Antipsychotic: Difference between revisions

SandyGeorgia (talk | contribs) →Other: fix TS link |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2012}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2012}} |

||

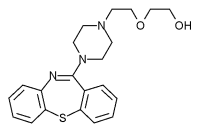

[[File:Zyprexa.PNG|thumb|right|[[Olanzapine]] (Zyprexa), an example of a second-generation antipsychotic]] |

[[File:Zyprexa.PNG|thumb|right|[[Olanzapine]] (Zyprexa), an example of a second-generation antipsychotic]] |

||

An '''antipsychotic''' (also known as '''neuroleptic '''even though not all antipsychotics have neuroleptic effect<ref>http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/neuroleptic</ref>) is a [[psychiatric medication]] primarily used to manage [[psychosis]] (including [[delusion]]s, [[hallucination]]s, or [[disordered thought]]), particularly in [[schizophrenia]] and [[bipolar disorder]], and is increasingly being used in the management of non-psychotic disorders ([[Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System|ATC]] code N05A). The word '''neuroleptic''' originates from Greek neuron + lepsis (seizure, fit).<ref>{{cite book|title=Moby's Medical Dictionary|publisher=Elsevier}}</ref> |

An '''antipsychotic''' (also known as '''neuroleptic '''even though not all antipsychotics have neuroleptic effect<ref>http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/neuroleptic{{full}}</ref>) is a [[psychiatric medication]] primarily used to manage [[psychosis]] (including [[delusion]]s, [[hallucination]]s, or [[disordered thought]]), particularly in [[schizophrenia]] and [[bipolar disorder]], and is increasingly being used in the management of non-psychotic disorders ([[Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System|ATC]] code N05A). The word '''neuroleptic''' originates from Greek neuron + lepsis (seizure, fit).<ref>{{cite book|title=Moby's Medical Dictionary|publisher=Elsevier}}</ref> |

||

A first generation of antipsychotics, known as [[typical antipsychotics]], was discovered in the 1950s. Most of the drugs in the second generation, known as [[atypical antipsychotics]], have been developed more recently, although the first atypical antipsychotic, [[clozapine]], was discovered in the 1950s and introduced clinically in the 1970s. Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's [[dopamine pathway]]s, but atypicals tend to act on [[serotonin]] as well. |

A first generation of antipsychotics, known as [[typical antipsychotics]], was discovered in the 1950s. Most of the drugs in the second generation, known as [[atypical antipsychotics]], have been developed more recently, although the first atypical antipsychotic, [[clozapine]], was discovered in the 1950s and introduced clinically in the 1970s. Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's [[dopamine pathway]]s, but atypicals tend to act on [[serotonin]] as well. |

||

A number of [[adverse effect|adverse]] effects have been observed, including [[extrapyramidal symptoms|extrapyramidal]] effects on [[motor control]] – including [[akathisia]] (constant discomfort causing restlessness), [[tremor]], and [[dystonia|abnormal muscle contractions]], an involuntary movement disorder known as [[tardive dyskinesia]], and elevations in [[prolactin]] (resulting in [[gynecomastia|breast enlargement]] in men, [[galactorrhea|breast milk discharge]], or sexual dysfunction).<ref name="Stahl">{{cite book|author= |

A number of [[adverse effect|adverse]] effects have been observed, including [[extrapyramidal symptoms|extrapyramidal]] effects on [[motor control]] – including [[akathisia]] (constant discomfort causing restlessness), [[tremor]], and [[dystonia|abnormal muscle contractions]], an involuntary movement disorder known as [[tardive dyskinesia]], and elevations in [[prolactin]] (resulting in [[gynecomastia|breast enlargement]] in men, [[galactorrhea|breast milk discharge]], or sexual dysfunction).<ref name="Stahl">{{cite book |author=Stahl, S. M. |title=Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2008}}{{pn}}</ref> Some atypical antipsychotics have been associated with [[metabolic syndrome]] and, in the case of [[clozapine]], lowered [[white blood cell]] counts.<ref name="Stahl"/> |

||

In some instances a return of psychosis can occur, requiring increasing the dosage, due to cells producing more neurochemicals to compensate for the drugs ([[Tardive Psychosis|tardive psychosis]]), and there is a potential for permanent [[chemical dependence]] leading to psychosis worse than before treatment began, if the drug dosage is ever lowered or stopped ([[tardive dysphrenia]]).<ref> |

In some instances a return of psychosis can occur, requiring increasing the dosage, due to cells producing more neurochemicals to compensate for the drugs ([[Tardive Psychosis|tardive psychosis]]), and there is a potential for permanent [[chemical dependence]] leading to psychosis worse than before treatment began, if the drug dosage is ever lowered or stopped ([[tardive dysphrenia]]).<ref>{{cite journal |author=Peluso MJ, Lewis SW, Barnes TR, Jones PB |title=Extrapyramidal motor side-effects of first- and second-generation antipsychotic drugs |journal=Br J Psychiatry |volume=200 |issue=5 |pages=387–92 |year=2012 |month=May |pmid=22442101 |doi=10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101485}}</ref> Most side-effects disappear rapidly once the medication is discontinued or reduced, but others, particularly tardive dyskinesia, may be irreversible. |

||

Temporary withdrawal symptoms including insomnia, agitation, psychosis, and motor disorders may occur during dosage reduction of antipsychotics, and can be mistaken for a return of the underlying condition.<ref name="Dilsaver-1988"/><ref name="Moncrieff-2006"/> |

Temporary withdrawal symptoms including insomnia, agitation, psychosis, and motor disorders may occur during dosage reduction of antipsychotics, and can be mistaken for a return of the underlying condition.<ref name="Dilsaver-1988"/><ref name="Moncrieff-2006"/> |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Common conditions with which antipsychotics might be used include [[schizophrenia]], [[bipolar disorder]] and [[delusional disorder]]. Antipsychotics might also be used to counter psychosis associated with a wide range of other diagnoses, such as [[psychotic depression]]. However, not all symptoms require treatment with medication, and hallucinations and delusions should only be treated if they cause distress or dysfunction.<ref name="alcouncil.com">[http://www.alcouncil.com/docs/2008Conference/handouts/powers/Choosing%20the%20right%20neuroleptic%20for%20a%20patient.pdf Choosing the right neuroleptic for a Patient (2008)]. (PDF) .</ref> |

Common conditions with which antipsychotics might be used include [[schizophrenia]], [[bipolar disorder]] and [[delusional disorder]]. Antipsychotics might also be used to counter psychosis associated with a wide range of other diagnoses, such as [[psychotic depression]]. However, not all symptoms require treatment with medication, and hallucinations and delusions should only be treated if they cause distress or dysfunction.<ref name="alcouncil.com">[http://www.alcouncil.com/docs/2008Conference/handouts/powers/Choosing%20the%20right%20neuroleptic%20for%20a%20patient.pdf Choosing the right neuroleptic for a Patient (2008)]. (PDF) .</ref> |

||

A survey of children with [[pervasive developmental disorder]] found that 16.5% were taking an antipsychotic drug, most commonly to alleviate mood and behavioral disturbances characterized by irritability, aggression, and agitation. Recently, risperidone was approved by the US FDA for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism.<ref> |

A survey of children with [[pervasive developmental disorder]] found that 16.5% were taking an antipsychotic drug, most commonly to alleviate mood and behavioral disturbances characterized by irritability, aggression, and agitation. Recently, risperidone was approved by the US FDA for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ |title=Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism |journal=J. Clin. Invest. |volume=118 |issue=1 |pages=6–14 |year=2008 |month=January |pmid=18172517 |pmc=2171144 |doi=10.1172/JCI32483}}</ref> |

||

===Schizophrenia=== |

===Schizophrenia=== |

||

In people with schizophrenia less than half (41%) showed any therapeutic response to an atypical antipsychotic, compared to 24% on placebo, there is a decline in treatment response over time, and potentially a biases in the literature in favor of these medication.<ref name="pmid18180760">{{cite journal| |

In people with schizophrenia less than half (41%) showed any therapeutic response to an atypical antipsychotic, compared to 24% on placebo, there is a decline in treatment response over time, and potentially a biases in the literature in favor of these medication.<ref name="pmid18180760">{{cite journal |author=Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM |title=How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials |journal=Mol. Psychiatry |volume=14 |issue=4 |pages=429–47 |year=2009 |month=April |pmid=18180760 |doi=10.1038/sj.mp.4002136}}</ref> [[Risperidone]] (an atypical antipsychotic), shows only marginal benefit compared with placebo and that, despite its widespread use, evidence remains limited, poorly reported and probably biased in favor of risperidone due to pharmaceutical company funding of trials.<ref name="pmid20091611">{{cite journal |author=Rattehalli RD, Jayaram MB, Smith M |title=Risperidone versus placebo for schizophrenia |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume= |issue=1 |pages=CD006918 |year=2010 |pmid=20091611 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006918}}</ref> |

||

Some doubts have been raised about the long-term effectiveness of antipsychotics for schizophrenia, in part because two large international [[World Health Organization]] studies found individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia tend to have better long-term outcomes in developing countries (where there is lower availability and use of antipsychotics and mental health problems are treated with more informal, community-led methods only) than in developed countries.<ref>{{ |

Some doubts have been raised about the long-term effectiveness of antipsychotics for schizophrenia, in part because two large international [[World Health Organization]] studies found individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia tend to have better long-term outcomes in developing countries (where there is lower availability and use of antipsychotics and mental health problems are treated with more informal, community-led methods only) than in developed countries.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, ''et al.'' |title=Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study |journal=Psychol Med Monogr Suppl |volume=20 |issue= |pages=1–97 |year=1992 |pmid=1565705 |doi=10.1017/S0264180100000904}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Hopper K, Wanderling J |title=Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative followup project. International Study of Schizophrenia |journal=Schizophr Bull |volume=26 |issue=4 |pages=835–46 |year=2000 |pmid=11087016 |doi=10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033498}}</ref> |

||

Some argue that the evidence for antipsychotics from discontinuation-relapse studies may be flawed, because they do not take into account that antipsychotics may sensitize the brain and provoke psychosis if discontinued, which may then be wrongly interpreted as a relapse of the original condition.<ref>{{ |

Some argue that the evidence for antipsychotics from discontinuation-relapse studies may be flawed, because they do not take into account that antipsychotics may sensitize the brain and provoke psychosis if discontinued, which may then be wrongly interpreted as a relapse of the original condition.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Moncrieff J |title=Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse |journal=Acta Psychiatr Scand |volume=114 |issue=1 |pages=3–13 |year=2006 |month=July |pmid=16774655 |doi=10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x}}</ref> Evidence from comparison studies indicates that at least some individuals with schizophrenia recover from psychosis without taking antipsychotics, and may do better in the long term than those that do take antipsychotics.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Harrow M, Jobe TH |title=Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: a 15-year multifollow-up study |journal=J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. |volume=195 |issue=5 |pages=406–14 |year=2007 |month=May |pmid=17502806 |doi=10.1097/01.nmd.0000253783.32338.6e}}</ref> Some argue that, overall, the evidence suggests that antipsychotics only help if they are used selectively and are gradually withdrawn as soon as possible<ref>{{cite journal |author=Whitaker R |title=The case against antipsychotic drugs: a 50-year record of doing more harm than good |journal=Med. Hypotheses |volume=62 |issue=1 |pages=5–13 |year=2004 |pmid=14728997 |doi=10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00293-7}}</ref> and have referred to the "Myth of the antipsychotic".<ref name="guard 1">{{cite web |title=Myth of the antipsychotic |url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2008/mar/02/mythoftheantipsychotic |work=The Guardian |publisher=Guardian News and Media Limited |accessdate=27 July 2012 |first=Adam |last=James |date=2 March 2008}}</ref> |

||

A review of the methods used in trials of antipsychotics, despite stating that the overall quality is "rather good," reported issues with the selection of participants (including that in schizophrenia trials up to 90% of people who are generally suitable do not meet the elaborate inclusion and exclusion criteria, and that negative symptoms have not been properly assessed despite companies marketing the newer antipsychotics for these); issues with the design of trials (including pharmaceutical company funding of most of them, and inadequate [[blind experiment|experimental "blinding"]] so that trial participants could sometimes tell whether they were on placebo or not); and issues with the assessment of outcomes (including the use of a minimal reduction in scores to show "response," lack of assessment of quality of life or recovery, a high rate of discontinuation, selective highlighting of favorable results in the abstracts of publications, and poor reporting of side-effects).<ref> |

A review of the methods used in trials of antipsychotics, despite stating that the overall quality is "rather good," reported issues with the selection of participants (including that in schizophrenia trials up to 90% of people who are generally suitable do not meet the elaborate inclusion and exclusion criteria, and that negative symptoms have not been properly assessed despite companies marketing the newer antipsychotics for these); issues with the design of trials (including pharmaceutical company funding of most of them, and inadequate [[blind experiment|experimental "blinding"]] so that trial participants could sometimes tell whether they were on placebo or not); and issues with the assessment of outcomes (including the use of a minimal reduction in scores to show "response," lack of assessment of quality of life or recovery, a high rate of discontinuation, selective highlighting of favorable results in the abstracts of publications, and poor reporting of side-effects).<ref>{{cite journal |author=Leucht S, Heres S, Hamann J, Kane JM |title=Methodological issues in current antipsychotic drug trials |journal=Schizophr Bull |volume=34 |issue=2 |pages=275–85 |year=2008 |month=March |pmid=18234700 |pmc=2632403 |doi=10.1093/schbul/sbm159}}</ref> |

||

While [[Flupenthixol]] an injectable form of antipsychotic which is given every few weeks is extensively used there is little evidence to support this use.<ref>{{cite journal| |

While [[Flupenthixol]] an injectable form of antipsychotic which is given every few weeks is extensively used there is little evidence to support this use.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Shen X, Xia J, Adams CE |title=Flupenthixol versus placebo for schizophrenia |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume=11 |issue= |pages=CD009777 |year=2012 |pmid=23152280 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD009777.pub2}}</ref> There is little long term data on the benefits of antipsychotics (beyond two to three years).<ref name=Harrow2013>{{cite journal |author=Harrow M, Jobe TH |title=Does Long-Term Treatment of Schizophrenia With Antipsychotic Medications Facilitate Recovery? |journal=Schizophr Bull |volume= |issue= |pages= |year=2013 |month=March |pmid=23512950 |doi=10.1093/schbul/sbt034}}</ref> It is recommended that if a person is without symptoms for a year stopping the use of antipsychotics be considered.<ref name=Harrow2013/> |

||

===Bipolar=== |

===Bipolar=== |

||

A Cochrane review in 2009, of bipolar disorder, found the efficacy and risk/benefit ratio better for the traditional mood stabilizer [[Lithium (medication)|lithium]] than for the antipsychotic [[olanzapine]] as a first line maintenance treatment.<ref>{{ |

A Cochrane review in 2009, of bipolar disorder, found the efficacy and risk/benefit ratio better for the traditional mood stabilizer [[Lithium (medication)|lithium]] than for the antipsychotic [[olanzapine]] as a first line maintenance treatment.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cipriani A, Rendell JM, Geddes J |title=Olanzapine in long-term treatment for bipolar disorder |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume= |issue=1 |pages=CD004367 |year=2009 |pmid=19160237 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD004367.pub2}}</ref> |

||

The [[American Psychiatric Association]] and the UK [[National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence]] recommend antipsychotics for managing acute psychotic episodes in schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and as a longer-term maintenance treatment for reducing the likelihood of further episodes.<ref name="pmid15000267">{{cite journal|title=Practice |

The [[American Psychiatric Association]] and the UK [[National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence]] recommend antipsychotics for managing acute psychotic episodes in schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and as a longer-term maintenance treatment for reducing the likelihood of further episodes.<ref name="pmid15000267">{{cite journal |author=Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, ''et al.'' |title=Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition |journal=Am J Psychiatry |volume=161 |issue=2 Suppl |pages=1–56 |year=2004 |month=February |pmid=15000267}}</ref><ref>The Royal College of Psychiatrists & The British Psychological Society (2003). [http://www.nice.org.uk/download.aspx?o=289559 ''Schizophrenia. Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care''] (PDF). London: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society.{{dead link}}{{pn}}</ref> They state that response to any given antipsychotic can be variable so that trials may be necessary, and that lower doses are to be preferred where possible. A number of studies have looked at levels of "compliance" or "adherence" with antipsychotic regimes and found that discontinuation (stopping taking them) by patients is associated with higher rates of relapse, including hospitalization. |

||

===Dementia=== |

===Dementia=== |

||

A 2006 [[Cochrane Collaboration]] review of controlled trials of antipsychotics in old age [[dementia]] reported that one or two of the drugs showed a modest benefit compared to placebo in managing aggression or psychosis, but that this was combined with a significant increase in serious adverse events. They concluded that this confirms that antipsychotics should not be used routinely to treat dementia patients with aggression or psychosis, but may be an option in the minority of cases where there is severe distress or risk of physical harm to others.<ref>{{cite |

A 2006 [[Cochrane Collaboration]] review of controlled trials of antipsychotics in old age [[dementia]] reported that one or two of the drugs showed a modest benefit compared to placebo in managing aggression or psychosis, but that this was combined with a significant increase in serious adverse events. They concluded that this confirms that antipsychotics should not be used routinely to treat dementia patients with aggression or psychosis, but may be an option in the minority of cases where there is severe distress or risk of physical harm to others.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ballard C, Waite J |title=The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume= |issue=1 |pages=CD003476 |year=2006 |pmid=16437455 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003476.pub2}}</ref> |

||

===Other=== |

===Other=== |

||

Besides the above uses antipsychotics may be used for depression, OCD, PTSD, [[personality disorders]], [[Tourette syndrome]], autism and agitation in those with dementia.<ref name=Rand2012/> Evidence however does not support the use of atypical antipsychotics in [[eating disorders]] or personality disorder.<ref name="Off-Label Use">{{cite |

Besides the above uses antipsychotics may be used for depression, OCD, PTSD, [[personality disorders]], [[Tourette syndrome]], autism and agitation in those with dementia.<ref name=Rand2012/> Evidence however does not support the use of atypical antipsychotics in [[eating disorders]] or personality disorder.<ref name="Off-Label Use">{{cite book |first1=Margaret |last1=Maglione |first2=Alicia Ruelaz |last2=Maher |first3=Jianhui |last3=Hu |first4=Zhen |last4=Wang |first5=Roberta |last5=Shanman |first6=Paul G |last6Shekelle first7=Beth |last7=Roth first8=Lara |last8=Hilton first9=Marika J |last9=Suttorp |year=2011 |title=Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update |series=Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 43 |location=Rockville |publisher=Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66081/ |pmid=22132426}}{{pn}}</ref> [[Risperidone]] may be useful for [[obsessive compulsive disorder]].<ref name=Rand2012>{{cite journal |author=Maher AR, Theodore G |title=Summary of the comparative effectiveness review on off-label use of atypical antipsychotics |journal=J Manag Care Pharm |volume=18 |issue=5 Suppl B |pages=S1–20 |year=2012 |month=June |pmid=22784311}}</ref> The use of low doses of antipsychotics for [[insomnia]], while common, is not recommended as there is little evidence of benefit and concerns regarding adverse effects.<ref name="Off-Label Use"/><ref>{{cite journal |author=Coe HV, Hong IS |title=Safety of low doses of quetiapine when used for insomnia |journal=Ann Pharmacother |volume=46 |issue=5 |pages=718–22 |year=2012 |month=May |pmid=22510671 |doi=10.1345/aph.1Q697}}</ref> Low dose antipsychotics may also be used in treatment of impulse-behavioral and cognitive-perceptual symptoms of [[borderline personality disorder]].<ref>{{cite book|last=American Psychiatric Association and American Psychiatric Association. Work Group on Borderline Personality Disorder|title=Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=xvQ2QKok3-oC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false|accessdate=June 5, 2013|year=2001|publisher=American Psychiatric Pub|page=4|isbn=0890423199}}</ref> |

||

In children they may be used in those with [[disruptive behavior disorder]]s, [[mood disorder]]s and [[pervasive developmental disorder]]s or [[mental retardation]].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Zuddas|first=A|coauthors=Zanni, R; Usala, T|title=Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) for non-psychotic disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the randomized controlled studies.|journal=European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology|date=2011 Aug|volume=21|issue=8|pages=600–20|pmid=21550212}}</ref> Antipsychotics are only weakly recommended for Tourette syndrome as well they are effective side effects are common.<ref>{{cite journal| |

In children they may be used in those with [[disruptive behavior disorder]]s, [[mood disorder]]s and [[pervasive developmental disorder]]s or [[mental retardation]].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Zuddas|first=A|coauthors=Zanni, R; Usala, T|title=Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) for non-psychotic disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the randomized controlled studies.|journal=European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology|date=2011 Aug|volume=21|issue=8|pages=600–20|pmid=21550212}}</ref> Antipsychotics are only weakly recommended for Tourette syndrome as well they are effective side effects are common.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Pringsheim T, Doja A, Gorman D, ''et al.'' |title=Canadian guidelines for the evidence-based treatment of tic disorders: pharmacotherapy |journal=Can J Psychiatry |volume=57 |issue=3 |pages=133–43 |year=2012 |month=March |pmid=22397999}}</ref> The situation is similar in [[autism spectrum disorder]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=McPheeters ML, Warren Z, Sathe N, ''et al.'' |title=A systematic review of medical treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders |journal=Pediatrics |volume=127 |issue=5 |pages=e1312–21 |year=2011 |month=May |pmid=21464191 |doi=10.1542/peds.2011-0427}}</ref> |

||

Much of the evidence for the off-label use of antipsychotics (for example, for depression, dementia, OCD, PTSD, Personality Disorders, Tourette's) was of insufficient scientific quality to support such use, especially as there was strong evidence of increased risks of stroke, tremors, significant weight gain, sedation, and gastrointestinal problems.<ref>[http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/pr2007/antipsypr. |

Much of the evidence for the off-label use of antipsychotics (for example, for depression, dementia, OCD, PTSD, Personality Disorders, Tourette's) was of insufficient scientific quality to support such use, especially as there was strong evidence of increased risks of stroke, tremors, significant weight gain, sedation, and gastrointestinal problems.<ref>[http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/pr2007/antipsypr.htm Evidence Lacking to Support Many Off-label Uses of Atypical Antipsychotics (2007)]{{dead link|date=March 2013}}. Ahrq.gov.</ref> A UK review of unlicensed usage in children and adolescents reported a similar mixture of findings and concerns.<ref>{{Cite journal |doi=10.1192/apt.bp.108.005652 |title=Prescribing antipsychotics for children and adolescents |year=2010 |last=James |first=Anthony C. |journal=Advances in Psychiatric Treatment |volume=16 |issue=1 |page=63–75}}</ref> |

||

Aggressive challenging behavior in adults with [[intellectual disability]] is often treated with antipsychotic drugs despite lack of an evidence base. A recent [[randomized controlled trial]], however, found no benefit over [[placebo]] and recommended that the use of antipsychotics in this way should no longer be regarded as an acceptable routine treatment.<ref>{{ |

Aggressive challenging behavior in adults with [[intellectual disability]] is often treated with antipsychotic drugs despite lack of an evidence base. A recent [[randomized controlled trial]], however, found no benefit over [[placebo]] and recommended that the use of antipsychotics in this way should no longer be regarded as an acceptable routine treatment.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Romeo R, Knapp M, Tyrer P, Crawford M, Oliver-Africano P |title=The treatment of challenging behaviour in intellectual disabilities: cost-effectiveness analysis |journal=J Intellect Disabil Res |volume=53 |issue=7 |pages=633–43 |year=2009 |month=July |pmid=19460067 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01180.x}}</ref> |

||

===Typicals versus atypicals=== |

===Typicals versus atypicals=== |

||

Revision as of 12:17, 28 July 2013

An antipsychotic (also known as neuroleptic even though not all antipsychotics have neuroleptic effect[1]) is a psychiatric medication primarily used to manage psychosis (including delusions, hallucinations, or disordered thought), particularly in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and is increasingly being used in the management of non-psychotic disorders (ATC code N05A). The word neuroleptic originates from Greek neuron + lepsis (seizure, fit).[2]

A first generation of antipsychotics, known as typical antipsychotics, was discovered in the 1950s. Most of the drugs in the second generation, known as atypical antipsychotics, have been developed more recently, although the first atypical antipsychotic, clozapine, was discovered in the 1950s and introduced clinically in the 1970s. Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's dopamine pathways, but atypicals tend to act on serotonin as well.

A number of adverse effects have been observed, including extrapyramidal effects on motor control – including akathisia (constant discomfort causing restlessness), tremor, and abnormal muscle contractions, an involuntary movement disorder known as tardive dyskinesia, and elevations in prolactin (resulting in breast enlargement in men, breast milk discharge, or sexual dysfunction).[3] Some atypical antipsychotics have been associated with metabolic syndrome and, in the case of clozapine, lowered white blood cell counts.[3]

In some instances a return of psychosis can occur, requiring increasing the dosage, due to cells producing more neurochemicals to compensate for the drugs (tardive psychosis), and there is a potential for permanent chemical dependence leading to psychosis worse than before treatment began, if the drug dosage is ever lowered or stopped (tardive dysphrenia).[4] Most side-effects disappear rapidly once the medication is discontinued or reduced, but others, particularly tardive dyskinesia, may be irreversible.

Temporary withdrawal symptoms including insomnia, agitation, psychosis, and motor disorders may occur during dosage reduction of antipsychotics, and can be mistaken for a return of the underlying condition.[5][6]

Medical uses

Common conditions with which antipsychotics might be used include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and delusional disorder. Antipsychotics might also be used to counter psychosis associated with a wide range of other diagnoses, such as psychotic depression. However, not all symptoms require treatment with medication, and hallucinations and delusions should only be treated if they cause distress or dysfunction.[7]

A survey of children with pervasive developmental disorder found that 16.5% were taking an antipsychotic drug, most commonly to alleviate mood and behavioral disturbances characterized by irritability, aggression, and agitation. Recently, risperidone was approved by the US FDA for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism.[8]

Schizophrenia

In people with schizophrenia less than half (41%) showed any therapeutic response to an atypical antipsychotic, compared to 24% on placebo, there is a decline in treatment response over time, and potentially a biases in the literature in favor of these medication.[9] Risperidone (an atypical antipsychotic), shows only marginal benefit compared with placebo and that, despite its widespread use, evidence remains limited, poorly reported and probably biased in favor of risperidone due to pharmaceutical company funding of trials.[10]

Some doubts have been raised about the long-term effectiveness of antipsychotics for schizophrenia, in part because two large international World Health Organization studies found individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia tend to have better long-term outcomes in developing countries (where there is lower availability and use of antipsychotics and mental health problems are treated with more informal, community-led methods only) than in developed countries.[11][12]

Some argue that the evidence for antipsychotics from discontinuation-relapse studies may be flawed, because they do not take into account that antipsychotics may sensitize the brain and provoke psychosis if discontinued, which may then be wrongly interpreted as a relapse of the original condition.[13] Evidence from comparison studies indicates that at least some individuals with schizophrenia recover from psychosis without taking antipsychotics, and may do better in the long term than those that do take antipsychotics.[14] Some argue that, overall, the evidence suggests that antipsychotics only help if they are used selectively and are gradually withdrawn as soon as possible[15] and have referred to the "Myth of the antipsychotic".[16]

A review of the methods used in trials of antipsychotics, despite stating that the overall quality is "rather good," reported issues with the selection of participants (including that in schizophrenia trials up to 90% of people who are generally suitable do not meet the elaborate inclusion and exclusion criteria, and that negative symptoms have not been properly assessed despite companies marketing the newer antipsychotics for these); issues with the design of trials (including pharmaceutical company funding of most of them, and inadequate experimental "blinding" so that trial participants could sometimes tell whether they were on placebo or not); and issues with the assessment of outcomes (including the use of a minimal reduction in scores to show "response," lack of assessment of quality of life or recovery, a high rate of discontinuation, selective highlighting of favorable results in the abstracts of publications, and poor reporting of side-effects).[17]

While Flupenthixol an injectable form of antipsychotic which is given every few weeks is extensively used there is little evidence to support this use.[18] There is little long term data on the benefits of antipsychotics (beyond two to three years).[19] It is recommended that if a person is without symptoms for a year stopping the use of antipsychotics be considered.[19]

Bipolar

A Cochrane review in 2009, of bipolar disorder, found the efficacy and risk/benefit ratio better for the traditional mood stabilizer lithium than for the antipsychotic olanzapine as a first line maintenance treatment.[20]

The American Psychiatric Association and the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend antipsychotics for managing acute psychotic episodes in schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and as a longer-term maintenance treatment for reducing the likelihood of further episodes.[21][22] They state that response to any given antipsychotic can be variable so that trials may be necessary, and that lower doses are to be preferred where possible. A number of studies have looked at levels of "compliance" or "adherence" with antipsychotic regimes and found that discontinuation (stopping taking them) by patients is associated with higher rates of relapse, including hospitalization.

Dementia

A 2006 Cochrane Collaboration review of controlled trials of antipsychotics in old age dementia reported that one or two of the drugs showed a modest benefit compared to placebo in managing aggression or psychosis, but that this was combined with a significant increase in serious adverse events. They concluded that this confirms that antipsychotics should not be used routinely to treat dementia patients with aggression or psychosis, but may be an option in the minority of cases where there is severe distress or risk of physical harm to others.[23]

Other

Besides the above uses antipsychotics may be used for depression, OCD, PTSD, personality disorders, Tourette syndrome, autism and agitation in those with dementia.[24] Evidence however does not support the use of atypical antipsychotics in eating disorders or personality disorder.[25] Risperidone may be useful for obsessive compulsive disorder.[24] The use of low doses of antipsychotics for insomnia, while common, is not recommended as there is little evidence of benefit and concerns regarding adverse effects.[25][26] Low dose antipsychotics may also be used in treatment of impulse-behavioral and cognitive-perceptual symptoms of borderline personality disorder.[27]

In children they may be used in those with disruptive behavior disorders, mood disorders and pervasive developmental disorders or mental retardation.[28] Antipsychotics are only weakly recommended for Tourette syndrome as well they are effective side effects are common.[29] The situation is similar in autism spectrum disorder.[30] Much of the evidence for the off-label use of antipsychotics (for example, for depression, dementia, OCD, PTSD, Personality Disorders, Tourette's) was of insufficient scientific quality to support such use, especially as there was strong evidence of increased risks of stroke, tremors, significant weight gain, sedation, and gastrointestinal problems.[31] A UK review of unlicensed usage in children and adolescents reported a similar mixture of findings and concerns.[32]

Aggressive challenging behavior in adults with intellectual disability is often treated with antipsychotic drugs despite lack of an evidence base. A recent randomized controlled trial, however, found no benefit over placebo and recommended that the use of antipsychotics in this way should no longer be regarded as an acceptable routine treatment.[33]

Typicals versus atypicals

While the atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics were marketed as offering greater efficacy in reducing psychotic symptoms while reducing side effects (and extrapyramidal symptoms in particular) than typical medications, the results showing these effects often lacked robustness, and the assumption was increasingly challenged even as atypical prescriptions were soaring.[34][35] One review concluded there were no differences[36] while another[37] found that atypicals were "only moderately more efficacious".[36] These conclusions were, however, questioned by another review, which found that clozapine, amisulpride, and olanzapine and risperidone were more effective[36][38] Clozapine has appeared to be more effective than other atypical antipsychotics,[36][39] although it has previously been banned due to its potentially lethal side effects. While controlled clinical trials of atypicals reported that extrapyramidal symptoms occurred in 5–15% of patients, a study of bipolar disorder in a real world clinical setting found a rate of 63%, questioning the generalizability of the trials.[40]

In 2005 the US government body NIMH published the results of a major independent (not funded by the pharmaceutical companies) multi-site, double-blind study (the CATIE project).[41] This study compared several atypical antipsychotics to an older typical antipsychotic, perphenazine, among 1493 persons with schizophrenia. The study found that only olanzapine outperformed perphenazine in discontinuation rate (the rate at which people stopped taking it due to its effects). The authors noted an apparent superior efficacy of olanzapine to the other drugs in terms of reduction in psychopathology and rate of hospitalizations, but olanzapine was associated with relatively severe metabolic effects such as a major weight gain problem (averaging 44 pounds (20 kg) over 18 months) and increases in glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides. The mean and maximal doses used for olanzapine were considerably higher than standard practice, and this has been postulated as a biasing factor that may explain olanzapine's superior efficacy over the other atypical antipsychotics studied, where doses were more in line with clinically relevant practices.[42] No other atypical studied (risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone) did better than the typical perphenazine on the measures used, nor did they produce fewer adverse effects than the typical antipsychotic perphenazine (a result supported by a meta-analysis[43] by Dr. Leucht published in Lancet), although more patients discontinued perphenazine owing to extrapyramidal effects compared to the atypical agents (8% vs. 2% to 4%, P=0.002).

A phase 2 part of this CATIE study roughly replicated these findings.[44] This phase consisted of a second randomization of the patients that discontinued taking medication in the first phase. Olanzapine was again the only medication to stand out in the outcome measures, although the results did not always reach statistical significance (which means they were not reliable findings) due in part to the decrease of power. The atypicals again did not produce fewer extrapyramidal effects than perphenazine. A subsequent phase was conducted[45] that allowed clinicians to offer clozapine which was more effective at reducing medication drop-outs than other neuroleptic agents. However, the potential for clozapine to cause toxic side effects, including agranulocytosis, limits its usefulness.

Compliance has not been shown to be different between the two types.[46]

Overall evaluations of the CATIE and other studies have led many researchers to question the first-line prescribing of atypicals over typicals, or even to question the distinction between the two classes.[47][48][49] In contrast, other researchers point to the significantly higher risk of tardive dyskinesia and EPS with the typicals and for this reason alone recommend first-line treatment with the atypicals, notwithstanding a greater propensity for metabolic adverse effects in the latter.[42][50] The UK government organization NICE recently revised its recommendation favoring atypicals, to advise that the choice should be an individual one based on the particular profiles of the individual drug and on the patient's preferences.

The re-evaluation of the evidence has not necessarily slowed the bias towards prescribing the atypicals.[51]

Adverse effects

Antipsychotics are associated with a range of side effects. It is well-recognized that many people stop taking them (around two-thirds even in controlled drug trials) due in part to adverse effects.[52] Potential adverse effects include extrapyramidal reactions (such as acute dystonias, akathisia, and Parkinsonian symptoms such as rigidity and tremor), tardive dyskinesia, tachycardia, hypotension, impotence, lethargy, seizures, intense dreams or nightmares, and hyperprolactinaemia.[53] Side effects from antipsychotics can in some cases be managed by the use of other medications. For example, anticholinergics are often used to alleviate the motor side effects of antipsychotics.[54]

Some studies have found decreased life expectancy associated with the use of antipsychotics, and argued that more studies are needed.[55][56] In Feb. 2011, a minor loss of brain tissue was reported in schizophrenics treated with antipsychotics.[57][58] Brain volume was negatively correlated with both duration of illness and antipsychotic dosage. No association was found with severity of illness or abuse of other substances. An accompanying editorial said: "The findings should not be construed as an indication for discontinuing the use of antipsychotic medications as a treatment for schizophrenia. But they do highlight the need to closely monitor the benefits and adverse effects of these medications in individual patients, to prescribe the minimal amount needed to achieve the therapeutic goal [and] to consider the addition of nonpharmacological approaches that may improve outcomes."[57][59] Continuous use of neuroleptics has been shown to decrease the total brain volume by 10% in macaque monkeys.[60]

In individuals without psychosis, doses of antipsychotics can produce the "negative symptoms" of schizophrenia such as amotivation.[61]

Following are details concerning some of the side effects of antipsychotics:

- Antipsychotics, particularly atypicals, appear to cause changes in insulin levels by blocking the muscarinic M3 receptor[62] (which is a key regulator of insulin secretion[63]) expressed on pancreatic beta cells and in regions of the brain that regulate glucose homeostasis. Altered insulin levels can lead to diabetes mellitus and fatal diabetic ketoacidosis, especially (in US studies) in African Americans.[64][65]

- Atypical antipsychotics may cause pancreatitis.[66]

- Some atypical antipsychotics (especially olanzapine and clozapine) are associated with body weight gain which has been hypothesized to be partially due to occupancy of the histamine receptor[67] and changes to neurochemical signalling in regions of the brain that regulate appetite.[68] A metabolic side effect associated with weight gain is diabetes.[69] Evidence suggests that females are more sensitive to the metabolic side-effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs than males.[70]

- Clozapine also has a risk of inducing agranulocytosis, a potentially dangerous reduction in the number of white blood cells in the body. Because of this risk, patients prescribed clozapine require regular blood tests to catch the condition early if it does occur and prevent harm to the patient.[71]

- One of the more serious potential side effects is tardive dyskinesia, in which the sufferer may show repetitive, involuntary, purposeless movements (that are permanent and have no cure) often of the lips, face, legs, or torso. Tardive dyskinesia tends to appear only with long-term use of antipsychotics, and is more likely to occur with the use of typical antipsychotics.[3]

- A potentially serious side effect of some antipsychotics is the tendency to lower an individual's seizure threshold. Chlorpromazine and clozapine, in particular, have a relatively high seizurogenic potential. Fluphenazine, haloperidol, pimozide and risperidone exhibit a relatively low risk. Caution should be exercised in individuals that have a history of seizurogenic conditions such as epilepsy, or brain damage.

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, in which the drugs appear to cause the temperature regulation centers to fail, resulting in a medical emergency, as the patient's temperature suddenly increases to dangerous levels.

- Dysphoria.

- Drug-induced parkinsonism due to dopamine D2 receptor blockade may mimic idiopathic parkinsonism. The typical antipsychotics are more prone to cause this than the atypical antipsychotics.

- Sexual dysfunction, which may rarely continue after withdrawal, similar to Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction.

- Akathisia, inability to sit still or remain motionless. Both typicals and atypicals can lead to akathisia.[72]

- Dystonia, a neurological movement disorder in which sustained muscle contractions cause twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal postures.

- Hyperprolactinaemia. The breasts may enlarge and discharge milk, in both men and women due to abnormally-high levels of prolactin in the blood. Prolactin secretion in the pituitary is normally suppressed by dopamine. Drugs that block the effects of dopamine at the pituitary or deplete dopamine stores in the brain may cause the pituitary to secrete prolactin.

- There is evidence that exposure may cause demyelinating disease in laboratory animals.[73]

- Antipsychotics increase the risk of early death in individuals with dementia.[74]

- Some antipsychotics may produce pharyngitis.[75]

Antipsychotic polypharmacy (prescribing two or more antipsychotics at the same time for an individual) is said to be a common practice but not necessarily evidence-based or recommended, and there have been initiatives to curtail it.[76] Similarly, the use of excessively high doses (often the result of polypharmacy) continues despite clinical guidelines and evidence indicating that it is usually no more effective but is usually more harmful.[77]

Withdrawal

Withdrawal symptoms from antipsychotics may emerge during dosage reduction and discontinuation. Withdrawal symptoms can include nausea, emesis, anorexia, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, diaphoresis, myalgia, paresthesia, anxiety, agitation, restlessness, and insomnia. The psychological withdrawal symptoms can include psychosis, and can be mistaken for a relapse of the underlying disorder. Conversely, the withdrawal syndrome may also be a trigger for relapse. Better management of the withdrawal syndrome may improve the ability of individuals to discontinue antipsychotics.[5][6]

Tardive dyskinesia may abate during withdrawal from the antispsychotic agent, or it may persist.[78] Withdrawal-related psychosis from antipsychotics is called "supersensitivity psychosis", and is attributed to increased number and sensitivity of brain dopamine receptors, due to blockade of dopaminergic receptors by the antipsychotics,[79] which often leads to exacerbated symptoms in the absence of neuroleptic medication.[80] Efficacy of antipsychotics may likewise be reduced over time, due to this development of drug tolerance.[6]

Withdrawal effects may also occur when switching a person from one antipsychotic to another, (presumably due to variations of potency and receptor activity). Such withdrawal effects can include cholinergic rebound, an activation syndrome, and motor syndromes including dyskinesias. These adverse effects are more likely during rapid changes between antipsychotic agents, so making a gradual change between antipsychotics minimises these withdrawal effects.[81] The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotic treatment to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[82] The process of cross-titration involves gradually increasing the dose of the new medication while gradually decreasing the dose of the old medication.[3]

Structural effects

Chronic treatment with antipsychotics may reduce amounts of brain tissue and potentially cause some of the symptoms believed to be due to schizophrenia [83] The effects may differ for typical versus atypical antipsychotics and may interact with different stages of disorders.[84] Such effects were not clearly tested for by pharmaceutical companies prior to obtaining approval for placing the drugs on the market.[85]

List of antipsychotics

Commonly used antipsychotic medications are listed below by drug group. Trade names appear in parentheses.

First-generation antipsychotics

Butyrophenones

- Haloperidol (Haldol, Serenace)

- Droperidol (Droleptan, Inapsine)

Phenothiazines

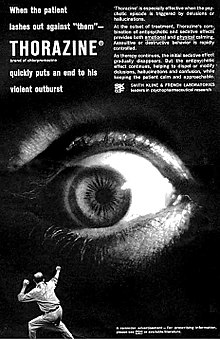

- Chlorpromazine (Thorazine, Largactil)

- Fluphenazine (Prolixin) – Available in decanoate (long-acting) form

- Perphenazine (Trilafon)

- Prochlorperazine (Compazine)

- Thioridazine (Mellaril)

- Trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

- Mesoridazine (Serentil)

- Periciazine

- Promazine

- Triflupromazine (Vesprin)

- Levomepromazine (Nozinan)

- Promethazine (Phenergan)

- Pimozide (Orap)

- Cyamemazine (Tercian)

Thioxanthenes

- Chlorprothixene (Cloxan, Taractan, Truxal)

- Clopenthixol (Sordinol)

- Flupenthixol (Depixol, Fluanxol)

- Thiothixene (Navane)

- Zuclopenthixol (Cisordinol, Clopixol, Acuphase)

Second-generation antipsychotics

- Clozapine (Clozaril) – Requires complete blood counts every one to four weeks due to the risk of agranulocytosis.

- Olanzapine (Zyprexa) – Used to treat psychotic disorders including schizophrenia, acute manic episodes, and maintenance of bipolar disorder

- Risperidone (Risperdal) – Divided dosing is recommended until initial titration is completed, at which time the drug can be administered once daily. Used off-label to treat Tourette syndrome and anxiety disorder.

- Quetiapine (Seroquel) – Used primarily to treat bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

- Ziprasidone (Geodon) – Approved in 2004[86] to treat bipolar disorder. Side-effects include a prolonged QT interval in the heart, which can be dangerous for patients with heart disease or those taking other drugs that prolong the QT interval.

- Amisulpride (Solian) – Selective dopamine antagonist. Higher doses (greater than 400 mg) act upon post-synaptic dopamine receptors resulting in a reduction in the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, such as psychosis. Lower doses, however, act upon dopamine autoreceptors, resulting in increased dopamine transmission, improving the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Lower doses of amisulpride have also been shown to have antidepressant and anxiolytic effects in non-schizophrenic patients, leading to its use in dysthymia and social phobias. Amisulpride has not been approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.

- Asenapine (Saphris) is a 5-HT2A- and D2-receptor antagonist developed for the treatment of schizophrenia and acute mania associated with bipolar disorder.

- Paliperidone (Invega) – Derivative of risperidone that was approved in 2006, it offers a controlled release once-daily dose, or a once-monthly depot injection.

- Iloperidone (Fanapt, Fanapta, and previously known as Zomaril) – Approved by the FDA in 2009, it is fairly well tolerated, although hypotension, dizziness, and somnolence were very common side effects.

- Zotepine (Nipolept, Losizopilon, Lodopin, Setous) – An atypical antipsychotic indicated for acute and chronic schizophrenia. It was approved in Japan circa 1982 and Germany in 1990.

- Sertindole (Serdolect, and Serlect in Mexico). Sertindole was developed by the Danish pharmaceutical company H. Lundbeck. Like the other atypical antipsychotics, it is believed to have antagonist activity at dopamine and serotonin receptors in the brain.

- Lurasidone (Latuda), recently approved by the FDA for schizophrenia and pending approval for bipolar disorder. Given once daily, it has shown mixed Phase III efficacy results but has a relatively well-tolerated side effect profile.

Third-generation antipsychotics

- Aripiprazole (Abilify) – Mechanism of action is thought to reduce susceptibility to metabolic symptoms seen in some other atypical antipsychotics.[87]

Mechanism of action

All antipsychotic drugs tend to block D2 receptors in the dopamine pathways of the brain. This means that dopamine released in these pathways has less effect. Excess release of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway has been linked to psychotic experiences. It has also been proven[citation needed] less dopamine released in the prefrontal cortex in the brain, and excess dopamine released from all other pathways, has also been linked to psychotic experiences, caused by abnormal dopaminergic function as a result of patients suffering from schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Various neuroleptics such as haloperidol and chlorpromazine suppress dopamine chemicals throughout its pathways, in order for dopamine receptors to function normally.

Typical antipsychotics are not particularly selective and also block dopamine receptors in the mesocortical pathway, tuberoinfundibular pathway, and the nigrostriatal pathway. Blocking D2 receptors in these other pathways is thought to produce some of the unwanted side effects that the typical antipsychotics can produce (see above). They were commonly classified on a spectrum of low potency to high potency, where potency referred to the ability of the drug to bind to dopamine receptors, and not to the effectiveness of the drug. High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol, in general, have doses of a few milligrams and cause less sleepiness and calming effects than low-potency antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine and thioridazine, which have dosages of several hundred milligrams. The latter have a greater degree of anticholinergic and antihistaminergic activity, which can counteract dopamine-related side effects.

Atypical antipsychotic drugs have a similar blocking effect on D2 receptors. Some also block or partially block serotonin receptors (particularly 5HT2A, C and 5HT1A receptors):ranging from risperidone, which acts overwhelmingly on serotonin receptors, to amisulpride, which has no serotonergic activity. The additional effects on serotonin receptors may be why some of them can benefit the "negative symptoms" of schizophrenia.[88]

History

The original antipsychotic drugs were happened upon largely by chance and then tested for their effectiveness. The first, chlorpromazine, was developed as a surgical anesthetic. It was first used on psychiatric patients because of its powerful calming effect; at the time it was regarded as a non-permanent "pharmacological lobotomy".[90] Lobotomy at the time was used to treat many behavioral disorders, including psychosis, although its effect was to markedly reduce behavior and mental functioning of all types. However, chlorpromazine proved to reduce the effects of psychosis in a more effective and specific manner than lobotomy, even though it was known to be capable of causing severe sedation. The underlying neurochemistry involved has since been studied in detail, and subsequent antipsychotic drugs have been discovered by an approach that incorporates this sort of information.

The discovery of chlorpromazine's psychoactive effects in 1952 led to greatly reduced use of restraint, seclusion, and sedation in the management of agitated patients,[90] and also led to further research that resulted in the development of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and the majority of other drugs now used in the management of psychiatric conditions. In 1952, Henri Laborit described chlorpromazine only as inducing indifference towards what was happening around them in nonpsychotic, nonmanic patients, and Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker described it as controlling manic or psychotic agitation. The former claimed to have discovered a treatment for agitation in anyone, and the latter team claimed to have discovered a treatment for psychotic illness.[91]

Until the 1970s there was considerable debate within psychiatry on the most appropriate term to use to describe the new drugs.[92] In the late 1950s the most widely used term was "neuroleptic", followed by "major tranquilizer" and then "ataraxic".[92] The first recorded use of the term tranquilizer dates from the early nineteenth century.[93] In 1953 Frederik F. Yonkman, a chemist at the Swiss based Ciba pharmaceutical company, first used the term tranquilizer to differentiate reserpine from the older sedatives.[94] The word neuroleptic was derived from the Greek: "νεῦρον"(neuron, originally meaning "sinew" but today referring to the nerves) and "λαμβάνω" (lambanō, meaning "take hold of"). Thus, the word means taking hold of one's nerves. This may refer to common side effects such as reduced activity in general, as well as lethargy and impaired motor control. Although these effects are unpleasant and in some cases harmful, they were at one time, along with akathisia, considered a reliable sign that the drug was working.[90] The term "ataraxy" was coined by the neurologist Howard Fabing and the classicist Alister Cameron to describe the observed effect of psychic indifference and detachment in patients treated with chlorpromazine.[95] This term derived from the Greek adjective "ἀτάρακτος" (ataraktos) which means "not disturbed, not excited, without confusion, steady, calm".[92] In the use of the terms "tranquilizer" and "ataractic", medical practitioners distinguished between the "major tranquilizers" or "major ataractics", which referred to drugs used to treat psychoses, and the "minor tranquilizers" or "minor ataractics", which referred to drugs used to treat neuroses.[92] While popular during the 1950s, these terms are infrequently used today. They are being abandoned in favor of "antipsychotic", which refers to the drug's desired effects.[92] Today, "minor tranquilizer" can refer to anxiolytic and/or hypnotic drugs such as the benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines which have some antipsychotic properties and are recommended for concurrent use with antipsychotics, and are useful for insomnia or drug-induced psychosis.[96] They are powerful (and potentially addictive) sedatives.

Antipsychotics are broadly divided into two groups, the typical or first-generation antipsychotics and the atypical or second-generation antipsychotics. The typical antipsychotics are classified according to their chemical structure while the atypical antipsychotics are classified according to their pharmacological properties. These include serotonin-dopamine antagonists (see dopamine antagonist and serotonin antagonist), multi-acting receptor-targeted antipsychotics (MARTA, those targeting several systems), and dopamine partial agonists, which are often categorized as atypicals.[36]

Antipsychotic drugs are now the top-selling class of pharmaceuticals in America, generating annual revenue of about $14.6 billion.[97]

Society and culture

Sales

Antipsychotics are among the biggest selling and most profitable of all drugs, generating $22 billion in global sales in 2008.[98] By 2003 in the US, an estimated 3.21 million patients received antipsychotics, worth an estimated $2.82 billion. Over 2/3 of prescriptions were for the newer more expensive atypicals, each costing on average $164 compared to $40 for the older types.[99] By 2008, sales in the US reached $14.6 billion, the biggest selling drugs in the US by therapeutic class.[100] The number of prescriptions for children and adolescents doubled to 4.4 million between 2003 and 2006, in part because of increases in diagnoses of bipolar disorder.[citation needed]

Formulations

Antipsychotics are sometimes administered as part of compulsory psychiatric treatment via inpatient (hospital) commitment or outpatient commitment. They may be administered orally or, in some cases, through long-acting (depot) injections administered in the dorsgluteal, ventrogluteal or deltoid muscle.

Controversy

According to The Guardian newspaper: "At the heart of years of dissent against psychiatry through the ages has been its use of drugs, particularly antipsychotics, to treat distress. Do such drugs actually target any "psychiatric condition"? Or are they chemical control—a socially-useful reduction of the paranoid, deluded, distressed, bizarre and odd into semi-vegetative zombies?"[16]

Use of this class of drugs has a history of criticism in residential care. As the drugs used can make patients calmer and more compliant, critics claim that the drugs can be overused. Outside doctors can feel under pressure from care home staff.[101] In an official review commissioned by UK government ministers it was reported that the needless use of anti-psychotic medication in dementia care was widespread and was linked to 1800 deaths per year.[102][103] In the US, the government has initiated legal action against the pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson for allegedly paying kickbacks to Omnicare to promote its antipsychotic Risperidone (Risperdal) in nursing homes.[104]

There is some controversy over maintenance therapy for schizophrenia.[6][105] A review of studies about maintenance therapy concluded that long-term antipsychotic treatment was superior to placebo in reducing relapse in individuals with schizophrenia, although some of the studies were small.[106] A review of major longitudinal studies in North America found that a moderate number of patients with schizophrenia were seen to recover over time from their symptoms, raising the possibility that some patients may not require maintenance medication.[105] It has also been argued that much of the research into long-term antipsychotic maintenance may be flawed due to failure to take into account the role of antipsychotic withdrawal effects on relapse rates.[6]

There has also been controversy about the role of pharmaceutical companies in marketing and promoting antipsychotics, including allegations of downplaying or covering up adverse effects, expanding the number of conditions or illegally promoting off-label usage; influencing drug trials (or their publication) to try to show that the expensive and profitable newer atypicals were superior to the older cheaper typicals that were out of patent. Following charges of illegal marketing, settlements by two large pharmaceutical companies in the US set records for the largest criminal fines ever imposed on corporations.[97] One case involved Eli Lilly and Company's antipsychotic Zyprexa, and the other involved Bextra. In the Bextra case, the government also charged Pfizer with illegally marketing another antipsychotic, Geodon.[97] In addition, Astrazeneca faces numerous personal-injury lawsuits from former users of Seroquel (quetiapine), amidst federal investigations of its marketing practices.[107] By expanding the conditions for which they were indicated, Astrazeneca's Seroquel and Eli Lilly's Zyprexa had become the biggest selling antipsychotics in 2008 with global sales of $5.5 billion and $5.4 billion respectively.[98]

Harvard medical professor Joseph Biederman conducted research on bipolar disorder in children that led to an increase in such diagnoses. A 2008 Senate investigation found that Biederman also received $1.6 million in speaking and consulting fees between 2000 and 2007 — some of them undisclosed to Harvard — from companies including makers of antipsychotic drugs prescribed for children with bipolar disorder. Johnson & Johnson gave more than $700,000 to a research center that was headed by Biederman from 2002 to 2005, where research was conducted, in part, on Risperdal, the company's antipsychotic drug. Biederman has responded saying that the money did not influence him and that he did not promote a specific diagnosis or treatment.[97]

Pharmaceutical companies have also been accused of attempting to set the mental heath agenda through activities such as funding consumer advocacy groups.[108]

Research

- Cannabidiol which differs from the active drug in cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol, may have a potential role in psychosis.[109]

- Metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 agonism has been seen as a promising strategy in the development of novel antipsychotics.[110][111][112] When tested in patients, the research substance LY-214,0023 yielded promising results and had few side effects. The active metabolite of this prodrug targets the brain glutamate receptors mGluR2/3 rather than dopamine receptors.[113]

References

- ^ http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/neuroleptic[full citation needed]

- ^ Moby's Medical Dictionary. Elsevier.

- ^ a b c d Stahl, S. M. (2008). Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Cambridge University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Peluso MJ, Lewis SW, Barnes TR, Jones PB (2012). "Extrapyramidal motor side-effects of first- and second-generation antipsychotic drugs". Br J Psychiatry. 200 (5): 387–92. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101485. PMID 22442101.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Dilsaver, SC.; Alessi, NE. (1988). "Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: phenomenology and pathophysiology". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 77 (3): 241–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb05116.x. PMID 2899377.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Moncrieff, J. (2006). "Why is it so difficult to stop psychiatric drug treatment? It may be nothing to do with the original problem". Med Hypotheses. 67 (3): 517–23. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.03.009. PMID 16632226.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Moncrieff-2006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Choosing the right neuroleptic for a Patient (2008). (PDF) .

- ^ Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ (2008). "Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism". J. Clin. Invest. 118 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1172/JCI32483. PMC 2171144. PMID 18172517.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM (2009). "How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials". Mol. Psychiatry. 14 (4): 429–47. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002136. PMID 18180760.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rattehalli RD, Jayaram MB, Smith M (2010). "Risperidone versus placebo for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD006918. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006918. PMID 20091611.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G; et al. (1992). "Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study". Psychol Med Monogr Suppl. 20: 1–97. doi:10.1017/S0264180100000904. PMID 1565705.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hopper K, Wanderling J (2000). "Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative followup project. International Study of Schizophrenia". Schizophr Bull. 26 (4): 835–46. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033498. PMID 11087016.

- ^ Moncrieff J (2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Harrow M, Jobe TH (2007). "Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: a 15-year multifollow-up study". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 195 (5): 406–14. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000253783.32338.6e. PMID 17502806.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Whitaker R (2004). "The case against antipsychotic drugs: a 50-year record of doing more harm than good". Med. Hypotheses. 62 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00293-7. PMID 14728997.

- ^ a b James, Adam (2 March 2008). "Myth of the antipsychotic". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Leucht S, Heres S, Hamann J, Kane JM (2008). "Methodological issues in current antipsychotic drug trials". Schizophr Bull. 34 (2): 275–85. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm159. PMC 2632403. PMID 18234700.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shen X, Xia J, Adams CE (2012). "Flupenthixol versus placebo for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11: CD009777. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009777.pub2. PMID 23152280.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Harrow M, Jobe TH (2013). "Does Long-Term Treatment of Schizophrenia With Antipsychotic Medications Facilitate Recovery?". Schizophr Bull. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt034. PMID 23512950.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cipriani A, Rendell JM, Geddes J (2009). "Olanzapine in long-term treatment for bipolar disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD004367. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004367.pub2. PMID 19160237.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB; et al. (2004). "Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (2 Suppl): 1–56. PMID 15000267.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Royal College of Psychiatrists & The British Psychological Society (2003). Schizophrenia. Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care (PDF). London: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society.[dead link][page needed]

- ^ Ballard C, Waite J (2006). "The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003476.pub2. PMID 16437455.

- ^ a b Maher AR, Theodore G (2012). "Summary of the comparative effectiveness review on off-label use of atypical antipsychotics". J Manag Care Pharm. 18 (5 Suppl B): S1–20. PMID 22784311.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Maglione, Margaret; Maher, Alicia Ruelaz; Hu, Jianhui; Wang, Zhen; Shanman, Roberta; Roth first8=Lara; Hilton first9=Marika J; Suttorp (2011). Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 43. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 22132426.

{{cite book}}:|first6=missing|last6=(help); Missing pipe in:|last7=(help); Missing pipe in:|last8=(help); Unknown parameter|last6Shekelle first7=ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ Coe HV, Hong IS (2012). "Safety of low doses of quetiapine when used for insomnia". Ann Pharmacother. 46 (5): 718–22. doi:10.1345/aph.1Q697. PMID 22510671.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ American Psychiatric Association and American Psychiatric Association. Work Group on Borderline Personality Disorder (2001). Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 4. ISBN 0890423199. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ Zuddas, A (2011 Aug). "Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) for non-psychotic disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the randomized controlled studies". European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 21 (8): 600–20. PMID 21550212.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pringsheim T, Doja A, Gorman D; et al. (2012). "Canadian guidelines for the evidence-based treatment of tic disorders: pharmacotherapy". Can J Psychiatry. 57 (3): 133–43. PMID 22397999.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McPheeters ML, Warren Z, Sathe N; et al. (2011). "A systematic review of medical treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics. 127 (5): e1312–21. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0427. PMID 21464191.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evidence Lacking to Support Many Off-label Uses of Atypical Antipsychotics (2007)[dead link]. Ahrq.gov.

- ^ James, Anthony C. (2010). "Prescribing antipsychotics for children and adolescents". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 16 (1): 63–75. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.108.005652.

- ^ Romeo R, Knapp M, Tyrer P, Crawford M, Oliver-Africano P (2009). "The treatment of challenging behaviour in intellectual disabilities: cost-effectiveness analysis". J Intellect Disabil Res. 53 (7): 633–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01180.x. PMID 19460067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, Stafford RS (2011). "Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 20: 177–84. PMC 3069498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, Bebbington P (2000). "Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis". BMJ. 321 (7273): 1371–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1371. PMC 27538. PMID 11099280.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Horacek J; Bubenikova-Valesova V; Kopecek M; et al. (2006). "Mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs and the neurobiology of schizophrenia". CNS Drugs. 20 (5): 389–409. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620050-00004. PMID 16696579.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W (2003). "New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 361 (9369): 1581–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13306-5. PMID 12747876.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis JM, Chen N, Glick ID (2003). "A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics". Archives of General Psychiatry. 60 (6): 553–64. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.553. PMID 12796218.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tuunainen A, Wahlbeck K, Gilbody SM (2000). Tuunainen, Arja (ed.). "Newer atypical antipsychotic medication versus clozapine for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000966. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000966. PMID 10796559.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Rosenquist KJ, Pardo TB, Goodwin FK (2006). "Extrapyramidal side effects with atypical neuroleptics in bipolar disorder". Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 30 (2): 209–13. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.10.014. PMID 16412546.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lieberman JA; Stroup TS; McEvoy JP; et al. (2005). "Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (12): 1209–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051688. PMID 16172203.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Meltzer and Bobo (2006) "Interpreting the Efficacy Findings in the CATIE Study: What Clinicians Should Know" CNS Spectr.11(7 Suppl 7):14-24

- ^ Leucht, Stefan; Corves, Caroline; Arbter, Dieter; Engel, Rolf R; Li, Chunbo; Davis, John M (2009). "Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis" (PDF). The Lancet. 373 (9657): 31–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. PMID 19058842.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stroup T; Lieberman, JA; McEvoy, JP; Swartz, MS; Davis, SM; Rosenheck, RA; Perkins, DO; Keefe, RS; Davis, CE (2006). "Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic". Am J Psychiatry. 163 (4): 611–22. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.611. PMID 16585435.