?[30] The first approach was followed by the Church Fathers and in the Middle Ages, although some issues were treated separately. This method has the advantage that it avoids isolating Mariology from the rest of theology. The disadvantage of this method is that it cannot see Mary in the fullness of her role and her person, and the inherent connections between various Mariological assertions can not be highlighted in it.[30] The second method has the disadvantage that it can be the victim of isolation and at times overstep its theological boundaries. However, these problems can be avoided in the second approach if specific references are made in each case to connect it to the processes of salvation, redemption, etc.[30]

Mariological methodology

As a field of study, Mariology uses the sources, methods and criteria of theology, going back to official Marian pronouncements beginning with the Apostles' Creed. In Mariology the question of scriptural basis is more accentuated.[31] In Roman Catholic Mariology, the overall context of Catholic doctrines and other Church teachings are also taken into account. The Marian Chapter of the document Lumen gentium of Vatican II includes twenty-six biblical references. They refer to the conception, birth and childhood of Jesus, Mary’s role in several events and under the cross. Of importance to Mariological methodology is a specific Vatican II statement that these reports are not allegories with symbolic value but historical revelations, a point further emphasized by Pope Benedict XVI.[32]

Organization of Mariology

The presentation of Mariology differs among theologians. Some prefer to present its historical development, while others divide Mariology by its content (dogmas, grace, role in redemption, etc.). Some theologians prefer to present Mariology only in terms of Mary's attributes (honour, titles, privileges), while others attempt to integrate Mary into their overall theology and into the salvation mystery of Jesus Christ.[33]

Some prominent theologians, such as Karl Barth and Karl Rahner in the 20th century, viewed Mariology only as a part of Christology. But differences exist even within families, e.g. Hugo Rahner, the brother of Karl Rahner, disagreed and developed a Mariology based on the writers of the early Church, such as Ambrose of Milan, Augustine of Hippo, and others.[34] He viewed Mary as the mother and model for the Church, a view later highlighted by Popes Paul VI through Benedict XVI.[35]

Relation to other theological disciplines

Mariology and Christology

While Christology has been the subject of detailed study, some Marian views, in particular in Roman Catholic Mariology, see it as an essential basis for the study of Mary. Generally, Protestant denominations do not agree with this approach.

The concept that by being the “Mother of God”, Mary has a unique role in salvation and redemption was contemplated and written about in the early Church.[36] In recent centuries, Roman Catholic Mariology has come to be viewed as a logical and necessary consequence of Christology: Mary contributes to a fuller understanding of who Christ is and what he did. In these views, Mariology can be derived from the Christocentric mysteries of Incarnation: Jesus and Mary are son and mother, redeemer and redeemed.[37][38][39]

Biblical research

Mariology participates in and benefits from biblical research, employing historical text-critical analysis and other methods employed by biblical scholarship. Like all scriptures, biblical statements on Mary were not only part of divine revelation[citation needed], but were written in a historic and socio-cultural context, which require explanation. Of special importance in this context is the application of biblical hermeneutics (the analysis of synonym words for a better understanding of their meaning). Hermeneutics assists in the analysis of the relation between biblical statements on Mary, the faith of the early Christians and the Marian tradition of the Church. Because of the mother-son relation, the historical research into the life of Jesus is of obvious interest to Mariology.[40]

Church history

Within the field of Church history, Mariology is concerned with the development of Marian teachings and the various forms of Marian culture. An important part of Church history is patristics or patrology, the teaching of the early Fathers of the Church. They give indications of the faith of the early Church and are analyzed in terms of their statements on Mary.

In the Roman Catholic context, patrology and dogmatic history have at times provided a basis for popes to justify Marian belief, veneration, and dogmas such as the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption. Thus, in Fulgens corona and Munificentissimus Deus, Pope Pius XII explained the two dogmas in terms of existing biblical references to Mary, the patristic tradition, and the strong historical faith of believers (sensus fidelium). He employed a deductive theological method.[41]

Moral theology

Some scholars do not see a direct relation of Mariology to Moral Theology. Pius X, however, described Mary as the model of virtue, virginity, and a life free of sin, living a life that exemplifies many moral teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. Mary is cited in that way in pastoral theology and sermons. Moral theology includes teachings on mysticism, to which Marian spirituality relates. Marian charisma, Marian apparitions and other private revelations are also subject to Catholic teachings on revelation, mysticism and canon law.

See also

Notes

- ^ The icon handbook: a guide to understanding icons and the liturgy by David Coomler 1995 ISBN 0-87243-210-6 page 203

- ^ The era of Michelangelo: masterpieces from the Albertina by Achim Gnann 2004 ISBN 88-370-2755-9 page 54

- ^ The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley 2003 ISBN 90-04-12654-6 pages 403-404

- ^ Rahner, Karl 2004 Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi ISBN 0-86012-006-6 page 901

- ^ a b Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim. Encyclopedia of Protestantism, Volume 3 2003. ISBN 0-415-92472-3 page 1174

- ^ Encyclopedia of Social History (ISBN 0815303424 page 573) states: "More broadly defined, Mariology is the study of devotion to and thinking about Mary throughout the history of Christianity."

- ^ Schroedel, Jenny The Everything Mary Book, 2006 ISBN 1-59337-713-4 page 84

- ^ Walsingham shrine

- ^ Burke, Raymond et al. Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons 2008 ISBN 978-1-57918-355-4 page 590

- ^ a b c d Rahner, Karl 2004 Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi ISBN 0-86012-006-6 pages 393-394

- ^ a b The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley 2003 ISBN 90-04-12654-6 page 409

- ^ Damascene, John. Homily 2 on the Dormition 14; PG 96, 741 B

- ^ Damascene, John. Homily 2 on the Dormition 16; PG 96, 744 D

- ^ The Orthodox Church by Sergei Nikolaevich Bulgakov 1997 ISBN 0-88141-051-9 page 67

- ^ The Celebration of Faith: The Virgin Mary by Alexander Schmemann 2001 ISBN 0-88141-141-8 pages 60-61

- ^ Modern Russian Theology: Ortholdox Theology In A New Key by Paul Vallierey 2000 ISBN 0-567-08755-7 pages

- ^ "Protestantische Marien Kunst", in Bäumer, Marienlexikon, V, pp 325-336, Marian veneration in Protestantismus, pp 336-342

- ^ Mary, Mother of God by Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson 2004 ISBN 0802822665 page 84

- ^ The Canons of the Two Hundred Holy and Blessed Fathers Who Met at Ephesus

- ^ "Mary, The New Eve". Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ A. Cameron, "The Theotokos in sixth-century Constantinople", Journal of Theological Studies, New Series 19 (1978:79-108).

- ^ John L. Osborne, "Early Medieval Painting in San Clemente, Rome: The Madonna and Child in the Niche" Gesta 20.2 (1981:299-310) and (note 9) referencing T. Klauser, "Rom under der Kult des Gottesmutter Maria", Jahrbuch für der Antike und Christentum 15 (1972:120-135).

- ^ M. Mundell, "Monophysite church decoration" Iconoclasm (Birmingham) 1977:72.' [1], [2]

- ^ Liber Pontificalis, I, 317.

- ^ First mentioned under this new dedication in the Salzburg Itinerary, undated but first half of the seventh century (Maria Andalore, "La datazione della tavola di S. Maria in Trastevere", Rivista dell'Istituto Nazionale d'Archeologia e Storia d'Arte, New Series 20 [1972-73:139-215], p. 167).

- ^ Liber Pontificalis, I, 376.

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: K-P by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1994 ISBN 0-8028-3783-2 page 272

- ^ Daughters of the church 1987 by Ruth Tucker ISBN 0-310-45741-6 page 168

- ^ Academia Mariana Salesiana, 1950, Centro Mariano Monfortano to Rome, 1950, Pontifical University Marianum, 1950, and Collegiamento Mariano Nationale, 1958

- ^ a b c Mariology by Michael Schmaus in the Encyclopedia of Theology: A Concise Sacramentum Mundi by Karl Rahner (Dec 28, 2004) ISBN 0860120066 pages 901-902

- ^ Kihn, 63

- ^ Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity, 1968, in the original German version, p. 230

- ^ "Mariologie", in Bäumer, Lexikon der Marienkunde

- ^ Maria und die Kirche, Tyrolia-Verlag, 1961 (English Translation: Our Lady and the Church, Zaccheus Press, 2004)

- ^ Hugo Rahner in Bäumer, Lexikon der Marienkunde

- ^ Lexikon der kath., "Dogmatik, Mariologie", 1988

- ^ Saint Louis de Montfort,God Alone

- ^ Pope John Paul II, Redemptoris Mater, 51

- ^ Pope Pius XII, Mystici corporis Christi; John Henry Newman: Mariology is always christocentric, in Michael Testa, Mary: The Virgin Mary in the Life and Writings of John Henry Newman, 2001

- ^ H Kihn, Encyclopedie fer theologie, 1892, 102

- ^ Lexikon der kath. Dogmatik, Mariologie, 1988

References

- Konrad Algermissen, Lexikon der Marienkunde, Regensburg, 1967 (Roman Catholic mariological Encyclopedia)

- Remigius Bäumer, Marienlexikon, Eos, St. Ottilien, 1992 (Roman Catholic mariological Encyclopedia)

- W Beinert, Lexikon der katholischen Dogmatik, Herder Freiburg, 1988 (Roman Catholic theological Encyclopedia)

- Heinrich Kihn Encyklopaedie und Methodologie der Theologie, Freiburg, Herder, 1892(Roman Catholic theological Encyclopedia)

- Joseph Ratzinger Introduction to Christianity, 1968 (Roman Catholic Pope Benedict XVI)

External links

- All About Mary: An encyclopedic tool for information on Mary, the Mother of Christ, compiled by the University of Dayton's Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute, the world's largest repository of books, artwork and artifacts devoted to Mary and a pontifical center of research and scholarship.

- Pontifical Marian International Academy

- University of Dayton- Guide to the Madonna: Mary in the Catholic Tradition course materials