Papal States

States of the Church Stato della Chiesa Status Pontificius | |

|---|---|

| 754–1870 Interregnums (1798–1799 and 1849) | |

| Anthem: Noi vogliam Dio, Vergine Maria ( – 1857) (Italian) "We want God, Virgin Mary" "Great Triumphal March" | |

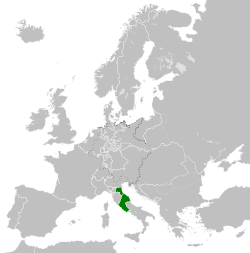

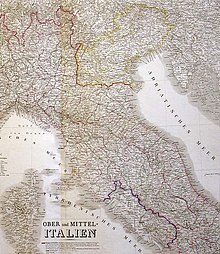

The Papal States in 1815 after the Napoleonic Wars | |

Map of the Papal States (green) in 1700, including its exclaves of Benevento and Pontecorvo in Southern Italy, and the Comtat Venaissin and Avignon in Southern France. | |

| Capital | Rome |

| Common languages | Latin, Italian, Occitan |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Government | Theocratic absolute elective monarchy |

| Pope | |

• 754–757 | Stephen II (first) |

• 1846–1870 | Pius IX (last) |

| Cardinal Secretary of State | |

• 1551–1555 | Girolamo Dandini (first) |

• 1848–1870 | Giacomo Antonelli (last) |

| Prime Minister | |

• 1848 | Gabriele Ferretti (first) |

• 1848 | Giuseppe Galletti (last) |

| History | |

• Establishment | 754 |

| 781 | |

• Treaty of Venice (Independence from the Holy Roman Empire) | 1177 |

| February 15, 1798 | |

| September 20, 1870 | |

| February 11, 1929 | |

| Currency | Papal States scudo (until 1866) Papal States lira (1866–1870) |

| Today part of | |

The Papal States were territories in the Italian Peninsula under the sovereign direct rule of the pope, from the 8th century until 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from roughly the 8th century until the Italian Peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. At their zenith, they covered most of the modern Italian regions of Lazio (which includes Rome), Marche, Umbria and Romagna, and portions of Emilia. These holdings were considered to be a manifestation of the temporal power of the pope, as opposed to his ecclesiastical primacy. After 1861, the Papal States, reduced to Lazio, continued to exist until 1870. Between 1870 and 1929, the pope had no physical territory at all. Eventually Italian leader Benito Mussolini solved the crisis between modern Italy and the Vatican, and, in 1929, the Vatican City State was granted sovereignty.

Name

The Papal States were also known as the Papal State (although the plural is usually preferred, the singular is equally correct as the polity was more than a mere personal union). The territories were also referred to variously as the State(s) of the Church, the Pontifical States, the Ecclesiastical States, or the Roman States (Italian: Stato Pontificio, also Stato della Chiesa, Stati della Chiesa, Stati Pontifici, and Stato Ecclesiastico; Template:Lang-la, also Dicio Pontificia).[1]

Origins

For its first 300 years the Catholic Church was persecuted and unrecognized, unable to hold or transfer property.[2] Early congregations met in rooms set aside for that purpose in the homes of well-to-do individuals, and a number of early churches, known as titular churches and located on the outskirts of Ancient Rome, were held as property by individuals, rather than by the Church itself. This system began to change during the reign of the emperor Constantine I, who made Christianity legal within the Roman Empire.[2] The Lateran Palace was the first significant donation to the Church, most probably a gift from Constantine himself.[2]

Other donations followed, primarily in mainland Italy but also in the provinces of the Roman Empire. But the Church held all of these lands as a private landowner, not as a sovereign entity. When in the 5th century the Italian peninsula passed under the control of Odoacer and, later, the Ostrogoths, the church organization in Italy, with the pope at its head, submitted to their sovereign authority while asserting their spiritual primacy over the whole Church.[citation needed]

The seeds of the Papal States as a sovereign political entity were planted in the 6th century. The Byzantine Empire based in Constantinople launched a reconquest of Italy that took decades and devastated Italy's political and economic structures. Just as these wars wound down, the Lombards entered the peninsula from the north and conquered much of the countryside. By the 7th century, Byzantine authority was largely limited to a diagonal band running roughly from Ravenna, where the Emperor's representative, or Exarch, was located, to Rome and south to Naples (the "Rome-Ravenna corridor"[3][4][5]), plus coastal enclaves.[6]

With effective Byzantine power weighted at the northeast end of this territory, the pope, as the largest landowner and most prestigious figure in Italy, began by default to take on much of the ruling authority that Byzantines were unable to project to the area around the city of Rome.[citation needed] While the popes remained Byzantine subjects, in practice the Duchy of Rome, an area roughly equivalent to modern-day Latium, became an independent state ruled by the pope.[7]

The Church's independence, combined with popular support for the papacy in Italy, enabled various popes to defy the will of the Byzantine emperor; Pope Gregory II even excommunicated Emperor Leo III during the Iconoclastic Controversy.[citation needed] Nevertheless, the pope and the exarch still worked together to control the rising power of the Lombards in Italy. As Byzantine power weakened, though, the papacy took an ever larger role in defending Rome from the Lombards, usually through diplomacy.[citation needed] In practice, the papal efforts served to focus Lombard aggrandizement on the exarch and Ravenna. A climactic moment in the founding of the Papal States was the agreement over boundaries embodied in the Lombard king Liutprand's Donation of Sutri (728) to Pope Gregory II.[8]

Donation of Pepin

When the Exarchate of Ravenna finally fell to the Lombards in 751,[9] the Duchy of Rome was completely cut off from the Byzantine Empire, of which it was theoretically still a part. The popes renewed earlier attempts to secure the support of the Franks. In 751, Pope Zachary had Pepin the Younger crowned king in place of the powerless Merovingian figurehead king Childeric III. Zachary's successor, Pope Stephen II, later granted Pepin the title Patrician of the Romans. Pepin led a Frankish army into Italy in 754 and 756. Pepin defeated the Lombards – taking control of northern Italy – and made a gift (called the Donation of Pepin) of the properties formerly constituting the Exarchate of Ravenna to the pope.

In 781, Charlemagne codified the regions over which the pope would be temporal sovereign: the Duchy of Rome was key, but the territory was expanded to include Ravenna, the Duchy of the Pentapolis, parts of the Duchy of Benevento, Tuscany, Corsica, Lombardy and a number of Italian cities. The cooperation between the papacy and the Carolingian dynasty climaxed in 800, when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Emperor.

Relationship with the Holy Roman Empire

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Vatican City |

|---|

The precise nature of the relationship between the popes and emperors – and between the Papal States and the Empire – is disputed. It was unclear whether the Papal States were a separate realm with the pope as their sovereign ruler, merely a part of the Frankish Empire over which the popes had administrative control, as suggested in the late 9th century treatise Libellus de imperatoria potestate in urbe Roma, or whether the Holy Roman Emperors were vicars of the pope (as a sort of Archemperor) ruling Christendom, with the pope directly responsible only for the environs of Rome and spiritual duties.

Events in the 9th century postponed the conflict. The Holy Roman Empire in its Frankish form collapsed as it was subdivided among Charlemagne's grandchildren. Imperial power in Italy waned and the papacy's prestige declined. This led to a rise in the power of the local Roman nobility, and the control of the Papal States during the early 10th century by a powerful and corrupt aristocratic family, the Theophylacti. This period was later dubbed the Saeculum obscurum ("dark age"), and sometimes as the "rule by harlots".[10]

In practice, the popes were unable to exercise effective sovereignty over the extensive and mountainous territories of the Papal States, and the region preserved its old system of government, with many small countships and marquisates, each centred upon a fortified rocca.

Over several campaigns in the mid-10th century, the German ruler Otto I conquered northern Italy; Pope John XII crowned him emperor (the first so crowned in more than forty years) and the two of them ratified the Diploma Ottonianum, by which the emperor became the guarantor of the independence of the Papal States.[11] Yet over the next two centuries, popes and emperors squabbled over a variety of issues, and the German rulers routinely treated the Papal States as part of their realms on those occasions when they projected power into Italy. As the Gregorian Reform worked to free the administration of the church from imperial interference, the independence of the Papal States increased in importance. After the extinction of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, the German emperors rarely interfered in Italian affairs. In response to the struggle between the Guelphs and Ghibellines, the Treaty of Venice made official the independence of Papal States from the Holy Roman Empire in 1177. By 1300, the Papal States, along with the rest of the Italian principalities, were effectively independent.

History

The Avignon papacy

From 1305 to 1378, the popes lived in the papal enclave of Avignon, surrounded by Provence, and were under the influence of the French kings in the "Avignonese Captivity" or otherwise named as the "Babylonian Captivity" (1308/9-1377).[12][13][14][15][16][17] During this period the city of Avignon itself was added to the Papal States; it remained a papal possession for some 400 years even after the popes returned to Rome, until it was seized and incorporated into the French state during the French Revolution.

During this Avignon Papacy, local despots took advantage of the absence of the popes to establish themselves in nominally papal cities: the Pepoli in Bologna, the Ordelaffi in Forlì, the Manfredi in Faenza, the Malatesta in Rimini all gave nominal acknowledgement to their papal overlords and were declared vicars of the Church.

In Ferrara, the death of Azzo VIII d'Este without legitimate heirs (1308[18]) encouraged Pope Clement V to bring Ferrara under his direct rule: however, it was governed by his appointed vicar, Robert d'Anjou, King of Naples, for only nine years before the citizens recalled the Este from exile (1317); interdiction and excommunications were in vain: in 1332 John XXII was obliged to name three Este brothers as his vicars in Ferrara.[19]

In Rome itself the Orsini and the Colonna struggled for supremacy,[20] dividing the city's rioni between them. The resulting aristocratic anarchy in the city provided the setting for the fantastic dreams of universal democracy of Cola di Rienzo, who was acclaimed Tribune of the People in 1347,[21] and met a violent death in early October 1354 as he was assassinated by supporters of the Colonna family.[22] To many, rather than an ancient Roman tribune reborn, he had become just another tyrant using the rhetoric of Roman renewal and rebirth to mask his grab for power.[22] As Prof. Guido Ruggiero states, "even with the support of Petrarch, his return to first times and the rebirth of ancient Rome was one that would not prevail."[22]

The Rienzo episode engendered renewed attempts from the absentee papacy to re-establish order in the dissolving Papal States, resulting in the military progress of Cardinal Egidio Albornoz, who was appointed papal legate, and his condottieri heading a small mercenary army. Having received the support of the archbishop of Milan and Giovanni Visconti, he defeated Giovanni di Vico, lord of Viterbo, moving against Galeotto Malatesta of Rimini and the Ordelaffi of Forlì, the Montefeltro of Urbino and the da Polenta of Ravenna, and against the cities of Senigallia and Ancona. The last holdouts against full papal control were Giovanni Manfredi of Faenza and Francesco II Ordelaffi of Forlì. Albornoz, at the point of being recalled, in a meeting with all the Papal vicars on April 29, 1357, promulgated the Constitutiones Sanctæ Matris Ecclesiæ, which replaced the mosaic of local law and accumulated traditional 'liberties' with a uniform code of civil law. These Constitutiones Egidiane mark a watershed in the legal history of the Papal States; they remained in effect until 1816. Pope Urban V ventured a return to Italy in 1367 that proved premature; he returned to Avignon in 1370 just before his death.[23]

Renaissance

During the Renaissance, the papal territory expanded greatly, notably under the popes Alexander VI and Julius II. The pope became one of Italy's most important secular rulers as well as the head of the Church, signing treaties with other sovereigns and fighting wars. In practice, though, most of the Papal States was still only nominally controlled by the pope, and much of the territory was ruled by minor princes. Control was always contested; indeed it took until the 16th century for the pope to have any genuine control over all his territories.

Papal responsibilities were often (as in the early 16th century) in conflict. The Papal States were involved in at least 3 wars in the first 2 decades.[24] Pope Julius II, the "Warrior Pope", fought on their behalf.

The Reformation began in 1517. Before the Holy Roman Empire fought the Protestants, its soldiers (including many Protestants), sacked Rome as a side effect of battles over the Papal States.[25] A generation later the armies of King Philip II of Spain defeated those of Pope Paul IV over the same issues.[26]

This period saw a gradual revival of the pope's temporal power in the Papal States. Throughout the 16th century virtually independent fiefs such as Rimini (a possession of the Malatesta family) were brought back under Papal control. In 1512 the state of the church annexed Parma and Piacenza, which in 1545 became an independent ducate under an illegitimate son of Pope Paul III. This process culminated in the reclaiming of the Duchy of Ferrara in 1598,[27][28] and the Duchy of Urbino in 1631.[29]

At its greatest extent, in the 18th century, the Papal States included most of Central Italy — Latium, Umbria, Marche and the Legations of Ravenna, Ferrara and Bologna extending north into the Romagna. It also included the small enclaves of Benevento and Pontecorvo in southern Italy and the larger Comtat Venaissin around Avignon in southern France.

French Revolution and Napoleonic era

The French Revolution proved as disastrous for the temporal territories of the Papacy as it was for the Roman Church in general. In 1791 the Comtat Venaissin and Avignon were annexed by France.[30] Later, with the French invasion of Italy in 1796, the Legations (the Papal States' northern territories[30]) were seized and became part of the Cisalpine Republic.[30]

Two years later, the Papal States as a whole were invaded by French forces, who declared a Roman Republic.[30] Pope Pius VI fled to Siena, and died in exile in Valence (France) in 1799.[30] The Papal States were restored in June 1800 and Pope Pius VII took up residency once again, but the French under Napoleon again invaded in 1808, and this time the remainder of the States of the Church were annexed to France,[30] forming the départements of Tibre and Trasimène.

With the fall of the Napoleonic system in 1814, the Papal States were restored once more.[30] From 1814 until the death of Pope Gregory XVI in 1846, the popes followed a reactionary policy in the Papal States. For instance, the city of Rome maintained the last Jewish ghetto in Western Europe. There were hopes that this would change when Pope Pius IX was elected to succeed Gregory and began to introduce liberal reforms.

Italian nationalism and the end of the Papal States

Italian nationalism had been stoked during the Napoleonic period but dashed by the settlement of the Congress of Vienna (1814–15), which sought to restore the pre-Napoleonic conditions: most of northern Italy was under the rule of junior branches of the Habsburgs and the Bourbons, with the House of Savoy in Sardinia-Piedmont constituting the only independent Italian state. The Papal States in central Italy and the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south were both restored. Popular opposition to the reconstituted and corrupt clerical government led to numerous revolts, which were suppressed by the intervention of the Austrian army.

In 1848, nationalist and liberal revolutions began to break out across Europe; in February 1849, a Roman Republic was declared,[31] and the hitherto liberally-inclined Pope Pius IX had to flee the city. The revolution was suppressed with French help in 1850 and Pius IX switched to a conservative line of government.

As a result of the Austro-Sardinian War of 1859, Sardinia-Piedmont annexed Lombardy, while Giuseppe Garibaldi overthrew the Bourbon monarchy in the south.[32][33] Afraid that Garibaldi would set up a republican government, the Piedmont government petitioned French Emperor Napoleon III for permission to send troops through the Papal States to gain control of the south. This was granted on the condition that Rome be left undisturbed. In 1860, with much of the region already in rebellion against Papal rule, Sardinia-Piedmont conquered the eastern two-thirds of the Papal States and cemented its hold on the south. Bologna, Ferrara, Umbria, the Marches, Benevento and Pontecorvo were all formally annexed by November of the same year. While considerably reduced, the Papal States nevertheless still covered the Latium and large areas northwest of Rome.

A unified Kingdom of Italy was declared and in March 1861, the first Italian parliament, which met in Turin, the old capital of Piedmont, declared Rome the capital of the new Kingdom. However, the Italian government could not take possession of the city because a French garrison in Rome protected Pope Pius IX. The opportunity for the Kingdom of Italy to eliminate the Papal States came in 1870; the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in July prompted Napoleon III to recall his garrison from Rome and the collapse of the Second French Empire at the Battle of Sedan deprived Rome of its French protector. King Victor Emmanuel II at first aimed at a peaceful conquest of the city and proposed sending troops into Rome, under the guise of offering protection to the pope. When the pope refused, Italy declared war on September 10, 1870, and the Italian Army, commanded by General Raffaele Cadorna, crossed the frontier of the papal territory on September 11 and advanced slowly toward Rome. The Italian Army reached the Aurelian Walls on September 19 and placed Rome under a state of siege. Although the pope's tiny army was incapable of defending the city, Pius IX ordered it to put up at least a token resistance to emphasize that Italy was acquiring Rome by force and not consent. This incidentally served the purposes of the Italian State and gave rise to the myth of the Breach of Porta Pia, in reality a tame affair involving a cannonade at close range that demolished a 1600-year-old wall in poor repair. The city was captured on September 20, 1870. Rome and what was left of the Papal States were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy as a result of a plebiscite the following October. This marked the definite end of the Papal States.[30]

Despite the fact that the traditionally Catholic powers did not come to the pope's aid, the papacy rejected any substantial accommodation with the Italian Kingdom, especially any proposal which required the pope to become an Italian subject. Instead the papacy confined itself (see Prisoner in the Vatican) to the Apostolic Palace and adjacent buildings in the loop of the ancient fortifications known as the Leonine City, on Vatican Hill. From there it maintained a number of features pertaining to sovereignty, such as diplomatic relations, since in canon law these were inherent in the papacy. In the 1920s, the papacy – then under Pius XI—renounced the bulk of the Papal States and the Lateran Treaty with Italy (then ruled by the National Fascist Party under Benito Mussolini[34]) was signed on February 11 1929,[34] creating the State of the Vatican City, forming the sovereign territory of the Holy See, which was also indemnified to some degree for loss of territory.

Regional governors

As the plural name Papal States indicates, the various regional components retained their identity under papal rule. The pope was represented in each province by a governor, either styled papal legate, as in the former principality of Benevento, or Bologna, Romagna, and the March of Ancona; or papal delegate, as in the former duchy of Pontecorvo and in the Campagne and Maritime Province.

Papal army

Historically the Papal States maintained military forces composed of volunteers and mercenaries. Between 1860 and 1870 the Papal Army (l'Esercito Pontificio) comprised two regiments of locally recruited Italian infantry, two Swiss regiments and a battalion of Irish volunteers, plus artillery and dragoons.[35] In 1861 an international Catholic volunteer corps, called Papal Zouaves after a kind of French colonial native Algerian infantry, and imitating their uniform type, was created. Predominantly made up of Dutch, French and Belgian volunteers, this corps saw service against Garibaldi's Redshirts, local brigands, and finally the forces of the newly united Italy.[36]

The Papal Army was disbanded in 1870, leaving only the Palatine Guard, which was itself disbanded on 14 September 1970 by Pope Paul VI,[37] and the Swiss Guard, which continues to serve both as a ceremonial unit at the Vatican and as the pope's protective force.

See also

- Captain General of the Church

- Donation of Constantine

- History of Rome

- Holy Roman Empire

- Italian unification

- Italian United Provinces

- Prisoner in the Vatican

- War of the Eight Saints

- Index of Vatican City-related articles

References

- ^ Mitchell, S.A. (1840). Mitchell's geographical reader. Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co. p. 368.

- ^ a b c Schnürer, Gustav. "States of the Church." Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 16 July 2014

- ^ McEvedy, Colin (1961). The Penguin atlas of medieval history. Penguin Books. p. 32.

(...) separated from their theoretical overlord in Pavia by the continuing Imperial control of the Rome-Ravenna corridor.

- ^ Freeman, Charles (2014). Egypt, Greece, and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean. OUP Oxford. p. 661. ISBN 978-0199651924.

The empire retained control only of Rome, Ravenna, a fragile corridor between them, (...)

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey (2014). The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages: 476-752. Routledge. p. 230. ISBN 978-1317678175.

In 749 Ratchis embarked on a bid to capture Perusia, the key to the Rome-Ravenna land corridor

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 378.

- ^ Kleinhenz 2004, p. 1060.

- ^ "Sutri". From Civitavecchia to Civita Castellana. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Kleinhenz 2004, p. 324.

- ^ Emile Amann and Auguste Dumas, ""L'église au pouvoir des laïques", in Auguste Fliche and Victor Martin, eds. Histoire de l'Église depuis l'origine jusqu'au nos jours, vol. 7 (Paris 1940, 1948)

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 332.

- ^ Spielvogel 2013, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Elm & Mixson 2015, p. 154.

- ^ Watanabe 2013, p. 241.

- ^ Kleinhenz 2004, pp. 220, 982.

- ^ Noble; et al. (2013). Cengage Advantage Books: Western Civilization: Beyond Boundaries (7 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 304. ISBN 978-1285661537.

The Babylonian Captivity, 1309-1377

- ^ Butt, John J. (2006). The Greenwood Dictionary of World History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 36. ISBN 978-0313327650.

Term (coined by Petrarch) for the papal residence in Avignon (1309-1377), in reference to the Babylonian Captivity (...)

- ^ Menache 2003, p. 142.

- ^ Waley 1966, p. 62.

- ^ Kleinhenz 2004, p. 802.

- ^ Ruggiero 2014, p. 225.

- ^ a b c Ruggiero 2014, p. 227.

- ^ Watanabe 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Ganse, Alexander. "History of the Papal States". World History at KDMLA. Korean Minjok Leadership Academy. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^

Durant, Will (1953). The Renaissance. Chapter XXI: The Political Collapse: 1494–1534.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Durant, Will (1953). The Renaissance. Chapter XXXIX: The popes and the Council: 1517–1565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hanlon 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Domenico 2002, p. 85.

- ^ Gross 2004, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hanson 2015, p. 252.

- ^ Roessler & Miklos 2003, p. 149.

- ^ Fischer 2011, p. 136.

- ^ Abulafia, David (2003). "The Mediterranean as a battleground". The Mediterranean in History. Getty Publication. p. 268. ISBN 978-0892367252.

(...) under Giuseppe Garibaldi to overthrow the Neapolitan Bourbons. After defeating a Neapolitan force at Calatafirmi, Caribaldi captured Palermo after three days of street fighting.

- ^ a b De Grand 2004, p. 89.

- ^ Massimo Brandani, page 6, L'Esercito Pontificio da Castelfidardo a Porta Pia, published 1976 by Intergest Milano

- ^ Charles A. Coulombe, The Pope's Legion: The Multinational Fighting Force that Defended the Vatican, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2008

- ^ Levillain 2002, p. 1095.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "States of the Church". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "States of the Church". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Chambers, D.S. 2006. Popes, Cardinals & War: The Military Church in Renaissance and Early Modern Europe. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-178-8. [sic]

- De Cesare, Raffaele (1909). The Last Days of Papal Rome. London: Archibald Constable & Co.

- De Grand, Alexander J. (2004). Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: The "fascist" Style of Rule. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415336314.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Domenico, Roy Palmer (2002). The Regions of Italy: A Reference Guide to History and Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313307331.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Elm, Kaspar; Mixson, James D. (2015). Religious Life between Jerusalem, the Desert, and the World: Selected Essays by Kaspar Elm. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004307780.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fischer, Conan (2011). Europe between Democracy and Dictatorship: 1900 - 1945. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1444351453.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gross, Hanns (2004). Rome in the Age of Enlightenment: The Post-Tridentine Syndrome and the Ancien Régime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521893787.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hanlon, Gregory (2008). The Twilight Of A Military Tradition: Italian Aristocrats And European Conflicts, 1560-1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135361433.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hanson, Paul R. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0810878921.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kleinhenz, Christopher (2004). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135948801.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levillain, Philippe (2002). The Papacy: Gaius-Proxies. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415922302.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Luther, Martin (1521). Passional Christi und Antichristi. Reprinted in W.H.T. Dau (1921). At the Tribunal of Caesar: Leaves from the Story of Luther's Life. St. Louis: Concordia. (Google Books)

- Menache, Sophia (2003). Clement V. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0521521987.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roessler, Shirley Elson; Miklos, Reny (2003). Europe 1715-1919: From Enlightenment to World War. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742568792.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ruggiero, Guido (2014). The Renaissance in Italy: A Social and Cultural History of the Rinascimento. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1316123270.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2013). Western Civilization: A Brief History (8 ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1133606765.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804726306.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851096725.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waley, Daniel Philip (1966). Rearder, Harry (ed.). "A Short History of Italy: From Classical Times to Present Day". University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watanabe, Morimichi (2013). Izbicki, Thomas M.; Christianson, Gerald (eds.). Nicholas of Cusa – A Companion to his Life and his Times. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1409482-536.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)