Refugee: Difference between revisions

| (13 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{other uses}} |

{{other uses}} |

||

[[File:Kibativillagers.jpg|thumb|250px|Villagers fleeing the village of Kibati during the [[2008 Nord-Kivu campaign|2008 Nord-Kivu conflict]] in the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]].]] |

[[File:Kibativillagers.jpg|thumb|250px|Villagers fleeing the village of Kibati during the [[2008 Nord-Kivu campaign|2008 Nord-Kivu conflict]] in the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]].]] |

||

A '''refugee''' is a person who is outside their home country because they have suffered (or feared) persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or because they are a member of a persecuted '[[social group]]' or because they are fleeing a war. Such a person may be called an ''''asylum seeker'''' until recognized by the state where they make a claim.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/161121|title=refugee, n.|work=[[Oxford English Dictionary Online]]|date=November 2010|accessdate=23 February 2011}}</ref> |

A '''refugee''' is a person who is outside their home country because they have suffered (or feared) persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or because they are a member of a persecuted '[[social group]]' or because they are fleeing a war. Such a person may be called an ''''asylum seeker'''{{'}} until recognized by the state where they make a claim.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/161121|title=refugee, n.|work=[[Oxford English Dictionary Online]]|date=November 2010|accessdate=23 February 2011}}</ref> |

||

Although similar and frequently confused with refugees, [[internally displaced person]]s have a different legal definition and are essentially refugees who have not crossed any international border. At the end of 2012, the [[United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees|Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees]] (UNHCR), the [[United Nations]]' refugee agency, reported that there were 15.4 million refugees worldwide.<ref name="unhcr.org.uk">http://www.unhcr.org.uk/about-us/key-facts-and-figures.html, UNHCR, Facts and Figures about Refugees</ref> By contrast there were 28.8 million (about twice as many) IDPs at the end of 2012<ref>"About two-thirds of the world's forcibly uprooted people are displaced within their own country.", http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49c3646c23.html</ref> |

Although similar and frequently confused with refugees, [[internally displaced person]]s have a different legal definition and are essentially refugees who have not crossed any international border. At the end of 2012, the [[United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees|Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees]] (UNHCR), the [[United Nations]]' refugee agency, reported that there were 15.4 million refugees worldwide.<ref name="unhcr.org.uk">http://www.unhcr.org.uk/about-us/key-facts-and-figures.html, UNHCR, Facts and Figures about Refugees</ref> By contrast there were 28.8 million (about twice as many) IDPs at the end of 2012<ref>"About two-thirds of the world's forcibly uprooted people are displaced within their own country.", http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49c3646c23.html</ref> |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

[[File:Turkish refugees from Edirne.jpg|thumb|left|Turkish refugees from Edirne, 1913]] |

[[File:Turkish refugees from Edirne.jpg|thumb|left|Turkish refugees from Edirne, 1913]] |

||

The term 'refugee' is sometimes applied to people who may have fit the definition outlined by the 1951 Convention, were it to be applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the [[Edict of Fontainebleau]] in 1685 outlawed [[Protestantism]] in France, hundreds of thousands of [[Huguenot]]s fled to England, the [[Netherlands]], [[Switzerland]], [[South Africa]], Germany and [[Prussia]]. The repeated waves of [[pogrom]]s that swept Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th century prompted mass Jewish emigration (more than 2 million [[History of the Jews in Russia and the Soviet Union|Russian Jews]] emigrated in the period 1881–1920). From the 19th century, a large portion of the Muslim peoples (termed '[[Muhajir (Turkey)|Muhacir]]' under a general definition) of the [[ |

The term 'refugee' is sometimes applied to people who may have fit the definition outlined by the 1951 Convention, were it to be applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the [[Edict of Fontainebleau]] in 1685 outlawed [[Protestantism]] in France, hundreds of thousands of [[Huguenot]]s fled to England, the [[Netherlands]], [[Switzerland]], [[South Africa]], Germany and [[Prussia]]. The repeated waves of [[pogrom]]s that swept Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th century prompted mass Jewish emigration (more than 2 million [[History of the Jews in Russia and the Soviet Union|Russian Jews]] emigrated in the period 1881–1920). From the 19th century, a large portion of the Muslim peoples (termed '[[Muhajir (Turkey)|Muhacir]]' under a general definition) of the [[Southeastern Europe]], [[Caucasus]], [[Crimea]] and [[Crete]]<ref>By the early 19th century, as many as 45% of the islanders may have been Muslim.</ref> took refuge in present-day [[Turkey]] and shaped that country's fundamental features.<ref>Justin McCarthy, ''Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922'', (Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, c1995</ref> The [[Balkan Wars]] of 1912–1913 caused 800,000 people to leave their homes.<ref>[http://tulp.leidenuniv.nl/content_docs/wap/ejz18.pdf Greek and Turkish refugees and deportees 1912-1924]. Universiteit Leiden.</ref> Various groups of people were officially designated refugees beginning in [[World War I]]. |

||

===League of Nations=== |

===League of Nations=== |

||

| Line 443: | Line 443: | ||

{{Main|Environmental migrant}} |

{{Main|Environmental migrant}} |

||

[[File:Natural disasters caused by climate change.png|thumb|right|200px|Map showing where natural disasters caused/aggravated by climate change can occur, and where possibly environmental refugees would be created]] |

[[File:Natural disasters caused by climate change.png|thumb|right|200px|Map showing where natural disasters caused/aggravated by climate change can occur, and where possibly environmental refugees would be created]] |

||

Although they do not fit the definition of refugees set out in the UN Convention, people displaced by the effects of [[climate change]] have often been termed "climate refugees"<ref name="Kirby">{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/613075.stm|title=West warned on climate refugees |last=Kirby|first=Alex|date=2000-01-24|publisher=BBC News|accessdate=2009-07-17}}</ref> or "climate change refugees".<ref name="Strange">{{cite news|url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/environment/article4159923.ece|title=UN warns of growth in climate change refugees|last=Strange|first=Hannah|date=2008-06-17|work=The Times|accessdate=2009-07-17 | location=London}}</ref> The term 'environmental refugee' is also commonly used and an estimate 25 million people can currently be classified as such.<ref name="BBC News">{{cite news|title=Climate mass migration fears 'unfounded'|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-12360864|publisher=BBC News | date=2011-02-04}}</ref> The alarming predictions by the UN, charities and some environmentalists, that between 200 million and 1 billion people could flood across international borders to escape the impacts of climate change in the next 40 years are |

Although they do not fit the definition of refugees set out in the UN Convention, people displaced by the effects of [[climate change]] have often been termed "climate refugees"<ref name="Kirby">{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/613075.stm|title=West warned on climate refugees |last=Kirby|first=Alex|date=2000-01-24|publisher=BBC News|accessdate=2009-07-17}}</ref> or "climate change refugees".<ref name="Strange">{{cite news|url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/environment/article4159923.ece|title=UN warns of growth in climate change refugees|last=Strange|first=Hannah|date=2008-06-17|work=The Times|accessdate=2009-07-17 | location=London}}</ref> The term 'environmental refugee' is also commonly used and an estimate 25 million people can currently be classified as such.<ref name="BBC News">{{cite news|title=Climate mass migration fears 'unfounded'|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-12360864|publisher=BBC News | date=2011-02-04}}</ref> The alarming predictions by the UN, charities and some environmentalists, that between 200 million and 1 billion people could flood across international borders to escape the impacts of climate change in the next 40 years are realistic.<ref>{{cite news|title=Security and the environment Climate wars Does a warming world really mean that more conflict is inevitable?|url=http://www.economist.com/node/16539538|publisher=Economist | date=2010-07-08}}</ref> Case studies from Bolivia, Senegal and Tanzania, three countries extremely prone to climate change, show that people affected by environmental degradation rarely move across borders. Instead, they adapt to new circumstances by moving short distances for short periods, often to cities.<ref>{{cite book|last=Tacoli|first=Cecila|title=Not only climate change: mobility, vulnerability and socio-economic transformations in environmentally fragile areas in Bolivia, Senegal and Tanzania|year=2011|publisher=International Institute for Environment and Development|location=London|isbn=978-1-84369-808-1|pages=40|url=http://pubs.iied.org/10590IIED.html}}</ref> Millions of people live in places that are vulnerable to the effects of climate change. They face extreme weather conditions such as droughts or floods. Their lives and livelihoods might be threatened in new ways and create new vulnerabilities.<ref>Bogumil Terminski, ''Environmentally-Induced Displacement. Theoretical Frameworks and Current Challenges'', Universite de Liege, 2012</ref> Migration is in many developing countries a coping strategy to mitigate poverty and is already happening independent of the effects of climate change and environmental degradation. It is a selective process and the poorest and most vulnerable people are often excluded as they will find it almost impossible to move due to a lack of necessary funds or social support.<ref name="BBC News"/> |

||

===Security threats=== |

===Security threats=== |

||

| Line 757: | Line 757: | ||

====France==== |

====France==== |

||

In 2010, President [[Nicholas Sarkozy|Nicolas Sarkozy]] began the systematic dismantling of illegal [[Romani people|Romani]] camps and squats in France, deporting thousands of Roma residing in France illegally to [[ |

In 2010, President [[Nicholas Sarkozy|Nicolas Sarkozy]] began the systematic dismantling of illegal [[Romani people|Romani]] camps and squats in France, deporting thousands of Roma residing in France illegally to [[Romania]], [[Bulgaria]] or elsewhere.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-11027288 | work=BBC News | title=Q&A: France Roma expulsions | date=2010-10-19}}</ref> |

||

====Hungary==== |

====Hungary==== |

||

| Line 765: | Line 765: | ||

The [[Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia]] in 1968 was followed by a wave of emigration, unseen before and stopped shortly after (estimate: 70,000 immediately, 300,000 in total),<ref>[http://www.britskelisty.cz/9808/19980821h.html "Day when tanks destroyed Czech dreams of Prague Spring" (''Den, kdy tanky zlikvidovaly české sny Pražského jara'') at Britské Listy (British Letters)]</ref> typic |

The [[Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia]] in 1968 was followed by a wave of emigration, unseen before and stopped shortly after (estimate: 70,000 immediately, 300,000 in total),<ref>[http://www.britskelisty.cz/9808/19980821h.html "Day when tanks destroyed Czech dreams of Prague Spring" (''Den, kdy tanky zlikvidovaly české sny Pražského jara'') at Britské Listy (British Letters)]</ref> typic |

||

==== |

====Southeastern Europe==== |

||

Following the [[Greek Civil War]] (1946–1949) hundreds of thousands of Greeks and Ethnic Macedonians were expelled or fled the country. The number of refugees ranged from 35,000 to over 213,000. Over 28,000 children were evacuated by the Partisans to the Eastern Bloc and the [[Socialist Republic of Macedonia]]. This left thousands of [[Greeks]] and [[Aegean Macedonians]] spread across the world. |

Following the [[Greek Civil War]] (1946–1949) hundreds of thousands of Greeks and Ethnic Macedonians were expelled or fled the country. The number of refugees ranged from 35,000 to over 213,000. Over 28,000 children were evacuated by the Partisans to the [[Eastern Bloc]] and the [[Socialist Republic of Macedonia]]. This left thousands of [[Greeks]] and [[Aegean Macedonians]] spread across the world. |

||

The [[forced assimilation]] campaign of the late 1980s directed against ethnic [[Turkish people|Turks]] resulted in the emigration of some 300,000 [[Turks in Bulgaria|Bulgarian Turks]] to Turkey. |

The [[forced assimilation]] campaign of the late 1980s directed against ethnic [[Turkish people|Turks]] resulted in the emigration of some 300,000 [[Turks in Bulgaria|Bulgarian Turks]] to Turkey. |

||

[[File:Evstafiev-travnik-refugees.jpg|thumb|Refugees arrive in [[Travnik]], central [[Bosnia and Herzegovina|Bosnia]], during the [[Yugoslav wars]], 1993.]] |

[[File:Evstafiev-travnik-refugees.jpg|thumb|Refugees arrive in [[Travnik]], central [[Bosnia and Herzegovina|Bosnia]], during the [[Yugoslav wars]], 1993.]] |

||

Beginning in 1991, political upheavals in |

Beginning in 1991, political upheavals in [[Southeastern Europe]] such as the breakup of [[Yugoslavia]], displaced about 2,700,000 people by mid-1992, of which over 700,000 of them sought asylum in [[European Union member states]].<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/specials/bosnia/context/dayton.html Bosnia: Dayton Accords]</ref><ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C07E3D61339F937A15752C1A963958260&n=Top/Reference/Times%20Topics/Subjects/I/Immigration%20and%20Refugees Resettling Refugees: U.N. Facing New Burden]</ref> In 1999, about one million [[Albanians]] escaped from Serbian persecution. |

||

Today there are still thousands of refugees and internally [[displaced person]]s in |

Today there are still thousands of refugees and internally [[displaced person]]s in Southeastern Europe who cannot return to their homes. Most of them are [[Serbs]] who cannot return to [[Kosovo]], and who still live in refugee camps in Serbia today. Over 200,000 Serbs and other non-Albanian minorities fled or were expelled from Kosovo after the [[Kosovo War]] in 1999.<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/serbia/article/0,,1713498,00.html Serbia threatens to resist Kosovo independence plan]</ref><ref>[http://hrw.org/english/docs/2004/03/18/serbia8129.htm Kosovo/Serbia: Protect Minorities from Ethnic Violence (Human Rights Watch)]</ref> |

||

Refugees and IDPs in [[Serbia]] form between 7% and 7.5% of its population – about half a million refugees sought refuge in the country following the series of [[Yugoslav wars]] (from Croatia mainly, to an extent [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] too and the IDPs from [[Kosovo]], which are the most numerous at over 200,000).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rb.html |title=Serbia |accessdate= |author=The World Factbook |authorlink=The World Factbook |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency }}</ref> Serbia has the largest refugee population in Europe.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.b92.net/eng/news/society-article.php?yyyy=2007&mm=10&dd=22&nav_id=44785 |title=Serbia's refugee population largest in Europe |accessdate= |author=Tanjug |authorlink=Tanjug |date=22 October 2007 |publisher=B92 }}</ref> |

Refugees and IDPs in [[Serbia]] form between 7% and 7.5% of its population – about half a million refugees sought refuge in the country following the series of [[Yugoslav wars]] (from Croatia mainly, to an extent [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] too and the IDPs from [[Kosovo]], which are the most numerous at over 200,000).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rb.html |title=Serbia |accessdate= |author=The World Factbook |authorlink=The World Factbook |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency }}</ref> Serbia has the largest refugee population in Europe.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.b92.net/eng/news/society-article.php?yyyy=2007&mm=10&dd=22&nav_id=44785 |title=Serbia's refugee population largest in Europe |accessdate= |author=Tanjug |authorlink=Tanjug |date=22 October 2007 |publisher=B92 }}</ref> |

||

| Line 784: | Line 784: | ||

====Georgia==== |

====Georgia==== |

||

More than |

More than 8,0050,000 people, mostly [[Georgians]] but some others too, were the victims of forcible displacement and [[Ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia|ethnic-cleansing]] from [[Abkhazia]] during the [[War in Abkhazia (1992–1993)|War in Abkhazia]] between 1992 and 1993, and afterwards in 1993 and 1998.<ref>Bookman, Milica Zarkovic, "The Demographic Struggle for Power", (p. 131), Frank Cass and Co. Ltd. (UK), (1997) ISBN 0-7146-4732-2</ref> |

||

As a result of [[1991–1992 South Ossetia War]], about 100,000 ethnic [[Ossetians]] fled South Ossetia and Georgia proper, most across the border into North Ossetia. A further 23,000 ethnic [[Georgians]] fled South Ossetia and settled in other parts of [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]].<ref>Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, [http://hrw.org/reports/1996/Russia.htm Russia. The Ingush-Ossetian conflict in the Prigorodnyi region], May 1996.</ref> |

As a result of [[1991–1992 South Ossetia War]], about 100,000 ethnic [[Ossetians]] fled South Ossetia and Georgia proper, most across the border into North Ossetia. A further 23,000 ethnic [[Georgians]] fled South Ossetia and settled in other parts of [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]].<ref>Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, [http://hrw.org/reports/1996/Russia.htm Russia. The Ingush-Ossetian conflict in the Prigorodnyi region], May 1996.</ref> |

||

| Line 796: | Line 796: | ||

===Movements in the Middle East=== |

===Movements in the Middle East=== |

||

==== |

====Assyrians transfers and forced migrations between 1843 and the 21st century==== |

||

In his recent PhD thesis<ref>[[Mordechai Zaken]]", [[Tribal chieftains and their Jewish Subjects: A comparative Study in Survival]]: PhD Thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2004.</ref> and in his recent book<ref>[[Mordechai Zaken]]", [[Jewish Subjects and their tribal chieftains in Kurdistan]]: A Study in Survival", Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2007.</ref> the Israeli scholar Mordechai Zaken discussed the history of the |

In his recent PhD thesis<ref>[[Mordechai Zaken]]", [[Tribal chieftains and their Jewish Subjects: A comparative Study in Survival]]: PhD Thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2004.</ref> and in his recent book<ref>[[Mordechai Zaken]]", [[Jewish Subjects and their tribal chieftains in Kurdistan]]: A Study in Survival", Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2007.</ref> the Israeli scholar Mordechai Zaken discussed the history of the Assyrians of Turkey and Iraq (in the Kurdish vicinity) during the last 180 years, from 1843 onwards. In his studies Zaken outlines three major eruptions that took place between 1843 and 1933 during which the Assyrians lost their land and hegemony in their habitat in the Hakkārī (or Julamerk) region in southeastern Turkey and became refugees in other lands, notably Iran and Iraq, and ultimately in exiled communities in Western countries (United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and [[EU member states]] like Sweden, France, to mention some of these countries). Mordechai Zaken wrote this important study from an analytical and comparative point of view, comparing the Assyrians experience with the experience of the Kurdish Jews, who had been dwelling in Kurdistan for two thousands years or so, but were forced to migrate the land to Israel in the early 1950s. The Jews of Kurdistan were forced to leave and migrate as a result of the Arab-Israeli war, as a result of the increasing hostility and acts of violence against Jews in Iraq and Kurdish towns and villages, and as a result of a new situation that had been built up during the 1940s in Iraq and Kurdistan in which the ability of Jews to live in relative comfort and relative tolerance (that was erupted from time to time prior to that period) with their Arab and Muslim neighbors, as they did for many years, practically came to an end. At the end, the Jews of Kurdistan had to leave their Kurdish habitat en masse and migrate into Israel. The Assyrians on the other hand, came to similar conclusion but migrated in stages following each and every eruption of a political crisis with the regime in which boundaries they lived or following each conflict with their Muslim, Turkish, Arabs or Kurdish neighbors, or following the departure or expulsion of their patriarch Mar Shimon in 1933, first to Cyprus and then to the United States. Consequently, indeed there is still a small and fragile community of Assyrians in Iraq, however, millions of Assyrians live today in exiled and prosperous communities in the west.<ref>Joyce Blau, one of the world's leading scholars in the Kurdish culture, languages and history, suggested that "This part of Mr. Zaken’s thesis, concerning Jewish life in Iraqi Kurdistan, "well complements the impressive work of the pioneer ethnologist Erich Brauer." Brauer was indeed one of the most skilled ethnographs of the first half of the 20th century and wrote an important book on the Jews of Kurdistan [Erich Brauer, The Jews of Kurdistan, First edition 1940, revised edition 1993, completed and edited par Raphael Patai, Wayne State University Press, Detroit])</ref> |

||

====Arab-Israeli wars 1947-1973==== |

====Arab-Israeli wars 1947-1973==== |

||

| Line 844: | Line 844: | ||

| publisher = [[BBC News Online]] |

| publisher = [[BBC News Online]] |

||

|date=2006-08-31 |

|date=2006-08-31 |

||

| accessdate = 2008-07-13}}</ref> Lebanese desire to emigrate has increased since the war. Over a fifth of [[Shia]]s, a quarter of [[Sunni]]s, and nearly half of [[Maronite]]s have expressed the desire to leave Lebanon. Nearly a third of such Maronites have already submitted visa applications to foreign embassies, and another 60,000 Christians have already fled, as of April 2007. Lebanese Christians are concerned that their influence is waning, fear the apparent rise of [[radical Islam]], and worry of potential Sunni-Shia rivalry.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2007/04/01/wleb01.xml|title=Rise in radical Islam last straw for Lebanon's Christians|author=Michael Hirst|publisher=[[Daily Telegraph]]|date=2007-04-03| location=London}}</ref> |

| accessdate = 2008-07-13}}</ref> Lebanese desire to emigrate has increased since the war. Over a fifth of [[Shia Islam in Lebanon|Shia]]s, a quarter of [[Sunni Islam in Lebanon|Sunni]]s, and nearly half of [[Maronite Christianity in Lebanon|Maronite]]s have expressed the desire to leave Lebanon. Nearly a third of such Maronites have already submitted visa applications to foreign embassies, and another 60,000 Lebanese Christians have already fled, as of April 2007. Lebanese Christians are concerned that their influence is waning, fear the apparent rise of [[radical Islam]], and worry of potential Sunni-Shia rivalry.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2007/04/01/wleb01.xml|title=Rise in radical Islam last straw for Lebanon's Christians|author=Michael Hirst|publisher=[[Daily Telegraph]]|date=2007-04-03| location=London}}</ref> |

||

====Kurdish population displacement due to Turkish conflict==== |

====Kurdish population displacement due to Turkish conflict==== |

||

Revision as of 10:06, 2 June 2014

A refugee is a person who is outside their home country because they have suffered (or feared) persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or because they are a member of a persecuted 'social group' or because they are fleeing a war. Such a person may be called an 'asylum seeker' until recognized by the state where they make a claim.[1]

Although similar and frequently confused with refugees, internally displaced persons have a different legal definition and are essentially refugees who have not crossed any international border. At the end of 2012, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations' refugee agency, reported that there were 15.4 million refugees worldwide.[2] By contrast there were 28.8 million (about twice as many) IDPs at the end of 2012[3]

In 2012 Afghanistan was the biggest source country of refugees (a position it has held for 32 years) with one out of every four refugees in the world being an Afghan and 95% of them living in Pakistan and Iran.[2]

Definition

The 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees has adopted the following definition of a refugee (in Article 1.A.2):

[A]ny person who: owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country".[4]

The concept of a refugee was expanded by the Convention's 1967 Protocol and by regional conventions in Africa and Latin America to include persons who had fled war or other violence in their home country. European Union's minimum standards definition of refugee, underlined by Art. 2 (c) of Directive No. 2004/83/EC, essentially reproduces the narrow definition of refugee offered by the UN 1951 Convention; nevertheless, by virtue of articles 2 (e) and 15 of the same Directive, persons who have fled a war-caused generalized violence are, at certain conditions, elegible for a complementary form of protection, called subsidiary protection. The same form of protection is foreseen for people who, without being refugees, are nevertheless exposed, if returned to their countries of origin, to death penalty, torture or other inhuman or degrading treatments.

The term refugee is often used to include displaced persons who may fall outside the legal definition in the Convention,[5] either because they have left their home countries because of war and not because of a fear of persecution, or because they have been forced to migrate within their home countries.[6] The Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, adopted by the Organization of African Unity in 1969, accepted the definition of the 1951 Refugee Convention and expanded it to include people who left their countries of origin not only because of persecution but also due to acts of external aggression, occupation, domination by foreign powers or serious disturbances of public order.[6]

Refugees were defined as a legal group in response to the large numbers of people fleeing Eastern Europe following World War II. The lead international agency coordinating refugee protection is the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which counted 8,400,000 refugees worldwide at the beginning of 2006. This was the lowest number since 1980.[7] The major exception is the 4,600,000 Palestinian refugees under the authority of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).[8] In June 2011 the UNHCR estimated the number of refugees to 15.1 million.[9] The majority of refugees who leave their country seek asylum in countries neighboring their country of nationality. The "durable solutions" to refugee populations, as defined by UNHCR and governments, are: voluntary repatriation to the country of origin; local integration into the country of asylum; and resettlement to a third country.[10]

History

The idea that a person who sought sanctuary in a holy place couldn't be harmed without inviting divine retribution was familiar to the ancient Greeks and ancient Egyptians. However, the right to seek asylum in a church or other holy place was first codified in law by King Æthelberht of Kent in about 600 AD. Similar laws were implemented throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. The related concept of political exile also has a long history: Ovid was sent to Tomis; Voltaire was sent to England. Through the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, nations recognized each other's sovereignty. However, it was not until the advent of romantic nationalism in late 18th-century Europe that nationalism gained sufficient prevalence for the phrase 'country of nationality' to become practically meaningful, and for people crossing borders to be required to provide identification.

The term 'refugee' is sometimes applied to people who may have fit the definition outlined by the 1951 Convention, were it to be applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 outlawed Protestantism in France, hundreds of thousands of Huguenots fled to England, the Netherlands, Switzerland, South Africa, Germany and Prussia. The repeated waves of pogroms that swept Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th century prompted mass Jewish emigration (more than 2 million Russian Jews emigrated in the period 1881–1920). From the 19th century, a large portion of the Muslim peoples (termed 'Muhacir' under a general definition) of the Southeastern Europe, Caucasus, Crimea and Crete[11] took refuge in present-day Turkey and shaped that country's fundamental features.[12] The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 caused 800,000 people to leave their homes.[13] Various groups of people were officially designated refugees beginning in World War I.

League of Nations

The first international co-ordination of refugee affairs came with the creation by the League of Nations in 1921 of High Commissioner for Refugees and the appointment of Fridtjof Nansen as its head. Nansen and the Commission were charged with assisting the approximately 1,500,000 people who fled the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent civil war (1917–1921),[14] most of them aristocrats fleeing the Communist government. It is estimated that about 800,000 Russian refugees became stateless when Lenin revoked citizenship for all Russian expatriates in 1921.[15]

In 1923, the mandate of the Commission was expanded to include the more than one million Armenians who left Turkish Asia Minor in 1915 and 1923 due to a series of events now known as the Armenian Genocide. Over the next several years, the mandate was expanded further to cover Assyrians and Turkish refugees.[16] In all of these cases, a refugee was defined as a person in a group for which the League of Nations had approved a mandate, as opposed to a person to whom a general definition applied.[citation needed]

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey involved approximately two million people (around 1.5 million Anatolian Greeks and 500,000 Muslims in Greece) most forcibly repatriated and denaturalized from homelands of centuries or millennia (and guaranteed the nationality of the destination country) in a treaty promoted and overseen by the international community as part of the Treaty of Lausanne.[17]

The U.S. Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. The Immigration Act of 1924 was aimed at further restricting the Southern and Eastern Europeans, especially Jews, Italians and Slavs, who had begun to enter the country in large numbers beginning in the 1890s.[18] Most of the European refugees (principally Jews and Slavs) fleeing Stalin, the Nazis and World War II were barred from coming to the United States.[19]

In 1930, the Nansen International Office for Refugees was established as a successor agency to the Commission. Its most notable achievement was the Nansen passport, a refugee travel document, for which it was awarded the 1938 Nobel Peace Prize. The Nansen Office was plagued by problems of financing, an increase in refugee numbers, and a lack of co-operation from some member states, which led to mixed success overall.

However, it managed to lead fourteen nations to ratify the 1933 Refugee Convention, an early, and relatively modest, attempt at a human rights charter, and in general assisted around one million refugees worldwide.[20]

1933 (rise of Nazism) to 1944

The rise of Nazism led to such a very large increase in the number of refugees from Germany that in 1933 the League created a High Commission for Refugees Coming from Germany. Besides other measures by the Nazis which created fear and flight, Jews were stripped of German citizenship[21] by the Reich Citizenship Law of 1935.[22] On July 4, 1936 an agreement was signed under League auspices that defined a refugee coming from Germany as "any person who was settled in that country, who does not possess any nationality other than German nationality, and in respect of whom it is established that in law or in fact he or she does not enjoy the protection of the Government of the Reich" (article 1).[23]

The mandate of the High Commission was subsequently expanded to include persons from Austria and Sudetenland, which Germany annexed after October 1, 1938 in accordance with the Munich Agreement. According to the Institute for Refugee Assistance, the actual count of refugees from Czechoslovakia on March 1, 1939 stood at almost 150,000.[24] Between 1933 and 1939, about 200,000 Jews fleeing Nazism were able to find refuge in France,[25] while at least 55,000 Jews were able to find refuge in Palestine[26] before the British authorities closed that destination in 1939.

On 31 December 1938, both the Nansen Office and High Commission were dissolved and replaced by the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees under the Protection of the League.[16] This coincided with the flight of several hundred thousand Spanish Republicans to France after their loss to the Nationalists in 1939 in the Spanish Civil War.[27]

The conflict and political instability during World War II led to massive numbers of refugees (see World War II evacuation and expulsion). In 1943, the Allies created the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to provide aid to areas liberated from Axis powers, including parts of Europe and China. By the end of the War, Europe had more than 40 million refugees.[28] UNRRA was involved in returning over seven million refugees, then commonly referred to as displaced persons or DPs, to their country of origin and setting up displaced persons camps for one million refugees who refused to be repatriated. Even two years after the end of War, some 850,000 people still lived in DP camps across Western Europe.[29] After the establishment of Israel in 1948, Israel accepted more than 650,000 refugees by 1950. By 1953, over 250,000 refugees were still in Europe, most of them old, infirm, crippled, or otherwise disabled.

Post-WWII population transfers

After the Soviet armed forces recaptured eastern Poland from the Germans in 1944, the Soviets unilaterally declared a new frontier between the Soviet Union and Poland approximately at the Curzon Line, despite the protestations from the Polish government-in-exile in London and the western Allies at the Teheran Conference and the Yalta Conference of February 1945. After the German surrender on 7 May 1945, the Allies occupied the remainder of Germany, and the Berlin declaration of 5 June 1945 confirmed the division of Allied-occupied Germany according to the Yalta Conference, which stipulated the continued existence of the German Reich as a whole, which would include its eastern territories as of 31 December 1937. This did not impact on Poland's eastern border, and Stalin refused to be removed from these eastern Polish territories.

In the last months of World War II, about five million German civilians from the German provinces of East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia fled the advance of the Red Army from the east and became refugees in Mecklenburg, Brandenburg and Saxony. Since the spring of 1945 the Poles had been forcefully expelling the remaining German population in these provinces. When the Allies met in Potsdam on 17 July 1945 at the Potsdam Conference, a chaotic refugee situation faced the occupying powers. The Potsdam Agreement, signed on 2 August 1945, defined the Polish western border as that of 1937, (Article VIII)[30] placing one fourth of Germany's territory under the Provisional Polish administration. Article XII ordered that the remaining German populations in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary be transferred West in an "orderly and humane" manner.[30] (See Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50).)

Although not approved by Allies at Potsdam, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans living in Yugoslavia and Romania were deported to slave labour in the Soviet Union, to Allied-occupied Germany, and subsequently to the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), Austria and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). This entailed the largest population transfer in history. In all 15 million Germans were affected, and more than two million perished during the expulsions of the German population.[31][32][33][34][35] (See Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950).) Between the end of War and the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961, more than 563,700 refugees from East Germany traveled to West Germany for asylum from the Soviet occupation.

During the same period, millions of former Russian citizens were forcefully repatriated against their will into the USSR.[36] On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the USSR.[37] The interpretation of this Agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets regardless of their wishes. When the war ended in May 1945, British and U.S. civilian authorities ordered their military forces in Europe to deport to the Soviet Union millions of former residents of the USSR, including many persons who had left Russia and established different citizenship decades before. The forced repatriation operations took place from 1945 to 1947.[38]

At the end of World War II, there were more than 5 million "displaced persons" from the Soviet Union in Western Europe. About 3 million had been forced laborers (Ostarbeiters)[39] in Germany and occupied territories.[40][41] The Soviet POWs and the Vlasov men were put under the jurisdiction of SMERSH (Death to Spies). Of the 5.7 million Soviet prisoners of war captured by the Germans, 3.5 million had died while in German captivity by the end of the war.[42][43] The survivors on their return to the USSR were treated as traitors (see Order No. 270).[44][45] Over 1.5 million surviving Red Army soldiers imprisoned by the Nazis were sent to the Gulag.[46][47]

Poland and Soviet Ukraine conducted population exchanges following the imposition of a new Poland-Soviet border at the Curzon Line in 1944. About 2,100,000 Poles were expelled west of the new border (see Repatriation of Poles), while about 450,000 Ukrainians were expelled to the east of the new border. The population transfer to Soviet Ukraine occurred from September 1944 to May 1946 (see Repatriation of Ukrainians). A further 200,000 Ukrainians left southeast Poland more or less voluntarily between 1944 and 1945.[48]

The International Refugee Organization (IRO) was founded on April 20, 1946, and took over the functions of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, which was shut down in 1947. While the handover was originally planned to take place at the beginning of 1947, it did not occur until July 1947.[49] The International Refugee Organization was a temporary organization of the United Nations (UN), which itself had been founded in 1945, with a mandate to largely finish the UNRRA's work of repatriating or resettling European refugees. It was dissolved in 1952 after resettling about one million refugees.[50] The definition of a refugee at this time was an individual with either a Nansen passport or a "Certificate of identity" issued by the International Refugee Organization.

The Constitution of the International Refugee Organization, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 15, 1946, specified the agency's field of operations. Controversially, this defined "persons of German ethnic origin" who had been expelled, or were to be expelled from their countries of birth into the postwar Germany, as individuals who would "not be the concern of the Organization." This excluded from its purview a group that exceeded in number all the other European displaced persons put together. Also, because of disagreements between the Western allies and the Soviet Union, the IRO only worked in areas controlled by Western armies of occupation.

UNHCR

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

Headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (established December 14, 1950) protects and supports refugees at the request of a government or the United Nations and assists in their return or resettlement. All refugees in the world are under the UNHCR mandate except Palestinian refugees who fled the future Jewish state between 1947 and 1949, as a result of the 1948 Palestine war, and their descendants, who are assisted by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). However, Palestinian Arabs who fled the West Bank and Gaza after 1949 (for example, during the 1967 Six Day war) are under the jurisdiction of the UNHCR.

UNHCR provides protection and assistance not only to refugees, but also to other categories of displaced or needy people. These include asylum seekers, refugees who have returned home but still need help in rebuilding their lives, local civilian communities directly affected by the movements of refugees, stateless people and so-called internally displaced people (IDPs). IDPs are civilians who have been forced to flee their homes, but who have not reached a neighboring country and therefore, unlike refugees, are not protected by international law and may find it hard to receive any form of assistance. As the nature of war has changed in the last few decades, with more and more internal conflicts replacing interstate wars, the number of IDPs has increased significantly to an estimated 5 million people worldwide. According to Bogumil Terminski the stabilization of refugee problem worldwide is the main cause of the development of the studies on internal displacement.

The agency is mandated to lead and co-ordinate international action to protect refugees and resolve refugee problems worldwide. Its primary purpose is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees. It strives to ensure that everyone can exercise the right to seek asylum and find safe refuge in another State, with the option to return home voluntarily, integrate locally or to resettle in a third country.

UNHCR's mandate has gradually been expanded to include protecting and providing humanitarian assistance to what it describes as other persons "of concern," including internally displaced persons (IDPs) who would fit the legal definition of a refugee under the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol, the 1969 Organization for African Unity Convention, or some other treaty if they left their country, but who presently remain in their country of origin. UNHCR thus has missions in Colombia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Serbia and Montenegro and Côte d'Ivoire to assist and provide services to IDPs. Asia – 8,603,600 Africa – 5,169,300 Europe – 3,666,700 Latin America and Caribbean – 2,513,000 North America – 716,800 Oceania – 82,500.

International attitude

Law

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2013) |

Under international law, refugees are individuals who:

- are outside their country of nationality or habitual residence;

- have a well-founded fear of persecution because of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion; and

- are unable or unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of that country, or to return there, for fear of persecution.

Refugee law encompasses both customary law, peremptory norms, and international legal instruments. These include:

- The 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees; also referred to as the Geneva Convention;

- The 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees;

- The 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa[51]

- The 1974 United Nations Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict

World Refugee Day

World Refugee Day occurs on June 20. The day was created in 2000 by a special United Nations General Assembly Resolution. June 20 had previously been commemorated as African Refugee Day in a number of African countries.

In the United Kingdom World Refugee Day is celebrated as part of Refugee Week. Refugee Week is a nationwide festival designed to promote understanding and to celebrate the cultural contributions of refugees, and features many events such as music, dance and theatre.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the World Day of Migrants and Refugees is celebrated in January each year, having been instituted in 1914 by Pope Pius X.

Reasons for refugee crises

Asylum seekers

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

International refugee law defines a refugee as someone who seeks refuge in a foreign country because of war and violence, or out of fear of persecution. The United States recognizes persecution "on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group" as grounds for seeking asylum.[52] Until a request for refuge has been accepted, the person is referred to as an asylum seeker. Only after the recognition of the asylum seeker's protection needs, he or she is officially referred to as a refugee and enjoys refugee status, which carries certain rights and obligations according to the legislation of the receiving country.

The practical determination of whether a person is a refugee or not is most often left to certain government agencies within the host country. This can lead to a situation where the country will neither recognize the refugee status of the asylum seekers nor see them as legitimate migrants and treat them as illegal aliens.

The percentage of asylum/refugee seekers who (it has been deemed) do not meet the international standards of special-needs refugee, and for whom resettlement is deemed proper, varies from country to country. Failed asylum applicants are most often deported, sometimes after imprisonment or detention, as in the United Kingdom. In the United Kingdom, more than one in four decisions to refuse an asylum seeker protection UK are overturned by Immigration Judges.[53] Campaigners have suggested that this figure suggests the process of allocation refugee status is inefficient or flawed.

A claim for asylum may also be made onshore, usually after making an unauthorized arrival. Some governments are tolerant and accepting of onshore asylum claims; other governments arrest or detain those who attempt to seek asylum; sometimes while processing their claims.[citation needed]

Non-governmental organizations concerned with refugees and asylum seekers have pointed out difficulties for displaced persons to seek asylum in industrialized countries. As their immigration policy often focuses on the fight of irregular migration and the strengthening of border controls it deters displaced persons from entering territory in which they could lodge an asylum claim. The lack of opportunities to legally access the asylum procedures can force asylum seekers to undertake often expensive and hazardous attempts at illegal entry.

Concerns over arbitrariness in asylum adjudication in the United States have led some commentators to describe the process as refugee roulette; that is, a system in which the identity of the adjudicator, rather than the strength of the asylum seeker's claim, is the determining factor in winning an asylum claim.[citation needed]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Climate

Although they do not fit the definition of refugees set out in the UN Convention, people displaced by the effects of climate change have often been termed "climate refugees"[56] or "climate change refugees".[57] The term 'environmental refugee' is also commonly used and an estimate 25 million people can currently be classified as such.[58] The alarming predictions by the UN, charities and some environmentalists, that between 200 million and 1 billion people could flood across international borders to escape the impacts of climate change in the next 40 years are realistic.[59] Case studies from Bolivia, Senegal and Tanzania, three countries extremely prone to climate change, show that people affected by environmental degradation rarely move across borders. Instead, they adapt to new circumstances by moving short distances for short periods, often to cities.[60] Millions of people live in places that are vulnerable to the effects of climate change. They face extreme weather conditions such as droughts or floods. Their lives and livelihoods might be threatened in new ways and create new vulnerabilities.[61] Migration is in many developing countries a coping strategy to mitigate poverty and is already happening independent of the effects of climate change and environmental degradation. It is a selective process and the poorest and most vulnerable people are often excluded as they will find it almost impossible to move due to a lack of necessary funds or social support.[58]

Security threats

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2010) |

Very rarely, refugees have been used and recruited as refugee warriors,[62] and the humanitarian aid directed at refugee relief has very rarely been utilized to fund the acquisition of arms.[63] Support from a refugee-receiving state has rarely been used to enable refugees to mobilize militarily, enabling conflict to spread across borders.[64]

Economic migrants

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

Not all migrants seeking shelter in another country fall under the definition of "refugee" according to article 1A of the Geneva Convention. In 1951, when the text of the Convention was discussed, the parties of the treaty had the idea that slavery was a thing from the past: therefore escaped and fleeing slaves are a group not mentioned in the definition, as well as a category that later emerged: the climate refugee (:Environmental migrant") (see below).

In 2008-2009, the humanitarian nature of the mass movement of Zimbabweans to neighbouring Southern African blurred the distinction between what is a "refugee" and an "economic migrant". Such people fit neither category perfectly and have more general needs, rights and responsibilities, that fall outside the specific mandate of the UNHCR. They fall between the cracks, according to the report Zimbabwean Migration into Southern Africa: New Trends and Responses, released in November 2009 by the Forced Migration Studies Programme (FMSP) at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.[65][66] According to the researchers, a lack of protection of migrants in the region was based on a "false distinction" between a forced and an economic migrant, instead of focusing on the real and urgent needs some of these migrants have. The report suggested that a better term would be "forced humanitarian migrants", who moved for the purpose of their and their dependents' basic survival.

To emphasize the importance of a common humanitarian position on the outflow of Zimbabweans into the region the Regional Office for Southern Africa of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs coined the term "migrants of humanitarian concern" in 2008.

Official responses to Zimbabwean migration in Botswana, Malawi, Zambia and Mozambique are still premised on the original definition from the 1951 Convention, and so were said to be failing to protect both Zimbabweans and their own citizens". Those crossing the border were neither refugees - most did not even apply for refugee status - and, given the extent of economic collapse at home, nor they could hardly be considered as "voluntary" economic migrants. So many of them were not legally protected, nor do they receive humanitarian support, as they fell outside the mandates of the support structures offered by government and non-government institutions. In Botswana, Zambia and Malawi, asylum is available to Zimbabweans; in Mozambique, the few applicants for asylum had been rejected due to the state's decision to consider Zimbabweans as 'economic' and not forced humanitarian migrants.

Except for South Africa, protection and access to services in most countries in the region is contingent on receiving the refugee status, and require asylum seekers to stay in isolated camps, unable to work or travel, and thus send money to relatives that stayed behind in Zimbabwe. South Africa was considering the introduction of a special permit for Zimbabweans, but the policy was still under review.

Boat people

The term "boat people" came into common use in the 1970s with the mass exodus of Vietnamese refugees following the Vietnam War. It is a widely used form of migration for people migrating from Cuba, Haiti, Morocco, Vietnam or Albania. They often risk their lives on dangerously crude and overcrowded boats to escape oppression or poverty in their home nations. Events resulting from the Vietnam War led many people in Cambodia, Laos, and especially Vietnam to become refugees in the late 1970s and 1980s. In 2001, 353 asylum seekers sailing from Indonesia to Australia drowned when their vessel sank.

The main danger to a boat person is that the boat he or she is sailing in may actually be anything that floats and is large enough for passengers. Although such makeshift craft can result in tragedy, in 2003 a small group of 5 Cuban refugees attempted (unsuccessfully, but un-harmed) to reach Florida in a 1950s pickup truck made buoyant by oil barrels strapped to its sides.

Boat people are frequently a source of controversy in the nation they seek to immigrate to, such as the United States, New Zealand, Germany, France, Russia, Canada, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Spain and Australia. Boat people are often forcibly prevented from landing at their destination, such as under Australia's Pacific Solution (which operated from 2001 until 2008), or they are subjected to mandatory detention after their arrival.[67]

Refugee absorption solutions

Camps

A refugee camp is a place built by governments or NGOs (such as the International Committee of the Red Cross) to receive refugees. People may stay in these camps, receiving emergency food and medical aid, until it is safe to return to their homes or until they are retrieved by other people outside the camps. In some cases, often after several years, other countries decide it will never be safe to return these people, and they are resettled in "third countries", away from the border they crossed. However, more often than not, refugees are not resettled. In the meantime, they are at risk for disease, child soldier recruitment, terrorist recruitment, and physical and sexual violence. There are estimated to be 700 refugee camp locations.[68]

Resettlement

| Country | 2010 resettlements[69] |

| United States | 54,077 |

| Canada | 6,706 |

| Australia | 5,636 |

| Sweden | 1,789 |

| Norway | 1,088 |

| United Kingdom | 695 |

| Finland | 543 |

| New Zealand | 535 |

| Germany | 457 |

| Netherlands | 430 |

| All Others | 958 |

| Total | 72,914 |

Resettlement involves the assisted movement of refugees who are unable to return home to safe third countries.[70][71] The UNHCR has traditionally seen resettlement as the least preferable of the "durable solutions" to refugee situations.[72] However, in April 2000 the then UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadako Ogata, stated:

Resettlement can no longer be seen as the least-preferred durable solution; in many cases it is the only solution for refugees

— Sadako Ogata, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, April 2000[72]

Resettlement involves a number of difficulties, most of them involving the often extreme cultural transition needed to adapt to life in the country of resettlement. For the many refugees going from rural undeveloped countries to life in urban centers, public transport, education, health care systems, job applications, and even grocery shopping can be difficult to navigate. Language barriers also frequently pose a problem. Even aside from material problems, resettled refugees can struggle with issues of identity and belonging, as societal integration can be very difficult in a completely different culture, and discrimination frequently further inhibits the process.[73]

The UNHCR does recognize benefits to resettlement as well, however. On their website, they bring attention to the fact that refugees have much to bring to the countries in which they are resettled in terms of culture and labor, going as far as to say that “both refugee resettlement and general migration are now recognized as critical factors in the economic success of a number of industrialized countries.”[73] According to the UNHCR, resettlement serves three primary functions: securing fundamental human rights such as “life, liberty, safety, health,” etc.for refugees who are at risk in camps, providing a long-term solution to the issue of displacement for large numbers of refugees, and alleviating the burden on countries offering asylum to such displaced peoples.[74] Frequently, these countries of asylum are some of the world’s poorest nations and cannot handle the large influx of persons that occur when war, persecution, or other events drive refugees across their borders into their country.[73]

However, only about 1% of the over 10.5 million refugees the UNHCR typically deals with are submitted for resettlement. Around 108,000 refugees were considered for the opportunity to be resettled in 2010, with the primary countries of origin being Iraq, Myanmar, and Bhutan.[75]

UNHCR referred more than 121,000 refugees for consideration for resettlement in 2008. This was the highest number for 15 years. In 2007, 98,999 people were referred. UNHCR referred 33,512 refugees from Iraq, 30,388 from Burma/Myanmar and 23,516 from Bhutan in 2008.[71]

In terms of resettlement departures, in 2008, 65,548 refugees were resettled in 26 countries, up from 49,868 in 2007.[71] The largest number of UNHCR-assisted departures were from Thailand (16,807), Nepal (8,165), Syria (7,153), Jordan (6,704) and Malaysia (5,865).[71] Note that these are the countries that refugees were resettled from, not their countries of origin.

A number of third countries run specific resettlement programmes in co-operation with UNHCR. The size of these programmes is shown in the table.[72] The largest programmes are run by the United States, Canada and Australia. A number of European countries run smaller schemes and in 2004 the United Kingdom established its own scheme, known as the Gateway Protection Programme[72] with an initial annual quota of 500, which rose to 750 in the financial year 2008/09.[76]

In September 2009, the European Commission unveiled plans for new Joint EU Resettlement Programme. The scheme would involve EU member states deciding together each year which refugees should be given priority. Member states would receive €4,000 from the European Refugee Fund per refugee resettled.[77]

Between 1981, when Japan ratified the U.N. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and 2002, Japan recognized only 305 persons as refugees.[78] According to the UNHCR, in 2006 Japan accepted 26 refugees for resettlement.[79]

The United States helped resettle roughly 2 million refugees between 1945 and 1979, when their refugee resettlement program was restructured. They now make use of 11 “Voluntary Agencies" (VOLAGS), which are non-governmental organizations that assist the government in the resettlement process.[80] These organizations assist the refugees with the day-to-day needs of the large transition into a completely new culture. Usually, they are not funded by the government, but instead rely on their own resources and volunteers. Most of them have local offices, and caseworkers that provide individualized aid to each refugee’s situation. They do rely on the sponsorship of individuals or groups, such as faith-based congregations or local organizations. The largest of the VOLAGS is the Migration and Refugee Services of the U.S. Catholic Conference.[80] Others include Church World Service, Episcopal Migration Ministries, the Ethiopian Community Development Council, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the International Rescue Committee, Lutheran Immigration Services, the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, and World Relief.[81]

There are a number of advantages to the strategy of using agencies other than the government to directly assist in resettlement. First of all, it has been estimated that for a federal or state bureaucracy to resettle refugees instead of the VOLAGS would double the overall cost. These agencies are often able to procure large quantities of donations and, more importantly, volunteers. According to one study, when the fact that resettlement workers often have to work nights, weekends, and overtime in order to meet the demands of the large cultural transition of new refugees is taken into account, the use of volunteers reduces the overall cost down to roughly a quarter.[82] VOLAGS are also more flexible and responsive than the government since they are smaller and rely on their own funds.

Right of return

Even in a supposedly "post-conflict" environment, it is not a simple process for refugees to return home.[83] The UN Pinheiro Principles are guided by the idea that people not only have the right to return home, but also the right to the same property.[83] It seeks to return to the pre-conflict status quo and ensure that no one profits from violence. Yet this is a very complex issue and every situation is different; conflict is a highly transformative force and the pre-war status-quo can never be reestablished completely, even if that were desirable (it may have caused the conflict in the first place).[83] Therefore, the following are of particular importance to the right to return:[83]

- may never have had property (e.g. in Afghanistan);

- cannot access what property they have (Colombia, Guatemala, South Africa and Sudan);

- ownership is unclear as families have expanded or split and division of the land becomes an issue;

- death of owner may leave dependents without clear claim to the land;

- people settled on the land know it is not theirs but have nowhere else to go (as in Colombia, Rwanda and Timor-Leste); and

- have competing claims with others, including the state and its foreign or local business partners (as in Aceh, Angola, Colombia, Liberia and Sudan).

Historical and contemporary crises

Movements in Africa

Since the 1950s, many nations in Africa have suffered civil wars and ethnic strife, thus generating a massive number of refugees of many different nationalities and ethnic groups. The number of refugees in Africa increased from 860,000 in 1968 to 6,775,000 by 1992.[84] By the end of 2004, that number had dropped to 2,748,400 refugees, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.[85] (That figure does not include internally displaced persons, who do not cross international borders and so do not fit the official definition of refugee.)

Many refugees in Africa cross into neighboring countries to find haven; often, African countries are simultaneously countries of origin for refugees and countries of asylum for other refugees. The Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, was the country of origin for 462,203 refugees at the end of 2004, but a country of asylum for 199,323 other refugees.

Countries in Africa from where 5,000 or more refugees originated as of the end of 2004 are listed below.[86] The largest number of refugees are from Sudan and have fled either the longstanding and recently concluded Sudanese Civil War or the Darfur conflict and are located mainly in Chad, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

|

Angola

Decolonisation during the 1960s and 1970s often resulted in the mass exodus of European-descended settlers out of Africa – especially from North Africa (1.6 million European pieds noirs),[87] Congo, Mozambique and Angola.[88] By the mid-1970s, the Portugal's African territories were lost, and nearly one million Portuguese or persons of Portuguese descent left those territories (mostly Portuguese Angola and Mozambique) as destitute refugees – the retornados.[89]

The Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), one of the largest and deadliest Cold War conflicts, erupted shortly after and spread out across the newly independent country. At least one million people were killed, four million were displaced internally and another half million fled as refugees.[90]

Uganda

In the 1970s Uganda and other East African nations implemented racist policies that targeted the Asian population of the region. Uganda under Idi Amin's leadership was particularly most virulent in its anti-Asian policies, eventually resulting in the expulsion and ethnic cleansing of Uganda's Asian minority.[91] Uganda's 80,000 Asians were mostly Indians born in the country. India had refused to accept them.[92] Most of the expelled Indians eventually settled in the United Kingdom, Canada and in the United States.[93]

The Lord's Resistance Army insurgency forced many civilians to live in internally displaced person camps.

Great Lakes crisis

In the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, over two million people fled into neighboring countries, in particular Zaire. The refugee camps were soon controlled by the former government and Hutu militants who used the camps as bases to launch attacks against the new government in Rwanda. Little action was taken to resolve the situation and the crisis did not end until Rwanda-supported rebels forced the refugees back across the border at the beginning of the First Congo War.

Darfur

An estimated 2.5 million people, roughly one-third the population of the Darfur area, have been forced to flee their homes after attacks by Janjaweed Arab militia backed by Sudanese troops during the ongoing Darfur conflict in western Sudan since roughly 2003.[94][95]

African refugees in Israel

Since 2003, an estimated 70,000 illegal immigrants from various African countries have crossed into Israel.[96] Some 600 refugees from the Darfur region of Sudan have been granted temporary resident status to be renewed every year, though not official refugee state.[97] Another 2,000 refugees from the conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia have been granted temporary resident status on humanitarian grounds. Israel prefers not to recognize them as refugees so as not to offend Eritrea and Ethiopia, though Sudanese, who are from an enemy state, are also not recognized as refugees. In effect, Israeli politicians, including the current Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu, have referred to the refugees as a threat to Israel's "Jewish character".[98] African refugees are sometimes subject to racism and racial riots, as well as on-man assaults, have been occurring in Israel, especially in southern Tel Aviv since mid-2012.[99]

During the past years, conflicts have occurred between Israelis and African immigrants in southern Tel-aviv, mostly due to poverty issues of both sides. Locals accuse African immigrants of Rape,[100] Stealing[101] and assault, making racial issues emerge in the south part of Tel-aviv, which became an immigrant populated area.

In 2012 Reuters reported that Israel may jail "illegal immigrants" for up to three years under a law put into effect to stem the flow of Africans across the desert border with Egypt.[102] Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said that "If we don't stop their entry, the problem that currently stands at 60,000 could grow to 600,000, and that threatens our existence as a Jewish and democratic state."[103]

African refugees in Egypt

There are tens of thousands of Sudanese refugees in Egypt, most of them seeking refuge from ongoing military conflicts in their home country of Sudan. Their official status as refugees is highly disputed, and they have been subject to racial discrimination and police violence. They live among a much larger population of Sudanese migrants in Egypt, more than two million people of Sudanese nationality (by most estimates; a full range is 750,000 to 4 million (FMRS 2006:5) who live in Egypt. The U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants believes many more of these migrants are in fact refugees, but see little benefit in seeking recognition.

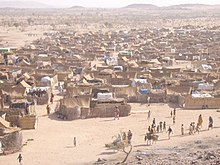

Western Sahara conflict

It is estimated that between 165,000 - 200,000 Sahrawis – people from the disputed territory of Western Sahara – have lived in five large refugee camps near Tindouf in the Algerian part of the Sahara Desert since 1975.[104][105] The UNHCR and WFP are presently engaged in supporting what they describe as the "90,000 most vulnerable" refugees, giving no estimate for total refugee numbers.[106]

Libyan Civil War

Refugees of the 2011 Libyan civil war are the people, predominantly of Libyan nationality, who fled or were expelled from their homes during the 2011 Libyan civil war, from within the borders of Libya to the neighbouring states of Tunisia, Egypt and Chad, as well as to European countries, across the Mediterranean, as Boat people. The majority of Libyan refugees are Arabs and Berbers, though many of other ethnicities, temporarily living in Libya, originated from sub-Saharan Africa, were also among the first refugee waves to exit the country. The total Libyan refugee numbers are estimated at near one million as of June 2011. About half of them had returned to Libyan territory during summer 2011, though large refugee camps on Tunisian and Chad border kept being overpopulated.

Movements in the Americas

Latin Americans

More than one million Salvadorans were displaced during the Salvadoran Civil War from 1975 to 1982. About half went to the United States, most settling in the Los Angeles area. There was also a large exodus of Guatemalans during the 1980s, trying to escape from the Civil War and genocide there as well. These people went to Southern Mexico and the U.S.

From 1991 through 1994, following the military coup d'état against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, thousands of Haitians fled violence and repression by boat. Although most were repatriated to Haiti by the U.S. government, others entered the United States as refugees. Haitians were primarily regarded as economic migrants from the grinding poverty of Haiti, the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere.

The victory of the forces led by Fidel Castro in the Cuban Revolution led to a large exodus of Cubans between 1959 and 1980. Thousands of Cubans yearly continue to risk the waters of the Straits of Florida seeking better economic and political conditions in the U.S. In 1999 the highly publicized case of six-year-old Elián González brought the covert migration to international attention. Measures by both governments have attempted to address the issue; the U.S. instituted a wet feet, dry feet policy allowing refuge to those travelers who manage to complete their journey, and the Cuban government have periodically allowed for mass migration by organizing leaving posts. The most famous of these agreed migrations was the Mariel boatlift of 1980.

Colombia has one of the world's largest populations of internally displaced persons (IDPs), with estimates ranging from 2.6 to 4.3 million people, due to the ongoing Colombian armed conflict. The larger figure is cumulative since 1985.[107][108] It is now estimated by the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants that there are about 150,000 Colombians in "refugee-like situations" in the United States, not recognized as refugees or subject to any formal protection.

United States

During the Vietnam War, many U.S. citizens who were conscientious objectors and wished to avoid the draft sought political asylum in Canada. President Jimmy Carter issued an amnesty. Since 1975, the U.S. has resettled approximately 2.6 million refugees, with nearly 77% being either Indochinese or citizens of the former Soviet Union. Since the enactment of the Refugee Act of 1980, annual admissions figures have ranged from a high of 207,116 in 1980 to a low of 27,100 in 2002.

Currently, nine national voluntary agencies resettle refugees nationwide on behalf of the U.S. government: Church World Service, Ethiopian Community Development Council, Episcopal Migration Ministries, Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, International Rescue Committee, U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, and World Relief.

Jesuit Refugee Service/USA (JRS/USA) has worked to help resettle Bhutanese refugees in the United States. The mission of JRS/USA is to accompany, serve and defend the rights of refugees and other forcibly displaced persons. JRS/USA is one of 10 geographic regions of Jesuit Refugee Service, an international Catholic organization sponsored by the Society of Jesus. In coordination with JRS’s International Office in Rome, JRS/USA provides advocacy, financial and human resources for JRS regions throughout the world.

The U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) funds a number of organizations that provide technical assistance to voluntary agencies and local refugee resettlement organizations.[109] RefugeeWorks, headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland, is ORR's training and technical assistance arm for employment and self-sufficiency activities, for example. This nonprofit organization assists refugee service providers in their efforts to help refugees achieve self-sufficiency. RefugeeWorks publishes white papers, newsletters and reports on refugee employment topics.[110]

In 2005, as a result of hurricane Katrina, New Orleans citizens were referred to be the media as "refugees". Many New Orleanians consider the term refugee to be an insult. Resident Joseph Melancon explains, “And they had the nerve to call us refugees! When I heard they called us refugees, I couldn’t do nothing but drop my head cause I said I’m a United States citizen!” Actor Wendell Pierce says, “Damn, when the storm came it blew away our citizenship too?” Such narratives regarding the loss of citizenship are used to illustrate the trauma endured and the degradation citizens inflicted during the storm and they are also to show the federal government failing to uphold some contractual responsibility. In Sanctuary: African Americans and Empire, Waligora Davis remarks that, “The problem of the refugee, the stateless, the semi-colonial that DuBois names the black American, is a problem of the refugees relationship to the law and the state. Collectively, such persons signify a community outside the precincts of laws, they remain marginalized as a result of their loss of withheld citizenship.” Yet, these narratives and Waligora-Davis’ definition does not fully engage the ways in which ‘refugee’ can be deployed as a diasporic trope for empowerment, similar to how The Fugees utilize the term in the diaspora. Here, I would then like to incorporate Alexander Weyheliye’s “Sounding Diasporic Citizenship” to consider the possibility for the term “refugee” to be a liberating call to build community and redress trauma throughout the New Orleans diaspora using the example of the hip hop group, the Fugees.

Movements in Asia

Afghanistan

From the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 until the late 2001 US-led invasion, about six million Afghan refugees have fled to neighboring Pakistan (mainly NWFP) and Iran, making Afghanistan the largest refugee-producing country. Since early 2002, more than 5 million Afghan refugees have repatriated through the UNHCR from both Pakistan and Iran back to their native country, Afghanistan.[111] Approximately 3.5 million from Pakistan[112] while the remaining 1.5 million from Iran. Since 2007 the Iranian government has forcibly deported mostly unregistered (and some registered) Afghan refugees back to Afghanistan, with 362,000 being deported in 2008.[113] More impormation: • The first Afghanistan people to arrive in Australia was during the 1860s • In 1979, the second group of immigrants from Afghanistan came to Australia, attacking hospitals, schools and mosques. Australians kept a small number as refugees

As of March 2009, some 1.7 million registered Afghan refugees still remain in Pakistan. This include the many who were born in Pakistan during the last 30 years but still counted as citizens of Afghanistan. They are allowed to work and study until the end of 2012.[114] 935,600 registered Afghans are living in Iran, which also include the ones born inside Iran.[115]

Dissolution of the British Raj, The Partition of 1947 and Independence

The partition of the British Raj provinces of Panjab and Bangal and the subsequent independence of Pakistan and one day later of India in 1947 resulted in the largest human movement in history. In this population exchange, approximately 7 million Hindus and Sikhs from Bangladesh and Pakistan moved to India while approximately 7 million Muslims from India moved to Pakistan. Approximately one million Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs died during this event.[citation needed]

Bangladeshis in India in 1971