History of Australia: Difference between revisions

m →Peaceful settlement or brutal conquest after 1788?: moved text to section 13 |

→Colonial self-government and the discovery of gold: New section: Australian Democracy |

||

| Line 159: | Line 159: | ||

The late 19th century had however, seen a great growth in the cities of south eastern Australia. Australia's population (not including Aborigines, who were excluded from census calculations) in 1900 was 3.7 million, almost 1 million of whom lived in [[Melbourne]] and [[Sydney]].<ref>C.M.H.Clark (1971) p.666</ref> More than two thirds of the population overall lived in cities and towns by the close of the century, making "Australia one of the most urbanised societies in the western world."<ref>Leigh Astbury (1985)''City Bushmen; the Heidelberg School and the Rural Mythology''. p.2 Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0 19554501 X</ref> |

The late 19th century had however, seen a great growth in the cities of south eastern Australia. Australia's population (not including Aborigines, who were excluded from census calculations) in 1900 was 3.7 million, almost 1 million of whom lived in [[Melbourne]] and [[Sydney]].<ref>C.M.H.Clark (1971) p.666</ref> More than two thirds of the population overall lived in cities and towns by the close of the century, making "Australia one of the most urbanised societies in the western world."<ref>Leigh Astbury (1985)''City Bushmen; the Heidelberg School and the Rural Mythology''. p.2 Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0 19554501 X</ref> |

||

== Australian democracy == |

|||

[[File:Catherine Helen Spence.jpg|thumb|150px|[[South Australia]]n suffragette [[Catherine Helen Spence]] (1825-1910). South Australia granted women the vote in 1894.]] |

|||

Traditional Aboriginal society had been governed in Australia by councils of elders and a corporate decision making process, but the first European style governments in Australia were autocratic sytems run by appointed governors - although English law was transplanted into the Australian colonies, thus [[Magna Carta]] and British and European ideas of the rights and processes of government were brought with the colonists.<ref>http://moadoph.gov.au/our-democracy/democracy-timeline/</ref> The oldest legislative body in Australia, the [[New South Wales Legislative Council]] was created in 1825 as an appointed body to advise the [[Governor of New South Wales|Governor]]. [[William Wentworth]] established the [[Australian Patriotic Association]] (Australia's first political party) in 1835 to demand democratic government for New South Wales. The reformist [[New South Wales Justice and Attorney General's Department|Attorney General of New South Wales]], [[John Plunkett]], sought to apply [[Enlightenment]] principles to governance in the colony, pursuing the establishment of equality before the law, first by extending jury rights to [[emancipist]]s, then by extendeding legal protections to convicts, assigned servants and [[Indigenous Australians|aborigines]]. Plunkett twice charged the colonist perpetrators of the [[Myall Creek massacre]] of Aborigines with murder, resulting in a conviction and his ''Church Act'' of 1836 [[State religion|disestablished]] the Church of England and established legal equality between Anglicans, Catholics, Presbyterians and later Methodists.<ref name=adb>{{cite web |

|||

| first=T. L. |

|||

| last=Suttor |

|||

| title =Plunkett, John Hubert (1802 - 1869) |

|||

| publisher =[[Australian National University]] |

|||

| work=[[Australian Dictionary of Biography]] |

|||

| url =http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A020299b.htm |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-08}}</ref> |

|||

In 1840, the [[Adelaide City Council|Adelaide]] and [[Sydney City Council]] were established. Men who possessed 1000 pounds worth of property were able to stand for election, and wealthy landowners were permitted up to 4 votes each in elections. Australia's first parliamentary elections were conducted for the [[New South Wales Legislative Council]] in 1843, again with voting rights (for males only) tied to property ownership or financial capacity. Voter rights were extended further in New South Wales in 1850 and elections for legislative councils were held in the colonies of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania.<ref>http://aec.gov.au/Elections/Australian_Electoral_History/reform.htm</ref> |

|||

By the mid nineteenth century, there was a strong desire for representative and responsible government in the colonies of Australia, fed by the democratic spirit of the goldfields evident at the [[Eureka Stockade]] and the ideas of the great reform movements sweeping Europe, the [[United States]] and the [[British Empire]]. The end of convict transportation accelerated reform in the 1840s and 1850s. ''The Australian Colonies Government Act'' [1850] was a landmark development which granted representative constitutions to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania and the colonies enthusiastically set about writing constitutions which produced democratically progressive Parliaments - though the constitutions generally maintained the role of the colonial upper houses as representative of social and economic ‘interests’ and all established [[Constitutional Monarchy|Constitutional Monarchies]] with the [[British monarch]] as the symbolic head of state.<ref>http://aec.gov.au/Elections/Australian_Electoral_History/righttovote.htm</ref> |

|||

In 1855, limited self government was granted by London to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. An innovative [[secret ballot]] was introduced in Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia in 1856, in which the government supplied voting paper containing the names of candidates and voters could select in private. This system was adopted around the world, becoming known as the "[[Australian Ballot]]". 1855 also saw the granting of the right to vote to all male British subjects 21 years or over in [[South Australia]]. This right was extended to Victoria in 1857 and New South Wales the following year. The other colonies followed, until in 1896, Tasmania became the last colony to grant universal [[male suffrage]].<ref>http://aec.gov.au/Elections/Australian_Electoral_History/reform.htm</ref> |

|||

Propertied women in the colony of South Australia were granted the vote in local elections (but not parliamentary elections) in 1861. [[Henrietta Dugdale]] formed the first Australian women's suffrage society in [[Melbourne]], Victoria in 1884. Women became eligible to vote for the [[Parliament of South Australia]] in 1895. This was the first legislation in the world permitting women also to stand for election to politcal office and in 1897, [[Catherine Helen Spence]] became the first female political candidate for political office, unsuccessfully standing for election as a delegate to Federal Convention on Australian Federation. [[Western Australia]] granted voting rights to women in 1899.<ref name="aec.gov.au"/><ref>http://foundingdocs.gov.au/item.asp?dID=8</ref> |

|||

Legally, [[Indigenous Australian]] males generally gained the right to vote during this period, when Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia gave voting rights to all male British subjects over 21 - only Queensland and Western Australia barred Aboriginal people from voting. Thus, Aboriginal men and women voted in some juridictions for the first Commonwealth Parliament in 1901. Early federal parliamentary reform and judicial interpretation however sought to limit Aboriginal voting in practice - a situation which endured until rights activists began campaigning in the 1940s.<ref>http://aec.gov.au/Voting/indigenous_vote/aborigin.htm</ref> |

|||

==Growth of nationalism and federation== |

==Growth of nationalism and federation== |

||

Revision as of 16:13, 1 January 2011

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for tens of thousands of years. During that time, oral history, some aspects dating from extreme antiquity, was passed down through the generations in the form of spoken allegories, poems, myths, and songs.

While there was a long established European tradition of a Great South Land, the written history of Australia began in 1606, when during a voyage of discovery from Bantam, Willem Janszoon, commanding the Duyfken encountered the Australian mainland.

Aboriginal Australians

Aborigines before 1788

The consensus among scholars for the arrival of humans of Australia is placed at 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, but possibly as early as 70,000 years ago.[1][2] The earliest human remains found to date are those found at Lake Mungo, a dry lake in the south west of New South Wales. These have been dated at about 40,000 years old.[3] At the time of first European contact, it has been estimated the population of Australian Aborigines was at least 350,000,[4][5] while recent archaeological finds suggest that a population of 750,000 could have been sustained.[6][7] The ancestors of the Aborigines appear to have arrived by sea during one of the earth’s periods of glaciation, when New Guinea and Tasmania were joined to the continent. The journey still required sea travel however, making them amongst the world’s earlier mariners.[8]

By 1788, the population existed as 250 individual nations, many of which were in alliance with one another, and within each nation there existed several clans, from as few as five or six to as many as 30 or 40. Each nation had its own language and a few had multiple, thus over 250 languages existed, around 200 of which are now extinct. "Intricate kinship rules ordered the social relations of the people and diplomatic messengers and meeting rituals smoothed relations between groups," keeping group fighting, sorcery and domestic disputes to a minimum.[9]

The mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from nation to nation. Some early European observers like William Dampier described the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the Aborigines as arduous and "miserable". In fact, as historians like Geoffrey Blainey argue, the material standard of living for Aborigines was generally high, higher than that of many Europeans living at the time of the Dutch discovery of Australia.[10] Astute 19th century settlers like Edward Curr also observed that Aborigines "suffered less and enjoyed life more than the majority of civilized(sic) men."[11] In south eastern Australia, near present day Lake Condah, semi-permanent villages of beehive shaped shelters of stone developed, near bountiful food supplies.[12] For centuries, Macassan trade flourished with Aborigines on Australia's north coast, particularly with the Yolngu people of north-east Arnhem Land.

The greatest population density was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the River Murray valley in particular. Aborigines lived and utilised resources on the continent sustainably, agreeing to cease hunting and gathering at particular times to give populations and resources the chance to replenish. "Firestick farming" amongst northern Australian people was used to encourage plant growth that attracted animals.[13] Aborigines were amongst the oldest, most sustainable and most isolated cultures on Earth prior to European settlement beginning in 1788.

However, life for Aborigines was not without significant changes. Some 10-12,000 years ago, Tasmania became isolated from the mainland, and some stone technologies failed to reach the Tasmanian people (such as the hafting of stone tools and the use of the Boomerang).[14] The land was not always kind; Aboriginal people of south eastern Australia endured "more than a dozen volcanic eruptions…(including) Mount Gambier, a mere 1,400 years ago."[15] There is evidence that when necessary, Aborigines could keep control of their population growth and in times of drought or arid areas were able to maintain reliable water supplies.

Some of the Pintupi people successfully lived their traditional lifestyle in the Gibson Desert long after the arrival of Europeans. The last group did not meet modern Australia until 1984.[16]

When Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri first saw a European he said "I couldn't believe it. I thought he was the devil, a bad spirit and was the colour of clouds at sunrise.[16]

Peaceful settlement or brutal conquest after 1788?

Australian Historian Henry Reynolds argues that there was a "historical neglect" of the Aborigines by historians until the late 1960s.[18] Early commentaries on the Australian colonies often tended to describe Aborigines as doomed to extinction following the arrival of Europeans. For example, William Westgarth’s 1864 book on the colony of Victoria observed; "the case of the Aborigines of Victoria confirms …it would seem almost an immutable law of nature that such inferior dark races should disappear."[19]

In 1968 anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner described the lack of historical accounts of relations between Europeans and Aborigines as "the great Australian silence."[20] It was partly a play on the title of Douglas Pike’s 1962 book "The Quiet Continent," which argued Australian history was largely peaceful.[21] However, by the early 1970s historians like Lyndall Ryan, Henry Reynolds and Raymond Evans were trying to document and estimate the conflict and human toll on the frontier.

It is now accepted by many academics that the impact of the arrival of Europeans was profoundly disruptive to Aboriginal life and there was considerable conflict on the frontier. Even before the arrival of settlers in all parts of Australia, European disease had preceded them. "In 1789, the second year of European settlement…a smallpox epidemic wiped out about half the Aborigines around Sydney." It then spread well beyond the then limits of European settlement, including much of south eastern Australia, reappearing in 1829-1830, killing 40-60% of the Aboriginal population.[22]

At the same time, some settlers were quite aware they were usurping the Aborigines place in Australia. In 1845, settler Charles Griffiths sought to justify this, writing; "The question comes to this; which has the better right – the savage, born in a country, which he runs over but can scarcely be said to occupy…or the civilized man, who comes to introduce into this…unproductive country, the industry which supports life."[23] In expressing this view, Griffiths was probably merely echoing opinions widely held by other colonists in Australia, South Africa, parts of South America and the United States.

The story of Aboriginal-settler conflict has been described by modern historians in numerous ways, from "lamentable"[24] to "disastrous."[25] There are many events that illustrate the extent of the violence and resistance as Aborigines sought to protect their lands from invasion and as settlers and pastoralists attempted to establish their presence and protect their investments. In May 1804, at Risdon Cove, Van Diemen's Land,[26] perhaps 60 Aborigines were killed when they approached the town.[27] From the mid 1820s until the early 1830s, the Black War raged in Van Diemen's Land. In 1838, at least twenty-eight Aborigines were murdered at the Myall Creek in New South Wales. The seven convict settlers responsible for this massacre were hanged.[28] Aborigines were far from helpless however, for example in April 1838 fourteen Europeans were killed at Broken River in Port Phillip District, by Aborigines of the Ovens River, almost certainly in revenge for the illicit use of Aboriginal women.[29] The most recent massacre of Aborigines was at Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928. There are numerous other massacre sites in Australia, although supporting documentation varies.

That a murderous intent existed amongst many European settlers there appears little doubt. Captain Hutton of Port Phillip District once told Chief Protector of Aborigines George Augustus Robinson that "if a member of a tribe offend, destroy the whole."[30] Queensland’s Colonial Secretary A.H. Palmer wrote in 1884 "the nature of the blacks was so treacherous that they were only guided by fear – in fact it was only possible to rule…the Australian Aboriginal…by brute force"[31]

The removal of indigenous children, which the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission argue constituted attempted genocide,[32] had a major impact on the Indigenous population.[33] Such interpretations of Aboriginal history are disputed by Keith Windschuttle as being exaggerated or fabricated for political or ideological reasons.[34] This debate is part of what is known within Australia as the History Wars.

European exploration

Several writers have made attempts to prove that Europeans visited Australia during the 16th century. Kenneth McIntyre and others have argued that the Portuguese had secretly discovered Australia in the 1520s.[35] The presence of a landmass labelled "Jave la Grande" on the Dieppe Maps is often cited as evidence for a "Portuguese discovery". However, the Dieppe Maps also openly reflected the incomplete state of geographical knowledge at the time, both actual and theoretical.[36] And it has also been argued that Jave la Grande was a hypothetical notion, reflecting 16th century notions of cosmography. Although theories of visits by Europeans, prior to the 17th century, continue to attract popular interest in Australia and elsewhere, they are generally regarded as contentious and lacking substantial evidence.

Willem Janszoon is credited with the first authenticated European discovery of Australia in 1606.[37] Luis Váez de Torres passed through Torres Strait in the same year and may have sighted Australia's northern coast.[38] Janszoon's discoveries inspired several mariners, among them, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman, to further chart the area.

In 1616, Dutch sea-captain Dirk Hartog sailed too far whilst trying out Henderik Brouwer's recently discovered route from the Cape of Good Hope to Batavia, via the Roaring Forties. Reaching the western coast of Australia, he landed at Cape Inscription in Shark Bay on 25 October 1616. His is the first known record of a European visiting Western Australia's shores.

Although Abel Tasman is best known for his voyage of 1642; in which he became the first known European to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land (later Tasmania) and New Zealand, and to sight the Fiji islands, he also contributed significantly to the mapping of Australia proper. With three ships on his second voyage (Limmen, Zeemeeuw and the tender Braek) in 1644, he followed the south coast of New Guinea westward. He missed the Torres Strait between New Guinea and Australia, but continued his voyage along the Australian coast and ended up mapping the north coast of Australia making observations on the land and its people.[39]

By the 1650s, as a result of the Dutch discoveries, most of the Australian coast was charted reliably enough for the navigational standards of the day, and this was revealed for all to see in the map of the world inlaid into the floor of the Burgerzaal ("Burger's Hall") of the new Amsterdam Stadhuis ("Town Hall") in 1655. Although various proposals for colonisation were made, notably by Pierre Purry from 1717 to 1744, none were officially attempted.[40] Indigenous Australians were less interested in and able to trade with Europeans, than the peoples of India, the East Indies, China and Japan. The Dutch East India Company concluded that there was "no good to be done there". They turned down Purry’s scheme with the comment that, "There is no prospect of use or benefit to the Company in it, but rather very certain and heavy costs".

With the exception of further Dutch visits to the west, however, Australia remained largely unvisited by Europeans until the first British explorations. In 1769, Lieutenant James Cook in command of the HMS Endeavour, traveled to Tahiti to observe and record the transit of Venus. Cook also carried secret Admiralty instructions to locate the supposed Southern Continent:[41] "There is reason to imagine that a continent, or land of great extent, may be found to the southward of the track of former navigators."[42] On 19 April 1770, the crew of the Endeavour sighted the east coast of Australia and ten days later landed at Botany Bay.

In 1772, a French expedition led by Louis Aleno de St Aloüarn, became the first Europeans to formally claim sovereignty over the west coast of Australia, but no attempt was made to follow this with colonisation.[43]

The ambition of Sweden’s King Gustav III to establish a colony for his country at the Swan River in 1786 remained stillborn.[44] It was not until 1788 that economic, technological and political conditions in Great Britain made it possible and worthwhile for that country to make the large effort of sending the First Fleet to New South Wales.[45]

British settlement and colonisation

Plans for colonisation

Seventeen years after Cook's landfall on the east coast of Australia, the British government decided to establish a colony at Botany Bay.

In 1779 Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended Botany Bay as a suitable site.[46] Banks accepted an offer of assistance made by the American Loyalist James Matra in July 1783. Matra had visited Botany Bay with Banks in 1770 as a junior officer on the Endeavour commanded by James Cook. Under Banks’s guidance, he rapidly produced "A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales" (23 August 1783), with a fully developed set of reasons for a colony composed of American Loyalists, Chinese and South Sea Islanders (but not convicts).[47]

These reasons were: the country was suitable for plantations of sugar, cotton and tobacco; New Zealand timber and hemp or flax could prove valuable commodities; it could form a base for trade with China, Korea, Japan, the North West coast of America, and with the Moluccas; and it could be a suitable compensation for displaced American Loyalists, "where they may repair their broken fortunes & again enjoy their former domestick felicity".[48]

Following an interview with Secretary of State Lord Sydney in March 1784, Matra amended his proposal to include convicts as settlers:

When I conversed with Lord Sydney on this Subject, it was observed that New South Wales would be a very proper Region for the reception of Criminals condemned to Transportation. I believe that it will be found, that in this Idea, good Policy, & Humanity are united.... By the Plan which I have now proposed....two Objects of most desirable and beautiful Union, will be permanently blended: Economy to the Publick, & Humanity to the Individual.[49]

Matra’s plan can be seen to have "provided the original blueprint for settlement in New South Wales".[50] A cabinet memorandum December 1784 shows the government had Matra’s plan in mind when considering the erection of a settlement in New South Wales.[51] The Government also incorporated into the colonisation plan the project for settling Norfolk Island, with its attractions of timber and flax, proposed by Banks’s Royal Society colleagues, Sir John Call and Sir George Young.[52]

At the same time, humanitarians and reformers were campaigning in Britain against the appalling conditions in British prisons and hulks. In 1777 prison reformer John Howard "wrote The State of Prisons in England and Wales which painted a devastating picture of the reality of prisons and brought into the open much of what had been out of sight ...to genteel society."[53] Penal transportation was already well established as a central plank of English criminal law and until the American War of Independence about a thousand criminals per year were sent to Maryland and Virgina.[54] It served as a powerful deterrent to lawbreaking. At the time, "Europeans knew little about the geography of the globe" and to "convicts in England, transportation to Botany Bay was a frightening prospect." Australia "might as well have been another planet."[55]

In the early 1960s, historian Geoffrey Blainey questioned the traditional view that New South Wales was founded purely as a convict dumping ground. His book The Tyranny of Distance[56] suggested ensuring supplies of flax and timber after the loss of the American colonies may have also been motivations for the British government, and Norfolk Island was the key to the British decision. A number of historians responded, although the debate attracted limited interest beyond academic circles. One result of the debate has been to bring to light a large amount of additional source material on the reasons for settlement.[57]

The decision to settle New South Wales was taken when it seemed the outbreak of civil war in the Netherlands might precipitate a war in which Britain would be again confronted with the alliance of the three naval Powers, France, Holland and Spain, which had brought her to defeat in 1783. Under these circumstances, the attractions were obvious of the strategic advantages of a colony in New South Wales described in James Matra's proposal.[58] Matra indicated how a settlement in New South Wales could facilitate British attacks upon the Spanish colonies in South America and the Philippines, and against the Dutch possessions in the East Indies: "If a Colony from Great Britain was established in that large Tract of Country, and if we were at War with Holland or Spain, we might very powerfully annoy either State from our new Settlement. We might, with a safe and expeditious Voyage, make Naval Incursions on Java and the other Dutch Settlements, and we might with equal facility invade the Coasts of Spanish America, and intercept the Manilla Ships, laden with the Treasures of the West."[59] In 1790, during the Nootka Crisis, plans were made for naval expeditions against Spain’s possessions in the Americas and the Philippines, in which the newly established colony in New South Wales was assigned the role of a base for “refreshment, communication and retreat”. On every subsequent occasion during the following decade and a half of the 1790s and early 19th century when war threatened or broke out between Britain and Spain, these plans were revived and only the short length of the period of hostilities in each case prevented them from being put into effect.[60]

British settlements in Australia

The British colony of New South Wales was established with the arrival of the First Fleet of 11 vessels under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip in January 1788. The First Fleet consisted of over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts (192 women and 586 men).[61] A few days after arrival at Botany Bay the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788.[62] This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day. The colony was formally proclamed by Governor Arthur Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney Cove in Port Jackson. The first white person born in Australia was Rebekah Small, born to one of the women who had come on the First Fleet shortly after the Fleet landed.[63]

The territory claimed included all of that portion of the continent of Australia eastward of the meridian of 135° East and all the islands in the Pacific Ocean between the latitudes of Cape York and the southern tip of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). The extent of this territorial claim excited the amazement of many when they first learned of it. "Extent of Empire demands grandeur of design", wrote Watkin Tench in A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay.[64] "Truly an astonishing extent!" remarked the Dutch translator of Tench’s book, who went on to say: "The outermost or easternmost of the Marquesas Islands lie, even according to the English maps, at least eighty-five degrees eastward of the line where they place the commencement of the Territory of New South Wales. They have therefore formed a single province which, beyond all doubt, is the largest on the whole surface of the earth. From their definition it covers, in its greatest extent from East to West, virtually a fourth of the whole circumference of the Globe".[65]

The colony included the current islands of New Zealand, which was administered as part of New South Wales. In 1817, the British government withdrew the extensive territorial claim over the South Pacific. In practice, the governors' writ had been shown not to run in the islands of the South Pacific.[66] The Church Missionary Society in London described the many atrocities which had been committed against the natives of the South Sea Islands, and the ineffectiveness of the New South Wales government and courts to deal with this lawless situation. As a result, on 27 June 1817 Parliament passed an Act for the more effectual Punishment of Murders and Manslaughters committed in Places not within His Majesty's Dominions, which described Tahiti, New Zealand and other islands of the South Pacific as being not within His Majesty's dominions.[67]

Romantic descriptions of the beauty, mild climate, and fertile soil of Norfolk Island in the South Pacific led the British government to establish a subsidiary settlement of the New South Wales colony there in 1788. It was hoped that the giant Norfolk Island pine trees and flax plants growing wild on the island might provide the basis for a local industry which, particularly in the case of flax, would provide an alternative source of supply to Russia for an article which was essential for making cordage and sails for the ships of the British navy. However, the island had no safe harbor, which led the colony to be abandoned and the settlers evacuated to Tasmania in 1807.[68] The island was subsequently re-settled as a penal settlement in 1824.

Van Diemen's Land, now known as Tasmania, was settled in 1803, following a failed attempt to settle at Sullivan Bay in what is now Victoria. Other British settlements followed, at various points around the continent, many of them unsuccessful. The East India Trade Committee recommended in 1823 that a settlement be established on the coast of northern Australia to forestall the Dutch, and Captain J.J.G.Bremer, RN, was commissioned to form a settlement between Bathurst Island and the Cobourg Peninsula. Bremer fixed the site of his settlement at Fort Dundas on Melville Island in 1824 and, because this was well to the west of the boundary proclaimed in 1788, proclaimed British sovereignty over all the territory as far west as Longitude 129˚ East.[69]

The new boundary included Melville and Bathurst Islands, and the adjacent mainland. In 1826, the British claim was extended to the whole Australian continent when Major Edmund Lockyer established a settlement on King George Sound (the basis of the later town of Albany), but the eastern border of Western Australia remained unchanged at Longitude 129˚ East. In 1824, a penal colony was established near the mouth of the Brisbane River (the basis of the later colony of Queensland). In 1829, the Swan River Colony and its capital of Perth were founded on the west coast proper and also assumed control of King George Sound. Initially a free colony, Western Australia later accepted British convicts, because of an acute labour shortage.

The German scientist and man of letters Georg Forster, who had sailed under Captain James Cook in the voyage of the Resolution (1772–1775), wrote a remarkably prescient essay in 1786 on the future prospects of the English colony, in which he said: "New Holland, an island of enormous extent or it might be said, a third continent, is the future homeland of a new civilized society which, however mean its beginning may seem to be, nevertheless promises within a short time to become very important."[70]

Convicts and colonial society

Jan Bassett estimates that between 1788 and 1868, 161,700 convicts (of whom 25,000 were women) were transported to the Australian colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemen’s land and Western Australia.[71] Historian Lloyd Robson has estimated that perhaps two thirds were thieves from working class towns, particularly from the midlands and north of England. The majority were repeat offenders.[72] Whether transportation managed to achieve its goal of reforming or not, some convicts were able to leave the prison system in Australia; after 1801 they could gain "tickets of leave" for good behaviour and be assigned to work for free men for wages. A few went on to have successful lives as emancipists, having been pardoned at the end of their sentence. Female convicts had fewer opportunities.

The first five Governors of New South Wales realised the urgent need to encourage free settlers, but the British government remained largely indifferent. As early as 1790, Governor Arthur Phillip wrote; "Your lordship will see by my…letters the little progress we have been able to make in cultivating the lands ... At present this settlement only affords one person that I can employ in cultivating the lands..."[73] It was not until the 1820s that numbers of free settlers began to arrive and government schemes began to be introduced to encourage free settlers. Philanthropists Caroline Chisholm and John Dunmore Lang developed their own migration schemes. Land grants of crown land were made by Governors, and settlement schemes such as those of Edward Gibbon Wakefield carried some weight in encouraging migrants to make the long voyage to Australia, as opposed to the United States or Canada.[74]

From the 1820s, increasing numbers of Squatters[75] occupied land beyond the fringes of European settlement. Often running sheep on large stations with relatively few overheads, Squatters could make considerable profits. By 1834, nearly 2 million kilograms of wool were being exported to Britain from Australia.[76] By 1850, barely 2,000 Squatters had gained 30 million hectares of land, and they formed a powerful and "respectable" interest group in several colonies.[77]

In 1835, the British Colonial Office issued the Proclamation of Governor Bourke, implementing the legal doctrine of terra nullius upon which British settlement was based, reinforcing the notion that the land belonged to no one prior to the British Crown taking possession of it and quashing any likelihood of treaties with Aboriginal peoples, including that signed by John Batman. Its publication meant that from then, all people found occupying land without the authority of the government would be considered illegal trespassers.[78]

Separate settlements and later, colonies, were created from parts of New South Wales: South Australia in 1836, New Zealand in 1840, Port Phillip District in 1834, later becoming the colony of Victoria in 1851, and Queensland in 1859. The Northern Territory was founded in 1863 as part of South Australia. The transportation of convicts to Australia was phased out between 1840 and 1868.

Massive areas of land were cleared for agriculture and various other purposes in the first 100 years of Europeans settlement. In addition to the obvious impacts this early clearing of land and importation of hard-hoofed animals had on the ecology of particular regions, it severely affected indigenous Australians, by reducing the resources they relied on for food, shelter and other essentials. This progressively forced them into smaller areas and reduced their numbers as the majority died of newly introduced diseases and lack of resources. Indigenous resistance against the settlers was widespread, and prolonged fighting between 1788 and the 1920s led to the deaths of at least 20,000 Indigenous people and between 2,000 and 2,500 Europeans.[79] During the mid-late 19th century, many indigenous Australians in south eastern Australia were relocated, often forcibly, to reserves and missions. The nature of many of these institutions enabled disease to spread quickly and many were closed as their populations fell.

Colonial self-government and the discovery of gold

The discovery of gold in Australia is traditionally attributed to Edward Hammond Hargraves, near Bathurst, New South Wales, in February 1851. It is now accepted that traces of gold had been found in Australia as early as 1823 by surveyor James McBrien. As by English law all minerals belonged to the Crown, there was at first, "little to stimulate a search for really rich goldfields in a colony prospering under a pastoral economy."[80] Richard Broome also argues that the California Gold Rush at first overawed the Australian finds, until "the news of Mount Alexander reached England in May 1852, followed shortly by six ships carrying eight tons of gold."[81]

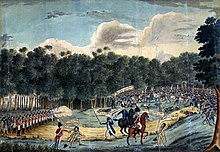

The gold rushes brought many immigrants to Australia from Great Britain, Ireland, continental Europe, North America and China. For example, the Colony of Victoria’s population grew rapidly, from 76,000 in 1850 to 530,000 by 1859.[82] Discontent arose amongst diggers almost immediately, particularly on the crowded Victorian fields. The causes of this were the colonial government’s administration of the diggings and the gold licence system. Following a number of protests and petitions for reform, violence erupted at Ballarat in late 1854.

Early on the morning of Sunday 3 December 1854, British soldiers and Police attacked a stockade built on the Eureka lead holding some of the aggrieved diggers. In a short fight, at least 30 miners were killed and an unknown number wounded.[83] Blinded by his fear of agitation with democratic overtones, local Commissioner Robert Rede had felt "it was absolutely necessary that a blow should be struck" against the miners.[84]

But a few months later, a Royal commission made sweeping changes to the administration of Victoria’s goldfields. Its recommendations included the abolition of the licence, reforms to the police force and voting rights for miners holding a Miner’s Right.[85] The Eureka flag that was used to represent the Ballarat miners has been seriously considered by some as an alternative to the Australian flag, because of its association with democratic developments.

In the 1890s, visiting author Mark Twain famously characterised the battle at Eureka as:

The finest thing in Australasian history. It was a revolution-small in size, but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a stand against injustice and oppression...it is another instance of a victory won by a lost battle.[86]

Later Australian gold rushes occurred at the Palmer River, Queensland, in the 1870s, and Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, in the 1890s. Confrontations between Chinese and European miners occurred on the Buckland River in Victoria and Lambing Flat in New South Wales, in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Driven by European jealousy of the success of Chinese efforts as alluvial (surface) gold ran out, it fixed emerging Australian attitudes in favour of a White Australia policy, according to historian Geoffrey Serle.[87]

New South Wales in 1855 was the first colony to gain responsible government, managing most of its own affairs while remaining part of the British Empire. Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia followed in 1856; Queensland, from its foundation in 1859; and Western Australia, in 1890. The Colonial Office in London retained control of some matters, notably foreign affairs, defence and international shipping.

The gold era led to a long period of prosperity, sometimes called "the long boom."[88] This was fed by British investment and the continued growth of the pastoral and mining industries, in addition to the growth of efficient transport by rail, river and sea. By 1891, the sheep population of Australia was estimated at 100 million. Gold production had declined since the 1850s, but in the same year was still worth £5.2 million.[89] Eventually the economic expansion came to an end, and the 1890s were a period of economic depression, felt most strongly in Victoria, and its capital Melbourne.

The late 19th century had however, seen a great growth in the cities of south eastern Australia. Australia's population (not including Aborigines, who were excluded from census calculations) in 1900 was 3.7 million, almost 1 million of whom lived in Melbourne and Sydney.[90] More than two thirds of the population overall lived in cities and towns by the close of the century, making "Australia one of the most urbanised societies in the western world."[91]

Australian democracy

Traditional Aboriginal society had been governed in Australia by councils of elders and a corporate decision making process, but the first European style governments in Australia were autocratic sytems run by appointed governors - although English law was transplanted into the Australian colonies, thus Magna Carta and British and European ideas of the rights and processes of government were brought with the colonists.[92] The oldest legislative body in Australia, the New South Wales Legislative Council was created in 1825 as an appointed body to advise the Governor. William Wentworth established the Australian Patriotic Association (Australia's first political party) in 1835 to demand democratic government for New South Wales. The reformist Attorney General of New South Wales, John Plunkett, sought to apply Enlightenment principles to governance in the colony, pursuing the establishment of equality before the law, first by extending jury rights to emancipists, then by extendeding legal protections to convicts, assigned servants and aborigines. Plunkett twice charged the colonist perpetrators of the Myall Creek massacre of Aborigines with murder, resulting in a conviction and his Church Act of 1836 disestablished the Church of England and established legal equality between Anglicans, Catholics, Presbyterians and later Methodists.[93]

In 1840, the Adelaide and Sydney City Council were established. Men who possessed 1000 pounds worth of property were able to stand for election, and wealthy landowners were permitted up to 4 votes each in elections. Australia's first parliamentary elections were conducted for the New South Wales Legislative Council in 1843, again with voting rights (for males only) tied to property ownership or financial capacity. Voter rights were extended further in New South Wales in 1850 and elections for legislative councils were held in the colonies of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania.[94]

By the mid nineteenth century, there was a strong desire for representative and responsible government in the colonies of Australia, fed by the democratic spirit of the goldfields evident at the Eureka Stockade and the ideas of the great reform movements sweeping Europe, the United States and the British Empire. The end of convict transportation accelerated reform in the 1840s and 1850s. The Australian Colonies Government Act [1850] was a landmark development which granted representative constitutions to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania and the colonies enthusiastically set about writing constitutions which produced democratically progressive Parliaments - though the constitutions generally maintained the role of the colonial upper houses as representative of social and economic ‘interests’ and all established Constitutional Monarchies with the British monarch as the symbolic head of state.[95]

In 1855, limited self government was granted by London to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. An innovative secret ballot was introduced in Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia in 1856, in which the government supplied voting paper containing the names of candidates and voters could select in private. This system was adopted around the world, becoming known as the "Australian Ballot". 1855 also saw the granting of the right to vote to all male British subjects 21 years or over in South Australia. This right was extended to Victoria in 1857 and New South Wales the following year. The other colonies followed, until in 1896, Tasmania became the last colony to grant universal male suffrage.[96]

Propertied women in the colony of South Australia were granted the vote in local elections (but not parliamentary elections) in 1861. Henrietta Dugdale formed the first Australian women's suffrage society in Melbourne, Victoria in 1884. Women became eligible to vote for the Parliament of South Australia in 1895. This was the first legislation in the world permitting women also to stand for election to politcal office and in 1897, Catherine Helen Spence became the first female political candidate for political office, unsuccessfully standing for election as a delegate to Federal Convention on Australian Federation. Western Australia granted voting rights to women in 1899.[97][98]

Legally, Indigenous Australian males generally gained the right to vote during this period, when Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia gave voting rights to all male British subjects over 21 - only Queensland and Western Australia barred Aboriginal people from voting. Thus, Aboriginal men and women voted in some juridictions for the first Commonwealth Parliament in 1901. Early federal parliamentary reform and judicial interpretation however sought to limit Aboriginal voting in practice - a situation which endured until rights activists began campaigning in the 1940s.[99]

Growth of nationalism and federation

By the late 1880s, a majority of people living in the Australian colonies were native born, although over 90% were of British and Irish origin.[100] Historian Don Gibb suggests that bushranger Ned Kelly represented one dimension of the emerging attitudes of the native born population. Identifying strongly with family and mates, Kelly was opposed to what he regarded as oppression by Police and powerful Squatters. Almost mirroring the Australian stereotype later defined by historian Russel Ward, Kelly became "a skilled bushman, adept with guns, horses and fists and winning admiration from his peers in the district."[101] Journalist Vance Palmer suggested although Kelly came to typify "the rebellious persona of the country for later generations, (he really) belonged...to another period."[102]

Despite suspicion from some sections of the colonial community (especially in smaller colonies) about the value of nationhood, improvements in inter-colonial transport and communication, including the linking of Perth to the south eastern cities by telegraph in 1877,[103] helped break down inter-colonial rivalries. By 1895, powerful interests including various colonial politicians, the Australian Natives' Association and some newspapers were advocating Federation. Increasing nationalism, a growing sense of national identity amongst white colonial Australians, as well as a desire for a national immigration policy, (to become the white Australia policy), combined with a recognition of the value of collective national defence also encouraged the Federation movement. The vision of most colonists was probably staunchly imperial however. At a Federation Conference banquet in 1890, New South Wales politician Henry Parkes said

The crimson thread of kinship runs through us all. Even the native born Australians[104] are Britons as much as those born in London or Newcastle. We all know the value of that British origin. We know that we represent a race for which the purpose of settling new countries has never had its equal on the face of the earth... A united Australia means to me no separation from the Empire.[105]

Despite a more radical vision for a separate Australia by some colonists, including writer Henry Lawson, trade unionist William Lane and as found in the pages of the Sydney Bulletin, by the end of 1899, and after much colonial debate, the citizens of five of the six Australian colonies had voted in referendums in favour of a constitution to form a Federation. Western Australia voted to join in July 1900. The "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (UK)" was passed on 5 July 1900 and given Royal Assent by Queen Victoria on 9 July 1900.[106]

The bush ballad Waltzing Matilda, written in 1895 by poet Banjo Paterson,[107] has sometimes been suggested as a Australia's national anthem. Advance Australia Fair, the Australian national anthem since the late 1970s, was written in 1887. The Heidelberg School of Australian painting, inspired by the European Impressionist movement, also emerged in the 1880s and created "the first distinctive Australian school of painting."[108] A common theme throughout the nationalist art, music and writing of late 19th century was the romantic rural or bush myth, ironically produced by one of the most urbanised societies in the world.[109] Paterson's well known poem Clancy of the Overflow, written in 1889, evokes the romantic myth.

A new nation for the 20th century

Immigration and defence concerns

The Commonwealth of Australia came into being when the Federal Constitution was proclaimed by the Governor General, Lord Hopetoun, on 1 January 1901. The first Federal elections were held in March 1901. Edmund Barton, the first Australian Prime Minister, laid out his policies almost immediately, his first speech reflecting many of the concerns of the time. Barton promised to "create a high court, ...and an efficient federal public service... He proposed to extend conciliation and arbitration, create a uniform railway gauge between the eastern capitals,[110] to introduce female federal franchise, to establish a...system of old age pensions."[111] He also promised to introduce legislation to safeguard "White Australia" from any influx of Asian or Pacific Island labour.

The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was one of the first laws passed by the new Australian parliament. Aimed to restrict immigration from Asia (especially China), it found strong support in the national parliament, arguments ranging from economic protection to outright racism.[112] A few politicians spoke of the need to avoid hysterical treatment of the question. Member of Parliament Bruce Smith said he had "no desire to see low-class Indians, Chinamen or Japanese...swarming into this country... But there is obligation...not (to) unnecessarily offend the educated classes of those nations"[113] Actual dissent was rare. Donald Cameron, a member from Tasmania expressed views perhaps 100 years before his time when he opposed the law, stating

I would like to ask...what treatment the Chinese have received from the English people as a race? I say, without fear of contradiction that no race on...this earth has been treated in a more shameful manner than have the Chinese... They were forced at the point of a bayonet to admit Englishmen...into China. Now if we compel them to admit our people...why in the name of justice should we refuse to admit them here?[114]

The law passed both houses of Parliament and remained a central feature of Australia's immigration laws until abandoned in the 1950s. The absurdity of the law (which allowed for a dictation test in "any European language" to be given to arrivals in Australia), was most famously demonstrated in the Egon Kisch case in the 1930s.[115]

Before 1901, units of soldiers from all six Australian colonies had been active as part of British forces in the Boer War. When the British government asked for more troops from Australia in early 1902, the Australian government obliged with a national contingent. Some 16,500 men had volunteered for service by the war's end in June 1902.[116] But Australians soon felt vulnerable closer to home. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 "allowed the Royal Navy to withdraw its capital ships from the Pacific by 1907. Australians saw themselves in time of war a lonely, sparsely populated outpost."[117] The impressive visit of the US Navy's Great White Fleet in August–September 1908 emphasised to the Australian government the value of an Australian navy. The Defence Act of 1909 reinforced the importance of Australian defence, and in February 1910, Lord Kitchener provided further advice on a defence scheme based on conscription. By 1913, the Battle Cruiser Australia led the fledgling Royal Australian Navy. Historian Bill Gammage estimates on the eve of war, Australia had 200,000 men "under arms of some sort".[118]

Dominion status

Australia achieved independent Sovereign Nation status after World War One, under the Statute of Westminster. This formalised the Balfour Declaration of 1926, a report resulting from the 1926 Imperial Conference of British Empire leaders in London, which defined Dominions of the British empire in the following way

They are autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.[119]

However, Australia did not ratify the Statute of Westminster until 1942. According to historian Frank Crowley, this was because Australians had little interest in redefining their relationship with Britain until the crisis of World War Two.[120]

The Australia Act 1986 removed any remaining links between the British Parliament and the Australian states.

From 1 February 1927 until 12 June 1931, the Northern Territory was divided up as North Australia and Central Australia at latitude 20°S. New South Wales has had one further territory surrendered, namely Jervis Bay Territory comprising 6,677 hectares, in 1915. The external territories were added: Norfolk Island (1914); Ashmore Island, Cartier Islands (1931); the Australian Antarctic Territory transferred from Britain (1933); Heard Island, McDonald Islands, and Macquarie Island transferred to Australia from Britain (1947).

The Federal Capital Territory (FCT) was formed from New South Wales in 1911 to provide a location for the proposed new federal capital of Canberra (Melbourne was the seat of government from 1901 to 1927). The FCT was renamed the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) in 1938. The Northern Territory was transferred from the control of the South Australian government to the Commonwealth in 1911.

The emergence of party politics and competing visions of Australia

The Australian Labor Party (ALP) (the spelling "Labour" was dropped in 1912) had been established in the 1890s, after the failure of the Maritime and Shearer’s strikes. Its strength was in the Australian Trade Union movement "which grew from a membership of just under 100,000 in 1901 to more than half a million in 1914."[121] While the platform of the ALP was democratic socialist, the rise of its support at elections, together with its formation of federal government in 1904, and again in 1908, helped to unify competing conservative, free market and anti-socialist forces into the Commonwealth Liberal Party in 1909. The Country Party of Australia was formed in 1913 to represent rural interests.

Historians like Humphrey McQueen argue that in terms of working and living conditions for Australia’s working classes, the years of early 20th century were ones of "frugal comfort."[122] While the establishment of an Arbitration court for Labour disputes was divisive, it was an acknowledgement of the need to set Industrial awards, where all wage earners in one industry enjoyed the same conditions of employment and wages. The Harvester Judgment of 1907 also set a benchmark in Australian labour law by recognising the concept of a basic wage. In 1908 the Federal government also began an old age pension scheme.

Catastrophic droughts plagued areas of Australia between in the late 1890s and early 20th century and together with a growing rabbit plague, created great hardship in rural Australia. Despite this, a number of writers "imagined a time when Australia would outstrip Britain in wealth and importance, when its open spaces would support rolling acres of farms and factories to match those of the United States. Some estimated the future population at 100 million, 200 million or more."[123] Amongst these was E. J. Brady, whose 1918 book Australia Unlimited described Australia’s inland as ripe for development and settlement, "destined one day to pulsate with life."[124]

To the last shilling; the First World War

The outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914 automatically involved "all of Britain's colonies and dominions".[125] Prime Minister Andrew Fisher probably expressed the views of most Australians when during the election campaign of late July he said

Turn your eyes to the European situation, and give the kindest feelings towards the mother country...I sincerely hope that international arbitration will avail before Europe is convulsed in the greatest war of all time... But should the worst happen...Australians will stand beside our own to help and defend her to the last man and the last shilling.[125]

More than 416,000 Australian men volunteered to fight during the First World War between 1914 and 1918[126] from a total national population of 4.9 million.[127] Historian Lloyd Robson estimates this as between one third and one half of the eligible male population.[128] The Sydney Morning Herald referred to the outbreak of war as Australia's "Baptism of Fire."[129] 8,141 men[130] were killed in 8 months of fighting at Gallipoli, on the Turkish coast. After the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) was withdrawn in late 1915, and enlarged to five divisions, most were moved to France to serve under British command.

The AIF's first experience of warfare on the Western Front was also the most costly single encounter in Australian military history. In July 1916, at Fromelles, in a diversionary attack during the Battle of the Somme, the AIF suffered 5,533 killed or wounded in 24 hours.[131] Sixteen months later, the five Australian divisions became the Australian Corps, first under the command of General Birdwood, and later the Australian General Sir John Monash. Two bitterly fought and divisive conscription referendums were held in Australia in 1916 and 1917. Both failed, and Australia's army remained a volunteer force.

Monash's approach to the planning of military action was meticulous, and unusual for military thinkers of the time. His first operation at the relatively small Battle of Hamel demonstrated the validity of his approach and later actions before the Hindenburg Line in 1918 confirmed it. Monash wrote

The true role of infantry was not to expend itself upon heroic physical effort, not to wither away under merciless machine-gun fire, not to impale itself on hostile bayonets, but on the contrary, to advance under the maximum possible protection of the maximum possible array of mechanical resources...guns, machine-guns, tanks, mortars and aeroplanes...to be relieved as far as possible of the obligation to fight their way forward.[132]

Over 60,000 Australians had died during the conflict and 160,000 were wounded, a high proportion of the 330,000 who had fought overseas.[126] Australia's annual holiday to remember its war dead is held on ANZAC Day, 25 April, each year, the date of the first landings at Gallipoli in 1915. The choice of date is often mystifying to non-Australians; it was after all, an allied invasion that ended in military defeat. Bill Gammage has suggested that the choice of 25 April has always meant much to Australians because at Gallipoli, "the great machines of modern war were few enough to allow ordinary citizens to show what they could do." In France, between 1916 and 1918, "where almost seven times as many (Australians) died,...the guns showed cruelly, how little individuals mattered."[133]

Men, money and markets: the 1920s

In June 1920, the last Australian soldiers returned home, some eighteen months after the war's end.[134] Prime Minister William Morris Hughes led a new conservative force, the Nationalist Party, formed from the old Liberal party and breakaway elements of Labor (of which he was the most prominent), after the deep and bitter split over Conscription. An estimated 12,000 Australians died as a result of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1919, almost certainly brought home by returning soldiers.[135]

The success of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia posed a threat in the eyes of many Australians, although to a small group of socialists, it was an inspiration. The Communist Party of Australia was formed in 1920 and has remained active ever since, despite several splits, its banning in 1940-2 and a second attempt to ban it in 1951.[136] Other significant after-effects of the war included ongoing industrial unrest, which included the 1923 Victorian Police strike. "Why should there be the ludicrous and tragic situation of poverty in the midst of plenty, demanded the radicals."[137] Industrial disputes characterised the 1920s in Australia. Other major strikes occurred on the waterfront, in the coalmining and timber industries in the late 1920s. The union movement had established the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) in 1927 in response to the Nationalist government's efforts to change working conditions and reduce the power of the unions.

Jazz music, entertainment culture, new technology and consumerism that characterised the 1920s in the USA was, to some extent, also found in Australia. Prohibition did not succeed in Australia however, although anti-alcohol forces were successful in having hotels closed after 6 pm, and closed altogether in a few city suburbs.[138]

The fledgling film industry fared badly as the 1920s went on however, despite the fact that in the mid 1920s over 2 million Australians went to the movies each week in 1250 cinemas. A Royal Commission in 1927 failed to assist and the industry that had begun so brightly in 1906 with the release of The Story of the Kelly Gang, atrophied until its revival in the 1970s.[139][140]

Stanley Bruce became Australian Prime Minister in 1923, when members of the Nationalist Party Government voted to remove W.M. Hughes. Speaking at the Sydney Royal Agricultural Society in early 1925, Bruce summed up the priorities and optimism of many Australians when he spoke of the need for "men, money and markets."

The Argus newspaper reported:

Mr Bruce said… he was more than ever convinced that men, money and markets accurately defined the essential requirements of Australia… Negotiations (had been conducted) with the British Government for the provision of money…to carry out development works which would greatly increase Australia’s power to absorb migrants… A greater flow of British immigrants had occupied the attention of the British and Australian ministries since the end of the Great War.[141]

The migration campaign of the 1920s, operated by the Development and Migration Commission, brought almost 300,000 Britons to Australia by the end of the decade,[142] although schemes to settle migrants and returned soldiers "on the land" were generally not a success. "The new irrigation areas in Western Australia and the Dawson Valley of Queensland proved disastrous"[143]

Traditionally in Australia the costs of major investment have been met by state and Federal governments. Heavy borrowing from overseas was made by the governments in the 1920s, and a Loan Council set up in 1928 to coordinate loans, three quarters of which came from overseas.[144] Despite Imperial preference, a balance of trade was not successfully achieved with Britain. "In the five years from 1924..to..1928, Australia bought 43.4% of its imports from Britain and sold 38.7% of its exports. Wheat and wool made up more than two thirds of all Australian exports," a dangerous reliance on just two export commodities.[145]

The 1920s saw significant development in transport, including the final abandonment of the coastal sailing ship in favour of steam, and improvements in rail and motor transport heralded dramatic changes in work and leisure. In 1918 there were 50,000 cars and lorries in the whole of Australia. By 1929 there were 500,000.[146] The stage coach company Cobb and Co, established in 1853, ran its last coach in outback Queensland in 1924.[147] In 1920, the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Service (to become the Australian airline QANTAS) was established.[148]

The Country Party formed in 1920 and until the 1970s it promulgated its version of agrarianism, which it called "Countrymindedness". The goal was to enhance the status of the graziers (operators of big sheep ranches) and small farmers, and justify subsidies for them.[149]

The Depression decade: the 1930s

The Great Depression of the 1930s was an economic catastrophe that severely affected most nations of the world, and Australia was not immune. In fact, Australia, with its extreme dependence on exports, particularly primary products such as wool and wheat,[150] is thought to have been one of the hardest-hit countries in the Western world along with Canada and Germany.[citation needed]

Exposed by continuous borrowing to fund capital works in the 1920s, the Australian and state governments were "already far from secure in 1927, when most economic indicators took a turn for the worse. Australia's dependence of exports left her extraordinaily vulnerable to world market fluctuations," according to economic historian Geoff Spenceley.[151] Debt by the state of New South Wales accounted for almost half Australia’s accumulated debt by December 1927. The situation caused alarm amongst a few politicians and economists, notably Edward Shann of the University of Western Australia, but most political, union and business leaders were reluctant to admit anything was seriously wrong.[152] In 1926, Australian Finance magazine stated:

In the whole British Empire, there is no more voracious borrower than the Australian Commonwealth. Loan follows loan with disconserting frequency. It may be a loan to pay off maturing loans or a loan to pay the interest on existing loans, or a loan to repay temporary loans from the bankers...[153]

Thus, well before the Wall Street Crash of 29 October 1929, the Australian economy was already facing significant difficulties. As the economy slowed in 1927, so did manufacturing and the country slipped into recession as profits slumped and unemployment rose.[154] At elections held on 12 October 1929 the Labor Party was swept to power in a landslide, the former Prime Minister Stanley Bruce losing his own seat in the House of Representatives. The new Prime Minister James Scullin and his largely inexperienced Government were almost immediately faced with a series of crises. Hamstrung by their lack of control of the Senate, a lack of control over the Banking system and divisions within the Labor Party over how best to deal with the situation, the government was forced to accept solutions that eventually split the party, as it had in 1917.

Various "plans" to resolve the crisis were suggested; Sir Otto Niemeyer, a representative of the English banks who visited in mid 1930, proposed a deflationary plan, involving cuts to government spending and wages. Treasurer Ted Theodore proposed a mildly inflationary plan, while the Labor Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang proposed a radical plan which repudiated overseas debt.[155] The "Premier's Plan" finally accepted by federal and state governments in June 1931, followed the deflationary model advocated by Niemeyer and included a reduction of 20% in government spending, a reduction in bank interest rates and an increase in taxation.[156] Niemeyer famously told the Australian leaders of government;

There is evidence...that the standard of living in Australia has reached a point which is economically beyond the capacity of the country to bear.[157]

There is debate today over the extent of unemployment in Australia, which is often cited as peaking at 29% in 1932. "Trade Union figures are the most often quoted, but the people who were there…regard the figures as wildly understating the extent of unemployment" wrote historian Wendy Lowenstein in her collection of oral histories of the Depression.[158] However, David Potts argues that "over the last thirty years …historians of the period have either uncritically accepted that figure (29% in the peak year 1932) including rounding it up to ‘a third,’ or they have passionately argued that a third is far too low."[159] Potts suggests a peak national figure of 25% unemployed.[160]

However, there seems little doubt that there was great variation in levels of unemployment. For example, statistics collected by historian Peter Spearritt show 17.8% of men and 7.9% of women unemployed in 1933 in the comfortable Sydney suburb of Woollahra. In the working class suburb of Paddington, 41.3% of men and 20.7% of women were listed as unemployed.[161] Geoffrey Spenceley argues that apart from variation between men and women, unemployment was also much higher in some industries, such as the building and construction industry, and comparatively low in the public administrative and professional sectors.[162] In the bush, worst hit were small farmers in the wheat belts as far afield as north-east Victoria and Western Australia, who saw more and more of their income absorbed by interest payments.[163]

In May 1931, a new conservative political force, the United Australia Party was formed by breakaway members of the Labor Party combining with the Nationalist Party. At Federal elections in December 1931, the United Australia Party, led by former Labor member Joseph Lyons, easily won office. They remained in power until September 1940. The Lyons government has often been credited with steering recovery from the depression, although just how much of this was owed to their policies remains contentious.[164] Stuart Macintyre also points out that although Australian GDP grew from £386.9 million to £485.9 million between 1931-2 and 1938-9, real domestic product per head of population was still "but a few shillings greater in 1938-39 (£70.12), than it had been in 1920-21 (£70.04).[165]

The Second World War

Defence policy in the 30s

Until the late 1930s, defence was not a significant issue for Australians. At the 1937 elections, both political parties advocated increased defence spending, in the context of increased Japanese aggression in China and Germany’s aggression in Europe. There was a difference in opinion over how the defence spending should be allocated however. The UAP government emphasised cooperation with Britain in "a policy of imperial defence." The lynchpin of this was the British naval base at Singapore and the Royal Navy battle fleet "which, it was hoped, would use it in time of need."[166] Defence spending in the inter-war years reflected this priority. In the period 1921-1936 totalled £40 million on the RAN, £20 million on the Australian Army and £6 million on the RAAF (established in 1921, the "youngest" of the three services). In 1939, the Navy, which included two heavy cruisers and four light cruisers, was the service best equipped for war.[167]

Gavin Long argues that the Labor opposition urged greater national self-reliance through a build up of manufacturing and more emphasis on the Army and RAAF, as Chief of the General Staff, John Lavarack also advocated.[168] In November 1936, Labor leader John Curtin said "The dependence of Australia upon the competence, let alone the readiness, of British statesmen to send forces to our aid is too dangerous a hazard upon which to found Australia’s defence policy.".[169] According to John Robertson, "some British leaders had also realised that their country could not fight Japan and Germany at the same time." But "this was never discussed candidly at…meeting(s) of Australian and British defence planners", such as the 1937 Imperial Conference.[170]

By September 1939 the Australian Army numbered 3,000 regulars. A recruiting campaign in late 1938, led by Major-General Thomas Blamey increased the reserve militia to almost 80,000.[171] The first division raised for war was designated the 6th Division, of the 2nd AIF, there being 5 Militia Divisions on paper and a 1st AIF in the First World War.[172]

The War

On Sunday 3 September 1939, Prime Minister Robert Menzies made a national radio broadcast:

My fellow Australians. It is my melancholy duty to inform you, officially, that, in consequence of the persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.[173]

In this statement, Menzies, who had been Prime Minister and leader of the UAP since Lyon's death in 1939, reflected a widely held Australian "detestation of Germany's aggression and a conviction that Britain, France and the Commonwealth countries were involved in a just war."[174]

Some writers emphasise how extraordinarily varied combat experience was to be for soldiers from Australia; "more varied, geographically than that of (some of) the great powers, Russia, China and Japan…The war could mean young men at Rabaul taking off in Wirraways to meet certain death from more numerous Zeros. It could mean an infantryman on a jungle patrol behind Japanese lines, or facing German tanks on the Tobruk perimeter. It was men of the Perth fighting until their ammunition was exhausted…or a young man, not long out of school, flying a Lancaster on his first mission over Germany."[175]

In 1940-41, Australian forces played prominent roles in the fighting in the Mediterranean theatre, including Operation Compass, the Siege of Tobruk, the Greek campaign, the Battle of Crete, the Syria-Lebanon campaign and the Second Battle of El Alamein. The war came closer to home when HMAS Sydney was lost with all hands in battle with the German raider Kormoran in November 1941.

After the attacks on Pearl Harbor and on Allied states throughout East Asia and the Pacific, from 8 December (Australian time) 1941, Prime Minister John Curtin insisted that Australian forces be brought home to fight Japan. After the Fall of Singapore in February 1942, 15,000 Australian soldiers became prisoners of war. A few days later, Darwin was heavily bombed by Japanese planes, the first time the Australian mainland had ever been attacked by enemy forces. Over the following 19 months, Australia was attacked from the air almost 100 times. The shock of Britain's defeat in Asia in 1942 and the threat of Japanese invasion caused Australia to turn to the United States as a new ally. On 27 December 1941 Curtin wrote a New Year's message for an Australian newspaper, which included the famous lines:

"The Australian Government...regards the Pacific struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must have the fullest say in the direction of the democracies' fighting plan. Without inhibitions of any kind, I make it clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom."[176]

At a press conference the following day Curtin qualified the message as not meaning a "weakening of Australia's ties with the British Empire."[177] However, Curtin's Labor government forged a close alliance with the United States, and a fundamental shift in Australia's foreign policy began. General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Allied Commander in the South West Pacific Area, moved his headquarters to Australia in March 1942. In late May 1942, Japanese midget submarines sank an accommodation vessel in a daring raid on Sydney Harbour. On 8 June 1942, two Japanese submarines briefly shelled Sydney's eastern suburbs and the city of Newcastle.[178]

Despite Prime Minister Curtin's statement, Australia was never really considered a military object by the Japanese. The Japanese intention was to blockade and use psychological pressure to force Australia into a neutral position.[179][180] Hideki Tojo claimed; "We never had enough troops to [invade Australia]. We had already far out-stretched our lines of communication. We did not have the armed strength or the supply facilities to mount such a terrific extension of our already over-strained and too thinly spread forces."[179] According to Dr Peter Stanley of the Centre for Historical Research at the National Museum of Australia, "no historian of standing believes the Japanese had a plan to invade Australia, there is not a skerrick of evidence."[181]

Between July and November 1942, Australian forces repulsed Japanese attempts on Port Moresby, by way of the Kokoda Track, in the highlands of New Guinea. The Battle of Milne Bay in August 1942 was the first Allied defeat of Japanese land forces. However, the Battle of Buna-Gona between November 1942 and January 1943, set the tone for the bitter final stages of the New Guinea campaign, which persisted into 1945. It was followed by Australian-led amphibious assaults against Japanese bases in Borneo.

Australia during the war

Historian Geoffrey Bolton argues the Australian economy was markedly affected by World War II.[182] In economic terms - expenditure on war reached 37% of GDP by 1943-4, compared to 4% expenditure in 1939-1940.[183] Total war expenditure was £2,949 million between 1939 and 1945.[184] Of Australia’s wartime population of 7 million, almost 1 million men and women served in a branch of the services at some stage of the six years of warfare. By war’s end, gross enlistments totalled 727,200 men and women in the Australian Army (of whom 557,800 served overseas), 216,900 in the RAAF and 48,900 in the RAN. Over 39,700 were killed or died as prisoners of war, about 8,000 of whom died as prisoners of the Japanese.[185]

Although the peak of Army enlistments occurred in June–July 1940, when over 70,000 enlisted, it was the Curtin Labor Government, formed in October 1941, that was largely responsible for "a complete revision of the whole Australian economic, domestic and industrial life."[186] Rationing of fuel, clothing and some food was introduced, (although less severely than in Britain) Christmas holidays curtailed, "brown outs" introduced and some public transport reduced. From December 1941, the Government evacuated all women and children from Darwin and northern Australia, and over 10,000 refugees arrived from South East Asia as Japan advanced.[187] In January 1942, the Manpower Directorate was set up "to ensure the organisation of Australians in the best possible way to meet all defence requirements."[186] Minister for War Organisation of Industry, John Dedman introduced a degree of austerity and government control previously unknown, to such an extent that he was nicknamed "the man who killed Father Christmas."

In May 1942 uniform tax laws were introduced in Australia, as state governments relinquished their control over income taxation. "The significance of this decision was greater than any other… made throughout the war, as it added extensive powers to the Federal Government and greatly reduced the financial autonomy of the states."[188] In the post war world, federal power would grow significantly as a result of this change.