Dromedary: Difference between revisions

The Mol Man (talk | contribs) ummm congratulations? |

new section on camel hair, hides and wool |

||

| Line 193: | Line 193: | ||

A 2005 report, issued jointly by the [[Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia)]] and the [[United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]], details five cases of [[bubonic plague]] in humans, resulting from the ingestion of raw camel liver. Four of the five patients had severe [[pharyngitis]] and submandibular [[lymphadenitis]]. ''[[Yersinia pestis]]'' was isolated from the camel's bone marrow, as well as from the [[jird]] (''Meriones libycus'') and also from fleas (''[[Xenopsylla cheopis]]'') captured at the camel's [[corral]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Saeed|first= A. A. B.|title=Plague from eating raw camel liver |journal=Emerging Infect Dis.|volume=11 |issue=9 |pages=1456–7|date=September 2005 |pmid=16229781|last2=Al-Hamdan|first2=N.A.|last3=Fontaine|first3=R.E.|pmc=3310619 |doi=10.3201/eid1109.050081}}</ref> |

A 2005 report, issued jointly by the [[Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia)]] and the [[United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]], details five cases of [[bubonic plague]] in humans, resulting from the ingestion of raw camel liver. Four of the five patients had severe [[pharyngitis]] and submandibular [[lymphadenitis]]. ''[[Yersinia pestis]]'' was isolated from the camel's bone marrow, as well as from the [[jird]] (''Meriones libycus'') and also from fleas (''[[Xenopsylla cheopis]]'') captured at the camel's [[corral]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Saeed|first= A. A. B.|title=Plague from eating raw camel liver |journal=Emerging Infect Dis.|volume=11 |issue=9 |pages=1456–7|date=September 2005 |pmid=16229781|last2=Al-Hamdan|first2=N.A.|last3=Fontaine|first3=R.E.|pmc=3310619 |doi=10.3201/eid1109.050081}}</ref> |

||

===Camel hair, wool and hides=== |

|||

Camels generally do not develop long coats in hot climates. Camel hair is characterised by its lightness, low [[thermal conductivity]] and durability. Hence camel hair is quite suitable for manufacturing warm clothes and blankets, and even tents and rugs.<ref name=camel/> Hair of highest quality is typically obtained from juvenile camels or those in the wild.<ref name=singh/> In India, camels are clipped usually in spring and around {{convert|1|-|1.5|kg|lb|abbr=on}} hair is produced per clipping. However, in colder regions one clipping can yield as much as {{convert|5.4|kg|lb|abbr=on}}.<ref name=nanda/><ref name=singh/> |

|||

A dromedary can produce {{convert|1|kg|lb|abbr=on}} wool per year, whereas a Bactrian camel has a much higher annual yield of nearly {{convert|5|-|12|kg|lb|abbr=on}}.<ref name=leupold/> Young dromedaries, under the age of two years, have a fine undercoat that tends to fall off, and should be cropped by hand.<ref name=knoess/> Not much information has been collected about camel hides, though it is known that they are usually of inferior quality and less preferred for manufacturing leather.<ref name=camel/> |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 05:46, 3 February 2016

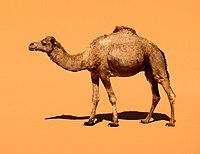

| Dromedary camel | |

|---|---|

| |

| A dromedary camel in the outback near Silverton, New South Wales, Australia. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Camelidae |

| Genus: | Camelus |

| Species: | C. dromedarius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Camelus dromedarius | |

| |

| Range of the dromedary | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Species synonymy

| |

The dromedary (/ˈdrɒmədɛri/ or /-ədri/), also called the Arabian camel (Camelus dromedarius), is a large, even-toed ungulate with one hump on its back. Greek philosopher Aristotle (4th century BCE) was the first to describe the species, and was given its current binomial name by Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish zoologist. The dromedary is the largest camel after the Bactrian camel. Adult male dromedaries stand 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) at the shoulder, while females are 1.7–1.9 m (5.6–6.2 ft) tall. The weight typically ranges from 400–600 kg (880–1,320 lb) in males and 300–540 kg (660–1,190 lb) in females. The distinctive features of this camel are its long curved neck, narrow chest and only one hump (compared to the two on the Bactrian camel), thick double-layered eyelashes and bushy eyebrows.The coat is generally a shade of brown, but can range from black to nearly white.The hump, which can be 20 cm (7.9 in) tall or more, is made up of fat bound together by fibrous tissue.

Their diet includes foliage and desert vegetation, like thorny plants which their extremely tough mouths allow them to eat. These camels are active in the day, and rest together in groups. Led by a dominant male, each herd consists of about 20 individuals. Some males form bachelor groups. Dromedaries show no signs of territoriality, as herds often merge during calamities. Predators in the wild include wolves and lions; and tigers in the past. Dromedaries use a wide set of vocalizations to communicate with each other. They have various adaptations to help them exist in their desert habitat. Dromedaries have bushy eyebrows and two rows of long eyelashes to protect their eyes, and can close their nostrils to face sandstorms. Their ears are also lined with protective hair. When water-deprived, they can fluctuate their body temperature by 6 °C, changing from a morning minimum of 34° to a maximum of 40° or so in the afternoon. This reduces heat flow from the environment to the body and thereby water loss through perspiration is minimised. They have specialized kidneys, which make them able to tolerate water loss of more than 30% of their body mass; a loss of 15% would prove fatal in most other animals. Mating usually occurs in winter, often overlapping the rainy season. One calf is born after the gestational period of 15 months, and is nurtured for about two years.

Etymology

The term "dromedary" comes from the Old French word dromedaire, or the Latin word dromedarius, which means "swift". It is based on the Greek word dromas, δρομάς (ο, η) (GEN (γενική) dromados, δρομάδος), meaning "runner" (δρομέας) .[2][3] An early variant of this word was 'drumbledairy' (used in the 1560s).[4] The word "dromedary" has been used in English since the 14th century AD.[5] Greek philosopher Aristotle referred to the dromedary as "the camel of the Arabians".[6]

The term "camel" could have been derived from the Latin camelus, or the Greek kamēlos.[7] It could also have originated from an old Semitic language, for example from the Hebrew gāmāl or the Arabic ǧamal.[8] A northern oïl dialect, such as Old Norman or Old Picard, could have also been an intermediate, where the word for "camel" was camel (compare Old French chamel, modern French chameau).[9] The scientific name of the dromedary is Camelus dromedarius, which could be based on the Greek δρομὰς κάμηλος (dromas kamelos), which means "running camel".[10]

Taxonomy

The dromedary is a member of the genus Camelus (camel) and the family Camelidae.[1] There is evidence that indicates the onset of speciation in Camelus in the early Pliocene.[11] Aristotle (4th century BCE) was the first to describe the species of Camelus, naming two species: the dromedary and the Bactrian camel. He defined them as one-humped and two-humped, respectively, in his book History of Animals.[12] The dromedary was given its current binomial name Camelus dromedarius by Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish zoologist, in his 1758 publication Systema Naturae.[13]

In 1927, British veterinarian Arnold Leese had classified dromedaries by their basic habitats: the hill camels, small muscular animals and efficient beasts of burden; plains camels, larger animals that could be further divided into desert type (that can bear light burden and are apt for riding) and the riverine type (that can bear heavy burden and move slowly); and the third group of animals that are intermediate between the previous two types.[14]

The dromedary and the Bactrian camel often interbreed to produce fertile offspring. Where the ranges of the two species overlap, such as in northern Punjab, Persia and Afghanistan, the phenotypic differences between them tend to decrease as a result of extensive crossbreeding between them. The fertility of their hybrid has given rise to speculation that the dromedary and the Bactrian camel should be merged into a single species, of which they would be two varieties.[14] However, a 1994 analysis of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene revealed that the species have a 10.3% difference.[15]

Genetics and hybrids

The diploid number of chromosomes in the dromedary is 74 , the same as in other camelids. The autosomes consist of five pairs of small to medium-sized metacentrics and submetacentrics.[16] The X chromosome is the largest of the metacentric and submetacentric group.[17] There are 31 pairs of acrocentrics.[16] The karyotypes are similar between the dromedary and the Bactria camel.[18]

The origin of camel hybridisation dates back to as early as the first millennium BCE.[19] For about a thousand years, Bactrian camels and dromedaries have been successfully bred in regions where they are sympatric (coexist) to form hybrids which are characterised by either a long and slightly lopsided hump, or two humps – one small and one large. These hybrids are larger and stronger than their parents – they can bear greater load.[17][19] A cross between a first generation female hybrid and a male Bactrian camel can also produce a hybrid. Other types of hybrids, though, tend to be bad-tempered or runts.[20]

Evolution

The extinct Protylopus, which occurred in the upper Eocene in North America, is the oldest as well as the smallest camel known.[21] In the transitional period from Pliocene to Pleistocene, several mammals faced extinction. However, the Camelus species migrated across the Bering Strait and dispersed widely to Asia, eastern Europe, and Africa.[22][23] By the Pleistocene, ancestors of the dromedary came to be known from the Middle East and northern Africa.[24] The modern dromedary probably evolved in the hotter and arid regions of western Asia from the bactrian camel, which in turn was closely related to the earliest Old World camels.[23] This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the dromedary foetus actually has two humps, while in the adult an anterior vestigial hump is present on an adult male.[14]

In 1975, Richard Bulliet, a professor of history at Columbia University, observed that the dromedary exists in large numbers in those areas from where the Bactrian camel has disappeared, and the converse is also true to a large extent. He suggested that this substitution could have occurred because the nomads of Syrian and Arabian deserts were heavily dependent upon the dromedary, while the Asiatic people domesticated the Bactrian camel but did not have to depend primarily upon it for milk, meat and wool.[25] The dromedary has gradually replaced the Bactrian camel along the Silk Route.

The dromedary possibly had origins in Arabia and is therefore sometimes referred to as the Arabian camel. A jawbone of a dromedary, whose radiocarbon date was 8200 BP, was found on the southern coast of the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia.[26][27]

Description

The dromedary is the largest camel after the Bactrian camel. Adult male dromedaries stand 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) at the shoulder, while females are 1.7–1.9 m (5.6–6.2 ft) tall. The weight typically ranges from 400–600 kg (880–1,320 lb) in males and 300–540 kg (660–1,190 lb) in females. The distinctive features of this camel are its long curved neck, narrow chest and only one hump (compared to the two on the Bactrian camel), thick double-layered eyelashes and bushy eyebrows. The hair is particularly long and concentrated on the throat, shoulders and the hump. The eyes are large and protected by prominent supraorbital ridges. The ears are small and rounded.[28][17] The dromedary camel exhibits sexual dimorphism, as both sexes differ in their appearance.[28] They have sharp eyesight and a good sense of smell.[27]

The coat is generally a shade of brown, but can range from black to nearly white.[17] Leese reported piebald dromedaries, with mouse-coloured necks and backs and white underparts, faces and legs, from Kordofan and Darfur in Sudan.[29] The male has a soft palate (dulaa in Arabic), nearly 18 cm (7.1 in) long, which it inflates to produce a deep pink sac. This palate is often mistaken for the tongue, as it hangs out of the side of the male's mouth to attract females during the mating season. The hairs are arranged in clusters of two to three cover hairs and two to five groups of woolly hair.[30][31] The hump, which can be 20 cm (7.9 in) tall or more, is made up of fat bound together by fibrous tissue.[17] The dromedary has long and powerful legs with two toes on each foot, which resemble flat, leathery pads.[32] Dromedaries move both legs on one side of the body at the same time, like the giraffe, which results in a swaying motion. [28]

The dromedary can be distinguished from the Bactrian camel by its lighter build, longer limbs and shorter hairs. The dromedary has a harder palate, and the ethmoidal fissure is small or absent.[33] The dromedary differs from the camelids of the genus Lama (consisting of the guanaco and the llama) in possessing a hump, a longer tail, smaller ears, squarer feet and being more than 1.7 m (5.6 ft) in height. In addition to this, the dromedary has four teats instead of the two in Lama.[17]

Anatomy

The cranium of the dromedary consists of a postorbital bar, a tympanic bulla (filled with spongiosa), a pronounced sagittal crest, long facial part, and an indented nasal bone.[34] The pad-shaped feet have two dorsal nails each. The front feet ,19 cm (7.5 in) wide and 18 cm (7.1 in) long, are larger than the hind feet, 17 cm (6.7 in) wide and 16 cm (6.3 in) long.[32] Typically, there are eight sternal and four asternal pairs of ribs.[29] The spinal cord, nearly 214 cm (84 in) long, terminates in the second and third sacral vertebra.[35] The fibula is reduced to a malleolar bone similar to a tarsal. The dromedary is a digitigrade animal as it walks on its toes or digits.b The dromedary lacks the second and fifth digits.[36]

The dromedary has 22 milk teeth, which are eventually replaced by 34 permanent teeth. The dental formula for permanent dentition is 1.1.3.33.1.2.3, while for the deciduous dentition it is 1.1.33.1.2.[37] The juvenile develops the lower first molars by 12-15 months, but the permanent lower incisors appear only at 4.5 to 6.5 years of age. All teeth are in use by the age of eight years.[38] The lenses of their eyes contain crystallin, which constitutes 8-13% of the total protein present there.[39]

The epidermis is 0.038–0.064 mm (0.0015–0.0025 in) thick, and the dermis is 2.2–4.7 mm (0.087–0.185 in) thick.[40] Though glands are absent on the face, males have glands 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) below the neck crest, on either side of the midline of the neck. These seem to be modified apocrine sweat glands which secrete a pungent, coffee-coloured fluid during rut. The weight of these glands generally increases during the rut, ranging from 20 to 115 g (0.71 to 4.06 oz).[41] Each cover hair of the camel is associated with a separate hair follicle and a ring of sebaceous glands, a tubular sweat gland and an arrector pilli muscle.[30] The females have cone-shaped mammary glands, which are 2.4 cm (0.94 in) in length and 1.5 cm (0.59 in)in diameter at the base. The mammary gland is four-chambered and divided into a left and a right half by an intermammary ridge.[42] They can continue to lactate even during dehydration, with the water content exceeding 90%.[17]

The heart weighs 5 kg (11 lb), and has two ventricles with the apex curving to the left. Its pulse rate is 50 beats per minute. The normal blood volume is 0.093 L (0.020 imp gal).[43] The pH of the blood varies from 7.1 to 7.6. The state of hydration, sex and season can influence the blood values for an individual.[44] The lungs are not lobed.[29] A dehydrated camel has a lower breathing rate.[45] The kidneys each have a volume of 858 cm3 (52.4 cu in), and can produce urine with high chloride concentrations. It is the only mammal with oval red blood corpuscles, and it lacks a gall bladder. The grayish violet spleen is crescent-shaped, and weighs less than 500 g (18 oz).[46] The liver is divided into four parts and is triangular; the dimensions are 60×42×18 cm (23.6×16.5×7.1 in) and has a mass of 6.5 kg (14 lb).

The ovaries, present in females, are reddish in colour, circular, and flattened.[47] They are enclosed in a conical bursa, and have a size of 4×2.5×0.5 cm (1.57×0.98×0.20 in) during anestrus. The oviducts are 25–28 cm (9.8–11.0 in) in length. The uterus is bicornuate. The vagina, 3–3.5 cm (1.2–1.4 in) long, has well-developed Bartholin's glands.[22] The vulva is 3–5 cm (1.2–2.0 in) deep and contains a small clitoris.[37] The placenta is diffuse and epitheliochorial, with a crescent-like chorion.[48] The scrotum, present in males, is located high in the perineum with testicles in separate sacs. Testicles are 7–10 cm (2.8–3.9 in) long, 4.5 cm (1.8 in) deep and 5 cm (2.0 in) in width.[17] The right testicle is often smaller than the left.[14] The typical mass of either testicle is less than 140 g (0.31 lb); however, at the time of rut the mass can range from 165–253 g (0.364–0.558 lb).[17] The prostate gland is dark yellow, usually disc-shaped and divided into two lobes. The Cowper's gland is white, shaped like an almond, and lacks seminal vesicles.[49] The penis is covered by a triangular penile sheath opening backwards,[50] and is about 60 cm (24 in) long.[49]

Health and diseases

The dromedary generally suffers from fewer diseases than other domestic livestock such as goats and cattle.[51] Temperature fluctuations occur throughout the day in a healthy dromedary - it is usually minimum at dawn, then rises till sunset and falls during the night.[52] Vomiting may occur if a nervous camel is handled, and need not indicate any disorder. A rutting male may develop nausea.[14]

The dromedary is prone to trypanosomiasis, transmitted by the tsetse fly. The main symptoms are recurring fever, anemia, and weakness, which usually ends with the camel's death.[53] Brucellosis is another disease of dromedaries. In an observational study, the seroprevalence of the disease was usually low (2-5%) in nomadic or loosely confined dromedaries, while it was high (8-15%) in those kept closely together. Brucellosis is caused by different biotypes of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis.[54] Other internal parasites include Fasciola gigantica, a trematode (flatworm); two types of cestode (tapeworm), and various nematodes (roundworms). Among external parasites, Sarcoptes species cause sarcoptic mange.[17] In a study in Jordan, 83% of the 32 camels tested positive for sarcoptic mange, and 33% of the 257 examined specimens were seroprevalent for trypanosomiasis.[55] In another study, following the rinderpest outbreak in Ethiopia, dromedaries were found to have natural antibodies against rinderpest virus and ovine rinderpest virus.[56]

In 2013, a seroepidemiological study (a study investigating the patterns, causes and effects of a disease on a specific population based on serologic tests) in Egypt published in the journal of Eurosurveillance first presented the possibility that the dromedary might be a host for the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).[57] A 2013-14 study of dromedaries in Saudi Arabia revealed the unusual genetic stability of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in the dromedary, coupled with its high seroprevalence in the camel, made the dromedary a highly probable host for the virus. The full genome sequence of MERS-CoV from dromedaries in this study showed a 99.9% match to the genomes of human clade B MERS-CoV.[58] Another study in Saudi Arabia revealed the presence of MERS-CoV in 90% of the evaluated dromedary camels, and even suggested that camels could be the animal source of MERS-CoV.[59]

Fleas and ticks are common causes of physical irritation. In a study in Egypt, a species of Hyalomma specific to the dromedary was predominant, comprising 95.6% of the adult ticks isolated from the dromedaries. In Israel, the number of ticks per camel ranged from 20 to 105. Nine camels in the date palm plantations in Arava Valley were injected with ivermectin, but it was not effective against Hyalomma tick infestations.[60] Larvae of Cephalopsis titillator, the camel nasal fly, can cause brain compression and nervous disorders, which might prove fatal. Illnesses that can affect dromedary productivity are pyogenic diseases and wound infections due to Corynebacterium and Streptococcus; pulmonary disorders caused by Pasteurella (like hemorrhagic septicemia), and Rickettsia ; camelpox; anthrax; and cutaneous necrosis due to Streptothrix and dietary salt deficiency.[17]

Ecology

The dromedary is active mainly during the daytime. Dromedaries rest together in strongly cohesive groups, often moving in caravan-like formations. Generally, herds consist of about 20 individuals, led by a dominant male and consisting of several females. Females may also lead in turns.[17] Some males either form bachelor groups or roam alone.[61] Herds of over hundreds of animals may be formed, joining other herds during natural calamities and when searching for water. Short-term home ranges of the feral camels in Australia are 50–150 km2 (19–58 sq mi) in area, and annual home ranges could spread over several thousand square kilometres.[17]

During the mating season, males become very aggressive, sometimes snapping each other and wrestling. The male declares his success in the fight by placing the rival's head between his legs and body. Free-ranging camels face the large predators typical of their regional distribution, which includes wolves, lions and tigers. Camels are often injured or killed by moving vehicles.[32]

Some special behavioral features of the camel include snapping at other camels without biting them and showing displeasure by stamping their feet. Camels scratch parts of their bodies with their front or hind legs or with their lower incisors. They may also rub against tree bark and roll in the sand. Their main vocalisations include a sheep-like bleat used to locate individuals and the gurgle of rutting males, while a whistling noise is produced as a threat noise by males by grinding the teeth together.[28] They are not usually aggressive, with the exception of rutting males. The males of the herd prevent their females from interacting with other bachelor males by standing or walking between them and driving other males away. Camels apparently remember their homes; females in particular remember the place they first gave birth or suckled their offspring.[17]

A 1980 study showed that androgen levels in the blood of males influenced their behavior. Between January and April, when these levels are high due to their being in rut, they become difficult to manage, blow out a palate flap from the mouth, vocalize, and throw urine over their backs with their tails.[62]

Diet

The diet of the dromedary mostly consists of foliage, dry grasses, and available desert vegetation (mostly thorny plants) growing in the camel's natural habitat.[63] A study gave the following composition of the typical diet of the dromedary: dwarf shrubs (47.5%), trees (29.9%), grasses (11.2%), other herbs (0.2%) and vines (11%).[64] The dromedary is primarily a browser, with forbs and shrubs comprising 70% of their diet in summer and 90% in winter. The dromedary may also graze on, or suck in, tall young succulent grasses.[65]

In the Sahara, 332 plant species have been recorded for the dromedary. These include Aristida pungens, Acacia tortilis, Panicum turgidum, Launaea arborescens and Balanites aegyptiaca.[32] The dromedary will feed on Acacia, Atriplex, and Salsola plants whenever available.[65] The feral dromedaries in Australia prefer Trichodesma zeylanicum and Euphorbia tannensis. In India dromedaries are fed with forage plants such as Vigna aconitifolia, V. mungo, Cyamopsis tetragonolaba, Melilotus parviflora, Eruca sativa, Trifolium species and Brassica campestris.[65] The dromedaries keep their mouths open while chewing thorny food. They use their lips to grasp the food, then chew each bite 40-50 times. Features like long eyelashes, eyebrows, lockable nostrils, caudal opening of the prepuce and a relatively small vulva help the camel avoid injuries, especially while feeding.[63] They graze for 8-12 hours per day and ruminate for an equal amount of time.[17]

Adaptations

Dromedaries have several adaptations for their desert habitat. Bushy eyebrows, a double row of eyelashes, and the ability to close their nostrils assist in water conservation and prevent sand and dust from entering, even in a sandstorm. Dromedaries can conserve water by fluctuating their body temperature throughout the day from 34.0 to 41.7 °C, which saves water by avoiding perspiration at the rise of the external temperature. The kidneys are specialized so that not much water is excreted. Groups of camels also avoid excess heat from the environment by pressing against each other. The dromedary can tolerate greater than 30% water loss, which is impossible for other mammals. In temperatures of 30-40 °C (86-104 °F), they need water every 10 to 15 days, and only in the hottest temperatures do they take water every four to seven days. They have a very fast rate of rehydration and can drink at the speed of 10–20 L (2.6–5.3 US gal) per minute.[17] Maintaining the brain temperature within certain limits is critical for animals; to assist this, dromedaries have a rete mirabile, a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other which uses countercurrent blood flow to cool blood flowing to the brain.[66]

The hump stores up to 80 lb (36 kg) of fat, which a camel can break down into water and energy when sustenance is not available. If the hump is small, the animal can show signs of starvation. In a 2005 study, the mean volume of adipose tissues (in the external part of the hump that have cells to store lipids) is related to the dromedary's unique mechanism of food and water storage.[67] In case of starvation, they can even eat fish and bones, and drink brackish and salty water.[27] The hair is longer at the throat, hump and shoulders. The pads widen under its weight when it steps on the ground.[28][68] This prevents the dromedary from sinking much into the sand. When the dromedary walks, it moves both the feet on the same side of the body at the same time. This way of walking makes the dromedary's body swing from side to side as it walks, hence its nickname: "the ship of the desert". Its thick lips help in eating coarse and thorny plants.

They can adapt their body temperature from 34°C to 41.7°C, to conserve water. They have an average lifespan of 40 years, which may increase to 50 years under captivity.[28]

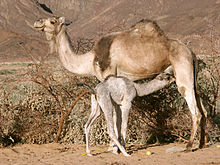

Reproduction

Since camels have a slow growth rate,[69] they reach sexual maturity only in advanced years.[14] This age varies geographically and also depends on the individual, as does the reproductive period of their life.[14] Females reach sexual maturity typically around three years of age and mate around age four or five. Males begin to mate at around three years of age, too, but still are not sexually mature until six years of age.[28] Mating occurs once a year, and peaks in the rainy season. The mating season lasts three to five months, but may even last a year for older animals.[14]

During the reproductive season, males splash their urine on their tails and nearer regions. Males extrude their soft palate to attract females - a trait unique to the dromedary.[70] Copious saliva turns to foam as the male gurgles, covering the mouth.[28] Males threaten each other for dominance over the female by trying to stand taller than the other, making low noises and a series of head movements including lowering, lifting, and bending their necks backwards. A male tries to defeat other males by biting at his legs and taking the opponent's head in between his jaws.[41] Copulation begins with a necking exercise. The male smells the female's genitalia, and often bites her in that region or around her hump.[71] The male makes the female sit, and then grasps her with his forelegs. The camelmen often aid the male to enter his penis into the female's vulva.[72] It is disputed whether the male dromedary can penetrate the female on his own or not.[14] Copulation time ranges from 7 to 35 minutes, averaging 11 to 15 minutes. Normally, three to four ejaculations occur.[14] The semen of a Bikaneri dromedary was found to be white and viscous, with a pH of around 7.8.[71]

A single calf is born after a gestational period of 15 months. Calves move freely by the end of their first day. Nursing and maternal care continue for one to two years.[28] In a study to find whether young could exist on milk substitutes, two male young camels, one month old, were separated from their mothers and were fed on milk substitutes prepared commercially for lambs. For the initial 30 days, the changes in their weights were marked. Each gained 0.400 kg (0.88 lb) and 1 kg (2.2 lb), respectively, per day. Finally, they were found to have grown properly and weighed normal weights of 135 kg (298 lb) and 145 kg (320 lb).[73] Lactational yield can vary with species, breed, individual, region, diet, management conditions and lactating stage.[74] Maximum milk is produced during the early period of lactation.[14] The length of the lactation period can vary from nine to eighteen months.[75]

Dromedaries are induced ovulators.[76] Oestrus might be cued by nutritional status of the camel and the daylength.[77] If mating does not occur, the follicle, which grows during estrus, usually regresses within a few days.[78] In one study, 35 complete estrous cycles were observed in five nonpregnant females over a period of 15 months. The cycles were about 28 days long, in which follicles matured in six days, maintained their size for 13 days, and returned to their original size in eight days.[79] In another study, ovulation could be best induced when the follicle reaches a size of 0.9–1.9 cm (0.35–0.75 in).[80] In another study, pregnancy in females could be recognized as early as 40 to 45 days of gestation by the swelling of the left uterine horn, where 99.52% of pregnancies were located.[81]

Distribution

The dromedary does not occur naturally in the wild since nearly 2000 years. In the wild, the dromedary inhabits arid regions, notably the Sahara Desert in Africa. The original range of the camel’s wild ancestors was probably southern Asia and the Arabian peninsula. Its range stretched across the dry hot regions of northern Africa, Ethiopia, the Near East, and western to central Asia.[82] The dromedary typically thrives in areas with a long dry season and a short wet season.[83] They are sensitive to cold and humidity,[37] though certain breeds can thrive under humid conditions.[83]

In the present day, the domesticated dromedary is generally found in the semi-arid to arid regions of the Old World.[83] In Africa, that holds more than 80% of the world's total dromedary population, the dromedary occurs in almost every desert zone in the northern part of the continent. The Sahel marks the southern extreme of its range, which is nearly 2-3°S latitude, where the annual rainfall may be 550 mm (22 in). The Horn of Africa holds nearly 35% of the world's total dromedary population,[83] the maximum occurring in Somalia, followed by Sudan and Ethiopia (as of early 2000s).[84] According to the Yearbook of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) for 1984, eastern Africa shelters about 10 million dromedaries, the largest dromedary population of Africa. Western Africa follows with 2.14 million dromedaries, while northern Africa has a population of nearly 0.76 million.[85] Populations have soared by 16% from 1994 to 2005 in the continent.[84][86]

The dromedary is also found in feral populations in northern Australia, where it was introduced in 1840.[87] The total dromedary population in Australia is 0.5 million as of 2005. Nearly 99% of the populations are feral, and increasing at an annual growth rate of 10%.[84] Majority of the Australian feral camels are dromedaries, with only a few Bactrian camels. Most of these dromedaries occur in Western Australia, while smaller populations occur in the Northern Territory, Western Queensland and northern South Australia.[84]

In Asia, nearly 70% of the total population occurs in India and Pakistan. The combined population of the dromedary and the Bactrian camel has seen a fall of around 21% between 1994 and 2004.[88] The dromedary is sympatric with the Bactrian camel in Afghanistan, Pakistan, central and southwestern Asia.[89] India shelters a dromedary population of less than one million, with the maximum numbers (0.67 million) in the state of Rajasthan.[84] Populations in Pakistan have fallen from 1.1 million in 1994 to 0.8 million in 2005 - a 29% decline.[88] According to the FAO, the dromedary population in the Persian Gulf was nearly 0.67 million in 2003, distributed over six countries. In the Persian Gulf region the dromedary is locally classified into breeds based on coat colour, such as Al-Majahem, Al-Hamrah, Al-Safrah, Al-Zarkah and Al-Shakha. The UAE has three prominent breeds: Racing camel, Al-Arabiat and Al-Kazmiat.[90]

Domestication

The dromedary was first domesticated probably in Somalia or Arabian Peninsula about 4000 years ago.[91]In the ninth or tenth century BCE, the dromedary became popular in the Near East. The Persian invasion of Egypt under Cambyses in 525 BCE introduced domesticated camels to the area. The Persian camels, however, were not particularly suited to trading or travel over the Sahara; journeys across the desert were made on chariots pulled by horses.[92][93] The dromedary was introduced into northern Africa (Egypt) from southwestern Asia (Arabia and Persia).[53][94] The popularity of dromedaries got the next major boost after the Islamic conquest of North Africa. While the invasion was accomplished largely on horseback, the new links to the Middle East allowed camels to be imported en masse. These camels were well-suited to long desert journeys and could carry a great deal of cargo, allowing substantial trade over the Sahara for the first time.[95][96] In Libya, they were used for transportation within the country, and their milk and meat constituted the local diet.[97]

Individuals were also shipped from southwestern Asia to Spain, Italy, Turkey, France, Canary Islands, the Americas and Australia.[14] Dromedaries were introduced into Spain in 1020 AD and to Sicily in 1059 AD.[98] Dromedaries had also been exported to the Canary Islands in 1405 AD, during the times of European colonisation of the area, and still exist, particularly in Lanzarote and to the south of Fuerteventura.[98] Attempts had been made to introduce dromedaries into the Caribbean, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil between the 17th and the 19th centuries; some were imported to the western United States in the 1850s and some to Namibia in the early 1900s, but presently they exist in small numbers or are absent in these areas.[29]

In 1840, about six camels were shipped from Tenerife to Adelaide, but only one survived through the trip, reaching the destination on October 12 that year. The animal, a male, was called Harry and was owned by the explorer John Ainsworth Horrocks. Although Harry had proved to be bad-tempered, he was included in an expedition in the following year because of he could carry heavy loads. The next major group of camels were imported in 1860 and between 1860 and 1907 some 10 to 12 thousand were imported. These were used mainly for riding and transportation.[99][100]

Relationship with humans

The strength and docility of the dromedary make it a popular domesticated animal.[14] As summarised by Bulliet, the camel can be used for a wide variety of purposes: milking, riding, transport, feeding (on their meat), ploughing, trading and clothing (using their wool and leather).[25] The main attraction these animals have for nomadic groups in deserts is the wide variety of resources they provide them with, which is is crucial for their survival and also holds much economic significance. For instance, the camel is the backbone for several Bedouin pastoralist tribes of northern Arabia, such as the Ruwallah, Shammar and Mutayr.[101]

Riding camels

Although the role of the camel is diminishing in many areas across its range with the advent of technology and modern means of transport, it still acts as an efficient mode of communication in remote ad less developed areas. The camel, that has been used in battles since as early as 2nd century BCE,[102] still remains popular in sports such as camel racing, particularly in the Arab world.[14] The riding camels of Arabia, Egypt and the Sahara are locally known as the Dilool, the Hageen and the Mehara respectively; several local breeds are also included within these groups.[29]

Ideally, the riding camel should be strong, slender and long-legged with thin and supple skin. The special adaptations of the dromedary's feet allow it to walk with ease even on sandy and rough terrain, and even on cold surfaces.[103] The camels of the Bejas[94] (of Sudan) and the Anafi camel (bred in Sudan) are two common breeds used as riding camels.[14]

Leese identified and explained four types of speeds or gaits of the dromedary: walk, jog, fast run and canter. The first is the typical speed of walking, around 4 km/h (2.5 mph). Jog is the most common speed, nearly 8–12 km/h (5.0–7.5 mph) on level ground. He estimated a speed of 14–19 km/h (8.7–11.8 mph) during a fast run, by observing northern African and Arabian dromedaries. He did not give any particular speed range to describe the "canter", but implied that it was a sort of galloping which if induced could exhaust both the camel and the rider. Canter could be used only for short periods of time, for example in races.[104]

The ideal age to start training dromedaries for riding is three years,[41] although they may be stubborn and unruly.[105] Firstly, the head of the camel is controlled, followed by training it on how to respond to commands on sitting and standing, and to allow mounting.[29] At this stage camels will often try to run away when one tries to mount on it.[14] The next stage involves training in responding to reins. The animal must be given loads gradually and not forced to carry heavy loads before the age of six.[29] Riding camels should not be struck on their necks, rather they should be struck in the area of their body just behind the right leg of the rider.[41] Leese described two types of saddles generally used in camel riding: the Arabian markloofa (used by single riders) and the Indian pakra when two riders mount the same camel.[29]

Baggage and draught camels

The baggage camel should be robust and heavy. Studies have recommended that an ideal baggage camel should have either a small or a large head with a narrow aquiline nose, prominent eyes and large lips. In addition to this, the neck should be medium to long so that the head is held high, the chest should be deep, and the hump should be well-developed with sufficient space behind it to accommodate the saddle. The hindlegs should be heavy, muscular and sturdy.[106][107] The dromedary can be trained to carry baggage from the age of five years, but must not be given heavy loads before the age of six years.[108] The hawia is a typical baggage saddle from Sudan.[107] The methods of training the baggage camels are similar to those for riding camels.[14]

Draught camel are utilised for several purposes such as ploughing, processing in oil mills and pulling carts. There is no clear description for the ideal draught camel, though the strength of the animal, its capability to survive without water and the flatness of its feet could be used as yardsticks.[14] It may be used for ploughing in pairs or in groups with buffaloes or bullocks.[29] The draught camel can plough at a speed of 2.5 km/h (1.6 mph), and should not be used for more than six hours a day (four hours in the morning and two in the afternoon).[105] The camel is not easily exhausted (unless diseased or undernourished), and has remarkable endurance and hardiness.[23]

Dairy products

Camel milk is a staple food of nomadic tribes living in deserts. According to a study, it consists of 11.7% total solids, 3% protein, 3.6% fat, 0.8% ash, 4.4% lactose, and 0.13% acidity (pH 6.5). The quantities of sodium, potassium, zinc, iron, copper, manganese, niacin and vitamin C were relatively higher than the amounts in cow milk. However, the levels of thiamin, riboflavin, folacin, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, vitamin A, lysine, and tryptophan were lower than those in cow milk. The molar percentages of the fatty acids in milk fat were 26.7% for palmitic acid, 25.5% oleic acid, 11.4% myristic acid, and 11% palmitoleic acid.[109] The milk is rich in water and mineral contents.[110] Camel milk has higher thermal stability compared to cow's milk.[111] It does not compare favourably with sheep milk.[14]

Daily yield generally varies from 3.5 to 35 kg (7.7 to 77.2 lb) and from 1.3% to 7.8% of the body weight.[112] Amount of milk yield in dromedaries varies geographically, and depends upon their diet and living conditions.[14] At the peak of lactation, a healthy female would typically provide 9 kg (20 lb) milk per day.[23] Leese estimated that a lactating female would yield 4 to 9 L (0.88 to 1.98 imp gal) besides the amount ingested by the calf.[29] The Pakistani dromedary, considered a better milker and bigger, can yield 9.1–14.1 kg (20–31 lb) when well fed.[113] Dromedaries in Somalia may be milked two to four times a day,[75] while those in Afar (Ethiopia) may be milked as many as six or seven times a day.[114]

The acidity of dromedary milk stored at 30 °C (86 °F) increases at a slower rate than than that of cow milk.[17] Though the preparation of butter from dromedary milk is a difficult task, it has been carried out successfully in 1959 in the erstwhile USSR. In this attempt the cream of the dromedary milk, containing 4.2% fat, had yielded 25.8% butter.[115] Dromedary milk was studied to find if it could form curd. Milk coagulation did not show actual curd formation, and had a pH of 4.4. It was much different from the curd produced from cow milk, and had a fragile heterogeneous composition probably composed of casein flakes.[116] Nevertheless, cheese (even hard cheese) and other dairy products can be made out of the camel's milk. A study found that bovine calf rennet could be exploited to coagulate dromedary milk.[117] A special factory has been set up in Nouakchott to pasteurize and make cheese out of camel's milk.[118]

Meat

The meat of a five-year-old dromedary has a typical composition of 76% water, 22% protein, 1% fat, and 1% ash.[77] The carcass, weighing 141–310 kg (311–683 lb) for a five-year-old dromedary,[77] is composed of nearly 57% muscle, 26% bone, and 17% fat.[119] Seven to eight-year-old camels can produce a carcass of weight of 125–400 kg (276–882 lb). The meat is a raspberry red to a dark brown or maroon, while the fat is white in colour. It tastes like beef and has the same texture.[119] A study of the meat of Iranian dromedaries revealed its high glycogen content, due to which it was sweet like horse meat. The carcass of well fed camels was found to be covered with a thin layer of good quality fat.[120] In a study of the fatty acid composition of raw meat taken from the hind legs of seven young males (one to three years old), 51.5% were saturated fatty acids, 29.9% were monounsaturated, and 18.6% were polyunsaturated fatty acids, in chains. The major fatty acids in the meat were palmitic acid (26.0%), oleic acid (18.9%), and linoleic acid (12.1%). In the hump, palmitic acid was dominant (34.4%), followed by oleic acid (28.2%), myristic acid (10.3%), and stearic acid (10%).[121]

Dromedary slaughter is tougher than the slaughter of other domestic livestock such as cattle, due to the large size of the animal and the significant amount of manual work involved. Both males and females are slaughtered, but the males are slaughtered in larger numbers.[122] Though less affected by mishandling than other livestock, the pre-slaughter handling of the dromedary plays a crucial role in determining the quality of meat obtained - for instance, mishandling can often disfigure the hump.[123] The animal is then stunned, seated in a crouching position (with the head in a caudal position) and slaughtered.[122] The dressing percentage (the percentage of the mass of the animal that finally forms the carcass) is 55-70%,[77] more than the the 45-50% in the case of cattle.[14] Camel meat, however, is rarely consumed by camel herders in Africa, who use it only during severe food scarcity, or for rituals.[14] Camel meat is processed into food items such as burgers, patties, sausages, and shawarma.[119] Dromedaries can be slaughtered between four and ten years of age. As the age of the animal increases, the meat grows tougher and deteriorates in taste as well as quality.[14]

A 2005 report, issued jointly by the Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia) and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, details five cases of bubonic plague in humans, resulting from the ingestion of raw camel liver. Four of the five patients had severe pharyngitis and submandibular lymphadenitis. Yersinia pestis was isolated from the camel's bone marrow, as well as from the jird (Meriones libycus) and also from fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) captured at the camel's corral.[124]

Camel hair, wool and hides

Camels generally do not develop long coats in hot climates. Camel hair is characterised by its lightness, low thermal conductivity and durability. Hence camel hair is quite suitable for manufacturing warm clothes and blankets, and even tents and rugs.[14] Hair of highest quality is typically obtained from juvenile camels or those in the wild.[41] In India, camels are clipped usually in spring and around 1–1.5 kg (2.2–3.3 lb) hair is produced per clipping. However, in colder regions one clipping can yield as much as 5.4 kg (12 lb).[105][41]

A dromedary can produce 1 kg (2.2 lb) wool per year, whereas a Bactrian camel has a much higher annual yield of nearly 5–12 kg (11–26 lb).[51] Young dromedaries, under the age of two years, have a fine undercoat that tends to fall off, and should be cropped by hand.[125] Not much information has been collected about camel hides, though it is known that they are usually of inferior quality and less preferred for manufacturing leather.[14]

References

- ^ a b Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 646. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ δρομάς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ "Dromedary". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "dromedary". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Heller, L.; Humez, A.; Dror, M. (1984). The Private Lives of English Words (1st ed.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 58–9. ISBN 0-7102-0006-4.

- ^ Seventeenth Annual Report of the Ohio State Board of Agriculture. Richard Nevins, State Printer. 1863. p. 331.

- ^ "Camel". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Camel". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "camel". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Groves, C.; Grubb, P. (2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 32. ISBN 1-4214-0093-6.

- ^ Smith, W.; Anthon, C. (1870). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (3rd ed.). Harper and Brothers Publishers. p. 204.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturae (10th ed.). Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius. p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Mukasa-Mugerwa, E. (1981). The Camel (Camelus dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review (PDF). Addis Ababa: International Livestock Centre for Africa. pp. 1–147.

- ^ Stanley, H. F.; Kadwell, M.; Wheeler, J. C. (1994). "Molecular evolution of the family Camelidae: a mitochondrial DNA study". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 256 (1345): 1–6. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0041.

- ^ a b Benirschke, K.; Hsu, T.C. (1974). Camelus bactrianus (An Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes Volume 8). New York: Springer. pp. 153–6. ISBN 978-1-4615-6432-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kohler-Rollefson, I. U. (12 April 1991). "Camelus dromedarius" (PDF). Mammalian Species (375). The American Society of Mammalogists: 1–8.

- ^ Taylor, K.M.; Hungerford, D.A.; Snyder, R.L.; Ulmer, Jr.F.A. (1968). "Uniformity of karyotypes in the Camelidae". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 7 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1159/000129967.

- ^ a b Potts, D. T. (1 June 2004). "Camel hybridization and the role of Camelus bactrianus in the ancient Near East". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 47 (2): 143–65. doi:10.1163/1568520041262314.

- ^ Kolpakow, V.N. (1935). "Über Kamelkreuzungen". Berliner und Münchner Tierärztliche Wochenschrift. 51: 617–22.

- ^ JSTOR 3629022

- ^ a b Novoa, C. (1 June 1970). "Reproduction in Camelidae". Reproduction. 22 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0220003.

- ^ a b c d Williamson, G.; Payne, W.J.A. (1978). An Introduction to Animal Husbandry in the Tropics (3rd ed.). London: Longman. p. 485. ISBN 0-582-46813-2.

- ^ Prothero, D. R.; Schoch, R. M. (2002). Horns, Tusks, and Flippers : The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 53–4. ISBN 0-8018-7135-2.

- ^ a b Bulliet, R.W. (1975). The Camel and the Wheel (Morningside Books ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231072359.

- ^ Grigson, C.; Gowlett, J. A. J.; Zarins, J. (July 1989). "The camel in Arabia—a direct radiocarbon date, calibrated to about 7000 BC". Journal of Archaeological Science. 16 (4): 355–62. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(89)90011-3.

- ^ a b c Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Vol. 2 (6th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1078–81. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Naumann, R. "Camelus dromedarius". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Leese, A.S. (1927). A Treatise on the One-Humped Camel in Health and in Disease. ISBN 9781493132485.

- ^ a b Lee, D.G.; Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1962). "The skin, sweat glands and hair follicles of the camel (Camelus dromedarius)". The Anatomical Record. 143 (1): 71–7. doi:10.1002/ar.1091430107.

- ^ Dowling, D.F.; Nay, T. (1962). "Hair follicles and the sweat glands of the camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Nature. 195: 578–80.

- ^ a b c d Gauthier-Pilters, H.; Dagg, A. I. (1981). The Camel, Its Evolution, Ecology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-28453-0.

- ^ Lesbre, F.X. (1903). "Recherches anatomiques sur les camélidés". Archives du Musée d'Histoire Naturelle de Lyon. 8: 1–195.

- ^ Sandhu, P.S.; Dhingra, L.D. (1986). "Cranial capacity of Indian camel. Short communication". Indian Journal of Animal Sciences. 56: 870–2.

- ^ Hifny, A.K.; Mansour, A.A.; Moneim, M.E.A. (1985). "Some anatomical studies of the spinal cord in camel". Assiut Veterinary Medicine Journal. 15: 11–20.

- ^ Simpson, C.D. (1984). "Orders and families of recent mammals of the world (by S. Anderson, J.K. Jones Jr.)". Artiodactyls. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 563–87.

- ^ a b c Wilson, R.T. (1988). The Camel (2nd ed.). London: Longman. pp. 1–223. ISBN 9780582775121.

- ^ Rabagliati, D.S. (1924). The Dentition of the Camel. Cairo: Egypt Ministry of Agriculture. pp. 1–32.

- ^ Garland, D.; Rao, P.V.; Del Corso, A.; Mura, U.; Zigler JS, Jr. (1991). "zeta-Crystallin is a major protein in the lens of Camelus dromedarius". Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 285 (1): 134–6. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(91)90339-K. PMID 1990971.

- ^ Ghobrial, Laurice I. (1970). "A comparative study of the integument of the camel, Dorcas gazelle and jerboa in relation to desert life". Journal of Zoology. 160 (4): 509–21. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1970.tb03094.x.

- ^ a b c d e f Singh, U.B.; Bharadwaj, M.B. (1978). "Anatomical, histological and histochemical observations and changes in the poll glands of the camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Cells Tissues Organs. 102 (1): 74–83. doi:10.1159/000145621.

- ^ Saleh, M. S.; Mobarak, A. M.; Fouad, S. M. (1971). "Radiological, anatomical and histological studies of the mammary gland of the one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Zentralblatt für Veterinärmedizin Reihe A. 18 (4): 347–52. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0442.1971.tb00587.x.

- ^ Hegazi, A.H. (1954). "The liver of the camel as revealed by macroscopic and microscopic examinations". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 15 (56): 444–6.

- ^ Barakat, M. Z.; Abdel-Fattah, M. (13 May 2010). "Seasonal and sexual variations of certain constituents of normal camel blood". Zentralblatt für Veterinärmedizin Reihe A. 18 (2): 174–8. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0442.1971.tb00852.x.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, K.; Crawford, E.C.Jr.; Newsome, A.E.; Rawson, K.S.; Hammel, H.T. (1967). "Metabolic rate of camels: effect of body temperature and dehydration". American Journal of Physiology. 212: 341–6.

- ^ Hegazi, A.H. (1953). "The spleen of the camel compared with other domesticated animals and its microscopic examination". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 122 (912): 182–4.

- ^ Arthur, G.H.; A/Rahim, A.T.; Al Hindi, A.S. (November 1985). "Reproduction and genital diseases of the camel". British Veterinary Journal. 141 (6): 650–9. doi:10.1016/0007-1935(85)90014-4.

- ^ Morton, W.R.M. (1961). "Observations on the full-term foetal membranes of three members of the Camelidae (Camelus dromedarius L., Camelus bactrianus L., and Lama glama L.)". Journal of Anatomy. 95 (2): 200–9. PMC 1244464.

- ^ a b Mobarak, A. M.; ElWishy, A. B.; Samira, M. F. (1972). "The penis and prepuce of the oe-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Zentralblatt für Veterinärmedizin Reihe A. 19 (9): 787–95. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0442.1972.tb00532.x.

- ^ R. Yagil (1985). The Desert Camel: Comparative Physiological Adaptation. Karger. ISBN 978-3-8055-4065-0.

- ^ a b Leupold, J. (1968). "Camel--an important domestic animal of the subtropics". Blue Book for the Veterinary Profession. 15: 1–6.

- ^ Leese, A.S. (1969). "" Tips" on camels for veterinary surgeons on active service" (PDF). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation: 1–56.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Currason, G. (1947). "Le Chameau et ses Maladies". Paris: Vigotfreres: 188–237.

- ^ Abbas, B.; Agab, H. (10 September 2002). "A review of camel brucellosis". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 55 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1016/S0167-5877(02)00055-7. PMID 12324206.

- ^ Al-Rawashdeh, O. F.; Al-Ani, F. K.; Sharrif, L. A.; Al-Qudah, K. M.; Al-Hami, Y.; Frank, N. (September 2000). "A survey of camel (Camelus dromedarius) diseases in Jordan". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 31 (3). American Association of Zoo Veterinarians: 335–8. doi:10.1638/1042-7260(2000)031[0335:ASOCCD]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1042-7260. PMID 11237140.

- ^ Roger, F.; Yesus, M. G.; Libeau, G.; Diallo, A.; Yigezu, L. M.; Yilma, T. (2001). "Detection of antibodies of rinderpest and peste des petits ruminants viruses (Paramyxoviridae, Morbillivirus) during a new epizootic disease in Ethiopian camels (Camelus dromedarius)". Revue de Médecine Veterinaire. 152 (3). France: Ecole Nationale Veterinaire De Toulouse: 265–8. ISSN 0035-1555.

- ^ Perera, R.; Wang, P.; Gomaa, M.; El-Shesheny, R.; Kandeil, A.; Bagato, O.; Siu, L.; Shehata, M.; Kayed, A.; Moatasim, Y.; Li, M.; Poon, L.; Guan, Y.; Webby, R.; Ali, M.; Peiris, J.; Kayali, G. (5 September 2013). "Seroepidemiology for MERS coronavirus using microneutralisation and pseudoparticle virus neutralisation assays reveal a high prevalence of antibody in dromedary camels in Egypt, June 2013". Eurosurveillance. 18 (36): 20574. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.36.20574.

- ^ Hemida, M. G.; Chu, D.K.W.; Poon, L.L.M.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Alhammadi, M. A.; Ng, Hoiyee-Y.; Siu, L.Y.; Guan, Y.; Alnaeem, A.; Peiris, M. (2014). "MERS coronavirus in dromedary camel herd, Saudi Arabia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (7): 1–4. doi:10.3201/eid2007.140571.

- ^ Hemida, M.; Perera, R.; Wang, P.; Alhammadi, M.; Siu, L.; Li, M.; Poon, L.; Saif, L.; Alnaeem, A.; Peiris, M. (12 December 2013). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013". Eurosurveillance. 18 (50): 20659. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.50.20659.

- ^ Straten, M.; Jongejan, F. (August 1993). "Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting the Arabian Camel (Camelus dromedarius) in the Sinai, Egypt with a note on the acaricidal efficacy of ivermectin". Experimental and Applied Acarology. 17 (8): 605–16. doi:10.1007/BF00053490. PMID 7628237.

- ^ Klingel, H. (1985). "Social organization of the camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Verhandl. Deutsch. Zool. Gesellsch. 78: 210.

- ^ Yagil, R.; Etzion, Z. (1 January 1980). "Hormonal and behavioral patterns in the male camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Reproduction. 58 (1): 61–5. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0580061. PMID 7359491.

- ^ a b Sambraus, H.H. (June 1994). "Biological function of morphologic peculiarities of the dromedary". Tierarztliche Praxis. 22 (3): 291–3. PMID 8048041.

- ^ Field, C.R. (1979). "Ecology and management of camels, sheep and goats in northern Kenya. Mimeo, Nairobi, UNEP/MAB/IPAL". United Nations Environmental Programme/Man and Biosphere -Integrated Project in Arid Lands: 1–18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Newman, D.M.R. (1979). "The feeds and feeding habits of Old and New World camels" (PDF). The Camelid. 1: 250–92.

- ^ Inside Nature's Giants. Channel 4 (UK) documentary. Transmitted 30 August 2011

- ^ Faye, B.; Esenov, P. (2005). "Body lipids and adaptation of camel to food and water shortage: new data on adipocyte size and plasma leptin". Desertification Combat and Food Safety: the Added Value of Camel Producers, Ashgabad, Turkmenistan. NATO Science Series: Life and Behavioural Sciences. Vol. 362. IOS Press. pp. 135–45. ISBN 1-58603-473-1.

- ^ "Arabian (Dromedary) Camel (Camelus dromedarius)". National Geographic.

- ^ Chatty, D. (1972). "Structural forces of pastoral nomadism, with special reference to camel pastoral nomadism". Institute of Social Studies (The Hague) Occasional Papers (16): 1–96.

- ^ H., Pilters; T., Krumbach; W.G., Kükenthal (1956). "Das verhalten der Tylopoden". Handbuch der Zoologie. 8 (10): 1–24.

- ^ a b Khan, A.A.; Kohli, I.S. (1973). "A note on the sexual behaviour of male camel (Camelus dromedarius)". The Indian Journal of Animal Sciences. 43 (12): 1092–4.

- ^ Hartley, B.J. (1979). "The dromedary of the Horn of Africa". Paper presented at Workshop on Camels. Stockholm: International Foundation for Science: 77–97.

- ^ Elias, E.; Cohen, D.; Steimetz, E. (1986). "A preliminary note on the use of milk substitutes in the early weaning of dromedary camels". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology. 85 (1): 117–9. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(86)90471-8.

- ^ Klintegerg, R.; Dina, D. (1979). "Proposal for a rural development training project and study concerned with camel utilization in arid lands in Ethiopia". Addis Abab (Mimeographed): 1–11.

- ^ a b Bremaud, O. (1969). "Notes on camel production in the Northern districts of the Republic of Kenya". Maisons-Alfort, IEMVT (Institut d'Elevage et de MWdecine Vftfrinaire des Pays Tropicaux). ILCA: 1–105.

- ^ Chen, B.X., Yuen, Z.X. and Pan, G.W. (1985). "Semen-induced ovulation in the bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus)". J. Reprod. Fert. 74 (2): 335–339. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0740335.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Shalash, M.R.; Nawito, M. (1965). "Some reproductive aspects in the female camel". World Rev. Anim. Prod. 4: 103–8.

- ^ Skidmore, J. A. (July–September 2005). "Reproduction in dromedary camels: an update" (PDF). Animal Reproduction. 2 (3): 161–71.

- ^ Musa, B.; Abusineina, M. (16 December 1978). "The oestrous cycle of the camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Veterinary Record. 103 (25): 556–7. doi:10.1136/vr.103.25.556. PMID 570318.

- ^ Skidmore, J. A.; Billah, M.; Allen, W. R. (1 March 1996). "The ovarian follicular wave pattern and induction of ovulation in the mated and non-mated one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Reproduction. 106 (2): 185–92. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.1060185. PMID 8699400.

- ^ ElWishy, A. B. (March 1988). "A study of the genital organs of the female dromedary (Camelus dromedarius)". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 82 (2): 587–93. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0820587. PMID 3361493.

- ^ Wardeh, M. F. (2004). "Classification of the dromedary camels". Camel Science. 1: 1–7. CiteSeerx: 10.1.1.137.2350.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, R.T.; Bourzat, D. (1987). "Research on the dromedary in Africa" (PDF). Scientific and Technical Review. 6 (2): 383–9.

- ^ a b c d e Rosati, A.; Tewolde, A.; Mosconi, C. (2007). Animal Production and Animal Science Worldwide. Wageningen (The Netherlands): Wageningen Academic Publishers. pp. 168–9. ISBN 9789086860340.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organisation, United Nations (1984). Food and Agriculture Organisation Production Yearbook. Rome: United Nations.

{{cite book}}: Check|first1=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Sghaier, M. (2004). "Camel production systems in Africa" (PDF). ICAR Technical Series: 22–33.

- ^ Roth, H. H.; Merz, G. (1996). Wildlife Resources : A Global Account of Economic Use. Springer. pp. 272–7. ISBN 3-540-61357-9.

- ^ a b Köhler-Rollefson, I. (2005). "The camel in Rajasthan: Agricultural biodiversity under threat" (PDF). Saving the Camel and Peoples’ Livelihoods. 6: 14–26.

- ^ Geer, A. (2008). Animals in Stone : Indian Mammals Sculptured Through Time. Brill. pp. 144–9. ISBN 978-90-04-16819-0. ISSN 0169-9377.

- ^ Kadim, I.T.; Maghoub, O. (2004). "Camelid genetic resources. A report on three Arabian Gulf [sic] Countries" (PDF). ICAR Technical Series: 81–92.

- ^ Richard, Suzanne (2003). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. Eisenbrauns. p. 120. ISBN 9781575060835.

- ^ Bromiley, G. W. (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume One: AD. W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-3781-6.

- ^ Gellner, A. M. K. (1994). Nomads and the Outside World (2nd ed.). University of Wisconsin Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-299-14284-1.

- ^ a b Epstein, H. (1971). "History and origin of the African camel". The origin of the domestic animals in Africa. African Publishing Corporation: 558–64.

- ^ Harris, N. (2003). Atlas of the World's Deserts. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 223. ISBN 0-203-49166-1.

- ^ Kaegi, W. E. (2010). Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- ^ Lawless, R. I.; Findlay, A. M. (1984). North Africa: Contemporary Politics and Economic Development (1 ed.). Croom Helm. p. 128. ISBN 0-7099-1609-4.

- ^ a b Schulz, U.; Tupac-Yupanqui, I.; Martínez, A.; Méndez, S.; Delgado, J. V.; Gómez, M.; Dunner, S.; Cañón, J. (2010). "The Canarian camel: a traditional dromedary population". Diversity. 2 (4): 561–71. doi:10.3390/d2040561. ISSN 1424-2818.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Afghan Cameleers in Australia". Australian Government. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "The Introduction of camels into Australia". Burkes & Wills Web (Digital Research Archive). The Burke & Wills Historical Society. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Sweet, L.E. (1965). "Camel raiding of North Arabian Bedouin: a mechanism of ecological adaptation". American Anthropologist. 67 (5): 1132–50. doi:10.1525/aa.1965.67.5.02a00030.

- ^ Robertson, J. (1938). With the Cameliers in Palestine. Marshall Press. pp. 35–44.

- ^ Bligh, J.; Cloudsley-Thompson, J.L.; Macdonald, A.G. Environmental Physiology of Animals. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. pp. 142–5. ISBN 9780632004164.

- ^ Gillespie, L.A. (1962). "Riding camels of the Sudan". Sudan J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husb. 3 (1): 37–42.

- ^ a b c Nanda, P.N. (1957). "Camel and their managment". Indian Council of Agricultural Research: 1–17.

- ^ Mason, I.L.; Maule, J.P. (1960). The Indigenous Livestock of Eastern and Southern Africa. England: Farnham Royal, Bucks, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux. pp. 1–248.

- ^ a b JSTOR 41716025

- ^ Matharu, B.S. (1966). "Camel care". Indian Farming. 16: 19–22.

- ^ Sawaya, W. N.; Khalil, J. K.; Al-Shalhat, A.; Al-Mohammad, H. (1 May 1984). "Chemical composition and nutritional quality of camel milk". Journal of Food Science. 49 (3): 744–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb13200.x.

- ^ El Amin, F.M. (1979). ""The dromedary camel of the Sudan" presented at Workshop on camels, Khartoum, Sudan, 18-20 December 1979". International Foundation for Science Provisional Report: 35–53.

- ^ Farah, Z.; Atkins, D. (1992). "Heat coagulation of camel milk". Journal of Dairy Research. 59 (2): 229. doi:10.1017/S002202990003048X.

- ^ Knoess, K. H. (1980). "Milk production of the dromedary". Provisional Report, International Foundation for Science (6): 201–14.

- ^ Yasin, S.A.; Wahid, A. (1957). "Pakistan camels. A preliminary survey". Agriculture Pakistan. 8: 289–97.

- ^ Knoess, K.H. (1977). "The camel as a meat and milk animal". World Animal Review.

- ^ Kuliev, K.A. (1959). "The utilisation of camels' milk". Animal Breeding Abstracts. 27: 392.

- ^ Attia, H.; Kherouatou, N.; Dhouib, A. (2001). "Dromedary milk lactic acid fermentation: microbiological and rheological characteristics". Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 26 (5): 263–70. doi:10.1038/sj.jim.7000111. PMID 11494100.

- ^ Ramet, J.P. (1987). "Saudi Arabia: use of bovine calf rennet to coagulate raw camel milk". World Animal Review (FAO). 61: 11–16.

- ^ Bonnet, P. (1998). Dromadaires et chameaux, animaux laitiers : actes du colloque (Dromedaries and Camels, Milking Animals). CIRAD. p. 195. ISBN 2-87614-307-0.

- ^ a b c Kadim, I.T.; Mahgoub, O.; Purchas, R.W. (1 November 2008). "A review of the growth, and of the carcass and meat quality characteristics of the one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Meat Science. 80 (3): 555–69. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.02.010. PMID 22063567.

- ^ Khatami, K. (1970). Camel meat: A new promising approach to the solution of meat and protein in the arid and semi-arid countries of the world. Tehran: Ministry of Agriculture, Tehran. pp. 1–4.

- ^ Rawdah, T. N.; El-Faer, M. Z.; Koreish, S. A. (1994). "Fatty acid composition of the meat and fat of the one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Meat Science. 37 (1): 149–55. doi:10.1016/0309-1740(94)90151-1. PMID 22059419.

- ^ a b Kadim, I.T. (2013). Camel Meat and Meat Products. Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK: CABI. pp. 54–72. ISBN 9781780641010.

- ^ Cortesi, M.L. (March 1994). "Slaughterhouses and humane treatment". Revue Scientifique Et Technique (International Office of Epizootics). 13 (1): 171–93. PMID 8173095.

- ^ Saeed, A. A. B.; Al-Hamdan, N.A.; Fontaine, R.E. (September 2005). "Plague from eating raw camel liver". Emerging Infect Dis. 11 (9): 1456–7. doi:10.3201/eid1109.050081. PMC 3310619. PMID 16229781.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

knoesswas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

External links

Media related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikispecies

Data related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikispecies- Information from ITIS

The dictionary definition of dromedary at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of dromedary at Wiktionary