Sixtine Vulgate: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

|||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

After [[Pope Clement VIII|Clement VIII]] had recalled all the copies of the Sixtine Vulgate in 1592,<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":32"/> in November of that year he published a new official version of the Vulgate known as the [[Clementine Vulgate]],{{Sfnp|Metzger|1977|p=349}}<ref name=":8">{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/reformationofbib0000peli|url-access=registration|title=The reformation of the Bible, the Bible of the Reformation|last=Pelikan|first=Jaroslav Jan|date=1996|publisher=[[Yale University Press]]|others=Dallas : Bridwell Library ; Internet Archive|isbn=|location=New Haven|pages=[https://archive.org/details/reformationofbib0000peli/page/14 14], 98|chapter=1 : Sacred Philology ; Catalog of Exhibition [Item 1.14]|author-link=Jaroslav Pelikan|url-status=live}}</ref> also called the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.<ref name=":8" />{{Sfnp|Gerace|2016|p=225}} Faced with about six thousand corrections on matters of detail, and a hundred that were important, and wishing to save the honour of Sixtus V, Bellarmine undertook the writing of the preface of this edition. He ascribed all the imperfections of Sixtus' Vulgate to [[Printing press|press]] errors.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/historyofcouncil00bung|title=History of the Council of Trent|last=Bungener|first=Félix|publisher=[[Harper (publisher)|Harper and Brothers]]|year=1855|isbn=|location=|pages=[https://archive.org/details/historyofcouncil00bung/page/92 92]}}</ref>{{Efn|1=See also Bellarmine's testimony in his autobiography: |

After [[Pope Clement VIII|Clement VIII]] had recalled all the copies of the Sixtine Vulgate in 1592,<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":32"/> in November of that year he published a new official version of the Vulgate known as the [[Clementine Vulgate]],{{Sfnp|Metzger|1977|p=349}}<ref name=":8">{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/reformationofbib0000peli|url-access=registration|title=The reformation of the Bible, the Bible of the Reformation|last=Pelikan|first=Jaroslav Jan|date=1996|publisher=[[Yale University Press]]|others=Dallas : Bridwell Library ; Internet Archive|isbn=|location=New Haven|pages=[https://archive.org/details/reformationofbib0000peli/page/14 14], 98|chapter=1 : Sacred Philology ; Catalog of Exhibition [Item 1.14]|author-link=Jaroslav Pelikan|url-status=live}}</ref> also called the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.<ref name=":8" />{{Sfnp|Gerace|2016|p=225}} Faced with about six thousand corrections on matters of detail, and a hundred that were important, and wishing to save the honour of Sixtus V, Bellarmine undertook the writing of the preface of this edition. He ascribed all the imperfections of Sixtus' Vulgate to [[Printing press|press]] errors.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/historyofcouncil00bung|title=History of the Council of Trent|last=Bungener|first=Félix|publisher=[[Harper (publisher)|Harper and Brothers]]|year=1855|isbn=|location=|pages=[https://archive.org/details/historyofcouncil00bung/page/92 92]}}</ref>{{Efn|1=See also Bellarmine's testimony in his autobiography: |

||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

In 1591, [[Gregory XIV]] wondered what to do about the Bible published by Sixtus V, where so many things had been wrongly corrected. There was no lack of serious men who were in favor of a public condemnation. But, in the presence of the [[Sovereign Pontiff]], I demonstrated that this edition should not be prohibited, but only corrected in such a way that, in order to save the honor of Sixtus V, it be republished amended: this would be accomplished by making disappear as soon as possible the unfortunate modifications, and by reprinting under the name of this Pontiff this new version with a preface where it would be explained that, in the first edition, because of the haste that had been brought, some errors were made through the fault either of printers or of other people. This is how I returned good for evil to Pope Sixtus. Sixtus, indeed, because of my thesis on the direct power of the Pope, had put my [[Disputationes|''Controversies'']] on the [[Index of Prohibited Books]] until after correction; but as soon as he died, the [[Sacred Congregation of Rites]] ordered my name to be removed from the Index. My advice pleased Pope Gregory. He created a Congregation to quickly revise the Sistine version and to bring it closer to the vulgates in circulation, in particular {{Interlanguage link|Biblia Vulgata lovaniensis|lt=that of Leuven|pl|Biblia Vulgata lovaniensis|WD=}}. [...] After the death of Gregory (XIV) and [[Innocent V|Innocent (V)]], [[Clement VIII]] edited this revised Bible, under the name of Sixtus (V), with the Preface of which I am the author.{{Cite book|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/autobiografia16100bell/page/59|title=Autobiografia (1613)|last=Bellarmino|first=Roberto Francesco Romolo|date=1999|publisher=Morcelliana|others=Internet Archive|isbn=88-372-1732-3|editor-last=Giustiniani|editor-first=Pasquale|location=Brescia|pages=[https://archive.org/details/autobiografia16100bell/page/59 59–60]|language=Italian|translator-last=Galeota|translator-first=Gustavo|chapter=Memorie autobiografiche (1613)|chapter-url-access=registration}}<br>(in original Latin: [https://books.google.be/books?id=kbs-xzAKadgC&pg=PA5&lpg=PA5&dq=sixto%20V#v=onepage&q=sixto%20V&f=false ''Vita ven. Roberti cardinalis Bellarmini''], pp. 30–31); (in French [https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k932002v/f108.image here], pp. 106–107)|name=|group=}} "However, a weak possibility remains that Sixtus V, who we know worked until the last day of his life to purge his Bible of the printing mistakes it contained, had let slip a few words which were heard by his [[wikiwikiweb:familiar#Noun|familiars]], |

In 1591, [[Gregory XIV]] wondered what to do about the Bible published by Sixtus V, where so many things had been wrongly corrected. There was no lack of serious men who were in favor of a public condemnation. But, in the presence of the [[Sovereign Pontiff]], I demonstrated that this edition should not be prohibited, but only corrected in such a way that, in order to save the honor of Sixtus V, it be republished amended: this would be accomplished by making disappear as soon as possible the unfortunate modifications, and by reprinting under the name of this Pontiff this new version with a preface where it would be explained that, in the first edition, because of the haste that had been brought, some errors were made through the fault either of printers or of other people. This is how I returned good for evil to Pope Sixtus. Sixtus, indeed, because of my thesis on the direct power of the Pope, had put my [[Disputationes|''Controversies'']] on the [[Index of Prohibited Books]] until after correction; but as soon as he died, the [[Sacred Congregation of Rites]] ordered my name to be removed from the Index. My advice pleased Pope Gregory. He created a Congregation to quickly revise the Sistine version and to bring it closer to the vulgates in circulation, in particular {{Interlanguage link|Biblia Vulgata lovaniensis|lt=that of Leuven|pl|Biblia Vulgata lovaniensis|WD=}}. [...] After the death of Gregory (XIV) and [[Innocent V|Innocent (V)]], [[Clement VIII]] edited this revised Bible, under the name of Sixtus (V), with the Preface of which I am the author.{{Cite book|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/autobiografia16100bell/page/59|title=Autobiografia (1613)|last=Bellarmino|first=Roberto Francesco Romolo|date=1999|publisher=Morcelliana|others=Internet Archive|isbn=88-372-1732-3|editor-last=Giustiniani|editor-first=Pasquale|location=Brescia|pages=[https://archive.org/details/autobiografia16100bell/page/59 59–60]|language=Italian|translator-last=Galeota|translator-first=Gustavo|chapter=Memorie autobiografiche (1613)|chapter-url-access=registration}}<br>(in original Latin: [https://books.google.be/books?id=kbs-xzAKadgC&pg=PA5&lpg=PA5&dq=sixto%20V#v=onepage&q=sixto%20V&f=false ''Vita ven. Roberti cardinalis Bellarmini''], pp. 30–31); (in French [https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k932002v/f108.image here], pp. 106–107)|name=|group=}} "However, a weak possibility remains that Sixtus V, who we know worked until the last day of his life to purge his Bible of the printing mistakes it contained, had let slip a few words which were heard by his [[wikiwikiweb:familiar#Noun|familiars]], of which Angelo Rocca was, and making think that he was planning a reedition."{{Sfnp|Quentin|1922|loc=Chapitre septième - Les éditions sixtine et Clémentine (1590-1592) [Chapter seven - The Sixtine and Clementine editions (1590-1592)]|pp=200-201}} |

||

Scrivener notes: "To avoid the appearance of a conflict between the two |

Scrivener notes: "To avoid the appearance of a conflict between the two Popes, the Clementine Bible was boldly published under the name of Sixtus, with a preface by Bellarmine asserting that Sixtus had intended to bring out a new edition in consequence of errors that had occurred in the printing of the first, but had been prevented by death; now, in accordance with his desire, the work was completed by his successor."<ref name=":3" /> |

||

The full name of the Clementine Vulgate was: ''Biblia sacra Vulgatae Editionis, Sixti Quinti Pont. Max. iussu recognita atque edita''<ref name="Delville" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":12" /> (translation: |

The full name of the Clementine Vulgate was: ''Biblia sacra Vulgatae Editionis, Sixti Quinti Pont. Max. iussu recognita atque edita''<ref name="Delville" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":12" /> (translation:"The Holy Bible of the Common/Vulgate Edition identified and published by the order of Pope Sixtus V.")<ref name=":12" /> The fact that the Clementine edition retained the name of Sixtus on its title page is the reason why the Clementine Vulgate is sometimes known as the ''Sixto-Clementine Vulgate''.<ref name=":12" /> |

||

Nestle notes: "It may be added that the first edition to contain the names of both the Popes [Sixtus V and Clement VIII] upon the title page is that of 1604. The title runs: 'Sixti V. Pont. Max. iussu recognita et Clementis VIII. auctoritate edita'."<ref name="nestle23">{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/introductiontote00nestrich|title=Introduction to the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament|last=Nestle|first=Eberhard|date=1901|publisher=London [etc.] [[Williams and Norgate]]; New York, G. P. Putnam's Sons|others=University of California Libraries|year=|isbn=|editor-last=Menzies|editor-first=Allan|edition=2nd|location=|pages=[https://archive.org/details/introductiontote00nestrich/page/128 128]|translator-last=Edie|translator-first=William|chapter=Chapter II.}}</ref> Hasting also points out that "[t]he regular form of title in a modern Vulgate Bible — 'Biblia Sacra Vulgatae Editionis Sixti V. Pont. Max. jussu recognita et Clementis VIII. auctoritate edita' — cannot be traced at present |

Nestle notes: "It may be added that the first edition to contain the names of both the Popes [Sixtus V and Clement VIII] upon the title page is that of 1604. The title runs: 'Sixti V. Pont. Max. iussu recognita et Clementis VIII. auctoritate edita'."<ref name="nestle23">{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/introductiontote00nestrich|title=Introduction to the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament|last=Nestle|first=Eberhard|date=1901|publisher=London [etc.] [[Williams and Norgate]]; New York, G. P. Putnam's Sons|others=University of California Libraries|year=|isbn=|editor-last=Menzies|editor-first=Allan|edition=2nd|location=|pages=[https://archive.org/details/introductiontote00nestrich/page/128 128]|translator-last=Edie|translator-first=William|chapter=Chapter II.}}</ref> Hasting also points out that "[t]he regular form of title in a modern Vulgate Bible — 'Biblia Sacra Vulgatae Editionis Sixti V. Pont. Max. jussu recognita et Clementis VIII. auctoritate edita' — cannot be traced at present earlier than 1604; up to that time Sixtus seems to have appeared alon upon the title page; later, Clement occasionally figures by himself."<ref name=":32" /> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 01:07, 15 February 2020

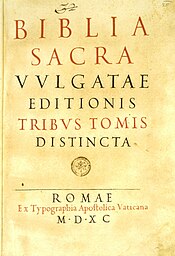

Frontispiece (with title) of the Vulgata Sixtina | |

| Language | Latin |

|---|---|

| Genre | Official Bible of the Catholic Church |

| Published | 1590 |

| Publication place | Papal States |

| Followed by | Sixto-Clementine Vulgate |

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The Vulgata Sixtina, Sixtine Vulgate or Sistine Vulgate is the edition of the Vulgate which was published in 1590, prepared on the orders of Pope Sixtus V and promulgated by him. The first edition of the Latin Vulgate authorised by a pope, its official recognition was short-lived; the edition was replaced in 1592 by the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.

The Vulgata Sixtina is cited in the Novum Testamentum Graece, or Nestle-Aland, only when it differs from the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate, and is designated in said Nestle-Aland by the siglum vgs.[1][2] It is also cited in the Oxford Vulgate New Testament, where it is designated by the siglum S.[3][4][5] It is not cited in the Stuttgart Vulgate.[6]

History

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent decreed the Vulgate authoritative[7] and "authentic" on 8 April 1546,[8] and ordered it to be printed "quam emendatissime"[a] ("with the fewest possible faults").[b][7][9] There was no authoritative edition of the Vulgate in the Catholic Church at that time; that would come in May 1590.[7]

Elaboration of the text

Three pontifical committees

"Three Pontifical Committees have been successively charged to elaborate the text of the edition of the Vulgate of which the Council of Trent had asked the publication[.] [...] [U]p until the Committees of S. Pius V and Sixtus-Quintus [...] there has only been works done without any coordination".[10]

After Sixtus V's death in 1590,[11] two other committees were organised, one after the other, under Gregory XIV in 1591.[12]

Pius IV's committee

In 1561, Pius IV created a committee[13][10] at Rome[8] composed of four cardinals: Amulio, Morone, Scotti and Vitelli. This committee had only a very general role—to correct and print the ecclesiastical books which the Holy See had decided to reform or publish.[10]

Pius V's committee

In 1569,[13] or 1566,[14] another committee was appointed by Pope Pius V[13] (Congregatio pro emendatione Bibliorum);[15] this comittee was composed of five cardinals (M. A. Colonna, G. Sirleto, C. Madruzzo, J. Souchier, and Antonio Carafa)[13][14] and twelve advisors.[14]

Gregory XIII did not appoint a committee for the Vulgate,[13] and soon Gugliemo Sirleto "was the only one remaining to take care of the revision" in Rome.[16] Gregory XIII "issued [...] a Committee on the emendation of the LXX"[13] after being convinced to do so by Cardinal Montalto (the future Sixtus V).[17]

Sixtus V's committee

At the time when Sixtus V became pope, in 1585,[11] work on the edition of the Vulgate had barely begun.[8] Sixtus V took pride in being a very competent text editor. When he was only a minor friar, he had started editing an edition of the complete work of St. Ambrose, whose sixth and last volume was published after he became pope. This edition is regarded as the worst ever published; it "replaced the readings of the manuscripts by the least justified conjectures".[18]

In 1586, Sixtus V appointed a committee.[13] The committee was under the presidency of Cardinal Carafa,[4][19] and was composed of Flaminius Nobilius, Antonius Agellius, Lelio Landi, Bartholomew Valverde, and Petrus Morinus. They were helped by Fulvio Orsini.[19]

The committee worked on the basis of the 1583 edition of Francis Lucas "of Bruges" of the Leuven Vulgate[20] and "[g]ood manuscripts were used as authorities, including notably the Codex Amiatinus."[7][21] By the end of 1588, Sixtus began to lose patience concerning the slowness of the progress of the committee, and asked Carafa to either give him (Sixtus) a completed edition or stop working on said edition; "in any case, the intention of Sixtus was to review everything himself."[22] Carafa presented the results of their work to Sixtus, but Sixtus rejected them.[c][24]

Sixtus was an "impetuous pontiff"; he "made it his own affair" to prepare an edition of the Vulgate and even corrected the proofs himself, saying he corrected them "with [his] own hands".[8] Sixtus made the corrections to the text himself; he made corrections using simple conjectures and worked quickly.[24] He used the Codex Carafianus[25] — the codex containing the propositions made to Sixtus V by the committee presided over by Cardinal Carafa.[26] Sixtus was helped in his editing work by a few people he trusted: Toledo, Rocca, and others, excluding the members of the committee and Carafa.[27]

Publication

In May 1590 the completed work was issued in three volumes[7] in a folio edition;[5] however, it is actually one volume, with the page numbering continuous throughout.[4][5] Regardless, even after printing, Sixtus continued to tinker with the text, revising it either by hand or by pasting strips of paper on the text.[28] The Sixtine Vulgate was mostly free of typographical errors.[29][5]

This edition is known as the Vulgata Sixtina,[30] Sixtine Vulgate, or Sistine Vulgate.[31] The full title of the Sixtine Vulgate is: Biblia sacra Vulgatae Editionis ad Concilii Tridentini praescriptum emendata et a Sixto V P. M. recognita et approbata.[1][32]

The edition was preceded by the bull Aeternus Ille, in which the Pope declared the authenticity of the new Bible.[29][5] The bull stipulated "that it was to be considered as the authentic edition recommended by the Council of Trent, that it should be taken as the standard of all future reprints, and that all copies should be corrected by it."[4] "This edition was not to be reprinted for 10 years except at the Vatican, and after that any edition must be compared with the Vatican edition, so that 'not even the smallest particle should be altered, added or removed' under pain of the 'greater excommunication'."[29] This was the first time the Vulgate was recognized as the official authoritative text.[33]

Based on his study of testimonies by those who were present around the pope during the making of the Vulgata Sixtina, and the fact that the bull Aeternus Ille is not present in the bullarium, Jesuit Xavier-Marie Le Bachalet claims the publication of this Bible does not have papal infallibility, because the bull establishing this edition as the standard was never promulgated by Sixtus V. Le Bachalet says that the bull was only printed within the edition of the Bible at the order of Sixtus V so as not to delay the printing and that the published edition of the Bible was not the final one. Sixtus was still revising the text of this edition of the Bible, and his death prevented him from completing a final edition and promulgating an official bull.[28][d]

Textual caracteristics

Three whole verses were dropped from the Book of Numbers (Numbers 30:11–13), though it is unclear whether this was a printing error or an editorial choice, "as the passage was cited by moral theologians to substantiate the view that husbands may annul vows of chastity taken by their wives without their consent."[34]

According to Eberhard Nestle the Sixtine Vulgate edition had "a text more nearly resembling that of Robt. Stephen than that of John Hentenius",[35] an analysis also shared by Scrivener[4] and Hastings; with Hastings claiming that the text of the Sixtine Vulgate resembles the 1540 editon of Robt. Stephen.[5] Kenyon considers that the Sixtine Vulgate resembles the text of Robt. Stephen, and argues that the Sixtine Vulgate was "evidently based" on the text of Robt. Stephen.[21] However, a difference with the edition of Robt. Stephen was that "a new system of verse-enumeration was introduced."[5][31] According to Antonio Gerace, the Sixtine Vulgate "was even closer to the Leuven Vulgate".[36]

Death of Pius V

On 27 August 1590 Sixtus V died. After his death, many alleged that the text of the Sixtine Vulgate was "too error-ridden for general use".[37] On 5 September of the same year, the College of Cardinals stopped all further sales of the Sixtine Vulgate, and bought and destroyed as many copies as possible[e] by burning them; the reason invoked for this action was printing inaccuracies in Sixtus V's edition of the Vulgate. Metzger believes that the printing inaccuracies may have been a pretext and that the attack against this edition had been instigated by the Jesuits, "whom Sixtus had offended by putting one of Bellarmine's books on the 'Index',[f] and took this method of revenging themselves."[39] Quentin suggests that this decision was due to the fact that the heretics could have used against the Catholic Church the passages of the Bible which Sixtus V had either removed or modified.[40]

After Sixtus V's death, Robert Bellarmine wrote a letter in 1602 to Clement VIII trying to dissuade him from resolving the question of the auxiliis divinae gratiae by himself, in which Bellarmine says: "Your Holiness also knows in what danger Sixtus V put himself and put the whole Church, by trying to correct the Bible according to his own judgment: and for me I really do not know if there has ever been greater danger."[41][42][43][44]

Recall of the Sixtine Vulgate

In January 1592,[4] almost immediately after his election, Clement VIII recalled all copies of the Sixtine Vulgate[5] as one of his first acts.[21] The reason invoked for recalling Sixtus V's edition was printing errors, although the Sixtine Vulgate was mostly free of them.[29][5]

According to James Hastings, Clement VIII's "personal hostitlity" toward Sixtus and his belief that the Sixtine Vulgate was not "a worthy representative of the Vulgate text" were the reasons behind the recall.[5] Nestle "suggests that the revocation was really due to the influence of the Jesuits, whom Sixtus had offended by putting one of Bellarmine's books on the Index Librorum prohibitorum."[4] Kenyon writes that the Sixtine Vulgate was "full of errors", but that Clement VIII was also motivated in his decision to recall the edition by the Jesuits, "whom Sixtus had offended."[45] Sixtus regarded the Jesuits with disfavour and suspicion. He considered making radical changes to their constitution, but his death prevented this from being carried out.[46] Sixtus V objected to some of the Jesuits' rules and especially to the title "Society of Jesus". He was at the point of changing these when he died.[11] Sixtus V "had some conflict with the Society of Jesus more generally, especially regarding the Society's concept of blind obedience to the General, which for Sixtus and other important figures of the Roman Curia jeopardized the preeminence of the role of the pope within the Church."[38] Jaroslav Pelikan, without giving any more details, says that the Sixtine Vulgate "proved to be so defective that it was withdrawn".[47]

Some differences from the Leuven edition

In the Sixtine Vulgate, in the Book of Genesis chapters 40-50, 43 corrections were made (on the basis of Codex Carafianus) compared to the Leuven Vulgate editions:[48]

40,8 – nunquam ] numquam

40,14 – tibi bene ] bene tibi

41,13 – quicquid ] quidquid

41,19 – nunquam ] numquam

41,20 – pecoribus ] prioribus

41,39 – nunquid ] numquid

41,55 – quicquid ] quidquid

42,4 – quicquam ] quidquam

42,11 – quicquam ] quidquam

42,13 – at illi dixerunt ] at illi

42,22 – nunquid ] numquid

42,38 – adversitatis ] adversi

43,3 – denuntiavit ] denunciavit

43,5 – denuntiavit ] denunciavit

43,7 – nunquid ] numquid

43,19 – dispensatorem ] dispensatorem domus

43,30 – lachrymae ] lacrymae

44,4 – ait surge ] surge

44,29 – maerore ] moerore

45,13 – nuntiate ] nunciate

45,20 – dimittatis ] demittatis

45,20 – auicquam ] quidquam

45,23 – tantundem ] tantumdem

45,23 – addens eis ] addens et

45,26 – nuntiaverunt ] nunciaverunt

46,10 – Chananitidis ] Chanaanitidis

46,10 – Cahath ] Caath

46,13 – Simeron ] Semron

46,16 – Sephon ] Sephion

46,16 – Aggi ] Haggi

46,16 – et Esebon et Suni ] et Suni et Esebon

46,17 – Jamma ] Jamme

46,22 – quatuordecim ] quattuordecim

46,26 – cunctaeque ] cunctae

46,28 – nuntiaret ] nunciaret

46,28 – et ille occurreret ] et occurreret

46,31 – nuntiabo ] nunciabo

47,1 – nuntiavit ] nunciavit

47,9 – peregrinationis vitae meae ] peregrinationis meae

47,24 – quatuor ] quattuor

47,31 – Dominum ] Deum

48,1 – nuntiatum ] nunciatum

49,1 – annuntiem ] annunciem

Of these 43 corrections, 31 are of purely orthographic significance, of which six relate to proper nouns.[49]

Changes in versification

In the first 30 chapters of the Book of Genesis, the following changes were made:[50]

|

|

Sixto-Clementine Vulgate

After Clement VIII had recalled all the copies of the Sixtine Vulgate in 1592,[4][5] in November of that year he published a new official version of the Vulgate known as the Clementine Vulgate,[51][52] also called the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.[52][30] Faced with about six thousand corrections on matters of detail, and a hundred that were important, and wishing to save the honour of Sixtus V, Bellarmine undertook the writing of the preface of this edition. He ascribed all the imperfections of Sixtus' Vulgate to press errors.[53][g] "However, a weak possibility remains that Sixtus V, who we know worked until the last day of his life to purge his Bible of the printing mistakes it contained, had let slip a few words which were heard by his familiars, of which Angelo Rocca was, and making think that he was planning a reedition."[54]

Scrivener notes: "To avoid the appearance of a conflict between the two Popes, the Clementine Bible was boldly published under the name of Sixtus, with a preface by Bellarmine asserting that Sixtus had intended to bring out a new edition in consequence of errors that had occurred in the printing of the first, but had been prevented by death; now, in accordance with his desire, the work was completed by his successor."[4]

The full name of the Clementine Vulgate was: Biblia sacra Vulgatae Editionis, Sixti Quinti Pont. Max. iussu recognita atque edita[32][29][47][31] (translation:"The Holy Bible of the Common/Vulgate Edition identified and published by the order of Pope Sixtus V.")[31] The fact that the Clementine edition retained the name of Sixtus on its title page is the reason why the Clementine Vulgate is sometimes known as the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.[31]

Nestle notes: "It may be added that the first edition to contain the names of both the Popes [Sixtus V and Clement VIII] upon the title page is that of 1604. The title runs: 'Sixti V. Pont. Max. iussu recognita et Clementis VIII. auctoritate edita'."[55] Hasting also points out that "[t]he regular form of title in a modern Vulgate Bible — 'Biblia Sacra Vulgatae Editionis Sixti V. Pont. Max. jussu recognita et Clementis VIII. auctoritate edita' — cannot be traced at present earlier than 1604; up to that time Sixtus seems to have appeared alon upon the title page; later, Clement occasionally figures by himself."[5]

See also

Notes

- ^ Literally "in the most correct manner possible"

- ^ Fourth session - Decree concerning the edition, and the use, of the sacred books

- ^ "The basis of the Committee's edition was actually the 1583 Lucas edition. Carafa was able to offer an emended text that contained "ten-thousand interpolations." Pope Sixtus had, however, disregarded the Committee's preparatory work and had, on his own initiative, promulgated an edition which was even closer to the Leuven Vulgate, the so called Vulgata Sixtina, in 1590."[23]

- ^ For a critique of this work of Le Bachalet, see The Journal of Theological Studies, Vol. 14, No. 55 (April, 1913), pp. 472-474.

- ^ "However, this work (the Vulgata Sixtina) was not appreciated by the Congregation of the Cardinals and a week after the death of Pope Sixtus V (27 August 1590) they ordered, first, the suspension of the selling of this edition and the destruction of the printed copies shortly thereafter."[30]

- ^ "Bellarmine's intellectual efforts gained him a more central position within the Roman Curia but he also encountered dangerous setbacks. In 1587 he became a member of the Congregation of the Index and in 1598 became one of the consultores of the Inquisition. Meanwhile, the implications of the doctrine of potestas indirecta angered Pope Sixtus V, who often opposed the Society of Jesus because he thought the Society's doctrines diminished the authority of the bishop of Rome. In 1589–90 Sixtus moved to put Volume 1 of Controversiae on the Index of Prohibited Books while Bellarmine was in France on a diplomatic mission. However, the Congregation of the Index and, later, the Society of Jesus resisted this. In 1590 Sixtus died, and with him the project of the Sistine Index also died."[38]

- ^ See also Bellarmine's testimony in his autobiography:

In 1591, Gregory XIV wondered what to do about the Bible published by Sixtus V, where so many things had been wrongly corrected. There was no lack of serious men who were in favor of a public condemnation. But, in the presence of the Sovereign Pontiff, I demonstrated that this edition should not be prohibited, but only corrected in such a way that, in order to save the honor of Sixtus V, it be republished amended: this would be accomplished by making disappear as soon as possible the unfortunate modifications, and by reprinting under the name of this Pontiff this new version with a preface where it would be explained that, in the first edition, because of the haste that had been brought, some errors were made through the fault either of printers or of other people. This is how I returned good for evil to Pope Sixtus. Sixtus, indeed, because of my thesis on the direct power of the Pope, had put my Controversies on the Index of Prohibited Books until after correction; but as soon as he died, the Sacred Congregation of Rites ordered my name to be removed from the Index. My advice pleased Pope Gregory. He created a Congregation to quickly revise the Sistine version and to bring it closer to the vulgates in circulation, in particular that of Leuven. [...] After the death of Gregory (XIV) and Innocent (V), Clement VIII edited this revised Bible, under the name of Sixtus (V), with the Preface of which I am the author.Bellarmino, Roberto Francesco Romolo (1999). "Memorie autobiografiche (1613)". In Giustiniani, Pasquale (ed.). Autobiografia (1613) (in Italian). Translated by Galeota, Gustavo. Internet Archive. Brescia: Morcelliana. pp. 59–60. ISBN 88-372-1732-3.

(in original Latin: Vita ven. Roberti cardinalis Bellarmini, pp. 30–31); (in French here, pp. 106–107)

References

- ^ a b Aland, Kurt; Nestle, Eberhard, eds. (2012). Novum Testamentum Graece. Chapters: "III. Der kritische Apparat", section 'Die lateinischen Übersetzungen'; & "III. The Critical Apparatus", section 'Latin Versions' (28 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. pp. 25, 69.

- ^ Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). "Novum Testamentum Graece26 (Nestle-Aland26 )". The Text of the New Testament. Translated by F. Rhodes, Erroll. [Der Text Des Neuen Testaments] (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

The various editions of the Vulgate are indicated by the following abbreviations when information about their text is necessary or informative: vgs for the Sixtine edition (Rome: 1590); vgcl for the Clementine edition (Rome: 1592) (vgs is not indicated independently when its text agrees with vgcl).

- ^ Wordsworth, John; White, Henry Julian, eds. (1889). "Praefatio editorum Prolegomenorum loco Euangeliis Praemissa (Cap. VI. Editiones saepius uel perpetuo citatae.)". Nouum Testamentum Domini nostri Jesu Christi latine, secundum editionem Sancti Hieronymi. Vol. 1. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. xxix.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose (1894). "Chapter III. Latin versions". In Miller, Edward (ed.). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 64.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hastings, James (2004) [1898]. "Vulgate". A Dictionary of the Bible. Vol. 4, Part 2 (Shimrath - Zuzim). Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific. p. 881. ISBN 9781410217295.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Weber, Robert; Gryson, Roger, eds. (2007). "Index codicum et editionum". Biblia sacra : iuxta Vulgatam versionem. Oliver Wendell Holmes Library Phillips Academy (5 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. pp. XLV, XLVII, XLVIII. ISBN 978-3-438-05303-9.

- ^ a b c d e Metzger (1977), p. 348.

- ^ a b c d Bungener, Félix (1855). History of the Council of Trent. Columbia University Libraries. New York, Harper. pp. 91.

- ^ Berger, Samuel (1879). La Bible au seizième siècle: Étude sur les origines de la critique biblique (in French). Paris. p. 147 ff. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Quentin (1922), p. 148, "Chapitre sixième - Les commissions pontificales du concilde de Trente à Sixte-Quint" [Chapter Six - The Pontifical Committees from the Council of Trent to Sixtus Quintus]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ a b c "Catholic Encyclopedia: Pope Sixtus V". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ Gerace (2016), pp. 210, 225.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gerace (2016), p. 210.

- ^ a b c Quentin (1922), p. 160, "Chapitre sixième - Les commissions pontificales du concilde de Trente à Sixte-Quint" [Chapter Six - The Pontifical Committees from the Council of Trent to Sixtus Quintus]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Vercellone, Carlo (1860). Variae lectiones Vulgatae Latinae Bibliorum editionis (in Latin). Harvard University. I. Spithöver. pp. XXII.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Quentin (1922), p. 168, "Chapitre sixième - Les commissions pontificales du concilde de Trente à Sixte-Quint" [Chapter Six - The Pontifical Committees from the Council of Trent to Sixtus Quintus]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Bady, Guillaume (13 February 2014). "La Septante est née en 1587, ou quelques surprises de l'édition sixtine". La Bibile D'Alexandrie (in French). Retrieved 11 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Quentin (1922), p. 181, Chapitre septième - Les éditions sixtine et Clémentine (1590-1592) [Chapter seven - The Sixtine and Clementine editions (1590-1592)]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ a b Quentin (1922), p. 170, "Chapitre sixième - Les commissions pontificales du concilde de Trente à Sixte-Quint" [Chapter Six - The Pontifical Committees from the Council of Trent to Sixtus Quintus]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Gerace (2016), p. 224.

- ^ a b c Kenyon, Frederic G. (1903). "Chapter IX. The Vulgate in the Middle Ages". Our Bible and the ancient manuscripts; being a history of the text and its translations. University of Chicago (4th ed.). London, New York [etc.]: Eyre and Spottiswoode. pp. 187.

- ^ Quentin, p. 182.

- ^ Gerace (2016), pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b Gandil, Pierre (April–July 2002). "La Bible latine : de la Vetus latina à la Néo-Vulgate". www.revue-resurrection.org (in French). Résurrection | N° 99-100 : La traduction de la Bible. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Carlo Vercellone, Variae lectiones Vulgatae Latinae Bibliorum editionis, Romae 1860, p. XXX.

- ^ Quentin (1922), p. 8, "Chapitre premier - Les témoins interrogés" [Chapter One - The Witnesses Consulted]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Quentin (1922), p. 190, Chapitre septième - Les éditions sixtine et Clémentine (1590-1592) [Chapter seven - The Sixtine and Clementine editions (1590-1592)]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ a b Le Bachalet, Xavier-Marie, Bellarmin et la Bible Sixto-Clémentine : Étude et documents inédits, Paris: Gabriel Beauchesne & Cie, 1911 (in French). The majority of this work is reproduced at the bottom of this article ("Annexe 1 – Etude du Révérend Père Le Bachelet (1911)").

- ^ a b c d e "Vulgate in the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia". International Standard Bible Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Gerace (2016), p. 225.

- ^ a b c d e Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). "Editions and Resources". The Latin New Testament: A Guide to Its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780198744733.

- ^ a b Delville, Jean-Pierre (2008). "L'évolution des Vulgates et la composition de nouvelles versions latines de la Bible au XVIe siècle". In Gomez-Géraud, Marie-Christine (ed.). Biblia (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 80. ISBN 9782840505372.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). "The Latin versions". The Text of the New Testament. Translated by F. Rhodes, Erroll. [Der Text Des Neuen Testaments] (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

Vulgate is the name given the form of the Latin text which has been widely circulated (vulgata) in the Latin church since the seventh century, enjoying recognition as the officially authoritative text, first in the edition of Pope Sixtus V (Rome, 1590), and then of Pope Clement VIII (Rome, 1592), until the Neo-Vulgate.

- ^ Thomson, Francis J. (2005). "The Legacy of SS Cyril and Methodius in the Counter Reformation" (PDF). In Konstantinou, Evangelos (ed.). Methodios und Kyrillos in ihrer europäischen Dimension. Peter Lang. p. 86.

- ^ Nestle, Eberhard (1901). Menzies, Allan (ed.). Introduction to the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament. Translated by Edie, William. University of California Libraries (2 ed.). London [etc.] Williams and Norgate; New York, G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 128.

- ^ Gerace (2016), pp. 223–225.

- ^ Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan (1996). "Catalog of Exhibition [Item 1.14]". The reformation of the Bible, the Bible of the Reformation. Dallas : Bridwell Library ; Internet Archive. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 98.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Bellarmine, Robert (2012). Tutino, Stefania (ed.). "On Temporal and Spiritual Authority". Online Library of Liberty. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Metzger (1977), pp. 348–349.

- ^ Quentin (1922), pp. 190–191, Chapitre septième - Les éditions sixtine et Clémentine (1590-1592) [Chapter seven - The Sixtine and Clementine editions (1590-1592)]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Le Bachalet, Xavier-Marie, Bellarmin et la Bible Sixto-Clémentine : Étude et documents inédits, Paris: Gabriel Beauchesne & Cie, 1911 (in French). The majority of this work is reproduced at the bottom of this article ("ANNEXE 1 – Etude du Révérend Père Le Bachelet (1911)").

"Votre Sainteté sait encore dans quel danger Sixte-Quint, de sainte mémoire, se mit lui-même et mit toute l'Eglise, en voulant corriger la Bible d'après son propre jugement, et pour moi je ne sais vraiment pas s'il y eut jamais plus grand danger." - ^ Vacant, Alfred; Mangenot, Eugene; Amann, Emile (1908). "Bellarmin". Dictionnaire de théologie catholique : contenant l'exposé des doctrines de la théologie catholique, leurs preuves et leur histoire (in French). Vol. 2. University of Ottawa (2nd ed.). Paris: Letouzey et Ané. p. 564.

- ^ Ess, Leander van (1824). Pragmatisch-kritische Geschichte der Vulgata im Allgemeinen, und zunächst in Beziehung auf das Trientische Decret: oder: Ist der Katholik gesetzlich an die Vulgata gebunden? Preisschrift (in Latin). Ludwig Friedrich Fues. p. 290.

Novit beatitudo vestra cui se totamque ecclesiam discrimini commiserit Sixtus V. dum juxta propriae doctrinae sensus sacrorum bibliorum emendationem aggressus est; nec satis scio an gravius unquam periculum occurrerit

- ^ Le Blanc, Augustino (1700). "De auxilis lib. II. Cap. XXVI.". Historiae Congregationum De Auxiliis Divinae Gratiae, Sub Summis Pontificibus Clemente VIII. Et Paulo V. Libri Quatuor: Quibus ... confutantur recentiores hujus Historiae Depravatores, maximè verò Autor Libelli Gallicè inscripti, Remonstrance à M. l'Archevêque de Reims, sur son Ordonnnance du 15. Juillet 1697. ... (in Latin). Leuven: Denique. p. 326.

Novit Beatitudo Vestra, cui se totamque ecclesiam discrimini commiserit Sixtus V. sum juxta propriæ doctrinæ sensus, sacrorum Bibliorum emendationem aggressus est: nec fatisscio an gravius unquam periculum occurerit.

- ^ Kenyon, Frederic G. (1903). "Chapter IX. The Vulgate in the Middle Ages". Our Bible and the ancient manuscripts; being a history of the text and its translations. University of Chicago (4th ed.). London, New York [etc.]: Eyre and Spottiswoode. pp. 187–188.

- ^ "Sixtus", 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 25, retrieved 23 September 2019

- ^ a b Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan (1996). "1 : Sacred Philology". The reformation of the Bible, the Bible of the Reformation. Dallas : Bridwell Library ; Internet Archive. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Quentin (1922), pp. 184–185. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Quentin (1922), p. 185"Sur ces 43 corrections, 31 ne sont que des changements d'orthographe dont 6, il est vrai, portent sur des noms propres [...]" sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Quentin (1922), p. 189. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Metzger (1977), p. 349.

- ^ a b Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan (1996). "1 : Sacred Philology ; Catalog of Exhibition [Item 1.14]". The reformation of the Bible, the Bible of the Reformation. Dallas : Bridwell Library ; Internet Archive. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 14, 98.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bungener, Félix (1855). History of the Council of Trent. Harper and Brothers. pp. 92.

- ^ Quentin (1922), pp. 200–201, Chapitre septième - Les éditions sixtine et Clémentine (1590-1592) [Chapter seven - The Sixtine and Clementine editions (1590-1592)]. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFQuentin1922 (help)

- ^ Nestle, Eberhard (1901). "Chapter II.". In Menzies, Allan (ed.). Introduction to the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament. Translated by Edie, William. University of California Libraries (2nd ed.). London [etc.] Williams and Norgate; New York, G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 128.

Citations

- Gerace, Antonio (2016). "Francis Lucas 'of Bruges' and Textual Criticism of the Vulgate before and after the Sixto-Clementine (1592)". Journal of Early Modern Christianity. 3 (2). doi:10.1515/jemc-2016-0008 – via KULeuven.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Metzger, Bruce M. (1977). "VII The Latin Versions". The Early Versions of the New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Quentin, Henri (1922). Mémoire sur l'établissement du texte de la Vulgate (in French). Rome: Desclée. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

Works about the Vulgate Sixtina

- Carlo Vercellone (1860). Variae lectiones Vulgatae Latinae Bibliorum editionis (in Latin). Harvard University. Rome: I. Spithöver.

- Baumgarten, Paul Maria (1911). Die Vulgata Sixtina von 1590 und ihre Einführungsbulle Aktenstücke und Untersuchungen. Münster i. W.: Aschendorff. (online references)

- Amann, Fridolin (1911). Die Vulgata Sixtina von 1590: Eine quellenmässige Darstellung ihrer Geschichte. Münster i. W.: Aschendorff. (online references)

- Quentin, Henri (1922). Mémoire sur l'établissement du texte de la Vulgate (in French). Rome: Desclée. pp. 168 ff. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Steinmeuller, John E. (1938). "The History of the Latin Vulgate". CatholicCulture. Homiletic & Pastoral Review. pp. 252–257. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Gordon, Bruce; McLean, Matthew, eds. (2012). Shaping the Bible in the Reformation: Books, Scholars and Their Readers in the Sixteenth Century. Boston: BRILL. ISBN 9789004229501.

Miscellaneous

- Notice on the website of the Bodleian Libraries: Biblia sacra Vulgatae editionis tribus tomis distincta.

- Notice on the website of the Morgan Library and Museum: here

External links

- Biblia sacra Vulgatae editionis tribus tomis distincta / Biblia sacra vulgatae editionis : ad concilii tridentini praescriptum emendata et a Sixto V recognita et approbata. Ex Typographia Apostolica Vaticana. 1590. (bad quality scan)

- van Ess, Leander, ed. (1822–1824). Biblia Sacra, Vulgatæ Editionis, Sixti V et Clementis VIII, 1590, 1592, 1593, 1598.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) (edition of the 1592 version of the Vulgate with variations from the two other subsequent editions (1593 and 1598) as well as of the 1590 Sixtine Vulgate) - Bull Aeternus Ille (in Latin)