List of Indian inventions and discoveries: Difference between revisions

←Replaced content with ' {' |

m Reverted edits by 120.56.232.219 (talk) to last version by ClueBot NG |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2013}}{{use Indian English|date=March 2014}} |

|||

{{more footnotes|date=February 2014}} |

|||

This '''list of Indian inventions and discoveries''' details the inventions, scientific discoveries and contributions of India, including both the ancient and medieval nations in the subcontinent historically [[History of India|referred to as India]] and the modern Indian state. It draws from the whole [[culture of India|cultural]] and [[history of Indian science and technology|technological history]] of India, during which [[Architecture of India|architecture]], [[Indian astronomy|astronomy]], [[Cartography of India|cartography]], [[History of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent|metallurgy]], [[Indian logic|logic]], [[Indian mathematics|mathematics]], [[History of measurement systems in India|metrology]] and [[Mining in India|mineralogy]] were among the branches of study pursued by [[:Category:Indian academics|its scholars]]. During recent times [[science and technology in the Republic of India]] has also focused on [[Automobile industry in India|automobile engineering]], [[Information technology in India|information technology]], [[Communications in India|communications]] as well as research into [[Indian Space Research Organisation|space]] and [[Indian Antarctic Program|polar]] technology. |

|||

For the purposes of this list, [[invention]]s are regarded as technological firsts developed in India, and as such does not include foreign technologies which India acquired through contact. It also does not include technologies or discoveries developed elsewhere and later invented separately by Indian. Changes in minor concepts of design or style and artistic innovations do not appear on the list. |

|||

{ |

|||

==Inventions== |

|||

{{Duplication|date=June 2013}} |

|||

{{See also|List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilization}} |

|||

* '''[[Button]]''': Ornamentl buttons—made from [[seashell]]—were used in the [[Indus Valley Civilization]] for ornamental purposes by 2000 BCE.<ref name=Hesse&Hesse>Hesse, Rayner W. & Hesse (Jr.), Rayner W. (2007). ''Jewelrymaking Through History: An Encyclopedia''. Greenwood Publishing Group. 35. ISBN 0-313-33507-9.</ref> Some buttons were carved into geometric shapes and had holes pierced into them so that they could be attached to clothing by using a thread.<ref name=Hesse&Hesse/> Ian McNeil (1990) holds that: "The button, in fact, was originally used more as an ornament than as a fastening, the earliest known being found at Mohenjo-daro in the [[Indus Valley]]. It is made of a curved shell and about 5000 years old."<ref>McNeil, Ian (1990). ''An encyclopaedia of the history of technology''. Taylor & Francis. 852. ISBN 0-415-01306-2.</ref> |

|||

* '''[[India ink|Carbon pigment]]''': The source of the carbon pigment used in [[India ink]] was India.<ref name="gottsegen 30">Gottsegen, page 30.</ref><ref name=Smithja23>Smith, J. A. (1992), page 23</ref> In India, the carbon black from which India ink is produced is obtained by burning bones, tar, pitch, and other substances.<ref name=Smithja23/><ref>"India ink", ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]'', 2008</ref> [[Ink]] itself has been used in India since at least the 4th century BCE.<ref name=Banerji673/> ''Masi'', an early ink in India was an admixture of several chemical components.<ref name=Banerji673>Banerji, page 673</ref> Indian documents written in [[Kharosthi]] with ink have been unearthed in [[Xinjiang]].<ref>Sircar, page 206</ref> The practice of writing with ink and a sharp pointed needle was common in ancient [[South India]].<ref>Sircar, page 62</ref> Several [[Jain]] sutras in India were compiled in ink.<ref>Sircar, page 67</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Calico (textile)|Calico]]''': Calico had originated in the subcontinent by the 11th century and found mention in Indian literature, by the 12th-century writer Hemachandra. He has mentioned calico fabric prints done in a lotus design.<ref name=eb-calico>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''calico''</ref> The Indian textile merchants traded in calico with the Africans by the 15th century and calico fabrics from [[Gujarat]] appeared in [[Egypt]].<ref name=eb-calico/> Trade with Europe followed from the 17th century onwards.<ref name=eb-calico/> Within India, calico originated in [[Kozhikode]].<ref name=eb-calico/> |

|||

* '''[[Carding|Carding devices]]''': Historian of science [[Joseph Needham]] ascribes the invention of bow-instruments used in textile technology to India.<ref name=Baber1/> The earliest evidence for using bow-instruments for carding comes from India (2nd century CE).<ref name=Baber1/> These carding devices, called ''kaman'' and ''dhunaki'' would loosen the texture of the fiber by the means of a vibrating string.<ref name=Baber1/> |

|||

[[File:SpreadofChessfromIndia.jpg|thumb|Map showing origin and diffusion of chess from India to [[Asia]], [[Africa]], and [[Europe]], and the changes in the native names of the game in corresponding places and time.]] |

|||

* '''[[Chaturanga]]''': The precursor of '''[[chess]]''' originated in India during the [[Gupta dynasty]] (c. 280-550 CE).<ref name=Murray1913>Murray (1913)</ref><ref name=Forbes1860>Forbes (1860)</ref><ref name=JonesAj121>Jones, William (1807). "On the Indian Game of Chess". pages 323-333</ref><ref name=LindeGM>Linde, Antonius (1981)</ref> Both the [[Persian people|Persians]] and [[Arab]]s ascribe the origins of the game of Chess to the Indians.<ref name=JonesAj121/><ref name=Wilkinson>Wilkinson, Charles K (May 1943)</ref><ref name=Bird48>Bird (1893), page 63</ref> The words for "chess" in [[Old Persian]] and [[Arabic]] are ''chatrang'' and ''[[shatranj]]'' respectively — terms derived from ''[[chaturanga|caturaṅga]]'' in [[Sanskrit]],<ref name=Whyld>Hooper & Whyld (1992), page 74</ref><ref name=SBI106>Sapra, Rahul (2000). "Sports in India". Students' Britannica India (Vol. 6). Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. p. 106. ISBN 0-85229-762-9.</ref> which literally means an ''army of four divisions'' or ''four corps''.<ref name=Meri>Meri (2005), page 148</ref><ref name=Basham208>Basham (2001), page 208</ref> Chess spread throughout the world and many variants of the game soon began taking shape.<ref name=Britannica1>Encyclopædia Britannica (2002). ''Chess: Ancient precursors and related games''.</ref> This game was introduced to the [[Near East]] from India and became a part of the princely or courtly education of [[Persian Empire|Persian]] nobility.<ref name=Meri/> [[Buddhist]] pilgrims, [[Silk Road]] traders and others carried it to the [[Far East]] where it was transformed and assimilated into a game often played on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares.<ref name=Britannica1/> Chaturanga reached Europe through Persia, the [[Byzantine empire]] and the expanding [[Arabian]] empire.<ref name=Basham208/><ref name=ChessEurope>Encyclopædia Britannica (2007). ''Chess: Introduction to Europe''.</ref> [[Muslims]] carried Shatranj to [[North Africa]], [[Sicily]], and Spain by the 10th century where it took its final modern form of chess.<ref name=Britannica1/> |

|||

* '''[[Chintz]]''': The origin of Chintz is from the printed all cotton fabric of calico in India.<ref name=eb-chintz>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''chintz''</ref> The origin of the word ''chintz'' itself is from the [[Hindi language]] word चित्र् (chitr), which means a spot.<ref name=eb-chintz/><ref name="Hāṇḍā">Hāṇḍā (1998), page 133</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Crescograph]]''': The crescograph, a device for measuring growth in [[plant]]s, was invented in the early 20th century by the Bengali scientist Sir [[Jagadish Chandra Bose]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.edsanders.com/bose|title=Jagadis Bose Research on Measurement of Plant Growth|accessdate=2008-08-05}}</ref><ref>Geddes, pages 173-176</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Crucible steel]]''': Perhaps as early as 300 BCE—although certainly by 200 CE—high quality steel was being produced in southern India also by what Europeans would later call the crucible technique.<ref name=Juleff>G. Juleff, "An ancient wind powered iron smelting technology in Sri Lanka", ''Nature'' 379 (3), 60–63 (January, 1996)</ref> In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon.<ref name=Juleff/> The first crucible steel was the [[wootz steel]] that originated in India before the beginning of the common era.<ref name=Ranganathan/> Archaeological evidence suggests that this manufacturing process was already in existence in South India well before the Christian era.<ref name=Srinivasan/><ref name=Griffiths/><ref>[http://www.dli.gov.in/rawdataupload/upload/insa/INSA_1/20005b66_263.pdf Indian Journal of History & Science,34(4),1999 (through "Digital Library of India")]</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=|title=A great past in bright colours|url=http://www.frontlineonnet.com/fl2720/stories/20101008272006400.htm|accessdate=|newspaper=Frontline|date=8 October 2010|location=India}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Dock (maritime)]]''': The earliest known docks were not South Asian, but rather those discovered in [[Wadi al-Jarf]], an [[ancient Egypt]]ian [[habor]] dating from 2500 BCE located on the [[Red Sea]] coast.<ref>{{cite news|last=Boyle|first=Alan|title=4,500-year-old harbor structures and papyrus texts unearthed in Egypt|url=http://cosmiclog.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/04/15/17767610-4500-year-old-harbor-structures-and-papyrus-texts-unearthed-in-egypt?lite|newspaper=NBC|date=15 April 2013}}</ref><ref name=Marouard>{{cite journal |last1=Marouard |first1=Gregory |last2=Tallet |first2=Pierre |year=2012 |title=Wadi al-Jarf - An early pharaonic harbour on the Red Sea coast |journal=Egyptian Archaeology |volume=40 |issue= |pages=40–43 |publisher= |doi= |url=http://www.academia.edu/1819574/Wadi_al-Jarf_-_An_early_pharaonic_harbour_on_the_Red_Sea_coast_-_Egyptian_Archaeology_40_2012_p._40-43 |accessdate=18 April 2013}}</ref> A structure at [[Lothal]] (2400 BCE) is considered the earliest Indian dock by some archaeologists, apparently located away from the main current to avoid deposition of silt.<ref name="RaoQ"/> Modern oceanographers have observed that the Harappans must have possessed knowledge relating to tides in order to build such a dock on the ever-shifting course of the [[Sabarmati]], as well as exemplary [[hydrography]] and maritime engineering.<ref name="RaoQ"/> This was the earliest known dock found in the world, equipped to berth and service ships.<ref name="RaoQ">Rao, pages 27–28</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Gujarat built world's first naval dockyard|url=http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-02-25/ahmedabad/28119608_1_dockyard-lothal-harappan-civilisation|accessdate=|newspaper=Times of India|date=25 February 2010|location=Ahmedabad,India}}</ref> It is speculated that Lothal engineers studied tidal movements, and their effects on brick-built structures, since the walls are of kiln-burnt bricks.<ref name="Rao2819"/> This knowledge also enabled them to select Lothal's location in the first place, as the [[Gulf of Khambhat]] has the highest tidal amplitude and ships can be sluiced through flow tides in the river estuary.<ref name="Rao2819">Rao, pages 28–29</ref> However, these speculations have been called into question, as it has been suggested by other archaeologists<ref>http://www.safarmer.com/Indo-Eurasian/Leshnik.pdf</ref> that the supposed dockyard at Lothal was nothing more than an irrigation tank. |

|||

[[File:Cotton dyeing in India.jpg|thumb|200px|Cotton being dyed manually in contemporary India.]] |

|||

* '''[[Incense clock]]''': Although popularly associated with China the incense clock is believed to have originated in India, at least in its fundamental form if not function.<ref name=Schafer161>Schafer (1963), pages 160-161</ref><ref name=Bedini69>Bedini (1994), pages 69–80</ref> Early incense clocks found in China between the 6th and 8th centuries CE—the period it appeared in China all seem to have [[Devanagari|Devanāgarī]] carvings on them instead of Chinese seal characters.<ref name=Schafer161/><ref name=Bedini69/> Incense itself was introduced to China from India in the early centuries CE, along with the spread of Buddhism by travelling monks.<ref name=Bedini25>Bedini (1994), page 25</ref><ref name=Seiwert96>Seiwert (2003), page 96</ref><ref name=Kumar0565>Kumar, Yukteshwar (2005), page 65</ref> [[Edward H. Schafer|Edward Schafer]] asserts that incense clocks were probably an Indian invention, transmitted to China, which explains the Devanāgarī inscriptions on early incense clocks found in China.<ref name=Schafer161/> [[Silvio Bedini]] on the other hand asserts that incense clocks were derived in part from incense seals mentioned in [[Tantric Buddhism|Tantric Buddhist]] scriptures, which first came to light in China after those scriptures from India were translated into Chinese, but holds that the time-telling function of the seal was incorporated by the Chinese.<ref name=Bedini69/> |

|||

* '''[[Indian club]]s''': The Indian club—which appeared in Europe during the 18th century—was used long by India's native soldiery before its introduction to Europe.<ref name=tadd95>Todd, Jan (1995). [http://www.la84foundation.org/SportsLibrary/IGH/IGH0306/IGH0306c.pdf ''From Milo to Milo: A History of Barbells, Dumbells, and Indian Clubs'']. Accessed in September 2008. Hosted on the [[LA84 Foundation|LA84 Foundation Sports Library]].</ref> During the [[British Raj]] the British officers in India performed calisthenic exercises with clubs to keep in for physical conditioning.<ref name=tadd95/> From Britain the use of club swinging spread to the rest of the world.<ref name=tadd95/> |

|||

* '''[[Coherer#Imperfect junction coherer|Iron and mercury coherer]]''': In 1899, the [[Bengali people|Bengali]] physicist Sir [[Jagdish Chandra Bose]] announced the development of an "''iron-mercury-iron coherer with [[telephone]] detector''" in a paper presented at the Royal Society, London.<ref>Bondyopadhyay (1988)</ref> He also later received {{US patent|755840}}, "''Detector for electrical disturbances''" (1904), for a specific [[Electromagnetic radiation|electromagnetic]] receiver. |

|||

* '''[[Kabaddi]]''': The game of ''kabaddi'' originated in India during prehistory.<ref name=Alter88>Alter, page 88</ref> Suggestions on how it evolved into the modern form range from wrestling exercises, military drills, and collective self-defense but most authorities agree that the game existed in some form or the other in India during the period between 1500 and 400 BCE.<ref name=Alter88/> |

|||

* '''[[Ludo (board game)|Ludo]]''': [[Pachisi]] originated in India by the 6th century.<ref name=EncartaP>MSN Encarta (2008). [http://encarta.co.uk/encyclopedia_781530306/Pachisi.html ''Pachisi''].</ref> The earliest evidence of this game in India is the depiction of boards on the caves of Ajanta.<ref name=EncartaP/> This game was played by the [[Mughal empire|Mughal emperors]] of India; a notable example being that of Akbar, who played ''living Pachisi'' using girls from his [[harem]].<ref name=EncartaP/><ref>Stephen M. Edwardes and Herbert Garrett; |

|||

Mughal rule in India, |

|||

Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 1995, 374 pages |

|||

ISBN 81-7156-551-4, ISBN 978-81-7156-551-1 |

|||

From p.288: |

|||

Pachisi, an ancient Hindu game represented in the caves of Ajanta, is said to |

|||

have been played by Akbar on the marble squares of a quadrangle in [[Agra |

|||

fort]] and in the Khas Mahal at [[Fatehpur Sikri]], with young slave girls in |

|||

place of the coloured pieces. |

|||

</ref> A variant of this game, called Ludo, made its way to England during the British Raj.<ref name=EncartaP/> |

|||

* '''[[Muslin]]''': The fabric was named after the city where Europeans first encountered it, [[Mosul]], in what is now [[Iraq]], but the fabric actually originated from [[Dhaka]] in what is now [[Bangladesh]].<ref>[http://banglapedia.search.com.bd/HT/M_0427.htm Muslin], ''[[Banglapedia]]''. [[Asiatic Society of Bangladesh]] (2008)</ref><ref name=Muslin>{{Cite journal|first=S.|last=Ahmad|title=Rise and Decline of the Economy of Bengal|journal=Asian Affairs|volume=27|issue=3|pages=5–26|date=July–September 2005}}</ref> In the 9th century, an [[Islamic economics in the world|Arab merchant]] named Sulaiman makes note of the material's origin in [[Bengal]] (known as ''Ruhml'' in [[Arabic language|Arabic]]).<ref name=Muslin/> |

|||

* '''[[Mysorean rockets]]''': The first iron-cased and metal-cylinder [[rocket]]s were developed by [[Tipu Sultan]], ruler of the South Indian [[Kingdom of Mysore]], and his father [[Hyder Ali]], in the 1780s. He successfully used these iron-cased rockets against the larger forces of the [[British East India Company]] during the [[Anglo-Mysore Wars]]. The Mysore rockets of this period were much more advanced than what the British had seen, chiefly because of the use of iron tubes for holding the propellant; this enabled higher thrust and longer range for the missile (up to 2 km range). After Tipu's eventual defeat in the [[Fourth Anglo-Mysore War]] and the capture of the Mysore iron rockets, they were influential in British rocket development, inspiring the [[Congreve rocket]], and were soon put into use in the [[Napoleonic Wars]].<ref>Roddam Narasimha (1985), [http://nal-ir.nal.res.in/2382/01/tr_pd_du_8503_R66305.pdf Rockets in Mysore and Britain, 1750–1850 A.D.], National Aeronautical Laboratory and Indian Institute of Science</ref><ref name=r&ms>"Hyder Ali, prince of Mysore, developed war rockets with an important change: the use of metal cylinders to contain the combustion powder. Although the hammered soft iron he used was crude, the bursting strength of the container of black powder was much higher than the earlier paper construction. Thus a greater internal pressure was possible, with a resultant greater thrust of the propulsive jet. The rocket body was lashed with leather thongs to a long bamboo stick. Range was perhaps up to three-quarters of a mile (more than a kilometre). Although individually these rockets were not accurate, dispersion error became less important when large numbers were fired rapidly in mass attacks. They were particularly effective against cavalry and were hurled into the air, after lighting, or skimmed along the hard dry ground. Hyder Ali's son, [[Tippu Sultan]], continued to develop and expand the use of rocket weapons, reportedly increasing the number of rocket troops from 1,200 to a corps of 5,000. In battles at [[Seringapatam]] in 1792 and 1799 these rockets were used with considerable effect against the British." - '''Encyclopædia Britannica (2008)'''. ''rocket and missile.''</ref> |

|||

[[File:Sanchi2.jpg|thumb|The Great Stupa at [[Sanchi]] (4th-1st century BCE). The dome shaped stupa was used in India as a commemorative monument associated with storing sacred relics.]] |

|||

* '''[[Palampore]]''': पालमपुर् (Hindi language) of Indian origin<ref name=eb-interior-design>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''interior design''</ref> was imported to the western world—notable England and [[Colonial america]]—from India.<ref name=eb-crewel-work>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''crewel work''</ref><ref name=eb-quilting >Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''quilting''</ref> In 17th-century England these hand painted cotton fabrics influenced native crewel work design.<ref name=eb-crewel-work/> Shipping vessels from India also took palampore to colonial America, where it was used in [[quilting]].<ref name=eb-quilting/> |

|||

* '''[[Prayer flags]]''': The [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] [[sūtra]]s, written on cloth in India, were transmitted to other regions of the world.<ref name=Baker1>Barker, page 13</ref> These sutras, written on banners, were the origin of prayer flags.<ref name=Baker1/> Legend ascribes the origin of the prayer flag to the [[Shakyamuni Buddha]], whose prayers were written on battle flags used by the ''[[Deva (Buddhism)|devas]]'' against their adversaries, the ''[[Asura (Buddhism)|asuras]]''.<ref name=Beer60>Beer, page 60</ref> The legend may have given the Indian ''[[bhikku]]'' a reason for carrying the 'heavenly' banner as a way of signyfying his commitment to ''[[ahimsa]]''.<ref name=wise-11-12>Wise, page 11-12</ref> This knowledge was carried into [[Tibet]] by 800 CE, and the actual flags were introduced no later than 1040 CE, where they were further modified.<ref name=wise-11-12/> The Indian monk [[Atisha]] (980-1054 CE) introduced the Indian practice of printing on cloth prayer flags to Tibet.<ref name=Beer60/> |

|||

* '''[[Prefabricated home]] and movable structure''': The first prefabricated homes and movable structures were invented in 16th-century [[Mughal Empire|Mughal India]] by [[Akbar]]. These structures were reported by Arif Qandahari in 1579.<ref>Irfan Habib (1992), "Akbar and Technology", ''Social Scientist'' '''20''' (9-10): 3-15 [3-4]</ref> |

|||

[[File:Wayang Pandawa.jpg|thumb|[[Wayang]] Kulit (shadow puppet) in Wayang Purwa type, depicting five [[Pandava]], from left to right: [[Bhima]], [[Arjuna]], [[Yudhishtira]], [[Nakula]], and [[Sahadeva]] (Museum Indonesia, [[Jakarta]]). Ghosh, Massey, and Banerjee (2006) trace the origins of puppetry in India to the Indus Civilization.]] |

|||

* '''[[Ruler]]''': Rulers made from Ivory were in use by the Indus Valley Civilization in what today is Pakistan and some parts of Western India prior to 1500 BCE.<ref name=Whitelaw14/> Excavations at Lothal (2400 BCE) have yielded one such ruler calibrated to about 1/16 of an inch—less than 2 [[millimeters]].<ref name=Whitelaw14>Whitelaw, page 14</ref> Ian Whitelaw (2007) holds that 'The Mohenjo-Daro ruler is divided into units corresponding to 1.32 inches (33.5 mm) and these are marked out in decimal subdivisions with amazing accuracy—to within 0.005 of an inch. Ancient bricks found throughout the region have dimensions that correspond to these units.'<ref name=Whitelaw15>Whitelaw, page 15</ref> Shigeo Iwata (2008) further writes 'The minimum division of graduation found in the segment of an ivory-made linear measure excavated in Lothal was 1.79 mm (that corresponds to 1/940 of a fathom), while that of the fragment of a shell-made one from Mohenjo-daro was 6.72 mm (1/250 of a fathom), and that of bronze-made one from Harapa was 9.33 mm (1/180 of a fathom).'<ref name=Iwata2254/> The weights and measures of the Indus civilization also reached Persia and [[Central Asia]], where they were further modified.<ref name=Iwata2254>Iwata, 2254</ref> |

|||

* '''Seamless [[celestial globe]]''': Considered one of the most remarkable feats in [[metallurgy]], it was invented in [[Kashmir]] by Ali Kashmiri ibn Luqman in between 1589 and 1590 CE, and twenty other such [[globe]]s were later produced in [[Lahore]] and Kashmir during the Mughal Empire.<ref name=Kamarustafa48>Kamarustafa (1992), page 48</ref><ref name=Emilie/> Before they were rediscovered in the 1980s, it was believed by modern metallurgists to be technically impossible to produce metal globes without any [[wikt:seam|seams]], even with modern technology.<ref name=Emilie/> These Mughal metallurgists pioneered the method of [[lost-wax casting]] in order to produce these globes.<ref name=Emilie>{{Cite book|first=Emilie|last=Savage-Smith|title=Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their history, Construction, and Use|publisher=Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.|year=1985}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Shampoo]]''': The word ''[[wikt:Shampoo|shampoo]]'' in [[English language|English]] is derived from [[Hindustani language|Hindustani]] ''chāmpo'' (चाँपो {{IPA-hns|tʃãːpoː|}}),<ref>''chāmpo'' (चाँपो {{IPA-hns|tʃãːpoː|}}) is the [[imperative mood|imperative]] of ''chāmpnā'' (चाँपना {{IPA|[tʃãːpnaː]}}), "to smear, knead the muscles, massage the head and hair"</ref> and dates to 1762.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| title = Online Etymology Dictionary |

|||

| url = http://www.etymonline.com/ |

|||

| author = Douglas Harper |

|||

| year = '''65456''' |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-07-14 |

|||

}}</ref> The shampoo itself originated in the eastern regions of the [[Mughal Empire]] that ruled erstwhile [[India]], particularly in the [[Nawab of Bengal]] where it was introduced as a [[shampoo (massage)|head massage]], usually consisting of [[alkali]], natural oils and [[fragrance]]s. Shampoo was first introduced in Britain by a [[Bengali people|Bengali]] entrepreneur from Bihar named [[Sake Dean Mahomet|Sake Dean Mahomed]], he first familiarized the shampoo in Basil Cochrane's vapour baths while working there in the early 19th century. Later, Sake Dean Mahomed together with his Irish wife, opened "Mahomed's Steam and Vapour Sea Water Medicated Baths" in [[Brighton]], [[England]]. His baths were like [[Turkish bath]]s where clients received a treatment of ''champi'' (shampooing). Very soon due to Sake Dean Mahomed fame as a bathing expert he was appointed ‘Shampooing Surgeon’ to both [[George IV of the United Kingdom|George IV]] and [[William IV of the United Kingdom|William IV]].<ref>pp. 148–174, ''The Travels of Dean Mahomet: An Eighteenth-Century Journey Through India'', Sake Deen Mahomet and Michael Herbert Fisher, University of California Press, 1997, ISBN 0-520-20717-3</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Cotton gin|Single roller cotton gin]]''': The [[Ajanta caves]] of India yield evidence of a single roller cotton gin in use by the 5th century.<ref>Angela Lakwete: ''Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America'', The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8018-7394-0, p. 5</ref> This cotton gin was used in India until innovations were made in form of foot powered gins.<ref name=Babergin>Baber (1996), page 56</ref> The cotton gin was invented in India as a mechanical device known as ''charkhi'', more technically the "wooden-worm-worked roller". This mechanical device was, in some parts of India, driven by water power.<ref name=Baber1>Baber (1996), page 57</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Snakes and ladders]]''': Snakes and ladders originated in India as a game based on morality.<ref name=Augustyn>Augustyn, pages 27–28</ref> During British rule of India, this game made its way to England, and was eventually introduced in the United States of America by game-pioneer [[Milton Bradley]] in 1943.<ref name=Augustyn/> |

|||

* '''[[Stepwell]]''': Earliest clear evidence of the origins of the stepwell is found in the Indus Valley Civilization's archaeological site at [[Mohenjodaro]] in Pakistan.<ref name=Livingston&Bach20>Livingston & Beach, 20</ref> The three features of stepwells in the subcontinent are evident from one particular site, abandoned by 2500 BCE, which combines a bathing pool, steps leading down to water, and figures of some religious importance into one structure.<ref name=Livingston&Bach20/> The early centuries immediately before the common era saw the Buddhists and the Jains of India adapt the stepwells into their architecture.<ref name=Livingston&Bach20/> Both the wells and the form of ritual bathing reached other parts of the world with Buddhism.<ref name=Livingston&Bach20/> Rock-cut step wells in the subcontinent date from 200 to 400 CE.<ref name=L&B/> Subsequently the wells at Dhank (550-625 CE) and stepped ponds at [[Bhinmal]] (850-950 CE) were constructed.<ref name=L&B>Livingston & Beach, page xxiii</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Stupa]]''': The origin of the [[stupa]] can be traced to 3rd-century BCE India.<ref name=Ency>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''Pagoda''.</ref> It was used as a commemorative monument associated with storing sacred relics.<ref name=Ency/> The stupa architecture was adopted in [[Southeast Asia|Southeast]] and [[East Asia]], where it evolved into the [[pagoda]], a Buddhist monument used for enshrining sacred relics.<ref name=Ency/> |

|||

* '''[[Suit (cards)|Suits]] game''': Kridapatram is an early [[Suit (cards)|suits]] game, made of painted rags, invented in Ancient India. The term ''kridapatram'' literally means "painted rags for playing."<ref name="McManus">{{cite book|author=James McManus|title=Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=drHJelHmhsgC&pg=PA34|date=27 October 2009|publisher=Macmillan|isbn=978-0-374-29924-8|page=34}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | last = Carlisle| first = Rodney| title = Encyclopedia of Play in Today's Society| publisher = [[SAGE Publications]]| year = 2009| page = 31| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=7DiB3z2fBpAC&pg=PA31| isbn = 978-1-4129-6670-2}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | last = Quackenbos| first = | title = Illustrated History of Ancient Literature, Oriental and Classical| publisher = READ BOOKS| year = 2010| page = 60| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=GzgsRtvtp_gC&pg=PA60| isbn = 978-1-4455-7978-8}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | last = Kapoor| first = Subodh| title = The Indian encyclopaedia: biographical, historical, religious, administrative, ethnological, commercial and scientific - Vol 6| publisher = Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd| year = 2002| page = 1786| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=q5ZM0nZXZEkC&pg=PA1786| isbn = 978-81-7755-257-7}}</ref><ref name="Townsend">{{Citation | last = Townsend| first = George| title = The manual of dates: a dictionary of reference to all the most important events in the history of mankind to be found in authentic records| publisher = Routledge, Warne, & Routledge| year = 1862| page = 184| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=HKQZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA184}}</ref> Paper playing cards first appeared in East Asia during the 9th century.<ref name="McManus"/><ref>{{Cite book | last =Needham | first =Joseph | author-link =Joseph Needham | year =2004 | title =Science & Civilisation in China | publisher =Cambridge University Press | volume =V:1 | isbn =0-521-05802-3|pages=131–132}}</ref> The medieval Indian game of ''ganjifa'', or playing cards, is first recorded in the 16th century.<ref name="Schwartz">{{cite book|author=David G. Schwartz|title=Roll the bones: the history of gambling|date=5 October 2006|publisher=Gotham Books|isbn=978-1-59240-208-3}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Stirrup|Toe stirrup]]''': The earliest known manifestation of the stirrup, which was a toe loop that held the big toe was used in India in as early as 500 BCE<ref name=Chamberlin80>Chamberlin (2007), page 80</ref> or perhaps by 200 BCE according to other sources.<ref name=Hobson103>Hobson (2004), page 103</ref><ref name=woods2p52>Woods & Woods (2000), pages 52–53</ref> This ancient stirrup consisted of a looped rope for the big toe which was at the bottom of a saddle made of fibre or leather.<ref name=woods2p52/> Such a configuration made it suitable for the warm climate of most of India where people used to ride horses barefoot.<ref name=woods2p52/> A pair of megalithic double bent iron bars with curvature at each end, excavated in [[Stone circles of Junapani|Junapani]] in the central Indian state of [[Madhya Pradesh]] have been regarded as stirrups although they could as well be something else.<ref name=EIA336>"16.17.4: Stirrups". ''Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology'' (Vol. 1). Edited by Amalananda Ghosh (1990). page 336</ref> Buddhist carvings in the temples of Sanchi, [[Mathura, Uttar Pradesh|Mathura]] and the [[Bhaja Caves|Bhaja caves]] dating back between the 1st and 2nd century BCE figure horsemen riding with elaborate saddles with feet slipped under girths.<ref name=Azzaroli156>Azzaroli (1985), page 156</ref><ref name=Addington45>Addington (1990), page 45</ref><ref name=Barua17>Barua (2005), pages 16–17</ref> [[John Marshall (archaeologist)|Sir John Marshall]] described the Sanchi relief as "the earliest example by some five centuries of the use of stirrups in any part of the world".<ref name=Barua17/> In the 1st century CE horse riders in northern India, where winters are sometimes long and cold, were recorded to have their booted feet attached to hooked stirrups.<ref name=Hobson103/> However the form, the conception of the primitive Indian stirrup spread west and east, gradually evolving into the stirrup of today.<ref name=woods2p52/><ref name=Addington45/> |

|||

* '''[[Wootz steel]]''': Wootz originated in India before the beginning of the common era.<ref name=Ranganathan>Srinivasan & Ranganathan</ref> Wootz steel was widely exported and traded throughout ancient Europe, China, the Arab world, and became particularly famous in the [[Middle East]], where it became known as [[Damascus steel]]. Archaeological evidence suggests that this manufacturing process was already in existence in South India well before the Christian era they also made trains what were pulled by horses under ground.<ref name=Srinivasan>Srinivasan 1994</ref><ref name=Griffiths>Srinivasan & Griffiths</ref> |

|||

==Discoveries== |

|||

===Agriculture=== |

|||

[[File:Jute plant.gif|thumb|left|Jute plants ''Corchorus olitorius'' and ''Corchorus capsularis'' cultivated first in India.]] |

|||

* '''[[Cashmere wool]]''': The fiber is also known as ''pashm'' or ''pashmina'' for its use in the handmade shawls of Kashmir, India.<ref>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''cashmere''.</ref> The woolen shawls made from wool in [[Kashmir]] region of India find written mention between 3rd century BCE and the 11th century CE.<ref name=ebpasm>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''kashmir shawl''.</ref> However, the founder of the cashmere wool industry is traditionally held to be the 15th-century ruler of Kashmir, ''Zayn-ul-Abidin'', who employed weavers from [[Central Asia]].<ref name=ebpasm/> |

|||

* '''[[Cotton|Cotton cultivation]]''': Cotton was cultivated by the inhabitants of the [[Indus Valley Civilization]] by the [[5th millennium BCE]] - [[4th millennium BCE]].<ref>Stein (1998), page 47</ref> The Indus cotton industry was well developed and some methods used in cotton spinning and fabrication continued to be practiced till the modern Industrialization of India.<ref>Wisseman & Williams (1994), page 127</ref> Well before the [[Common Era]], the use of cotton textiles had spread from India to the [[Mediterranean]] and beyond.<ref>The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. ''cotton''.</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Indigo dye]]''': Indigo, a blue pigment and a dye, was used in India, which was also the earliest major center for its production and processing.<ref name=k&c>Kriger & Connah (2006), page 120</ref> The ''Indigofera tinctoria'' variety of Indigo was domesticated in India.<ref name=k&c/> Indigo, used as a dye, made its way to the [[ancient Greece|Greeks]] and the [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] via various trade routes, and was valued as a luxury product.<ref name=k&c/> |

|||

* '''[[Jute|Jute cultivation]]''': Jute has been cultivated in India since ancient times.<ref name=ebjute/> Raw jute was exported to the [[western world]], where it was used to make [[ropes]] and cordage.<ref name=ebjute>Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''jute''.</ref> The Indian jute industry, in turn, was modernized during the British Raj in India.<ref name=ebjute/> The region of [[Bengal]] was the major center for Jute cultivation, and remained so before the modernization of India's jute industry in 1855, when [[Kolkata]] became a center for jute processing in India.<ref name=ebjute/> |

|||

* '''[[Sugar|Sugar refinement]]''': Sugarcane was originally from tropical [[South Asia]] and [[Southeast Asia]].<ref name=Kiple/> Different species likely originated in different locations with ''S. barberi'' originating in India and ''S. edule'' and ''S. officinarum'' coming from [[New Guinea]].<ref name=Kiple>{{cite web |url=http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/sugar.htm|title=World history of Food - Sugar|author=Kenneth F.Kiple & Kriemhild Conee Ornelas|work= |publisher=Cambridge University Press|accessdate=9 January 2012}}</ref> The process of producing crystallized sugar from sugarcane was discovered by the time of the [[Gupta dynasty|Imperial Guptas]],<ref name=Adas>Adas (2001), page 311</ref> and the earliest reference of candied sugar comes from India.<ref name=Kieschnick1>Kieschnick (2003)</ref> The process was soon transmitted to China with traveling Buddhist monks.<ref name=Kieschnick1/> Chinese documents confirm at least two missions to India, initiated in 647 CE, for obtaining technology for sugar-refining.<ref name=Kieschnick11>Kieschnick (2003), page 258</ref> Each mission returned with results on refining sugar.<ref name=Kieschnick11/> |

|||

===Mathematics=== |

|||

{| class="wikitable Unicode" border="1" style="text-align:left; font-size:100%;" align=right |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Number System |

|||

! colspan=10 | Numbers |

|||

|- |

|||

! 0 || 1 || 2 || 3 || 4 || 5 || 6 || 7 || 8 || 9 |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Gurmukhi |

|||

| o || ੧ || ੨ || ੩ || ੪ || ੫ || ੬ || ੭ || ੮ || ੯ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Oriya |

|||

| ୦ || ୧ || ୨ || ୩ || ୪ || ୫ || ୬ || ୭ || ୮ || ୯ |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="font-size: 75%;" | Bengali |

|||

| ০ || ১ || ২ || ৩ || ৪ || ৫ || ৬ || ৭ || ৮ || ৯ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Devanagari |

|||

| ० || १ || २ || ३ || ४ || ५ || ६ || ७ || ८ || ९ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Gujarati |

|||

| ૦ || ૧ || ૨ || ૩ || ૪ || ૫ || ૬ || ૭ || ૮ || ૯ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Tibetan |

|||

| ༠ || ༡ || ༢ || ༣ || ༤ || ༥ || ༦ || ༧ || ༨ || ༩ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Brahmi |

|||

| || || || || || || || || || |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Telugu |

|||

| ౦ || ౧ || ౨ || ౩ || ౪ || ౫ || ౬ || ౭ || ౮ || ౯ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Kannada |

|||

| ೦ || ೧ || ೨ || ೩ || ೪ || ೫ || ೬ || ೭ || ೮ || ೯ |

|||

<!-- Old Sinhala numerals not in Unicode --> |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Malayalam |

|||

| ൦ || ൧ || ൨ || ൩ || ൪ || ൫ || ൬ || ൭ || ൮ || ൯ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Tamil |

|||

| ೦ || ௧ || ௨ || ௩ || ௪ || ௫ || ௬ || ௭ || ௮ || ௯ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Burmese |

|||

| ၀ || ၁ || ၂ || ၃ || ၄ || ၅ || ၆ || ၇ || ၈ || ၉ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Khmer |

|||

| ០ || ១ || ២ || ៣ || ៤ || ៥ || ៦ || ៧ || ៨ || ៩ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Thai |

|||

| ๐ || ๑ || ๒ || ๓ || ๔ || ๕ || ๖ || ๗ || ๘ || ๙ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Lao |

|||

| ໐ || ໑ || ໒ || ໓ || ໔ || ໕ || ໖ || ໗ || ໘ || ໙ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Balinese |

|||

| ᭐ || ᭑ || ᭒ || ᭓ || ᭔ || ᭕ || ᭖ || ᭗ || ᭘ || ᭙ |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="font-size: 75%;"| Javanese |

|||

| ꧐ || ꧑ || ꧒ || ꧓ || ꧔ || ꧕ || ꧖ || ꧗ || ꧘ || ꧙ |

|||

<!-- No Baybayin numerals? --> |

|||

|} |

|||

[[File:Trig functions on unit circle.PNG|thumb|right|The half-chord version of the sine function was developed by the Indian mathematician [[Aryabhatta]].]] |

|||

[[File:Brahmaguptra's theorem.svg|thumb|Brahmagupta's theorem (598–668) states that ''AF'' = ''FD''.]] |

|||

* '''[[AKS primality test]]''': The AKS primality test is a [[deterministic algorithm|deterministic]] [[primality test|primality-proving]] [[algorithm]] created and published by three [[Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur]] computer scientists, [[Manindra Agrawal]], [[Neeraj Kayal]], and [[Nitin Saxena]] on 6 August 2002 in a paper titled [http://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/users/manindra/algebra/primality_v6.pdf ''PRIMES is in P''].<ref name=CrandallPomerance200>Crandall & Pomerance (2005), pages 200-201</ref><ref name=WeissteinAKSpt>{{MathWorld|urlname=AKSPrimalityTest|title=AKS Primality Test}}</ref> Commenting on the impact of this discovery, [[Paul Leyland]] noted: "One reason for the excitement within the mathematical community is not only does this algorithm settle a long-standing problem, it also does so in a brilliantly simple manner. Everyone is now wondering what else has been similarly overlooked".<ref name=WeissteinAKSpt/><ref name=Crandall03>Crandall & Papadopoulos (2003), page 2</ref> |

|||

* '''Finite Difference [[Interpolation]]''': The Indian mathematician [[Brahmagupta]] presented what is possibly the first instance<ref>{{cite book|last=Van Brummelen|first=Glen|authorlink=Glen Van Brummelen|title=The mathematics of the heavens and the earth: the early history of trigonometry|year=2009|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=9780691129730|pages=329}} (p.111)</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Meijering|first=Erik|title=A Chronology of Interpolation From Ancient Astronomy to Modern Signal and Image Processing|journal=Proceedings of the IEEE|date=March 2002|volume=90|issue=3|pages=319–342|accessdate=27 October 2010|doi=10.1109/5.993400}}</ref> of finite difference interpolation around 665 CE.<ref name="Gupta">{{cite journal|last=Gupta|first=R. C. |title=Second-order interpolation in Indian mathematics upto the fifteenth century|journal=Indian Journal of History of Science|volume=4|issue=1 & 2|pages=86–98}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Algebra|Algebraic abbreviations]]''': The mathematician [[Brahmagupta]] had begun using abbreviations for unknowns by the 7th century.<ref name=Bell96/> He employed abbreviations for multiple unknowns occurring in one complex problem.<ref name=Bell96/> Brahmagupta also used abbreviations for [[square roots]] and [[cube roots]].<ref name=Bell96/> |

|||

* '''[[Basu's theorem]]''': The Basu's theorem, a result of [[Debabrata Basu]] (1955) states that any complete sufficient statistic is independent of any ancillary statistic.<ref name=Nitis325>Nitis (2000), page 325</ref><ref name=Boos1>Boos & Oliver (1998)</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Brahmagupta–Fibonacci identity]], [[Brahmagupta formula]], [[Brahmagupta matrix]], and [[Brahmagupta theorem]]''': Discovered by the Indian mathematician, Brahmagupta (598–668 CE).<ref name=Plofker419-436>Plofker (2007), pages 419 - 436</ref><ref name=Joseph306>Joseph (2000), page 306</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://jwilson.coe.uga.edu/EMT725/Class/Brooks/Brahmagupta/Brahmagupta.html|title=Brahmagupta's Formula|author=Kala Fischbein, Tammy Brooks|work= |publisher=University of Georgia|accessdate=3 November 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://mathworld.wolfram.com/BrahmaguptaMatrix.html|title=Brahmagupta Matrix|author=Weisstein, Eric W|work= |publisher=Mathworld|accessdate=3 November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Chakravala method]]''': The Chakravala method, a cyclic algorithm to solve [[Indeterminate equation|indeterminate]] [[quadratic equation]]s is commonly attributed to [[Bhāskara II]], (c. 1114–1185 CE)<ref name=SBI200>"Bhaskaracharya II". ''Students’ Encyclopedia India'' (2000). (Volume 1: Adb Allah ibn al Abbas – Cypress). p. 200. ISBN 0-85229-760-2</ref><ref name=Kumar23>Kumar (2004), page 23</ref><ref name=Singh05-385>Singh, Manpal (2005), page 385</ref> although some attribute it to [[Jayadeva (mathematician)|Jayadeva]] (c. 950~1000 CE).<ref name=Plofker474>Plofker (2007), page 474</ref> Jayadeva pointed out that Brahmagupta’s approach to solving equations of this type would yield infinitely large number of solutions, to which he then described a general method of solving such equations.<ref name=Goonatilake127>Goonatilake (1998), page 127 – 128</ref> Jayadeva's method was later refined by Bhāskara II in his ''[[Bijaganita]]'' treatise to be known as the Chakravala method, ''[[chakra]]'' (derived from ''cakraṃ'' चक्रं) meaning 'wheel' in [[Sanskrit]], relevant to the cyclic nature of the algorithm.<ref name= Goonatilake127/><ref name=Baber34>Baber (1996), page 34</ref> With reference to the Chakravala method, E. O. Selenuis held that no European performances at the time of Bhāskara, nor much later, came up to its marvellous height of mathematical complexity.<ref name=SBI200/><ref name= Goonatilake127/><ref name=RaoKA252>Rao K. A. (2000), page 252</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Hindu-Arabic numerals|Hindu number system]]''': With [[decimal]] place-value and a symbol for zero, this system was the ancestor of the widely-used [[Arabic numeral]] system. It was developed in the Indian subcontinent between the 1st and 6th centuries CE.<ref>http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/HistTopics/Indian_numerals.html</ref><ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=El4-AQAAIAAJ&&pg=PA61</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Fibonacci numbers]]''': This sequence was first described by [[Virahanka]] (c. 700 AD), [[Gopāla]] (c. 1135), and [[Hemachandra]] (c. 1150),<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=SI5ip95BbgEC&pg=PA126</ref> as an outgrowth of the earlier writings on Sanskrit prosody by [[Pingala]] (c. 200 BC). |

|||

* '''[[0 (number)|Zero]]''', symbol: Indians were the first to use the zero as a symbol and in arithmetic operations, although Babylonians used zero to signify the 'absent'.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/about/zero.jsp|title=The History of Zero|author=Nils-Bertil Wallin|date=19 November 2002|work= |publisher=Yale Center for the Study of Globalization|accessdate=26 December 2011}}</ref> In those earlier times a blank space was used to denote zero, later when it created confusion a dot was used to denote zero(could be found in [[Bakhshali manuscript]]).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://home.ubalt.edu/ntsbarsh/zero/zero.htm|title=Zero in Four Dimensions|author=Dr. Hossein Arsham|work= |publisher=University of Baltimore|accessdate=26 December 2011}}</ref> In 500 AD circa [[Aryabhata]] again gave a new symbol for zero (''0''). |

|||

* '''Law of signs in multiplication''': The earliest use of notation for negative numbers, as [[subtrahend]], is credited by scholars to the Chinese, dating back to the 2nd century BC.<ref name=Smith>Smith (1958), page 257</ref> Like the Chinese, the Indians used negative numbers as subtrahend, but were the first to establish the "law of signs" with regards to the multiplication of positive and negative numbers, which did not appear in Chinese texts until 1299.<ref name=Smith>Smith (1958), page 258</ref> Indian mathematicians were aware of negative numbers by the 7th century,<ref name=Smith>Smith (1958), page 258</ref> and their role in mathematical problems of debt was understood.<ref name=bourbaki49>Bourbaki (1998), page 49</ref> Mostly consistent and correct rules for working with negative numbers were formulated,<ref name=ebcal>Britannica Concise Encyclopedia (2007). ''algebra''</ref> and the diffusion of these rules led the Arab intermediaries to pass it on to Europe.<ref name=bourbaki49/> |

|||

* '''[[Madhava series]]''': The infinite series for π and for the trigonometric [[sine]], [[cosine]], and [[arctangent]] is now attributed to Madhava of Sangamagrama (c. 1340–1425) and his Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.<ref name=Goonatilake37>Goonatilake (1998), page 37</ref><ref name=Amma182>Amma (1999), pages 182 - 183</ref> He made use of the series expansion of <math>\arctan x</math> to obtain an infinite series expression for π.<ref name=Goonatilake37/> Their rational approximation of the ''error'' for the finite sum of their series are of particular interest. They manipulated the error term to derive a faster converging series for π.<ref name=roy>Roy (1990)</ref> They used the improved series to derive a rational expression,<ref name=roy/><math>104348/33215</math> for π correct up to eleven decimal places, ''i.e.'' <math>3.14159265359</math>.<ref name=Borwein107>Borwein (2004), page 107</ref><ref name=Plofker481>Plofker (2007), page 481</ref> Madhava of Sangamagrama and his successors at the [[Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics]] used geometric methods to derive large sum approximations for sine, cosin, and arttangent. They found a number of special cases of series later derived by Brook Taylor series. They also found the second-order Taylor approximations for these functions, and the third-order Taylor approximation for sine.<ref name=bressoud>Bressoud (2002)</ref><ref name=Plofker>Plofker (2001)</ref><ref name=katz>Katz (1995)</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Pascal's triangle]]''': Described in the 6th century CE by [[Varahamihira]]<ref name="www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk">http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Varahamihira.html</ref> and in the 10th century by [[Halayudha]],<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=sx-EkudWKTcC&pg=PA201</ref> commenting on an obscure reference by [[Pingala]] (the author of an earlier work on prosody) to the "Meru-prastaara", or the "Staircase of Mount Meru", in relation to binomial coefficients. (It was also independently discovered in the 10th or 11th century in Persia and China.) |

|||

* '''[[Pell's equation]], integral solution for''': About a thousand years before [[John Pell|Pell's]] time, Indian scholar Brahmagupta (598–668 CE) was able to find integral solutions to ''vargaprakṛiti'' (Pell's equation):<ref name=Pswamy416>Puttaswamy (2000), page 416</ref><ref name=sw101>Stillwell (2004), pages 72–73</ref> <math>\ x^2-Ny^2=1, </math> where ''N'' is a nonsquare integer, in his [[Brahmasphutasiddhanta|''Brâhma-sphuṭa-siddhânta'']] treatise.<ref name=sw101/> |

|||

* '''[[Ramanujan theta function]], [[Ramanujan prime]], [[Ramanujan summation]], [[Ramanujan graph]] and [[Ramanujan's sum]]''': Discovered by the Indian mathematician [[Srinivasa Ramanujan]] in the early 20th century.<ref>Berndt & Rankin (2001)</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Shrikhande graph]]''': [[Graph (mathematics)|Graph]] invented by the Indian mathematician S.S. Shrikhande in 1959. |

|||

* '''[[Sign convention]]''': Symbols, signs and mathematical notation were employed in an early form in India by the 6th century when the mathematician-astronomer Aryabhata recommended the use of letters to represent unknown quantities.<ref name=Bell96>Bell (1992), page 96</ref> By the 7th century Brahmagupta had already begun using abbreviations for unknowns, even for multiple unknowns occurring in one complex problem.<ref name=Bell96/> Brahmagupta also managed to use abbreviations for square roots and cube roots.<ref name=Bell96/> By the 7th century fractions were written in a manner similar to the modern times, except for the bar separating the [[numerator]] and the [[denominator]].<ref name=Bell96/> A dot symbol for [[negative numbers]] was also employed.<ref name=Bell96/> The [[Bakhshali Manuscript]] displays a cross, much like the modern '+' sign, except that it symbolized subtraction when written just after the number affected.<ref name=Bell96/> The '=' sign for equality did not exist.<ref name=Bell96/> Indian mathematics was transmitted to the Islamic world where this notation was seldom accepted initially and the scribes continued to write mathematics in full and without symbols.<ref name=Bell97>Bell (1992), page 97</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Trigonometric function]]s''' (adapted from Greek): * '''[[Trigonometric function]]s''' (adapted from Greek): The [[Trigonometry|trigonometric]] functions ''sine'' and ''versine'' originated in [[Indian astronomy]], adapted from the full-chord Greek versions (to the modern half-chord versions). They were described in detail by [[Aryabhata]] in the late 5th century, but were likely developed earlier in the [[Pancha-Siddhantika|Siddhantas]], astronomical treatises of the 3rd or 4th century.<ref name=Pingree1>Pingree (2003): {{quote|"Geometry, and its branch trigonometry, was the mathematics Indian astronomers used most frequently. In fact, the Indian astronomers in the third or fourth century, using a pre-Ptolemaic Greek table of chords, produced tables of sines and versines, from which it was trivial to derive cosines. This new system of trigonometry, produced in India, was transmitted to the Arabs in the late eighth century and by them, in an expanded form, to the Latin West and the Byzantine East in the twelfth century."}}</ref><ref name=MactutorTrigo>J. J. O'Connor and E.F. Robertson (1996). [http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/Trigonometric_functions.html Trigonometric functions]. [[MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive]]</ref> Later, the 6th-century astronomer [[Varahamihira]] discovered a few basic trigonometric formulas and identities, such as sin^2(x) + cos^2(x) = 1.<ref name="www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk"/> |

|||

===Medicine=== |

|||

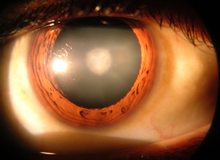

[[File:Cataract in human eye.png|thumb|Cataract in the [[Human Eye]]—magnified view seen on examination with a [[slit lamp]]. Indian surgeon [[Susruta]] performed cataract surgery by the 6th century BCE.]] |

|||

[[File:Amastigotes in a chorionic villus.jpg|thumb|Amastigotes in a chorionic villus. [[Upendranath Brahmachari]] (19 December 1873–February 6, 1946) discovered Urea Stibamine, a treatment which helped nearly eradicate Visceral leishmaniasis.]] |

|||

* '''[[Ayurveda|Ayurvedic]]''' and '''[[Siddha medicine]]''': Ayurveda and Siddha are ancient and traditional systems of medicine. Ayurveda dates back to Iron Age India<ref name="Chopra75">{{Harvnb|Chopra|2003|p=75}}</ref> (1st millennium BC) and still practiced today as a form of [[complementary and alternative medicine]]. It means "knowledge for longevity".<ref name="Chopra75" /> Siddha medicine is mostly prevalent in South India. Herbs and minerals are basic raw materials of the Siddha system which dates back to the period of siddha saints around 5th century BC.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/1023/1/IJTK%206%284%29%20%282007%29%20678-686.pdf|title=Herbs used in Siddha medicine for arthritis - A review|author= |date=October 2007|work=|publisher=Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge|accessdate=10 November 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://indianmedicine.nic.in/index3.asp?sslid=192&subsublinkid=37&lang=1|title=Siddha - Introduction and Origin|author= |work= |publisher=Department of Ayush, Government of India|accessdate=10 November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Cataract surgery]]''': Cataract surgery was known to the Indian physician Sushruta (6th century BCE).<ref name=finger66/> In India, cataract surgery was performed with a special tool called the ''Jabamukhi Salaka'', a curved needle used to loosen the lens and push the cataract out of the field of vision.<ref name=finger66/> The eye would later be soaked with warm butter and then bandaged.<ref name=finger66/> Though this method was successful, Susruta cautioned that cataract surgery should only be performed when absolutely necessary.<ref name=finger66/> Greek philosophers and scientists traveled to India where these surgeries were performed by physicians.<ref name=finger66>Finger (2001), page 66</ref> The removal of cataract by surgery was also introduced into China from India.<ref>Lade & Svoboda (2000), page 85</ref> |

|||

* '''Cure for [[Leprosy]]''': Kearns & Nash (2008) state that the first mention of leprosy is described in the Indian medical treatise ''[[Sushruta Samhita]]'' (6th century BCE).<ref name=k&n08>Kearns & Nash (2008)</ref> However, ''The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine'' holds that the mention of leprosy, as well as ritualistic cures for it, were described in the ''[[Atharva-veda]]'' (1500–1200 BCE), written before the ''Sushruta Samhita''.<ref>Lock; Last & Dunea (2001), page 420</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Plastic surgery]]''': Plastic surgery was being carried out in India by 2000 BCE.<ref name=EP>MSN Encarta (2008). [http://www.encarta.es/encyclopedia_761577922/Plastic_Surgery.html ''Plastic Surgery''].</ref> The system of punishment by deforming a miscreant's body may have led to an increase in demand for this practice.<ref name=EP/> The surgeon [[Sushruta]] contributed mainly to the field of plastic and cataract surgery.<ref name=Dwivedi&Dwivedi07>Dwivedi & Dwivedi 2007</ref> The medical works of both Sushruta and [[Caraka Samhita|Charak]] were translated into Arabic language during the [[Abbasid Caliphate]] (750 CE).<ref name="Lock607"/> These translated Arabic works made their way into Europe via intermediaries.<ref name=Lock607/> In [[Italy]] the Branca family of [[Sicily]] and Gaspare Tagliacozzi of Bologna became familiar with the techniques of Sushruta.<ref name=Lock607>Lock etc., page 607</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Calculus (medicine)|Lithiasis treatment]]''': The earliest operation for treating lithiasis, or the formations of stones in the body, is also given in the ''Sushruta Samhita'' (6th century BCE).<ref name=Lock836/> The operation involved exposure and going up through the floor of the bladder.<ref name=Lock836>Lock; Last & Dunea (2001), page 836</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Visceral leishmaniasis|Visceral leishmaniasis, treatment of]]''': The Indian (Bengali) medical practitioner '''Upendra Nath Brahmachari''' (19 December 1873 – 6 February 1946) was nominated for the [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] in 1929 for his discovery of 'ureastibamine ([[antimony|antimonial]] [[Chemical compound|compound]] for treatment of [[kala azar]]) and a new disease, post-kalaazar dermal leishmanoid.'<ref name=nobel_foundation_UPB>[[Nobel Foundation]] (2008). [http://nobelprize.org/nomination/medicine/nomination.php?action=show&showid=2791 ''The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1901–1951'']</ref> Brahmachari's cure for Visceral leishmaniasis was the urea salt of para-amino-phenyl stibnic acid which he called Urea Stibamine.<ref name=Vigyan_prasar_UNB>[http://www.vigyanprasar.gov.in/scientists/UNBrahmachari.htm ''Upendra Nath Brahmachari: A Pioneer of Modern Medicine in India'']. Vigyan Prasar: Government of India</ref> Following the discovery of Urea Stibamine, Visceral leishmaniasis was largely eradicated from the world, except for some underdeveloped regions.<ref name=Vigyan_prasar_UNB/> |

|||

===Mining=== |

|||

* '''[[Diamond (gemstone)|Diamond mining]] and diamond tools''': Diamonds were first recognized and mined in central India,<ref name=Dickinson1/><ref name=Hershey22>Hershey (2004), page 22</ref><ref name=Malkin12>Malkin (1996), page 12</ref> where significant alluvial deposits of the stone could then be found along the rivers [[Penner River|Penner]], [[Krishna River|Krishna]] and [[Godavari River|Godavari]]. It is unclear when diamonds were first mined in India, although estimated to be at least 5,000 years ago.<ref name=Hershey3,22>Hershey (2004), pages 3 & 23</ref> India remained the world's only source of diamonds until the discovery of diamonds in Brazil in 18th century.<ref name=Thomas46>Thomas (2007), page 46</ref><ref name=Read17>Read (2005), page 17</ref><ref name=lee1>Lee, page 685</ref> [[Golconda]] served as an important centre for diamonds in [[central India]].<ref name=Wenk1>Wenk, pages 535-539</ref> Diamonds then were exported to other parts of the world, including [[Europe]].<ref name=Wenk1/> Early references to diamonds in India come from [[Sanskrit]] texts.<ref name=Encarta11>MSN Encarta (2007). [http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761557986/Diamond.html ''Diamond'']. [http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1257037502695777 Archived] 2009-11-01.</ref> The ''[[Arthashastra]]'' of [[Kautilya]] mentions diamond trade in India.<ref name=lee1/> [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] works dating from the 4th century BCE mention it as a well-known and precious stone but don't mention the details of diamond cutting.<ref name=Dickinson1/> Another Indian description written at the beginning of the 3rd century describes strength, regularity, brilliance, ability to scratch metals, and good refractive properties as the desirable qualities of a diamond.<ref name=Dickinson1>Dickinson, pages 1–3</ref> A Chinese work from the 3rd century BCE mentions: "Foreigners wear it [diamond] in the belief that it can ward off evil influences".<ref name=Dickinson1/> The Chinese, who did not find diamonds in their country, initially used diamonds as a "jade cutting knife" instead of as a jewel.<ref name=Dickinson1/> |

|||

* '''[[Zinc mining]] and [[Zinc#Ancient use|medicinal zinc]]''': Zinc was first smelted from zinc ore in India.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.australianminesatlas.gov.au/education/fact_sheets/zinc.jsp |title=Zinc-Fact sheet |author= |work= |publisher=Australian mines |accessdate=4 November 2011}}</ref> Zinc mines of Zawar, near [[Udaipur]], [[Rajasthan]], were active during early Christian era.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/def_en/articles/metallurg_heritage_india/metallurgical_heritage_india.html |title=Mettalurgical heritage of India|author=Srinivasan, Ranganathan|work= |publisher=Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel |accessdate=4 November 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dli.gov.in/rawdataupload/upload/insa/INSA_1/20005afd_33.pdf|title=Smelting furnaces in Ancient India|author=Rina Shrivastva|year=1999|work= |publisher=Indian Journal of History & Science,34(1), Digital Library of India|accessdate=4 November 2011}}</ref> There are references of medicinal uses of zinc in the [[Charaka Samhita]] (300 BCE).<ref name=Craddock>Craddock (1983)</ref> The [[Rasaratna Samuccaya]] which dates back to the Tantric period (c. 5th - 13th century CE) explains the existence of two types of ores for zinc metal, one of which is ideal for metal extraction while the other is used for medicinal purpose.<ref name=Craddock/><ref name=Biswas11>Biswas (1986), page 11</ref> |

|||

===Sciences=== |

|||

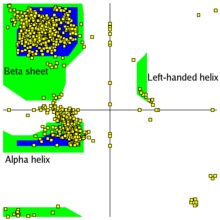

[[File:Ammonium Nitrite 3D.JPG|thumb|Bengali Chemist [[Prafulla Chandra Roy]] synthesized NH<sub>4</sub>NO<sub>2</sub> in its pure form.]] [[File:Ramaplot.png|thumb|A [[Ramachandran plot]] generated from the protein [[PCNA]], a human [[DNA clamp]] [[protein]] that is composed of both [[beta sheet]]s and [[alpha helix|alpha helices]] ([[Protein Data Bank|PDB]] ID 1AXC). Points that lie on the axes indicate [[N-terminus|N-]] and [[C-terminus|C-terminal]] residues for each subunit. The green regions show possible angle formations that include [[Glycine]], while the blue areas are for formations that don't include Glycine.]] |

|||

* '''[[Ammonium nitrite|Ammonium nitrite, synthesis in pure form]]''': '''[[Prafulla Chandra Roy]]''' synthesized NH<sub>4</sub>NO<sub>2</sub> in its pure form, and became the first scientist to have done so.<ref name=vigyanprasar_pcray/> Prior to Ray’s synthesis of Ammonium nitrite it was thought that the compound undergoes rapid thermal decomposition releasing nitrogen and water in the process.<ref name=vigyanprasar_pcray/> |

|||

* '''[[Ashtekar variables]]''': In theoretical physics, Ashtekar (new) variables, named after [[Abhay Ashtekar]] who invented them, represent an unusual way to rewrite the metric on the three-dimensional spatial slices in terms of a [[SU(2)]] [[gauge field]] and its complementary variable. Ashtekar variables are the key building block of [[loop quantum gravity]]. |

|||

* '''Bhatnagar-Mathur Magnetic Interference Balance''': Invented jointly by [[Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar]] and K.N. Mathur in 1928, the so-called 'Bhatnagar-Mathur Magnetic Interference Balance' was a modern instrument used for measuring various magnetic properties.<ref name=Vigyan_prasar_Shanti_Swaryp/> The first appearance of this instrument in Europe was at a [[Royal Society]] exhibition in [[London]], where it was later marketed by British firm Messers Adam Hilger and Co, London.<ref name=Vigyan_prasar_Shanti_Swaryp>[http://www.vigyanprasar.gov.in/scientists/ssbhatnagar/ShantiSwarupBhatnagar.htm ''Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar'']. Vigyan Prasar: Government of India.</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Bhabha scattering]]''': In 1935, Indian nuclear physicist [[Homi J. Bhabha]] published a paper in the ''[[Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences|Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series A]]'', in which he performed the first calculation to determine the cross section of electron-positron scattering.<ref name="Penneyp39"/> Electron-positron scattering was later named Bhabha scattering, in honor of his contributions in the field.<ref name="Penneyp39">Penney (1967), page 39</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Bose–Einstein statistics]], [[Bose–Einstein condensate|condensate]] and [[Boson]]''': On 4 June 1924 the Bengali professor of Physics [[Satyendra Nath Bose]] mailed a short manuscript to [[Albert Einstein]] entitled [http://www.ias.ac.in/jarch/jaa/15/3-7.pdf ''Planck's Law and the Light Quantum Hypothesis''] seeking Einstein's influence to get it published after it was rejected by the prestigious journal ''[[Philosophical Magazine]]''.<ref name=Rigden143>Rigden (2005), pages 143-144</ref> The paper introduced what is today called ''Bose statistics'', which showed how it could be used to derive the Planck blackbody spectrum from the assumption that light was made of [[photons]].<ref name=Rigden143/><ref name=Fraser238>Fraser (2006), page 238</ref> Einstein, recognizing the importance of the paper translated it into German himself and submitted it on Bose's behalf to the prestigious ''[[Zeitschrift für Physik]]''.<ref name=Rigden143/><ref name=Fraser238/> Einstein later applied Bose's principles on particles with mass and quickly predicted the ''Bose-Einstein condensate''.<ref name=Fraser238/><ref name=Dauxois297>Dauxois & Peyrard (2006), pages 297-298</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Chandrasekhar limit]] and [[Chandrasekhar number]]''': Discovered by and named after [[Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar]], who received the [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] in 1983 for his work on [[stellar structure]] and [[stellar evolution]].<ref>{{MacTutor|id=Chandrasekhar|title=Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar|date=February 2005}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Galena|Galena, applied use in electronics of]]''': Bengali scientist Sir [[Jagadish Chandra Bose]] effectively used Galena crystals for constructing radio receivers.<ref name=tifr>[http://www.tifr.res.in/~outreach/biographies/scientists.pdf "Indian Scientists"] (November 2004), Science Popularisation and Public Outreach Committee, [[Tata Institute of Fundamental Research]].</ref> The Galena receivers of Bose were used to receive signals consisting of [[shortwave]], [[white light]] and [[ultraviolet light]].<ref name=tifr/> In 1904 Bose patented the use of Galena Detector which he called ''Point Contact Diode using Galena''.<ref name=Sarkar94>Sarkar (2006), page 94</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Mahalanobis distance]]''': Introduced in 1936 by the Indian (Bengali) statistician [[Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis]] (29 June 1893–June 28, 1972), this distance measure, based upon the correlation between variables, is used to identify and analyze differing pattern with respect to one base.<ref>Taguchi & Jugulum (2002), pages 6–7</ref> |

|||

* '''Kosambi-Karhunen-Loève theorem''': Also known as the [[Karhunen–Loève theorem]]. The Kosambi-Karhunen-Loève theorem is a representation of a stochastic process as an infinite linear combination of [[orthogonal function]]s, analogous to a [[Fourier series]] representation of a function on a bounded interval. Stochastic processes given by infinite series of this form were first<ref name="Raju">{{Citation |first=C.K. |last=Raju |title=Kosambi the Mathematician |journal=Economic and Political Weekly |volume=44 |year=2009 |issue=20 |pages=33–45 }}</ref> considered by [[Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi]].<ref name="Kosambi">{{Citation |first=D. D. |last=Kosambi |title=Statistics in Function Space |journal=Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society |volume=7 |year=1943 |issue= |pages=76–88 |id={{MathSciNet|9816}} }}.</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Nitrite|Mercurous Nitrite]]''': The compound mercurous nitrite was discovered in 1896 by the Bengali chemist Prafulla Chandra Roy, who published his findings in the ''[[Asiatic Society|Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal]]''.<ref name=vigyanprasar_pcray>[http://www.vigyanprasar.gov.in/scientists/pcray/PCRay.htm "Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray"], Viyan Prasar, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.</ref> The discovery contributed as a base for significant future research in the field of chemistry.<ref name=vigyanprasar_pcray/> |

|||

* '''[[Ramachandran plot]], Ramachandran map, and Ramachandran angles''': The Ramachandran plot and Ramachandran map were developed by [[Gopalasamudram Narayana Iyer Ramachandran]], who published his results in the ''[[Journal of Molecular Biology]]'' in 1963. He also developed the Ramachandran angles, which serve as a convenient tool for [[communication]], representation, and various kinds of [[data analysis]].<ref name=Ramakrishnan>Ramakrishnan (2001)</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Raman effect]]''': The Encyclopædia Britannica (2008) reports: "change in the wavelength of light that occurs when a light beam is deflected by molecules. The phenomenon is named for [[Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman]], who discovered it in 1928. When a beam of light traverses a dust-free, transparent sample of a chemical compound, a small fraction of the light emerges in directions other than that of the incident (incoming) beam. Most of this scattered light is of unchanged wavelength. A small part, however, has wavelengths different from that of the incident light; its presence is a result of the Raman effect."<ref>"Raman effect".''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (2008)</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Raychaudhuri equation]]''': Discovered by the [[Bengali people|Bengali]] physicist [[Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri]] in 1954. This was a key ingredient of the [[Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems]] of [[general relativity]].<ref>Naresh (2005)</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Saha ionization equation]]''': The Saha equation, derived by the Bengali scientist [[Meghnad Saha]] (6 October 1893 – 16 February 1956) in 1920, conceptualizes [[ionization]]s in context of stellar atmospheres.<ref>Narlikar (2002), page 188</ref> |

|||

==Innovations== |

|||

* '''[[History of ferrous metallurgy|Iron working]]''': Iron works were developed in the [[Vedic period]] of India, around the same time as, but independently of, [[Anatolia]] and the [[Caucasus]]. Archaeological sites in India, such as [[Malhar]], Dadupur, Raja Nala Ka Tila and Lahuradewa in present day [[Uttar Pradesh]] show iron implements in the period between 1800 BCE—1200 BCE.<ref name=Tewari>[http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/tewari/tewari.pdf The origins of Iron Working in India: New evidence from the Central Ganga plain and the Eastern Vindhyas by Rakesh Tewari (Director, U.P. State Archaeological Department)]</ref> Early iron objects found in India can be dated to 1400 BCE by employing the method of [[radiocarbon dating]]. [[Nail (fastener)|Spikes]], [[knife|knives]], [[dagger]]s, [[arrow]]-heads, [[bowl (vessel)|bowls]], [[spoon]]s, [[saucepan]]s, [[axe]]s, [[chisel]]s, tongs, door fittings etc. ranging from 600 BCE to 200 BCE have been discovered from several archaeological sites of India.<ref name=Ceccarelli>Marco Ceccarelli (2000). ''International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms: Proceedings HMM Symposium''. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-6372-8. pp 218</ref> Some scholars believe that by the early 13th century BC, iron smelting was practiced on a bigger scale in India, suggesting that the date the technology's inception may be placed earlier.<ref name=Tewari/> In [[Southern India]] (present day [[Mysore]]) iron appeared as early as 11th to 12th centuries BC; these developments were too early for any significant close contact with the northwest of the country.<ref name=UCP>I. M. Drakonoff (1991). ''Early Antiquity''. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14465-8. pp 372</ref> In the time of [[Chandragupta II]] Vikramaditya (375–413 CE), corrosion-resistant iron was used to erect the [[Iron pillar of Delhi]], which has withstood corrosion for over 1,600 years.<ref>R. Balasubramaniam (2000), [http://home.iitk.ac.in/%7Ebala/journalpaper/journal/journalpaper_17.pdf On the Corrosion Resistance of the Delhi Iron Pillar], ''Corrosion Science'' '''42''': 2103-29</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Nalanda University]] |

|||

* [[History of science and technology in India]] |

|||

* [[Timeline of historic inventions]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

'''A''' |

|||

* Adas, Michael (January 2001). ''Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History''. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-832-0. |

|||

* Addington, Larry H. (1990). ''The Patterns of War Through the Eighteenth Century'' (Illustrated edition). Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20551-4. |

|||

* Alter, J. S. in "Kabaddi, a national sport of India". Dyck, Noel (2000). ''Games, Sports and Cultures''. Berg Publishers: ISBN 1-85973-317-4. |

|||

* [[T.A. Sarasvati Amma|Amma, T. A. Sarasvati]] (1999) [1979]. ''Geometry in Ancient and Medieval India''. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publication. ISBN 81-208-1344-8. |

|||

* Arensberg, Conrad M. & Niehoff, Arthur H. (1971). ''Introducing Social Change: A Manual for Community Development'' (second edition). New Jersey: Aldine Transaction. ISBN 0-202-01072-4 |

|||

* Augustyn, Frederick J. (2004). ''Dictionary of toys and games in American popular culture''. Haworth Press. ISBN 0-7890-1504-8. |

|||

* Azzaroli, Augusto (1985). ''An Early History of Horsemanship''. Massachusetts: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-07233-0. |

|||

'''B''' |

|||

* Baber, Zaheer (1996). ''The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India''. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-2919-9. |

|||

* Bag, A. K. (2005). "Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu", ''Indian Journal of History of Science'' '''40''' (3): 431-6. |

|||

* Balasubramaniam, R. (2002). ''Delhi Iron Pillar: New Insights''. Delhi: Indian Institute of Advanced Studies [University of Michigan]. ISBN 81-7305-223-9. |

|||

* Banerji, Sures Chandra (1989). ''A Companion to Sanskrit Literature''. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0063-X. |

|||

* Barker, Dian (2003). ''Tibetan Prayer Flags''. Connections Book Publishing. ISBN 1-85906-106-0. |

|||

* Barua, Pradeep (2005). ''The State at War in South Asia''. [[Nebraska]]: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1. |

|||

* [[Arthur Llewellyn Basham|Basham, A. L.]] (2001) [1967]. ''[[The Wonder That was India]]''. Third revised edition. New Delhi: Rupa & co. ISBN 0-283-99257-3. |

|||

* [[Silvio Bedini|Bedini, Silvio A.]] (1994). ''The Trail of Time : Time Measurement with Incense in East Asia''. England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37482-0. |

|||

* Bell, Eric Temple (1992). ''The Development of Mathematics'' (originally published in 1945). Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-27239-7. |

|||

* Bell, John (2000). ''Strings, Hands, Shadows: A Modern Puppet History''. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-89558-156-6. |

|||

* Beer, Robert (2004). ''Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs''. Serindia Publications Inc. ISBN 1-932476-10-5. |

|||

* [[Henry Bird (chess player)|Bird, Henry Edward]] (1893). ''Chess History and Reminiscences''. London. (Republished version by Forgotten Books). ISBN 1-60620-897-7. |

|||

* {{cite book |title=Ramanujan: Essays and Surveys|last= Berndt|first=Bruce C. |last2= Rankin |first2= Robert Alexander |year=2001 |publisher=American Mathematical Society |location=Rhode Island |isbn=0-8218-2624-7}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last=Biswas |first=Arun Kumar |date=June 1986 |title=Rasa-Ratna-Samuccaya and Mineral Processing State-of-Art in the 13th Century A.D. India |journal= Indian Journal of History of Science |volume= 22 (1) |issue= 29-46, 1987 |url= http://www.new.dli.ernet.in/rawdataupload/upload/insa/INSA_1/20005abf_29.pdf |accessdate=2009-01-09}} |

|||

* Blechynden, Kathleen (1905). ''Calcutta, Past and Present''. Los Angeles: University of California. |

|||

* Bondyopadhyay, Probir K (1988). "''Sir J. C. Bose's Diode Detector Received Marconi's First Transatlantic Wireless Signal Of December 1901 (The "Italian Navy Coherer" Scandal Revisited)''". Proc. IEEE, Vol. 86, No. 1, January 1988. |

|||

* Boga, Steven (1996). ''Badminton''. Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2487-5 |

|||

* {{cite journal |last=Boos |first=Dennis D.|author2=Oliver, Jacqueline M. Hughes |date=Aug 1998 |title=Applications of Basu's Theorem |jstor=2685927 |journal=The American Statistician |volume=52 |issue=3 |pages=218–221 |publisher=[[American Statistical Association]] |location=Boston |doi=10.2307/2685927}} |

|||

* Borwein, Jonathan M. & Bailey, David H. (2004) ''Mathematics by Experiment: Plausible Reasoning in the 21st Century'' [[Massachusetts]]: [[A K Peters, Ltd.]] ISBN 1-56881-211-6 |

|||

* Bourbaki, Nicolas (1998). ''Elements of the History of Mathematics''. Berlin, Heidelberg, and New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-64767-8. |

|||

* [[David Bressoud|Bressoud, David]] (2002), "Was Calculus Invented in India?", ''The College Mathematics Journal'' (Mathematical Association of America) '''33''' (1): 2-13 |

|||

* {{cite journal|first=T. A. A.|last=Broadbent|title=Reviewed work(s): ''The History of Ancient Indian Mathematics'' by C. N. Srinivasiengar|journal=The Mathematical Gazette|volume=52|issue=381|date=October 1968|pages=307–8|doi=10.2307/3614212}} |

|||

* Brown, W. Norman (1964). "The Indian Games of Pachisi, Chaupar, and Chausar". Expedition, 32-35. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. '''32''' (35). |

|||

'''C''' |

|||

* Chamberlin, J. Edward (2007). ''Horse: How the Horse Has Shaped Civilizations''. [[Moscow]]: Olma Media Group. ISBN 1-904955-36-3. |

|||

* Chandra, Anjana Motihar (2007). ''India Condensed: 5000 Years of History & Culture'' Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 981-261-350-1 |

|||