Resistance during World War II

Template:WorldWarIISegmentUnderInfoBox

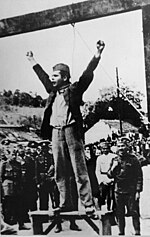

Resistance during World War II occurred in every occupied country by a variety of means, ranging from non-cooperation, disinformation and propaganda to hiding crashed pilots and even to outright warfare and the recapturing of towns. Resistance movements are sometimes also referred to as "the underground".

Among the most notable resistance movements were the Yugoslav Partisans (the largest resistance movement in World War II),[1][2] the Polish Home Army, the Soviet partisans, the French Forces of the Interior, the Italian CLN, the Norwegian Resistance, the Greek Resistance and the Dutch Resistance

Many countries had resistance movements dedicated to fighting the Axis invaders, and Germany itself also had an anti-Nazi movement. Although Britain did not suffer the Nazi occupation in World War II, the British made preparations for a British resistance movement, called the Auxiliary Units, in the event of a German invasion. Various organisations were also formed to establish foreign resistance cells or support existing resistance movements, like the British SOE and the American OSS (the forerunner of the CIA).

There were also resistance movements fighting against the Allied invaders. In Italian East Africa, after the Italian forces were defeated during the East African Campaign, some Italians participated in a guerrilla war against the British (1941 to 1943). The German Nazi resistance movement ("Werwolf") never amounted to much. On the other hand, the "Forest Brothers" of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania included many fighters who fought for the Nazis and operated against the Soviet occupation of the Baltic States into the 1960s. During or after the war, similar anti-Soviet resistance rose up in places like Romania, Poland, and western Ukraine. While the Japanese were famous for "fighting to the last man," Japanese holdouts tended to be individually motivated and there is little indication that there was any organized Japanese resistance after the war.

Organization

After the first shock following the Blitzkrieg, people slowly started to get organized, both locally and on a larger scale, especially when Jews and other groups were starting to be deported and used for the Arbeitseinsatz (forced labour for the Germans). Organisation was dangerous, so much resistance was done by individuals. The possibilities depended much on the terrain; where there were large tracts of uninhabited land, especially hills and forests, resistance could more easily get organised undetected. This favoured in particular the Soviet partisan in Eastern Europe. In the much more densely populated Netherlands, the Biesbosch wilderness could be used to go into hiding. In northern Italy, both the Alps and the Appennines offered shelter to partisan brigades, though many groups operated directly inside the major cities.

There were many different types of groups, ranging in activity from humanitarian aid to armed resistance, and sometimes cooperating to a varying degree. Resistance usually arose spontaneously, but was encouraged and helped mainly from London and Moscow.

Forms of resistance

Various forms of resistance were:

- Non-violent

- Sabotage – the Arbeitseinsatz ("Work Contribution") forced locals to work for the Germans, but work was often done slowly or intentionally badly

- Strikes and demonstrations

- Based on existing organizations, such as the churches, students, communists and doctors (professional resistance)

- Armed

- raids on distribution offices to get food coupons or various documents such as Ausweise or on birth registry offices to get rid of information about Jews and others the Nazis paid special attention to

- temporary liberation of areas, such as in Yugoslavia, Paris, and northern Italy, occasionally in cooperation with the Allied forces

- uprisings such as in Warsaw in 1943 and 1944

- continuing battle and guerrilla warfare, such as the partisans in the USSR and Yugoslavia and the Maquis in France

- Espionage, including sending reports of military importance (e.g. troop movements, weather reports etc.)

- Illegal press to counter the Nazi propaganda

- Political resistance to prepare for the reorganization after the war

- Helping people to go into hiding (e.g. to escape the Arbeitseinsatz or deportation) – this was one of the main activities in the Netherlands, due to the large number of Jews and the high level of administration, which made it easy for the Germans to identify Jews.

- Helping Allied military personnel caught behind Axis lines

- Helping POWs with illegal supplies, breakouts, communication etc.

- Forgery of documents

Famous resistance operations

1940

In March 1940 partisan unit of the first guerrilla commanders in the Second World War in Europe - Henryk Dobrzański "Hubal" completely destroyed a battalion of German infantry in a skirmish near the village of Huciska. A few days later in an ambush near the village of Szałasy it inflicted heavy casualties upon another German unit. To counter this threat the German authorities formed a special 1,000 men strong anti-partisan unit of combined SS-Wehrmacht forces, including a Panzer group. Although the unit of maj. Dobrzański never exceeded 300 men, the Germans fielded at least 8,000 men in the area to secure it.[3][4]

In 1940, Witold Pilecki, member of Polish resistance, presented to his superiors a plan to enter Germany's Auschwitz concentration camp, gather intelligence on the camp from the inside, and organize inmate resistance.[5] Home Army approved this plan, provided him a false identity card, and on September 19, 1940, he deliberately went out during a street roundup in Warsaw - łapanka, and was caught by the Germans along with other civilians and sent to Auschwitz.In the camp He organized the underground organization -Związek Organizacji Wojskowej - ZOW.[6] From October 1940, ZOW sent first report about camp and genocide in November 1940 to Polish resistance Home Army Headquarters in Warsaw through the resistance network organized in Auschwitz.[7]

1941

From April 1941 Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Union for Armed Struggle started in Poland Operation N headed by Tadeusz Żenczykowski. Action was complex of sabotage, subversion and black-propaganda activities carried out by the Polish resistance against Nazi German occupation forces during World War II[8]

Beginning with March 1941, Witold Pilecki's reports were being forwarded via the Polish resistance to the Polish government in exile and through it, to the British government in London and other Allied governments. These reports were the first relation about Holocaust and principal source of intelligence on Auschwitz for the Western Allies.[9]

In February 1941, the Dutch Communist Party organized a general strike in Amsterdam and surrounding cities, known as the February strike, in protest against anti-Jewish measures by the Nazi occupying force and violence by fascist street fighters against Jews. Several hundreds of thousands of people participated in the strike. The strike was put down by the Nazis and some participants were executed.

The first World War II armed resistance unit in occupied Europe was formed on June 22 1941 (the start-date of Operation Barbarossa) in the Brezovica forest near Sisak, Croatia by the Yugoslav partisans. This launched the largest, and arguably the most successful resistance movement in Europe, as well as marking the beginning of the Yugoslav People's Liberation War.

On 13 July 1941 in Italian-occupied Montenegro Montenegrin separatist Sekula Drljević proclaimed an Independent State of Montenegro under Italian protectorate, upon which a nation-wide rebellion escalated raised by Partisans, Yugoslav Royal officers and various other armed personnel. In quick time most of Montenegro was liberated, but on 12 August 1941 after a major Italian offensive the uprising collapsed as units were disintegrating, poor leadership occurred as well as collaboration.

Operation Anthropoid was a resistance move during the World War II to assassinate Reinhard Heydrich, the Nazi “Protector of Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” and the chief of Nazi's final solution, by the Czech resistance in Prague. Over fifteen thousand Czechs were killed in reprisals, with the most infamous incidents being the complete destruction of the towns of Lidice and Ležáky.

1942

On 25 November 1942, Greek guerrillas with the help of twelve British saboteurs[10] carried out a successful operation which disrupted the German ammunition transportation to the German Africa Corps under Rommel – the destruction of Gorgopotamos bridge (Operation Harling).[11][12]

The Zamość Uprising was an armed uprising of Armia Krajowa and Bataliony Chłopskie) against the forced expulsion of Poles from the Zamość region (Zamość Lands, Zamojszczyzna) under the Nazi Generalplan Ost. Nazi Germans attempting to remove the local Poles from the Greater Zamosc area (through forced removal, transfer to forced labor camps, or, in rare cases, mass murder) to get it ready for German colonization. It lasted from 1942 until 1944 and despite heavy casualties suffered by the Underground, the Germans failed. [13]

1943

In early January 1943, the 20,000 strong main operational group of the Yugoslav Partisans, stationed in western Bosnia, came under ferocious attack by over 150,000 German and Axis troops, supported by about 200 Luftwaffe aircraft in what became known as the Battle of the Neretva (the German codename was "Fall Weiss" or "Case White").[14] The Axis rallied eleven divisions, six German, three Italian, and two divisions of the puppet Independent State of Croatia (supported by Ustaše formations) as well as a number of Chetnik brigades.[15] The goal was to destroy the Partisan HQ and main field hospital (all Partisan wounded and prisoners faced certain execution), but this was thwarted by the diversion and retreat across the Neretva river, planned by the Partisan supreme command led by Marshal Josip Broz Tito. The main Partisan force escaped into Serbia where it immediately took the offensive and succeeded in eliminating the Chetnik movement as a fighting force.

On April 19 1943 three members of the Belgian resistance movement were able to stop the Twentieth convoy, which was the 20th prisoner transport in Belgium organised by the Germans during World War II. The exceptional action by members of the Belgian resistance occurred to free Jewish and gypsy civilians who were being transported by train from the Dossin army base located in Mechelen, Belgium to the concentration camp Auschwitz. The XXth train convoy transported 1,631 Jews (men, women and children). Some of the prisoners were able to escape and marked this kind of liberation action from the Belgian resistance movement unique in the European history of the Holocaust. In October the rescue of the Danish Jews meant that nearly all of the Danish Jews were saved from KZ camps by the Danish resistance. This action is considered one of the bravest and most significant displays of public defiance against the Nazis.

On March 26, 1943 in Warsaw took place Operation Arsenal by the Szare Szeregi (Gray Ranks) Polish Underground formation successfully conducted operation led to the release of arrested troop leader Jan Bytnar "Rudy". In an attack on the prison van Bytnar and 24 other prisoners was free. [16]

The Battle of Sutjeska from 15 May to 16 June 1943 was a joint attack of the Axis forces that once again attempted to destroy the main Yugoslav Partisan force, near the Sutjeska river in southeastern Bosnia. The Axis rallied 127,000 troops for the offensive, including German, Italian, NDH, Bulgarian and Cossack units, as well as over 300 airplanes (under German operational command), against 18,000 soldiers of the primary Yugoslav Partisans operational group organised in 16 brigades.

Facing almost exclusively German troops in the final encirclement, the Yugoslav Partisans finally succeeded in breaking out across the Sutjeska river through the lines of the German 118th Jäger Division, 104th Jäger Division and 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division in the northwestern direction, towards eastern Bosnia. Three brigades and the central hospital with over 2,000 wounded remained surrounded and, following Hitler's instructions, German commander-in-chief General Alexander Löhr ordered and carried out their annihilation, including the wounded and unarmed medical personnel. In addition, Partisan troops suffered from severe lack of food and medical supplies, and many were struck down by typhoid. However, the failure of the offensive marked a turning point for Yugoslavia during World War II.

Home Army kills Franz Bürkl during Operation Bürkl in 1943, and Franz Kutschera during Operation Kutschera in 1944. Both men are high ranking Nazi German SS and secret police officers responsible for murder and brutal interrogation of thousands of the Polish Jews and the Polish resistance fighters and supporters.

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising lasted from April 19 to May 16, and did cost the Nazi forces 17 dead and 93 wounded.

From November 1943, Operation Most III started. The Armia Krajowa provided the Allies with crucial intelligence on the German V-2 rocket. In effect some 50 kg of the most important parts of the captured V-2, as well as the final report, analyses, sketches and photos, were transported to Brindisi by a Royal Air Force Douglas Dakota aircraft. In late July 1944, the V-2 parts were delivered to London.[17]

1944

On 11th February 1944 the Resistance fighters of Polish Home Army's unit Agat executed Franz Kutschera, SS and Reich's Police Chief in Warsaw in action known as Operation Kutschera.[18][19]

In the spring of 1944, a plan was laid out by the Allies to kidnap General Müller, whose harsh repressive measures had earned him the nickname "the Butcher of Crete". The operation was led by Major Patrick Leigh Fermor, together with Captain W. Stanley Moss, Greek SOE agents and Cretan resistance fighters. However, Müller left the island before the plan could be carried out. Undeterred, Fermor decided to abduct General Heinrich Kreipe instead.

On the night of April 26, General Kreipe left his headquarters in Archanes and headed without escort to his well-guarded residence, "Villa Ariadni", approximately 25 km outside Heraklion. Major Fermor and Captain Moss, dressed as German military policemen, waited for him 1 km before his residence. They asked the driver to stop and asked for their papers. As soon as the car stopped, Fermor quickly opened Kreipe's door, rushed in and threatened him with his gun while Moss took the driver's seat. After driving some distance the British left the car, with suitable decoy material being planted that suggesting an escape off the island had been made by submarine, and with the General began a cross-country march. Hunted by German patrols, the group moved across the mountains to reach the southern side of the island, where a British Motor Launch (ML 842 commanded by Brian Coleman) was to pick them up. Eventually, on 14 May 1944 they were picked up (from Peristeres beach near Rhodakino) and transferred to Egypt.

During April and May 1944, the SS launched the daring airborne Raid on Drvar aimed at capturing Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the commander-in-chief of the Yugoslav Partisans, as well as disrupting their leadership and command structure. The Partisan headquarters were in the hills near Drvar, Bosnia at the time. The representatives of the Allies, Britain's Randolph Churchill and Evelyn Waugh, were also present.

Elite German SS parachute commando units fought their way to Tito's cave headquarters and exchanged heavy gunfire resulting in numerous casualties on both sides.[20] Interestingly, Chetniks under Draža Mihailović also flocked to the firefight in their own attempt to capture Tito. By the time German forces had penetrated to the cave, however, Tito had already fled the scene. He had a train waiting for him that took him to the town of Jajce. It would appear that Tito and his staff were well prepared for emergencies. The commandos were only able to retrieve Tito’s marshal's uniform, which was later displayed in Vienna. After fierce fighting in and around the village cemetery, the Germans were able to link up with mountain troops. By that time, Tito, his British guests and Partisan survivors were fêted aboard the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Blackmore and her captain Lt. Carson, RN.

An intricate series of resistance operations were launched in France prior to, and during, Operation Overlord. On June 5 1944, the BBC broadcasted a group of unusual sentences, which the Germans knew were code words – possibly for the invasion of Normandy. The BBC would regularly transmit hundreds of personal messages, of which only a few were really significant. A few days before D-Day, the commanding officers of the Resistance heard the first line of Verlaine's poem , "Chanson d'automne", "Les sanglots longs des violons de l'automne" (Long sobs of autumn violins) which meant that the "day" was imminent. When the second line "Blessent mon cœur d'une langueur monotone" (wound my heart with a monotonous langour) was heard, the Resistance knew that the invasion would take place within the next 48 hours. They then knew it was time to go about their respective pre-assigned missions. All over France resistance groups had been coordinated, and various groups throughout the country increased their sabotage. Communications were cut, trains derailed, roads, water towers and ammunition depots destroyed and German garrisons were attacked. Some relayed info about German defensive positions on the beaches of Normandy to American and British commanders by radio, just prior to 6 June. Victory did not come easily; in June and July, in the Vercors plateau a newly reinforced maquis group fought more than 10,000 German soldiers (no Waffen-SS) under General Karl Pflaum and was defeated, with 840 casualties (639 fighters and 201 civilians). Following Tulle Murders, Major Otto Diekmann's Waffen-SS company wiped out the village of Oradour-sur-Glane on June 10. The resistance also assisted the later Allied invasion in the south of France (Operation Dragoon). They started insurrections in cities as Paris when allied forces came close.

Operation Tempest launched in Poland in 1944 would lead to several major actions by Armia Krajowa, most notable of them being the Warsaw Uprising that took place in between August 1 and October 2, and failed due to the Soviet refusal, due to differences in ideology, to help; another one was Operation Ostra Brama: the Armia Krajowa or Home Army turned the weapons given to them by the nazi Germans (in hope that they would fight the incoming Soviets) against the nazi Germans—in the end the Home Army together with the Soviet troops liberated the Greater Vilnius area to the dismay of the Lithuanians.

On 25 June 1944 the Battle of Osuchy started - one of the largest battles between the Polish resistance and Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II, continuation of the Zamosc Uprising.[21] During Operation Most III, in 1944, the Polish Home Army or Armia Krajowa provided the British with the parts of the V-2 rocket.

Norwegian sabotages of the German nuclear program drew to a close after three years on February 20 1944, with the saboteur bombing of the ferry SF Hydro. The ferry was to carry railway cars with heavy water drums from the Vemork hydroelectric plant, where they were produced, across Lake Tinnsjø so they could be shipped to Germany. Its sinking effectively ended Nazi nuclear ambitions. The series of raids on the plant was later dubbed by the British SOE as the most successful act of sabotage in all of World War II, and was used as a basis for the US war movie The Heroes of Telemark.

As an initiation of their uprising, Slovakian rebels entered Banská Bystrica on the morning of August 30 1944, the second day of the rebellion, and made it their headquarters. By September 10 the insurgents gained control of large areas of central and eastern Slovakia. That included two captured airfields, and as a result of the two-week-old insurgency, the Soviet Air Force were able to begin flying in equipment to Slovakian and Soviet partisans.

There were also many brave men and women who resisted the Japanese occupation of their Homeland and Western colonies during World War II. You can look them up in the list of names of organization below.

Resistance movements during World War II

- British resistance movement

- Auxiliary Units (planned British resistance movement against German invaders)

- Albanian resistance movement

- Austrian resistance movement, e.g. O5

- Belarusian resistance movement

- Belgian Resistance

- Bulgarian resistance movement

- Burmese resistance movement (AFPFL – Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League)

- Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian anti-Soviet resistance movements ("Forest Brothers")

- Czech resistance movement

- Danish resistance movement

- Dutch resistance movement

- Estonian resistance movement

- French resistance movement

- German anti-Nazi resistance movement

- The White Rose

- The Red Orchestra

- The Edelweiss Pirates

- The Stijkel Group, a Dutch resistance movement, which mainly operated around the S-Gravenhage area.

- Werwolf, the Nazi resistance against the Allied occupation

- Greek Resistance

- List of Greek Resistance organizations

- Cretan resistance

- National Liberation Front (EAM) and the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS), EAM's guerrilla forces

- National Republican Greek League (EDES)

- National and Social Liberation (EKKA)

- Chinese resistance movements

- Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army

- Anti-Japanese Army For The Salvation Of The Country

- Chinese People's National Salvation Army

- Heilungkiang National Salvation Army

- Jilin Self-Defence Army

- Northeast Anti-Japanese National Salvation Army

- Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army

- Northeast People's Anti-Japanese Volunteer Army

- Northeastern Loyal and Brave Army

- Northeastern People's Revolutionary Army

- Northeastern Volunteer Righteous & Brave Fighters

- Hong Kong resistance movements

- Gangjiu dadui (Hong Kong-Kowloon big army)

- Dongjiang Guerrillas (East River Guerrillas, Southern China and Hong Kong organisation)

- Italian resistance movement

- Italian resistance against Allies in East-Africa

- Jewish resistance movement

- Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ZOB, the Jewish Fighting Organisation)

- Zydowski Zwiazek Walki (ZZW, the Jewish Fighting Union)

- Korea resistance movement

- Latvian resistance movement

- Lithuanian resistance during World War II

- Luxembourgs resistance during World War II

- Malayan resistance movemment

- Norwegian resistance movement

- Milorg

- XU

- Norwegian Independent Company 1 (Kompani Linge)

- Nortraship

- Osvald Group

- Philippine resistance movement

- Polish resistance movement

- Armia Krajowa (the Home Army—main stream: Authoritarian/Western Democracy)

- Narodowe Siły Zbrojne (National Armed Forces—Fascists)

- Bataliony Chłopskie (Farmers' Battalions—main stream, apolitical, stress on private property)

- Armia Ludowa (the Peoples' Army—Soviet Proxies)

- Gwardia Ludowa (the Peoples' Guard—Soviet Proxies)

- Gwardia Ludowa WRN (The Peoples' Guard Freedom Euqailty Independence—main stream; Polish Socialist Party's underground; progressive, anti—nazi and anti—Soviet; believed firmly in private property; believed in Marx's critique of the Capitalist system, but rejected his solution)

- Leśni (Forest People—various)

- Polish Secret State

- Romanian resistance movement (anti-communist)

- Singaporean resistance movement

- Slovak resistance movement

- Soviet resistance movement

- Thai resistance movement

- Ukrainian Insurgent Army (anti-German, anti-Soviet and anti-Polish resistance movement)

- Viet Minh (Vietnamese resistance organization that had fought Vichy France and the Japanese)

- Yugoslavia

- Chetniks (Serbian nationalist and royalist resistance, started collaborating with the Axis occupation to an ever-increasing degree, eventually functioning by the end of the war as an Axis-supported militia)

- Yugoslav Partisans ("Partisans", pro-communist resistance)

Notable individuals

Documentaries

- Confusion was their business (from the BBC series Secrets of World War II is a documentary about the SOE (Special Operations Executive) and its operations

- The Real Heroes of the Telemark is a book and documentary by survival expert Ray Mears about the Norwegian sabotage of the German nuclear program (Norwegian heavy water sabotage)

- Making Choices: The Dutch Resistance during World War II (2005) This award-winning, hour-long documentary tells the stories of four participants in the Dutch Resistance and the miracles that saved them from certain death at the hands of the Nazis.

Dramatisations

- 'Allo 'Allo! (1982-1992) a situation comedy about the French resistance movement (a parody of Secret Army)

- L’Armée des ombres (1969) internal and external battles of the French resistance. Directed by Jean-Pierre Melville

- Battle of Neretva (film) (1969) is a movie depicting events that took place during the Fourth anti-Partisan Offensive (Fall Weiss), also known as The Battle for the Wounded

- Boško Buha (1978) tells the tale of a boy who conned his way into partisan ranks at age of 15 and became legendary for his talent of destroying enemy bunkers

- Charlotte Gray (2001) – thought to be based on Nancy Wake

- Come and See (1985) is a Soviet made film about partisans in Belarus, as well as war crimes committed by the war's various factions.

- Defiance (2008) tells the story of the Bielski partisans, a group of Jewish resistance fighters operating in Belorussia.

- Flame & Citron (2008) is a movie based on two Danish resistance fighters who were in the Holger Danske (resistance group).

- A Generation (1955) (Polish) two young men involved in resistance by GL

- The Heroes of Telemark (1965) is very loosely based on the Norwegian sabotage of the German nuclear program (the later Real Heroes of Telemark is more accurate)

- Het Meisje met het Rode Haar (1982) (Dutch) is about Dutch resistance fighter Hannie Schaft

- Kanał (1956) (Polish) first film ever to depict Warsaw Uprising

- The Longest Day (1962) features scenes of the resistance operations during Operation Overlord

- Massacre in Rome (1973) is based on a true story about Nazi retaliation after a resistance attack in Rome

- My Opposition: the Diaries of Friedrich Kellner (2007) is a Canadian film about Justice Inspector Friedrich Kellner of Laubach who challenged the Nazis before and during the war

- Secret Army (1977) a television series about the Belgian resistance movement, based on real events

- Soldaat van Oranje (1977) (Dutch) is about some Dutch students who enter the resistance in cooperation with England

- Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage (2005) is about the last days in the life of Sophie Scholl

- Stärker als die Nacht (1954) (East German) follows the story of a group of German Communist resistance fighters

- Sutjeska (1973) is a movie based on the events that took place during the Fifth anti-Partisan Offensive (Fall Schwartz)

See also

- Anti-partisan operations in World War II

- Collaborationism (the opposite of resistance)

- Collaboration during World War II

- American O.S.S. – Office of Strategic Services

- British S.O.E. – The Special Operations Executive

- British S.I.S. – The Secret Intelligence Service

- British S.A.S. – The Special Air Service

- Anti-fascism

- Covert cell

- Ghetto uprising

- Quotations about resistance

- List of revolutions and rebellions

References

- ^ Anna M

- ^ http://www.vojska.net/eng/world-war-2/yugoslavia/

- ^ *Marek Szymanski: Oddzial majora Hubala, Warszawa 1999, ISBN 83-912237-0-1

- ^ *Aleksandra Ziółkowska Boehm: A Polish Partisan's Story (to be published by Military History Press)

- ^ Jozef Garlinski, Fighting Auschwitz: the Resistance Movement in the Concentration Camp, Fawcett, 1975, ISBN 0-449-22599-2, reprinted by Time Life Education, 1993. ISBN 0-8094-8925-2

- ^ Hershel Edelheit, History of the Holocaust: A Handbook and Dictionary, Westview Press, 1994, ISBN 0813322405,Google Print, p.413

- ^ Adam Cyra, Ochotnik do Auschwitz - Witold Pilecki 1901-1948 [Volunteer for Auschwitz], Oświęcim 2000. ISBN 83-912000-3-5

- ^ Halina Auderska, Zygmunt Ziółek, Akcja N. Wspomnienia 1939-1945 (Action N. Memoirs 1939-1945), Wydawnictwo Czytelnik, Warszawa, 1972 Template:Pl icon

- ^ Norman Davies, Europe: A History, Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN

- ^ Christopher M. Woodhouse, "The struggle for Greece, 1941-1949", Hart-Davis Mc-Gibbon, 1977, Google print, p. 37

- ^ Richard Clogg, "A Short History of Modern Greece", Cambridge University Press, 1979 Google print, pp.142-143

- ^ Procopis Papastratis, "British policy towards Greece during the Second World War, 1941-1944", Cambridge University Press, 1984 Google print, p.129

- ^ Joseph Poprzeczny, Odilo Globocnik, Hitler's Man in the East, McFarland, 2004, ISBN 0786416254

- ^ Operation WEISS - The Battle of Neretva

- ^ Battles & Campaigns during World War 2 in Yugoslavia

- ^ Meksyk II

- ^ Ordway, Frederick I., III. The Rocket Team. Apogee Books Space Series 36 (pp. 158, 173)

- ^ Piotr Stachniewicz, "AKCJA "KUTSCHERA", Książka i Wiedza, Warszawa 1982,

- ^ Joachim Lilla (Bearb.): Die Stellvertretenden Gauleiter und die Vertretung der Gauleiter der NSDAP im „Dritten Reich“, Koblenz 2003, S. 52-3 (Materialien aus dem Bundesarchiv, Heft 13)ISBN 3-86509-020-6

- ^ pp. 343-376, Eyre

- ^ Martin Gilbert, Second World War A Complete History, Holt Paperbacks, 2004, ISBN 0805076239, Google Print, p.542

External links

- European Resistance Archive

- Interviews from the Underground Eyewitness accounts of Russia's Jewish resistance during World War II; website & documentary film.