KFOR-TV: Difference between revisions

Tag: Reverted |

Tags: Manual revert Reverted |

||

| Line 164: | Line 164: | ||

== Local programming == |

== Local programming == |

||

[[Broadcast syndication|Syndicated]] programs broadcast by |

[[Broadcast syndication|Syndicated]] programs broadcast by KFOR-TV {{as of|November 2021|lc=y}} include ''[[Right This Minute]]'', ''[[Rachael Ray (talk show)|Rachael Ray]]'', ''[[The Drew Barrymore Show]]'' and ''[[Jeopardy!]]''. |

||

=== Newscasts === |

=== Newscasts === |

||

{{Quote box |

{{Quote box |

||

Revision as of 15:40, 4 November 2021

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (October 2021) |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| Channels | |

| Branding | Oklahoma's News 4 |

| Programming | |

| Affiliations |

|

| Ownership | |

| Owner | |

| KAUT-TV | |

| History | |

First air date | June 6, 1949 |

Former call signs |

|

Former channel number(s) |

|

Call sign meaning | Channel FOuR[1] |

| Technical information[2] | |

Licensing authority | FCC |

| Facility ID | 66222 |

| ERP | |

| HAAT | 467 m (1,532 ft) |

| Transmitter coordinates | 35°34′7″N 97°29′21″W / 35.56861°N 97.48917°W |

| Translator(s) | See § Translators |

| Links | |

Public license information | |

| Website | kfor |

KFOR-TV, virtual channel 4 (UHF digital channel 27), is an NBC-affiliated television station licensed to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States. Owned by Irving, Texas-based Nexstar Media Group, it is part of a duopoly with independent station KAUT-TV (channel 43). Both stations share studios in Oklahoma City's McCourry Heights section, which is where KFOR-TV's transmitter is separately located.

As Oklahoma's first television station, KFOR-TV signed on in June 1949 as WKY-TV, the television extension to WKY (930 AM). In its early years, WKY-TV boasted several regional and national technical firsts: it was the first independently-owned network affiliate to directly originate color programs, the first station to operate a mobile broadcasting unit for live event coverage, the first station to broadcast legislative sessions and cover court proceedings, and the first television station to broadcast a tornado warning. Originally owned by the Oklahoma Publishing Company, a direct predecessor to Gaylord Broadcasting, the station became KTVY in 1976 and KFOR-TV in 1990.

History

WKY-TV

Edward K. Gaylord's vision

There is no outlook now for telecasting here, developments are coming every day, but the time is yet fairly distant... When television is practicable on a local scale, WKY, which led the radio field here, will install the necessary machinery.

Edgar T. Bell, Oklahoma Publishing Co. general manager, November 17, 1939[3]

Fascinated with the medium since the late 1930s, Edward K. Gaylord's April 13, 1936, dedication to new studios at the Skirvin Tower Hotel for his radio station, WKY, ended with a public pledge to bring television to Oklahoma when it and other related inventions had been perfected.[4][5] With his Oklahoma Publishing Company (OPUBCO), Gaylord published both the morning Daily Oklahoman and evening Oklahoma Times newspapers, and had purchased WKY—established in 1922 as Oklahoma's first radio station[note 1]—in 1928, successfully turning a profit for the station within two years.[6] His pledge soon manifest itself on an exhibitory basis in mid-November 1939[7] when OPUBCO sponsored a six-day demonstration of telecasts and broadcast equipment at the Oklahoma City Municipal Auditorium in downtown Oklahoma City, now the Civic Center Music Hall.[8][9] With equipment set up and operated by RCA engineers,[10] the event featured appearances by performers from NBC and WKY[11][12] with attendees given an opportunity to be "televised" to other attendees watching television sets throughout the auditorium.[13] OPUBCO executive Edgar T. Bell downplayed the immediate outlook for local television as "distant" despite well-received attendance for the exhibition; estimates had as many as 25,000 attendees on Thursday, taxing the auditorium's capacity.[3] During November and early December 1944, OPUBCO conducted a similar, 19-city television exhibition tour across central and western Oklahoma[14]—open to residents who had purchased war bonds, as well as for attendees that wished to purchase them—that included performances from WKY personalities and demonstrations by television technicians.[15] The tour was attended by a total of 50,000 bond buyers with crowd size regarded as large throughout,[16] several cities even saw encore performances due to overwhelming demand.[17]

We knew we'd lose money.... I expected it would take at least 90 days of red tape up there in Washington, but we got approval almost by return mail.

Edward K. Gaylord, recounting the 1948 application for WKY-TV's license[18]

Gaylord submitted a permit application to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) on April 14, 1948[19][20] for a television station on VHF channel 4.[21] Upon filing, Gaylord estimated any financial loss for the TV station would be offset within two years, echoing how WKY turned a profit two years after being purchased by OPUBCO.[7]: 34 The FCC granted the license to Gaylord on June 2, 1948[22] with the station assigned the WKY-TV call sign, joining WKY and WKY-FM (98.9), which signed on in July 1947.[23] Studio facilities for WKY-TV were based at the Municipal Auditorium—WKY's studios remained at the nearby Skirvin Tower Hotel—with production facilities on the second floor in the Little Theatre.[24][7]: 36 Prior to launch, a fire to the theatre on November 17, 1948, resulted in $150,000 in damage[25] with most of the technical and production equipment replaced during renovations to the theatre that followed; soundproofing material was also added to limit disruptions between television productions and stage productions.[26]

While assembling the TV transmitter antenna onto WKY's 968 feet (295 m) broadcast tower in April 1949, an accident occurred when the antenna fell 8 feet (2.4 m) while being hoisted upward; the antenna suffered minimal damage[27] but added to delays earlier in the month due to inclement weather.[28] Daily test broadcasts over WKY-TV began on April 21 consisting of music played over a test pattern slide,[12] enabling television set owners in Oklahoma and neighboring states to contact the station to report signal reception.[29] The test signal operated at low power for three days following a lightning strike to a junction box on the tower on April 27.[30] Closed-circuit transmissions began on May 27 with a wrestling match at the Stockyards Coliseum[31] along with two weeks worth of dress rehearsals between the local performers and show producers.[32]

A 'pioneer station'

WKY-TV's inaugural broadcast on June 6, 1949, included speeches from Gaylord, executive vice president/general manager Proctor A. "Buddy" Sugg and Governor Roy J. Turner, a short feature on the new medium by Gaylord and Sugg and a film outlining programs WKY-TV would air.[33] Gaylord boasted during his on-air address that WKY-TV had both the finest television studio in the country and the tallest transmission tower outside of NBC's transmitter for WNBT atop the Empire State Building.[34][7]: 43 The station was the first to sign on in the state of Oklahoma and the 65th station in the United States to sign on.[35] "Television parties" occurred throughout the city and state as people suspended or heavily curtailed their regular activities to watch the new station in homes, laundromats, bars, appliance stores and other businesses;[36][7]: 44 in Tulsa, approximately 1,000 people sat outside of a store to watch the transmissions.[37]

Broadcasting over WKY-TV was originally limited to two and a half hours every night, Saturday excluded.[7]: 45 Saturday transmissions began on February 11, 1950, and a morning schedule was added by 1951, giving the station 90 cumulative hours of weekly programming.[38] As WKY had been an NBC Radio Network affiliate since December 1928, WKY-TV debuted with the market's NBC-TV affiliation along with supplemental CBS-TV and ABC-TV clearances.[39] Due to Oklahoma City not being connected yet to transcontinental coaxial cables, a process AT&T estimated could take another two years to complete,[35] all network programming had to be via film and kinescope.[39] A short feature NBC prepared welcoming WKY-TV to the network aired on the station's debut night,[33] while the first NBC program, Who Said That?, was broadcast via kinescope on June 17.[18] The station additionally carried select programming from DuMont and the Paramount Television Network, the latter from 1950 until ceasing operations in 1953.[40]

Channel 4's initial local programming included some WKY shows that were adapted for television, including variety series Wiley and Gene hosted by Wiley Walker and Gene Sullivan, and children's program The Adventures of Gismo Goodkin hosted by puppeteer—and high school senior—Robert Jerkins.[41] Oklahoma Times scribe R. G. Miller hosted the weekly Smoking Room that was an extension of his newspaper column.[42] Danny Williams joined WKY-TV in 1950 to host a daily talk show, announce professional wrestling telecasts, and appear as Spavinaw Spoofkin on Gismo Goodkin.[43] Williams later fronted children's program The Adventures of 3-D Danny as "Supreme Galaxy Chief Dan D. Dynamo", incorporating science fiction and time travel elements derived from Flash Gordon with cartoon short subjects.[44][45] Airing on WKY-TV from 1953 to 1959, the ratings for 3-D Danny often beat those of ABC's The Mickey Mouse Club,[46] making it the first local television program in the country to achieve that feat.[44]

Sports quickly became a fixture at the station, with high school basketball,[47] football, golf and softball matches all broadcast within the first year.[48] WKY-TV reached a deal to broadcast all ten Oklahoma Sooners football games for the 1949 season, with all home games airing live starting with the October 1 Texas A&M Aggies matchup at Owen Field.[49] Oklahoma A&M Aggies football was subsequently added, but with all of their games recorded on film.[50] WKY-TV also originated Bud Wilkinson's Football starting in September 1953.[51] The first college football analysis program, it featured the Sooners' three-time national championship head coach discussing the previous week's game,[52] a necessity after the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) enacted guidelines limiting live television coverage of college football.[53] Wilkinson also hosted Sports for the Family starting in 1954 that focused on a variety of sports, filmed and packaged for syndication to television stations around the U.S.[54] Among the play-by-play announcers for these shows was Ross Porter, starting with the 1960 season at age 21;[55] already a WKY news reporter, Porter would soon emerge as WKY-TV's sports director until leaving for Los Angeles in 1966.[56][57] Under varying titles to 1963, Wilkinson's shows on WKY-TV helped boost awareness of the Sooners' football program and encourage physical fitness, with Wilkinson rejecting most advertising in favor of National Guard PSAs.[52] Football was not the only college sport WKY-TV covered, a 1966 wrestling match between the Sooners and the Oklahoma State University Cowboys became the first of its kind to be televised live.[58]

After OPUBCO declined to renew the lease for WKY's studios in the Skirvin, plans were made to combine it and WKY-TV's operations into a combined studio facility[59] on Britton Road east of the transmission towers for both stations, as well as WKY-FM.[7]: 46 Ground was broken for the studios on July 10, 1950, with WKY moving into the facility on March 26, 1951;[5]: 37–38 WKY-TV followed suit by July 17.[60] The new facility included television soundstages engineered to also allow origination of radio programs over WKY.[61] The AT&T coaxial cable network was completed in 1952, WKY-TV was able to link to the network via microwave relays from Dallas.[62] The milestone was inaugurated the morning of July 1, 1952, with Gaylord giving a short message and pressing a button to activate the network connections, joining NBC's Today live in progress.[63] With this, WKY-TV was able to sign on at 7 a.m. daily, increasing its programming to 111 hours per week.[7]: 46 [64] Gaylord's predictions of financial shortfalls for the station being offset after two years came to pass, as WKY-TV lost $270,000 between 1949 and 1950, then turned a profit in 1951.[65]

OPUBCO successfully challenged the FCC over their Sixth Report and Order[note 2] that proposed the channel 4 allocation be reassigned to Tulsa and WKY-TV move to channel 7, citing engineering costs, possible effects on the AM station's transmissions, and a need for viewers to replace existing outdoor antennas.[66] The FCC rescinded the frequency change request in April 1952, noting WKY-TV would have enough feasible co-channel assignment separation from Dallas's KRLD-TV; the channel 7 allocation was reassigned to Lawton for use by KSWO-TV.[67] Due to the FCC's 1948 licensing freeze, WKY-TV was the only television station in Oklahoma City until 1953, when UHF-based competitors—KTVQ and KMPT "KLPR-TV"—debuted on October 28 and November 8. Though KTVQ and KMPT respectively signed on as basic ABC and DuMont affiliates, channel 4 continued to carry selected programs from both networks;[68] in contrast, WKY disaffiliated from CBS on December 20, one month prior to KWTV (channel 9) signing on.[69] At the same time, OPUBCO donated $150,000 worth of existing WKY-TV equipment to the Oklahoma Educational Television Authority (OETA) for its proposed Oklahoma City station, KETA-TV (channel 13), which signed on in April 1956.[70][71] WKY-TV carried select DuMont fare until that network discontinued operations in August 1956, while ABC programming left in March 1958 when Enid-licensed ABC affiliate KGEO-TV (channel 5) changed call letters to KOCO-TV and refocused its coverage area to include Oklahoma City.[72]

Broadcasting in living color

Once viewers observe color telecasts they will feel it is far more revolutionary than was the beginning of regular televising in the first place. Color will add a whole new perception and dimension to television that will certainly justify immediate viewer acceptance.

P. A. Sugg, WKY-TV general manager[73]

WKY-TV was the first television station not owned by a network to produce and transmit local programs in color. Before the FCC had even approved a color transmission standard, Gaylord ordered color equipment from RCA—including two TK-40 color cameras—in September 1949.[75] By March 1954, the equipment was delivered and installed,[76] and WKY-TV was successfully receiving color programming from NBC via a separate microwave relay system, as the coaxial cable network was incompatible for color.[73] OPUBCO had a special exhibition at the Municipal Auditorium's Home Show on April 4, 1954, where 30 patrons watched a color set displaying The Paul Winchell Show, one of three color programs NBC was regularly transmitting for testing purposes and the station's first color telecast.[77] The station's first local colorcast occurred on April 8 with a live five-minute message from E. K. Gaylord,[78] followed by a half-hour sponsored variety show on April 21.[79][80] With the hour-long Cook's Book becoming the first regularly scheduled weekday colorcast on April 26,[81][7]: 46 WKY-TV carried more programming in color than all of the networks combined.[82] NBC's color coordinator Barry Wood even remarked that WKY-TV's color output was of better quality than the network itself.[83]

The station became the first network affiliate to provide live color programming to a network[7]: 46 on August 17, 1954, when a feed of the American Indian Exposition in Anadarko was sent to NBC;[84] the ten-minute segments on Today and Home featured participants dressed in tribal "war dance" regalia.[85][86] On April 23, 1955, WKY-TV produced Square Dance Festival for NBC, showcasing the National Square Dance convention at Municipal Auditorium, the first full-length color program fed to a network by an affiliate.[87] Also in 1955, the station transmitted to the network a surgical procedure in color via closed-circuit[88] four years after becoming the first station in Oklahoma to broadcast a surgery on-air.[89] In 1958, WKY-TV became one of the first local television stations in the U.S. to acquire a videotape recorder, intended for the news department but also used for some show production. One videotaped show, the Stars and Stripes Show, premiered on NBC that year as the first network television program to be produced by a local station.[7]: 47

WKY-TV and the Lions Club of Oklahoma collaborated on Gift of God, a December 2, 1957, program profiling medical and legal aspects of corneal transplants through the perspective of an organ donor's eyes transported 150 miles (240 km) to an operating room, concluding with a film of a successful transplant.[90] An appeal then aired for viewers wishing to become organ donors to join a statewide eye bank established by the Lions Sight Conservation Foundation initiative; 700 donor card requests were received by the bank 90 minutes after the program aired, including one signed by then-Oklahoma governor Raymond Gary,[91] the number increased to 2,000 cards after 48 hours.[90] The WKY-TV/Lions partnership lasted for four years with more than 16,400 volunteer donor cards signed, with 346 Oklahomans—including two who underwent surgery within 48 hours of the broadcast—having successful corneal transplants.[91]

Long-running local shows

Another children's show with a similar local impact to 3-D Danny was Foreman Scotty's Circle 4 Ranch, hosted by Steve Powell as the titular cowboy. Airing from 1957 to 1971, Scotty's supporting characters included Danny Williams as sidekick Xavier T. Willard;[46] Powell, with Williams, had additionally teamed up to host WKY-TV's The Giant Kids Matinee. The show also featured prize giveaways including the Golden Horseshoe, whose winner was selected through the "Magic Lasso," a cut-out slide that was superimposed on-screen over the audience, and honorary rides on a wooden horse named Woody for children in the studio audience who were celebrating their birthday. At its peak, the show had a 1½-year backlog of kids who wanted to be part of the show's audience.[92][93]

During this era, the station featured an assortment of other noted locally-oriented fare. WKY host Don Wallace began hosting The Wallace Wildlife Show in 1965; a weekly fishing show that was the highest-rated program of its kind in the country from 1974–75, and ended after 920 episodes with Wallace's 1988 retirement.[95] The Scene, a Saturday afternoon music and dance show hosted by WKY personality Ronny Kaye,[96] aired from 1966 to 1974.[97] The Jude 'n' Jody Show, a country-variety program hosted by singers/furniture salespeople Jude Northcutt and Jody Taylor, aired on channel 4 and other Oklahoma City stations between 1954 and 1982.[98] Danny Williams returned to channel 4 in 1967 to host the local midday talk-variety show Dannysday, which enjoyed a 17-year run.[46] Among Williams' co-hosts included Mary Hart, who became a fan favorite on Dannysday from 1976 until leaving for Los Angeles at the end of 1979,[99] later becoming the co-host of Entertainment Tonight.[100] John Ferguson hosted three distinct horror movie showcases at the station under the horror host persona "Count Gregore": a local version of Shock Theater from 1958 to 1962,[101] Thriller Theater from 1962 to 1964 and Sleepwalker's Matinee from 1973 to 1979.[102] WKY-TV originated The Buck Owens Ranch Show from 1966 to 1973; seen in over 100 U.S. markets, the half-hour country-variety show was the most successful of its kind not produced in Nashville.[94] In addition to hosting the Ranch Show, Owens was paired with Roy Clark in 1969 to host the similar-themed Hee Haw on CBS,[103] which was relaunched as a syndicated show in 1971.[104][105] As the result of a renegotiated contract, Yongestreet Productions forced Owens to discontinue the Ranch Show due to heavy music and content duplication with Hee Haw.[94]

Through its WKY Radiophone Company subsidiary, the Oklahoma Publishing Company eventually acquired or launched other television and radio stations during and after its stewardship of WKY-TV, including Montgomery's WSFA-TV and WSFA (1440 AM) in 1955,[106][107] Tampa's WTVT in 1956, Milwaukee's WUHF-TV in 1966, KTVT in Fort Worth in 1962,[108] Houston's KHTV in 1967, and Tacoma's KTNT-TV in 1973.[109][110] WKY-TV served as the company's flagship station, and in October 1956, OPUBCO renamed its broadcast group the WKY Television System.[111][112] After Edward K. Gaylord's death at the age of 101 on May 30, 1974, control of OPUBCO was transferred to son Edward L. Gaylord.[113]

KTVY

...at that time period we were successful in selling the station to close business people that we knew well—The Detroit Evening News—and we knew their type of operation was similar to ours. They had agreed that they would take care of our people who were long-term employees of the station, and we also got a very handsome sales price for it.

Jim Terrell, Gaylord Broadcasting president, on why WKY-TV was sold to the Evening News Association in 1975[5]: 39–40

OPUBCO sold WKY-TV to the Evening News Association on July 16, 1975, for $22.697 million; this included $197,000 for upgrades to the studio building.[114] WKY-TV was sold after the FCC adopted cross-ownership rules preventing the same company from owning newspapers and broadcast outlets in the same market.[115] While Oklahoma City was not one of 16 markets the FCC had planned to strictly enforce this rule, the sale happened under the possibility, with OPUBCO preferring Evening News as the buyer since it also was a newspaper publisher-turned-broadcaster.[5]: 39–40 Additionally, Oklahoma City was the smallest market in which the company owned a TV station.[112] WKY, the Oklahoman, and the Times were all retained by OPUBCO, which planned to purchase additional TV and radio stations with the sale proceeds[115] under the newly renamed Gaylord Broadcasting division.[116] As OPUBCO/Gaylord retained the rights to the WKY call sign,[115] WKY-TV was rechristened as KTVY on January 5, 1976.[19]

Starting with the 1978 Oklahoma Sooners season, KTVY debuted The Oklahoma Playback, a next-day hour-long condensed recap of the most recent Sooners football game with wraparound segments co-hosted by then-head coach Barry Switzer.[117] Also regarded as a continuation of the Bud Wilkinson coaches shows by sponsor Kerr Magee, Tulsa's KTUL handled production for the 1980 season but became a KTVY production again in 1981 with sportscaster Ron Thulin as host.[118] This program—which was also syndicated throughout the Southwest and on cable—ended in 1984 after a successful legal challenge to the U.S. Supreme Court by the University of Oklahoma and then-Oklahoma City mayor Andy Coats against the NCAA restrictions over the number of games that could be televised live in a single season.[40] KTVY was occasionally granted exceptions to this rule, most notably with the 1983 Oklahoma-Texas rivalry game, which aired live on the station.[119] KTVY added Sooners college basketball coverage to the lineup in 1982.[120] Originally produced by KTVY and the university under a revenue-sharing deal, production subsequently was taken over by Raycom Sports under a larger deal with the Big Eight Conference in 1985;[121][122] the station continued to air ESPN Plus, though with KOCB airing more games to allow KFOR to fulfill NBC obligations,[123] until KOCB became the exclusive carrier in 2001.[124]

KTVY became the first television station in Oklahoma to broadcast in stereo on June 6, 1985; initially, the station broadcast NBC network programs, local programs and certain syndicated shows that were transmitted in the audio format.[125] Taking advantage of the new format, channel 4's daily sign-ons and sign-offs began to feature music videos, some of which were tailored to the station's public service campaigns.[126] That September, the station debuted another local talk show in the vein of Dannysday, which had ended its run the previous year:[127] AM Oklahoma, hosted by brothers Ben and Butch McCain, who were also KTVY's morning news and weather anchors, respectively.[128] The program was canceled in May 1986 after nine months, and the McCains ultimately left KTVY in June 1987 for KOCO-TV. A local version of PM Magazine had much better success, airing on KTVY from 1980 to 1988 with hosts Stan Miller, Karen Carney,[129] Dan Slocumb,[130] Dave Hood,[131] Kelly Robinson[132] and Becky Corbin.[133]

The Gannett Company purchased the Evening News Association on September 5, 1985, for $717 million,[134][135] thwarting a $566 million hostile takeover bid by L.P. Media Inc., owned by television producer Norman Lear and media executive A. Jerrold Perenchio.[136] Due to Gannett already owning KOCO-TV since their 1979 acquisition of Combined Communications,[128] KTVY, along with WALA-TV in Mobile, Alabama, and KOLD-TV in Tucson, Arizona, were sold to Knight Ridder Broadcasting for $160 million;[137][138] KTVY sold for a reported $80 million.[139] Knight Ridder subsequently announced in October 1988 their intent to sell their station group to help reduce a $929 million debt load[140] and finance a $353 million acquisition of online information provider Dialog Information Services.[141] Four months later, KTVY was sold to Palmer Communications, owner of WHO-TV in Des Moines and KWQC-TV in Davenport, Iowa,[142] for $50 million on February 27, 1989.[143][144]

KFOR-TV

It's up to us to give (the viewers) a reason to be loyal to us. People want to identify with that kind of thing. This is the foundation for a long-term future. KTVY kind of lost a sense of community, lost its heart. That's one of the reasons why we changed our call letters.

Bob Brooks, KFOR-TV program director[145]

After several weeks of on-air promotions that "TV reception in Oklahoma would get stronger,"[147] KTVY's call sign changed to KFOR-TV on April 22, 1990, at the start of their 10 p.m. newscast, coupled with an overhaul to the station's on-air presentation.[148] Station program director Bob Brooks explained in an interview that KTVY had lost "a sense of community, lost its heart" in recent years, and that was a driving force behind the call sign change;[145] management opted for calls that alluded to their dial position and new "4-Strong" branding.[1] As part of the change, the station altered their newscasts to have a statewide focus, with reporter Kelly Ogle filing a series of statewide reports during the May sweeps that management described as "a barnstorming approach to news."[149]

KFOR-TV began maintaining a 24-hour programming schedule seven days a week beginning on May 11, the additional programming included hourly local news updates, which was attributed to viewer demand;[150] the move was to have taken place on May 13 and was pushed up after management found out KOCO-TV was also planning to broadcast around the clock.[151] It was KFOR-TV's usage of the "24-Hour News Source" phrase that led KOCO-TV owner Gannett, which filed a 10-year service mark for the phrase on May 11—the same day KFOR-TV begin using it over the air—to sue Palmer Communications alleging trademark infringement.[152] Gannett claimed in court testimony that KFOR-TV's infringement of the phrase cost KOCO-TV $208,000 annually in lost revenue, while KFOR-TV argued that the phrase only described a programming service and was not an advertising slogan.[151] The lawsuit was eventually settled with KFOR-TV adopting a different promotional slogan.[153]

Palmer signed a letter of intent on November 7, 1991, to sell KFOR-TV and their Des Moines properties to Hughes Broadcasting Partners for $70.2 million;[154] Hughes was formed earlier that year with their purchase of WOKR-TV in Rochester, New York.[155] Palmer terminated the sale agreement was on April 2, 1992, after rejecting the bid submitted by Hughes Broadcasting.[156] In a lawsuit against Palmer, majority owner VS&A Communications Partners LP asked the Delaware Chancery Court to force Palmer, which claimed it had no binding obligation to negotiate or reach a formal agreement, into resuming negotiations to reach a definitive sale contract.[157] Hughes formally gave up its pursuit of the transaction[158] months after the judge presiding the case ruled that the agreement between VS&A and Palmer was not binding.[159] KFOR-TV and WHO-TV would ultimately be sold to The New York Times Company for $226 million on May 14, 1996;[160][161] KFOR in particular sold for $155 million.[162] The sale received FCC approval less than two months later on July 3 and was finalized on July 16.[163]

On June 13, 1998, the former transmitter tower for WKY and WKY-TV collapsed due to straight-line wind gusts near 105 mph (169 km/h) produced by a supercell thunderstorm that also spawned four tornadoes, a KWTV tower camera captured the collapse on-air.[164] Still in use as an auxiliary tower for KFOR-TV and WKY up to that point, the tower had been designed to withstand winds in excess of 125 mph (201 km/h).[165] Channel 4 had already moved off the tower in April 1965 when a 1,602-foot (488 m) mast was constructed off of Britton Road.[146]

The New York Times Company operated Pax TV station KOPX-TV (channel 62) from October 11, 2000, to July 1, 2005, via a joint sales agreement with Paxson Communications.[166][167] As part of the arrangement, KFOR handled advertising sales for KOPX, and KOPX rebroadcast KFOR's evening newscasts on a tape-delayed basis.[168] Several weeks after Paxson dissolved the KOPX joint sales agreement, the Times Company purchased UPN station KAUT-TV (channel 43) from Viacom Television Stations Group on November 4, 2005, for an undisclosed price.[169] The Times Company left television broadcasting altogether with the $530 million sale of their nine station group to Local TV LLC[170][171] the deal was finalized on May 7, 2007.[172] The Tribune Company—which formed a management company in December 2007 for their stations and those owned by Local TV—acquired Local TV LLC on July 1, 2013, for $2.75 billion,[173][174] this sale was completed on December 27.[175]

A new combined facility for KFOR-TV and KAUT was constructed adjacent to KFOR-TV's existing studios;[176] groundbreaking occurred in January 2015.[177] Completed in August 2017, the new building both boasted a floorplan improving workflow and employee collaboration, and was built with reinforced steel, concrete and protective glass that could withstand a direct hit from severe weather and enable unlimited broadcasting.[178] Several conference rooms in the new facility were named after former on-air staff—including the "Barry Huddle Room" in honor of Bob Barry Sr. and Bob Barry Jr.[179]—and the main studio was later named in honor of Linda Cavanaugh upon her December 15, 2017, retirement.[180] Along with the studio move, the station rebranded to Oklahoma's News 4 concurrent with a revised on-air presentation.[181]

Sinclair Broadcast Group agreed to acquire Tribune Media on May 8, 2017, for $3.9 billion, plus the assumption of $2.7 billion in debt held by Tribune.[182][183] As Sinclair already owned KOKH-TV and KOCB, the company agreed on April 24, 2018, to divest KOKH-TV to Standard Media as part of a $441.1 million group deal.[184] Howard Stirk Holdings also agreed to purchase KAUT for $750,000 that included shared services and joint sales agreements with Sinclair, which planned to retain KFOR-TV and KOCB.[185] All three transactions were nullified on August 9, 2018, after Tribune Media terminated the merger and filed a breach of contract lawsuit;[186] this came several weeks after the FCC voted to bring the deal up for a formal review and lead commissioner Ajit Pai publicly rejected it.[187]

Following the collapse of the Sinclair merger, Nexstar Media Group announced it would acquire Tribune Media in a $6.4 billion all-cash deal on December 3, 2018, which also included all outstanding Tribune debt.[188][189] Approved by the FCC on September 16, 2019, the merger was completed three days later.[190]

Local programming

Syndicated programs broadcast by KFOR-TV as of November 2021[update] include Right This Minute, Rachael Ray, The Drew Barrymore Show and Jeopardy!.

Newscasts

We try, and I think we have succeeded, in identifying our station with news. We like to feel that the two are synonymous. Our people are known personally by every news source in our immediate area... And of one thing I am convinced. An aggressive, competent news establishment can make a television station individually outstanding.

John Fields, WKY-TV news director[191]

Channel 4's news department began with the station on June 6, 1949, originally consisting of 10-minute-long newscasts at sign-on and sign-off, using wire copies of local news headlines read by anchors over still newspaper photographs.[193] WKY-TV's first news director Bruce Palmer saw the new medium as a way to provide immediacy to news coverage.[7]: 38–39 In a Daily Oklahoman op-ed Palmer penned the day before WKY-TV's launch, he not only foresaw television news using films and photographs to provide a newsreel-like method to storytelling, but that coaxial cable-driven networks would soon be able to relay major news events to stations nationwide.[194] Within a few years, WKY-TV employed a staff of 44 Oklahoma-based reporters and additional correspondents in three surrounding states[191] and was recognized in 1958 by the Radio and Television News Directors Association as the nation's "outstanding television news operation".[195] Ernie Schultz, who joined channel 4 in 1955 as a reporter and photographer, became news director and noon news anchor in 1964, and remained at the station until 1980.[196]

The television station's news department utilized WKY's news staff, including Frank McGee, who had joined WKY in 1947 and added duties on the TV side in 1950 under the air name "Mack Rogers";[192] during this time, WKY and WKY-TV used stage names for their airstaff that could be retained as intellectual property in the event an on-air personality were to leave the station.[197] In 1950, WKY-TV became one of the first television stations in the country to employ a mobile broadcasting unit to conduct live broadcasts that would be relayed to the Oklahoma City studio or to film on-scene footage for later broadcast.[38] The unit employed up to three cameras, one of which was stationed on a special platform on the bus's roof, and included a 12-inch television receiver built onto its side to display the direct-to-studio feed.[198] This unit was used to cover both the 1952 Oklahoma Republican and Democratic State Conventions,[58] relayed live from the Municipal Auditorium[70] and reported on by both McGee and John Fields.[198]

WKY-TV started broadcasting twice-weekly Oklahoma Legislature sessions from the State Capitol in January 1951, becoming the first station in the U.S. to provide coverage of state legislature sessions.[58][199] Channel 4 claimed to have made the fastest showing of any sound on film ever to have been processed and aired on television at the time, when on February 8, 1952, WKY-TV aired introductory remarks by anchor John Fields filmed 15 minutes prior to that evening's newscast. The Houston film processor used by the station allowed WKY-TV to broadcast news coverage only a few hours after it was shot on-scene.[200] The station is also purported to be the first in the U.S. to have been allowed access to film a court proceeding on December 13, 1953, while covering Billy Eugene Manley's murder trial at the Oklahoma County Courthouse.[201] Led by Frank McGee,[202] a WKY-TV news crew was placed in a custom-built enclosed booth near the courtroom's rear, with a discreet microphone[203] and a small button that Judge A. P. Van Meter could use to stop recording at any point.[204] The swearing in of the jury, some testimony and Manley's sentencing was filmed for later news broadcasts.[205][206] After OPUBCO purchased WSFA and WSFA-TV in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955, McGee—under his real name—became WSFA-TV's news director;[207] McGee's reporting regarding both the Montgomery bus boycott and riots on the University of Alabama campus over Autherine Lucy's admission motivated NBC News to hire him at the end of 1956 for their Washington operations.[208]

The station was full of mentors. In all categories someone took the time to mentor me and critique me in a helpful way. That is how I learned. No one ever once made me feel bad. Their feedback was pointed and important, and I soaked up the lessons they were teaching.

Virgil Dominic, former WKY-TV reporter[209]

Virgil Dominic initially joined WKY-TV in 1956, then after two months was called into active duty with the U.S. Air Force;[209] Dominic returned to the station in 1959 as both a reporter and news anchor.[211] As NBC News did not have dedicated news bureaus in the early 1960s, Dominic was often requested to file reports to the network—particularly on The Huntley–Brinkley Report—whenever a story was needed from Oklahoma or portions of adjacent states.[212] In 1964 alone, Dominic and WKY-TV provided 36 news stories, a record amount for any NBC affiliate.[213] When NBC hired away Virgil in 1965, he was assigned to network-owned WKYC-TV in Cleveland as that station's lead anchor[211] in addition to newscasting duties for NBC Radio.[214]

In 1972, Pam Henry—who after contracting polio at 14 months old, was the March of Dimes' 1959 national poster child—was hired by channel 4 as an assignment reporter, the first female television news reporter in Oklahoma.[215] After a brief stint working in Washington, D.C.,[216] Henry worked at other television stations in Oklahoma City and Lawton, and was OETA's news and public affairs manager for 16 years.[217] From 1973 to 1978, WKY-TV aired Spectrum, a weekly prime time public affairs newsmagazine focused on issues affecting Oklahoma's minority community.[218] Through The Looking Glass Darkly, a Spectrum installment about the history of blacks in Oklahoma produced and reported by eventual NBC News correspondent Bob Dotson became the first program from an Oklahoma television station to win a national Emmy Award in 1974.[219]

Members of the Ogle family have been part of channel 4 in some manner since 1962, when Jack Ogle joined WKY-TV as its main news anchor. Best known for a friendly, "good-ol'-boy" on-air delivery,[220] Ogle became the station's news director in 1970 and served in that capacity until leaving in 1977 to join Oklahoma State's athletic department.[221] Ogle continued to make occasional appearances on channel 4, KOCO-TV and KWTV delivering commentaries.[222][223] All three of Jack's sons followed him into broadcasting, two of them at channel 4. Eldest son Kevin first worked at KTVY from 1986 to 1989 as a reporter, then returned in 1993 and was promoted to weeknight co-anchor in 1996. Middle son Kent was hired by KFOR-TV as a reporter in 1994,[224] anchored weekend newscasts[225] and became weekday morning/noon anchor in 1997. Youngest son Kelly has been KWTV's evening anchor since 1990,[220] and granddaughters Abigail and Katelyn Ogle work at KOCO-TV and KFOR-TV, respectively.[226]

As many years as he was in the job, he was always enthusiastic about it. He was always a young guy in a little bit older body. He always stayed that same young guy and embraced life.

Damon Fontenot, KFOR sports anchor, on Bob Barry Jr.[227]

Bob Barry Sr. started his television career at WKY-TV in 1966 as lead sports anchor, but was already a fixture in the market as the radio play-by-play voice of the Oklahoma Sooners, a position Sooners coach Bud Wilkinson selected Barry for in 1961.[228] Barry called radio broadcasts of OU and Oklahoma State football and basketball games with Jack Ogle until 1974. Barry became sports director in 1970,[229] holding that position for 26 of his 42 years at channel 4,[230] and remained a part-time evening sports anchor until his May 2008 retirement.[231] His son Bob Barry Jr. became KTVY's weekend sports anchor/reporter in 1982, working along Bob Sr. for 25 years and assuming his father's role as sports director in 1997. The younger Barry—who was known for a jovial, off-the-cuff style—was KFOR-TV's sports director and weeknight sports anchor until his June 20, 2015, death in an auto/motorcycle accident.[227][232] Including a posthumous win by Bob Barry Jr. in 2016, both Barrys earned 22 "Sportscaster of the Year" awards from the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association; Barry Sr. holds the record for most wins with 15.[233] Station veteran Brian Brinkley succeeded Barry Jr. as sports director in February 2016.[234][235]

Brad Edwards, who joined channel 4 as a reporter/photographer in 1973 and became late evening anchor in 1977,[221] launched the In Your Corner series of consumer advocacy reports in 1981. Edwards also started several community initiatives for the station to assist low-income residents, including the winter-focused "Warmth 4 Winter" and summer-focused "Fans 4 Oklahomans".[236] Following Edwards's death in May 2006,[237] In Your Corner duties were handled by a rotation of staffers until Scott Hines took over the role in 2007,[238] remaining at the station until September 2019.[239] Adam Snider was subsequently named as Hines' replacement in December 2019.

The station began to slowly expand its local news programming following the 1990 call letter change to KFOR-TV. Under the direction of then-general manager Bill Katsafanas and news director Melissa Klinzing, a greater emphasis was placed on Oklahoma-related stories and features[149] along with the aforementioned hourly news updates.[150] Klinzing enacted the strategy to gear KFOR-TV as "the CNN of the (Oklahoma City) market". With Palmer Communications committing resources to the news department, KFOR-TV's news output increased from 25 hours to over 40 hours per week by 1996; the station accordingly became the top-rated local newscast with the May 1995 sweeps.[240]

During coverage of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building bombing on April 19, 1995, KFOR-TV erroneously reported a member of the Nation of Islam contacted the station to take credit, but cautioned the phone call might have been a crank call.[241] Lead anchor Linda Cavanaugh was in Vietnam producing a series about Vietnam War prisoner of war experiences, and only found out about the bombing by seeing KFOR-TV's coverage, helmed by co-anchor Devin Scillian, simulcast on CNN in her hotel room;[242] NBC additionally relayed KFOR-TV's feed across their entire network.[243] In the bombing's aftermath, then-KFOR reporter Jayna Davis filed a report claiming that Timothy McVeigh was seen drinking beer with a former Iraqi soldier in an Oklahoma City tavern; the individual Davis implicated on-air sued the station, while KFOR-TV sued Davis and her husband after they stole videotapes of her past work when she left the station.[244] Cavanaugh would produce and host Tapestry, a 1996 documentary on the lives of survivors of the bombing[245] honored with four regional Emmys, a Gabriel Award, and accolades by the Oklahoma Association of Broadcasters, the National Press Club and the Society of Professional Journalists.[242][246]

I never had any intention of anchoring or being in front of the camera. As I was growing up, Channel 4 was the only station that my grandparents watched... and so when it came time to pick a station (to work at), that was the only one I knew about.

Linda Cavanaugh[247]

Linda Cavanaugh spent her entire 40-year broadcasting career at the station, from October 17, 1977, to December 15, 2017.[247] Originally an assignment reporter and news photographer, Cavanaugh was promoted to weekend anchor in June 1978, and then became the station's first weeknight co-anchor the following year. Until her retirement in 2017, Cavanaugh's co-anchors included George Tomek, Brad Edwards, Gary Essex, Jerry Adams,[248] Jane Jayroe,[249] Dan Slocum,[250] Bob Bruce,[251] Devin Scillian[243] and Kevin Ogle. In addition to Tapestry, Cavanaugh's 1989 documentary From Red Soil to Red Square—assisted by chief photographer Tony Stizza—about life in the Soviet Union under glasnost was awarded the Edward Weintal Prize for Diplomatic Reporting.[38]

KFOR-TV has competed with KWTV for first place among the market's local television newscasts for decades. It had placed second behind KWTV in the morning and late evening news timeslots. Nielsen later found an error in KFOR's ratings reports in September 2008, in which share points were mistakenly assigned to KFOR's 4.1 digital multicast signal from 2005 to 2008;[252] the corrected ratings showed that it had placed #2 in all timeslots at that time. On June 5, 2006, KFOR-TV began producing a half-hour weeknight 9 p.m. newscast for KAUT-TV; it expanded news programming on KAUT with the debut of a two-hour extension of its weekday morning newscast on September 8, 2008.

A collection of 16 mm news footage shot by WKY-TV between 1953 and 1979 was donated to the Oklahoma Historical Society, which made the films available on its website and a dedicated YouTube channel, in 2013.[253]

Severe weather coverage

We had hundreds and hundreds of postcards and letters of thanks... I remember one card said, 'Thank God for Harry Volkman.'

Harry Volkman, remembering viewer reaction to his pioneering 1952 telecast of a tornado warning[254]

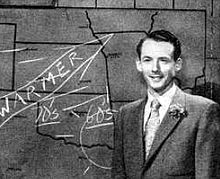

Channel 4 has laid claim as the first television station to house a professional meteorological department, beginning with Wally Kinnan's February 1951 hiring as a nightly weather presenter, dubbed "Wally the Weatherman."[255] A graduate of MIT, Kinnan was one of the first meteorologists to be awarded a "seal of approval" by the American Meteorological Society with seal number #3[256] and was on active duty with the U.S. Air Force, stationed at Tinker Air Force Base as a Air Weather Service (AWS) officer and tornado researcher.[257] Kinnan had developed methodology to predict and detect tornadoes using radar by identifying wind patterns to predict precipitation movement, despite the AWS's belief no method could exist to accurately predict them.[258] Kinnan was soon teamed with fellow meteorologist Harry Volkman, who joined WKY-TV in March 1952 after a two-year stint at Tulsa's KOTV.[58]

WKY-TV holds the distinction of being the first television station to broadcast a tornado warning. Station general manager P.A. Sugg and Oklahoma senator Mike Monroney had actively lobbied the federal government to overturn a ban on disseminating tornado alerts to the public, believing the high fatality risk and urgency for residents to take safety precautions outweighed concerns that they could incite panic.[258] Several weeks after Harry Volkman joined the station on March 21, 1952,[note 3] Sugg intercepted an AWS tornado forecast—intended to be released exclusively to Tinker Base staff—and instructed Volkman to deliver an on-air bulletin of the "tornado risk" for central Oklahoma.[254] Though he had apprehension of facing arrest for violating government rules, Volkman agreed to deliver the warning after Sugg volunteered to take responsibility.[259] WKY-TV and WKY remained on-air until 1 a.m.,[260] with residents of Woodward, Alva and adjacent farm communities having retreated to storm cellars, prompted by the alert.[261] It was on May 1, 1954,[note 4] that Frank McGee intercepted another AWS weather bulletin meant for Tinker Base regarding a tornadic thunderstorm approaching Meeker, relaying it over the phone to Volkman.[262] No one in Meeker lost their lives despite the tornado's destruction, with one resident telling an Associated Press reporter, "God bless Harry Volkman."[263] The federal ban on broadcasting tornado watches/warnings was eventually repealed in part due to the efforts of Volkman and Kinnan, and WKY-TV became the first station to hold a contract with the National Weather Service.[264]

Volkman left the station in October 1955 to join KWTV and KOMA (1520 AM), prompting Kinnan to take over his nightly forecasting duties.[265] On January 23, 1958, WKY-TV became the first Oklahoma television station to utilize the weather radar from Will Rogers Field during severe weather conditions, with an effective range of 200 miles (320 km) radius.[266] The station additionally installed a converted surplus military radar for use as a radar of their own, utilizing that unit until 1970.[267] Kinnan departed WKY-TV in September 1958 to join Philadelphia's WRCV-TV, then owned by NBC; Bob Thomas, who had joined the station at the end of 1957, became Kinnan's replacement.[268][269] 1958 also saw the hiring of Jim Williams, who would succeed Bob Thomas as chief meteorologist in 1967.[270] Williams worked at channel 4 for 32 years, earning industry praise for a calm and steady on-air demeanor[271] in addition to pioneering further technical advancements.[272]

In recent years, KFOR-TV, KWTV and KOCO-TV have displayed a public rivalry over severe weather coverage. KWTV became the first station in the country to use a Doppler weather radar system in 1981, then upgraded the system in 1984.[273] Channel 4 followed suit with colorized Doppler radar in 1986, then "Super Doppler" in 1990.[145] Mike Morgan joined KFOR-TV as chief meteorologist in 1993,[274] having taken over for one of Jim Williams' short-lived successors, Wayne Shattuck, who himself preceded Morgan at KOCO-TV in the same position.[275] Morgan entered the business interning with the National Weather Service at age 13, began his on-air career in Tulsa in 1984 at age 19, and attained a bachelors' in science and meteorology in 1992 while at KOCO-TV.[276] Japanese public television network NHK profiled Morgan and the KFOR-TV weather department in February 1994 as part of a documentary about American broadcast coverage of natural disasters.[277]

In 1994, KFOR-TV became the first television station to transmit images over cell phones with the development of "First Video", technology that allowed the station's news crews to send photos and video of severe weather over mobile relays for broadcast.[278] While the video was transmitted at lower frame rates, this enabled quicker transmission and increased flexibility compared to conventional microwave or satellite facilities.[279] For decades, KFOR-TV's helicopters have been used extensively in newsgathering and severe weather coverage, with the station currently operating a Bell 206L-4 LongRanger IV. Along with KWTV's chopper, it captured live, continuous footage of an F5 tornado that killed 36 people from Amber to Midwest City on May 3, 1999, with Moore among the hardest hit,[280] which earned industrial acclaim for station chopper pilot Jim Gardner.[281] Government officials praised the local broadcast media as a whole after the storm for properly alerting the public and preventing additional fatalities.[282]

Living in Oklahoma, our weather is tough but our people are tougher. The Moore tornado was devastating, but we know that our severe weather coverage saved lives that day. Our team did everything possible to alert viewers to the danger. We are honored to accept this Emmy award and we would like to dedicate this to the people of Moore.

Wes Milbourn, KFOR-TV general manager, accepting the station's 2015 Emmy Award for their coverage of the 2013 Moore tornado[283]

KWTV management criticized KFOR-TV after what it deemed "sensationalistic" coverage on March 7, 2000, when the station preempted programming for possible tornadic activity, the only station in the market to do so.[284] KWTV meteorologist Gary England then stated on-air that other stations—not specifically citing KFOR-TV or Mike Morgan—should not take a "chicken little" approach by excessively covering tornadoes that don't immediately threaten life and property, and compared it to "yelling 'fire' in a crowded auditorium."[285] Morgan and KFOR-TV defended their coverage after hearing of initial damage to telephone poles and eyewitness reports that suggested dangerous conditions.[285] During an October 2000 storm, Morgan noted on-air that KFOR-TV's "The Edge" radar was "20 to 25 minutes" ahead of NEXRAD data due to unexpected data lag, noting that KWTV forecaster Brady Bus erroneously listed a specific area as in "the danger zone" minutes after the fact; Bus later remarked he didn't put stock in anything said by someone without a meteorological degree.[286] After another tornado struck Moore in 2003, KFOR-TV invested in the first million-watt radar system in the area, which came into service in 2005.[287] David Payne, a KFOR-TV meteorologist from 1993 to 2013, also performed storm chasing for the station during severe weather coverage,[285] most notably capturing footage of a rare anticyclonic tornado that damaged the El Reno Regional Airport on April 24, 2006.[288] Payne left the station in 2013 to become KWTV's chief meteorologist, working with, and ultimately succeeding, Gary England.[289]

It was KFOR-TV's coverage of the May 20, 2013, EF5 tornado which struck Moore that garnered national and international attention, as it was significantly aided by chopper footage that captured both the tornado's path in real-time and the immediate destruction to the city.[290][291] Visuals from the scene, and particularly from KFOR-TV's helicopter,[292] were aired live on CNN[293] leading to increased coverage by other national news outlets and pleas to donate to the American Red Cross on social media.[294] The station was awarded the 2015 News & Documentary Emmy Award for "Regional – Spot News" for their coverage of the tornado with the staff dedicating the Emmy to the citizens of Moore.[283] It was the third national Emmy in channel 4's history,[290] having also won in the same category in 2007 for their 2006 El Reno tornado coverage.[288][295]

Non-news

In addition to newscasts, KFOR-TV also airs some ancillary non-news local programming. Since 1993, KFOR-TV has aired the Sunday morning talk show Flash Point, hosted by weeknight anchor Kevin Ogle with Mike Turpen and Todd Lamb as liberal and conservative panelists, respectively.[296] The station has exclusively broadcast the Oklahoma City Memorial Marathon benefiting the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum since its April 2001 inaugural run.[297]

KFOR-TV originates Discover Oklahoma, a half-hour regionally syndicated program highlighting tourist attractions, events and restaurants produced by the Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation.[298] The program initially ran on KFOR-TV from 1992 to 1995,[299] and returned to the station in 2014 after a 21-year run at KWTV.[300]

Notable on-air staff

Current staff

- Kevin Ogle, weeknight anchor, reporter and statewide newsreader[220]

- Mike Morgan, chief meteorologist[274]

- Todd Lamb, political commentator and Flash Point panelist[301]

- Mike Turpen, political analyst and Flash Point panelist[296]

Former staff

- Bob Barry Jr.[227]

- Bob Barry Sr.[231]

- Tiffany Blackmon[302]

- Linda Cavanaugh[247]

- Bob Dotson, later of NBC News[210]

- Brad Edwards[237]

- Mary Hart, later of Entertainment Tonight[100]

- Burns Hargis[303]

- Dave Hood[131]

- Kirk Humphreys[304]

- Jane Jayroe[249]

- Wally Kinnan[258]

- Herschell Gordon Lewis[305]

- Ben McCain[128]

- Butch McCain[128]

- Frank McGee, later of NBC News[192]

- David Payne[289]

- Russell Pierson, agriculture reporter from 1959 to 1983[306]

- Ross Porter[57]

- Marianne Rafferty[307]

- Devin Scillian[243]

- Bella Shaw, later of CNN[308]

- Hank Thompson[309]

- Ron Thulin[310]

- Reed Timmer[311]

- Harry Volkman[254]

Technical information

Subchannels

The station's digital signal is multiplexed:

| Channel | Video | Aspect | Short name | Programming[312] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 | 1080i | 16:9 | KFOR-DT | Main KFOR-TV programming / NBC |

| 4.2 | 480i | 4:3 | ANT-TV | Antenna TV |

| 4.3 | Justice | True Crime Network | ||

| 4.4 | 16:9 | DABL | Dabl | |

| 43.1 | 1080i | KAUT-DT | ATSC 1.0 simulcast of KAUT-TV |

Analog-to-digital conversion

KFOR-TV began transmitting a digital television signal on UHF channel 29 on June 1, 1999, becoming the first television station in Oklahoma City and the state of Oklahoma as a whole to begin operating a digital signal; until KFOR-DT began broadcasting on a full-time basis on May 1, 2002, the digital feed only transmitted NBC prime time and sports programming as well as a limited schedule of local programs carried by the main analog signal. The station discontinued regular programming on its analog signal, VHF channel 4, on June 12, 2009, as part of the federally mandated transition from analog to digital television; the station's digital signal remained on its pre-transition UHF channel 27.[313]

On October 8, 2020, ATSC 3.0 Next Gen TV launched in Oklahoma City, with KAUT-TV as the host station and KFOR-TV as one of the feeds offered. KAUT in ATSC 1.0 format was moved onto KFOR-TV's multiplex on that date.[314]

Translators

KFOR-TV is additionally rebroadcast over a network of nine low-power digital translator stations:[312]

- Cherokee/Alva: K20JD-D

- Elk City: K32OF-D

- Gage: K20BR-D

- Hollis: K34JJ-D

- Mooreland: K33JM-D

- Sayre: K23ND-D

- Selling: K18LY-D

- Strong City: K18LS-D

- Weatherford: K35MQ-D

See also

Notes

- ^ Prior to receiving a commercial license in 1922, WKY operated as experimental station 5XT from 1920 to 1922 and is also regarded as one of the oldest radio stations west of the Mississippi.

- ^ The Sixth Report and Order ended a September 1948 freeze imposed by the FCC on issuing television station licenses and realigned VHF channel assignments in multiple markets.

- ^ An OPUBCO corporate brochure from 1967 erroneously attributes the date as in 1951.

- "WKY goes where the action is". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 12, 1967. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ A 2016 Oklahoman story regarding a National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum exhibit gave the incorrect date of September 5, 1954, for this event.

- Brandy McDonnell (April 4, 2016). "National Cowboy museum exhibit in Oklahoma City explores the effects of weather in the West". The Oklahoman. The Anschutz Corporation. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

References

- ^ a b Chavez, Tim (April 24, 1990). "Channel 4 Switches To KFOR". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "Facility Technical Data for KFOR-TV". Licensing and Management System. Federal Communications Commission.

- ^ a b "Daily Television Is Far In Future". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 17, 1939. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Speaker Describes New WKY Studio As The 'Most Modern in the World'". Sooner State Press. University of Oklahoma. April 18, 1936. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Meeks, Herman Ellis (May 1991). "A History of WKY-AM" (PDF). Denton, Texas: University of North Texas. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "WKY's Guests Offer Praise Of New Studio". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 14, 1936. pp. 1, 4. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l West, Keith (May 1991). "Images Across the Prairie: The Birth of WKY-TV" (PDF). Stillwater, Oklahoma: Oklahoma State University–Stillwater. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ "Mirrors, Buttons And Wires Create Modern Miracle". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 13, 1939. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Television Apparatus Installed For First Shows Today". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 13, 1939. p. 15. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Television Baggage Is Unpacked". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 10, 1939. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Interest in Television's Magic Twice Fills Auditorium; Queen of Light Waves Makes Debut". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 14, 1939. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Brad Agnew (October 8, 2016). "TV transformative for Tahlequah residents". Tahlequah Daily Press. Community Newspaper Holdings. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "If You Want To Be Broadcast, See Television". The Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 4, 1939. p. 16. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Television Caravan Ready". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 10, 1944. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Television Star is in State for WKY Caravan". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 10, 1944. p. 18. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "WKY Caravan Finishes Tour At Chickasha". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. December 3, 1944. p. A-19. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Rucker, Tom (November 19, 1944). "WKY Caravan Continues Tour In Bond Drive". The Daily Oklahoman. p. B-10. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "WKY Television". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. May 17, 2002. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b FCC History Cards for KFOR-TV

- ^ "Actions of the FCC" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 26, 1948. p. 48. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Seek Video: 12 More File Applications With Commission" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 19, 1948. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Video Grants: FCC Authorizes Seven More" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. June 7, 1948. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018 – via World Radio History.

- "Actions of the FCC" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. June 7, 1948. p. 79. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Permit Granted for Television". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. June 3, 1948. p. 20. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "This Controls The Television System". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. June 5, 1949. p. E-24. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Little Theater's Loss is $150,000". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 17, 1948. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- "Up in Smoke". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. November 17, 1948. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Oklahoma TV: WKY-TV Studios Completed" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 18, 1949. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Wires, Tubes and Headaches Keep Engineer Lovell Busy; Expert Faces Weary Routine". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. June 5, 1949. p. E26. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Oklahoma Video: WKY-TV Installs Antenna" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 11, 1949. p. 164. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "TV Pattern Goes on Air Daily Monday". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 24, 1949. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- "In Channel 4..." The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 24, 1949. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- "TV Test Pattern". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 23, 1949. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Lightning Hits TV Antenna". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 28, 1949. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "TV Tells Tale Of The Tape". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. May 28, 1949. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "WKY-TV Day? It'll Be June 6!". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 27, 1949. p. 1, 2. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- Wilson, Madelaine (June 3, 1949). "WKY Studios Buzz With TV Practice". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Video Screens Bloom Tonight". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. June 6, 1949. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Vanj Dyke, Bill (June 7, 1949). "Stars Parade as WKY Video Gets Under Way". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Guffey, Chan (June 6, 1949). "Station Ready To Bring State New Diversions". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Patrick, Imogene (June 7, 1949). "At Laundromats And in Homes, TV Scores With Bang". The Daily Oklahoman. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "First Television Broadcast Success". Rogers County News. United Press. June 7, 1942. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c "KTVY Celebrates 40th Birthday". The Daily Oklahoman Television News. Oklahoma Publishing Company. June 11, 1989. pp. 17, 68. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "WKY Takes On Two More TV Contracts". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 23, 1949. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Joe Angus (June 3, 1984). "Oklahoma TV 35 years old: Channel 4 first to air". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "Gismo to be on WKY Television". The Shawnee American. June 3, 1949. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "Smoke..." The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. June 5, 1949. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "OKC TV, radio icon Danny Williams dies". The Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. February 20, 2013. p. 16A. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- "Timeline: Danny Williams". The Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. February 19, 2013. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Ann DeFrange (March 14, 2006). "Oklahoma History Center honors TV's 3-D Danny". The Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "Oklahoma City television and radio icon Danny Williams dies". The Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. February 19, 2013. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Osburn, Lyn (July 9, 1978). "Durable Danny: Senior Disc Jockey (and sometimes unendurable)". The Sunday Oklahoman Oklahomans Magazine. Oklahoma Publishing Company. pp. 4, 5, 6, 7. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ "WKY to Televise Star Cage Game". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. August 16, 1949. p. 15. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "WKY to Televise Queens' Softball". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. August 3, 1949. p. 15. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "Night and Day, At Home or Away TV Follows OU". The Oklahoma Daily. University of Oklahoma. September 20, 1949. p. 11. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "College Football Goes On Television". The Hollis Weekly News. September 29, 1949. p. 12. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "WKY-TV Low Band Channel 4: Today (advertisement)". The Daily Oklahoman. September 8, 1953. p. 13. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Andrew McGregor (May 9, 2016). "The Bud Wilkinson Show: Television, the NCAA, and the Cold War". Sport in American History. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Van Dyke, Bill (September 24, 1953). "Regents Will Obey Football TV Limit". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. pp. 1-2. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "Sooner Coach Completes TV Sports Series". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. July 20, 1954. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "Porter picked as narrator for Big Red". Shawnee News-Star. August 23, 1960. p. 1. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Ross Porter Quits WKY Sports Post". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. October 5, 1966. p. 14. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ a b "10 Questions with ... Ross Porter". All Access. All Access Music Group. August 23, 2011. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Company scores historic firsts". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. February 16, 2003. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "WKY Plans New Building and Studios" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. January 30, 1950. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "WKY-TV Shifts to Britton From Auditorium". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. July 18, 1951. p. 11. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Television Enters the Picture". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. May 17, 2002. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "WKY Switches Into TV Network". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. July 2, 1952. p. 6. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "State Television Stations Become Part of Network". The Ponca City News. Associated Press. July 1, 1952. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "WKY Television". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. May 17, 2002. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Codel, Martin (June 26, 1954). "HEAVY LOSSES..." (PDF). Television Digest. Vol. 10, no. 26. Radio News Bureau. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ "WKY-TV Channel; Sees Change Costly" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. November 5, 1951. p. 95. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Assignment Principles" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 14, 1952. pp. 75, 76, 77. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "WKY-TV Signs ABC Basic Pact" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. September 7, 1953. p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "WKY-TV to Drop CBS-TV As KWTV Nears Affiliation" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. October 26, 1953. p. 74. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ a b "Television Enters the Picture". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. May 17, 2002. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Sandi Davis (April 18, 1999). "Feb. 11, 1950: WKY-TV Lets City Viewers Tune In to Television Era". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "For the Record" (PDF). Broadcasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. March 3, 1958. p. 91. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ a b "Color On Way: New WKY-TV Cameras Due". Logan County News Tel-eVents. February 4, 1954. pp. 1, 8. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- "Television in Color Moves Step Nearer For Oklahoma Firm". Seminole Producer. March 14, 1954. p. 6. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ Bill Moore (July 4, 2016). "WKY-TV: First In Local Live Color". Eyes Of A Generation. Museum of Broadcast Technology. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "Color Adds Zest to Sport, or Symphony" (PDF). Broadcasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. February 20, 1961. pp. 106, 108. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "WKY-TV Slates Colorcasts As First Camera Arrives" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. March 29, 1954. p. 62. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Color Television Has City Debut". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 5, 1954. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Leading the Color-Blind" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 19, 1954. p. 86. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- "WKY-TV Color Advertisement" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. May 10, 1954. p. 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "WKY-TV Slates First Colorcast With a Sponsor". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 21, 1954. p. 21. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ Codel, Martin (April 24, 1954). "Color Trends & Briefs" (PDF). Television Digest. Vol. 10, no. 17. Radio News Bureau. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ "WKY-TV Now Colorcasting Regular Commercial Show" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 26, 1954. p. 64. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ Codel, Martin (May 1, 1954). "Color Trends & Briefs" (PDF). Television Digest. Vol. 10, no. 18. Radio News Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ Codel, Martin (May 8, 1954). "Color Trends & Briefs" (PDF). Television Digest. Vol. 10, no. 19. Radio News Bureau. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

Quality of WKY-TV's color, incidentally, "is better than some of ours," according to NBC-TV color coordinator Barry Wood.

- ^ "A salute to Rotarian Joe White McBride: He Builds Big…". The Oklahoma Publisher. Oklahoma Press Association. Oklahoma City Rotary News. September 1, 1954. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "Indian Show Opens Monday". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. August 15, 1954. p. B-1. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "State Indians To Be Seen on TV". Henryetta Daily Free-Lance. United Press. August 8, 1954. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "TV Lens to Focus On Square Dances". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. April 23, 1955. p. 20. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "WKY-TV Airs Closed-Circuit Medical Program in Color" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. January 24, 1955. p. 67. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Surgical TV: WKY-TV Uses Closed Circuit" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. February 20, 1950. p. 80. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ a b "Oklahomans Respond Quickly To WKY-AM-TV Eye Programs" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. December 16, 1957. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ a b "WKY Helps Eye Bank" (PDF). Broadcasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. December 18, 1961. p. 65. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via World Radio History.

- ^ Ann DeFrange (November 20, 1994). "Circle 4 Ranch, "Foreman Scotty" Lassoed TV Era". The Daily Oklahoman. Oklahoma Publishing Company. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2014.