Ravi Shankar

Ravi Shankar |

|---|

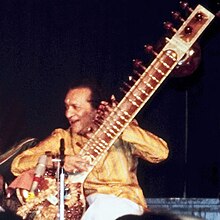

Ravi Shankar (Bengali: রবি শংকর; born 7 April 1920), often referred to by the title Pandit, is an Indian musician and composer who plays the plucked string instrument Sitar. He has been described as the most well known contemporary Indian musician by Hans Neuhoff of Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart.[1]

Shankar was born in Varanasi and spent his youth touring Europe and India with the dance group of his brother Uday Shankar. He gave up dancing in 1938 to study sitar playing under court musician Allauddin Khan. After finishing his studies in 1944, Shankar worked as a composer, creating the music for the Apu Trilogy by Satyajit Ray, and was music director of All India Radio, New Delhi, from 1949 to 1956.

In 1956, he began to tour Europe and America playing Indian classical music and increased its popularity there in the 1960s through teaching, performance, and his association with violinist Yehudi Menuhin and George Harrison of The Beatles. Shankar engaged Western music by writing concerti for sitar and orchestra and toured the world in the 1970s and 1980s. From 1986 to 1992 he served as a nominated member of the upper chamber of the Parliament of India. Shankar was awarded India's highest civilian honor, the Bharat Ratna, in 1999, and received three Grammy Awards. He continues to perform in the 2000s, often with his daughter Anoushka.

Early life

Shankar was born 7 April 1920 in Varanasi to a wealthy and conservative Brahmin family of cultured Bengalis as the youngest of seven brothers, of whom four lived when he was born.[2][3][4] Shankar's Bengali birth name was Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury.[2] His father, Shyam Shankar, an administrator for the Maharaja of Jhalawar, used the Sanskrit spelling of the family name and removed its last part.[2][5] Shyam was married to Shankar's mother Hemangini Devi, but later worked as a lawyer in London.[2] There he married a second time while Devi raised Shankar in Varanasi, and did not meet his son until he was eight years old.[2] Shankar shortened the Sanskrit version of his first name, Ravindra, to Ravi, for "sun".[2]

At the age of ten, after spending his first decade in Varanasi, Shankar went to Paris with the dance group of his brother, choreographer Uday Shankar.[6][7] By the age of 13 he had become a member of the group, accompanied its members on tour and learned to dance and play various Indian instruments.[3][4] Uday's dance group toured Europe and America in the early to mid-1930s and Shankar learned French, discovered Western classical music, jazz, and cinema, and became acquainted with Western customs.[8] Shankar heard the lead musician for the Maihar court, Allauddin Khan, in December 1934 at a music conference in Kolkata and Uday convinced the Maharaja of Maihar in 1935 to allow Khan to become his group's soloist for a tour of Europe.[8] Shankar was sporadically trained by Khan on tour, and Khan offered Shankar training to become a serious musician under the condition that he abandoned touring and came to Maihar.[8]

Career

Training and work in India

Shankar's parents had died by the time he returned from the European tour, and touring the West had become difficult due to political conflicts that would lead to World War II.[9] Shankar gave up his dancing career in 1938 to go to Maihar and study Indian classical music as Khan's pupil, living with his family in the traditional gurukul system.[6] Khan was a rigorous teacher and Shankar had training on sitar and surbahar, learned ragas and the musical styles dhrupad, dhamar, and khyal, and was taught the techniques of the instruments rudra veena, rubab, and sursingar.[6][10] He often studied with Khan's children Ali Akbar Khan and Annapurna Devi.[9] Shankar began to perform publicly on sitar in December 1939 and his debut performance was a jugalbandi (duet) with Ali Akbar Khan, who played the string instrument sarod.[11]

Shankar completed his training in 1944.[3] Following his training, he moved to Mumbai and joined the Indian People's Theatre Association, for whom he composed music for ballets in 1945 and 1946.[3][12] Shankar recomposed the music for the popular song "Sare Jahan Se Achcha" at the age of 25.[13][14] He began to record music for HMV India and worked as a music director for All India Radio (AIR), New Delhi, from February 1949 to January 1956.[3] Shankar composed for the Indian National Orchestra and his compositions experimented with a combination of Western instruments and classical Indian instrumentation.[15] Beginning in the mid-1950s he composed the music for the Apu Trilogy by Satyajit Ray, which became internationally acclaimed.[4][16]

International career 1956–1969

V. K. Narayana Menon, director of AIR Delhi, introduced the Western violinist Yehudi Menuhin to Shankar during Menuhin's first visit to India in 1952.[17] Shankar had performed as part of a cultural delegation in the Soviet Union in 1954 and Menuhin invited Shankar in 1955 to perform in New York City for a demonstration of Indian classical music, sponsored by the Ford Foundation.[18][19] Shankar declined to attend due to problems in his marriage, but recommended Ali Akbar Khan to play instead.[19] Khan reluctantly accepted and performed with tabla (percussion) player Chatur Lal in the Museum of Modern Art, and he later became the first Indian classical musician to perform on American television and record a full raga performance, for Angel Records.[20]

Shankar heard about the positive response Khan received and resigned from AIR in 1956 to tour the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States.[21] He played for smaller audiences and educated them about Indian music, incorporating ragas from the South Indian Carnatic music in his performances, and recorded his first LP album Three Ragas in London, released in 1956.[21] In 1958, Shankar participated in the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the United Nations and UNESCO music festival in Paris.[12] Since 1961, he toured Europe, the United States, and Australia, and became the first Indian to compose music for non-Indian films.[12] Chatur Lal accompanied Shankar on tabla until 1962, when Alla Rakha assumed the role.[21]

Shankar befriended Richard Bock, founder of World Pacific Records, on his first American tour and recorded most of his albums in the 1950s and 1960s for Bock's label.[21] The Byrds recorded at the same studio and heard Shankar's music, which led them to incorporate some of its elements in theirs, introducing the genre to their friend George Harrison of The Beatles.[22] Harrison became interested in Indian classical music, bought a sitar and used it to record the song "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)".[23] This led to Indian music being used by other musicians and created the raga rock trend.[23]

Harrison met Shankar in London in 1966 and visited India for six weeks to study sitar under Shankar in Srinagar.[14][24][25] During the visit, a documentary film about Shankar named Raga was shot by Howard Worth, and released in 1971.[26] Shankar's association with Harrison greatly increased Shankar's popularity and Ken Hunt of Allmusic would state that Shankar had become "the most famous Indian musician on the planet" by 1966.[3][24] In 1967, he performed at the Monterey Pop Festival and won a Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance for West Meets East, a collaboration with Yehudi Menuhin.[24][27] The same year, the Beatles won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band which included "Within You Without You" by Harrison, a song that was influenced by Indian classical music.[25][27] Shankar opened the Kinnara School of Music in Los Angeles, California, in May 1967,[12] and published a best-selling autobiography, My Music, My Life, in 1969.[4][13] He performed at the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, and found he disliked the venue.[24] In the 1970s Shankar distanced himself from the hippie movement.[28]

International career 1970–present

In October 1970 Shankar became chair of the department of Indian music of the California Institute of the Arts after previously teaching at the City College of New York, the University of California, Los Angeles, and being guest lecturer at other colleges and universities, including the Ali Akbar College of Music.[12][29][30] In late 1970, the London Symphony Orchestra invited Shankar to compose a concerto with sitar; Concerto for Sitar and Orchestra was performed with André Previn as conductor and Shankar playing the sitar.[4][31] Hans Neuhoff of Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart has criticized the usage of the orchestra in this concert as "amateurish".[1] George Harrison organized the charity Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, in which Shankar participated.[24] Interest in Indian music had decreased in the early 1970s, but the concert album became one of the best-selling recordings featuring it and won Shankar a second Grammy Award.[27][30]

During the 1970s, Shankar and Harrison worked together again, recording Shankar Family and Friends in 1974 and touring North America to a mixed response after Shankar had toured Europe.[32] The touring band visited the White House on invitation of John Gardner Ford, son of U.S. President Gerald Ford.[33] The demanding North America tour weakened Shankar, and he suffered a heart attack in Chicago in September 1974, causing him to cancel a portion of the tour.[33] In his absence, Shankar's sister-in-law, singer Lakshmi Shankar, conducted the touring orchestra.[33] Shankar toured and taught for the remainder of the 1970s and the 1980s and released his second concerto, Raga Mala, conducted by Zubin Mehta, in 1981.[34][35] Shankar was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Music Score for his work on the 1982 movie Gandhi, but lost to John Williams' E.T.[36] He served as a member of the Rajya Sabha, the upper chamber of the Parliament of India, from 1986 to 1992, after being nominated by Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.[14] His liberal views on musical cooperation led him to collaboration with contemporary composer Philip Glass, with whom he released an album, Passages, in 1990.[6]

Shankar underwent an angioplasty in 1992 due to heart problems, after which George Harrison involved himself in several of Shankar's projects.[37] Because of the positive response to Shankar's 1996 career compilation In Celebration, Shankar wrote a second autobiography, Raga Mala, with Harrison as editor.[37] He performed in between 25 and 40 concerts every year during the late 1990s.[6] Shankar taught his daughter Anoushka Shankar to play sitar and in 1997 became a Regent's Lecturer at University of California, San Diego.[38] In the 2000s, he won a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album for Full Circle: Carnegie Hall 2000 and toured with Anoushka, who released a book about her father, Bapi: Love of My Life, in 2002.[27][39] Anoushka performed a composition by Shankar for the 2002 Harrison memorial Concert for George and Shankar wrote a third concerto for sitar and orchestra for Anoushka and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra.[40][41] Shankar played his last European concert in June 2008.[28]

Style and contributions

Shankar developed a style distinct from that of his contemporaries and incorporated influences from rhythm practices of Carnatic music.[6] His performances begin with solo alap, jor, and jhala (introduction and performances with pulse and rapid pulse) influenced by the slow and serious dhrupad genre, followed by a section with tabla accompaniment featuring compositions associated with the prevalent khyal style.[6] Shankar often closes his performances with a piece inspired by the light-classical thumri genre.[6]

Shankar has been considered one of the top sitar players of the second half of the 20th century.[1] Shankar popularized performing on the bass octave of the sitar for the alap section, became known for a distinctive quick playing style in the middle and high registers, and his sound creation through stops and strikes on the main playing string.[1][6] Hans Neuhoff of Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart has argued that Shankar's playing style was not widely adopted and that he was surpassed by other sitar players in the performance of melodic passages.[1] Shankar's interplay with Alla Rakha improved appreciation for tabla playing in Hindustani classical music.[1] He promoted the jugalbandi duet concert style and introduced new ragas, including Tilak Shyam, Nat Bhairav and Bairagi.[6]

Recognition

Shankar was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1962,[42] and became a fellow of the academy in 1975.[43] He was awarded the three highest national civil honors of India: Padma Bhushan, in 1967, Padma Vibhushan, in 1981, and Bharat Ratna, in 1999.[44] Shankar received the music award of the UNESCO International Music Council in 1975, three Grammy Awards, and was nominated for an Academy Award.[12][27][36] He was awarded honorary degrees from universities in India and the United States.[12] Shankar received the Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize in 1991, the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1992, and the Polar Music Prize in 1998.[45][46][47] He is an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and received the Praemium Imperiale for music from the Japan Art Association.[6]

Personal life and family

Shankar married Allauddin Khan's daughter Annapurna Devi in 1941 and a son, Shubhendra Shankar, was born in 1942.[10] Shankar separated from her in the 1940s and had a relationship with Kamala Shastri, a dancer, beginning in the late 1940s.[48] An affair with Sue Jones, a New York concert producer, led to the birth of Norah Jones in 1979.[48] In 1981, Anoushka Shankar was born to Shankar and Sukanya Rajan, whom Shankar had known since the 1970s.[48] After separating from Kamala Shastri in 1981 Shankar lived with Sue Jones until 1986 and married Sukanya Rajan in 1989.[48]

Shubhendra "Shubho" Shankar often accompanied his father on his tours.[49] He could play the sitar and surbahar, but elected not to pursue a solo career and died in 1992.[49] Norah Jones became a successful musician in the 2000s, winning eight Grammy Awards in 2003.[50] Anoushka Shankar was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album in 2003.[50]

Shankar is a Hindu and a vegetarian.[51][52] He lives with Sukanya in Southern California.[28]

Discography

Bibliography

- Shankar, Ravi (1969). My Music, My Life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671201131.

- Shankar, Ravi (1979). Learning Indian Music: A Systematic Approach. Onomatopoeia.

- Shankar, Ravi (1997). Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar. Genesis Publications. ISBN 0904351467.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Neuhoff, Hans (2006). "Shankar, Ravi". In Finscher, Ludwig (ed.). Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik (in German). Vol. 15 (2nd ed.). Bärenreiter. pp. 672–673. ISBN 3761811225.

- ^ a b c d e f Lavezzoli, Peter (2006). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 0826418155.

- ^ a b c d e f Hunt, Ken. "Ravi Shankar – Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Massey, Reginald (1996). The Music of India. Abhinav Publications. p. 159. ISBN 8170173329.

- ^ Ghosh, Dibyendu (1983). "A Humble Homage to the Superb". In Ghosh, Dibyendu (ed.). The Great Shankars. Kolkata: Agee Prakashani. p. 7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Slawek, Stephen (2001). "Shankar, Ravi". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove dictionary of music and musicians. Vol. 23 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. pp. 202–203. ISBN 0333608003.

- ^ Ghosh, Dibyendu (1983). "Ravishankar". In Ghosh, Dibyendu (ed.). The Great Shankars. Kolkata: Agee Prakashani. p. 55.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 50

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 51

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 52

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 53

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghosh 1983, p. 57

- ^ a b Sharma, Vishwamitra (2007). Famous Indians of the 20th Century. Pustak Mahal. pp. 163–164. ISBN 8122308295.

- ^ a b c Deb, Arunabha (26 February 2009). "Ravi Shankar: 10 interesting facts". Mint. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 56

- ^ "The Apu Trilogy - ALL-TIME 100 movies". TIME. 2005. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 47

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 57

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 58

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b c d Lavezzoli 2006, p. 61

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 62

- ^ a b Schaffner, Nicholas (1980). The boys from Liverpool: John, Paul, George, Ringo. Taylor and Francis. p. 64. ISBN 0416306616.

- ^ a b c d e Glass, Philip (9 December 2001). "George Harrison, World-Music Catalyst And Great-Souled Man; Open to the Influence Of Unfamiliar Cultures". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Kozinn, Allan (30 November 2001). "George Harrison, Former Beatle, Dies at 58". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Thompson, Howard (24 November 1971). "Screen: Ravi Shankar; ' Raga,' a Documentary, at Carnegie Cinema". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e "Grammy Award Winners". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ a b c O'Mahony, John (8 June 2008). "Ravi Shankar bids Europe adieu". The Guardian. Taipei Times. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Ghosh 1983, p. 56

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 66

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 221

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 195

- ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 196

- ^ Rogers, Adam (8 August 1994). "Where Are They Now?". Newsweek. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 222

- ^ a b "Ravi Shankar remains true to his Eastern musical ethos". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. 19 April 2005. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 197

- ^ "Shankar advances her music". The Washington Times. 16 November 1999. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 411

- ^ Idato, Michael (9 April 2004). "Concert for George". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Anoushka enthralls at New York show". Press Trust of India. The Hindu. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "SNA: List of Akademi Awardees – Instrumental – Sitar". Sangeet Natak Akademi. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ "SNA: List of Akademi Fellows". Sangeet Natak Akademi. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ "Padma Awards". Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar – The 2nd Fukuoka Asian Culture Prizes 1991". Asian Month. 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Citation for Ravi Shankar". Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ van Gelder, Lawrence (14 May 1998). "Footlights". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d "Hard to say no to free love: Ravi Shankar". Press Trust of India. Rediff.com. 13 May 2003. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b Lindgren, Kristina (21 September 1992). "Shubho Shankar Dies After Long Illness at 50". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Venugopal, Bijoy (24 February 2003). "Norah's night at the Grammys". Rediff.com. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ Melwani, Lavina (24 December 1999). "In Her Father's Footsteps". Rediff.com. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Signing up for the veg revolution". Screen. 8 December 2000. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

External links

- "Ravi Shankar". Official website.

- Ravi Shankar at AllMusic

- Ravi Shankar at IMDb

- Films scored by Anoushka Shankar

- 1920 births

- Apple Records artists

- Bengali musicians

- Former Nominated Rajya Sabha members

- Grammy Award winners

- Hindustani instrumentalists

- Indian composers

- Indian film score composers

- Indian Hindus

- Indian vegetarians

- Living people

- Maihar Gharana

- People from Varanasi

- Polar Music Prize laureates

- Ramon Magsaysay Award winners

- Recipients of the Bharat Ratna

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan

- Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan

- Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award

- Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship

- Sitar players