Principality of Moscow

Principality of Moscow Grand Duchy of Moscow

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1282[1]–1547 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Double-headed eagle on the seal of Ivan III

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Attributed coat of arms on the Carta marina (1539):  | |||||||||||||||||||||

Territorial expansion of the Principality of Moscow, 1300–1547 Core territory of Muscovy, 1300 Territory of Vladimir-Suzdal, acquired by Muscovy by 1390 Territory acquired by 1505 (Ivan III) Territory acquired by 1533 (Vasili III) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Moscow | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old East Slavic, Russian | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox (official)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Muscovite | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Prince of Moscow | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1282–1303[1] | Daniel (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1533–1547 | Ivan IV (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Boyar Duma & Veche | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1282[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 January 1547 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1505[3] | 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | ruble, denga | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Principality of Moscow[4][5] or Grand Duchy of Moscow[6][7] (Russian: Великое княжество Московское, romanized: Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye), also known simply as Muscovy (from the Latin Moscovia),[8][5] was a principality of the Late Middle Ages centered on Moscow. It eventually evolved into the Tsardom of Russia in the early modern period. The princes of Moscow were descendants of the first prince Daniel, referred to in modern historiography as the Daniilovichi,[9] a branch of the Rurikids.

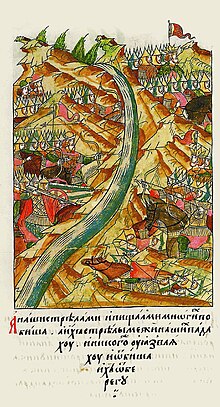

In 1263, Daniel inherited the territory as an appanage of his father Alexander Nevsky, prince of Vladimir-Suzdal, but it was not until 1282 that Daniel is mentioned as an independent prince of Moscow.[10] Initially, Muscovy was a vassal state to the Golden Horde, paying the khans homage and tribute.[11] Moscow eclipsed and eventually absorbed its parent principality and later the other independent Russian principalities.[12] The Great Stand on the Ugra River in 1480 marked the end of nominal Tatar suzerainty over Russia,[13][11] though there were frequent uprisings and several successful military campaigns against the Mongols, such as an uprising led by Dmitry Donskoy against the ruler of the Golden Horde, Mamai, in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380.[14]

Ivan III ("the Great") further consolidated the state during his 43-year reign, campaigning against his major remaining rival power, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and by 1503, he had tripled the territory of his realm. Ivan's successor Vasili III also enjoyed military success, gaining Smolensk from Lithuania in 1512 and pushing Muscovy's borders to the Dnieper. Vasili's son Ivan IV ("the Terrible") was crowned tsar in 1547.[15]

Name

[edit]The 'Principality of Moscow'[4][5] is also known as 'Muscovy',[5] the 'Grand Principality of Moscow',[16][17][18] 'Muscovite Rus',[19][20] or 'Muscovite Russia'.[20] The English names Moscow and Muscovy, for the city, the principality, and the river, descend from post-classical Latin Moscovia, Muscovia (compare Russian Moskoviya, "principality of Moscow"), and ultimately from the Old East Slavic fully vocalized accusative form Московь, Moskovĭ.[21][22] In Latin, the Moscow principality was also historically referred to as Ruthenia Alba.[23]

The oldest endonyms of the Principality of Moscow used in its documents for itself were "Rus'" (Русь) and the "Russian land" (Русская земля, Russkaya zemlya).[24] A new form of the name became common by the 15th century,[25][26][27] the vernacular Rus' was transformed into Rus(s)iya or Ros(s)iya (based on the Greek name for Rus').[28] In the 1480s, Russian state scribes Ivan Cherny and Mikhail Medovartsev mention Russia under the name "Росиа" (Rosia), and Medovartsev also mentions the sceptre "of Russian lordship" (Росийскаго господства, Rosiyskago gospodstva).[29] Zadonshchina, an East Slavic manuscript from the 14th century attributed to Sofony of Ryazan, which is an epic about Prince Dmitry Donskoy's victory over the Golden Horde, stressed the unity of the Rus' princes and described the principalities of Moscow, Novgorod, and others as the "Russian land."[30][31]

The title of the rulers included "The Prince (Knyaz) of Moscow" (Московский князь, Moskovskiy knyaz) or "the Sovereign of Moscow" (Московский государь, Moskovskiy gosudar) as common short titles.[citation needed] After the unification with the Principality of Vladimir in the mid-14th century, the prince of Moscow might call themselves also "the Prince of Vladimir and Moscow", as Vladimir was much older than Moscow and much more "prestigious" in the hierarchy of possessions, although the principal residence of the princes had always been in Moscow.[citation needed] In rivalry with other principalities (especially the Principality of Tver), Muscovite princes also designated themselves as the "Grand Princes", claiming a higher position in the hierarchy of Rus' princes.[citation needed] During the territorial growth and later acquisitions, the full title became rather lengthy.[32][better source needed] In routine documents and on seals, though, various short names were applied: "the (Grand) Prince of Moscow", "the Sovereign of Moscow", "the Grand Prince of all Rus'" (Великий князь всея Руси, Velikiy knyaz vseya Rusi), "the Sovereign of all Rus'" (Государь всея Руси, Gosudar vseya Rusi), or simply "the Grand Prince" (Великий князь, Velikiy knyaz) or "the Great (or Grand) Sovereign" (Великий государь, Velikiy gosudar).[citation needed] The Golden Horde appointed Ivan Kalita to the throne of "All Russia" while Simeon the Proud took the title of Grand Duke of All Russia.[33]

Despite feudalism, the collective name of the Eastern Slavic land, Rus', was not forgotten,[34] though it then became a cultural and geographical rather than the political term, as there was no single political entity on the territory. Since the 14th century various Muscovite princes added "of all Rus'" (всея Руси, vseya Rusi) to their titles, after the title of Russian metropolitans, "the Metropolitan of all Rus'".[35] Dmitry Shemyaka (died 1453) was the first Muscovite prince who minted coins with the title "the Sovereign of all Rus'".[citation needed] Although initially both "Sovereign" and "all Rus'" was supposed to be rather honorific epithets,[35] since Ivan III is transformed into the political claim over the territory of all the former Kievan Rus', a goal that the Muscovite prince came closer to by the end of that century, uniting eastern Rus'.[34]

Such claims raised much opposition and hostility from its main rival, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which controlled a large (western) portion of the land of ancient Rus' and hence denied any claims and even the self-name of the eastern neighbour.[34][35] Under the Polish-Lithuanian influence the country began to be called Muscovy (Latin: Moscovia, Muscovy, French: Moscovie) in Western Europe.[34] The first appearances of the term were in an Italian document of 1500.[34] Initially Moscovia was the Latinized name of the city of Moscow itself, not of the state;[34] later it acquired its wider meaning (synecdoche) and has been used alongside the older name, Russia. The term Muscovy persisted in the West until the beginning of the 18th century and is still used in historical contexts. The term remains current in Arabic as an alternative name for Russia. Derived from it is al-Muskubīya (المسكوبية), the Arabic name of the Russian Compound district of Jerusalem, where Czarist Russia established various institutions in the 19th century, and hence also the name of the Al-Moskobiya Detention Centre located there.[citation needed]

During his reign, Ivan III the Great claimed the title of "Tsar of all Russia".[36]

Origin

[edit]When the Mongols invaded the former lands of Kievan Rus' in the 13th century, Moscow was still a small town within the principality of Vladimir-Suzdal.[37] Although the Mongols burnt down Moscow in the winter of 1238 and pillaged it in 1293, the outpost's remote, forested location offered some security from Mongol attacks and occupation, while a number of rivers provided access to the Baltic and Black Seas and to the Caucasus region.[38] Muscovites, Suzdalians and other inhabitants were able to maintain their Slavic, pagan, and Orthodox traditions for the most part under the Tatar yoke.[citation needed]

More important to the development of the state of Moscow, however, was its rule by a series of princes who expanded its borders and turned a small principality in the Moscow River Basin into the largest state in Europe of the 16th century.[39] The first ruler of the principality of Moscow, Daniel I (d. 1303), was the youngest son of Alexander Nevsky of Vladimir-Suzdal. He started to expand his principality by seizing Kolomna and securing the bequest of Pereslavl-Zalessky to his family. Daniel's son Yury (also known as Georgiy; ruled 1303–1325) controlled the entire basin of the Moskva River and expanded westward by conquering Mozhaisk. He then allied with the overlord of the principalities, Uzbeg Khan of the Golden Horde, and married the khan's sister. The khan allowed Yuriy to claim the title of Grand Duke of Vladimir-Suzdal, a position which allowed him to interfere in the affairs of the Novgorod Republic to the northwest.[citation needed]

By the early 14th century, Moscow had improved its standing against other towns within its parent principality of Vladimir-Suzdal, and by the 1320s, it emerged as the most influential, largely due to decisions made by the Mongol khan; aside from this, the Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus' started to be based in Moscow too.[37] In 1325, Metropolitan Peter (died 1326) transferred his residence from Kiev to Vladimir and then to Moscow, further enhancing the prestige of the new principality.[40]

Yuriy's successor, Ivan I (ruled 1325–1340), managed to retain the title of grand duke by cooperating closely with the Mongols and by collecting tribute and taxes from the other principalities on their behalf. This relationship enabled Ivan to gain regional ascendancy, particularly over Moscow's chief rival, the northern city of Tver, which rebelled against the Horde in 1327. The uprising was subdued by the joint forces of the Grand Principality of Suzdal, the Grand Principality of Moscow (which competed with Tver for the title of Grand Duke of Vladimir), and Tatars.[41] Ivan's moniker "Kalita" (literally, the "moneybag") was an indication of his character as a businessman.[42] He used his treasures to purchase land in other principalities and to finance the construction of stone churches in the Moscow Kremlin.[citation needed]

Dmitry Donskoy

[edit]

Ivan's successors continued the "gathering of the Russian lands" to increase the population and wealth under their rule. In the process, their interests clashed with the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania, whose subjects were predominantly East Slavic and Orthodox. Grand Duke Algirdas of Lithuania allied himself by marriage with Tver and undertook three expeditions against Moscow (1368, 1370, 1372) but was unable to take it. The main bone of contention between Moscow and Vilnius was the large city of Smolensk.[citation needed]

In the 1350s, the country and the royal family were hit by the Black Death. Dmitry Ivanovich was aged nine when his parents died and the title of Grand Duke slipped into the hands of his distant relative, Dmitry of Suzdal. Surrounded by Lithuanians and Muslim nomads, the ruler of Moscow cultivated an alliance with the Rus' Orthodox Church, which experienced a resurgence in influence, due to the monastic reform of St. Sergius of Radonezh.[citation needed]

Educated by Metropolitan Alexis, Dmitri posed as a champion of Orthodoxy and managed to unite the warring principalities of Rus' in his struggle against the Horde. He challenged Khan's authority and defeated his commander Mamai in the Battle of Kulikovo (1380). However, the victory did not bring any short-term benefits; Tokhtamysh in 1382 sacked Moscow hoping to reassert his vested authority over his vassal, the Grand Prince, and his own Mongol hegemony, killing 24,000 people.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, Dmitri became a national hero. The memory of Kulikovo Field made the Russian population start believing in their ability to end Tatar domination and become a free people. In 1389, he passed the throne to his son Vasily I without bothering to obtain the Khan's sanction.[citation needed]

Vasily I and Vasily II

[edit]

Vasily I (1389–1425) continued the policies of his father. After the Horde was attacked by Tamerlane, he desisted from paying tribute to the Khan but was forced to pursue a more conciliatory policy after Edigu's incursion on Moscow in 1408. Married to the only daughter of the Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania, he attempted to avoid open conflicts with his powerful father-in-law, even when the latter annexed Smolensk. The peaceful years of his long reign were marked by the continuing expansion to the east (annexation of Nizhny Novgorod and Suzdal, 1392) and to the north (annexation of Vologda, Veliky Ustyug, and Perm of Vychegda, 1398). Nizhny Novgorod was given by the Khan of the Golden Horde as a reward for Muscovite's help against a rival.[43]

The reforms of St. Sergius triggered a cultural revival, exemplified by the icons and frescoes of the monk Andrei Rublev. Hundreds of monasteries were founded by disciples of St. Sergius in distant and inhospitable locations, including Beloozero and Solovki. Apart from their cultural functions, these monasteries were major landowners who could control the economy of an adjacent region. They served as outposts of Moscow's influence in the neighbouring principalities and republics. Another factor responsible for the expansion of the Grand Principality of Moscow was its favourable dynastic situation, in which each sovereign was succeeded by his son, while rival principalities were plagued by dynastic strife and splintered into ever-smaller polities. The only lateral branch of the House of Moscow, represented by Vladimir of Serpukhov and his descendants, was firmly anchored to the Moscow principality. [citation needed]

The situation changed with the ascension of Vasily I's successor, Vasily II (r. 1425–1462). Before long his uncle, Yuri of Zvenigorod, started to advance his claims to the throne and Monomakh's Cap. A bitter family conflict erupted and rocked the country during the whole reign. After Yuri died in 1432, the claims were taken up by his sons, Vasily Kosoy and Dmitry Shemyaka, who pursued the Great Feudal War well into the 1450s. Although he was ousted from Moscow on several occasions, taken prisoner by Olug Moxammat of Kazan, and blinded in 1446, Vasily II eventually managed to triumph over his enemies and pass the throne to his son. At his urging, a native bishop was elected as Metropolitan of Moscow, which was tantamount to a declaration of independence of the Russian Orthodox Church from the Patriarch of Constantinople (1448).[citation needed]

Ivan III

[edit]

The outward expansion of the grand principality in the 14th and 15th centuries was accompanied by internal consolidation. By the 15th century, the rulers of Moscow considered the entire territory of the former Kievan Rus' to be their collective property. Various semi-independent princes of Rurikid stock still claimed specific territories, but Ivan III (the Great; r. 1462–1505) forced the lesser princes to acknowledge the grand prince of Moscow and his descendants as unquestioned rulers with control over military, judicial, and foreign affairs.[citation needed]

Moscow gained full sovereignty over a significant part of Rus' by 1480 when the overlordship of the Tatar Golden Horde officially ended after its defeat in the Great Stand on the Ugra River. By the beginning of the 16th century, virtually all those lands were united, including the Novgorod Republic (annexed in 1478) and the Principality of Tver (annexed in 1485). Through inheritance, Ivan was able to control the important Principality of Ryazan, and the princes of Rostov and Yaroslavl subordinated themselves to him. The northwestern city of Pskov, consisting of the city and a few surrounding lands, remained independent in this period, but Ivan's son, Vasili III (r. 1505–33), later conquered it.[citation needed]

Having consolidated the core of Russia under his rule, Ivan III became the first Moscow ruler to adopt the titles of tsar[44] and "Ruler of all Rus'".[38] Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, for control over some of the semi-independent former principalities of Kievan Rus' in the upper Dnieper and Donets river basins. Through the defections of some princes, border skirmishes, and the long inconclusive Russo-Lithuanian Wars that ended only in 1503, Ivan III was able to push westward, and the Moscow state tripled in size under his rule.[citation needed]

The reign of the Tsars started officially with Ivan the Terrible, the first monarch to be crowned Tsar of Russia, but in practice, it started with Ivan III, who completed the centralization of the state (traditionally known as "the gathering of the Russian lands").[citation needed]

Court

[edit]

The court of the Moscow princes combined ceremonies and customs inherited from Kievan Rus' with those imported from the Byzantine Empire and Golden Horde. Some traditional Russian offices, like that of tysyatsky and veche, were gradually abolished to consolidate power in the hands of the ruling prince. A new elaborate system of court precedence, or mestnichestvo, predicated the nobleman's rank and function on the rank and function of his ancestors and other members of his family. The highest echelon of hereditary nobles was composed of boyars.[citation needed] They fell into three categories:

- Rurikid princes of Upper Oka towns, Suzdal, Rostov, Yaroslavl, etc. that lived in Moscow after their hereditary principalities had been incorporated into the Principality of Moscow (e.g., Shuisky, Vorotynsky, Repnin, Romodanovsky);[citation needed]

- Foreign princes from Lithuania and Golden Horde, claiming descent either from Grand Duke Gediminas (e.g., Belsky, Mstislavsky, Galitzine, Trubetskoy) or from Genghis Khan;[citation needed]

- Ancient families of Moscow nobility that have been recorded in the service of Grand Dukes from the 14th century (e.g., Romanov, Godunov, Sheremetev).[citation needed]

Rurikid and Gediminid boyars, whose fathers and grandfathers were independent princelings, felt that they were kin to the grand prince and hence almost equal to him. During the times of dynastic troubles (such as the years of Ivan IV's minority), boyardom constituted an internal force that was a permanent threat to the throne. An early form of the monarch's conflict with the boyars was the oprichnina policy of Ivan the Terrible.[citation needed]

During such conflicts, Ivan, Boris Godunov, and some later monarchs felt the necessity to counterbalance the boyardom by creating a new kind of nobility, based on personal devotion to the tsar and merits earned by faithful service, rather than by heredity. Later these new nobles were called dvoryans (singular: dvoryanin). The name comes from the Russian word dvor, meaning tsar's dvor, i.e., The Court. Hence the expression pozhalovat ko dvoru, i.e., to be called to (serve) The Court.[citation needed]

Relations with the Horde

[edit]

Relations between the Moscow principality and the Horde were mixed.[45] In the first two decades of the 13th century Moscow gained the support of one of the rivalling Mongol statesmen, Nogai, against the principalities that were oriented towards Sarai khans. After the restoration of unity in the Golden Horde in the early 14th century, it generally enjoyed the favour of the Khans until 1317 but lost it in 1322–1327.[45] The following thirty years, when the relations between the two states improved, allowed Moscow to achieve sufficient economic and political potential. Further attempts to deprive its rulers of the status of grand dukes of Vladimir were unsuccessful after the Khanate sank into internecine war and proved to be fruitless during the reign of a relatively powerful khan such as Mamai, whereas Tokhtamysh had no other choice but to recognize the supremacy of Moscow over northern and eastern Russian lands.[45] The traditional Mongol principle of breaking up larger concentrations of power into smaller ones failed, and the following period is characterized by the lack of support from the Horde.[45]

Although Moscow recognized khans as the legitimate authority in the early years of the Mongol-Tatar yoke, despite certain acts of resistance and disobedience, it refused to acknowledge their suzerainty in the years 1374–1380, 1396–1411, 1414–1416 and 1417–1419, even despite the growing might of the Golden Horde.[46] The power of the Horde over Moscow was greatly limited in the reign of Dmitri Donskoi, who gained recognition of the Grand Principality of Vladimir as a hereditary possession of Moscow princes: while the Horde collected tribute from his land, it could no longer have a serious impact on the internal structure of northern Russian lands.[47] In the years of Vasily II and Ivan III, the Grand Principality of Moscow acquired the idea of tsardom from the fallen Byzantine Empire, which was incompatible with the recognition of the suzerainty of the khan, and started to declare its independence in diplomatic relations with other countries.[48] This process was complete by the reign of Ivan III.[46]

Assessment

[edit]The development of the modern-day Russian state is traced from Kievan Rus' through Vladimir-Suzdal and the Grand Principality of Moscow to the Tsardom of Russia, and then the Russian Empire.[49] The Moscow principality drew people and wealth to the northeastern part of Kievan Rus';[49] established trade links to the Baltic Sea, White Sea, Caspian Sea, and to Siberia; and created a highly centralized and autocratic political system. The political traditions established in Muscovy, therefore, exerted a powerful influence on the future development of Russian society.[citation needed]

Society

[edit]Class

[edit]

- Boyar

- Former people (Byvshiye lyudy)

- Izgoi

- Kholop

- Knyaz

- Posad people

- Service class people (Sluzhilyye lyudi)

- Smerd

Culture

[edit]Muscovite Russia was culturally influenced by Slavic and Byzantine cultural elements. In Muscovite Russia supernaturalism was a fundamental part of daily life.[50]

See also

[edit]- Prince of Moscow

- Collector of Russian lands

- List of wars involving the Principality of Moscow

- Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe

- 15th–16th century Moscow–Constantinople schism

- List of tribes and states in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empire

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kuchkin, Vladímir Andreevich (1995). Первый московский князь Даниил Александрович [The first Moscow prince, Danil Aleksandrovich]. Russian History. Vol. 1. Nauka. pp. 94–107. ISSN 0869-5687.

- ^ W. Werth, Paul (2014). The Tsar's Foreign Faiths: Toleration and the Fate of Religious Freedom in Imperial Russia. Oxford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780199591770.

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia" (PDF). International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 498. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-07-07. Retrieved 2021-10-21.

- ^ a b Martin 2007, p. 208, 222, 228, 231.

- ^ a b c d Halperin 1987, p. 217.

- ^ A Short History of the USSR. Progress Publishers. 1965.

- ^ Florinsky, Michael T. (1965). Russia: a History and an Interpretation.

- ^ Introduction into the Latin epigraphy (Введение в латинскую эпиграфику) Archived 2021-03-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 487.

- ^ Kuchkin, Vladímir Andreevich (1995). Первый московский князь Даниил Александрович [The first Moscow prince, Danil Aleksandrovich]. Russian History. Vol. 1. Nauka. pp. 94–107. ISSN 0869-5687.

- ^ a b Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2015). Western civilization (Ninth ed.). Stamford, CT. p. 361. ISBN 978-1285436401.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Duiker, William J. (2016). World history (Eighth, Advantage ed.). Boston, MA. p. 446. ISBN 978-1305091726.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thompson, John M. (2019). Russia and the Soviet Union: an historical introduction second edition. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 9781000310566.

- ^ Davies, B. Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 1500–1700. Routledge, 2014, p. 5

- ^ Madariaga, Isabel de (2005). Ivan the Terrible : first tsar of Russia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780300119732.

- ^ Perrie, Maureen, ed. (2006). The Cambridge History of Russia. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 751. ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6.

- ^ Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-139-45892-4.

- ^ "Grand Principality of Moscow". Britannica. Retrieved 2024-10-18.

- ^ Isham, Heyward; Pipes, Richard (2016-09-16). Remaking Russia: Voices from within: Voices from within. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-48307-8.

- ^ a b Dewey, Horace W. (1987). "Political Poruka in Muscovite Rus'". The Russian Review. 46 (2): 117–133. doi:10.2307/130622. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 130622.

- ^ "Moscow, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. December 2002. Retrieved 10 January 2021. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Muscovy, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. March 2003. Retrieved 10 January 2021. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Andrew Miksys: White Russia in Color - Laimonas Briedis". www.lituanus.org. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Б. М. Клосс. О происхождении названия "Россия". М.: Рукописные памятники Древней Руси, 2012. С. 3

- ^ Б. М. Клосс. О происхождении названия "Россия". М.: Рукописные памятники Древней Руси, 2012. С. 13

- ^ E. Hellberg-Hirn. Soil and Soul: The Symbolic World of Russianness. Ashgate, 1998. p. 54

- ^ Lawrence N. Langer. Historical Dictionary of Medieval Russia. Scarecrow Press, 2001. p. 186

- ^ Obolensky, Dimitri (1994). Byzantium and the Slavs. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780881410082.

- ^ Б. М. Клосс. О происхождении названия "Россия". М.: Рукописные памятники Древней Руси, 2012. С. 30–38

- ^ "ЗАДОНЩИНА". Medieval Russian Literature (in Russian). Translated by L. A. Dmitriev.

- ^ Zenkovsky 1963, pp. 211–228.

- ^ The full title of Vasily III (the father of the first Russian tsar Ivan IV) in a 1517 document: "By God's will and our own desire, We, the Great Sovereign Vasily, by God's grace, the Tsar (sic!) and the Sovereign of all Rus' and the Grand Prince of Vladimir, Moscow, Novgorod, Pskov, Smolensk, Tver, Yugra, Perm, Vyatka, Bolgar, and others, and the Grand Prince of Novgorod of the lower lands [i.e. Nizhny Novgorod], Chernigov, Ryazan, Volok, Rzhev, Bely, Rostov, Yaroslavl, Belozersk, Udora, Obdora, Konda, and others..." Сборник Русского исторического общества. Vol. 53. СПб. 1887. p. 19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Marat Shaikhutdinov (2021). Between East and West: The Formation of the Moscow State. Academic Studies Press. pp. 64, 69, 146. ISBN 9781644697139.

- ^ a b c d e f Хорошкевич, А. Л. (1976). "Россия и Московия: Из истории политико-географической терминологии" [Khoroshkevich A. L. Russia and Muscovy: from the history of politico-geographic terminology]. Acta Baltico-Slavica. X: 47–57.

- ^ a b c Филюшкин, А. И. (2006). Титулы русских государей [Filyushkin A. I. The titles of the Russian rulers]. Альянс-Архео. pp. 152–193. ISBN 978-5-98874-011-7.

- ^ Pape, Carsten (2016). "Titul Ivana III po datskim istochnikam pozdnego Srednevekov'ya" Титул Ивана III по датским источникам позднего Средневековья [The title of Ivan III according to late-medieval Danish sources]. Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana (in Russian). 20 (2). St. Petersburg: 65–75. doi:10.21638/11701/spbu19.2016.205. Retrieved 2023-05-16.

- ^ a b Wickham, Chris (2016-10-15). Medieval Europe. Ceredigion, Wales: Yale University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-300-22221-0.

- ^ a b Library of Congress Country Studies – Russia

- ^ Gorskij, A. A. (2000). Moskva i Orda (in Russian) (Naučnoe izd. ed.). Moskva: Nauka. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-5-02-010202-6. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^

Compare: Trepanier, Lee (2010). "2: Muscovite Russia (ca. 1240 – ca. 1505)". Political Symbols in Russian History: Church, State, and the Quest for Order and Justice. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Lanhan, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 31. ISBN 9780739117897. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

But the crucial year was 1326, when [Metropolitan] Peter became a resident of Moscow and began to build his burial vault. On December 20, 1326. Metropolitan Peter died and was buried by one of the bishops in the presence of Ivan I. Due to his residency and burial place, Metropolitan Peter had confirmed Moscow the future haven of the Russian Orthodox Church, although this official transfer would not take place until the reign of Alexis.

- ^ Martin J. Medieval Russia, 980–1584. 2007. Cambridge University Press. p. 196

- ^ Moss (2005)

- ^ Richard Pipes, Russia under the Old Regime (1995), p.80.

- ^ Trepanier, L. Political Symbols in Russian History: Church, State, and the Quest for Order and Justice. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 39

- ^ a b c d Gorskij, A.A. (2000). Moskva i Orda (in Russian) (Naučnoe izd. ed.). Moskva: Nauka. p. 187. ISBN 978-5-02-010202-6. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ a b Gorskij, A.A. (2000). Moskva i Orda (in Russian) (Naučnoe izd. ed.). Moskva: Nauka. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-5-02-010202-6. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Gorskij, A.A. (2000). Moskva i Orda (in Russian) (Naučnoe izd. ed.). Moskva: Nauka. p. 189. ISBN 978-5-02-010202-6. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Gorskij, A.A. (2000). Moskva i Orda (in Russian) (Naučnoe izd. ed.). Moskva: Nauka. p. 188. ISBN 978-5-02-010202-6. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ a b A Brief History of Russia by Michael Kort pg.xxiii

- ^ Wigzell, Faith (2010-01-31). "Valerie A. Kivelson and Robert H. Greene (eds). Orthodox Russia: Belief and Practice under the Tsars". Folklorica. 9 (2): 169–171. doi:10.17161/folklorica.v9i2.3754. ISSN 1920-0242.

Bibliography

[edit]- Halperin, Charles J. (1987). Russia and the Golden Horde: The Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Indiana University. p. 222. ISBN 9781850430575. (e-book).

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Second Edition. E-book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36800-4.

- Meyendorff, John (1981). Byzantium and the Rise of Russia: A Study of Byzantino-Russian Relations in the Fourteenth Century (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521135337.

- Zenkovsky, Serge A., ed. (1963). Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles, and Tales. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780452010864.

- Moss, Walter G (2005). "History of Russia - Volume 1: To 1917", Anthem Press, p. 80

- Ostrowski, Donald. Muscovy and the Mongols: Cross-Cultural Influences on the Steppe Frontier, 1304–1589. Cambridge University Press. 2002.

Further reading

[edit]- Chester Dunning, The Russian Empire and the Grand Duchy of Muscovy: A Seventeenth Century French Account

- Romaniello, Matthew (September 2006). "Ethnicity as social rank: Governance, law, and empire in Muscovite Russia". Nationalities Papers. 34 (4): 447–469. doi:10.1080/00905990600842049. S2CID 109929798.

- Marshall Poe, Foreign Descriptions of Muscovy: An Analytic Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Sources, Slavica Publishers, 1995, ISBN 0-89357-262-4

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. - Russia

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. - Russia

External links

[edit] Media related to Grand Duchy of Moscow at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Grand Duchy of Moscow at Wikimedia Commons

- Principality of Moscow

- States and territories established in 1283

- States and territories disestablished in 1547

- 1282 establishments in Europe

- 13th-century establishments in Russia

- 1547 disestablishments in Europe

- History of Moscow Oblast

- Former monarchies of Europe

- 13th century in Russia

- 14th century in Russia

- 15th century in Russia

- 16th century in Russia

- 16th century in Moscow

- States and territories disestablished in the 1540s

- Former countries

- Vassal and tributary states of the Golden Horde

- Christian states